1. Introduction

The rapid industrialization in China from the mid-20th century to the present has generated substantial industrial solid wastes, primarily comprising ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) from steel plants and fly ash (FA) from thermal power plants. Recent statistics reveal an annual production of approximately 3.7 billion tons of industrial solid waste, with a comprehensive utilization rate of merely 55% and accumulated stockpiles exceeding 60 billion tons [

1]. Conventional disposal methods such as landfilling and roadbed backfilling not only result in resource wastage and economic burdens for enterprises but also pose significant environmental risks. Most industrial solid wastes, predominantly composed of Si, O, and Al elements, exhibit potential hydration activity or geopolymerization capabilities under aqueous conditions. These materials can serve as cementitious alternatives to traditional Portland cement without requiring energy-intensive

“two-step grinding and one-step calcination

” processes [

2], presenting crucial implications for achieving carbon neutrality and sustainable development.

Extensive research has been conducted on alkali-activated binders (AABs) in recent years. Xie et al. [

3] systematically investigated red mud-fly ash binary geopolymer materials using sodium silicate and NaOH as activators, revealing optimal workability, stability, and compressive strength at an activator modulus of 3.0. Liu et al. [

4] developed a ternary geopolymer system (FA:slag:carbide slag = 32:15:3) achieving 77.83 MPa compressive strength at 28 days through optimized parameters (solid-liquid ratio 0.55, activator modulus 1.2), with microstructural characterization via MIP and SEM. Cai et al. [

5] compared the durability of ultra-high strength alkali-activated concrete (AAB-UHSC) with conventional counterparts, demonstrating superior chloride resistance but relatively weaker carbonation resistance compared to OPC-UHSC, while noting sixfold enhanced carbonation resistance versus AAB-NSC. Xia et al. [

6] formulated high-performance AABs (>70 MPa) using desert sand and high-calcium FA, identifying optimal parameters (alkali content 5-8%, sodium silicate modulus 1.0-1.5) and attributing strength development to C(N)-A-S-H gel formation.

Current research predominantly employs strong alkaline solutions (NaOH/sodium silicate) as activators, which present limitations for road engineering applications requiring

“dry-mix transportation and on-site mixing.

” Moreover, these chemical activators incur high costs. Recent investigations have explored alkaline solid wastes as alternative activators, including carbide slag [

7,

8,

9,

10] and red mud [

11,

12,

13,

14]. In Qinghai Province, substantial quantities of soda residue (SR, pH>13) from sodium carbonate production (

Figure 1a) and carbide slag (CS, Ca(OH)₂-dominated, pH>13,

Figure 1b) from acetylene manufacturing accumulate, creating significant environmental and economic pressures.

This study innovatively develops a multi-component solid waste-based activator system using GGBS and FA as precursors, supplemented with SR (alkaline activator) and desulfurization gypsum (sulfate activator). We systematically investigate the synergistic effects of various activator combinations on the mechanical properties of the GGBS-FA binary system. Advanced characterization techniques including XRD, SEM-EDS, FTIR, and TG-DSC are employed to elucidate the activation mechanisms and hydration products formation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

The chemical compositions of raw materials are presented in

Table 1. The desulfurization gypsum (Gypsum) and ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) were supplied by Lanxin Iron & Steel Co., Ltd., while fly ash (FA) was obtained from Lanzhou Hongyuan Building Materials Co., Ltd. Carbide slag (CS) and soda residue (SR) were provided by Qinghai Salt Lake Magnesium Industry Co., Ltd. The SR was initially in a wet state (

Figure 2a) with 65% moisture content, exhibiting a milky-white appearance. After natural drying (

Figure 2b), the pH value measured 11 using ion-selective electrode method. All other materials (CS, Gypsum, GGBS, and FA) were supplied in dry form. The GGBS demonstrates a density of 2.9 g/cm³ and specific surface area of 424 m²/g, with 17.5% residue on 45 μm sieve for FA.

The basicity coefficient (M₀) and quality coefficient (K) of GGBS were calculated using Equations (1) and (2), yielding values of 0.86 and 1.87, respectively. This confirms the alkaline nature of the slag, complying with Chinese National Standard GB/T 18409-2017 for cementitious applications. The activity indices were determined as 70.2% at 7 days and 96% at 28 days, classifying it as S95-grade slag with high reactivity.

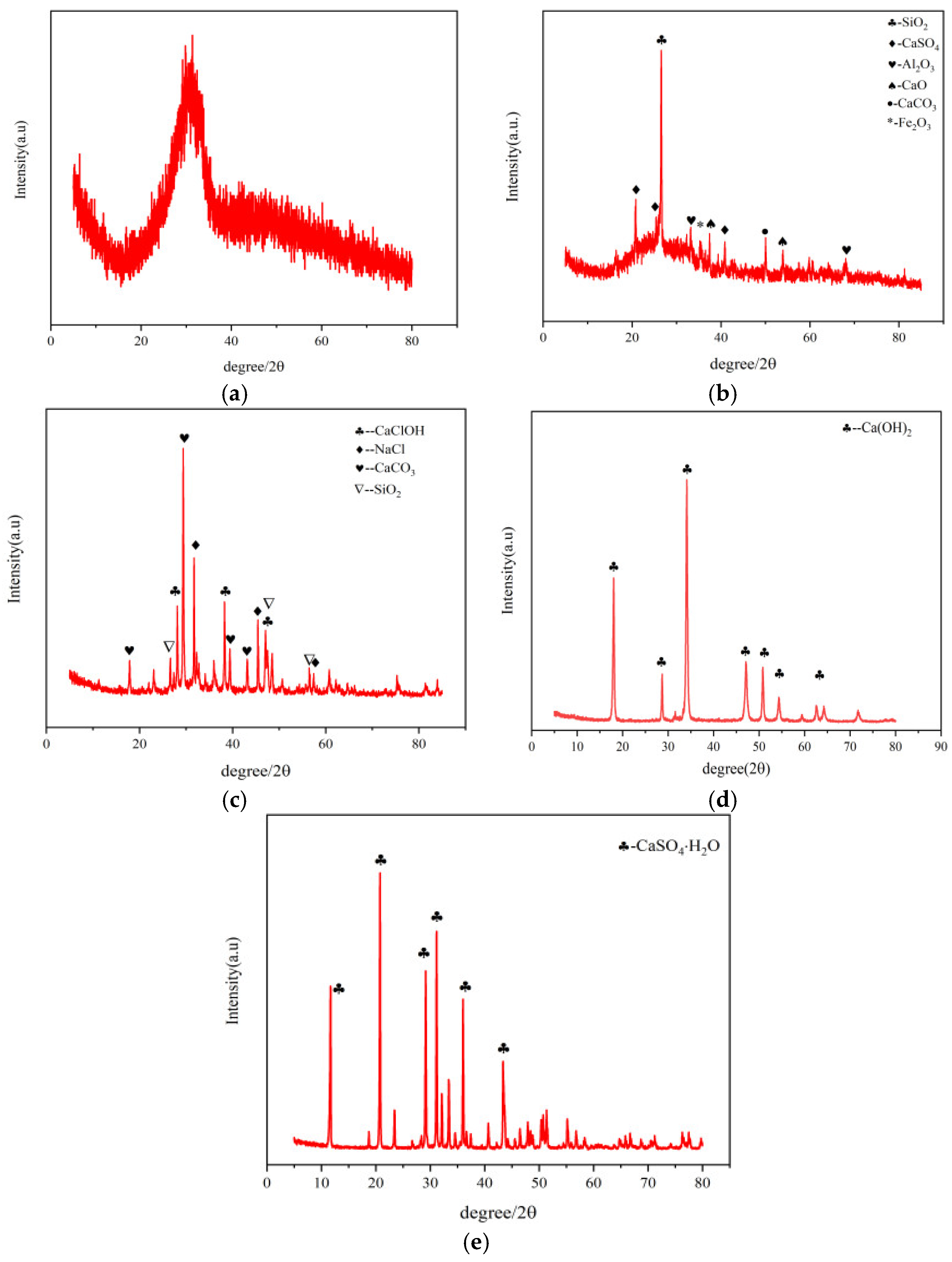

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (

Figure 3) revealed distinct phase characteristics:

GGBS (

Figure 3a) displayed a broad hump between 20-40° 2θ, indicating predominant amorphous glass phases with high reactivity.

FA (

Figure 3b) contained crystalline SiO

2 and Al

2O

3 with secondary phases of CaSO

4, CaCO

3, and CaO, accompanied by reactive glassy phases.

SR (

Figure 3c) primarily consisted of CaCO

3, NaCl, and CaClOH phases formed through complex precipitation processes involving Ca

2+, Cl

-, CO

32-, and Na

+ ions.

