1. Introduction

Natural fiber reinforced polymer composites (NFRPC) have raised great interests among researchers in recent years due to the need for developing an environmentally friendly material, and partly replacing currently used glass for composite reinforcement [

1]. Natural fibers have advantages over synthetic or manmade fibers such as glass and carbon due to their low cost, low density, acceptable specific strength properties, ease of separation, carbon dioxide sequestration and biodegradability [

2]. Significant research efforts have been made and currently being spent in developing natural fiber reinforced composites, which also described as bio-composites in which either of the constituents should be derived from renewable resources [

3]. These composites have better mechanical properties like better strength to weight ratio, high modulus, high specific strength, partial biodegradability characteristics, better chemical resistance property, better insulation performance and low cost [

4,

5]. Due to this extraordinary set of properties, NFRPC have wide engineering and emerging applications [

6,

7], and therefore they became a research field continuously developing. However, researchers are facing some challenges such as the poor mechanical properties of the NFRPC associated with s known hydrophilic nature of the natural fibers Furthermore, the heterogeneous characteristics of natural fiber leading to a wide variation of fiber quality, relatively lower mechanical properties, leading to incompatibility and aggregation tendency in hydrophobic polymer matrix and low thermal stability. Thus, selection of the suitable natural fiber is the one of the most important factors that influence the performance of the NFRPC. [

8]. Currently, Kenaf and Hemp have been widely used in producing NFRPC. Both fibers are annual plants and have long bast fibers represent 40% and 70% of their stem's weight respectively [

9,

10]. On the other hand, softwood is typically preferred for thermoplastic composites due to its larger aspect ratio [

11]. Sugarcane is grown worldwide as an agricultural crop, whose residue after extracting juice is regarded as bagasse. It is available in plenty as an agro-residue and bio composites derived from such renewable resources offer potential for scale-up and value addition [

12]. Among various thermoplastic polymers, Polypropylene (PP) and polylactic acid (PLA) have emerged as an interesting matrix with moderate physical and mechanical properties. PP is widely used because of its transparency, affordability, moderate to good mechanical properties, moderate dimensional stability, low heat distortion temperature Hence, it is an obvious choice as the matrix material in the preparation of natural fiber reinforced composites [

13,

14]. Among bio-based polymers, PLA has demonstrated significant potential and commercial value across various industries. It is a compostable, transparent synthetic polymer derived from renewable resources like rice, corn starch, potatoes, sugar beets, or sugarcane. PLA is produced either through ring-opening polymerization of lactide or condensation polymerization of lactic acid [

15,

16]. PLA has attractive properties such as biodegradability, biocompatibility, mechanical strength, and its recyclability is an advantage which would reduce disposable waste and therefore economical [

17].

Much work has been done on virgin thermoplastic and natural fiber composites, with successful supporting their potential across a wide range of applications in several industrial sectors [

18]. Although these four types of natural fibers have the edge in composite manufacturing due to their robustness, however, many factors can prevent them from displaying their full potential due to resin-reinforcement incompatibility and the presence of surface impurities. Chemical treatment has been a well-known method employed to clean the surfaces of fibers and remove unwanted components, such as waxes, pectin, hemicellulose, and lignin which found to help with improving interfacial bonding with the commonly used industrial resins [

19]. A lot of work has been done by many researchers on fiber chemical treatment such as alkali, silane, acetylation, alkaline hydrogen peroxide, benzoylation, acrylation and acrylonitrile graftin and isocyanate to improve the mechanical properties of NFRPC [

20]. Out of these methods, it has been observed that one of the simplest, most economical and effective forms of treatments with least environmental impact, is alkali treatment particularly mercerization using NaOH. Much work has been done with alkali treating Kenaf with 6% of NaOH solution for 24 h. [

21] and hemp [

22] for 48 h at 20°C using different percentages for use in composites. The authors observed better fiber-matrix adhesion led to an increase in interfacial energy and thus enhancing the thermal and mechanical properties of the composites. High NaOH concentration reported to have excess delignification of fibers resulting in the weakening of the fiber, reduce the degree of polymerization, minimize lignin content and hemicellulose from the fiber. [

23]. For example, 1% of NaOH-treated bagasse fiber reinforced composites showed significant improvement in flexural, tensile, and impact strengths compared to 3 and 5% NaOH-treated fibers [

24].

Thus, it can be concluded that to improve the mechanical properties of fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites, proper fiber treatment is an effective way. However, chemical treatments can be advantageous when easily and cost-effective reagents were used without sever environmental impact and with good processability that could easily be scaled up and commercially viable such as Sodium hydroxide [

25].

In this paper, the aim was to study the effect of fibers size and alkali treatment using NaOH on the mechanical, physical and thermal properties of the injection molded PP and PLA composites reinforced with Kenaf bast fibers, Bagasse and Hemp. Their properties were compared to the softwood. A comparison was also made between the intrinsic properties of the PP, PLA and the fibers used. The major goal is therefore focused on development of sustainable and partially/completely eco-friendly thermoplastic materials based on these fibers, PP and PLA in order to obtain desired mechanical and thermal properties. The end-product made of this composite’s material may undergo both energetic and material recycling and has lower carbon footprint.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Lignocellulosic Materials

The Kenaf was planted at the demonstration farm of Khartoum University, Sudan. Kenaf bast fibers (KBF) were water retted for 10 days in open tanks and then dried at room temperature according to a method reported by Bledzki, A. et al, 2015[

17]. Bagasse was collected from White Nile Sugar Factory at Algenaid in the White Nile State, Sudan. The bagasse fibers were air dried at room temperature. Hemp fibers used in this study was of Etype SKF2, Superkurzfaser and it was purchased from Bafa neu GmbH, Germany. The softwood was supplied by Rettenmaier & Söhne GmbH + CO KG, their color was yellow and the particle size was ranging from 300 μm - 500 μm.

2.1.2. Polymer Matrices

Polypropylene (PP) from Borealis type BH345MO (injection moulding grade copolymer) was used as a matrix. This copolymer exhibits good stiffness and high fluidity of MFR= 45 g/10 min (230°C/2.16Kg). Maleic acid anhydride grafted PP wax (MAH-g-PP) from Merck of 3wt% respectively to matrix was applied as a compatibilizer between non-polar matrix and polar ligno-cellulosic fibres. Polylactic acid (PLA) of grade 3251D from Natureworks LLC was used in this study. It has tensile strength of 48.0 MPa, Flexural strength 83.0 MPa and MRF 35g/min. Impact strength 16 (J/m

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Fibers Preparation

Kenaf, bagasse and hemp fibers were further grinding using cutting Mill SM 300.

2.2.2. Fibers Treatment

All fibers were soaked in sodium hydroxide solution with 5% concentration for 1 hour. They were then thoroughly washed with tape water in order to remove any Sodium hydroxide that it might have been sticked onto their surfaces (the pH of the last wash was 7), thereafter, they were dried at 100°C for overnight prior to their blending with the matrices.

2.2.3. Fiber Shaping

The samples were tested using a flatbed scanner (Epson Perfection 4990 Photo). Each fiber sample was transferred using a wooden spatula. To prevent agglomeration, the fibers were dispersed by blowing them with a pipette. A film holder divided the scanning area into two separate sections. For image analysis, the Fibreshape software (IST AG, St. Gallen, Switzerland) was employed. The images were uploaded into the software and analyzed using a suitable measurement mask (in this case: "Example Wood Shred 1200 dpi"). The software identified and processed all fibers according to the defined algorithms. In this analysis, the minimum fiber thickness was set to 40 µm.

The fundamental measurement algorithm characterizes an (ideal) fiber as a rectangle. The chosen resolution of 1200 dpi corresponds to a resolution limit of approximately 40 µm.

2.2.4. Compounding of PP and PLA

Fibres were used with their initial moisture content (Kenaf 6.9, Bagasse 3.50, BK4090 9.46 and hemp 12.1 %). PP was processed without drying. The microfibers were mixed with PP and MAH-g-PP granulate in the hopper feeder and were conveyed to extruder's feed section (counter-rotating tight intermeshing twin-screw extruder from Krauss Maffei Berstorff ZE34 basic L/D = 46 D = 34mm). Extruded strands were cooled in water bath and palletized. Materials were compounded at temperatures ranging 190-220°C RPM.

PLA was compounding with the same fibers at same moisture content at temperature range between 165–180°C.

Process ensured good fibre distribution and even fibre/matrix ratio in order to have a homogenous density and small deviation of mechanical properties for each manufactured type of composite material. All the samples were conditioned at 23°C and 50% relative humidity for 16hrs prior performing testing.

2.2.5. Injection Moulding

Granules were injection moulded using machine model KM50-180AX (clamping force 485 kN) and moulds accordant to EN ISO 294-1[

25]. The barrel temperatures were 150-200°C from feed zone to nozzle. Injection pressure was 550and 1200 bar at injection speed of 35 and 40mm/s for injections with PP and PLA respectively.

2.2.6. Characterisation of Composites

2.2.6.1. Density Measurement

Density of manufactured composites was measured in room temperature according to EN ISO 1183-1[

26] on high accuracy balance, Mettler Toledo EL204IC. Samples were immersed in ethanol of density determined before each series of measurements on the very same balance. Each weighing was repeated three times and averaged.

2.2.6.2. Brightness Measurement

The injection molded samples were scanned using a standard a spectrophotometer -spectro-guide 45/0 gloss S BYK-Gardner. The measuring device is placed on the even sample surface and the L*, a* and b* values were immediately output on the display for further use. The degree of brightness was taken by subtraction from the references (PP and PLA). Three samples were taken for averaging values for each biocomposite material.

2.2.6.3. Tensile Strength and Young Modulus

Static mechanical properties of manufactured test specimens were measured in tensile strength and young’s modulus to DIN EN ISO 527-1[

27] The tests were carried out on Zwick Roell Z020 universal testing machine. The testing speed for all measurements was 5mm/min and it was 1mm/min for young’s modulus. The reported values represent the averaged results of measurements performed on 10 samples for each type of composite material.

2.2.6.4. Impact Strength, IS

The impact strength was tested in accordance to DIN EN ISO 179-1[

28] on Wick/Roell HIT 25P apparatus. All composites were tested at ambient temperature of 23°C and 50% relative humidity. The values presented comprise averaged results for 10 tests for each type of composite.

2.2.6.5. Heat Deflection Temperature, HDT

Heat deflection temperature (HDT) analysis was conducted according to ISO 75-1[

29]. The bending specimens were analysed with 1.8MPa bending force and heating rate 2 °K/min. HDT was measured when specimen deflected for 0.34

2.2.6.6. Differential Scanning Calorimeter, DSC

The melting temperature of the composites and the neat matrix were investigated using 204 F1 Phoenix – Netszch Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) which is attached with a cooling system under a nitrogen atmosphere. DSC analyses were conducted from 40 to 250 ºC with a heating rate of 10 ºC/min (DIN EN ISO 11357 – 1) [

30]. The specimens were sealed in aluminum pans by pressing and the prepared samples were placed in the furnace of DSC with an empty reference pan. The heat flow rate as function of temperature was recorded automatically. The melting temperature was identified as the peak point of the DSC curves.

