1. Introduction

Sustainable forage production is a cornerstone of organic livestock systems, where reliance on synthetic inputs is restricted and ecological interactions are leveraged to maintain productivity. In this context, grassland and forage-based systems serve not only as feed resources but also as multifunctional components of agroecosystems, contributing to soil health, biodiversity, and weed suppression. Among the strategies compatible with organic agriculture, mixed cropping of forage legumes and grasses has gained attention due to its potential to enhance yield and quality while naturally suppressing weed populations and improving soil fertility (Mugwe et al., 2019; Tahir et al., 2022).

Narbon vetch (Vicia narbonensis L.), a hardy annual legume adapted to Mediterranean climates, is recognized for its drought tolerance, high protein content, and nitrogen-fixing capacity, making it especially valuable under input-limited organic systems (Kusvuran et al., 2019). It improves soil fertility through biological nitrogen fixation and contributes to balanced rations in ruminant diets. Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum L.), on the other hand, is a cool-season grass known for its rapid establishment, high dry matter production, and palatability. Its fibrous root system plays a vital role in soil structure improvement and erosion control, which aligns with the soil conservation principles of organic farming (Yin et al., 2020).

The synergistic interaction between legumes and grasses in mixed stands can be particularly beneficial in organic systems. Legumes supply biologically fixed nitrogen to companion grasses, reducing reliance on external N inputs, while grasses contribute structural biomass and facilitate canopy closure, which collectively enhance resource-use efficiency and forage quality (Wang et al., 2023). Moreover, increased ground cover and spatial niche occupation in such mixtures are associated with improved weed suppression — a critical component of organic production, where chemical herbicides are prohibited (Tahir et al., 2022; Lal et al., 2021). Recent studies have shown that mixed swards can outperform monocultures not only in forage yield and nutritive value but also in their ability to reduce weed biomass and density, especially during early canopy development stages (Hauggaard-Nielsen et al., 2019; Bavec et al., 2020).

Despite these benefits, the performance of specific legume–grass combinations under different ecological conditions and organic management regimes remains underexplored. In particular, there is limited data regarding the use of Narbon vetch and Italian ryegrass mixtures under organic farming systems in Mediterranean climates, such as those in Bilecik, Turkey. Given the region’s cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers, optimizing forage mixtures for both productivity and ecological service delivery (e.g., weed control) is essential.

This study aims to evaluate the effects of different seed mixture ratios of Narbon vetch (cvs. Özgen, Karakaya, and IFVN 567) and Italian ryegrass (cvs. Trinova, Bartigra, and Efe 82) on forage yield, quality traits, and weed suppression capacity under organic farming conditions in Bilecik. The results are expected to provide practical recommendations for sustainable forage production in organic systems, supporting both agronomic performance and ecological sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted during the 2020–2021 growing season under the ecological conditions of Bilecik province, Turkey, in the experimental plots of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Technologies at Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University. Narbon vetch (Vicia narbonensis L.) and Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum L.) were sown both as sole crops and in mixed proportions (100%, 75:25, 50:50, and 25:75). Sowing was performed manually in November. No fertilizers or chemical pesticides were applied; only standard cultural practices were carried out. Harvesting took place in May at the full flowering stage. Measurements on yield, forage quality, and weed suppression were obtained from harvested samples.

The plant material used in the experiment included three Narbon vetch genotypes Özgen, Karakaya, and IFVN 567sourced from the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture’s Variety Registration and Certification Center and the GAP Agricultural Research Institute. Additionally, three Italian ryegrass cultivars Trinova, Bartigra, and Efe 82 were included. Özgen and Karakaya were developed and registered by Dicle University through selection breeding. Trinova is a high-quality forage crop known for its digestibility, silage value, and high protein content. Bartigra is a tetraploid annual ryegrass, and Efe 82 was developed by the Aegean Agricultural Research Institute.

2.1. Climatic Data

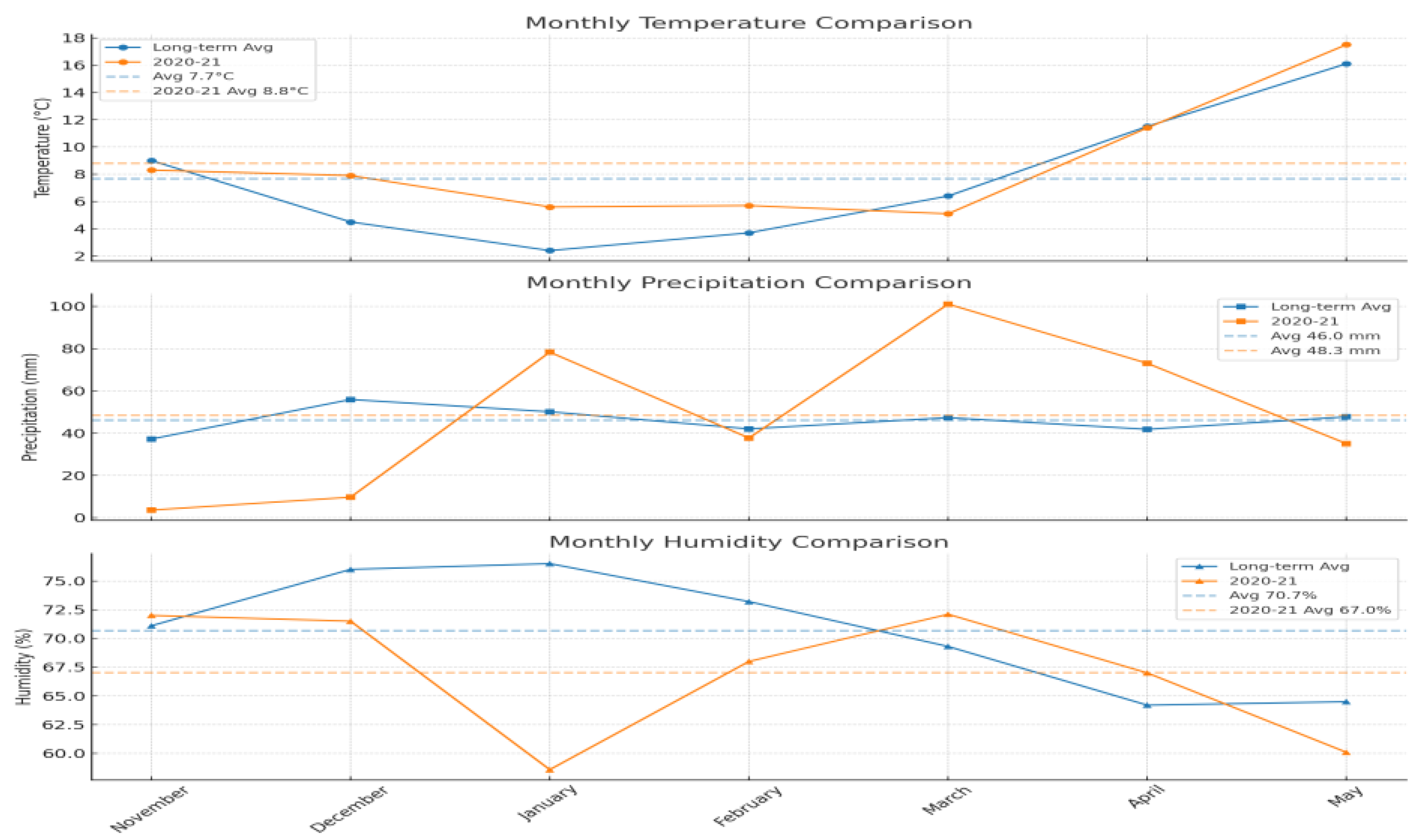

Climatic data for the 2020–2021 growing season were obtained from the Bilecik Meteorological Directorate. The average temperature during the trial period was 8.8 °C, which is higher than the long-term average of 7.7 °C. Relative humidity averaged 67.0% in 2020–2021, compared to a long-term mean of 70.7%. The total annual precipitation was recorded as 338.3 mm in the study year, slightly above the long-term average of 322.0 mm (

Figure 1).