CS showed dominant Ca(OH)2 phase (91.66% CaO content).

Gypsum was identified as dihydrate calcium sulfate (CaSO4·2H2O)

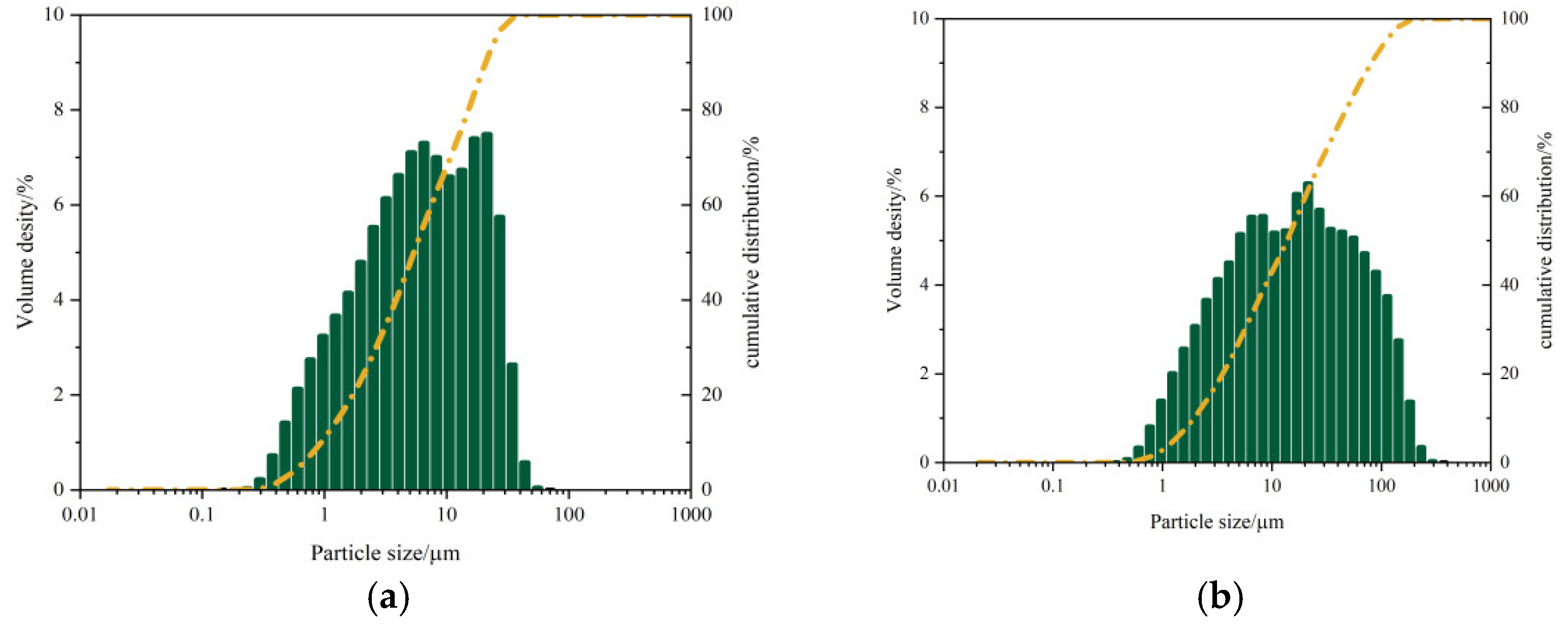

Particle size distribution analysis using a Shimadzu SALD-2300 laser particle size analyzer (

Figure 4) demonstrated:

GGBS: median diameter (D50) = 5.40 μm, mean diameter = 4.91 μm, mode diameter = 19.02 μm, SD = 0.49.

FA: D₅₀ = 13.74 μm, mean diameter = 12.89 μm, mode diameter = 19.02 μm, SD = 0.59.

2.2. Mix Proportion Design

revious studies have established optimal dosage ranges of 4-13 wt% for carbide slag (CS) and 15-30 wt% for soda residue (SR) as activators. This investigation develops a compound activator system (SR:CS = 3:7 by mass ratio) through three-phase experimental design:

1).Phase I - Activator optimization:

2).Phase II - Binary precursor system:

3).Phase III - Sulfate activation:

2.3. Specimen Preparation

1).Precisely weigh constituents according to

Table 2 proportions.

2).Sequentially add materials to pre-wetted mortar mixer:

Initial low-speed mixing (140±5 rpm): 30s binder-water blending.

Standard sand incorporation during second 30s low-speed mixing.

High-speed mixing (285±10 rpm): 30s + 60s after 90s rest period.

3).Cast 40×40×160 mm prism specimens using two-layer placement.

4).Compact each layer with 60 vibrations on standard jolting table.

5).Cure under controlled conditions (20±2°C, 95% RH) for 24h prior to demolding.

2.4. Testing Protocols

Strength development: Measure 3/7/28-day compressive strength per GB/T 17671 (ISO 679)

Phase analysis: Rigaku D/max-A XRD (Cu-Kα, 40kV/40mA, 5-85° 2θ, 2°/min).

Thermal analysis: Shimadzu DTG-60AH (N₂, 50mL/min, 10°C/min to 900°C).

Molecular characterization: Nicolet iS5 FTIR (400-4000 cm⁻¹, KBr pellet).

Microstructural observation: ZEISS Sigma300 SEM (90s Au-sputtered samples).

3. Results

3.1. The Influence of Multi-Source Solid Waste Activation on the Standard Consistency Water Demand and Setting Time of the GGBS-FA System

