1. Introduction

Nowadays, the need for recycling, minimizing source depletion and implementing sustainability production play an important role in every economic sector [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Geopolymers (GPs) and, more in general, alkali-activated materials (AAM) are widely used because of their ability to entrap several wastes as precursors or fillers [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], thus meeting the goals of Circular Economy [

10]. These materials have been used as main competitors for the Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), which production is highly polluting since the need for high calcination temperatures leads to a huge amount of greenhouse gas emissions, as well as a huge amount of energy consumption [

11,

12]. GPs are a subclass of AAM rich in Al and poor in Ca content that are activated in alkaline solutions (such as KOH, NaOH, sodium silicate, potassium silicate) [

13,

14]. During the reactions, the aluminosilicate precursor (e.g. metakaolin or MK, fly ashes, ground granulated blast furnace slags, etc.) undergoes dissolution and leads to the formation of inorganic oligomers composed of several Si⁴⁺ and Al³⁺ ions linked by bridging oxygen atoms originating from terminal OH groups. This is followed by polycondensation, and reorganization, thus resulting in an amorphous material with high mechanical performances [

15,

16,

17]. On the other hand, the non-homogeneous properties of MK, caused by a remarkable difference of structure, chemical composition and reactivity, were overcome in the past by synthesizing Al

2O

3·2SiO

2 ceramic materials as precursors to replace MK in the preparation of geopolymers [

18]. Since many wastes can be used either as a precursor or as filler, the final consolidated materials could show several properties [

19,

20,

21]. Still there is the need to understand how the presence of the different wastes affects the properties of the GPs. Moreover, the comprehension of waste behavior used before and after alkaline activation is still an important aspect to consider.

In this study, we tested industrial waste materials without any pre-treatment in order to increase the sustainability of the process. Specifically, four types of industrial solid waste (SW) were used: i) suction dust (SW1); ii) red sludge from alumina production (SW2); iii) electro-filter dust (SW3); and (iv) extraction sludge from partially stabilized industrial waste (SW4). All these wastes have been used to replace 20 wt.% of MK and the properties of consolidated geopolymers have been investigated through Fourier-Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), simultaneous thermal analysis, integrity test, boiling test, mechanical properties, leaching test and antimicrobial properties. Furthermore, since this waste has been already used as filler, a comparison with this case study is reported in the Discussion section.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Metakaolin (MK), purchased from IMCD Deutschland GmbH & Co., Cologne, Germany, is used as a main precursor for geopolymer synthesis. This MK is characterized by a d

50 = 3.6 µm, a surface area via B.E.T. of 12 m²/g and a chemical composition as follow: 53 wt.% SiO₂, 40.5 wt.% Al₂O₃, 5 wt.% TiO₂, and 1.5 wt.% of minor oxides [

22].

Four different types of industrial waste were provided by an Italian company located in Aversa. These waste materials along with their main properties and labels are detailed in

Table 1, while their macroscopic and microscopic appearance, and complex FT-IR spectra are shown in

Figure 1. From Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images it can be observed that SW1 is composed by polyhedral spheres with a particle size ranging in 50-150 µm. Smaller powdery-like irregular particles are composed mainly by Sb (which is in agreement with data reported in

Table 1). SW2 is composed of very fine particles, spherical in shape, with two different composition and sizes: larger ones (10-20 µm in size) are composed of lighter elements and appear gray in color, while smaller ones (1-5 µm in size) are composed of heavier elements and appear white in colour. SW3 showed particle sizes very similar to those of sample SW2, while SW4 is composed of large grains (about 200 µm) with irregular shape, closer to that of rigid aggregate rather than to single crystal. They are very homogeneous in the gray scale, indicating a uniformity in chemical composition. A detailed characterization of FT-IR spectra can be found elsewhere in [

23].

Prior to use, all wastes were sieved to be sure that all particles possess diameters smaller than 75 μm, ensuring uniformity for incorporation into the geopolymer formulations.

Sodium silicate solution, with a pH of 12.5 and a molar ratio of SiO₂ to Na₂O of 2.6, was provided by Prochin S.r.l., located in Caserta, Italy. Its chemical composition included 27.10 wt.% SiO₂, 8.85 wt.% Na₂O, and 64.05 wt.% H₂O.

Sodium hydroxide pellet, MilliQ water, potassium bromide and sodium chloride (reagent grade) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich in Milan, Italy.

Tripton Bile X-gluconoside Agar medium and Slanetz Bartley medium were purchased from Liofilchem S.r.l., Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy. Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) were purchased from VWR International Eurolab SL, Spain.

2.2. Methods

The mixing process (whose flow-chart procedure is shown in

Figure 2) consisted of mixing the dried MK powder with the activating solution at low speed for 10 min, and at high speed for another 10 min. Geopolymer samples containing waste have been prepared by mixing 20 wt.% of SW1, SW2, SW3 and SW4 with 80 wt.% of MK prior to the mixing with the activating solution (all formulations have been reported in

Table 2). The synthesis of the GPs was carried out using an AUCMA SM-1815Z electric mixer (AUCMA Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China). After mixing, the fresh GP pastes were placed into sealed plastic molds for 24 h in an oven at 25 °C, then demolded and allowed to cure at room temperature for 7, 14 and 28 days before their characterization.

FT-IR analysis was performed using the Prestige21 Shimadzu system (Shimadzu Italia S.R.L., Milan, Italy), equipped with a DTGS KBr detector (Shimadzu Italia S.R.L., Milan, Italy), with a resolution of 2 cm−1 (60 scans), within the range of 400–4000 cm−1. KBr disks (2 mg sample and 198 mg KBr) were utilized in the analysis procedure. The obtained FT-IR spectra were processed using IRsolution (v.160, Shimadzu, Milan, Italy) and Origin 8 (v.2022b, OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) software.

Morphology observations were conducted on manually tapped powders from the industrial wastes on carbon tape by ESEM (Environmental Scanning electron microscopy) using a QUANTA 200 (FEI, The Netherlands) microscope in high vacuum mode. The backscatter (BSE) detector was used for atomic number contrast images and the Oxford –Link Inca 350 x-ray spectrometer with for chemical analysis.

The integrity test was performed by soaking the geopolymers in MilliQ water (at a mass-to-volume ratio of 1 g/100 mL) for 24 h, following the protocol reported in [

24]. After 24 h of immersion, the integrity of the samples was estimated in terms of visible fractures and visible fragments in water leachates, as well as mass gain or loss after test [

24]. Water leachates from integrity tests were also subjected to Ionic Conductivity (IC) and pH measurements by using Crison GLP31 (for IC measurements) and Crison GLP21 (for pH measurements) (Hach Lange Spain, S.L.U, Barcelona, Spain).

The boiling water test was performed according to, by keeping the samples in boiling water for 20 min, and evaluating their rapid durability assessment [

25,

26].

Simultaneous thermogravimetry-differential thermal analysis (TG-DTA) was performed using a simultaneous TG/DTA apparatus (Stanton-Redcroft 1500, Copper Mill Lane, London, England) connected to a personal computer. Experiments were carried out under an argon flow rate of 40 cm

3·min

–1 to observe the sample thermal behavior. The heating rate used was 10 °C·min

–1. Open pan platinum crucibles were used for the TG/DTA experiments, with each experiment employing 6 to 10 mg of the different samples. The system was calibrated using several high-purity standards, including tin and indium [

27], tailored to the specific temperature range under investigation.

