Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Strain Isolation

2.2. Morphology and Maximum Growth Temperature

2.3. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

2.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results

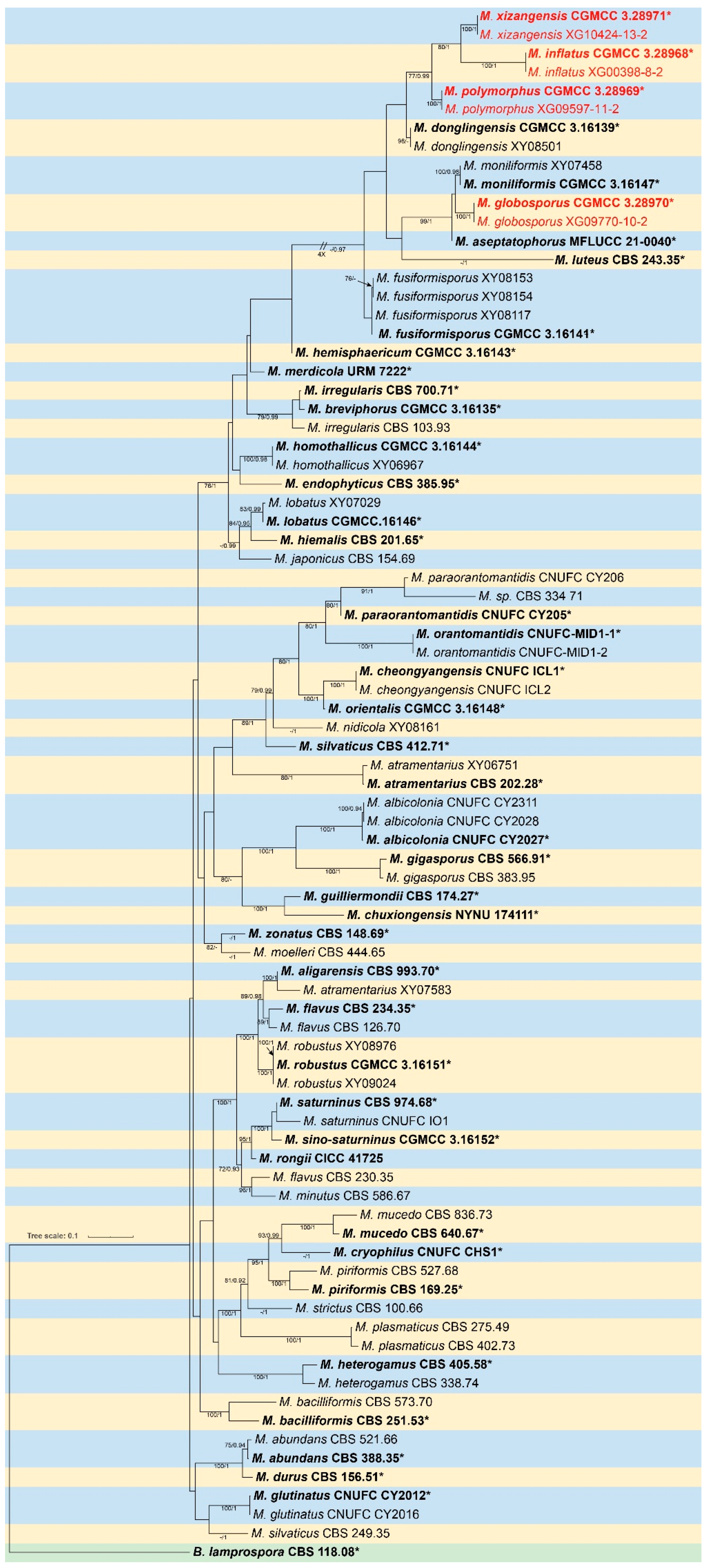

3.1. Phylogeny

3.2. Taxonomy

3.2.1. Mucor globosporus Z.Y. Ding, H. Zhao & X.Y. Liu, sp. nov., Figure 2

3.2.2. Mucor inflatus Z.Y. Ding, H. Zhao & X.Y. Liu, sp. nov., Figure 3

3.2.3. Mucor polymorphus Z.Y. Ding, H. Zhao & X.Y. Liu, sp. nov., Figure 4

3.2.4. Mucor xizangensis Z.Y. Ding, H. Zhao & X.Y. Liu, sp. nov., Figure 5

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicolás, F.E.; Murcia, L.; Navarro, E.; Navarro-Mendoza, M.I.; Pérez-Arques, C.; Garre, V. Mucorales Species and Macrophages. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 94. [CrossRef]

