1. Introduction

Despite the development of many new wood materials, plywood is still valuable in many industries [

1], including construction, furniture, and automotive sectors, due to its favorable strength-to-weight ratio and versatile properties [

2]. However, traditional plywood often faces mechanical strength, durability, and moisture resistance limitations, necessitating the development of enhanced composite materials [

3]. A plywood composite consists of at least two layers of outer laminate, separated by an inner laminate [

4]. The outer layers can be relatively thin - from about one millimeter, while the core layer can range from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Such composites are characterized by high strength properties, low specific weight, relatively low production costs, and high durability [

5]. A big problem in plywood production is the formaldehyde release, especially from urea-formaldehyde-bonded plywood [

6]. The technology used in plywood production has not changed for over a century. However, research is constantly being conducted to improve its quality [

7]. On a daily basis, the furniture industry uses adhesives with the addition of various fillers for plywood production. They improve the physical, mechanical, technological, and operational properties. Components are increasingly subject to modifications - veneers and adhesives but also fillers [

8]. Veneer impregnation has also been explored to improve fire resistance, given the use of appropriate measures [

9]. With increasing public awareness and emphasis on eco-friendly behavior, the wood industry is forced to use more environmentally friendly practices. This has led to various attempts to replace formaldehyde-based thermosetting resins with natural-origin adhesives. For instance, glutaraldehyde-modified starch has been considered an alternative binder in plywood technology, with studies confirming its effectiveness [

10]. Wood bark has also been used as a filler to minimize free formaldehyde emissions [

3,

11]. Green tea leaves have demonstrated a similar ability to reduce formaldehyde emissions when used as a filler [

12].

Nonwoven fabrics are characterized by their high porosity, flexibility, and ability to form interfacial solid bonds with other materials [

13]. These characteristics make them suitable for reinforcing layered composites such as plywood [

14]. Urea-formaldehyde resin, commonly used as an adhesive in plywood manufacturing [

15], provides good bonding strength and durability, further improving the composite's performance when combined with nonwoven fabrics.

Integrating nonwoven fabrics into composite materials has enhanced their properties significantly. An essential aspect of using nonwoven fabric in producing fiberboards is its impact on the bonding process of these boards. Considering the production process of these materials, it may turn out that they are not chemically inert, and their characteristics can be variable. However, the Acid Buffering Capacity (ABC) parameter can be applied in wood technology, which may help adjust the production parameters if such a non-inert material causes issues [

16]. Consequently, this does not pose a risk of necessitating the development of additional techniques and methods. Nonwoven fabrics, particularly upholstery nonwoven, are characterized by their high porosity, flexibility, and ability to form interfacial solid bonds with other materials, making them suitable for reinforcing layered composites such as plywood [

17]. Plywood composites, including nonwoven fabrics, can lead to better stress distribution and bonding between layers, enhancing overall performance [

18].

Nonwoven fabrics have unique structural characteristics due to their manufacturing process, which involves bonding fibers together without weaving, knitting, or stitching. These fabrics offer several advantages, such as improved tensile strength, impact resistance, and dimensional stability, which are critical for enhancing the properties of plywood composites [

19]. Specifically, needle-punched nonwoven fabrics have shown promise in reinforcing polymer composites due to their ability to distribute stress uniformly and provide better mechanical interlocking [

20].

To investigate the potential of nonwoven fabric-reinforced plywood composites, this study focuses on manufacturing and testing several board variants with different positions of nonwoven layers. The mechanical properties, including modulus of rupture (MOR), modulus of elasticity (MOE), and screw withdrawal resistance (SWR), were evaluated. Additionally, density and density profile measurements, thickness swelling, and water absorption were conducted to assess the physical properties of the composites. Industrial layered composites were used as reference materials to benchmark the performance of the nonwoven reinforced composites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials.

These studies concerned the production of five-layered plywood using rotary-cut birch veneers (Betula spp.). The veneers had a thickness of 1.8 mm, moisture content (MC) of approximately 6%, and dimensions of 300 mm × 300 mm.

The binder was industrial urea-formaldehyde (UF) resin Silekol S-123 (Silekol Sp. z o. o., Kędzierzyn-Koźle, Poland). Additionally, an ammonium nitrate water solution was used as a hardener when subjected to a temperature of 100 °C to reach the curing time of about 86 s. In addition, rye flour (PPHU JS, Magnoliowa St. 2/11, 15-669 Białystok, Poland) was used as a bonding mass filler.

The nonwoven fabric used in the tests was from PPHU "ADAX" (Topola Szlachecka 21, 99-100 Łęczyca, Poland). It is a two-component polyester fiber with a low melting point in white and a 200 g m

−2 grammage fire-resistant fiber. The nonwoven fabric was a post-production waste of irregular shapes and dimensions from the production of upholstered furniture (

Figure 1). The obtained pieces of various sizes were used to form 300 mm × 300 mm mats.

2.2. Preparation of Panels.

A five-layer reference plywood glued with urea-formaldehyde (UF) resin with hardener, demineralized water, and flour filler was produced as part of the research. The adhesive mixture was prepared in parts by weight (pbw): 100:10:16:5 (resin: hardener: filler: water). A brush was applied to the adhesive mix spread to the veneers in 180 g m−2 per single bonding line. Whenever nonwoven fabric appeared between veneers, the glue mass has been spread to both surfaces surrounding the fabric. The veneers were stacked alternately and then pressed in a heated hydraulic press (AKE, Mariannelund, Sweden) for 7 min at a pressing temperature of 140 °C and a maximum unit pressing pressure of 1.2 MPa. After pressing, the samples were conditioned at 20 ± 1 °C and 65 ± 2% relative humidity for seven days to stabilize the mass before testing.

The amount and distribution of nonwoven layers differentiated the panels (

Table 1). Five different variants were created with layers of nonwoven fabric at various locations. The reference panels (hereafter: REF) have also been produced, with no nonwoven fabric added.

2.3. Characterization of the Elaborated Panels.

Mechanical tests were performed on a computer-controlled universal testing machine (Ośrodek Badawczo-Rozwojowy Przemysłu Płyt Drewnopochodnych Sp. Z o.o., Czarna Woda, Poland). The following tests were carried out: modulus of rupture (MOR) and modulus of elasticity (MOE), conducted in accordance with current standard [

21]. In addition, a screw withdrawal resistance test [

22] and an internal bond (IB) test [

23] have been completed. Using the test procedure specified in the standard for particleboard and fiberboard, the swelling thickness after immersion in water was determined, and analysis was carried out for all variants [

24]. In addition, a water absorption test was conducted on the samples used for the thickness swelling test. Each test was performed for six repetitions. The density profile was also obtained for all variants (three replicates from each variant) using a Grecon DAX 5000 instrument (Fagus-GreCon Greten GmbH and Co. KG, Alfeld/Hannover, Germany), based on X-ray technology, with a sampling step of 0.02 mm and a measurement speed of 0.1 mm s

−1.

