Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

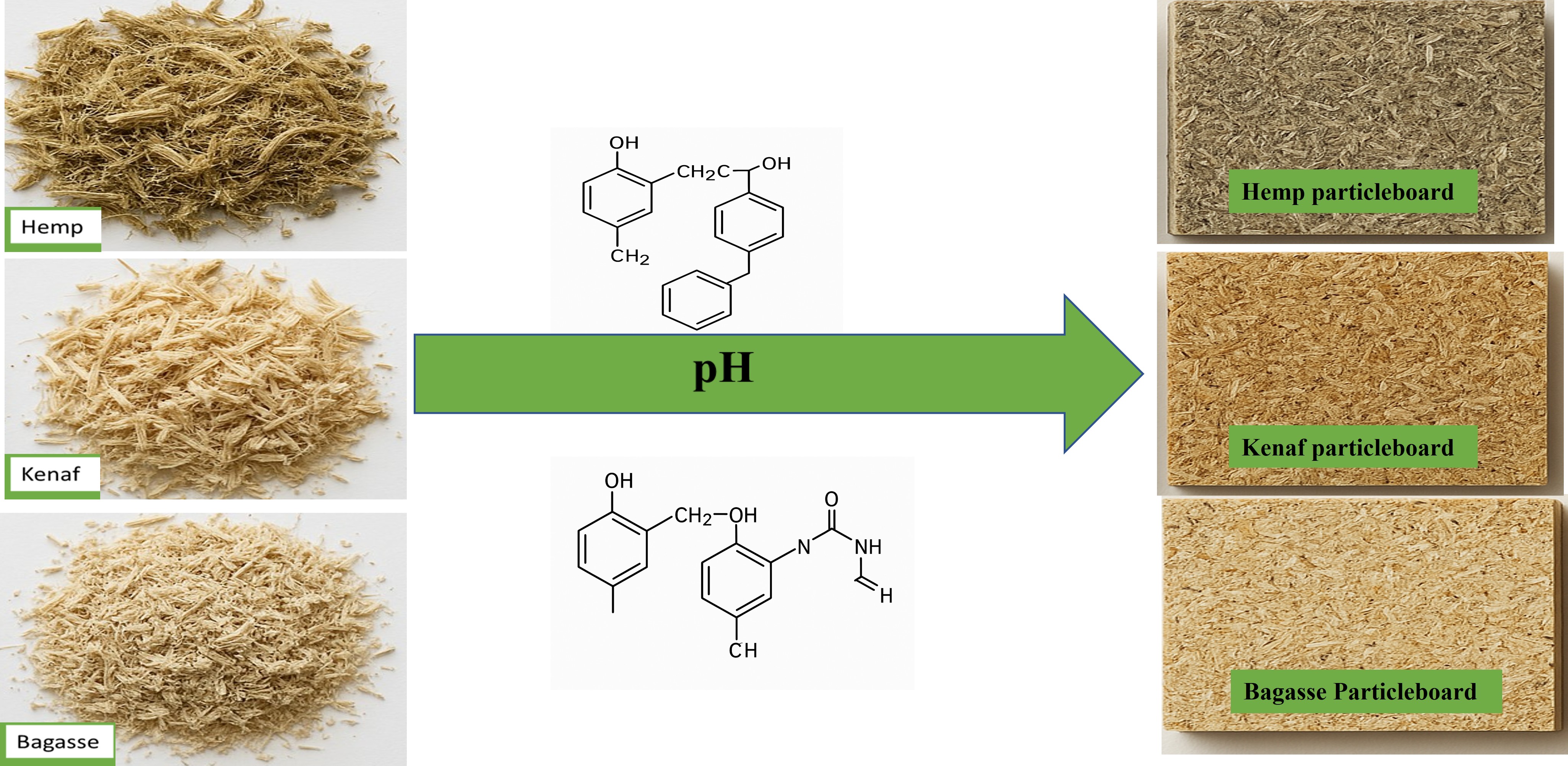

2.1.1. Lignocellulosic Materials

2.1.2. Binding Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Fibers’ pH Modification

2.2.3. Panel Manufacturing

2.2.4. Mechanical and Physical Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanical Properties

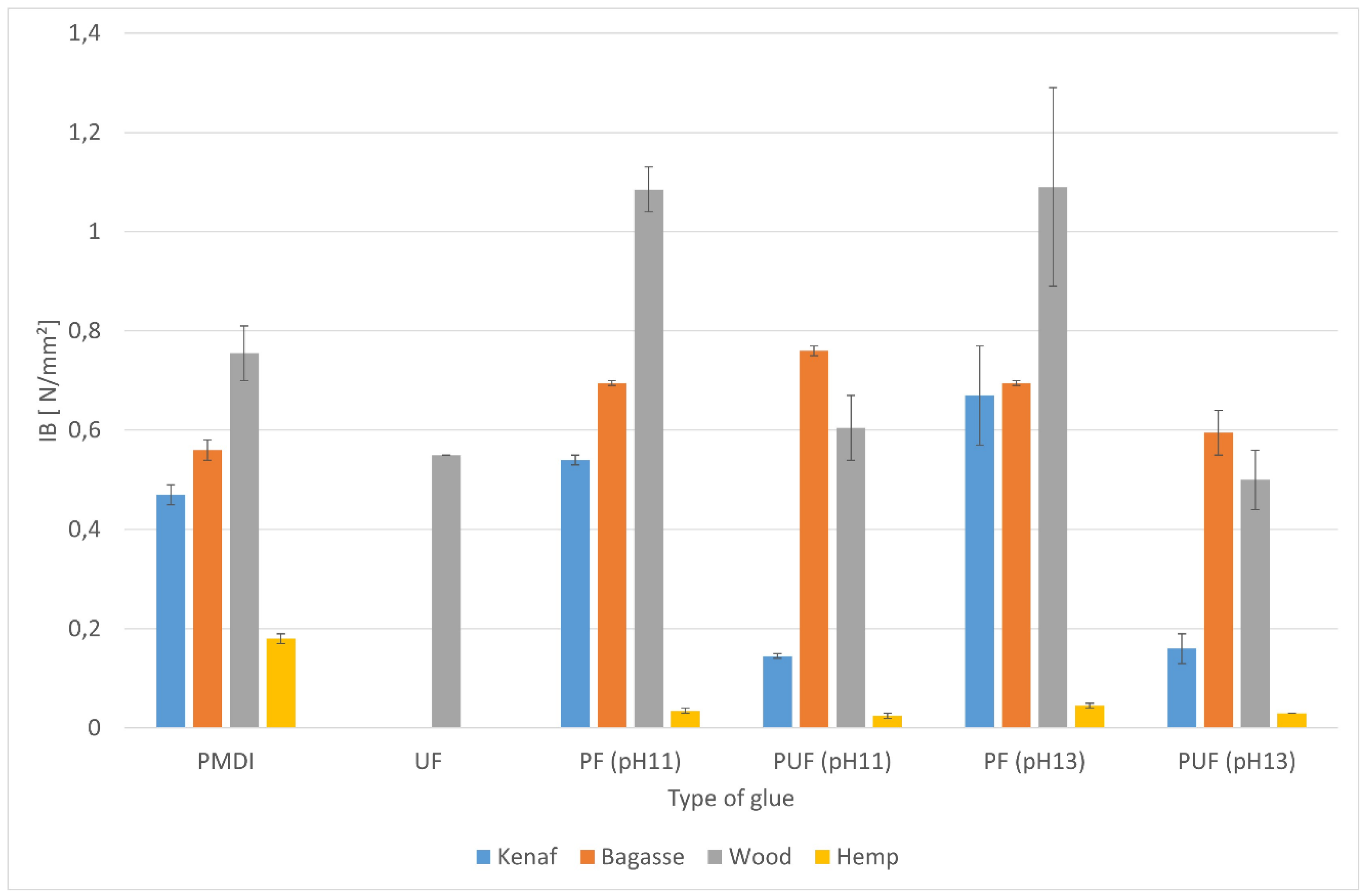

3.1.1. Internal Bond

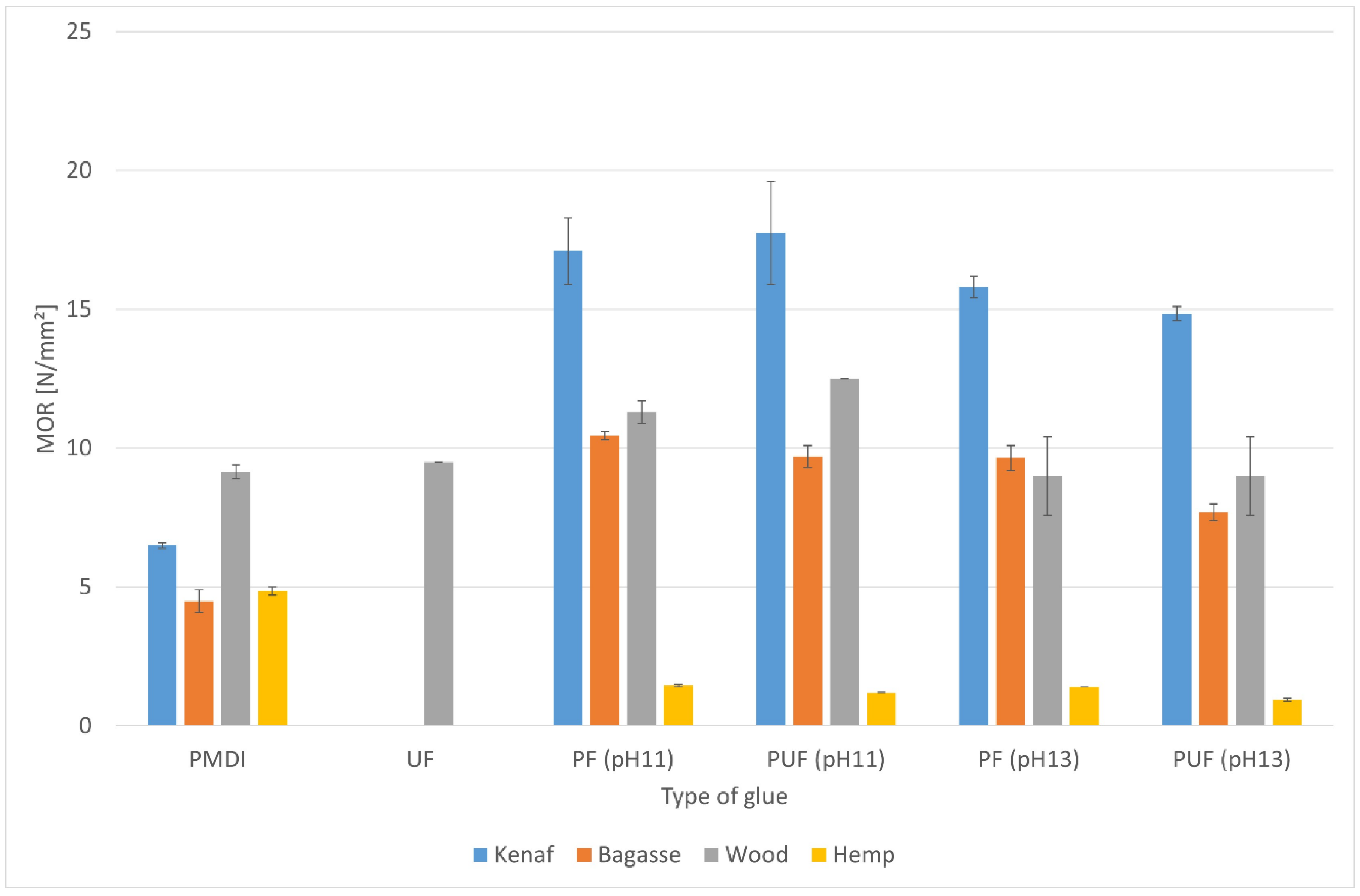

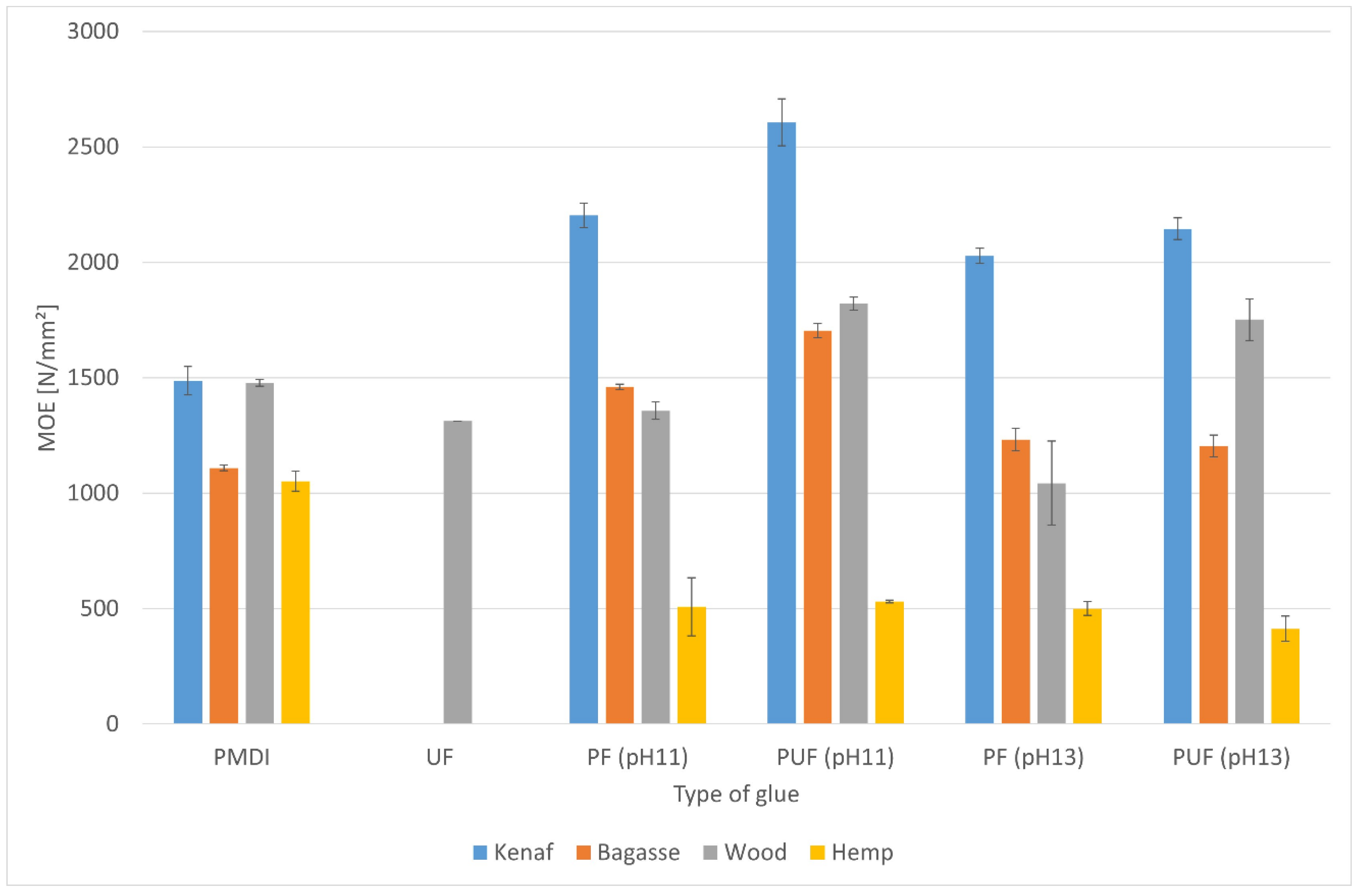

3.1.2. Modulus of Elasticity (MOE) and Modulus of Rupture (MOR)

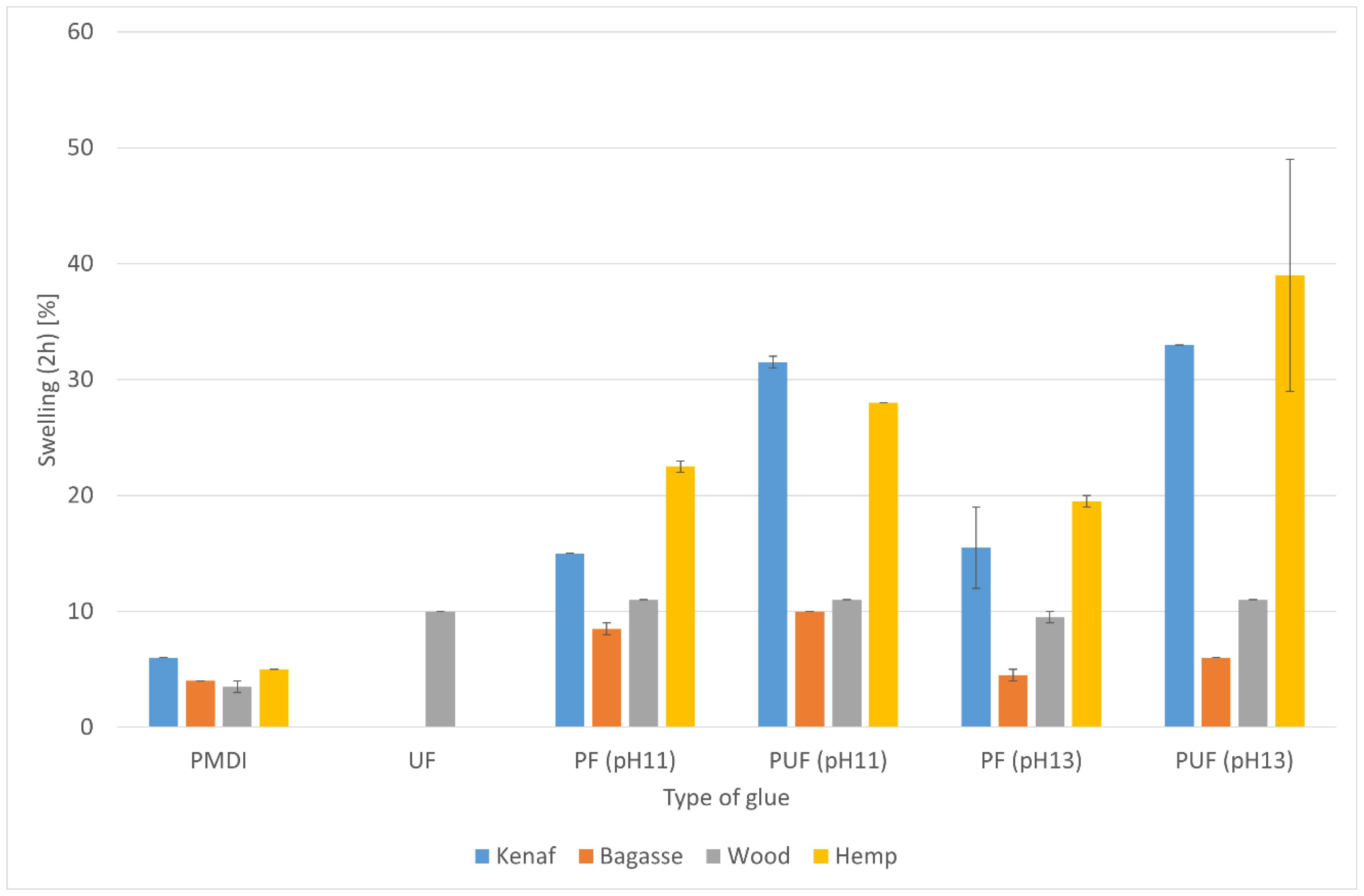

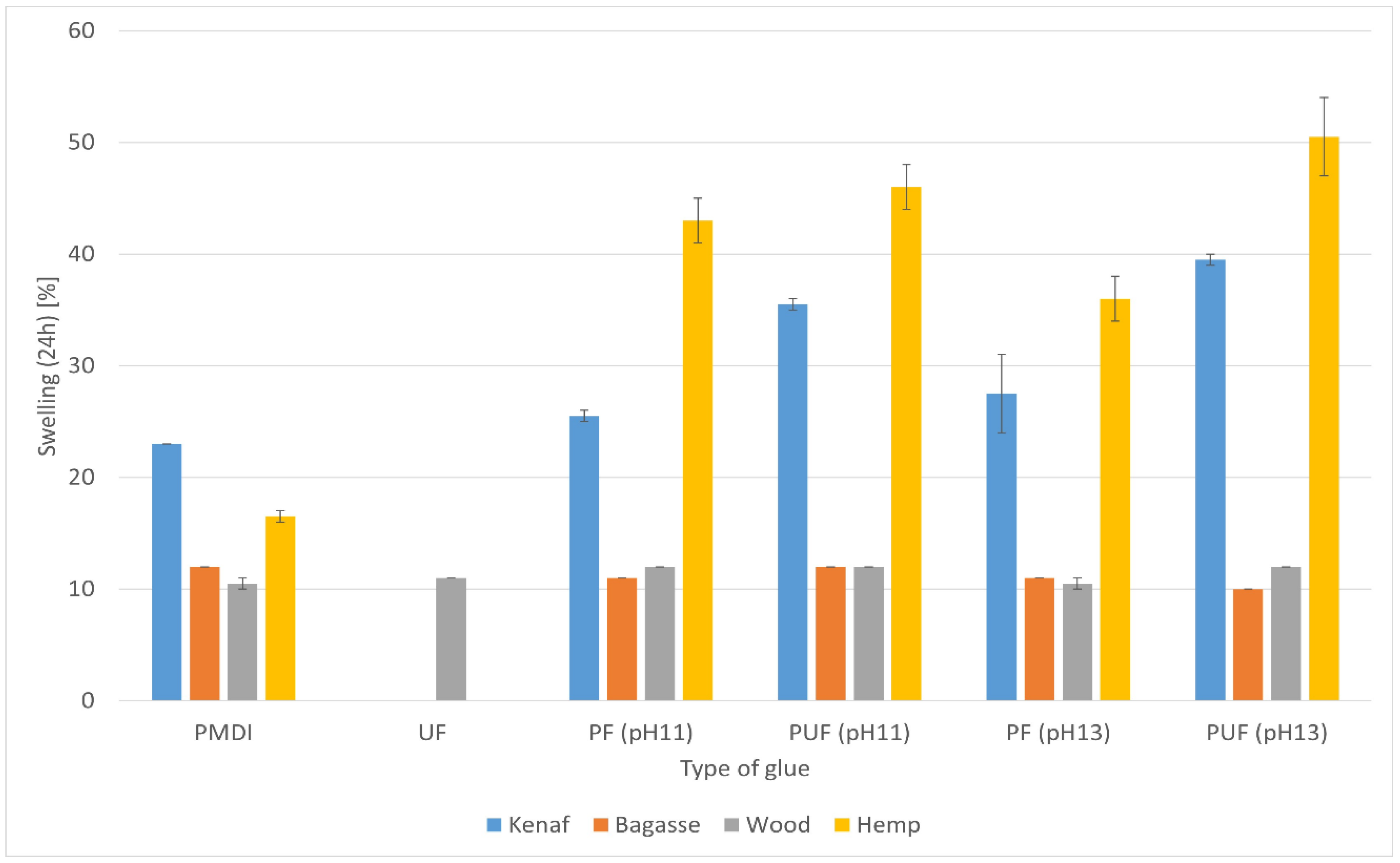