- Spatafora, J.W.; Chang, Y.; Benny, G.L.; L azarus, K.; Smith, M.E.; Berbee, M.L.; Bonito, G.; Corradi, N.; Grigoriev, I.; Gryganskyi, A.; James, T.Y.; OʹDonnell, K.; Roberson, R.W.; Taylor, T.N.; Uehling, J.; Vilgalys, R.; White, M.M.; Stajich, J.E. A phylum-level phylogenetic classification of zygomycete fungi based on genome-scale data. Mycologia 2016, 108, 1028–1046. [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.I.; Hocking, A.D. Fungi and Food Spoilage. Springer: New York, 2009; pp. 151–157.

- Walther, G.; Pawłowska, J.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Wrzosek, M.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L.; Dolatabadi, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; de Hoog, G.S. DNA barcoding in Mucorales: an inventory of biodiversity. Persoonia. 2013, 30, 11–47. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Lee, H.B. Mucor cheongyangensis, a new species isolated from the surface of Lycorma delicatula in Korea. Phytotaxa 2020, 446, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Boonmee, S.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Calabon, M.S.; Huanraluek, N.; Chandrasiri, S.K.U.; Jones, G.E.B.; Rossi, W.; Leonardi, M.; Singh, S.K.; Rana, S.; Singh, P.N.; Maurya, D.K.; Lagashetti, A. C.; Choudhary, D.; Dai, Y. C.; Zhao, C. L.,; Mu, Y. H.; Yuan, H. S.; He, S. H.; Phookamsak, R.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 1387–1511: taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions on genera and species of fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2021, 111, 1–335. [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.X.; De Azevedo Santiago, A.L.C.M.; De Souza-Motta, C.M. Diversity of Mucorales in natural and degraded semi-arid soils. Braz. J. Bot. 2016, 39, 1127–1133. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.A.F.; Lima, D.X.; Gurgel, L.M.S.; de Azevedo Santiago A.L.C.M. Coprophilous Mucorales (ex Zygomycota) from three areas in the semi-arid of Pernambuco, Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Ribes, J.A.; Vanover-Sams, C.L.; Baker, D.J. Zygomycetes in Human Disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 236–301. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Woodgyer, A. Primary cutaneous zygomycosis due to Mucor circinelloides. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2002, 43, 39–42. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, E.; Cano, J.; Stchigel, A.M.; Sutton, D.A.; Fothergill, A.W.; Salas, V.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Guarro, J. Two new species of Mucor from clinical samples. Med. Mycol. 2011, 49, 62–72. [CrossRef]

- Nout, M.J.R.; Aidoo, K.E. Asian Fungal Fermented Food. In: Hofrichter, M. (eds); Industrial applications. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; Volume 10, pp. 29–58. [CrossRef]

- Hermet, A.; Méheust, D.; Mounier, J.; Barbier, G.; Jany, J.L. Molecular systematics in the genus Mucor with special regards to species encountered in cheese. Fungal Biology 2012, 116, 692–705. [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.H.; de Campos-Takaki, G.M.; Okada, K.; Ferreira-Pessoa, I.H.; Milanez, A.I. Detection of extracellular protease in Mucor species. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2005, 22, 114–117. [CrossRef]

- Roopesh, K.; Ramachandran, S.; Nampoothiri, K.M.; Szakacs, G.; Pandey, A. Comparison of phytase production on wheat bran and oilcakes in solid-state fermentation by Mucor racemosus. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 506–511. [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.T.; Zarrini, G.; Mohit, E.; Faramarzi, M.A.; Setayesh, N.; Sedighi, N.; Mohseni, F.A. Mucor hiemalis: A new source for uricase production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 22, 325–330. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, A.K.F.; Faria, E.; Rivaldi, J.D.; Andrade, G.S.S.; Oliveira, P.C.; de Castro, H.F. Performance of whole-cells lipase derived from Mucor circinelloides as a catalyst in the ethanolysis of non-edible vegetable oils under batch and continuous run conditions. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 67, 287–294. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, P.M.; de Assis Bittencourt, M.L.; Caprara, C.C.; de Freitas, M.; de Almeida, R.P.C.; Silveira, D.; Fonseca, Y.M.; Filho, E.X.F.; Junior, A.P.; Magalhães, P.O. A biotechnology perspective of fungal proteases. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2015, 46, 337–346. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, K.; Wolf, T.; Ochsenreiter, K.; Nagy, G.; Kaerger, K.; Shelest, E.; Papp, T. 15 Genetic and metabolic aspects of primary and secondary metabolism of the Zygomycetes. In Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 3rd ed.; Hoffmeister, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Volume III, pp. 361–385. [CrossRef]