The compressive strength for mechanical tests has been performed by using a Dual Column Testing Systems (INSTRON, series 5967-INSTRON, Norwood, MA, USA) configured with a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. The test has been conducted with 5 specimens (cylindrical moulds - 27 mm×54 mm) per each geopolymer type.

Leaching test on samples 28 days aged are performed according to the EN 12457-2:2004 [

28]. Specifically, 5 grams of the material were ground and sieved to a particle size of less than 2 mm, then placed in Teflon® containers. These samples were immersed in distilled water using a 1:10 solid-to-liquid mass ratio and stirred magnetically for 24 hours to ensure thorough interaction between the solid and the water. After the test, the resulting leachates were separated from the solid residues, acidified to a pH of 2 using a nitric acid solution, and analyzed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). For this analysis, an iCAP TQ ICP-MS spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure ion concentrations in the diluted leachate samples. These dilution factors were accounted for when calculating the original leachate concentrations.

The antimicrobial activity of the material samples was evaluated using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method [

29]. Two bacterial strains,

E. coli and

E. faecalis, were selected because of their correlation to polluted environment and infection [

30]. Prior to testing, the samples were ground into powder and compressed into discs weighing 200 mg, then sterilized using UV light for one hour. TBX Medium and Slanertz-Bartley agar based-medium were prepared by autoclaving at 120 °C for 15 minutes and allowed to cool before being poured into Petri dishes at approximately 50 °C. The bacterial strains were suspended in a 0.9% NaCl solution to a concentration of 10⁹ CFU/mL and spread onto the appropriate solid media. Sample discs were placed at the center of each Petri dish prior to incubation. Incubation was carried out at 44 °C for

E. coli and 36 °C for

E. faecalis for 24 and 48 hours. After incubation, the inhibition halo diameters (IHDs) were measured. Three replicates have been made to measure Mean ±Standard Deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Geopolymer Stability

FT-IR analysis has been performed to investigate the influence of wastes added to MK at 20wt.% before alkali activation. FT-IR spectra were recorded at 7, 14 and 28 days of ageing time, and reported in

Figure 3. As regards the control, GP showed the characteristics redshift in the main absorption band (see green square in

Figure 3) centered at 1090 cm

-1 in MK precursor. This shift occurs because of the substitution of Si atoms with Al atoms thus leading to Si-O-Al bridge in the formed N-A-S-H (sodium aluminum silicate hydrate) gel typical of geopolymer network [

31,

32,

33]. Indeed, for GP this peak is centered at 1027 cm

-1 on 7- and 14-day aged samples, and at 1019 cm

-1 after 28 days of ageing. GP spectra are also characterized by the presence of OH- stretching and bending (see squares blue and violet in

Figure 3) vibrations at 3470 and 1655 cm

-1 thus indicating water released from geopolymer samples during geopolymerization reactions. Considering GPSW1, GPSW2, GPSW3 and GPSW4 spectra during ageing times up to 28 days, there was the redshift for all of them, thus suggesting that mixing the wastes with the MK precursor before the addition of the alkali activator does not influence geopolymerization reactions. Even though the geopolymer spectra containing wastes hide most of the waste IR peaks, slight differences in spectra are still appreciable. Indeed, the peaks in the range of 2980-2850 cm

-1 are associated with C-H vibration modes (see orange square in

Figure 3) due to the organic contaminants in the wastes [

34]. Moreover, in the GPSW2 samples the sharp band at 1720 cm

-1 is due to the C-O vibration [

35].

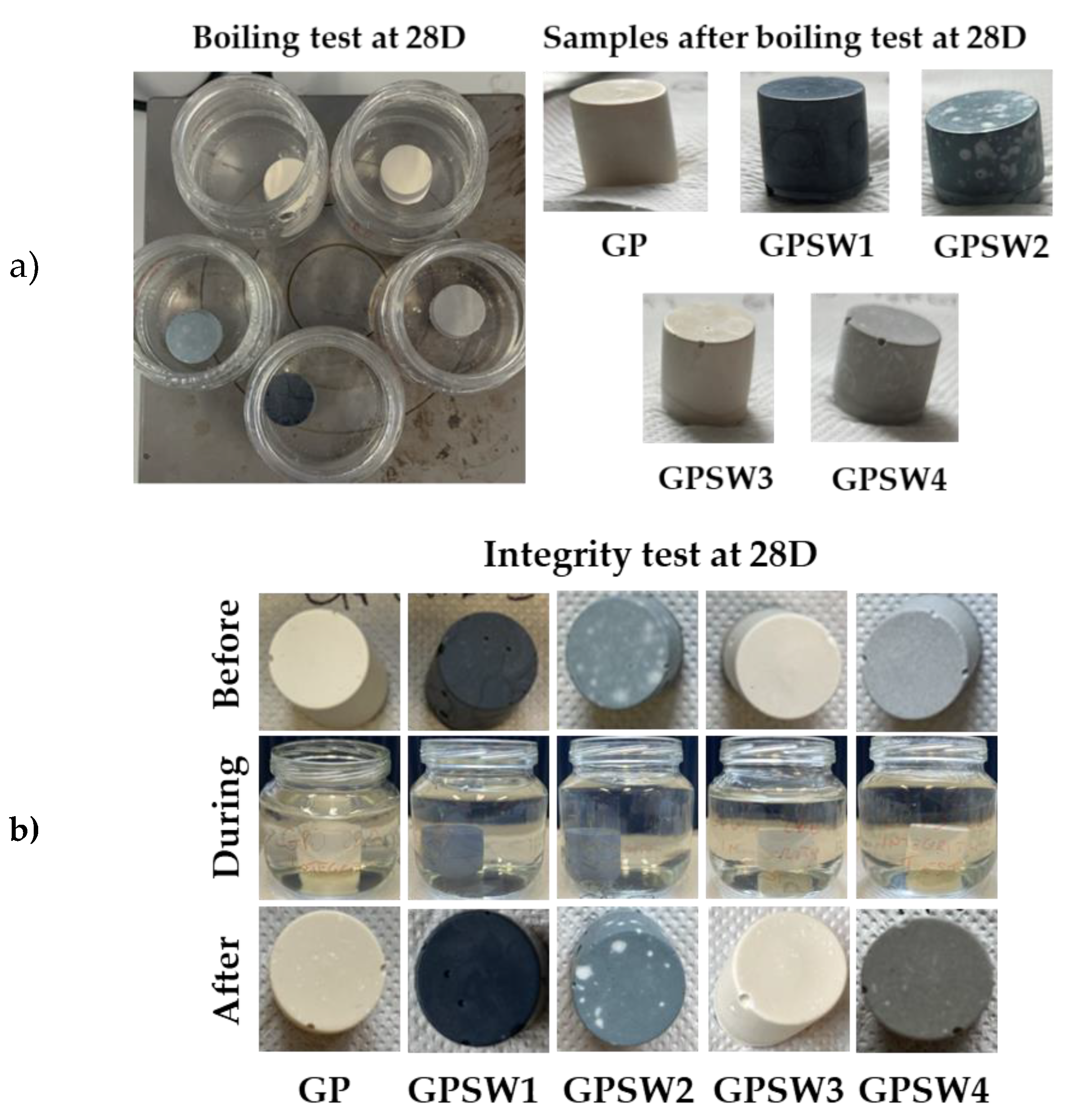

To assess geopolymer stability from the macroscopic point of view, boiling and integrity tests have been performed on all the samples at different ageing times. The images of both tests at 28 days are reported (

