1. Introduction

The increasing food production, sustained by the growing trend of world population, is bringing a considerable fertilizer consumption, aimed to balance the gap between the permanent removal of nutrients from the field, as a consequence of the harvested parts of the crop, and the natural availability of nutrients in the soil. This process raises questions about the sustainability of agricultural production, as the intensive use of natural resources and external inputs for agricultural production is having a significant impact on the environment. Production of vegetable crops under controlled environments (i.e. greenhouses) has expanded considerably over recent decades in Mediterranean areas [

1]. Initially, research efforts and the related introduction of technical innovations focused on high-quality and healthy products. However, concern with environmentally-sustainable production has risen in the last decades as industrial greenhouse crops are usually seen as entailing high environmental impact [

2]. On the other hand, there is also plenty of evidence that greenhouse vegetable production may decrease the environmental impact compared to the field cultivation [

3].

Efficient use of resources (water and fertilizers) is a target in irrigated greenhouse agriculture, to achieve higher sustainability of the production process, better crop performance, improved nutritional and sensorial quality [

4,

5]. Soilless cultivation produces several benefits compared to traditional systems, including the possibility to standardize the production process, to improve plant growth and yield, and to obtain higher efficiency in water and nutrient use [

6]. Moreover, soilless cultivation allows to overcome problems related to soil-born pathogens and inadequate soil fertility [

7].

Fertilization practice in vegetable production sector, with particular focus on nitrogen (N), is under the spotlight [

8]. In fact, over-fertilization has been generally perceived as a cheap insurance against yield loss, so that a general tendency to apply excessive nutrients, in particular N, is widespread, leading to appreciable impact on the environment [

9]. However, several factors including consumers demand for sustainable production processes and regulations pressure toward decreasing the negative impact of agriculture on the environment (e.g. Council Directive 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 concerning the protection of waters against pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources), are promoting practices aimed at reducing the use of fertilizers.

According to trends observed during recent years, baby leaf vegetables such as spinach, rocket, and lettuce gained economic importance since they are basic components of ready-made salads [

10]. Among these, wild rocket (

Diplotaxis tenuifolia L.) is a popular leafy vegetable due to its distinct taste and nutritional content, which cultivation is widespread and in further expansion [

11,

12]. Specifically, rocket leaves are rich in vitamins such as A, B, C, and K, iron, and essential proteins, which contribute to human health [

13]. This product, much appreciated by consumers, is a good source of nutrients and antioxidant molecules, especially glucosinolates [

14], but is also a hyper-accumulator of nitrates [

15].

As the most of leafy vegetable, rocket leaves has high perishability during the storage due to their high respiration rate [

16], which limits their shelf life. During storage, leaf quality rapidly decreases because of the increase of yellowing strictly related to the chlorophyll degradation [

17]. Usually, alterations of the common green colour of leafy vegetables is a limiting factor for their marketability as they influence the consumers’ choice [

18].

The quality of rocket leaves at harvest and during the storage depends on several preharvest factors such as pedoclimatic factors, cultural practices (cultivation system, nutrient or water management), and genotype (landraces, cultivar) [

19]. Among the cultivation strategies, soilless systems are considered efficient plant growing methodology in the fresh-cut company, as it is possible to control the product quality by the appropriate composition and management of nutrient solution [

20]. In postharvest, it is necessary to start with a high-quality product to ensure a longer shelf-life.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effects of different levels of fertilizers application, in soilless (ScS) and in soil-bound (SbS) cultivation systems, in terms of inputs (water and nutrients) use efficiency and productivity, and crop yield of rocket. Moreover, the effect of fertilization levels on quality traits at harvest and during postharvest was evaluated on rocket leaves produced by SbS or ScS, with the aim to evaluate the feasibility of sustainable low input fertilization in preserving quality at harvest and during postharvest.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material and growing conditions

Two parallel experiments, one in SbS and another in ScS cultivation conditions, were carried out at the Experimental Farm “La Noria” of the Institute of Sciences of Food Production (ISPA-CNR) in Mola di Bari, Italy (41°03' N; 17°04' E; 24 m above sea level) during 2020-2021 growing season. Wild rocket (

Diplotaxis tenuifolia L., cv. Dallas, Isi Sementi, Fidenza, Italy) plants were cultivated under unheated plastic greenhouse conditions into two independent environments, one equipped for SbS (a polietylene multitunnel type) and another for ScS (a polymetacrylate rigid-panel type). In both cases, crop management practices (e.g., disease and pest control) were similarly based on local practices. In both cultivation systems, the crop was subjected to treatments consisting in a high– compared to a low–input fertilization program named HF and LF respectively (see sections 2.1.1. and 2.1.2 for specific details on the application of fertilization treatments in the two cultivation systems). Rockets seeds were sown on October 14

th 2020 in polystyrene plug trays and the seedlings were transplanted four weeks later with a density of 80 plant/m

2 [

7]. In both cultivation systems, treatments (LF and HF) were arranged in a complete randomized block design with five replications. Temperature inside the greenhouse ranged over the growing cycle between minimum and maximum values of 1.5 and 41.5 °C, respectively, with a mean value of 13.5 °C; air relative humidity ranged between minimum and maximum values of 15.8 and 98.8 %, respectively, with a mean value of 70.4 %.

2.1.1. Soil–bound growing conditions

In soil–bound sector (SbS), soil was a typical Mediterranean “Terra Rossa” clay soil. The main soil properties are reported in

Table 1.

Plants were watered by drip irrigation, using rainwater stored in collection tanks. The irrigation schedule was based on local practices. Sixty and 30 kg/ha of nitrogen (N) were applied by fertigation as calcium nitrate in SbS-HF and SbS-LF treatment, respectively.

2.1.2. Soilless growing conditions

Seedlings were transplanted in 4.5 L plastic containers, filled with a peat:perlite (3:1 in volume) mixture. Fertilizers were added to pre–collected rainwater for the preparation of the nutrient solution (NS). A drip irrigation system was adopted. The irrigation schedule, automatically operated by a timer, was subjected to periodical adjustments based on plant water need variations, assessed by measuring the leaching rate approximately every two days, and having a < 20 % leaching fraction as a target. An open-cycle NS management was adopted. In the ScS–HF treatment, a standard NS (Hoagland and Arnoon, 1950, modified) commonly adopted in soilless cultivation, containing N (15.0 mM), phosphorus (1.0 mM), potassium (6.0 mM), magnesium (2.0 mM), calcium (5.0 mM), sulphur (2.9 mM), was used. In the ScS–LF treatment, plants were fertigated with a NS with reduced macro-nutrients concentration, as proposed by [

7], containing N (11.0 mM), phosphorus (1.0 mM), potassium (4.4 mM), magnesium (1.7 mM), calcium (3.2 mM), sulphur (2.1 mM). In both treatments, iron (20 μM), manganese (5 μM), zinc (2 μM), boron (25 μM), copper (0.5 μM), and molybdenum (0.1 μM) were added in NS as micronutrients.

2.2. Plant growth, dry matter, leaf chlorophyll content, water use efficiency and nutrients productivity

According to the common practice for wild rocket salad, the crop cycle consisted of subsequent harvest cuts and re–shootings. In the experiments, six cuts occurred from middle December to early May. Harvests were carried out when leaves of different treatments reached the commercial harvest stage (approximately until several serrated 10-12 cm leaves were present on each plant) [

21,

22]. Leaves samples were collected and weighed in order to determine yield and placed in a forced-draft oven at 65 °C, to determine dry matter percentage.

On 5 leaves from each plot, leaf chlorophyll was measured using a rapid and no-destructive chlorophyll meter (Apogee MC-100, Apogee instruments, Logan, UT USA) in January and February for SbS and February and March for ScS. Chlorophyll data obtained with this procedure were used to develop a Partial Least Square Regression (PLSR) model for the prediction of cultivation system by rapid and no-destructive tools (see section 2.4 and 3.3).

Water use efficiency (WUE) was expressed as fresh weight of edible product per liter of water supplied as irrigation. Partial factor productivity (PFP) for nutrients (N, P, K, Ca and Mg for ScS, and N for SbS) was expressed as fresh weight of edible product per gram of nutrient supplied [

23].

2.3. Postharvest quality parameters

The rocket leaves used during the postharvest storage, were harvest cut during the months of January and February and March for SbS and ScS, respectively. At two consecutive harvest cut times (HC1 and HC2), fresh-cut rocket leaves, separated per cultivation conditions and fertilization program, were transported in refrigerated condition to the postharvest laboratory of ISPA-CNR in Foggia for the analysis of postharvest quality. The rocket leaves with defects and mechanical damages were removed, while good samples were packed in open polyethylene bags (Orved, Musile di Piave, Italy) of about 600 g each one. In particular, 10 bags (5 replicates x 2 fertilization programs) were prepared for each cultivation condition, with a total of 20 PP bags. Subsequently, all samples were stored at 10 (± 1) °C (as commonly occur in the Italian retailer market) for 16 d. At each sampling day (at harvest and during the storage), sensory parameters (visual quality and odour), respiration rate, dry matter, colour parameters, electrolyte leakage, antioxidant activity, total phenols, total chlorophyll and ammonia content were evaluated.

2.3.1. Respiration rate, dry matter, electrolyte leakage and ammonia content

The respiration rate of fresh-cut rocket leaves was determined at 10 °C at harvest and at each sampling time using a closed system as reported by [

24], with slight modification. In detail, the amount of about 100 g for each replicate of rocket leaves to analyze was taken from each bag and were put into 3.6 L sealed plastic jar where CO

2 was allowed to accumulate up to 0.1 % as the concentration of the CO

2 standard. The time taken to reach this value was detected by taking CO

2 measurements at regular time intervals [

25]. The respiration rate was expressed as µmol CO

2/kg s.

After the respiration rate analysis, the same samples were used for postharvest destructive determinations, described below.

The dry matter content was calculated as the percentage ratio between the dry and the fresh weight of rocket leaves. To determine the dry weight, 30 g per replicate of chopped fresh-cut rocket leaves were dried using a forced ventilation oven (M700-TB, MPM Instruments, Bernareggio, Italy) at 65 °C until reaching a constant mass.

The electrolyte leakage was determined following the methodology reported by [

24]. Rocket leaves disks, obtained using a cork borer for about 2.5 g per replicate, were dipped in 25 mL of distilled water. After 30 min of storage at 10 °C, the conductivity of the solution was measured by a conductivity meter (Cond. 51+ - XS Instruments, Carpi, Italy). After that, the tubes with the leaf disks, were frozen for 48 h. Successively, on the samples thawed the conductivity was measured and the same calculated as the percentage ratio of initial over total conductivity.