2.4. Statistical Analysis.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-test calculations were conducted to identify significant differences (α = 0.05) between factors and levels when applicable, using the IBM SPSS statistic base (IBM, SPSS20, Armonk, NY, USA). The homogenous groups are indicated in

Table 2. The results shown in the graphs represent mean values and standard deviation as error bars.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Modulus of Rupture and Modulus of Elasticity.

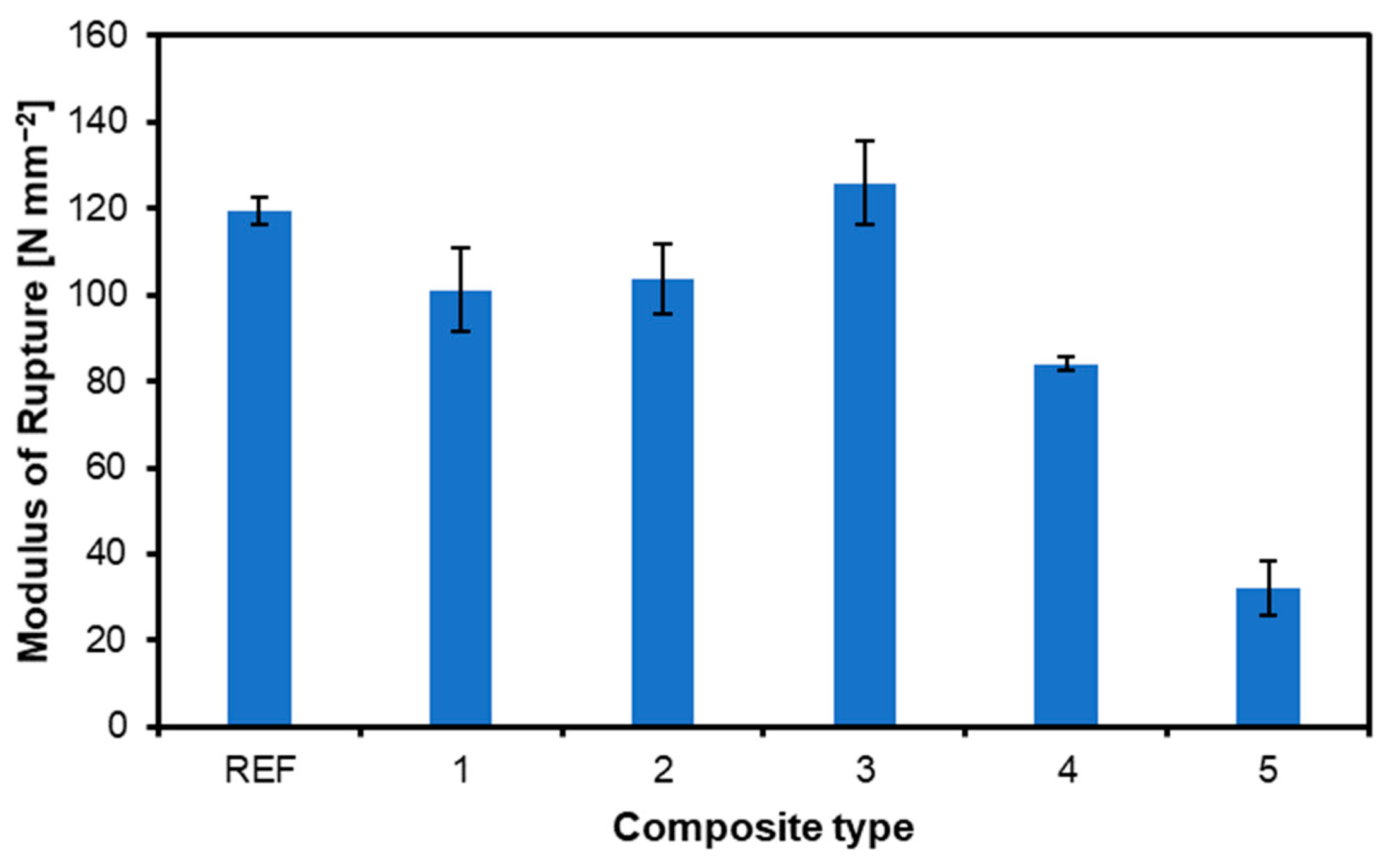

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the dependence of the modulus of rupture and modulus of elasticity on the content and location of nonwoven layers, respectively. It can be seen that the content of nonwoven layers does not drastically change the results, and surprisingly, in most cases

, it even worsens them. For the reference sample, the MOR value is 119 N mm

−2, and for variant 3 (nonwoven fabric mat located under face veneers only), it is 126 N mm

−2. The lowest value was obtained for variant 5 with non-woven fabric content. No rule showing a decreasing or increasing tendency in strength for the number of nonwoven fabric layers can be deduced here. Dasiewicz and Wronka [

25] obtained a similar lack of dependence

: the highest MOR for the reference sample and the lowest for the sample with 1% chestnut flour filler content. A study conducted by Asgari et al. [

26] yielded intriguing results regarding the properties of polypropylene/poplar flour composites enhanced with microcrystalline cellulose and starch powder. The research found that incorporating microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) and starch powder (SP) into the composites led to an increase in the modulus of rupture (MOR). Notably, the sample with the highest weight percentage of MCC and SP exhibited the greatest MOR, demonstrating the significant impact of these additives on the composite’s strength.

