Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Mining Site

Materials and Methods

Materials Used

Mix Proportioning

Mixes Preparation Protocol

Experimental Methods

Material Characterization

- X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for bulk chemical composition;

- Loss on ignition (LOI) to assess volatile content;

- Particle size distribution (PSD) to determine granulometry.

- Phase identification and structural information were obtained through:

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Bruker D2 diffractometer equipped with a Cu-Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å);

- Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) performed with a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS20 instrument.

Mechanical Testing

Water Absorption

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Chemical and Environmental Analysis

Durability Assessment

Experimental Protocol

Results and Discussion

Raw materials Characterization

Physical Characterization

Mineralogical Characterization

Raw Materials

Effect of Thermal Treatment on Raw Materials

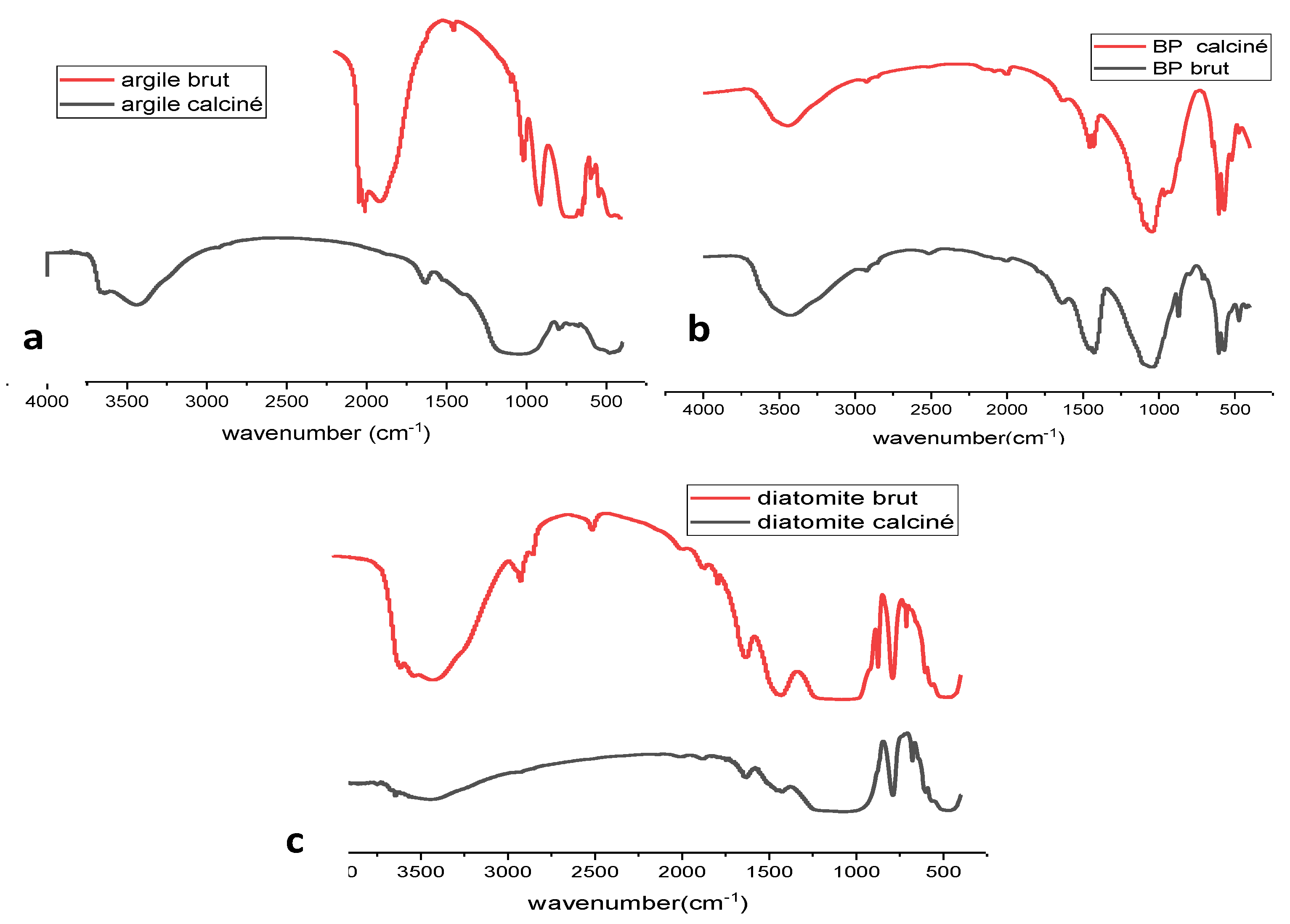

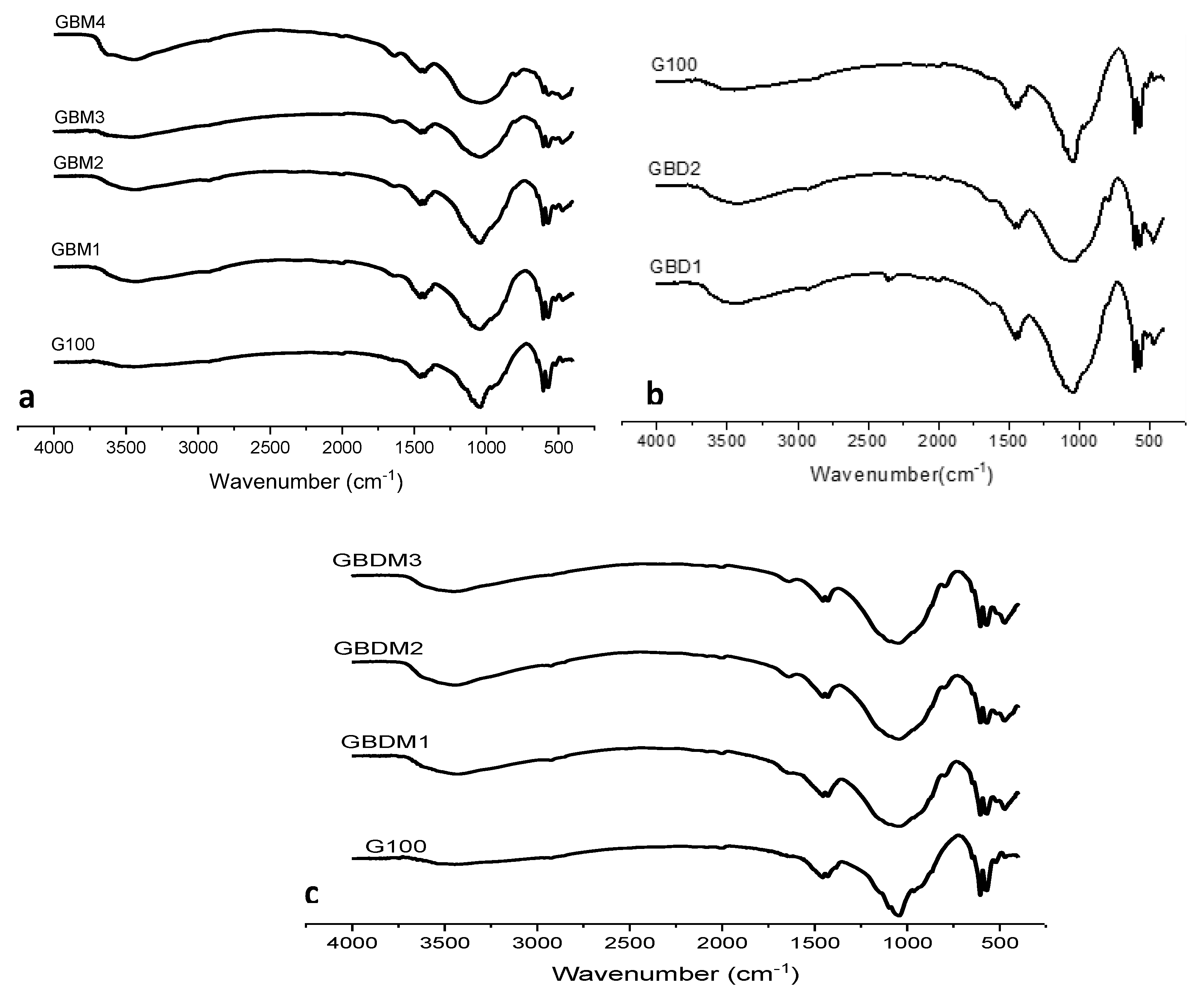

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

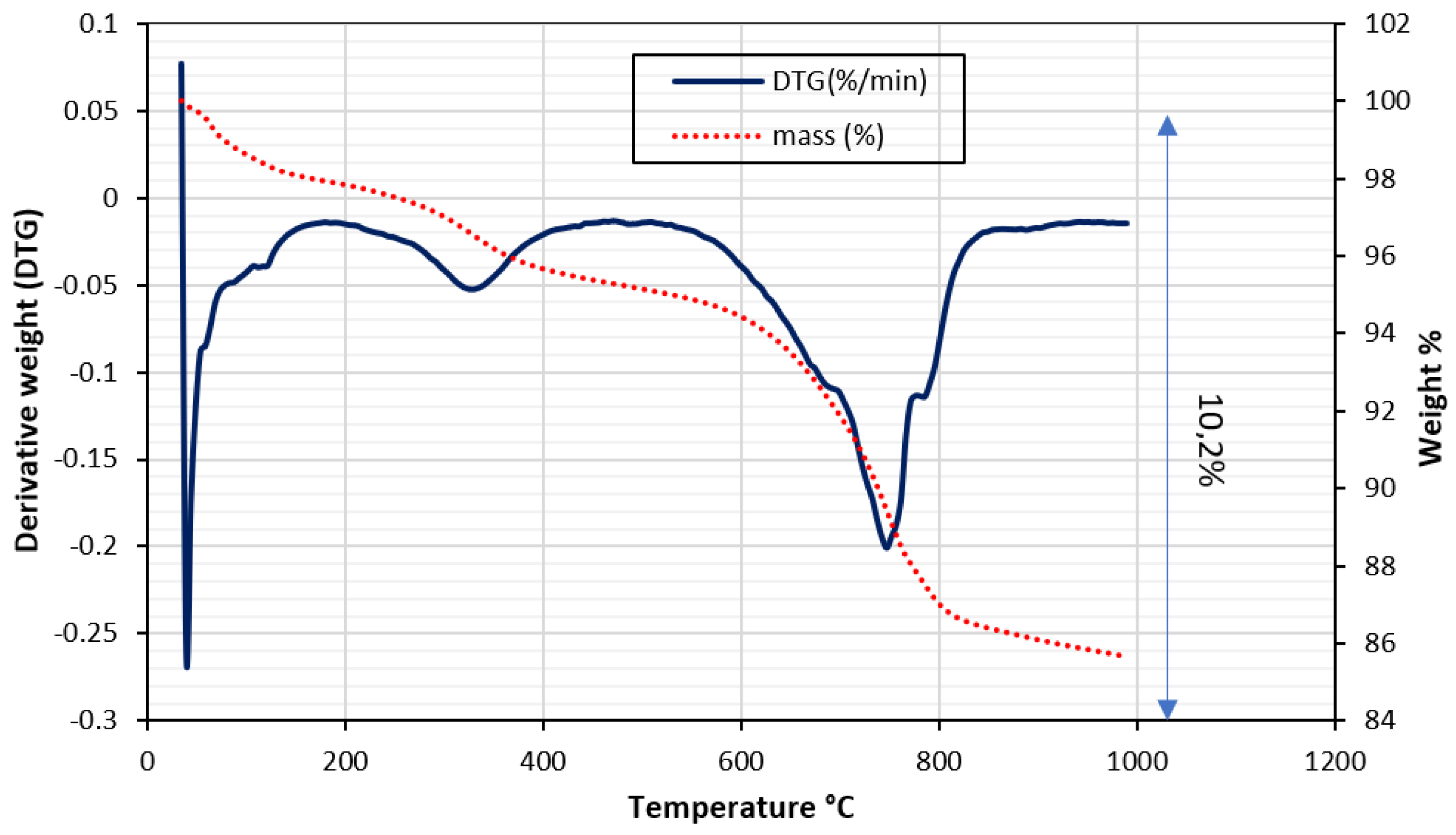

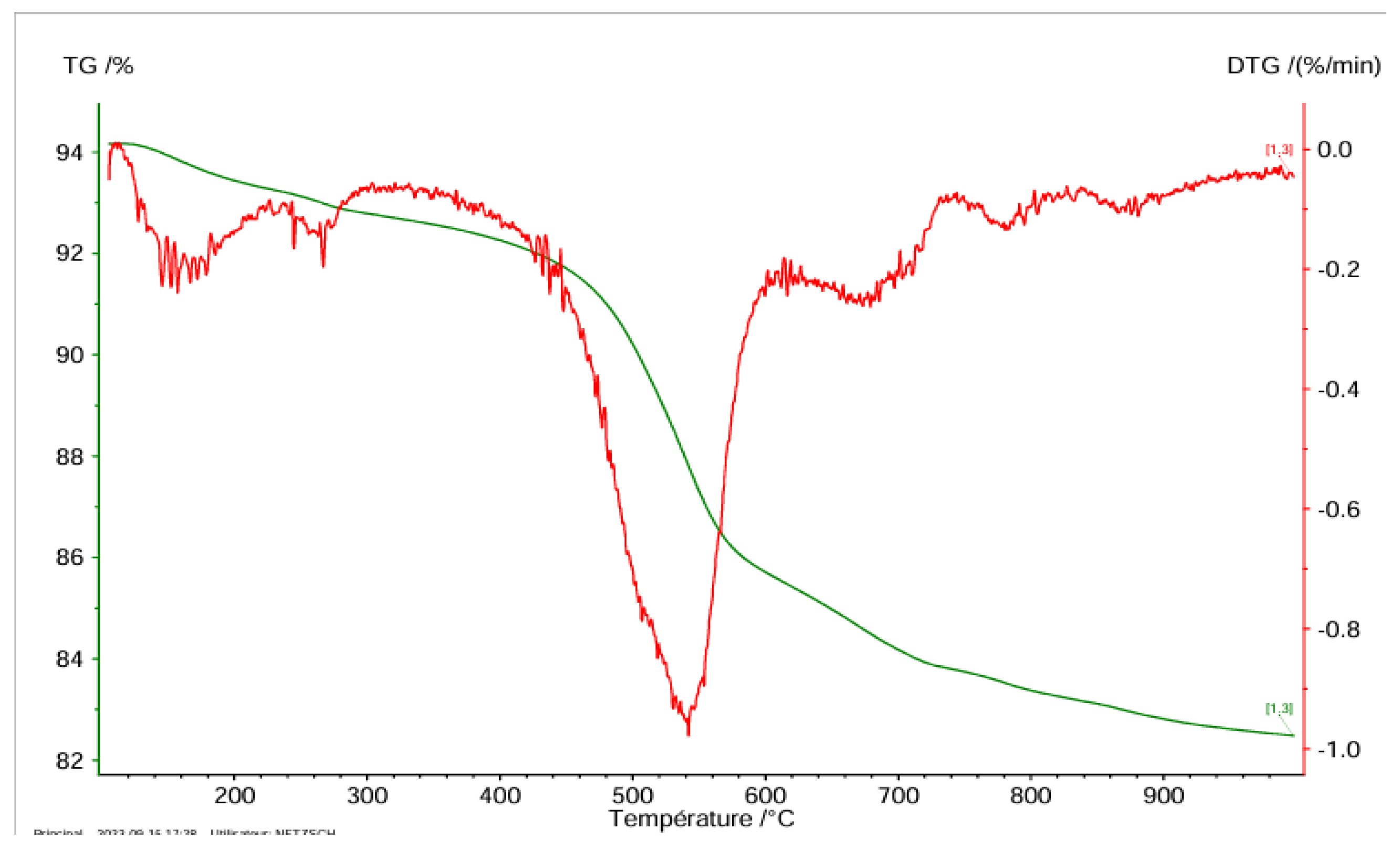

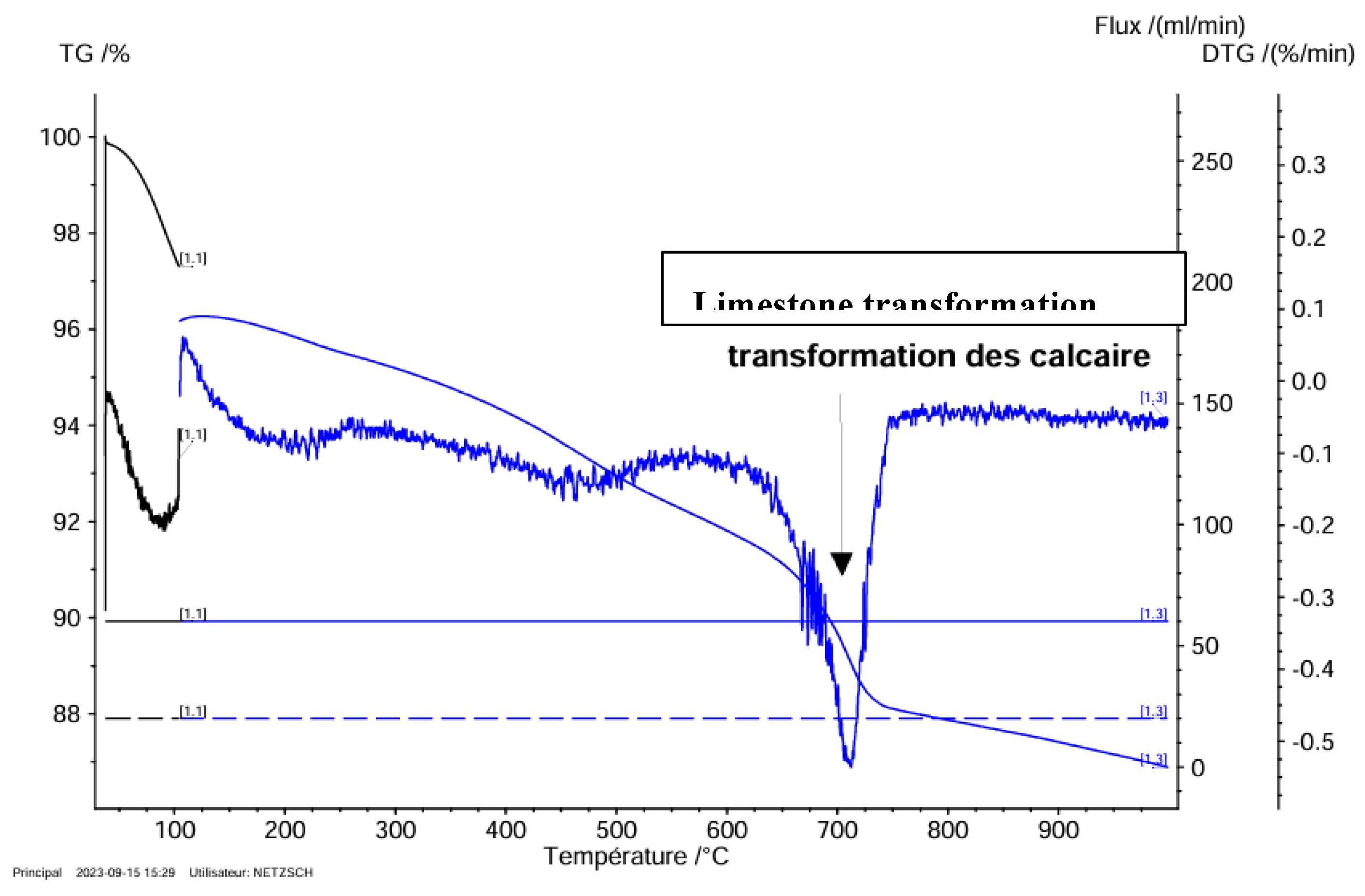