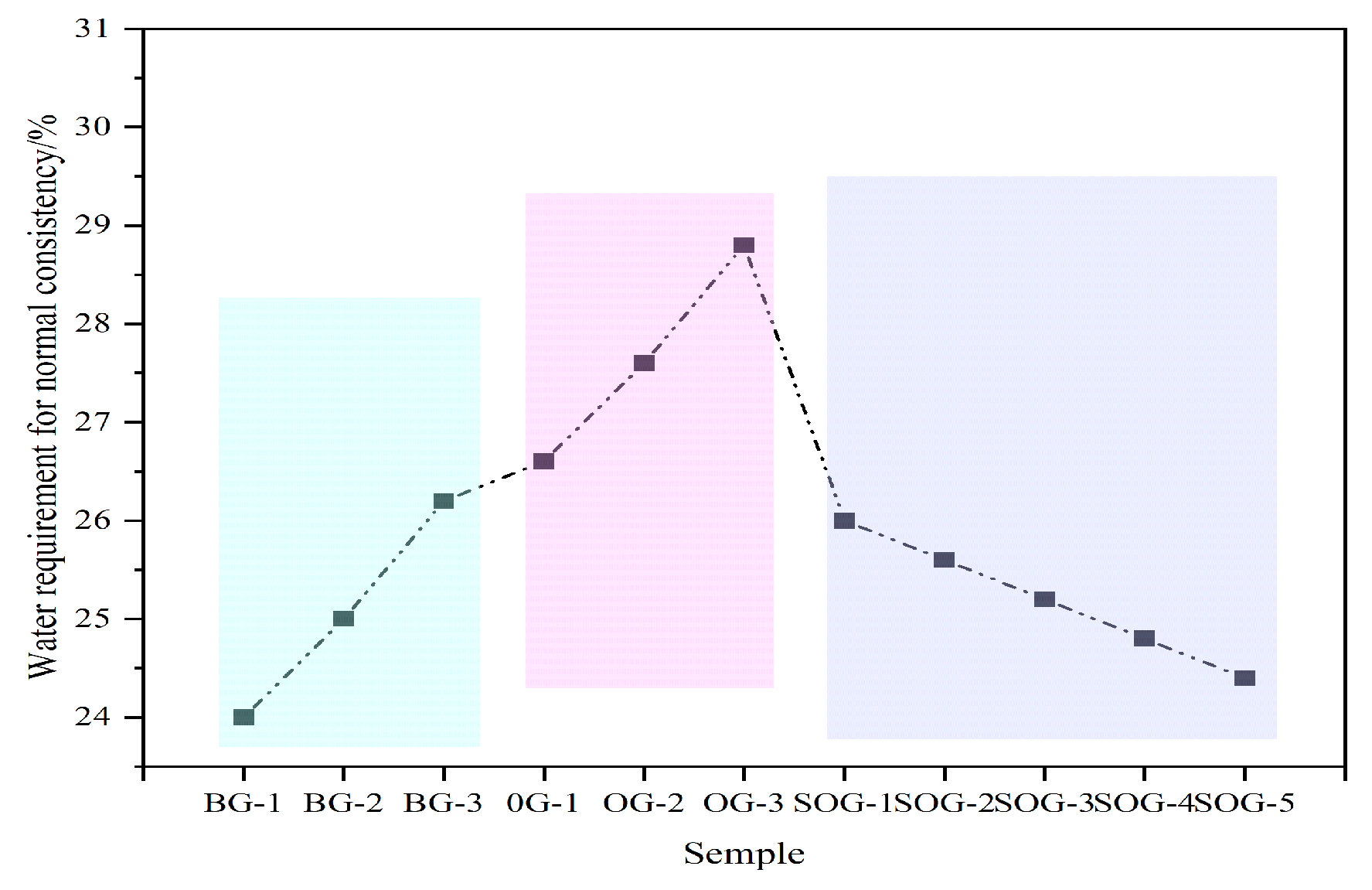

Figure 5 illustrates the influence of multi-source solid waste activation on the standard consistency water demand of cementitious material systems. In the BG system, as the CS content increases, the standard consistency water demand of the paste rises from 24% to 26.2%. This occurs because CS primarily consists of highly polar and low-solubility Ca(OH)₂, whose loose and porous microstructure results in a large specific surface area. Compared to SR, CS requires more water to wet particle surfaces and fill pores.In the OG system, with increasing FA substitution for GGBS, the standard consistency water demand of the paste increases from 26.2% to 28.8%. This is mainly attributed to FA’s porous or hollow particle morphology and higher specific surface area, which demand additional water for surface wetting and pore filling. In contrast, GGBS effectively combines free water and optimizes paste fluidity through its dense particle structure.In the SOG system, as gypsum replaces GGBS, the standard consistency water demand decreases from 28.8% to 24.4%. This reduction stems from gypsum’s composition dominated by soluble calcium sulfate, whose dense particle morphology and ion dissolution release effectively reduce paste viscosity while diminishing free water requirements.

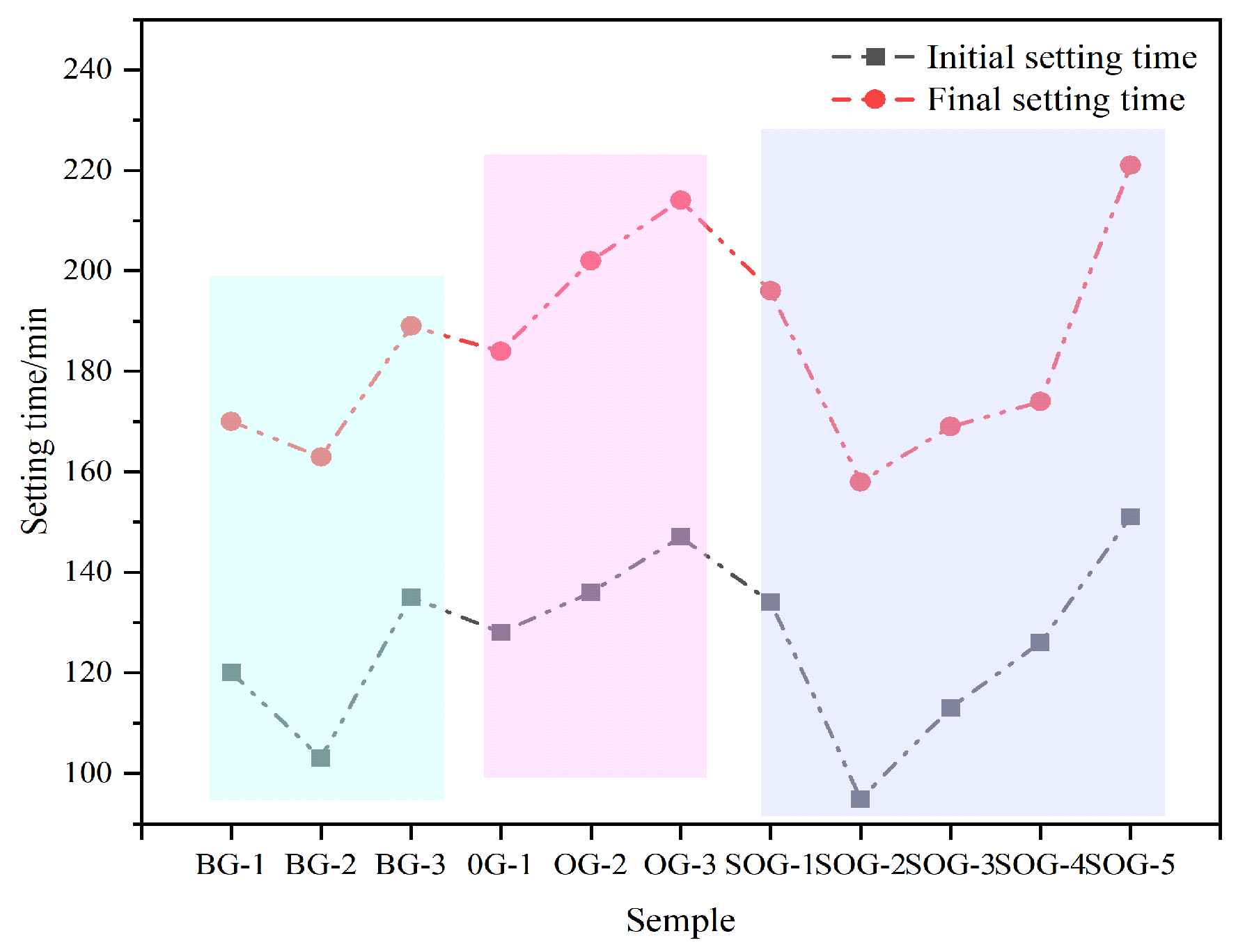

Figure 6 illustrates the influence of multi-source solid waste activation on the setting time of cementitious material systems. In the BG system, the initial setting time of the paste first decreases and then increases, with BG-2 exhibiting the shortest initial setting time of 103 min. This is attributed to the optimal activation ratio achieved between CS and SR in the paste, which promotes hydration. In the OG system, as the FA substitution for GGBS increases, the setting time gradually lengthens, with OG-3 showing the longest initial setting time of 147 min. This occurs because the hydration activity of FA is significantly lower than that of GGBS, slowing the hydration progress and prolonging the setting time.In the SOG system, the setting time first decreases and then increases with the substitution of gypsum for GGBS. At low substitution levels, gypsum provides a “sulfate activation” effect, accelerating hydration and shortening the setting time. However, as the substitution amount increases, excessive gypsum fails to participate in hydration reactions during the early stages, leading to an extended setting time.

