1. Introduction

Spodoptera frugiperda, a member of the family Noctuidae, is a highly destructive polyphagous and migratory pest native to tropical regions of the Western Hemisphere (Sagar et al. 2020; Nagoshi et al. 2022; Sparks 1979). Due to its strong flight capability, it has rapidly spread to more than 40 sub-Saharan African countries following its invasion of Nigeria in 2016 (Maruthadurai and Ramesh 2020). After its initial detection in Yunnan Province, China, in late 2018 (Sun et al. 2021; He et al. 2021; Xiao 2021), this insect expanded its range across 26 provinces by September 2019 (Wu et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2019). S. frugiperda exhibits high reproductive potential, environmental adaptability, explosive population growth, and rapid dispersal. Its host range includes over 300 plant species, with major economically important crops such as maize, rice, peanuts, soybeans, and alfalfa (Jiang et al. 2019; Cock et al. 2017). Genetic studies have identified two distinct biotypes, commonly designated as the rice and maize biotypes (Juárez et al. 2012), which despite their morphological similarity, both preferentially feed on maize (Dumas et al. 2015).

Currently, the management of S. frugiperda predominantly relies on chemical control (Johnnie and Hannalene 2022). However, intensive pesticide use has resulted in significant drawbacks, including residue accumulation, environmental pollution, and non-target effects on natural enemies (Moustafa et al. 2024). Furthermore, this pest has developed resistance to multiple insecticides, including parathion, trichlorfon, mevinphos, and permethrin (Yu et al. 2003). Compared with chemical pesticides, food attractants offer an efficient and eco-friendly alternative for pest control (Tait et al. 2021; Sosa et al. 2019). Although several sex pheromones of S. frugiperda have been characterized, practical food attractants remain scarce. The development of effective food attractants requires the identification of key odor cues for host recognition. In this study, we collected volatiles emitted by maize plants at four growth stages: seedling stage (SS), small trumpet stage (STS), flowering stage (FS) and milky stage (MS). We evaluated the behavioral preferences of S. frugiperda toward these volatiles and identified electrophysiologically active components using gas chromatography-electroantennogram detection (GC-EAD), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and single sensillum recording (SSR). Then, a Y-tube olfactometer was employed to verify the olfactory responses to these active compounds to identify critical host-recognition cues

In addition, understanding the pest preference for host plants at different growth stages is crucial for developing effective management strategies (Betancurt et al. 2023). However, few studies have examined the growth performance of S. frugiperda larvae on maize at different phenological stages, and the mechanism by which females assess host growth stages remains unclear. Therefore, we compared relative concentrations of key odor cues in different growth stages and evaluated the growth performance of S. frugiperda larvae on maize at these stages to assess how adult oviposition choices affect offspring survival. This study may provide a theoretical foundation for determining the optimal control period and developing food attractants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

S. frugiperda larvae were collected from corn fields around the Ezhou Experimental Base of the Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences (114° 39'E, 30° 23'N ) in June 2023. The larvae were individually reared in 24-well plates containing an artificial diet until pupation under laboratory conditions. Pupae were subsequently transferred to glass culture dishes and placed in an oviposition cage lined with wax paper. Adult moths were maintained at 26±1 °C with a 14:10 h (L:D) photoperiod and 60 ± 5% relative humidity in climate-controlled chambers. Adults were provided with 10% honey solution via cotton wicks, which were replaced daily. Egg masses were collected following oviposition and newly hatched 1st instar larvae from synchronized cohorts were used for subsequent experiments.

The artificial diet was prepared according to Li et al. (2019), consisting of soybean powder, yeast powder, wheat germ, ascorbic acid, benzoic acid, sodium benzoate, edible oil, agar, acetic acid, and purified water.

Corn plants (Zea mays cv. Zhengdan 958, supplied by Hefei Fengzhong Seed Industry) were cultivated to four growth stages: SS (3-4 leaf stage), STS (7-10 leaf stage), FS and MS.

2.2. Experimental Instruments

Electrophysiologic responses of insects were measured using a gas chromatography-electroantennogram detection (GC-EAD) system consisting of an Agilent 7820 GC (Agilent Technologies) and a Syntech IDAC-2 electroantennogram detector (Syntech Research), supplied by Tangshan Dinggan Technology Company. Plant volatile components were determined using a GC-MS system, specifically the RACE GC2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific from Shimadzu Corporation, Japan). Behavioral responses were assayed using a Y-tube olfactometer with a main trunk (Φ = 18 cm × 4 cm) and two arms (Φ = 14 cm × 4 cm) angled at 75. The arms were connected via Teflon tubing to an odor source bottle, a flowmeter, a filtration device, and an oil-free vacuum pump.

2.3. Collection of Volatiles from Maize

Volatile compounds were collected from maize plants at different growth stages using a dynamic headspace sampling system. The system consisted of a transparent glass collection chamber (Φ = 30 cm × 50cm) containing potted plants and two glass ports: one inlet equipped with an activated charcoal filter to purify incoming air and one outlet connected to a volatile collection trap.

The collection trap (Φ = 0.7 cm × 15 cm) was packed with 200 mg of Super Q adsorbent (80/100 mesh, Analytical Research Systems). Continuous sampling was performed for 15 hours at ambient temperature with a purified airflow maintained at 300 mL/min (optimized based on preliminary tests).

Following collection, trapped volatiles were eluted using 500 μL HPLC-grade n-hexane (Sigma-Aldrich). The eluate was immediately transferred to amber glass vials and stored at 4 °C until analysis (typically within 24 hours). All glassware was baked at 250 °C for 4 hours prior to use to minimize contamination.

2.4. Behavioral Bioassay of S. frugiperda

Behavioral responses of both male and female adults of S. frugiperda were assayed using the Y-tube olfactometer. All tests were conducted in a darkroom at 16:00 (4:00 PM) to coincide with the activity period of the insects. The Y-tube was positioned in a ventilated chamber, and two 1cm2 filter paper strips, each impregnated with volatile samples, were placed in the odor source bottle. Groups of 10 insects that had been subjected to 4 hours of darkness and starvation were introduced into the main trunk of the Y-tube simultaneously. After 45 minutes, the numbers of insects in each arm were recorded. Each volatile sample was tested 10 times. To minimize external interference, chamber ventilation was maintained, and all ambient light sources were turned off throughout the experiment. Between tests, the inner walls of the Y-shaped tube were cleaned with 75% ethanol and dried.

2.5. Oviposition Selectivity of S. frugiperda Females

The oviposition selection behavior of

S. frugiperda females on maize leaves at different growth stages was assessed using a two-choice assay (

Figure 1). The experimental setup consisted of two insect cages, each containing fresh maize leaves from different growth stages, connected by a transparent cylindrical tube. Each cage had its own supply of degreased cotton soaked in 10% honey solution, which was replenished daily.

Mated female S. frugiperda were obtained by pairing newly emerged in disposable cups provided with degreased cotton soaked in 10% honey solution. Once females began ovipositing in these cups, they were considered mated and used for the assay.

For each replicate, a mated female was released into the center of the transparent cylindrical tube connecting two cages. The female could then choose to enter one of the two cages, each containing maize leaves from a different growth stage. The leaves were trimmed and their bases submerged in water to prevent desiccation. Each female was observed for a set period, and then eggs were recorded. Egg masses deposited on the leaves (excluding those on the cage walls) were collected and quantified daily. The experiment was conducted with 20 replicates (n = 20 females).