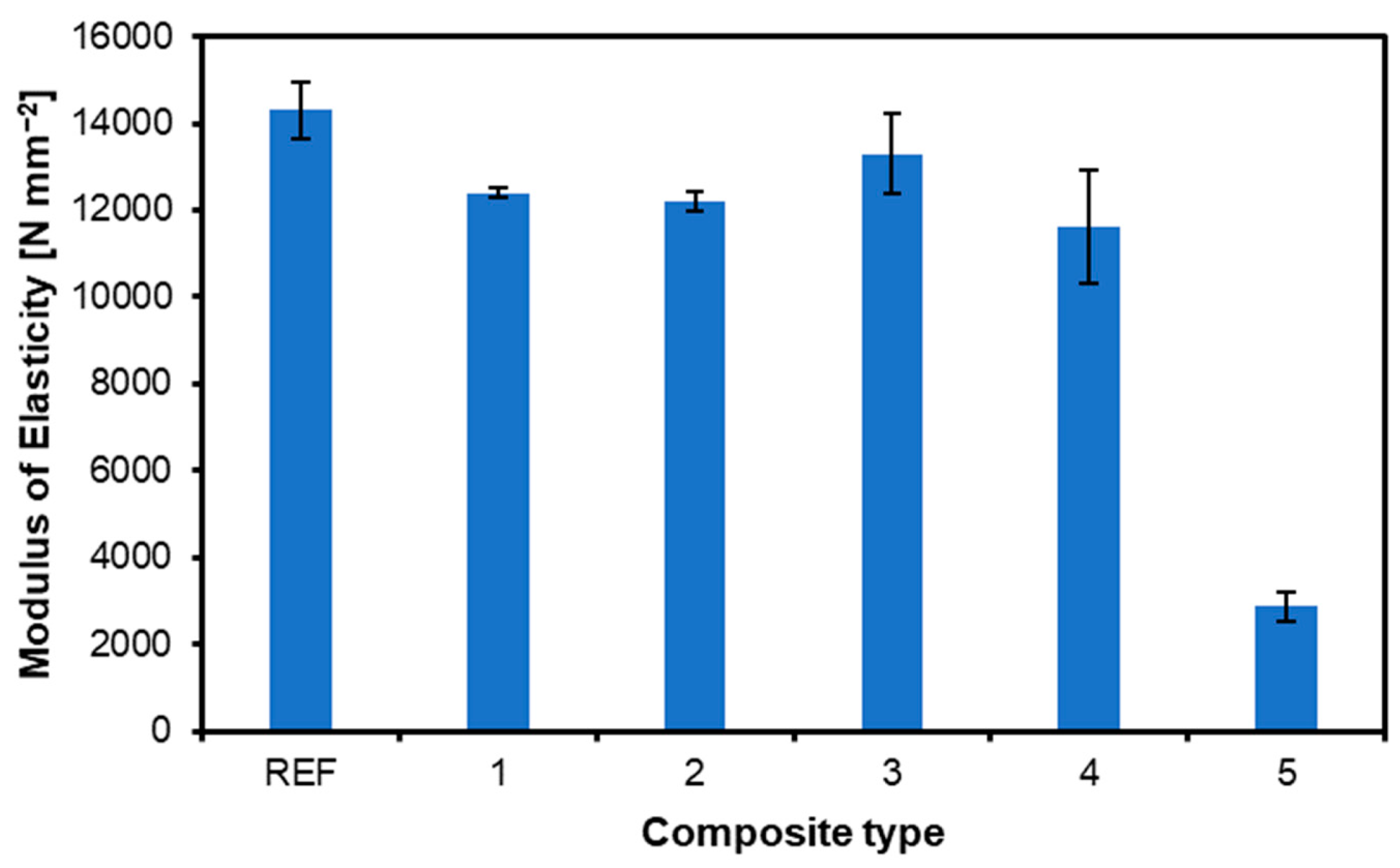

In the case of MOE (

Figure 2), the reference sample achieved the best result without adding upholstery nonwoven fabric (14308 N mm

−2). The lowest MOE value again occurs for variant 5 nonwoven content in the board – 2873 N mm

−2. The only relationship when comparing the MOR and MOE results appears in the reference sample and the sample of variant 5 as the highest and lowest results. However, analyzing the remaining variants with the addition of nonwoven layers, it can be concluded that variants 1 – 4 have very similar MOE scores. However, Bal and Bektas [

27], comparing the properties of plywood made of poplar, eucalyptus, and beech, obtained increased flexibility after changing the plywood structure. These conclusions are consistent with the results of previous research by Biadała et al. [

28].