Figure 4 a and b, respectively). According to the literature findings, a well-formed geopolymer can resist boiling water for 20 min [

25]. In all tests performed at different ageing times, none of the samples underwent disruption during the test thus further confirming geopolymerization occurrences. This also indicates that the synthesized geopolymers are stable and long-lasting in harsh environments [

36]. Moreover, none of the samples underwent disruption during and after integrity tests, additionally confirming macroscopic stability [

37]. The white spots on GPSW2 samples in both integrity and boiling tests can be related to the efflorescence phenomenon as a consequence of not perfectly balanced charges at molecular level that leads to this macroscopic side effect [

38,

39,

40].

Geopolymer network stability has been investigated through IC and pH measurement from water leachates of the integrity tests. According to the results obtained, GP reference showed a slight increase in IC values from 14 to 28 days of ageing, maybe due to continuous network stabilization. In the reference sample the IC depends mainly on Na

+ and OH

- species released from the network [

41,

42]. GPSW1, GPSW2, GPSW3 showed a decrease in IC values from 7 to 14 days of ageing. Moreover after 28 days there was no variation in IC data suggesting the network is stable. Furthermore, GPSW3 showed very high IC values, maybe due to the possible presence of chlorides, fluorides and sulfates, since SW3 is very rich in their content. GPSW4 showed a lower IC value only after 28 days of ageing, suggesting the network is still under organization. It is worth noting that as the ageing time increases, IC values of the samples became closer to the values of GP (unless IC values of GPSW3). As regards the pH, all specimens showed a strong alkaline environment since the pH values were all above 10.9.

Table 3.

IC and pH measurements from integrity test water leachates at different ageing times. pH measurements error ±0.1 pH, while IC measurements error is ±0.2 mS/m.

Table 3.

IC and pH measurements from integrity test water leachates at different ageing times. pH measurements error ±0.1 pH, while IC measurements error is ±0.2 mS/m.

| Data from Integrity Tests |

GP |

GPSW1 |

GPSW2 |

GPSW3 |

GPSW4 |

| IC (mS/m)-7D |

2.2 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

17.5 |

4.6 |

| IC (mS/m)-14D |

2.0 |

2.1 |

3.3 |

12.6 |

4.4 |

| IC (mS/m)-28D |

2.8 |

2.2 |

3.3 |

12.7 |

3.2 |

| pH-7D |

10.9 |

10.9 |

11.0 |

11.0 |

10.9 |

| pH-14D |

11.2 |

11.5 |

11.7 |

11.8 |

11.6 |

| pH-28D |

10.9 |

10.9 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

11.0 |

3.2. Thermal Behaviour and Thermal Stability

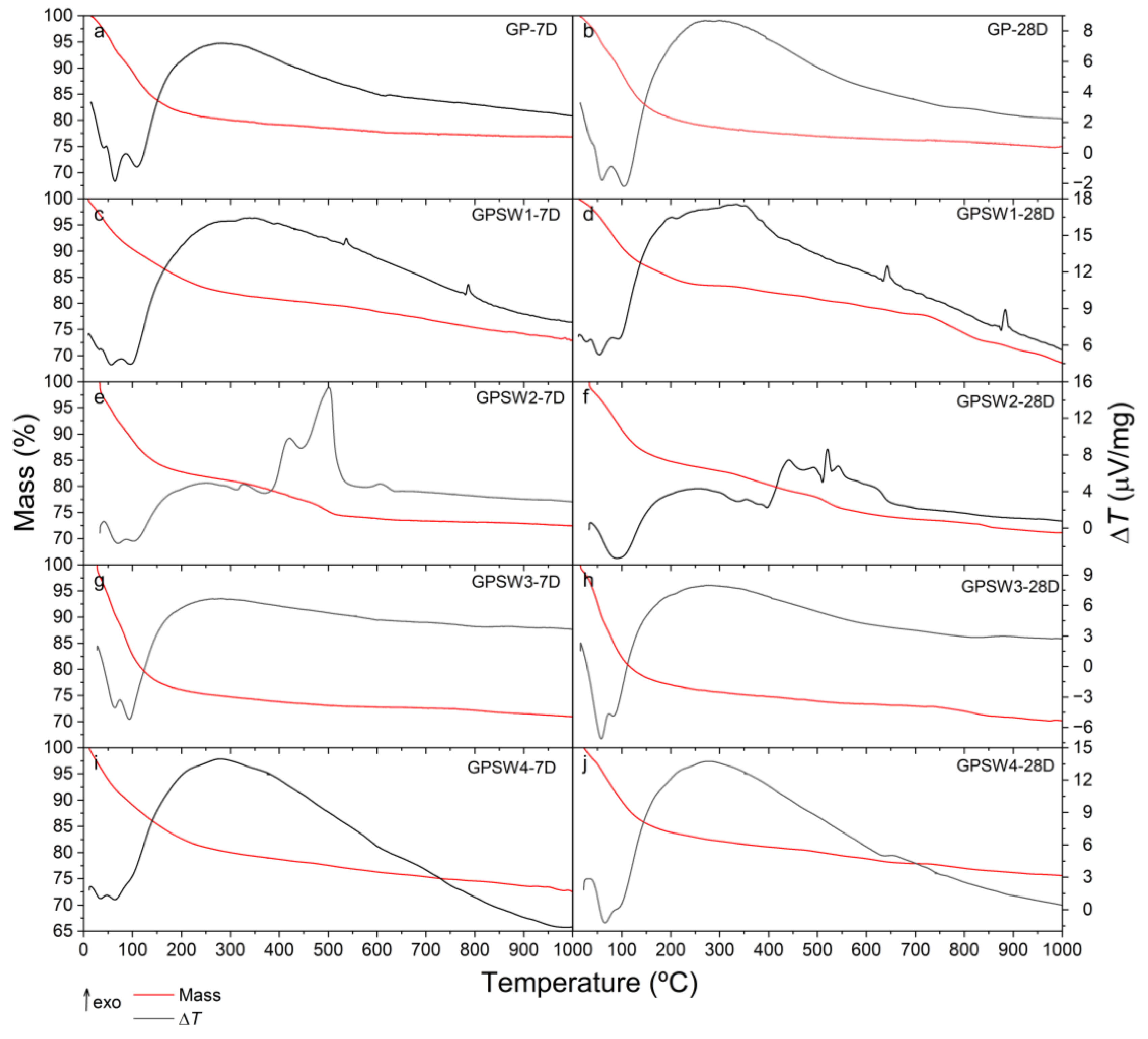

The simultaneous TG-DTA curves of GP aged for either 7 and 28 days (denoted as 7D and 28D, respectively) has been compared in

Figure 5 (plots a and b, respectively) with those of the four GPs prepared with 4 different wastes (GSPW1, GPSW2, GPSW3 and GPSW4) under the same two different aging conditions (plots c to j). The temperature ranges and the total amount of differently bound water contained in the materials (expressed as mass percentage) are summarized in

Table 4 for comparison purposes.

