Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Computational Methods

Slab generation and assessment of simulation parameters

2.2. Experimental Methods

Preparation of

Preparation of Phenyl-Modified Carbon Nitride

Preparation of PhCN/ in Ethanol

Preparation of PhCN/ in Water

Preparation of / in Water

Characterization

Photodegradation of Rhodamine B

3. Results and Discussion

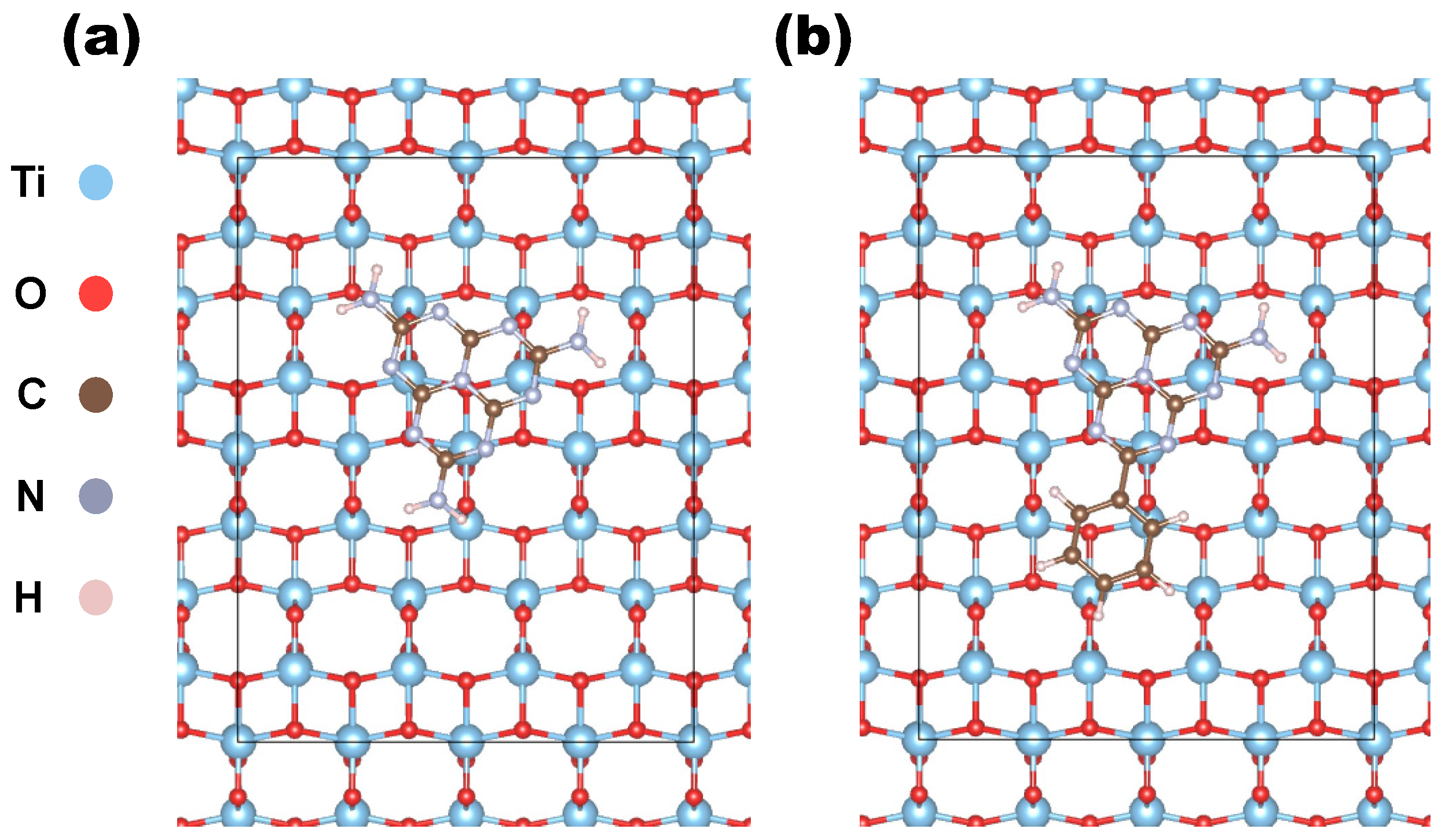

3.1. Computational Results: Stability and Energetics of the Heterostructure

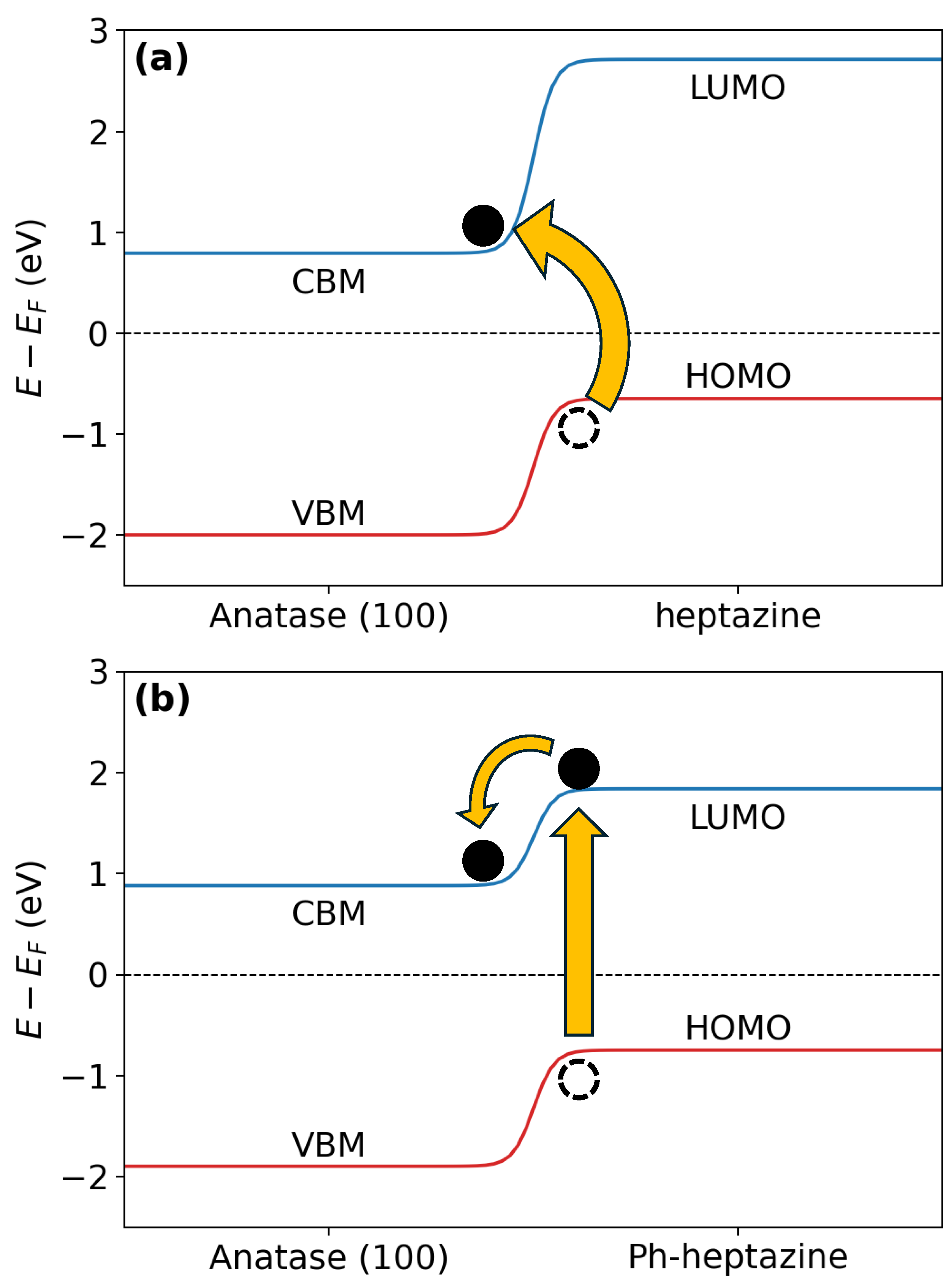

3.2. Computational Results: Band Alignment

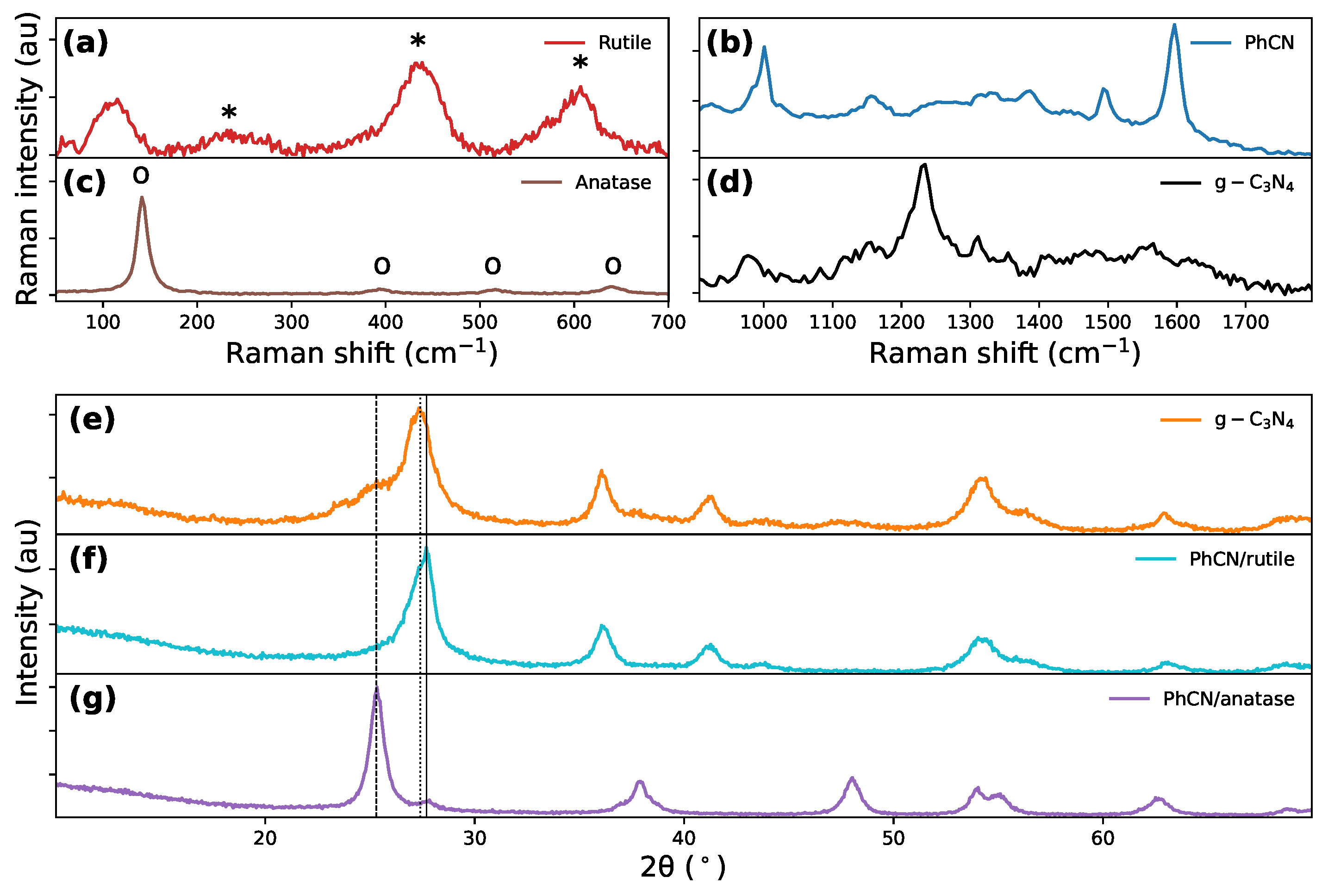

3.3. Experimental Results: Raman and XRD Measurements

- two PhCN/ hybrids synthesized either with ethanol or water, thus in the anatase and rutile phase, respectively (PhCN/anatase, PhCN/rutile) to verify the charge transfer mechanism and assess the potential of the hybrid structure for visible, solar-driven applications