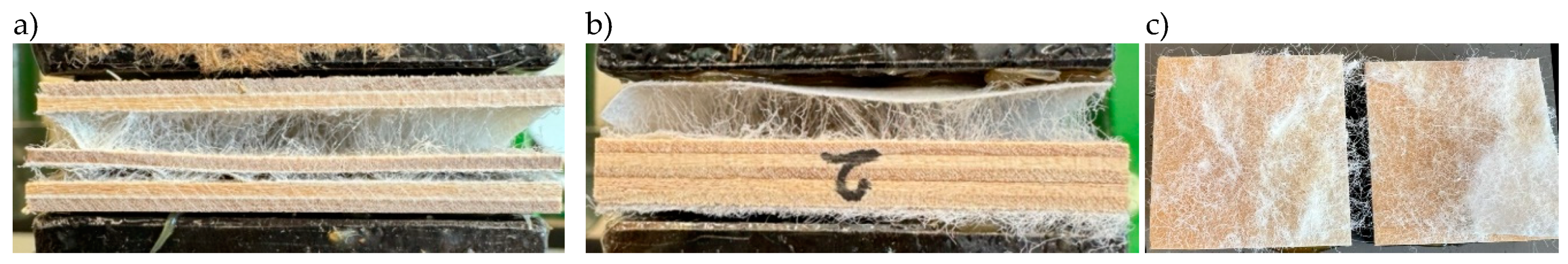

3.2. Internal Bond and Screw Withdrawal Resistance.

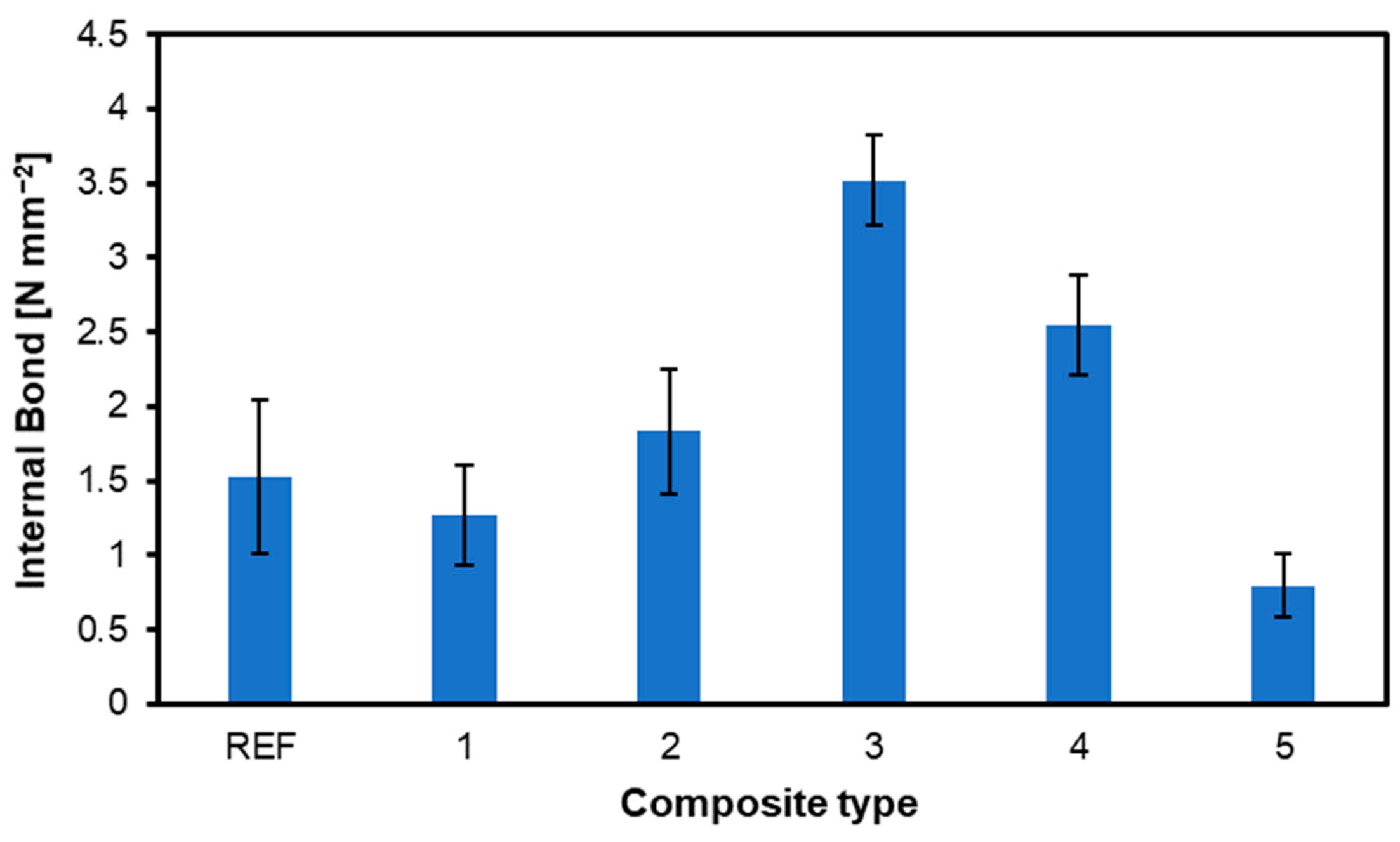

The results of internal bond strength measurements are shown in

Figure 4. Internal bonding, according to EN 319 [

23], is designed to test materials based on wood particles. It is considered a simple test and can be used to evaluate the perpendicular tensile strength of plywood [

29]. As can be seen in the figure, the highest strength was obtained by the sample of the third type, which had two reinforcing layers of nonwoven fabric, and its strength was 3.52 N mm

−2. The second sample that obtained the highest strength is the sample of the fourth type, which received 2.54 N mm

−2 of internal bond strength. The lowest internal bond strength was obtained by the sample of the fifth type, with a strength of only 0.8 N mm

−2. The lowest average values of panel no. 5 can be partially explained by the nonwoven fabric between all the veneers and the faces of the composite. Such a structure can influence the pressing process since the nonwoven fabric can be a thermal insulation. However, separate research should be completed to verify that theory. The examples of the tested composites’ destruction after the internal bond test have been presented in

Figure 5. As can be seen, in the case of plywood 1, built with nonwoven fabric between every veneer, the destruction occurred in the core zone, away from the surface, in the nonwoven fabric structure. The fabric structure was also damaged during the IB test of panel no. 2, where the nonwoven fabric was only present on the surface of the outer veneers. The exact figure (

Figure 5c) confirms the proper adhesion of the fabric to the veneers since the destruction after the IB test happened in the structure of the fabric. It is essential to mention the influence on the test sample during preparation and testing. First, the effect of temperature (ca. 200 °C) when gluing the samples to the aluminum metal block caused tension inside the surface layers due to sharp temperature differences. Second, the adhesive overlaps on the outside of the sample in the tensile direction. These are two potential errors in the test results, as mentioned, among other factors, by Bekir et al. (2015) [

30]. To improve and gain a deeper understanding of the strain distribution under tensile loading, it is recommended to use digital image correlation (DIC) for analysis as a value addition method, according to Li et al. (2020) [

31].

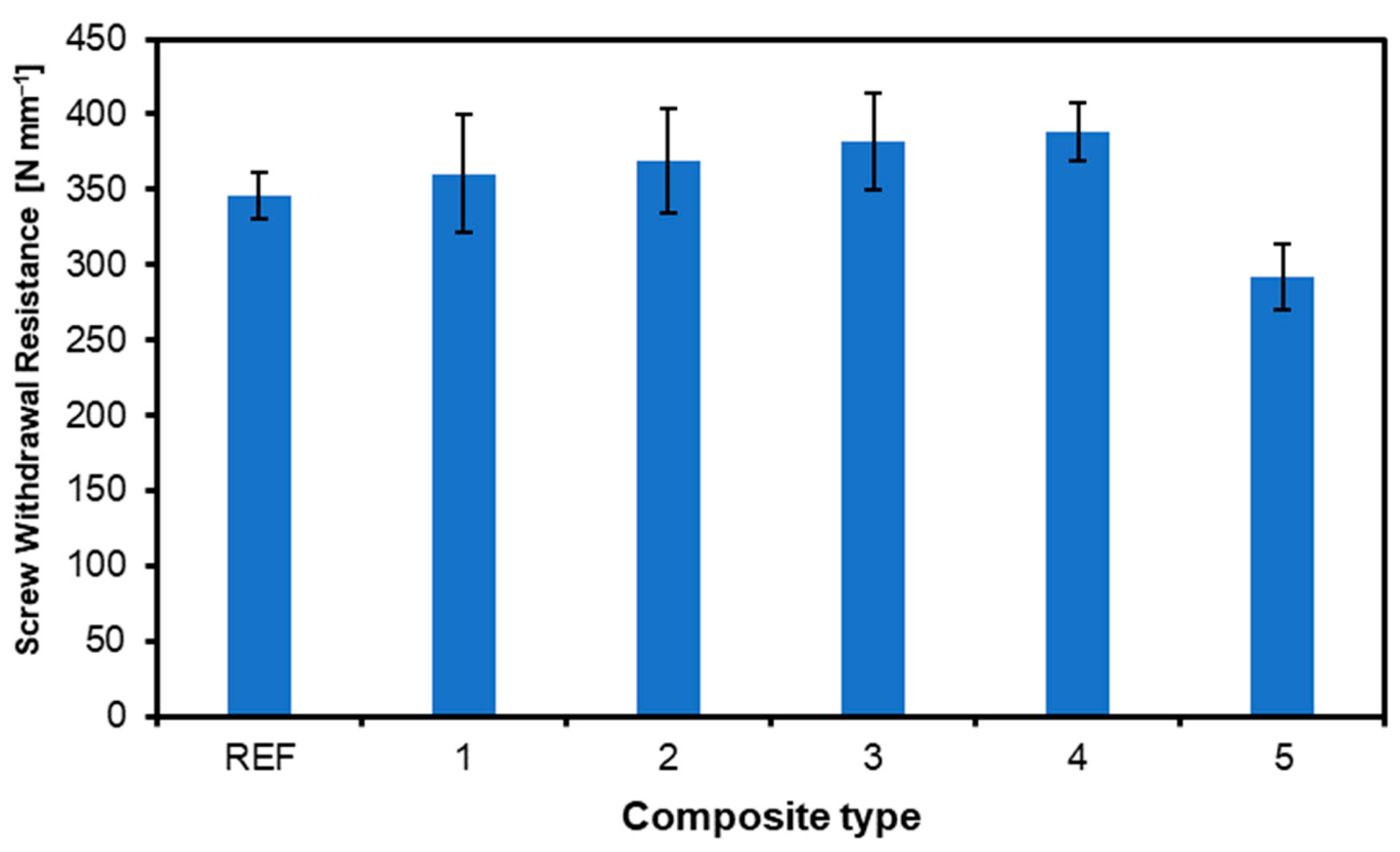

The main connecting element for wood-based materials, such as plywood or OSB, is screws. Therefore, the screw withdrawal resistance is one of the critical factors for wood-based materials used in construction [

32].