3.2. Physical Properties

3.2.1. Thickness Swelling for 24hrs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M.; Drzal, L.T. Sustainable Bio-Composites from Renewable Resources: Opportunities and Challenges in the Green Materials World. J. Polym. Environ. 2002, 10, 19–26. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Haufe, J.; Carus, M.; Brandão, M.; Bringezu, S.; Hermann, B.; Patel, M.K. A Review of the Environmental Impacts of Biobased Materials. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, S169–S181. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lum, W.C.; Boon, J.G.; Kristak, L.; Antov, P.; Pedzik, M.; Rogozinski, T.; Taghiyari, H.R.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Fatriasari, W.; et al. Particleboard from Agricultural Biomass and Recycled Wood Waste: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 4630–4658. [CrossRef]

- Owodunni, A.A.; Lamaming, J.; Hashim, R.; Taiwo, O.F.A.; Hussin, M.H.; Mohamad Kassim, M.H.; Bustami, Y.; Sulaiman, O.; Amini, M.H.M.; Hiziroglu, S. Adhesive Application on Particleboard from Natural Fibers: A Review. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 4448–4460. [CrossRef]

- Antov, P.; Krišt’ák, L.; Réh, R.; Savov, V.; Papadopoulos, A.N. Eco-Friendly Fiberboard Panels from Recycled Fibers Bonded with Calcium Lignosulfonate. Polym. 2021, Vol. 13, Page 639 2021, 13, 639. [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska, D.; Frackowiak, I.; Mytko, K. Exploitation of Liquefied Wood Waste for Binding Recycled Wood Particleboards. Holzforschung 2016, 70, 1135–1138. [CrossRef]

- Pędzik, M.; Janiszewska, D.; Rogoziński, T. Alternative Lignocellulosic Raw Materials in Particleboard Production: A Review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 174, 114162. [CrossRef]

- Mirski, R.; Dukarska, D.; Walkiewicz, J.; Derkowski, A. Waste Wood Particles from Primary Wood Processing as a Filler of Insulation PUR Foams. Mater. 2021, Vol. 14, Page 4781 2021, 14, 4781. [CrossRef]

- Jivkov, V.; Simeonova, R.; Antov, P.; Marinova, A.; Petrova, B.; Kristak, L. Structural Application of Lightweight Panels Made of Waste Cardboard and Beech Veneer. Mater. 2021, Vol. 14, Page 5064 2021, 14, 5064. [CrossRef]

- FAO Forestry Production and Trade. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Barbu, M.C.; Reh, R.; Çavdar, A.D. Non-Wood Lignocellulosic Composites. In Materials Science and Engineering: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global, 2017; pp. 947–977.

