Submitted:

23 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

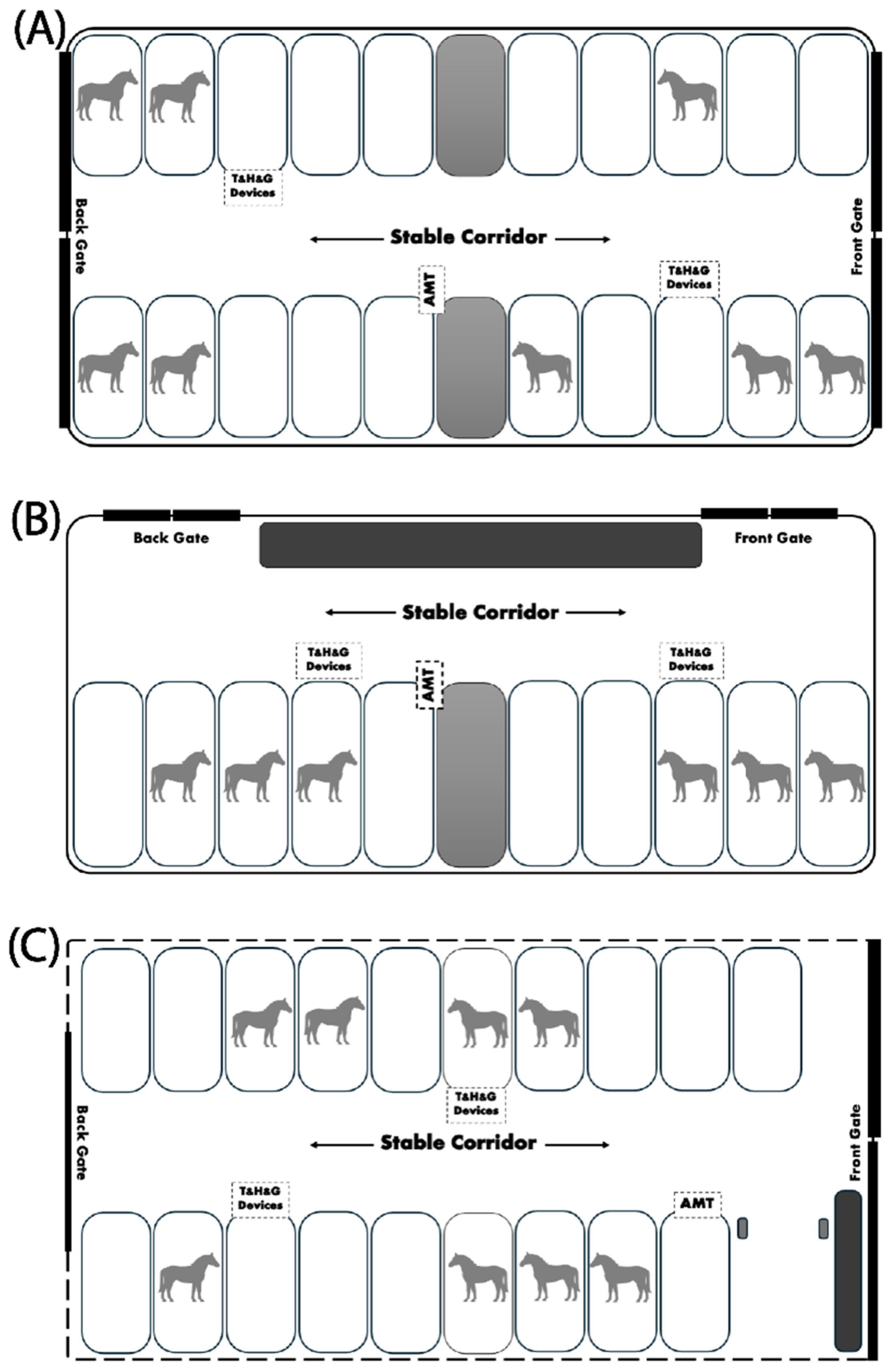

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Experimental Protocols

2.3. Data Acquisition

2.3.1. Environmental Parameters

2.3.2. Autonomic Regulation

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

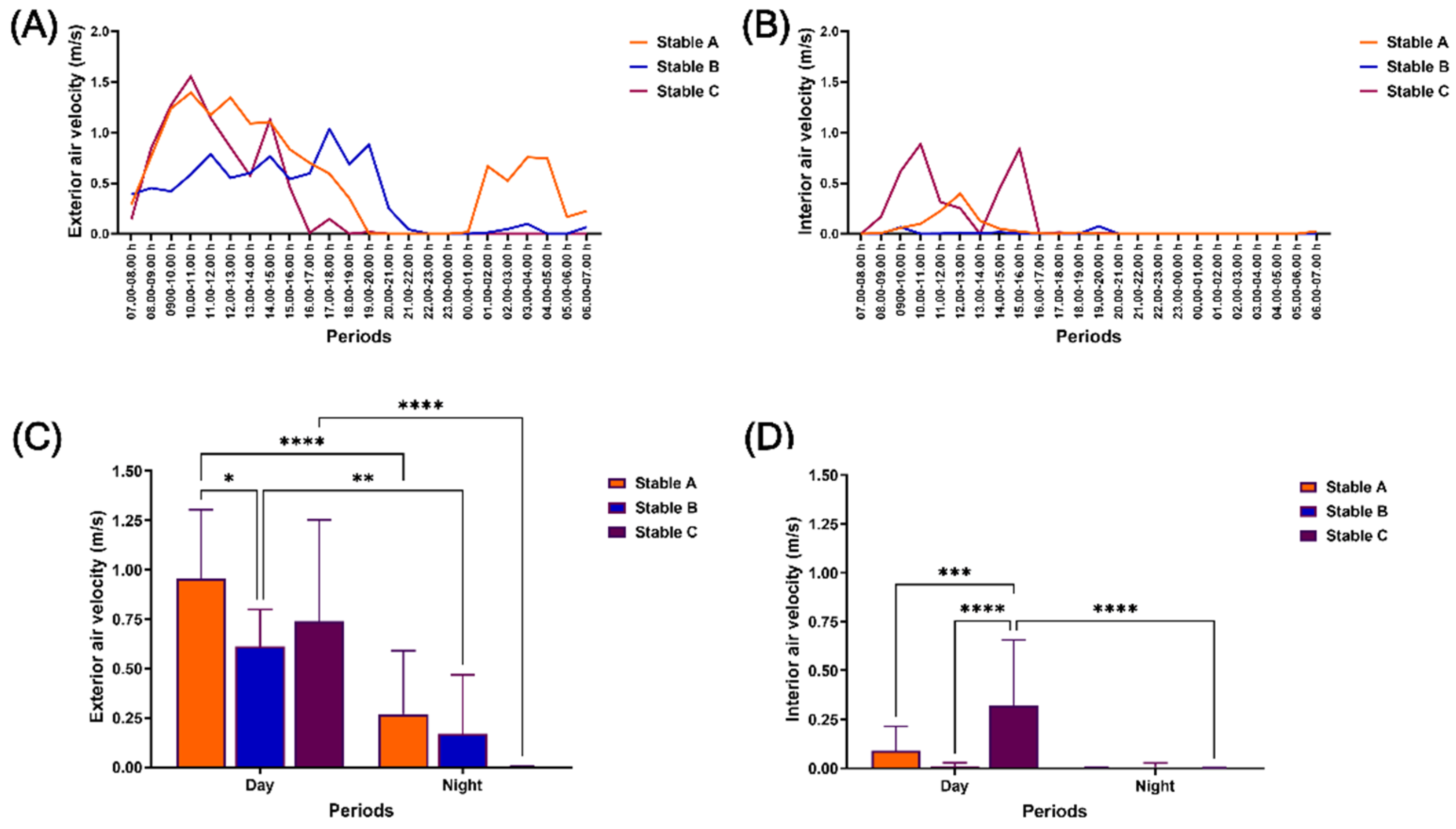

3.1. Air Velocity

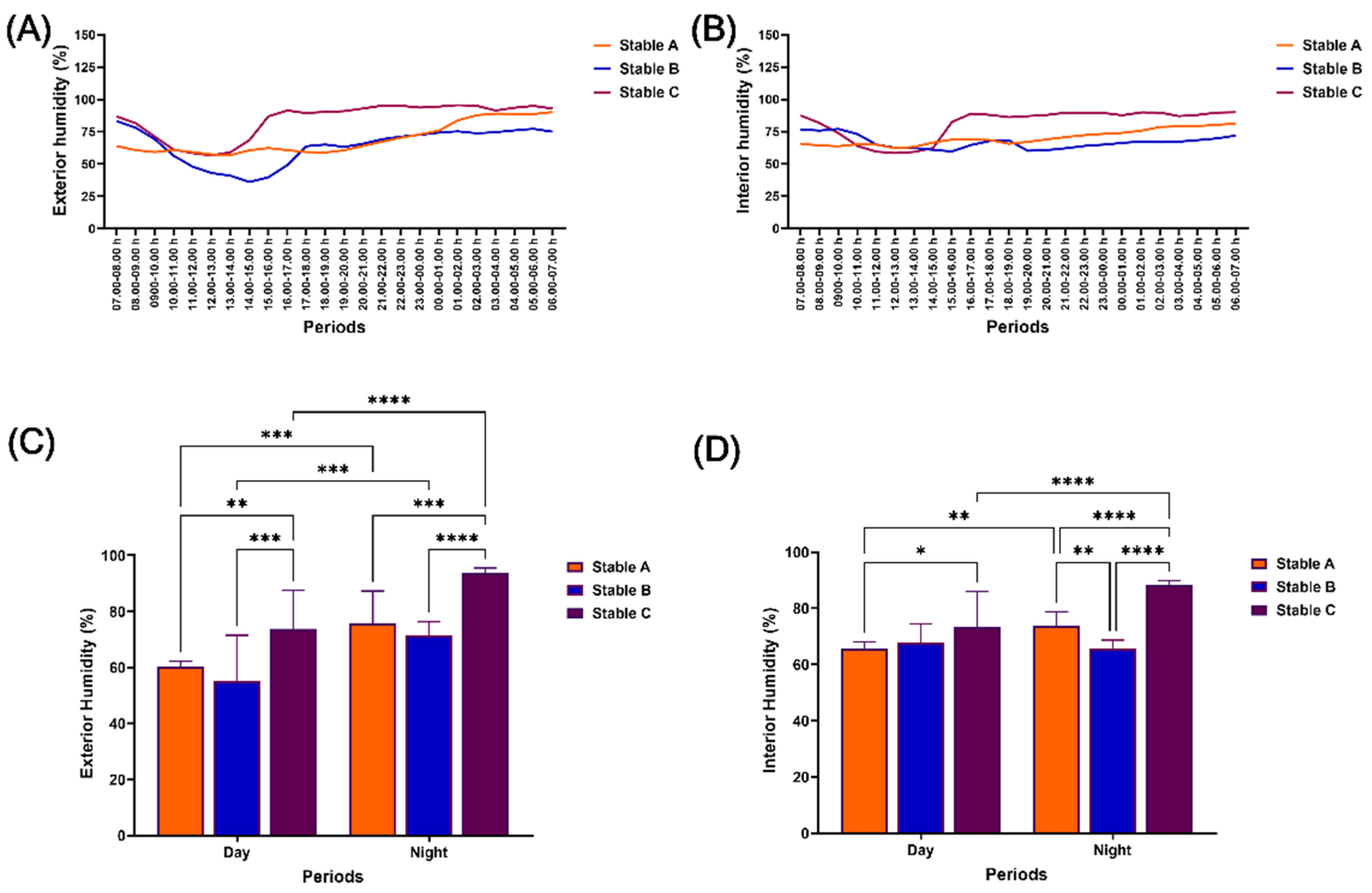

3.2. Relative Humidity

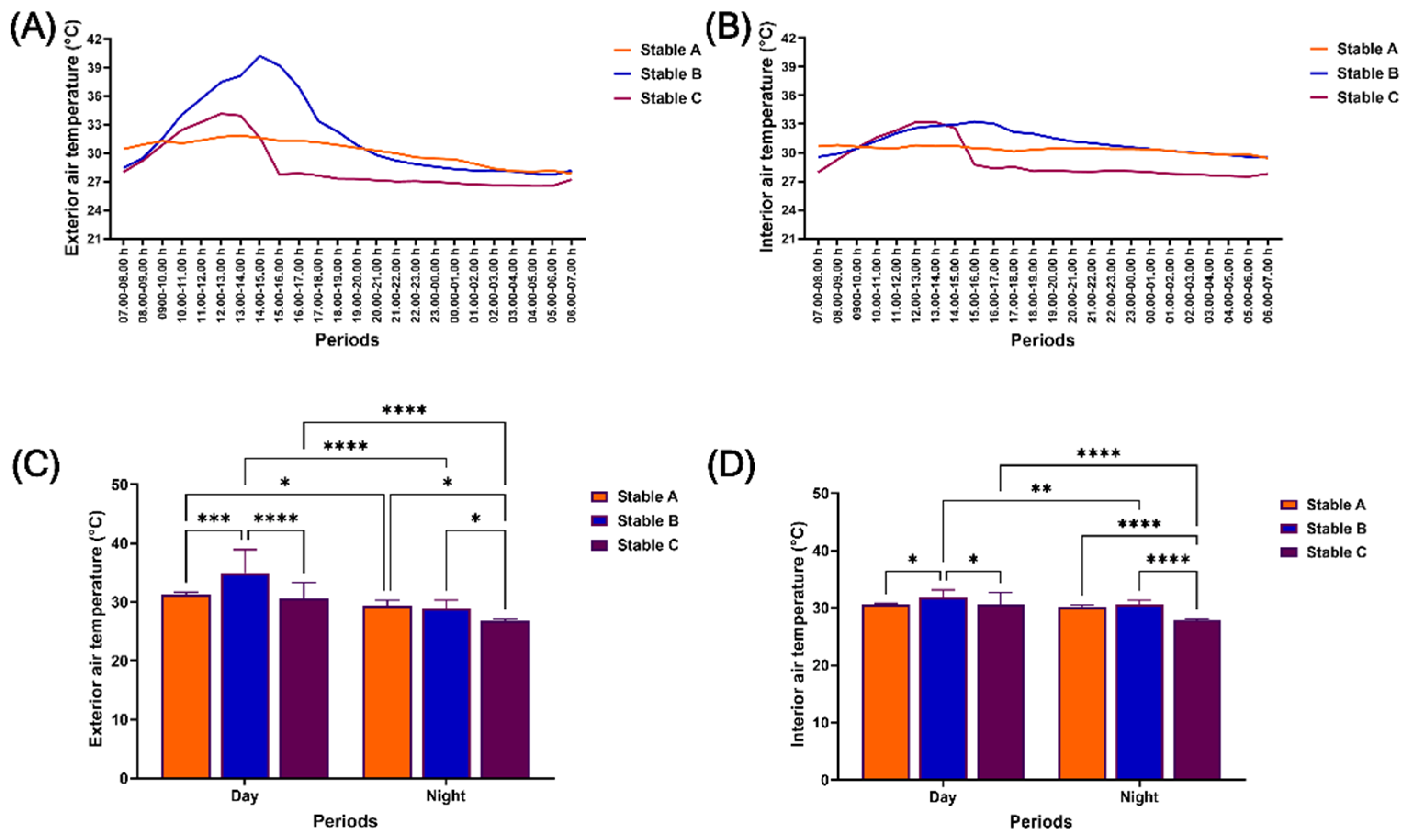

3.3. Air Temperature

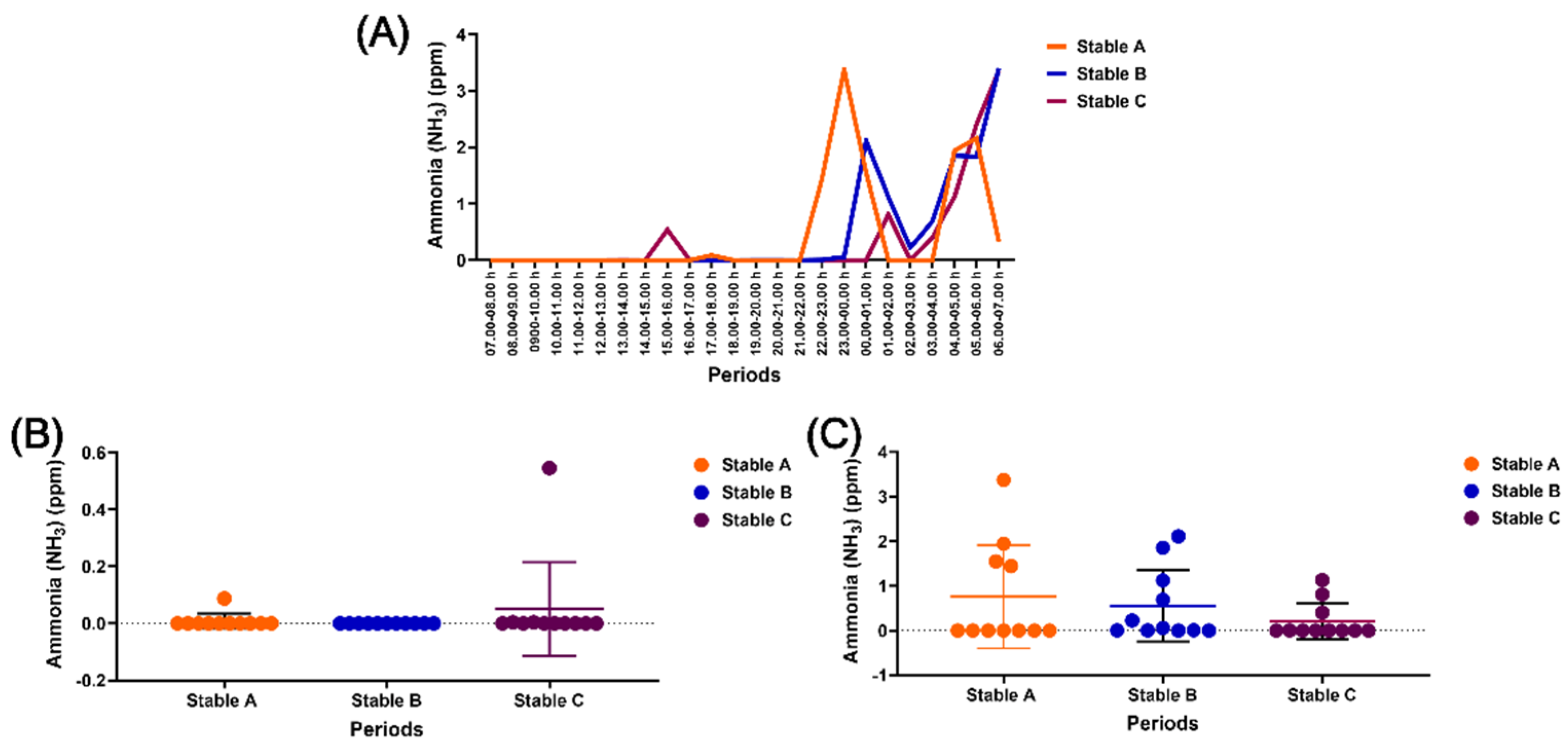

3.4. Levels of Noxious Gases

3.5. Autonomic Regulation

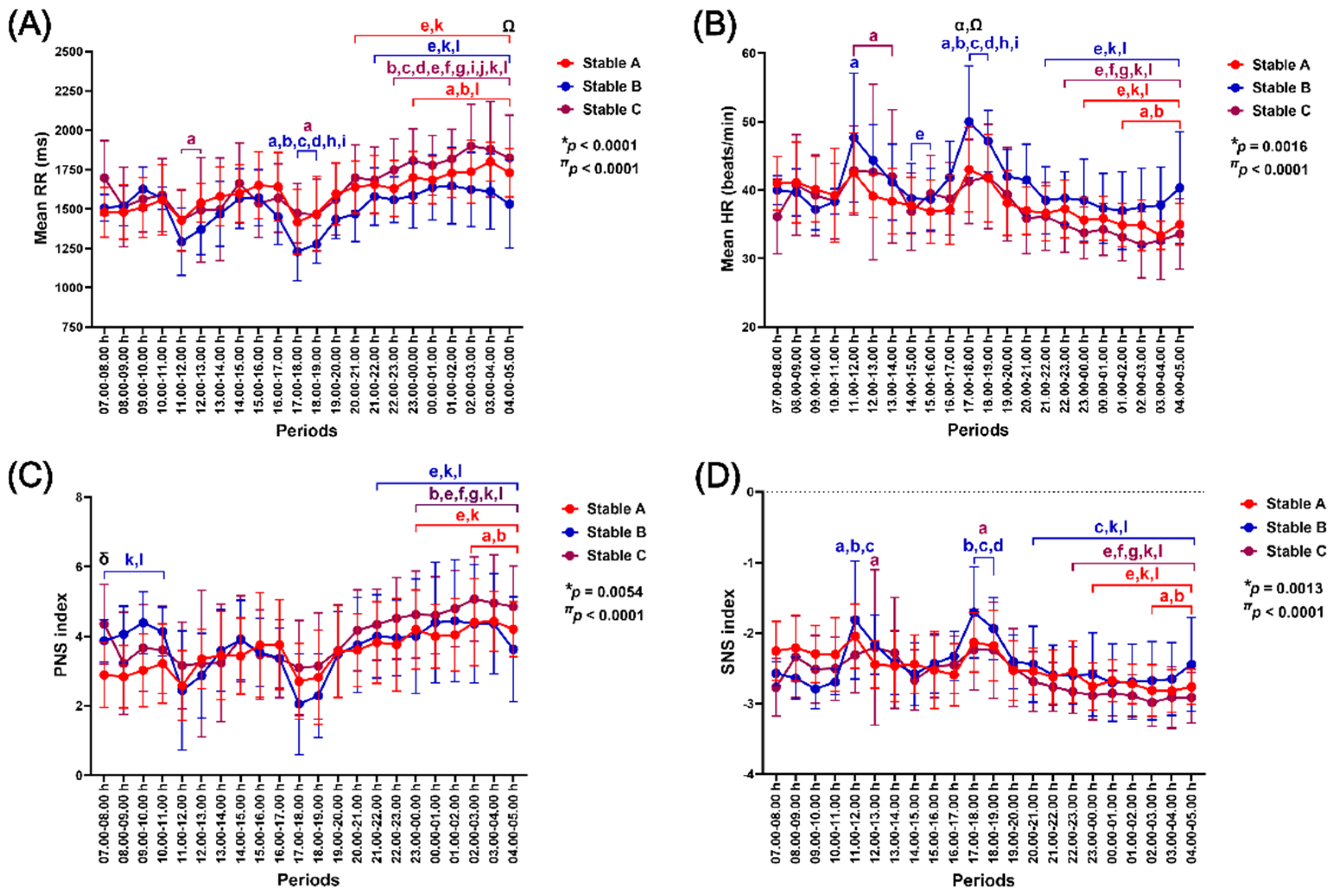

3.5.1. RR Intervals, HR, PNS Index, and SNS Index

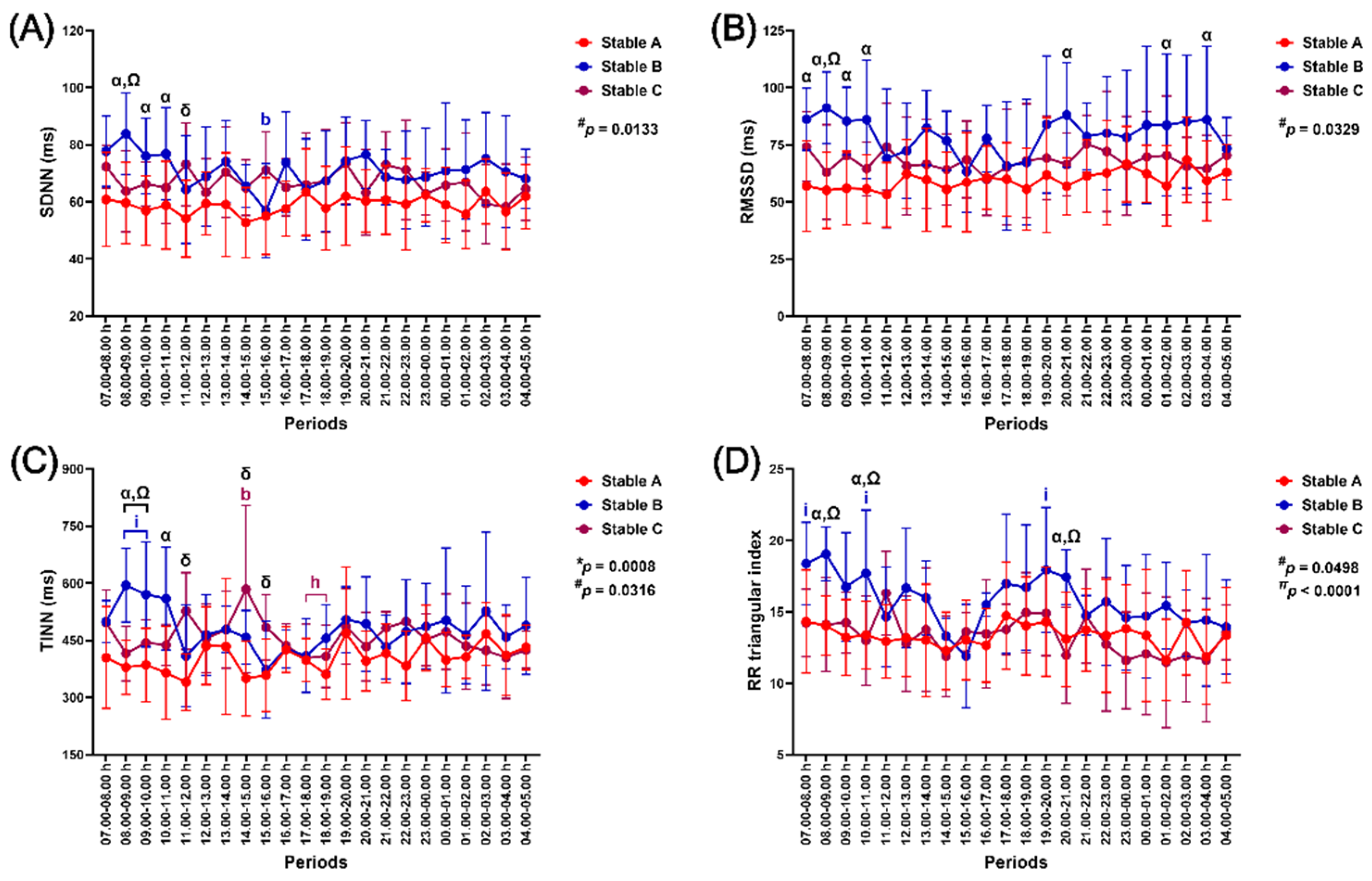

3.5.2. SDNN, RMSSD, TINN, and RRTI

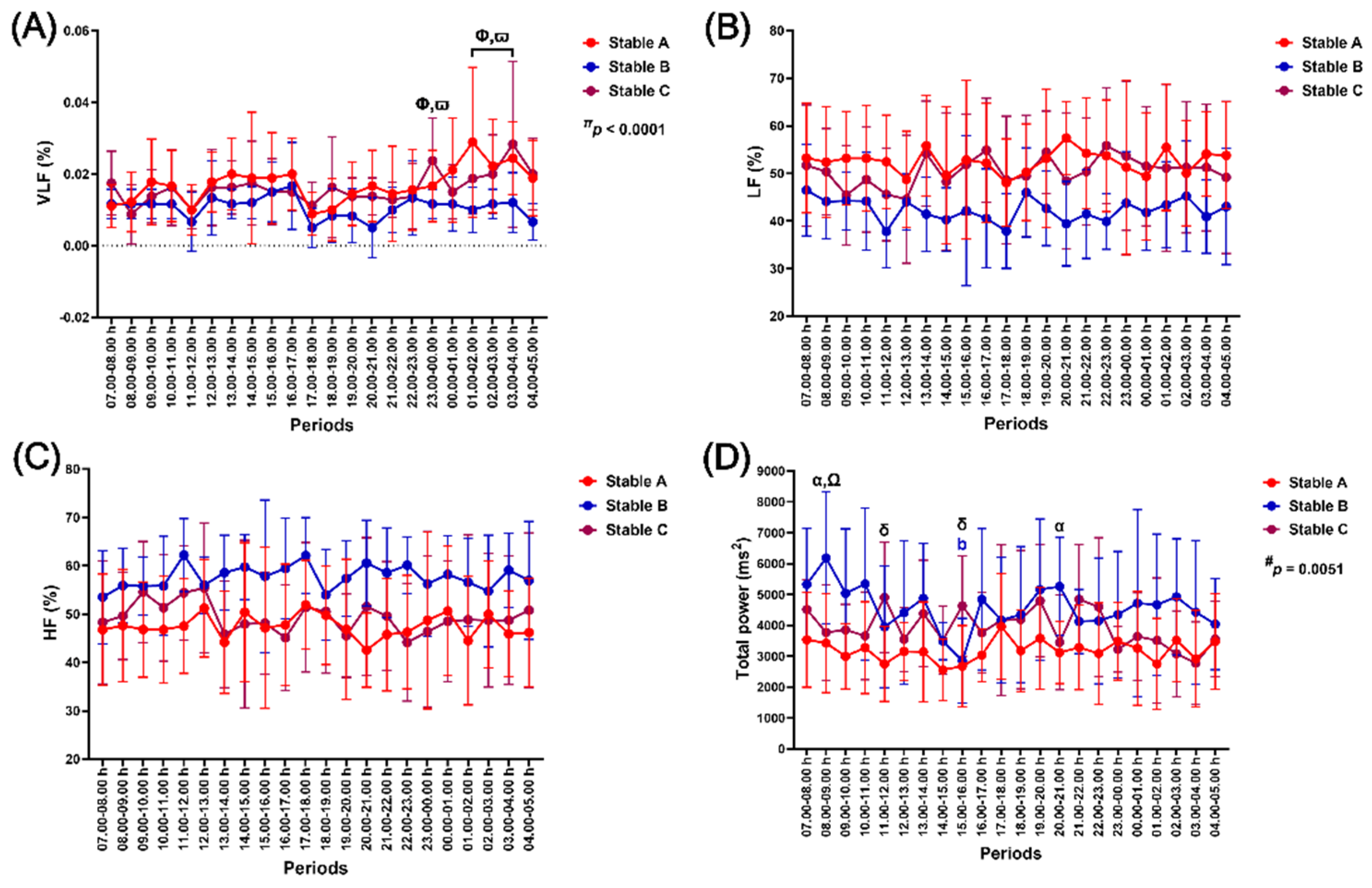

3.5.3. VLF Band, LF Band, HF Band, LF/HF Ratio, and Total Power

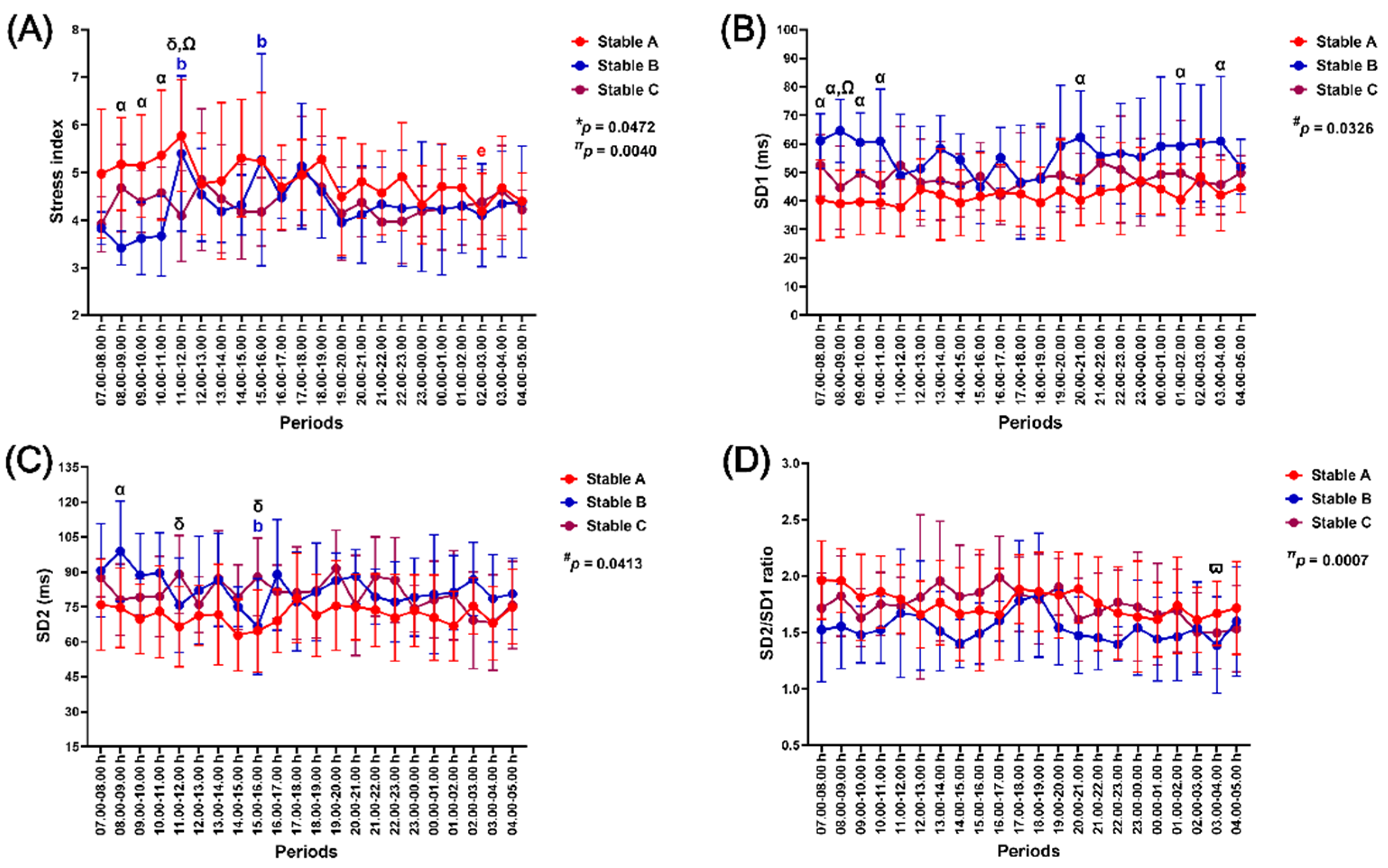

3.5.4. Stress Index, SD1, SD2, and SD2/SD1 Ratio

3.6. Correlation Among Stable Microclimates and Horses’ HRV Variables

3.6.1. Interior vs Exterior Microclimates

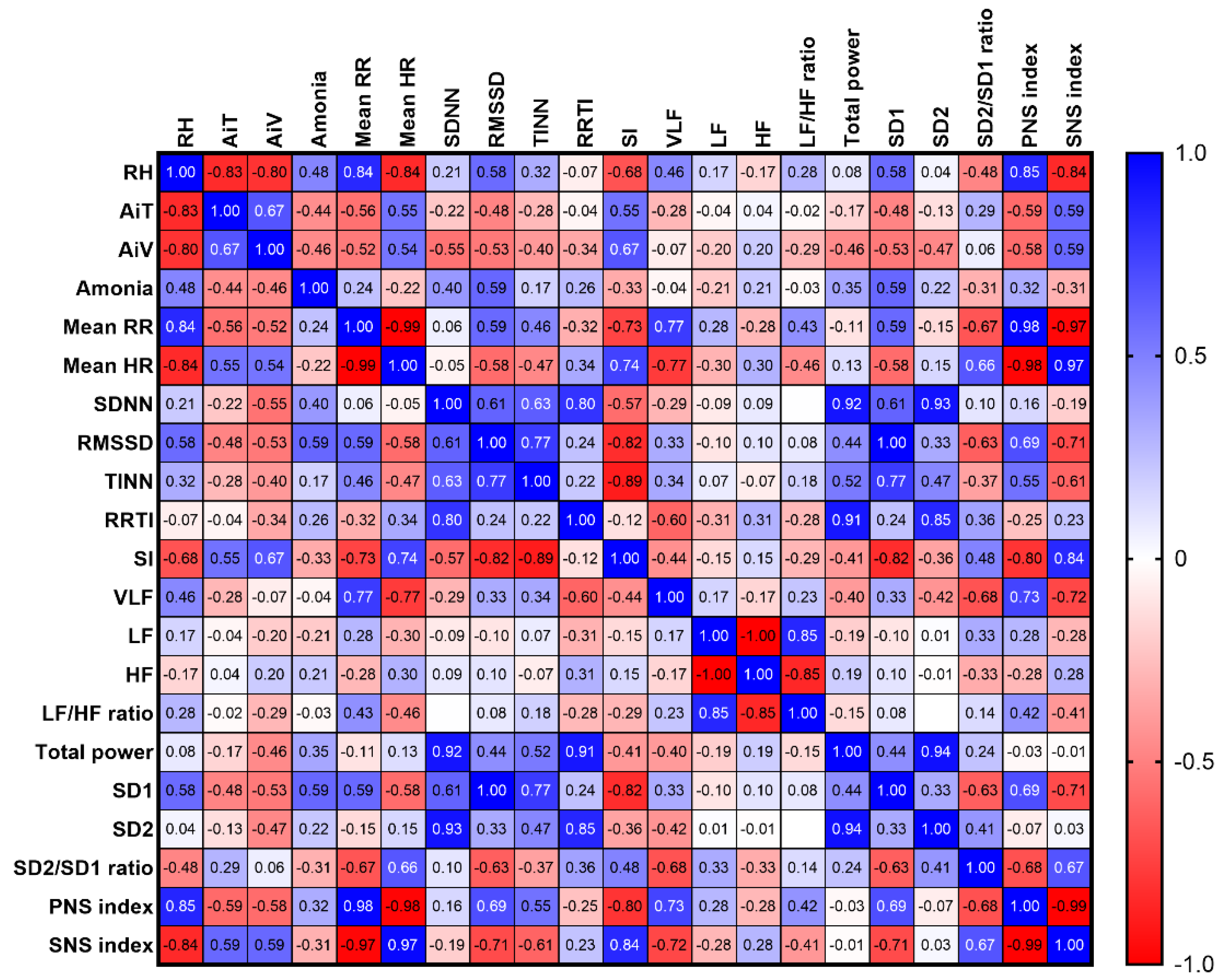

3.6.2. Interior Microclimate vs Horses’ HRV Variables in Stable A

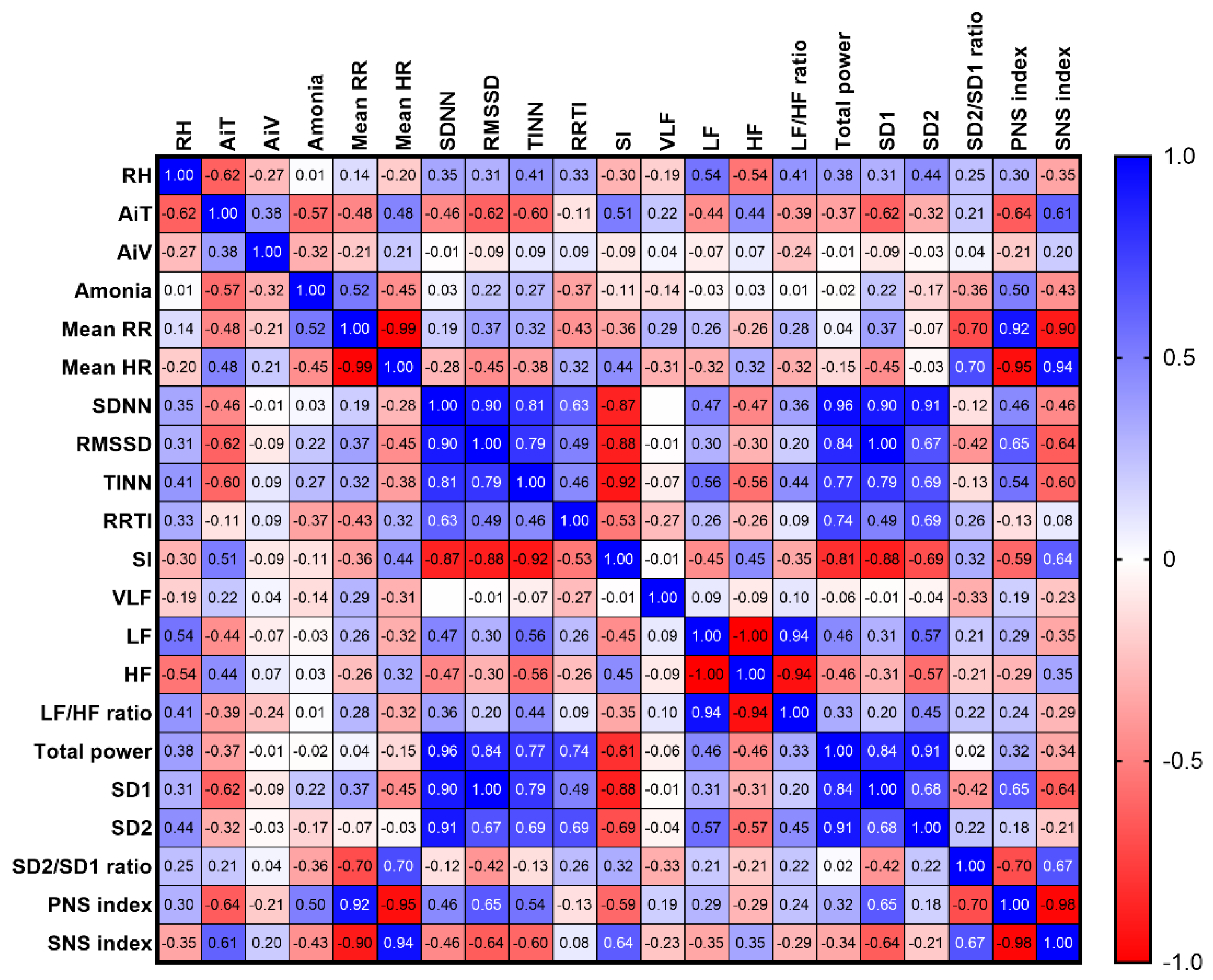

3.6.3. Interior Microclimate vs Horses’ HRV Variables in Stable B