Figure 4. shows the average screw withdrawal resistances. The average resistance obtained for the reference board is 346 N mm

−2. This is neither the highest nor the lowest value obtained from the tested samples. The highest value was obtained for the sample of variant 4, which amounted to 388 N mm

−2. In contrast, the lowest value was again obtained for the variant 5 sample and was 292 N mm

−2. Some pictures of the samples during the SWR test have been presented in

Figure 7. The reference sample, which reaches one of the lowest average values of SWR, has been damaged by delamination of the face veneer. In the case of plywood 2 (

Figure 7b), where the SWR was higher than REF panels, the withdrawing screw broke the composite structure in the screw location zone. The lowest SWR average values have been registered for plywood 5, presented in

Figure 7c. It has been shown that the sample damage occurs due to delamination in the core zone. This remark is in line with the observations of the IB tests, where panel no. 5 has the lowest IB values.

The type of reinforcement provides a slight improvement for linen fabric compared to cellulose A and B. Analyzing the different fabrics; there is a slight trend where a higher amount of glue improves the screw withdrawal resistance. Pretreatment of the cellulose fabric affects this resistance. Increasing the amount of glue leads to higher density, which is consistent with the idea that density affects screw withdrawal resistance [

33], in addition to other wood-related parameters such as fiber direction, grade, moisture content, and temperature [

34]. Fiber reinforcement affects screw withdrawal resistance depending on the location of the reinforcing fabric in the board structure [

35], [

36]. The influence of specific fabric characteristics requires further research [

37].

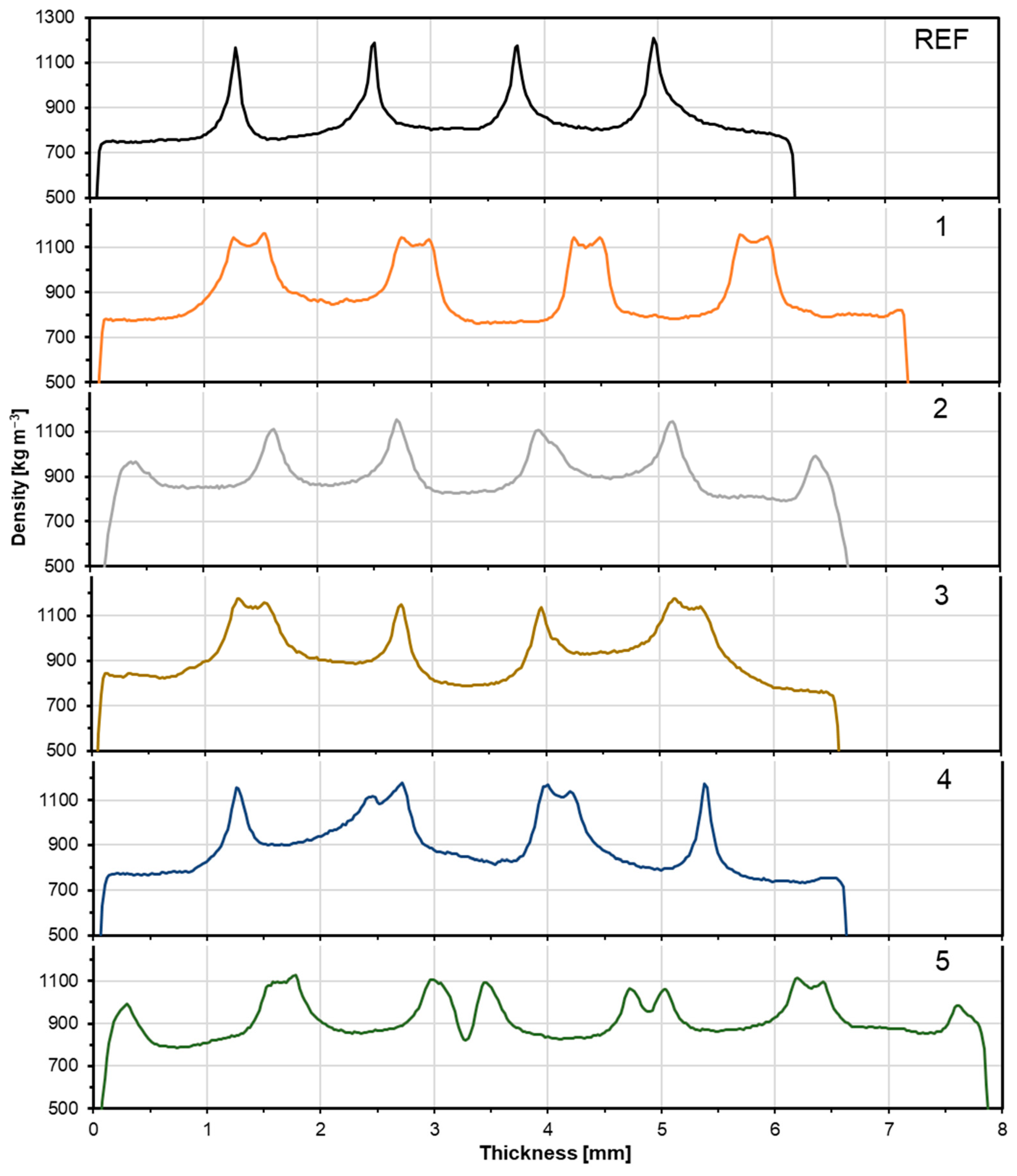

3.3. Density Profile.

Figure 8 shows the density profiles of samples with layers of upholstery nonwoven fabric with a reference variant. The veneers showed a density of about 750-800 kg m

−3, depending on the sample. The bond line showed a bond density slightly above 1200 kg m

−3 for the reference sample. The same result was obtained by Wronka and Kowaluk [

8] in a study of upcycling wood dust from recycled particleboard as filler in lignocellulosic composite technology. A similar result was obtained by Daniłowska and Kowaluk [

38] in an analysis of the use of coffee bean extraction residue as a filler in plywood technology. As for the samples reinforced with non-woven upholstery fabric, all variants have a similar bond line density and are almost identical to the reference sample, which is about 1200 kg m

−3. Differences in bond line densities within the same variant were also observed, which can be explained by excessively high viscosity during adhesive application, resulting in uneven bonding. In Bartoszuk and Kowaluk’s [

39] research on HDF board with the addition of natural leather, the density value in the core layer increased to about 880 kg m

−3 at 10% leather particle content. In contrast, at 0% leather addition, it is about 810 kg m

−3. As the proportion of leather particle fibers increases, the density difference between the boards' surface and core layers decreases. This observation aligns with studies on incorporating textile fibers into HDF boards [

40].

