1. Introduction

The iron and steel industry is a pillar of the worldwide economy and an energy-intensive consumer. In 2021, the global crude steel production reached 1958.4 million metric tons (Mt), of which European Union accounted for152.8 Mt [

1]. The production of iron and steel is accompanied by large amount of metallurgical slag generated during smelting [

2]. According to different steelmaking methods, steel slag can be subdivided into: conversion slag or basic oxygen furnace slag - resulted from the refining of crude iron; electric arc furnace slag from recycled scrap and/or crude iron; argon oxygen decarburization slag - derived from the decarburization and desulfurization of stainless steel; ladle furnace slag from the refining of steel in a ladle furnace; and other secondary metallurgical slags [

3]. Each slag type possesses specific properties and potential application. Certain slags are well-utilized, such as ground granulated blast furnace slag as a supplementary cementitious material [

4]; or aggregated slags utilized in road base construction and asphalt mixtures [

5,

6]. Other low reactive slag such as ladle slag hardly find application outside the steel industry and consequently stockpiled outside [

7].

The ladle metallurgy furnace is part of a secondary steelmaking process of high-alloyed steel and an additional refining step after the basic oxygen furnace or electric arc furnace process [

8]. The production of steel generally includes primary steelmaking and secondary treatment procedures. After the primary treatment process, the generated molten steel is cast into ladle furnace. The ladle furnace heats the steel using graphite electrodes [

9]. The ladle slag commonly consist of: dicalcium silicate (C

2S), mayenite (C

12.Al

7), periclase (MgO), bredigite (C

12MgS

4), free lime (CaO), etc. [

10]. Since the ladle slag is produced from a slow cooling process, the dicalcium silicate is transformed from β-C

2S to γ-C

2S. This transformation is accompanied by volume expansion and self-powdering, which means that ladle slag is unsuitable to be used as aggregates [

11]. Moreover, the γ-C

2S is considered as scarcely reactive with water at normal conditions [

12]. Still ladle slag implies certain potential as construction material, despite rather weak hydration and along with other difficulties to be used as binding material. However, it was found that the binding properties of ladle slag and particular γ-C

2S can be greatly enhanced through alkaline activation [

13,

14,

15].

Alkaline activation is based on reaction between solid aluminosilicate precursors under alkaline conditions [

16]. The alkaline activation of slags have been widely discussed and promoted as component of the toolkit of ‘sustainable cementing binder systems’ [

17]. However, several authors used different ladle slags to obtain alkali-activated materials. The most common activators used are: mixture of sodium silicate and sodium hydroxide [

7,

18,

19], sodium silicate and potassium hydroxide [

20]; and potassium silicate [

21]. The alkali-activated ladle slag showed high compressive strength (up to about 65 MPa) and durability [

22]. Even though, some authors reported rather not effective activation of ladle slag with NaOH, Na

2SO

4 and/or sodium silicate [

23,

24]. However, despite the relatively respectable results using alkali silicates activators, the later are expensive and bring significant environmental impact [

25]. This triggers extensive research of alternative alkaline activator based on waste or by-products [

26]. Effective replacement of commercial sodium silicates were done hydrothermal dissolution of: waste glass [

27], rice husk ash [

28], silica fume [

29], sugarcane straw ash [

30], etc. Directly usage of alkaline waste solution as activators utilizing aluminum anodizing etching solution [

31] and Bayer liquor [

32] are also possible. Another approach is using dry activators and design an one-part alkali-activated cement [

33]. In this method the activator solution is replaced by solid materials consist of alkali or alkali-earth components in a reactive form. Among dry activators derived from waste products different types of biomass ash are suitable as activators due to their high alkaline character [

34]. For example, several biomass ashes were used as dry activators such as: maize stalk and cob ashes [

35], olive stone ash [

36], almond-shell ash [

37], wood ash [

38], and coffee husk ash [

39]. Additionally, one-part cement formulations are considerably more user-friendly requiring only the addition of water similar to conventional Portland cement.

The present study aims to explore the potential of sunflower shell fly ash (SSFA) as a dry alkali activator for one-part alkali-activated cement based on ladle slag. Given the high alkalinity and reactive silica content of biomass ashes, SSFA is investigated as an alternative to conventional liquid activators, which are often costly and environmentally heavy. This study evaluates the physicochemical interactions between ladle slag and SSFA, assessing the phase evolution, microstructure, and mechanical properties of the resulting cementitious material. The findings contribute to the development of cost-effective one-part alkali-activated binders, promoting the valorization of industrial and agricultural waste in sustainable construction applications.

2. Materials and Methods

The main raw material for the preparation of alkali-activated material was ladle slag (LS). The ladle slag is a by-product of secondary refinement steel, provided by Stomana Industry, S.A, Bulgaria. The LS was temporary stored at stockpiles at steel plant yard. Representative sample of 10 kg ladle slag was collected, dried to constant mass at 80 ºC and grinded with steel ball mill for 1 hour. The role of dry activator at the presented study was biomass fly ash from sunflower shells (SSFA) generated from the combustion of sunflower shells cake in a boiler producing water steam. The SSFA was collected from bag cyclone filter at the Biodiesel Plant of the company Astra Bioplant EOOD company in the town of Slivo Pole, Ruse region, Bulgaria. The SSFA was dried to constant mass at 80 °C and milled for 1 hour in a ceramic ball mill. The alkali activated mixtures was obtained by using tap water.

The chemical composition of the precursors was determined by XRF using pressed pellets, analyzed on Rigaku Supermini 200WD apparatus, Rigaku Corporation, Osaka, Japan. The powder X-ray diffractograms were obtained on Empyrean (Malvern-Panalytical) diffractometer using CuKα radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA. The infrared spectra were measured using Zn-Se ATR accessory and Tensor 37 (Bruker) spectrometer at averaging over 128 scans with ± 2 cm-1 spectral resolution. The thermal analyses were carried out on the DSC-TG analyser SETSYS2400, SETARAM at the following conditions: temperature range from 20 to 1000 oC, in a static air atmosphere, with a heating rate of 10 oC min-1, and 10 – 15 mg samples mass.

Compressive strength was measured on 3 cubic specimens with one side area of 10 cm2. Density of each series was calculated using dry mass and measuring the dimensions of three specimens per series by digital caliper with resolution of 0.01 mm.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Precursors

The chemical composition of the two raw materials (LS and SSFA) used in the presented study is shown in

Table 1. The dominant oxides in the LS sample were CaO, SiO

2 and Al

2O

3. Additionally, the magnesium oxide (MgO) content was measured at 6.5 wt%. A certain amount of sulfur was also detected, calculated as sulfate (SO

3).

On the other hand, the SSFA exhibits a distinct chemical profile, being exceptionally rich in potassium (K

2O), which accounts for over 61 wt%. This is in line with the composition of sunflower shells ash reported by Lokare at al. [

40], and Vassilev et al.[

41], the K

2O content of = 45,1%, and 4,8%. They also report significant amount of P

2O

5 content (7- 10%) which fraction is discarded in the fly ash. Some authors report high content of SiO

2 for SSA which is probably due to contamination with sand and dust on the harvesting and processing of the sunflowers [

42,

43]. Notable quantities of alkaline-earth oxides, such as CaO (15.43 wt%) and MgO (2.33 wt%), were identified at SSFA. Sulfur and chlorine were also present in significant amounts, with SO₃ reaching 14.02 wt% and Cl at 4.78 wt%. Elements such as S, Cl and K are enriched in fly ashes due to their significant volatile nature during biomass combustion and often are transported by flue gases and subsequent condensation in fly ashes [

44].

The high calcium content in LS, combined with the alkali and alkali-earth nature of SSFA, suggests their potential for synergistic interactions in cementitious or geopolymer applications.

The high calcium content in LS, combined with the alkali and alkali-earth nature of SSFA, suggests their potential for synergistic interactions in cementitious or geopolymer applications.

