Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

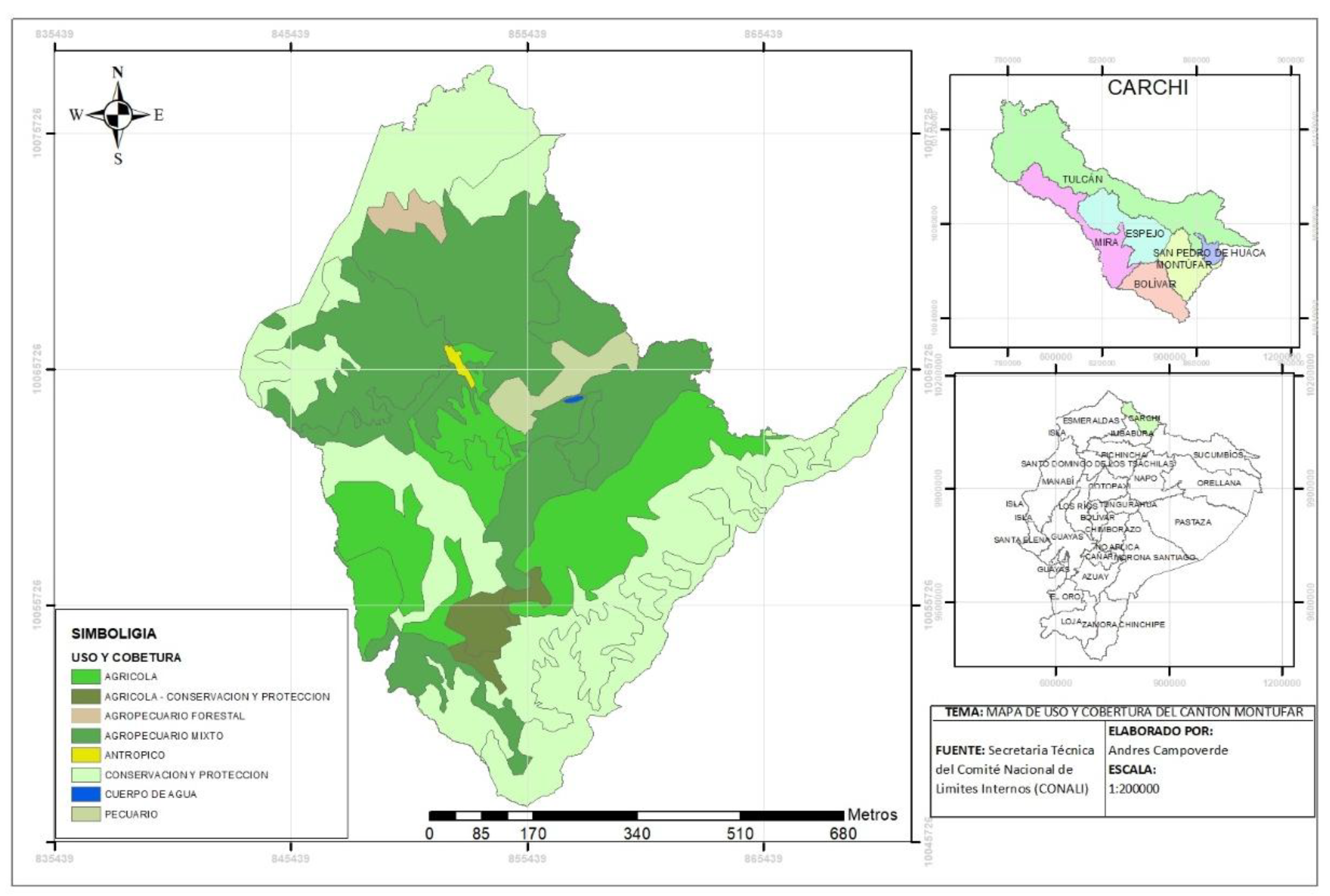

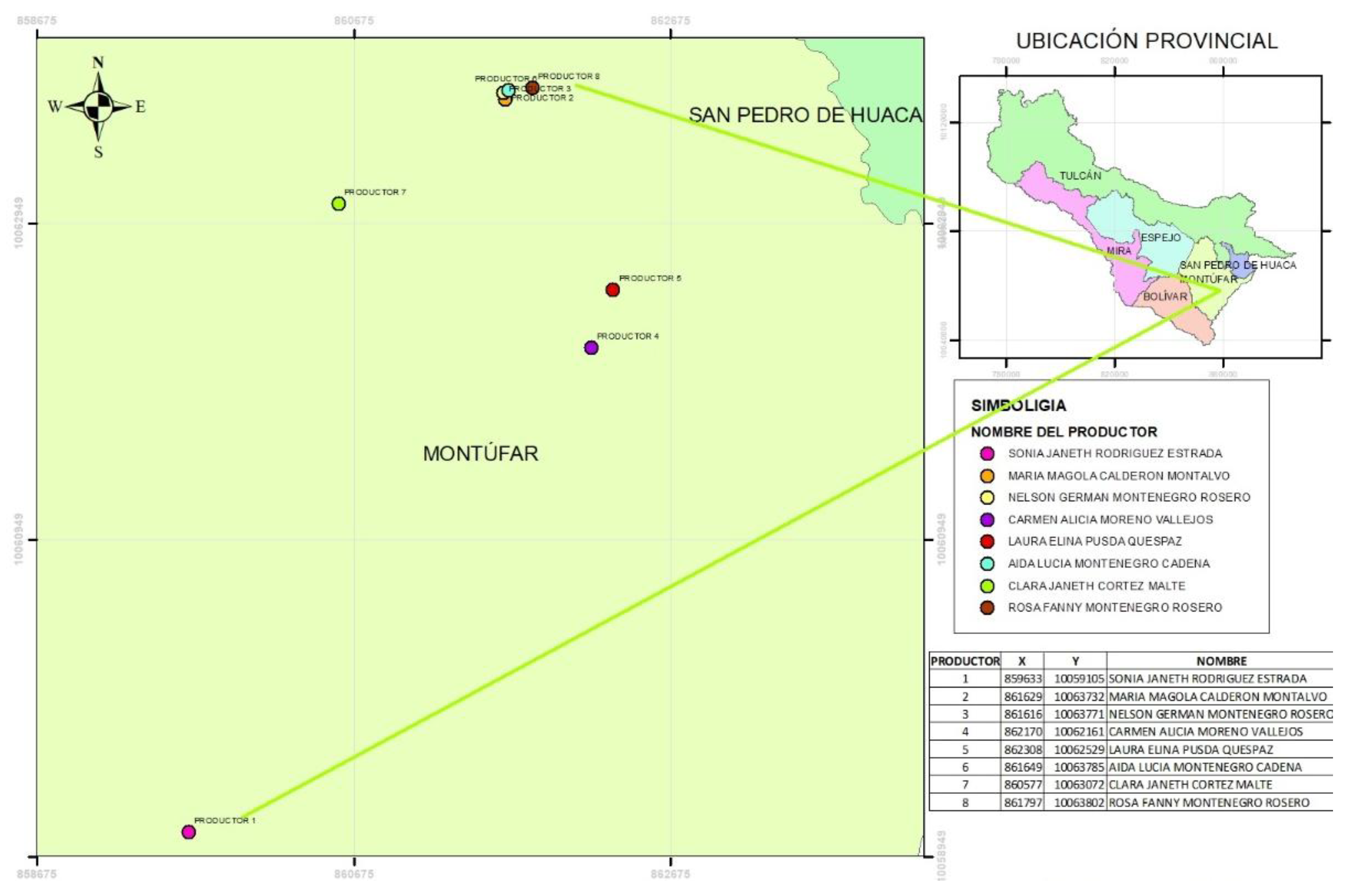

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Approach

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Producers of the PPMA

3.2. Family Aspects of PPMA Producers

3.3. Generalities of Integrated Agroecological Production Systems (IAPS).

3.4. Agroecological Practices of PPMA Producers

3.4.1. Fertilization

3.4.2. Tillage of Land

3.4.3. Irrigation

3.4.5. Management of Pests and Diseases of the “Oxalis tuberosa Mol.” Crop

3.4.6. IAPS Structure

3.4.7. Importance and Characterization of the Cultivation of “Oxalis tuberosa Mol”

3.5. Biocultural Aspects of PPMA Producers

4. Conclusions

References

- Moscoe, L.J.; Emshwiller, E. Farmer Perspectives on OCA (Oxalis Tuberosa; Oxalidaceae) Diversity Conservation: Values and Threats. J Ethnobiol 2016, 36, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarraf, W.; De Carlo, A. In Vitro