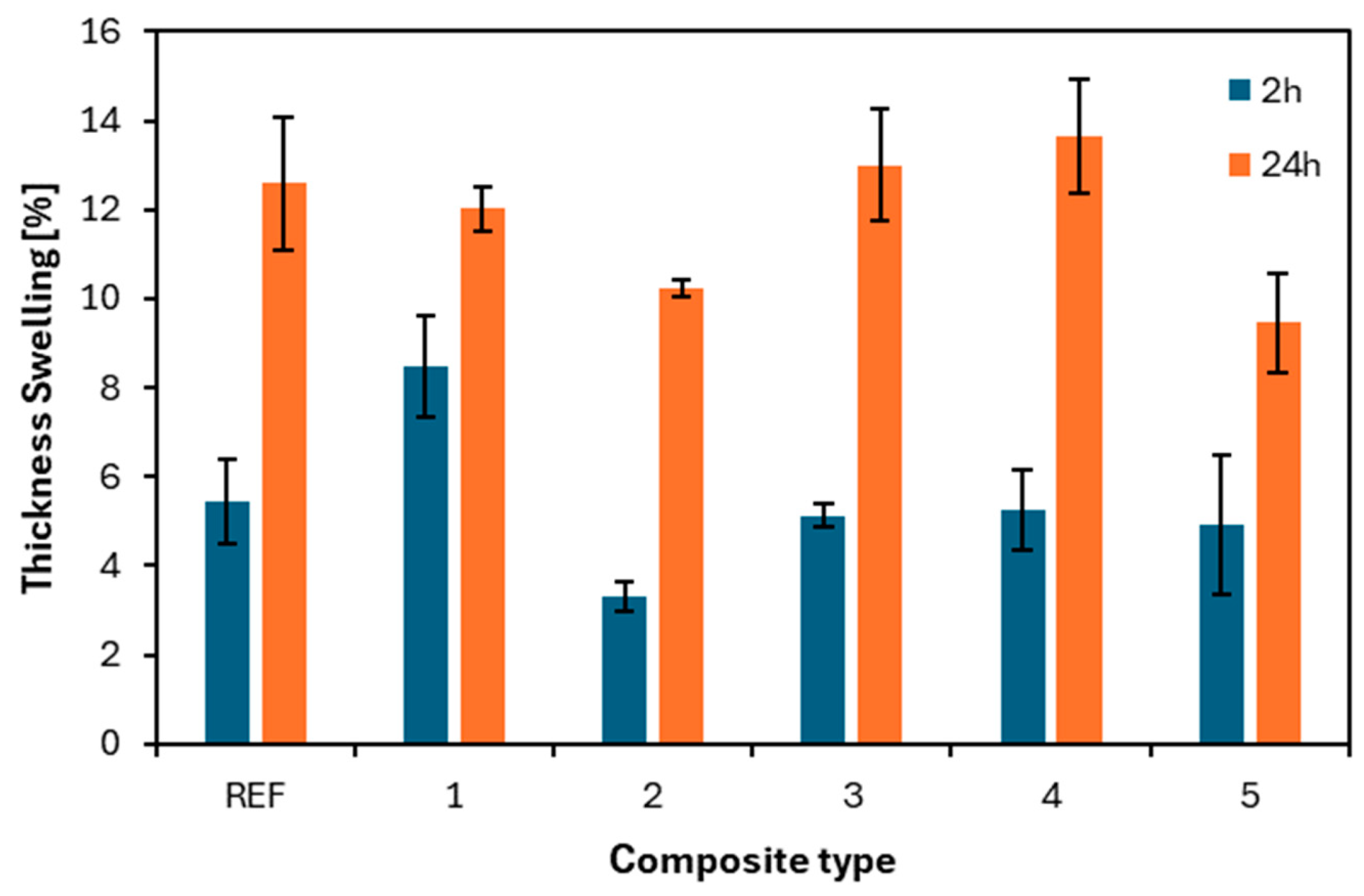

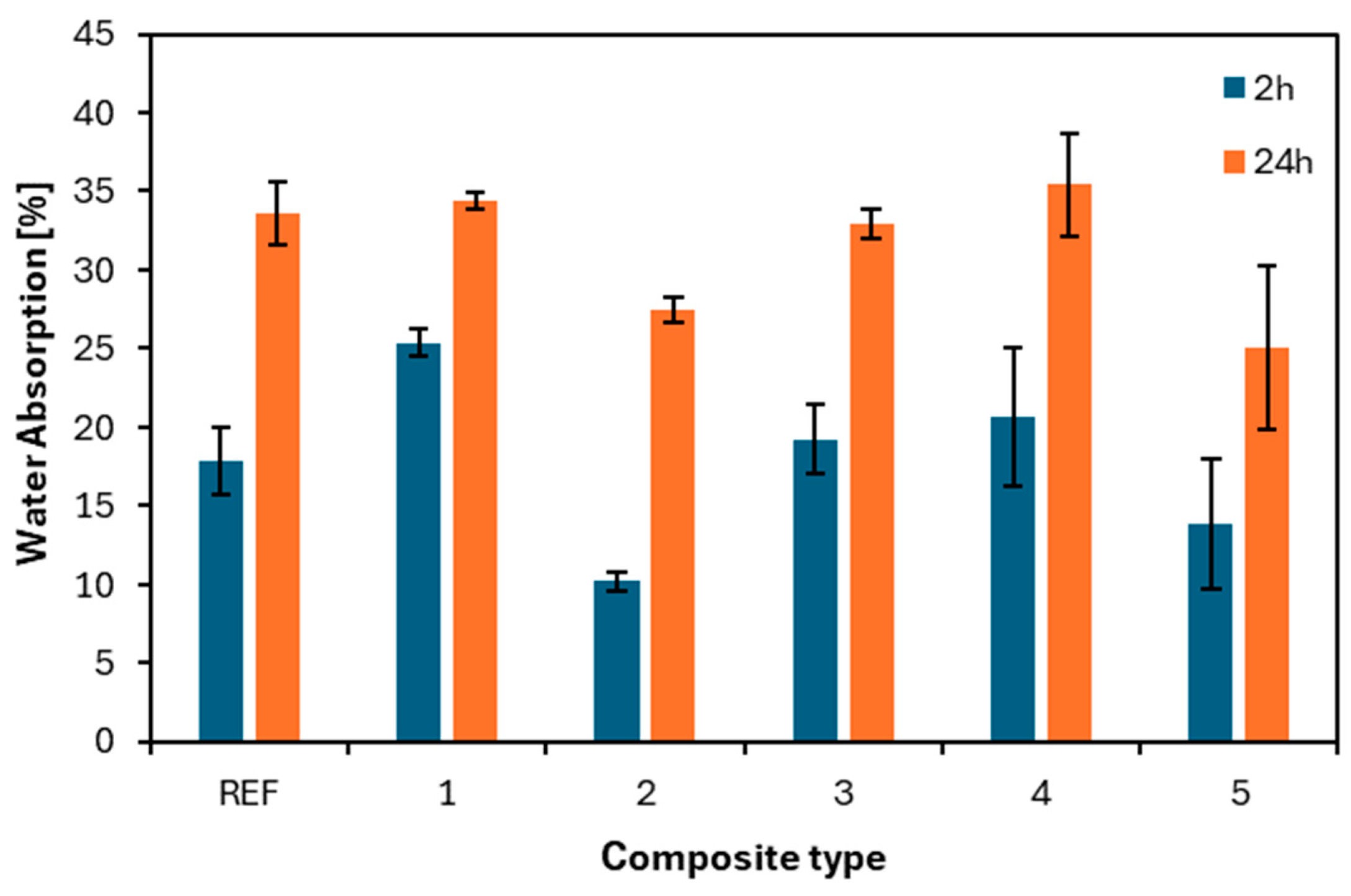

3.4. Thickness Swelling and Water Absorption.

The results of thickness swelling and water absorption are shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, respectively. After 24 hours of soaking, the intensity of the thickness swelling results was more pronounced in all samples than after 2 hours. The lowest values after two hours and 24 hours were in the samples whose outer layers were nonwoven upholstery layers. This can only indicate the positive effect of the nonwoven fabric on the plywood and its reinforcing properties. After two hours, the reference board had a swelling value of 5.4%; after 24 hours, it was already 12.6%. The most significant difference in swelling per thickness after two and 24h was in the variant 4 sample, which had nonwoven layers only inside the board. The swelling value after two hours was 5.3%, and after 24 hours, it was already 13.6%. The works of Buzo et al. [

41] and Sugahara et al. [

42] also found lower thickness swelling values for particleboards made of PU compared to formaldehyde-based resins.

The results of water absorption of the tested panels with different arrangements of nonwoven fabric layers are shown in

Figure 10. The time after 24h is very close to each other in each type of sample, even the reference one. On the other hand, the samples' values after two hours are more diverse. The variant 2 sample obtained the lowest value, 10.2%, and its value after 24h was 27.5%. In contrast, the variant 1 sample obtained the highest value after two hours, which received 25.4%, and its value after 24 hours was 34.4%.

Treatment with CCA (copper chromate and arsenate) reduced water absorption for both adhesives used in the study “Comparative Study of Plywood Boards Produced with Castor Oil-Based Polyurethane and Phenol-Formaldehyde Using

Pinus taeda L. Veneers Treated with Chromated Copper Arsenate” [

43]. This is due to filling voids in the wood with salts [

44]. PU resin showed lower water absorption than PF in reference and CCA-treated samples. A study by Setter et al. [

45] using different resins (phenolic and urea-formaldehyde) also showed a significant difference in water absorption. The authors concluded that PF adhesive is traditionally used in panels intended for outdoor use because of its excellent moisture resistance.

4. Conclusions

The novelty of this research is the approach to using non-wood waste from the production of upholstered furniture in wood-based composites such as plywood. The above work aimed to demonstrate the possibility of recycling waste upholstery nonwoven fabric by incorporating it into producing plywood panels. The results show that panels reinforced with nonwoven fabric on the outer layers have the most significant impact on the strength of plywood. Boards with a layer of nonwoven fabric added to the inner joints showed no substantial improvement in strength, and in some studies, even a decrease in strength was observed. Instead, an inverse relationship can be seen in the internal bond and screw withdrawal resistance tests, where higher strengths were obtained by variants with the addition of nonwoven fabric in the inner layers. Nonwoven layers do not significantly affect the density profile of the panels. The density of both the bond with adhesive alone and the bond with the addition of nonwoven fabric is very similar.

In summary, it can be concluded that upholstery nonwoven fabric is a promising additive for reinforcing plywood, especially in the outer layers. Such use is a promising result in the context of a circular economy and waste recycling principles. The use of waste from the production of upholstered furniture will, at a minimum, help solve the problem of the amount of waste generated in this industry and its management.

Author Contributions

