Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

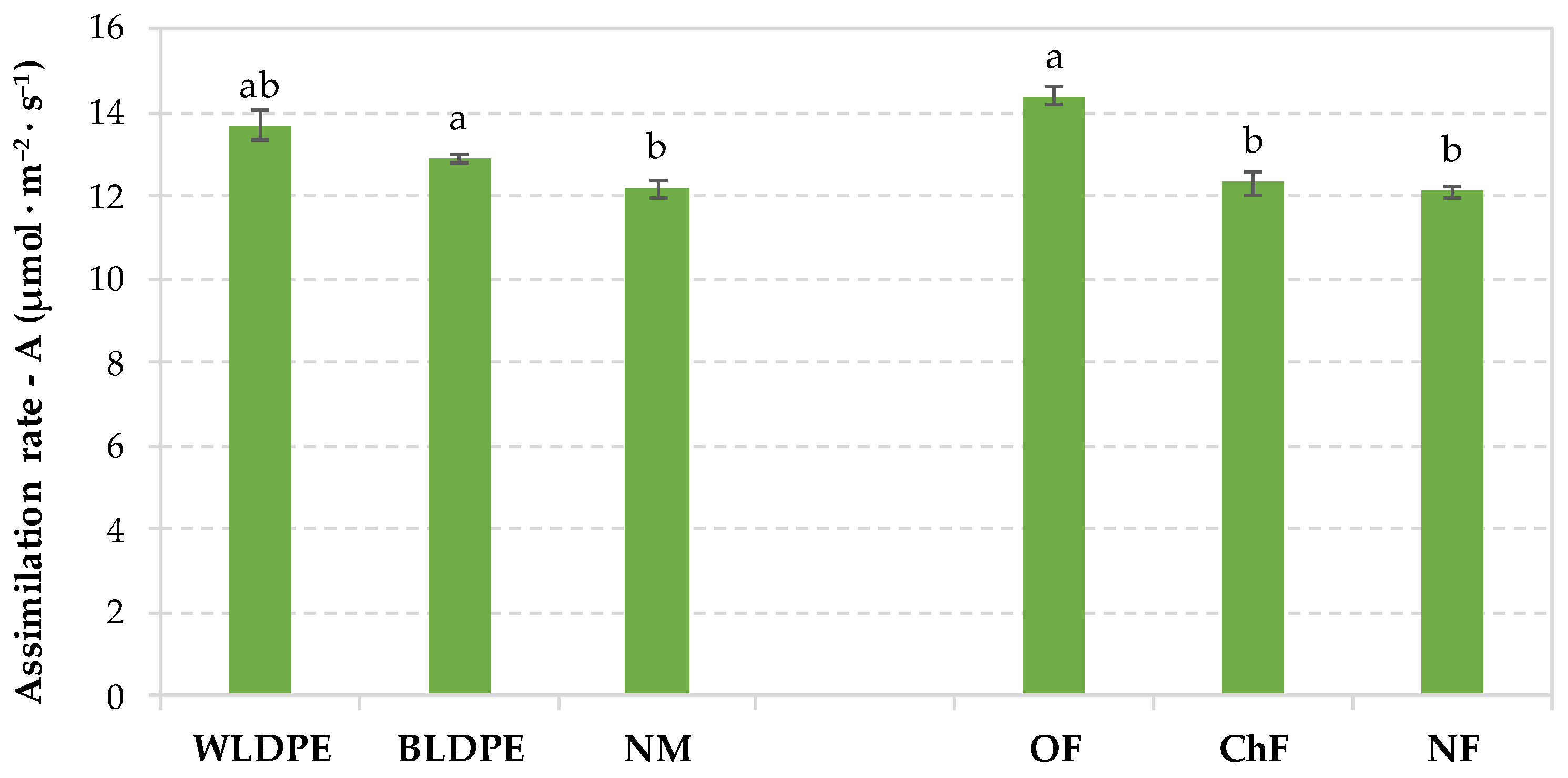

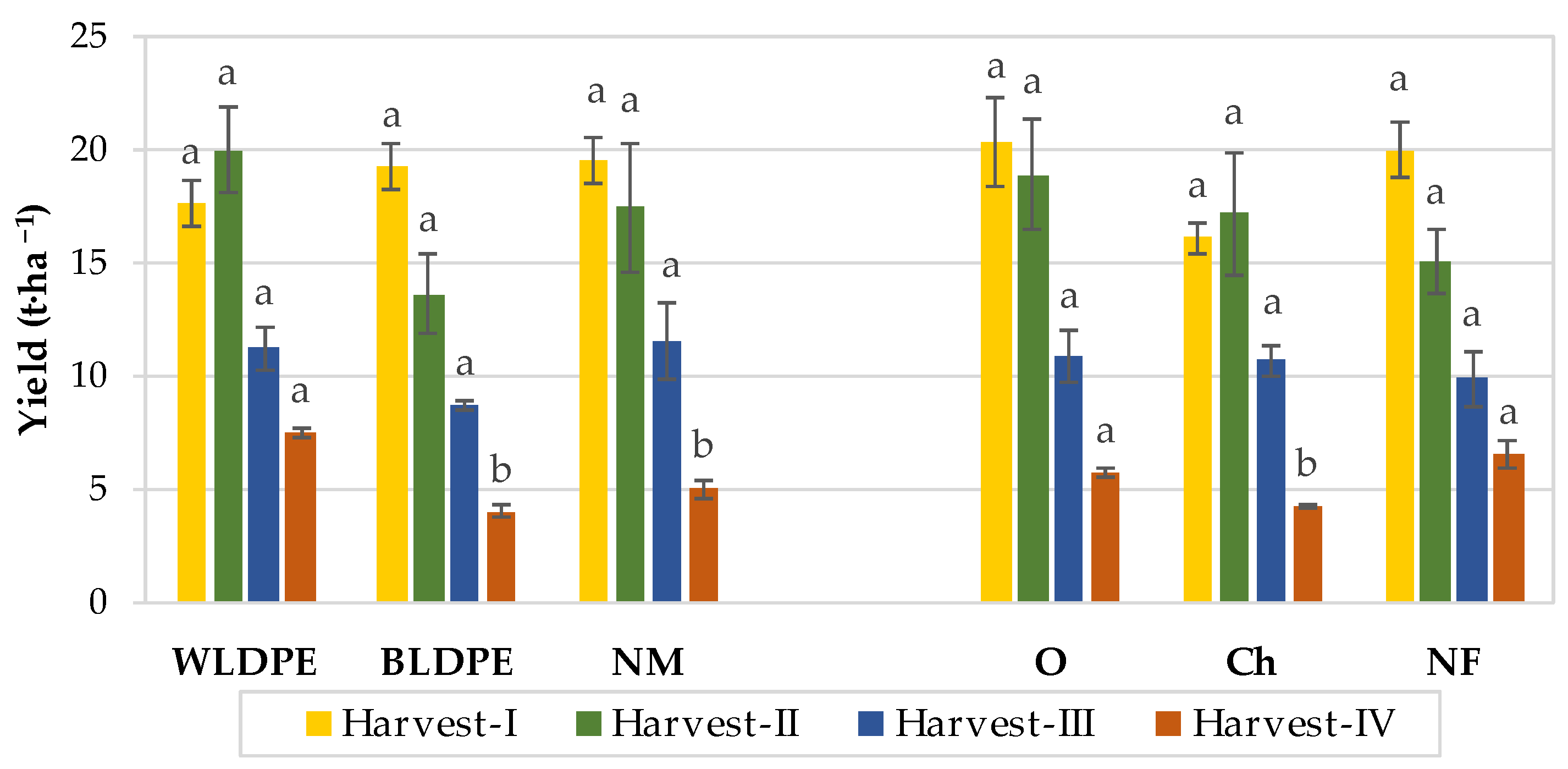

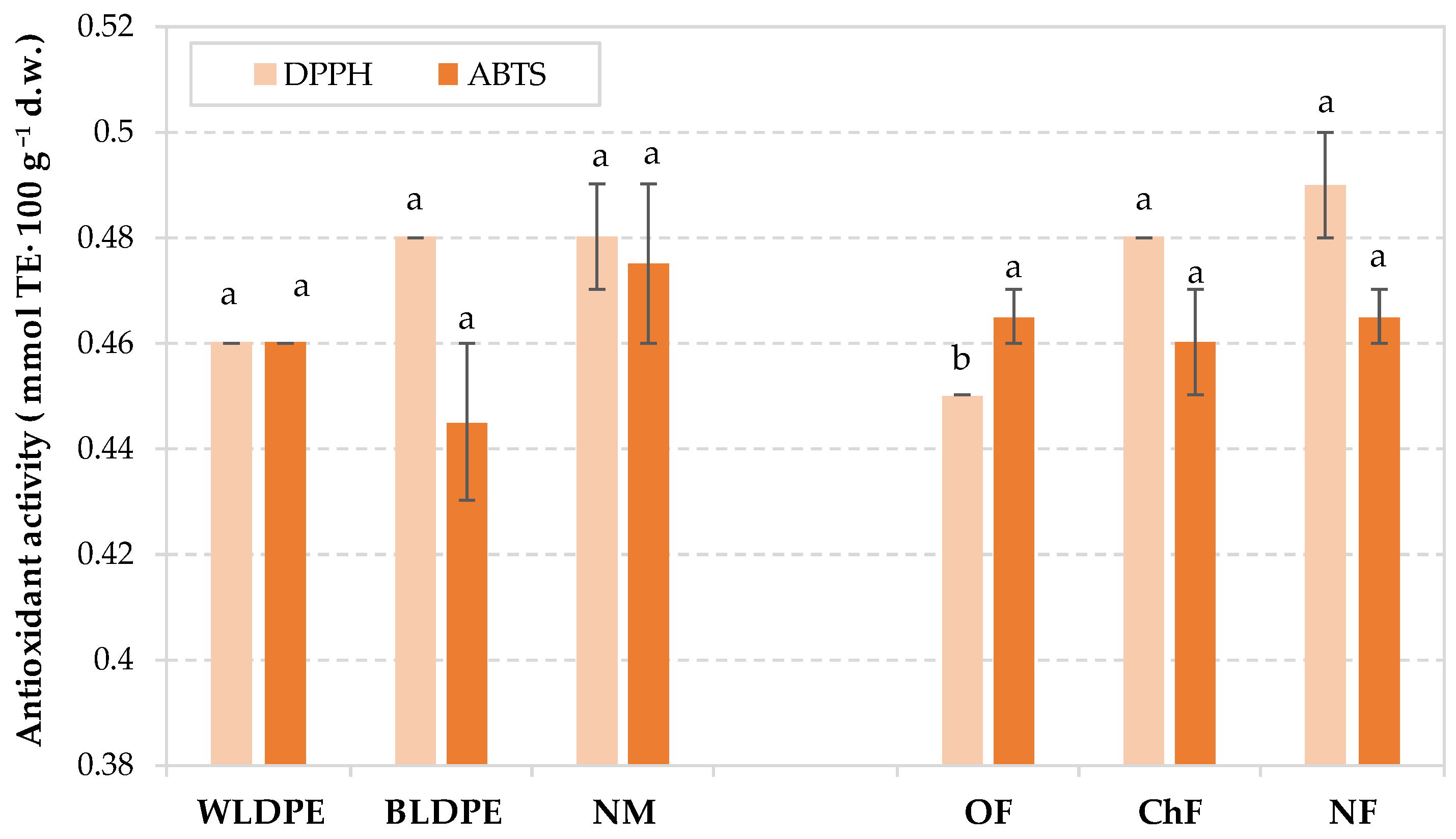

2.1. Individual Influences of Factors on the Characteristics of Perennial Wall‒Rocket

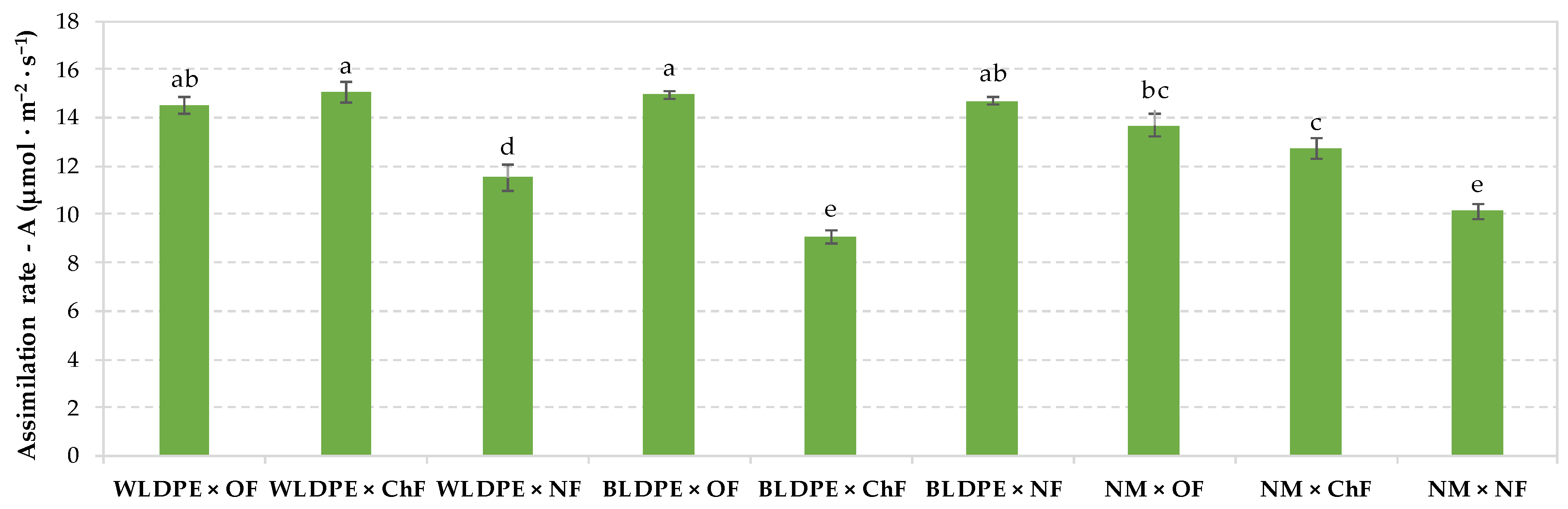

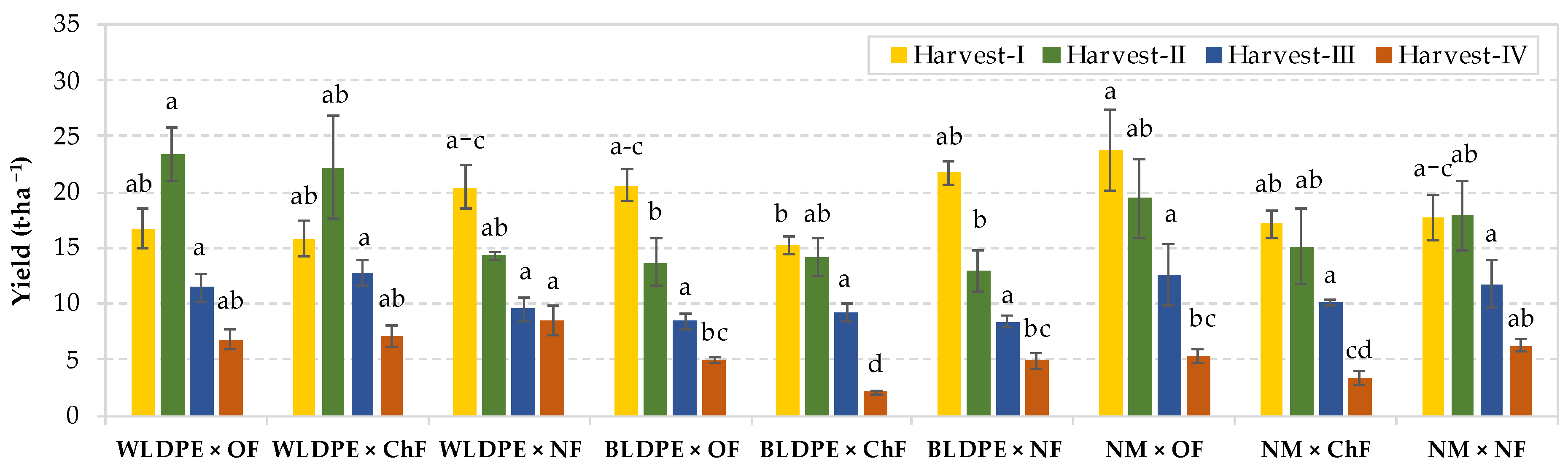

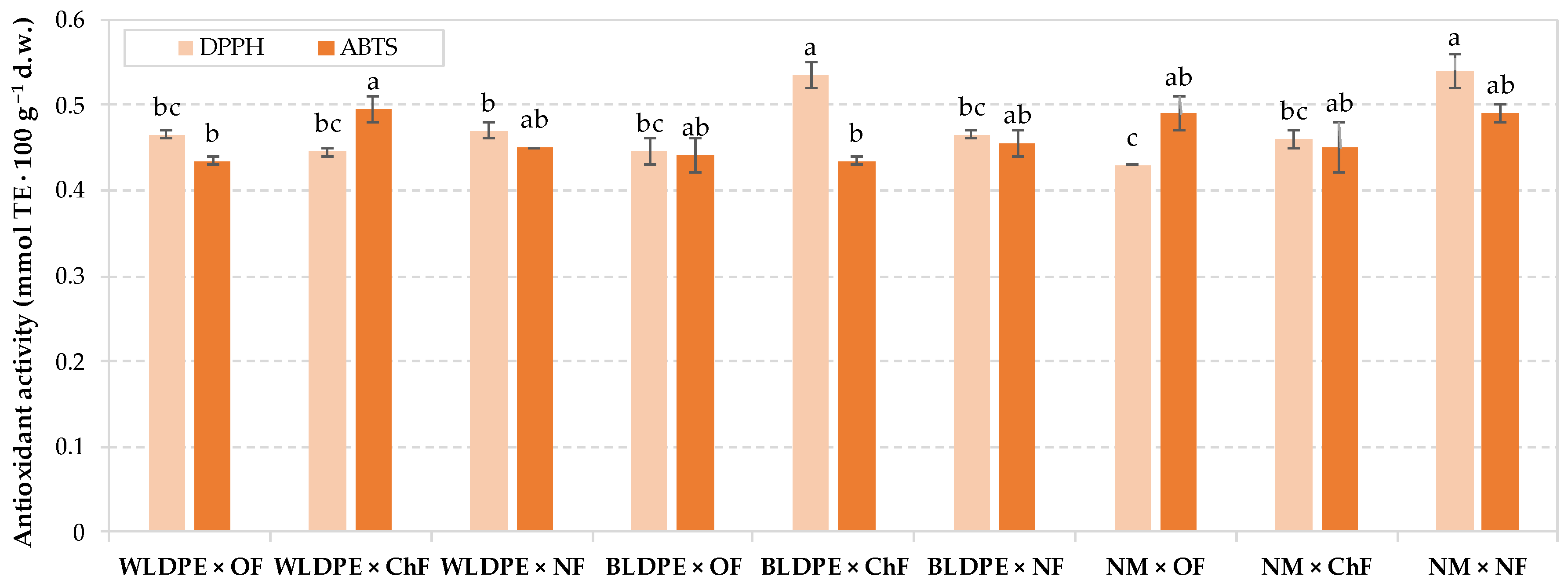

2.2. Cumulative Influence of Factors on the Characteristics of Perennial Wall‒Rocket

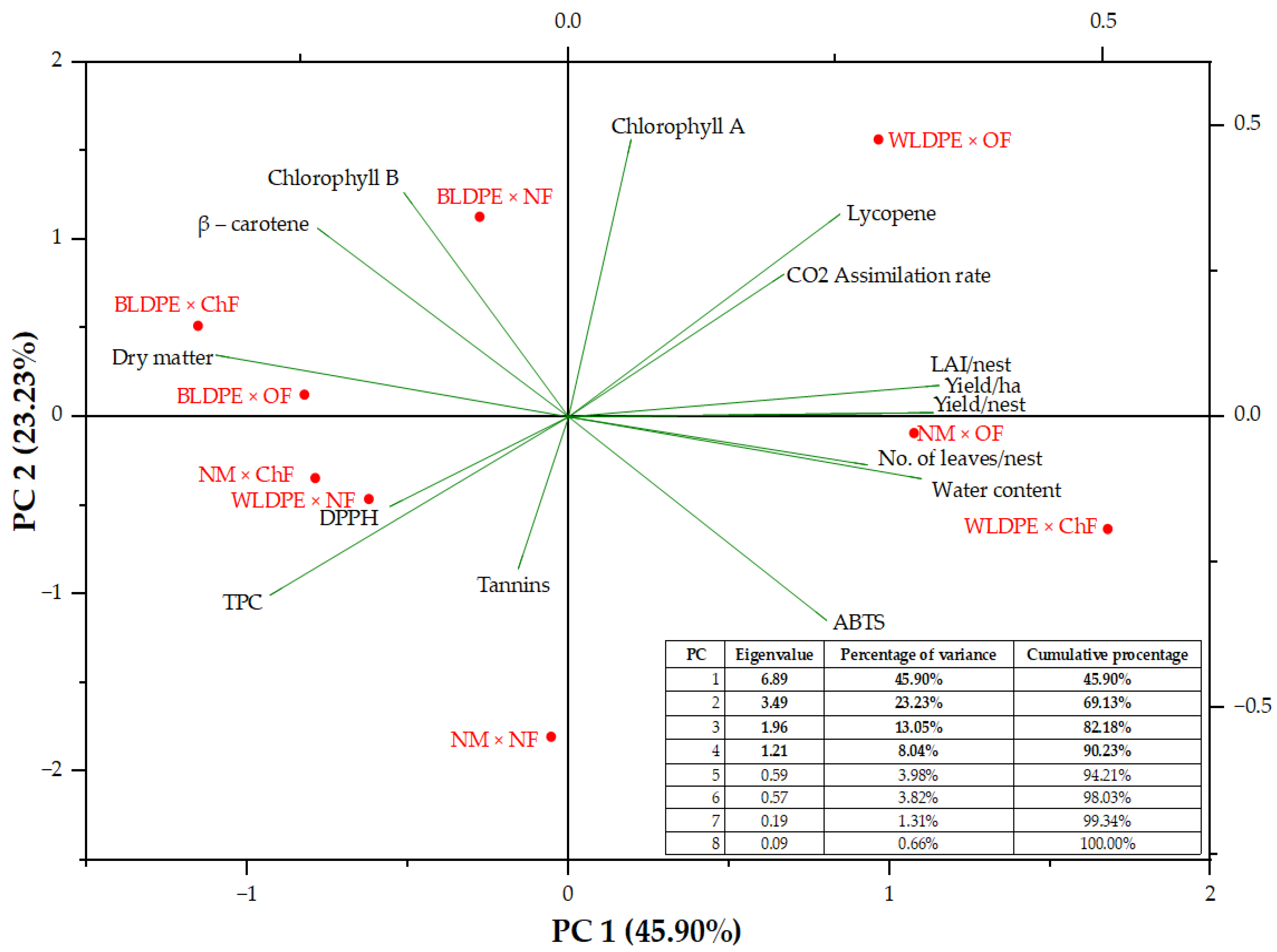

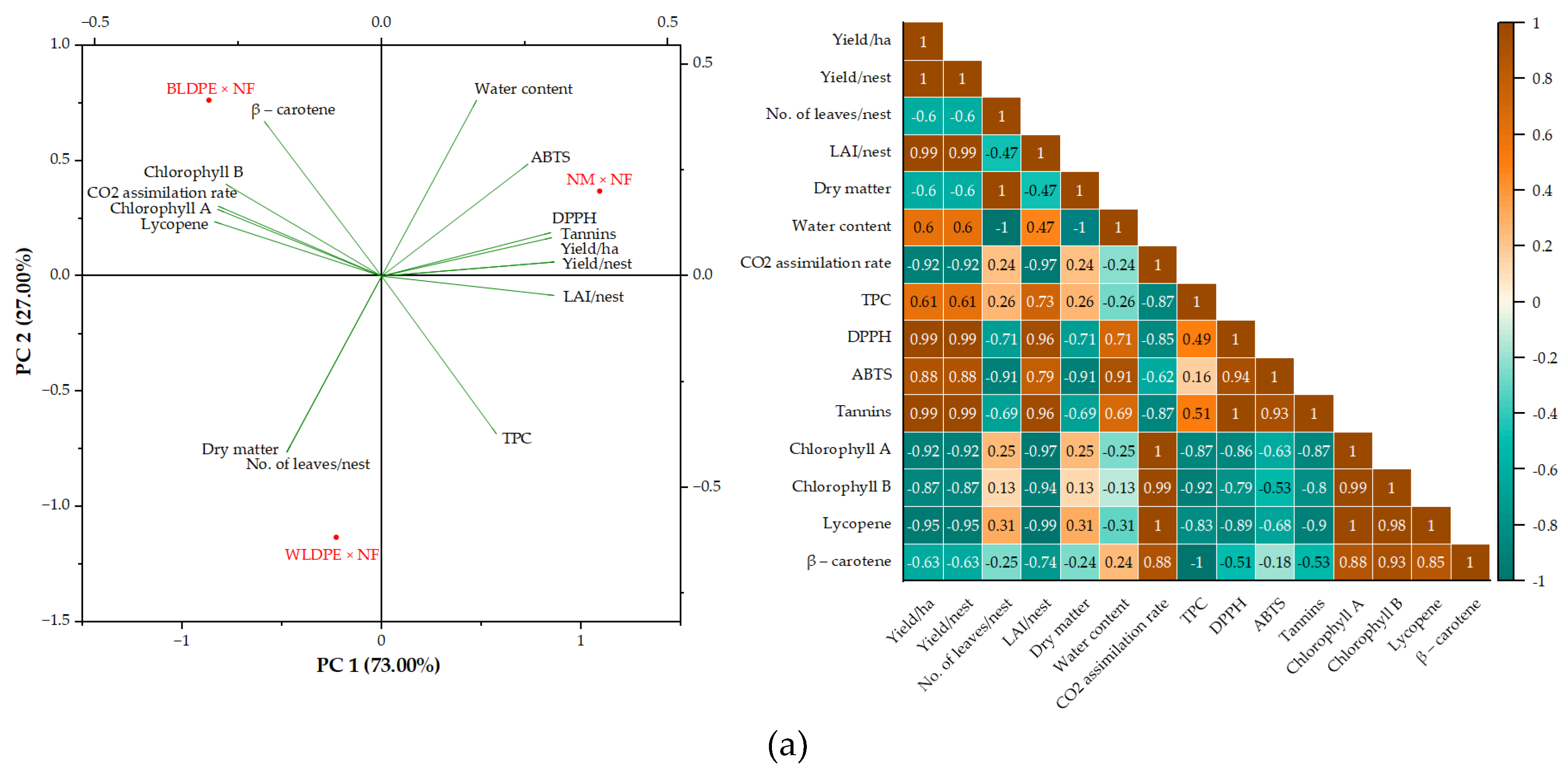

