Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- polypropylene homopolymer PP J700 TEHNOLEN supplied by MONOFIL SRL, Piatra Neamț, Romania. The characteristics of the PP used are presented in Table 1.

- wood powder, obtained from industrial waste, specifically beech, poplar, and pine wood residues. These waste materials were dried at 40°C, ground, and sieved to achieve a particle size of up to 200 μm;

- flax fibers (MONOFIL SRL, Piatra Neamț, Romania) with an outer diameter of about 10-30 μm, a density of 1.4 ± 0.1 g/cm³, a modulus of elasticity of 60 ± 3 GPa, a tensile strength of 1.2 ± 0.2 GPa, and an elongation at fracture of 2.5 ± 0.5%.

| Properties | Value | Unit | Determination method |

| Melt flow index (230°C, 2.16 kg) | 9.96 | g/10 min | SR EN ISO 1133-1:2022 B [25] |

| Density (23°C) | 0.905 | g/cm3 | SR EN ISO 1183-1:2019 [26] |

| Vicat softening temperature – load 50 N |

163 | °C | SR EN ISO 306:2023 [27] |

| Tensile flow strength | 39.5 | MPa | SR EN ISO 527-1:2020 [28] SR EN ISO 527-2:2012 [29] |

| Tensile breaking strength | 25.6 | MPa | |

| Tensile elongation at break | 10.52 | % | |

| Tensile modulus of elasticity | 1923.73 | MPa | |

| Maximum flexural stress | 53 | MPa | SR EN ISO 14125:2000/AC:2003 [30] |

| Flexural modulus | 1782.3 | MPa | SR EN ISO 178:2019 [31] |

2.2. Methods and Equipment

2.2.1. Obtaining Polymer Composite Materials

2.2.2. Characterization Methods

2.2.2.1. Optical Microscopy

2.2.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

2.2.2.3. Thermal Analysis

2.2.2.4. Density

2.2.2.5. Mechanical Tests

2.2.2.6. Dielectric Tests

2.2.2.7. Deterioration Tests due to the Action of Fungi

3. Results

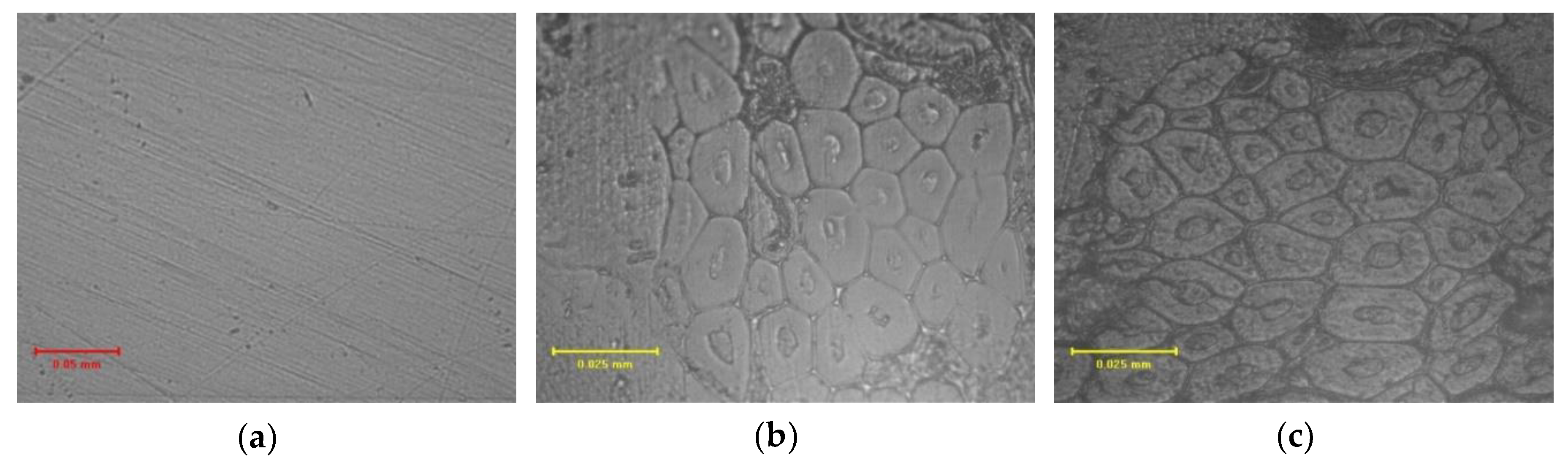

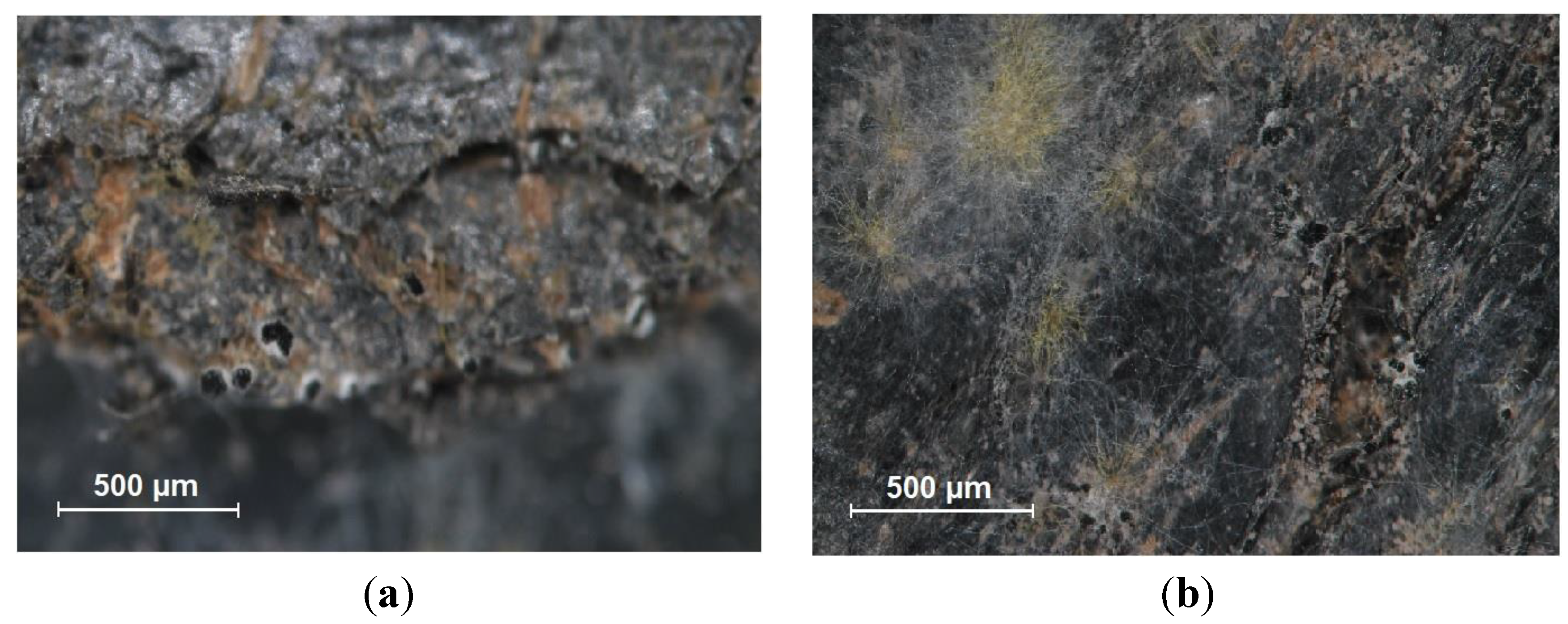

3.1. Optical Microscopy

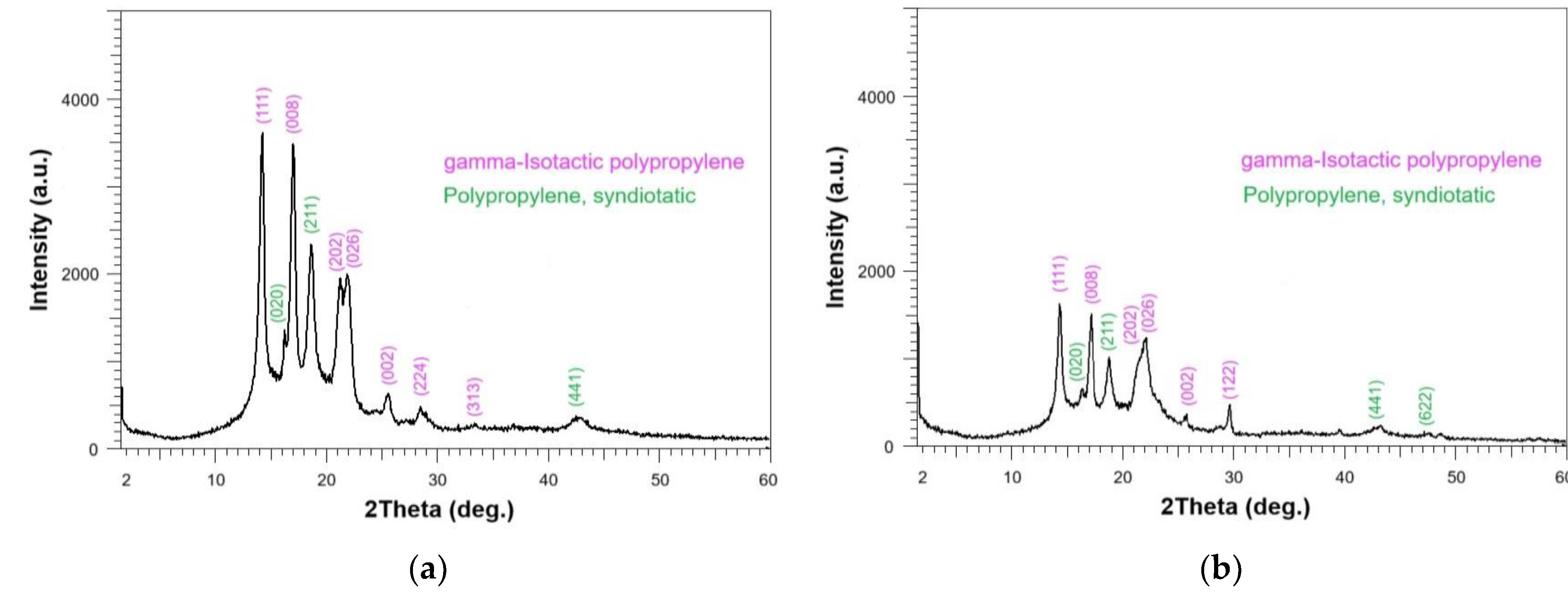

3.2. XRD Analysis

- All the developed polymer materials contain crystalline phases characteristic of PP, including gamma-isotactic polypropylene (PDF reference card no. 00-0451807) and syndiotatic polypropylene (PDF reference card no. 00-049-2204).

