Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

18 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

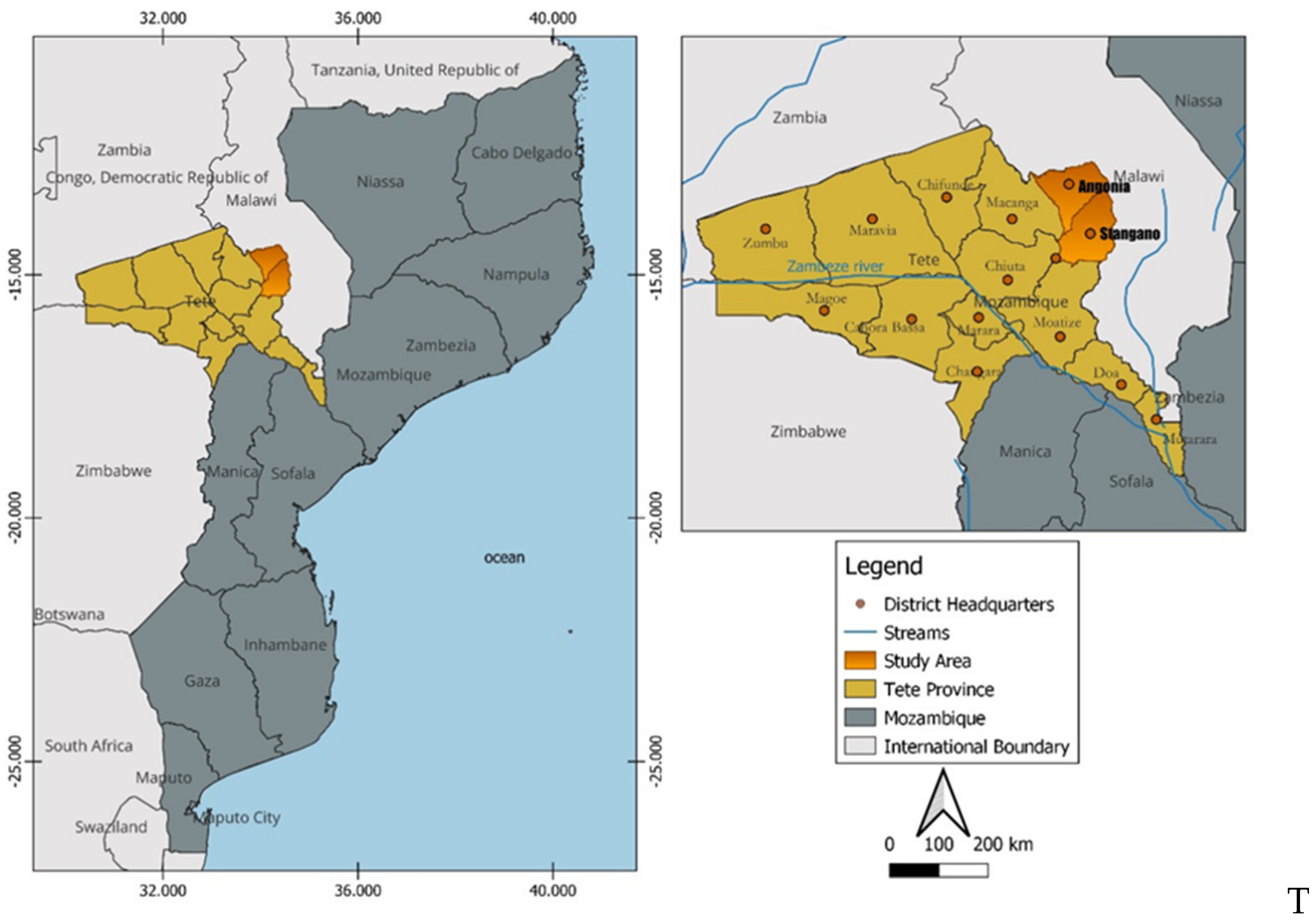

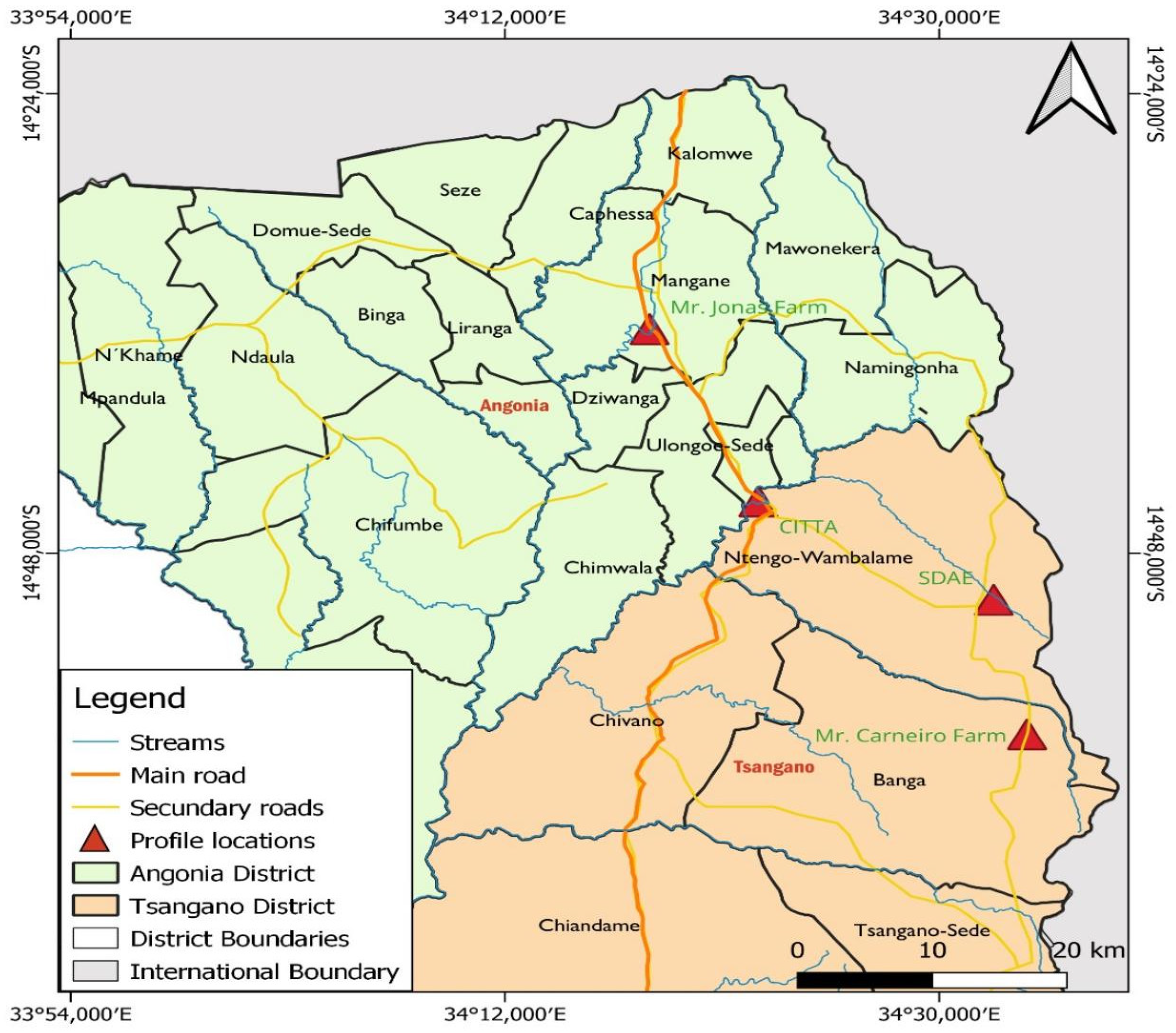

2.1. Description of the Study Areas

2.2. Field work

2.3. Laboratory Soil Analysis

2.4. Data interpretation and Soil classification

2.5. Soil Suitability Assessment

3. Results

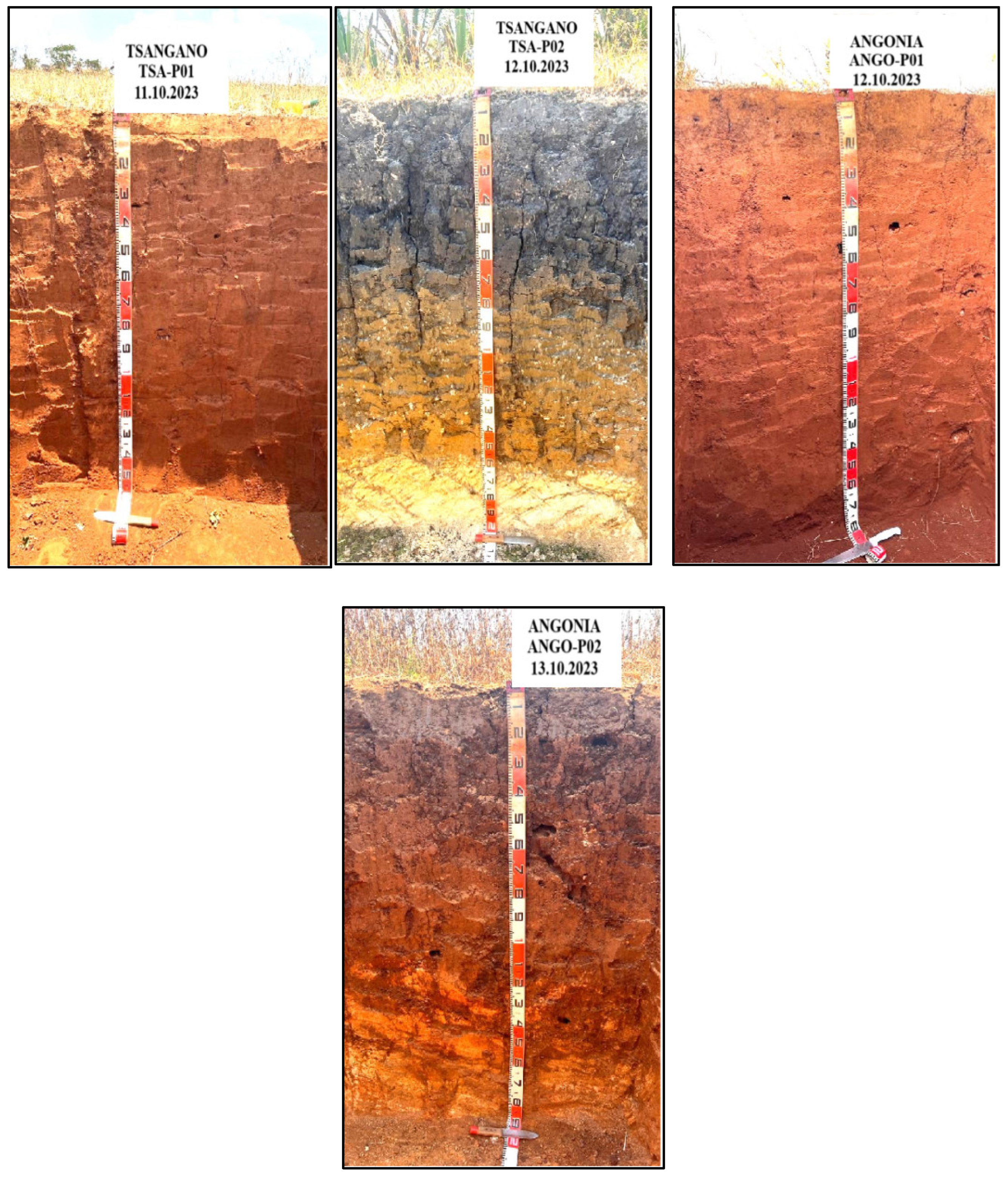

3.1. Soil Morphological Characteristics of the Studied Pedons

3.2. Soil Physical and Chemical Characteristics of the Studied Pedons

3.2.1. Soil Texture, Silt:Clay Ratio

3.2.2. Soil Bulk Density, Porosity, Penetration Resistance and Available Water Capacity (AWC)

3.2.3. Soil pH and Electrical Conductivity (EC)

3.2.4. Soil Organic Carbon (SOC), Total Nitrogen (TN), and Available Phosphorus

3.2.5. Exchangeable Bases, Cation Exchange Capacity, and Nutrient Balance

| Exchangeable bases | CECsoil | CECclay | TEB | Nutrient Balance (Nutrient Ratios) | ||||||||||||

| Ca | Mg | Na | K | PBS | ESP | Ca/Mg | Ca/TEB | Mg/K | % (K/TEB) | |||||||

| Pedons | Horizon | Depth (cm) | cmol (+) kg-1 | |||||||||||||

| TSA-P01 |

Ap |

0 - 8 |

0.65 | 0.98 | 0.06 | 0.4 |

23.0 |

53.96 |

2.09 | 19.3 | 0.55 | 0.66 UF | 0.31 UF | 2.4 F | 3.69 F | |

|

Bt1 |

8 - 45 | 0.83 | 1.03 | 0.05 | 0.25 |

23.5 |

47.00 |

2.16 | 20.0 | 0.46 | 0.81 UF | 0.38 F | 4.2 UF | 2.31 F | ||

|

Bt2 |

45 - 112 | 0.97 | 1.17 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

28.0 |

44.71 |

2.14 | 19.7 | 0.37 | 0.83 UF | 0.45 F | 10.0 UF | 1.10 UF | ||

|

Bt3 |

112 - 155+ | 1.19 | 1.66 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

16.0 |

24.44 |

3.04 | 30.0 | 0.39 | 0.72 UF | 0.39 F | 11.2 UF | 1.48 UF | ||

| TSA-P02 | Ap | 0 - 21 | 7.84 | 2.51 | 0.13 | 1.19 |

32.5 |

64.13 |

11.67 | 103.0 | 1.15 | 3.12 F | 0.67 UF | 2.1 F | 10.50 F | |

| BA1 | 21 - 41 | 4.63 | 1.78 | 0.14 | 0.47 |