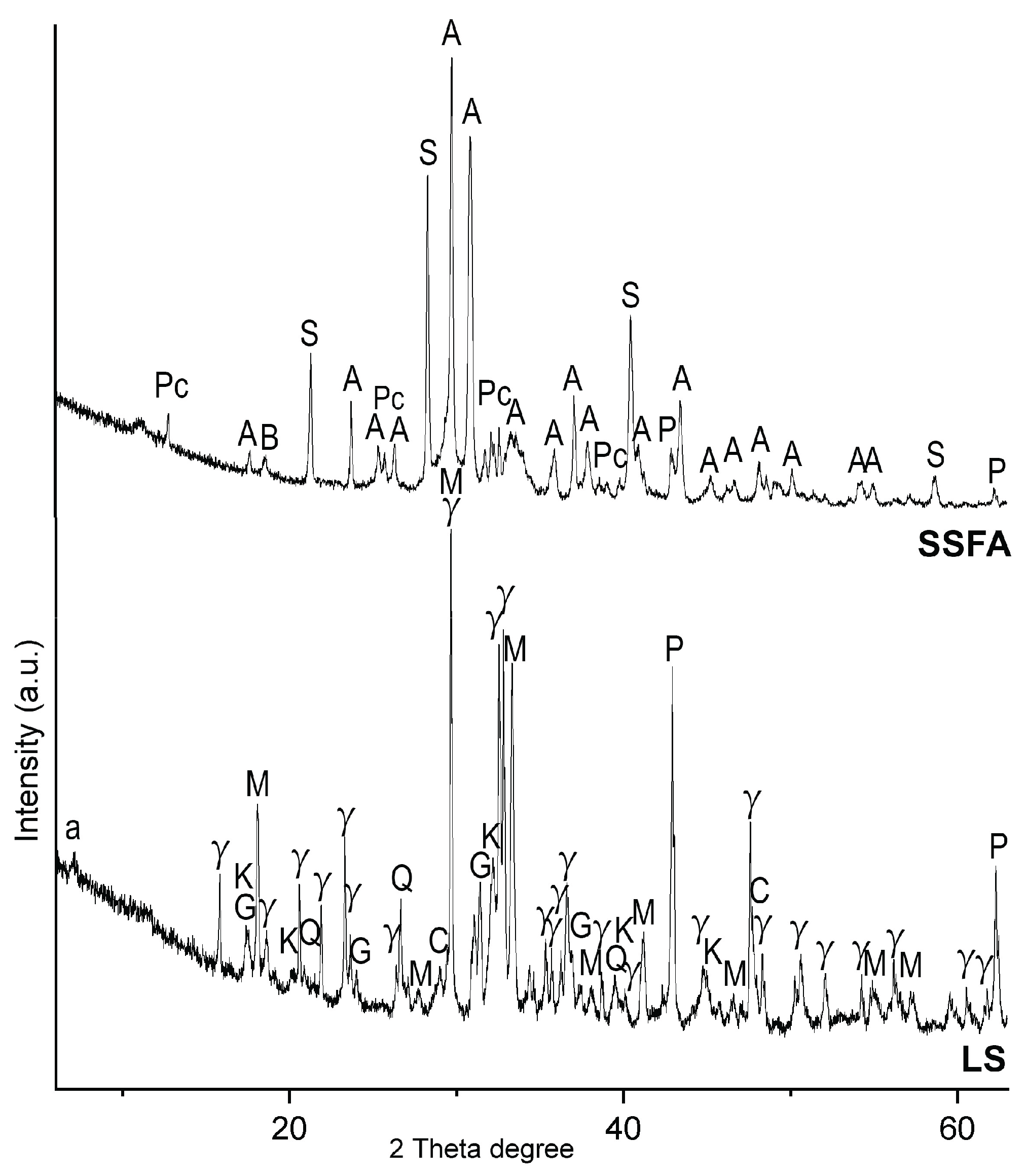

The mineral composition of the precursors is presented in

Figure 1. The LS exhibited a well-crystalline structure, indicative of slow cooling during its formation. The dominant crystalline phase in LS was γ-belite (Ca

2SiO

4), a calcium disilicate phase that forms under slow cooling conditions and contributes to the material’s latent hydraulic properties [

45]. The second major phase identified was mayenite (Ca

12Al

14O

33), a calcium aluminate phase known for its high reactivity and rapid setting[

46]. Additionally, periclase (MgO) was detected, often regarded for its role in volume stability on hydration [

47]. Gehlenite (Ca₂Al₂SiO₇), an active in hydration phase, was also presented enhancing the reactivity of the slag in cementitious systems. Minor amount of strätlingite (Ca₂Al₂SiO₇·8H₂O), katoite (Ca

3Al

2(SiO

4)(OH)

8) and brucite (Mg(OH)

2) were also detected, probably as a product of natural hydration due to outside pile storage of the LS at the steel producing plant. Calcite was also detected probably as a product of natural carbonation.

In contrast, the mineral composition of biomass fly ash from sunflower shells (SSFA) was dominated by arcanite (K₂SO₄) and sylvite (KCl). The high potassium content in SSFA promotes natural carbonation processes, resulted to the formation of potassium carbonate hydrate (K₂CO₃·1.5H₂O). The strong hygroscopic nature of sylvite accelerates the carbonation, further facilitating the transformation to potassium-bearing carbonate phases. Despite the dominance of crystalline potassium salts, the chemical and mineral composition results suggest that a certain amount of the potassium remains in an amorphous phase, as inferred from the high K₂O content determined by XRF. Minor amount of brucite was also detected.