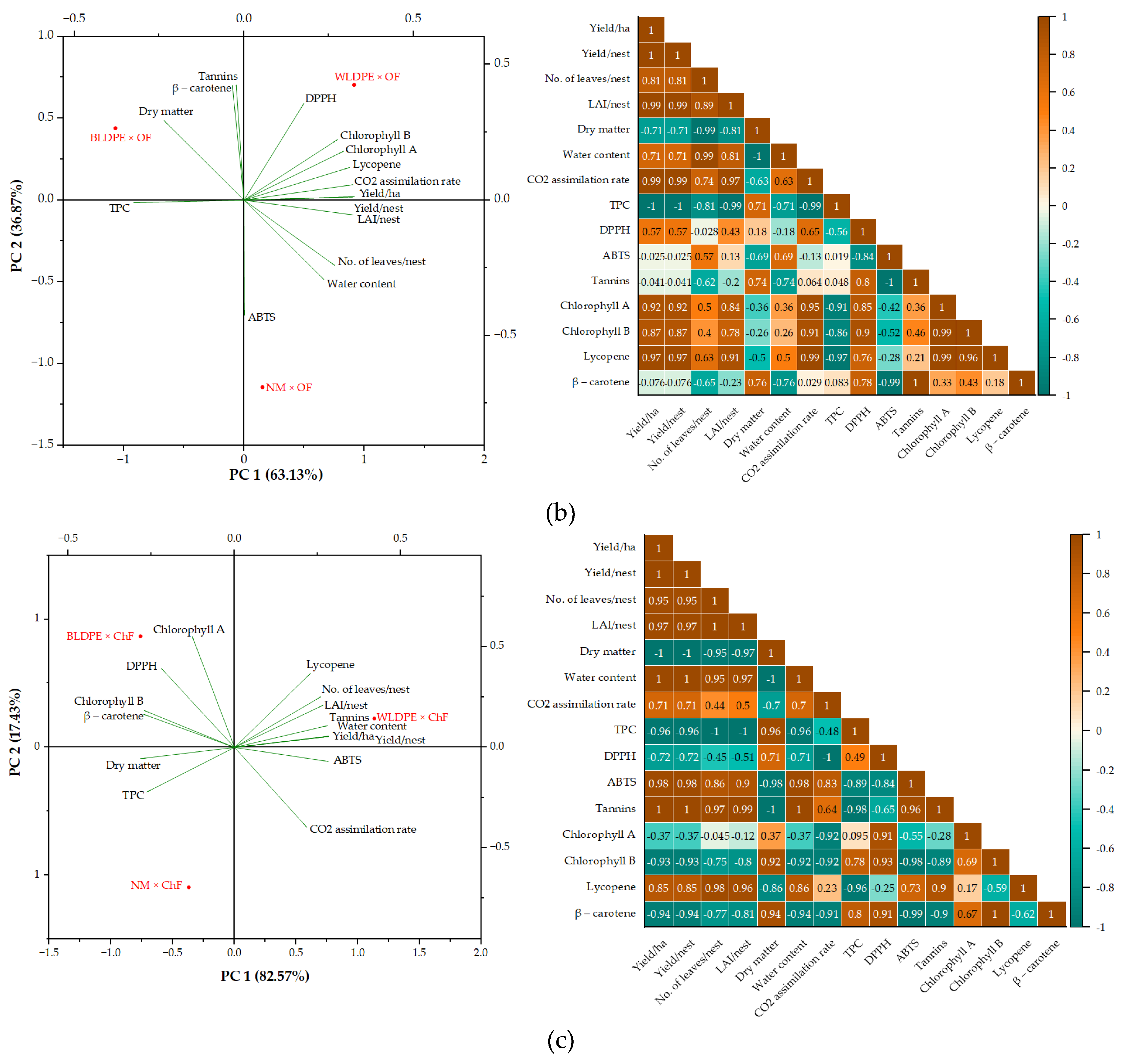

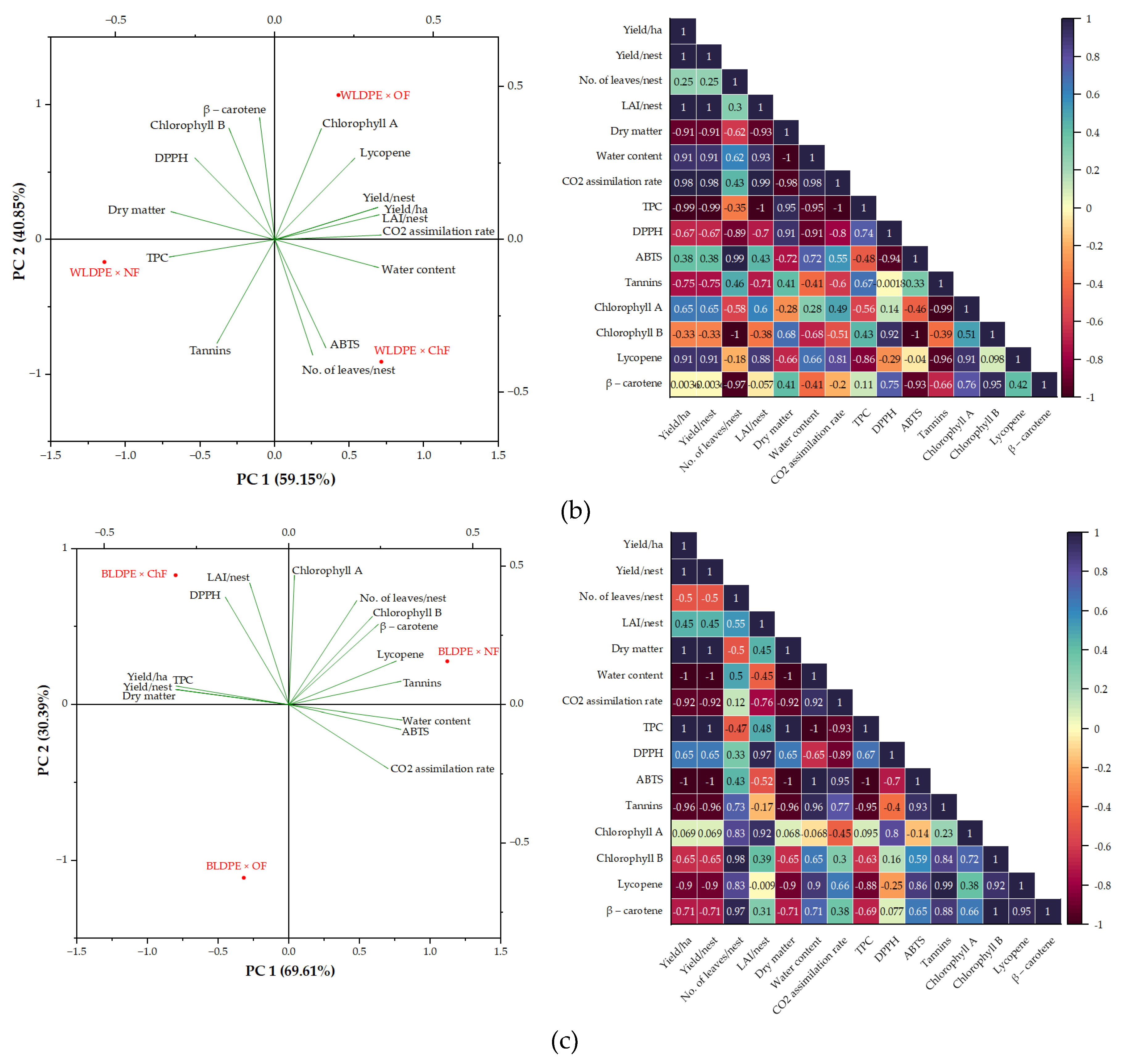

2.3. Dimensionality Reduction and Exploratory Causal Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

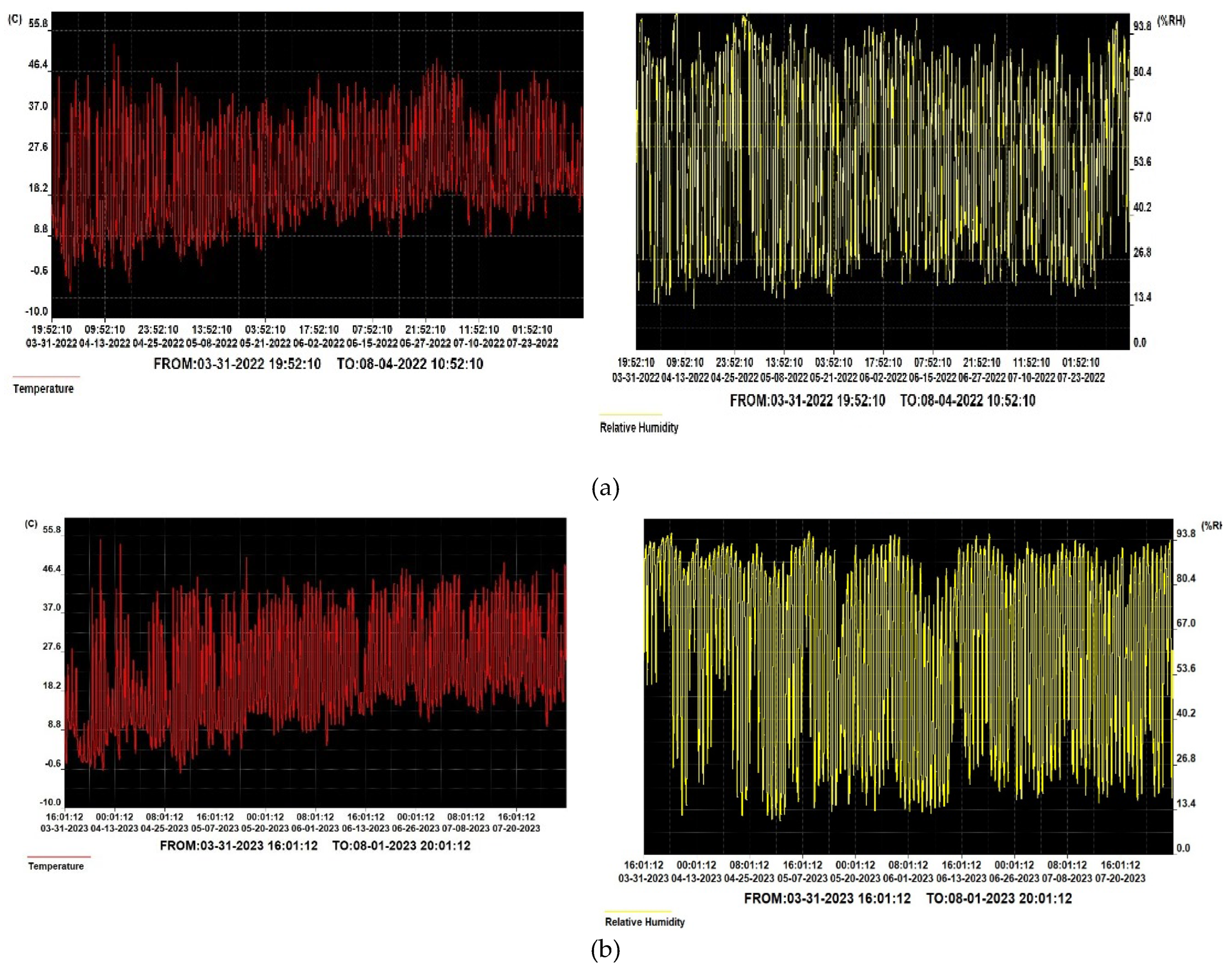

4.1. Design of the Experiment and Research Protocol

4.2. Analytical Methods for the Evaluation of Analysed Parameters

4.3. Statistical Analysis of the Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ressurreição, S.; Salgueiro, L.; Figueirinha, A. Diplotaxis Genus: A Promising Source of Compounds with Nutritional and Biological