K.B. conceptualization, resources, prepared the literature review, performed selected measurements, writing – the first draft of the paper; G.K. conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, designing the experiments and performed the experiments, data curation, analyzed the data, analyzed data statistically and reviewed and edited the final version of the paper, supervision, project administration. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has not been funded.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The mentioned research has been completed within the activity of the Student Furniture Scientific Group (Koło Naukowe Meblarstwa), Faculty of Wood Technology, Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW. The authors kindly thank BHM Sp. z o.o. Dorohuska St. 32, Srebrzyszcze, 22-100 Chełm, Poland (

https://www.bhm-ui.com/en), for common care of upholstery nonwoven fabric waste valorization and providing some testing materials. The authors kindly thank M.Sc. eng. Anita Wronka, Institute of Wood Sciences and Furniture, Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Warsaw, Poland, for technical support in the investigation and manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dyrwal, P.; Borysiuk, P. Impact of Phenol Film Grammage on Selected Mechanical Properties of Plywood. Ann. WULS, For. Wood Technol. 2020, 111, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Yadama, V.; Cofer, W.F.; Englund, K.R. Analysis and Evaluation of a Fruit Bin for Apples. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 3722–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirski, R.; Kawalerczyk, J.; Dziurka, D.; Siuda, J.; Wieruszewski, M. The Application of Oak Bark Powder as a Filler for Melamine-Urea-Formaldehyde Adhesive in Plywood Manufacturing. Forests 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawska-Kupniewska, I.; Borowski, M. Selected Mechanical Properties of the Reinforced Layered Composites. Ann. WULS, For. Wood Technol. 2021, 113, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izbicka, J.; Michalski, J. Kompozyty i Laminaty - Tworzywa Stosowane w Technice. Pr. Inst. Elektrotechniki 2006, 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Nakao, T.; Nakai, T.; Gu, J.; Wang, F. Vibrational Properties of Wood Plastic Plywood. J. Wood Sci. 2005, 51, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, M.; Kowaluk, G. Waste Banana Peel Flour as a Filler in Plywood Binder. Ann. WULS, For. Wood Technol. 2023, 123, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronka, A.; Kowaluk, G. Upcycling of Wood Dust from Particleboard Recycling as a Filler in Lignocellulosic Layered Composite Technology. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Shen, Z.; Bi, H.; Shentu, B. Flame Resistance and Bonding Performance of Plywood Fabricated by Guanidine Phosphate-Impregnated Veneers. Forests 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.H.M.; Hermawan, A.; Sulaiman, N.S.; Sobri, S.A.; Demirel, G.K. Evaluation of Environmentally Friendly Plywood Made Using Glutaraldehyde Modified Starch As the Binder. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov, Ser. II For. Wood Ind. Agric. Food Eng. 2022, 15–64, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkiewicz, J.; Kawalerczyk, J.; Mirski, R.; Dziurka, D. The Application of Various Bark Species as a Fillers for UF Resin in Plywood Manufacturing. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkiewicz, J.; Kawalerczyk, J.; Mirski, R.; Szubert, Z. The Tea Leaves As a Filler for Uf Resin Plywood Production. Wood Res. 2023, 68, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukali Ozturk, M.; Venkataraman, M.; Mishra, R. Influence of Structural Parameters on Thermal Performance of Polypropylene Nonwovens. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2018, 29, 3027–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusick, G.E.; Hearle, J.W.S.; Michie, R.I.C.; Peters, R.H.; Stevenson, P.J. Physical Properties of Some Commercial Non-Woven Fabrics. J. Text. Inst. Proc. 1963, 54, P52–P74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnorowska, M.; Dziurka, D.; Fierek, A.; Mrozek, M.; Borysiuk, P.; Hikiert, M.A.; Kowaluk, G. Przewodnik Po Płytach Drewnopochodnych. Wydanie II Poprawione; Wnorowska, M., Dziurka, D., Fierek, A., Mrozek, M., Borysiuk, P., Hikiert, M.A., Kowaluk, G., Eds.; Stowarzyszenie Producentów Płyt Drewnopochodnych w Polsce, 2017; ISBN 9788393749348.