2.2.6.7. Melt Flow Rate (MFR) and Melt Volume Rate (MVR)

MFR and MVR tests are crucial for assessing the processability, performance, and consistency of biocomposites made from Polypropylene (PP), Polylactic Acid (PLA), and natural fibers. The tests were performed on Aflow, ZwickRoell extrusion plastometers which follows ISO 1133-1:2011 for PP-based biocomposites and ISO 1133-2:2011 for PLA-based biocomposites. The results of MRF and MVR were recoded as g/10min. and cm3/10min. respectively.

2.2.6.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy, SEM

SEM micrographs of the fractured specimens were taken in order to evaluate the quality of the fiber–matrix interface. The sample fracture surfaces for this investigation were gold coated using sputter coater, S150B, Edwards to prepare the specimens. A scanning electron microscope EVO 60 of ZEISS, with an emission field gun with acceleration voltage of 7 kV was used.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fiber Shaping

The results of the fiber shape analysis are shown in

Table 1. It reveals that kenaf, bagasse and soft wood are in the same range of 1 mm (mean value). They also showed an equal form of the length and thickness distribution (small size distribution), While Hemp exhibited the smallest length and thickness.

Regarding the aspect ratio, the Kenaf showed the highest value and provides therefore also the highest available surface area. Thus, it is expected to be very reactive compared to others [

31,

32]

A clear peak was observed to for the Kenaf and softwood. It indicates that they have similar fiber size distribution [

33]. The Bagasse has no clear peak; the distribution of length and thickness start from 40 µm (minimum). It had therefore a big size distribution.

Figure 1 compared the fibers length, thickness and aspect ratio for the four types of fibers used, the softwood had the highest length and thickness fibers, followed by Kenaf with regard to the fibers length and bagasse with regard to the fibers thickness. The aspect ratio (length-to-thickness ratio) is a critical factor that influences the mechanical and physical properties of fibers in bio-based composites. Kenaf has the highest aspect ratio, which is typically associated with improved mechanical properties, such as tensile strength, since longer fibers distribute stress more effectively in composites. Therefore, it is expected to exhibit the best mechanical performance. The aspect ratios of Bagasse and softwood are comparable (

Table 1), suggesting they may have similar mechanical properties. The Hemp, with the lowest aspect ratio, was not expected to perform as well mechanically.

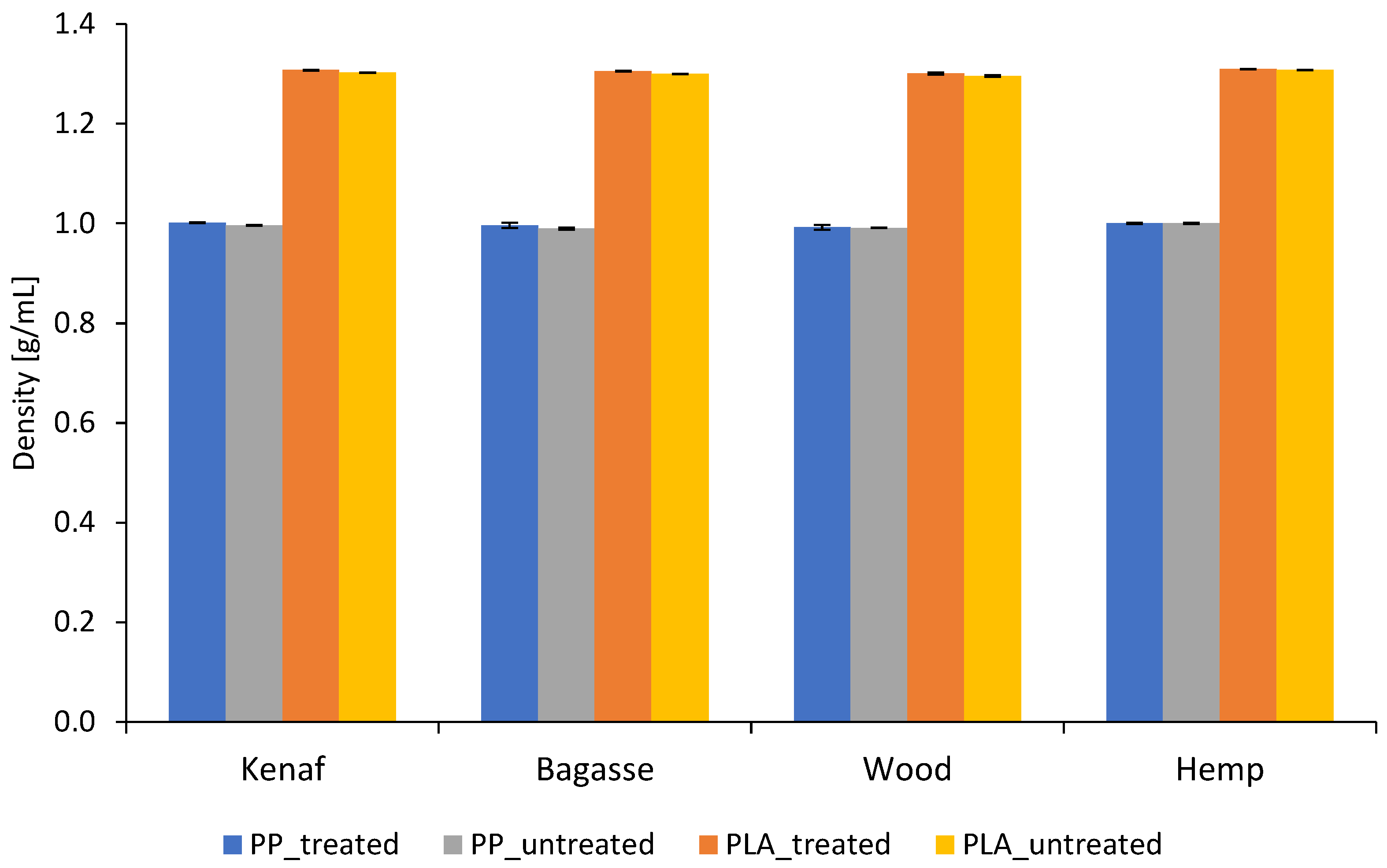

3.2. Density of the Composites

All manufactured biocomposites reinforced with the fibers have shown density values in nearly the same range of 0.996–1.001 g/cm3

Figure 1 for the composites produced using PP. As for those produced by PLA they exhibited densities ranged from 1.3 to 1.29 g/cm3 as shown in

Figure 2. The density of polypropylene reinforced with glass fibers (PP–GF) typically falls within the range of 1.03 to 1.22 g/cm³ when considering standard fiber concentrations of 20 to 40 weight percent (wt%). One can observed that these densities are in the range of obtained densities when 20% of PP and glass fiber composites [

34].

Low density of polymer composites filled with natural fibers was received due to a specific hollow structure of the fibers which is totally different from a bulky structure of glass fibers [

35,

36]. It is worth noting that the lower density of PP biocomposites compared to PLA is mainly due to the lower intrinsic density and simpler molecular structure of PP that may not fully compensate for the added weight of the fibers, whereas the inherently denser PLA matrix contributes more to the overall weight of the composite. This density difference directly affects the mechanical and physical properties of the biocomposites, influencing factors like stiffness, thermal properties, and strength-to-weight ratio.