- / synthesized with water, thus in the rutile phase (/rutile) to explore the specific role of the phenyl group

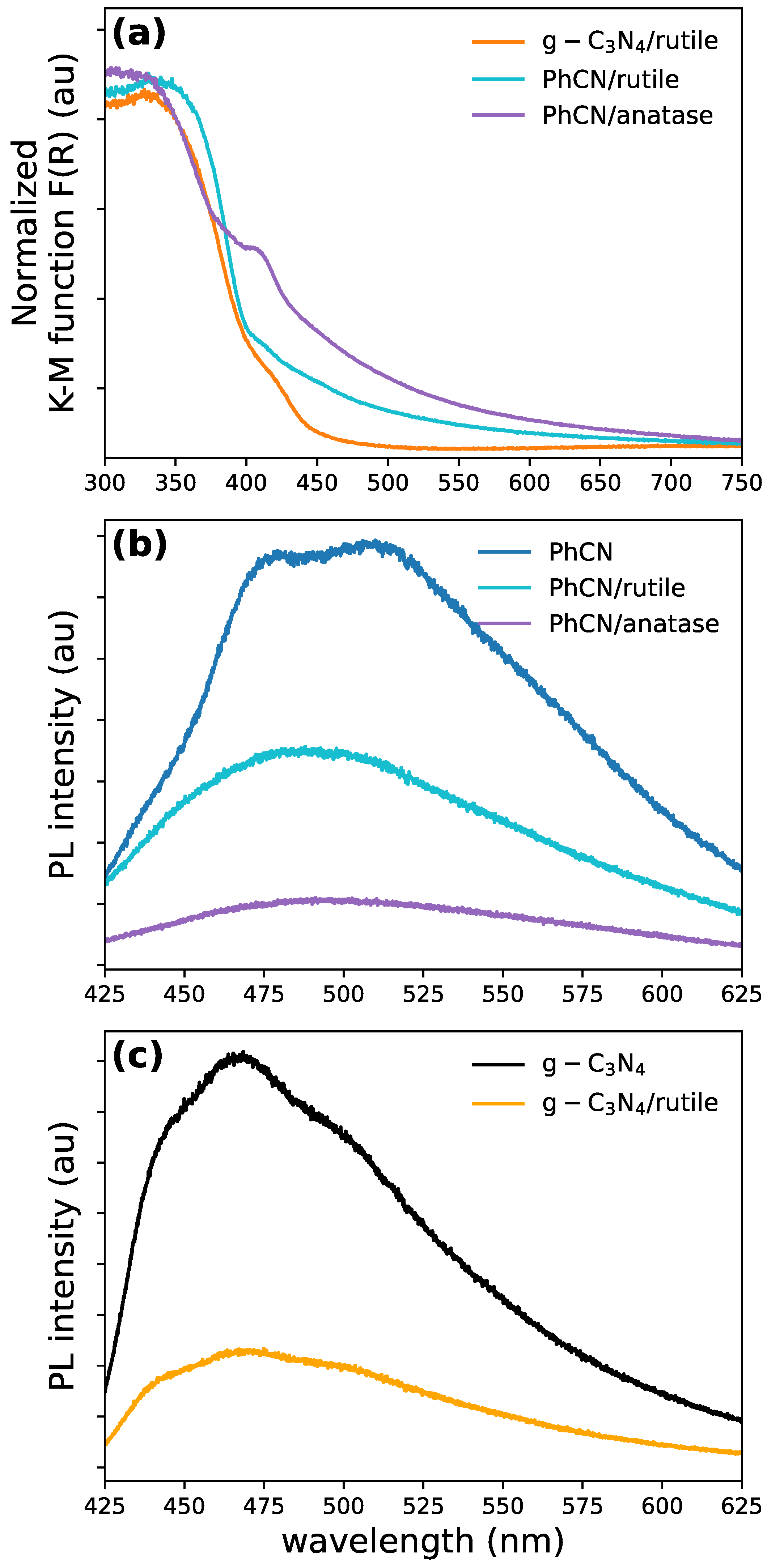

3.4. Experimental Results: Absorption and Emission Spectra

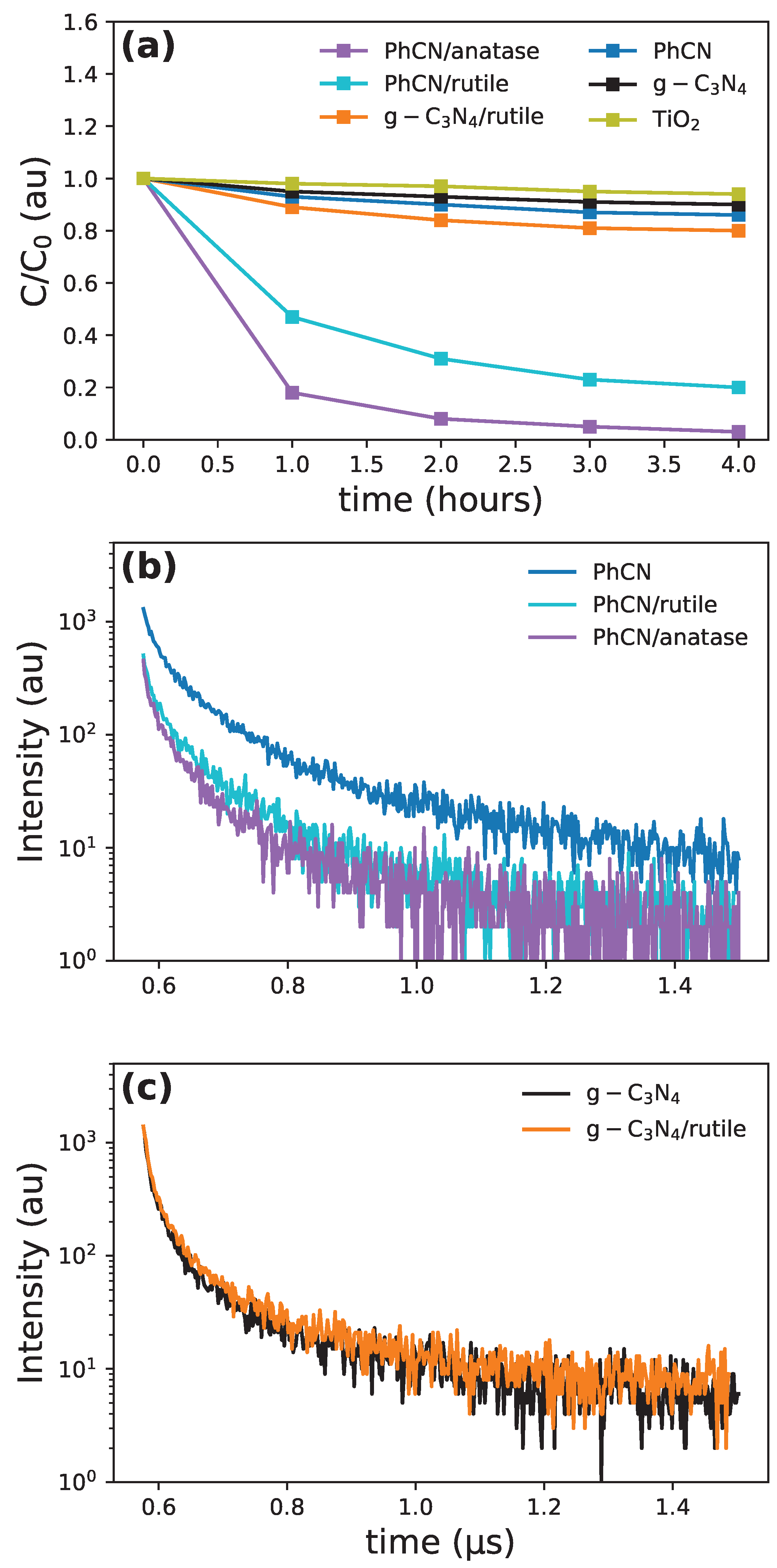

3.5. Experimental Results: Photocatalytic Efficiency

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bledowski, M.; Wang, L.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Khavryuchenko, O.V.; Khavryuchenko, V.D.; Ricci, P.C.; Strunk, J.; Cremer, T.; Kolbeck, C.; Beranek, R. Visible-light photocurrent response of TiO2–polyheptazine hybrids: evidence for interfacial charge-transfer absorption. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2011, 13, 21511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basivi, P.K.; Selvaraj, Y.; Perumal, S.; Bojarajan, A.K.; Lin, X.; Girirajan, M.; Kim, C.W.; Sangaraju, S. Graphitic carbon nitride (g–C3N4)–Based Z-scheme photocatalysts: Innovations for energy and environmental applications. Materials Today Sustainability 2025, 29, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Sun, Y.; Dong, F. Graphitic carbon nitride based nanocomposites: a review. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, W.J.; Tan, L.L.; Ng, Y.H.; Yong, S.T.; Chai, S.P. Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4)-Based Photocatalysts for Artificial Photosynthesis and Environmental Remediation: Are We a Step Closer To Achieving Sustainability? Chemical Reviews 2016, 116, 7159–7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Li, H.; Yu, D.; Zhang, D. g-C3N4-Based Heterojunction for Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance: A Review of Fabrications, Applications, and Perspectives. Catalysts 2024, 14, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Antonietti, M. Polymeric Graphitic Carbon Nitride as a Heterogeneous Organocatalyst: From Photochemistry to Multipurpose Catalysis to Sustainable Chemistry. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2011, 51, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcu, S.; Secci, F.; Ricci, P.C. Advances in Hybrid Composites for Photocatalytic Applications: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, S.; Low, J.; Xiao, W. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of direct Z-scheme g-C3N4–TiO2 photocatalysts for the decomposition of formaldehyde in air. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2013, 15, 16883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, R.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Yu, M.; Xing, Y.; Shi, Z. Preparation of phenyl group functionalized g-C3N4 nanosheets with extended electron delocalization for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. New Journal of Chemistry 2018, 42, 6756–6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcu, S.; Roppolo, I.; Salaun, M.; Sarais, G.; Barbarossa, S.; Casula, M.F.; Carbonaro, C.M.; Ricci, P.C. Come to light: Detailed analysis of thermally treated Phenyl modified Carbon Nitride Polymorphs for bright phosphors in lighting applications. Applied Surface Science 2020, 504, 144330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, X. A one-step process for preparing a phenyl-modified g-C3N4 green phosphor with a high quantum yield. RSC Advances 2017, 7, 51702–51710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcu, S.; Castellino, M.; Roppolo, I.; Carbonaro, C.M.; Palmas, S.; Mais, L.; Casula, M.F.; Neretina, S.; Hughes, R.A.; Secci, F.; et al. Highly efficient visible light phenyl modified carbon nitride/TiO2 photocatalyst for environmental applications. Applied Surface Science 2020, 531, 147394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J.C. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.; Eghbali, N. Green Chemistry: Principles and Practice. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Chemistry | US EPA — epa.gov. https://www.epa.gov/greenchemistry.