3.2. Effects of Multi-source Solid Waste Activation on Mechanical Properties of Slag-Fly Ash System

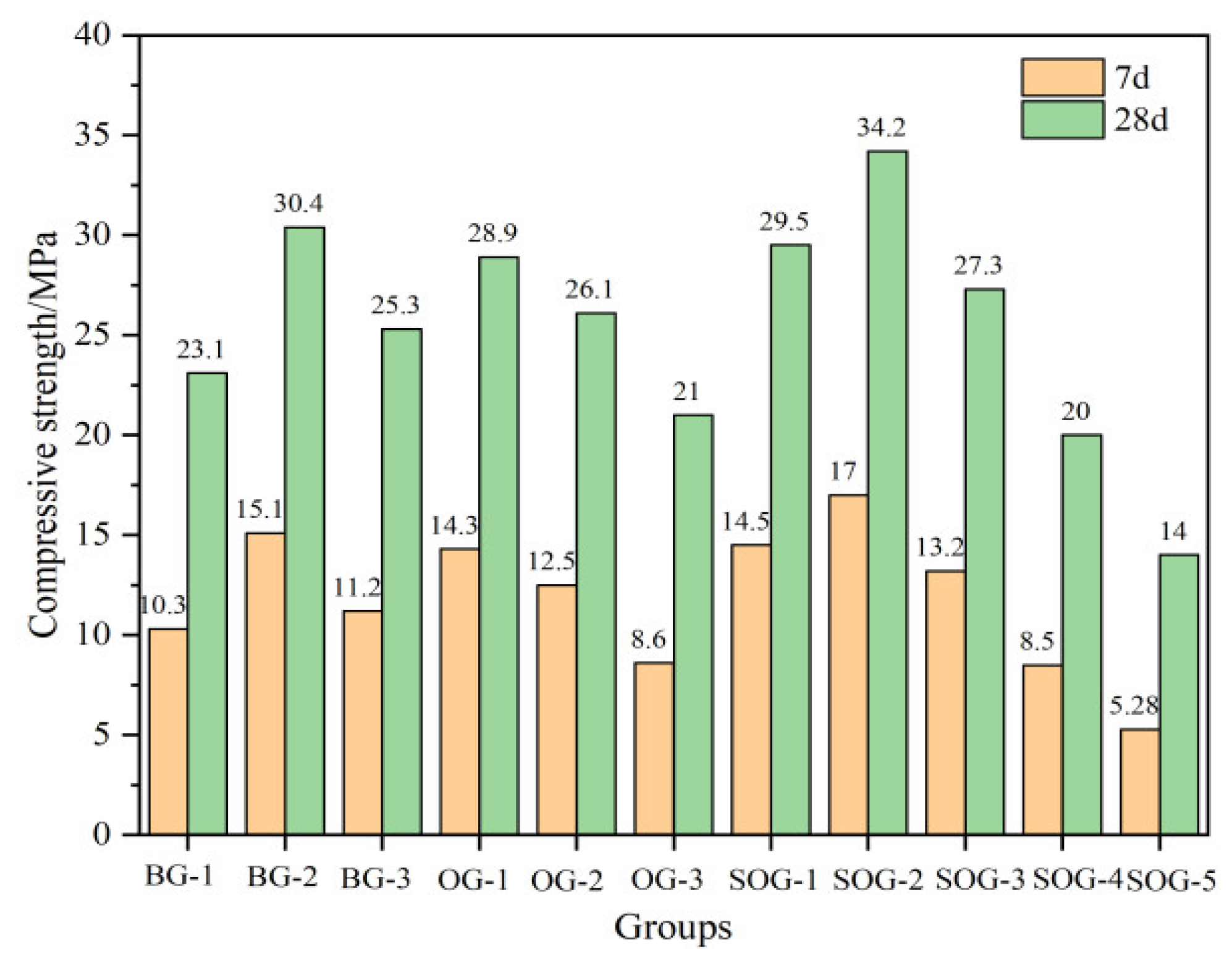

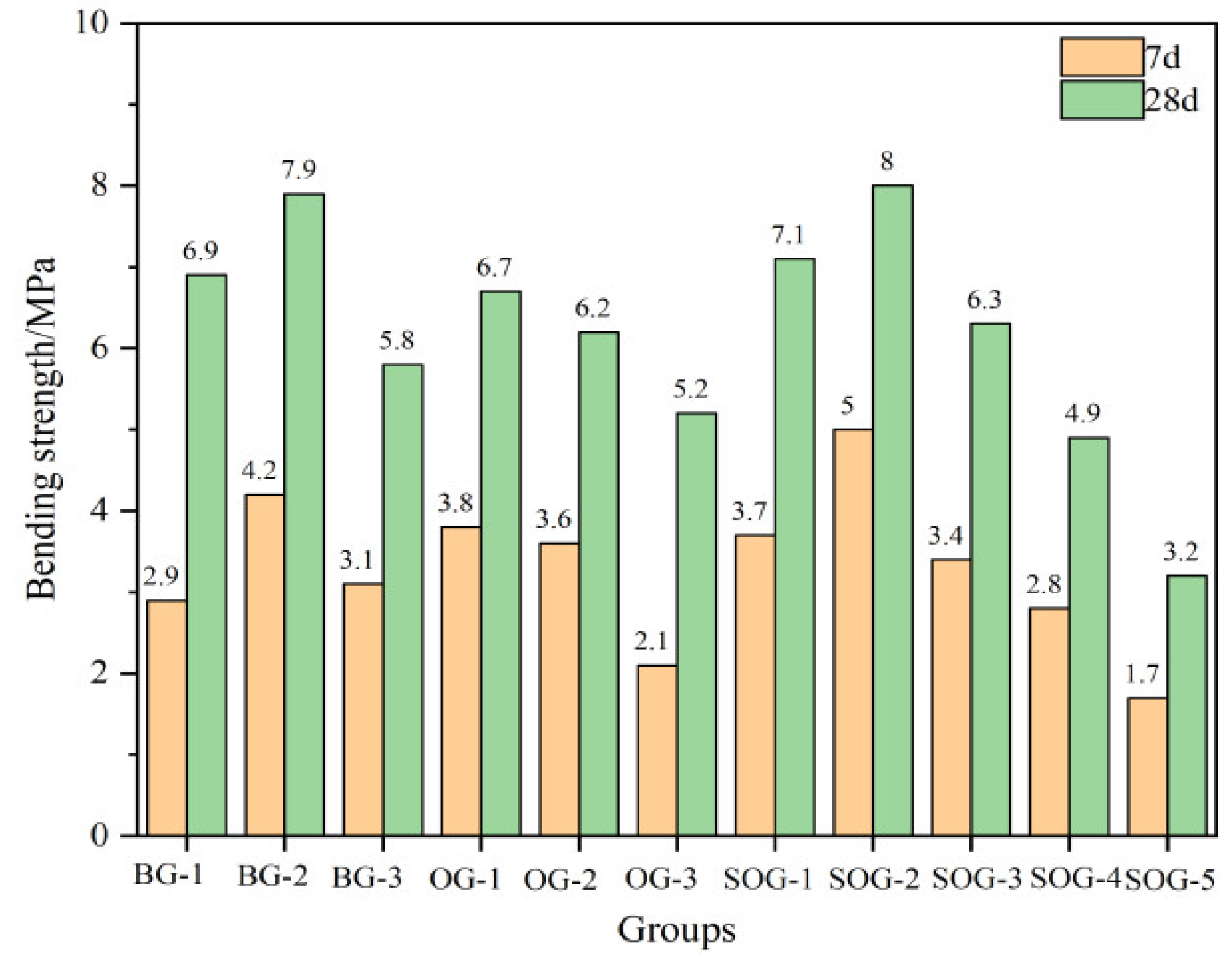

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the 7-day and 28-day compressive and flexural strengths of cement mortar under different mix proportions. The strength test results demonstrate that when the total content of alkali residue and carbide slag reaches 30%wt, their activation effect on slag becomes feasible. As carbide slag replaces alkali residue in 4%wt increments, the mortar strength initially increases then decreases. The optimal alkali residue content is 22%wt with 8%wt carbide slag, achieving a 28-day compressive strength of 30.4 MPa. This occurs because the alkaline environment created by alkali residue and carbide slag facilitates the “depolymerization” reaction of slag, promoting the formation of C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels during hydration, thereby enhancing strength development [

15]. Increased carbide slag content introduces substantial Ca²⁺ and OH⁻ ions, establishing a strong alkaline environment and supplementing calcium ions to accelerate nucleation of C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels. Simultaneously, the supplemented Ca²⁺ promotes the formation of ettringite (AFt) from aluminosilicate phases in slag [

16]. However, when carbide slag content increases from 8%wt to 12%wt, the 28-day mortar strength decreases from 30.4 MPa to 25.3 MPa due to Ca(OH)₂ solution saturation and subsequent crystal formation that impedes strength development [

17].

Under optimal alkali residue and carbide slag proportions, when fly ash replaces slag in 10%wt increments, both 7-day and 28-day strengths progressively decrease. At 30%wt fly ash content, 7-day compressive strength decreases by 43% and 28-day strength by 30.9%. This reduction occurs because fly ash exhibits significantly lower hydration activity than slag powder under ambient conditions, slowing the hydration rate of the system [

18,

19].

In five SOG system test groups using desulfurization gypsum to replace slag powder in 2%wt increments, strength tests reveal initial strength enhancement followed by reduction with increasing gypsum content. The maximum strength occurs at 4%wt desulfurization gypsum content, yielding 17 MPa 7-day compressive strength and 34.2 MPa 28-day strength. Appropriate gypsum addition supplements Ca²⁺ and SO₄²⁻ ions in the alkaline environment created by alkali residue and carbide slag, promoting AFt formation during slag-fly ash hydration. The interlocking needle-shaped AFt crystals form a reinforcing framework. However, excessive gypsum content induces expansion stress from unreacted gypsum during early hydration, increasing mortar porosity and reducing strength [

20].

