Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

- one of the most relevant and widespread areas today to ensure sustainable production of Portland cement and energy conservation, solving environmental problems is the replacement of part of the clinker in Portland cement with natural active mineral additives;

- Portland cement with active mineral additives is an easily produced and in-demand material today;

- research on the development of composite cements is aimed not only at reducing the cost of Portland cement, improving environmental conditions, but also at ensuring high quality of the resulting products and using local reserves of available raw materials.

2.2. Experimental Setup for Thermal Treatment of Oil-Contaminated Soil

- (1)

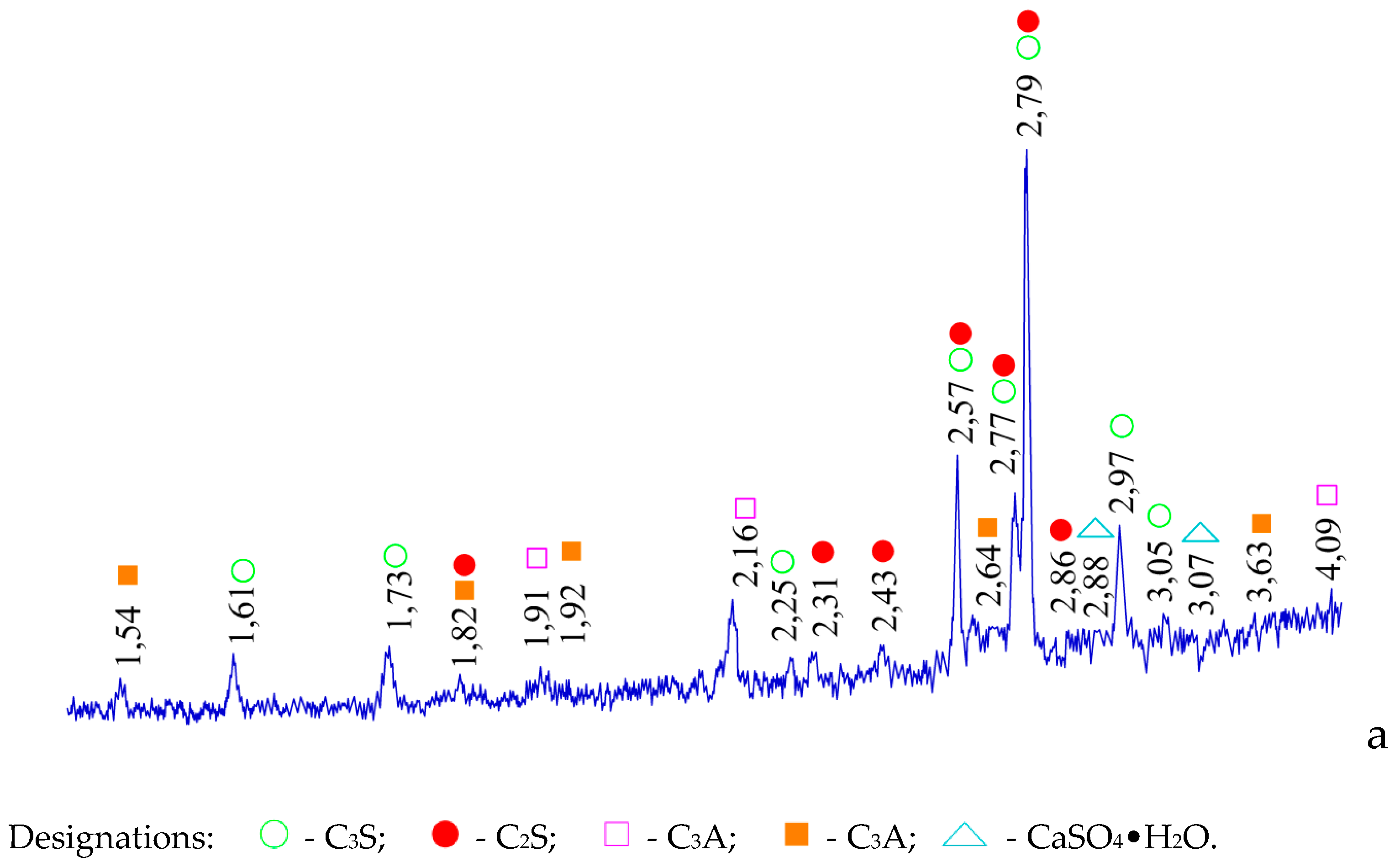

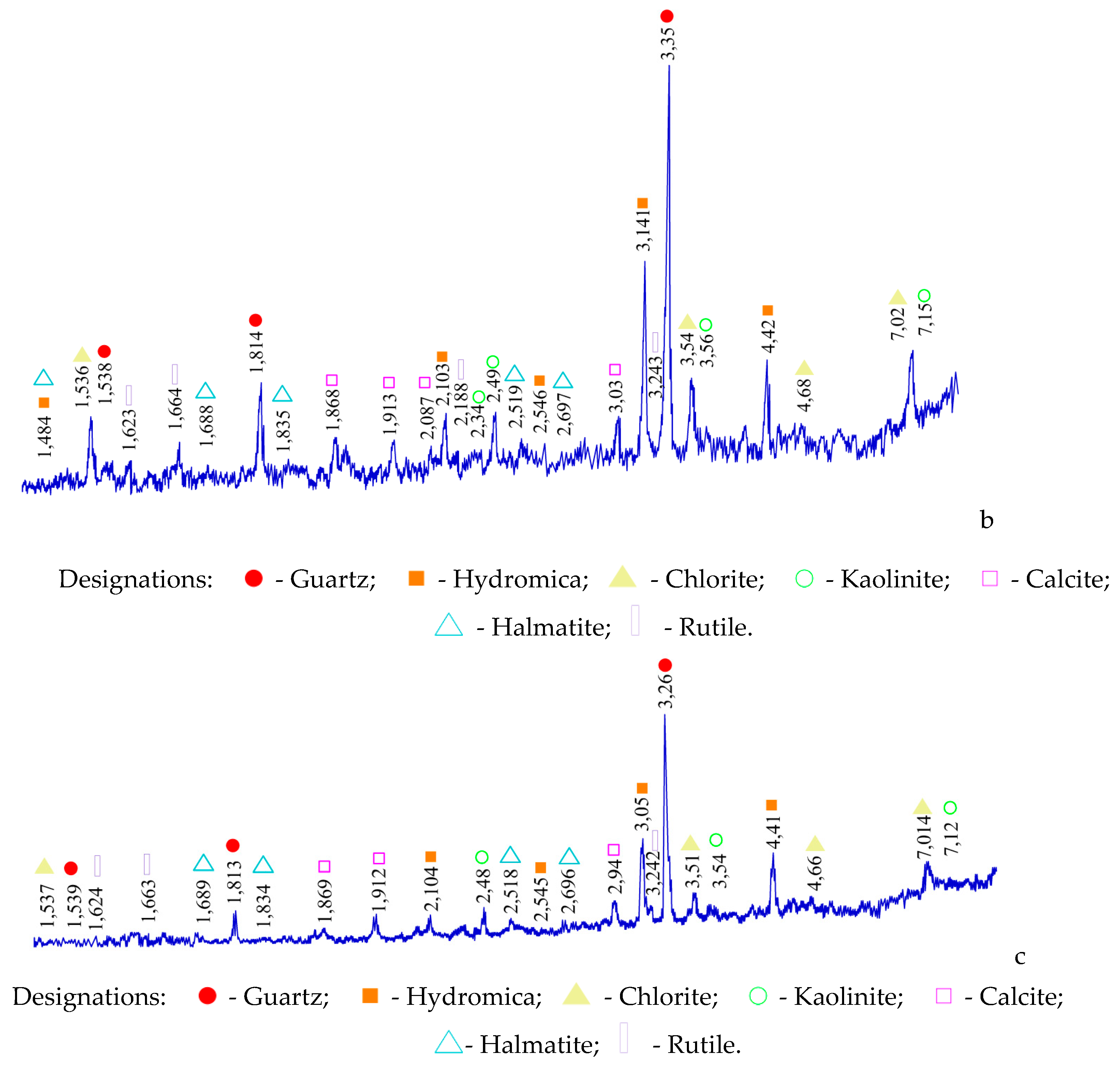

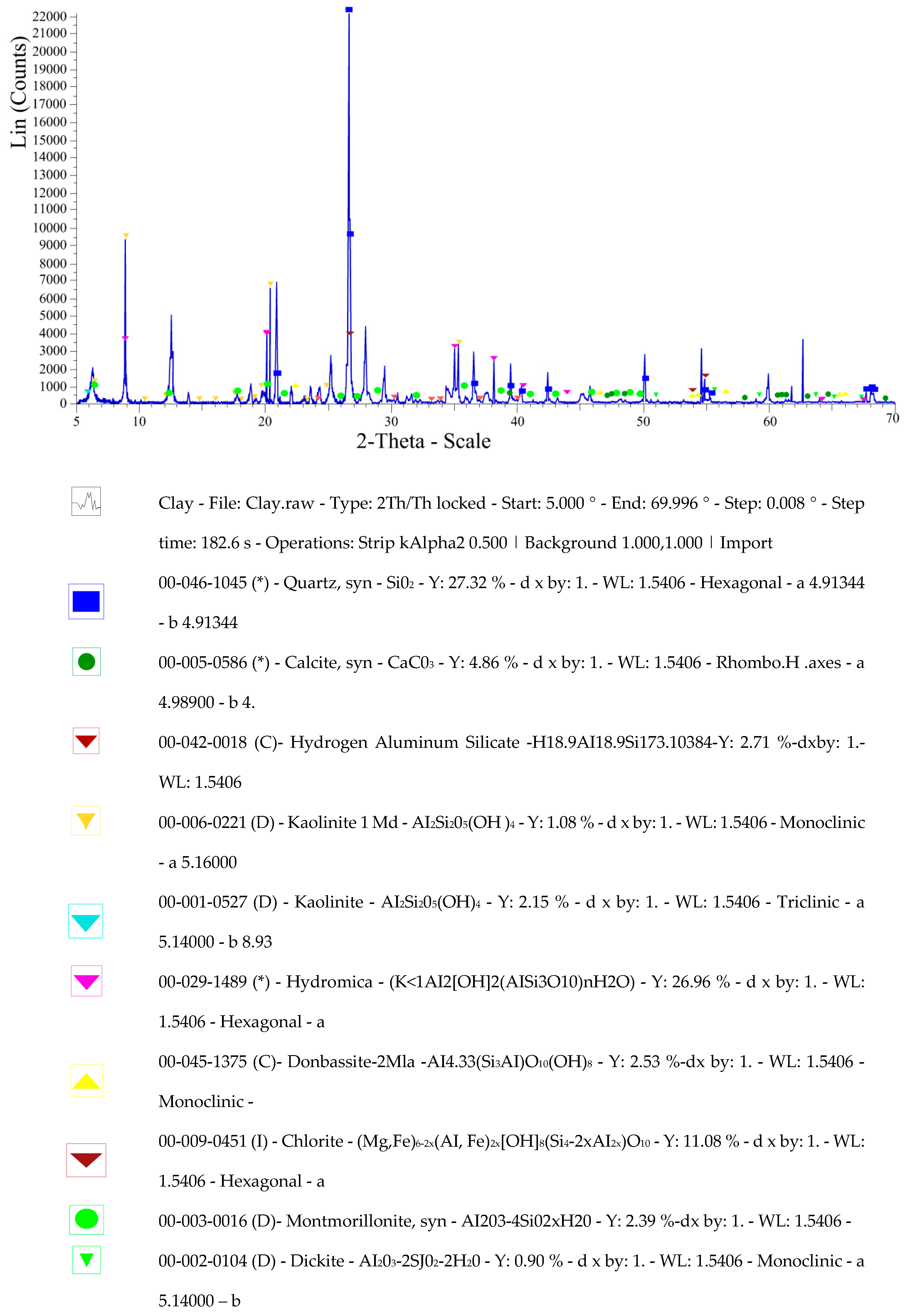

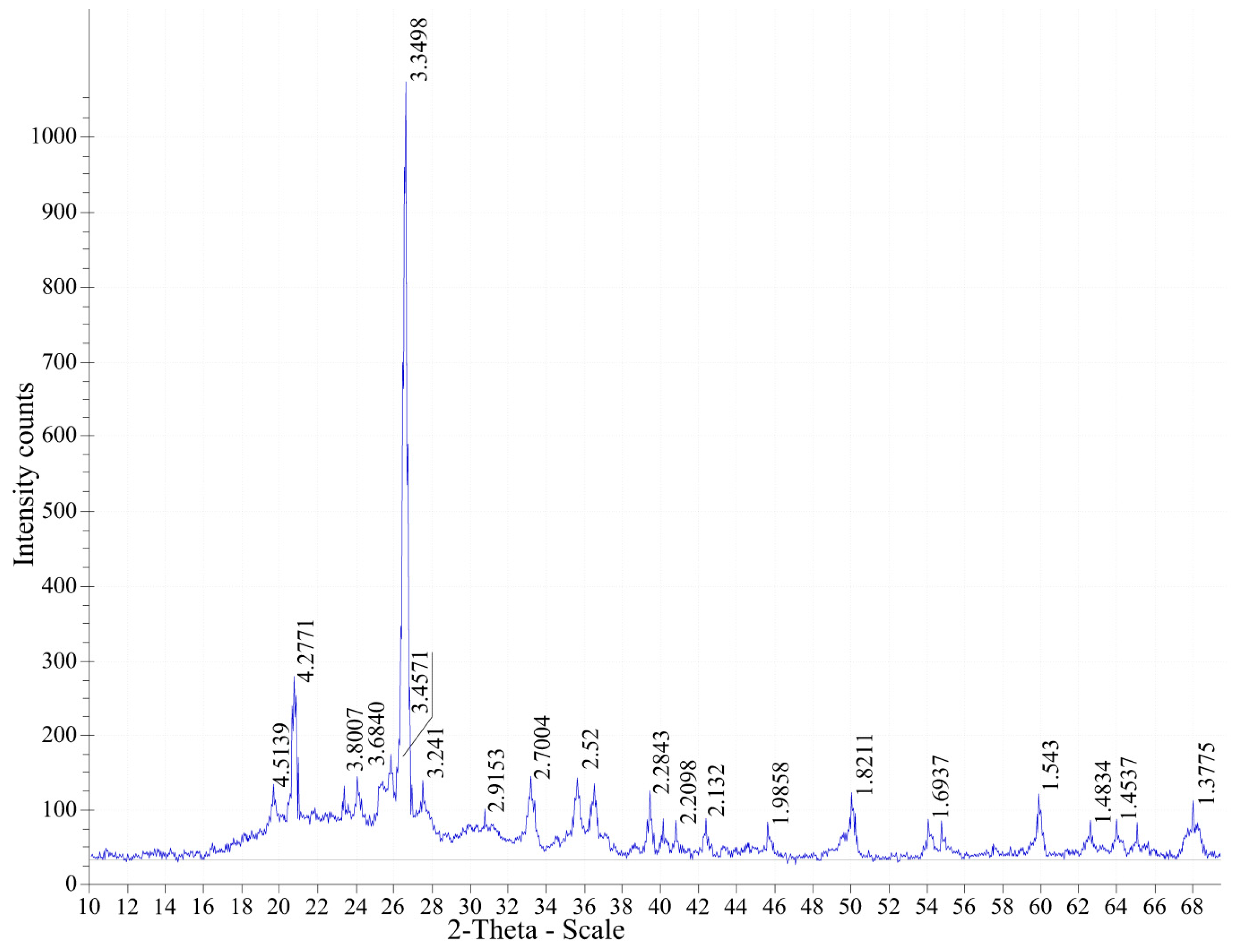

