Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Morphology

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results

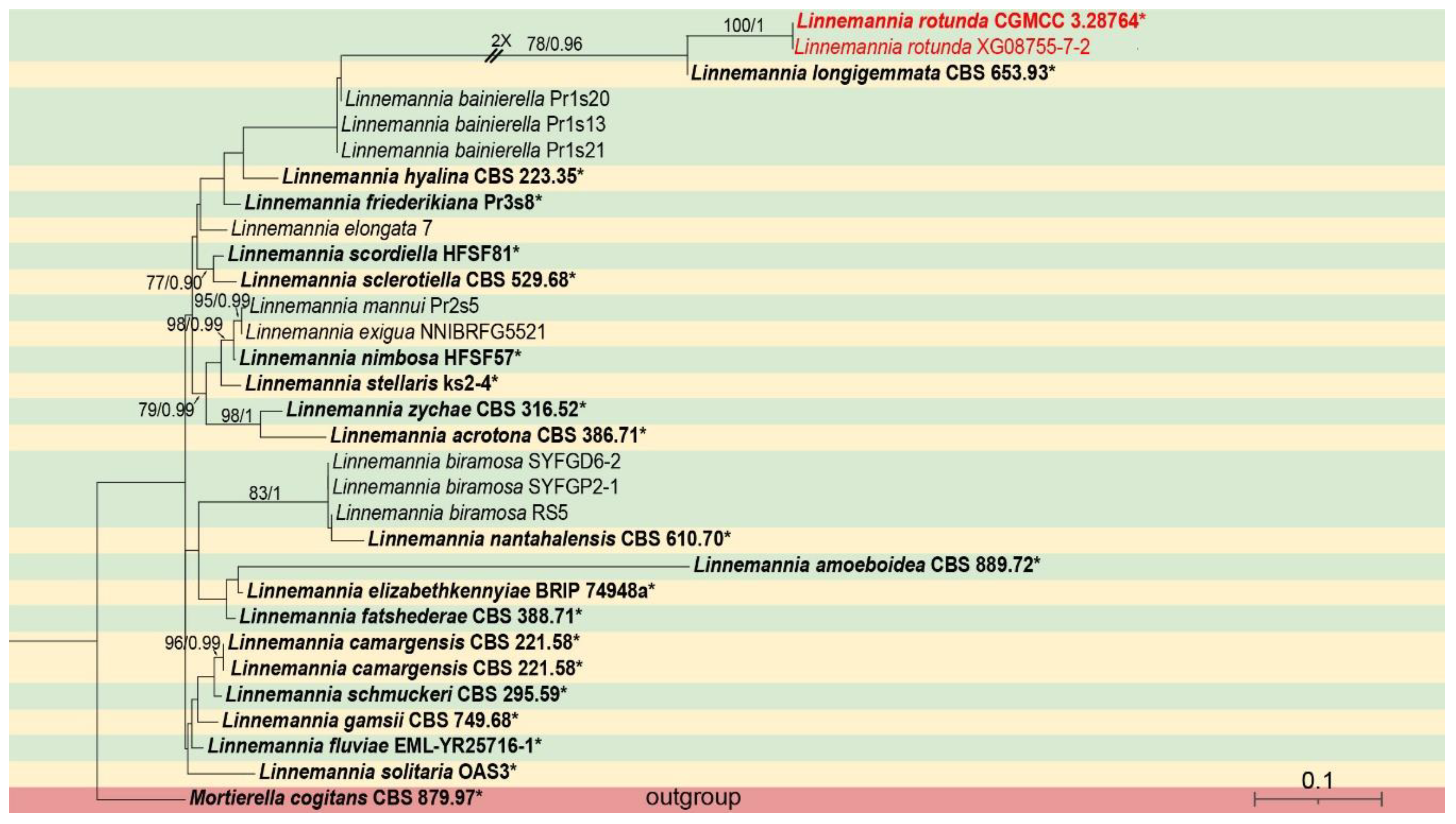

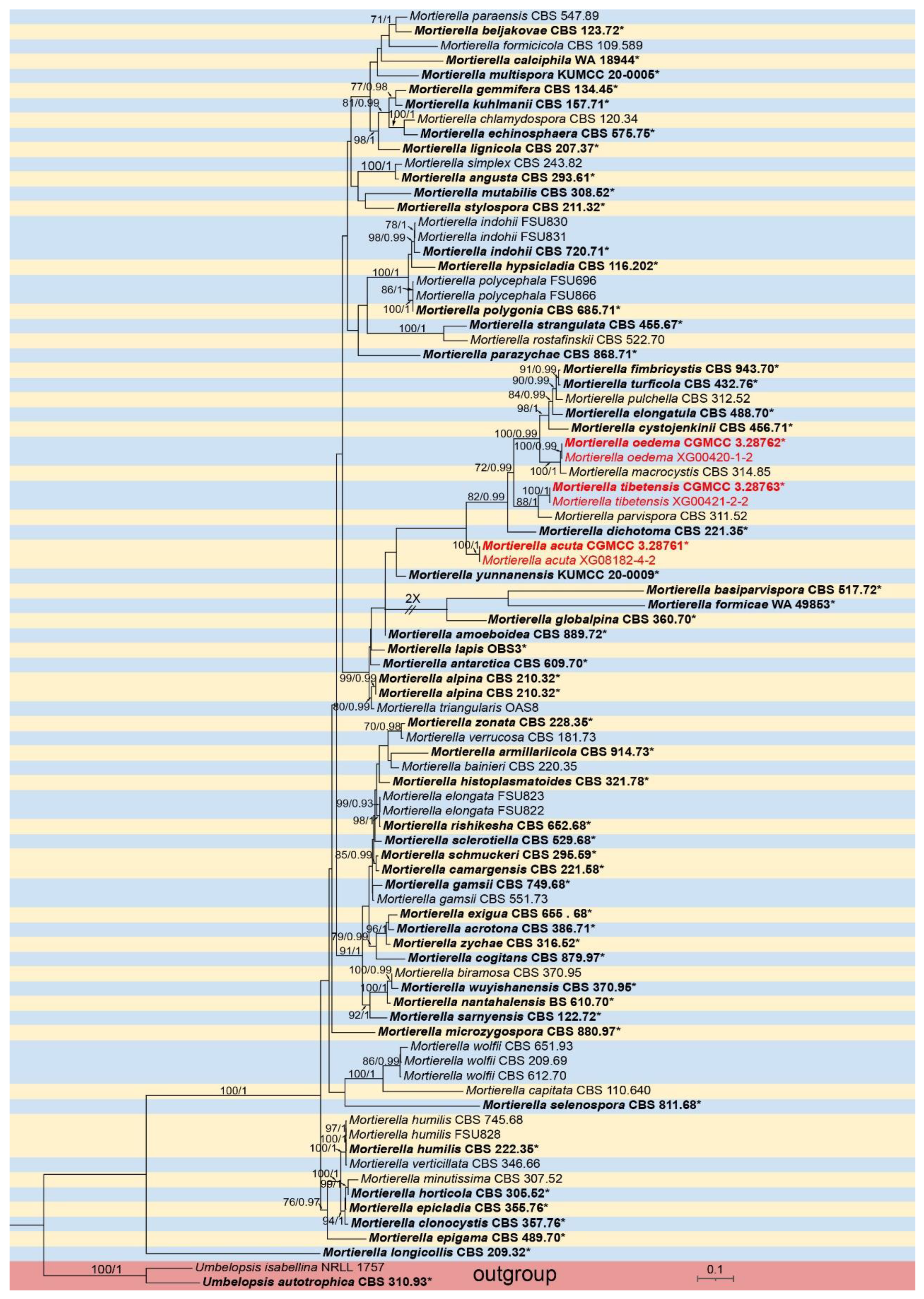

3.1. Molecular Phylogeny

3.2. Taxonomy

3.2.1. Linnemannia rotunda X.Y. Ji, Y. Jiang & X.Y. Liu, sp. nov. Figure 3

3.2.2. Mortierella acuta X.Y. Ji, Y. Jiang & X.Y. Liu, sp. nov. Figure 4

3.2.3. Mortierella oedema X.Y. Ji, Y. Jiang & X.Y. Liu, sp. nov. Figure 5

3.2.4. Mortierella tibetensis X.Y. Ji, Y. Jiang & X.Y. Liu, sp. nov. Figure 6

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflict of interest

Institutional Review Board Statement

Author contributions

Data availability

References

- Wijayawardene, N.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Mikhailov, K.V.; Péter, G.; Aptroot, A.; Pires-Zottarelli, C.L.A.; Goto, B.T.; Tokarev, Y.S.; Haelewaters, D.; Karunarathna, S.C.; et al. Classes and phyla of the kingdom Fungi. Fungal Diversity 2024, 128, 1–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E.; Gryganskyi, A.; Bonito, G.; Nouhra, E.; Moreno-Arroyo, B.; Benny, G. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Modicella reveals an independent evolutionary origin of sporocarp-forming fungi in the Mortierellales. Fungal Genet Biol. 2013, 61, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gams, W. A key to the species of Mortierella. Persoonia 1977, 9, 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Petkovits, T.; Nagy, L.G.; Hoffmann, K.; Wagner, L.; Nyilasi, I.; Griebel, T.; Schnabelrauch, D.; Vogel, H.; Voigt, K.; Vágvölgyi, C.; et al. Data partitions, Bayesian analysis and phylogeny of the zygomycetous fungal family Mortierellaceae, inferred from nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, L.; Stielow, B.; Hoffmann, K.; Petkovits, T.; Papp, T.; Vágvölgyi, C.; de Hoog, G.S.; Verkley, G.; Voigt, K. A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of the Mortierellales (Mortierellomycotina) based on nuclear ribosomal DNA. Persoonia 2013, 30, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnemann, G. Die Mucorineen-Gattung Mortierella Coemans. Pflanzenforschung 1941, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.V.