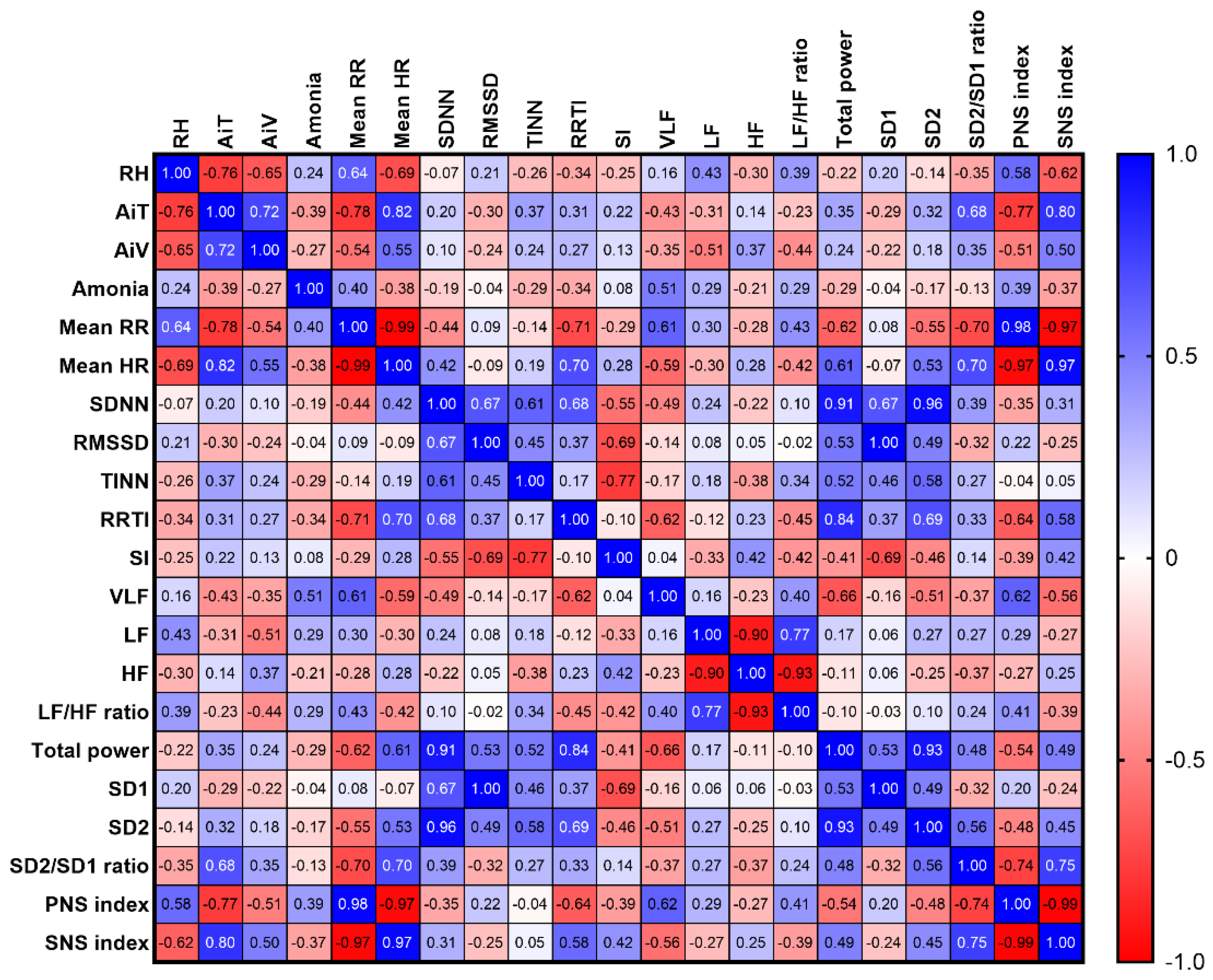

3.6.4. Interior Microclimate vs Horses’ HRV Variables in Stable C

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orlando, L. The evolutionary and historical foundation of the modern horse: lessons from ancient genomics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2020, 54, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klecel, W.; Martyniuk, E. From the Eurasian Steppes to the Roman Circuses: a review of early development of horse breeding and management. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visser, E.K.; Neijenhuis, F.; de Graaf-Roelfsema, E.; Wesselink, H.G.M.; de Boer, J.; van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, M.C.; Engel, B.; van Reenen, C.G. Risk factors associated with health disorders in sport and leisure horses in the Netherlands1. J. Anim. Sci 2014, 92, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Costa, E.; Dai, F.; Lebelt, D.; Scholz, P.; Barbieri, S.; Canali, E.; Minero, M. Initial outcomes of a harmonised approach to collect welfare data in sport and leisure horses. Animal 2017, 11, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, J.B.; Goodwin, D.; Kennedy, M.J.; Davidson, H.P.B.; Harris, P. Foraging enrichment for individually housed horses: Practicality and effects on behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, E.K.; Ellis, A.D.; Van Reenen, C.G. The effect of two different housing conditions on the welfare of young horses stabled for the first time. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Dalla Costa, E.; Minero, M.; Briant, C. Does housing system affect horse welfare? The AWIN welfare assessment protocol applied to horses kept in an outdoor group-housing system: The ‘parcours’. Anim. Welf. 2023, 32, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E.; Søndergaard, E.; Keeling, L.J. Keeping horses in groups: A review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 136, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, D.P.; Parsekian, A.B.H.; Kanaan, V.; Hötzel, M.J. Management, health, and abnormal behaviors of horses: A survey in small equestrian centers in Brazil. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, I.; Stauffacher, M. [Housing and use of horses in Switzerland: a representative analysis of the status quo]. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2002, 144, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.J.Z. Don’t fence me in: managing psychological well being for elite performance horses. J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2007, 10, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. Understanding animal welfare. Acta Vet. Scand. 2008, 50, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; Müller, C.E. Owner reported management, feeding and nutrition-related health problems in Arabian horses in Sweden. Livest. Sci. 2018, 215, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockenhull, J.; Creighton, E. The day-to-day management of UK leisure horses and the prevalence of owner-reported stable-related and handling behaviour problems. Anim. Welf. 2015, 24, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, J.W.; Reid, S.W.J.; Christley, R.M. A survey of horse owners in Great Britain regarding horses in their care. Part 1: Horse demographic characteristics and management. Equine Vet. J. 2007, 39, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yngvesson, J.; Rey Torres, J.C.; Lindholm, J.; Pättiniemi, A.; Andersson, P.; Sassner, H. Health and body conditions of riding school horses housed in groups or kept in conventional tie-stall/box housing. Animals 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruet, A.; Lemarchand, J.; Parias, C.; Mach, N.; Moisan, M.