22.0 |

39.41 |

7.02 | 64.9 | 1.30 | 2.60 UF | 0.66 UF | 3.7 F | 4.35 F | ||

| BA2k | 41 - 75/91 | 9.17 | 2.55 | 0.08 | 0.75 |

23.5 |

35.05 |

12.54 | 117.0 | 0.75 | 3.60 UF | 0.73 UF | 3.4 F | 7.00 F | ||

| BCgk | 75/91- 155/165 | 13.18 | 3.08 | 0.07 | 0.22 |

22.5 |

31.22 |

16.54 | 153.7 | 0.65 | 4.28 F | 0.80 UF | 13.6 UF | 2.04 F | ||

| CRgk | 155/165 - 200 | 1.5 | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.13 |

11.4 |

135.38 |

2.33 | 23.2 | 0.80 | 2.34 UF | 0.64 UF | 4.6 UF | 1.29 UF | ||

| ANGO-P01 | Ap | 0 - 25/30 | 2.2 | 2.44 | 0.06 | 0.53 |

18.0 |

34.30 |

5.23 |

51.8 | 0.59 | 0.90 UF | 0.42 F | 4.6 UF | 5.25 F | |

| Bt1 | 25/30 - 70 | 1.53 | 1.91 | 0.05 | 0.22 |

25.5 |

35.68 |

3.71 | 34.6 | 0.47 | 0.80 UF | 0.41 F | 8.5 UF | 2.05 F | ||

| Bt2 | 70 - 120 | 1.51 | 2.26 | 0.05 | 0.28 |

17.5 |

19.92 |

4.1 | 39.2 | 0.48 | 0.67 UF | 0.37 F | 8.0 UF | 2.68 F | ||

| Bt3 | 120 - 181 | 1.79 | 2.66 | 0.06 | 0.22 |

24.5 |

30.64 |

4.73 | 44.3 | 0.56 | 0.67 UF | 0.38 F | 11.7 UF | 2.06 F | ||

| ANGO-P02 | Ap | 0 -29 | 2.37 | 1.92 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

18.0 |

23.50 |

4.45 | 42.8 | 0.38 | 1.23 UF | 0.53 UF | 15.0 UF | 1.15 UF | |

| BA | 29 - 50 | 2.39 | 0.2 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

18.5 |

25.06 |

3.1 | 30.7 | 0.40 | 11.95 UF | 0.77 UF | 1.8 F | 1.09 UF | ||

| Bt | 50 - 86/118 | 3.66 | 2.46 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

25.5 |

35.43 |

6.26 | 59.6 | 0.48 | 1.49 UF | 0.58 UF | 24.7 UF | 0.86 UF | ||

| CR | 86/118- 181 | 4.01 | 3.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

8.8 |

41.83 |

7.22 | 66.9 | 0.46 | 1.30 UF | 0.56 UF | 38.0 UF | 0.74 UF | ||

= Very Low,

= Very Low,  = Low,

= Low,  =Moderate,

=Moderate,  =High,

=High,  =Very high; F = favorable; UF = unfavorable, [17,33,43,48,49,56,63].3.2.6. Micronutrient Contents of the Studied Pedons.