Plots a and b of

Figure 5 show that the GP sample undergoes two distinct mass loss steps, the first of which, up to about 270-280 °C, is ascribed to the loss of chemically and physically bound water, as evidently shown by the presence of three not-well distinguished endothermic effects in the DTA curves. The comparison of the TG/DTA curves in plot a with those in plot b demonstrated that for the pristine GP the differences are negligible and may be attributed to the aging time. A second step of mass loss takes place in a very wide temperature range (from 280 to about 700 °C) without remarkable endothermic or exothermic effects. On the basis of previous studies carried out under an inert atmosphere on these or related materials this process may be reasonably attributed to dehydroxylation, which led to the loss of water due to condensation of hydroxyl surface groups. Similar conclusions can be drawn for GPSW3 and GPSW4.

The amount of water released by GPSW1-7D due to dehydration (plot c of

Figure 5) is the lowest (around 17% by mass) and after 28 days aging this content is slightly lower (plot d of

Figure 5). Similar conclusions can also be drawn from the analysis of GPSW2 where the percentage of water loss is even more noticeable (plots f and j of

Figure 4).

In the case of GPSW1 (

Figure 5 plots c and d), two exothermic peaks on the DTA signal in both samples (7 and 28D) are observed. The fact that these are not accompanied by a more significant mass loss (besides the dehydroxilation that is also observed in the GP0) is an indicator that these are physical changes on the samples. The most likely case is that these are changes on the crystalline network of the sample. An additional experiment, i.e., a second heating scan of the sample was performed. In this case, none of the peaks was observed which leads to the conclusion that these processes are irreversible [

43,

44]. Nevertheless, this sample seems to become less stable with time. In the GPSW1_28D sample, an additional mass loss is observed between 700 and 850 ºC and the residual mass at the end is smaller.

For GPSW2 (

Figure 5, plots e and f), several exothermic peaks are observed between circa 350 and 550 ºC. As these signals are also accompanied by at least one identifiable mass loss, these processes can be ascribed to decomposition, taking place in the sample. As this sample has a larger quantity of hydrocarbons, their thermal decomposition can lead to the exothermic event observed in the experiments. This is supported by the complex FT-IR print. Furthermore, at circa 650 ºC, an exothermic, longer peak is observed on the DTA signal that is not accompanied by a mass loss. This seems to be an irreversible relaxation of the geopolymer network.

Regardless the aging time, being at 7 or 28 days (7D or 28D, respectively) the TG/DTA curves of both GPSW3 (

Figure 5, plots g and h) and GPSW4 (

Figure 5, plots i and j) samples are very similar to that of the pristine GP, thus demonstrating that the waste composition of these two samples (Cu-rich GPSW3 with very low amount of hydrocarbons and selenium rich GPSW4 with C10-C40 content lower than 100 ppm) does not affect their thermal behavior. However, it is important to note that GPSW3 seems to lose stability with time as a new mass loss appears at circa 750 ºC but that of GPSW4 seems to increase with time as it has less water and the residual mass at the end was higher at 28D than at 7D.

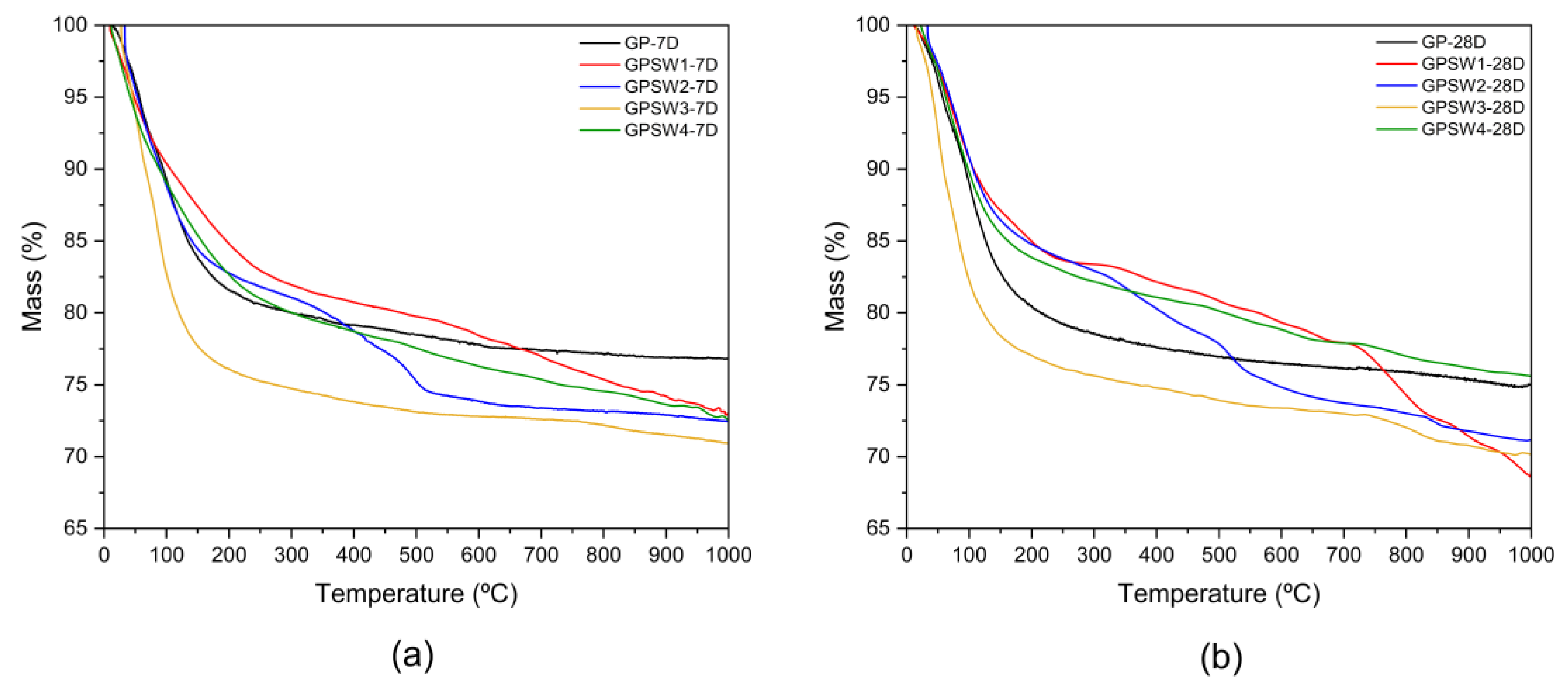

Furthermore, a comparison of the different TG curves for the different samples at 7D and 28D is presented in

Figure 6.