- Youngquist, J.A. Wood-Based Composites and Panel Products. Wood Handbook—Wood as an Eng. Mater. 1999, 1–31.

- Youngquist, J.A. Wood-Based Panels: Their Properties and Uses. A Review. 1987.

- Karimah, A.; Ridho, M.R.; Munawar, S.S.; Adi, D.S.; Damayanti, R.; Subiyanto, B.; Fatriasari, W.; Fudholi, A. A Review on Natural Fibers for Development of Eco-Friendly Bio-Composite: Characteristics, and Utilizations. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 2442–2458. [CrossRef]

- Bekhta, P. Recent Developments in Eco-Friendly Wood-Based Composites II. Polym. 2023, Vol. 15, Page 1941 2023, 15, 1941. [CrossRef]

- Mursalin, R.; Islam, M.W.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Zaman, M.F.; Azmain Abdullah, M. Fabrication and Characterization of Natural Fiber Composite Material. Int. Conf. Comput. Commun. Chem. Mater. Electron. Eng. IC4ME2 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- Dicker, M.P.M.; Duckworth, P.F.; Baker, A.B.; Francois, G.; Hazzard, M.K.; Weaver, P.M. Green Composites: A Review of Material Attributes and Complementary Applications. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2014, 56, 280–289. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, G.S.; Andrew, J.J.; Arockiarajan, A. Experimental Investigation on Compressive Behaviour of Different Patch–Parent Layup Configurations for Repaired Carbon/Epoxy Composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2019, 53, 3269–3279. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.D.; Fuller, M.J. Kenaf Core as a Board Raw Material. For. Prod. J. 1993, 43, 69.

- Kalaycioglu, H.; Nemli, G. Producing Composite Particleboard from Kenaf (Hibiscus Cannabinus L.) Stalks. Ind. Crops Prod. 2006, 24, 177–180. [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.J.; Kamal, I. Kenaf Core Particleboard and Its Sound Absorbing Properties. J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 4.

- Atoyebi, O.D.; Osueke, C.O.; Badiru, S.; Gana, A.J.; Ikpotokin, I.; Modupe, A.E.; Tegene, G.A. Evaluation of Particle Board from Sugarcane Bagasse and Corn Cob. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2019, 10, 1193–1200.

- Silva, M.R.; Pinheiro, R.V.; Christoforo, A.L.; Panzera, T.H.; Rocco Lahr, F.A. Hybrid Sandwich Particleboard Made with Sugarcane, Pínus Taeda Thermally Treated and Malva Fibre from Amazon. Mater. Res. 2017, 21, e20170724. [CrossRef]

- Buzo, A.L.S.C.; Silva, S.A.M.; De Moura Aquino, V.B.; Chahud, E.; Branco, L.A.M.N.; De Almeida, D.H.; Christoforo, A.L.; Almeida, J.P.B.; Lahr, F.A.R. Addition of Sugarcane Bagasse for the Production of Particleboards Bonded with Urea-Formaldehyde and Polyurethane Resins. Wood Res. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.F.; Mendes, L.M.; JÚNIoR, J.Benedit.G.; dos Santos, R.C.; Bufalino, L. The Adhesive Effect on the Properties of Particleboards Made from Sugar Cane Bagasse Generated in the Distiller. Rev. Ciências Agrárias 2009, 32, 209–218.

- Mendes, R.F.; Mendes, L.M.; Oliveira, S.L.; Freire, T.P. Use of Sugarcane Bagasse for Particleboard Production. Key Eng. Mater. 2015, 634, 163–171. [CrossRef]

- Silva Brito, F.M.; Bortoletto Júnior, G.; Surdi, P.G. Properties of Particleboards Made from Sugarcane Bagasse Particles. Brazilian J. Agric. Sci. Bras. Ciências Agrárias 2021, 16. [CrossRef]

- Magzoub, R.; Osman, Z.; Tahir, P.; Nasroon, T.H.; Kantner, W. Comparative Evaluation of Mechanical and Physical Properties of Particleboard Made from Bagasse Fibers and Improved by Using Different Methods. Cellul. Chem. Technol 2015, 49, 537–542.