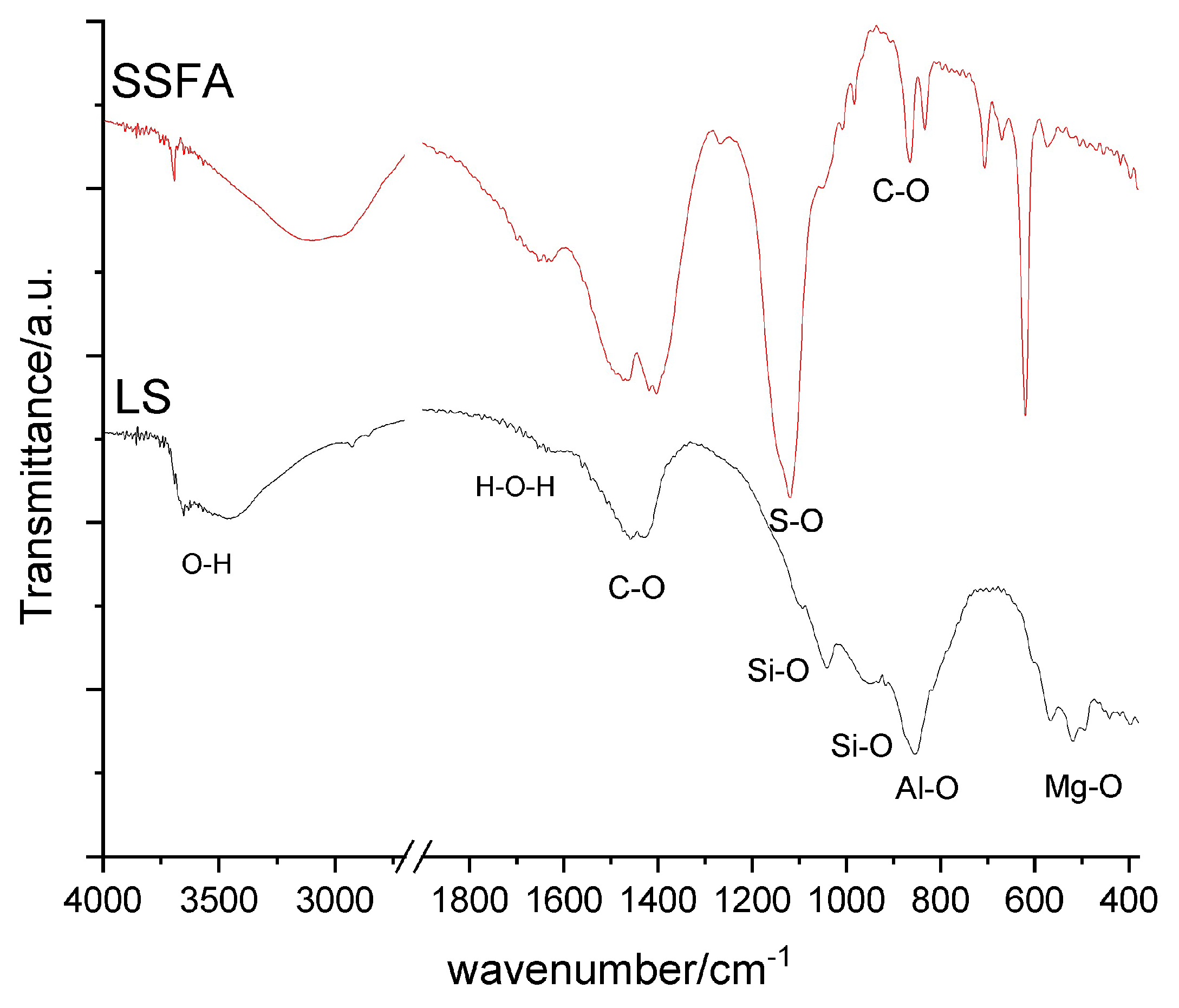

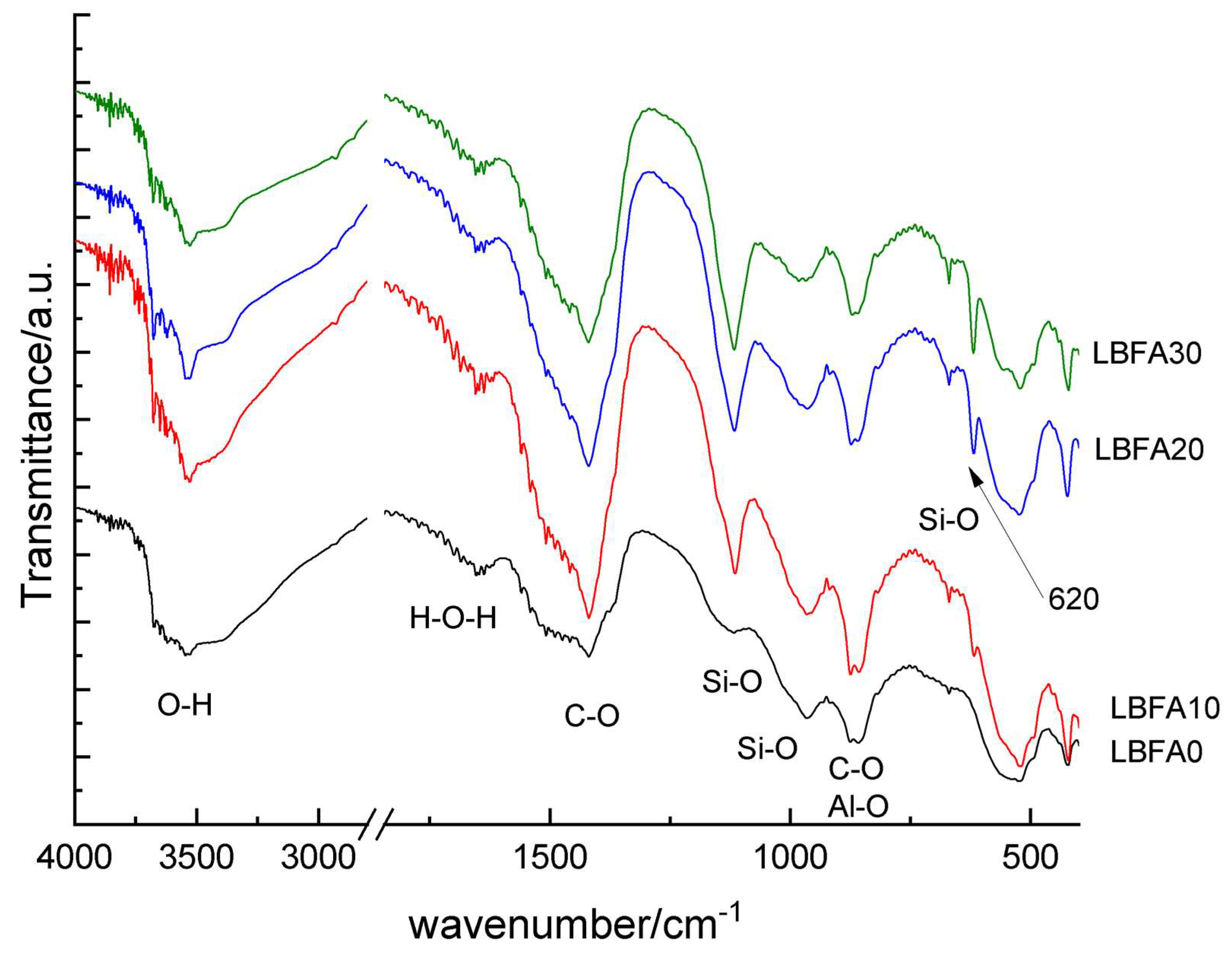

The infrared spectra of raw materials LS and SSFA are presented on

Figure 2 . The two starting materials have a complex phase composition, whereby the peaks in the spectra overlap and make interpretation difficult. However, some conclusions can be drawn and contribute to the description of the source materials.

The most intensive absorption peak of the LS is centered at 855 cm

-1, which is in the range of Al-O stretching vibrations of AlO

4 tetrahedra in mayenite [

48]. Asymmetric Al-O stretching of other aluminosilicates presented in the ladle slag (LS) also contribute in the range 800-870 cm

-1. Silicate minerals already detected by powder diffraction data are γ-belite – (γ-Ca

2SiO

4), gehlenite (CaAl(AlSiO

7), katoitite (Ca

3Al

2SiO

4 OH

8) and strätlingite (Ca₂Al₂SiO₇·8H₂O). In general, minerals containing silicate groups exhibit characteristic infrared absorption bands due to stronger Si–O stretching and less intensive bending vibrations. These bands typically appear in the range of 800–1200 cm⁻¹ for stretching vibrations and 400–600 cm⁻¹ for bending vibrations

. Bands due to Si–O stretching are visible near 960 and 1040 cm

-1 cm

-1. At such frequencies one would expect the intense absorption bands of belite, gehlenite and other silicate phases presented in the sample [

49,

50]. Strätlingite is a hydrated calcium aluminum silicate hydrate (also called gehlenite hydrate) which forms in hydrated cement systems and is important in cement chemistry

. The infrared spectrum shows peaks related to water molecules at 3450 and 1640 cm

-1 which could be attributed to this phase. Strong peaks in the range of carbonate stretching region at 1458 and 1429 cm

-1 indicate presence of carbonate minerals. Calcite is confirmed by the infrared absorption at 2926w, 2860w, 1429s, and a shoulder at 870 cm

-1 [

51]. Brucite (MgOH

2) is detected by the strong and sharp peak at 3660 cm

-1 due to O-H stretching vibration [

52].

The most intensive sharp peaks in the infrared spectrum of SSFA (

Figure 2) at 1119 cm

-1 and 620 cm

-1 are indicative for potassium sulfate arcanite (K

2SO

4)[

53]. The strong absorption at 1400-1470 cm

-1 and at 830-870 cm

-1 correspond to asymmetric stretching (ν

3) and out-of-plane bending (ν

2) modes of the carbonate ion, respectively. These carbonate peaks and characteristic absorption bands of water at 3100 - 2967 cm

-1 and at 1630 cm

-1 confirm the presence of potassium carbonate sesquihydrate [

54]. Strong and sharp peak at 3690 cm

-1 is characteristic for hydroxyl group stretching in brucite.