- Elstner, M.; Porezag, D.; Jungnickel, G.; Elsner, J.; Haugk, M.; Frauenheim, T.; Suhai, S.; Seifert, G. Self-consistent-charge density-functional tight-binding method for simulations of complex materials properties. Physical Review B 1998, 58, 7260–7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradi, B.; Hourahine, B.; Frauenheim, T. DFTB+, a sparse matrix-based implementation of the DFTB method. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 5678–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaus, M.; Cui, Q.; Elstner, M. DFTB3: Extension of the Self-Consistent-Charge Density-Functional Tight-Binding Method (SCC-DFTB). J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranz, J.J.; Kubillus, M.; Ramakrishnan, R.; von Lilienfeld, O.A.; Elstner, M. Generalized density-functional tight-binding repulsive potentials from unsupervised machine learning. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 2341–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaa, M.R.; Fried, L.E.; Melius, C.F.; Elstner, M.; Frauenheim, T. Decomposition of HMX at Extreme Conditions: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 9024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Qian, H.J.; Irle, S.; Lu, X.; Roston, D.; Mori, T.; Elstner, M.; Cui, Q. Molecular Simulation of Water and Hydration Effects in Different Environments: Challenges and Developments for DFTB Based Models. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2014, 118, 11007–11027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, N.; Fried, L.E.; Lindsey, R.K.; Pham, C.H.; Dettori, R. Enhancing the accuracy of density functional tight binding models through ChIMES many-body interaction potentials. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2023, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, R.; Goldman, N. Creation of an Fe3P Schreibersite Density Functional Tight Binding Model for Astrobiological Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2025, 129, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, N.; Srinivasan, S.G.; Hamel, S.; Fried, L.E.; Gaus, M.; Elstner, M. Determination of a density functional tight binding model with an extended basis set and three-body repulsion for carbon under extreme pressures and temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7885–7894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.G.; Goldman, N.; Tamblyn, I.; Hamel, S.; Gaus, M. Determination of a density functional tight binding model with an extended basis set and three-body repulsion for hydrogen under extreme thermodynamic conditions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 5520–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkatchenko, A.; Scheffler, M. Accurate Molecular Van Der Waals Interactions from Ground-State Electron Density and Free-Atom Reference Data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 073005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehaus, T.; Elstner, M.; Frauenheim, T.; Suhai, S. Application of an approximate density-functional method to sulfur containing compounds. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM 2001, 541, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgonos, G.; Aradi, B.; Moreira, N.H.; Frauenheim, T. An Improved Self-Consistent-Charge Density-Functional Tight-Binding (SCC-DFTB) Set of Parameters for Simulation of Bulk and Molecular Systems Involving Titanium. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2009, 6, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 14251–14269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methfessel, M.; Paxton, A.T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 40, 3616–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeri, M.; Vittadini, A.; Selloni, A. Structure and energetics of stoichiometric TiO2 anatase surfaces. Physical Review B 2001, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.Q.; Selloni, A.; Batzill, M.; Diebold, U. Steps on anatase TiO2(101). Nature Materials 2006, 5, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C.J.; Sabine, T.M.; Dickson, F. Structural and thermal parameters for rutile and anatase. Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science 1991, 47, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. New understanding of the difference of photocatalytic activity among anatase, rutile and brookite TiO2. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2014, 16, 20382–20386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martsinovich, N.; Troisi, A. How TiO2 crystallographic surfaces influence charge injection rates from a chemisorbed dye sensitiser. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2012, 14, 13392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, H.; Domain, C.; Roques, J.; Drot, R.; Simoni, E.; Catalette, H. Optimisation of accurate rutile TiO2 (110), (100), (101) and (001) surface models from periodic DFT calculations. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 2007, 117, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Zhao, Z.; Xiong, T.; Ni, Z.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Y.; Ho, W.K. In situ construction of g-C3N4/g-C3N4 metal-free heterojunction for enhanced visible-light photocatalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 11392–11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Maeda, K.; Thomas, A.; Takanabe, K.; Xin, G.; Carlsson, J.M.; Domen, K.; Antonietti, M. A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, H.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, M.; Shi, J.; Tang, Y.; Dai, X. Theoretical exploration of the structural, electronic and optical properties of g-C3N4/C3N heterostructures. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2023, 25, 4081–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merschjann, C.; Tyborski, T.; Orthmann, S.; Yang, F.; Schwarzburg, K.; Lublow, M.; Lux-Steiner, M.C.; Schedel-Niedrig, T. Photophysics of polymeric carbon nitride: An optical quasimonomer. Physical Review B 2013, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Antonietti, M.; Shalom, M. Phenyl-Modified Carbon Nitride Quantum Dots with Distinct Photoluminescence Behavior. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2016, 55, 3672–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalkińska, M.; Dudziak, S.; Karczewski, J.; Ryl, J.; Trykowski, G.; Zielińska-Jurek, A. Facet effect of TiO2 nanostructures from TiOF2 and their photocatalytic activity. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 404, 126493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, U. The surface science of titanium dioxide. Surface Science Reports 2003, 48, 53–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Domen, K. New Non-Oxide Photocatalysts Designed for Overall Water Splitting under Visible Light. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2007, 111, 7851–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, P.V. Meeting the Clean Energy Demand: Nanostructure Architectures for Solar Energy Conversion. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2007, 111, 2834–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUJISHIMA, A.; ZHANG, X.; TRYK, D. TiO2 photocatalysis and related surface phenomena. Surface Science Reports 2008, 63, 515–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, Y.; Vayssieres, L.; Durrant, J.R. Artificial photosynthesis for solar water-splitting. Nature Photonics 2012, 6, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, B.; Grätzel, M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 1991, 353, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.J.; Reardon, P.J.T.; Moniz, S.J.A.; Tang, J. Visible Light-Driven Pure Water Splitting by a Nature-Inspired Organic Semiconductor-Based System. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 12568–12571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wategaonkar, S.; Pawar, R.; Parale, V.; Nade, D.; Sargar, B.; Mane, R. Synthesis of rutile TiO2 nanostructures by single step hydrothermal route and its characterization. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 23, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, J.; Mamakhel, A.; Søndergaard-Pedersen, F.; Yu, J.; Iversen, B.B. Continuous flow hydrothermal synthesis of phase pure rutile TiO2 nanoparticles with a rod-like morphology. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 2695–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.C.; Xie, S.H.; Liu, Z.P. Nature of Rutile Nuclei in Anatase-to-Rutile Phase Transition. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2015, 137, 11532–11539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, P.C.; Carbonaro, C.M.; Stagi, L.; Salis, M.; Casu, A.; Enzo, S.; Delogu, F. Anatase-to-Rutile Phase Transition in TiO2 Nanoparticles Irradiated by Visible Light. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2013, 117, 7850–7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, U.; Eror, N. Raman spectra of titanium dioxide. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 1982, 42, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, Q.; Chai, G.; Liang, M.; Dong, G.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, J. Synthesis and luminescence mechanism of multicolor-emitting g-C3N4 nanopowders by low temperature thermal condensation of melamine. Scientific Reports 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DFT (Å) | DFTB (Å) | |||