Ammonia content was evaluated according to [

26]. About 5 g of chopped rocket leaves were homogenized for 2 min in 20 mL of distilled water in cold conditions, and then centrifuged for 5 min at 6440 g at 4 °C. Then, the supernatant (0.5 mL) was mixed with 5 mL of nitroprusside reagent (phenol and hypochlorite in alkali reaction mixture) and heated at 37 °C for 20 min. The colour development after incubation, was determined with the spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) (reading the absorbance at 635 nm). The content of NH

4+ was expressed as μg NH

4+/g of fresh weight (fw), using ammonium sulphate as standard (0–10 μg/mL, R

2 = 0.999).

2.3.2. Sensory analysis and colour parameters

During storage, as regard sensory visual quality (VQ), samples were taken from each PP bag and evaluated by a group of 5 trained researchers (made up of 2 female and 4 male panelists) using a 5 to 1 rating scale proposed by [

24], where 5 = very good, 4 = good, 3 = fair, 2 = poor, 1 = very poor. A score of 3 was considered as the shelf-life limit, while a score of 2 represented the limit of edibility.

The CIELab colour parameters (

L*,

a* and

b*) were measured, for each replicate, on 3 random points on the surface of 10 fresh-cut rocket leaves using a colorimeter (CR400, Konica Minolta, Osaka, Japan). The calibration of the instrument was performed with a standard reference having 97.44, 0.10 and 2.04 as values of

L*,

a* and

b*, respectively. To measure colour variations during the storage, ΔE* was calculated according to the equation reported by [

27], while hue angle was obtained by the equations reported by [

28]. Additionally, yellowness index (YI) was calculated from primary

L*,

a* and

b* readings, according to the equation reported by [

28]:

2.3.3. Antioxidant activity, total phenols and total chlorophyll content

The same extraction procedure was used for DPPH assay and Folin-Ciocalteu Reducing Capacity analysis, as reported by [

29]. In detail, for each replicate, 5 g of chopped rocket leaves were homogenized in 20 mL methanol/water solution (80:20 v/v) for 2 min, using a homogenizer (T-25 digital ULTRA-TURRAX®—IKA, Staufen, Germany) and then centrifuged (Prism C2500-R, Labnet, Edison, NJ, USA) at 6440

xg for 5 min at 4 °C. The extracts were collected and stored at -20 °C until the analysis.

The antioxidant activity was measured according to the procedure of the DPPH assay described by [

30] using the methanol extracts. The absorbance at 515 nm was read after 40 min using a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The results were expressed as milligrams of Trolox per 100 g of fw using a Trolox calibration curve (82–625 µM; R

2 = 0.999).

The total phenols content was determined according to [

26]. In detail, 100 µL of each extract were mixed to 1.58 mL of water, 100 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent and 300 µL of sodium carbonate solution (200 g/L). The absorbance at 765 nm was detected after 2 h of incubation in the dark and the results were reported as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per 100 g of fw. The calibration curve of gallic acid was prepared with five points, from 50 to 500 µg/mL, with R

2 = 0.998.

The total chlorophyll content was measured using the spectrophotometric method reported by [

10]. In detail, 5 g of chopped samples was extracted in 50 mL acetone/water (80:20 v/v) solution with the homogenizer for 1 min and then centrifuged (SL 16 Centrifuge - Thermo Fisher Scientific, Langenselbold, Germany) at 6440

xg for 5 min. The extraction was repeated 5 times (10 mL of acetone/water solution per time) to remove all pigments and extracts were combined. The absorbance was read on extracts proper diluted at three wavelengths (663.2 nm, 646.8 nm, and 470 nm). Total chlorophyll content was expressed as milligrams per 100 g of fw using the equation reported by [

31].

2.4. Statistical analysis

Plant growth parameters, WUE and nutrients PFP data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). Treatment means were considered different when there was a significant effect at the P < 0.05 level. The statistical software STATISTICA 10.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) was used for the analysis.

For postharvest quality parameters, a two multifactor ANOVA for P ≤ 0.05 was performed with the aim to evaluate the effect of the fertilization programs (HF or LF), the storage time and their interaction on postharvest quality parameters of fresh-cut rocket leaves cultivated in SbS or ScS. The mean values (n = 5) were separated using the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) test (p ≤ 0.05). The statistical software Statgraphics Centurion (version 18.1.12, Warrenton, Virginia, USA) was used for the analyses.

Partial least squares regression (PLSR) was run using the software The Unscrambler X (CAMO AS, Oslo, Norway) in order to develop and compare models able to predict the cultivation system using as predictors chlorophyll data obtained by the Apogee meter or through the conventional destructive methodology.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Water consumption, crop performance, plant physiology and chemical composition

The ScS improved earliness compared to SbS (the HC1 in ScS occurred on December 21

st, while in SbS 17 days delay was observed, data not shown). However, with the progress of the production cycle, the time gap between harvests in the two systems gradually narrowed. This may be due to the optimal growing conditions provided to plants by soilless cultivation, leading to reduced transplant stress, as outlined also for other species [

32].

In ScS, the cumulative yield and the dry matter percentage of the ScS-HF were higher than ScS-LF treatment (by 11 and 10 %, respectively -

Table 2). On the other hand, WUE was slightly lower in ScS-HF compared to ScS-LF (

Table 2), and a more remarkable effect was observed on PFP, that was 30, 31, 8, 40, and 21 % lower, for N, K, P, Ca and Mg, respectively in ScS-HF compared to ScS-LF (

Table 2). PFP parameter represents a simple, but effective expression of production efficiency in terms of units of harvested product per unit of nutrients applied as fertilizer, and it was clearly higher with low fertilization conditions.

Additionally, in SbS the cumulative production and the dry matter percentage observed in SbS-HF treatment were higher than in SbS-LF treatment (by 9 and 4 %, respectively -

Table 3). Contrary to what was observed in ScS, where only slight effects were observed on WUE, in SbS-HF the WUE was 9.2 % higher than in SbS-LF, while the N PFP was higher in the SbS-LF (by 82 %).

Nutrient availability is an essential factor to maximize production, and it is well known that rocket responds well to good nutrient availability in the root zone [

33,

34,

35,

36]. The different effects of treatments on WUE in SbS (more pronounced) and ScS (slighter) growing conditions, can be explained by the possibility offered by soilless cultivation for a relatively easy optimization of irrigation management compared to soil-bound growing conditions. In soilless cultivation, in fact, it is possible to detect conditions of excessive water supply by simple collection and measurements of leachate fraction (much more complicated in soil-bound cultivation conditions), and it is possible to implement subsequent adjustments of irrigation scheduling in order to match water supply with plant needs. However, the PFP has always been by far higher with LF treatments, both in soil-bound and in soilless conditions, allowing for both excellent production levels and more sustainable management of nutrients. The intensive use of resources (namely water and fertilizers in this study) implies environmental problems due to the loss of nutrients, especially N, but also P and K [

8]. The effects of fertilization on product quality should also be taken into account, in particular in rocket salad being this species a hyper-accumulator of nitrates [

15]. In a previously published paper related to the same experiment presented in this manuscript [

22], it has been reported that the fertilization dose and the growing system did not modify nitrate content, with the exception of the soilless system treated with the highest fertilizer dose, where nitrate slightly exceeded regulatory limits. In this context, the correct management of the fertilizer application represents one of the major challenges to be faced for rational use of inputs in agriculture, for maintaining good production levels while minimizing environmental impact, as required by the increasingly pressing demand of consumers who require more sustainable production processes[

8,

37]. In both ScS and SbS, the leaf chlorophyll content was not influenced by the levels of fertilizers application (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

3.2. Postharvest quality parameters

3.2.1. Respiration rate, sensory VQ and colour parameters

In

Table 4 the effects of the fertilization programs (HF or LF), the storage time (0, 6, 9, 12 or 16 days) and their interaction on sensory, physical and chemical parameters of fresh-cut rocket leaves stored at 10 °C and cultivated on ScS or SbS are reported. As expected, results from the multifactor ANOVA showed that the storage time affected all parameters analyzed in SbS and ScS, except for the dry matter (

Table 4). Main effects of the storage time on quality postharvest parameters are well known. It is widely demonstrated that during the postharvest storage, vegetables produce heat, moisture and CO

2 which cause physiological and chemical changes and as a consequence of the postharvest degradation of the product [

38]

As regards the respiration rate of samples cultivated on ScS, results obtained from the multifactor ANOVA showed that all factors (fertilization program, storage time and their interaction) were significant in the two harvest cuts (

Table 4). At harvest, no statistical differences were observed among treatments in both harvest times, showing high respiration value [

25] in the range of 20 – 36 µmol CO

2/kg s, in agreement with values reported by [

24] (

Figure 1). Other authors reported values of respiration rate in rocket leaves stored at 4 °C or 17 °C of about 8.5 and 32.8 μmol CO

2/ kg s, respectively [

39,

40]. These differences could be due to the effects of cultivar, preharvest management practices,climatic conditions, maturity stage of the leaves at harvest and postharvest handlings [

13,

41].

In HC1, the trend of respiration rate in ScS-HF samples was almost the same after 16 days, while ScS-LF samples showed an increase (1.5-fold respect to fresh samples) from the 12

th day until the end of storage (

Figure 1A). Regards the HC2, the ScS-LF rocket leaves started to show higher values of respiration rate compared to ScS-HF samples from the 9th day of storage, reaching the highest rate at 12

th day (30.1 ± 0.86 µmol CO

2/kg s).

After, it remained almost constant until the end of storage, showing no statistical differences among the fertilization programs (

Figure 1B). Differences in respiration rate among the fertilization treatment could be related to the dry matter content. [

42] found that wild rocket with high respiration rate had higher dry matter content than leaves with lower respiration rate.

As for results of the multifactor ANOVA performed on rocket leaves cultivated on SbS, respiration rate, that showed values of about 36.7 µmol CO

2/kg s at harvests, was affected only by the storage time in both harvest cuts (

Table 4).

