Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of Raw Materials

| %10 W3S + % 90 brick clay |

% 30 W3S + % 70 brick clay |

% 50 W3S + % 50 brick clay |

%100 W3S |

Brick clay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuvars, SiO2 Calcite, CaCO3 Feldspar İllite (K,H3O)Al2Si3AlO10(OH)2 Montmorillonite CaO2(Al,Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2. 4H2O Kristobalite, SiO2 Almandine, Fe3Al2(SiO4)3 |

Kuvars, SiO2 Calcite, CaCO3 Feldspar İllite (K,H3O)Al2Si3AlO10(OH)2 Montmorillonite CaO2(Al,Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2. 4H2O Kristobalite, SiO2 Almandine, Fe3Al2(SiO4)3 |

Kuvars, SiO2 Calcite, CaCO3 Feldspar İllite( K,H3O)Al2Si3AlO10(OH)2 Montmorillonite CaO2(Al,Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2. 4H2O Kristobalite, SiO2 Almandine, Fe3Al2(SiO4)3 |

Kaolinite (Al2Si2O5(OH)4 Kuvars (SiO2) Hematit (Fe2O3) |

Kuvars (SiO2) Calcite (CaCO3) İllite (K1H3O)Al2Si3AlO10(OH)2 Clinochlorine (Mg,Fe)6(Si,Al)4O10(OH)8 Feldspar Jips (CaSO4.2H2O) |

| %10 W3S + % 90 brick clay |

%30 W3S + % 70 brick clay |

%50 W3S + % 50 brick clay |

%100 W3S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Quantity (%) | Quantity (%) | Quantity (%) | Quantity (%) |