Their relative stability can be assessed from the residual mass at the end of the experiments. At 7D most samples have a similar residual mass with GPSW3 being the lowest. However, the scenario changes with the ageing. Here there are significant differences, the two largest are GPSW1 and GPSW4. The former loses stability with time losing almost 5 % more with aging whereas the latter gains stability with time losing much less mass. This, however, is most likely due to a much smaller amount of water present in the sample.

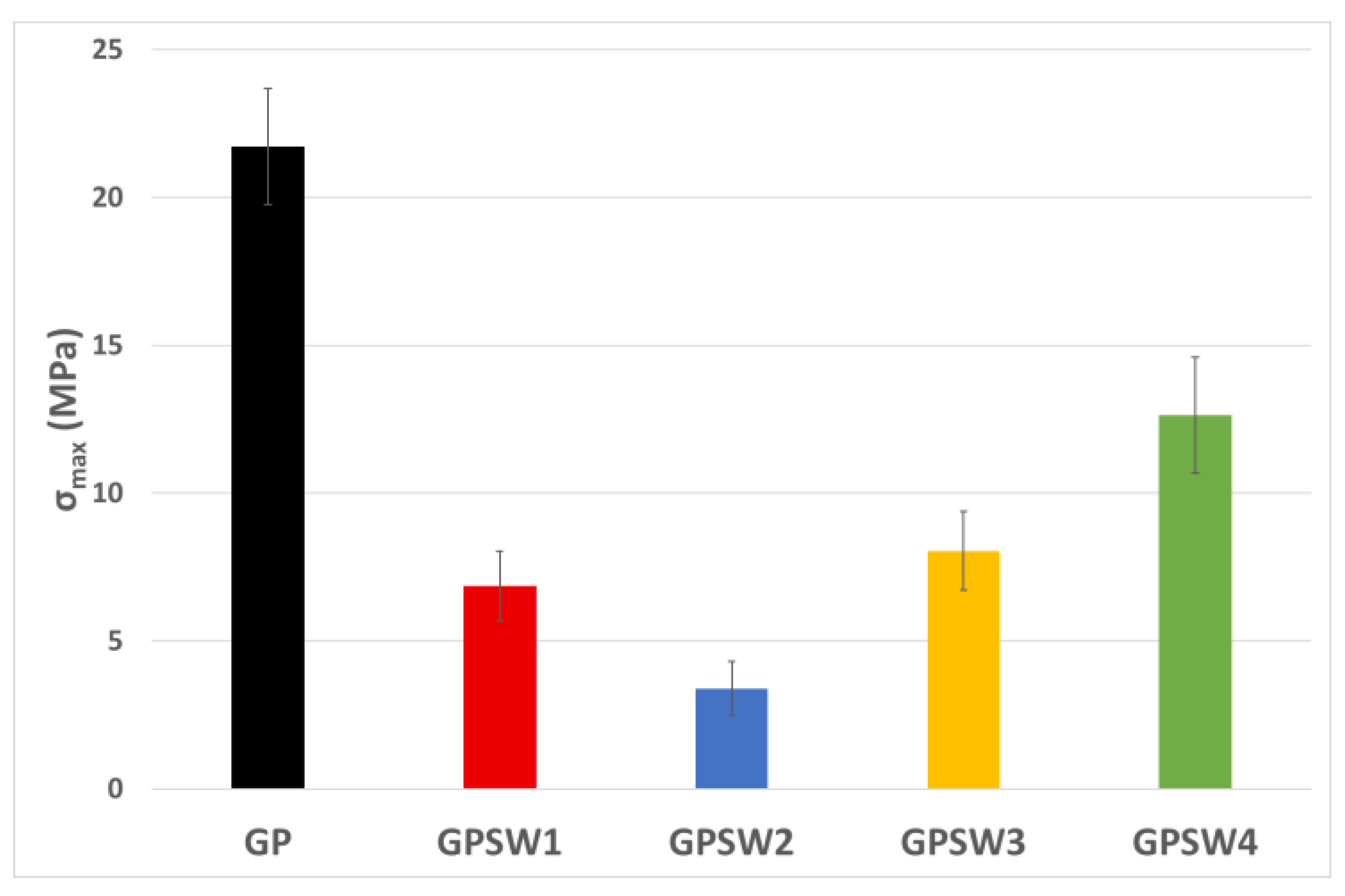

3.3. Mechanical Behavior

The results on compressive strength after 28 day of ageing times are reported in the histogram in

Figure 7. The replacemente of MK with industrial wastes led to a decrease in mechanical properties. Indeed, all σ

max values for the GPSW(1-4) series were lower than the reference one. This reduction in mechanical strength may be due to the reduction in Al content in the GPSW(1-4), since 20 wt.% of MK has been replaced with wastes [

45,

46,

47].