- Ahmadi, P.; Efhamisisi, D.; Thévenon, M.-F.; Hosseinabadi, H.Z.; Oladi, R.; Gerard, J. Chemically Modified Sugarcane Bagasse for Innovative Bio-Composites. Part One: Production and Physico-Mechanical Properties. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 1715–1728. [CrossRef]

- Zvirgzds, K.; Kirilovs, E.; Kukle, S.; Gross, U. Production of Particleboard Using Various Particle Size Hemp Shives as Filler. Mater. 2022, Vol. 15, Page 886 2022, 15, 886. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, E.; Chrysafi, I.; Karidi, K.; Mitani, A.; Bikiaris, D.N. Particleboards with Recycled Material from Hemp-Based Panels. Materials (Basel). 2023, 17, 139. [CrossRef]

- Fehrmann, J.; Belleville, B.; Ozarska, B.; Gutowski, W. (Voytek) S.; Wilson, D. Influence of Particle Granulometry and Panel Composition on the Physico-mechanical Properties of Ultra-low-density Hemp Hurd Particleboard. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 7363–7383. [CrossRef]

- Rimkienė, A.; Vėjelis, S.; Kremensas, A.; Vaitkus, S.; Kairytė, A. Development of High Strength Particleboards from Hemp Shives and Corn Starch. Mater. 2023, Vol. 16, Page 5003 2023, 16, 5003. [CrossRef]

- Alao, P.; Tobias, M.; Kallakas, H.; Poltimäe, T.; Kers, J.; Goljandin, D. Development of Hemp Hurd Particleboards from Formaldehyde-Free Resins. 2020.

- Placet, V. Characterization of the Thermo-Mechanical Behaviour of Hemp Fibres Intended for the Manufacturing of High Performance Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2009, 40, 1111–1118. [CrossRef]

- Auriga, R.; Pędzik, M.; Mrozowski, R.; Rogoziński, T. Hemp Shives as a Raw Material for the Production of Particleboards. Polym. 2022, Vol. 14, Page 5308 2022, 14, 5308. [CrossRef]

- Kukle, S.; Putnina, A.; Gravitis, J. Hemp Fibres and Shives, Nano-and Micro-Composites. Sustain. Dev. Knowl. Soc. Smart Futur. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 291–305.

- Nguyen, Q. How Sustainable Is Particle Board (LDF)? Here Are the Facts | Impactful Ninja Available online: https://impactful.ninja/how-sustainable-is-particle-board-ldf/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Lykidis, C.; Grigoriou, A. Hydrothermal Recycling of Waste and Performance of the Recycled Wooden Particleboards. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Rammou Aikaterini; Mitani Andromachi; Dimitrios Koutsianitis; Ntalos Geogios Mechanical and Physical Properties of Particleboards Made from Different Mixtures of Industrial Hemp ( Cannabis Sativa L .) and Wood. 2019, 3, 359–362. [CrossRef]

- Iždinský, J.; Vidholdová, Z.; Reinprecht, L. Particleboards from Recycled Wood. For. 2020, Vol. 11, Page 1166 2020, 11, 1166. [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, S.; Bougherara, H. A Comprehensive Review on Surface Modification of UHMWPE Fiber and Interfacial Properties. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2021, 140, 106146. [CrossRef]

- Martínez Suárez, C.; Rojas Montejo, P.; Gutiérrez Junco, O. Effects of Alkaline Treatments on Natural Fibers. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2046, 012056. [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S.J.; Saravanan, R.; Anbuchezhiyan, G. An Overview on Chemical Treatment in Natural Fiber Composites. Mater. Today Proc. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pankaj; Jawalkar, C.S.; Kant, S. Critical Review on Chemical Treatment of Natural Fibers to Enhance Mechanical Properties of Bio Composites. Silicon 2022, 14, 5103–5124.

- Gonçalves, D.; Bordado, J.M.; Marques, A.C.; Dos Santos, R.G. Non-Formaldehyde, Bio-Based Adhesives for Use in Wood-Based Panel Manufacturing Industry—A Review. Polym. 2021, Vol. 13, Page 4086 2021, 13, 4086. [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K.; Franciszczak, P.; Osman, Z.; Elbadawi, M. Polypropylene Biocomposites Reinforced with Softwood, Abaca, Jute, and Kenaf Fibers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 70, 91–99. [CrossRef]

- BS EN Wood-Based Panels. Sampling, Cutting and Inspection. Part 1, Sampling and Cutting of Test Pieces and Expression of Test Results, BS EN 326. 1994, 16.

- BS EN Particleboards and Fibreboards : Determination of Tensile Strength Perpendicular to the Plane of the Board, BS EN 319. 1993, 6.

- BS EN Wood-Based Panels - Determination of Modulus of Elasticity in Bending and of Bending Strength, BS EN 310 Available online: https://www.en-standard.eu/une-en-310-1994-wood-based-panels-determination-of-modulus-of-elasticity-in-bending-and-of-bending-strength/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- BS EN Particleboards and Fibreboards - Determination of Swelling in Thickness after Immersion in Water, BS EN 317 Available online: https://www.en-standard.eu/une-en-317-1994-particleboards-and-fibreboards-determination-of-swelling-in-thickness-after-immersion-in-water/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- EN Particleboards - Specifications - Part 6: Requirements for Heavy Duty Load-Bearing, EN 312-6 Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/5f877ca1-15a9-4752-b1a3-5d8658a5268c/en-312-6-1996?srsltid=AfmBOoodzE5Q4rXB_xMLcxVEkWiCRt_YcBZTv-7r28b6ecXV8_Ozeix6 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Osman, Z.; Elamin, M.; Ghorbel, E.; Charrier, B. Influence of Alkaline Treatment and Fiber Morphology on the Mechanical, Physical, and Thermal Properties of Polypropylene and Polylactic Acid Biocomposites Reinforced with Kenaf, Bagasse, Hemp Fibers and Softwood. Polym. 2025, Vol. 17, Page 844 2025, 17, 844. [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, F.; Fahmy, Y.; Augustin, H. Binderless Lignocellulose Composite from Bagasse and Mechanism of Self-Bonding. 1982. [CrossRef]