2.6. Growth Performance of S. frugiperda Colonized on Maize at Different Growth Stages

Newly hatched S. frugiperda larvae were fed on maize leaves from the SS, STS, FS, and MS stages. Each growth stage was considered a treatment group, consisting of three replicates, each with 20 newly hatched larvae (total n = 60 per growth stage). Fresh leaves were replaced daily until pupation. The following parameters were recorded daily: developmental duration of each life stage, pupal duration, survival rate, larval body weight (measured on days 10 and 15), pupal weight, and pupation rate. Newly emerged healthy males and females were paired in a 1:1 ratio within disposable cups, and daily egg production and egg hatching rates were recorded.

2.7. GC-EAD and GC-MS Analysis of Volatile Compounds from Maize at Key Growth Stages

Electrophysiologically active volatiles from maize were identified by GC-EAD and GC-MS. Two glass capillaries (4–5 cm in length) filled with 0.9% sodium chloride solution were used as measuring electrodes and reference electrodes. Two clean silver wires (4.5 cm in length) served as electrode leads, with each wire inserted into one capillary. The assembled electrodes were secured to the measuring stage and reference pole of the PRG-3 electrode holder.

Antennae from newly emerged males of S. frugiperda were excised at the base, and the distal tip was slightly trimmed. The reference electrode of the PRG-3 setup was removed, and the antennal base was stabilized using surface tension from the saline solution. The antennal tip was connected to the measuring electrode under a stereomicroscope.

For volatile analysis, 3 μL of plant volatiles were injected into the gas chromatograph inlet. GC-EAD responses were recorded, and active peaks were identified by matching their retention times with electrophysiological responses. Compounds were tentatively identified using the NIST11 mass spectral library and confirmed by comparing retention times and mass spectra with those of authentic standards. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using GC-EAD 2014 v1.2.5 software.

2.8. SSR Validation of GC-EAD Results

The electrophysiologically active compounds identified through GC-EAD analysis were subsequently validated by SSR techniques. Newly emerged female S. frugiperda moths (24-48 h post-eclosion) were immobilized on glass slides using dental wax grooves under a stereomicroscope. The head and antennae were carefully positioned outside the groove while maintaining proper physiological conditions. The insect body was securely fixed to prevent movement. A reference electrode was inserted into the compound eye, and a recording electrode was positioned at the base of the antennal sensilla. An odor delivery system had its outlet tube positioned 1cm from the antenna. Test odorants (10 μL aliquots) were applied to filter paper strips (1 cm²) and presented at intervals of ≥ 30 to allow complete neuronal recovery between stimuli.

2.9. Olfactory Responses of Female S. frugiperda to Electrophysiologically Active Components

Behavioral responses of female S. frugiperda to the electrophysiologically active components were identified by the Y-tube olfactometer, with liquid paraffin used as the control. The test method was the same as 2.4.

2.10. Data Analysis

Behavioral preference assays of S. frugiperda were subjected to rigorous statistical evaluation employing Pearson's chi-square test (α = 0.05) implemented in SPSS Statistics. Developmental and reproductive performance metrics across different maize growth stages were analyzed through LSD test (P < 0.05). Electrophysiological waveforms recorded during SSR were processed using AutoSpike32. Neuronal responsiveness was quantified by comparing action potential frequencies in one-second epochs before and after stimulus administration. All graphical representations were generated using GraphPad Prism.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Bioassay of S. frugiperda

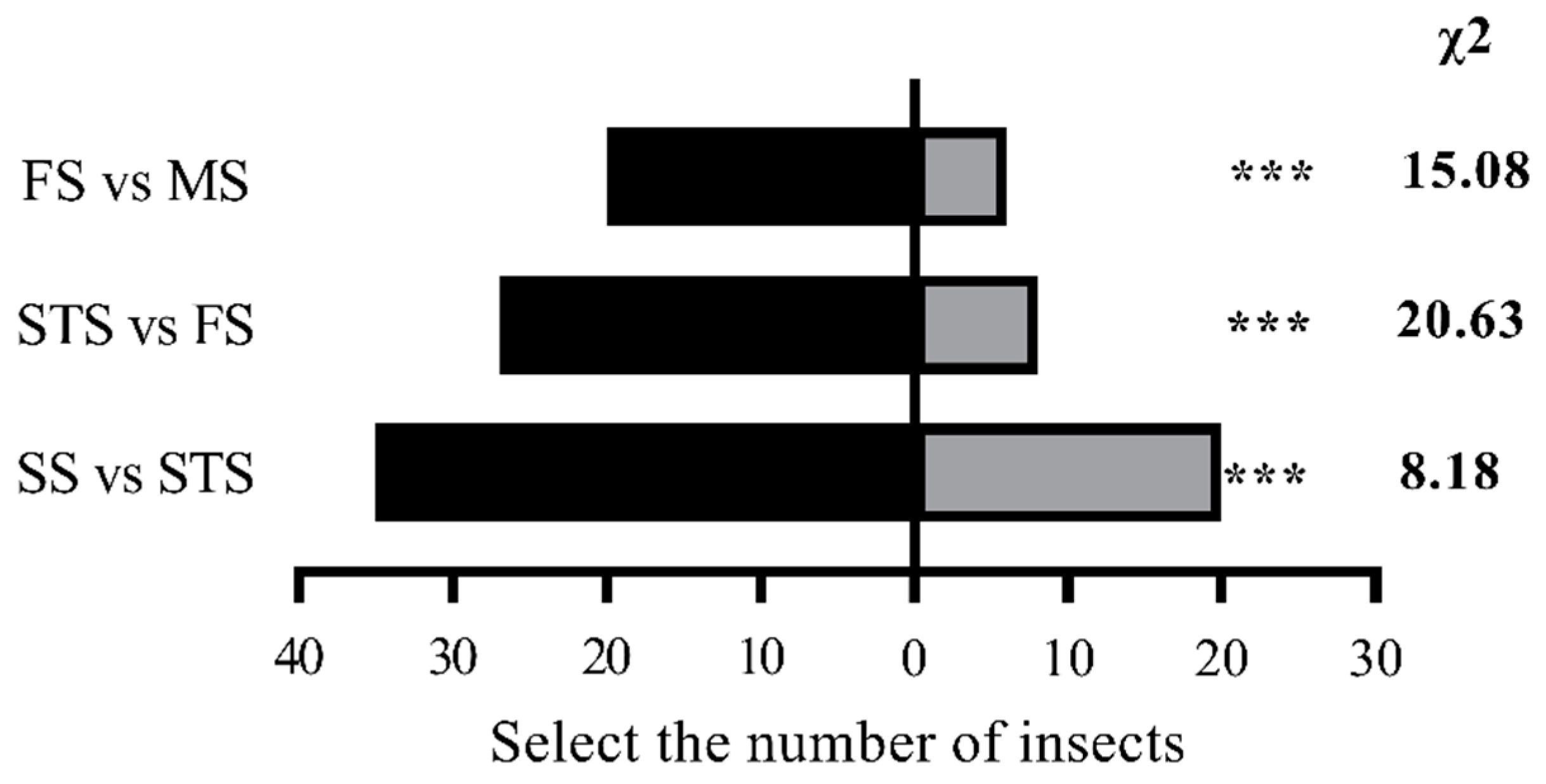

Female S. frugiperda exhibited a distinct preference hierarchy for maize volatiles across four growth stages: SS > STS > FS > MS. In pairwise comparisons using a Y-tube olfactometer, SS volatiles attracted significantly more females than STS volatiles (35 vs. 20; χ² = 8.18, P < 0.01). Similarly, FS volatiles were preferred over MS volatiles (20 vs. 6; χ² = 15.08, P < 0.01), and STS volatiles were more attractive than FS volatiles (27 vs. 8; χ² = 20.63, P < 0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Olfactory selection test of S. frugiperda female adults on maize volatiles at different growth stages. Note: In the histogram, * * * indicates a very significant difference ( P < 0.01 ) (chi-square test).