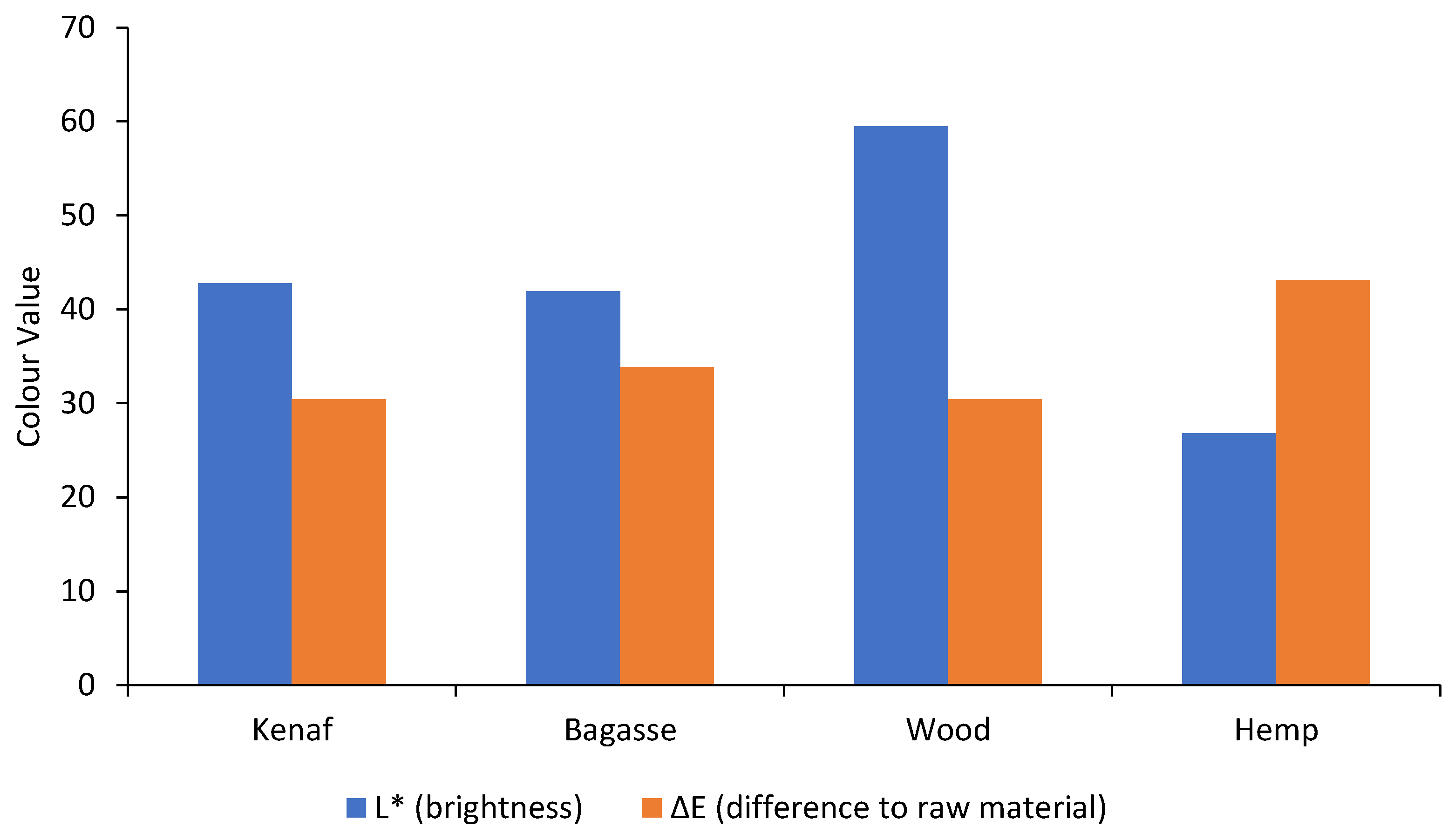

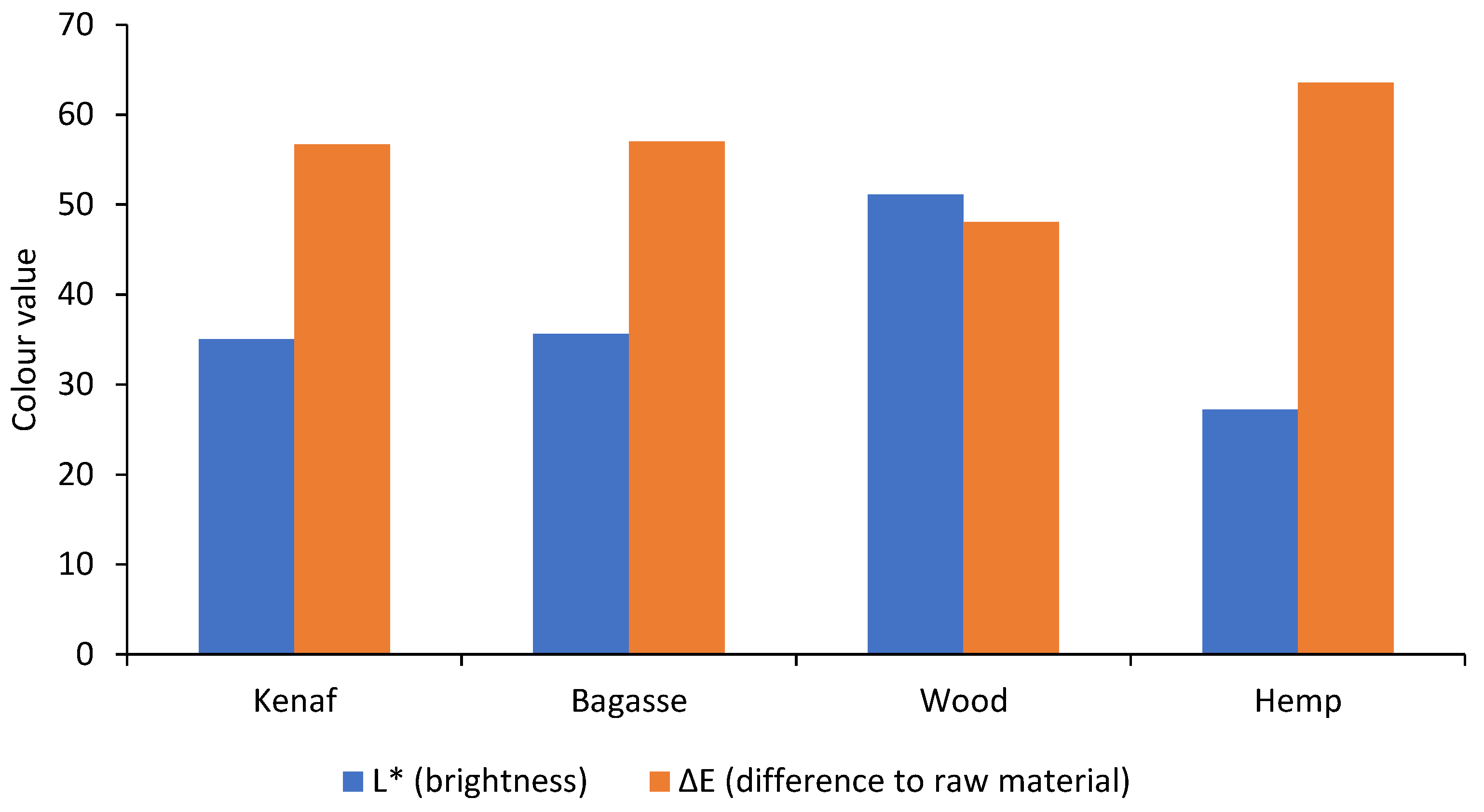

3.3. Brightness Measurement

The results in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 present the brightness and ∆E for both PP and PLA composites with neat PP and PLA as references. The results indicated that the wood+ PP composites obtained the highest brightness (L*), While the hemp was the darkest one. The PLA composites followed the same trend as the PP composites.

The NaOH treatment of the wood removed a high amount of lignin and as a result, the produced composites obtained higher L* values than the untreated composites. As the color of natural fibers reverts to the lignin [

37], therefore, the wood fibers and the natural fibers have different lignin structures and content [

38,

39,

40]. Hemp has a relatively high lignin content compared to fibers like Kenaf and Bagasse, and lignin tends to darken under heat. This makes hemp-based composites appear darker. Even though the untreated fibers may not be dark, lignin degradation in the presence of heat can make hemp composites appear noticeably darker than those with Kenaf and Bagasse. Additionally, the thermal decomposition under processing condition contributes to color changes due to chromophores [

41] formed from conjugated lignin structures. These factors collectively contribute to the darkening of biocomposites, with hemp composites often appearing the darkest among the three due to its lignin content and thermal sensitivity.