=Very high; F = favorable; UF = unfavorable, [17,33,43,48,49,56,63].3.2.6. Micronutrient Contents of the Studied Pedons.3.2.7. Total Elemental Composition and Weathering Indices of the Studied Pedons

3.2.8. Concentrations of Barium (Ba), Zirconium (Zr), Strontium (Sr), and Lead (Pb) in the Studied Pedons

3.2.9. Classification of the Studied Pedons

3.2.10. Suitability Assessment Based on Ecological Requirements of Irish Potato and Field Conditions of the Studied Pedons

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Morphological Characteristics

4.2. Soil Physical and Chemical Characteristics

4.3. Total Elemental Composition and Weathering Indices of the Studied Pedons

4.4. Concentrations of Barium (Ba), Zirconium (Zr), Strontium (Sr), and Lead (Pb) in the Studied Pedons

4.5. Classification of the Studied Pedons

4.6. Suitability Assessment for Irish Potato Cultivation

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demo P, Dominguez S, Cumbi S, Walker T. The potato sub-sector and strategies for sustainable seed production in Mozambique report of a two-week potato sub-sector study conducted from 21 November to 4 December of 2005, Maputo, Moçambique. Maputo; 2006 Mar.

- Amede T, Desta LT, Harris D, Kizito F, Cai X. The Chinyanja triangle in the Zambezi River Basin, southern Africa: status of, and prospects for, agriculture, natural resources management and rural development. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). CGIAR Research Program on …; 2014.

- António J. Análise da Cadeia Produtiva de Batata Reno na Região do Vale do Zambeze (Moçambique): Estrutura de Produção, Governança e Coordenação. 2009;1–229.

- Schelling N. Horticulture and Potato Market Study in Mozambique [Internet]. Pretoria; 2015 [cited 2022 May 1]. Available from: http://agriprofocus.com/upload/HorticultureandPotatoMarketStudyinMozambique1417448632.pdf.

- Harahagazwe D, Condori B, Barreda C, Bararyenya A, Byarugaba AA, Kude DA, et al. How big is the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) yield gap in Sub-Saharan Africa and why? A participatory approach. Open Agric. 2018 Jan 1;3(1):180–9. [CrossRef]

- Niek Schelling, Schelling N. Horticulture and Potato Market Study in Mozambique [Internet]. Pretoria; 2015 [cited 2022 May 1]. Available from: http://agriprofocus.com/upload/HorticultureandPotatoMarketStudyinMozambique1417448632.pdf.

- Karlen DL, Andrews SS, Doran JW. Soil quality: Current concepts and applications. 2001;

- Estrada-Herrera IR, Hidalgo-Moreno C, Guzmán-Plazola R, Almaraz Suárez JJ, Navarro-Garza H, Etchevers-Barra JD. Soil quality indicators to evaluate soil fertility. Agrociencia. 2017;51(8):813–31.

- Hatfield JL. Soil degradation, land use, and sustainability. Convergence of Food Security, Energy Security and Sustainable Agriculture. 2014;61–74.

- Vlek PLG. The incipient threat of land degradation. Journal of the Indian Society of Soil Science. 2008;56(1):1–13.

- Zhang J. Soil Environmental Deterioration and Ecological Rehabilitation. Study of Ecological Engineering of Human Settlements. 2020;41–82.

- Osman KT, Osman KT. Soil resources and soil degradation. Soils: principles, properties and management. 2013;175–213.

- Veum KS, Goyne KW, Kremer RJ, Miles RJ, Sudduth KA. Biological indicators of soil quality and soil organic matter characteristics in an agricultural management continuum. Biogeochemistry. 2014;117:81–99. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Nie M, Powell JR, Bissett A, Pendall E. Soil physico-chemical properties are critical for predicting carbon storage and nutrient availability across Australia. Environmental Research Letters. 2020;15(9):094088.

- Manikandan K, Kannan P, Sankar M, Vishnu G. Concepts on land evaluation. Earth Science India (Popular Issue VI (I)). 2013;20–6.

- Rossiter DG. Land evaluation: Towards a revised framework. Geoderma. 2009 Apr;148(3):428–9.

- Landon JR. Booker Tropical Soil Manual: A handbook for soil survey and agricultural land evaluation in the tropics and subtropics. Paperback. J. R. Landon, editor. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013. 531 p.

- FAO. A framework for land evaluation. Vol. 32, Soil Bulletin. Rome: FAO Rome; 1976.

- Sys C, Van Ranst E, Debaveye J. Land Evaluation. Part I: principles in land evaluation and crop production calculations. Agricultural publication. 1991;(7).

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy. 13th ed. 2022. 410 p.

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World reference base for soil resources 2014, update 2015 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. 106th ed. FAO, editor. Vol. 106. Rome; 2015. 203 p.

- DNCI. Plano Operacional Da Comercialização Agrícola, Tete. Ministério Da Indústria E Comércio Direcção Nacional Do Comércio Interno. Direcção Nacional Do Comércio Interno (DNCI). Maputo; 2018.

- MEF M de E e F. Avaliação Ambiental Estratégica, Plano Multissectorial, Plano Especial de Ordenamento Territorial do Vale do Zambeze e Modelo Digital de Suporte a Decisões. PERFIL AMBIENTAL DISTRITAL DE TSANGANO. Maputo; 2015 Dec.

- MITADER. PERFIL AMBIENTAL DISTRITAL DE ANGÓNIA [Dezembro, 2015] Plano Multissectorial, Plano Especial de Ordenamento Territorial do Vale do Zambeze e Modelo Digital de Suporte a Decisões MINISTÉRIO DA ECONOMIA E FINANÇAS AGÊNCIA DE DESENVOLVIMENTO DO VALE DO ZAMBE. 2005th ed. MITADR, editor. Maputo: MEF; 2015. 97 p.

- JICA JICA. The study on the Integrated Development Master Plan of the Angonia Region in the Republic of Mozambique. Final Report. Master Plan Report. [Internet]. October, 2021. 2001 Oct [cited 2022 Jun 19]. Available from: https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/11668704.pdf.

- Nkoka F, Veldwisch GJA, Bolding JA. Organisational modalities of farmer-led irrigation development in Tsangano District, Mozambique. Water Alternatives. 2014;7(2):414–33.

- Maereka EK, Makate C, Chataika BY, Mango N, Zulu RM, Munthali G, et al. Estimation and characterization of bean seed demand in Angonia district of Mozambique. 2015;

- Voortman R. L, Spiers F. B. Landscape Ecological Survey And Land Evaluation, For Rural Development Planning, Angonia District, Tete Province. Climate, agro-climatic zones and agro-climatic suitability Vol.5. Instituto Nacional de Investigacao Agronomica. Maputo; 1986 Mar.

- Amerling R, Winchester JF, Ronco C. Guidelines for Soil Description. Vol. 25, Blood Purification. 2006. 36–38 p.

- Kipfer BA. Munsell Soil Color Chart. Revised ed. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. Windsor: MACBETH; 1994. 29 p.

- Klute A. Methods of soil analysis. Part 1. Physical and mineralogical methods. 1986.

- Cho SE. Effects of spatial variability of soil properties on slope stability. Eng Geol. 2007;92(3–4):97–109. [CrossRef]

- Hazelton P, Murphy B. INTERPRETING SOIL TEST RESULTS: What do the numbers mean? 3rd ed. Clayton South, Autralia; 2016. 186 p.

- Moraes MT de, Debiasi H, Carlesso R, Franchini JC, Silva VR da. Critical limits of soil penetration resistance in a rhodic Eutrudox. Rev Bras Cienc Solo. 2014;38:288–98. [CrossRef]

- Okalebo JR, Gathua WK, Woomer LP. LABORATORY METHODS OF SOIL AND PLANT ANALYSIS: A Working Manual. Second. Nairobi: SACRED Africa; 2002. 131 p.