3.4. Leaching Test

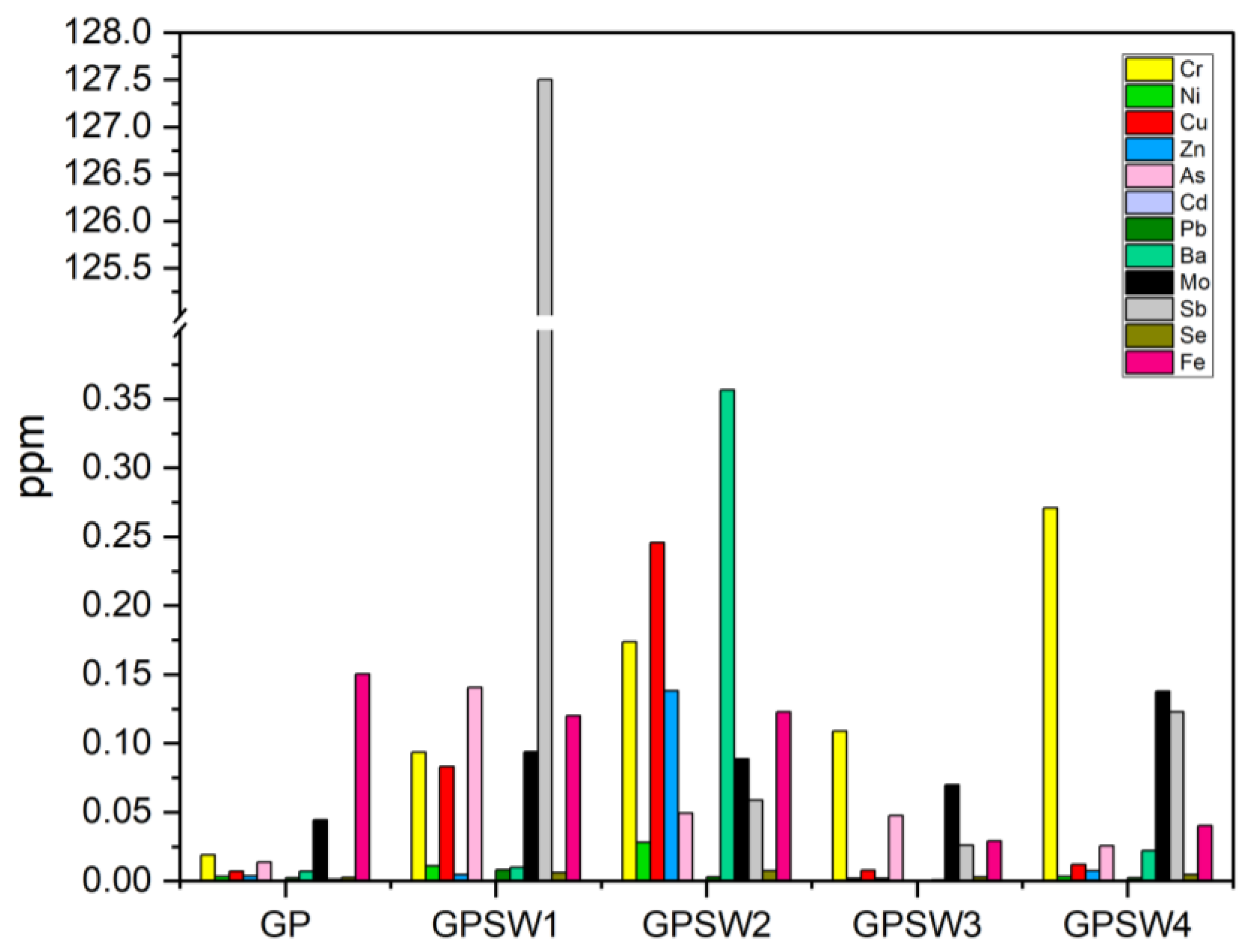

The histogram in

Figure 8 reports the data on leached heavy metals of samples 28D aged. According to the Legal limits for disposal in landfills based on the leachate (see

Table 5), GPSW1 and GPSW4 released Sb ions above 0.07 ppm. For this reason these geopolymers can be considered as hazardous in the case of their landfill disposal. Taking into account the data reported in

Table 1 on heavy metals leached from the wastes, both SW1 and SW4 showed lower ppm values, that means the alkaline environment of the geopolymers increased the leaching rate of Sb.

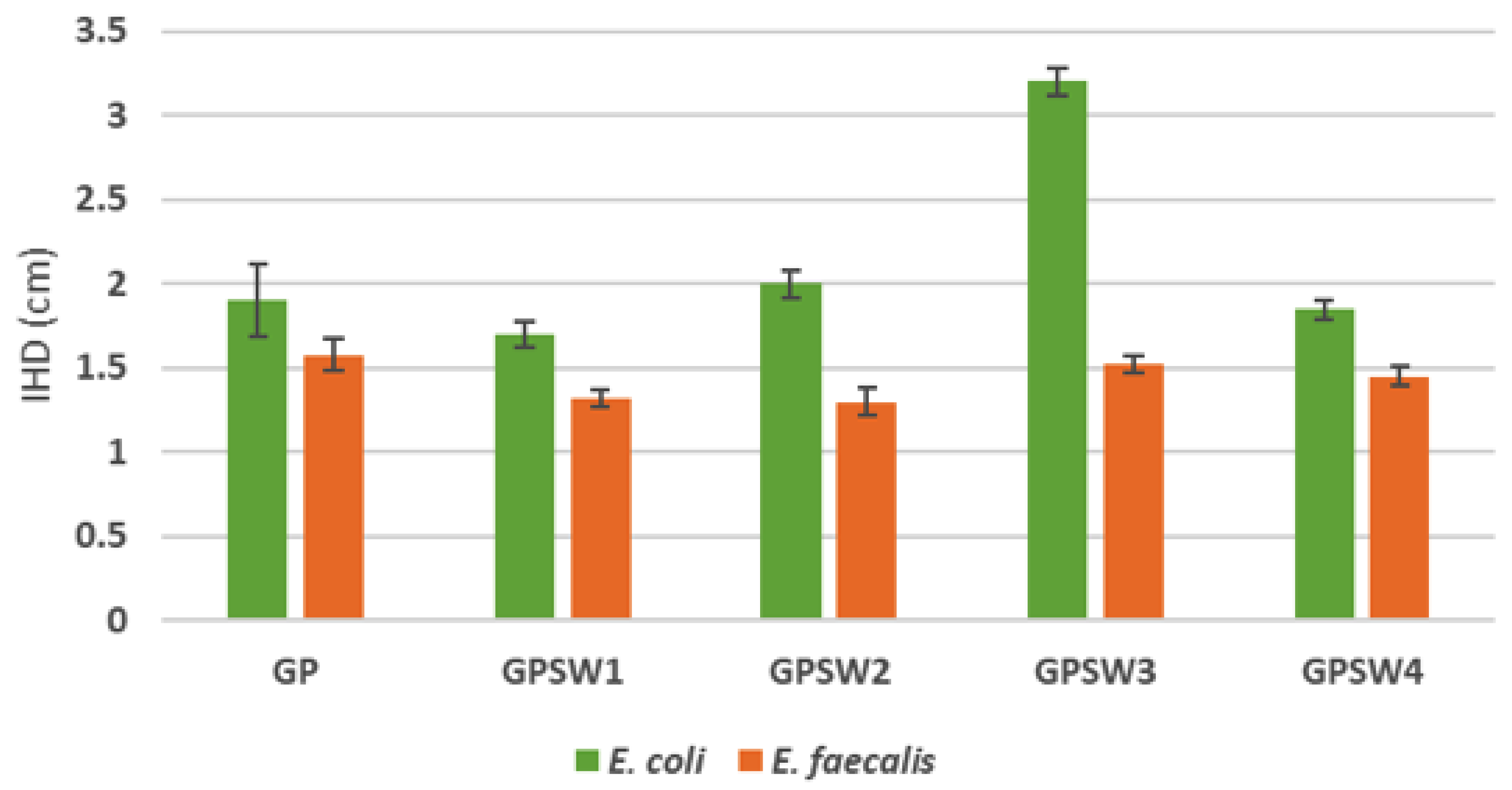

3.5. Antimicrobial Analysis

Figure 9 reveals that the presence of SW3 affect the microbial growth of E. coli. This is because of the high content of chlorides coming from the waste. Moreover, all the GPs showed a higher antimicrobial activity with respect to E. coli. This is becoause of the alkaline environment which the gram negative is more susceptible. On the other side most of the results obtained with the treatment of E. faecalis reveals that this gram positive is highly resistant to both alkaline environment and heavy metals [

48,

49,

50,

51].