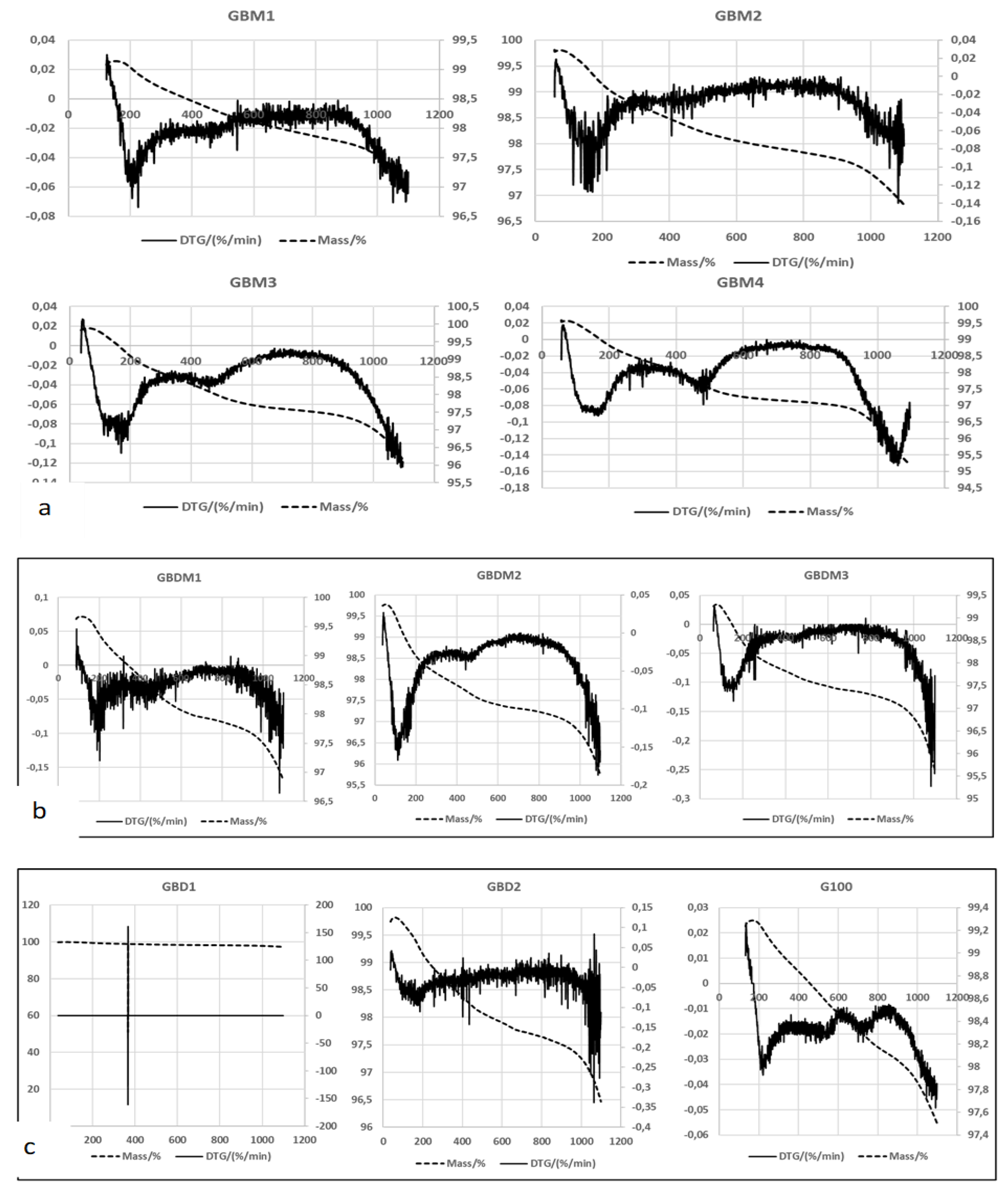

Thermogravimetric Test

Phosphate Sludge

- 200°C to 400°C: 7.4% loss, corresponding to the decomposition of organic matter. This is due to thermolyzing organic compounds in the sludge, like proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates.

- 400°C to 600°C: 1.3% loss, attributed to fluorapatite decomposition. This occurs through dehydration, transforming fluorapatite into hydroxyapatite.

- 600°C to 800°C: 1.5% loss, associated with calcite decomposition. This stems from the thermal breakdown of calcite into calcium oxide.

Natural Clay

Diatomite Mineral

Environmental Characterization of Raw Materials:

Geopolymer Bricks Characterization

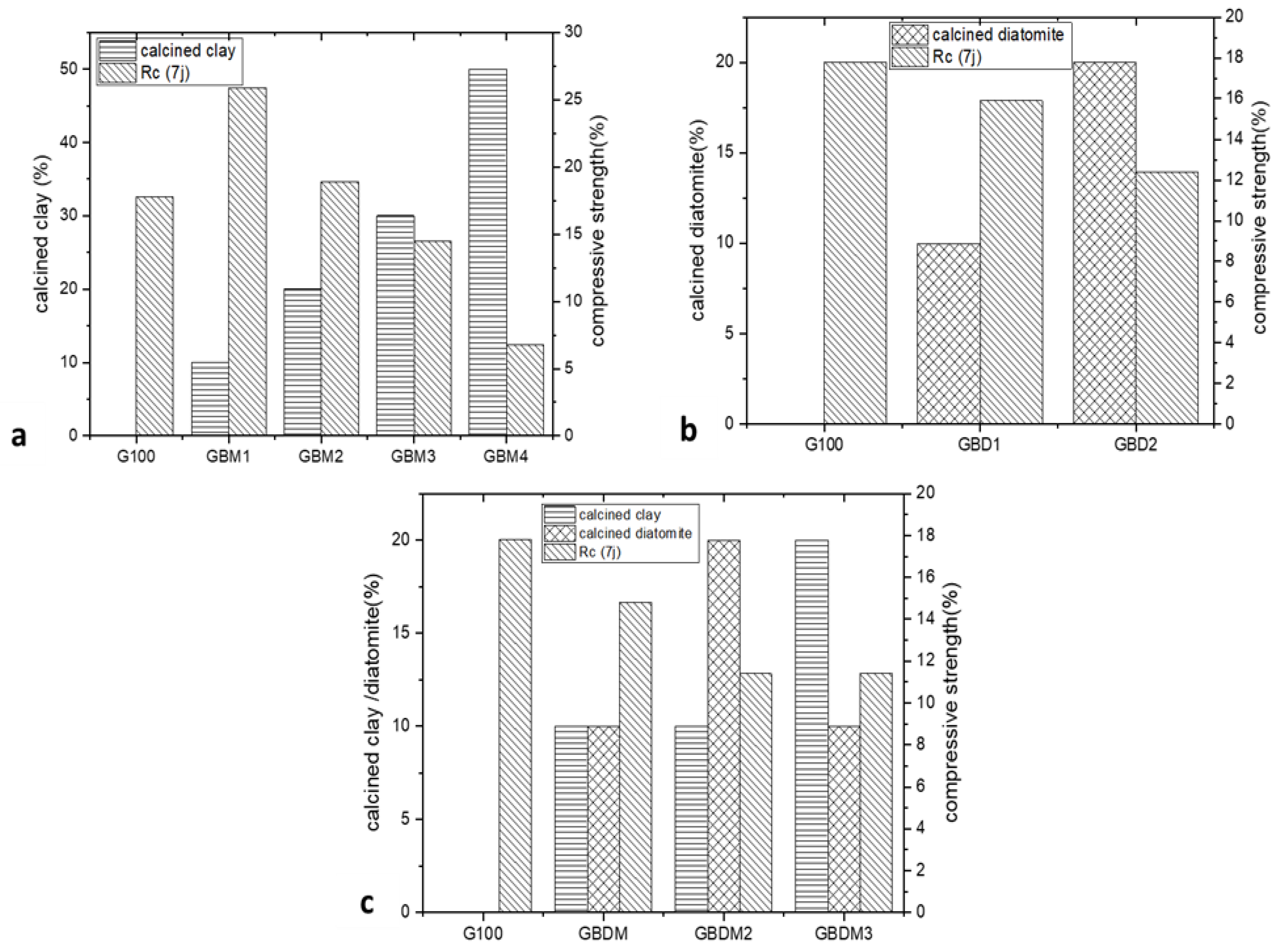

Compressive Strength

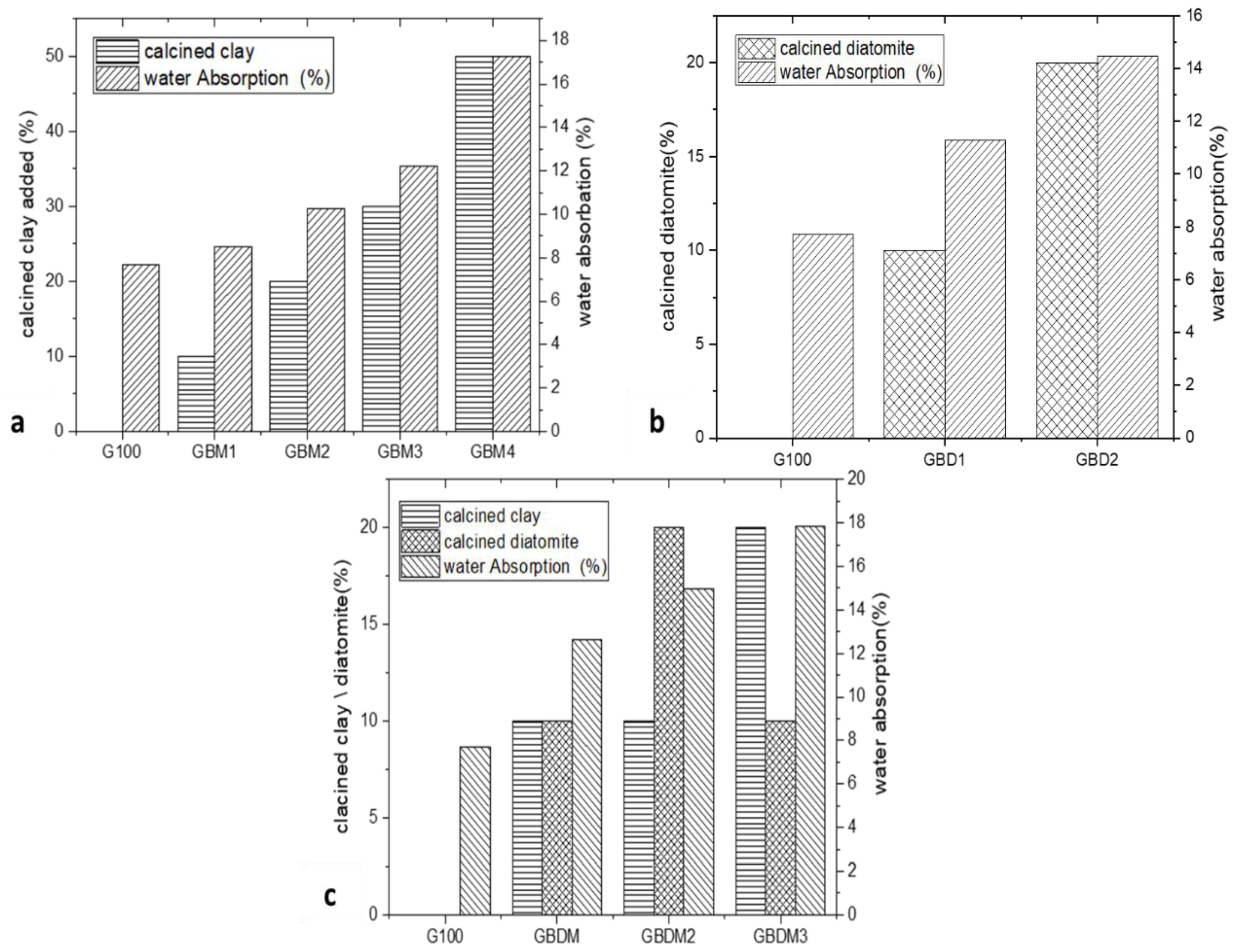

Water Absorption

| References | Valuation ways | Raw materials | Origine | Firing conditions | Water absorption (%) | Compressive strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | Fired bricks | 100% phosphate sludge | Tunisia Kef schfeir |

Air drying for 24 h Oven drying at 60°C for 24 h Firing at 900°C, 1000°Cand 1100°C for 3 h (heating rate of 120°C |

12.5-17.2 | _ |

| [14] | Ceramics bricks | Indonesian sludge (Banten Province) | 25-50% of phosphate sludge + kaolin | dried d in an oven at110°C for at least 24 hours. a heating rate of 5°C/min to 500°C, at 10°C/min from 500 to 925°C and at 15°C/min from 925°C |

>30.23 | > à 25 |

| [16] | Ceramics products | Tunisian phosphateKef eddour | 0-50% phosphate sludge +kaolin | dried at 105 ° C for 24 h. The dried pellets were heated at 900, 1000 and 1100 °C for up to 2 h | _ | _ |

| [24] | Ceramics industries | Marrocan sludge | 0-100% sludge+0-100% clay | heating ramp 5 ◦C/min up to the selected firing temperature (600, 900, 1000, 1100, and 1120 ◦C) 2h dwell time at the temperature selected |

||

| [25] | Geopolymer | Marroc phosphate industry | alkaline solution, metakaolin-in and thermally untreated phosphate sludge (UPS)(of50%) | liquid to solid ratio of L/S=1.2. left drying at 60°C for 24 h. hardened matrices for 28 days |

_ | 28.05-46.83 |