- Estefan G, Sommer R, Ryan J. Methods of Soil, Plant, and Water Analysis: A manual for the West Asia and North. 2013. 1–243 p.

- ASTM. Standard Test Methods for Moisture, Ash, and Organic Matter of Peat and Other Organic Soils. In: American Society for Testing and Materials. D 2974-8. Philadelphia; 1987. p. 3.

- Rayment GE, Lyons DJ. Soil chemical methods: Australasia. Vol. 3. CSIRO publishing; 2011.

- Parkinson JA, Allen SE. A wet oxidation procedure suitable for the determination of nitrogen and mineral nutrients in biological material. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1975;6(1):1–11. [CrossRef]

- Mehlich A. Mehlich 3 soil test extractant: A modification of Mehlich 2 extractant. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1984;15(12):1409–16. [CrossRef]

- Baize D. Soil science analyses: a guide to current use. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1993. 187 p.

- Tiecher T, Gatiboni L, Rheinheimer dos Santos D, Alberto Bissani C, Posselt Martins A, Gianello C, et al. Base saturation is an inadequate term for Soil Science. Brasilian Journal of Soil Science [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 3];6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.36783/18069657rbcs20220125. [CrossRef]

- Nile CB. The nature and properties of soils. Nile CB, editor. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1984. 780 p.

- Kalala AM, Msanya BM, Amuri NA, Semoka JM. Pedological characterization of some typical alluvial soils of Kilombero District, Tanzania. 2017; [CrossRef]

- Sys C, Van Ranst E, Debaveye J. Land evaluation. Part 2: Methods in land evaluation. Agricultural publications; 1991.

- Iliquín Trigoso D, Salas López R, Rojas Briceño NB, Silva López JO, Gómez Fernández D, Oliva M, et al. Land suitability analysis for potato crop in the Jucusbamba and Tincas Microwatersheds (Amazonas, NW Peru): AHP and RS–GIS approach. Agronomy. 2020;10(12):1898.

- Asfaw M, Asfaw D. Agricultural Land Suitability Analysis for Potato Crop by Using Gis and Remote Sensing Technology, in the Case of Amhara Region, Ethiopia. 2017;7(11). Available from: www.iiste.org.

- Enang RK, Yerima BPK, Kome GK. Soil physico-chemical properties and land suitability evaluation for maize (Zea mays), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) and Irish potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) in tephra soils of the western slopes of mount Kupe (Cameroon). Afr J Agric Res. 2016;11(45):4571–83.

- Mugo JN, Karanja NN, Gachene CK, Dittert K, Nyawade SO, Schulte-Geldermann E. Assessment of soil fertility and potato crop nutrient status in central and eastern highlands of Kenya. Sci Rep. 2020 Dec 1;10(1). [CrossRef]

- Peverill KI, Sparrow LA, Reuter KI. Soil analysis: An interpretation manual. Eds. Peverill KI, Sparrow LA, Reuter KI, editors. Collingwood: SCIROPublishing; 1999. 369 p.

- Buol SW, Southard RJ, Graham RC, McDaniel PA. Soil Genesis and Classification. 6th ed. Madison Wis, Buol SW, Hole FD, McCracken RJ, editors. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. 543 p.

- Wang L, He Z, Zhao W, Wang C, Ma D. Fine soil texture is conducive to crop productivity and nitrogen retention in irrigated cropland in a desert-oasis ecotone, Northwest China. Agronomy. 2022;12(7):1509. [CrossRef]

- NRCS U. Soil health. United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2019;

- Lardy JM, DeSutter TM, Daigh ALM, Meehan MA, Staricka JA. Effects of soil bulk density and water content on penetration resistance. Agricultural & Environmental Letters. 2022;7(2):e20096. [CrossRef]

- Msanya BM, Kimaro DN, Kimbi GG, Kileo EP, Mbogoni JJDJ. SOILS AND LAND RESOURCES OF MOROGORO RURAL AND URBAN DISTRICTS ISBN 9987 605 29 X VOLUME 4 LAND RESOURCES INVENTORY AND SUITABILITY ASSESSMENT FOR THE MAJOR LAND USE TYPES IN MOROGORO URBAN DISTRICT, TANZANIA. Morogoro; 2001.

- Msanya BM, Kimaro DN, Kimbi GG, Kileo EP, Mbogoni JJDJ. Land resources inventory and suitability assessment for the major land use types in Morogoro Urban District, Tanzania. Soils and Land Resources of Morogoro Rural and Urban Districts. Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania. Vol. 4. Morogoro, Tanzania; 2001 May.

- Kononova MM. Soil organic matter: its nature, its role in soil formation and in soil fertility. Elsevier; 2013.

- Lehmann J, Kleber M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature. 2015;528(7580):60–8. [CrossRef]

- Heckman JR. Below Optimum Optimum Above Optimum Soil Fertility Test Interpretation Phosphorus, Potassium, Magnesium, and Calcium [Internet]. 2004. Available from: www.rce.rutgers.edu.

- Mumbach GL, Oliveira DA de, Warmling MI, Gatiboni LC. Phosphorus extraction by Mehlich 1, Mehlich 3 and Anion Exchange Resin in soils with different clay contents. Revista Ceres. 2018;65:546–54.

- Savoy H. Interpreting Mehlich 1 and 3 soil test extractant results for P and K in Tennessee. University of Tennessee, Institute of Agriculture. 2009;

- da Silva RJAB, da Silva YJAB, van Straaten P, do Nascimento CWA, Biondi CM, da Silva YJAB, et al. Influence of parent material on soil chemical characteristics in a semi-arid tropical region of Northeast Brazil. Environ Monit Assess. 2022 May 1;194(5). [CrossRef]

- Maria RM, Yost R. A survey of soil fertility status of four agroecological zones of Mozambique. Soil Sci [Internet]. 2006 Nov [cited 2022 Jul 20];171(11):902–14. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/soilsci/Fulltext/2006/11000/A_SURVEY_OF_SOIL_FERTILITY_STATUS_OF_FOUR.8.aspx. [CrossRef]

- Havlin JL. Soil: Fertility and nutrient management. In: Landscape and land capacity. CRC Press; 2020. p. 251–65.

- Soil and Plant Analysis Council. Soil analysis handbook of reference methods. CRC press; 1992. 265 p.

- Andreasen R, Thomsen E. Strontium is released rapidly from agricultural lime–implications for provenance and migration studies. Front Ecol Evol. 2021;8:588422. [CrossRef]

- Gregorauskienė V, Kadunas V. Vertical distribution patterns of trace and major elements within soil profile in Lithuania. Geological Quarterly. 2006;50(2):229–37.

- Shahid M, Ferrand E, Schreck E, Dumat C. Behavior and impact of zirconium in the soil–plant system: plant uptake and phytotoxicity. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 221. 2012;107–27.

- Kabata-Pendias A. Trace elements in soils and plants. CRC press; 2000.

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to soil taxonomy. Soil Conservation Service. Twelfth Ed. 2014;12:410.

- Voortman RL, Spires B, FAO. Landscape Ecological Survey And Land Evaluation, For Rural Development Planning, Angonia District, Tete Province. Land evaluation, land suitability and recommended land use. Instituto de Investigacao Agraria de Mocambique. Vol. 6. Maputo; 1986 Mar.

- Martinho CA, Lung C, Roda FA, Pereira R, Mofate OA, Naconha AE. Manual de maneio da cultura de batata reno. 2017;1–26.

- Dinssa B, Elias E. Characterization and classification of soils of bako tibe district, west shewa, Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2021;7(11). [CrossRef]

- Mohamed SH, Msanya BM, Tindwa HJ, Semu E. Pedological characterization and classification of selected soils of morogoro and mbeya regions of Tanzania. International Journal of Natural Resource Ecology and Management. 2021;6(2):79–92. [CrossRef]

- Uwingabire S, Msanya BM, Mtakwa PW, Uwitonze P, Sirikare S. Pedological Characterization of soils developed on gneissic granites in the Congo Nile Watershed Divide and Central Plateau zones, Rwanda. Int J Curr Res. 2016;(9):39489–501.