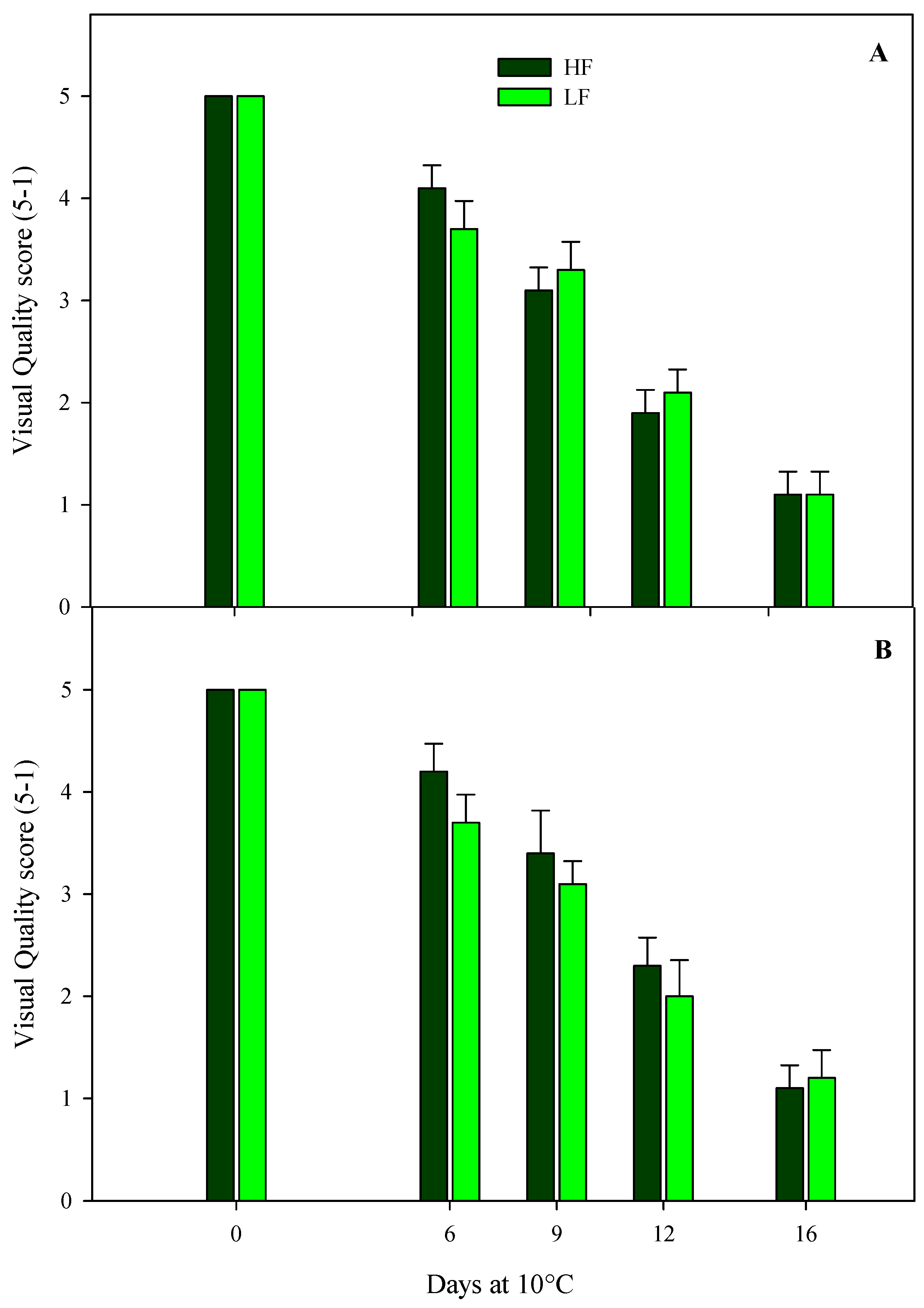

Regarding the sensory VQ of rocket leaves cultivated on ScS, in both harvest cuts, all treatments showed a gradual decrease during the storage, reaching the shelf-life limit (score 3) and the limit of edibility (score 2) after 9 and 12 days, respectively (

Figure 2). No significant differences were observed among the fertilization treatments, demonstrating that it is possible to reduce the quantity of fertilizer during the cultivation without compromising the visual aspect of the fresh-cut rocket leaves. Sensory VQ of rocket leaves obtained by SbS was significantly affected by the storage time in both harvest cuts (

Table 4). As expected, a decrease was observed along storage, reaching the commercial limit (score 3) and the limit of edibility (score 2) after 12 and 16 days, respectively (data not shown).

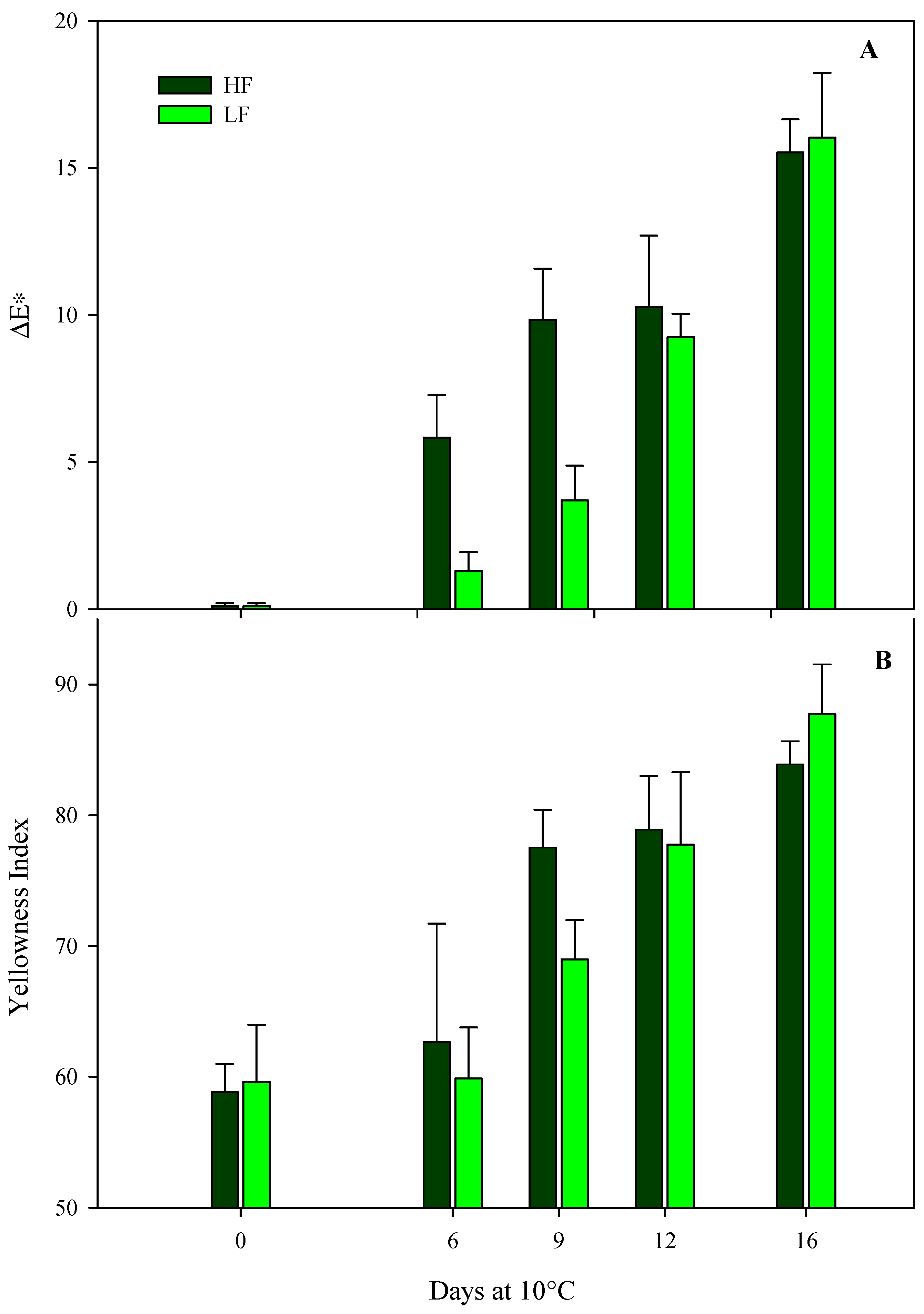

Colour is one of the most important traits for food preference and pleasantness, and it determines the freshness of rocket leaves [

43]. In green leafy vegetables, a loss of VQ and a reduction of consumer’s acceptability are strictly associated to the reduction of green colour during the postharvest storage. ΔE* and YI considered in this research work were significantly influenced by all factors (fertilization program, storage time and their interaction) at HC1, while the hue angle was affected only by the storage time (

Table 4), demonstrating a gradual yellowing of rocket leaves during the storage. In detail, just after 6 days, ΔE* was significantly higher in ScS-HF sample than ScS-LF leaves, showing values about 4-fold upper (

Figure 3A). The trend after 9 days of storage was almost the same, while an increment of ΔE* was recorded in ScS-LF rocket leaves at 12

th and 16

th day, with no statistical differences among treatments. Regards to hue angle, a slight decrease was recorded along the entire storage period, with no statistical differences among the fertilization treatments, showing rocket leaves more yellowish compared to the ones at harvest (

Table 4). These results are consistent with [

44], who demonstrated that lower hue angle values are correlated to the increase in leaf yellowing.

Results on ΔE* were confirmed by the YI that verified the loss of green colour of rocket leaves along the storage time (

Figure 3B). In particular, YI recorded a gradual increase for both the fertilization treatment during the storage time and showed the highest value (77.5 ± 2.9) in ScS-HF samples at day 9. Until the end of storage period, YI values continued to increase with no statistical differences among treatments (

Figure 3B). As regards the HC2, ΔE* and hue angle were influenced only by the storage time, while YI was affected also by the fertilization program (

Table 4). ScS-HF samples showed mean values of YI higher (of about 2.5 %) compared to ScS-LF rocket leaves (70.2 ± 1.2). All the results on colour parameters of rocket leaves cultivated in ScS during both harvest cuts support the hypothesis that higher fertilization could cause a more rapid loss of colour than lower strategies, underlining the importance of an adequate nutrition to obtain rocket leaves with optimum quality [

20,

45].

As for rocket leaves cultivated on SbS, results from the multifactor ANOVA showed that all colour parameters of rocket leaves were only affected by the storage time for both harvest cuts (

Table 4). In detail, the storage time caused an increase of ΔE and YI values and a decrease of hue angle in the HC1 and the HC2, confirming a gradual yellowing of rocket leaves (data not shown).