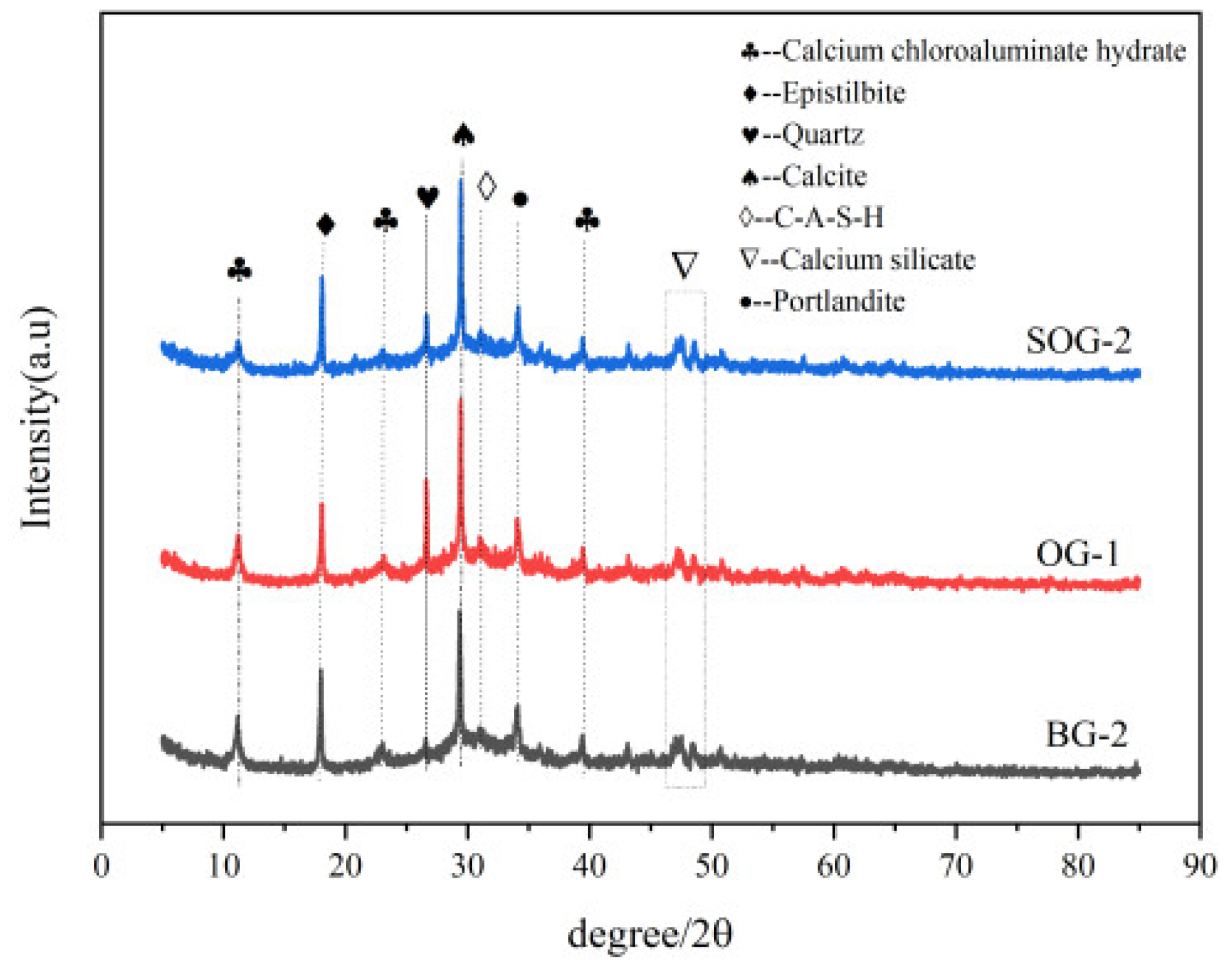

3.3. XRD Analysis

To characterize the types of hydration products formed with different precursors and activators, XRD analysis was conducted on three groups of samples (BG-2, OG-1, and SOG-2) after 28 days of hydration, with results shown in

Figure 9.The main crystalline phases identified in the three groups of samples after 28 days of hydration include Friedel’s salt (3CaO·Al₂O₃·CaCl₂·10H₂O, FS), calcite (CaCO₃), quartz (SiO₂), calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H), calcium hydroxide, calcium silicate, and zeolite (Ca₂(Si₉Al₃)O₂₄·8H₂O). Among these, FS, C-A-S-H, and zeolite are primarily generated through hydration reactions. The XRD patterns exhibit a distinct “hump” region between 20°–40°, attributed to the formation of amorphous C-S-H gel during hydration [

21]. A diffraction peak of C-A-S-H is observed near 31°, where Al³+ ions dissolved from Al₂O₃ in the precursor are incorporated into the C-S-H gel during hydration to form C-A-S-H [

22]. Simultaneously, the Si-O and Al-O tetrahedra in slag powder and fly ash undergo “depolymerization-polycondensation” reactions in the alkaline environment created by alkali residue and carbide slag dissolution, producing zeolite-type minerals (Ca₂(Si₉Al₃)O₂₄·8H₂O) [

23].

Calcite mainly originates from alkali residue, quartz from unreacted slag powder and fly ash, and calcium hydroxide from carbide slag. The diffraction peak intensity of the quartz phase in OG-1 is significantly higher than those in BG-2 and SOG-2, with BG-2 showing the lowest intensity. This is attributed to the replacement of 10 wt% slag powder with fly ash in OG-1. Given the substantially lower cementitious activity of fly ash compared to slag powder, the unreacted quartz content in OG-1 exceeds that in BG-2 under equivalent alkali residue and carbide slag conditions. In SOG-2, the addition of 4 wt% desulfurization gypsum introduces Ca²⁺ and SO₄²⁻ ions, creating a “sulfate activation” effect that enhances precursor hydration. Consequently, SOG-2 exhibits reduced quartz phase diffraction peaks compared to OG-1 [

24].

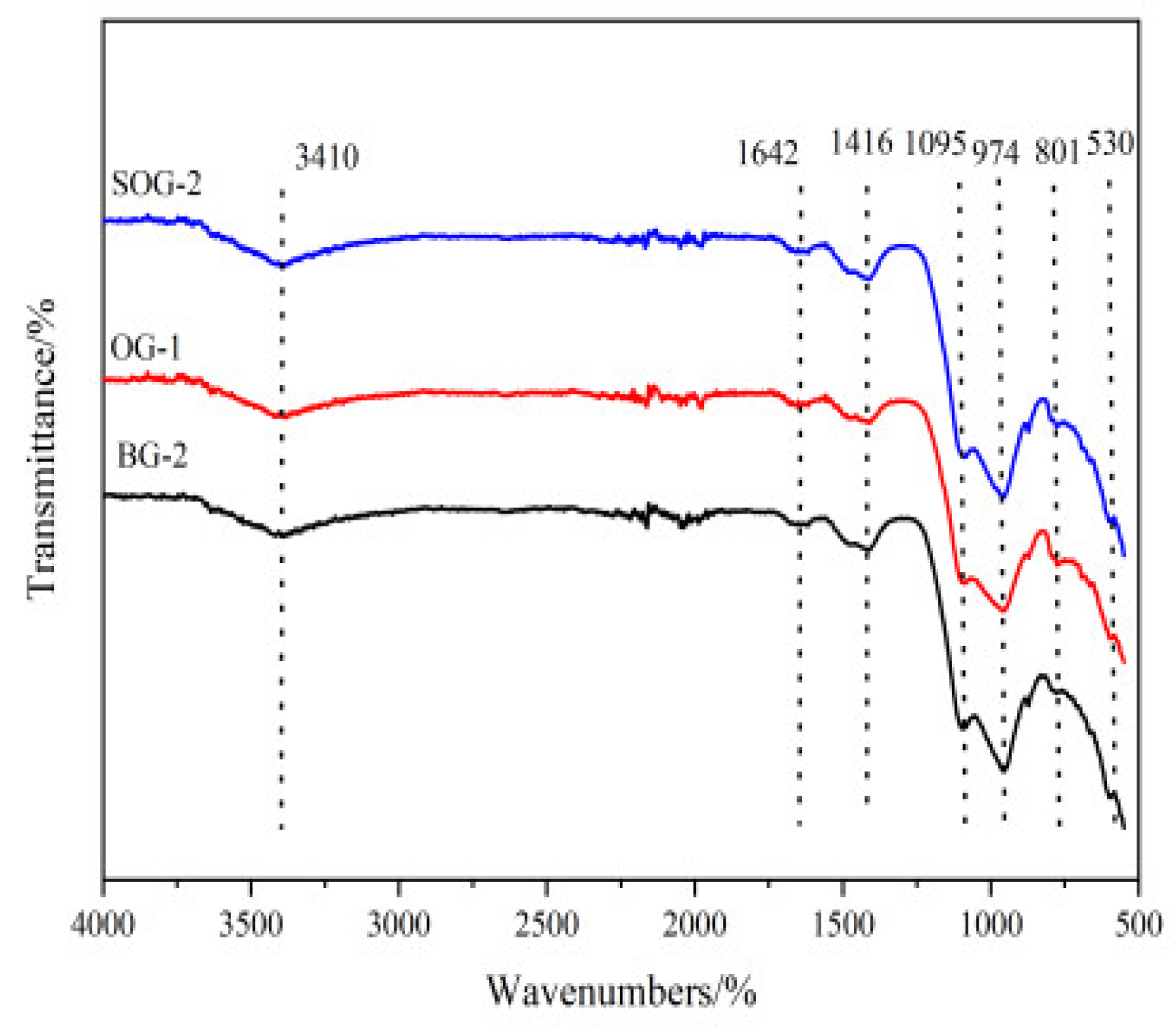

3.4. FTIR Analysis

The FTIR analysis results of 28-day hydration products for BG-2, OG-1, and SOG-2 are shown in

Figure 10. Absorption bands near 530 cm⁻¹, 801 cm⁻¹, and 974 cm⁻¹ correspond to stretching and bending vibrations of Si-O bonds, characteristic of C-S-H gel. SOG-2 exhibits the broadest and most intense absorption peaks at these positions, followed by BG-2, with OG-1 showing the weakest signals. This indicates that SOG-2 generates the highest amount of C-S-H gel after 28 days of hydration, consistent with its superior 28-day compressive strength results [

25].