Figure 1.

Olfactory selection test of S. frugiperda female adults on maize volatiles at different growth stages. Note: In the histogram, * * * indicates a very significant difference ( P < 0.01 ) (chi-square test).

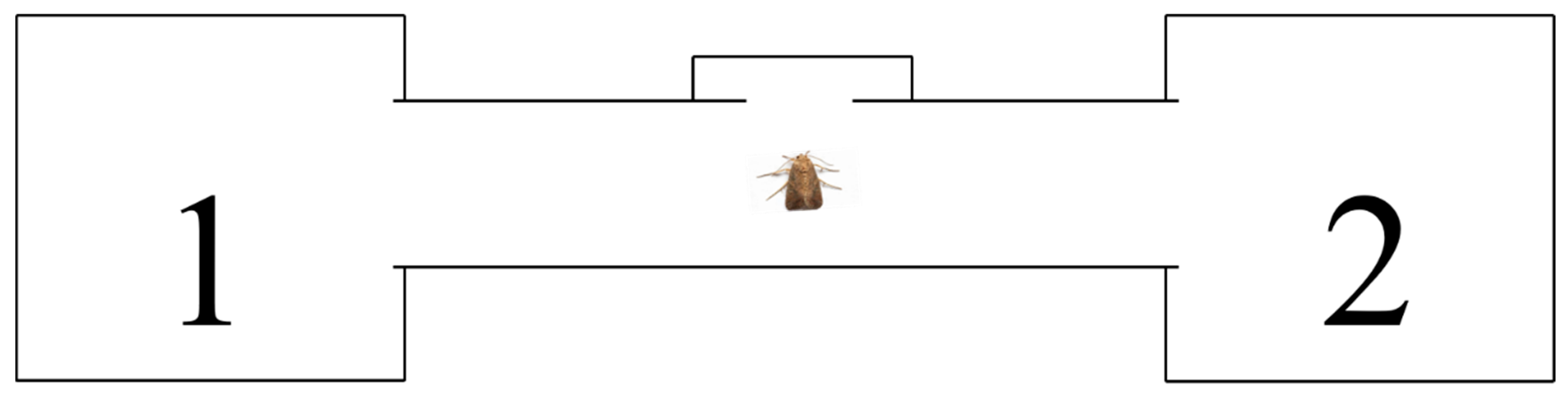

In contrast, male

S. frugiperda showed no significant preference for maize volatiles at different growth stages (P > 0.05) (

Figure 2).