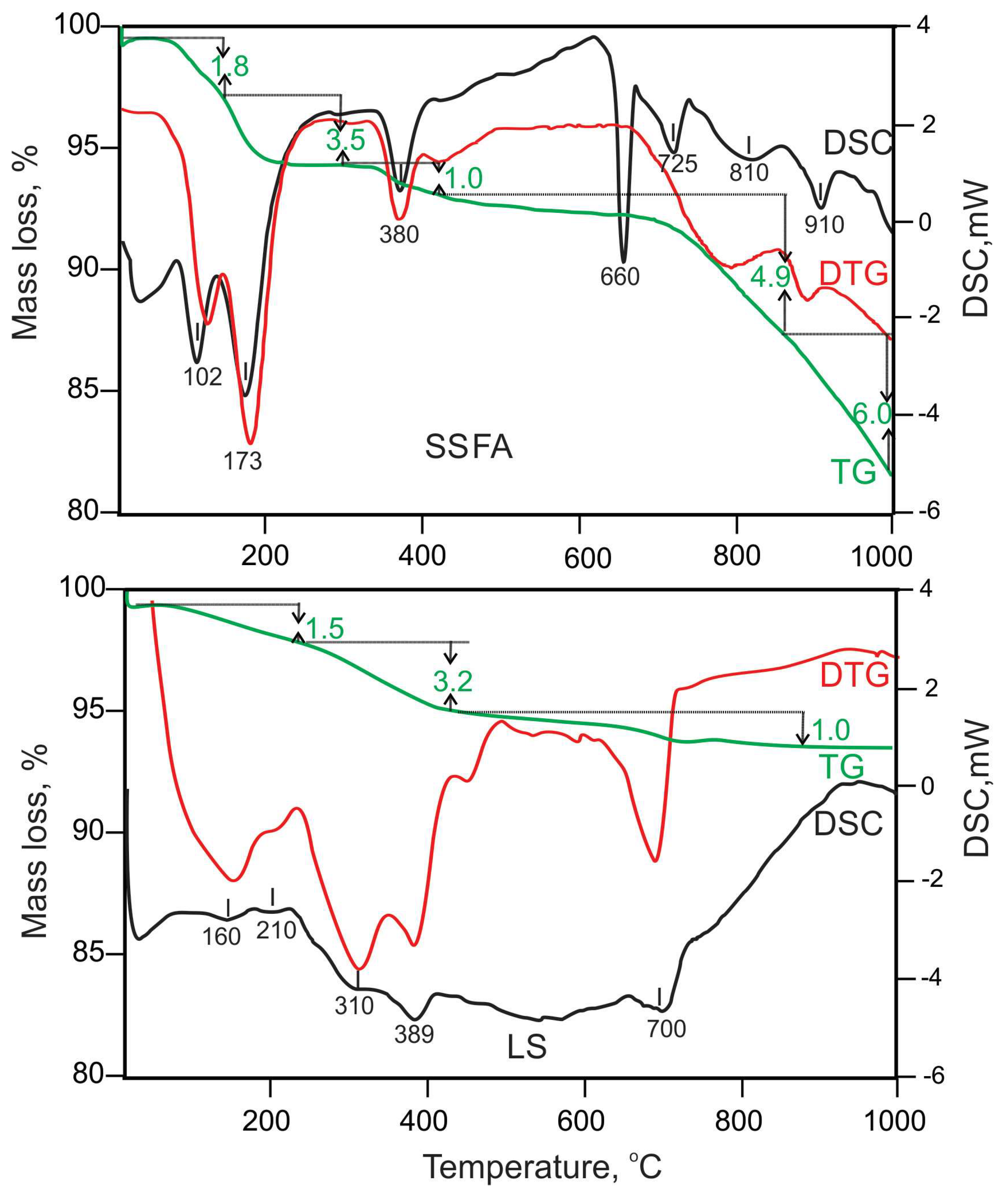

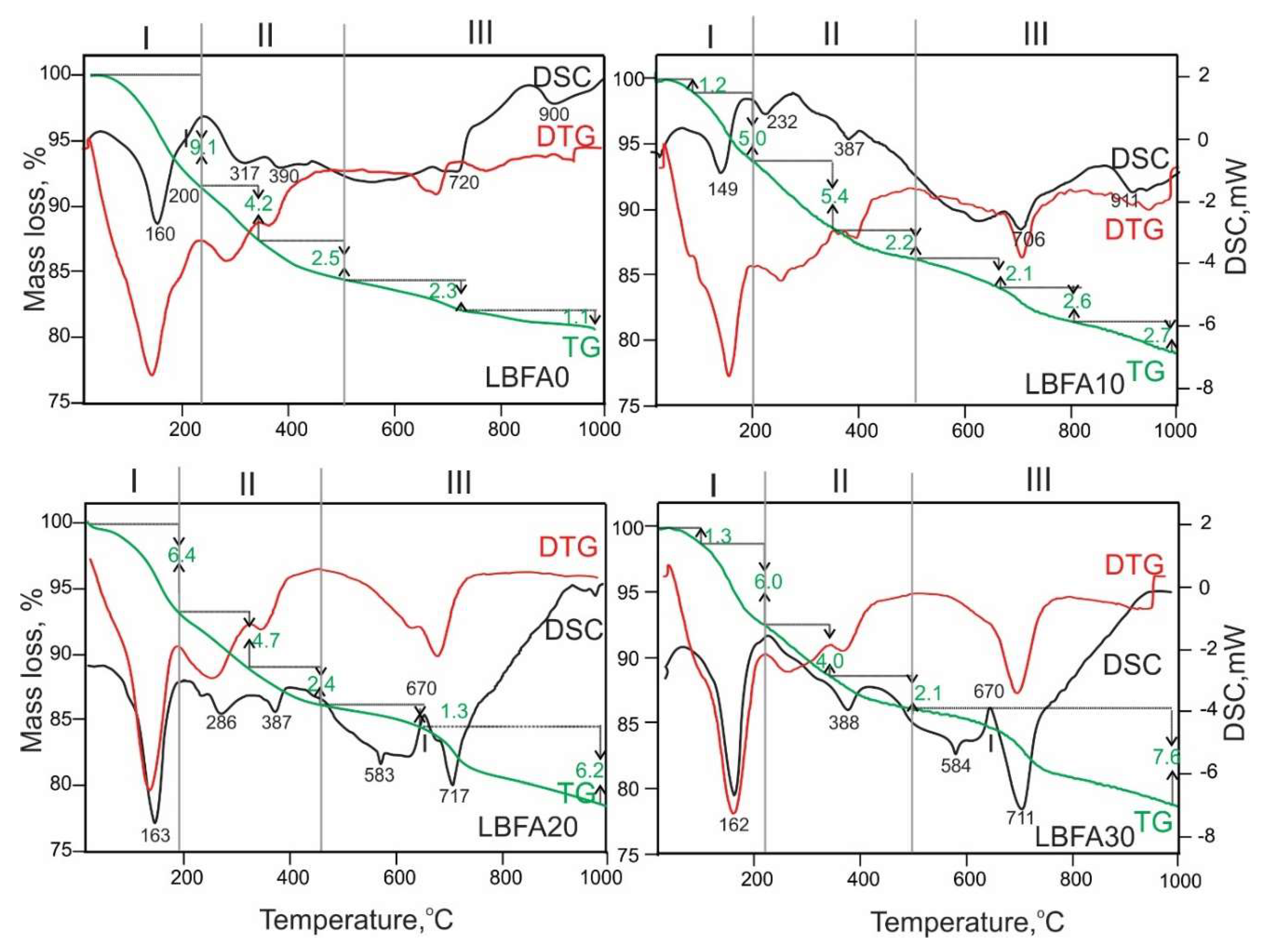

The thermal behavior of both precursors LS and SSFA is shown on

Figure 3. The LS exhibits insignificant mass losses on the TG curve and endothermic effects on the DSC curve within the temperature range of 25-400°C indicating the presence of a minor amount of hydrate phases due to weathering of the ladle slag. Minor endo-effects about 160°C and 210°C were related to strätlingite [

55], while katoite decompose at about 310°C [

56]. The distinct endothermic peak at 389°C is characteristic for brucite dehydration [

57]. The endothermal event at about 700°C is due to the presence of a carbonate mineral (calcite), the amount of which calculated from the TG curve is below 0.5%. The major mineral phases identified by PXRD such as γ-belite, mayenite, gehlenite and periclase are thermally stable in this temperature region without expressions on the registered curves. In contrast to LS, SSFA shows more complicated thermal behavior. The only one identified hydrate phase by PXRD was KCO₃·1.5HO which during heating from 25 to 300°C dissociates to anhydrous form. The decomposition endo-effect of K

2CO

3 is around 900°C accompanied by mass loss. It is known that the suitable sintering temperature for this compound should be below the decomposition temperature [

58]. Endothermal peak at about 380°C is related to brucite dehydration. The sharp endo-effect at 660

oC and 725

oC are probably attributed to the two-step melting of KCl [

59]. The melting point of pure KCl is 776°C but when this potassium salt is presented together with other salts this temperature being considerably lower due to possible eutectics [

60]. The KCl decomposition starts immediately after its melting.

3.2. Influence of Sunflower Shells Fly Ash Addition to Ladle Slag

The influence of different amount of SSFA addition (from 0 up to 30%) to ladle slag was investigated. The composition design of the prepared series is presented in

Table 2. The ladle slag and SSFA were placed in a laboratory planetary mixer to obtain homogenous dry mixture. The water to solid ratio of all series were fixed to 0.35. The fresh alkali-activated paste was stirred 2 minutes and poured in steel moulds wrapped in polyethylene foil. The samples were demoulded after one day and stored at laboratory conditions. The properties of the obtained alkali-activated materials were examined at the 28-th day.

3.2.1. Physical Properties

The hydration of ladle slag (LS) alone resulted in the formation of a relatively weak material, achieving a compressive strength of approximately 10 MPa (

Table 2). This indicates that LS, when used independently, exhibits limited self-cementing properties. However, the incorporation of 10 wt% SSFA significantly enhanced the compressive strength, increasing it by approximately threefold to 29.6 MPa. This remarkable improvement suggests that the presence of SSFA contributes to enhanced reaction kinetics and possibly the formation of additional binding phases. Further increasing the SSFA content to 20 wt% led to a decrease in strength (22.4 MPa), although the material still exhibited a notable improvement compared to the reference LS paste. A more pronounced reduction in mechanical performance was observed at 30 wt% SSFA, where the compressive strength dropped to 11.6 MPa, approaching the strength of the pure LS system. This decline may be attributed to an excessive sulfates and chlorides, or increased porosity associated with higher SSFA content.

In addition to mechanical properties, density measurements revealed that the alkali-activated pastes had relatively low bulk density, which further decreased with the progressive addition of SSFA. The reference paste (LBFA0) exhibited a density of 1.591 g/cm³, and the density decreased to 1.569 g/cm³, 1.560 g/cm³, and 1.548 g/cm³ for LBFA10, LBFA20, and LBFA30, respectively. This trend suggests that the incorporation of SSFA introduces a degree of porosity or reduces the packing density of the solid matrix, likely due to the physical and chemical nature of SSFA and reactions with LS.

The results demonstrate that a moderate substitution of 10 wt% SSFA optimally enhances strength, while excessive replacement leads to a decline in mechanical performance.