4. Discussion

The main aim of this study is the understanding of the GPs properties in case of substituting 20 wt.% of MK precursor with four industrial wastes. In our previous work, the valorization of same industrial wastes through their incorporation into metakaolin-based geopolymers was addressed [

23]. However, both studies differ in strategy, analytical scope, and resulting material performance. In the previously cited study, industrial wastes were introduced as fillers to the geopolymer fresh paste after alkali activation, while in this study a more integrated approach by substituting 20 wt.% of metakaolin with waste before the geopolymerization process has been adopted. This distinction significantly influenced the microstructure and performance of the final materials. It is worth noting that FT-IR analyses in both cases confirmed geopolymer network formation via red shifts in the Si–O–T (T = Si or Al) stretching bands, yet the degree of shift and secondary peaks varied due to the interaction of the waste with the matrix at different synthesis stages. Moreover, both studies identified high ionic conductivity in chloride- and sulfate-rich waste entrapped in GPs (e.g., electro-filter dust, SW3). However, in this study the conductivity decreased and stabilized by 28 days, suggesting gradual ionic species immobilization. Furthermore, both works confirmed strong alkaline environments (pH > 10.9). Thermogravimetric analysis revealed generally good thermal stability in both studies. Moreover, in the previous study a higher mass loss (up to 23%) for red mud-based geopolymers (namely, 80GP20SW2), was consistent with the GPSW2, which also identified multiple decomposition stages. From the mechanical properties point of view, adding the different wastes as fillers led to superior compressive strengths. Indeed, when the suction dust is added after alkali activation, the resulting geopolymers reached σ

max 58.5 MPa, while a lower value was achieved adding SW1 before alkali-activation, suggesting a slower network consolidation when wastes are introduced pre-activation. These results are similar even for the other geopolymer samples. Leaching tests in both studies emphasized the importance of waste selection. Indeed, both geopolymer samples containing SW1 released hazardous antimony (Sb) levels. However, it seems that the Sb concentration leached from 80GP20SW1 was 25 ppm, while in GPSW1 it was 127.5 ppm. Finally, both studies evaluated antibacterial activity and reported promising results against common bacterial strains (e.g.,

E. coli), attributing the effect to the alkaline pH and the presence of metal cations.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the substitution of 20 wt.% of metakaolin with four different industrial wastes (SW1–SW4) in geopolymer synthesis, evaluating the resulting materials in terms of structural, thermal, mechanical, chemical and antimicrobial properties. The experimental findings demonstrated that geopolymerization occurred successfully in all formulations, as confirmed by FT-IR spectra and stability in boiling and integrity tests. However, introducing wastes prior to alkali activation influenced several performance parameters. Indeed, while the geopolymer networks maintained macroscopic stability and alkaline environments, the ionic conductivity profiles varied, with stabilization occurring by 28 days of ageing. Thermal analysis confirmed the thermal stability of the composites, although samples with SW1 and SW2 exhibited specific decomposition and thermophysical behaviors linked to their chemical composition, including hydrocarbon and heavy metal content. All GPSW (1-4) samples showed a reduction in compressive strength compared to the reference, indicating a possible compromise in their structures when wastes are introduced pre-activation. Leaching tests underlined that geopolymers containing SW1 and SW4 released antimony levels above safe disposal thresholds, designating them as hazardous in terms of landfill criteria. Lastly, antimicrobial testing revealed enhanced resistance against E. coli, particularly in GPSW3, but limited effectiveness against E. faecalis due to its greater resistance to alkaline conditions. Overall, the incorporation of these industrial wastes before geopolymerization presents both opportunities and challenges. While enabling valorization of waste streams and supporting Circular Economy goals, careful selection and characterization of the wastes are essential to ensure the environmental safety and functional performance of the resulting geopolymers.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, M.C. and A.D.; methodology, A.D., F.G., M.G., J.M.S.F; software, A.D., F.G., M.G., J.M.S.F; validation, A.D., M.C., J.M.S.F.; formal analysis, A.D.; investigation, All; resources, M.C.; data curation, A.D., J.M.S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., M.C., J.M.S.F. and S.V.C.; writing—review and editing, A.D., M.C. and S.V.C.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, M.C.; funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank the PRIN 2022 PNRR project #P2022S4TK2 Glass-based Treatments for Sustainable Upcycling of Inorganic Residues for the support on antimicrobial tests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MK |

Metakaolin |

| GP |

Geopolymer |

| SW |

Solid Waste |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FT-IR |

Fourier-Transform Infrared |

| TG/DTA |

Thermogravimetry-differential thermal analysis |

| RT |

Room Temperature |

| IC |

Ionic Conductivity |

| IHD |

Inhibition Halo Diameter |

References

- Arias, A.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T.; Tukker, A.; Cucurachi, S. Advancing Waste Valorization and End-of-Life Strategies in the Bioeconomy through Multi-Criteria Approaches and the Safe and Sustainable by Design Framework. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 207, 114907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obah Edom Tawo; Martin Ifeanyi Mbamalu Advancing Waste Valorization Techniques for Sustainable Industrial Operations and Improved Environmental Safety. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2025, 14, 127–149. [CrossRef]

- Tejaswini, M.S.S.R.; Pathak, P.; Gupta, D.K. Sustainable Approach for Valorization of Solid Wastes as a Secondary Resource through Urban Mining. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 319, 115727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deventer, J.S.J.; Provis, J.L.; Duxson, P.; Brice, D.G. Chemical Research and Climate Change as Drivers in the Commercial Adoption of Alkali Activated Materials. Waste Biomass Valor 2010, 1, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarahy, A.M.; Maged, A.; Eloffy, M.G.; Zahran, M.; Kharbish, S.; Elwakeel, K.Z.; Bhatnagar, A. Geopolymers as Sustainable Eco-Friendly Materials: Classification, Synthesis Routes, and Applications in Wastewater Treatment. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 324, 124631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jwaida, Z.; Dulaimi, A.; Mashaan, N.; Othuman Mydin, M.A. Geopolymers: The Green Alternative to Traditional Materials for Engineering Applications. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Dana, K. Partial Replacement of Metakaolin with Red Ceramic Waste in Geopolymer. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 3473–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, E.; Perumal, P.; Luukkonen, T.; Yliniemi, J.; Ohenoja, K.; Kinnunen, P.; Illikainen, M. Opportunities to Improve Sustainability of Alkali-Activated Materials: A Review of Side-Stream Based Activators. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 286, 125558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiventerä, J.; Perumal, P.; Yliniemi, J.; Illikainen, M. Mine Tailings as a Raw Material in Alkali Activation: A Review. Int J Miner Metall Mater 2020, 27, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisendorf, S.; Pietrulla, F. The Circular Economy and Circular Economic Concepts—a Literature Analysis and Redefinition. Thunderbird Intl Bus Rev 2018, 60, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.B.; Middendorf, B. Geopolymers as an Alternative to Portland Cement: An Overview. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 237, 117455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá Ribeiro, R.A.; Sá Ribeiro, M.G.; Kutyla, G.P.; Kriven, W.M. Amazonian Metakaolin Reactivity for Geopolymer Synthesis. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L. Alkali-Activated Materials. Cement and Concrete Research 2018, 114, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, E.; Minelli, M.; Marchioni, M.C.; Landi, E.; Miccio, F.; Natali Murri, A.; Benito, P.; Vaccari, A.; Medri, V. Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer – Zeolite NaA Composites as CO2 Adsorbents. Applied Clay Science 2023, 237, 106900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P. Geopolymer Precursor Design. In Geopolymers; Elsevier, 2009; pp. 37–49 ISBN 978-1-84569-449-4.