Properties. Molecules 2024, 29, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonasia, A.; Lazzizera, C.; Elia, A.; Conversa, G. Nutritional, biophysical and physiological characteristics of wild rocket genotypes as affected by soilless cultivation system, salinity level of nutrient solution and growing period. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signore, A.; Amoruso, F.; Gallegos-Cedillo, V.M.; Gómez, P.A.; Ochoa, J.; Egea-Gilabert, C.; Costa-Pérez, A.; Domínguez-Perles, R.; Moreno, D.A.; Pascual, J.A.; et al. Agro-Industrial compost in soilless cultivation modulates the vitamin C content and phytochemical markers of plant stress in rocket salad (Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallarita, A.V.; Golubkina, N.; De Pascale, S.; Sękara, A.; Pokluda, R.; Murariu, O.C.; Cozzolino, E.; Cenvinzo, V.; Caruso, G. Effects of selenium/iodine foliar application and seasonal conditions on yield and quality of perennial wall rocket. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roșca, M.; Mihalache, G.; Teliban, G.C.; Butnariu, M.; Covașa, M.; Cara, I.G.; Rusu, O.R.; Hlihor, R.M.; Ruocco, M.; Stoleru, V. Assessment of perennial wall-rocket (Diplotaxis tenuifolia) growth under Pb(II) stress – Preliminary studies. Acta Hortic. 2025, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Parrella, G.; Giorgini, M.; Nicoletti, R. Crop systems, quality and protection of Diplotaxis tenuifolia. Agriculture 2018, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signore, A.; Renna, M.; Santamaria, P. Agrobiodiversity of Vegetable Crops: Aspect, Needs, and Future Perspectives. In Annual Plant Reviews online; Roberts, J.A., Ed.; Wiley, 2019; pp. 41–64 ISBN 978-1-119-31299-4.