2.2. Experimental Design and Field Management

Prior to sowing, the field was prepared by conventional tillage in the autumn. A compound fertilizer (20-20-0) was applied at a rate of 4 kg N and 4 kg P₂O₅ per decare as a basal dressing. The soil was subsequently cultivated using a rotary tiller. Sowing was performed manually on October 14, 2020, into seedbeds marked using a row marker.

The experiment was established using a randomized complete block design (RCBD) in a factorial arrangement with three replications. Each plot consisted of six rows, spaced 30 cm apart, with a row length of 4 meters, resulting in a total plot area of 7.2 m² (1.8 m × 4.0 m). A 1-meter buffer was left between plots, and 2-meter spacing was maintained between replication blocks to prevent edge effects.

Picture 1.

Field preparation and sowing operations.

Picture 1.

Field preparation and sowing operations.

2.2.1. Plant Material and Sowing Rates

The plant materials used in the study included Narbon vetch (Vicia narbonensis) and Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum). Sowing rates were as follows:

A total of 15 treatments were evaluated in the study, consisting of 9 mixed cropping combinations and 6 monoculture applications.

2.2.2. Experimental Site and Soil Characteristics

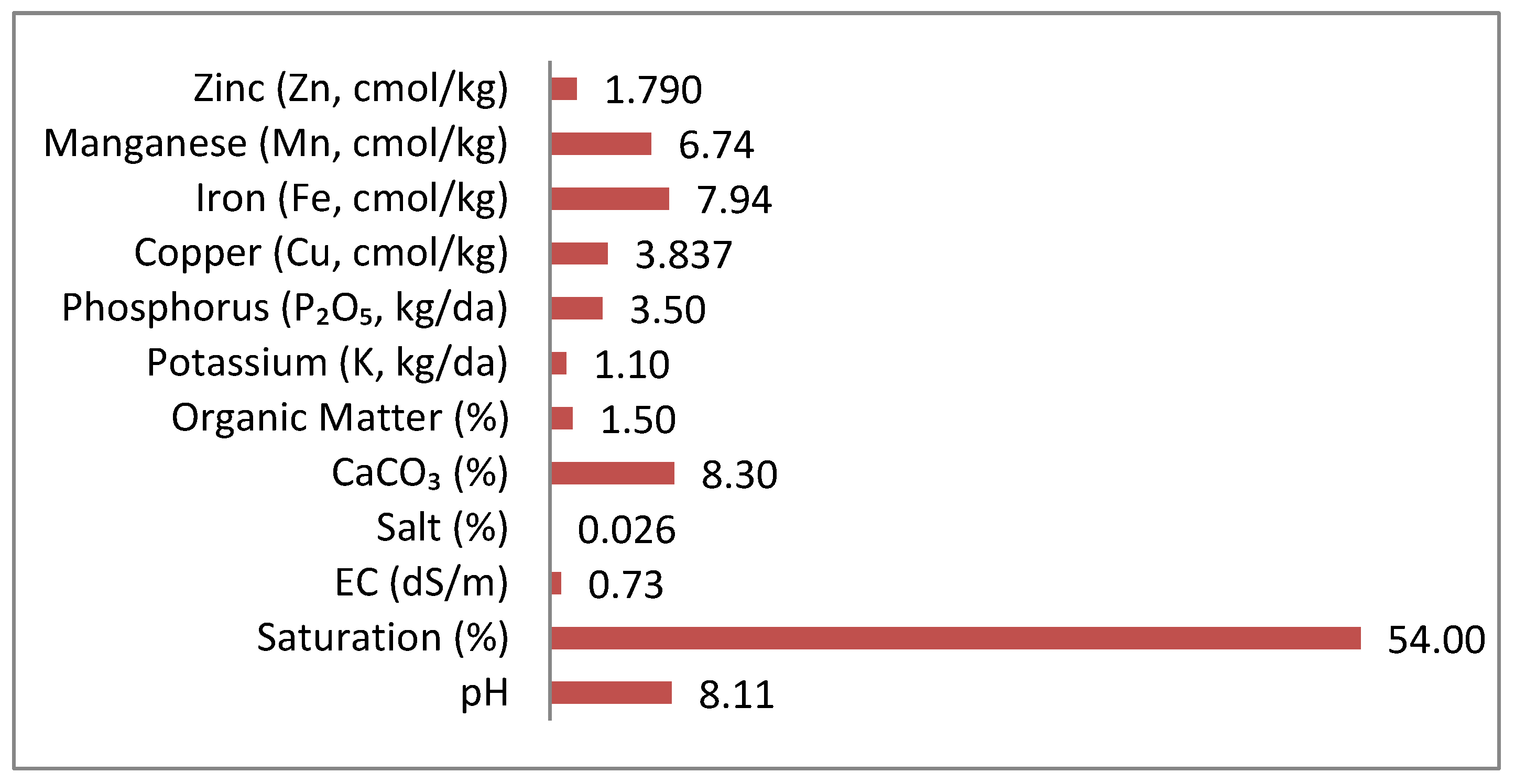

This study was conducted at the Research and Application Area of the Faculty of Agriculture, Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University, Turkey, during the 2020–2021 growing season. The soil of the experimental site was classified as sandy-loam in texture. According to pre-sowing soil analyses, the field exhibited

moderate levels of lime (CaCO₃) and organic matter, while

available phosphorus (P₂O₅) and potassium (K) contents were considered

low (

Figure 2.)

2.3. Measurements and Harvesting

The harvest was conducted based on the dominant species in the mixed cropping systems, which was the grass component. Specifically, harvesting was carried out at the beginning of heading in Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum). Observations related to morphological characteristics of both grass and legume species were performed according to the methods described by Tansı (1987). Just before harvesting, ten plants were randomly selected from both sole cropped plots and mixed plots. In these selected plants, plant height, stem diameter, number of tillers, number of lateral branches, leaf width, and leaf length were recorded. In addition, leaf-to-stem ratio and botanical composition of the mixtures were determined.

After eliminating the border effect, herbage was harvested and green herbage yield was calculated. Subsamples of green herbage were taken during harvest and oven-dried at 70 °C for 48 hours to determine dry matter yield, following the procedures of Tansı (1987). The dried plant materials were ground and analyzed for crude protein, acid detergent fiber (ADF; cellulose + lignin), and neutral detergent fiber (NDF; hemicellulose + cellulose + lignin). Crude protein yield was calculated by multiplying dry matter yield by crude protein percentage.

2.3.1. Land Equivalent Ratio (LER)

To assess land use efficiency, the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) was calculated for mixed cropping plots. LER is defined as the relative land area required under sole cropping to achieve the same yield as that obtained from intercropping. It was calculated using the following formula described by Tansı (1987):

LER = (Yield of grass in intercropping / Yield of grass in sole cropping) + (Yield of legume in intercropping / Yield of legume in sole cropping)

The interpretation of LER values is as follows:

-LER > 1: Indicates that the intercropping system improves land use efficiency.