| [26] | geopolymer | Fly ash came from the heat and power plant in Skawina (Poland), the metakaolin came from the Czech Republic and the diatomite came from the Jawornik Ruski | Fly ash (FA) + metakaolin (MK) + 1–5% diatomite. | alkaline solution consisted of technical sodium hydroxide flakes with aqueous sodium silicate (a ratio of 1:2.5 was used) and tap water | Not specified | 15- 31.7 |

| [15] | Geopolymer | Phosphate washing waste and alkaline solution | PPW calcined at 700°C or 900°C, activated with NaOH (7M) and sodium silicate | 15-22 | ||

| [27] | Geopolymer | geopolymers based on Fly ash or metakaolin, | 20-70 | |||

| [28] | Fired bricks | China | 84% hematite tailings, fly ash and clay mixed with 12.5-15% of water | 20–25 MPa,of forming pressure and a suitable firing temperature was ranged from 980 to 1030 C for 2 h | 16.54–17.93% | 20.03–22.92 MPa |

| [29] | Hybrid brick | India | 70-90 % clay + 5-15% ceramic waste powder + 5-15% bagasse ash. | The bricks were cast using moulds without any pressure being applied to them. In India, the bricks were left to dry in the sun for two days at a temperature of 35 to 40 °C. For an 800 ºC firing | 11.4%-18 % | 20-27.2 |

| Current Study | Geoploymer | Phosphate washing byproduct | 50-100% phosphate washing byproduct + (10-50% calcined clay (GBM)/10-20% Calcined diatomite (GBD)/calcined diatomite +calcined clay (GBDM)) + potassium silicates solution | materials were calcined at 700°C; 750°C and 800°C, activated with potassium silicate solution then pressed, cured at ambient temperature for 72 hours, and oven-dried at 105°C for 24 hours | 7.7-17.8% | 7-26 MPa |