- The PP polymer exhibits the highest peak intensities, whereas both polymer composites show lower peak intensities due to texturing effect introduced by the fillers (wood flour and flax fiber).

- Among the polymer composite materials with hybrid fillers, the M3 composite was found to have the highest proportion of ordered (crystalline) phases.

- All the polymer materials crystallize in an orthorhombic system, with crystallite sizes of 20.8 nm (M1), 19.2 nm (M2), and 23.2 nm (M3). The addition of natural fillers did not alter the structure of the PP polymer matrix.

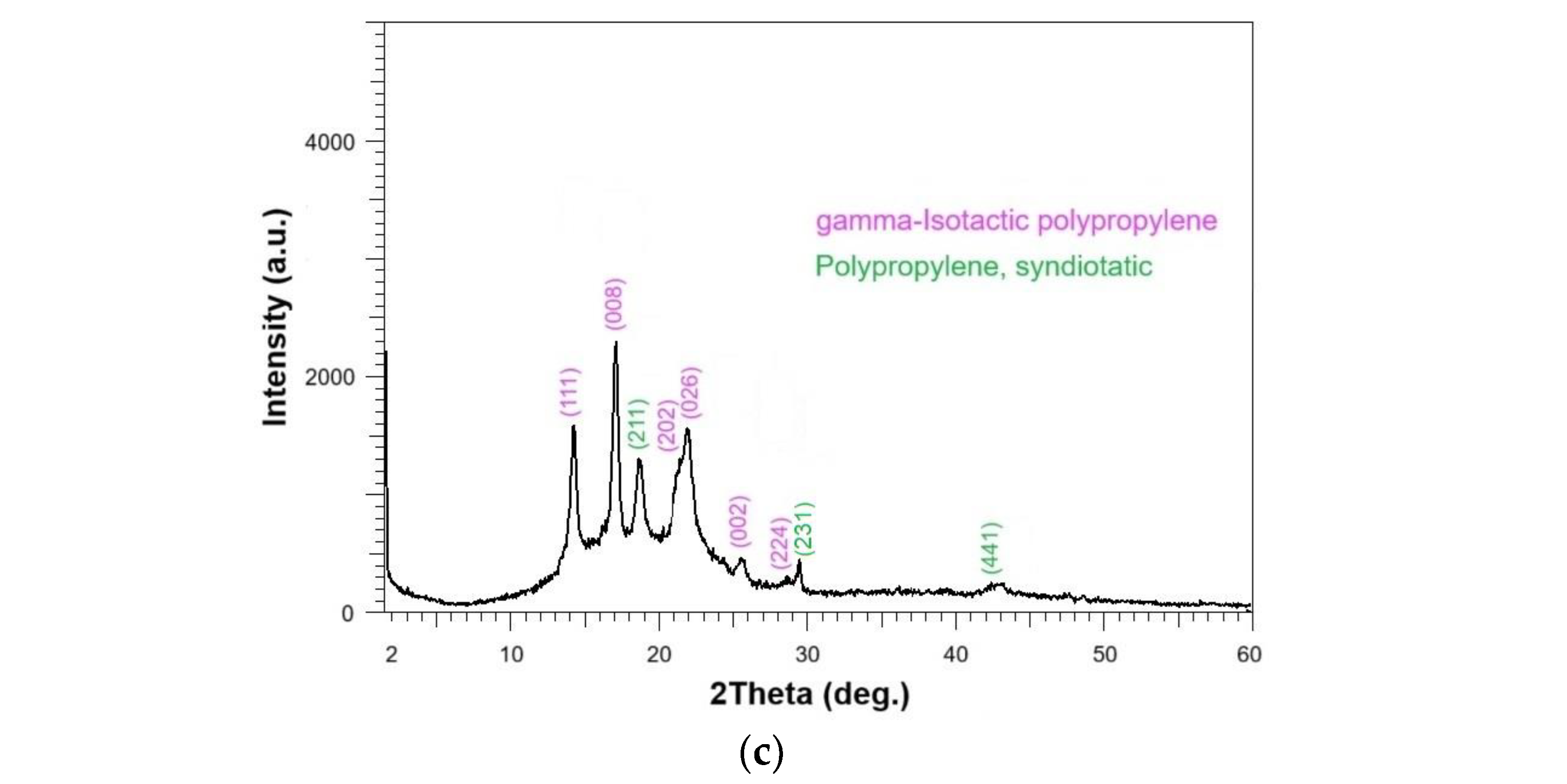

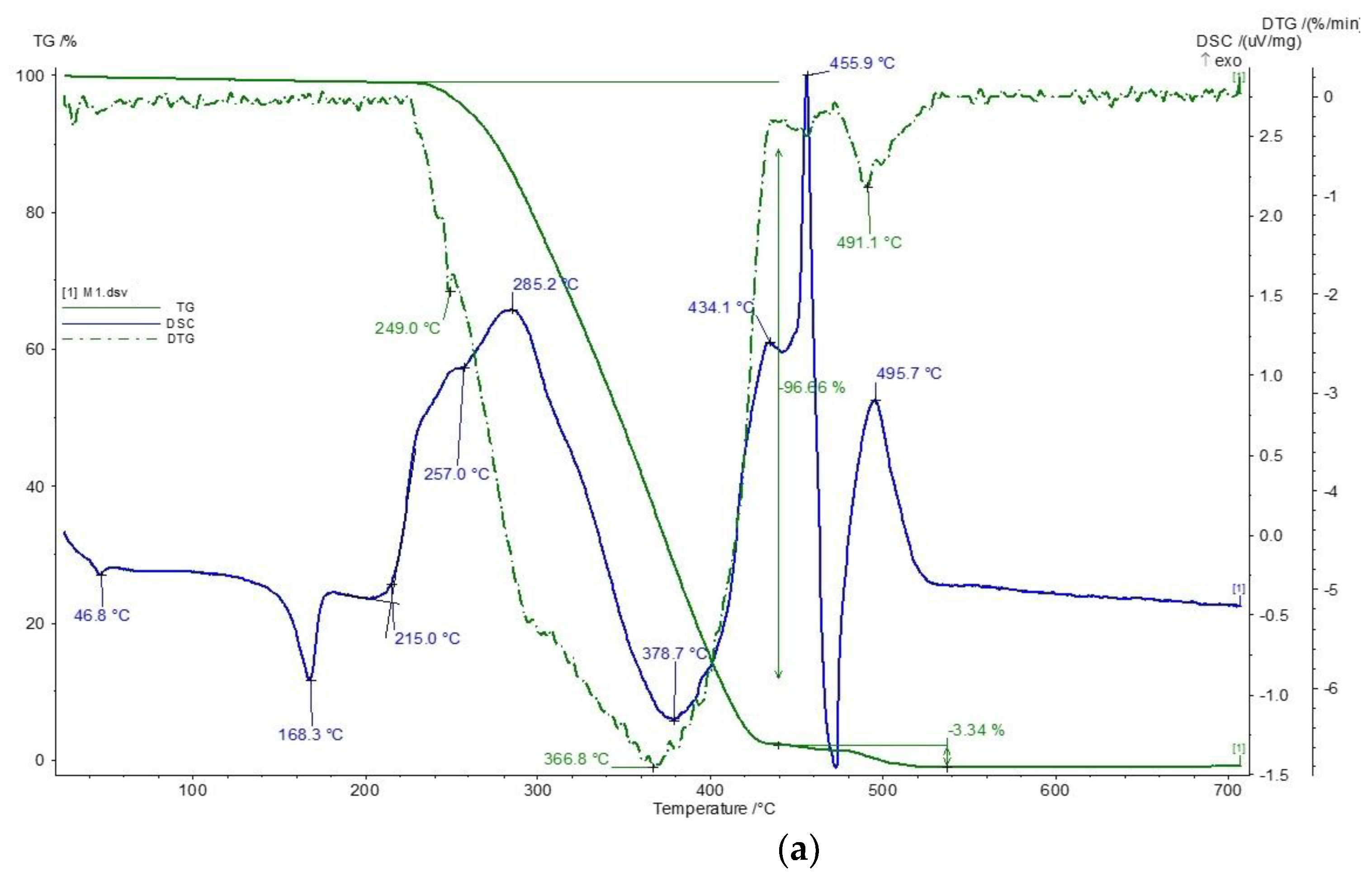

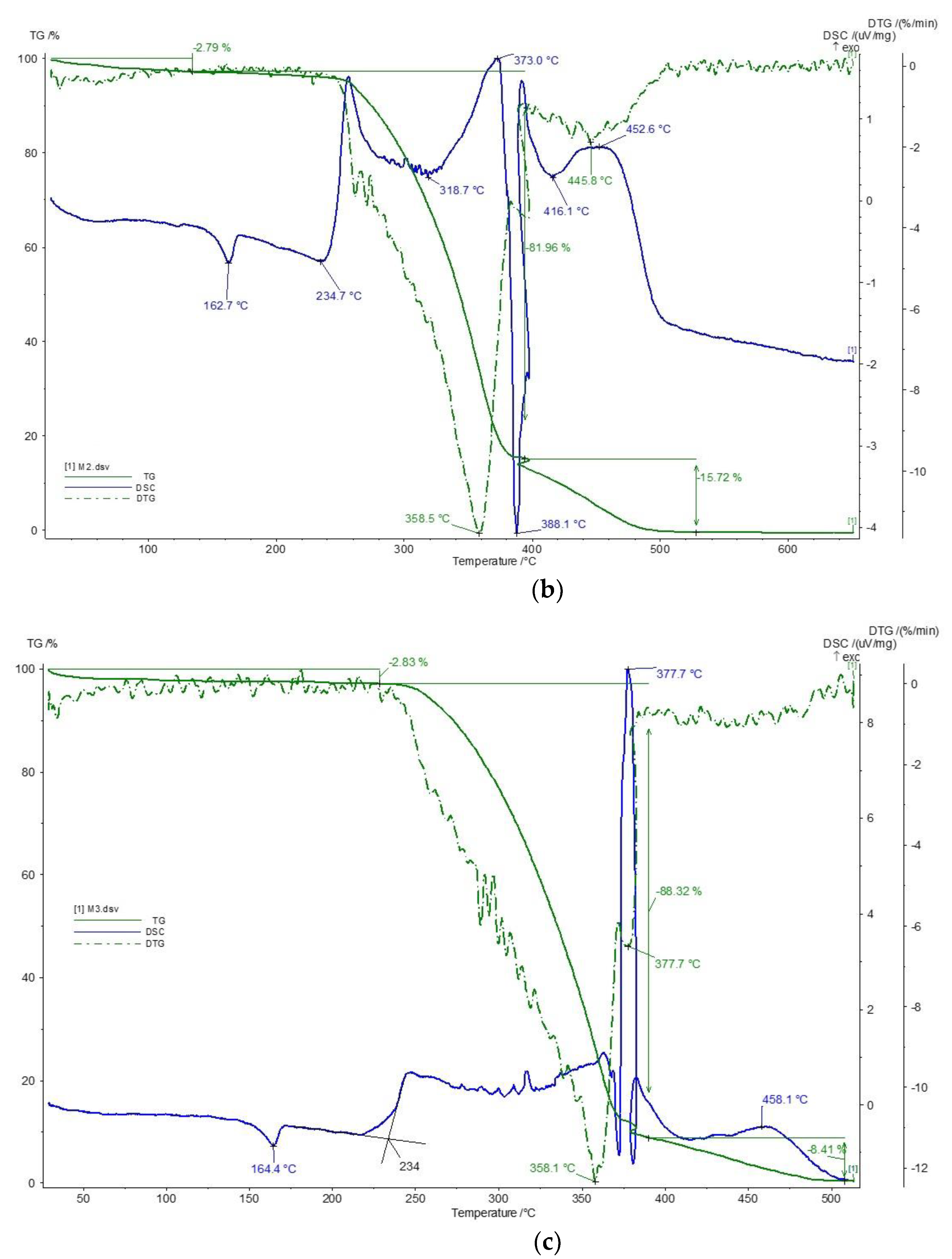

3.3. Thermal Analysis

- Process I - Water loss occurs in the M2 and M3 polymer composite materials.

- Process II - Melting (Tmin DSC) occurs in all the analyzed polymer materials. It is noted that the M2 and M3 composites have a melting point close to that of polypropylene (M1). The minor differences between these melting points are attributed to the fillers used and probably the inhomogeneity of the samples.