- Blanco-Canqui H, Stone LR, Schlegel AJ, Lyon DJ, Vigil MF, Mikha MM, et al. No-till induced increase in organic carbon reduces maximum bulk density of soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 2009;73(6):1871–9. [CrossRef]

- Chichongue O, van Tol J, Ceronio G, Du Preez C. Effects of tillage systems and cropping patterns on soil physical properties in Mozambique. Agriculture. 2020;10(10):448.

- Takele L, Chimdi A, Abebaw A. Dynamics of soil fertility as influenced by different land use systems and soil depth in West Showa Zone, Gindeberet District, Ethiopia. Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2014;3(6):489–94.

- Hailu AH, Kibret K, Gebrekidan H. Characterization and classification of soils of kabe subwatershed in south wollo zone, northeastern Ethiopia. African Journal of Soil Science. 2015;3(7):134–46.

- Pereira MJSL, Esteves da Silva J. Environmental Stressors of Mozambique Soil Quality. Environments. 2024;11(6):125.

- Dessalegn D, Beyene S, Ram N, Walley F, Gala TS. Effects of topography and land use on soil characteristics along the toposequence of Ele watershed in southern Ethiopia. Catena (Amst). 2014;115:47–54. [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu Y, Gebrekidan H, Beyene S. Pedological characteristics and classification of soils along landscapes at Abobo, southwestern lowlands of Ethiopia. Journal of Soil Science and Environmental Management. 2014;5(6):72–82.

- Uwingabire S, Msanya B, Mtakwa PW, Uwitonze P, Sirikare S. PEDOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION OF SOILS DEVELOPED ON GNEISSIC CONGO NILE WATERSHED DIVIDE AND CENTRAL PLATEAU. 2016 Sep;8(09):39489–501. Available from: http://www.journalcra.com.

- Gebrehanna B, Beyene S, Abera G. Impact of Topography on Soil Properties in Delboatwaro Subwatershed, Southern Ethiopia. Asian Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2022;(8):4. [CrossRef]

- Condron LM, Sinaj S, McDowell RW, Dudler-Guela J, Scott JT, Metherell AK. Influence of long-term irrigation on the distribution and availability of soil phosphorus under permanent pasture. Soil Research. 2006;44(2):127–33. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz C, Pierotti S, Molina MG, Bosch-Serra ÀD. Soil Fertility and Phosphorus Leaching in Irrigated Calcareous Soils of the Mediterranean Region. Environ Monit Assess. 2023;195(11):1376. [CrossRef]

- Solly EF, Weber V, Zimmermann S, Walthert L, Hagedorn F, Schmidt MWI. A critical evaluation of the relationship between the effective cation exchange capacity and soil organic carbon content in Swiss forest soils. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 2020;3:98. [CrossRef]

- Kumaragamage D, Warren J, Spiers G. Soil Chemistry. Digging into Canadian Soils. 2021;

- Tomašic M, Zgorelec Ž, Jurišic A, Kisic I. Cation exchange capacity of dominant soil types in the Republic of Croatia. Journal of Central European Agriculture. 2013; [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Mao Q, Gilliam FS, Luo Y, Mo J. Nitrogen deposition contributes to soil acidification in tropical ecosystems. Glob Chang Biol [Internet]. 2014 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Mar 13];20(12):3790–801. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/gcb.12665. [CrossRef]

- Niu G, Wang R, Hasi M, Wang Y, Geng Q, Wang C, et al. Availability of soil base cations and micronutrients along soil profile after 13-year nitrogen and water addition in a semi-arid grassland. Biogeochemistry [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Mar 13];152(2–3):223–36. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10533-020-00749-5. [CrossRef]

- Hodges SC. Soil Fertility Basics. Soil Science Extension North Carolina State University. [Internet]. Academic Press; 2007 [cited 2024 Dec 6]. 75 p. Available from: http//.plantstress.com/Articles/min_deficiency_i/soil_fertility.pdf.

- Dhaliwal SS, Sharma V, Kaur J, Shukla AK, Hossain A, Abdel-Hafez SH, et al. The Pedospheric Variation of DTPA-Extractable Zn, Fe, Mn, Cu and Other Physicochemical Characteristics in Major Soil Orders in Existing Land Use Systems of Punjab, India. Sustainability 2022, Vol 14, Page 29 [Internet]. 2021 Dec 21 [cited 2024 Dec 8];14(1):29. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/1/29/htm. [CrossRef]

- Liang B, Han G, Zhao Y. Zinc isotopic signature in tropical soils: A review. Science of the Total Environment. 2022;820:153303. [CrossRef]

- Walna B, Spychalski W, Ibragimow A. Fractionation of iron and manganese in the horizons of a nutrient-poor forest soil profile using the sequential extraction method. Pol J Environ Stud. 2010;19(5):1029–37.

- Uwitonze P, Msanya BM, Mtakwa PW, Uwingabire S, Sirikare S. Pedological Characterization of Soils Developed from Volcanic Parent Materials of Northern Province of Rwanda. Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2016;(6):225–36. [CrossRef]

- Abdoulaye ODM, Yao BK, Ahmed AM, Adouby K, Abro DMK, Drogui P. Mineralogical and morphological characterization of a clay from Niger. Jour Mater Environ Sci. 2019;10(7):582–9.

- Nguetnkam JP, Kamga R, Villiéras F, Ekodeck GE, Yvon J. Altération différentielle du granite en zone tropicale. Exemple de deux séquences étudiées au Cameroun (Afrique Centrale). Comptes Rendus Géoscience. 2008;340(7):451–61.

- Miranda-Trevino JC, Coles CA. Kaolinite properties, structure and influence of metal retention on pH. Appl Clay Sci. 2003;23(1–4):133–9. [CrossRef]

- Buol SW, Southard RJ, Graham RC, McDaniel PA. Soil genesis and classification. 6th ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Jihn Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011. 531 p.

- Msanya B, Munishi J, Amuri N, Semu E, Mhoro L, Malley Z. Morphology, Genesis, Physico-chemical Properties, Classification and Potential of Soils Derived from Volcanic Parent Materials in Selected Districts of Mbeya Region, Tanzania. Int J Plant Soil Sci. 2016 Jan 10;10(4):1–19. [CrossRef]

- Khawmee K, Suddhiprakarn A, Kheoruenromne I, Singh B. Surface charge properties of kaolinite from Thai soils. Geoderma. 2013;192:120–31. [CrossRef]

- Abaga NOZ, Nfoumou V, M’voubou M. Influence of the parent rock nature on the mineralogical and geochemical composition of ferralsols used for sedentary agriculture in the Paleoproterozoic Franceville sub-basin (Gabon). Int J Biol Chem Sci. 2023;17(4):1778–89. [CrossRef]

- Ofem KI, John K, Ediene VF, Kefas PK, Ede AM, Ezeaku VI, et al. Pedological data for the study of soils developed over a limestone bed in a humid tropical environment. Environ Monit Assess. 2023;195(5):628. [CrossRef]

- Anda M, Chittleborough DJ, Fitzpatrick RW. Assessing parent material uniformity of a red and black soil complex in the landscapes. Catena (Amst). 2009;78(2):142–53. [CrossRef]

- Kabała C, Szerszeń L. Profile distributions of lead, zinc, and copper in Dystric Cambisols developed from granite and gneiss of the Sudetes Mountains, Poland. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2002;138:307–17. [CrossRef]

- Teutsch N, Erel Y, Halicz L, Banin A. Distribution of natural and anthropogenic lead in Mediterranean soils. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2001;65(17):2853–64. [CrossRef]

- Nieder R, Benbi DK, Reichl FX, Nieder R, Benbi DK, Reichl FX. Role of potentially toxic elements in soils. Soil components and human health. 2018;375–450.