The absorption band near 1416 cm⁻¹ arises from C-O bond stretching vibrations, confirming the presence of calcite [

26]. Absorption bands at 1642 cm⁻¹ and 3410 cm⁻¹ are attributed to asymmetric stretching vibrations of O-H bonds, reflecting internal vibrations of crystalline water primarily originating from C-S-H gel and Friedel’s salt (FS) [

27]. SOG-2 demonstrates the strongest intensity and broadest peaks for these features, followed by BG-2, while OG-1 shows the weakest signals. These observations suggest that SOG-2 contains the highest proportion of hydration products with crystalline water, aligning with its enhanced 28-day compressive performance compared to the other two groups.

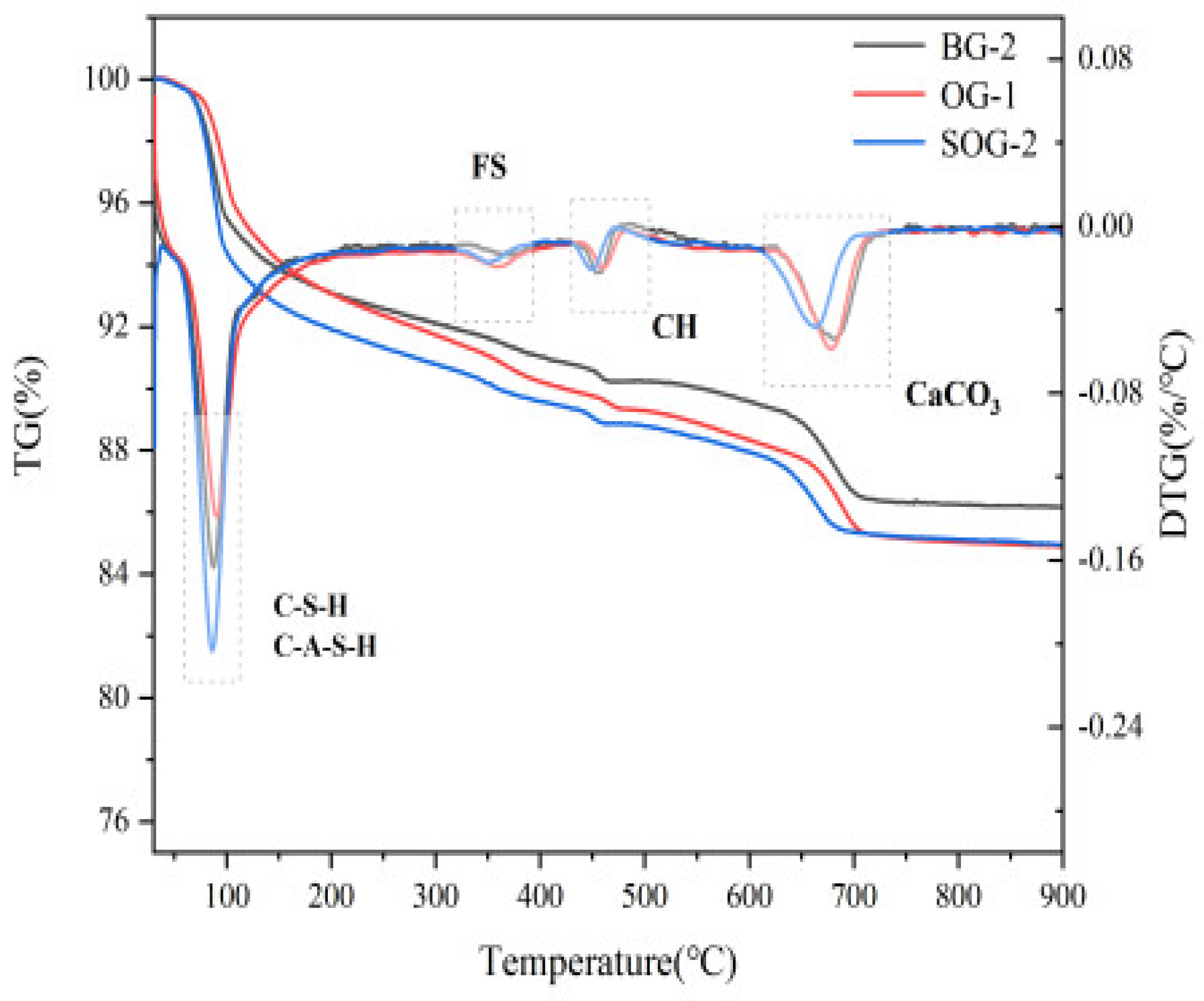

3.5. TG-DTG Analysis

TG-DTG analysis was conducted on 28-day hydrated samples of BG-2, OG-1, and SOG-2, with results shown in

Figure 11. The DTG curves exhibit four primary weight loss peaks corresponding to the decomposition and dehydration of hydration products.

The weight loss peak in the 50–200°C range primarily arises from the decomposition of C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels [

28]. Within this temperature range, these gels undergo thermal decomposition and dehydration, leading to significant weight loss in the TG curves and corresponding peaks in the DTG curves. As shown in

Figure 9, the DTG peak area in the 50–200°C range follows the order SOG-2 > BG-2 > OG-1, indicating that SOG-2 produces the highest quantity of C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels during hydration, followed by BG-2 and then OG-1. This observation aligns with the 28-day compressive strength test results of the three groups.

The weight loss peak in the 300–400°C range is attributed to the dehydration of Friedel’s salt (FS) [

29]. Thermal dehydration of FS within this temperature range generates distinct DTG peaks, with peak areas following SOG-2 > BG-2 > OG-1, suggesting that FS formation during 28-day hydration follows the same order. These findings are consistent with XRD and FIRT results.The weight loss peak in the 450–550°C range corresponds to the decomposition of Ca(OH)₂ [

9], primarily originating from unreacted calcium hydroxide in carbide slag, indicating incomplete consumption of Ca(OH)₂ during hydration. The peak in the 600–750°C range results from calcite decomposition [

30], predominantly derived from alkali residue in raw materials, with a minor portion formed through carbonation of Ca(OH)₂ during late hydration. Comparative analysis reveals that SOG-2 and BG-2 exhibit higher hydration degrees, resulting in less carbonation-induced calcite formation in SOG-2 [

31].

In summary, the TG-DTG results demonstrate full consistency with XRD and FIRT experimental findings.