- Process III – Thermal oxidation with the formation of solid products. During thermal oxidation, polymer materials react with oxygen, leading to the formation of hydroperoxides (-OOH) as primary degradation products [39]. The initial temperature of the first oxidation process (TIN) with the formation of solid hydroperoxides indicates the stability of the materials to oxidation. The stability to thermal oxidation increases as the initial temperature (TIN) of the process with the formation of solid hydroperoxides rises. The thermal stability increased with higher TIN in the following order: M1 < M3 < M2. However, it remained similar for both polymer composites.

- Process IV – Thermal oxidation with the decomposition driven by radicals and volatile oxidation occurs in all the analyzed polymer materials above the temperature of 434°C. This process is detected as exothermic peaks due to combustion-like reactions [39,40]. The presence of natural hybrid fillers did not increase the thermal decomposition temperature of the PP component from both polymer composites.

3.4. Density

3.5. Mechanical Tests

3.6. Dielectric Tests

3.7. Deterioration Tests due to the Action of Fungi

- The highest weight loss was recorded for the M3 composite (6.91%), followed by M2 (4.73%) and M1 (0.69%) after 3 months. In general, for the samples with the highest and lowest weight losses, these results correlate with the degree of mould coverage.

- After 180 days (6 months) of exposure in the biodegradation environment, the weight loss for the M3 composite was found to be 12.58%, while for the M2 composite the weight loss value was measured at 7.58%.

- The lowest weight loss was exhibited by the M1 polymer material (PP), which varied in a narrow range (0.61 - 0.81%) after 1.5 months, and 6 months, respectively.

4. Conclusions

- Optical microscopy and X-ray diffraction analyses highlighted that the M3 composite material with hybrid fillers is the most homogeneous and has the largest portions of ordered phases. All polymer materials crystallize in an orthorhombic system with crystallite sizes of 20.8 nm (M1), 19.2 nm (M2), and 23.2 nm (M3). The addition of natural fillers did not alter the structure of the PP polymer.

- Thermal analyses identified thermograms similar to four processes: water loss (I), which occurs in the M2 and M3 composite materials, melting (II), which identifies the melting point close to the PP matrix, and thermal oxidation with the formation of solid products (III) and decomposition driven by radicals and volatile oxidation (IV). For the investigated series, the thermal stability order is: M1 < M3 < M2. However, it remained similar for both polymer composites.