3.4. Mechanical Properties

3.4.1. Tensile Strength and Young’s Modulus

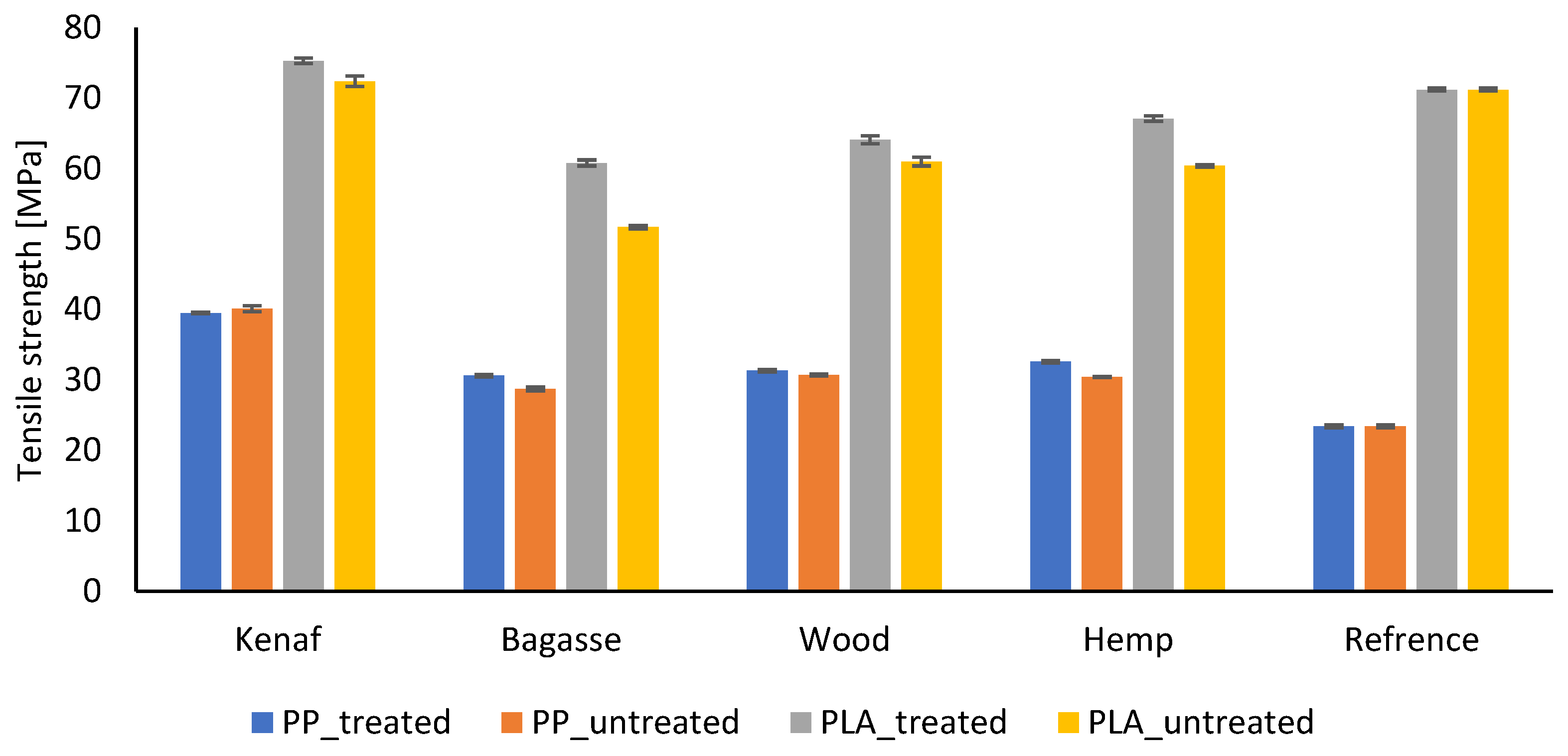

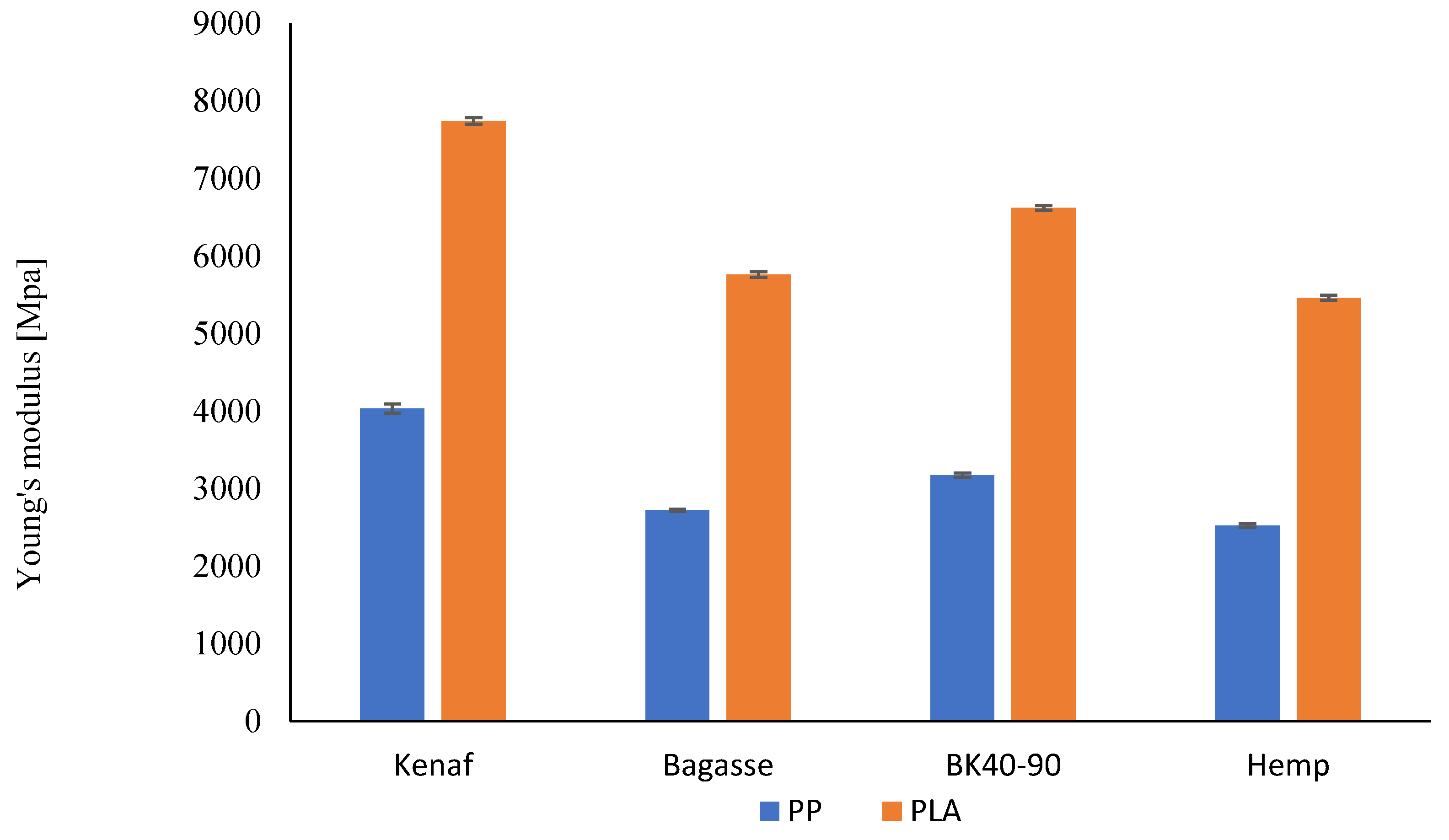

Experimental results of tensile strength and Young’s modulus for the PP and the PLA-based composites are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 respectively. Results show that incorporation of natural fiber mats has improved the tensile properties of neat PP for each type of composites. The tensile strength of neat PP was recorded as 23.4 MPa. From the results, it can be observed that Kenaf fiber reinforced composites showed higher tensile strength (40.1MPa) for both type of matrices as compared to other type of fiber reinforcement. PP/softwood, PP Bagasse and PP/hemp composites showed an increased tensile strength of 30.1, 28.7 and 28.2 MPa, respectively, which are higher than the tensile strength of neat PP(23.4 MPa). Pure PP and pure PLA showed a Young’s modulus

of 23.4 and 71.2 MPa, respectively. A slight increase in the Young’s modulus of all types of PLA based composites was observed, whereas PP-based composites showed a relatively higher increase. Although the PLA is more polar than PP, however, the addition of coupling agents (maleic anhydride-grafted PP) and influence of alkali treatment led to significant improve in the fiber-matrix adhesion in the case of PP. It also resulted in better load transfer and a notable increase in tensile strength. The smaller increase in tensile strength when adding fibers to PLA compared to PP is due to the intrinsic mechanical properties of PLA, such as its brittleness and lower ductility, as well as differences in fiber-matrix adhesion and stress transfer efficiency. Hence, the alkali treatment might work effectively with PP compared to PLA [

42,

43]

3.4.2. Impact Strength

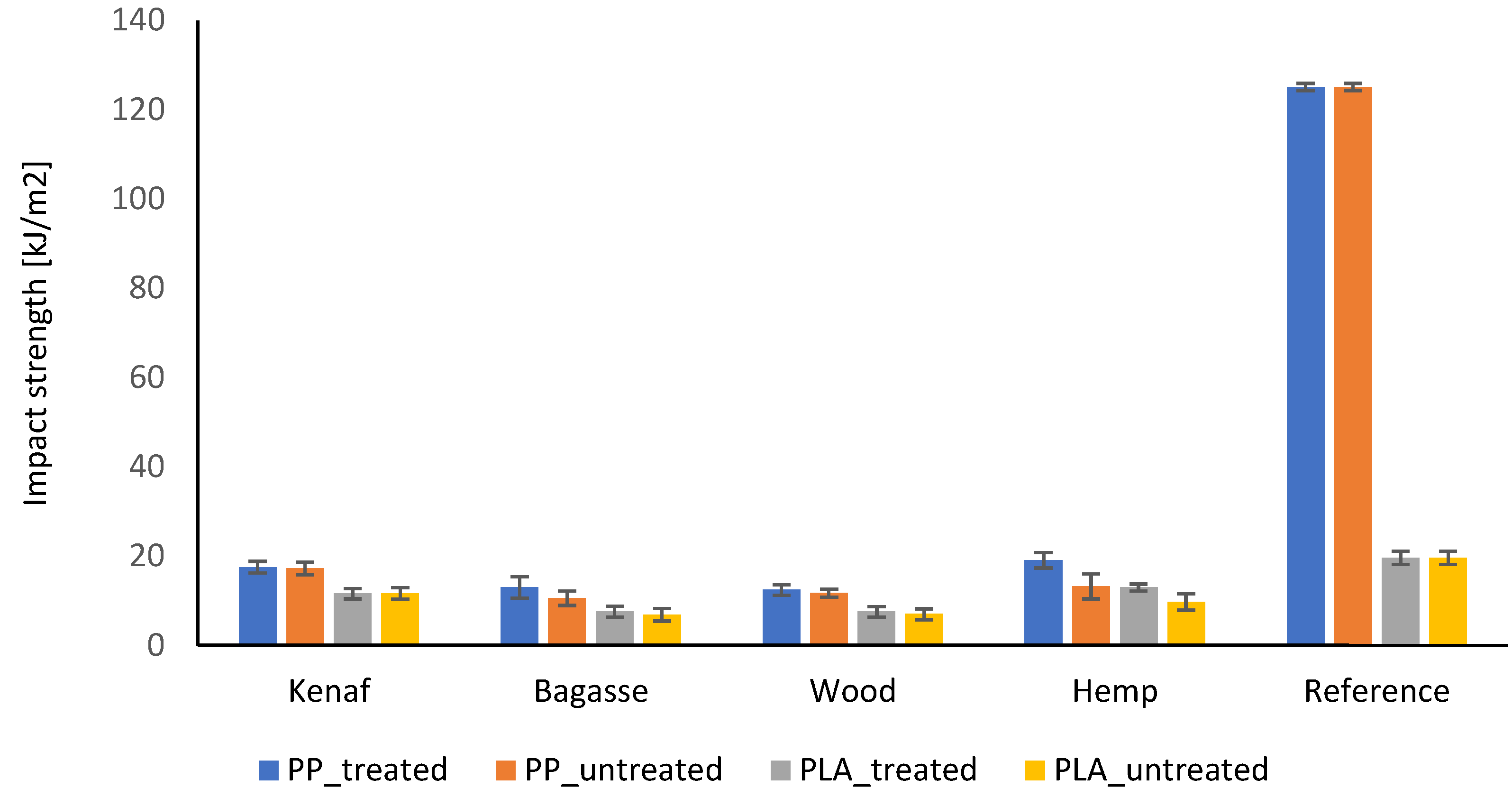

The Alkaline treatment of natural fibers could improve their composite's mechanical properties depending on some factors such as concentration of the NaOH and socking time [

44] and intrinsic properties of the fibers as well as the polymer metrics. The impact strength of the composites with treated and untreated fibers (

Figure 6) showed close results in the most produced composites except those results obtained with the hemp fiber as filler. The hemp composites showed a clear improvement between the alkaline-treated composites and the untreated fibers achieving the highest impact strength value. This result could revert to fact that the additional grinding of the Hemp fibers as it was agglomerated after the alkaline treatment had improved hemp fibers’ aspect ratio as shown in in

Figure 6, from 6,67 to 8,97 [

45,

46]. This means that the Hemp fibers became more thinner and shorter which lead to their well distribution resulted in improved impact strength compared with the other fibers [

47]. Furthermore, the alkaline treatment improves the bonding and surface roughness of hemp fibers as shown in

Figure 7, allowing them to absorb more energy upon impact, even with a lower aspect ratio compared to the kenaf. Moreover, hemp fibers have higher toughness compared to other fibers, like kenaf or wood. Toughness, is a key factor in impact strength. The alkaline treatment tends to improve the toughness of hemp fibers more effectively because it optimizes the cellulose structure without significantly degrading the fiber [

9,

48,

49,

50,

51].

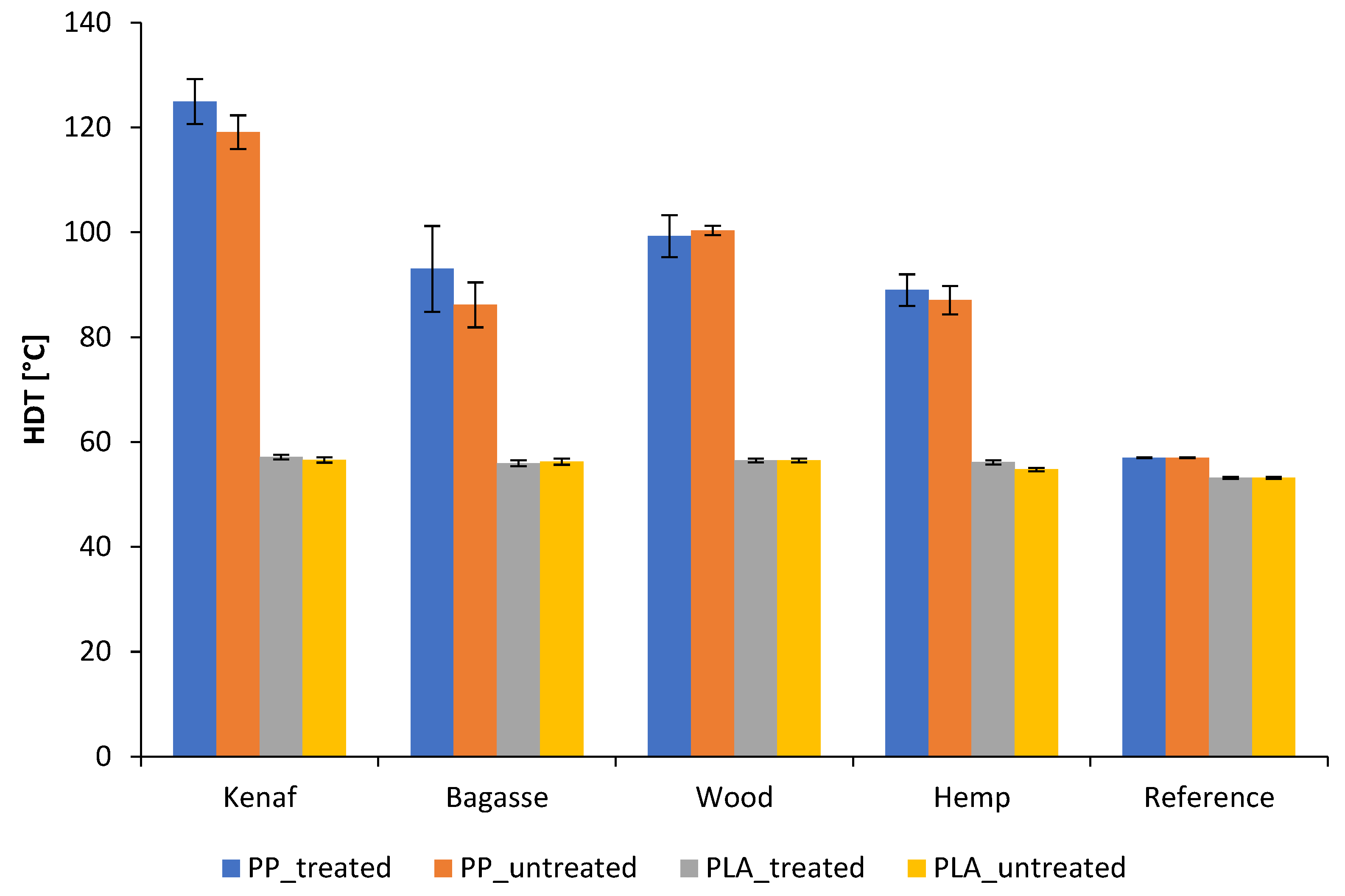

3.5. Heat Deflection Temperature

The interaction between the composite components affects the HDT of natural fiber plastic biocomposites. The addition of natural fiber to the thermoplastic polymers improves their HDT performance [