-P.; Foury, A.; Briant, C.; Lansade, L. Housing horses in individual boxes is a challenge with regard to welfare. Animals 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, S.J.; Gretgrix, L. Effect of housing conditions on activity and lying behaviour of horses. Animal 2010, 4, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard, E.; Ladewig, J. Group housing exerts a positive effect on the behaviour of young horses during training. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 87, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.J.; Costa, L.R.; Freeman, L.M. Survey of feeding practices, supplement use, and knowledge of equine nutrition among a subpopulation of horse owners in New England. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2009, 29, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.M.; Cohen, N.D.; Gibbs, P.G.; Thompson, J.A. Feeding practices associated with colic in horses. AVMA 2001, 219, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessoa, G.O.; Trigo, P.; Mesquita Neto, F.D.; Lacreta Junior, A.C.C.; Sousa, T.M.; Muniz, J.A.; Moura, R.S. Comparative well-being of horses kept under total or partial confinement prior to employment for mounted patrols. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 184, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmel, A.I.; Zollinger, A.; Wyss, C.; Bachmann, I.; Briefer Freymond, S. Social box: influence of a new housing system on the social interactions of stallions when driven in pairs. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlen, H.; Krumbach, K.; Thöne-Reineke, C. Keeping stallions in groups—species-appropriate or relevant to animal welfare? Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, L.; Drillich, M.; Klein-Jöbstl, D.; Iwersen, M. Invited review: Influence of climatic conditions on the development, performance, and health of calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2438–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejdell, C.M.; Bøe, K.E.; Jørgensen, G.H.M. Caring for the horse in a cold climate—Reviewing principles for thermoregulation and horse preferences. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 231, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejdell, C.M.; Bøe, K.E. Responses to climatic variables of horses housed outdoors under Nordic winter conditions. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 85, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- contributors, W. Köppen climate classification. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; Mcmahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions 2007, 4, 439–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, O.E.; Uyanga, V.A.; Iyasere, O.S.; Oke, F.O.; Majekodunmi, B.C.; Logunleko, M.O.; Abiona, J.A.; Nwosu, E.U.; Abioja, M.O.; Daramola, J.O.; et al. Environmental stress and livestock productivity in hot-humid tropics: Alleviation and future perspectives. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 100, 103077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Bernabucci, U. Climatic effects on productive traits in livestock. Vet. Res. Commun. 2006, 30, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N. Effects of heat stress on the welfare of extensively managed domestic ruminants. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2000, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, A.L.; De Almeida-Val, V.M.F.; Randall, D.J. Tropical environment. In Fish Physiology; Academic Press: 2005; Volume 21, pp. 1–45.

- Poochipakorn, C.; Wonghanchao, T.; Sanigavatee, K.; Chanda, M. Stress responses in horses housed in different stable designs during summer in a tropical savanna climate. Animals 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- contributors, W. Tropical savanna climate. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia 2024, 1220733028. [Google Scholar]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. 2006, 15, 259–263, https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/link_gateway/2006MetZe..15..259K/10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130.