-LER = 1: Indicates that the intercropping system has no effect on land use efficiency.

-LER < 1: Indicates that the intercropping system reduces land use efficiency.

2.3.2. Assessment of Weed Suppression

Weed data were collected twice during the growing season. In each plot, two 50 × 50 cm quadrats were randomly placed to assess weed cover. Aboveground weed biomass within each quadrat was harvested to determine weed cover area, fresh weight, and dry weight. Fresh weights were recorded immediately after harvest, and samples were then oven-dried at 70 °C for 48 hours to obtain dry weights.

The effects of treatments on weed parameters (cover, fresh weight, and dry weight) were statistically evaluated using SPSS 22 software. A General Linear Model (GLM) was applied, followed by Tukey’s HSD test for mean comparisons at the 5% significance level.

Picture 2.

Weed suppression and sample collection methods.

Picture 2.

Weed suppression and sample collection methods.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using a randomized complete block design (RCBD). Statistical analyses were conducted using JMP Pro 16 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for each trait. When significant differences were detected, treatment means were compared using Tukey’s multiple comparison test at a 5% significance level. Graphical illustrations were created using Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Characteristics

Morphological traits of Narbon vetch and Italian ryegrass cultivars under organic sole and mixed cropping are given (

Table 1). Plant height (cm), stem diameter (mm), leaf length and width (cm), and branching parameters (number of lateral branches for vetch; number of tillers for ryegrass) are shown for each cultivar and cropping system. Values are means (±SE) of replicates. Different letters within each column indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

3.1.1. Plant Height

In terms of plant height, Lolium multiflorum varieties demonstrated a clear advantage over Vicia narbonensis. According to the data, annual ryegrass monocultures reached the highest plant heights, while Narbon vetch monocultures remained comparatively shorter. This trend is consistent with existing literature, which reports that Italian ryegrass can reach 60–90 cm in height, whereas Narbon vetch typically grows to 20–60 cm. Statistical analysis revealed that the difference in plant height between L. multiflorum and V. narbonensis monocultures was significant at p<0.05. In mixed cropping systems, plant heights were generally intermediate between the two species, with some combinations showing statistically significant differences.

3.1.2. Stem Diameter

Narbon vetch exhibited significantly thicker stem diameters compared to ryegrass, which reflects their inherent structural differences. While V. narbonensis develops upright, thick, and branched stems, L. multiflorum has thin, cylindrical, and often hollow stems. The experimental data clearly supports this: the stem diameters of Narbon vetch in both monoculture and mixtures were significantly larger than those of ryegrass (p<0.05). These results are consistent with the known anatomical distinctions between these species.

3.1.3. Leaf Dimensions

Distinct differences were also observed in leaf size. Ryegrass typically has long (6–25 cm) but very narrow leaves (0.3–1 cm), while Narbon vetch has relatively short (2–5 cm) but broader leaflets (1–4 cm). In the experiment, L. multiflorum varieties showed significantly greater leaf lengths, while V. narbonensis had significantly wider leaves (p<0.05). In mixed cropping treatments, leaf measurements tended to reflect intermediate values, but the contribution of each species was evident: length from ryegrass and width from Narbon vetch.

3.1.4. Number of Lateral Branches

Narbon vetch typically produces multiple lateral branches, while annual ryegrass has a single culm and does not branch. The number of lateral branches was substantially higher in V. narbonensis varieties, and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.05). This branching ability of Narbon vetch contributed significantly to its vegetative development, especially in monoculture and mixture plots where it was dominant.

3.1.5. Number of Sprouts (Tillers)

In contrast, ryegrass demonstrated a much greater capacity for tiller formation. L. multiflorum is known for producing numerous tillers per plant, whereas V. narbonensis generally grows from a single main stem with lateral branches rather than tillers. The highest number of tillers was observed in pure ryegrass stands, with values significantly higher than those recorded for Narbon vetch (p<0.05). In mixed stands, treatments including L. multiflorum showed a clear advantage in terms of sprout number, emphasizing its prolific tillering potential.

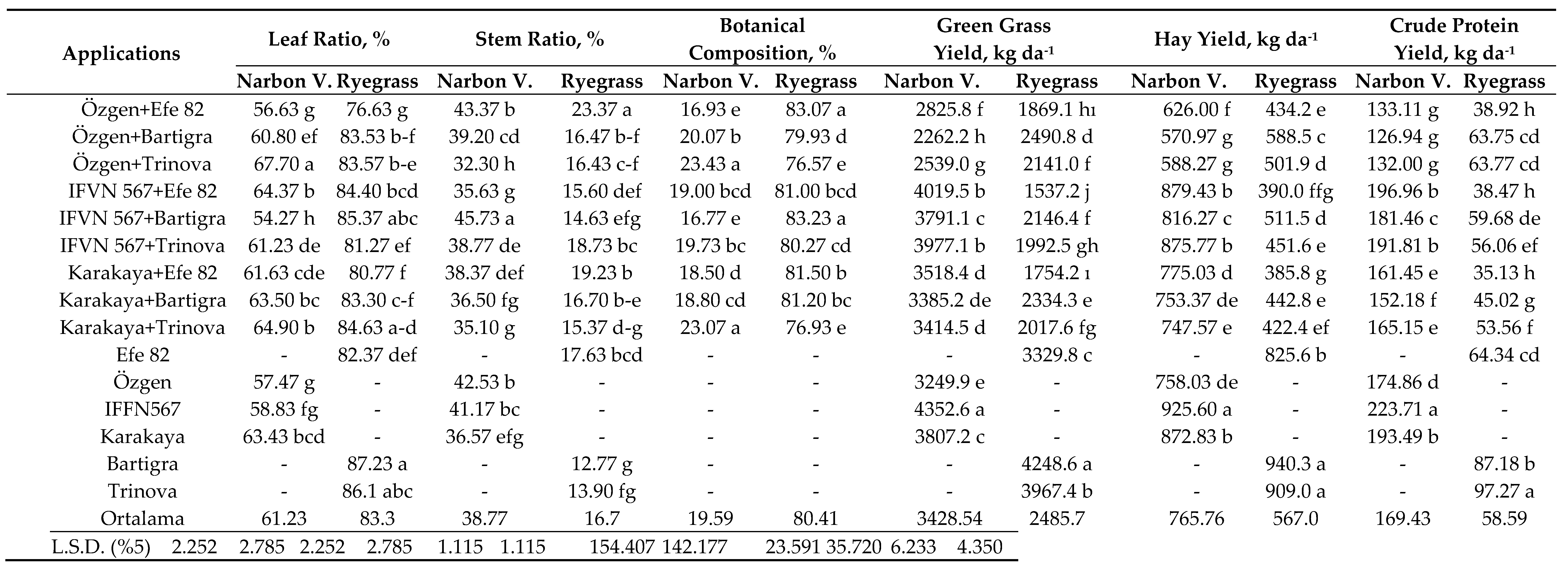

3.2. Leaf-Stem Ratio, Botanical Composition, and Forage Yield Components

Leaf-to-stem ratio, botanical composition, and forage yield parameters (green herbage yield, hay yield, and crude protein yield) of different Narbon vetch (

Vicia narbonensis L.) and annual ryegrass (

Lolium multiflorum L.) combinations cultivated as sole crops and mixtures under organic farming conditions are given (

Table 2) Values are presented as percentages or kg da⁻¹. Different letters within the same column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 (LSD test).