52,

53] as shown in

Figure 7. We can generally notice that the PLA natural fibers composites have lower HDT values than the PP composites, and this is considered one of the PLA weaknesses that affect its application specifically in the high-temperature environment [

52,

54]. On the other hand, the treated fibers with NaOH recorded slightly higher HDT values than untreated in the PP composites. While in the PLA composites, there is no clear difference between the treated and untreated composites. Among all the prepared composites the composites made with PP and treated kenaf fibers recorded the highest HDT value with above120 C. This difference may attributed to some factors such as the inherent stability of treated Kenaf (due to to its high stiffness and rigidity) fibers contributes to improved thermal resistance, raising the HDT of the composite. Other factors could be alkali treatment of Kenaf fibers typically removes surface impurities like lignin, wax, and oils, which improves the fiber-matrix adhesion by creating a rougher fiber surface. This stronger bonding allows more efficient stress transfer between the fibers and the PP matrix under heat, maintaining structural integrity and resulting in higher HDT [

42]. Furthermore, PP has higher compatibility with treated Kenaf fibers compared to more hydrophilic fibers like hemp, which may have higher moisture absorption and, consequently, lower thermal stability [

43]. The hydrophobic nature of the PP matrix complements the treated Kenaf fibers, providing better thermal performance overall [

42].

3.6. Differential Scanning Calorimeter(DSC)

The data presented in

Table 2 illustrate the Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) results for polypropylene (PP) composites reinforced with different natural fibers, including kenaf, bagasse, and hemp. The table also highlights the impact of NaOH treatment on these natural fibers. A noticeable trend across all fibers is the slight increase in melting temperature after the NaOH treatment, which suggests enhanced fiber-matrix interactions. This improvement is likely due to the treatment strengthening the bond at the fiber-polymer interface, thus stabilizing the polymer during melting. Among the fibers studied, bagasse shows the most significant improvement, followed by kenaf and hemp. These findings agreed with [

55,

56] who reported that the alkaline treatment of the fibers leads to a fiber-matrix interface which also improves the thermal stability of the produced composites. It worth noting that the thick, lignin-rich cell walls of bagasse make it particularly resilient to thermal degradation. Research has shown that lignin-rich, thick-walled fibers, such as those from bagasse, can improve the thermal stability of composites by acting as effective barriers to heat flow within the polymer matrix.

On the other hand, the DSC results of the different fibers reinforced PLA composites (

Table 3) indicates the changes in melting temperature after NaOH treatment reporting that the effectiveness of fiber alkaline treatment depends on the type of fiber. Bagasse and softwood, being the thicker fibers were less flexible, which can limit movement within the polymer matrix and provide enhanced structural stability at elevated temperatures. This means that with a more increase in melting temperature, demonstrate that fibers morphology can play significant role in addition to the alkaline treatment in terms of improving thermal stability in the produced composites. However, the minimal changes for kenaf and hemp indicate that their thinner fibers together with the alkaline treatment might not substantially alter their thermal properties.