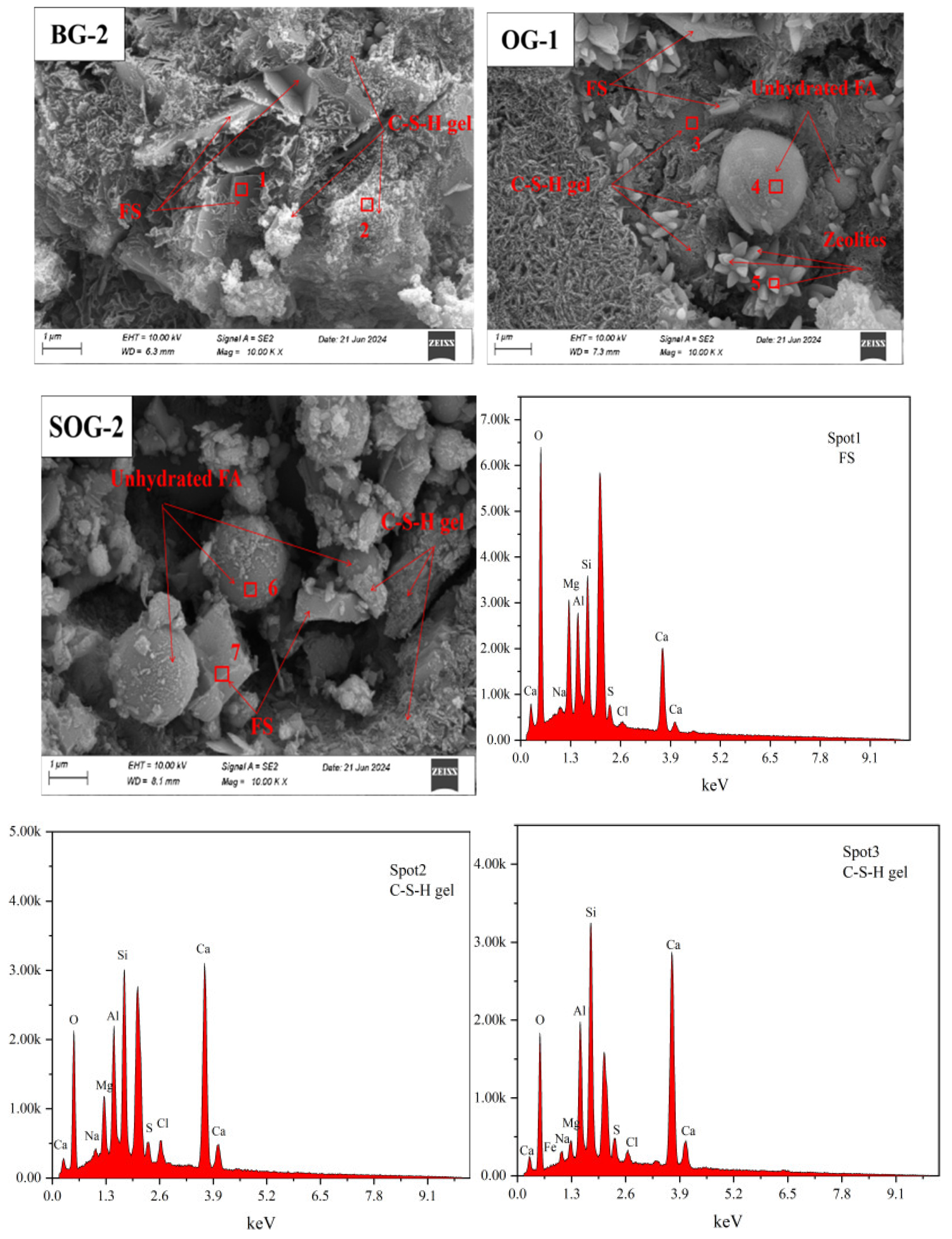

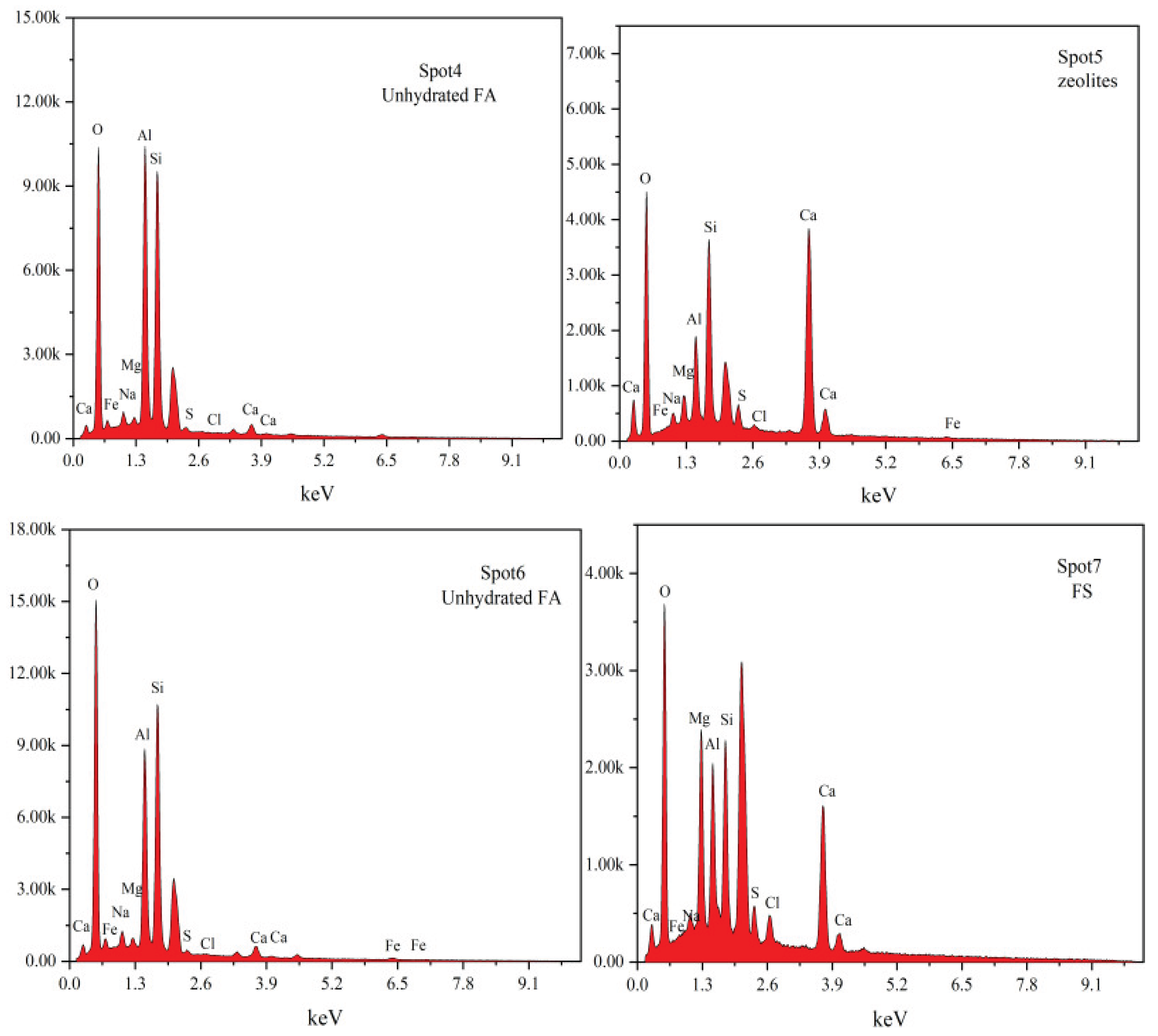

3.6. SEM-EDS Analysis

To further clarify the hydration products of cementitious materials under different mixing ratios and analyze the influence of these ratios on their microstructure, SEM-EDS analysis was conducted on 28-day hydration products of three groups of samples (BG-2, OG-1, and SOG-2), as shown in

Figure 12. The SEM-EDS results indicate that the primary hydration products of all three groups at 28 days are C-S-H gel. Among them, BG-2 exhibits the highest content of C-S-H gel, with a dense and uniformly distributed structure. Additionally, lamellar FS crystals are observed in BG-2, exhibiting a nested distribution within the C-S-H gel. This nested configuration constitutes a critical component of the cementitious strength [

32], demonstrating that the optimal dosages of alkali residue and calcium carbide residue play a pivotal role in promoting the hydration of slag powder.

Compared to BG-2, the C-S-H gel structure in OG-1 appears looser, with significantly reduced gel content, thereby impeding strength development. SEM images reveal the presence of spherical and columnar phases. EDS analysis identifies the spherical particles as unhydrated fly ash, while the columnar phase corresponds to stilbite [

33], consistent with XRD results.

In SOG-2, the hydration products primarily consist of C-S-H gel, FS crystals, and unhydrated fly ash particles. SEM images clearly show a denser C-S-H structure and increased FS content, attributed to the “sulfate activation” effect induced by the addition of desulfurization gypsum, which enhances sample strength. EDS results from Spot2 and Spot3 detect the presence of Mg, Al, and Cl elements, indicating partial substitution of Si⁴+ by Al³+ and Mg²+ in the C-S-H gel, along with Cl⁻ immobilization. Similar substitution patterns (partial replacement of Al³+ by Mg²+ and Si⁴+ in FS) are also observed in Spot1 and Spot7 [

34].

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the effects of alkali residue-calcium carbide residue on the slag powder-fly ash precursor system through compressive strength analysis and microstructural characterization of hydration products. The following conclusions were drawn:

(1)When the alkali residue and calcium carbide residue contents reached 22 wt% and 8 wt%, respectively, the highest activation efficiency for slag powder was achieved. The compressive strength reached 15.1 MPa at 7 days and 30.4 MPa at 28 days. Substituting 10 wt% slag powder with fly ash resulted in reduced compressive strength at both curing ages (7d and 28d). This decline is attributed to the significantly lower hydration activity of fly ash under ambient conditions compared to slag powder, which decelerates the overall hydration kinetics of the system.