- Król, P.; Borysiuk, P.; Mamiński, M. Comparison of Methodologies for Acid Buffering Capacity Determination-Empirical Verification of Models. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, K.B.; Sabuncuoglu, B.; Yildirim, B.; Silberschmidt, V. V. A Brief Review on the Mechanical Behavior of Nonwoven Fabrics. J. Eng. Fiber. Fabr. 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrolodabaee, P.; Claramunt, J.; Ardanuy, M.; Fuente, A. de la Characterization of a Textile Waste Nonwoven Fabric Reinforced Cement Composite for Non-Structural Building Components. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 276, 122179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.M.F.; Horváth, P.G.; Alpár, T. Potential Fabric-Reinforced Composites: A Comprehensive Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 14381–14415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, P.K.; Swain, P.T.R.; Mishra, S.K.; Purohit, A.; Biswas, S. Recent Developments on Characterization of Needle-Punched Nonwoven Fabric Reinforced Polymer Composites - A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 26, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 310 Wood-Based Panels. Determination of Modulus of Elasticity in Bending and of Bending Strength; European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, Belgium, 1993.

- EN 320 Particleboards and Fibreboards - Determination of Resistance to Axial Withdrawal of Screws; European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, Belgium, 2011;

- EN 319 Particleboards and Fibreboards. Determination of Tensile Strength Perpendicular to the Plane of the Board; European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, Belgium, 1993;

- EN 317 Particleboards and Fiberboards – Determination of Swelling in Thickness after Immersion in Water; European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, Belgium, 1993;

- Dasiewicz, J.; Wronka, A. Influence of the Use of Chestnut Starch as a Binder Filler in Plywood Technology. Ann. Warsaw Univ. Life Sci. SGGW For. Wood Technol. 2023, 148, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, A.; Hemmasi, A.; Bazyar, B.; Talaeipour, M.; Nourbakhsh, A. Inspecting the Properties of Polypropylene/ Poplar Wood Flour Composites with Microcrystalline Cellulose and Starch Powder Addition. BioResources 2020, 15, 4188–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, B.C.; Bektaş, I. Some Mechanical Properties of Plywood Produced from Eucalyptus, Beech, and Poplar Veneer. Maderas Cienc. y Tecnol. 2014, 16, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biadała, T.; Czarnecki, R.; Dukarska, D. Attempt to Produce Flexible Plywood with Use of Europe Wood Species. Wood Res. 2015, 60, 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Réh, R.; Igaz, R.; Krišt’ák, L.; Ružiak, I.; Gajtanska, M.; Božíková, M.; Kučerka, M. Functionality of Beech Bark in Adhesive Mixtures Used in Plywood and Its Effect on the Stability Associated with Material Systems. Materials (Basel). 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, B.C.; Bektaş, İ.; Mengeloğlu, F.; Karakuş, K.; Ökkeş Demir, H. Some Technological Properties of Poplar Plywood Panels Reinforced with Glass Fiber Fabric | Elsevier Enhanced Reader. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, G.; Leng, W.; Mei, C. Understanding the Interaction between Bonding Strength and Strain Distribution of Plywood. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 98, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.; Kazemi Najafi, S.; Ebrahimi, G.; Ghofrani, M. Withdrawal Resistance of Screws in Structural Composite Lumber Made of Poplar (Populus Deltoides). Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 142, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Král, P.; Klímek, P.; Mishra, P.K.; Rademacher, P.; Wimmer, R. Preparation and Characterization of Cork Layered Composite Plywood Boards. BioResources 2014, 9, 1977–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddi, T.; Singh, S.K.; Nageswara Rao, B. Optimum Process Parameters for Plywood Manufacturing Using Soya Meal Adhesive. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 18739–18744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guan, M. Selected Physical, Mechanical, and Insulation Properties of Carbon Fiber Fabric-Reinforced Composite Plywood for Carriage Floors. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2019, 77, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, B.C. Propriedades de Fixação de Parafusos e Pregos Em Painéis Compensados de Madeira Reforçados Com Tecido de Fibra de Vidro. Cerne 2017, 23, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorda, J.; Kain, G.; Barbu, M.C.; Köll, B.; Petutschnigg, A.; Král, P. Mechanical Properties of Cellulose and Flax Fiber Unidirectional Reinforced Plywood. Polymers (Basel). 2022, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniłowska, A.; Kowaluk, G. The Use of Coffee Bean Post-Extraction Residues as a Filler in Plywood Technology. Ann. Warsaw Univ. Life Sci. - SGGW, For. Wood Technol. 2020, 109, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoszuk, K.; Kowaluk, G. The Influence of the Content of Recycled Natural Leather Residue Particles on the Properties of High-Density Fiberboards. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchorab, B.; Wronka, A.; Kowaluk, G. Towards Circular Economy by Valorization of Waste Upholstery Textile Fibers in Fibrous Wood-Based Composites Production. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzo, A.L.S.C.; Sugahara, E.S.; Silva, S.A. de M. da; Morales, E.A.M.; Azambuja, M. dos A. Painéis de Pínus e Bagaço de Cana Empregando-Se Dois Adesivos Para Uso Na Construção Civil. Ambient. Construído 2019, 19, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugahara, E.S.; Da Silva, S.A.M.; Laura, A.; Buzo, S.C.; De Campos, C.I.; Morales, E.A.M.; Ferreira, B.S.; Azambuja, M.D.A.; Lahr, F.A.R.; Christoforo, A.L. High-Density Particleboard Made from Agro-Industrial Waste and Different Adhesives. BioResources 2019, 14, 5162–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugahara, E.; Casagrande, B.; Arroyo, F.; De Araujo, V.; Santos, H.; Faustino, E.; Christoforo, A.; Campos, C. Comparative Study of Plywood Boards Produced with Castor Oil-Based Polyurethane and Phenol-Formaldehyde Using Pinus Taeda L. Veneers Treated with Chromated Copper Arsenate. Forests 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.S.; Silva, J.V.F.; de Campos, C.I. Static Bending Strength of Heat-Treated and Chromated Copper Arsenate-Treated Plywood. BioResources 2017, 12, 6276–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setter, C.; Zidanes, U.L.; de Novais Miranda, E.H.; Brito, F.M.S.; Mendes, L.M.; Junior, J.B.G. Influence of Wood Species and Adhesive Type on the Performance of Multilaminated Plywood. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 50835–50846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).