3.7. Melt Flow Rate (MFR), and Melt Volume Rate (MVR)

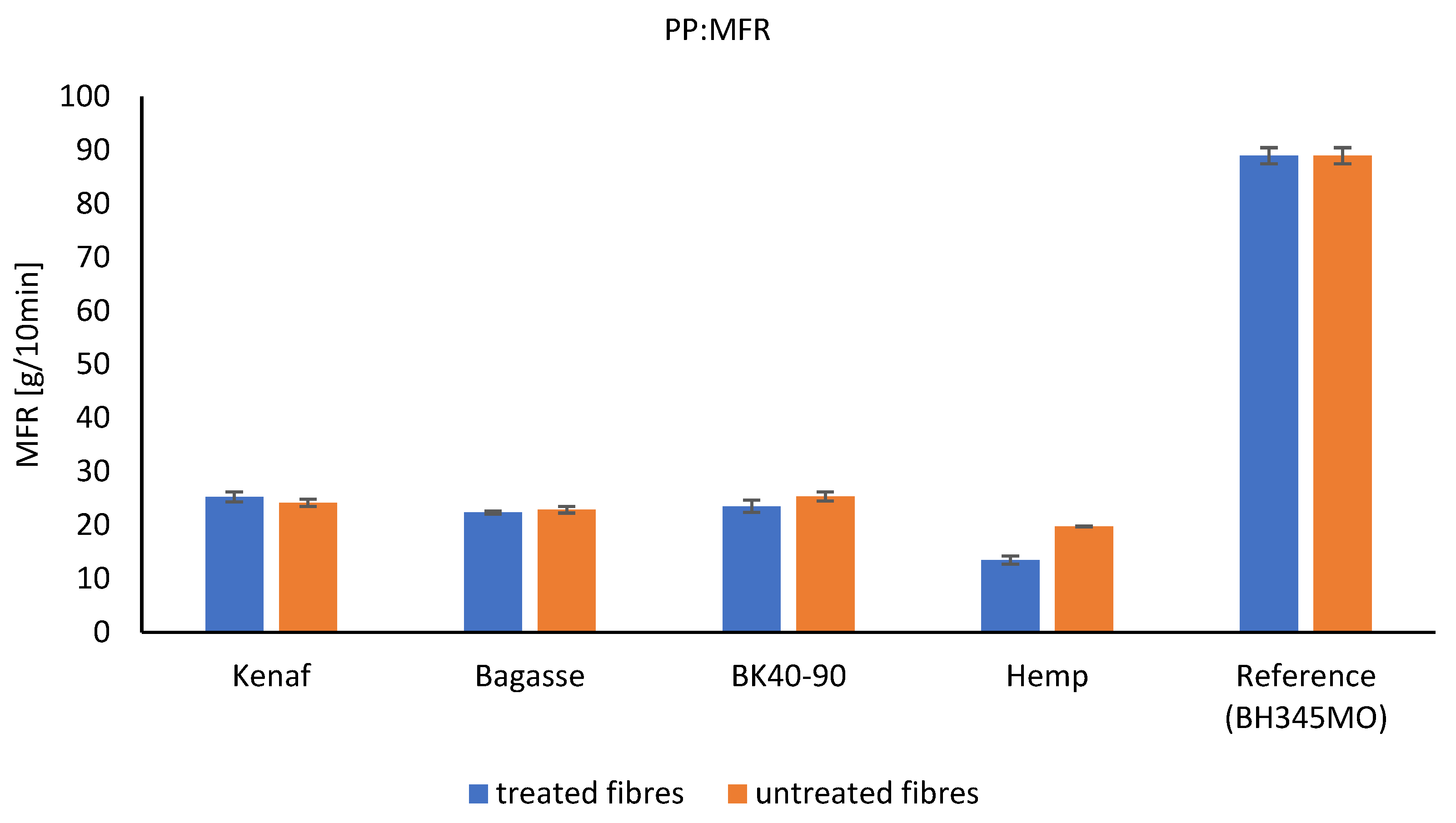

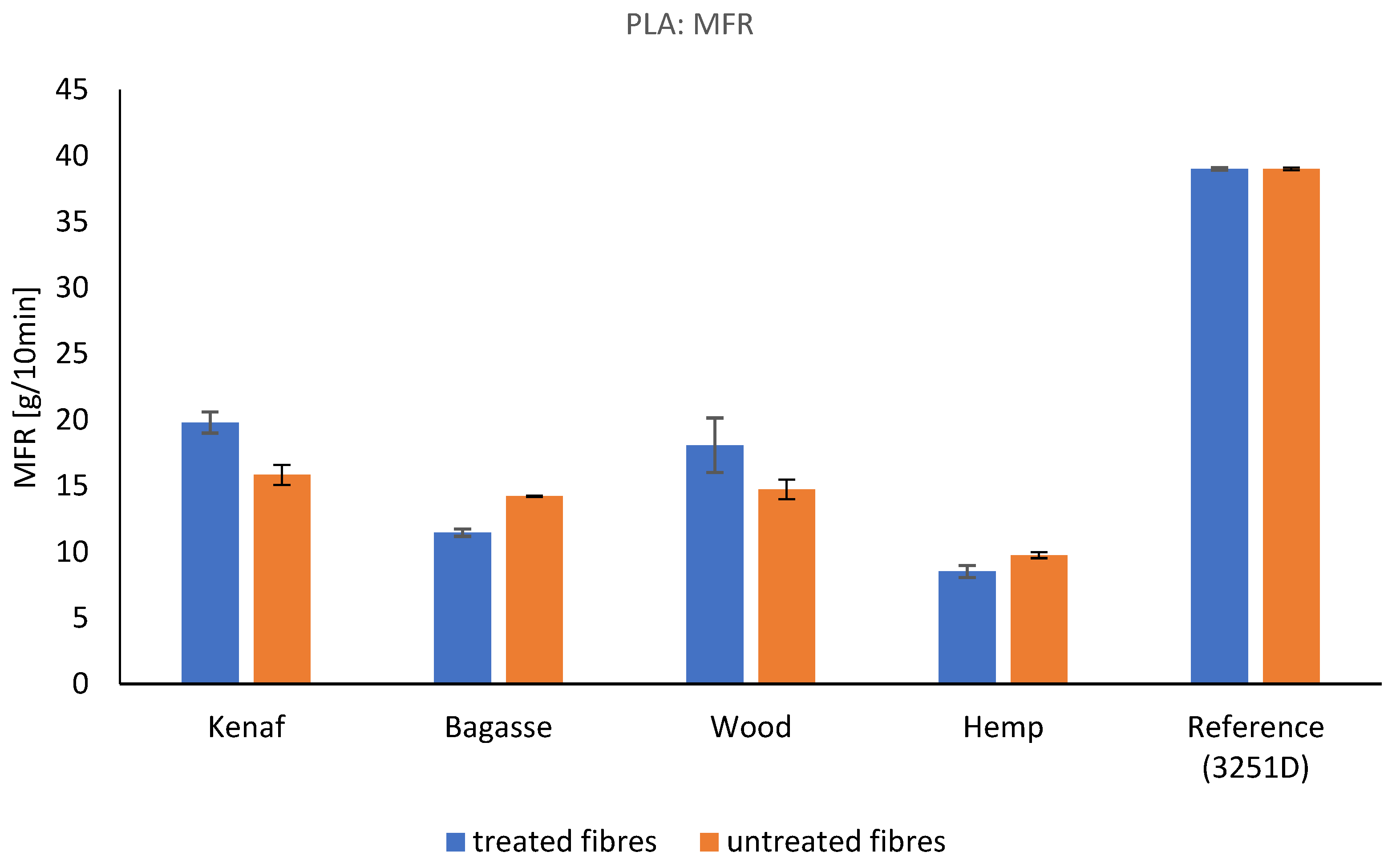

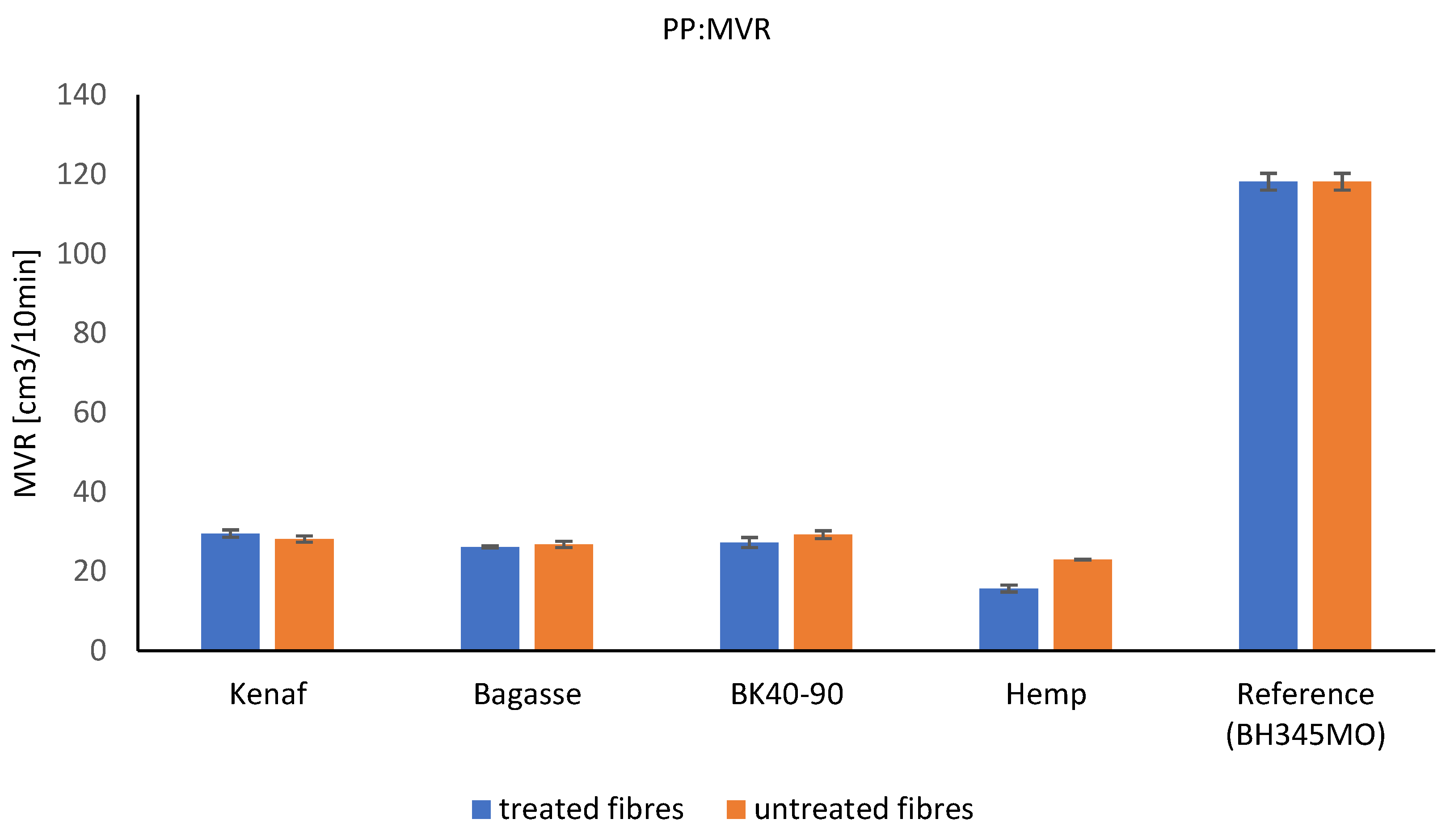

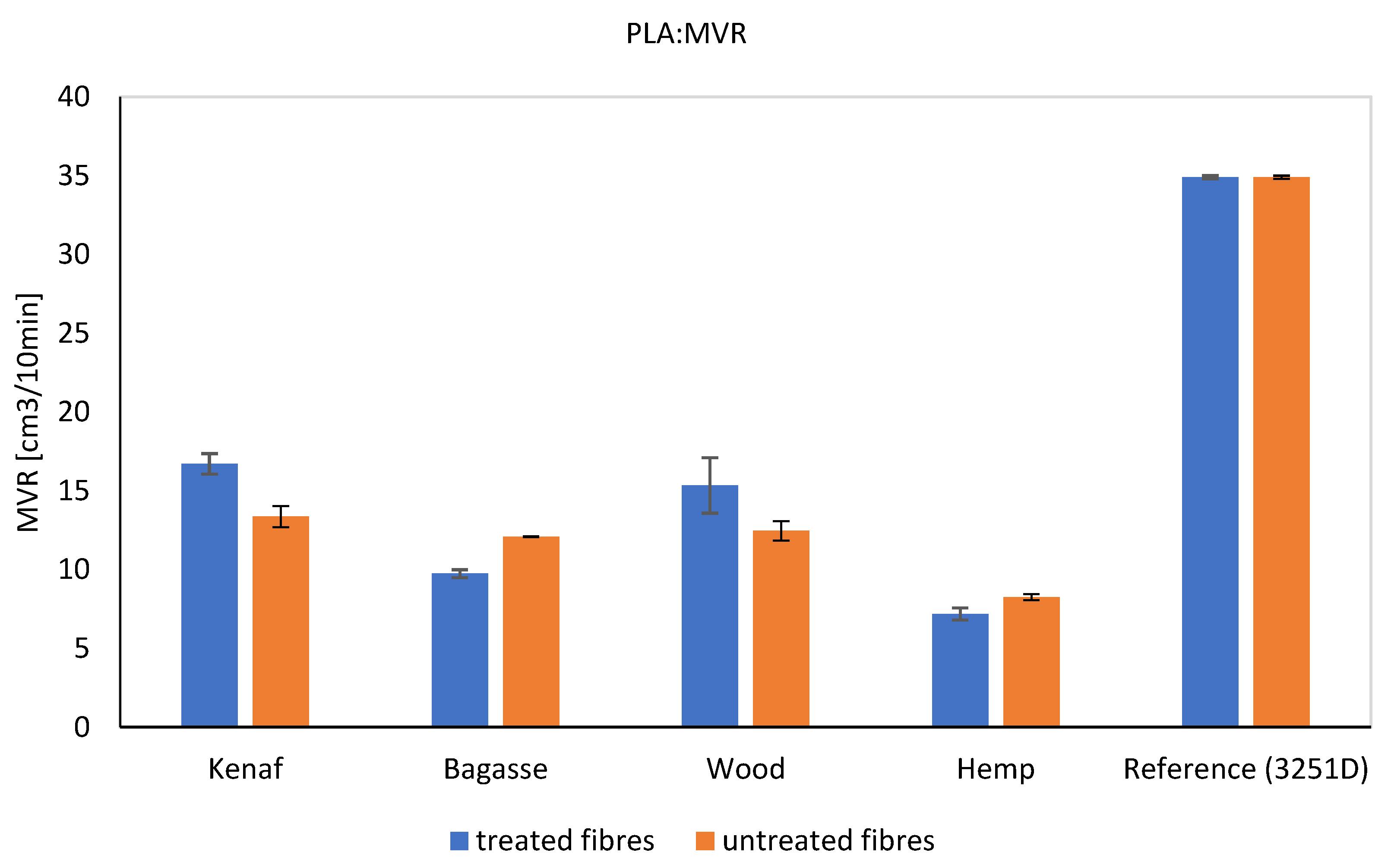

The MFR results for PP and PLA composites are presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. It shows a decrease in MFR values when adding fibers. This is understandable as due to the presence of fibers in melts and their partial misalignment [

57], which significantly affects the dynamics of visco-elasticity of the melts [

58], hindering the mobility of molecular chains. Furthermore, it can be seen that different fibers have different MFR values. Kenaf and softwood are having comparable values due to the similarities in their fibers distribution and length.

The MFR and MVR graphs for PP composites reinforced with treated and untreated kenaf, bagasse, softwood, and hemp fibers show that the MFR of kenaf fibers treated with 5% NaOH is higher than that of the untreated kenaf in the PP matrix. However, for softwood, bagasse, and hemp, the MFR values for untreated fibers are slightly higher than those of the treated fibers.

The observed differences in the MFR and MVR of NaOH-treated versus untreated fibers in polypropylene (PP) composites can be attributed to the changes in fiber structure and interface characteristics after treatment. Alkaline treatment with NaOH is known to modify the surface of natural fibers by removing lignin, hemicellulose, and other impurities, which can improve fiber-matrix adhesion in PP composites. This enhanced adhesion often leads to a more effective stress transfer and reduced fiber sliding, resulting in a higher MFR compared to untreated fibers, particularly for fibers like kenaf. This suggests that kenaf fibers, after NaOH treatment, have a better interfacial bonding with the PP matrix, which contributes to improved flow properties under the testing conditions.

However, for fibers like softwood, bagasse, and hemp, untreated fibers may sometimes show a slightly higher MFR. This can happen if the NaOH treatment reduces fiber flexibility or if certain structural components, such as lignin, which were partially retained in untreated fibers, improve processability without necessarily increasing matrix bonding as much as in the case of kenaf.

Such observations align with findings in polymer composites, where factors like fiber structure, treatment method, and fiber type play critical roles in MFR variation. This has been noted in studies on fiber-reinforced composites, including those incorporating lignocellulosic fibers like sisal and corncob in PP matrices, which showed treatment-induced changes in rheology and interface characteristics that could impact MFR depending on fiber type and treatment intensity [

59,

60]

Figure 8.

the Melt flow rate (MFR) treated and untreated of kenaf, Bagasse, hemp and softwood with PP.

Figure 8.

the Melt flow rate (MFR) treated and untreated of kenaf, Bagasse, hemp and softwood with PP.

Figure 9.

The Melt Volume Rate (MFR) treated and untreated of kenaf, Bagasse, hemp, and softwood with PLA.

Figure 9.

The Melt Volume Rate (MFR) treated and untreated of kenaf, Bagasse, hemp, and softwood with PLA.

Figure 10.

The Melt Volume Rate (MVR) treated and untreated of kenaf, Bagasse, hemp, and softwood against PP.

Figure 10.

The Melt Volume Rate (MVR) treated and untreated of kenaf, Bagasse, hemp, and softwood against PP.

Figure 11.

The Melt Volume Rate (MVR) treated and untreated of kenaf, Bagasse, hemp, and softwood with PLA

Figure 11.