(2)Replacing slag powder with desulfurization gypsum at 2 wt% increments initially increased then decreased compressive strength. The maximum strength (17 MPa at 7d and 34.2 MPa at 28d) occurred at 4 wt% desulfurization gypsum content. This enhancement stems from the dissolution of gypsum, which releases Ca²⁺ and SO₄²⁻ ions, inducing a “sulfate activation” effect that accelerates hydration reactions in the precursor system.

(3)XRD, FTIR, TG-DTG, and SEM-EDS analyses confirmed that the 28-day hydration products of BG-2, OG-1, and SOG-2 samples primarily consisted of FS, C-(A)-S-H gel, and zeolites. The quantities of FS and C-(A)-S-H gel followed the order: SOG-2 > BG-2 > OG-1. Alkali residue and calcium carbide residue provided the necessary alkaline environment to promote slag hydration. Fly ash substitution (10 wt%) reduced hydration products due to its slower reaction kinetics, while subsequent 4 wt% desulfurization gypsum addition enhanced sulfate activation, increasing hydration product formation.

(4)The results demonstrate the feasibility of using a fully solid-waste composite activator (alkali residue-calcium carbide residue-desulfurization gypsum) to replace conventional strong alkali chemicals for activating slag powder-fly ash systems. This approach enables the development of low-carbon cementitious materials based entirely on solid wastes, offering significant potential for advancing green building materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Huiying Zhao, Yongchun Li, Dingbang Wei; methodology, Huiying Zhao, Yapeng Wang, Xu Wu; validation, Yongchun Li, Yapeng Wang; formal analysis, Huiying Zhao, Yongchun Li, Xu Wu, investigation, Huiying Zhao, Yongchun Li, Dingbang Wei, Xu Wu, Yapeng Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Huiying Zhao; writing—review and editing, Huiying Zhao, Yongchun Li, Dingbang Wei, Xu Wu, Yapeng Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Key R&D Project of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, grant number 2022BFE02006 and 2022BEG02009.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- LIU Xianmin, Analysis of the current situation and progress of comprehensive utilization of industrial solid waste in China[J]. Resource Saving and Environmental Protection. 2021(02): 95-96.

- Ahmad M R, Qian L, Fang Y, et al. A multiscale study on gel composition of hybrid alkali-activated materials partially utilizing air pollution control residue as an activator[J]. Cement and Concrete Composites. 2023, 136: 104856.

- XIE Binbin, Characterization of geopolymer bi-liquid slurry materials in alkali-excited red mud-fly ash binary system[Z]. East China University of Science and Technology, 2022.

- LIU Yang, CHEN Xiang, WANG Boweng,et.al. Preparation and strength mechanism of alkali-excited fly ash-slag-electrolytic slag-based aggregates[J]. Silicate Bulletin.

- Cai R, Tian Z, Ye H. Durability characteristics and quantification of ultra-high strength alkali-activated concrete[J]. Cement and Concrete Composites. 2022, 134: 104743.

- Xia D, Chen R, Cheng J, et al. Desert sand-high calcium fly ash-based alkali-activated mortar: Flowability, mechanical properties, and microscopic analysis[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2023, 398: 131729.

- AN Sai, WANG Baomin, CHENG Wengxiu, et al. Mechanism of action of calcium carbide slag to stimulate slag-fly ash composite cementitious materials[J].Silicate Bulletins. 2023, 42(4). 1333-1343.

- GAO Yinli, MENG Hao, WAN Hongwei, et al. Properties and microstructure of calcium carbide slag alkali-inspired slag/fly ash cementitious materials[J]. Journal of Central South University (Natural Science Edition). 2023, 54(05): 1739-1747.

- LUO Xiaohong, ZHANG Shijun, GUO Runxing, et al, Effect of replacement of cement by calcium carbide slag as an alkali exciter on the properties and microstructure of cementitious materials made of persulfurized phosphorus gypsum[J]. Materials Herald. 2023, 37(S2): 298-304.

- GAO Yingli, ZHU Zhanghuang, MENG Hao. et al. Synergistic enhancement mechanism of calcium carbide slag-desulfurization gypsum-steel slag modified fly ash geopolymer[J]. Journal of Building Materials. 2023, 26(08): 870-878.

- SUN Lina. Preparation and hydration mechanism of polymerized materials from aged Bayer red mud bases[D]. Qingdao University of Technology, 2019.

- Hou D, Wu D, Wang X, et al. Sustainable use of red mud in ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC): Design and performance evaluation[J]. Cement and Concrete Composites. 2021, 115: 103862.

- LV ZHengye, ZHANG Yanbo, LIU Ze, et al. Study of the properties of red mud-based foamed geopolymers[J]. Silicate Bulletin. 2023, 42(10): 3624-3632,.

- YOU Hao. Experimental study on the durability of gravel stabilized by red mud-based cementitious materials[D]. Shandong University, 2023. (in Chinese)

- GUO Qilong, DU Lei, HUA Liang, et al. Performance study of alkali-excited slag-steel slag composite cementitious system[J]. New building materials, 2024, 51(01): 108-113.

- Yang J, Zeng J, He X, et al. Sustainable clinker-free solid waste binder produced from wet-ground granulated blast-furnace slag, phosphogypsum and carbide slag[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2022, 330: 127218.

- Li W, Yi Y. Use of carbide slag from acetylene industry for activation of ground granulated blast-furnace slag[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2020, 238: 117713.

- Zhuang X Y, Chen L, Komarneni S, et al. Fly ash-based geopolymer: clean production, properties and applications[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2016, 125: 253-267.

- LI Xiaomeng. Study on the effect of activated MgO on the hydration and compensation of drying shrinkage properties of alkali-stimulated fly ash-slag[D]. Hebei University, 2023.

- GAO Yingli, MENG Hao, LENG Zheng. et al. Properties and microstructure of calcium carbide slag-desulfurization gypsum composite excitation filling material[J]. Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering (in English and Chinese). 2023, 45(03): 99-106.

- Guo W, Wang S, Xu Z, et al. Mechanical performance and microstructure improvement of soda residue–carbide slag–ground granulated blast furnace slag binder by optimizing its preparation process and curing method[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2021, 302: 124403.

- Li W, Yi Y. Use of carbide slag from acetylene industry for activation of ground granulated blast-furnace slag[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2020, 238: 117713.

- Guo W, Zhang Z, Bai Y, et al. Development and characterization of a new multi-strength level binder system using soda residue-carbide slag as composite activator[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2021, 291: 123367.

- Kumar S, Maradani L S R, Mohapatra A K, et al. Effect of mix parameters on chloride content, sulfate ion concentration, and microstructure of geopolymer concrete[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2024, 435: 136864.

- Guo W, Zhang Z, Bai Y, et al. Development and characterization of a new multi-strength level binder system using soda residue-carbide slag as composite activator[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2021, 291: 123367.

- García Lodeiro I, Macphee D E, Palomo A, et al. Effect of alkalis on fresh C–S–H gels. FTIR analysis[J]. Cement and Concrete Research. 2009, 39(3): 147-153.

- XU Dong, NI Weng, WANG Qunhui, et al. Preparation of clinker-free concrete with alkali slag composite cementitious materials[J]. Journal of Harbin Institute of Technology. 2020, 52(08): 151-160.

- Li W, Yi Y. Use of carbide slag from acetylene industry for activation of ground granulated blast-furnace slag[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2020, 238: 117713.

- Wang Q, Li J, Yao G, et al. Characterization of the mechanical properties and microcosmic mechanism of Portland cement prepared with soda residue[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2020, 241: 117994.

- Abdalqader A F, Jin F, Al-Tabbaa A. Characterisation of reactive magnesia and sodium carbonate-activated fly ash/slag paste blends[J]. Construction and Building Materials. 2015, 93: 506-513.

- XU Dong, NI Weng, WANG Qunhui, et al. Preparation of clinker-free concrete with alkali slag composite cementitious materials[J]. Journal of Harbin Institute of Technology. 2020, 52(08): 151-160.

- ZHAO Guanqun. Durability and micro-mechanism of alkali slag-electric slag-inspired mineral powder-fly ash cementitious material system[D]. Yanshan University, 2022.

- WEI Erna. Preparation and transformation mechanism of zeolite (NaA/NaX/SOD) microspheres with different geopolymerization and their adsorption properties on Pb~(2+)[D]. Guangxi University, 2022.

- Liu X, Zhang N, Yao Y, et al. Micro-structural characterization of the hydration products of bauxite-calcination-method red mud-coal gangue based cementitious materials[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2013, 262: 428-438.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).