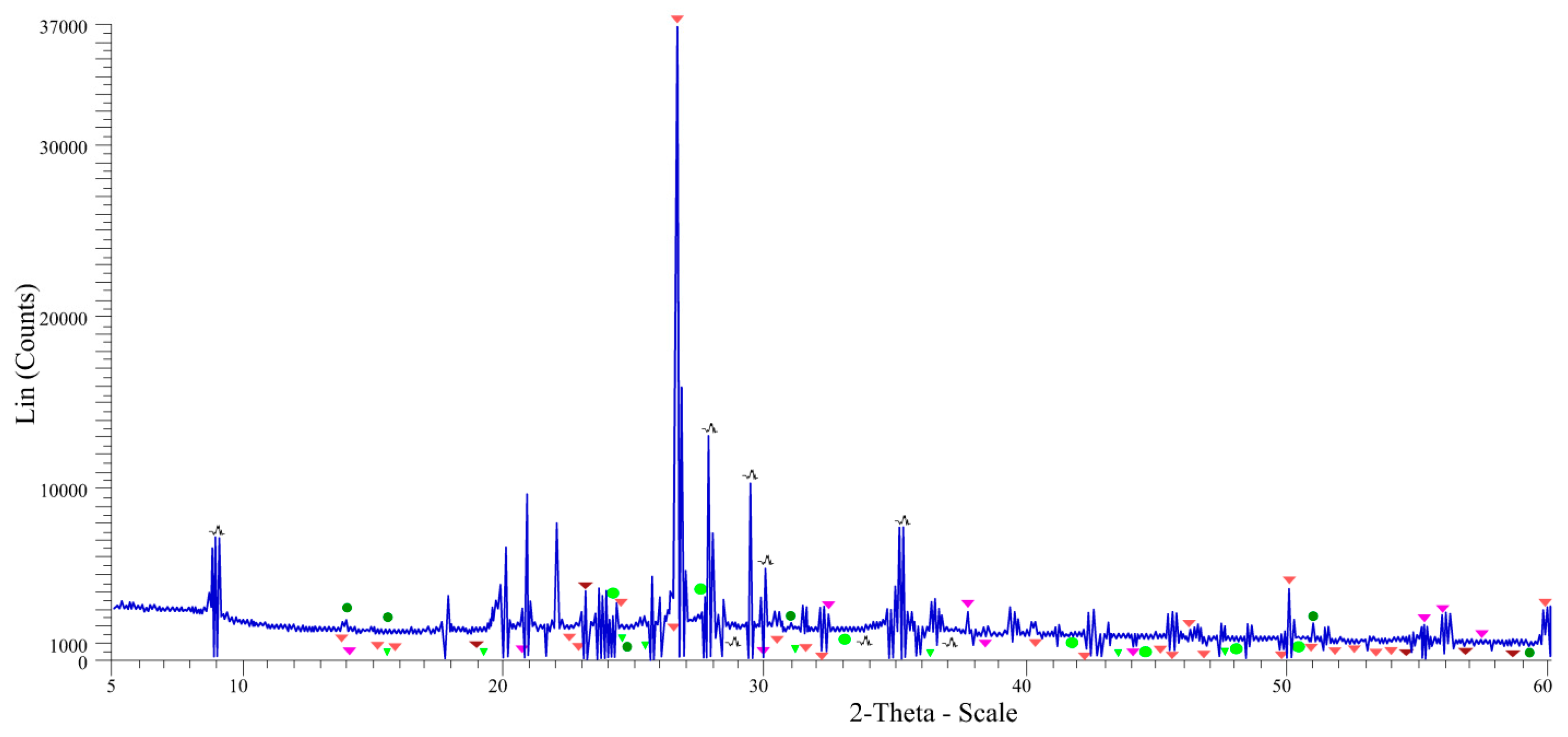

- 00-046-1045(*), quartz – SiO2,. Y: 27.32 %, d x by: 1. d/n – 3.34; 4.26; 2.45; 2.27; 2.12; 1.813; 1.534;1.372; 1.380 Å WL: 1.5406, syngony: hexagonal. Unit cell indices: a - 4.91370, b - 4.91370, c - 5.40470. ɑ = 90, β = 90, γ = 120.

- (2)

- 00-005-0586 (*), calcite – СаСО3, Y: 4.40 %, d x by: 1. d/n – 3.029; 1.0444; 1.869; 1.912; 2.088 Å. WL: 1.5406, syngony: rhombohedral. Unit cell indices: a - 4.98900, b - 4.98900, c - 17.06200. ɑ = 90, β = 90, γ = 120.

- (3)

- 00-042-0018 (C), hydroaluminosilicate – H - 18.9, Al -18.9, Si - 173.1, O–384; Y: 2,71 %, d x by: 1. WL: 1.5406. d/n - 4.41; 1.483; 2.57Å.

- (4)

- 00-006-0221 (D), kaolinite 1 Md - Al2Si2O5(OH)4, Y: 1.08 %, d x by: 1. d/n – 7.14; 3.556; 1.486; 2.330; 1.336 Å. WL: 1.5406, monoclinic syngony. Unit cell indices: a - 5.18000, b - 9.02000, c - 20.04000. ɑ = 90, β = 95.5, γ = 90.