The Melt Volume Rate (MVR) treated and untreated of kenaf, Bagasse, hemp, and softwood with PLA

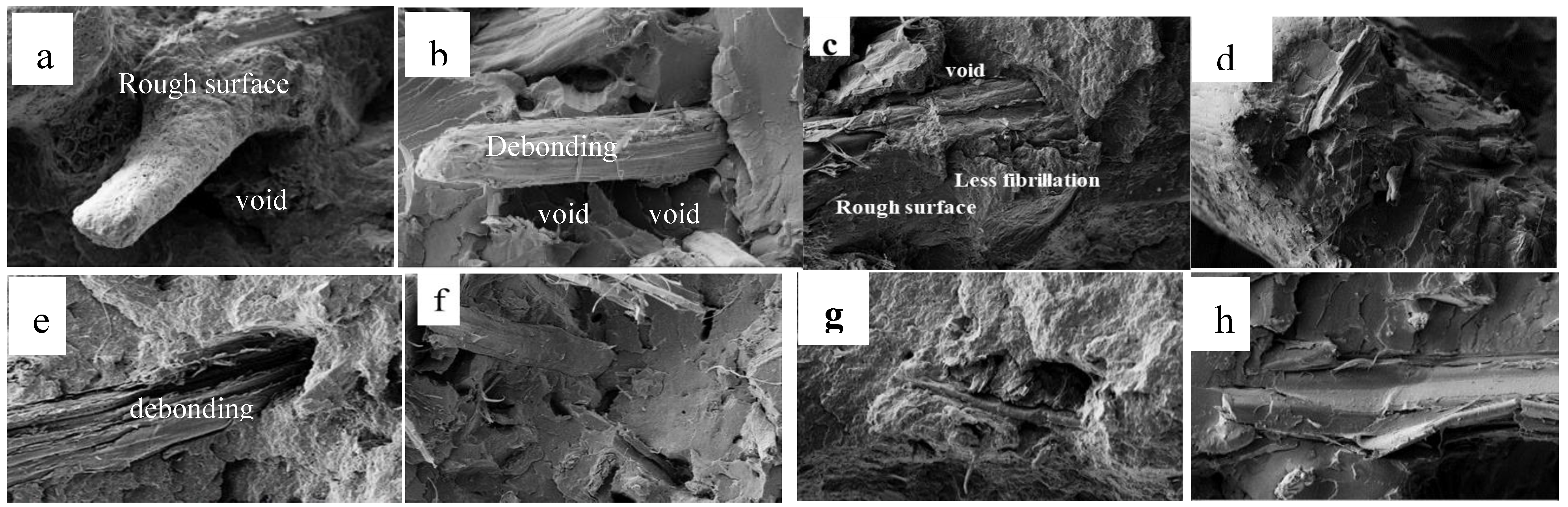

3.8. Morphological Analysis

Morphological analysis of treated polypropylene (PP) and polylactic acid (PLA) biocomposites was conducted to evaluate fiber dispersion, fiber/matrix adhesion, and interfacial properties. SEM micrographs highlighted differences based on fiber type, polymer matrix, and treatment(

Figure 12). The images of kenaf fibers embedded in PP (a) and PLA (b) reveal that NaOH treatment roughened the surface of the kenaf fibers by removing impurities, which improved mechanical interlocking with the PP matrix. This led to tighter bonding and fewer visible gaps, enhancing interfacial adhesion. In contrast, the image of PLA (b) composites showed weaker adhesion, as fibers appeared completely detached with residual PLA adhering to their surfaces. Voids were more prominent compared to the PP composite, indicating areas of debonding. The incompatibility, presence of large voids, and phase separation between the fibers and PLA matrix were attributed to the hydrophilic nature of kenaf fibers, which induced interfacial debonding with the hydrophobic PLA matrix. Similar results were observed by Moustafa et al. when using untreated kenaf fibers with polystyrene polymer [

61]. The results indicated that the treatment of kenaf fibers with NaOH does not significantly improve adhesion with the PLA matrix, likely due to the intrinsic incompatibility between the hydrophilic kenaf fibers and the hydrophobic PLA polymer. This suggests that additional strategies, such as using coupling agents or compatibilizers, might be necessary to promote better interfacial bonding with PLA [

62].

For bagasse fibers, the SEM image of the PP composite (c) showed that the fibers exhibit a distinct texture compared to kenaf, presenting a more compact structure with less fibrillation. Bagasse fibers tend to maintain a more intact surface, unlike the roughened, fibrillated surface observed in treated kenaf fibers. These morphological differences influence their bonding with the polymer matrix, as reflected in the variation in mechanical properties. Consequently, kenaf demonstrated superior performance compared to bagasse. The micrographs of bagasse and PLA biocomposites (image d) revealed significant voids, gaps, and fiber pull-out compared to image (c), indicating poor interfacial adhesion and, consequently, subpar mechanical properties. Despite this, bagasse fibers have been shown to significantly enhance the stiffness of PLA even without the use of a coupling agent [

63]. Similar studies suggested that adding a compatibilizer or hybrid materials such as nanosilica may improve adhesion [

64].

The micrographs of hemp PP (e) and hemp PLA (f) composites revealed additional differences. Treated hemp PP composites exhibit good bonding between fibers and the matrix, with fewer gaps observed. The treatment resulted in smoother fiber surfaces and increased the aspect ratio of the fibers by reducing their thickness. This thinning, however, led to a decrease in the tensile strength of individual hemp fibers, ultimately resulting in lower mechanical properties for the hemp fiber composites [

65]. In the case of PLA composites, significant fiber-matrix gaps indicate poor adhesion. Despite the NaOH treatment, rough fiber surfaces are still visible. Partially detached fibers and their imprints in the matrix are also noticeable, further suggesting weak interfacial bonding.

For softwood-based composites, the PP composite (g) showed pronounced surface roughness, with PP covering most of the fibers compared to image (h). However, some gaps and uncovered fibers remain visible. Regarding PLA composites, the extent of fiber pull-out is notably larger compared to PP composites, further underscoring the differences in interfacial adhesion between the two matrices. Moreover, the softwood-based PP and PLA biocomposites exhibited fibrous particles evenly dispersed within the PP and PLA matrices, with a minimal number of voids compared to the three other fibers. The fracture surfaces appeared uniform, indicating good adhesion. This may be attributed to the structure of wood particles, which lack lumens, unlike bast, stem, and leaf fibers [

17]. It is worth noting that the micrograph of the softwood-PP biocomposite closely resembles that of the bagasse-PP biocomposite, indicating a similarity in their mechanical properties.

The differences between PP and PLA matrices were evident. PP, being a non-polar polymer, interacts weakly with natural fibers (which are polar). However, coupling agents such as maleic anhydride-grafted PP significantly improved fiber-matrix adhesion, leading to better load transfer and a notable increase in tensile strength. In contrast, PLA, a polar polymer, should theoretically exhibit better adhesion with polar natural fibers. However, PLA's brittleness, rigidity, and crystalline structure limit its ability to distribute stress effectively, resulting in a smaller increase in tensile strength even with good bonding. Furthermore, the fracture behavior of the three different fiber types varied, influenced by their distinct mechanical properties and geometries, which affected stress distribution within the matrix.

4. Conclusions

The mechanical performance of biocomposites is significantly influenced by the aspect ratio of the reinforcing fibers. Among the fibers tested, Kenaf exhibited the highest aspect ratio and consequently the best mechanical properties, followed closely by softwood and Bagasse, which showed comparable performance. Initially, hemp fibers had the lowest aspect ratio and displayed weaker mechanical strength; however, following alkaline treatment and grinding, their aspect ratio increased to 8.97, surpassing that of Bagasse and softwood, resulting in improved impact strength.

These biocomposites also demonstrated lower density compared to those made from synthetic fibers, providing a lightweight alternative suitable for applications where weight reduction is critical without sacrificing mechanical performance. Additionally, the chemical composition of the fibers and the effects of alkaline treatment influenced the color of the biocomposites, with hemp displaying the darkest shade, thereby offering aesthetic versatility for eco-friendly designs.

In terms of tensile strength, the addition of fibers to PLA resulted in a smaller increase compared to PP, attributed to PLA's inherent brittleness, lower ductility, and weaker fiber-matrix adhesion. As such, alkali treatment may prove more effective in enhancing fiber reinforcement within PP composites.

Thermal stability varied among the fibers; Kenaf fibers exhibited the highest heat distortion temperature (HDT), while Bagasse had a high melting temperature due to its thick cell wall. Notably, PP-based biocomposites outperformed PLA counterparts in thermal performance.

The introduction of fibers also reduced the melt flow rate (MRF) and melt volume rate (MVR) in both PP and PLA, as the fibers influenced the viscoelastic dynamics of the melts by hindering the mobility of molecular chains. Ultimately, the differing behaviors of the fibers and the polymer matrices stem from both the fibers composition, morphology, their response to the chemical treatment and the intrinsic properties of the polymers used.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zeinab Osman; Formal analysis, Mohammed Elamin and Bertrand Charrier; Funding acquisition, Zeinab Osman, Elhem Ghorbel and Bertrand Charrier; Methodology, Zeinab Osman and Mohammed Elamin; Resources, Elhem Ghorbel and Bertrand Charrier; Writing – original draft, Zeinab Osman; Writing – review & editing, Mohammed Elamin, Elhem Ghorbel and Bertrand Charrier.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the fund provided by NAPATA program, jointly funded by France campus and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific research, Sudan. Lab facilities provided by IUT/IPREM, University of Pau, L2MGC, CY Cergy Paris Université and the Institute of engineering research, Sudan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the technical, financial and administrative support provided by IPREM, Pau University and L2MGC, CY Cergy Paris Université. Zeinab O.sman wants to acknowledge the PAUSE program of Collège de France for funding a research visit to France.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, Y.; Mai, Y.-W. Interfacial characteristics of sisal fiber and polymeric matrices. J Adhes 2006, 82, 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M.; Drzal, L.T. Sustainable bio-composites from renewable resources: Opportunities and challenges in the green materials world. J Polym Environ 2002, 10, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, R.M.; Sanadi, A.; Jacobson, R.; Caulfield, D. Properties of kenaf/polypropylene composites. Kenaf Prop Process Prod 1999, 1, 381–392. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Wu, Q.; Yao, F.; Xu, Y. Preparation and properties of recycled HDPE/natural fiber composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2007, 38, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, T.; Cramer, S.M.; Falk, R.H.; Felton, C. Accelerated weathering of natural fiber-filled polyethylene composites. J Mater Civ Eng 2004, 16, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulk, J.A.; Chao, W.Y.; Akin, D.E.; Dodd, R.B.; Layton, P.A. Enzyme-retted flax fiber and recycled polyethylene composites. J Polym Environ 2004, 12, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, B.C.; Basak, R.K.; Sarkar, M. Studies on jute-reinforced composites, its limitations, and some solutions through chemical modifications of fibers. J Appl Polym Sci 1998, 67, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgriccia, N.; Hawley, M.C.; Misra, M. Characterization of natural fiber surfaces and natural fiber composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2008, 39, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, K.; Thomas, S.; Pavithran, C. Effect of chemical treatment on the tensile properties of short sisal fibre-reinforced polyethylene composites. Polymer (Guildf) 1996, 37, 5139–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Sun, X.; Sun, R. Chemical, structural, and thermal characterizations of alkali-soluble lignins and hemicelluloses, and cellulose from maize stems, rye straw, and rice straw. Polym Degrad Stab 2001, 74, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suizu, N.; Uno, T.; Goda, K.; Ohgi, J. Tensile and impact properties of fully green composites reinforced with mercerized ramie fibers. J Mater Sci 2009, 44, 2477–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Matsuo, T.; Goda, K.; Ohgi, J. Development and effect of alkali treatment on tensile properties of curaua fiber green composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2007, 38, 1811–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Deopura, B.L.; Alagiruswamy, R. Interface Behavior in Polypropylene Composites. J Thermoplast Compos Mater 2003. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.V.; Joseph, K.; Thomas, S. Effect of processing variables on the mechanical properties of sisal-fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites. Compos Sci Technol 1999, 59, 1625–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R.P.; Tekale, S.U.; Shisodia, S.U.; Totre, J.T.; Domb, A.J. Biomedical applications of poly (lactic acid). Rec Pat Regen Med 2014, 4, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J. Biodegradable poly (lactic acid): Synthesis, modification, processing and applications. Springer Science & Business Media; 2011.