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346, 6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Lv, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. High-throughput sequencing reveals the diversity and community structure of rhizosphere fungi of Ferula sinkiangensis at different soil depths. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnert, R.; Oberkofler, I.; Peintner, U. Fungal growth and biomass development is boosted by plants in snow-covered soil. Microbial Ecology 2012, 64, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, H.L. Biotransformation of organic sulfides. Natural Product Reports 2001, 18, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashiyama, K.; Fujikawa, S.; Park, E.Y.; Shimizu, S. Production of arachidonic acid by Mortierella fungi. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 2002, 7, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.R.; Kim, S.W.; Babu, A.G.; Adhikari, M.; Kim, C.; Lee, H.B.; Lee, L.S. First report of Mortierella alpina (Mortierellaceae, Zygomycota) isolated from crop field soil in Korea. Mycobiology 2014, 42, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Ward, O.P. Production of high yields of arachidonic acid in a fed-batch system by Mortierella alpina ATCC 32222. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 1997, 48, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.Y.; Alvaro, J.; Hyden, B.; Zienkiewicz, K.; Benning, N.; Zienkiewicz, A.; Bonito, G.; Benning, C. Enhancing oil production and harvest by combining the marine alga Nannochloropsis oceanica and the oleaginous fungus Mortierella elongata. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2018, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, L.; Jie, X.; Hu, D.; Feng, B.; Yue, K.; et al. Rare fungus, Mortierella capitata, promotes crop growth by stimulating primary metabolisms related genes and reshaping rhizosphere bacterial community. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2020, 151, 108017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, E.; Hanaka, A. Mortierella species as the plant growth-prmoting fungi present in the agricultural soils. Agriculture 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemshura, O.N.; Shemsheyeva, Z.N.; Sadanov, A.K.; Lozovicka, B.; Kamzolova, S.V.; Morgunov, L.V. Antifungal potential of organic acids produced by Mortierella alpina. International Journal of Engineering & Technology 2018, 7, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telagathoti, A.; Probst, M.; Mandolini, E.; Peintner, U. Mortierellaceae from subalpine and alpine habitats: new species of Entomortierella, Linnemannia, Mortierella, Podila and Tyroliella gen. nov. Stud Mycol. 2022, 103, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Nie, Y.; Huang, B.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China I: three new species of Backusella (Backusellaceae, Mucoromycota). MycoKeys 2024, 109, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.F.; Ding, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, Z.X.; Zhao, H.; Meng, Z.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China II: Three new species of Absidia (Cunninghamellaceae,Mucoromycota) from Hainan Province. MycoKeys 2024, 110, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Tao, M.F.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China III: Six new species and a new record of Gongronella (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucoromycota). MycoKeys 2024, 110, 287–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.Y.; Ji, X.Y.; Tao, M.F.; Liu, W.X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Meng, Z.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China IV: Four new species of Absidia (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucoromycota). MycoKeys 2025. (in review).