- Albidah, A.; Alghannam, M.; Abbas, H.; Almusallam, T.; Al-Salloum, Y. Characteristics of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Concrete for Different Mix Design Parameters. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 10, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.Z.; Cizer, Ö.; Pontikes, Y.; Heath, A.; Patureau, P.; Bernal, S.A.; Marsh, A.T.M. Advances in Alkali-Activation of Clay Minerals. Cement and Concrete Research 2020, 132, 106050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catauro, M.; Bollino, F.; Dell’Era, A.; Ciprioti, S.V. Pure Al2O3·2SiO2 Synthesized via a Sol-Gel Technique as a Raw Material to Replace Metakaolin: Chemical and Structural Characterization and Thermal Behavior. Ceramics International 2016, 42, 16303–16309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Zhao, Y.; Lv, G.; Duan, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X. Improving Stabilization/Solidification of MSWI Fly Ash with Coal Gangue Based Geopolymer via Increasing Active Calcium Content. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 854, 158594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, L.B.; De Azevedo, A.R.G.; Marvila, M.T.; Pereira, E.C.; Fediuk, R.; Vieira, C.M.F. Durability of Geopolymers with Industrial Waste. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2022, 16, e00839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Poggetto, G.; D’Angelo, A.; Blanco, I.; Piccolella, S.; Leonelli, C.; Catauro, M. FT-IR Study, Thermal Analysis, and Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of a MK-Geopolymer Mortar Using Glass Waste as Fine Aggregate. Polymers 2021, 13, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Vertuccio, L.; Leonelli, C.; Alzeer, M.I.M.; Catauro, M. Entrapment of Acridine Orange in Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer: A Feasibility Study. Polymers 2023, 15, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, V.; D’Angelo, A.; Vertuccio, L.; Catauro, M. Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers Filled with Industrial Wastes: Improvement of Physicochemical Properties through Sustainable Waste Recycling. Polymers 2024, 16, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgarlata, C.; Formia, A.; Siligardi, C.; Ferrari, F.; Leonelli, C. Mine Clay Washing Residues as a Source for Alkali-Activated Binders. Materials 2021, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymer: Chemistry & Applications; 5th ed.; Institut Géopolymère: Saint-Quentin, 2020; ISBN 978-2-9544531-1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Catauro, M.; Viola, V.; D’Amore, A. Mosses on Geopolymers: Preliminary Durability Study and Chemical Characterization of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers Filled with Wood Ash. Polymers 2023, 15, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah (France, Chairman), R. ; Xu-wu (China), A.; Chickos (Usa), J.S.; Leitão (Portugal), M.L.P.; Roux (Spain), M.V.; Torres (México), L.A. Reference Materials for Calorimetry and Differential Thermal Analysis. Thermochimica Acta 1999, 331, 93–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ente Nazionale di Unificazione EN 12457-2:2004; 2004; p. 27;

- Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol 2009.

- Sikora, A.; Zahra, F. Nosocomial Infections. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J. Preparation and Properties of Alkali Activated Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer. Materials 2016, 9, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Lukey, G.C.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Evolution of Gel Structure during Thermal Processing of Na-Geopolymer Gels. Langmuir 2006, 22, 8750–8757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, M.; Prashant, S.; Ralegaonkar, R. Microstructure Properties of Popular Alkali-Activated Pastes Cured in Ambient Temperature. Buildings 2023, 13, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J.; Bryce, D.L. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds; Eighth edition.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2015; ISBN 978-0-470-61637-6. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Aswath, M.U.; Das Biswas, R.; Ranganath, R.V.; Choudhary, H.K.; Kumar, R.; Sahoo, B. Role of Iron in the Enhanced Reactivity of Pulverized Red Mud: Analysis by Mössbauer Spectroscopy and FTIR Spectroscopy. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2019, 11, e00266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaty, F.E.; Nasreddine, H.; Djerbi, A.; Gautron, L.; Marchetti, M.; Quiertant, M.; Metalssi, O.O. Mechanical and Durability Performance of Metakaolin and Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers Compared to Cement Systems. Results in Engineering 2025, 27, 105788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihan, M.A.M.; Onchiri, R.O.; Gathimba, N.; Sabuni, B. Assessing the Durability Performance of Geopolymer Concrete Utilizing Fly Ash and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as Sustainable Binders. Open Ceramics 2024, 20, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, L.; Fernandes, E.; Hotza, D.; Ribeiro, M.J.; Montedo, O.R.K.; Raupp-Pereira, F. Controlling Efflorescence in Geopolymers: A New Approach. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2021, 15, e00740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, M.A.; Zhang, Z.; Walkley, B.; Rodríguez, E.D.; Kirchheim, A.P. Strategies for Control and Mitigation of Efflorescence in Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers. Cement and Concrete Research 2021, 144, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesovnik, A.; Horvat, B. Rapid Immobilisation of Chemical Reactions in Alkali-Activated Materials Using Solely Microwave Irradiation. Minerals 2024, 14, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genua, F.; Giovini, M.; Santoni, E.; Berrettoni, M.; Lancellotti, I.; Leonelli, C. Factors Affecting Consolidation in Geopolymers for Stabilization of Galvanic Sludge. Materials 2025, 18, 3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, Z.; Vance, E.R.; Perera, D.S.; Hanna, J.V.; Griffith, C.S.; Davis, J.; Durce, D. Aqueous Leachability of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers with Molar Ratios of Si/Al = 1.5–4. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2008, 378, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, W.D. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction; Seventh edition.; Wiley: New York, NY, 2007; ISBN 978-0-471-73696-7. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M. Differential Scanning Calorimetry — An Introduction for Practitioners: G. Höhne, W. Hemminger and H.-J. Flammersheim, Springer — Verlag, Berlin, 1996 (ISBN: 3-340-59012-9). 222 Pages, 136 Figures and 13 Tables. Price: DM 178,000 (Hardback). Thermochimica Acta 1997, 303, 117–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; Mallicoat, S.W.; Kriven, W.M.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Understanding the Relationship between Geopolymer Composition, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2005, 269, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, H.; Collado, H.; Droguett, T.; Sánchez, S.; Vesely, M.; Garrido, P.; Palma, S. Factors Affecting the Compressive Strength of Geopolymers: A Review. Minerals 2021, 11, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Iqbal, S.; Soliyeva, M.; Ali, A.; Elboughdiri, N. Advanced Clay-Based Geopolymer: Influence of Structural and Material Parameters on Its Performance and Applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 12443–12471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckwerth, P.H.; Zapata, R.O.; Vivan, R.R.; Tanomaru Filho, M.; Maliza, A.G.A.; Duarte, M.A.H. In Vitro Alkaline pH Resistance of Enterococcus Faecalis. Braz. Dent. J. 2013, 24, 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padan, E.; Bibi, E.; Ito, M.; Krulwich, T.A. Alkaline pH Homeostasis in Bacteria: New Insights. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2005, 1717, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.K.; D’Angelo, A.; Viola, V.; Catauro, M.; Perumal, P. Alternative Construction Materials from Industrial Side Streams: Are They Safe? Energ. Ecol. Environ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Viola, V.; Fiorentino, M.; Dal Poggetto, G.; Blanco, I. Use of Natural Dyes to Color Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Materials. Ceramics International 2024, S0272884224019692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).