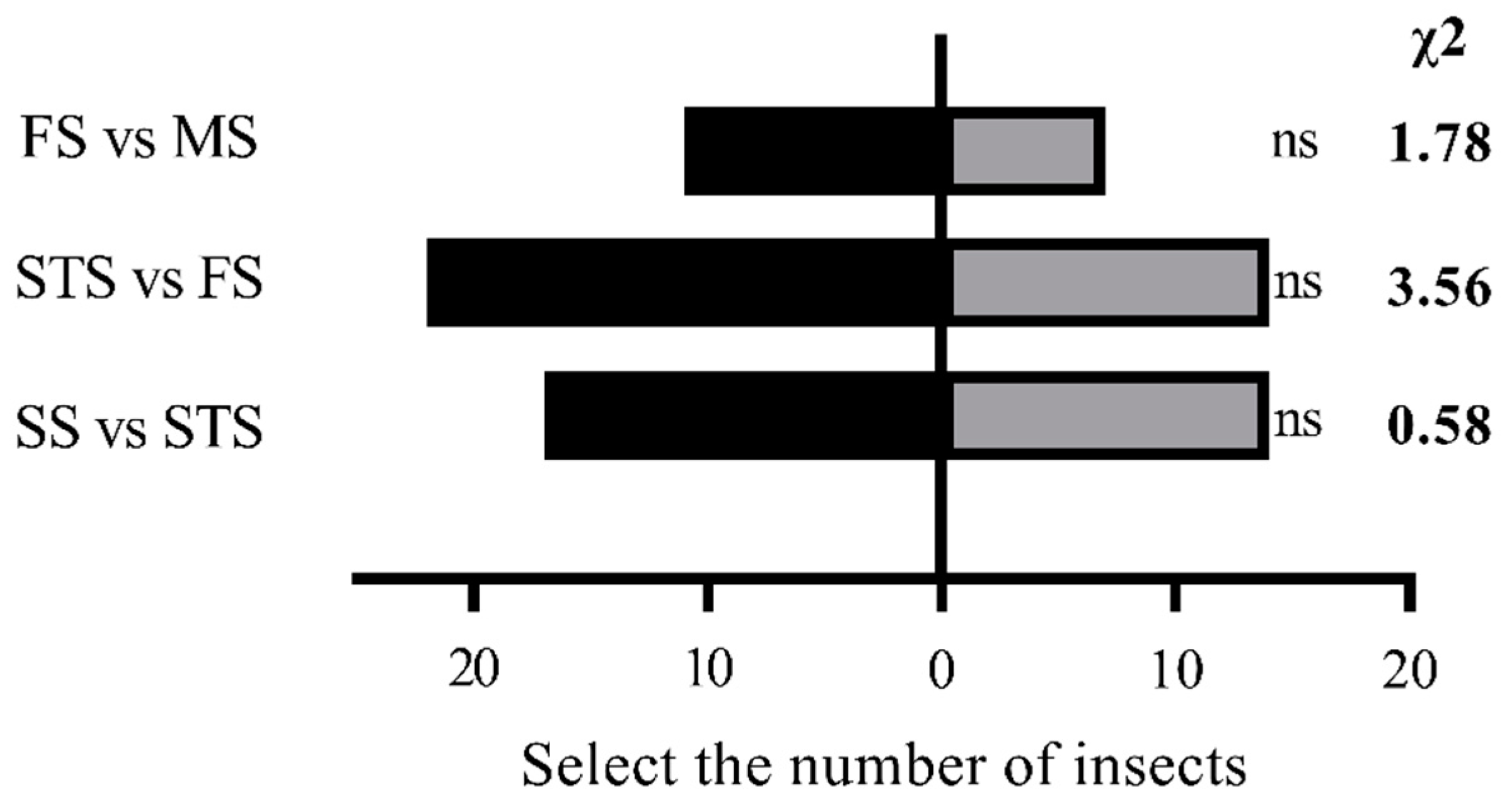

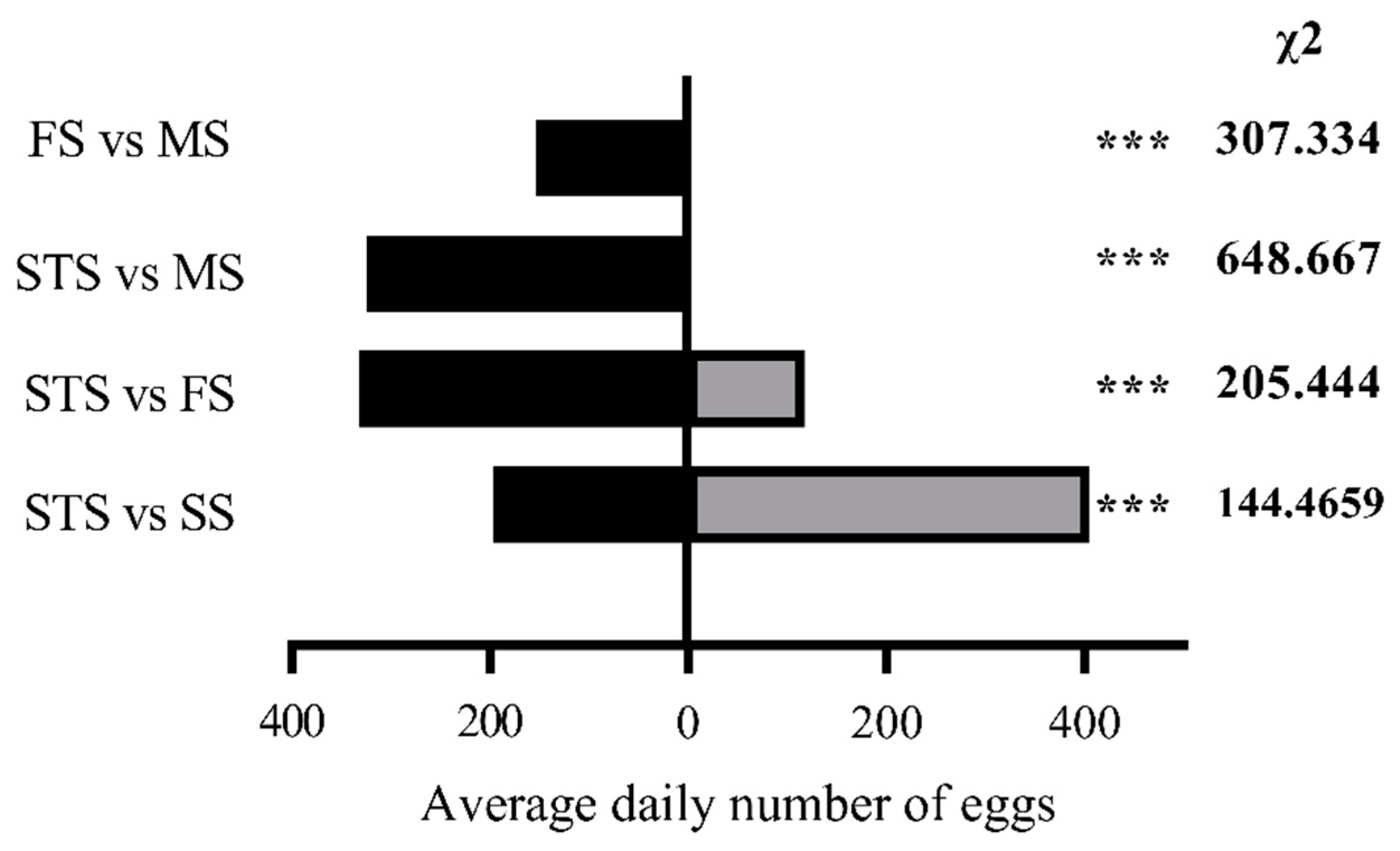

3.2. Oviposition Selectivity of Female S. frugiperda

Female

S. frugiperda showed a clear hierarchy in oviposition preference for maize at different growth stages: SS > STS > FS > MS (

Figure 3). In two-choice assays, the average number of eggs laid on SS leaves was significantly higher than on STS leaves ((405.2 vs 196.7; χ2 = 144.47, P < 0.01 ). Similarly, STS leaves were preferred over FS leaves (332.5 vs 117.5 eggs; χ² = 205.44, P < 0.01), and FS leaves over MS leaves (153.7 vs 0 eggs; χ²=307.33, p < 0.01). Notably, in comparisons between STS and MS leaves, no eggs were laid on MS leaves in any replicate (324.3 vs 0 eggs; χ² = 648.67, P < 0.01), demonstrating the strong preference for earlier growth stages, particularly SS.

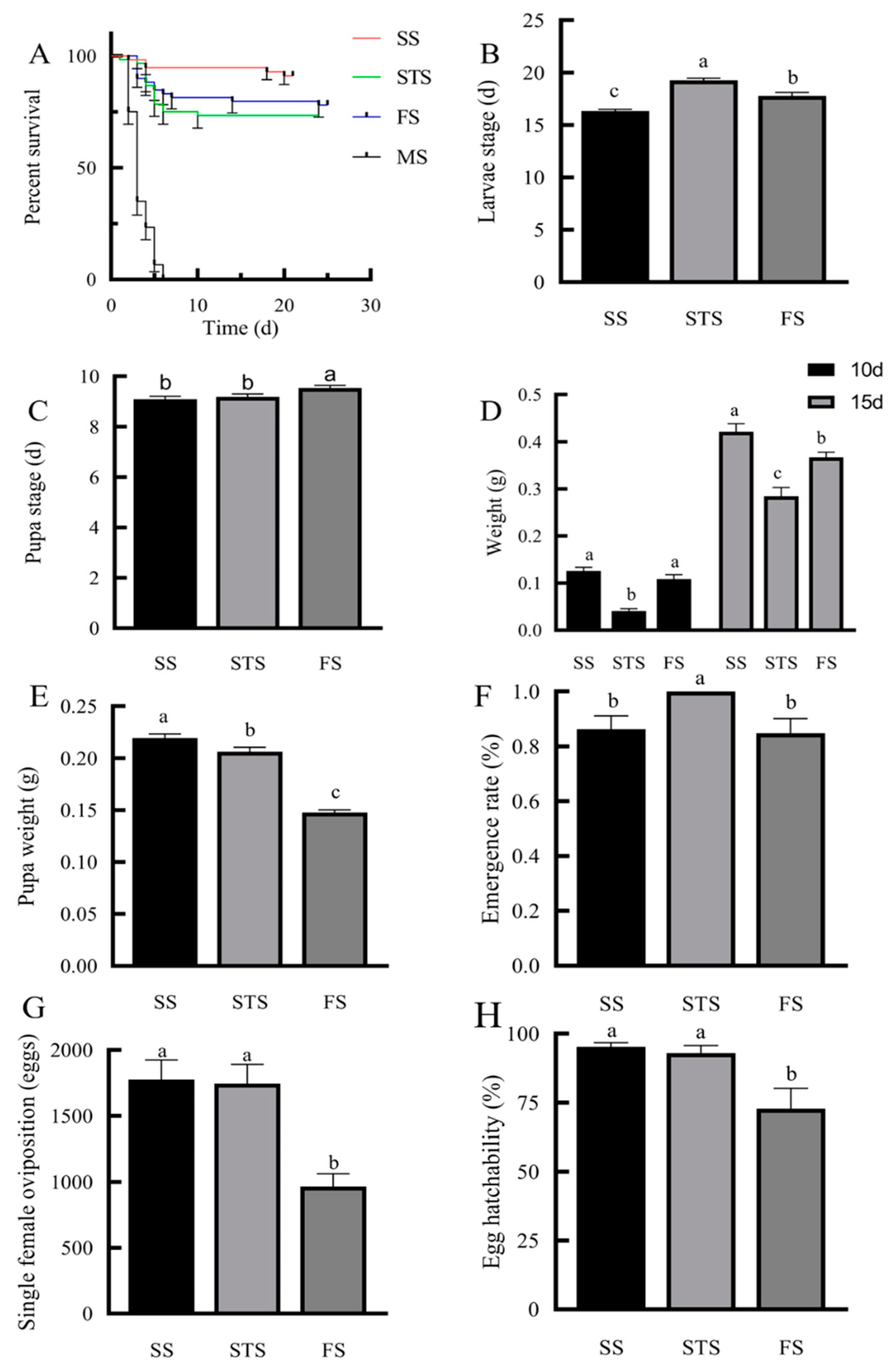

3.3. Effects of Feeding Maize Leaves at Different Growth Stages on the Growth, Development, and Reproduction of S. frugiperda

The survival rates of

S. frugiperda larvae varied significantly across maize growth stages (

Figure 4A). The highest survival rate was observed on SS leaves (91.07%), followed by FS (77.97%), and STS (73.33%). Complete mortality occurred within 5 days on MS leaves, leading to their exclusion from subsequent analyses.