- Ji, X.Y.; Ding, Z.Y.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, S.; Huang, B.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China V: Five new species of Absidia (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucoromycota). MycoKeys 2025. (in review).

- Wang, Y.X.; Ding, Z.Y.; Ji, X.Y.; Meng, Z.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China Ⅵ: Four Absidia sp. nov. (Mucorales) in Guizhou and Hainan. Microorganisms 2025. (in review).

- Ding, Z.Y.; Tao, M.F.; Ji, X.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, W.X.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China Ⅶ: Seven new species of Cunninghamella (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucoromycota). J. Fungi 2025. (in review).

- Zou, Y.; Hou, J.; Guo, S.; Li, Z.; Stephenson, S.L.; Pavlov, I.N.; Liu, P.; Li, Y. Diversity of dictyostelid cellular slime molds, including two species new to science, in forest soils of Changbai Mountain, China. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Zou, Y.; Li, S.; Stephenson, S.L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y. Two new species of dictyostelid cellular slime molds in high-elevation habitats on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Lv, M.L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.Z.; Wang, Y.N.; Ju, X.; Song, Z.; Ren, L.Y.; Jia, B.S.; Qiao, M.; et al. High-yield oleaginous fungi and high-value microbial lipid resources from Mucoromycota. BioEnerg. Res. 2021, 14, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corry, J.E.L. Rose bengal chloramphenicol (RBC) agar. In Progress in Industrial Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 431–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses reveal three new species of Phyllosticta (Botryosphaeriales, Phyllostictaceae) in China. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Liu, R.Y.; Liu, S.B.; Mu, T.C.; Zhang, X.G.; Xia, J.W. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses reveal two new species of Sporocadaceae from Hainan, China. MycoKeys 2022, 88, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, F.J.R.M.; Lee, S.H.; Taylor, L.; Shawe-Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications 1990, 31, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurdeal, V.G.; Jones, E.B.G.; Gentekaki, E. Absidia zygospore (Mucoromycetes), a new species from Nan province, Thailand. Studies in Fungi 2023, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, J.W.; Hall, B.D. The origin of red algae: implications for plastid evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1997, 94, 4520–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, K.; Wöstemeyer, J. Reliable amplification of actin genes facilitates deep-level phylogeny. Microbiological Research 2000, 155, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, A. AliView: A fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3276–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Cai, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yu, D.S.; Wang, Z.M.; Liu, X.Y.; Huang, B. Three new species of Conidiobolus sensu stricto from plant debris in eastern China. MycoKeys 2020, 73, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Yu, D.S.; Wang, C.F.; Liu, X.Y.; Huang, B. A taxonomic revision of the genus Conidiobolus (Ancylistaceae, Entomophthorales): Four clades including three new genera. MycoKeys 2020, 66, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), 2010, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Sys. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.; Stielow, B.; Hoffmann, K.; Petkovits, T.; Papp, T.; Vágvölgyi, C.; de Hoog, G.S.; Verkley, G.; Voigt, K. A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of the Mortierellales (Mortierellomycotina) based on nuclear ribosomal DNA. Persoonia 2013, 30, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K.; Telle, S.; Walther, G.; Eckhart, M.; Kirchmair, M.; Prillinger, H.; Prazenica, A.; Newcombe, G.; Dölz, F.; TamásPapp.; et al. Diversity, genotypic identification, ultrastructural and phylogenetic characterization of zygomycetes from different ecological habitats and climatic regions: Limitations and utility of nuclear ribosomal DNA barcode markers. Mycology 2008, 263–312.