- Troiano, S.; Novelli, V.; Geatti, P.; Marangon, F.; Ceccon, L. Assessment of the sustainability of wild rocket (Diplotaxis tenuifolia) production: application of a multi-criteria method to different farming systems in the province of Udine. Ecological Indicators 2019, 97, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojković-Sebić, A.; Miladinović, V.; Stajković-Srbinović, O.; Pivić, R. Response of arugula to integrated use of biological, inorganic, and organic fertilization. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.K.D.; Jobling, J.J.; Rogers, G.S. Fundamental differences between perennial wall rocket and annual garden rocket influence the commercial year-round supply of these crops. JAS 2015, 7, p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.M.; Pereira, R.J.; Coelho, P.S.; Leitão, J.M. Assessment of wild rocket (Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC.) Germplasm accessions by NGS identified SSR and SNP markers. Plants 2022, 11, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajnko, D.; Berk, P.; Orgulan, A.; Gomboc, M.; Kelc, D.; Rakun, J. Growth and glucosinolate profiles of Eruca sativa (Mill.) (rocket salad) and Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC. under different LED lighting regimes. Plant Soil Environ. 2022, 68, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro-Real, C.; Adalid-Martínez, A.M.; Aguirre, K.; Prohens, J.; Rodríguez-Burruezo, A.; Fita, A. Growing conditions affect the phytochemical composition of edible wall rocket (Diplotaxis erucoides). Agronomy 2019, 9, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Basit, A.; Mohamed, H.I.; Ali, I.; Ullah, S.; Kamel, E.A.R.; Shalaby, T.A.; Ramadan, K.M.A.; Alkhateeb, A.A.; Ghazzawy, H.S. Mulching as a sustainable water and soil saving practice in agriculture: A review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mola, I.; Cozzolino, E.; Ottaiano, L.; Riccardi, R.; Spigno, P.; Petriccione, M.; Fiorentino, N.; Fagnano, M.; Mori, M. Biodegradable mulching film vs. traditional polyethylene: effects on yield and quality of San Marzano tomato fruits. Plants 2023, 12, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; De Pascale, S.; Nicoletti, R.; Cozzolino, E.; Rouphael, Y. Productivity, nutritional and functional qualities of perennial wall-rocket: Effects of pre-harvest factors. Folia Horticulturae 2019, 31, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, W.J. Plastic Mulches for the Production of Vegetable Crops. In A Guide to the Manufacture, Performance, and Potential of Plastics in Agriculture; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 45–60 ISBN 978-0-08-102170-5.

- Stefanelli, D.; Good.w.in, I.; Jones, R. Minimal nitrogen and water use in horticulture: effects on quality and content of selected nutrients. Food Research International 2010, 43, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadeen, A.Y. Effect of polyethylene black plastic mulch on growth and yield of two summer vegetable crops under rain-fed conditions under semi-arid region conditions. American Journal of Agricultural and Biological Sciences 2014, 9, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Wang, Z.; Hui, X.; Huang, T.; Luo, L. Black film mulching can replace transparent film mulching in crop production. Field Crops Research 2021, 261, 108026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, D.; Žanić, K.; Dumičić, G.; Gotlin Čuljak, T.; Goreta Ban, S. The type of polyethylene mulch impacts vegetative growth, yield, and aphid populations in watermelon production. Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment 2009, 7, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Antonious, G. The impact of organic, inorganic fertilizers, and biochar on phytochemicals content of three Brassicaceae vegetables. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayoh, L.N. Destruction of Soil Health and Risk of Food Contamination by Application of Chemical Fertilizer. In Ecological and Practical Applications for Sustainable Agriculture; Bauddh, K., Kumar, S., Singh, R.P., Korstad, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 53–64 ISBN 978-981-15-3372-3.

- Nicoletti, R.; Raimo, F.; G, M. Diplotaxis tenuifolia: Biology, production and properties. European Journal of Plant Science and Biotechnology 2007, 1, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Precupeanu, C.; Munteanu, N.; Caruso, G.; Rădeanu, G.; Teliban, G.C.; Cojocaru, A.; Stan, T.; Popa, L.D.; Stoleru, V. Preliminary studies on biology and harvest technology at Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) D.C. Acta Hortic. 2024, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teliban, G.-C.; Caruso, G.; Munteanu, N.; Cojocaru, A.; Popa, L.-D.; Stoleru, V. Greenhouse perennial wall-rocket crop as influenced by mulching and fertilization practices. Scientific Papers. Series B, Horticulture 2020, LXIV, 474–480.

- Precupeanu, C.; Rădeanu, G.; Teliban, G.C.; Caruso, G.; Stoleru, V. Interaction effect of planting time, mulching and fertilization on perennial wall-rocket. Acta Hortic. 2025, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Stoleru, V.; De Pascale, S.; Cozzolino, E.; Pannico, A.; Giordano, M.; Teliban, G.; Cuciniello, A.; Rouphael, Y. Production, Leaf quality and antioxidants of perennial wall rocket as affected by crop cycle and mulching type. Agronomy 2019, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Lu, J.; Xiang, Y.; Shi, H.; Sun, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F. Farmland mulching and optimized irrigation increase water productivity and seed yield by regulating functional parameters of soybean (Glycine max L.) leaves. Agricultural Water Management 2024, 298, 108875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, R.; Raza, M.A.S.; Valipour, M.; Saleem, M.F.; Zaheer, M.S.; Ahmad, S.; Toleikiene, M.; Haider, I.; Aslam, M.U.; Nazar, M.A. Potential agricultural and environmental benefits of mulches—a review. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2020, 44, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Xing, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Deng, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Li, Z. Chapter Three - The Effects of Mulch and Nitrogen Fertilizer on the Soil Environment of Crop Plants. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; Vol. 153, pp. 121–173.

- Ma, D.; Chen, L.; Qu, H.; Wang, Y.; Misselbrook, T.; Jiang, R. Impacts of plastic film mulching on crop yields, soil water, nitrate, and organic carbon in Northwestern China: A meta-analysis. Agricultural Water Management 2018, 202, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, S.; Mousavi, Z.; Mollaei, S.; Sedaghat, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Pignata, G.; Nicola, S. Optimizing nitrogen fertilization to maximize yield and bioactive compounds in Ziziphora clinopodioides. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, T.-L.; Hu, C.-G.; Zhang, J.-Z. The role of drought and temperature stress in the regulation of flowering time in annuals and perennials. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijten, W.; Koes, R.; Roobeek, I.; Frugis, G. Translating flowering time from Arabidopsis thaliana to Brassicaceae and Asteraceae crop species. Plants 2018, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.R.; Janick, J.; Whipkey, A. Arugula: A Promising Specialty Leaf Vegetable. In Proceedings of the Trends in new crops and new uses Proceedings of the Fifth National Symposium; Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 10-13 November 2001, 2002; pp. 418–423.

- Scarano, A.; Semeraro, T.; Chieppa, M.; Santino, A. Neglected and underutilized plant species (NUS) from the Apulia Region worthy of being rescued and re-included in daily diet. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantis, F.; Kaponas, C.; Charalambous, C.; Koukounaras, A. Strategic successive harvesting of rocket and spinach baby leaves enhanced their quality and production efficiency. Agriculture 2021, 11, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amare, G.; Desta, B. Coloured plastic mulches: impact on soil properties and crop productivity. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 2021, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarara, J.M. Microclimate modification with plastic mulch. HortSci 2000, 35, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheshm, R.; Brown, R.N. The effects of black and white plastic mulch on soil temperature and yield of crisphead lettuce in Southern New England. HortTechnology 2020, 30, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jia, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, N.; Yang, J.; Wang, H. Evaluation of the effects of degradable mulching film on the growth, yield and economic benefit of garlic. Agronomy 2024, 15, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, W.; He, Q. Substitution experiment of biodegradable paper mulching film and white plastic mulching film in Hexi Oasis irrigation area. Coatings 2022, 12, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Formisano, L.; Cozzolino, E.; Pannico, A.; El-Nakhel, C.; Rouphael, Y.; Tallarita, A.; Cenvinzo, V.; De Pascale, S. Shading affects yield, elemental composition and antioxidants of perennial wall rocket crops grown from spring to summer in Southern Italy. Plants 2020, 9, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafziger, E. Soil Temperatures and Fall Ammonia Application. Available online: https://origin.farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2019/10/soil-temperatures-and-fall-ammonia-application.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Horwath, W. 12 - Carbon Cycling and Formation of Soil Organic Matter. In Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry (Third Edition); Paul, E.A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2007; pp. 303–339 ISBN 978-0-12-546807-7.