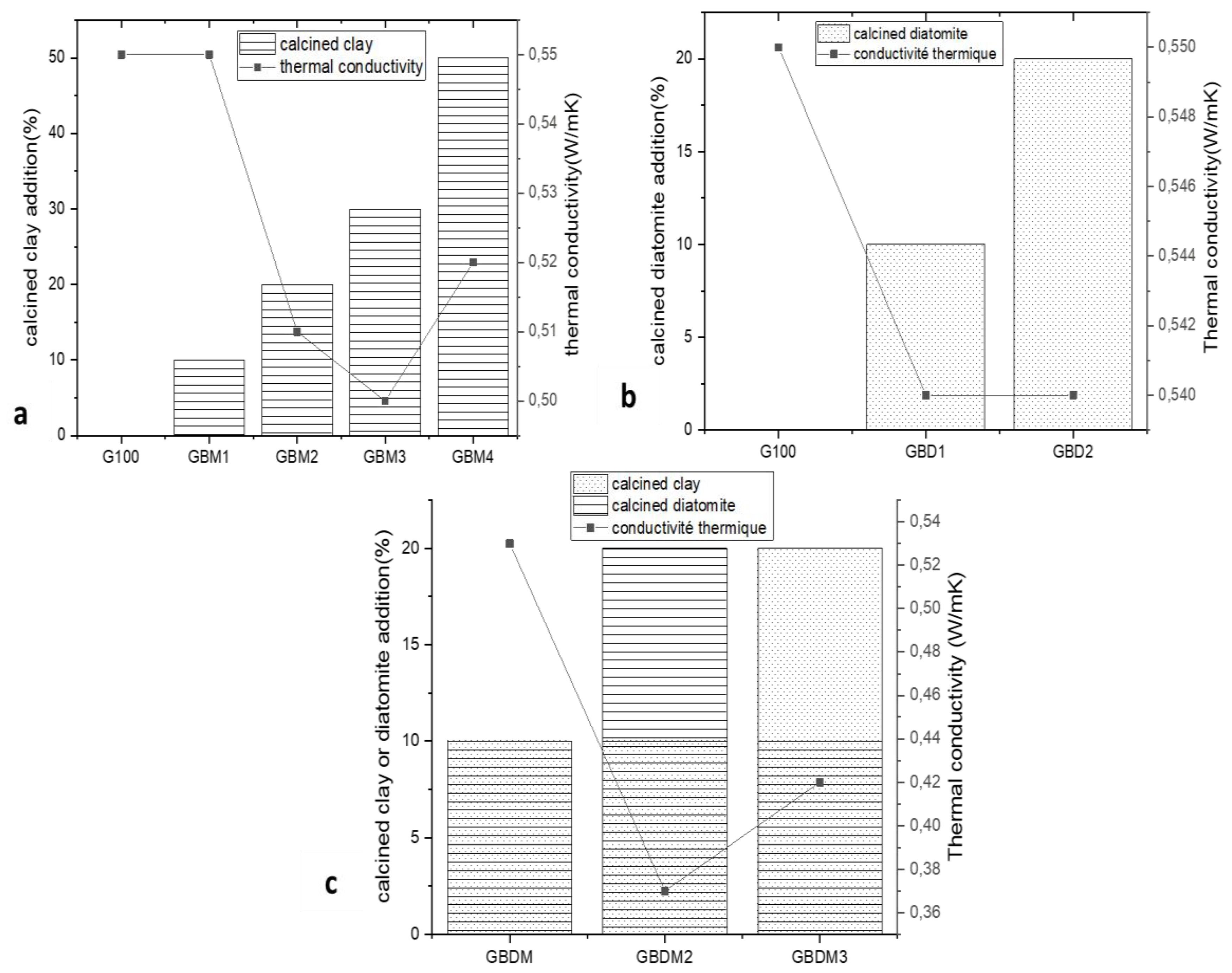

Thermal Conductivity

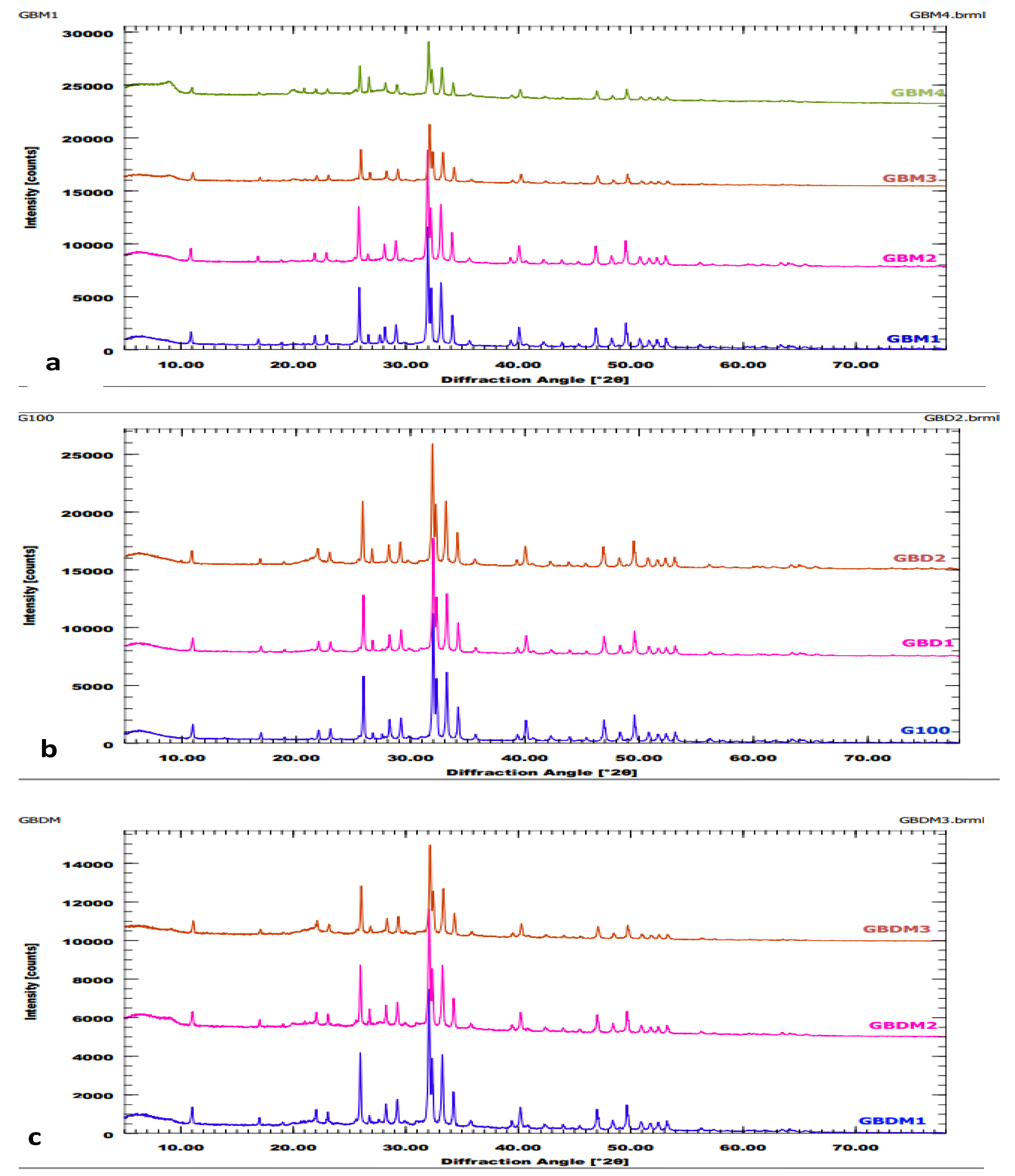

X-Ray Diffraction Results

FTIR Analysis

Thermogravimetric Analysis

Environmental Assessment of Heavy Metal and Anion Leaching from Geopolymer Formulations