3.2.1. Leaf-Stem Ratio

The results revealed statistically significant differences (p<0.05) in the leaf-stem ratios among treatments. The highest leaf ratio (67.70%) was obtained from the Özgen+Trinova mixture, while the lowest was recorded in the IFVN 567+Bartigra treatment (54.27%). Across the treatments, Narbon vetch contributed more to the leaf ratio than ryegrass. This trend is consistent with the known morphological features of the species, where legumes generally possess broader leaflets and thus exhibit higher leaf proportions. In contrast, ryegrass showed higher stem ratios, likely due to its elongated and narrow leaf structure.

3.2.2. Botanical Composition

The botanical composition showed considerable variability among mixtures. In all combinations, ryegrass dominated the botanical composition, comprising 76.57% to 83.23% of the biomass, whereas the proportion of Narbon vetch ranged from 16.77% to 23.43%. This dominance is attributed to the more aggressive growth habit and competitive ability of ryegrass under the given ecological conditions. Among mixtures, Özgen+Trinova recorded the highest proportion of Narbon vetch (23.43%), indicating better compatibility and balanced growth.

3.2.3. Green Grass Yield

The highest green herbage yield among the mixtures was observed in the IFVN 567+Efe 82 treatment (4019.5 kg da⁻¹), followed by IFVN 567+Trinova and Karakaya+Efe 82. In monocultures, the highest yield was recorded for IFFN 567 (4352.6 kg da⁻¹), while Bartigra had the highest yield among ryegrass monocultures (4248.6 kg da⁻¹). These results emphasize the high biomass potential of both species when grown individually under organic conditions. However, most mixed cropping treatments yielded less green herbage than the best-performing monocultures, reflecting some degree of interspecific competition.

3.2.4. Hay Yield

Hay yields followed a similar trend to green herbage yield. The highest hay yield among mixtures was recorded in IFVN 567+Efe 82 (879.43 kg da⁻¹), while the lowest yield was found in Özgen+Efe 82 (626.00 kg da⁻¹). Among monocultures, Bartigra produced the highest hay yield (940.3 kg da⁻¹), reinforcing the forage production advantage of annual ryegrass. However, certain mixtures such as IFVN 567+Trinova and Karakaya+Trinova still achieved competitive hay yields, indicating the potential of specific combinations under organic systems.

3.2.5. Crude Protein Yield

Crude protein yield, an essential quality indicator of forage, varied significantly among treatments (p<0.05). The highest crude protein yield was recorded in IFFN 567 monoculture (223.71 kg da⁻¹), followed by IFVN 567+Efe 82 and IFVN 567+Trinova. Mixtures with Özgen generally showed the lowest protein yields, particularly Özgen+Efe 82 (133.11 kg da⁻¹). These findings suggest that the genotype of Narbon vetch plays a critical role in determining protein productivity. The high protein content of pure stands of Narbon vetch underlines its value as a legume in forage systems.

The study demonstrates that while monocultures of Narbon vetch and ryegrass can provide superior yields in specific parameters, certain mixtures (e.g., IFVN 567+Trinova, Karakaya+Trinova) offer a balanced compromise between yield and forage quality. The dominance of ryegrass in mixtures underscores its competitive growth, but the inclusion of Narbon vetch contributes positively to crude protein content and botanical diversity. Strategic genotype selection is essential to optimize the productivity and quality of mixed forage systems under organic conditions.

3.3. Crude Protein Content, Fiber Composition, Forage Yield, and Land Equivalent Ratios

Crude protein ratio, fiber contents (ADF and NDF), total forage yields (green and hay), and land equivalent ratios (LER) for dry matter and protein in different combinations of Narbon vetch (

Vicia narbonensis L.) and annual ryegrass (

Lolium multiflorum L.) cultivated as sole crops and mixtures under organic farming conditions are given (

Table 3). Different letters within the same column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 (LSD test).

3.3.1. Crude Protein Content

Significant differences (p<0.05) were observed in crude protein content across different treatments. Among monocultures, Narbon vetch ‘IFFN 567’ had the highest crude protein ratio (24.17%), while the lowest value was found in the ryegrass monoculture ‘Efe 82’ (7.80%). In mixed cropping systems, Özgen+Trinova (22.43%) and IFVN 567+Efe 82 (22.40%) exhibited relatively high protein content in the legume component, while Trinova and Bartigra consistently showed higher protein ratios among ryegrass cultivars. These results highlight the nutritive superiority of Narbon vetch compared to ryegrass, and the contribution of ryegrass genotype to the overall protein balance in mixtures.

3.3.2. Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF) and Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF)

Fiber content, as measured by ADF and NDF, also varied significantly among the treatments. The lowest ADF (27.17%) was observed in the IFFN 567 monoculture, indicating better digestibility. Conversely, the highest ADF (30.47%) was noted in the Karakaya+Bartigra mixture. In terms of NDF, the highest values were recorded in monoculture ryegrass ‘Efe 82’ (47.40%), reflecting its fibrous nature, while the lowest values occurred in mixtures containing Trinova and IFVN 567. These findings show that the inclusion of Narbon vetch can effectively lower the fiber content of the sward, improving forage quality.

3.3.3. Total Green and Hay Yield

Mixtures significantly outperformed monocultures in terms of total green and hay yields. The highest green yield was achieved by IFVN 567+Trinova (5969.6 kg da⁻¹), followed closely by IFVN 567+Bartigra (5937.5 kg da⁻¹), indicating the strong biomass production potential of these combinations. Similarly, the highest hay yield was observed in the same treatments (1327.3 and 1327.8 kg da⁻¹, respectively). Monocultures lagged behind, especially for green yield, indicating the advantage of species complementarity in mixed cropping.

3.3.4. Land Equivalent Ratios (LERs)

The Dry Matter Land Equivalent Ratio (DM-LER) and Protein Land Equivalent Ratio (Protein-LER) values further confirmed the superiority of mixed cropping systems. The highest DM-LER (1.67) and Protein-LER (1.96) values were observed in the IFVN 567+Trinova mixture, demonstrating a clear advantage in land use efficiency and protein productivity over sole cropping. All mixtures had DM-LER and Protein-LER values greater than 1.0, indicating synergistic interactions and resource-use complementarity. In contrast, all monocultures had LER values equal to 1.0, as expected.

The results indicate that mixing Narbon vetch with selected ryegrass cultivars under organic conditions enhances both forage yield and nutritional quality. Among the combinations tested, IFVN 567+Trinova and IFVN 567+Bartigra stood out with their superior performance in yield and land-use efficiency. These findings support the use of strategic species and genotype combinations to optimize organic forage systems, especially when aiming to balance biomass production with high nutritional value.

3.4. Weed Species Composition and Densities

Weed species and their mean densities (plants m⁻²) observed in different Narbon vetch (

Vicia narbonensis L.) and annual ryegrass (

Lolium multiflorum L.) cropping systems under organic farming conditions. “–“ indicates absence of the species in the respective plots

are given (Table 4). Abbreviations for weed species are defined below the table.

The results presented in

Table 4 demonstrate considerable variation in the occurrence and density of weed species among the different cropping systems. A total of 25 weed species were identified across all treatments, with the highest diversity observed in sole cropping systems, particularly in

IFVN 567,

Karakaya, and

Özgen, which exhibited broader weed spectrums and higher densities.