- Liu, Y.; Lan, X.; Hou, H.; Ji, J.; Liu, X.; Lv, Z. Multifaceted ability of organic fertilizers to improve crop productivity and abiotic stress tolerance: review and perspectives. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz Bento, B.M.; França, A.C.; Oliveira, R.G.; Sardinha, L.T.; Soares Leal, F.D. Organic fertilization attenuates heat stress in lettuce cultivation. Acta Agron. 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoleru, V.; Teliban, G.C.; Cojocaru, A.; Rusu, O.R.; Stan, T.; Gutui, B.; Munteanu, N.; Lobiuc, A. Future perspectives of organic and conventional fertilizers on the morphological and yield parameters of tomato. Acta Hortic. 2025, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriță, R.; Apostol, M.; Teliban, G.C.; Stan, T.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Stoleru, V. Abiotic stress effect on quinoa species (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) under fertilization management. Acta Hortic. 2025, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracchiolla, M.; Renna, M.; D’Imperio, M.; Lasorella, C.; Santamaria, P.; Cazzato, E. Living mulch and organic fertilization to improve weed management, yield and quality of broccoli raab in organic farming. Plants 2020, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A. A review on the effect of organic and chemical fertilizers on plants. IJRASET 2017, V, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Moon, J.-H.; Yang, S.-Y.; Baek, J.-K.; Song, Y.-S.; Shon, J.-Y.; Chung, N.-J.; Lee, H.-S. Effects of mineral fertilization (NPK) on combined high temperature and ozone damage in rice. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Spaccarotella, K.; Gido, J.; Samanta, I.; Chowdhary, G. Effects of heat stress on plant-nutrient relations: an update on nutrient uptake, transport, and assimilation. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Verma, N.; Tewari, R.K. Micronutrient deficiency-induced oxidative stress in plants. Plant Cell Rep 2024, 43, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lynch, J.P.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Q. Chapter 14 - NPK Deficiency Modulates Oxidative Stress in Plants. In Plant Macronutrient Use Efficiency; Hossain, M.A., Kamiya, T., Burritt, D.J., Tran, L.-S.P., Fujiwara, T., Eds.; Academic Press, 2017; pp. 245–265 ISBN 978-0-12-811308-0.

- Hosseini, S.J.; Tahmasebi-Sarvestani, Z.; Pirdashti, H.; Modarres-Sanavy, S.A.M.; Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A.; Hazrati, S.; Nicola, S. Investigation of yield, phytochemical composition, and photosynthetic pigments in different mint ecotypes under salinity stress. Food Science & Nutrition 2021, 9, 2620–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, F.T.; da Silva, D.C.; Yassunaka-Hata, N.N.; de Queiroz Cancian, M.A.; Sanches, I.A.; Poças, C.E.P.; Ventura, M.U.; Spinosa, W.A.; Macedo, R.B. Leafy vegetables’ agronomic variables, nitrate, and bioactive compounds have different responses to Bokashi, mineral fertilization, and boiled chicken manure. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanian, Z.; Habibi, K.; Dehghanian, M.; Aliyar, S.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Astatkie, T.; Minkina, T.; Keswani, C. Reinforcing the bulwark: unravelling the efficient applications of plant phenolics and tannins against environmental stresses. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troszyńska, A.; Narolewska, O.; Wołejszo, A. Extracts from selected tannin-rich foods – a relation between tannins content and sensory astringency. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2007, 57, 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, S.; Brandão, E.; Guerreiro, C.; Soares, S.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Tannins in food: insights into the molecular perception of astringency and bitter taste. Molecules 2020, 25, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, M.A. Tannins in foods: nutritional implications and processing effects of hydrothermal techniques on underutilized hard-to-cook legume seeds–a review. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2022, 27, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimler, D.; Vignolini, P.; Dini, M.G.; Vincieri, F.F.; Romani, A. Antiradical activity and polyphenol composition of local Brassicaceae edible varieties. Food Chemistry 2006, 99, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah Jahan, M.; Sarkar, D.Md.; Chakraborty, R.; Muhammad Solaiman, A.H.; Akter, A.; Shu, S.; Guo, S. Impacts of plastic filming on growth environment, yield parameters and quality attributes of lettuce. Not Sci Biol 2018, 10, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikyo, B.; Enenche, D.; Omotosho, S.; Ofeozo, M.; Rotimi, T. Spectroscopic analysis of the effect of organic and inorganic fertilizers on the chlorophylls pigment in Amaranth and Jute Mallow vegetables. Nig Ann pure App Sci 2020, 3, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Lu, H.; Lu, Y.; Gao, P.; Peng, F. Replacing 30 % chemical fertilizer with organic fertilizer increases the fertilizer efficiency, yield and quality of cabbage in intensive open-field production. Cienc. Rural 2022, 52, e20210186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoleru, V.; Inculet, S.-C.; Mihalache, G.; Cojocaru, A.; Teliban, G.-C.; Caruso, G. Yield and nutritional response of greenhouse grown tomato cultivars to sustainable fertilization and irrigation management. Plants 2020, 9, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiattone, M.I.; Leoni, B.; Cantore, V.; Todorovic, M.; Perniola, M.; Candido, V. Effects of irrigation regime, leaf biostimulant application and nitrogen rate on gas exchange parameters of wild rocket. Acta Hortic. 2018, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Azzini, E.; Lazzè, M.; Raguzzini, A.; Pizzala, R.; Maiani, G. Italian wild rocket [Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC.]: Influence of agricultural practices on antioxidant molecules and on cytotoxicity and antiproliferative effects. Agriculture 2013, 3, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, F.J.; Pradas, I.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.J.; Arroyo, F.T.; Perez-Romero, L.F.; Montenegro, J.C.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Effect of organic and conventional management on bio-functional quality of thirteen plum cultivars (Prunus salicina Lindl.). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slinkard, K.; Singleton, V.L. Total phenol analysis: automation and comparison with manual methods. Am J Enol Vitic. 1977, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, M.; Yamashita, I. Simple method for simultaneous determination of chlorophyll and carotenoids in tomato fruit. J. Japan. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 1992, 39, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, A.; Carbune, R.-V.; Teliban, G.-C.; Stan, T.; Mihalache, G.; Rosca, M.; Rusu, O.-R.; Butnariu, M.; Stoleru, V. Physiological, morphological and chemical changes in pea seeds under different storage conditions. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 28191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.R. de; Cargnelutti Filho, A.; Toebe, M.; Bittencourt, K.C. Sample size and genetic divergence: a principal component analysis for soybean traits. European Journal of Agronomy 2023, 149, 126903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhawary, S.M.A.; Ordóñez-Díaz, J.L.; Nicolaie, F.; Montenegro, J.C.; Teliban, G.-C.; Cojocaru, A.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M.; Stoleru, V. Quality responses of sweet pepper varieties under irrigation and fertilization regimes. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagno, S.; Sadras, V.O.; Haegele, J.W.; Armstrong, P.R.; Ciampitti, I.A. Interplay between nitrogen fertilizer and biological nitrogen fixation in soybean: implications on seed yield and biomass allocation. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 17502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental variant |

Leaves/nest | LAI (cm2·cm−2) |

Total Yield | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nest (g) | t·ha−1 | |||

| WLDPE | 660.67 ± 24.20 | 11309.75 ± 416.52 a | 633.31 ± 25.22 a | 56.36 ± 2.24 a |

| BLDPE | 577.33 ± 23.30 | 9481.05 ± 269.29 b | 511.64 ± 11.76 b | 45.54 ± 1.05 b |

| NM | 634.00 ± 27.05 | 10895.45 ± 505.19 ab | 601.38 ± 42.59 ab | 53.52 ± 3.79 ab |

| Signification | ns | * | * | * |

| OF | 636.44 ± 17.77 | 11027.83 ± 330.97 | 627.24 ± 18.42 | 55.82 ± 1.64 |

| ChF | 591.67 ± 13.83 | 10090.26 ± 562.68 | 540.61 ± 39.11 | 48.11 ± 3.48 |

| NF | 643.89 ± 39.86 | 10568.16 ± 422.30 | 578.47 ± 19.98 | 51.48 ± 1.78 |

| Signification | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Experimental variant | Water content (%) |

Dry matter (%) |

TPC (mg GAE·100 g−1 d.w.) |

Tannins (mmol·100 g−1 d.w.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLDPE | 91.71 ± 0.07 a | 8.29 ± 0.07 b | 1.95 ± 0.11 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| BLDPE | 91.05 ± 0.09 b | 8.95 ± 0.09 a | 1.98 ± 0.15 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| NM | 91.41 ± 0.11 ab | 8.59 ± 0.11 b | 2.04 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| Signification | * | * | ns | ns |

| OF | 91.49 ± 0.07 | 8.51 ± 0.07 | 1.91 ± 0.12 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| ChF | 91.21 ± 0.08 | 8.79 ± 0.08 | 1.99 ± 0.13 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| NF | 91.47 ± 0.12 | 8.53 ± 0.12 | 2.07 ± 0.10 | 0.06 ± 0.00 |

| Signification | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Experimental variant | Chlorophyll A (mg·100 g−1 d.w.) |