Larvae fed on SS leaves had significantly shorter developmental durations for both larval (16.33 days) and pupal stages (9.09 days) compared to other stages (P < 0.05;

Figure 4B,C). On day 10, there was no significant difference in body weight between larvae fed on SS (0.13 g) and STS (0.11 g) leaves (P > 0.05). However, by day 15, larvae fed on SS leaves exhibited significantly higher body weights and pupal weights compared to those fed on other stages (P < 0.05;

Figure 4D-E) with the highest pupation rate (91%;

Figure 4F).

Reproductive performance showed parallel trends, with females from SS- and STS-reared producing over 1,700 eggs per female and hatching rates exceeding 90%, significantly surpassing FS-reared females (965 eggs with 72% hatching; P < 0.05;

Figure 4G,H).

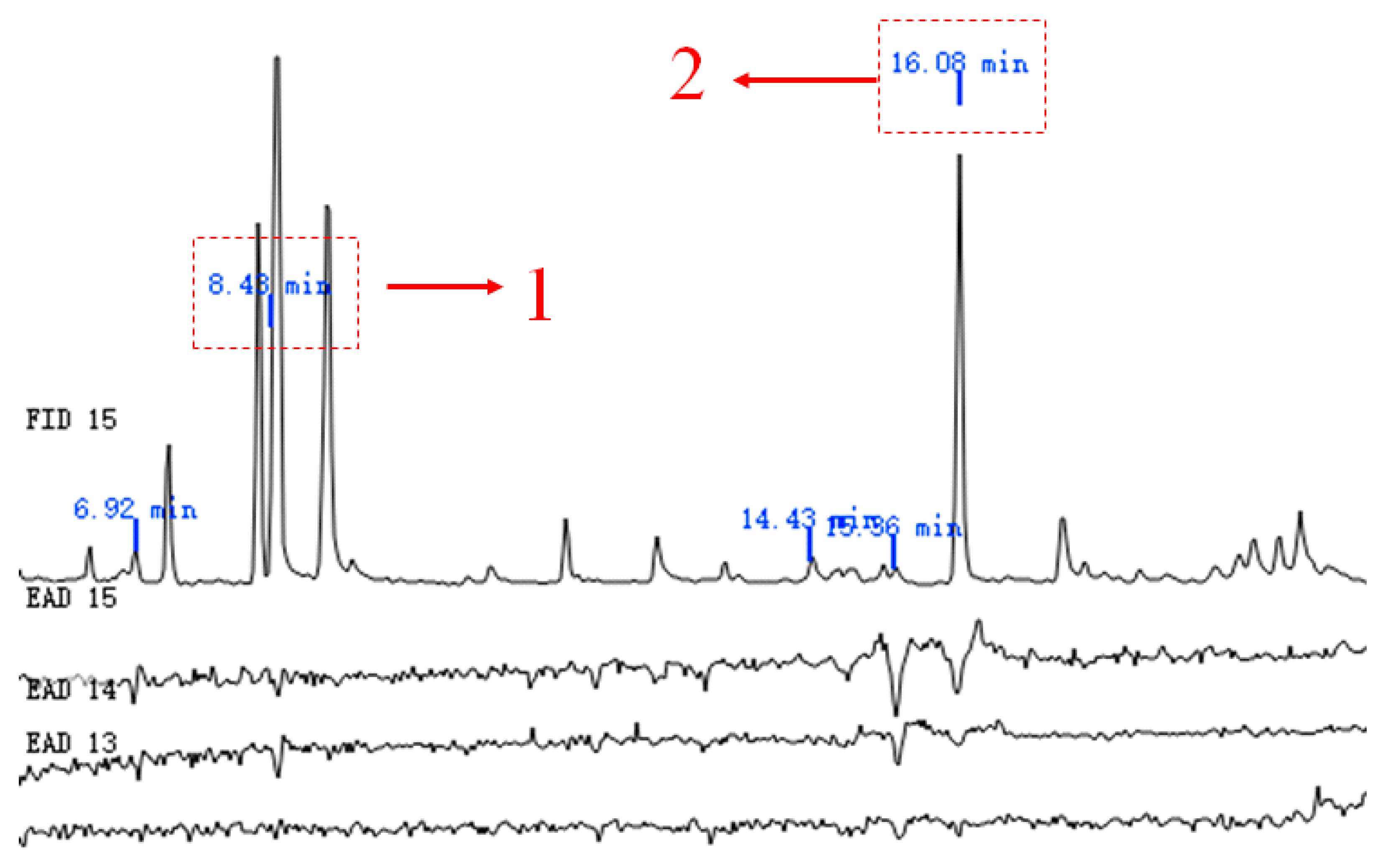

3.4. GC-EAD and GC-MS Analysis of Volatile Compounds from Maize at Key Growth Stages

Given the strong oviposition preference and superior larval performance on SS leaves (

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3), we focused on volatile compounds from SS leaves for GC-EAD and GC-MS.