3.2.2. Microstructural Characterization

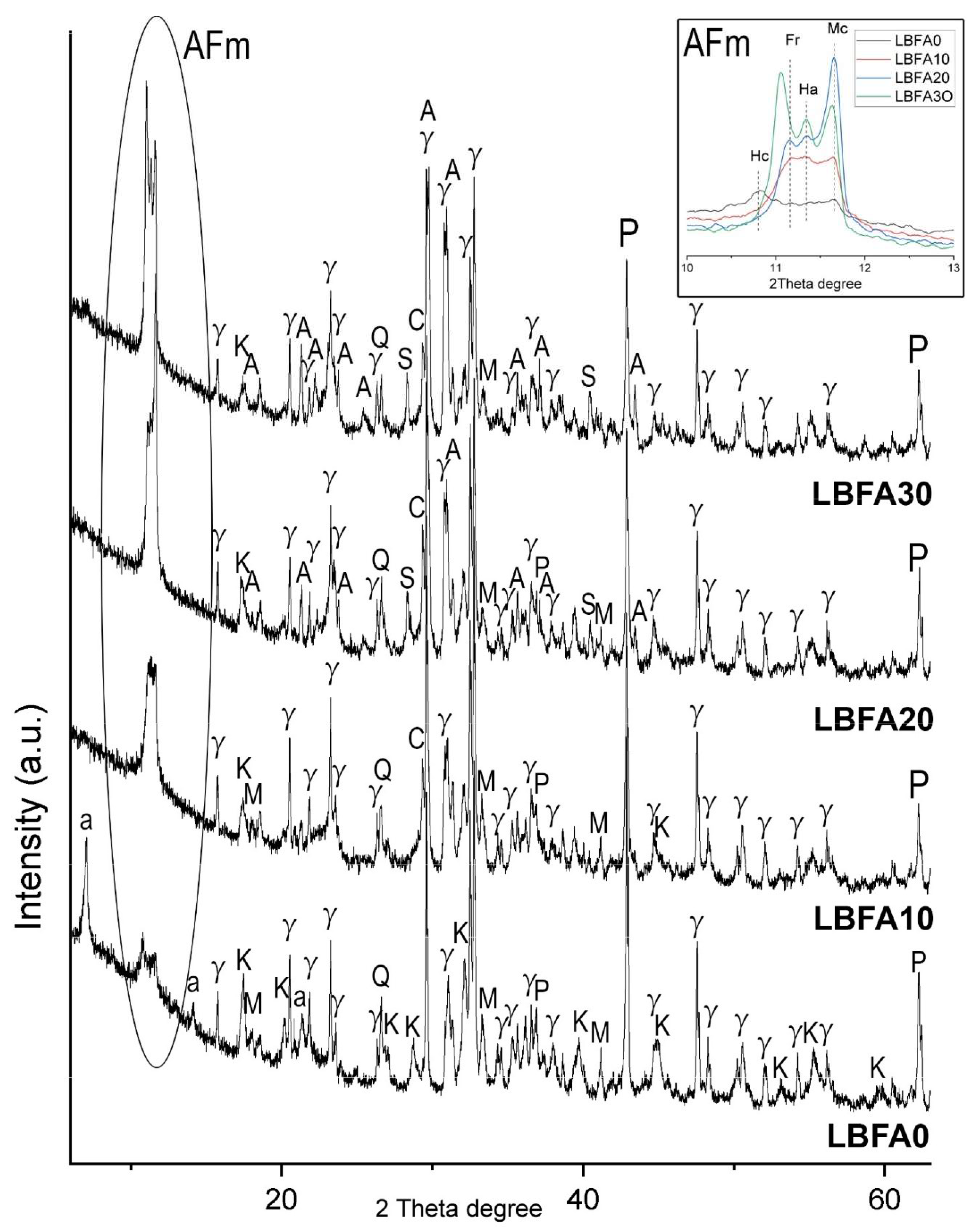

The primary reactive phases within the ladle slag were identified as mayenite (Ca₁₂Al₁₄O₃₃) and gehlenite (Ca₂Al₂SiO₇). Upon hydration of the ladle slag, strätlingite [(Ca₂Al₂SiO₇)·8H₂O] was formed as a dominant phase (LBFA0), followed by the relative increase of katoite phase (

Figure 4). Hemicarboaluminate (Hc) [3CaO·Al₂O₃·Ca(OH)(CO₃)₀.₅·xH₂O] and monocarboaluminate (Mc) [3CaO·Al₂O₃·CaCO₃·xH₂O] were also formed as a products of natural carbonation.

The incorporation of SSFA altered the formation of strätlingite and katoite. Instead, the presence of chloride ions in SSFA promoted the crystallization of AFm phases - a family of hydrated calcium aluminate phases representing a layered double hydroxides with a representative formula [Ca

2(Al,Fe)(OH)

6]·X·nH

2O where X equals an exchangeable single charged anion (such chloride) or half of a double charged (sulfate, carbonate). The AFm phases exhibit variable compositions and significantly influence cement performance, including strength, durability, and chemical stability [

61]. The main phases detected in the LS activated by SSFA was hydrocalumite [3CaO·Al₂O₃·Ca(OH)₂·10H₂O], Friedel’s salt [3CaO·Al₂O₃·CaCl₂·10H₂O] and Mc. The amount of Mc increased suggesting enhanced carbonation due to SSFA addition. Presence of sylvite and arcanite in the system increased the hygroscopicity of the material, which accelerates the natural carbonation [

62]. Ettringite and monosulfoaluminate phases were not detected. The formation of hydrotalcite phase is also possible but its main peak overlaps with monocarboaluminate [

63]. The presented AFm phases (Friedel’s salt, hydrocalumite, Hc, Mc) are referred as stable at normal conditions and contribute to mechanical strength of the obtained material [

64,

65].

The γ-belite (2CaO·SiO

2) and periclase (MgO) remained relatively inert even after the addition of SSFA, indicating their lack of hydration under the given conditions. Periclase (MgO) is often negatively associated with volume stability of cementitious systems due to its potential late-stage hydration. The potassium-rich environment did not significantly promote the periclase hydration. The stability of periclase in this system can be attributed to its “dead-burned” nature. Dead-burned periclase refers to MgO that has undergone high-temperature sintering—typically around 1500°C—within the molten mass of the kiln, resulting in a highly crystalline, dense, and refractory phase with significantly reduced reactivity [

66]. Dead-burned MgO exhibits minimal hydration in conventional cementitious systems due to its low solubility and slow reaction kinetics [

67]. Periclase and γ-belite stayed relatively inert even at SSFA addition.

The FTIR measurements were conducted to investigate the effect of varying SSFA additions (0–30%) to ladle slag. Infrared spectra of the alkali activated material based on LS and SSFA are shown on

Figure 5. The main phases already detected in LBFA0 upon hydration and carbonation of LS are strätlingite (Ca₂Al₂SiO₇·8H₂O), katoite (Ca

3Al

2SiO

4OH

8), hemicarboaluminate [3CaO·Al

2O

3·Ca(OH)(CO

3)

0.5·xH

2O] and monocarboaluminate [3CaO·Al

2O

3·CaCO

3·xH

2O]. In a mixture containing these phases, the IR spectrum displays overlapping bands in O-H stretching range around 3400 cm

-1 due to hydroxyl groups and water molecules, carbonate stretching and bending near 1420 and 870 cm

-1 as well as peaks in the range 1100-500 cm

-1 due to Si-O and Al-O stretching and bending vibrations. The addition of SSFA leads to a clear trend: the appearance of peaks at 1117 and 620 cm⁻¹ in LBFA10, which intensify progressively up to LBFA30, corresponding to vibrations of the sulfate group. This is a main spectral indication of the increasing amount of arcanite (K

2SO

4) with increasing amount of added SSFA, since the mineral remains stable.

The thermal behavior of alkali activated material based on ladle slag and biomass ash from sunflower shells is presented in

Figure 6. As was mentioned, the hydration of LS alone and especially in combination with SSFA promote the crystallization of AFm phases - a family of hydrated calcium aluminate phases and hemi-, monocarboaluminates. This provokes the manifestation of a number of processes during the heating. The data concerning the mass losses and related to them endothermal events could be in general separated into three temperature regions: (I) from 25 to 200

oC; (II) from 200 to 500

oC and (III) from 500 to 1000

oC. This grouping depends on the specific thermal behavior of the series compounds under study and therefore it is not exactly fixed. In the first temperature region a dehydration process occurs. In the second one, along with the completion of the dehydration, a dehydroxylation process also proceeds. While in the third region, a decarbonation of the carbonate-containing phases and probably desulfation mainly takes place. Such kind of observations have been also noted by other authors [

68,

69]. In the first temperature region the dehydration processes are manifested by a well-defined endothermal effect at about 150-160

oC which is related to strätlingite dehydration and AFm phases [

55]. The small shoulder at 200

oC observed in series LBFA0 is characteristic for strätlingite [

70]. In the second region, the endothermal events are more complicated due to the dehydroxylation existence. The endo-effects about 317

oC are related to katoite dehydration which is most pronounced at series LBFA0 [

56]. All of the series showed endo effect at about 387

oC related for brucite dehydraton. The endothermal effect at about 286

oC most pronounced at series LBFA20 is related to Friedel salt dehydration. The Friedel’s salt recrystalise to calcium chloroaluminate at about 670

oC [

71]. It becomes clear that the presence of hydrated calcium aluminate minerals is quite diverse, especially since a hydrated component is also presented in the carbonate or semi-carbonate phases. In the third temperature region a decarbonation and desulfation mainly proceeds displayed by an endothermal effect around 700

oC and beyond. For both series LBFA20 and LBFA30 where arcanite was identified, an endothermal peak at 583-584

oC has been observed due to β to α phase transformation [

72].