- (5)

- 00-001-0527 (D), kaolinite - Al2Si2O5(OH)4, Y: 2.15 %, d x by: 1. d/n – 7.14; 3.556; 1.486; 2.330; 1.336 Å. WL: 1.5406, triclinic syngony. Unit cell indices: a - 5.18000, b - 9.02000, c - 20.04000. ɑ = 90, β = 95.5, γ = 90.

- (6)

- 00-029-1489 (*), hydromica - (K<1Al2[OH]2(AlSi3O10)⋅nH2O), Y: 26.96 %, d x by: 1. d/n – 4.41; 1.484; 2.545; 2.104; 2.351Å.WL: 1.5406, syngony – hexagonal. Unit cell indices: a - 5.16280, b - 8.96200, c - 19.97700. ɑ = 90.000, β = 95.738, γ = 90.000.

- (7)

- 00-045-1375 (C), donbassite – Al4.33(Si3Al)O10(OH)8, Y: 2.53 %, d x by: 1. d/n – 4.80; 3.536; 2.334; 2.834; 1.662 Å. WL: 1.5406, syngony – monoclinic.

- (8)

- 00-029-1489 (І), chlorite - (Mg,Fe)6-2x(Al, Fe)2x[OH]8(Si4-2xAl2x)O10, d/n – 4.41; 1.483; 2.57.Y: 11.08 %, d x by: 1. WL: 1.5406, syngony – hexagonal. Unit cell indices: a - 8.14400, b - 12.98900, c - 7.16000. ɑ = 92.100, β = 116.560, γ = 90.210.

- (9)

- 00-003-0016 (D), montmorillonite - Al2O3·4SiO2·xH2O, Y: 2.39 %, d x by: 1. d/n –4.45; 1.495; 2.576; 1,697 Å.WL: 1.5406.

- (10)

- 00-002-0104 (D), dickite - Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O, Y: 0.90 %, d x by: 1. d/n – 7.24; 3.59; 2.347; 1.659; 1.323Å.WL: 1.5406, syngony – monoclinic.