Conclusions

References

- H. Idrissi et al., “Sustainable use of phosphate waste rocks: From characterization to potential applications,” Mater Chem Phys, vol. 260, p. 124119, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Hakkou, M. Benzaazoua, and B. Bussière, “Valorization of Phosphate Waste Rocks and Sludge from the Moroccan Phosphate Mines: Challenges and Perspectives,” Procedia Eng, vol. 138, pp. 110–118, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Brahmi, S. Zouari, and M. Rossi, “L ’ industrie minière et ses effets écologiques. État socio-économique et environnemental dans le bassin minier tunisien,” pp. 109–120, 2019.

- A. Bayoussef et al., “Manufacturing of high-performance ceramics using clays by-product from phosphate mines,” in Materials Today: Proceedings, Elsevier, Jan. 2020, pp. 3994–4000. [CrossRef]

- M. Ettoumi et al., “Characterization of phosphate processing sludge from Tunisian mining basin and its potential valorization in fired bricks making,” J Clean Prod, vol. 284, p. 124750, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Obenaus-Emler, M. Falah, and M. Illikainen, “Assessment of mine tailings as precursors for alkali-activated materials for on-site applications,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 246, p. 118470, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Moukannaa, M. Loutou, M. Benzaazoua, L. Vitola, J. Alami, and R. Hakkou, “Recycling of phosphate mine tailings for the production of geopolymers,” J Clean Prod, vol. 185, pp. 891–903, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Zeng, Y. Ge, W. Sun, X. Du, W. Chen, and G. Duan, “Method for purifying flotation phosphate tailings and preparing concrete blocks,” Nov. 2019.

- F. Boutaleb, N. Boutaleb, S. Deblij, S. El Antri, and B. Bahlaouan, “Effect of Phosphate Mine Tailings from Morocco on the Mechanical Properties of Ceramic Tiles,” International Journal of Engineering Research and, vol. 9, no. 02, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Z. Boutaleb, N. Boutaleb, B. Bahlaouan, D. Sanaa, and S. El Antri, “Production of ceramic tiles by combining Moroccan phosphate mine tailings with abundant local clays,” Mediterranean Journal of Chemistry, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 568–576, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Harech et al., “From by-product to sustainable building material: Reusing phosphate washing sludge for eco-friendly red brick production,” Journal of building engineering, vol. 78, pp. 107575–107575, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. Inabi, A. Khalil, A. Zouine, R. Hakkou, M. Benzaazoua, and Y. Taha, “Investigation of the Innovative Combined Reuse of Phosphate Mine Waste Rock and Phosphate Washing Sludge to Produce Eco-Friendly Bricks,” Buildings, vol. 14, no. 9, pp. 2600–2600, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Kulakowski, F. A. Brehm, C. A. M. Moraes, A. Pampanelli, and V. Reckziegel, “Monitoring and Evaluation of Industrial Production of Fired-Clay Masonry Bricks with 2.5% of Phosphatization Sludge,” Key Eng Mater, vol. 634, pp. 206–213, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Muliawan and S. Astutiningsih, “Preparation and characterization of Phosphate-Sludge kaolin mixture for ceramics bricks,” International Journal of Technology, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 317–324, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Dabbebi, S. Baklouti, J. L. Barroso de Aguiar, F. Pacheco-Torgal, and B. Samet, “Investigations of geopolymeric mixtures based on phosphate washing waste,” Science and Technology of Materials, vol. 30, pp. 1–5, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Baccour, H. Koubaa, and S. Baklouti, “Phosphate sludge from tunisian phosphate mines: Valorisation as ceramics products,” Advances in Science, Technology and Innovation, pp. 1479–1480, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Mkaouar, “Valorisation de quelques formations argileuses pour la production de Briques en Terres Crues et de matériaux Géopolymères,” 2021. [Online]. Available: http://www.theses.rnu.tn/fr/dynamique/uploads/cfd2b6661e8090e5e6f9672023c2d062.pdf.

- S. Louati, S. Baklouti, and B. Samet, “Geopolymers Based on Phosphoric Acid and Illito-Kaolinitic Clay,” Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Zheng, Z. Ren, H. Gao, A. Zhang, and Z. Bian, “Effects of calcination on silica phase transition in diatomite,” J Alloys Compd, vol. 757, pp. 364–371, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Ilia, M. G. Stamatakis, and T. S. Perraki, “Mineralogy and technical properties of clayey diatomites from north and central Greece,” vol. 1, no. 4, 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Tlili, R. Saidi, A. Fourati, N. Ammar, and F. Jamoussi, “Mineralogical study and properties of natural and flux calcined porcelanite from Gafsa-Metlaoui basin compared to diatomaceous filtration aids,” Appl Clay Sci, vol. 62–63, pp. 47–57, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- “Moyens et méthodes pour améliorer la résistance à la compression de la brique réfractaire - Support technique - Zibo Jucos Co., Ltd,” Zibo Jucos Co., Ltd. Accessed: Mar. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://fr.jucosceramicfiber.com/info/ways-and-methods-of-improving-compressive-stre-48546449.html#.

- Y. Taha, “Valorisation des rejets miniers dans la fabrication de briques cuites : Évaluations technique et environnementale,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Amine, M. Mesnaoui, and Y. Abouliatim, “Effect of temperature and clay addition on the thermal behavior of phosphate sludge,” Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Cerámica y Vidrio, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 194–204, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Hamdane et al., “Effect of alkali-mixed content and thermally untreated phosphate sludge dosages on some properties of metakaolin based geopolymer material,” Mater Chem Phys, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Nykiel et al., “The Influence of Diatomite Addition on the Properties of Geopolymers Based on Fly Ash and Metakaolin,” pp. 1–18, 2024.

- L. Chen, Z. Wang, Y. Wang, and J. Feng, “Preparation and properties of alkali activated metakaolin-based geopolymer,” Materials, vol. 9, no. 9, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, Y. Zhang, T. Chen, Y. Zhao, and S. Bao, “Preparation of eco-friendly construction bricks from hematite tailings,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 2107–2111, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Malkapuram, S. O. Ballari, S. Chinta, P. Rajasekaran, and B. Venkatesan, “Mechanical , water absorption , efflorescence , soundness and morphological analysis of hybrid brick composites,” 2024, [Online]. [CrossRef]

- C. Bories, M. E. Borredon, E. Vedrenne, and G. Vilarem, “Development of eco-friendly porous fired clay bricks using pore-forming agents: A review,” J Environ Manage, vol. 143, pp. 186–196, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Phonphuak, M. Teerakun, A. Srisuwan, P. Ruenruangrit, and P. Saraphirom, “The use of sawdust waste on physical properties and thermal conductivity of fired clay brick production,” International Journal of GEOMATE, vol. 18, no. 69, pp. 24–29, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pouhet Raphaëlle, “phd Formulation and durability of metakaolin-based geopolymers,” HAL Open SCIENCE, no. April, pp. 1–264, 2015, [Online]. Available: https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01297848%0Ahttps://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01297848/file/2015TOU30085.pdf.