- Morin-Sardin, S.; Nodet, P.; Coton, E.; Jany, J.L. Mucor: A Janus-faced fungal genus with human health impact and industrial applications. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2017, 33, 12–32. [CrossRef]

- Fresenius, G. Beiträge zur Mykologie; Bei Heinrich Ludwig Brönner: Frankfurt, Germany, 1850; pp. 1–38.

- Benny, G.L.; Smith, M.E.; Kirk, P.M.; Tretter, E.D.; White, M.M. Challenges and Future Perspectives in the Systematics of Kickxellomycotina, Mortierellomycotina, Mucoromycotina, and Zoopagomycotina. In: Li, D.W. (eds); Biology of Microfungi. Fungal Biology Springer: Cham, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hurdeal, V.G.; Gentekaki, E.; Hyde, K.D.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Lee, H.B. Novel Mucor species (Mucoromycetes, Mucoraceae) from northern Thailand. MycoKeys 2021, 84, 57–78. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Jeon, Y.J.; Mun, H.Y.; Goh, J.; Chung, N.; Lee, H.B. Isolation and Characterization of Four Unrecorded Mucor Species in Korea. Mycobiology 2019, 48, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.X.; Barreto, R.W.; Lee, H.B.; Cordeiro, T.R.L.; de Souza, C.A.F.; de Oliveira, R.J.V.; Santiago, A.L.C.M. Novel Mucoralean Fungus from a Repugnant Substrate: Mucor merdophylus sp. nov., isolated from dog excrement. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2642–2649. [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.L.F.; Lima, D.X.; de Souza, C.A.F.; de Oliveira, R.J.V.; Cavalcanti, I.B.; Gurgel, L.M.S.; Santiago, A. Description of Mucor pernambucoensis (Mucorales, mucoromycota), a new species isolated from the Brazilian upland rainforest. Phytotaxa 2018, 350, 274. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Nie, Y.; Zong, T.; Wang, K.; Lv, M.; Cui, Y.; Tohtirjap, A.; Chen, J.; Zhao, C.; Wu, F.; Cui, B.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, Y.; Liu, X.Y. Species diversity, updated classification and divergence times of the phylum Mucoromycota. Fungal Divers. 2023, 123, 49–157. [CrossRef]

- Walther, G.; Wagner, L.; Kurzai, O. Updates on the Taxonomy of Mucorales with an Emphasis on Clinically Important Taxa. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 106. [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, G.D.; Kaminski, J.S. Psychrophiles, psychrotrophs, and mesophiles in an environment which experiences seasonal temperature fluctuations. Can. J. Microbiol. 1980, 26, 1184–1190. [CrossRef]

- Sandle, T.; Skinner, K. Study of psychrophilic and psychrotolerant micro-organisms isolated in cold rooms used for pharmaceutical processing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013. 114, 1166–1174. [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Species plantarum. Laurentius Salvius, Stockholm, 1753; pp. 1200.