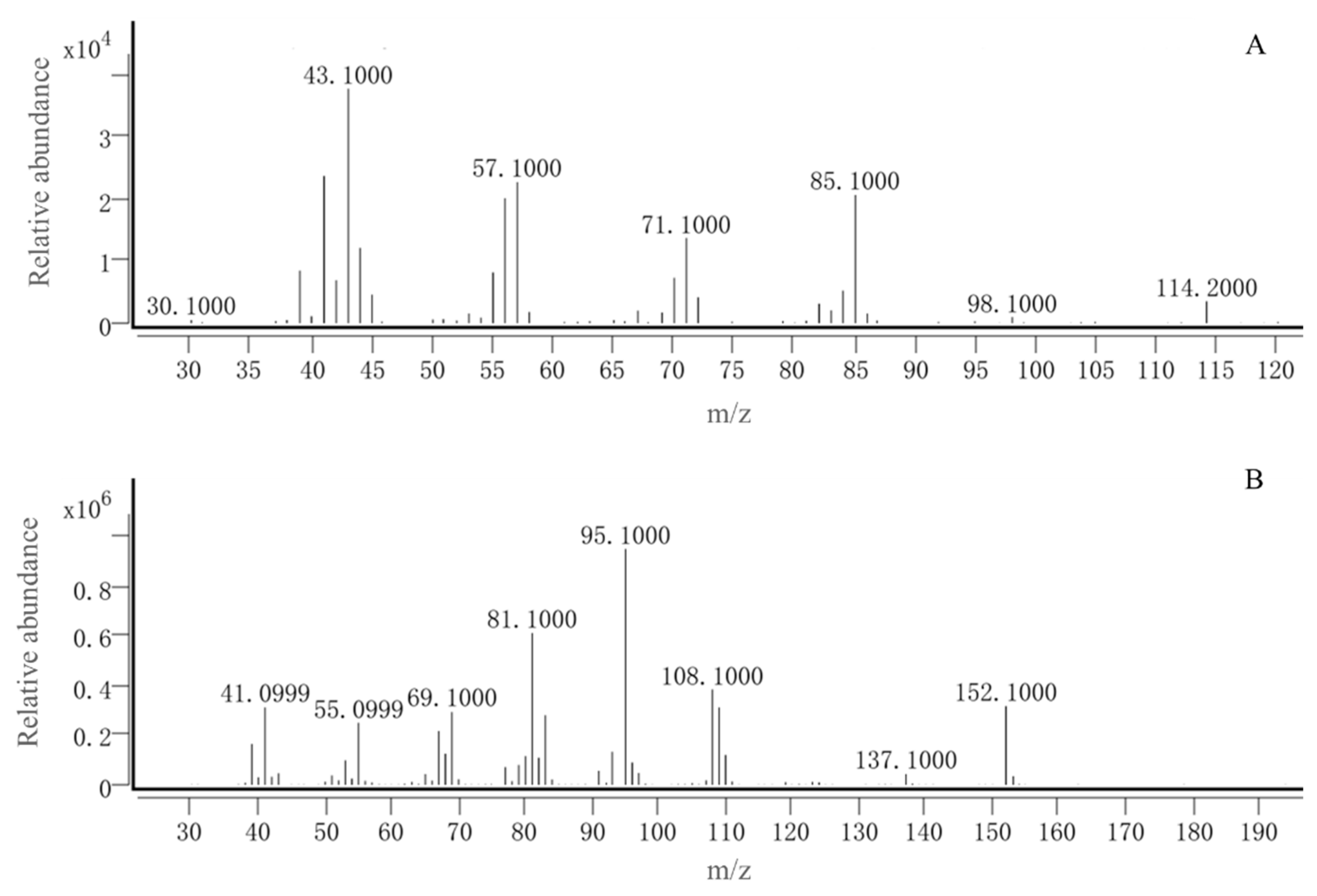

GC-EAD analysis revealed significant antennal responses at retention times of 8.43, 15.36, and 16.08 minutes (

Figure 5). Subsequent GC-MS identification confirmed that peaks at 8.43 and 16.08 minutes corresponded to 1 p-xylene and (+)-camphor, respectively, by comparing with authentic standards. The compound at 15.36 minutes remained uncharacterized due to the lack of a standard sample. Therefore, p-xylene and (+)-camphor were selected for further behavioral studies (

Figure 6).

A quantitative comparison of volatile profiles across different growth stages revealed that the concentration of p-xylene in SS leaves (18.2% relative content) was significantly higher than in other periods. The concentration of (+)-camphor in SS was also the highest (2.48%) although it showed no significant differences compared with those in STS (1.30%), FS (2.08%) and MS (1.78%) (

Table 1).