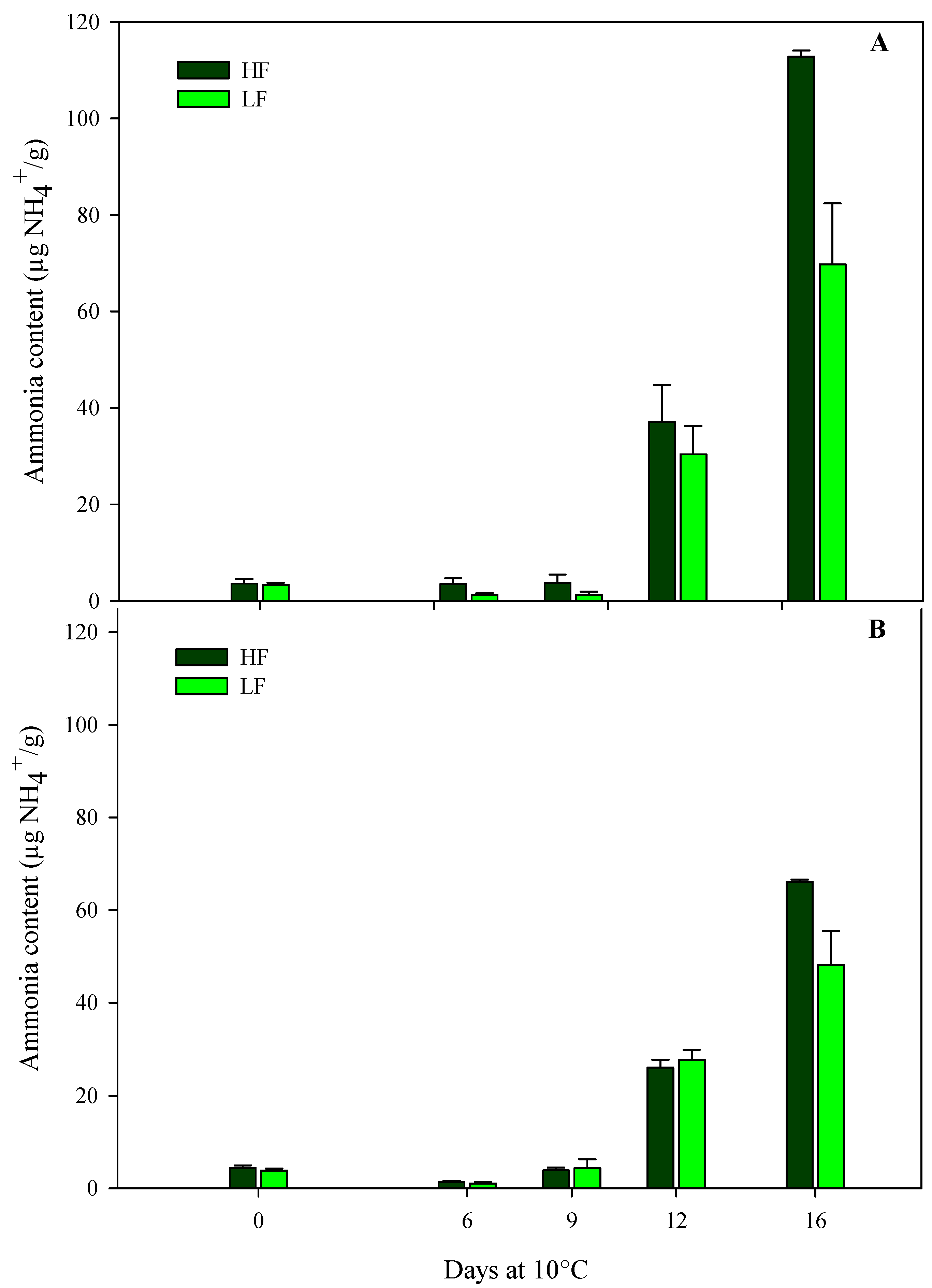

3.2.2. Ammonia content, electrolyte leakage and dry matter

Results from the sensory VQ were confirmed by the physiological parameters (ammonia content, electrolyte leakage and dry matter). As regards the ammonia content, in both harvest cuts of rocket leaves obtained by ScS, it was influenced by all factors (fertilization program, storage time and their interaction) (

Table 4). In detail, ammonia started to accumulate at the 12

th day of storage and reached higher values in ScS-HF samples than in ScS-LF, at the end of storage time in both harvest cuts (

Figure 4). While in rocket cultivated on S, the ammonia content was only affected by the storage time in both harvest cuts (

Table 4). These differences among fertilization treatments were confirmed by data on chlorophyll degradation reported below. Indeed, chlorophyll loss during the postharvest storage may cause ammonia accumulation because chlorophyll catabolism induces the degradation of apoproteins by protease and remobilization of the nitrogen of the chlorophyll apoproteins [

46]. Additionally, result on ammonia content is in agreement with the hue angle values observed during the storage and suggests the existence of correlation between these two parameters in leafy vegetables [

47]. The ammonia content is considered an objective indicator of the quality and marketability of leafy vegetables [

48], and, in the present study, it well discriminated the marketable samples from the non-marketable ones (

Figure 4). Ammonia accumulation in vegetable tissues is associated with the senescence of the leaves and high concentrations of this component are responsible of tissue damages which lead to the senescence and a negative impact on the overall quality of the product. Moreover, in minimally processed foods, like green leafy vegetables, injuries occurred during postharvest handlings activate degradation processes like proteolysis causing the release and accumulation of ammonia [

12,

49].

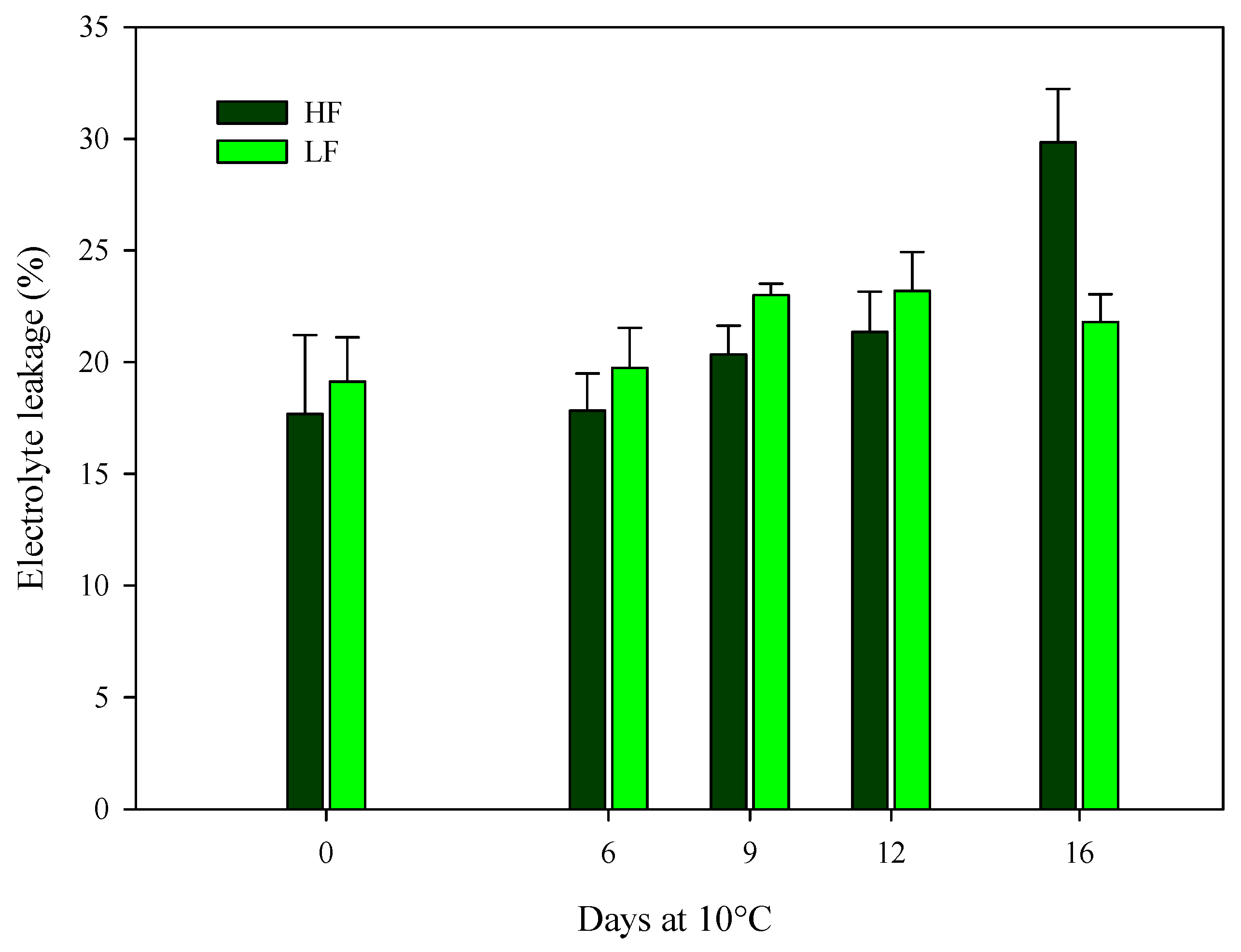

The findings on ammonia content are in agreement with the ones recorded on electrolyte leakage, which indicates the cell membrane integrity. On samples cultivated in ScS, the electrolyte leakage was only affected by the fertilization program and the storage time in HC1 and by all factors (fertilization program, storage time and their interaction) in HC2 (

Table 4). Considering the HC1, higher significant values were observed in ScS-HF fresh-cut rocket leaves (22.9 ± 2.4 %) compared to ScS-LF samples (18.4 ± 1.1 %). In the HC2, the values of electrolyte leakage were almost constant along the entire storage time for ScS-LF samples, while the ScS-HF leaves showed highest value at the end of storage (29.8 ± 2.4 %) (

Figure 5). The electrolyte leakage is strictly related to the quality and shelf life of fresh-cut leafy vegetables and it is commonly considered to measure the integrity of cell membranes damaged by oxidative stresses in fresh-cut tissues [

12,

50]. Since the electrolyte leakage can be considered another indirect measure of plant senescence, expressed as integrity of cell membrane [

27], results indicate a positive effect of the ScS-LF strategy in the reduction of membrane damages during the postharvest storage. Similar results were reported by [

12] on fresh-cut rocket leaves where the percentage increase of electrolyte leakage along the storage on soil system was higher than the one detected on soilless system, pointing out that soilless system was more efficient in terms of reduction of induced oxidative stresses on cell membranes.

From the ANOVA results on rocket cultivated on SbS, the electrolyte leakage was affected only by the storage time in both harvest cuts (

Table 4), showing a gradual increase along the postharvest phase (data not shown). The findings on ammonia content and electrolyte leakage on rocket leaves cultivated in SbS and ScS suggest the higher efficiency of the soilless approach than the soil one in controlling mineral nutrition of vegetables [

51]. In this research paper, rocket leaves cultivated in ScS showed better qualitative performances for the postharvest storage than those in SbS, as indicated by the lower values of ammonia content and electrolyte leakage recorded at the end of storage in samples grown in ScS.

The results about electrolyte leakage are confirmed by dry matter values, as reported in

Table 4. In the HC1 of ScS, dry matter content was affected by fertilization program. In detail, ScS-LF samples had higher value (+ 21,8 %) of dry matter than ScS-HF leaves (11.60 ± 1.24 %). It is well documented that higher levels of fertilization, and especially excesses of nitrogen, contribute significantly to the vegetable overgrowth and biomass development, but also to the reduction of the dry matter content [

52,

53]. This parameter plays an important role in the sensory VQ and consumer acceptability of leafy vegetables as it gives mechanical strength to vegetable tissues. Additionally, these results on dry matter confirmed the results obtained on respiration rate: rocket leaves with high dry matter content showed higher respiration rate than the ones with lower dry matter [

42].