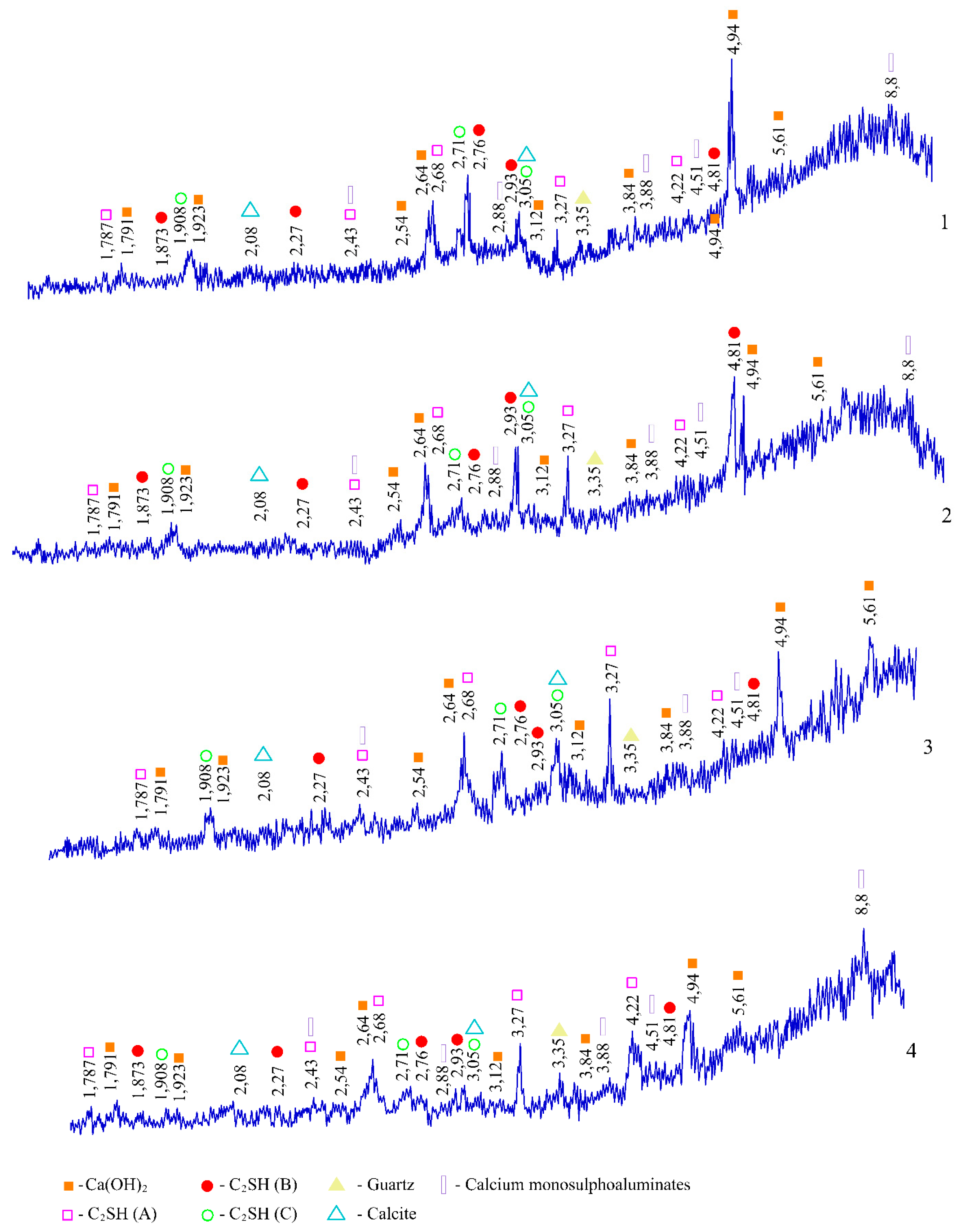

3. Results and Discussion

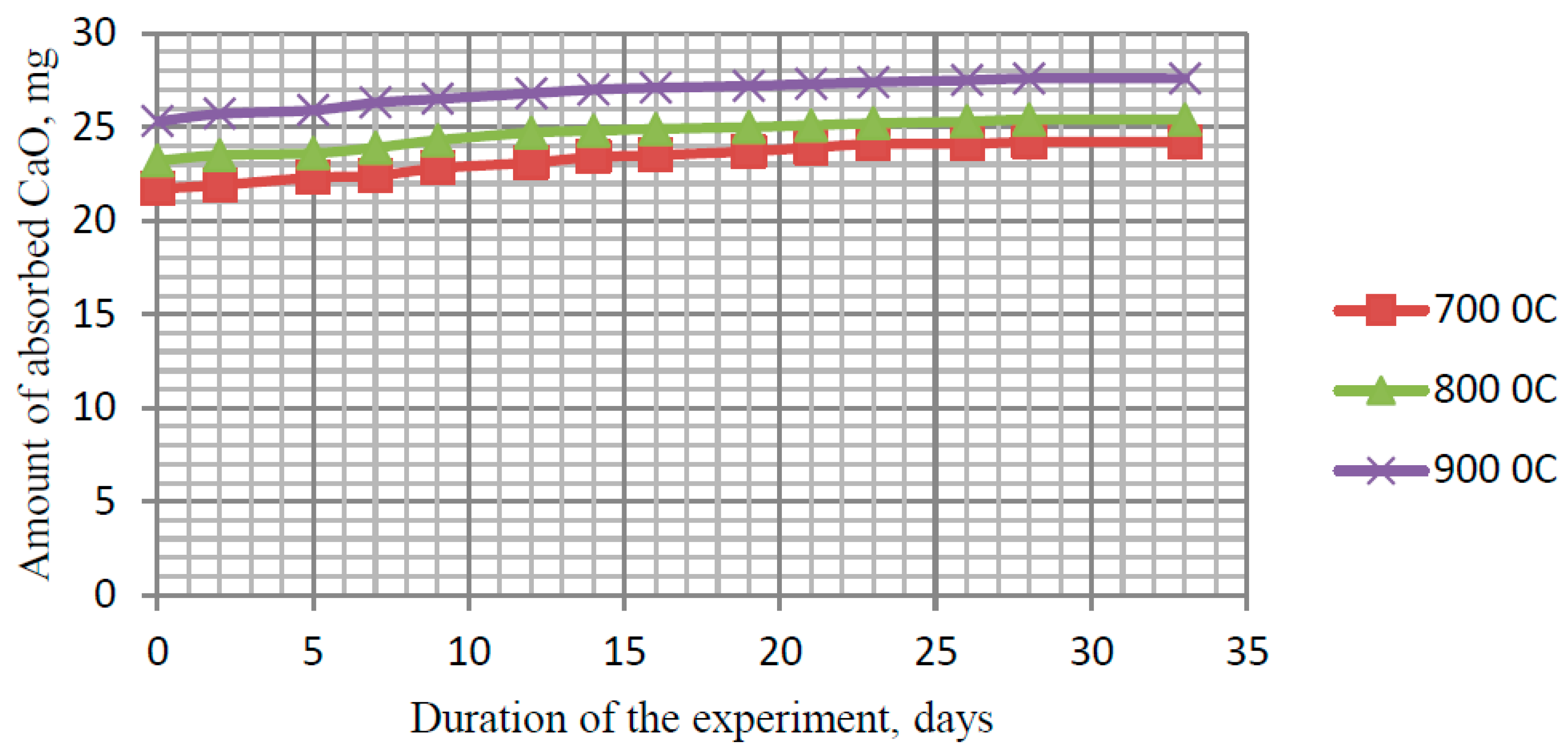

3.1. Determination of the Activity of Mineral Additives by the Classical Method

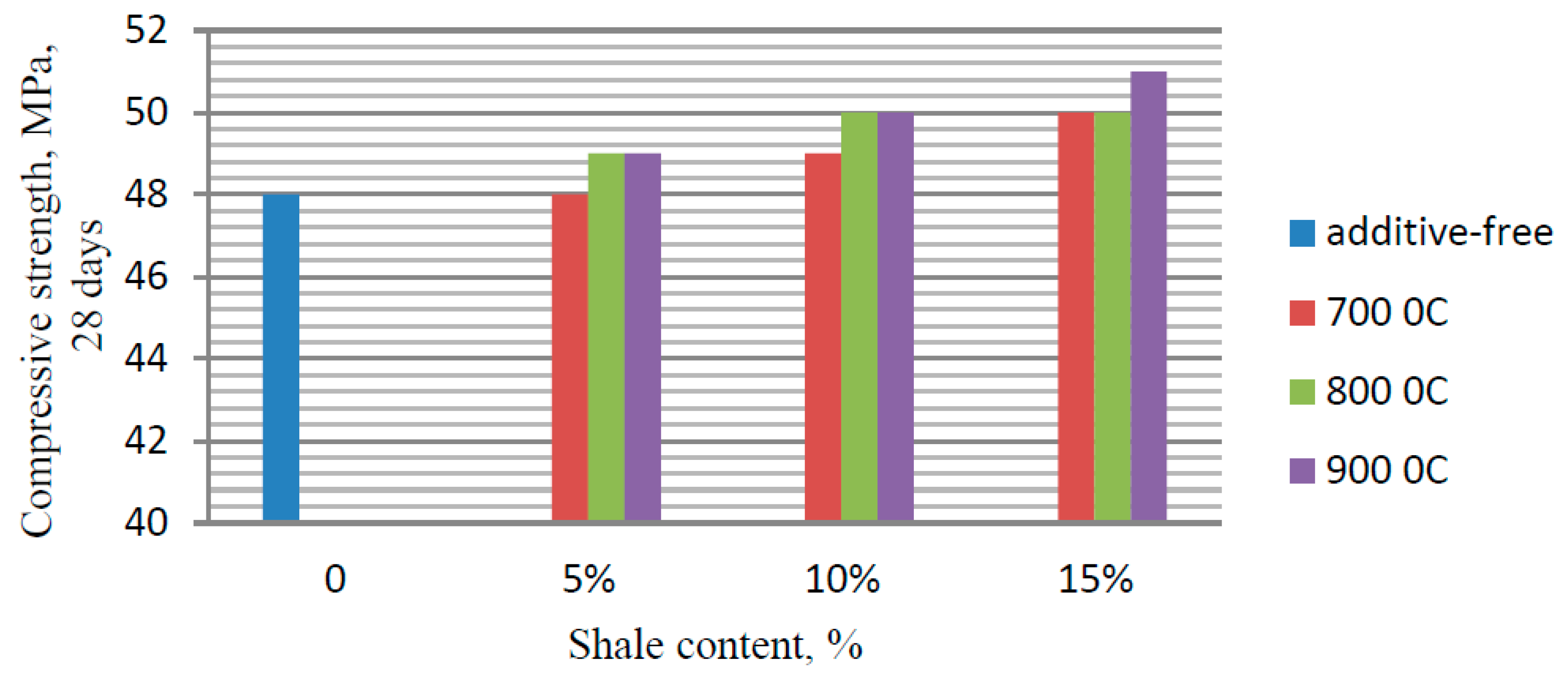

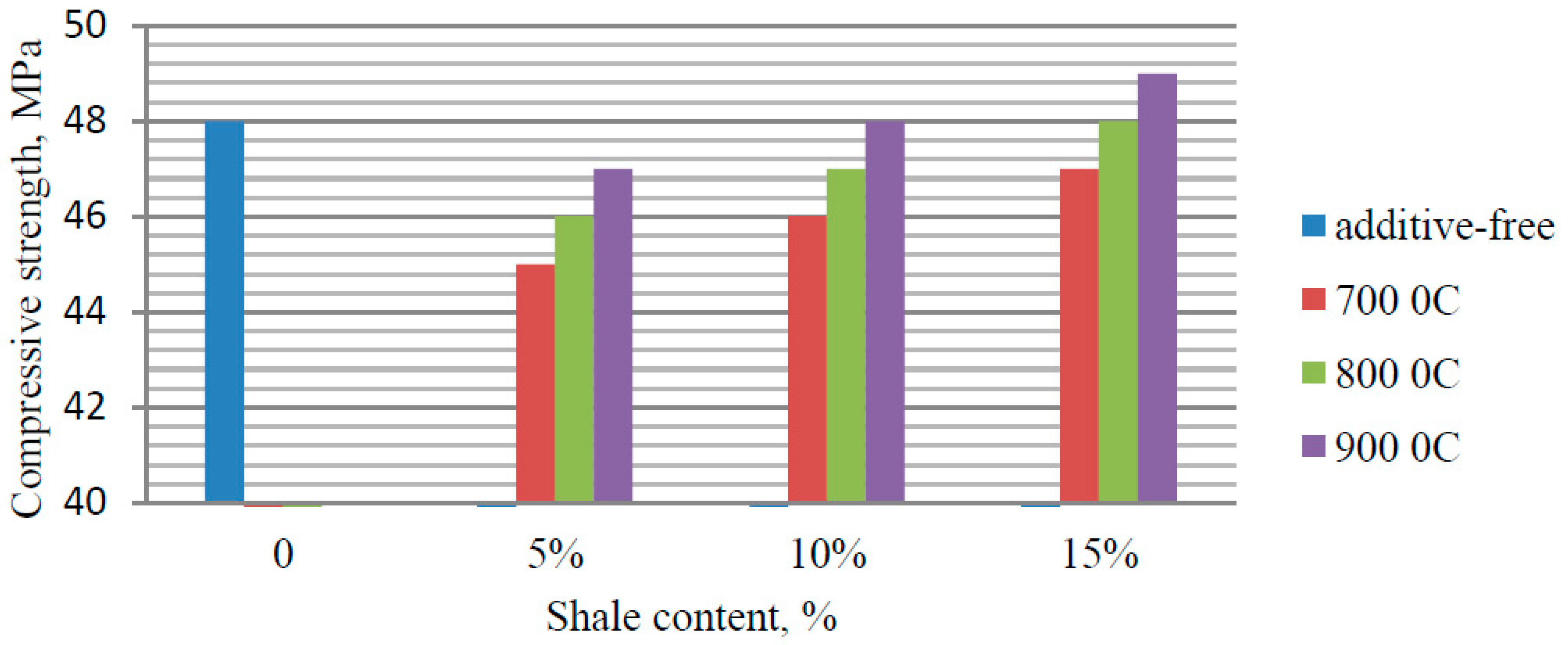

3.1.1. Physical and Mechanical Testing of Composite Cements

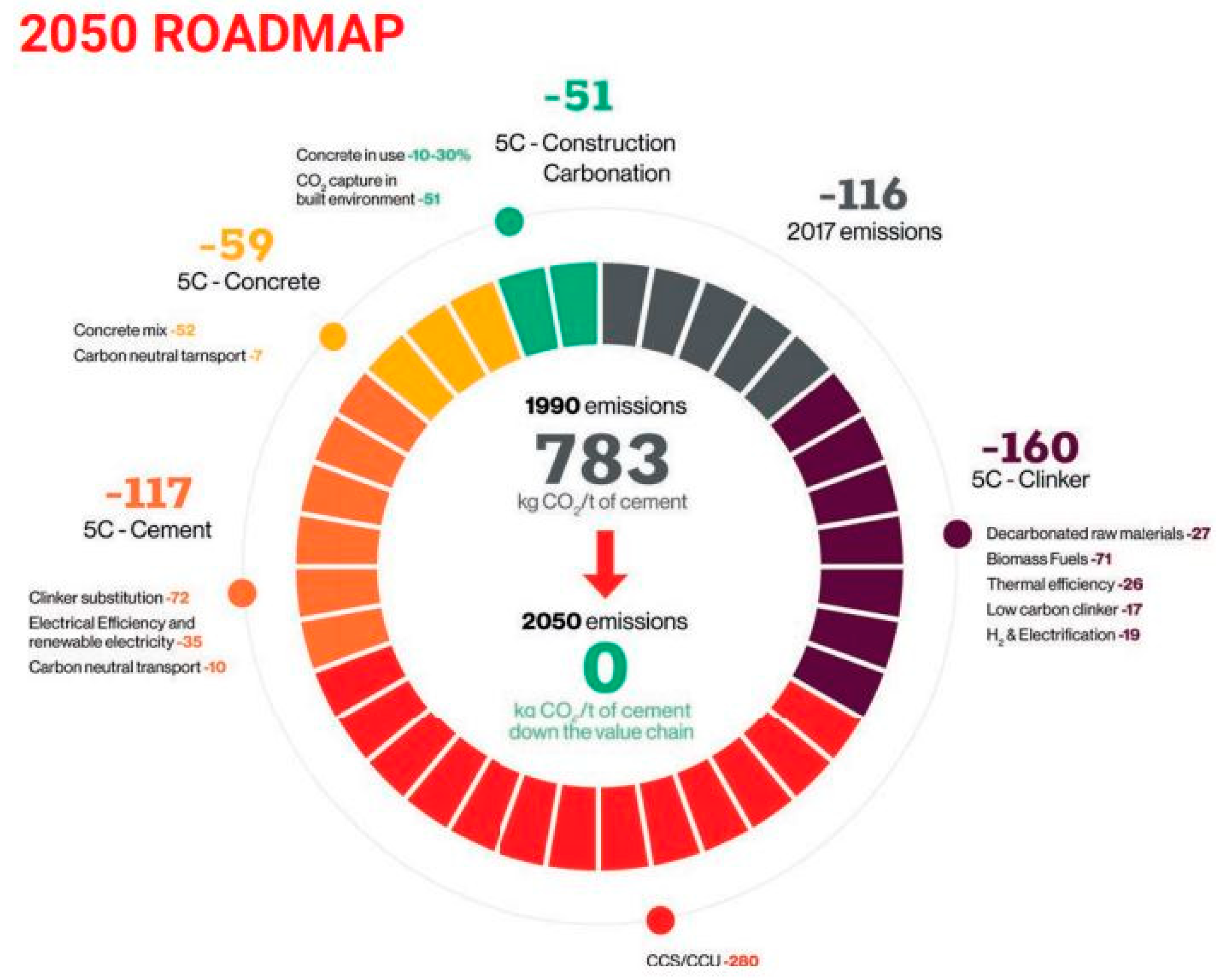

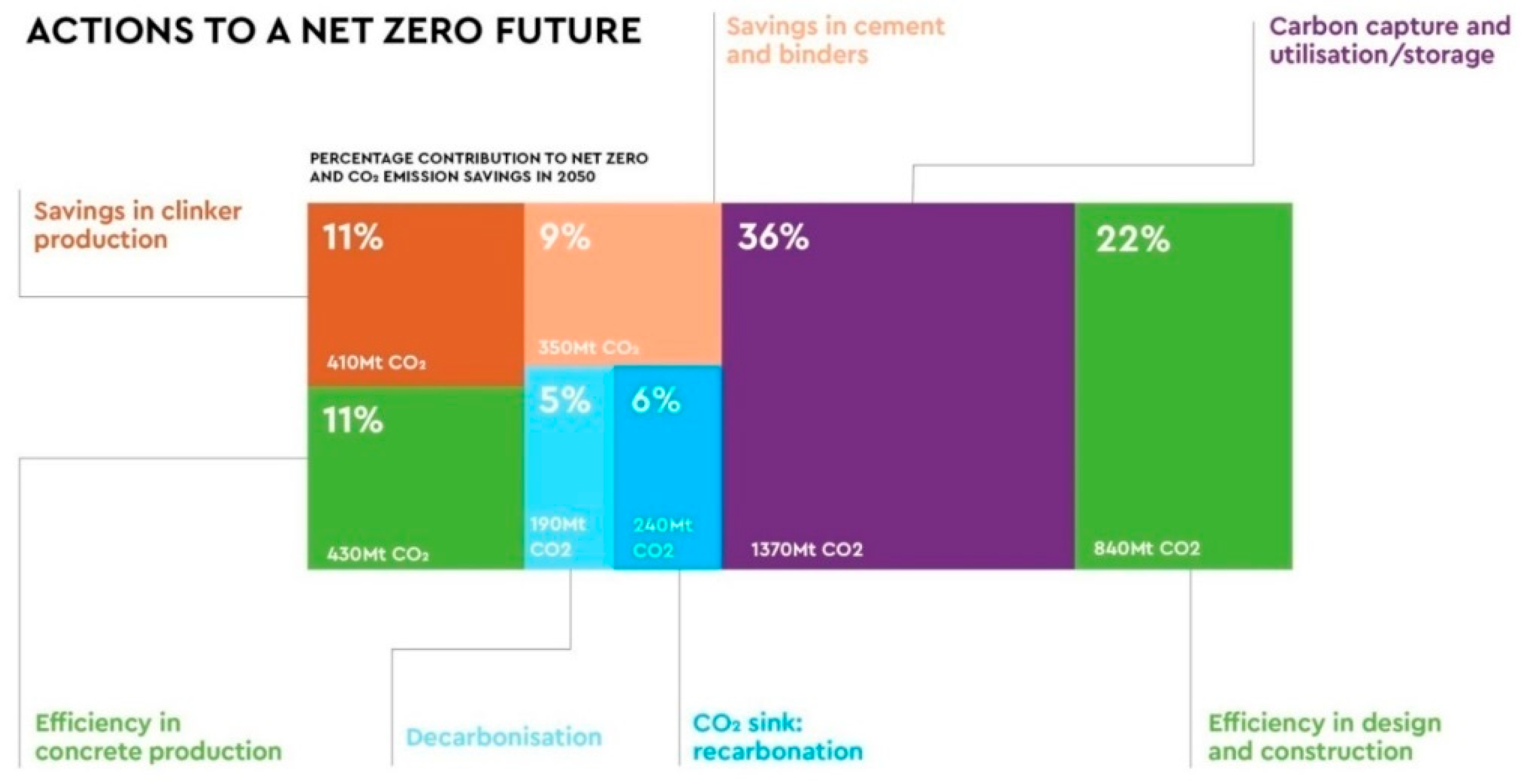

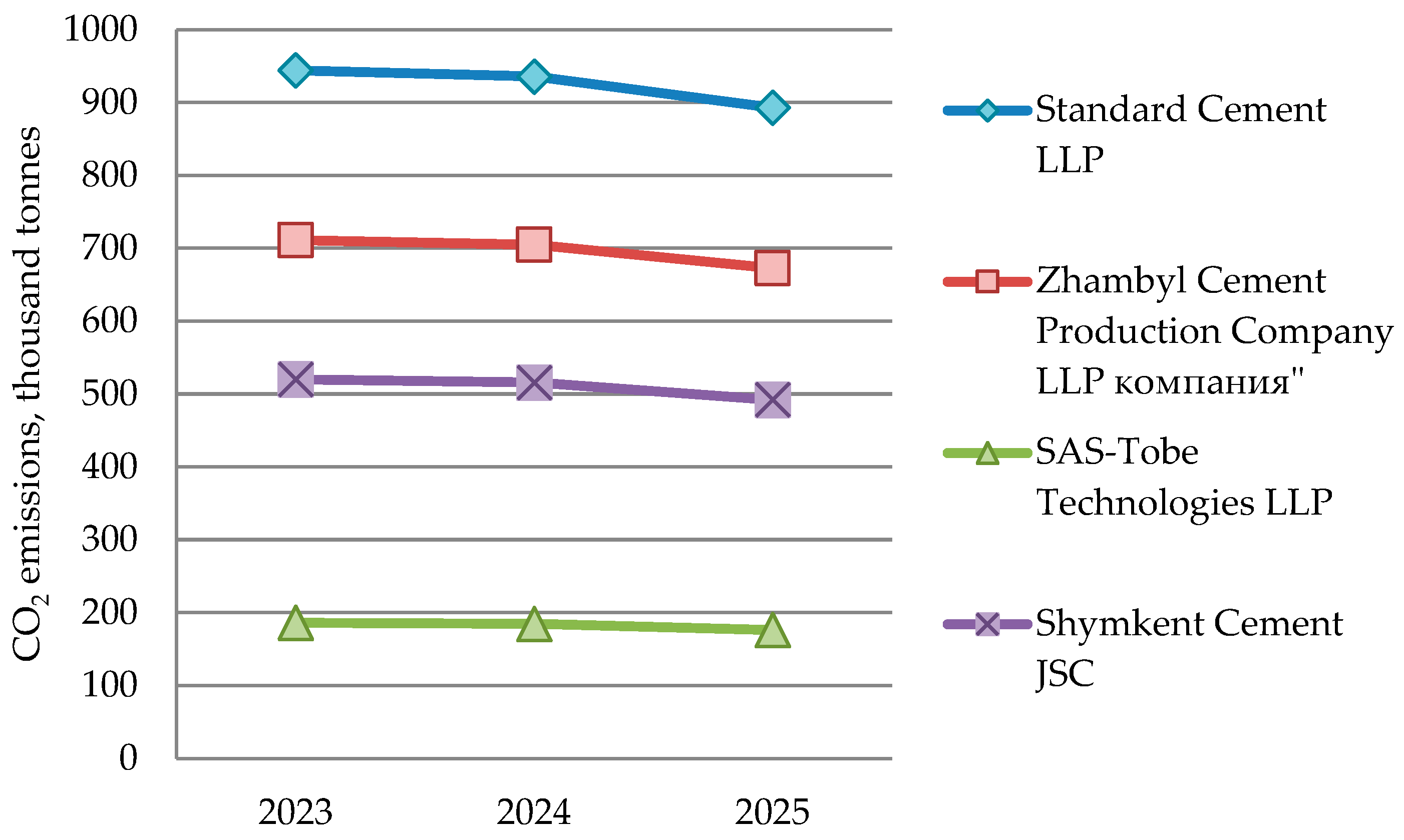

3.1.2. Approximate Calculation of Reduction of CO2 Emissions from Production of 1 Ton of Composite Cement with Addition of 15% Burnt Shale

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hegde S.B. Cement Industry Striving for Carbon Neutrality// Cement and its application. 2023. 1. Рр. 66-69. https://en.jcement.ru/magazine/598/56349/.

- GCCA Sustainability Guidelines for the monitoring and reporting of CO2 emissions from cement manufacturing. October 2019. – URL: https://gccassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/GCCA_ Guidelines_CO2Emissions_v04_AMEND.pdf.

- CEMBUREAU. 2020. Activity Report. N° Editeur: D / 2021 / 5457 / May. – URL: https://www.cembureau.eu/media/1sjf4sk4/cembureau-activity-report-2020.pdf.

- https://gccassociation.org/concretefuture/.

- https://gccassociation.org/concretefuture/getting-to-net-zero/.

- J.H.A. Rocha, R.D. Toledo Filho, N.G. Cayo-Chileno. Sustainable alternatives to CO2 reduction in the cement industry: A short review// Materialstoday: Proceedings. Volume 57, Part 2, 2022, Pages 436-439. [CrossRef]

- Bashmakov I.A., Potapova E.N., Borisov K.B., Lebedev O.V., Guseva T.V. Cement Sector Decarbonization and Development of Environmental and Energy Management Systems// Stroitelʹnye Materialy. 2023. № 9. Pp. 4-12.

- Potapova E.N., Guseva T.V., Tolstykh T.O., Bubnov A.G. Technological, technical, organizational and managerial solutions for the sustainable development and decarbonization of cement sector // Technique and technology of silicates. – 2023. Vol. 30, No2. – Pp. 104 – 115. https://tsilicates.com/2023_tts2.