Among the species, Lolium temulentum (LOLTE), Lamium amplexicaule (LAMAP), Raphanus raphanistrum (PAPRH), and Veronica hederifolia (VERHE) were frequently detected in various systems, suggesting their competitive ability and adaptability under organic conditions. Notably, Lolium temulentum reached the highest density (9.00 plants/plot) in the IFVN 567 monoculture, indicating that pure stands may be more prone to specific weed invasions.

Mixed cropping systems generally exhibited lower weed incidences compared to pure stands. For instance, combinations such as Özgen+Bartigra, Karakaya+Bartigra, and Özgen+Efe 82 showed limited weed presence, with most species either absent or present at very low densities (≤1.00 plant/plot). This supports the notion that interspecific competition between forage crops can enhance weed suppression, likely due to improved ground cover and resource utilization.

Interestingly, Trinova and its combinations were associated with relatively high infestations of Convolvulus arvensis (CONAR) and Sinapis arvensis (SINAR), suggesting a possible varietal effect or compatibility issue influencing weed dynamics.

Twenty-five different weed species from 12 different families were identified from the trial area. The highest number of weed species was 8 species from Poaceae family, 4 species from Aseraceae family, 3 species from Brassicaceae family, 2 species from Amaranthaceae family, one species each from Caryophyllaceae, Convolvulaceae, Cyperaceae, Lamiceae, Malvaceae, Solanaceae and Plantaginaceae families. The total number of perennial weeds was 56.5, annual weeds 59.9, narrow-leaved weeds 54.8 and broad-leaved weeds 61.6

The highest number of weeds was determined in IFVN 567 bigvetch (14.28 weed m2) variety plots sown alone. The lowest number of weeds was determined in the plots where Özgen big vetch variety + Batigagrass (3.75 weed m2) were sown together. Perennial weeds were found to occur in IFVN 567 bigvetch (11.78 weed m2) plots. The lowest number of perennial weeds was determined in IFVN 567 + Efe 82 (0.50 weed m2) planting system. The highest number of annual weeds was determined in the plots sown with Efe 82 (8.50 weed m2) grass variety. The lowest number of annual weeds was determined in IFVN 567 bigvetch variety with 2.50 weed m2. The highest number of narrow-leaved weeds was determined in IFVN 567 (11.3 weed m2) and the lowest number of narrow-leaved weeds was determined in Özgen + Bartiga (1.0 weed m2) and Karakya + Trinova (1.0 weed m2) planting systems. The highest number of broad leaf weeds was determined in Efe 82 Narbonne Bean variety (8.0 weed m2), while the lowest number of broad leaf weeds was determined in Özgen + Bartiga planting system (1.8 weed m2).

Overall, the findings indicate that cropping system choice significantly affects weed flora, and that mixed cropping—especially with compatible cultivars—can be an effective ecological weed management strategy under organic conditions.

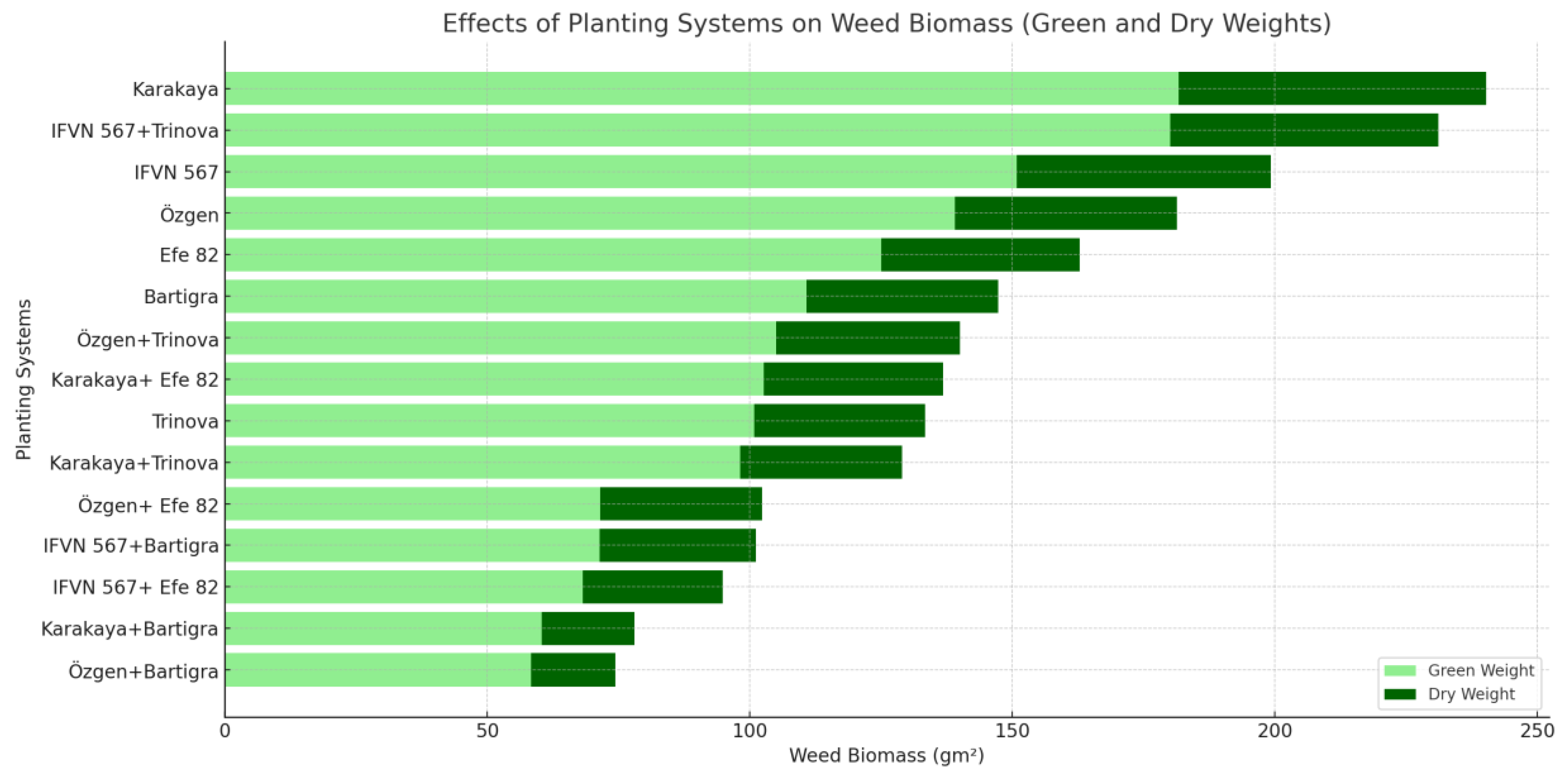

3.5. Weed Biomass Response to Different Planting Systems

Table 5 shows the impact of different planting systems on weed green weight (g/m²), dry weight (g/m²), and their general average. The results indicate that weed biomass is significantly influenced by the cropping strategy employed (

p<0.05).

The highest weed green weight was recorded in the Karakaya sole cropping system (181.66 g/m²), which was statistically similar to IFVN 567+Trinova (180.00 g/m²) and IFVN 567 (150.83 g/m²). These results suggest that pure stands or less competitive mixtures may allow more weed growth, likely due to increased light and space availability for weeds.