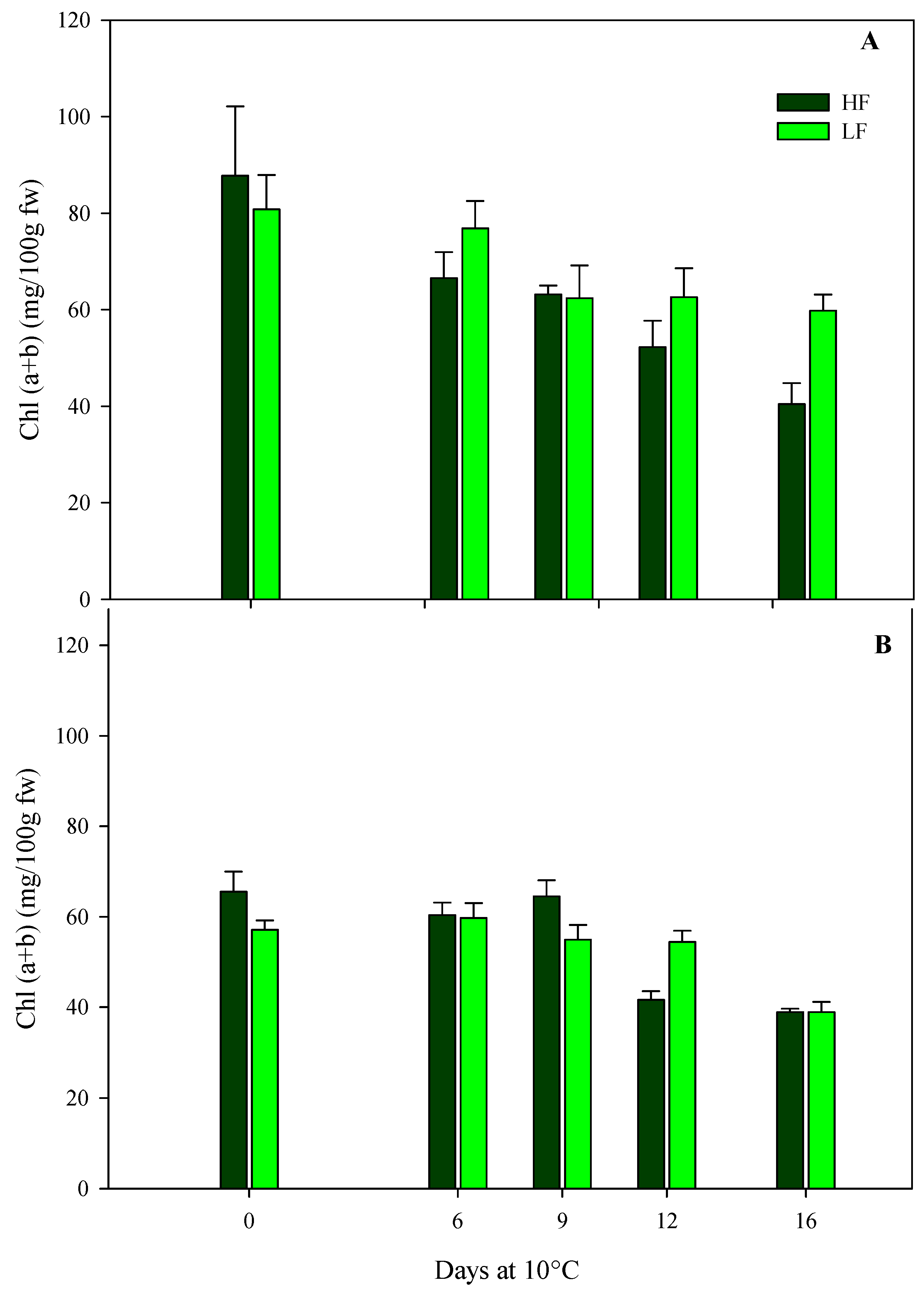

3.2.3. Chlorophyll content, antioxidant activity and total phenols

Total chlorophyll content of rocket leaves confirmed results from sensory and colour parameters. In general, in leafy vegetables, the loss of the green colour during the postharvest storage through chlorophyll breakdown is one of the most important qualitative traits that influences the shelf-life [

12]. As for samples obtained by ScS, in the case of HC1, the initial chlorophyll content was about 84.29 (± 10.73) mg/100g fw, with no statistical differences among treatments (

Figure 6A). During the storage, the chlorophyll values had a significant reduction in HF and LF treatments. In particular, at the end of the storage, ScS-HF leaves showed a reduction of chlorophyll content, reaching 2-fold fall compared to fresh samples; instead, in ScS-LF rocket leaves its values decreased until the 9th day and, after, it remained almost constant until the end of the storage (

Figure 6A). In the subsequent harvest cut (HC2), the initial chlorophyll content in both ScS-HF and ScS-LF samples was lower than the one measured in HC1 (-32 %) and it remained almost the same until the 9

th day, without significant differences between fertilization treatment (

Figure 6B). At 12 days, the lowest value was recorded in ScS-HF samples (41.65 ± 1.91 mg/100g fw), while only at 16 days a reduction of this parameter was recorded for ScS-LF rocket leaves. These results are in agreement with the ones obtained on ammonia content.

In SbS, the chlorophyll content of rocket leaves was not influenced by the fertilization treatments, but only by the storage time in both harvest cuts (

Table 4), showing a significant reduction along the postharvest phase as a consequence of the senescence of leaves (data not shown).

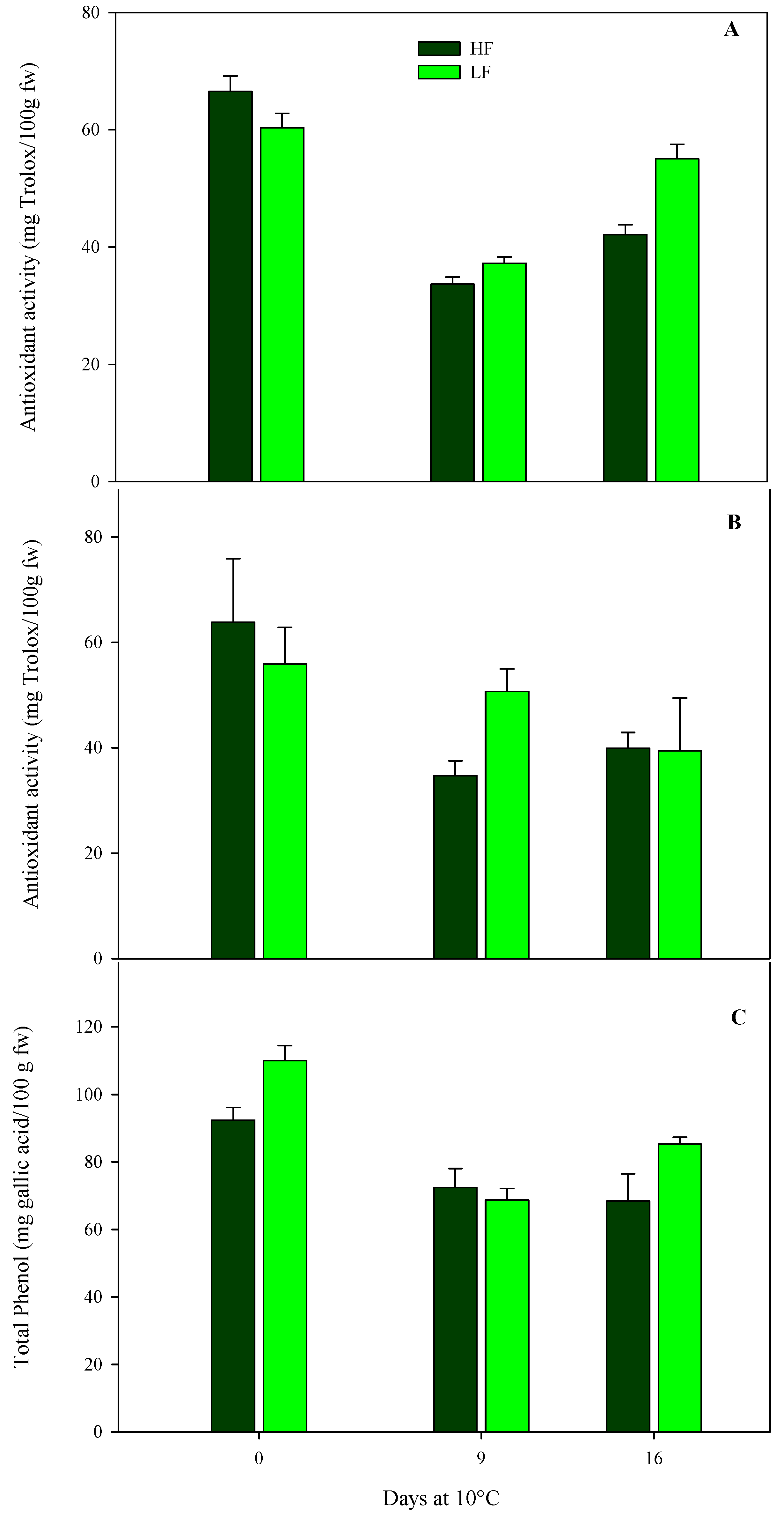

As for chemical parameters in rocket leaves cultivated on ScS, antioxidant activity was significantly affected by all factors in both harvest cuts, while the total phenols content was influenced by all factors in HC1 and only by the storage time in HC2 cut (

Table 4). In detail, the initial antioxidant activity leaves content was about 61.6 (± 6.0) mg Trolox/100g fw in both harvest cuts, with no statistical differences among fertilization treatments (

Figure 7). Subsequently, in the HC1, the antioxidant activity recorded the highest value in ScS-LF rocket leaves (55.1 ± 2.5 mg Trolox/100g fw) at the end of storage (

Figure 7A). As for the HC2, comparing treatments at 9

th day, significant differences were observed between ScS-HF samples and ScS-LF ones, which showed the lowest (34.70 ± 2.83 mg Trolox/100g fw) and the highest (50.68 ± 4.29 mg Trolox/100g fw) values of antioxidant activity, respectively (

Figure 7B).

A similar trend was observed for total phenols content in the case of HC1 of ScS (

Figure 7C). The content at harvest was higher in ScS-LF rocket leaves than in ScS-HF samples and decreased in both treatments until the 9

th day, with no significant differences. At the end of storage, the highest value of total phenols was observed in ScS-LF leaves (85.30 ± 2.02 mg gallic acid/100g fw). These results prove the existence of a positive correlation between total phenols and antioxidant activity, as already reported on many fruit and vegetables [

29,

54,

55], confirming that phenols highly contribute to the antioxidant activity of the product.