- S. Selmani et al., “Physical–chemical characterization of Tunisian clays for the synthesis of geopolymers materials,” Journal of African Earth Sciences, vol. 103, pp. 113–120, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Essaidi, “Discipline : Matériaux Céramiques et Traitements de Surface Najet ESSAIDI Le 12 Décembre 2013 Formulation de liant aluminosilicaté de type géopolymère à base de différentes argiles Tunisiennes,” 2013, [Online]. Available: https://cdn.unilim.fr/files/theses-doctorat/2013LIMO4030.pdf.

- Z. H. Zhang, H. J. Zhu, C. H. Zhou, and H. Wang, “Geopolymer from kaolin in China: An overview,” Appl Clay Sci, vol. 119, pp. 31–41, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Luhar and S. Luhar, “A Comprehensive Review on Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer,” Journal of Composites Science, vol. 6, no. 8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Zeghichi and S. Benalia, “Les géopolymères : matières premières et influence des paramètres de composition: a review,” The Journal of Engineering and Exact Sciences, vol. 9, no. 11, p. 18838, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. AHMED HASSEN and Z. ADDA BENIKHLEF, “Synthés et caractérisation de liant hydrauliques Présenté Par :” [Online]. Available: https://dspace.univ-temouchent.edu.dz/bitstream/123456789/4990/1/inbound3408018541411183319 - Mahmoud Ahmed.pdf.

- N. Essaidi, B. Samet, S. Baklouti, and S. Rossignol, “Feasibility of producing geopolymers from two different Tunisian clays before and after calcination at various temperatures,” Appl Clay Sci, vol. 88–89, pp. 221–227, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Tchakouté Kouamo, “Elaboration et caractérisation de ciments géopolymères à base de scories volcaniques,” 2013. [Online]. Available: http://lopesphilippe.free.fr/CimentsGeopolymeresScoriesVolcaniquesTchakouteKouame2013.pdf.

- H. Cheng-yong, L. Yun-ming, M. Mustafa, and A. Bakri, “Thermal Resistance Variations of Fly Ash Geopolymers : Foaming Responses,” no. November 2016, pp. 1–11, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. E. L. Alouani, “En vue de l ’ obtention du DOCTORAT Synthèse et caractérisation des matériaux inorganiques de type géopolymères à base de cendres volantes et de métakaolin : Application en génie de l ’ environnement et génie civil,” 2020.

- X. Ren, F. Wang, X. He, and X. Hu, “Resistance and durability of fly ash based geopolymer for heavy metal immobilization: properties and mechanism,” RSC Adv, vol. 14, no. 18, pp. 12580–12592, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Particle Diameter (µm) | Diameter | Volume % |

|---|---|---|

| D10 | 10 | 1.2 |

| D25 | 25 | 6.0 |

| D50 | 50 | 42.7 |

| D75 | 75 | 136.7 |

| D90 | 90 | 178.4 |

| Bulk Density (γₛ) | 2.85 g/cm³ | |

| Loss on Ignition (W_LOI) | 6.23 % | |

| Water Demand (D_water) | 0.243 % | |

| Elements | Phosphate sludge (mg/l) | Clay mineral | diatomite | Calcined clay | Calcined Phosphate sludge | Calcined diatomite | ISDI | ISDND | ISDD |

| As | <0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0,18 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0.5 | 2 | 25 |

| Ba | 0.068 | < 0.008 | 0,026 | < 0.008 | 0,34 | 0,034 | 20 | 100 | 300 |

| Cd | <0.009 | < 0.009 | < 0.009 | < 0.009 | < 0.009 | < 0.009 | 0.04 | 1 | 5 |

| Cr | 0.025 | < 0.004 | 0,01 | 15 | 79 | 17 | 0.5 | 10 | 70 |

| Cu | <0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | 2 | 50 | 100 |

| Mo | 0.55 | 0,18 | 2,0 | 0,88 | 7,3 | 6,1 | 0.5 | 10 | 30 |

| Ni | <0.05 | < 0.05 | 0,076 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | 0.4 | 10 | 40 |

| Pb | <0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | 0.5 | 10 | 50 |

| Sb | <0.06 | < 0.06 | < 0.06 | 0,06 | 0,34 | < 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.7 | 5 |

| Se | 0.088 | 0,32 | 0,48 | 0,23 | 5,8 | 0,99 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 7 |

| Zn | 0.63 | 0,81 | 0,91 | 0,82 | 0,96 | 0,61 | 4 | 50 | 200 |

| Sulfates | 4760 | 644 | 724 | 353 | 450 | 1350 | 1000 | 20000 | 50000 |

| Chlorures | 386 | 487 | 80 | 259 | 70 | 13,5 | 800 | 15000 | 25000 |

| Fluorures | 14 | 2,0 | 1,5 | 2,1 | 13,4 | 1,8 | 10 | 150 | 500 |

| Elements | GBM1 | GBM2 | GBM3 | GBM4 | GBD1 | GBD2 | GBDM1 | GBDM2 | GBDM3 | G100 | ISDI | ISDND | ISDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.13 | 0.35 | <0.1 | 0.12 | <0.1 | 0.13 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0.5 | 2 | 25 |

| Ba | < 0.008 | < 0.008 | < 0.008 | < 0.008 | < 0.008 | < 0.008 | < 0.008 | < 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 20 | 100 | 300 |

| Cd | <0.009 | <0.009 | <0.009 | <0.009 | < 0.009 | < 0.009 | < 0.009 | < 0.009 | < 0.009 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 1 | 5 |

| Cr | 10 | 13 | 16 | 19 | 13 | 18 | 14 | 16 | 20 | 41 | 0.5 | 10 | 70 |

| Cu | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | 2 | 50 | 100 |

| Mo | 0.91 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 10 | 30 |

| Ni | <0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | 0.4 | 10 | 40 |

| Pb | <0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | 0.05 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | < 0.03 | 0.5 | 10 | 50 |

| Sb | <0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.065 | < 0.06 | 0.079 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.7 | 5 |

| Se | 0.87 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 7 |

| Zn | < 0.01 | 0.74 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 4 | 50 | 200 |

| Sulfates | 243 | 772 | 734 | 151 | 1033 | 841 | 298 | 1042 | 1100 | 595 | 1000 | 20000 | 50000 |

| Chlorures | 50 | 70 | 98 | 151 | 34 | 25 | 54.5 | 74.4 | 40.3 | 40.8 | 800 | 15000 | 25000 |

| Fluorures | 4.9 | 8.4 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 11 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 8.0 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 10 | 150 | 500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).