The presented thermal data for LBFA series in

Table 3 show decreasing amount of the hydrate component in direction from LBFA0 to LBFA30. However, in the same direction the carbonate component increases and in general, there is an increase in total mass loss with increasing presence of biomass fly ash into the ladle-slag.

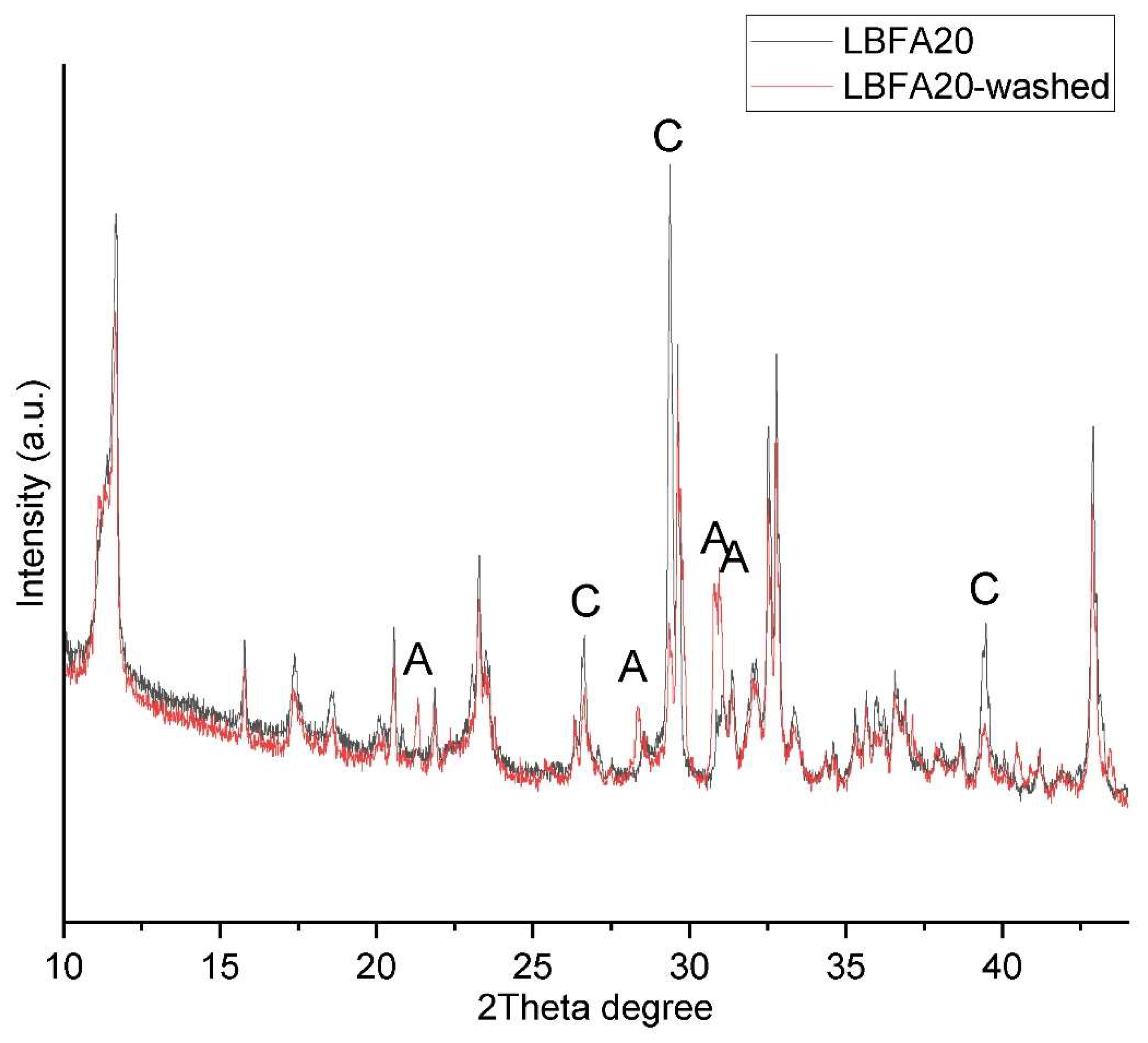

3.3. Leaching Experiments

The leaching behavior of sulfates, chlorides and alkali is a crucial aspect in evaluating the environmental impact and durability of blended cementitious materials. In the ladle slag–biomass fly ash (LBFA) system, the release of sulfate, chloride and potassium ions into a pore solution is governed by phase formation and stability, solubility equilibria, and external exposure conditions. To evaluate the leaching behavior ladle slag–biomass fly ash (LBFA) hardened material sample LBFA20 were grounded to powder and washed several times with distilled water. Washed powder was dried and chemical composition were determined by XRF (

Table 4). The results revealed a significant reduction in sulphur, chlorine, and potassium concentrations, indicating that these elements were not strongly bonded into stable crystalline phases and were instead present in soluble or weakly bound amorphous phases. Only partial amount of chlorine (~26%) and sulfate (~12%) stayed after washing test. Interestingly, potassium bearing phases were not detected at any stage of the analysis, suggesting that potassium was primarily presented in an amourphase phases or at soluble ionic form. X-ray diffraction analysis of the washed sample confirmed that AFm phases in LBFA20 remained stable (

Figure 7). The remaining sulfur and chlorine are likely incorporated into the AFm phases, which play a crucial role in binding chlorides and sulfates, thereby enhancing the material's ability to prevent steel corrosion. [

73] [

74]. However, most of the soluble components in the SSFA does not participate in the formation of any or enough stable phases, thus we can state that the full potential of SSFA were not achieved at current addition levels.

4. Conclusions

This study explored the potential of sunflower shell biomass fly ash (SSFA) as a dry alkali activator for one-part alkali-activated ladle slag binder. The chemical and mineralogical analysis of the precursors revealed that ladle slag (LS) is primarily composed of γ-belite, mayenite, and periclase, while SSFA is rich in potassium-bearing phases such as arcanite and sylvite.

The results showed that addition of SSFA in ladle slag mixtures improved the early hydration processes and contributed to higher compressive strength compared to normal hydration of the ladle slag. The optimum addition of SSFA was 10% where the compressive strength reached 30 MPa, indicating the effectiveness of SSFA as an alternative activator.

The high alkalinity of SSFA facilitated the partial dissolution of the LS phases, leading to the formation of cementitious reaction products. The presence of chorine and sulfur contribute to formation of more AFm phases such as hydrocalumite, Friedel’s salt, hemicarboaluminate and monocarboaluminate, which contributed to higher mechanical strength.

However, most of the soluble components in the SSFA does not participate in the formation of any or enough stable phases, thus we can state that the full potential of SSFA as alkali activator were not achieved at higher proportions of SSFA addition.

By valorizing both industrial and agricultural waste materials, this study supports the development of environmentally friendly cement alternatives, contributing to circular economy principles and sustainable construction practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.; methodology, A.N., V.K., N.P.,L.T., S.V. and R.T.; software, A.N., V.K., N.P.,L.T. and R.T.; validation, A.N., V.K., N.P.,L.T., S.V. and R.T.; formal analysis, A.N., V.K., N.P.,L.T. and R.T.; investigation, A.N., V.K., N.P.,L.T., S.V. and R.T.; resources, A.N.; data curation, A.N., V.K., N.P.,L.T., S.V. and R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N., V.K., N.P.,L.T. and R.T.; writing—review and editing, A.N., S.V. and R.T.; visualization, A.N., V.K., N.P.,L.T. and R.T.; supervision, A.N. and R.T.; project administration, R.T.; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been carried out in the framework of the National Science Program "Critical and strategic raw materials for a green transition and sustainable development", approved by the Resolution of the Council of Ministers № 508/18.07.2024 and funded by the Ministry of Education and Science (MES) of Bulgaria.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The team acknowledge Stomana Industry, S.A, Bulgaria, and Astra Bioplant EOOD company for provision of the raw materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SSFA |

Sunflower shells fly ash |

| LS |

Ladle slag |

References

- Steel Statistical Yearbook 2022. 2022.

- Chen, J.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Z.; Su, W. Application of iron and steel slags in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 844, 157041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baalamurugan, J.; Kumar, V.G.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Balasundar, S.; Venkatraman, B.; Padmapriya, R.; Raja, V.B. Recycling of steel slag aggregates for the development of high density concrete: Alternative & environment-friendly radiation shielding composite. Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 216, 108885. [Google Scholar]

- Raut, S.R.; Saklecha, P.; Kedar, R. Review on ground granulated blast-furnace slag as a supplementary cementitious material. International Journal of Computer Applications 2015, 975, 8887. [Google Scholar]

- Aiban, S.A. Utilization of steel slag aggregate for road bases. Journal of Testing and Evaluation 2006, 34, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Varma, S. A review on utilization of steel slag in hot mix asphalt. International Journal of Pavement Research and Technology 2021, 14, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, C.; Rios, S.; da Fonseca, A.V.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Cristelo, N. Application of the response surface method to optimize alkali activated cements based on low-reactivity ladle furnace slag. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 264, 120271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A.S.; Fanijo, E.O. A review of the influence of steel furnace slag type on the properties of cementitious composites. Applied sciences 2020, 10, 8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, O.; El-Hassan, H.; El-Dieb, A. Ladle slag characteristics and use in mortar and concrete: A comprehensive review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 288, 125584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C. Steel slag—its production, processing, characteristics, and cementitious properties. Journal of materials in civil engineering 2004, 16, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serjun, V.Z.; Mirti, B.; Mladenovi, A. Evaluation of ladle slag as a potential material for building and civil engineering. Mater. Technol 2013, 47, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, H. Cement chemistry. 1997, 16.