| SiO2 | 42,905 | 46,497 | 49,985 | 59,452 |

| Al2O3 | 16,462 | 17,789 | 19,351 | 26,956 |

| Fe2O3 | 7,252 | 6,706 | 5,922 | 4,086 |

| TiO2 | 0,785 | 0,748 | 0,685 | 0,593 |

| CaO | 11,915 | 9,797 | 7,462 | 0,110 |

| MgO | 3,960 | 3,244 | 2,666 | 0,396 |

| Na2O | 0,801 | 0,710 | 0,526 | 0,039 |

| K2O | 1,937 | 1,661 | 1,421 | 0,501 |

| SO3 | 0,702 | 0,706 | 0,597 | 0,000 |

| P2O5 | 0,161 | 0,147 | 0,134 | 0,107 |

| MnO2 | 0,116 | 0,080 | 0,063 | 0,015 |

| Cr2O3 | 0,025 | 0,036 | 0,030 | 0,035 |

| Loss of ignition | 12,740 | 11,680 | 10,990 | 7,590 |

| Total | 99,763 | 99,803 | 99,833 | 99,880 |

3. Results and Discussion

| 25 BAR 1/05 |

800°C | 850°C | 900°C |

|---|---|---|---|

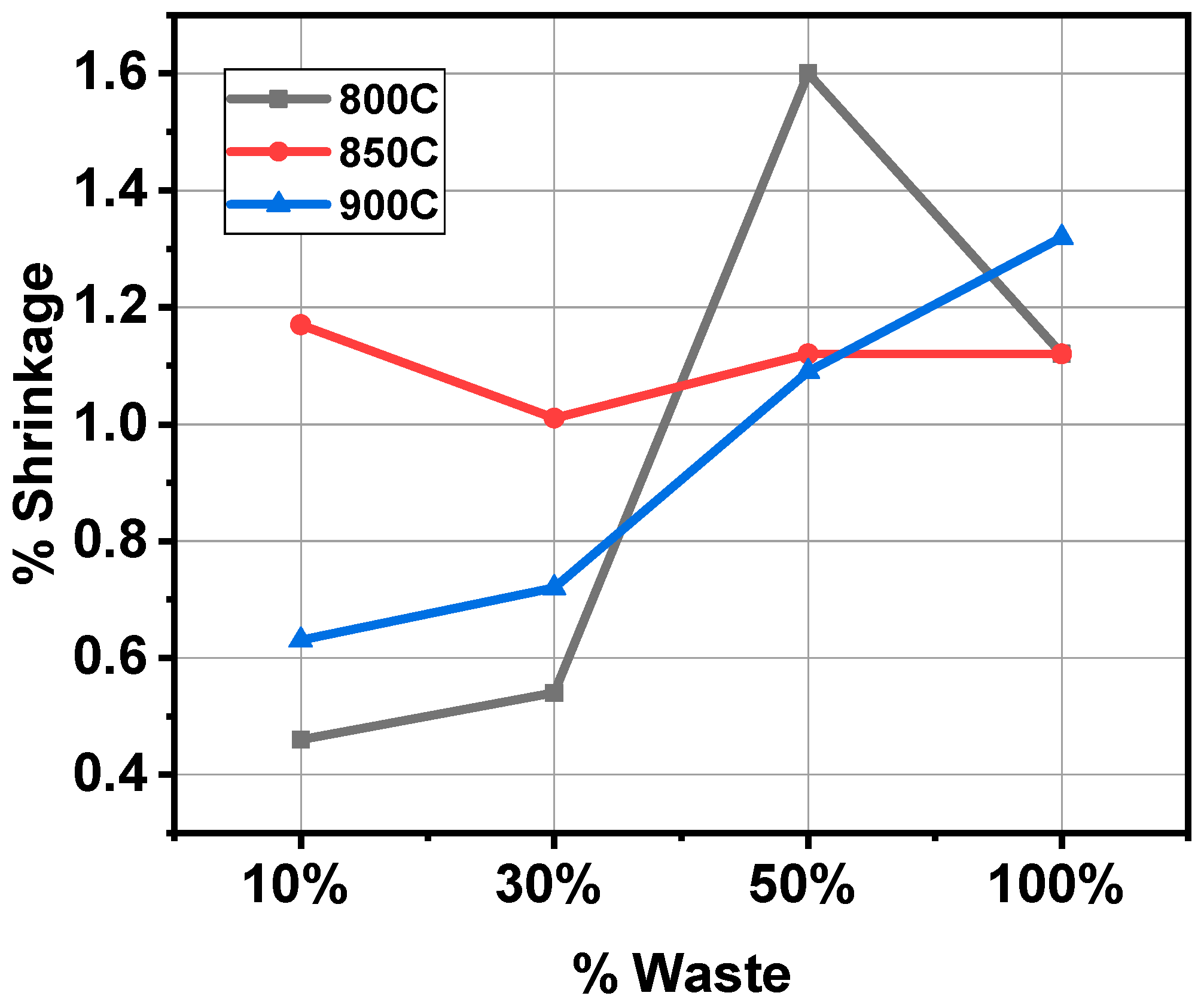

| Total shrinkage, % | 0,46 | 1,17 | 0,63 |

| Total weight loss, % | 12,60 | 13,62 | 13,70 |