- Zhang J, Wu Y, Xu Y. Factors Affecting the Levels of Pb and Cd Heavy Metals in Contaminated Farmland Soils. 2016.

| District | Tsangano | Angónia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village | Ligowe | Ntengo-Wambalame | Rinze | Ulónguè |

| Location | Mr. M. Carneiro’s Farm | SDAE farm | Mr. Jonas’ farm | CITTA farm |

| Attributes | Description | |||

| Pedon symbol | TSA-P01 | TSA-P02 | ANGO-P01 | ANGO-P02 |

| Agro-Ecological Zone 10 | high rainfall zone | high rainfall zone | high rainfall zone | high rainfall zone |

| Coordinates | 14° 52′ 47″ S/ 34° 21′ 30″ E | 14° 50′ 25″ S/ 34° 32′ 16″ E | 14° 36′ 17″ S/ 34° 18′ 0″ E | 14° 45′ 17″ S/ 34° 22′ 30″ E |

| Altitudes (m.a.s.l.) | 1427 | 1340 | 1260 | 1200 |

| Landform | hilly | plain | hilly | hilly |

| Geology/Lithology | Precambrian Meso- and Neoproterozoic geological eons dominated by quartz-feldspathic gneiss and amphibolic gneiss |

Precambrian Meso- and Neoproterozoic geological eons dominated by quartz-feldspathic gneiss and amphibolic gneiss |

Precambrian Meso- and Neoproterozoic geological eons dominated by basic rocks, migmatitic gneisses and granulites | Precambrian Meso- and Neoproterozoic geological eons dominated by basic rocks, migmatitic gneisses and granulites |

| Slope gradient (%) | 16 | 2-5 | 16 | 12 |

| Land use/vegetation | Agriculture but currently under grazing and fallow for 4 years | Agriculture and area under maize, conservation strategy (matuto) | Agriculture for maize, soybean, potatoes, vegetables | Agriculture and area under fallow for 4 years |

| Natural vegetation | Various grasses | Eucalyptus, mangoes, sisal boundary, legume shrubs, vinegar grass, Mexican sunflower (Tithonia diversifolia) | Mangoes, legumes, shrubs | Various grasses |

| Natural drainage | well to excessively well drained | well to moderately well drained | well drained | well drained |

| Flooding | None | None | None | None |

| Erosion | water, slight sheet (interill) | water, slight sheet (interill) | water, slight sheet (interill) | water, slight sheet |

| Annual rainfall (mm) | 1000 - 1200 | 1000 - 1200 | 800 - 1200 | 800 - 1200 |

| Soil moisture regime (SMR) | ustic | aquic | ustic | ustic |

| Mean annual temperature (oC) | 15 - 20 | 15 - 20 | 15 - 22 | 15 - 22 |

| Soil temperature regime (STR) | thermic | thermic | thermic | thermic |

| Location | Pedon | Horizon | Depth (cm) | Dry colour1) | Moist colour2) | Consistence3) | Structure4) | Cutans5 | Slickensides6 | Pores7) | Roots8) | Horizon boundary9) |

| Ligowe | TSA-P01 | Ap | 0 – 8 | b(7.5YR4/4) | db(2.5YR3/3) | sh, fi, ss& sp | w-m&c,sbk | - | - | c&f | f-c&f-m | c&w |

| Bt1 | 8 – 45 | rd(5YR4/4) | drb(5YR3/4) | vha, fi, spl | w-m, m&c, sbk | m-f, cs | - | c&f | f-f | gd&s | ||

| Bt2 | 45 - 112 | yr(5Y4/6) | drb(5YR3/4) | vha, vfr, spl | m-m, sbk | m-f, cs | - | c&f | f-f | gd&s | ||

| Bt3 | 112 - 155+ | yr(5YR5/8) | yr(5 YR4/6) | sha, vfr, spl | m, f&m, sbk | m-f&m, cs | - | c&f | vf-f | NA | ||

| Ntengo-wa-mbalame | TSA-P02 | Ap | 0 – 21 | vdg(5YR3/1) | bl(5YR2.5/1) | h, fr, spl | m&m, sbk | - | - | m-f&m, f-c | m-f, c-m&f-c | c&s |

| BA1 | 21 – 41 | bl(7.5YR2.5/1) | bl(2.5YR2.5/1) | eha, fr, vst&vpl | m, m&c, ab-sbk | - | mds | c-f&m | c-f&fm | c&s | ||

| BA2k | 41 - 75/91 | bl(2.5YR2.5/1) | bl(5YR2.5/1) | eha, fi, vst&vpl | m-s, m&c, ab-sbk | - | mds | c-f&m | f-f | c&w | ||

| BCgk | 79/91 - 155/165 | g(7.5YR6/1) | lob(2.5Y5/4) | vha, fi, vst&vpl | m-m&c, ab&sbk | - | - | f-f&m | vf-f | a&w | ||

| CRgk | 155/165 - 200 | w(5Y2/1) | oy(2.5Y6/6) | sha, fr, ns&np | sg | - | - | m-f, m&c-m | n | NA | ||

| Rinze | ANGO-P01 | Ap | 0 - 25/30 | db(7.5YR3/4) | db(7.5YR3/2) | sha, vfr, ss&sp | w-f&m, sbk | - | - | m-f&m | c-f | cw |

| Bt1 | 25/30 - 70 | b(7.5YR4/4) | vdb(7.5YR2.5/3) | sha, vfr, sp | m-m, sbk | f-vf, c | - | m-f&m | f-f | d&s | ||

| Bt2 | 70 - 120 | r(2.5YR4/6) | dr(2.5YR3/6) | sha, vfr, sp | s-f&m, sbk | m-f&m, cs | - | m-f&m | f-vf | d&s | ||

| Bt3 | 120 - 181 | r(2.5YR4/8) | r(2.5 YR4/6) | ha, fi, sp | s-f&m, sbk | m-vf, cs | - | m-f&m | vf-vf | NA | ||

| CITTA | ANGO-P02 | Ap | 0 – 29 | drb(5YR3/2) | bl(5YR2.5/1) | vha, vfr, ss&sp | m-m&c, sbk | - | - | f-m&m-f | m-f | c&s |

| BA | 29 – 50 | drb(5YR3/3) | drb(5YR3/2) | vha, fr, spl | m-m&c, sbk | - | - | m-f&c-m | c-f | c&s | ||

| Bt | 50 - 86/118 | drb(5YR3/4) | drb(5YR3/3) | vha, fr, spl | w-m&c, sbk | m-f, cs | - | m-f&c-m | f-f | c&w | ||

| CR | 86/118-181 | sb(7.5YR5/8) | sb(7.5 YR5/6) | so, vfr, ns&np | sg | - | - | m-f, m-m&c | n | NA |

|

Pedon |

Horizon | Depth (cm) | Texture | Silt/clay ratio |

Bulk density (kg m-3) |

Porosity (%) | AWC (mm m-1) | Penetration resistance (MPa) | |||

| Clay % | Silt % | Sand % | Texture class | ||||||||

|

TSA-P01 |

Ap | 0 - 8 | 34 | 10 | 56 | SCL | 0.29 | 1.58 | 37.31 | 84.9 | 1.75 |

| Bt1 | 8 - 45 | 42 | 10 | 48 | SC | 0.23 | 1.55 | 38.71 | 110.5 | 1.64 | |

| Bt2 | 45 - 112 | 58 | 10 | 32 | C | 0.17 | 1.47 | 37.03 | 128.6 | 1.63 | |

| Bt3 | 112 - 155+ | 58 | 10 | 32 | C | 0.17 | nd | nd | nd | 1.56 | |

| Ap | 0 - 21 | 36 | 16 | 48 | SC | 0.44 | 0.78 | 67.54 | 132.1 | 1.68 | |

| TSA-P02 | BA1 | 21 - 41 | 42 | 14 | 44 | SC | 0.33 | nd | nd | nd | 1.74 |

| BA2k | 41 - 75/91 | 58 | 14 | 28 | C | 0.24 | 1.54 | 34.84 | 149.5 | 1.79 | |

| BCgk | 75/91- 155/165 | 66 | 14 | 20 | C | 0.21 | 1.58 | 36.82 | 166.6 | 1.53 | |