- Kuhnert, R.; Oberkofler, I.; Peintner, U. Fungal growth and biomass development is boosted by plants in snow-covered soil. Microbial Ecology 2012, 64, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Stewart, D. Species of Mortierella isolated from soil. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1932, 17, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yuan, H.S.; Zhou, L.W.; Yuan, Y.; Cui, B.K.; Dai, Y.C. Polypore diversity in south China. Mycosystema 2020, 39, 653–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, S.L.; Dai, Y.C.; Jia, Z.F.; Li, T.H.; Liu, T.Z.; Phurbu, D.; Mamut, R.; Sun, G.Y.; Bau, T.; et al. Overview of China’s nomenclature novelties of fungi in the new century (2000-2020). Mycosystema 2021, 40, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, S.C.; Dong, Y.; Karasaki, S.; Tibpromma, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Lumyong, S.; Xu, J.; Sheng, J.; Mortimer, P.E. Discovery of novel fungal species and pathogens on bat carcasses in a cave in Yunnan Province, China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1554–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandepol, N.; Liber, J.; Desirò, A.; Na, H.; Kennedy, M.; Barry, K.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Miller, A.N.; O'Donnell, K.; Stajich, J.E.; Bonito, G. Resolving the Mortierellaceae phylogeny through synthesis of multi-gene phylogenetics and phylogenomics. Fungal Divers. 2020, 104, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLegge, M.J.; Manter, D.K.; Vivanco, J.M. A novel approach to determine generalist nematophagous microbes reveals Mortierella globalpina as a new biocontrol agent against Meloidogyne spp. nematodes. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgington, S.; Thompson, E.; Moore, D.; Hughes, K.A.; Bridge, P. Investigating the insecticidal potential of Geomyces (Myxotrichaceae: Helotiales) and Mortierella (Mortierellacea: Mortierellales) isolated from Antarctica. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Loci | PCR primers | Primer sequence (5’ – 3’) | PCR cycles | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | ITS5 | GGA AGT AAA AGT CGT AAC AAG G | 95 °C 5 min; (95 °C: 30 s, 55 °C: 30 s, 72 °C: 1 min) × 35 cycles; 72 °C 10 min | [32] |

| ITS4 | TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC | |||

| LSU | LR0R | GTA CCC GCT GAA CTT AAG C | 95 °C 5 min; (94 °C: 30 s, 52 °C: 45 s, 72 °C: 1.5 min) × 30 cycles; 72 °C 10 min | [33] |

| LR5 | TCC TGA GGG AAA CTT CG | |||

| RPB1 |

RPB1-Af |

GAR TGY CCD GGD CAY TTY GG |

95 °C 3 min; (94 °C: 40 s, 60 °C: 40 s, 72 °C: 2 min) × 9 (94 °C: 45 s, 55 °C: 1.5 min, 72 °C: 2 min) × 37 cycles; 72 °C 10 min | [34] |

| RPB1-Cr | CCN GCD ATN TCR TTR TCC ATR TA | |||

| Act | ACT-1 | TGG GAC GAT ATG GAI AAI ATC TGG CA | 95 °C 3 min; (95 °C: 60 s, 55 °C: 60 s, 72 °C: 1 min) × 30 cycles; 72 °C 10 min | [35] |

| ACT-4R | TC ITC GTA TIC TIG CTI IGA IAT CCA CA T | |||

| SSU | NS1 | GTA GTC ATA TGC TTG TCT CC | 95 °C 5 min; (94 ℃: 60 s, 54 ℃: 50 s, 72 ℃: 1 min) × 37 cycles; 72 °C 10 min | [32] |

| NS4 | CTT CCG TCA ATT CCT TTA AG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).