- Khedari, J.; Sangprajak, A.; Hirunlabh, J. Thailand climatic zones. Renew. Energy 2002, 25, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frippiat, T.; van Beckhoven, C.; Moyse, E.; Art, T. Accuracy of a heart rate monitor for calculating heart rate variability parameters in exercising horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 104, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapteijn, C.M.; Frippiat, T.; van Beckhoven, C.; van Lith, H.A.; Endenburg, N.; Vermetten, E.; Rodenburg, T.B. Measuring heart rate variability using a heart rate monitor in horses (Equus caballus) during groundwork. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 939534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ille, N.; Erber, R.; Aurich, C.; Aurich, J. Comparison of heart rate and heart rate variability obtained by heart rate monitors and simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram signals in nonexercising horses. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, R.; Dowell, F.; Evans, N. Use of the Polar V800 and Actiheart 5 heart rate monitors for the assessment of heart rate variability (HRV) in horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 241, 105401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumlin, K.; Liu, S.; Park, J.-H. Framing future of work considerations through climate and built environment assessment of volunteer work practices in the United States Equine Assisted Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill, S.; Coleman, R.; Jackson, J.; Tumlin, K.; Stanton, V.; Hayes, M. Environmental spatial mapping within equine indoor arenas. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Tang, J.; Caniza, M.; Heraud, J.-M.; Koay, E.; Lee, H.K.; Lee, C.K.; Li, Y.; Nava Ruiz, A.; Santillan-Salas, C.F.; et al. Correlating indoor and outdoor temperature and humidity in a sample of buildings in tropical climates. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 2281–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska-Stenzel, A.; Sowińska, J.; Witkowska, D. Analysis of noxious gas pollution in horse stable air. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2014, 34, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, K.; Hessel, E.F.; Van den Weghe, H.F. Gas and particle concentrations in horse stables with individual boxes as a function of the bedding material and the mucking regimen. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 3805–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, I.; Wilk, I.; Wiśniewska, A.; Kusy, R.; Cikacz, K.; Frątczak, M.; Wójcik, P. Effect of air temperature and humidity in a stable on basic physiological parameters in horses. Animal Sci. Genet. 2020, 16, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Möstl, E.; Wehnert, C.; Aurich, J.; Müller, J.; Aurich, C. Cortisol release and heart rate variability in horses during road transport. Horm. Behav. 2010, 57, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Hödl, S.; Möstl, E.; Aurich, J.; Müller, J.; Aurich, C. Cortisol release, heart rate, and heart rate variability in transport-naive horses during repeated road transport. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2010, 39, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Biau, S.; Möstl, E.; Becker-Birck, M.; Morillon, B.; Aurich, J.; Faure, J.M.; Aurich, C. Changes in cortisol release and heart rate variability in sport horses during long-distance road transport. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2010, 38, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertratanachai, S.; Poochipakorn, C.; Sanigavatee, K.; Huangsaksri, O.; Wonghanchao, T.; Charoenchanikran, P.; Lawsirirat, C.; Chanda, M. Cortisol levels, heart rate, and autonomic responses in horses during repeated road transport with differently conditioned trucks in a tropical environment. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0301885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munsters, C.C.; de Gooijer, J.W.; van den Broek, J.; van, Oldruitenborgh; Oosterbaan, M.S. Heart rate, heart rate variability and behaviour of horses during air transport. Vet. Rec. 2013, 172, 15–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, H.; Hobo, S.; Hiraga, A.; Jones, J.H. Changes in heart rate and heart rate variability during transportation of horses by road and air. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2012, 73, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangsaksri, O.; Wonghanchao, T.; Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Chanda, M. Heart rate and heart rate variability in horses undergoing hot and cold shoeing. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0305031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottin, F.; Barrey, E.; Lopes, P.; Billat, V. Effect of repeated exercise and recovery on heart rate variability in elite trotting horses during high-intensity interval training. Equine Vet. J. 2006, 38, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottin, F.; Médigue, C.; Lopes, P.; Petit, E.; Papelier, Y.; Billat, V.L. Effect of exercise intensity and repetition on heart rate variability during training in elite trotting horse. Int. J. Sports Med. 2005, 26, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, A.; Sage, W.; Hezzell, M.; Smith, S.; Franklin, S.; Allen, K. Heart rate variability during high-speed treadmill exercise and recovery in Thoroughbred racehorses presented for poor performance. Equine Vet. J. 2023, 55, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Birck, M.; Schmidt, A.; Lasarzik, J.; Aurich, J.; Möstl, E.; Aurich, C. Cortisol release and heart rate variability in sport horses participating in equestrian competitions. J. Vet. Behav. 2013, 8, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ille, N.; von Lewinski, M.; Erber, R.; Wulf, M.; Aurich, J.; Möstl, E.; Aurich, C. Effects of the level of experience of horses and their riders on Cortisol release, heart rate and heart-rate variability during a jumping course. Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, C.; Vizesi, Z.; Vincze, A. Heart rate and heart rate variability of amateur show jumping horses competing on different levels. Animals 2021, 11, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangsaksri, O.; Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Wonghanchao, T.; Yalong, M.; Thongcham, K.; Srirattanamongkol, C.; Pornkittiwattanakul, S.; Sittiananwong, T.; Ithisariyanont, B.; et al. Physiological stress responses in horses participating in novice endurance rides. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Huangsaksri, O.; Wonghanchao, T.; Yalong, M.; Poungpuk, K.; Thanaudom, K.; Chanda, M. Hematological and physiological responses in polo ponies with different field-play positions during low-goal polo matches. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0303092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Borell, E.; Langbein, J.; Després, G.; Hansen, S.; Leterrier, C.; Marchant-Forde, J.; Marchant-Forde, R.; Minero, M.; Mohr, E.; Prunier, A. Heart rate variability as a measure of autonomic regulation of cardiac activity for assessing stress and welfare in farm animals—A review. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucke, D.; Große Ruse, M.; Lebelt, D. Measuring heart rate variability in horses to investigate the autonomic nervous system activity – Pros and cons of different methods. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 166, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, A.; Castejón-Riber, C.; Castejón, F.; Rubio, D.M.; Riber, C. Heart rate variability parameters as markers of the adaptation to a sealed environment (a hypoxic normobaric chamber) in the horse. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2019, 103, 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, H.; Hiraga, A.; Aida, H.; Kuwahara, M.; Tsubone, H. Effects of Repeated Atropine Injection on Heart Rate Variability in Thoroughbred Horses. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2001, 63, 1359–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, M.; Hashimoto, S.-i.; Ishii, K.; Yagi, Y.; Hada, T.; Hiraga, A.; Kai, M.; Kubo, K.; Oki, H.; Tsubone, H.; et al. Assessment of autonomic nervous function by power spectral analysis of heart rate variability in the horse. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1996, 60, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Electrophysiology, T.F.o.t.E.S.o.C.t.N.A.S.o.P. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderlei, L.C.M.; Pastre, C.M.; Hoshi, R.A.; Carvalho, T.D.d.; Godoy, M.F.d. Basic notions of heart rate variability and its clinical applicability. Rev. Bras. Cir. Cardiovasc. 2009, 24, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCraty, R.; Shaffer, F. Heart Rate Variability: New Perspectives on Physiological Mechanisms, Assessment of Self-regulatory Capacity, and Health Risk. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2015, 4, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullett, N.; Zajkowska, Z.; Walsh, A.; Harper, R.; Mondelli, V. Heart rate variability (HRV) as a way to understand associations between the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and affective states: A critical review of the literature. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2023, 192, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwahara, M.; Hiraga, A.; Kai, M.; Tsubone, H.; Sugano, S. Influence of training on autonomic nervous function in horses: evaluation by power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Equine Vet. J. 1999, 31, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Huangsaksri, O.; Wonghanchao, T.; Rodkruta, N.; Chanprame, S.; wiwatwongwana, T.; Chanda, M. Comparison of daily heart rate and heart rate variability in trained and sedentary aged horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2024, 137, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).