Biotechnology for Conservation and Sustainable Use of Plant Genetic Resources. Plants 2024, Vol. 13, Page 1897 2024, 13, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Dubey, P.K.; Chaurasia, R.; Dubey, R.K.; Pandey, K.K.; Singh, G.S.; Abhilash, P.C. Domesticating the Undomesticated for Global Food and Nutritional Security: Four Steps. Agronomy 2019, Vol. 9, Page 491 2019, 9, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, P.; Ilbay-Yupa, M.; Cisneros, P.; Ilbay-Yupa, M. How Is Climate Change Adaptation Aid Allocated? A Study of Climate Justice in Ecuador. Desarro Soc 2023, 91–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaconu, A.; Sherwood, S.; Paredes, M.; Berti, P.; López, P.; Cole, D.; Muñoz, F.; Oyarzún, P.; Borja, R.; Aizaga, M.; et al. Promoting Traditional Foods for Human and Environmental Health: Lessons from Agroecology and Indigenous Communities in Ecuador. BMC Nutr 2021, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, N.L.C.; Martínez, M.E.P. Andean Tubers and Local Agricultural Knowledge in Rural Communities from Ecuador and Colombia. Cuad. De Desarro. Rural 2014, 11, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaulen-Luks, S.; Marchant, C.; Olivares, F.; Ibarra, J.T. Biocultural Heritage Construction and Community-Based Tourism in an Important Indigenous Agricultural Heritage System of the Southern Andes. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.; Pathak, H.; Pal, S. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture: Evidence and Predictions. Green Energy Technol. 2020, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puech, T.; Stark, F. Diversification of an Integrated Crop-Livestock System: Agroecological and Food Production Assessment at Farm Scale. Agric Ecosyst Env. 2023, 344, 108300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, C.A.E.; Rosero, G.J.T. Análisis Situacional Del Cantón Montúfar Para La Formulación de Proyectos. Unidad De Prod. Y Difusión Científica Y Académica 2012.