| Compression strength, N/mm2 | 114,061 | 115,940 | 138,992 |

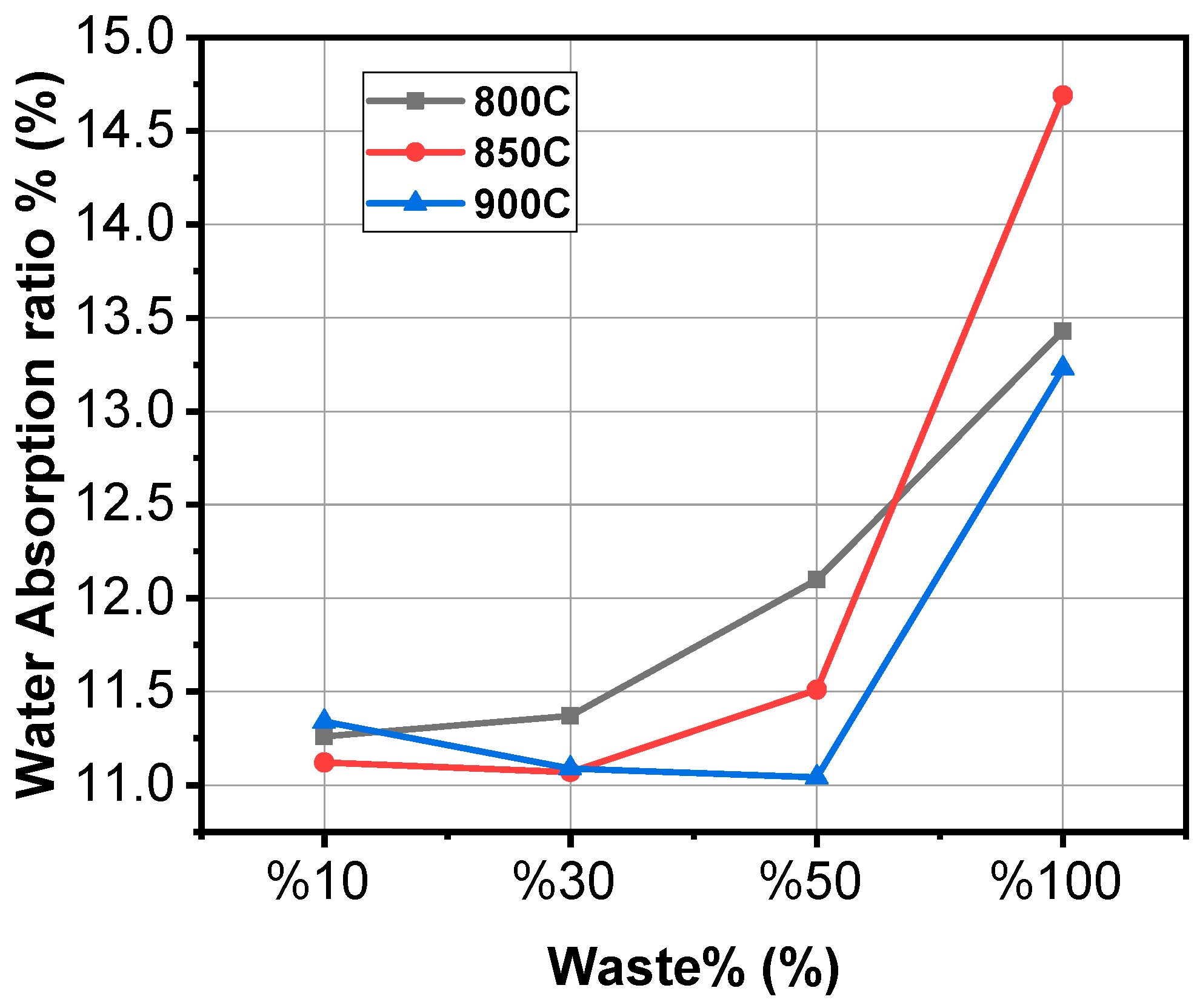

| Water absorption ratio, % | 11,26 | 11,12 | 11,34 |

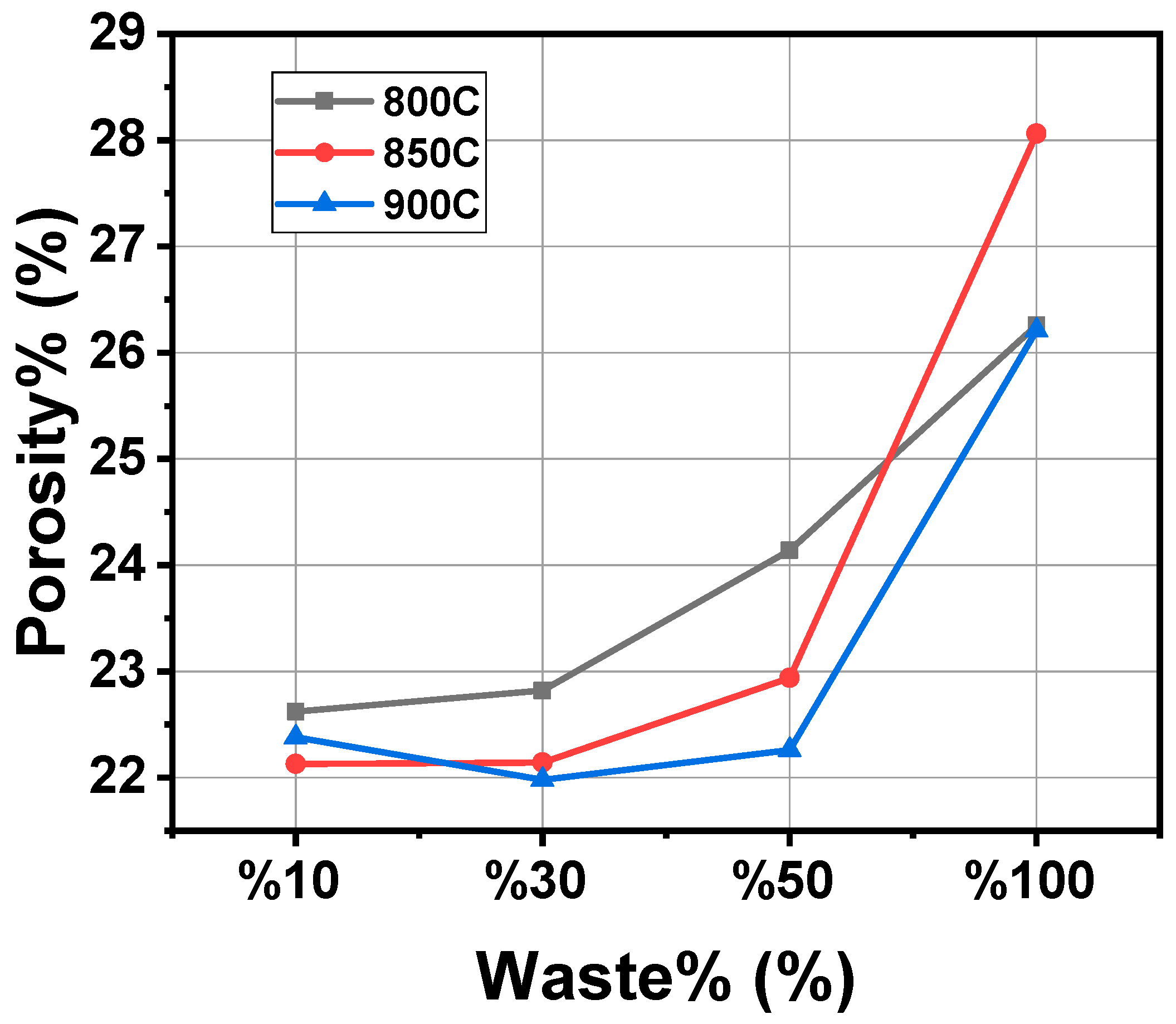

| Porosity, % | 22,62 | 22,13 | 22,38 |

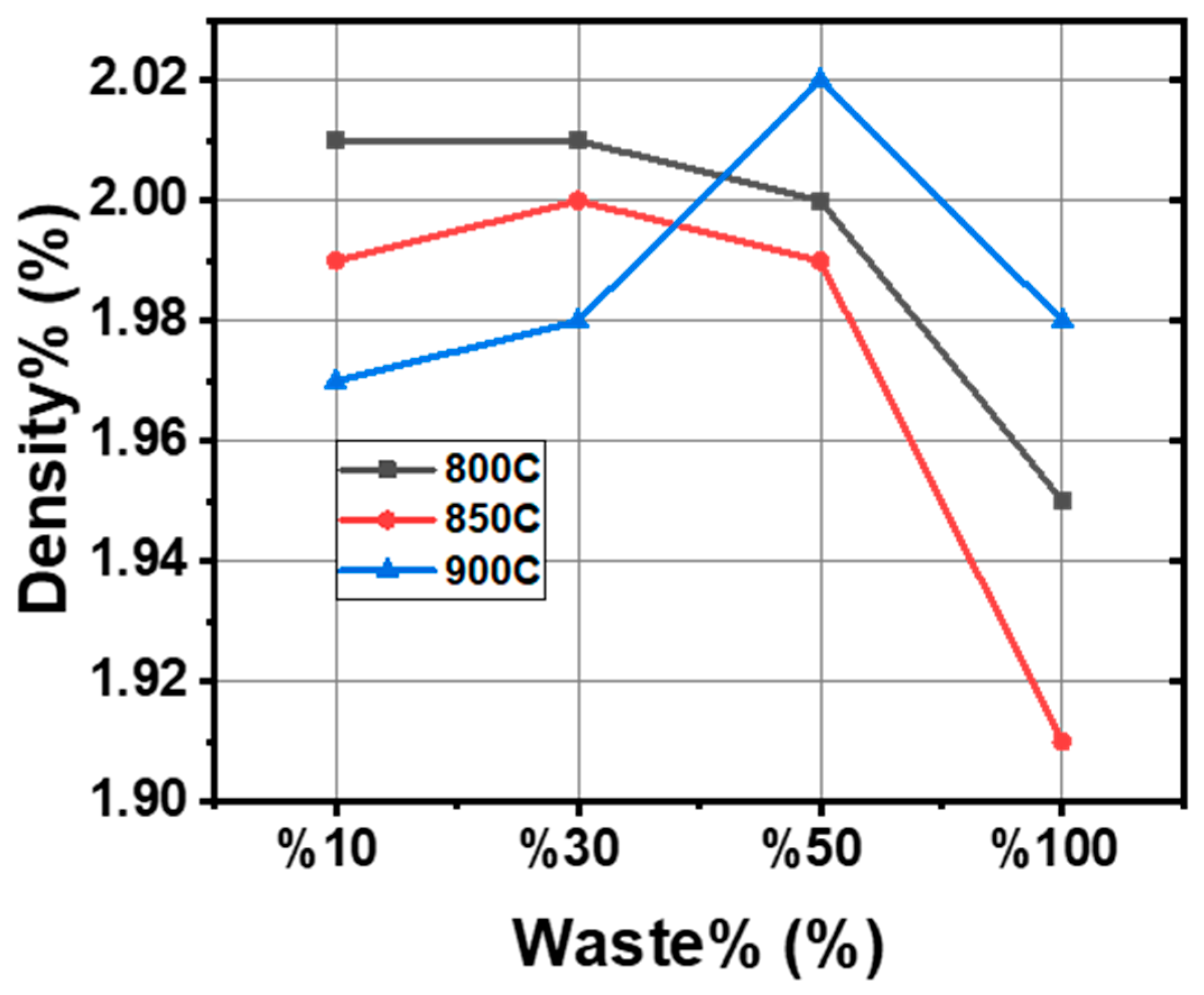

| Density | 2,01 | 1,99 | 1,97 |

| 25 BAR 1/05 |

800°C | 850°C | 900°C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total shrinkage, % | 0,54 | 1,01 | 0,72 |