- Lochana Poudyal, Kushal Adhikari. Environmental sustainability in cement industry: An integrated approach for green and economical cement production// Resources, Environ. Sustain. 2021. Volume 4, June 2021, 100024. [CrossRef]

- Environmental Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated 2 January 2021 No. 400-VI ZRC. Astana. 2020 (with amendments and additions as of 12.12.2024). [Ekologicheskii kodeks Respubliki Kazahstan] https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K2100000400.

- Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated 28 October 2021 No. 775 ‘On Approval of the Rules for Development, Application, Monitoring and Revision of Best Available Techniques Guides’. Astana. RK. 2021. [Ob utverjdenii Pravil razrabotki_ primeneniya_ monitoringa i peresmotra spravochnikov po nailuchshim dostupnim tehnikam] https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2100000775.

- On Approval of the Best Available Techniques Guide ‘Cement and Lime Production’ Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated 24 October 2023 No. 941. Astana. RK. 2021. [Proizvodstvo cementa i izvesti] https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2300000941.

- M. Fantini, M. Spinelli, F. Malli, M. Gatti, S. Consonni. CLEANKER project: CO2 capture in the cement industry // Cement and its applications, 2020. №2. - p.78-80. [Proekt CLEANKER_ ulavlivanie SO2 v cementnoi promishlennosti] https://jcement.ru/magazine/vypusk-2-2020/proekt-cleanker-ulavlivanie-co-v-tsementnoy-promyshlennosti/.

- Magistri M. The challenge of low clinker cements / M. Magistri, P. D'Arcangelo., D. Padovani // ibausil. – September 2023. https://cadd.mapei.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/The-challenge-of-low-clinker-cements-Ibausil-September-2023.pdf.