- Mouratiadou, I.; Wezel, A.; Kamilia, K.; Marchetti, A.; Paracchini, M.L.; Bàrberi, P. The Socio-Economic Performance of Agroecology. A Review. Agron Sustain Dev 2024, 44, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, S. Snowball Sampling: Overview. Wiley StatsRef: Stat. Ref. Online 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gargano, G.; Licciardo, F.; Verrascina, M.; Zanetti, B. The Agroecological Approach as a Model for Multifunctional Agriculture and Farming towards the European Green Deal 2030—Some Evidence from the Italian Experience. Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13, Page 2215 2021, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G.R. Media Review: Atlas.Ti Software to Assist With the Qualitative Analysis of Data. J Mix Methods Res 2007, 1, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsall, D.M. Plant Domestication and the Shift to Agriculture in the Andes. Handb. South Am. Archaeol. 2008, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.; Hidalgo, A. Progressivity of Marriage, History and New Paradigms in Family Law La Progresividad Del Matrimonio, Historia y Nuevos Paradigmas En El Del Derecho de Familia. Rev. Fac. De Jurisprud. RFJ 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirui, E.C.; Kidoido, M.M.; Akutse, K.S.; Wanyama, R.; Boni, S.B.; Dubois, T.; Dinssa, F.F.; Mutyambai, D.M. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Agroecological Vegetable Cropping Systems by Smallholder Farmers in Tanzania. Sustain. (Switz. ) 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slijper, T.; Tensi, A.F.; Ang, F.; Ali, B.M.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J. Investigating the Relationship between Knowledge and the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices: The Case of Dutch Arable Farmers. J Clean Prod 2023, 417, 138011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocarico, S.; Rivera, D.; Beck, S.; Obón, C. Agrobiodiversity as a Reservoir of Medicinal Resources: Ethnobotanical Insights from Aymara Communities in the Bolivian Andean Altiplano. Horticulturae 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.; Silva, E.; Hendrickson, J.; Mitchell, P. Time and Technique Assessments of Labor Productivity on Diversified Organic Vegetable Farms Using a Comparative Case Study Approach. J Agric Food Syst Community Dev 2017, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyıldız, B.; Erdal, G.; Çiçek, A.; Ayyıldız, M. Factors Influencing Rural Youth’s Tendency to Stay in Agriculture in Türkiye. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.C.; Bisht, I.S.; Mathur, P.; Fadda, C.; Mittra, S.; Ahlawat, S.P.; Vishwakarma, H.; Yadav, R. Involving Rural Youth in Agroecological Nature-Positive Farming and Culinary Agri-Ecotourism for Sustainable Development: The Indian Scenario. Sustain. (Switz. ) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamino, P.; Millares, C.; Quijada Landaverde, R.; Boren-Alpízar, A. Rural Youth Migration Intentions in Ecuador: The Role of Agricultural Education Programs. Adv. Agric. Dev. 2024, 5, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, J.; Vieli, L.; Ibarra, J.T. Family Farming Systems: An Index-Based Approach to the Drivers of Agroecological Principles in the Southern Andes. Ecol Indic 2023, 154, 110640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawin, K.G.; Tamini, L.D. Land Tenure Differences and Adoption of Agri-Environmental Practices: Evidence from Benin. J Dev Stud 2019, 55, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velten, S.; Leventon, J.; Jager, N.; Newig, J. What Is Sustainable Agriculture? A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2015, Vol. 7, Pages 7833-7865 2015, 7, 7833–7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Toledo, V.M. The Agroecological Revolution in Latin America: Rescuing Nature, Ensuring Food Sovereignty and Empowering Peasants. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintarelli, V.; Radicetti, E.; Allevato, E.; Stazi, S.R.; Haider, G.; Abideen, Z.; Bibi, S.; Jamal, A.; Mancinelli, R. Cover Crops for Sustainable Cropping Systems: A Review. Agriculture 2022, Vol. 12, Page 2076 2022, 12, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Gamage, J.; Jayasinghe, N.; Kodikara, N.; Suraweera, P.; Merah, O. Role of Organic Farming for Achieving Sustainability in Agriculture. Farming Syst. 2023, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.; Aleinikovienė, J.; Butkevičienė, L.M. Innovative Organic Fertilizers and Cover Crops: Perspectives for Sustainable Agriculture in the Era of Climate Change and Organic Agriculture. Agronomy 2024, Vol. 14, Page 2871 2024, 14, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, P.; Carillo, P.; Pathirana, R.; Carimi, F. Management and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources for a Sustainable Agriculture. Plants 2022, Vol. 11, Page 2038 2022, 11, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, E.; Szlatenyi, D.; Csenki, S.; Alrwashdeh, J.; Czako, I.; Láng, V. Farming Practice Variability and Its Implications for Soil Health in Agriculture: A Review. Agriculture 2024, Vol. 14, Page 2114 2024, 14, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Z.; Gu, J.; Li, C.; Li, F.; Li, F. Enhancing Soil Conditions and