- Mechanical tests showed that incorporating 5% flax fiber and 25% wood flour reinforcement into a PP matrix reduces Vickers hardness and bending strength (Rm). However, increasing the flax fiber content to 10% and reducing the wood flour to 20% enhances these properties in the M3 composite compared to the M2 composite.

- Density measurements indicate that incorporating hybrid natural fillers increases the density of the M2 and M3 composites. The highest density was observed in M2, which contains the most wood flour, while M3, with the highest flax fiber content, had a lower density than M2 but remained higher than that of the PP polymer (M1).

- Dielectric tests indicated that the volume resistivity decreases with the introduction of a hybrid filler, while the surface resistivity increases with its introduction.

- Deterioration tests due to the action of fungi were conducted over 6 months, after which the polymer materials can be classified based on degradation rate (weight loss) as follows: M3 > M2 > M1.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suriani, M.J.; Ilyas, R.A.; Zuhri, M.Y.M.; Khalina, A.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ruzaidi, C.M.; Wan, F.N.; Zulkifli, F.; Harussani, M.M.; Azman, M.A.; Radzi, F.S.M.; Sharma, S. Critical Review of Natural Fiber Reinforced Hybrid Composites: Processing, Properties, Applications and Cost. Polymers 2021, 13 (20), 3514. [CrossRef]

- Seydibeyoğlu, M.Ö.; Dogru, A.; Wang, J.; Rencheck, M.; Han, Y.; Wang, L.; Seydibeyoğlu, E.A.; Zhao, X.; Ong, K.; Shatkin, J.A.; Shams Es-haghi, S.; Bhandari, S.; Ozcan, S.; Gardner, D.J. Review on Hybrid Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composites with Nanocellulose, Nanomaterials, and Other Fibers. Polymers 2023, 15 (4), 984. [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A.K.; Manik, G. Advances towards Development of Industrially Relevant Short Natural Fiber Reinforced and Hybridized Polypropylene Composites for Various Industrial Applications: A Review. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30 (1), 47. [CrossRef]

- Prem Kumar, R.; Muthukrishnan, M.; Felix Sahayaraj, A. Effect of Hybridization on Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composite Materials – A Review. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44 (8), 4459–4479. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.O.; Akpan, E.; Dhakal, H.N. Review on Natural Plant Fibres and Their Hybrid Composites for Structural Applications: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Compos. C: Open Access 2022, 9, 100322. [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.; Queiroz, H.; Aguiar, R.; Lima, R.; Cavalcanti, D.; Doina Banea, M. A Review of Recent Advances in Hybrid Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites. J. Renew. Mater. 2022, 10 (3), 561–589. [CrossRef]

- Çavuş, V. Selected Properties of Mahogany Wood Flour Filled Polypropylene Composites: The Effect of Maleic Anhydride-Grafted Polypropylene (MAPP). BioRes 2020, 15 (2), 2227–2236. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.K.; Thakur, M.K. Processing and Characterization of Natural Cellulose Fibers/Thermoset Polymer Composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 109, 102–117. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Venkatesh, R.; Chaturvedi, R.; Kumar, R.; Vivekananda, P.K.K.; Mohanavel, V.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Al Obaid, S.; Salmen, S.H. Polypropylene Matrix Embedded with Curaua Fiber through Hot Compression Processing: Characteristics Study. J. Polym. Res. 2024, 31 (9), 260. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Yeasmin, M.S. A State-of-the-Art Review Focusing on the Significant Techniques for Naturally Available Fibers as Reinforcement in Sustainable Bio-Composites: Extraction, Processing, Purification, Modification, as Well as Characterization Study. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101511. [CrossRef]

- Aravindh, M.; Sathish, S.; Ranga Raj, R.; Karthick, A.; Mohanavel, V.; Patil, P.P.; Muhibbullah, M.; Osman, S.M. A Review on the Effect of Various Chemical Treatments on the Mechanical Properties of Renewable Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Pathan, S.; Dinesh; Biswas, K.; Palsule, S. Recycled Wood Fiber Reinforced Chemically Functionalized Polyethylene (VLDPE) Composites by Palsule Process. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19 (17), 15519–15530. [CrossRef]

- Dinesh; Palsule, S. Bagasse Fiber Reinforced Functionalized Ethylene Propylene Rubber Composites by Palsule Process. J. Nat. Fibers 2021, 18 (11), 1637–1649. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Palsule, S. Bamboo Fiber Reinforced Chemically Functionalized Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene Composites by Palsule Process. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20 (1), 2150741. [CrossRef]

- Tamta, N.; Palsule, S. Kenaf Fiber Reinforced Chemically Functionalized Styrene-Acrylonitrile Composites. J. Thermoplas. Compos. Mater. 2024, 37 (1), 5–27. [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.; Palsule, S. Bagasse Fiber Reinforced Chemically Functionalized Polystyrene Composites. J. Thermoplas. Compos. Mater. 2024, 37 (1), 251–275. [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, J.; Barczewski, M.; Czarnecka-Komorowska, D.; Rydzkowski, T.; Gawdzińska, K.; Thakur, V.K. Manufacturing and Characterization of Sustainable and Recyclable Wood-Polypropylene Biocomposites: Multiprocessing-Properties-Structure Relationships. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 207, 117710. [CrossRef]