In contrast, the lowest weed green weights were observed in the Özgen+Bartigra (58.33 g/m²) and Karakaya+Bartigra (60.33 g/m²) mixtures, highlighting the potential of specific crop combinations in suppressing weed growth effectively. These combinations may provide better ground cover or more aggressive early growth, thereby limiting weed establishment.

Similarly, weed dry weight followed a comparable pattern, with the Karakaya pure stand (58.50 g/m²) and IFVN 567+Trinova (51.16 g/m²) resulting in significantly higher dry biomass, while the Özgen+Bartigra (16.00 g/m²) and Karakaya+Bartigra (17.66 g/m²) mixtures were among the lowest. These findings reinforce the importance of cultivar selection and complementary interactions in mixed cropping systems for ecological weed management.

The general average of weed biomass also reflected these trends, with the lowest values again recorded in Özgen+Bartigra (37.16 g/m²) and the highest in Karakaya (120.08 g/m²), emphasizing the suppressive advantage of certain mixtures over monocultures or less compatible combinations.

Overall, the data suggest that specific legume-grass mixtures—particularly those including Bartigra—are more effective in suppressing weed biomass, supporting their role in sustainable weed management strategies under organic or low-input systems.

Figure 3 illustrates the green and dry biomass of weeds (g/m²) as influenced by various planting systems. The results clearly demonstrate that sole cropping systems, particularly

Karakaya,

IFVN 567+Trinova, and

IFVN 567, supported the highest total weed biomass, indicating weaker weed suppression capability.

Karakaya recorded the maximum green biomass (181.66 g/m²) and dry biomass (58.50 g/m²), suggesting insufficient ground cover or lower competitiveness against weed emergence.

Conversely, the lowest weed biomass values were associated with mixed cropping systems, especially Özgen+Bartigra, Karakaya+Bartigra, and IFVN 567+Efe 82, which demonstrated enhanced weed suppression. These combinations likely benefit from complementary growth patterns and canopy structures that reduce available resources for weeds.

The stacked bar chart highlights the overall advantage of specific vetch-ryegrass mixtures in reducing both green and dry weed biomass. The visual trend supports the quantitative data, indicating that optimized cultivar combinations can serve as an effective strategy for ecological weed control under organic farming systems.

4. Discussion

4.1. Morphological Features

Narbon vetch and Italian ryegrass exhibited distinct size and architectural traits, with notable differences between pure and mixed stands. Narbon vetch is generally a relatively short, erect annual legume; for example, previous reports indicate it reaches roughly 30–60 cm in height. In contrast, Italian ryegrass can grow much taller – cultivated varieties often exceed 1 m (up to ~127 cm) under favorable conditions. In our trial, pure vetch stands were significantly shorter than ryegrass. However, in mixed cropping the vetch tended to attain greater heights and produce more branches than in sole stands (

Table 1). This trend is consistent with Azizi et al. (2013), who found that barley–Narbon vetch intercrops resulted in taller and more tillering plants of both species than their monocultures. The enhanced stature of vetch in mixtures likely reflects complementary resource use (e.g., better light interception and nitrogen availability) when grown with grass; legumes can exploit deeper soil N and fix atmospheric N, benefitting both partners. By contrast, ryegrass height did not increase in mixtures and in some cases was slightly reduced compared to its pure stand. This matches observations by Bacchi et al. (2021), who noted that Italian ryegrass had comparatively low competitive ability in grass–legume mixtures (yield was lower than in monoculture). In sum, the mixed stands induced a shift in growth allocation: vetch plants became relatively taller and more branched, while ryegrass invested comparatively less in height.

Stem and leaf traits also varied among treatments. Narbon vetch stem thickness in sole crops was on the order of 3–5 mm, and its leaflet size typically 2–5 cm long by 2–3 cm wide. In our data, mixed cropping had only modest effects on these dimensions; for example, vetch stems were marginally thicker in some mixtures, possibly reflecting vigorous growth under improved N status. Ryegrass leaf blades are characteristically long and narrow (often on the order of 10–20 cm long and ~0.5–1.0 cm wide), and we observed similar leaf dimensions across treatments. The measured leaf lengths and widths fell within these expected ranges: ryegrass leaves remained slender (around 0.7–0.9 cm wide) while vetch leaves remained broader (several centimeters). Interestingly, legume–grass mixtures are known to exhibit complementary foliage structures; legumes often develop broader leaves and deep roots while grasses maintain narrow, dense tillers. In our mixtures, the combined canopy likely exploited light more fully and may have shaded some lower leaves, but no extreme leaf size reductions were observed. Overall, leaf morphology was largely species-specific, with only slight adjustments between sole and mixed stands.

The number of lateral branches (vetch) and tillers (ryegrass) showed pronounced treatment differences. Narbon vetch typically has only a few main stems per plant; Sayar and Han (2014) reported ~2–3 stems per plant in various genotypes. In pure vetch stands, branching was limited (often 1–2 lateral stems). In contrast, mixed stands induced more vetch branches: the average number of lateral shoots per plant increased by 20–30% in mixtures (

Table 1). This suggests that when growing alongside ryegrass, vetch plants allocated more effort to branching – likely a response to the altered microenvironment (improved soil nitrogen and/or different light competition). Mixed cropping of legumes and grasses is known to enhance total biomass through such overyielding mechanisms. For ryegrass, tillering was generally profuse in all treatments; our data show dozens of tillers per plant (reflecting the grass’s high plasticity). Numerically, ryegrass plants in some mixed treatments produced more tillers than in their monocultures. This is in line with Saleem et al. (2019), who found that ryegrass mixed with common vetch produced higher biomass than ryegrass alone presumably because the added nitrogen from the legume stimulated grass growth and tiller initiation. However, when the legume share was very high, ryegrass tillering did not surpass that in sole grass (consistent with Bacchi et al. (2021), who saw ryegrass yields dip when legumes dominated the intercrop). In summary, mixtures tended to increase vetch branching and could enhance ryegrass tillering, reflecting mutual facilitation up to a point.

The significant differences (ANOVA p<0.05) among our treatments highlight how cultivar choice and cropping system interact. For example, the tallest plants and thickest stems were observed in specific cultivar combinations (

Table 1), indicating genotype × environment effects. Our findings corroborate earlier work: Saleem et al. (2019) concluded that growing ryegrass with a legume booster (common vetch) markedly improved forage yield, and Azizi et al. (2013) similarly documented higher growth and forage production in barley–vetch intercropping. Likewise, Sheaffer et al. (2022) emphasize that grass–legume mixtures often achieve superior stand structure because each species’ unique morphology (deep taprooted legumes vs. fibrous, crown-forming grasses) allows more efficient use of water, light, and nutrients. Our mixed stands appear to exemplify this: the vetch’s taproot and branching habit paired well with the ryegrass’s high tillering and tiller density. The improved morphological performance (more tillers and branches, fuller canopy) in mixtures likely underlies the higher overall yield often seen in forage mixtures.

These results have practical implications for organic forage systems. In organic farming – where synthetic N is absent – legume–grass mixtures can internally supply N and suppress weeds, boosting productivity and stand resilience. Çağlar et al. (2025) recently demonstrated that ryegrass-dominant vetch–ryegrass mixtures gave the highest forage yields and excellent weed control under organic management. Our morphological observations support that outcome: the vigorous growth form (taller legumes, denser grass shoots) in effective mixtures would shade out weeds and capture more sunlight. The complementary plant architectures of vetch and ryegrass thus translate into agronomic benefits. In summary, mixed cropping in this trial produced plants with enhanced morphology relative to monocultures a finding in keeping with both theory and prior experiments. In line with literature, our data suggest that mixed legume–grass stands yield a more robust, branched canopy structure than pure stands, reinforcing the value of intercropping for sustainable organic forage production.