In rocket leaves obtained with SbS, antioxidant activity was significantly influenced by the two factors (fertilization program and storage time) in the HC1, and only by the storage time in the HC2 (

Table 4). Comparing the fertilization treatments, in the HC1 differences were observed between SbS-HF (77.5 mg Trolox/100g fw) and SbS-LF samples (83.5 mg Trolox/100g fw). Finally, results obtained from the multifactor ANOVA showed that the total phenols content was affected only by the storage time in the HC1, while no significant influences were observed in the case of HC2 (

Table 4).

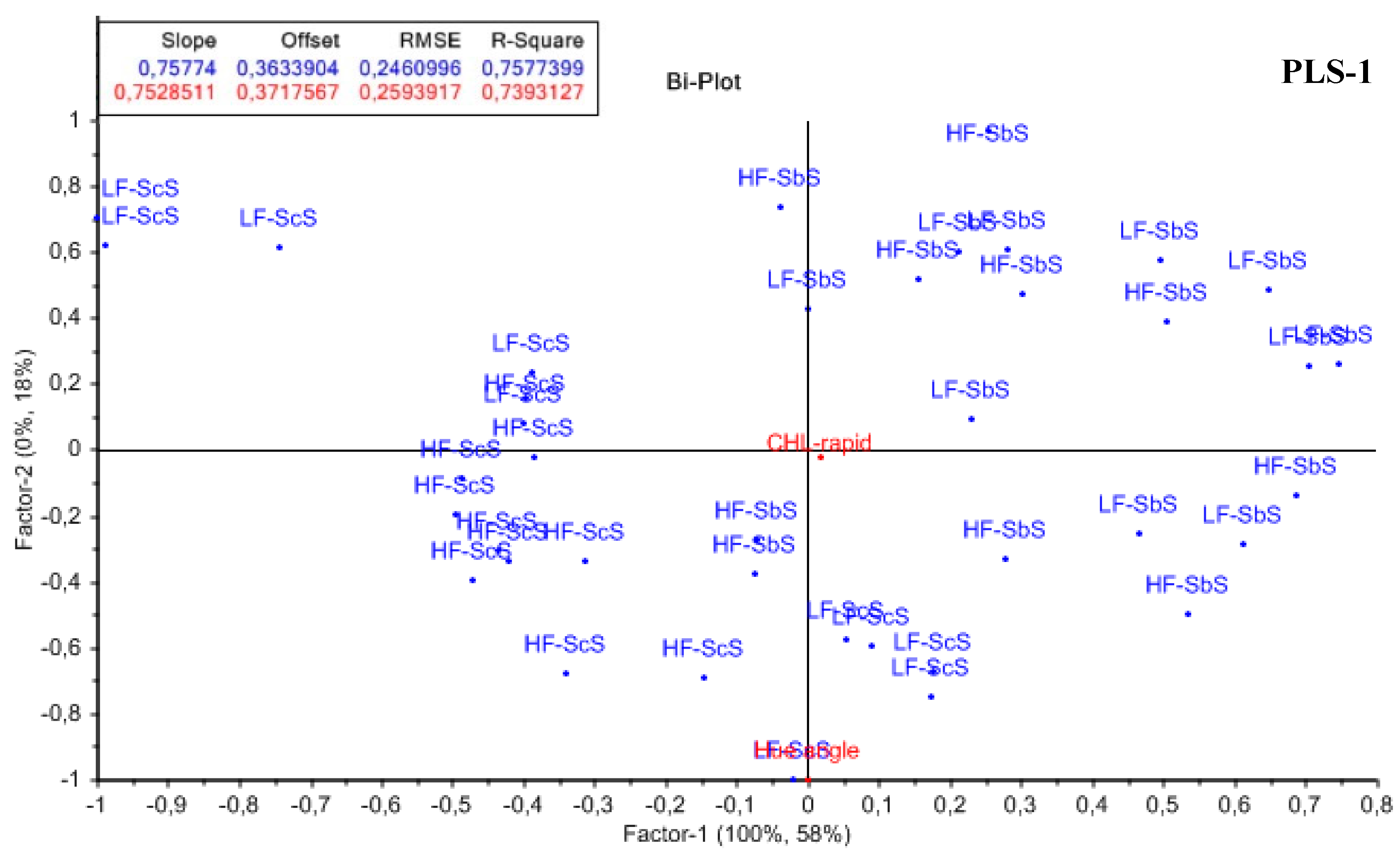

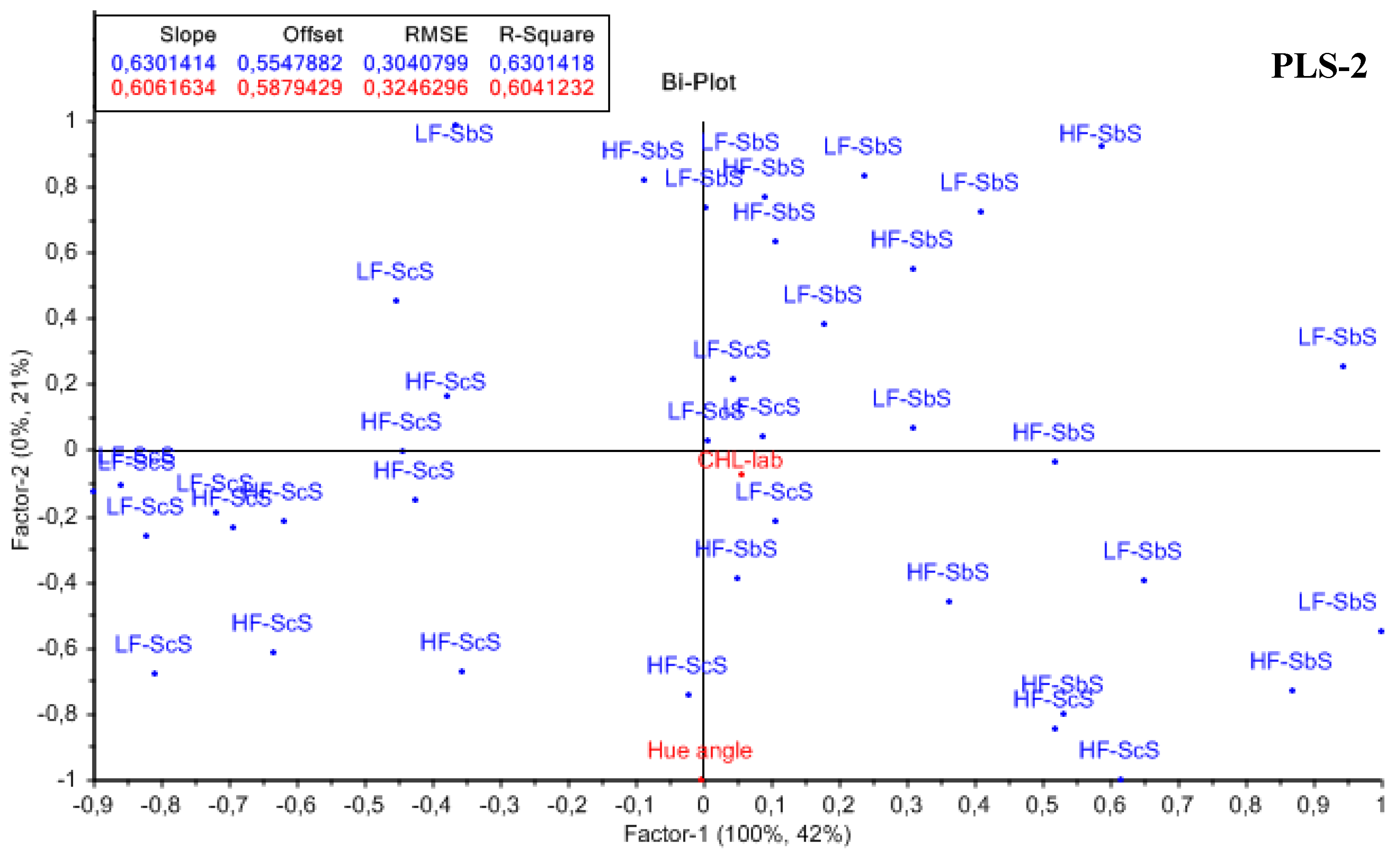

3.3. Prediction of cultivation system of rocket leaves by rapid and no-destructive tools

Two PLS model were built in order to predict the cultivation system. In the first PLS (PLS-1) the hue angle and the total chlorophyll measured using the no-destructive tool were considered as predictors. In the second PLS (PLS-2) the x variables were the hue angle and the total chlorophyll measured using the analytic method.

Both PLS were able to discriminate the cultivation system, in calibration and validation, with R

2 value of 0.7 and 0.6 for PLS-1 and PLS-2, respectively (

Figure 8). The PLS-1 outperformed the second since the no-destructive method used allowed to make more measurements for each replication, that were more than the replications used in the analytical method. This is due to the rapidity of the analysis that allowed to analyze more samples, catching all the variability present among samples. The possibility of giving information about the cultivation system to the final users could be useful for the growing awareness of modern consumers toward the economic, social, and environmental sustainability of production processes. Moreover, it represents another information, that might influence the purchase, since consumers are increasingly interested in knowing the history of the product. On the other hand, the cultivation system can affect some nutritional aspects and the quality of the product at hand.

4. Conclusions

Soilless system (ScS) allowed a better optimization of water use, with only slight differences with reference to the fertilization program adopted, since it is possible to detect conditions of excessive water supply by simple measurements of leaching volumes and subsequent adjustments of irrigation scheduling. Moreover, the analysis of partial factor productivity of fertilizers (PFP) has always been by far higher in the case of low fertilization input (LF) treatments, both in SbS and in ScS, allowing for both excellent production levels and more sustainable management of nutrients.

Postharvest qualitative analysis confirmed the efficiency of LF treatment applied in ScS. In particular, lower accumulation in ammonia and a reduced electrolyte leakage was measured in LF-ScS rocket leaves, meaning a higher quality than HF treatment. These findings were also confirmed by the measured of the sensory parameters and chlorophyll analysis.

In conclusion, LF treatment applied to ScS resulted a more environmentally sustainable approach with positive effects also on postharvest quality of fresh-cut rocket leaves.