- Order of the Minister of Ecology, Geology and Natural Resources of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated 11 July 2022 No. 525 ‘On Approval of the National Carbon Plan’. [Ob utverjdenii nacionalnogo plana uglerodnih kvot] https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/V2200028798.

- Ozerova E.M., Kaigorodov O.N. Waste utilisation in the Russian cement industry // Cement and its application, 2020. №4. - p.33-35. [Ispolzovanie othodov v Rossiiskoi cementnoi promishlennosti] https://jcement.ru/magazine/vypusk-4-2020/ispolzovanie-otkhodov-v-rossiyskoy-tsementnoy-promyshlennosti/.

- M.I. Sanche de Rojas, A. Asencio, M. Frias, I. Cuevas, C. Medina Low clinker cements containing construction waste and scrap as pozzolanic additive // Cement and its application, 2020. №2. - p. 84-89. [Nizkoklinkernie cementi_ soderjaschie stroitelnie othodi i lom kak puccolanovuyu dobavku] https://jcement.ru/magazine/vypusk-2-2020/nizkoklinkernye-tsementy-soderzhashchie-stroitelnye-otkhody-i-lom-kak-putstsolanovuyu-dobavku/.

- Abramson I.G. Problems and prospects of the sustainable development of the basic building materials industry / I.G. Abramson // Cement and its application. - 2007. №6. - p.123-128. [Problemi i perspektivi ustoichivogo razvitiya industrii osnovnih stroitelnih materialov] https://jcement.ru/magazine/vypusk-6-239/problemy-i-perspektivy-ustoychivogo-razvitiya-industrii-osnovnykh-stroitelnykh-materialov/.

- Korchunov I., Dmitrieva E., Potapova E., Sivkov S., Morozov A. Frost Resistance of The Hardened Cement with Calcined Clays// Iranian Journal of Materials Science and Engineering. 2022. 19(4). Р. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Smolskaya E.A., Potapova E.N., Korshunov I.V., Sivkov S.P. Properties of geopolymer cement based on thermally activated clay// Cement and its application. 2024. No. 1. pp. 50-54. https://jcement.ru/magazine/vypusk-1-2024/svoystva-geopolimernogo-tsementa-na-osnove-termoaktivirovannykh-glin/ (circulation date: 23.05.2024). [CrossRef]

- Franco Zunino, Karen L. Scrivener. Going Below 50% Clinker Factor in Limestone Calcined Clay Cements (LC3): A Comparison with Pozzolanic Cements from the South American Market. Proceedings of the 75th RILEM Annual Week 2021. RILEM, vol. 40. 2023. Рр. 60-64. [CrossRef]

- Jørgen Skibsteda, Ruben Snellings. Reactivity of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) in cement blends. Cement and Concrete Research. Volume 124, October 2019, 105799. [CrossRef]

- Antunes M., Santos R.L., Pereira J., Rocha P., Horta R.B., Colaço R. Alternative Clinker Technologies for Reducing Carbon Emissions in Cement Industry: A Critical Review. Materials 2022, 15, 209. [CrossRef]

- Dikshit A.K., Gupta S., Chaturvedi S.K., Singh L.P. Usage of lime sludge waste from paper industry for production of Portland cement Clinker: Sustainable expansion of Indian cement industry. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering. 2024. 9, 100557. [CrossRef]

- Gapparov J., Syrlybekkyzy S., Filin A., Kolesnikov A., Zhatkanbayev Y. Overview of techniques and methods of processing the waste of stale clinkers of zinc production. MIAB Min. Informational Anal. Bull. 2024. 4. p 44–55 . [CrossRef]

- Zhanikulov N., Sapargaliyeva B., Agabekova A., Alfereva Y., Baidibekova A., Syrlybekkyzy S., Nurshakhanova L., Nurbayeva F., Sabyrbaeva G., Zhatkanbayev Y., Studies of Utilization of Technogenic Raw Materials in the Synthesis of Cement Clinker from It and Further Production of Portland Cement. June 2023. Journal of Composites Science 7 (6) : 226. [CrossRef]

- Guillermo Hernández-Carrillo, Alejandro Durán-Herrera, Arezki Tagnit-Hamou. Effect of Limestone and Quartz Fillers in UHPC with Calcined Clay. Materials 2022, 15 (21), 7711; [CrossRef]

- Ram K., Flegar M., Serdar M., Scrivener K. Influence of Low- to Medium-Kaolinite Clay on the Durability of Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3) Concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 374. [CrossRef]

- Potapova E.N., Manushina A.S., Zyryanov M.S., Urbanov A.V. Methods for determining the pozzolanic activity of mineral additives // Building materials, equipment, technologies of the XXI century. 2019. № 11-12 (250-251). p. 47-51. [Metodi opredeleniya puccolanovoi aktivnosti mineralnih dobavok] https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?edn=gytmng.

- Mechay A.A., Baranovskaya E.I., Popova M.V. Composite Portland cement with the use of mineral additives based on natural raw materials / Proceedings of BSTU, 2022, Series 2, No.2. - p.100-106. [Kompozicionnii portlandcement s ispolzovaniem mineralnih dobavok na osnove prirodnogo sirya] https://elib.belstu.by/bitstream/123456789/50310/1/13.%20%D0%9C%D0%B5%D1%87%D0%B0%D0%B9.pdf.

- Yakubzhanova and N.Dj. Makhsudova., M.I. Iskandarova, A.I. Buriev, G. B. Begzhanova, D.D. Mukhitdinov. Z.B. // Technological foundations for solving the problem of metallurgy and TPP waste utilization for the development of "green" technology for the production of composite cements //1V International Scientific ash conference Construction Mechanics & Water Resources Engineering CONMECHYDRO 2022. dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the birth and memory of professor Uktam Pardaevich Umurzakov. August 23-24, 2022, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Sub. 0191. (Scopus & Web of Science, Melville, AIP Publishing, New York 2023). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367538651_Technological_foundations_for_solving_problem_of_metallurgy_and_TPP_waste_utilization_for_development_of_Green_technology_for_composite_cements_production.

- Yuldashev F.T. Ecosystem improvement by utilisation of technogenic wastes, use of active mineral additive ‘phosphozol’ in cement production. Belgorod: Izd-vo BSTU. 2022. - 203 p. [Uluchshenie ekosistemi putem utilizacii tehnogennih othodov ispolzovanie aktivnoi mineralnoi dobavki «fosfozol» v proizvodstve cementov] https://api.scienceweb.uz/storage/publication_files/6563/17860/659ce53f3f895___%D0%9C%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%84%D0%B8%D1%8F%20%D0%A4%D0%9E%D0%A1%D0%A4%D0%9E%D0%97%D0%9E%D0%9B%20%D0%91%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4.pdf.

- Mukhiddinov D.D. Composite Portland cements with the use of hybrid additives / Proceedings of II-Resp. NPK ‘Innovative developments and prospects of development of chemical technology of silicate materials’. 2022. Tashkent. - p. 361-363. [Kompozicionnie portlandcementi s primeneniem gibridnih dobavok] https://api.scienceweb.uz/storage/publication_files/4727/18086/659f9cf004cd4___13.pdf.

- E.Y. Malova, V.K. Kozlova, V.I. Vereshchagin, Y.S. Sarkisov, N.P. Gorlenko, A.N. Pavlova. Geonics: from geochemistry of defernite, spurrite and their analogues to the creation of artificial materials based on cement systems // Polzunov Bulletin No. 1, 2017. p 78-83. [Geonika: ot geohimii defernita_ spurrita i ih analogov k sozdaniyu iskusstvennih materialov na osnove cementnih sistem] https://journal.altstu.ru/media/f/old2/pv2017_01/pdf/078malova.pdf.

- Атабаев Ф.Б., Фузайлoва Ф.Н., Турсунoва Г.Р., Ахмедoва Д.У. Эффективные шлакoкарбoнатные пoртландцементы. // Journal of new century innovations. Vol. 14 No. 4. 2022.https://newjournal.org/new/article/view/546.

- Kuandykovaм A.Ye., B.T. Taimasov, E.N. Potapova, B.K. Sarsenbayev, M.S. Dauletiyarov, N.N. Zhanikulov, B.B. Amiraliyev, A.A. Abdullin «Production of portland cement clinker based on industrial waste» // Journal of Composites Science 2024, 8, 257. [CrossRef]

- Kuandykova А.E., Taimasov B., Potapova E.N., Dauletyiarov M.C., Amiraliyev B.B. INVESTIGATION OF CHEMICAL AND MINERALOGICAL COMPOSITION AND TECHNOLOGICAL PROPERTIES OF INDUSTRIAL WASTE FOR CEMENT PRODUCTION /Proceeding Χ International Conference Industrial Technologies and Engineering ICITE – 2023. Volume 1. P.180-184. https://istina.ipmnet.ru/publications/article/684609465/.

- A. Kuandykova, B. Taimasov, N. Zhanikulov, E. Potapova. Application of clinker from Aschisai metallurgical plant for synthesis of belite clinker. Series // Izvestiya ROO ‘NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN’. Series CHEMISTRY AND TECHNOLOGY 1 (458) January - march 2024.Almaty, NASRK -p.70-83. [Belittі klinker sintezdeu үshіn aschіsai metallurgiyali zauitiniң klinkerіn қoldanu] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379366985_NEW_STRATEGY_FOR_THE_SYNTHESIS_OF_35-DIARYLPYRAZOLES_BASED_ON_CHALCONES.

- Andrzej M.В. Cement–based composites. Materials, mechanical properties and performance / M.В. Andrzej. – 2009. – 526 p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268442900_Cement-Based_Composites_Materials_Mechanical_Properties_and_Performance.

- Mansour M. Metakaolin as a pozzolan for high performance mortar / M. Mansour, M. Abadla, R. Jauberthi, I. Messaoudene // Cement, Wapno, Beton. – 2012. – №2. – P. 102–108.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279699584_Metakaolin_as_a_pozzolan_for_high-performance_mortar.

- Cherkasov V.D. Structure formation of cement composites with the addition of modified diatomite / V.D. Cherkasov, V.I. Buzulukov, A.I. Emelyanov // Construction Materials. - 2015. - №11. - p. 75-77. [Strukturoobrazovanie cementnih kompozitov s dobavkoi modificirovannogo diatomita] https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/strukturoobrazovanie-tsementnyh-kompozitov-s-dobavkoy-modifitsirovannogo-diatomita.