| Total weight loss, % | 11,77 | 12,36 | 12,43 |

| Compression strength, N/mm2 | 113,756 | 121,949 | 109,083 |

| Water absorption ratio, % | 11,37 | 11,07 | 11,09 |

| Porosity, % | 22,82 | 22,14 | 21,98 |

| Density | 2,01 | 2,00 | 1,98 |

| 25 BAR 1/05 |

800°C | 850°C | 900°C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total shrinkage, % | 1,60 | 1,12 | 1,09 |

| Total weight loss, % | 10,88 | 11,29 | 11,34 |

| Compression strength, N/mm2 | 115,203 | 126,924 | 122,038 |

| Water absorption ratio, % | 12,10 | 11,51 | 11,04 |

| Porosity, % | 24,14 | 22,94 | 22,26 |

| Density | 2,00 | 1,99 | 2,02 |

| 25 BAR 1/05 |

800°C | 850°C | 900°C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total shrinkage, % | 1,12 | 1,12 | 1,32 |

| Total weight loss, % | 8,15 | 8,56 | 8,69 |

| Compression strength, N/mm2 | 125,579 | 105,969 | 134,400 |

| Water absorption ratio, % | 13,43 | 14,69 | 13,23 |

| Porosity, % | 26,26 | 28,06 | 26,21 |

| Density | 1,95 | 1,91 | 1,98 |

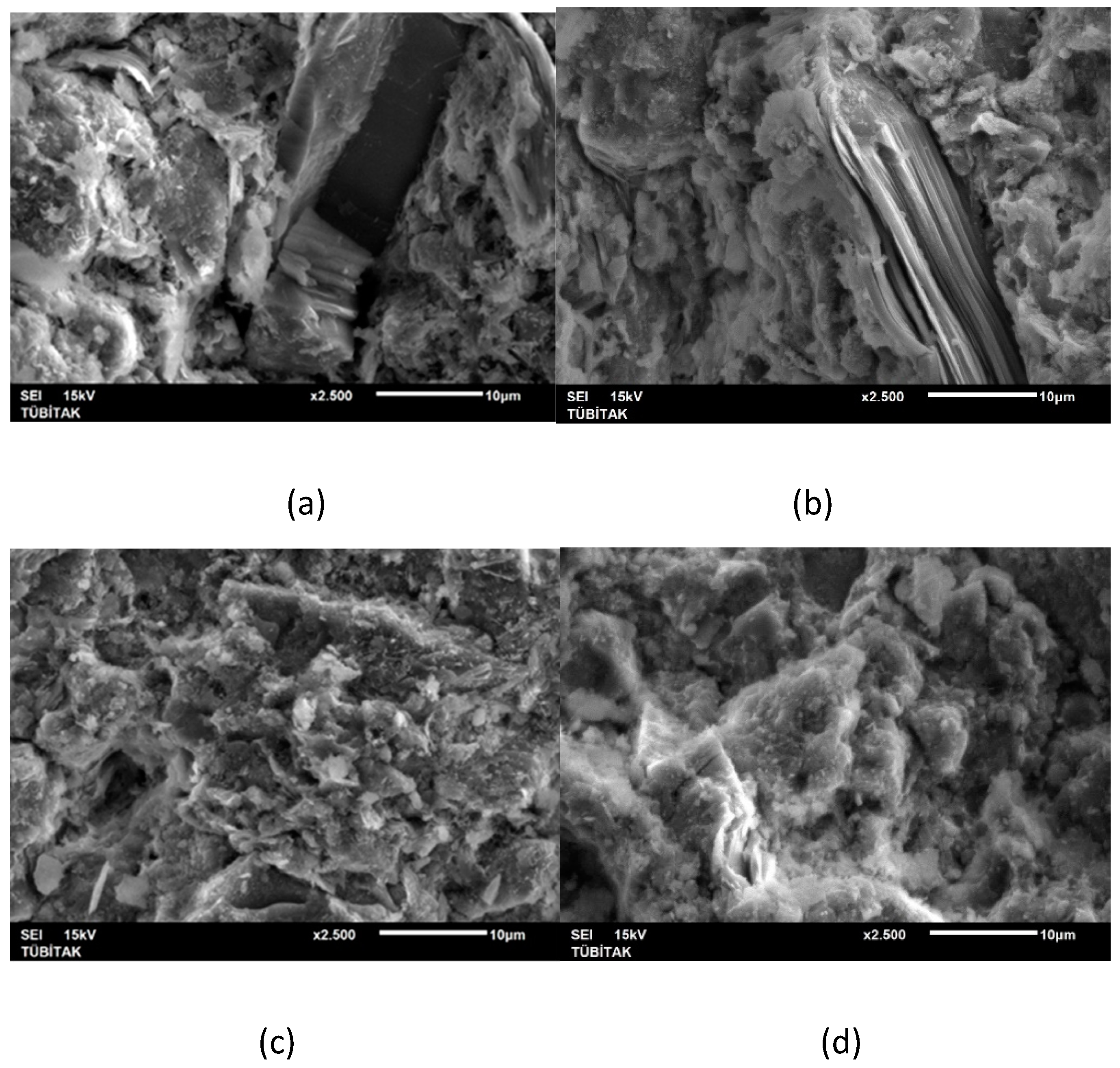

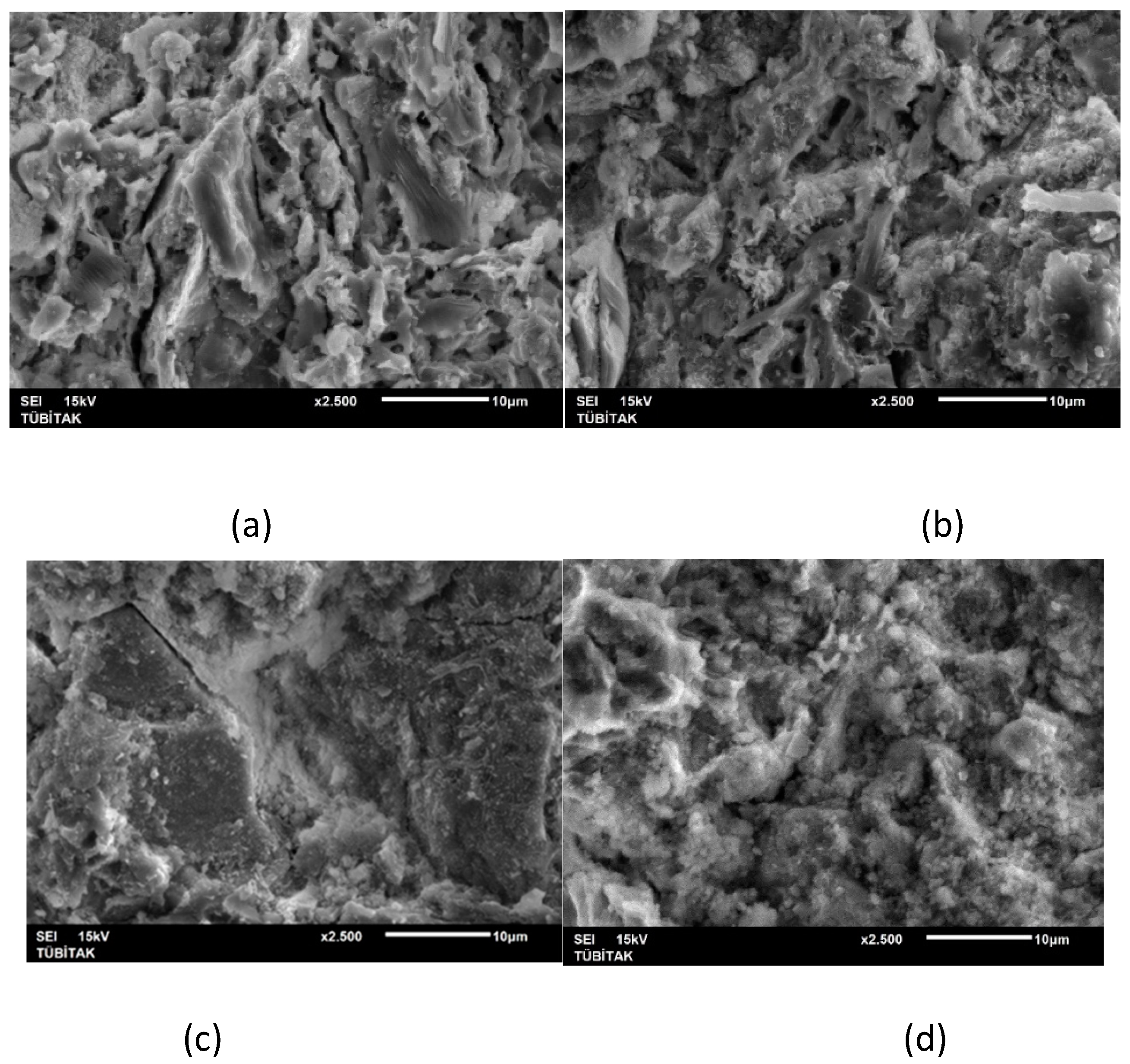

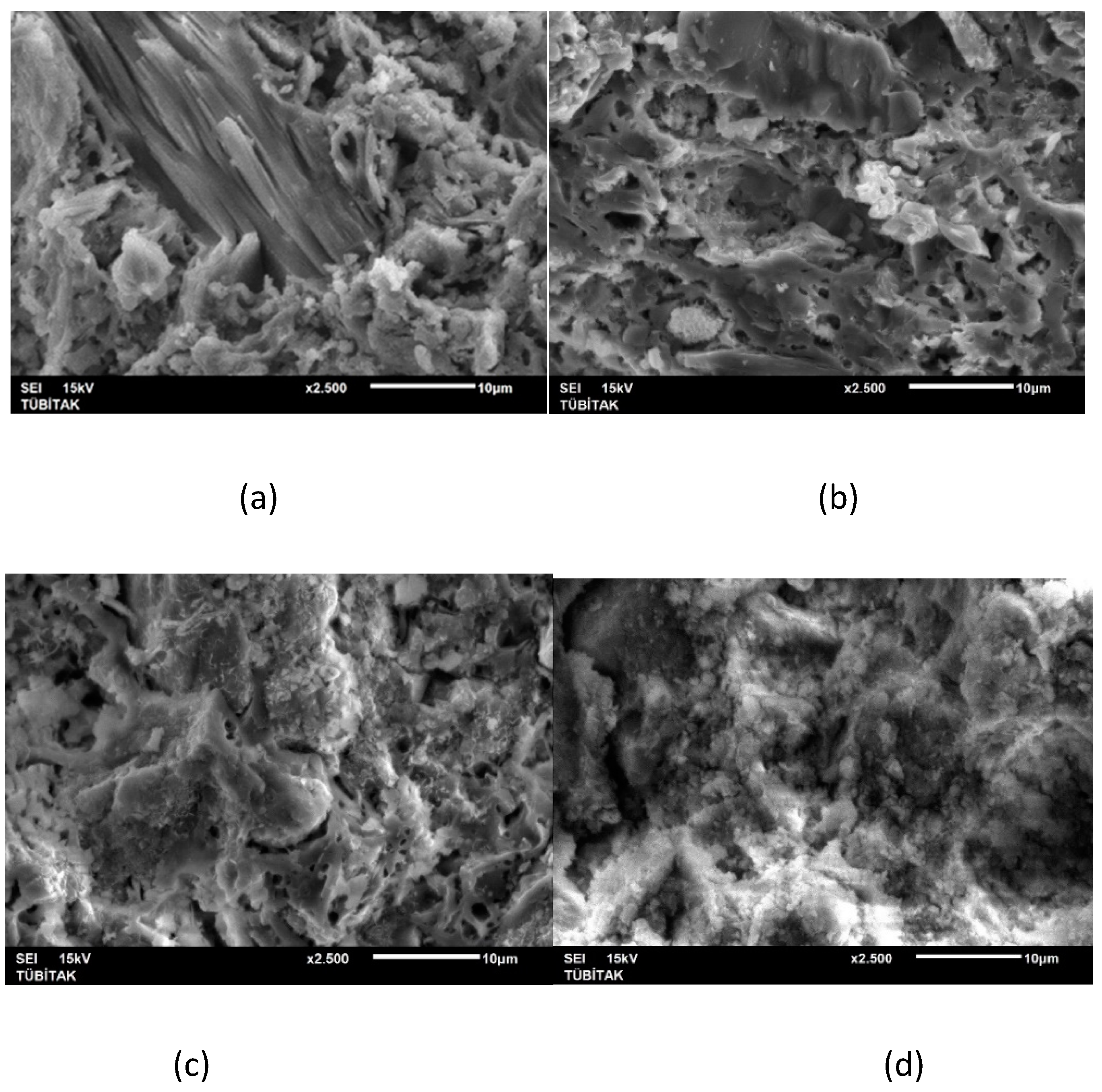

3.1. Microstructural Analyses

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Wang, S.; Gainey, L.; Mackinnon, I.D.R.; Allen, C.; Gu, Y.; Xi, Y. Thermal behaviors of clay minerals as key components and additives for fired brick properties: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiglstorfer, H.; Ottner, F. The impact of clay minerals on the building technology of vernacular earthen architecture in Eastern Austria. Heritage 2022, 5(1), 378–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Mora, R.; Chaparro, A.; Sánchez-Molina, J. Physicochemical and mineralogical properties of clays used in ceramic industry at North East Colombia. Dyna 2019, 86(209), 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario, M. Advancing sustainable construction: insights into clay-based additive manufacturing for architecture, engineering, and construction. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Akintola, G. Mechanical evaluation of soil and artisanal bricks for quality masonry product management, Limpopo, South Africa. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14 (1). [CrossRef]