Finally, data obtained by the present research allowed to build a PLS model able to predict the product history, in this case the cultivation system, starting from the no-destructive analysis of total chlorophyll. This last result might be a valid tool to give additional information to the users (consumers, logistics operators) regarding the cultivation technique used for wild rocket.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., B.P., F.S. and F.F.M..; crop performance and plant growth measurements, L.B., F.S. and F.F.M.; post-harvest measurements, M.P., M.C., B.P.; formal analysis, M.P. and L.B.; statistical analysis, M.P, M.C., F.F.M. and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., M.C. and F.F.M.; writing—review and editing, M.C., B.P., M.P., F.S. and F.F.M.; supervision, F.S., F.F.M., M.C. and B.P.; project administration, M.C. and F.S.; funding acquisition, M.C., F.S., B.P. and F.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project Prin 2017 “SUS&LOW-Sustaining low-impact practices in horticulture through non-destructive approach to provide more information on fresh produce history and quality” (grant number: 201785Z5H9) from the Italian Ministry of Education University.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicola Gentile and Massimo Franchi for the technical support and Marinella Cavallo and Giuseppe Panzarini for the administrative support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

-

Good Agricultural Pratices for Greenhouse Vegetable Crops: Principles for Mediterranean Climate Areas; FAO, Ed.; FAO plant production and protection paper; FAO: Rome, 2013; ISBN 978-92-5-107649-1.

- Torrellas, M.; Antón, A.; Ruijs, M.; García Victoria, N.; Stanghellini, C.; Montero, J.I. Environmental and Economic Assessment of Protected Crops in Four European Scenarios. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 28, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanghellini, C. Horticultural production in greenhouses: efficient use of water. Acta Hortic. 2014, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, F.F.; Serio, F.; Mininni, C.; Signore, A.; Parente, A.; Santamaria, P. Tensiometer-Based Irrigation Management of Subirrigated Soilless Tomato: Effects of Substrate Matric Potential Control on Crop Performance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesano, F.F.; Van Iersel, M.W.; Boari, F.; Cantore, V.; D’Amato, G.; Parente, A. Sensor-Based Irrigation Management of Soilless Basil Using a New Smart Irrigation System: Effects of Set-Point on Plant Physiological Responses and Crop Performance. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 203, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, D.; Magán, J.J.; Montesano, F.F.; Tzortzakis, N. Minimizing Water and Nutrient Losses from Soilless Cropping in Southern Europe. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gioia, F.; Avato, P.; Serio, F.; Argentieri, M.P. Glucosinolate Profile of Eruca Sativa, Diplotaxis Tenuifolia and Diplotaxis Erucoides Grown in Soil and Soilless Systems. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 69, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.B.; Incrocci, L.; Van Ruijven, J.; Massa, D. Reducing Contamination of Water Bodies from European Vegetable Production Systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 240, 106258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.B.; Martínez-Gaitan, C.; Gallardo, M.; Giménez, C.; Fernández, M.D. Identification of Irrigation and N Management Practices That Contribute to Nitrate Leaching Loss from an Intensive Vegetable Production System by Use of a Comprehensive Survey. Agric. Water Manag. 2007, 89, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefola, M.; Pace, B. Application of Oxalic Acid to Preserve the Overall Quality of Rocket and Baby Spinach Leaves during Storage: Oxalic Acid Postharvest Treatment. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 2523–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiattone, M.I.; Candido, V.; Cantore, V.; Montesano, F.F.; Boari, F. Water Use and Crop Performance of Two Wild Rocket Genotypes under Salinity Conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 194, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, M.; Pace, B.; Cefola, M.; Montesano, F.F.; Colelli, G.; Attolico, G. Non-Destructive and Contactless Estimation of Chlorophyll and Ammonia Contents in Packaged Fresh-Cut Rocket Leaves by a Computer Vision System. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 189, 111910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukounaras, A.; Siomos, A.S.; Sfakiotakis, E. Postharvest CO2 and Ethylene Production and Quality of Rocket (Eruca Sativa Mill.) Leaves as Affected by Leaf Age and Storage Temperature. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 46, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R. Nutritional and Energetic Value of Eruca Sativa Mill. Leaves. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2015, 14, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria, P.; Elia, A.; Serio, F.; Todaro, E. A Survey of Nitrate and Oxalate Content in Fresh Vegetables. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1999, 79, 1882–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y. Leafy, Floral and Succulent Vegetables. In Postharvest Physiology and Pathology of Vegetables; Bartz, J.A. and Brecht, J.K.: Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, 2003; pp. 599–623.

- Siomos, A.S.; Koukounaras, A. Quality and Postharvest Physiology of Rocket Leaves. Fresh Prod. 2007, 1, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Koukounaras, A.; Siomos, A.S.; Sfakiotakis, E. Impact of Heat Treatment on Ethylene Production and Yellowing of Modified Atmosphere Packaged Rocket Leaves. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009, 54, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonasia, A.; Lazzizera, C.; Elia, A.; Conversa, G. Nutritional, Biophysical and Physiological Characteristics of Wild Rocket Genotypes As Affected by Soilless Cultivation System, Salinity Level of Nutrient Solution and Growing Period. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonasia, A.; Conversa, G.; Lazzizera, C.; Elia, A. Post-Harvest Performance of Ready-to-Eat Wild Rocket Salad as Affected by Growing Period, Soilless Cultivation System and Genotype. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 156, 110909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadafora, N.D.; Cocetta, G.; Ferrante, A.; Herbert, R.J.; Dimitrova, S.; Davoli, D.; Fernández, M.; Patterson, V.; Vozel, T.; Amarysti, C.; et al. Short-Term Post-Harvest Stress That Affects Profiles of Volatile Organic Compounds and Gene Expression in Rocket Salad during Early Post-Harvest Senescence. Plants 2019, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villani, A.; Loi, M.; Serio, F.; Montesano, F.F.; D’Imperio, M.; De Leonardis, S.; Mulè, G.; Paciolla, C. Changes in Antioxidant Metabolism and Plant Growth of Wild Rocket Diplotaxis Tenuifolia (L.) DC Cv Dallas Leaves as Affected by Different Nutrient Supply Levels and Growing Systems. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 4115–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobermann, A. Nutrient Use Efficiency – Measurement and Management. In Fertilizer best management practices: general principles, strategy for their adoption and voluntary initiatives versus regulations; Krauss, A., Isherwood, K., Heffer, P.: International Fertilizer Industry Association, Paris, 2007; pp. 1–28.

- Palumbo, M.; Pace, B.; Cefola, M.; Montesano, F.F.; Serio, F.; Colelli, G.; Attolico, G. Self-Configuring CVS to Discriminate Rocket Leaves According to Cultivation Practices and to Correctly Attribute Visual Quality Level. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, A.A. Methods of Gas Mixing, Sampling and Analysis. In Postharvest Technology of Horticultural Crops; Kader, A.A.: University of California, Berkeley, 1992; Vol. 3311, pp. 93–95.

- Fadda, A.; Pace, B.; Angioni, A.; Barberis, A.; Cefola, M. Suitability for Ready-to-Eat Processing and Preservation of Six Green and Red Baby Leaves Cultivars and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Value during Storage and after the Expiration Date: Ready-to-Eat Baby Leaves Cultivars. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2016, 40, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Tudela, J.A.; Luna, C.; Allende, A.; Gil, M.I. Low Oxygen Levels and Light Exposure Affect Quality of Fresh-Cut Romaine Lettuce. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 59, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L.; Al-Said, F.A.-J. Colour Measurement and Analysis in Fresh and Processed Foods: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, M.; D’Imperio, M.; Tucci, V.; Cefola, M.; Pace, B.; Santamaria, P.; Parente, A.; Montesano, F.F. Sensor-Based Irrigation Reduces Water Consumption without Compromising Yield and Postharvest Quality of Soilless Green Bean. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefola, M.; Pace, B.; Sergio, L.; Baruzzi, F.; Gatto, M.A.; Carito, A.; Linsalata, V.; Cascarano, N.A.; Di Venere, D. Postharvest Performance of Fresh-Cut ‘Big Top’ Nectarine as Affected by Dipping in Chemical Preservatives and Packaging in Modified Atmosphere. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The Spectral Determination of Chlorophylls a and b, as Well as Total Carotenoids, Using Various Solvents with Spectrophotometers of Different Resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzano, V.; Parente, A.; Serio, F.; Santamaria, P. Effect of Growing System and Cultivar on Yield and Water-Use Efficiency of Greenhouse-Grown Tomato. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2008, 83, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, P.; Elia, A.; Serio, F. Effect of solution nitrogen concentration on yield, leaf element content, and water and nitrogen use efficiency of three hydroponically-grown rocket salad genotypes. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiattone, M.I.; Viggiani, R.; Di Venere, D.; Sergio, L.; Cantore, V.; Todorovic, M.; Perniola, M.; Candido, V. Impact of Irrigation Regime and Nitrogen Rate on Yield, Quality and Water Use Efficiency of Wild Rocket under Greenhouse Conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 229, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiattone, M.I.; Boari, F.; Cantore, V.; Castronuovo, D.; Denora, M.; Di Venere, D.; Perniola, M.; Sergio, L.; Todorovic, M.; Candido, V. Effect of Water Regime, Nitrogen Level and Biostimulants Application on Yield and Quality Traits of Wild Rocket [Diplotaxis Tenuifolia (L.) DC.]. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 277, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mola, I.; Ottaiano, L.; Cozzolino, E.; Senatore, M.; Giordano, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; Sacco, A.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Mori, M. Plant-Based Biostimulants Influence the Agronomical, Physiological, and Qualitative Responses of Baby Rocket Leaves under Diverse Nitrogen Conditions. Plants 2019, 8, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitousek, P.M.; Naylor, R.; Crews, T.; David, M.B.; Drinkwater, L.E.; Holland, E.; Johnes, P.J.; Katzenberger, J.; Martinelli, L.A.; Matson, P.A.; et al. Nutrient Imbalances in Agricultural Development. Science 2009, 324, 1519–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, D.M.; Toivonen, P.M.A. Quality of Fresh-Cut Fruits and Vegetables as Affected by Exposure to Abiotic Stress. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008, 48, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenigsbuch, D.; Ovadia, A.; Shahar-Ivanova, Y.; Chalupowicz, D.; Maurer, D. “Rock-Ad”, a New Wild Rocket (Diplotaxis Tenuifolia) Mutant with Late Flowering and Delayed Postharvest Senescence. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 174, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Marín, A.; Llorach, R.; Ferreres, F.; Gil, M.I. Controlled Atmosphere Preserves Quality and Phytonutrients in Wild Rocket (Diplotaxis Tenuifolia). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2006, 40, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, A.; Kjær, A.; Edelenbos, M. Volatile Organic Compounds as Markers of Quality Changes during the Storage of Wild Rocket. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seefeldt, H.F.; Løkke, M.M.; Edelenbos, M. Effect of Variety and Harvest Time on Respiration Rate of Broccoli Florets and Wild Rocket Salad Using a Novel O2 Sensor. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 69, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, A.C.; Gutiérrez, D.R.; Rodríguez, S.D.C. Influence of Passive and Active Modified Atmosphere Packaging on Yellowing and Chlorophyll Degrading Enzymes Activity in Fresh-Cut Rocket Leaves. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 26, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerzhijin, S.; Makino, Y.; Hirai, M.Y.; Sotome, I.; Yoshimura, M. Effect of Perforation-Mediated Modified Atmosphere Packaging on the Quality and Bioactive Compounds of Soft Kale (Brassica Oleracea L. Convar. Acephala (DC) Alef. Var. Sabellica L.) during Storage. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 23, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conversa, G.; Bonasia, A.; Lazzizera, C.; Elia, A. Pre-harvest Nitrogen and Azoxystrobin Application Enhances Raw Product Quality and Post-harvest Shelf-life of Baby Spinach ( Spinacia Oleracea L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 3263–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, M.L.; Colelli, G.; Cantwell, M.I. Ammonia Accumulation in Plant Tissues: A Potentially Useful Indicator of Postharvest Physiological Stress. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1511–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrandrea, L.; Amodio, M.L.; Cantwell, M.I. Modeling Ammonia Accumulation and Color Changes of Arugula ( Diplotaxis Tenuifolia ) Leaves in Relation to Temperature, Storage Time and Cultivar. Acta Hortic. 2016, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudela, J.A.; Marín, A.; Garrido, Y.; Cantwell, M.; Medina-Martínez, M.S.; Gil, M.I. Off-Odour Development in Modified Atmosphere Packaged Baby Spinach Is an Unresolved Problem. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 75, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Yang, C.Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Lin, Y.; Shaw, J.-F. Characterization of Senescence-Associated Proteases in Postharvest Broccoli Florets. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2004, 42, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonasia, A.; Conversa, G.; Lazzizera, C.; Elia, A. Pre-Harvest Nitrogen and Azoxystrobin Application Enhances Postharvest Shelf-Life in Butterhead Lettuce. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 85, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, B.; Capotorto, I.; Gonnella, M.; Baruzzi, F.; Cefola, M. Influence of Soil and Soilless Agricultural Growing System on Postharvest Quality of Three Ready-to-Use Multi-Leaf Lettuce Cultivars. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2018, 353-362 Pages. [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, D.; Goodwin, I.; Jones, R. Minimal Nitrogen and Water Use in Horticulture: Effects on Quality and Content of Selected Nutrients. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, R.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Barański, M.; Hallmann, E.; Góralska-Walczak, R.; Kopczyńska, K.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Górski, J.; Leifert, C.; Rempelos, L.; et al. The Effect of Different Fertilization Regimes on Yield, Selected Nutrients, and Bioactive Compounds Profiles of Onion. Agronomy 2021, 11, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capotorto, I.; Innamorato, V.; Cefola, M.; Cervellieri, S.; Lippolis, V.; Longobardi, F.; Logrieco, A.F.; Pace, B. High CO2 Short-Term Treatment to Preserve Quality and Volatiles Profile of Fresh-Cut Artichokes during Cold Storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 160, 111056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefola, M.; Carbone, V.; Minasi, P.; Pace, B. Phenolic Profiles and Postharvest Quality Changes of Fresh-Cut Radicchio (Cichorium Intybus L.): Nutrient Value in Fresh vs. Stored Leaves. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 51, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Changes in respiration rate of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at two subsequent harvest-cut times during the growing cycle [harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B)], cultivated on soilless system (ScS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Changes in respiration rate of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at two subsequent harvest-cut times during the growing cycle [harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B)], cultivated on soilless system (ScS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Changes in sensory visual quality (VQ) scores of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at two subsequent harvest-cut times during the growing cycles [harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B)], cultivated on soilless system (ScS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. A 5 to 1 rating scale was considered, where 5 = very good, 4 = good, 3 = fair, 2 = poor, 1 = very poor. The score 3 represents the shelf-life limit, while a score of 2 is considered the limit of edibility. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Changes in sensory visual quality (VQ) scores of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at two subsequent harvest-cut times during the growing cycles [harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B)], cultivated on soilless system (ScS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. A 5 to 1 rating scale was considered, where 5 = very good, 4 = good, 3 = fair, 2 = poor, 1 = very poor. The score 3 represents the shelf-life limit, while a score of 2 is considered the limit of edibility. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 3.