- Caramitu, A.R.; Ciobanu, R.C.; Ion, I.; Marin, M.; Lungulescu, E.-M.; Marinescu, V.; Aflori, M.; Bors, A.M. Composites from Recycled Polypropylene and Carboxymethylcellulose with Potential Uses in the Interior Design of Vehicles. Polymers 2024, 16 (15), 2188. [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou, A.; Davies, P.; Baley, C. Environmental Impact Analysis of the Production of Flax Fibres to Be Used as Composite Material Reinforcement. J. Biobased Mat. Bioenergy 2011, 5 (1), 153–165. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.V.; Yadav, A.; Winczek, J. Physical, Mechanical, and Thermal Properties of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composites for Construction and Automotive Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13 (8), 5126. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Sharma, V.; Upadhyay, N.; Gill, S.; Sihag, M. Flax and Flaxseed Oil: An Ancient Medicine & Modern Functional Food. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51 (9), 1633–1653. [CrossRef]

- Romhány, G.; Karger-Kocsis, J.; Czigány, T. Tensile Fracture and Failure Behavior of Technical Flax Fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90 (13), 3638–3645. [CrossRef]

- Charlet, K.; Beakou, A. Interfaces within Flax Fibre Bundle: Experimental Characterization and Numerical Modelling. J. Compos. Mater. 2014, 48 (26), 3263–3269. [CrossRef]

- Mattrand, C.; Béakou, A.; Charlet, K. Numerical Modeling of the Flax Fiber Morphology Variability. Compos. - A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2014, 63, 10–20. [CrossRef]

- SR EN ISO 1133-1:2022, Plastics - Determination of the Melt Mass-Flow Rate (MFR) and Melt Volume-Flow Rate (MVR) of Thermoplastics. Part 1: Standard Method.

- SR EN ISO 1183-1:2019, Plastics - Methods for Determining the Density of Non-Cellular Plastics. Part 1: Immersion Method, Liquid Pycnometer Method and Titration Method.

- SR EN ISO 306:2023, Plastics -Thermoplastic Materials. Determination of Vicat Softening Temperature (VST).

- SR EN ISO 527-1:2020, Plastics. Determination of Tensile Properties Part 1: General Principles.

- SR EN ISO 527-2:2012, Plastics. Determination of Tensile Properties Part 2: Test Conditions for Moulding and Extrusion Plastics.

- SR EN ISO 14125:2000/AC:2003, Fibre-Reinforced Plastic Composites. Determination of Flexural Properties.

- SR EN ISO 178:2019, Plastics. Determination of Flexural Properties.

- SR EN ISO 6507-1:2023, Metallic Materials - Vickers Hardness Test. Part 1: Test Method.

- IEC 62631-3-1:2023, Dielectric and Resistive Properties of Solid Insulating Materials. Part 3-1: Determination of Resistive Properties (DC Methods) - Volume Resistance and Volume Resistivity - General Method.

- IEC 62631-3-2:2023, Dielectric and Resistive Properties of Solid Insulating Materials. Part 3-2: Determination of Resistive Properties (DC Methods) - Surface Resistance and Surface Resistivity.

- SR EN 60068-2-10:2006/A1:2019, Environmental Testing. Part 2-10: Tests - Test J and Guidance: Mould Growth.

- SR EN ISO 846:2019, Plastics – Evaluation of the Action of Microorganisms.

- Romhány, G.; Karger-Kocsis, J.; Czigány, T. Tensile Fracture and Failure Behavior of Technical Flax Fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90 (13), 3638–3645. [CrossRef]

- Parodo, G.; Sorrentino, L.; Turchetta, S.; Moffa, G. Manufacturing of Sustainable Composite Materials: The Challenge of Flax Fiber and Polypropylene. Materials 2024, 17 (19), 4768. [CrossRef]

- Gijsman, P. Review on the Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Polymers during Processing and in Service. e-Polymers 2008, 8 (1). [CrossRef]

- Mentes, D.; Nagy, G.; Szabó, T.J.; Hornyák-Mester, E.; Fiser, B.; Viskolcz, B.; Póliska, C. Combustion Behaviour of Plastic Waste – A Case Study of PP, HDPE, PET, and Mixed PES-EL. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136850. [CrossRef]

- Elfaleh, I.; Abbassi, F.; Habibi, M.; Ahmad, F.; Guedri, M.; Nasri, M.; Garnier, C. A Comprehensive Review of Natural Fibers and Their Composites: An Eco-Friendly Alternative to Conventional Materials. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101271. [CrossRef]

- Bakar, M.B.A.; Ishak, Z.A.M.; Taib, R.M.; Rozman, H.D.; Jani, S.M. Flammability and Mechanical Properties of Wood Flour-filled Polypropylene Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 116 (5), 2714–2722. [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, A.J.; Sturm, P.C.; Kenny, J.M.; Aranguren, M.I.; Marcovich, N.E.; Reboredo, M.M. Mechanical Characterization of Polypropylene–Wood Flour Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 88 (6), 1420–1428. [CrossRef]

- Stark, N.; Rowlands, R. Effects of Wood Fiber Characteristics on Mechanical Properties of Wood/Polypropylene Composites. Wood Fiber Sci. 2003, 35, 167–174.