- Sufian, M.; Ullah, S.; Ostrowski, K.; Ahmad, A.; Zia, A.; Śliwa-Wieczorek, K.; Awan, A. An experimental and empirical study on the use of waste marble powder in construction material. Materials 2021, 14(14), 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pr, F. Synthesis and characterization of clay brick using waste groundnut shell ash. J. Waste Resour. Recycl. 2019, 1(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissy, P.; Peter, C.; Mohan, K.; Greens, S.; George, S. Energy efficient production of clay bricks using industrial waste. Heliyon 2018, 4(10), e00891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, N.; Bhat, L.; Ghale, D.; Duwal, N.; Bhattarai, J. Investigation of the firing temperature effects on clay brick sample; Part-I: mineralogical phase characterization. Bibechana 2018, 16, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, I.; Saıd, S.; Hisham, B.; Bakar, A.; Ahmad, Z. Effect of the change of firing temperature on microstructure and physical properties of clay bricks from Beruas (Malaysia). Sci. Sinter. 2010, 42(2), 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, D.; Paudel, M.R. Quality assessment of bricks produced in Chitwan District, Central Nepal. J. Nepal Geol. Soc. 2023, 65 (Sp. Issue), 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklehaimanot, M.; Hailay, H.; Tesfaye, T. Manufacturing of ecofriendly bricks using microdust cotton waste. J. Eng. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, S.; Ralegaonkar, R.; Mandavgane, S. Development of sustainable construction material using industrial and agricultural solid waste: a review of waste-create bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25(10), 4037–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, I. Production and characterization of bricks from bottom ash and textile sludge using plastic waste as binding agent. J. Eng. 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.; Lee, Y.; Amran, M.; Fediuk, R.; Vatin, N.; Kueh, A.; Lee, Y. A sustainable reuse of agro-industrial wastes into green cement bricks. Materials 2022, 15(5), 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ongpeng, J.; Inciong, E.; Sendo, V.; Soliman, C.; Siggaoat, A. Using waste in producing bio-composite mycelium bricks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10(15), 5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Srivastava, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, H.; Kumar, A.; Singh, G. Utilization of plastic waste for developing composite bricks and enhancing mechanical properties: a review on challenges and opportunities. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.; Lin, D.; Chiang, P. Utilization of sludge as brick materials. Adv. Environ. Res. 2003, 7(3), 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, H. Lightweight bricks manufactured from ground soil, textile sludge, and coal ash. Environ. Technol. 2017, 39(11), 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, E.; Avşar, E.; Toröz, İ. Otomotiv Endüstrisi Kimyasal Arıtma Çamurlarının Tuğla Üretiminde Kullanılabilirliğinin Ürün Kalitesi Yönünden Araştırılması. TÜRKAY 2009, Türkiye’de Katı Atık Yönetimi Sempozyumu, Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi, İstanbul, 2009.

- Adiyanto, O.; Mohamad, E.; Razak, J. Systematic review of plastic waste as eco-friendly aggregate for sustainable construction. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubbar, A.; Sadique, M.; Kot, P.; Atherton, W. Future of clay-based construction materials – a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 210, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeyemi, S. Determining the Properties of Unfired Stabilized Kaolinitic Clay Brick for Sustainable Construction. Key Eng. Mater. 2024, 981, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariq, O. Development of Geothermal Sludge Derived-Silica Catalyst for Sago Starch Hydrolysis. Key Eng. Mater. 2024, 6, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhadi, E. Preparation of Sulfonated SiO2 Catalyst from Geothermal Sludge Waste for Sago Flour Hydrolysis. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 138, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiatama, A.; Susanti, R.; Astuti, W.; Petrus, H.; Wanta, K. Synthesis and Characteristic of Nanosilica from Geothermal Sludge: Effect of Surfactant. Metalurgi 2022, 37(2), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, A.; Guner, A. Use of Silica Fume, Bentonite, and Waste Tire Rubber as Impermeable Layer Construction Materials. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuok, C. H.; Dianbudiyanto, W.; Liu, S. H. A Simple Method to Valorize Silica Sludges into Sustainable Coatings for Indoor Humidity Buffering. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2022, 32, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judith, J. V.; Vasudevan, N. Synthesis of Nanomaterial from Industrial Waste and Its Application in Environmental Pollutant Remediation. Environ. Eng. Res. 2022, 27(2), 200672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A. D.; Juzsakova, T.; Le, P. C.; et al. Preparation, Characterization, and Application of Nano-Silica from Agricultural Wastes in Cement Mortar. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 9411–9421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, M.; Hamed, A.; Ali, F.; Khim, O. Properties and Performance of Water Treatment Sludge (WTS)-Clay Bricks. J. Teknol. 2015, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H. Review of Solid Waste Resource Utilization for Brick-Making. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 520, 02006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewemoje, O.; Bademosi, T. Development of a Sludge Dewatering Filter and Utilization of Dried Sludge in Brick Making. Fuoye J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, J. Z. Influence of Sludge Content on Compressive Strength of Sintering Sludge-Shale Bricks. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 238, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.; Abbas, S.; Abbass, W.; Salmi, A.; Ahmed, A.; Saeed, D.; et al. Potential Use of Wastewater Treatment Plant Sludge in Fabrication of Burnt Clay Bricks. Sustainability 2022, 14(11), 6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiao, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Effect of Sewage Sludge Addition on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Kaolin-Sewage Sludge Ceramic Bricks. Coatings 2022, 12(7), 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).