The morphological composition and forage performance of Narbon vetch and Italian ryegrass, whether grown as monocultures or mixtures, displayed significant variation in leaf-stem ratio, botanical composition, and yield traits under organic management (

Table 2).

4.2. Leaf-Stem Ratio and Structural Balance

The leaf-to-stem ratio is a critical indicator of forage quality, as leaves generally contain more crude protein and digestible nutrients than stems. In this study, ryegrass monocultures had higher leaf ratios compared to vetch monocultures, consistent with prior observations that ryegrass maintains a higher leaf proportion due to its fine and tender morphology (Kumlay et al., 2020). For instance, cultivars like ‘Bartigra’ and ‘Trinova’ exhibited leaf ratios above 86%, whereas vetch cultivars remained around 57–64%. In mixtures, the leaf-to-stem ratio tended to decrease slightly, particularly in vetch components, which is consistent with results reported by Saleem et al. (2019), who noted structural shifts when legumes are mixed with aggressive grasses.

4.3. Botanical Composition in Mixed Stands

Botanical composition data revealed that ryegrass consistently dominated the mixtures, often contributing over 75–83% of the stand biomass, regardless of the vetch genotype. These findings align with Bacchi et al. (2021), who emphasized ryegrass’s competitive growth and rapid tillering as key drivers of dominance in legume–grass intercropping systems. Vetch’s presence was higher in combinations involving cultivars with more vigorous growth, such as ‘Özgen’ or ‘Karakaya’, suggesting that legume cultivar selection can influence species balance. Such imbalances, although common, can be optimized through seed rate adjustments or spatial planting patterns (Sleugh et al., 2000).

4.4. Forage Yield Performance

Among the treatments, sole cropping of the high-yielding vetch genotype ‘IFFN 567’ and the ryegrass cultivars ‘Bartigra’ and ‘Trinova’ recorded the highest green forage and hay yields. Notably, ‘IFFN 567’ reached up to 4352.6 kg da⁻¹ green herbage and 925.6 kg da⁻¹ hay yield, indicating its potential as a biomass-rich legume even under low-input organic conditions. These results are comparable to those of Azizi et al. (2013), who reported similarly high productivity in barley–vetch intercropping under stress-limited systems. In mixed stands, combinations such as IFFN 567 + Trinova or + Bartigra approached the productivity of sole cropping, indicating positive interspecies interaction.

4.5. Crude Protein Yield and Quality Implications

Crude protein (CP) yield is a major determinant of forage nutritional value. Here, CP yield ranged from 223.71 kg da⁻¹ in pure IFFN 567 to as low as 38.92 kg da⁻¹ in the lowest-performing mixtures. Mixed stands generally produced intermediate CP yields, with best-performing combinations (IFFN 567 + Trinova and Özgen + Trinova) yielding over 130–190 kg da⁻¹. This increase reflects the classic nitrogen-fixing contribution of legumes, as reported in prior research by Carlsson and Huss-Danell (2003), where legume-based mixtures boosted CP concentration and total protein yield in grasslands.

4.6. Ecological and Practical Significance

The results highlight the ecological complementarity and productivity potential of vetch–ryegrass mixtures under organic management. While ryegrass dominated biomass, vetch contributed nitrogen and improved protein levels. According to Sheaffer et al. (2022), such complementary mixtures provide not only better quality forage but also improved weed suppression and soil health – essential outcomes for sustainable organic systems. Moreover, optimal combinations like IFFN 567 + Trinova yielded high biomass and CP without synthetic inputs, making them suitable for low-input forage systems.

In summary, while pure vetch stands excelled in protein yield, and pure ryegrass excelled in dry matter yield, their combinations balanced yield and quality. The results confirm the strategic value of choosing compatible cultivars in mixed cropping systems, and support the broader literature on legume–grass intercropping benefits in organic forage production.

The evaluation of crude protein content, fiber fractions (ADF and NDF), forage yields, and land equivalent ratios (LER) for dry matter and protein highlights the agronomic and nutritional advantages of Narbon vetch and ryegrass mixtures over sole cropping systems (

Table 3).

4.7. Crude Protein Content

Protein content is a crucial quality indicator for forage crops. In the current study, Narbon vetch monocultures showed significantly higher crude protein ratios compared to ryegrass monocultures, consistent with the known nitrogen-fixing capacity of legumes (Carlsson & Huss-Danell, 2003). The highest crude protein content was found in ‘IFFN 567’ (24.17%), followed by ‘Özgen’ (23.07%) and ‘Karakaya’ (22.17%). In mixed cropping systems, combinations such as IFFN 567 + Trinova (21.90% + 12.43%) and Özgen + Trinova (22.43% + 12.70%) provided balanced protein content from both species. Similar trends were also reported by Sadeghi and Gill (2014), who observed enhanced protein content in vetch–grass mixtures compared to pure stands.

4.8. Fiber Fractions (ADF and NDF)

Fiber content, especially acid detergent fiber (ADF) and neutral detergent fiber (NDF), directly affects digestibility. Ryegrass had higher ADF and NDF values than vetch, in line with findings by Kumlay et al. (2020) and Van Soest (1994), confirming that grasses typically have more structural carbohydrates. However, the inclusion of vetch in mixtures effectively reduced the overall fiber concentrations. For example, the mixture of IFFN 567 + Trinova exhibited moderate ADF (27.97% + 28.40%) and NDF (31.30% + 44.17%) values, suggesting improved digestibility compared to pure ryegrass.

4.9. Forage Yield

Green and hay forage yields were significantly higher in mixed stands compared to sole crops. The highest total green herbage yield (5969.6 kg da⁻¹) and hay yield (1327.8 kg da⁻¹) were obtained from IFFN 567 + Trinova, closely followed by IFFN 567 + Bartigra. These results demonstrate a clear yield advantage of well-matched vetch and ryegrass genotypes under organic conditions. Previous studies (Sleugh et al., 2000; Azizi et al., 2013) have reported similar synergistic effects in legume–grass intercropping systems, particularly when species complementarity in growth dynamics is exploited.

4.10. Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) for Dry Matter and Protein

LER values greater than 1.0 indicate yield advantages in intercropping over monocropping. In this study, all vetch–ryegrass mixtures showed DM-LER and Protein-LER values significantly above 1.0, with the highest values (1.67 and 1.96, respectively) recorded in IFFN 567 + Trinova. This suggests improved land-use efficiency and greater protein productivity per unit area. These findings support the conclusions of Carlsson and Huss-Danell (2003) and Sadeghi & Gill (2014), emphasizing the potential of intercropping to maximize biomass and protein yield in sustainable systems. Moreover, the mixtures with Trinova consistently produced high protein LERs, indicating the strong contribution of this ryegrass genotype to both biomass and quality in combinations.

4.11. Ecological and Practical Implications

From a sustainability perspective, legume–grass mixtures offer better soil health, reduced reliance on external nitrogen inputs, and improved forage quality (Sheaffer et al., 2022). The organic system evaluated in this study benefitted from the nitrogen-fixing ability of vetch, the competitive growth of ryegrass, and their synergistic interaction. Particularly, IFFN 567 combined with Bartigra or Trinova stands out as an ideal forage solution under organic systems, balancing yield and quality while enhancing land use efficiency.