- Gozdecki, C.; Wilczynski, A.; Kociszewski, M.; Tomaszewska, J.; Zajchowski, S. Mechanical Properties of Wood-Polypropylene Composites with Industrial Wood Particles of Different Sizes. Wood Fiber Sci. 2012, 44, 14–21.

- Arbelaiz, A.; Fernández, B.; Cantero, G.; Llano-Ponte, R.; Valea, A.; Mondragon, I. Mechanical Properties of Flax Fibre/Polypropylene Composites. Influence of Fibre/Matrix Modification and Glass Fibre Hybridization. Compos. - A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2005, 36 (12), 1637–1644. [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Feuchter, M. Mechanical Properties of Composites Used in High-Voltage Applications. Polymers 2016, 8 (7), 260. [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.M.; Ardila-Rey, J.A.; Umar, Y.; Mas’ud, A.A.; Muhammad-Sukki, F.; Jume, B.H.; Rahman, H.; Bani, N.A. Application and Suitability of Polymeric Materials as Insulators in Electrical Equipment. Energies 2021, 14 (10), 2758. [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K.; Lucka, M.; Al Mamun, A.; Michalski, J. Biological and Electrical Resistance of Acetylated Flax Fibre Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. BioRes 2008, 4 (1), 111–125. [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk-Fligier, A.; Polok-Rubiniec, M. Studies of Resistance of PP/Natural Filler Polymer Composites to Decomposition Caused by Fungi. Materials 2021, 14 (6), 1368. [CrossRef]

| Material type | Sample code |

PP/flax fiber/wood flour (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|

| PP | M1 | 100/0/0 |

| PP + 5% flax fiber + 25% wood flour | M2 | 70/5/25 |

| PP + 10% flax fiber + 20% wood flour | M3 | 70/10/20 |

| Sample code |

Process I Water loss |

Process II Melting |

Process III Oxidation |

Process III Thermal oxidation |

Process IV Thermal oxidation |

Δm total (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmin DSC (°C) |

TDTG (°C) |

Δm (%) |

Tmin DSC (°C) |

TIN (°C) |

Tmax DSC (°C) |

TDTG (°C) |

Δm (%) |

Tmax DSC (°C) |

TDTG (°C) |

Δm (%) |

||

| M1 | 46.8 | - | - | 168.3 | 215.0 | 257.0 285.2 |

249.0 | 96.66 | 434.1 455.9 495.7 |

491.1 | 3.34 | 100.00 |

| M2 | - | - | 2.79 | 162.7 | 234.7 | 373.0 445.8 452.6 |

358.5 | 81.96 | 452.6 | 445.8 | 15.72 | 100.47 |

| M3 | - | - | 2.83 | 164.4 | 234.0 | 377.7 | 358.1 | 88.32 | 458.1 | - | 8.41 | 99.55 |

| Sample code | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|

| M1 | 0.879 ± 0.040 |

| M2 | 0.945 ± 0.046 |

| M3 | 0.906 ± 0.050 |

| Sample code | Vickers hardness HV 0.05 |

Flexural strength Rm (N/mm2) |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | 6.90 ± 0.11 | 112.97 ± 1.58 |

| M2 | 6.47 ± 0.29 | 78.52 ± 1.28 |

| M3 | 7.55 ± 0.59 | 89.60 ± 1.52 |

| Sample code |

Volume resistivity, ρv (Ω·m) |

Measurement uncertainty for ρv (Ω·m) |

Surface resistivity, ρs (Ω) |

Measurement uncertainty for ρs (Ω) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 4.67 × 1014 | 1.41 × 1014 | 4.70 × 1015 | 0.98 × 1015 |

| M2 | 1.71 × 1014 | 0.77 × 1014 | 7.76 × 1015 | 4.26 × 1015 |

| M3 | 1.50 × 1014 | 0.49 × 1014 | 11.20 × 1015 | 5.76 × 1015 |

| Sample code |

Grades: 0 - 5 (according to method B of [36]) | Observations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 days | 90 days | 180 days | ||

| M1 | 01, 01, 01-1, 01-1 | 1, 1-2, 1-2, 2 | 1, 1, 1, 1-2 | Myrothecium verrucaria, Trichoderma viride, Aspergillus flavus, Paecilomyces variotii |

| M2 | 3, 3-4, 4, 4-5 | 3, 3, 3-4, 3-4 | 4-5, 4-5, 5, 5 | Sporodochia of Myrothecium verrucaria, Trichoderma viride, Paecilomyces variotii, and Chaetomium globosum, along with cracks |

| M3 | 1-2, 2-3, 3, 3-4 | 3-4, 3-4, 4, 4-5 | 5, 5, 5, 5 | Sporodochia of Myrothecium verrucaria, and Chaetomium globosum, along with cracks |

| Sample code |

Weight loss (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 days | 90 days | 180 days | |

| M1 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.81 |

| M2 | 2.89 | 4.73 | 7.58 |

| M3 | 4.82 | 6.91 | 12.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).