- Yan, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Yin, K.; Wang, L.; Pan, T. Enhancement of Hydration Activity and Microstructure Analysis of γ-C2S. Materials 2023, 16, 6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, J.; Yan, P. Influence of initial alkalinity on the hydration of steel slag. Science China Technological Sciences 2012, 55, 3378–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C. Characteristics and cementitious properties of ladle slag fines from steel production. Cement and Concrete Research 2002, 32, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivenko, P.V. Alkaline cements. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Alkaline Cements and Concretes, Kiev, Ukraine, 1994, 1994.

- Provis, J.L. Alkali-activated materials. Cement and concrete research 2018, 114, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-C.; Wang, H.-Y.; Tsai, H.-C. Study on engineering properties of alkali-activated ladle furnace slag geopolymer. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 123, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murri, A.N.; Rickard, W.; Bignozzi, M.; Van Riessen, A. High temperature behaviour of ambient cured alkali-activated materials based on ladle slag. Cement and concrete research 2013, 43, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, E.; Ohenoja, K.; Kinnunen, P.; Illikainen, M. Alkali activation of ladle slag from steel-making process. Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy 2017, 3, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Češnovar, M.; Traven, K.; Horvat, B.; Ducman, V. The potential of ladle slag and electric arc furnace slag use in synthesizing alkali activated materials; the influence of curing on mechanical properties. Materials 2019, 12, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, E.; Ohenoja, K.; Kinnunen, P.; Illikainen, M. Properties and durability of alkali-activated ladle slag. Materials and Structures 2017, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yi, Y. Use of ladle furnace slag containing heavy metals as a binding material in civil engineering. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 705, 135854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti, I.; Ponzoni, C.; Bignozzi, M.C.; Barbieri, L.; Leonelli, C. Incinerator bottom ash and ladle slag for geopolymers preparation. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2014, 5, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passuello, A.; Rodríguez, E.D.; Hirt, E.; Longhi, M.; Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; Kirchheim, A.P. Evaluation of the potential improvement in the environmental footprint of geopolymers using waste-derived activators. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 166, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, E.; Perumal, P.; Luukkonen, T.; Yliniemi, J.; Ohenoja, K.; Kinnunen, P.; Illikainen, M. Opportunities to improve sustainability of alkali-activated materials: A review of side-stream based activators. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 286, 125558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Carrasco, M.; Puertas, F. Waste glass as a precursor in alkaline activation: Chemical process and hydration products. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 139, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchakouté, H.K.; Rüscher, C.H.; Kong, S.; Kamseu, E.; Leonelli, C. Geopolymer binders from metakaolin using sodium waterglass from waste glass and rice husk ash as alternative activators: A comparative study. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 114, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billong, N.; Oti, J.; Kinuthia, J. Using silica fume based activator in sustainable geopolymer binder for building application. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 275, 122177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, J.; Font, A.; Soriano, L.; Akasaki, J.; Tashima, M.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Payá, J. New use of sugar cane straw ash in alkali-activated materials: A silica source for the preparation of the alkaline activator. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 171, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, A.; Nugteren, H.; Rostovsky, I. Optimization of geopolymers based on natural zeolite clinoptilolite by calcination and use of aluminate activators. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 243, 118257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, E.; van Riessen, A.; McLellan, B.; Penna, B.; Kealley, C.; Nikraz, H. Introducing Bayer liquor-derived geopolymers; Kidlington, Oxford, United States: Elsevier: 2017.

- Luukkonen, T.; Abdollahnejad, Z.; Yliniemi, J.; Kinnunen, P.; Illikainen, M. One-part alkali-activated materials: A review. Cement and Concrete Research 2018, 103, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the chemical composition of biomass. Fuel 2010, 89, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peys, A.; Rahier, H.; Pontikes, Y. Potassium-rich biomass ashes as activators in metakaolin-based inorganic polymers. Applied Clay Science 2016, 119, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, A.; Soriano, L.; Tashima, M.M.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Payá, J. One-part eco-cellular concrete for the precast industry: Functional features and life cycle assessment. Journal of cleaner production 2020, 269, 122203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, L.; Font, A.; Tashima, M.M.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Bonifácio, T.; Payá, J. Almond-shell biomass ash (ABA): a greener alternative to the use of commercial alkaline reagents in alkali-activated cement. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 290, 123251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.S.; Abdel-Gawwad, H.; Vásquez-García, S.; Israde-Alcántara, I.; Flores-Ramirez, N.; Rico, J.; Mohammed, M.S. Cleaner production of one-part white geopolymer cement using pre-treated wood biomass ash and diatomite. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 209, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.S.; Gomes, T.C.F.; de Moraes, J.C.B. Novel one-part alkali-activated binder produced with coffee husk ash. Materials Letters 2022, 313, 131733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokare, S.S.; Dunaway, J.D.; Moulton, D.; Rogers, D.; Tree, D.R.; Baxter, L.L. Investigation of ash deposition rates for a suite of biomass fuels and fuel blends. Energy & Fuels 2006, 20, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Vassileva, C.G.; Baxter, D. Trace element concentrations and associations in some biomass ashes. Fuel 2014, 129, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Agwa, I.S.; Heniegal, A.M. Effect of peanut and sunflower shell ash on properties of sustainable high-strength concrete. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 89, 109208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazpanahi, S.; Faraj, R.H. Feasibility study on the use of shell sunflower ash and shell pumpkin ash as supplementary cementitious materials in concrete. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 30, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, A.; Kostov-Kytin, V.; Tarassov, M.; Tsvetanova, L.; Jordanov, N.B.; Karamanova, E.; Rostovsky, I. CHARACTERIZATION OF CEMENT KILN DUST FROM BULGARIAN CEMENT PLANTS. Journal of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy 2025, 60, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Hao, L.; Zhang, S.; Poon, C.S. High-performance belite rich eco-cement synthesized from solid wastes: Raw feed design, sintering temperature optimization, and property analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2023, 199, 107211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Li, Y. The influence of mayenite employed as a functional component on hydration properties of ordinary Portland cement. Materials 2018, 11, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Cordonnier, B.; Zhu, W.; Renard, F.; Jamtveit, B. Effects of confinement on reaction-induced fracturing during hydration of periclase. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2018, 19, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkacheva, A.; Shkerin, S.; Plaksin, S.; Vovkotrub, E.; Bulanin, K.; Kochedykov, V.; Ordinartsev, D.; Gyrdasova, O.; Molchanova, N. Synthesis of dense ceramics of single-phase mayenite (Ca 12 Al 14 O 32) O. Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry 2011, 84, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgnies, M.; Chen, J.; Bouillon, C. Overview about the use of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to study cementitious materials. WIT Trans. Eng. Sci 2013, 77, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Carrasco, L.; Torrens Martín, D.; Morales, L.; Martínez Ramírez, S. Infrared spectroscopy in the analysis of building and construction materials; InTech: 2012.

- Gunasekaran, S.; Anbalagan, G.; Pandi, S. Raman and infrared spectra of carbonates of calcite structure. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy: An International Journal for Original Work in all Aspects of Raman Spectroscopy, Including Higher Order Processes, and also Brillouin and Rayleigh Scattering 2006, 37, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braterman, P.S.; Cygan, R.T. Vibrational spectroscopy of brucite: A molecular simulation investigation. American Mineralogist 2006, 91, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Chukanov, N.V. The Application of IR Spectroscopy to the Investigation of Minerals. Infrared spectra of mineral species: Extended library.

- Schutte, C.; Buijs, K. The infra-red spectra of K2CO3 and its hydrates. Spectrochimica Acta 1961, 17, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoronkwo, M.U.; Glasser, F.P. Stability of strätlingite in the CASH system. Materials and Structures 2016, 49, 4305–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwinek, E.; Madej, D. Structure, microstructure and thermal stability characterizations of C 3 AH 6 synthesized from different precursors through hydration. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2020, 139, 1693–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, T.; Fang, H.; Li, S.; Yao, Y.; He, Y. A novel preparation of nano-sized hexagonal Mg (OH) 2. Procedia Engineering 2015, 102, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzevari, M.; Sajjadi, S.A.; Moloodi, A. Physical and mechanical properties of porous copper nanocomposite produced by powder metallurgy. Advanced Powder Technology 2016, 27, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the behaviour of biomass during combustion: Part I. Phase-mineral transformations of organic and inorganic matter. Fuel 2013, 112, 391–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broström, M.; Enestam, S.; Backman, R.; Mäkelä, K. Condensation in the KCl–NaCl system. Fuel Processing Technology 2013, 105, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschei, T.; Lothenbach, B.; Glasser, F. The AFm phase in Portland cement. Cement and concrete research 2007, 37, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.K.; Serra-Maia, R.; Shi, Y.; Psarras, P.; Vojvodic, A.; Stach, E.A. Enhanced mineral carbonation on surface functionalized MgO as a Proxy for mine tailings. Environmental Science: Nano.