- Cherkasov V.D. Active mineral additive on the basis of chemically modified diatomite / V.D. Cherkasov, V.I. Buzulukov, A.I. Emelyanov, E.V. Kiselev, D.V. Cherkasov // Izvestiya Vuzov. Construction. - 2011. - №12. - p. 50-55. [Aktivnaya mineralnaya dobavka na osnove himicheski modificirovannogo diatomita] https://bik.sfu-kras.ru/elib/view?id=PRSV-/%D0%90%2043-721410.

- Konan K.L. Comparison of surface properties between kaolin and metakaolin concentrated lime solutions / K.L. Konan, C. Peyratout, A. Smith, J.P. Bonnet, et. al. // Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. – 2009. – Vol. 339, №1. – P. 103–109.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19682702/.

- Klyuchkov N.В. High-resolution X-ray diffractometry and reflectometry: guidelines for laboratory works on materials diagnostics / N. V. Klyuchkov. - Saint-Petersburg: CCP ‘Materials science and diagnostics in advanced technologies’ at A. F. Ioffe Federal Institute of Physics and Technology, 2010. - 18 p. [Visokorazreschayuschaya rentgenovskaya difraktometriya i reflektometriya: metodicheskie ukazaniya k laboratornim rabotam po diagnostike materialov] http://www.school.ioffe.ru/phys/files/HRXRD_XRR_v.n1.0.pdf.

- Bolotskikh O.N. European methods of physical and mechanical testing of cement / O.N. Bolotskikh. N. European methods of physical and mechanical testing of cement / O. N. Bolotskikh. - KHNAGH, 2012. - 60 p. [Evropeiskie metodi fiziko_mehanicheskih ispitanii cementa] https://www.chitalkino.ru/bolotskikh-o-n/evropeyskie-metody-fiziko-mekhanicheskikh-ispytaniy-tsementa/.

- Sagitova G., Ainabekov N., Daurenbek N., Assylbekova D., Sadyrbayeva A., Bitemirova A., Takibayeva G. (2024). Modified Bitumen Materials from Kazakhstani Oilfield. Advances in Polymer Technology. 2024. 1-10. 10.1155 / 2024 / 8078021. [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko V.P., Golubev V.G., Zhantasov M.K., Sadyrbayeva A.S., Nadirova Z.H.K., Ainabekov N.B. (2017). Investigation of anti-corrosion properties of environmentally safe additives to drilling solutions based on tar of cotton oil. Chimica Oggi / Chemistry Today. 35. 32-36. https://www.teknoscienze.com/tks_article/investigation-of-anti-corrosion-properties-of-environmentally-safe-additives/.

- *GOST 25094-2015 Active mineral additives for cements. Method for determination of activity. Standard Inform Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2016.

- **GOST 5382-2019 Cements and cement production materials. Methods of chemical analysis. Standard Inform Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2019.

- ***GOST 310.1-76 and 310.3-76 Cements. Test methods. IPK Publishing House of Standards: Moscow, Russia, 2016.

- ****GOST 12730.1-2020 Concretes. Methods of density determination. Standard Inform Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2021.