- Wijayawardene, N.N.; Pawłowska, J.; Letcher, P.M.; Kirk, P.M.; Humber, R.A.; Schüßler, A.; Wrzosek, M.; Muszewska, A.; Okrasinka, A.; Istel, L.; Gesiorska, A.; Mungai, P.; Lateef, A.A.; Rajeshkumar, K.C.; Singh, R.V.; Radek, R.; Walther, G.; Wagner, L.; Walker, C.; Wijesundara, D.S.A.; Papizadeh, M.; Dolatabadi, S.; Shenoy, B.D.; Tokarev, Y.S.; Lumyong, S.;Hyde, K.D. Notes for genera: basal clades of Fungi (including Aphelidiomycota, Basidiobolomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Calcarisporiellomycota, Caulochytriomycota, Chytridiomycota, Entomophthoromycota, Glomeromycota, Kickxellomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Mortierellomycota, Mucoromycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Olpidiomycota, Rozellomycota and Zoopagomycota). Fungal Divers. 2018, 92, 43–129. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Lee, H.B. Discovery of Three New Mucor Species Associated with Cricket Insects in Korea. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 601. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Bowling, J.; de Hoog, S.; Aneke, C.I.; Youn, J.H.; Shahegh, S.; Cuellar-Rodriguez, J.; Kanakry, C.G.; Rodriguez, Pena. M.; Ahmed, S.A.; Al-Hatmi, A.M.S.; Tolooe, A.; Walther, G.; Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Kang, Y.Q.; Lee, H.B.; Seyedmousavi, A. Mucor germinans, a novel dimorphic species resembling Paracoccidioides in a clinical sample: questions on ecological strategy. mBio. 2024, 15, e00144–24. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; de A Santiago, A.L.C.M.; Hallsworth, J.E.; Cordeiro, T.R.L.; Voigt, K.; Kirk, P.M.; Crous, P.W.; Júnior, M.A.M.; Elsztein, C.; Lee, H.B. New Mucorales from opposite ends of the world. Stud. Mycol. 2024, 109, 273–321. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Nie, Y.; Huang, B.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China I: three new species of Backusella (Backusellaceae, Mucoromycota). MycoKeys 2024, 109, 285–304. [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.F.; Ding, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, Z.X.; Zhao, H.; Meng, Z.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China II: Three new species of Absidia (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucoromycota) from Hainan Province. MycoKeys 2024, 110, 255–272. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Tao, M.F.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China III: Six new species and a new record of Gongronella. (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucoromycota). MycoKeys 2024, 110, 287–317. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.Y.; Ji, X.Y.; Tao, M.F.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, W.X.; Wang, Y.X.; Meng, Z.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China IV: Four new species of Absidia (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucoromycota). MycoKeys 2025, 119, 29–46. [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.Y.; Ding, Z.Y.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, S.; Huang, B.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity: within early-diverging fungi from China V: Five new species of Absidia (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucoromycota). MycoKeys 2025, 117, 267–288. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Ding, Z.Y.; Ji, X.Y.; Meng, Z.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China VI: Four Absidia sp. nov. (Mucorales) in Guizhou and Hainan. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1315. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.Y.; Tao, M.F.; Ji, X.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Liu, W.X.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China VII: Seven new species of Cunninghamella (Mucoromycota). J. Fungi 2025, 11, 417. [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, F.; Ding, Z.Y.; Meng, Z.; Liu, X.Y. Unveiling species diversity within early-diverging fungi from China VIII: Four new species in Mortierellaceae (Mortierellomycota). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1330. [CrossRef]

- Li, W. X.; Wei, Y. H.; Zou, Y.; Liu, P.; Li, Z.; Gontcharov, A. A.; Stephenson, S. L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S. H.; Li, Y. Dictyostelid cellular slime molds from the Russian Far East. Protist 2020, 171, 125756. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Hou, J.G.; Guo, S.N.; Li, C.T.; Li, Z.; Stephenson, S.L.; Pavlov, I.N.; Liu, P.; Li, Y. Diversity of dictyostelid cellular slime molds, including two species new to science, in forest soils of Changbai Mountain, China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, 02402–22. [CrossRef]

- Corry, J.E.L. Rose bengal chloramphenicol (RBC) agar. In Progress in Industrial Microbiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 431–433.

- Zheng, R.Y.; Chen, G.Q.; Huang, H.; Liu, X.Y. A monograph of Rhizopus. Sydowia 2007, 59, 273–372.

- Zheng, R.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Li, R.Y. More Rhizomucor causing human mucormycosis from China: R. chlamydosporus sp. nov. Sydowia 2009, 61, 135–147.

- Zong, T.K.; Zhao, H.; Liu, X.Y.; Ren, L.Y.; Zhao, C.L.; Liu, X.Y. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the Absidia (Cunninghamellaceae, Mucorales) introducing nine new species and two new combinations from China. Research Square 2021. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.D.; Hyde, K.D.; Liew, E.C.Y. Identification of endophytic fungi from Livistona chinensis based on morphology and rDNA sequences. New Phytol. 2000, 147, 617–630. [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W.; Innis, M.A.; Gelfand, D.H.; Sninsky, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322.