- Khan, M.; Kayali, O.; Troitzsch, U. Chloride binding capacity of hydrotalcite and the competition with carbonates in ground granulated blast furnace slag concrete. Materials and Structures 2016, 49, 4609–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damidot, D.; Glasser, F. Thermodynamic investigation of the CaO—Al2O3—CaSO4—CaCO3-H2O closed system at 25 C and the influence of Na2O. Advances in cement research 1995, 7, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damidot, D.; Glasser, F. Investigation of the CaO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O system at 25 C by thermodynamic calculations. Cement and Concrete Research 1995, 25, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, R.A. Magnesia refractories. Mechanical Engineering-New York and Basel-Marcel Dekker Then Crc Press/Taylor and Francis 2004, 178, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.J.; Musso, S.; Prestini, I. Kinetics and activation energy of magnesium oxide hydration. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2014, 97, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, D. Hydration, carbonation and thermal stability of hydrates in Ca 7− x Sr x ZrAl 6 O 18 cement. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2018, 131, 2411–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkova, V.; Stoyanov, V.; Pelovski, Y. TG–DTG–DTA in studying white self-compacting cement mortars. Journal of thermal analysis and calorimetry 2012, 109, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, E.; Walenta, G.; Morin, V.; Termkhajornkit, P.; Baco, I.; Casabonne, J. Hydration of a belite-calciumsulfoaluminate-ferrite cement: AetherTM. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th international Congress on the Chemistry of Cement, Madrid, Spain; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Birnin-Yauri, U.; Glasser, F. Friedel’s salt, Ca2Al (OH) 6 (Cl, OH)· 2H2O: its solid solutions and their role in chloride binding. Cement and Concrete Research 1998, 28, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; Liu, H.; Jin, H.; Chen, H.; Su, K.; Tu, Y.; Wang, W. Thermochemical behavior of three sulfates (CaSO4, K2SO4 and Na2SO4) blended with cement raw materials (CaO-SiO2-Al2O3-Fe2O3) at high temperature. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2019, 142, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Tan, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Liang, W.; Hong, J. Chloride binding of AFm in the presence of Na+, Ca2+ and Ba2+. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 364, 129804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.; Yoon, S.; Oh, J.E. A comparison study for chloride-binding capacity between alkali-activated fly ash and slag in the use of seawater. Applied sciences 2017, 7, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Powder XRD of the raw materials: biomass fly ash from sunflower shells (SSFA), and ladle slag (LS). Legend: A – arcanite, a – strätlingite, B – brucite, C – calcite, G – gehlenite, K – katoite; Pc – potassium carbonate hydrate (K2CO3.1.5H2O), P – periclase, Q – quartz, M – mayenite, S – sylvite, γ – γ-belite (Ca2SiO4).

Figure 1.

Powder XRD of the raw materials: biomass fly ash from sunflower shells (SSFA), and ladle slag (LS). Legend: A – arcanite, a – strätlingite, B – brucite, C – calcite, G – gehlenite, K – katoite; Pc – potassium carbonate hydrate (K2CO3.1.5H2O), P – periclase, Q – quartz, M – mayenite, S – sylvite, γ – γ-belite (Ca2SiO4).

Figure 2.

Infrared spectra of the raw materials: biomass fly ash from sunflower shells (SSFA), and ladle slag (LS).

Figure 2.

Infrared spectra of the raw materials: biomass fly ash from sunflower shells (SSFA), and ladle slag (LS).

Figure 3.

Figure 3. DSC-TG(DTG) curves of both precursors - LS and SSFA.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. DSC-TG(DTG) curves of both precursors - LS and SSFA.

Figure 4.

Powder XRD of the alkali activated material based on ladle slag and biomass ash from sunflower shells. Legend: A – arcanite, a – strätlingite, AFm - family of hydrated calcium aluminate phases, C – calcite, Fr – Friedel’s salt, Ha – hydrocalumite, Hc – hemicarboaluminate, Mc – monocarboaluminate, K – katoite, M – mayenite, P – periclase, Q – quartz, S – sylvite, γ – γ-belite (dicalcium silicate).

Figure 4.

Powder XRD of the alkali activated material based on ladle slag and biomass ash from sunflower shells. Legend: A – arcanite, a – strätlingite, AFm - family of hydrated calcium aluminate phases, C – calcite, Fr – Friedel’s salt, Ha – hydrocalumite, Hc – hemicarboaluminate, Mc – monocarboaluminate, K – katoite, M – mayenite, P – periclase, Q – quartz, S – sylvite, γ – γ-belite (dicalcium silicate).

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of the alkali activated material (LBFA) based on ladle slag (LS) and biomass ash from sunflower shells (SSFA).

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of the alkali activated material (LBFA) based on ladle slag (LS) and biomass ash from sunflower shells (SSFA).

Figure 6.

DSC-TG(DTG) curves of LBFA0, LBFA10, LBFA20 and LBFA30.

Figure 6.

DSC-TG(DTG) curves of LBFA0, LBFA10, LBFA20 and LBFA30.

Figure 7.

Powder XRD diffraction of series LBFA20 before and after washing experiments. Legend showing the difference phases: A – Arcanite, C - calcite.

Figure 7.

Powder XRD diffraction of series LBFA20 before and after washing experiments. Legend showing the difference phases: A – Arcanite, C - calcite.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of ladle slag (LS) and biomass fly as from sunflower shells (SSFA), determined by XRF, in wt%.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of ladle slag (LS) and biomass fly as from sunflower shells (SSFA), determined by XRF, in wt%.

| |

Na2O |

MgO |

Al2O3

|

SiO2

|

SO3

|

Cl |

K2O |

CaO |

TiO2

|

MnO |

Fe2O3

|

Others |

| Ladle slag |

- |

6.50 |

15.50 |

15.60 |

2.45 |

- |

0.10 |

55.50 |

0.70 |

0.80 |

2.69 |

0.16 |

| SSFA |

0.03 |

2.33 |

0.04 |

0.22 |

14.02 |

4.78 |

61.34 |

15.43 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.12 |

- |

Table 2.

Composition design and physical properties of the prepared pastes.

Table 2.

Composition design and physical properties of the prepared pastes.

| Series |

LS |

SSFA |

Water to solid |

Compressive strength, MPa |

Density, g/cm3

|

|

| LBFA0 |

100 |

0 |

0.35 |

9.5 ± 0.5 |

1.591± 0.006 |

|

| LBFA10 |

90 |

10 |

0.35 |

29.6 ± 0.2 |

1.569± 0.001 |

|

| LBFA20 |

80 |

20 |

0.35 |

22.4 ± 0.3 |

1.560± 0.002 |

|

| LBFA30 |

70 |

30 |

0.35 |

11.6 ± 0.2 |

1.548± 0.004 |

|

Table 3.

Mass loss during dehydration-dehydroxylation and decarbonation processes.

Table 3.

Mass loss during dehydration-dehydroxylation and decarbonation processes.

| Series |

(I) Dehydration-(II)dehydroxylation, mass %, (process-related new phases)

|

(III)Decarbonization,

mass % (process-related new phase)

|

Total loss, mass % |

| LBFA0 |

15.8

(strätlingite, katoite)

|

3.4

(hemi-, monocarboaluminate, calcite)

|

19.2 |

| LBFA10 |

13.8

(AFm)

|

7.4

(hemi-, monocarboaluminate, calcite) |

21.2 |

| LBFA20 |

13.5

(AFm)

|

7.5

(hemi-, monocarboaluminate, calcite)

|

21.0 |

| LBFA30 |

13.4

(AFm)

|

7.6

(hemi-, monocarboaluminate, calcite)

|

21.0 |

Table 4.

Leaching of sulfates and chlorides after washing with water.

Table 4.

Leaching of sulfates and chlorides after washing with water.

| |

MgO |

Al2O3

|

SiO2

|

SO3

|

Cl |

K2O |

CaO |

TiO2

|

MnO |

Fe2O3

|

Others |

| LBFA20 |

5.67 |

10.9 |

9.28 |

5.91 |

0.983 |

13.4 |

48.6 |

0.654 |

0.868 |

2.84 |

0.895 |

| LBFA20-washed |

6.97 |

11.0 |

11.8 |

0.692 |

0.254 |

1.93 |

60.3 |

0.912 |

1.22 |

3.78 |

1.142 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).