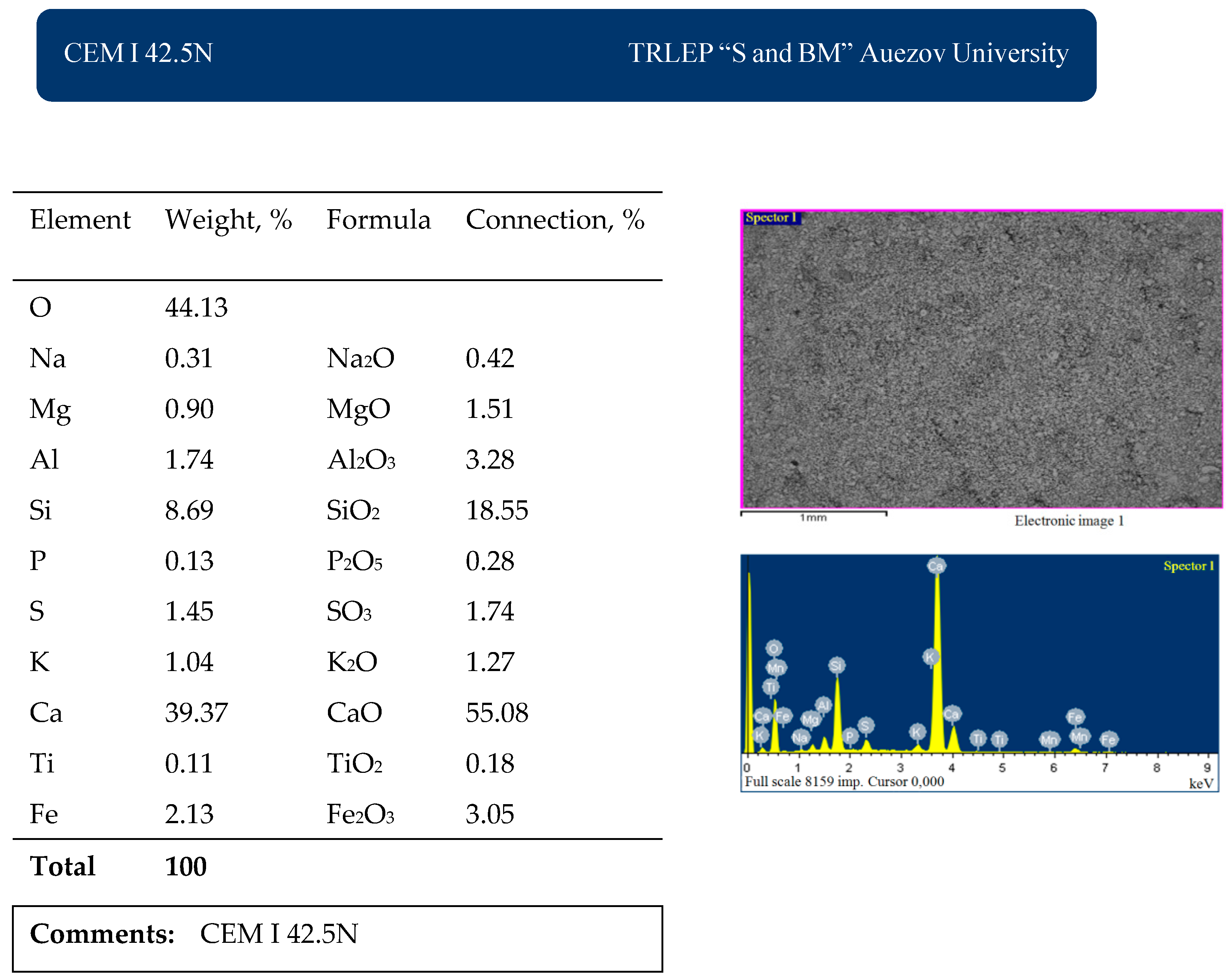

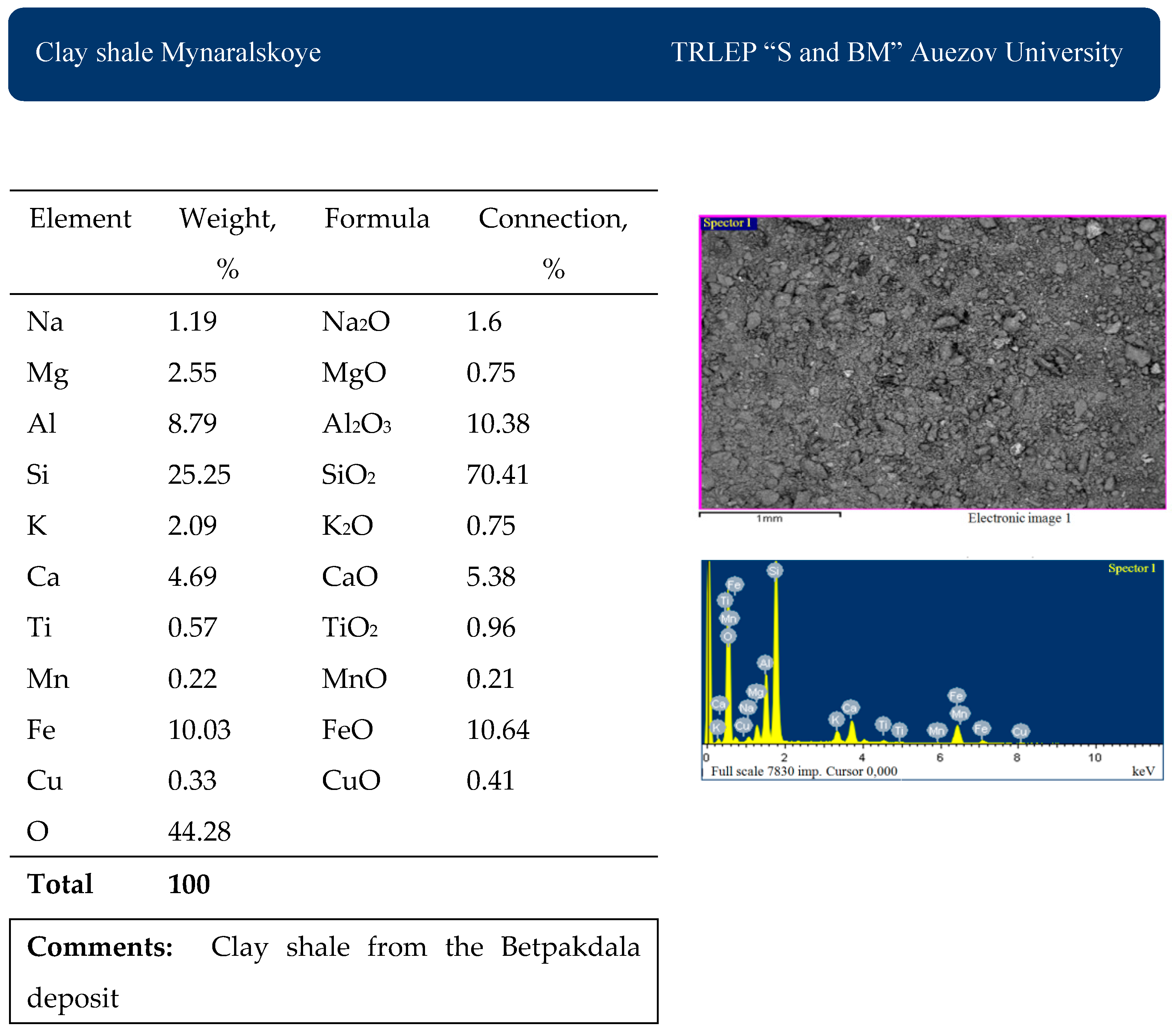

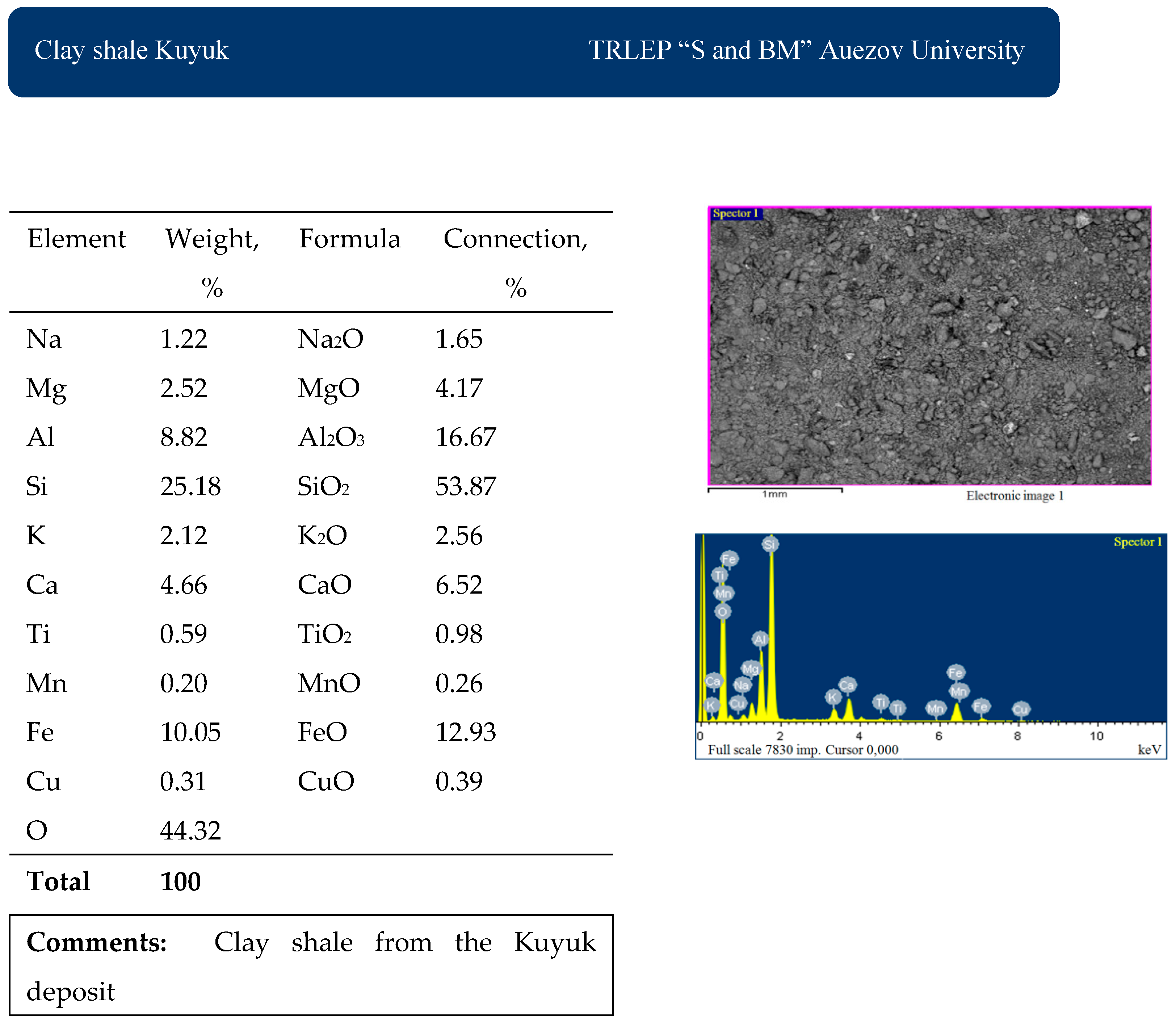

| Name | Chemical composition, % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Fe2O3 (FеO) | Na2O | K2O | MgO | |

| CEM I 42.5N | 18.55 | 3.28 | 55.08 | 3.05 | 0.42 | 1.27 | 1.51 |

| Mynaral clay shale SM | 70.41 | 10.38 | 5.38 | 10.64 | 1.6 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Kuyuk clay shale SK | 53.86 | 16.66 | 6.53 | 12.94 | 1.64 | 2.55 | 4.16 |

| Shale additives, % | WC | Setting time, h-min |

Compressive strength, MPa |

Average density g/cm3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| start | end | 3 days | 7 days | 28 days | |||

| 0 | 27.0 | 2-40 | 4-10 | 32 | 35 | 48 | 2250 |

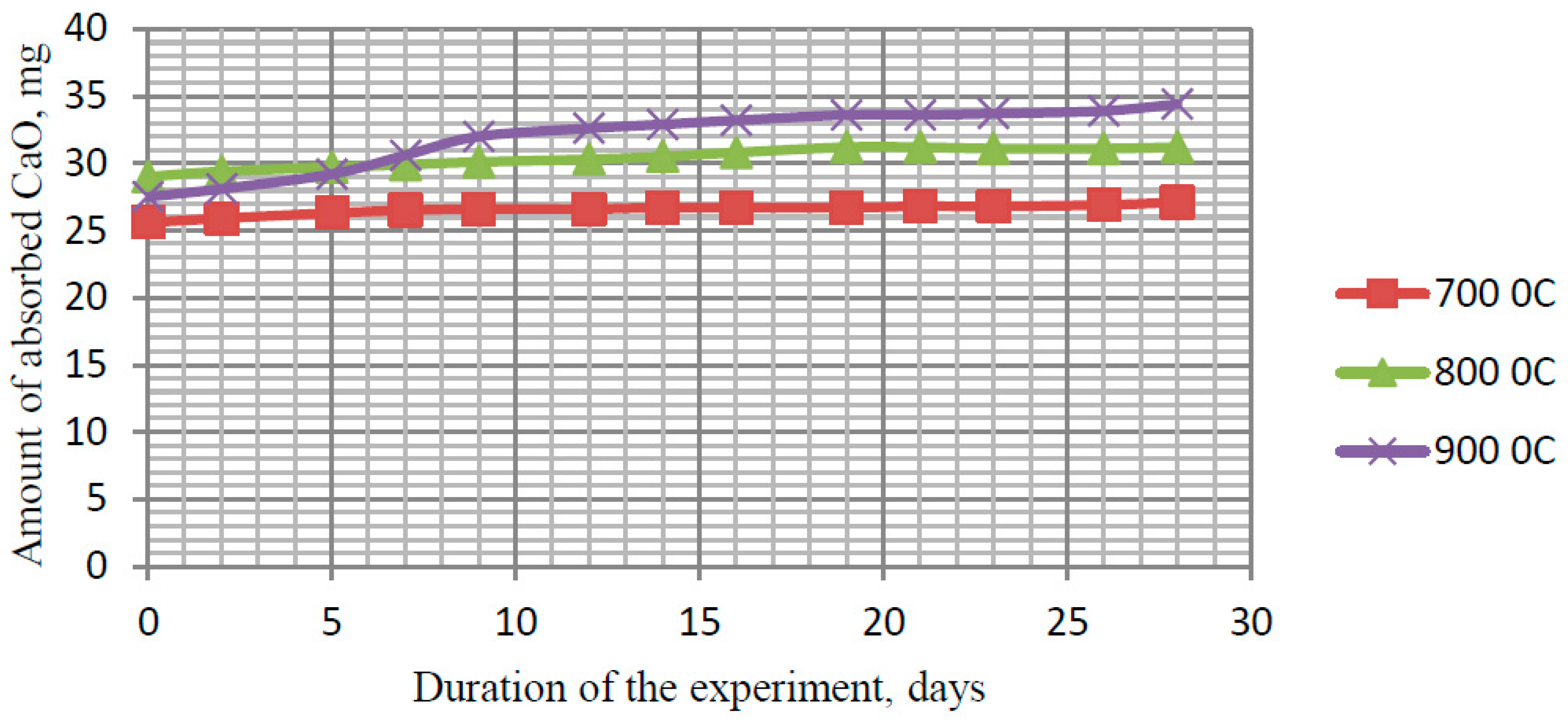

| 700 0С | |||||||

| 5 | 27.0 | 2-50 | 4-20 | 33 | 36 | 48 | 2245 |

| 10 | 27.0 | 2-55 | 4-30 | 33 | 38 | 49 | 2250 |

| 15 | 27.0 | 3-10 | 4-45 | 33 | 36 | 50 | 2265 |

| 800 0С | |||||||

| 5 | 27.0 | 2-40 | 4-15 | 33 | 37 | 49 | 2260 |

| 10 | 27.0 | 2-50 | 4-30 | 33 | 40 | 50 | 2270 |

| 15 | 28.0 | 3-10 | 4-50 | 34 | 38 | 50 | 2275 |

| 900 0С | |||||||

| 5 | 27.0 | 2-50 | 4-25 | 33 | 38 | 49 | 2260 |

| 10 | 27.0 | 2-55 | 4-50 | 33 | 39 | 50 | 2275 |

| 15 | 28.0 | 3-15 | 4-55 | 34 | 36 | 51 | 2290 |

| Shale additives, % | WC | Setting time, h-min |

Compressive strength, MPa |

Average density g/cm3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| start | end | 3 days | 7 days | 28 days | |||

| 0 | 27.0 | 2-40 | 4-10 | 32 | 35 | 48 | 2250 |

| 700 0С | |||||||

| 5 | 27.0 | 2-55 | 4-25 | 31 | 34 | 45 | 2235 |

| 10 | 27.0 | 3-05 | 4-45 | 30 | 33 | 46 | 2242 |

| 15 | 27.0 | 3-15 | 4-55 | 30 | 32 | 47 | 2145 |

| 800 0С | |||||||

| 5 | 27.0 | 2-50 | 4-20 | 32 | 34 | 46 | 2240 |

| 10 | 27.0 | 3-00 | 4-40 | 31 | 34 | 47 | 2245 |

| 15 | 28.0 | 3-10 | 4-50 | 30 | 33 | 48 | 2160 |

| 900 0С | |||||||

| 5 | 27.0 | 2-55 | 4-25 | 32 | 34 | 47 | 2240 |

| 10 | 27.0 | 3-05 | 4-45 | 32 | 34 | 48 | 2245 |

| 15 | 28.0 | 3-10 | 4-50 | 31 | 34 | 49 | 2250 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).