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238-4246. [CrossRef]

- Stiller, J.W.; Hall, B.D. The origin of red algae: implications for plastid evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997, 94, 4520–4525. [CrossRef]

- Nylander, J. MrModeltest V2. program distributed by the author. Bioinformatics 2004, 24, 581–583.

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [CrossRef]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [CrossRef]

- Madden, A.A.; Stchigel, A.M.; Guarro, J.; Sutton. D.; Starks, P.T. Mucor nidicola sp. nov., a fungal species isolated from an invasive paper wasp nest. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 1710–1714. [CrossRef]

| Loci | PCR primers |

Primer sequence (5’ – 3’) | PCR cycles | References |

| ITS | ITS5 ITS4 |

GGA AGT AAA AGT CGT AAC AAG G TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC |

95°C 5 min; (95°C 30 s, 55°C 30 s, 72°C 1 min) × 35 cycles; 72°C 10 min | [51] |

| LSU | LR0R LR7 |

GTA CCC GCT GAA CTT AAG C TAC TAC CAC CAA GAT CT |

95°C 5 min; (95°C 50 s, 47°C 30 s, 72°C 1.5 min) × 35 cycles; 72 °C 10 min | [52] |

| RPB1 | RPB-Af RPB-Cr |

GAR TGY CCD GGD CAY TTY GG CCN GCD ATN TCR TTR TCC ATR TA |

95°C 3 min; (94°C 40 s, 60°C 40 s, 72°C 2 min) × 37 cycles; 72 °C 10 min | [53] |

| Species | Colonies | Sporangiophores | Sporangia | Columellae | Sporangiospores | Chlamydospores | Reference |

| M. globosporus | PDA: 26°C 3 d, 85 mm, 28.3 mm/d, initially white, gradually becoming black-brown, floccose | unbranched, hyaline, 4.8–14.3 µm wide | lobose, pale yellow to light brown, 16.6–76.1 μm diam. | 1.2–5.8 µm long | mostly spherical, 7.3–14 × 7.8–13.4µm, with or without spines, 0.7–1.9 µm long | globose, 6.6–11.3× 6.6–11.2 µm | This study |

| M.inflatus | PDA: 26°C 9 d, 77 mm, 8.56 mm/d, initially white, gradually becoming cream yellow, floccose | unbranched, 5.0–15.8 µm wide | globose, pale yellow to pale brown, 33.8–70.0 μm diam. | globose, ellipsoidal, pyriform, 10.1–40.0 × 7.5–39.7 µm | mainly fusiform and ellipsoidal, occasionally irregular, 5.4–18.0 × 3.3–7.8 µm | ellipsoidal or irregular, 6.3–16.8 × 8.1–12.5 µm | This study |

| M. polymorphus | PDA: 26°C 3 d, 85 mm, 28.3 mm/d, initially white, gradually becoming yellowish-brown, floccose | occasionally branched, 2.2–14.4 µm wide | globose, pale yellow to light brown, 36.7–49.0 μm diam. | globose, ovoid, ellipsoidal, smooth-walled, 5.1–28.3 × 5.8–24.1 µm | fusiform, 3.7–7.0 × 1.9–3.6 µm | in chains, globose, ovoid, cylindrical or irregular, 4.5–17.2 × 3.9–13.9 µm | This study |

| M. xizangensis | PDA: 26°C 3 d, 85 mm, 28.3 mm/d, initially white, gradually becoming grayish-white, floccose | unbranched, 5.0–17.8 µm wide | globose, white to light grayish-brown, 23.3–58.6 μm diam. | globose, ellipsoidal, ovoid, pyriform, 7.9–30.1 × 7.7–29.4 µm | usually ellipsoidal, 3.9–8.4 × 2.4–4.9 µm | mainly globose, 4.0–11.1 × 3.9–10.7 µm | This study |

| M. moniliformis | PDA: 27°C 5 d, 90 mm, 10 mm high, floccose, granulate, initially white soon becoming buff-yellow, reverse irregular at margin | simply branched, somewhere slightly constricted, 6.0–13.5 μm wide | globose, light brown or dark brown when old, 18.0–64.5 μm diam. |

subglobose and globose, 15.0–30.5 × 17.0–32.0 μm | ovoid, hyaline or subhyaline, 3.5–5.5 × 2.5–3.5 μm | in chains, ellipsoidal, ovoid, subglobose, globose or irregular, 5.5–17.0 × 7.0–15.5 μm | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).