- Bledzki, A.K.; Franciszczak, P.; Osman, Z.; Elbadawi, M. Polypropylene biocomposites reinforced with softwood, abaca, jute, and kenaf fibers. Ind Crops Prod 2015, 70, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, W.N.; Amico, S.C.; Satyanarayana, K.G. Studies on the combined effect of injection temperature and fiber content on the properties of polypropylene-glass fiber composites. Compos Sci Technol 2005, 65, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, H.; Tanigawa, M.; Komoto, S.; Takahashi, M. Dispersed state of glass fibers and dynamic viscoelasticity of glass fiber filled polypropylene melts. Nihon Reoroji Gakkaishi 1997, 25, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.V.; Oommen, Z.; Joseph, K.; Thomas, S. Melt rheological behaviour of short sisal fibre reinforced polypropylene composites. J Thermoplast Compos Mater 2002, 15, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Sulong, A.B.; Radzi, M.K.F.; Ismail, N.F.; Raza, M.R.; Muhamad, N.; et al. Influence of alkaline treatment and fiber loading on the physical and mechanical properties of kenaf/polypropylene composites for variety of applications. Prog Nat Sci Mater Int 2016, 26, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaikambo, L.Y.; Ansell, M.P. Chemical modification of hemp, sisal, jute, and kapok fibers by alkalization. J Appl Polym Sci 2002, 84, 2222–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bam, S.A.; Gundu, D.T.; Onu, F.A. The effect of chemical treatments on the mechanical and physical properties of bagasse filler reinforced low density polyethylene composite. Am J Eng Res 2019, 8, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Shibata, S.; Fukumoto, I. Mechanical properties of biodegradable composites reinforced with bagasse fibre before and after alkali treatments. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2006, 37, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadiga, D.G.; Bhat, K.S.; Mahesha, G.T. Sugarcane bagasse fiber reinforced composites: Recent advances and applications. Cogent Eng 2020, 7, 1823159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 1183-1. Plastics-Methods for determining the density of non-cellular plastics - Part 1: Immersion method, liquid pyknometer method and titration method. 2019.

- ISO 527-1. Plastics – Determination of tensile properties – Part 1: General principles 2019, 13.

- ISO. 179-2 Plastics - Determination of Charpy impact properties - Part 2: Instrumented impact test. 2020.

- ISO. 75-1 Plastics — Determination of temperature of deflection under load — Part 1: General test method 2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77576.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- ISO. 11357-1 Plastics — Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) — Part 1: General principles 2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/83904.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Prakash, K.B.; Fageehi, Y.A.; Saminathan, R.; Manoj Kumar, P.; Saravanakumar, S.; Subbiah, R.; et al. Influence of Fiber Volume and Fiber Length on Thermal and Flexural Properties of a Hybrid Natural Polymer Composite Prepared with Banana Stem, Pineapple Leaf, and S-Glass. Adv Mater Sci Eng 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthi, N.; Kumaresan, K.; Sathish, S.; Gokulkumar, S.; Prabhu, L.; Vigneshkumar, N. An overview: Natural fiber reinforced hybrid composites, chemical treatments and application areas. Mater Today Proc 2019, 27, 2828–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulou, E.; Papatheohari, Y.; Christou, M.; Monti, A. Origin, Description, Importance, and Cultivation Area of Kenaf. Green Energy Technol 2013, 117, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhe, S.; de Barros, S.; Banea, M.D. Theoretical assessment of the elastic modulus of natural fiber-based intra-ply hybrid composites. J Brazilian Soc Mech Sci Eng 2019, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholampour, A.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. A review of natural fiber composites: Properties, modification and processing techniques, characterization, applications. vol. 55. Springer US; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Paul, S.A.; Pothan, L.A.; Deepa, B. Cellulose Fibers: Bio- and Nano-Polymer Composites. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.K. Application of natural dyes to cotton and jute textiles: Science and technology and environmental issues. Handb Renew Mater Color Finish 2018, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri, K.; Toubal, L.; Loranger, É.; Koffi, D. Influence of UV irradiation on mechanical properties and drop-weight impact performance of polypropylene biocomposites reinforced with short flax and pine fibers. Compos Part C Open Access 2022, 9, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, R.M.; Pettersen, R.; Han, J.S.; Rowell, J.S.; Tshabalala, M.A. Cell wall chemistry. Handb Wood Chem Wood Compos 2005, 2, 33–72. [Google Scholar]

- Río Andrade, J.C.d.; Rencoret, J.; Gutiérrez Suárez, A.; Nieto, L.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.; Martínez, Á.T. Structural characterization of guaiacyl-rich lignins in flax (Linum usitatissimum) fibers and shives 2011.

- Sain, M.; Park, S.H.; Suhara, F.; Law, S. Flame retardant and mechanical properties of natural fibre–PP composites containing magnesium hydroxide. Polym Degrad Stab 2004, 83, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Goh, K.L. Effect of Mercerization/Alkali Surface Treatment of Natural Fibres and Their Utilization in Polymer Composites: Mechanical and Morphological Studies. J Compos Sci 2021, 5, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanivada, U.K.; Mármol, G.; Brito, F.P.; Fangueiro, R. PLA Composites Reinforced with Flax and Jute Fibers—A Review of Recent Trends, Processing Parameters and Mechanical Properties. Polym 2020, 12, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmi Narayana, V.; Bhaskara Rao, L. A brief review on the effect of alkali treatment on mechanical properties of various natural fiber reinforced polymer composites. Mater Today Proc 2021, 44, 1988–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, M.; Tabarsa, T.; Ashori, A.; Madhoushi, M.; Shakeri, A. A comparative study on some properties of wood plastic composites using canola stalk, Paulownia, and nanoclay. J Appl Polym Sci 2013, 129, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, T. Structure and Mechanical Behaviour of Wood-Fibre Composites. 2014.

- Adediran, A.A.; Akinwande, A.A.; Balogun, O.A.; Bello, O.S.; Akinbowale, M.K.; Adesina, O.S.; et al. Mechanical and optimization studies of polypropylene hybrid biocomposites. Sci Reports 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglia, D.; Biagiotti, J.; Kenny, J.M. A review on natural fibre-based composites—Part II: Application of natural reinforcements in composite materials for automotive industry. J Nat Fibers 2005, 1, 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.Y.; Feng, X.Q.; Lauke, B.; Mai, Y.W. Effects of particle size, particle/matrix interface adhesion and particle loading on mechanical properties of particulate-polymer composites. Compos Part B Eng 2008, 39, 933–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, K.L.; Efendy, M.G.A.; Le, T.M. A review of recent developments in natural fibre composites and their mechanical performance. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2016, 83, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netravali, A.N.; Chabba, S. Composites get greener. Mater Today 2003, 6, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.F.; Mou, H.Y.; Li, Q.Y.; Wang, J.K.; Guo, W.H. Influence of heat treatment on the heat distortion temperature of poly(lactic acid)/bamboo fiber/talc hybrid biocomposites. J Appl Polym Sci 2012, 123, 2828–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.S.; Drzal, L.T.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K.; Williams, K.; Mielewski, D.F. A Study on Biocomposites from Recycled Newspaper Fiber and Poly(lactic acid). Ind Eng Chem Res 2005, 44, 5593–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Kim, M.W.; Song, Y.S.; Kang, T.J.; Youn, J.R. Mechanical properties of denim fabric reinforced poly(lactic acid). Fibers Polym 2010, 11, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Aguirre, J.P.; Luna-Vera, F.; Caicedo, C.; Vera-Mondragón, B.; Hidalgo-Salazar, M.A. The Effects of Reprocessing and Fiber Treatments on the Properties of Polypropylene-Sugarcane Bagasse Biocomposites. Polym 2020, 12, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Rayung, M.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Shazleen, S.S.; Rani, M.S.A.; et al. Thermogravimetric Analysis Properties of Cellulosic Natural Fiber Polymer Composites: A Review on Influence of Chemical Treatments. Polym 2021, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, S.H.; Mohd Basri, M.S.; Rayung, M.; Abu, F.; Ahmad, S.; Norizan, M.N.; et al. A review on natural fiber reinforced polymer composites (NFRPC) for sustainable industrial applications. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanth, M.; Bhat, K.S. Conventional and unconventional chemical treatment methods of natural fibres for sustainable biocomposites. Sustain Chem Clim Action 2023, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, M.S.; Islam, T.; Islam, G.M.S. Injection-molded natural fiber-reinforced polymer composites–a review. Int J Mech Mater Eng 2021, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Ventura, E.M.; Escalante-Álvarez, M.A.; González-Nuñez, R.; Esquivel-Alfaro, M.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B. Polypropylene Composites Reinforced with Lignocellulose Nanocrystals of Corncob: Thermal and Mechanical Properties. J Compos Sci 2024, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, H.; El-Wakil, A.E.-A.A.; Nour, M.T.; Youssef, A.M. Kenaf fibre treatment and its impact on the static, dynamic, hydrophobicity and barrier properties of sustainable polystyrene biocomposites. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 29296–29305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarudin, S.H.; Abdullah, L.C.; Aung, M.M.; Ratnam, C.T.; Jusoh, E.R. A study of mechanical and morphological properties of PLA based biocomposites prepared with EJO vegetable oil based plasticiser and kenaf fibres. Mater Res Express 2018, 5, 85314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartos, A.; Nagy, K.; Anggono, J.; Antoni Purwaningsih, H.; Móczó, J.; et al. Biobased PLA/sugarcane bagasse fiber composites: Effect of fiber characteristics and interfacial adhesion on properties. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2021, 143, 106273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapa, I.R.; Shanks, R.A.; Kong, I.; Daud, N. Morphological structure and thermomechanical properties of hemp fibre reinforced poly(lactic acid) Nanocomposites plasticized with tributyl citrate. Mater Today Proc 2018, 5, 3211–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suardana, N.P.G.; Piao, Y.; Lim, J.K. Mechanical properties of hemp fibers and hemp/pp composites: Effects of chemical surface treatment. Mater Phys Mech 2011, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).