- Widyorini, R.; Xu, J.; Umemura, K.; Kawai, S. Manufacture and Properties of Binderless Particleboard from Bagasse I: Effects of Raw Material Type, Storage Methods, and Manufacturing Process. J. Wood Sci. 2005, 51, 648–654. [CrossRef]

- Milagres, E.G.; Barbosa, R.A.G.S.; Caiafa, K.F.; Gomes, G.S.L.; Castro, T.A.C.; Vital, B.R. Properties of Particleboard Panels Made of Sugarcane Particles with and without Heat Treatment. Rev. Árvore 2019, 43, e430502. [CrossRef]

- Kusumah, S.S.; Umemura, K.; Guswenrivo, I.; Yoshimura, T.; Kanayama, K. Utilization of Sweet Sorghum Bagasse and Citric Acid for Manufacturing of Particleboard II: Influences of Pressing Temperature and Time on Particleboard Properties. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 161–172. [CrossRef]

- Nikvash, N.; Kraft, R.; Kharazipour, A.; Euring, M. Comparative Properties of Bagasse, Canola and Hemp Particle Boards. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2010, 68, 323–327. [CrossRef]

- EN Particleboards - Specifications - Part 4: Requirements for Load-Bearing Boards for Use in Dry Conditions, EN 312. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/1c838d7a-5d6b-46d8-9cc5-90623beec403/en-312-4-1996?srsltid=AfmBOoo_dVv1AmxBvJy5QLLmR-FQ0xG7wxPWltjZ4BS6aKd59bdD8K87 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Schopper, C.; Kharazipour, A.; Bohn, C. Production of Innovative Hemp Based Three-Layered Particleboards with Reduced Raw Densities and Low Formaldehyde Emissions. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol. 2009, 36, 358–371. [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.-B.A.; Basta, A.H.; El-Saied, H. Evaluation of Palm Fiber Components an Alternative Biomass Wastes for Medium Density Fiberboard Manufacturing. Maderas. Cienc. y Tecnol. 2018, 20, 579–594. [CrossRef]

- Moulana, R. Utilization of Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) as an Alternative Raw Material for the Production of Three-Layered Particleboard. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of The Annual International Conference, Syiah Kuala University-Life Sciences & Engineering Chapter; 2012; Vol. 2.

- Saad, M.J.; Kamal, I. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Low Density Kenaf Core Particleboards Bonded with Different Resins. J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 4.

- Yu, H.-X.; Fang, C.-R.; Xu, M.-P.; Fei, •; Guo, Y.; Yu, W.-J. Effects of Density and Resin Content on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Scrimber Manufactured from Mulberry Branches. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, N.D.; Narciso, C.R.P.; Felix, A. de L.; Mendes, R.F. Pressing Temperature Effect on the Properties of Medium Density Particleboard Made with Sugarcane Bagasse and Plastic Bags. Mater. Res. 2022, 25, e20210491. [CrossRef]

- Hiranobe, C.T.; Gomes, A.S.; Paiva, F.F.G.; Tolosa, G.R.; Paim, L.L.; Dognani, G.; Cardim, G.P.; Cardim, H.P.; dos Santos, R.J.; Cabrera, F.C. Sugarcane Bagasse: Challenges and Opportunities for Waste Recycling. Clean Technol. 2024, Vol. 6, Pages 662-699 2024, 6, 662–699. [CrossRef]

- de Barros Filho, R.M.; Mendes, L.M.; Novack, K.M.; Aprelini, L.O.; Botaro, V.R. Hybrid Chipboard Panels Based on Sugarcane Bagasse, Urea Formaldehyde and Melamine Formaldehyde Resin. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 369–373. [CrossRef]

- Nosbi, N., Akil, H. M., Mohd Ishak, Z. A., and Abu Baker, A. (2011). “Behavior of kenaf fibers after immersion in several water conditions,” BioRes. 6( 2), 950-960. [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, D.; Leitch, M.; Fatehi, P. Lignin–Carbohydrate Complexes: Properties, Applications, Analyses, and Methods of Extraction: A Review. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018 111 2018, 11, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Alwadani, N.; Ghavidel, N.; Fatehi, P. Surface and Interface Characteristics of Hydrophobic Lignin Derivatives in Solvents and Films. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 609, 125656. [CrossRef]

| Fibers | Mean Density(kg/m³) Values |

| Kenaf | 671.20 |

| Bagasse | 662.40 |

| Hemp | 604.70 |

| Wood | 691.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).