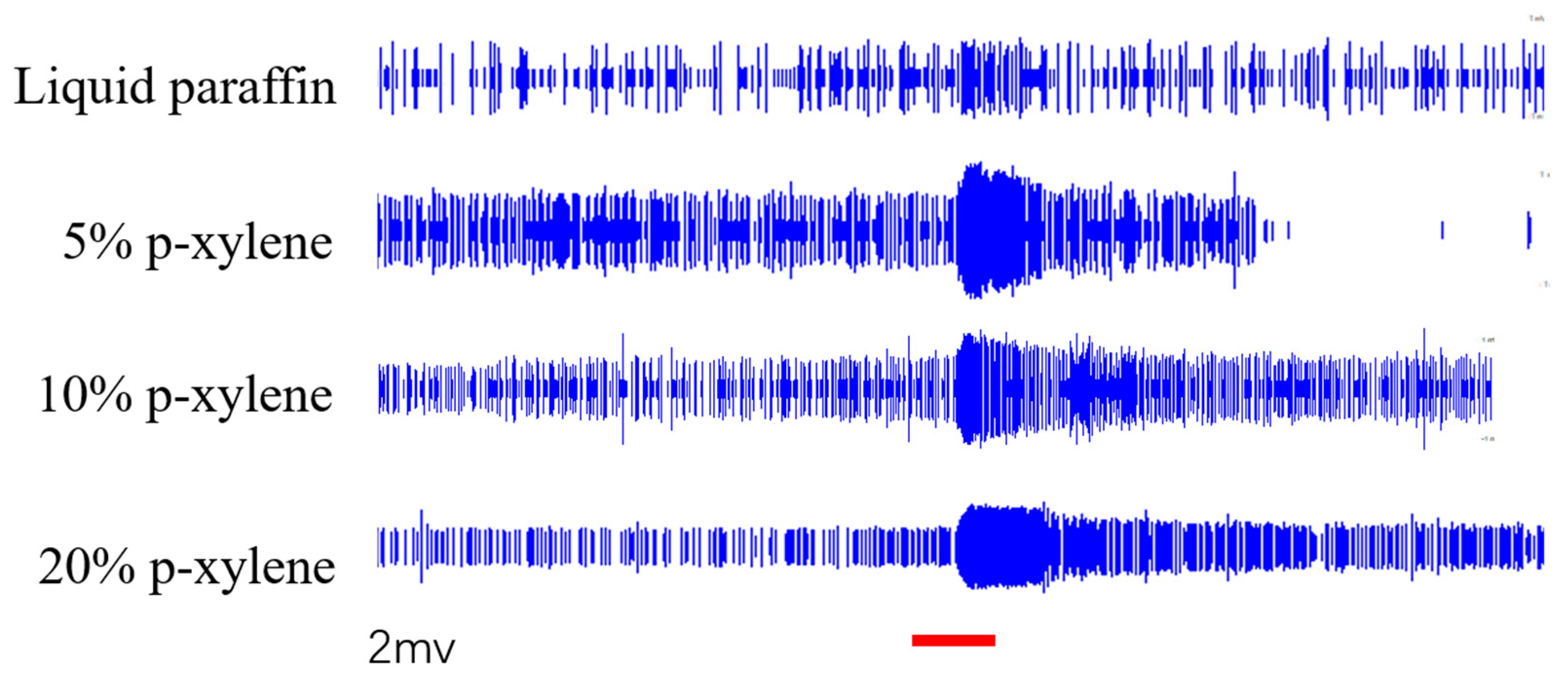

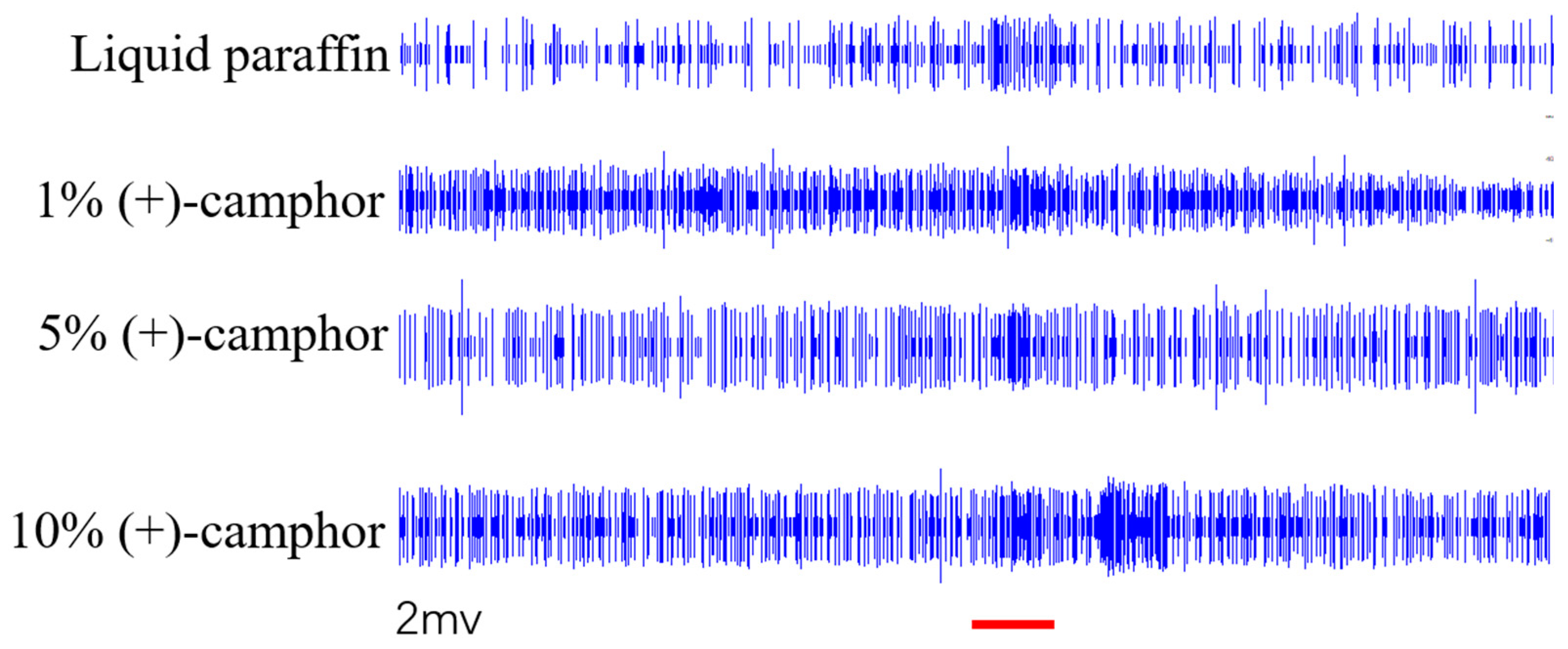

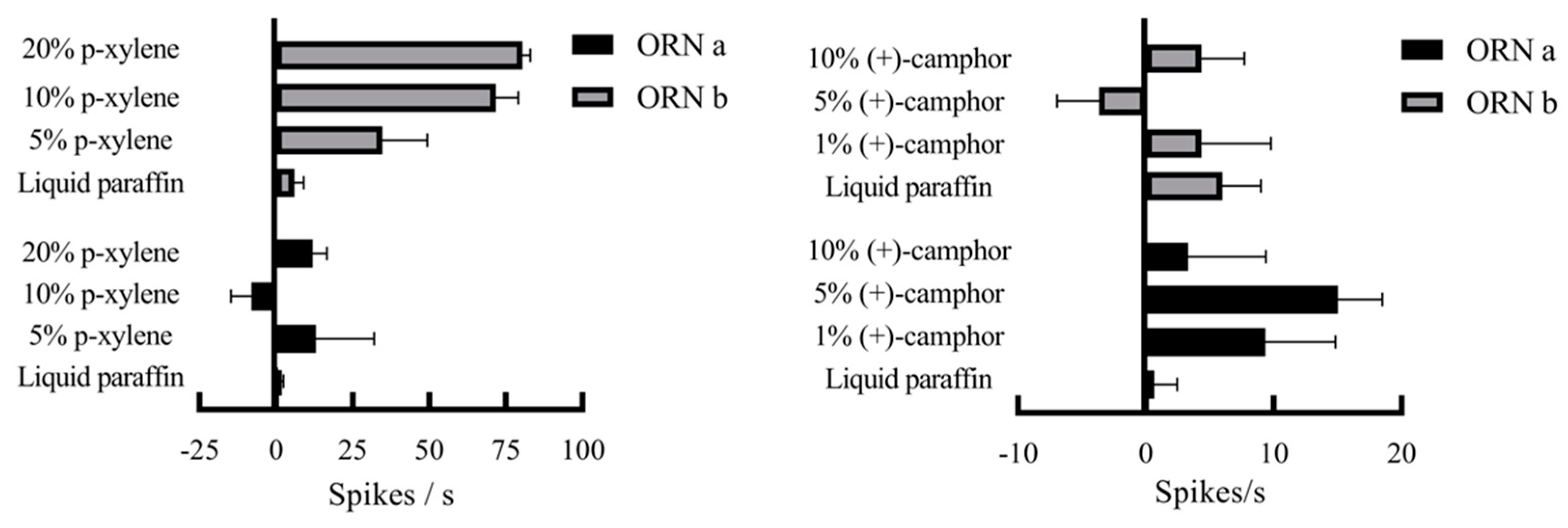

3.5. SSR Validation of GC-EAD Results

SSR was performed to validate the electrophysiological responses to p-xylene and (+) -camphor identified via GC-EAD. Female S. frugiperda adults were tested with p-xylene at 5%, 10%, and 20% dilutions in liquid paraffin and (+)-camphor at 1%, 5%, and 10%. Mid-antennal sensilla contained two distinct neuronal types.

For p-xylene:

Neuron A showed excitation at 5% (13.00 spikes/s) and 20% (12.00 spikes/s) but inhibition at 10% (-8.00 spikes/s) compared to the paraffin control (0.67 spikes/s).

Neuron B showed dose-dependent excitation with the highest response at 20% (80.33 spikes/s vs control: 6.00 spikes/s).

For (+)-camphor:

Neuron A had the strongest response at 5% (15.00 spikes/s) with lesser responses at 1% (9.33 spikes/s) and 10% (3.33 spikes/s).

Neuron B showed a biphasic response: inhibition at 5% (-3.67 spikes/s), and neutral responses at 1% and 10% (4.33 spikes/s). These responses confirm that female

S. frugiperda have specific olfactory neurons to p-xylene and (+)-camphor (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