Chlorophyll B (mg·100 g−1 d.w.) |

Lycopene (mg·100 g−1 d.w.) |

β-carotene (mg·100 g−1 d.w.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLDPE | 93.14 ± 1.97 | 36.00 ± 0.33 | 9.76 ± 0.21 | 4.77 ± 0.05 b |

| BLDPE | 93.45 ± 0.82 | 39.12 ± 0.83 | 9.40 ± 0.19 | 5.99 ± 0.23 a |

| NM | 87.24 ± 2.86 | 35.70 ± 1.18 | 9.17 ± 0.27 | 4.6 ± 0.26 b |

| Signification | ns | ns | ns | * |

| OF | 94.92 ± 0.15 | 37.05 ± 0.18 | 9.73 ± 0.05 | 5.03 ± 0.29 |

| ChF | 91.21 ± 2.25 | 35.81 ± 1.04 | 9.29 ± 0.19 | 4.91 ± 0.20 |

| NF | 89.25 ± 1.17 | 38.18 ± 1.02 | 9.41 ± 0.22 | 5.36 ± 0.01 |

| Signification | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Experimental variant |

Leaves/nest | LAI (cm2·cm−2) |

TOTAL YIELD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nest (g) | t·ha−1 | |||

| WLDPE × OF | 655.00 ± 27.75 a | 11328.77 ± 196.48 ab | 656.78 ± 10.13 ab | 58.45 ± 0.90 ab |

| WLDPE × ChF | 670.67 ± 36.55 a | 11556.13 ± 1245.31 ab | 650.73 ± 83.00 a−c | 57.91 ± 7.39 a−c |

| WLDPE × NF | 656.33 ± 28.85 a | 11044.36 ± 265.19 ab | 592.42 ± 9.34 a−d | 52.73 ± 0.83 a−d |

| BLDPE × OF | 591.00 ± 20.07 ab | 9715.37 ± 443.82 bc | 537.68 ± 23.29 b−d | 47.85 ± 2.07 b−d |

| BLDPE × ChF | 519.67 ± 35.03 b | 8842.67 ± 450.49 c | 457.10 ± 22.34 d | 40.68 ± 1.99 d |

| BLDPE × NF | 621.33 ± 29.49 ab | 9885.11 ± 513.22 a−c | 540.12 ± 22.92 b−d | 48.07 ± 2.04 b−d |

| NM × OF | 663.33 ± 31.17 a | 12039.34 ± 970.78 a | 687.26 ± 66.15 a | 61.17 ± 5.89 a |

| NM × ChF | 584.67 ± 15.07 ab | 9871.99 ± 325.64 a−c | 514.01 ± 28.82 cd | 45.75 ± 2.56 cd |

| NM × NF | 654.00 ± 66.30 a | 10775.01 ± 681.02 a−c | 602.87 ± 41.90 a−c | 53.66 ± 3.73 a−c |

| Experimental variant | Water content (%) |

Dry matter (%) |

TPC (mg GAE·100 g−1 d.w.) |

Tannins (mmol·100 g−1 d.w.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLDPE × OF | 91.79 ± 0.01 ab | 8.21 ± 0.01 cd | 1.84 ± 0.12 | 0.06 ± 0.01 a−c |

| WLDPE × ChF | 91.95 ± 0.10 a | 8.05 ± 0.10 d | 1.84 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 a−c |

| WLDPE × NF | 91.39 ± 0.29 bc | 8.61 ± 0.29 bc | 2.17 ± 0.19 | 0.06 ± 0.00 ab |

| BLDPE × OF | 91.09 ± 0.20 cd | 8.91 ± 0.20 ab | 1.99 ± 0.17 | 0.06 ± 0.01 a−c |

| BLDPE × ChF | 90.73 ± 0.08 d | 9.27 ± 0.08 a | 2.05 ± 0.17 | 0.05 ± 0.00 bc |

| BLDPE × NF | 91.35 ± 0.03 bc | 8.65 ± 0.03 bc | 1.90 ± 0.12 | 0.06 ± 0.00 ab |

| NM × OF | 91.60 ± 0.01 ab | 8.40 ± 0.01 cd | 1.90 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.01 c |

| NM × ChF | 90.96 ± 0.24 cd | 9.04 ± 0.24 ab | 2.10 ± 0.20 | 0.06 ± 0.01 a−c |

| NM × NF | 91.67 ± 0.10 ab | 8.33 ± 0.10 cd | 2.14 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 a |

| Signification | * | * | ns | * |

| Experimental variant | Chlorophyll A (mg·100 g−1 d.w.) | Chlorophyll B (mg·100 g−1 d.w.) |

Lycopene (mg·100 g−1 d.w.) |

β-carotene (mg·100 g−1 d.w.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLDPE × OF | 101.45 ± 3.74 a | 38.47 ± 0.90 ab | 10.16 ± 0.36 a | 5.74 ± 0.31 a−c |

| WLDPE × ChF | 89.51 ± 1.15 b−d | 32.47 ± 0.08 c | 9.73 ± 0.16 ab | 3.80 ± 0.07 d |

| WLDPE × NF | 88.45 ± 1.00 b−d | 37.07 ± 0.01 b | 9.38 ± 0.10 ab | 4.77 ± 0.09 cd |

| BLDPE × OF | 87.79 ± 2.33 b−d | 35.87 ± 0.29 bc | 9.19 ± 0.07 ab | 5.68 ± 0.55 a−c |

| BLDPE × ChF | 97.45 ± 5.17 ab | 39.05 ± 2.16 ab | 9.25 ± 0.51 ab | 5.96 ± 0.19 ab |

| BLDPE × NF | 95.13 ± 0.38 a−c | 42.45 ± 0.62 a | 9.78 ± 0.14 ab | 6.35 ± 0.33 a |

| NM × OF | 90.88 ± 0.95 b−d | 36.16 ± 0.02 bc | 9.54 ± 0.01 ab | 3.86 ± 0.19 d |

| NM × ChF | 86.69 ± 2.73 cd | 35.91 ± 1.06 bc | 8.89 ± 0.23 b | 4.98 ± 0.34 bc |

| NM × NF | 84.16 ± 4.89 d | 35.03 ± 2.45 bc | 9.07 ± 0.61 ab | 4.95 ± 0.25 bc |

| Traits | Extracted Eigenvectors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | PC7 | PC8 | |

| Yield/ha | 0.341 | 0.007 | 0.134 | −0.321 | −0.157 | 0.196 | 0.128 | 0.134 |

| Yield/nest | 0.341 | 0.007 | 0.134 | −0.321 | −0.157 | 0.196 | 0.128 | 0.134 |

| No. of leaves/nest | 0.279 | −0.083 | 0.148 | 0.149 | 0.763 | −0.165 | −0.176 | 0.072 |

| LAI/nest | 0.346 | 0.054 | 0.158 | −0.303 | 0.033 | −0.029 | 0.078 | 0.146 |

| Dry matter | −0.330 | 0.106 | −0.112 | −0.320 | 0.278 | 0.130 | −0.170 | 0.163 |

| Water content | 0.330 | −0.106 | 0.112 | 0.320 | −0.278 | −0.130 | 0.170 | −0.163 |

| CO2 assimilation rate | 0.201 | 0.245 | −0.407 | 0.242 | 0.016 | 0.384 | −0.016 | 0.584 |

| TPC | −0.279 | −0.306 | 0.080 | −0.093 | 0.156 | 0.003 | 0.706 | 0.166 |

| DPPH | −0.167 | −0.154 | 0.576 | −0.137 | −0.139 | −0.181 | −0.258 | 0.315 |

| ABTS | 0.241 | −0.349 | −0.048 | 0.276 | −0.146 | −0.280 | −0.255 | 0.274 |

| Tannins | −0.047 | −0.261 | 0.439 | 0.319 | 0.154 | 0.640 | −0.028 | 0.038 |

| Chlorophyll A | 0.058 | 0.476 | 0.257 | −0.158 | 0.073 | −0.185 | −0.104 | 0.099 |

| Chlorophyll B | −0.154 | 0.385 | 0.189 | 0.360 | −0.021 | −0.301 | 0.374 | 0.390 |

| Lycopene | 0.254 | 0.348 | 0.171 | 0.129 | 0.217 | 0.084 | 0.213 | −0.413 |

| β — carotene | −0.234 | 0.324 | 0.249 | 0.199 | −0.267 | 0.248 | −0.213 | −0.093 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).