| CRgk | 155/165 - 200 | 8 | 6 | 86 | S | 0.75 | nd | nd | nd | 1.36 | |

|

ANGO-P01 |

Ap | 0 - 25/30 | 38 | 18 | 44 | SC | 0.47 | 1.44 | 46.71 | 101.0 | 1.67 |

| Bt1 | 25/30 - 70 | 62 | 14 | 24 | C | 0.22 | 1.41 | 41.82 | 132.9 | 1.61 | |

| Bt2 | 70 - 120 | 78 | 14 | 8 | C | 0.17 | 1.31 | 43.73 | 182.6 | 1.58 | |

| Bt3 | 120 - 181 | 74 | 18 | 8 | C | 0.24 | nd | nd | nd | 1.50 | |

|

ANGO-P02 |

Ap | 0 -29 | 54 | 14 | 32 | C | 0.25 | 1.26 | 47.69 | 94.7 | 1.28 |

| BA | 29 - 50 | 62 | 14 | 24 | C | 0.22 | 1.38 | 42.14 | 156.0 | 1.67 | |

| Bt | 50 - 86/118 | 64 | 16 | 20 | C | 0.25 | nd | nd | nd | 1.54 | |

| CR | 86/118- 181 | 16 | 8 | 76 | SL | 0.5 | 1.25 | 49.72 | 173.4 | 1.18 | |

| Pedon | Horizon | Depth (cm) | pHwater | pH CaCl2 | EC dS m-1 | Organic C (%) | Total N (%) | C/N | Avail. P Mehlich-3 (mg kg-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSA-P01 | Ap | 0 - 8 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 0.06 | 1.35 | 0.12 | 11.3 | 20.94 |

| Bt1 | 8 - 45 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 0.1 | 10.9 | 15.54 | |

| Bt2 | 45 - 112 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 0.02 | 0.6 | 0.07 | 8.6 | 14.18 | |

| Bt3 | 112 - 155+ | 6.4 | 5.2 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 8.8 | 13.37 | |

| TSA-P02 | Ap | 0 - 21 | 6.7 | 5.4 | 0.10 | 2.73 | 0.22 | 12.4 | 15.00 |

| BA1 | 21 - 41 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 0.10 | 1.58 | 0.14 | 11.3 | 13.10 | |

| BA2k | 41 - 75/91 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 0.13 | 0.92 | 0.09 | 10.2 | 28.51 | |

| BCgk | 75/91- 155/165 | 7.9 | 6.6 | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.06 | 9.2 | 17.83 | |

| CRgk | 155/165 - 200 | 7.9 | 6.5 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 4.0 | 19.05 | |

| ANGO-P01 | Ap | 0 - 25/30 | 6.1 | 5.0 | 0.04 | 1.44 | 0.13 | 11.1 | 17.56 |

| Bt1 | 25/30 - 70 | 6.2 | 4.6 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.09 | 10.9 | 14.18 | |

| Bt2 | 70 - 120 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 8.1 | 14.05 | |

| Bt3 | 120 - 181 | 6.4 | 5.1 | 0.01 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 8.8 | 15.67 | |

| ANGO-P02 | Ap | 0 -29 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 0.03 | 1.54 | 0.13 | 11.8 | 14.59 |

| BA | 29 - 50 | 6.0 | 4.7 | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 9.6 | 14.32 | |

| Bt | 50 - 86/118 | 6.1 | 5.0 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 10.3 | 14.32 | |

| CR | 86/118- 181 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 0.05 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.7 | 14.86 |

= Very Low,

= Very Low,  =Low,

=Low,  =Moderate.

=Moderate.| Pedons | Horizon | Depth (cm) | Micronutrients (mg kg-1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | Zn | Mn | Cu | |||

| TSA-P01 | Ap | 0 - 8 | 6.24 | 0.154 | 3.194 | 1.649 |

| Bt1 | 8 - 45 | 4.28 | 0.103 | 3.108 | 1.965 | |

| Bt2 | 45 - 112 | 3.44 | 0.038 | 2.978 | 1.569 | |

| Bt3 | 112 - 155+ | 3.48 | 0.023 | 2.863 | 1.316 | |

| TSA-P02 | Ap | 0 - 21 | 10.96 | 0.202 | 3.144 | 2.098 |

| BA1 | 21 - 41 | 6.32 | 0.065 | 3.173 | 1.930 | |

| BA2k | 41 - 75/91 | 3.84 | 0.091 | 2.007 | 1.836 | |

| BCgk | 75/91- 155/165 | 4.52 | 0.058 | 2.691 | 1.593 | |

| CRgk | 155/165 - 200 | 1.88 | 0.035 | 1.446 | 1.403 | |

| ANGO-P01 | Ap | 0 - 25/30 | 8.40 | 0.383 | 3.223 | 1.548 |

| Bt1 | 25/30 - 70 | 4.44 | 0.058 | 3.144 | 1.204 | |

| Bt2 | 70 - 120 | 2.88 | 0.023 | 2.763 | 1.148 | |

| Bt3 | 120 - 181 | 3.56 | 0.083 | 3.050 | 1.068 | |

| ANGO-P02 | Ap | 0 -29 | 4.72 | 0.096 | 2.957 | 1.262 |

| BA | 29 - 50 | 3.44 | 0.048 | 2.367 | 1.187 | |

| Bt | 50 - 86/118 | 3.00 | 0.065 | 2.317 | 0.981 | |

| CR | 86/118- 181 | 4.40 | 0.098 | 3.072 | 0.981 | |

=Low,

=Low,  =High.

=High.| Profile | Horizon | Depth (cm) | Total elemental composition % | Weathering Indices | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

L.O.I. |

SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | P2O5 | CaO | TiO2 | SO3 | K2O | Total | SiO2/Al2O3 | SiO2/(Al2O3+Fe2O3) | |||

| TSA-P01 | Ap | 0 - 8 | 9.39 | 54.60 | 24.13 | 8.44 | 0.37 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 99.4 | 2.26 | 1.68 |

| Bt2 | 45 - 112 | 10.16 | 45.96 | 27.55 | 10.49 | 1.68 | 1.06 | 0.32 | 0.84 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 98.93 | 1.67 | 1.21 | |

| Bt3 | 112 - 155+ | 10.15 | 46.67 | 26.36 | 10.59 | 2.78 | 1.31 | 0.25 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 99.75 | 1.77 | 1.26 | |

| TSA-P02 | Ap | 0 - 21 | 15.84 | 40.78 | 29.67 | 5.41 | 2.56 | 1.73 | 1.37 | 0.75 | 1.09 | 0.52 | 99.72 | 1.37 | 1.16 |

| BA2k | 41 - 75/91 | 14.31 | 40.53 | 31.2 | 6.49 | 1.63 | 1.11 | 1.02 | 0.86 | 1.28 | 0.7 | 99.13 | 1.30 | 1.08 | |

| CRgk | 155/165 - 200 | 3.17 | 69.12 | 16.26 | 1.15 | 1.23 | 0.98 | 5.86 | 0.09 | 0.77 | 0.09 | 98.72 | 4.25 | 3.97 | |

| ANGO-P01 | Ap | 0 - 25/30 | 9.69 | 46.12 | 25.44 | 10.69 | 0.87 | 3.76 | 0.49 | 1.21 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 99.77 | 1.81 | 1.28 |

| Bt2 | 70 - 120 | 14.63 | 39.40 | 27.98 | 13.76 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.27 | 1.08 | 0.30 | 0.44 | 99.08 | 1.41 | 0.94 | |

| Bt3 | 120 - 181 | 14.28 | 41.11 | 26.5 | 13.95 | 1.31 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 1.13 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 99.87 | 1.55 | 1.02 | |

| ANGO-P02 | Ap | 0 - 29 | 14.95 | 38.50 | 26.68 | 12.48 | 1.38 | 2.97 | 0.42 | 1.04 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 99.62 | 1.44 | 0.98 |

| Bt | 50 - 186/118 | 14.21 | 40.70 | 25.64 | 12.95 | 1.03 | 2.77 | 0.31 | 0.92 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 99.48 | 1.59 | 1.05 | |

| CR | 86/118 - 181 | 7.62 | 55.16 | 21.96 | 10.23 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 1.13 | 99.34 | 2.51 | 1.71 | |

| Profile | Horizon | Depth | Ba | Zr | Sr | Pb |

| mg dm-3 | ||||||

| TSA-P01 | Ap | 0 - 8 | 209 | 206 | 91 | 129 |

| Bt2 | 45 - 112 | 237 | 141 | 67 | 443 | |

| Bt3 | 112 - 155+ | 190 | 151 | 56 | 39 | |

| TSA-P02 | Ap | 0 - 21 | 380 | 258 | 247 | 62 |

| BA2k | 41 - 75/91 | 579 | 358 | 295 | 51 | |

| CRgk | 155/165 - 200 | 189 | 5 | 342 | 41 | |

| ANGO-P01 | Ap | 0 - 25/30 | 1075 | 783 | 389 | 85 |

| Bt2 | 70 - 120 | 600 | 295 | 164 | 66 | |

| Bt3 | 120 - 181 | 535 | 370 | 158 | 22 | |

| ANGO-P02 | Ap | 0 - 29 | 761 | 1056 | 328 | 32 |

| Bt | 50 - 186/118 | 677 | 650 | 284 | 33 | |

| CR | 86/118 - 181 | 1011 | 448 | 573 | 50 | |

| Pedon | Diagnostic horizons | Other diagnostic features | Order | Suborder | Great group | Sub-group | Family |

| TSA-P01 | Ochric epipedon; argillic subsurface horizon | Moderately steep, very deep, highly weathered clayey subsoil, Ustic SMR, medium acid to slightly acid, thermic STR, mixed to dominantly kaolinitic, many clay+sesquioxide cutans | Ultisols | Ustults | Haplustults | Typic Haplustults | Moderately steep, very deep, clayey, medium acid to slightly acid, mixed to dominantly kaolinitic, thermic, Typic Haplustults |

| TSA-P02 | Ochric epipedon. Calcic horizon in the subsoil (strongly effervescent) |