| rutile | a | 4.648 | 4.619 | 0.63% |

| c | 2.971 | 2.991 | -0.68% | |

| anatase | a | 3.805 | 3.758 | 1.26% |

| c | 9.747 | 9.605 | 1.45% |

| anatase (J/ m 2) | rutile (J/ m 2) | ||

| DFTB | 100 | 0.85 | 1.09 |

| 110 | 1.39 | 0.88 | |

| Different XC[42] | 100 | 0.53-0.90 | 0.67-0.77 |

| PBE-D4+U[43] | 110 | 0.95-1.32 | 0.48-0.54 |

| (eV) | triazine | Ph-triazine | heptazine | Ph-heptazine | |

| anatase | 100 | -0.59 | -0.76 | -0.64 | -0.63 |

| 110 | -0.82 | -0.99 | -0.96 | -1.21 | |

| rutile | 100 | -0.27 | -0.18 | -0.50 | -0.42 |

| 110 | -0.54 | -0.86 | -0.58 | -0.95 |

| Substrate | Molecule | |||

| 100 | Anatase | triazine | 2.34 | 1.89 |

| ph-triazine | 1.05 | 2.16 | ||

| Rutile | triazine | 4.34 | 0.75 | |

| ph-triazine | 2.36 | 1.07 | ||

| 110 | Anatase | triazine | 2.99 | 1.66 |

| ph-triazine | 1.11 | 2.23 | ||

| Rutile | triazine | 2.99 | 1.66 | |

| ph-triazine | 1.60 | 1.23 | ||

| 100 | Anatase | heptazine | 1.92 | 1.44 |

| ph-heptazine | 0.96 | 1.63 | ||

| Rutile | heptazine | 2.94 | 0.57 | |

| ph-heptazine | 1.81 | 0.76 | ||

| 110 | Anatase | heptazine | 1.62 | 1.68 |

| ph-heptazine | 0.61 | 1.87 | ||

| Rutile | heptazine | 2.90 | 0.60 | |

| ph-heptazine | 1.36 | 0.97 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).