4.12. Weed Suppression

Weed suppression ability is a critical criterion in evaluating cropping systems under organic management due to the absence of herbicide inputs. The results from

Table 4 indicate that weed species composition and densities varied considerably across different cropping combinations.

Overall, intercropping treatments exhibited a reduction in weed numbers compared to sole cropping, likely due to greater canopy coverage, improved soil shading, and niche occupation by both legume and grass components. This aligns with findings from Bàrberi (2002), who emphasized the role of interspecific competition in natural weed suppression.

Among the mixtures, ‘IFVN 567 + Bartigra’ and ‘Karakaya + Bartigra’ demonstrated the lowest weed presence overall, with limited occurrences of dominant species such as Avena fatua, Convolvulus arvensis, and Lamium amplexicaule. These results suggest a strong suppressive effect of this particular genotype combination.

On the contrary, some sole crops such as ‘IFVN 567’ and ‘Karakaya’ exhibited relatively higher weed infestations, notably with Lolium temulentum, Lamium amplexicaule, and Veronica hederifolia, which are common in organic forage systems. For instance, Lamium amplexicaule density reached up to 9.00 plants m⁻² in IFVN 567 monoculture, indicating the vulnerability of sole legume plots to winter annual weed species.

Notably, mixtures containing Trinova ryegrass (e.g., ‘Özgen + Trinova’, ‘IFVN 567 + Trinova’) were moderately successful in reducing weed presence, although in some cases Convolvulus arvensis and Matricaria chamomilla persisted. This suggests that while ryegrass contributes to weed suppression, its effectiveness depends on the companion vetch genotype and the spatial growth compatibility.

These results underline that crop mixture composition strongly influences weed suppression, with certain vetch–ryegrass combinations showing a more synergistic interaction in minimizing weed biomass. These findings corroborate studies by Hauggaard-Nielsen et al. (2001), who reported that optimal species selection in intercrops enhances weed competitiveness without sacrificing forage quality or yield.

The results from

Table 5 demonstrate that weed green and dry biomass significantly varied among planting systems under organic management. The

lowest weed biomass was recorded in

‘Özgen + Bartigra’ (green: 58.33 g m⁻²; dry: 16.00 g m⁻²), indicating strong weed suppression potential of this mixture, likely due to better canopy closure and faster establishment. Similarly,

‘Karakaya + Bartigra’ and

‘IFVN 567 + Efe 82’ also suppressed weed biomass effectively.

In contrast, monoculture plots, particularly ‘Karakaya’ (green: 181.66 g m⁻²; dry: 58.50 g m⁻²) and ‘IFVN 567 + Trinova’, exhibited the highest weed biomass, suggesting weaker competition against weed emergence, potentially due to more open canopy structures or slower early development of the dominant crop component.

The general trend indicates that mixtures involving Bartigra ryegrass, especially when combined with Özgen or Karakaya vetch genotypes, were more successful in reducing weed biomass than mixtures with Trinova. These findings align with previous research (e.g., Hauggaard-Nielsen et al., 2001) that emphasizes the importance of crop density, growth habit, and canopy architecture in achieving natural weed suppression through intercropping.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study highlight the agronomic advantages of intercropping Narbon vetch and Italian ryegrass under organic management. While certain monocultures excelled in specific parameters, mixed cropping systems particularly IFVN 567+Trinova and IFVN 567+Bartigrademonstrated superior performance in forage yield, crude protein content, land use efficiency (LER), and weed suppression. These benefits are attributed to the complementary growth habits of the two species, which allow for more effective utilization of environmental resources and improved ground coverage. The study emphasizes the importance of genotype selection in designing productive and ecologically resilient forage systems. Under organic or low-input conditions, integrating competitive grass cultivars with high-quality legume genotypes offers a sustainable approach to optimizing both yield and ecological weed control.

Author Contributions

This research is H.C.’s master thesis work. S.K.A. and K.K. also served as a consultant in this research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

This study was the article based on the masters thesis coded FBE EYK 2023/10528240 for the Department of Field Crops, Institute of Sciences, Bilecik Seyh Edebali University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- AOAC. (1990). Official methods of analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA.

- Azizi, K.; Daraei Mofrad, A.; Heidari, S.; Amini Dehaghi, M.; Kahrizi, D. (2013). A study on the qualitative and quantitative traits of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) and Narbon vetch (Vicia narbonensis L.) in intercropping and sole cropping systems under weed interference. J. Appl. Crop Res., 26(98), 88.

- Bacchi, M.; Monti, M.; Calvi, A.; Lo Presti, E.; Pellicanò, A.; Preiti, G. (2021). Forage potential of cereal–legume intercrops: Agronomic performances, yield, quality and LER in two harvest times in a Mediterranean environment. Agronomy, 11, 121. [CrossRef]

- Bàrberi, P. (2002). Weed management in organic agriculture: Are we addressing the right issues? Weed Res., 42, 177–193. [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, G.; Huss-Danell, K. (2003). Nitrogen fixation in perennial forage legumes in the field. Plant Soil, 253, 353–372. [CrossRef]

- Çağlar, H.; Kızıl Aydemir, S.; Kaçan, K. (2025). Assessment of the efficiency of combined seeding rates of common vetch and ryegrass for controlling weed development in organic forage cultivation systems. Life, 15, 731. [CrossRef]

- Gallandt, E.R. (2006). How can we target the weed seedbank? Weed Sci., 54, 588–596. [CrossRef]

- Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Ambus, P.; Jensen, E.S. (2001). Interspecific competition, N use and interference with weeds in pea–barley intercropping. Field Crops Res., 70, 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Kumlay, A.M.; Yavuz, T.; Altinok, S. (2020). Fodder yield and quality performance of Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) genotypes under different environmental conditions. Turk. J. Field Crops, 25, 203–210. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.M.; Gill, R.A. (2014). Evaluation of yield and quality traits in common vetch (Vicia sativa L.)–ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum L.) mixtures in a Mediterranean-type environment. Grass Forage Sci., 69, 234–243. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Malik, A.M.; Hassan, N.U.; Qamar, I.A. (2019). Effect of common vetch (Vicia sativa L.) on growth and yield of ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum L.). Pak. J. Agric. Res., 32, 675–683. [CrossRef]

- Sayar, M.S.; Han, Z. (2014). Determination of forage yield performance of some promising Narbon vetch lines under rainfed conditions in Southeastern Turkey. J. Agric. Sci., 20, 376–386. [CrossRef]

- Sheaffer, C.; Goplen, J.; Fernholz, C.; Salzer, T. (2022). Advantages of legume–grass mixtures. Minnesota Crop News. https://blog-crop-news.extension.umn.edu/2022/03/benefits-of-legume-grass-mixtures.html.

- Sleugh, B.; Moore, K.J.; George, J.R.; Brummer, E.C. (2000). Binary legume–grass mixtures: An alternative forage production system. Agron. J., 92, 463–469. [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J. (1994). Nutritional ecology of the ruminant, 2nd ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.D.; Lewis, B.A. (1991). Methods for dietary fibre, neutral detergent fibre and non-starch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci., 74, 3583–3597. [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, J.; Inga, Y.T.; Díaz, E.; Montalbetti, E.; Holvoet, A.; Vidaurre, H. (2024). Agronomic and nutritional evaluation of INIA 910—Kumymarca ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.): An alternative for sustainable forage production in Northwest Peru. Agronomy, 15, 100. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).