Almost flat to gently sloping mbuga (slope about 3%), very deep, black clayey soil (heavy clay), ustic SMR, mildly alkaline, thermic STR, presence of deep wide cracks, wedge-shaped and extremely hard prismatic aggregates, many distinct slickensides, presence of gilgai micro-relief | Vertisols | Usterts | Calciusterts | Typic Calciusterts |

Almost flat to gently sloping, very deep, clayey, mildly alkaline, mixed to dominantly montimorrilonitic; thermic, Typic Calciusterts |

| ANGO-P01 | Mollic epipedon; argillic subsurface horizon | Moderately steep, very deep, highly weathered clayey subsoil, Ustic SMR, slightly acid, thermic STR, mixed to dominantly kaolinitic, many clay+sesquioxide cutans | Ultisols | Ustults | Paleustults | Typic Paleustults | Moderately steep, very deep, clayey, slightly acid, mixed to dominantly kaolinitic, thermic, Typic Paleustults |

| ANGO-P02 | Umbric epipedon; argillic subsurface | Strongly sloping, very deep, highly weathered clayey subsoil, Ustic SMR, medium acid, thermic STR, mixed to dominantly kaolinitic, many clay+sesquioxide cutans | Alfisols | Ustalfs | Haplustalfs | Ultic Haplustalfs | Strongly sloping, very deep, clayey, medium acid, mixed to dominantly kaolinitic, thermic, Ultic Haplustalfs |

| Pedon | Diagnostic horizons, properties and materials | Reference soil group (RSG) - TIER-1 | Principal Qualifiers | Supplementary Qualifiers | WRB soil name - TIER- 2 |

| TSA-P01 | Ochric horizon; argic horizon with CEC of ≥ 24 cmol(+) kg-1 and low BS of < 50%) | Acrisols | Haplic | Clayic, Cutanic, Hyperdystric, Humic, Profondic | Haplic Acrisols (Clayic, Cutanic, Hyperdystric, Humic, Profondic) |

| TSA-P02 | Vertic horizon, ≥ 30% clay between the soil surface and the vertic horizon, shrink-swell cracks, gilgai microrelief |

Vertisols | Calcic, Pellic | Calcaric, Hypereutric, Gilgaic, Mazic, Humic | Pellic Calcic Vertisols(Calcaric, Hypereutric, Gilgaic, Mazic, Humic) |

| ANGO-P01 | Mollic horizon; argic horizon with CEC of greater part of argic ≥ 24 cmol(+) kg-1 and low BS < 50%) | Alisols | Abruptic, Chromic | Clayic, Cutanic, Hyperdystric, Humic, Profondic | Chromic Abruptic Alisols(Clayic, Cutanic, Hyperdystric, Humic, Profondic) |

| ANGO-P02 | Mollic horizon; argic horizon with CEC of argic ≥ 24 cmol(+) kg-1 and high BS ≥ 50%) | Luvisols | Chromic | Clayic, Cutanic, Humic, Profondic | Chromic Luvisols (Clayic, Cutanic, Humic, Profondic) |

| Land quality | Diagnostic factor | Required range | Actual field range | Rating | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSA-P01 | TSA-P02 | ANGO-P01 | ANGO-P02 | TSA-P01 | TSA-P02 | ANGO-P01 | ANGO-P02 | |||

| Climate (c) | Annual rainfall | 700 - 2600 | 1000 - 1200 | 1000 -1200 | 800 - 1200 | 800 - 1200 | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 |

| Temperature | 8 - 18 | 15 - 20 | 15 - 20 | 15 -22 | 15 - 22 | S3 | S3 | S3 | S3 | |

| Topography (t) | Slope (%) | 0 -12 | 16 | 5 | 16 | 12 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S1 |

| Elevation | 1500 - 3200 | 1427 | 1340 | 1260 | 1200 | S2 | S2 | S3 | S3 | |

| Soil physical property (s) | Soil texture | L, SL, SiL | C, SC, SCL | C, SC | C, SC | C, SL | S2 | S3 | S3 | S2 |

| Effective depth | > 40 cm | > 181 cm | > 181 cm | > 151 cm | > 200 cm | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 | |

| Soil drainage | Well drained | Well drained | Well drained | Well to excessively well drained | Well to moderately well drained | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 | |

| Soil toxicity (n) | EC (dSm-1) | < 4.0 | 0.02 - 0.06 | 0.09 - 0.28 | 0.01 - 0.04 | 0.02 - 0.05 | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 |

| ESP | < 6 | 0.37 - 0.55 | 0.65 - 1.30 | 0.47 - 0.59 | 0.38 - 0.48 | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 | |

| Soil fertility (f) | Soil pH water | 5.5 – 7 | 5.5 - 6.4 | 6.7 - 7.9 | 6.1 - 6.4 | 5.9 - 6.1 | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 |

| (CEC cmol(+) kg-1) |

> 25 | 10.15 - 10.85 | 10.06 - 10.81 | 10.1 - 10.72 | 10.1 - 10.8 | S3 | S3 | S3 | S3 | |

| OC (%) | > 1.8 | 0.53 - 1.35 | 0.16 - 2.73 | 0.53 - 1.44 | 0.62 - 1.54 | S3 | S1 | S3 | S3 | |

| TN (%) | > 0.3 | 0.06 - 0.12 | 0 04 - 0.22 | 0 06 - 0.13 | 0 03- 0.3 | S3 | S2 | S3 | S3 | |

| Avail. P mg dm-3 | > 35 | 13.3 - 20.9 | 13.1 - 28.5 | 14.0 - 17.56 | 14.31 - 14.86 | S3 | S3 | S3 | S3 | |

| K (CEC cmol(+) kg-1) |

> 0.89 | 0.12 - 0.4 | 0.13 - 1.19 | 0.22 - 0.53 | 0.08 - 0.12 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| Ca (CEC cmol(+) kg-1) |

> 10 | 0.65 - 1.19 | 1.5 - 13.18 | 1.51 - 2.2 | 2.37 - 4.01 | S3 | S1 | S3 | S3 | |

| Mg (CEC cmol(+) kg-1) | > 3 | 0.98 - 1.66 | 0.64 - 3.08 | 1.91 - 2.66 | 0.2 - 3.08 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S1 | |

| BS (%) | > 61 | 19.3 - 30.0 | 23.2 - 153,7 | 34.6 - 51.8 | 30.7 - 66.9 | S3 | S1 | S2 | S1 | |

| Cu (mg kg-1) | > 0.2 | 1.31 - 1.96 | 1.40 - 2.09 | 1.06 - 1.54 | 0.98 - 1.26 | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 | |

| Mn (mg kg-1) | > 1.1 | 2.86 - 3.19 | 1.44 - 3.14 | 2.76 - 3.22 | 2.31 - 3.07 | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 | |

| Fe (mg kg-1) | > 2.5 | 3.44 - 6.24 | 1.88 - 10.96 | 2.88 - 8.40 | 3.00 - 4.72 | S1 | S1 | S1 | S1 | |

| Zn (mg kg-1) | > 0.6 | 0.02 - 0.15 | 0.03 - 0.20 | 0.05 - 0.38 | 0.04 - 0.09 | S3 | S3 | S3 | S3 | |

| Overall suitability class (OSC) | S3f(c) | S3f(cs) | S3f(cts) | S3f(ct) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).