ΔE* (A) and Yellowness index (B) of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at harvest cut 1 cultivated on soilless system (ScS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 3.

ΔE* (A) and Yellowness index (B) of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at harvest cut 1 cultivated on soilless system (ScS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Changes in ammonia content in the harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B) of fresh-cut rocket leaves cultivated on soilless system (ScS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Changes in ammonia content in the harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B) of fresh-cut rocket leaves cultivated on soilless system (ScS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Changes in electrolyte leakage of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at harvest cut 2 cultivated on soilless system (SS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Changes in electrolyte leakage of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at harvest cut 2 cultivated on soilless system (SS) treated with different fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 6.

Effect of fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) on total chlorophyll content of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at two subsequent harvest-cut times during the growing cycle [harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B)], cultivated on soilless system (ScS) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 6.

Effect of fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) on total chlorophyll content of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at two subsequent harvest-cut times during the growing cycle [harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B)], cultivated on soilless system (ScS) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 7.

Effect of fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) on antioxidant activity of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at two subsequent harvest-cut times during the growing cycle [harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B)], cultivated on soilless system (ScS) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C; Figure C reports changes in total phenols at HC1. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 7.

Effect of fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF) on antioxidant activity of fresh-cut rocket leaves sampled at two subsequent harvest-cut times during the growing cycle [harvest cut 1 (A) and 2 (B)], cultivated on soilless system (ScS) and stored for 16 days at 10 °C; Figure C reports changes in total phenols at HC1. Data are means of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Figure 8.

Two PLS models built to predict the cultivation system from hue angle and total chlorophyll content obtained with the rapid and no-destructive system (PLS-1) or conventional analytic method (PLS-2).

Figure 8.

Two PLS models built to predict the cultivation system from hue angle and total chlorophyll content obtained with the rapid and no-destructive system (PLS-1) or conventional analytic method (PLS-2).

Table 1.

Chemical and physical soil properties in soil–bound sector.

Table 1.

Chemical and physical soil properties in soil–bound sector.

| Soil properties |

Unit |

Value |

| Sand |

% |

24 |

| Silt |

% |

32 |

| Clay |

% |

44 |

| Total-CaCO3

|

% |

1.32 |

| Organic matter |

% |

1.08 |

| Organic carbon |

% |

0.99 |

| Total-N (Kjeldhal method) |

‰ |

1.06 |

| pH |

- |

7.8 |

| EC |

dS/m |

2.4 |

| Extractable K |

mg/kg BaCl2-TEA |

264 |

| Available-P2O5 (Olsen method) |

mg/kg |

98.7 |

| Cation exchange capacity |

meq/100 g |

34.5 |

Table 2.

Yield, dry matter, water use efficiency (WUE), N, K, P, Ca, and Mg partial factor productivity (PFP) and Leaf Chlorophyll content of rocket leaves cultivated on soilless cultivation system (ScS) with high-input (HF) or low-input (LF) of nutrients supplied as fertilizer solution.

Table 2.

Yield, dry matter, water use efficiency (WUE), N, K, P, Ca, and Mg partial factor productivity (PFP) and Leaf Chlorophyll content of rocket leaves cultivated on soilless cultivation system (ScS) with high-input (HF) or low-input (LF) of nutrients supplied as fertilizer solution.

| Treatment |

Yield |

Dry matter |

WUE |

N PFP |

K PFP |

P PFP |

Ca PFP |

Mg PFP |

Leaf Chlorophyll content |

| (g/pot) |

% |

(g/L) |

(g yield/g di nutrient supplied) |

µmole Chlorophyll/m2 (leaf surface) |

| LF |

412 |

7.9 |

34.7 |

226 |

203 |

1158 |

273 |

869 |

370 |

| HF |

458 |

8.7 |

33.1 |

158 |

141 |

1066 |

165 |

689 |

378 |

|

Significance(1)

|

*** |

*** |

** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

ns |

Table 3.

Yield, dry matter, water use efficiency (WUE), N partial factor productivity (PFP) and Leaf Chlorophyll content of rocket leaves cultivated on soil-bound system (SbS) with high-input (HF) or low-input (LF) of N fertilizer.

Table 3.

Yield, dry matter, water use efficiency (WUE), N partial factor productivity (PFP) and Leaf Chlorophyll content of rocket leaves cultivated on soil-bound system (SbS) with high-input (HF) or low-input (LF) of N fertilizer.

| Treatment |

Yield |

Dry matter |

WUE |

N PFP |

Leaf Chlorophyll content |

| (g/m2) |

% |

(g/L) |

(g yield/g di nutrient supplied) |

µmole Chlorophyll/m2 (leaf surface) |

| LF |

3909 |

9.3 |

11.9 |

186 |

435 |

| HF |

4265 |

9.7 |

13 |

102 |

454 |

|

Significance(1)

|

* |

* |

* |

*** |

ns |

Table 4.

Effects of fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF), storage time (0, 6, 9, 12 or 16 days) and their interaction on sensory, physical and chemical parameters of fresh-cut rocket leaves cultivated on soilless (ScS) or soil-bound (SbS) system sampled at two harvest cuts (HC1 and HC2) and stored at 10 °C.

Table 4.

Effects of fertilization programs (high-input, HF, or low-input, LF), storage time (0, 6, 9, 12 or 16 days) and their interaction on sensory, physical and chemical parameters of fresh-cut rocket leaves cultivated on soilless (ScS) or soil-bound (SbS) system sampled at two harvest cuts (HC1 and HC2) and stored at 10 °C.

| Parameters |

ScS |

SbS |

| HC 1 |

HC 2 |

HC 1 |

HC 2 |

| Fertilization program (A) |

Storage

time (B) |

A x B |

Fertilization program (A) |

Storage

time (B) |

A x B |

Fertilization program (A) |

Storage

time (B) |

A x B |

Fertilization program (A) |

Storage

time (B) |

A x B |

Respiration rate

(µmol CO2/kg s) |

** |

**** |

**** |

**** |

**** |

** |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

| Visual quality (5-1) |

ns |

**** |

*** |

* |

**** |

* |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

| ΔE* |

**** |

**** |

**** |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

| Hue angle (°) |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

| Yellowness Index |

ns |

**** |

* |

* |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

Ammonia content

(µg NH4+/g) |

** |

**** |

** |

** |

**** |

**** |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

| Electrolyte leakage (%) |

**** |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

**** |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

| Dry matter (%) |

**** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Total chlorophyll content (mg/100 g fw) |

*** |

**** |

** |

ns |

**** |

**** |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

Antioxidant activity

(mg Trolox/100 g fw) |

** |

**** |

**** |

ns |

*** |

* |

* |

**** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

Total phenols

(mg gallic acid/100 g fw) |

*** |

**** |

** |

ns |

*** |

ns |

ns |

**** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).