Maize Yield Efficiency through Rational Conservation Tillage in Aeolian Semi-Arid Regions: A TOPSIS Analysis. Water (Switz. ) 2024, 16, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jug, D.; Jug, I.; Brozović, B.; Šeremešić, S.; Dolijanović, Ž.; Zsembeli, J.; Ujj, A.; Marjanovic, J.; Smutny, V.; Dušková, S.; et al. Conservation Soil Tillage: Bridging Science and Farmer Expectations—An Overview from Southern to Northern Europe. Agriculture 2025, Vol. 15, Page 260 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lu, Q.; Yang, F. The Effects of Farmers’ Adoption Behavior of Soil and Water Conservation Measures on Agricultural Output. Int J Clim Chang Strat. Manag 2020, 12, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iderawumi, A. Problems and Prospects of Subsistence Agriculture among Peasant Farmers in Rural Area. Int. J. World Policy Dev. Stud. 2020, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárceles Rodríguez, B.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Soriano Rodríguez, M.; García-Tejero, I.F.; Gálvez Ruiz, B.; Cuadros Tavira, S. Conservation Agriculture as a Sustainable System for Soil Health: A Review. Soil Syst 2022, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorieva, E.; Livenets, A.; Stelmakh, E. Adaptation of Agriculture to Climate Change: A Scoping Review. Climate 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo C, A.C.; Morillo, C.Y.; Leguizamo, M.M.F.; Morillo C, A.C.; Morillo, C.Y.; Leguizamo, M.M.F. Caracterización Morfológica y Molecular de Oxalis Tuberosa Mol. En El Departamento de Boyacá. Rev Colomb Biotecnol 2019, 21, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Arcot, Y.; Medina, R.F.; Bernal, J.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Akbulut, M.E.S. Integrated Pest Management: An Update on the Sustainability Approach to Crop Protection. ACS Omega 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bist, R.B.; Bist, K.; Poudel, S.; Subedi, D.; Yang, X.; Paneru, B.; Mani, S.; Wang, D.; Chai, L. Sustainable Poultry Farming Practices: A Critical Review of Current Strategies and Future Prospects. Poult Sci 2024, 103, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luziatelli, G.; Alandia, G.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Manrique, I.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Sørensen, M. Ethnobotany of Andean Minor Tuber Crops: Tradition and Innovation—Oca (Oxalis Tuberosa Molina—Oxalidaceae), Mashua (Tropaeolum Tuberosum Ruíz & Pav.—Tropaeoleaceae) and Ulluco (Ullucus Tuberosus Caldas—Basellaceae). Var. Landraces: Cult. Pract. Tradit. Uses: Vol. 2: Undergr. Starchy Crops South Am. Orig. : Prod. Process. Util. Econ. Perspect. 2023, 2, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzzi, S.; Gabellini, S.; Belletti, G.; Marescotti, A.; Bilali, H. El; Strassner, C.; Hassen, T. Ben Agrobiodiversity-Oriented Food Systems between Public Policies and Private Action: A Socio-Ecological Model for Sustainable Territorial Development. Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13, Page 12192 2021, 13, 12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, F.; Baatz, R.; Finger, R. Agroecology for a Sustainable Agriculture and Food System: From Local Solutions to Large-Scale Adoption. Annu Rev Resour Econ. 2023, 15, 351–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloy, S.R.P.; Ortega, R.; Yager, K.; Seimon, A. Traditional Andean Cultivation Systems and Implications for Sustainable Land Use. Acta Hortic 2005, 670, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellon, M.R.; Gotor, E.; Caracciolo, F. Assessing the Effectiveness of Projects Supporting On-Farm Conservation of Native Crops: Evidence From the High Andes of South America. World Dev 2015, 70, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, N. Phenolic Acids: Natural Versatile Molecules with Promising Therapeutic Applications. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- April-Lalonde, G.; Latorre, S.; Paredes, M.; Hurtado, M.F.; Muñoz, F.; Deaconu, A.; Cole, D.C.; Batal, M. Characteristics and Motivations of Consumers of Direct Purchasing Channels and the Perceived Barriers to Alternative Food Purchase: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Ecuadorian Andes. Sustainability 2020, Vol. 12, Page 6923 2020, 12, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo Ponce, N.L. Cultura y Conservación in Situ de Tubérculos Andinos Marginados En Agroecosistemas de Boyacá: Un Análisis de Su Persistencia Desde La Época Prehispánica Hasta El Año 2016. Cuad. De Desarro. Rural 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.; Chirinos, R.; Gálvez Ranilla, L.; Pedreschi, R. Bioactive Potential of Andean Fruits, Seeds, and Tubers. Adv Food Nutr Res 2018, 84, 287–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matallana-Ramirez, L.P.; Whetten, R.W.; Sanchez, G.M.; Payn, K.G. Breeding for Climate Change Resilience: A Case Study of Loblolly Pine (Pinus Taeda L.) in North America. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 606908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, N.J.P.; Condori, B.; Sørensen, M. Traditional Uses, Processes, and Markets: The Case of Oca (Oxalis Tuberosa Molina). Tradit. Prod. Their Process. 2025, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).