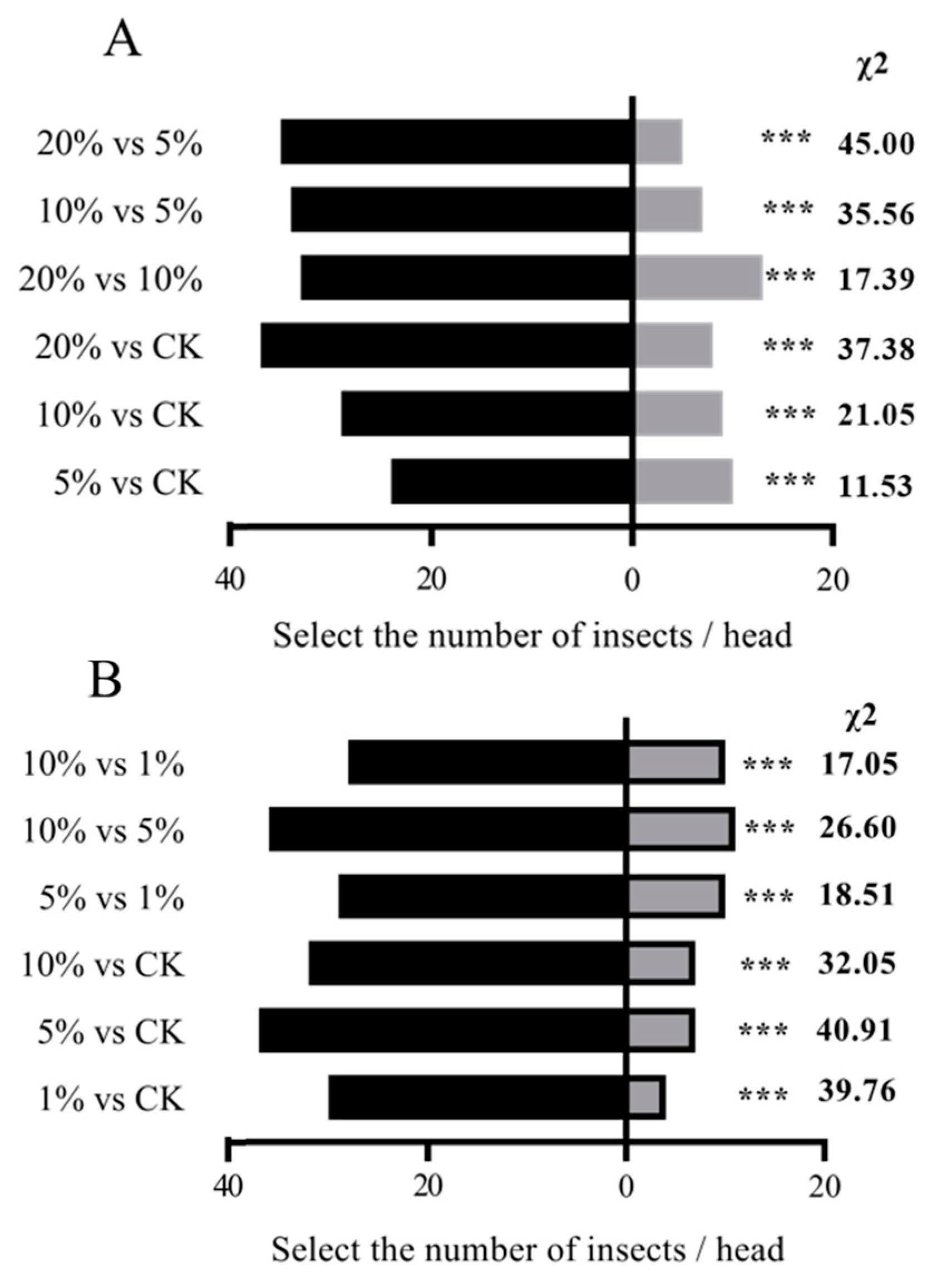

3.6. Olfactory Response of Female Adults of S. frugiperda to Volatile Active Components

Both GC-EAD and SSR confirmed electrophysiological responses of female

S. frugiperda adults. After confirming the electrophysiological activity of p-xylene and (+)-camphor via GC-EAD and SSR, we evaluated their behavioral effects on female

S. frugiperda using a Y-tube olfactometer. For p-xylene, females showed significant dose-dependent attraction at all concentrations, with the strongest attraction at 5% (χ² = 11.53, df = 1, P < 0.01). Attraction increased with higher concentrations (

Figure 9A).

For (+)-camphor, all concentrations (1%, 5%, and 10%) attracted females significantly more than paraffin control (

Figure 9B).

4. Discussion

In this study, we used GC-EAD and SSR to demonstrate that S. frugiperda exhibits significant electrophysiological responses to p-xylene and (+)-camphor. Behavioral assays confirmed that these compounds serve as key odor cues for host recognition in this pest. Notably, the concentration of these two compounds vary across different growth stages of maize, allowing female adults to select optimal oviposition sites that enhance offspring fitness. The co-evolution of herbivorous insects and their host plants has led to an intricate relationship where host plant volatiles play a crucial role in influencing insect behaviors such as oviposition and feeding in the long-term evolution process(Hwang et al. 2008; Dicke and Baldwin 2010). Our findings align with previous research, which has shown that p-xylene and (+) -camphor derivatives are attractive to various insect species. For example, p-xylene has been reported to attract Adelphocoris lineolatus (Xiu et al. 2019), and (+)-camphor has been found to elicit attraction in Pagiophloeus tsushimanus (Chen et al. 2024). Additionally, studies have demonstrated that p-xylene from Luffa aegyptiaca induces differential responses in male and female Bactrocera cucuribitae (Zhou et al. 2023), while m-xylene shows strong attraction to Apolygus lucoru in field experiments (Pan et al. 2015). Furthermore, (-) -camphor has been shown to attract Monochamus saltuarius in indoor behavioral assays (Dong et al. 2024). In our study, both p-xylene and (+) -camphor were most abundant in the seedling stage of maize, suggesting that S. frugiperda can use these volatiles to distinguish between suitable and less suitable host stages for oviposition. The selection of oviposition site by female adults directly determines the habitat and subsequent development success of their offspring. Our study revealed that female S. frugiperda prefers to lay eggs on maize leaves at the seedling stage, where larval survival rates, developmental speed, and weight gain are significantly higher compared to later growth stages. This preference likely stems from the higher nutritional quality and lower levels of defensive secondary metabolites in younger plants (Behmer 2009; Hao et al. 2023; Ying-Bo et al. 2017). Previous studies have reported that as plants mature, they accumulate secondary metabolites that can deter or impair insect herbivores (Mao et al. 2017). For example, Ryu et al (2017) observed gradual increases in flavonols and the aflavins in the leaves of Cordyceps sinensis with plant age, while Ghasemzadeh et al (2016) found the contents of total flavonoids and total phenols peak in 9-month-old maize rhizome extracts. Therefore, we speculated that mature maize with higher levels of insect-resistant substances and lower nutrient content, is less suitable for larval growth and development, explaining the observed differences across growth stages. Given that p-xylene and (+)-camphor are more abundant in seedling-stage maize, female S. frugiperda can use these cues to select this optimal stage for oviposition, thereby enhancing offspring fitness. This finding has significant implications for pest management, as it suggests that control strategies should priortize the seedling stage, particularly during autumn maize production. Focusing on this critical stage could maximize the efficacy of interventions, given the large population base at this stage.

Our study also highlighted gender-specific responses to host volatiles, with female S. frugiperda exhibiting distinct preferences compared to males, a pattern consistent with observations in other insect species. For example, in Heliothis virescens, females show a weaker response to the main sex pheromone compound Z11-16: Ald compared to males (Groot et al. 2005), and in Grapholita molesta, males are significantly attracted to female-released sex pheromones (Z8-12: Ac and E8-12: Ac). These gender-specific olfactory responses suggest that food attractants, which target host recognition cues, might be particularly effective for managing female S. frugiperda, as they are the primary agents in selecting oviposition sites. Currently, while sex attractants have been developed for S. frugiperda control (Saveer et al. 2023; Hu et al. 2024), while there is relative scarcity of food attractants. Our study provides a theoretical foundation for developing such attractants by identifying key host recognition cues, potentially offering a more sustainable and targeted approach to pest management.

In summary, this study investigated the host preference and recognition mechanism of S. frugiperda, identifying p-xylene and (+) -camphor as key attractants for female adults.. While our findings are promising, field validation is necessary to confirm their efficacy in practical pest control scenarios. Future research should focus on determining the optimal combination ratios of these two compounds to maximize their attractiveness, as previous studies have shown that the combination of attractive compounds in a certain proportion can significantly enhance their effect (Bian et al. 2018; Tasin et al. 2018). Additionally, exploring the integration of these food attractants with sex attractants or visual cues could lead to more effective strategies for monitoring and controlling S. frugiperda populations (Ren et al. 2022; Liu et al. 2024). Such integrated approaches could provide a feasible method for field monitoring and control, addressing the current gap in food attractant development and enhancing the sustainability of pest management practices.

5. Conclusion

This study proved that p-xylene and (+)-camphor in the volatile of maize served as critical cues for female Spodoptera frugiperda to determine growth stages of maize and locate appropriate habitat for offspring.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32001966).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alicia PA, Byrappa A, César G. 2022. A closer look at sex pheromone autodetection in the Oriental fruit moth. SCI REP-UK 12(1): 7019.

- Behmer, S.T. Insect herbivore nutrient regulation. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2009, 54, 165–187. [CrossRef]

- Betancurt CJ, Sajjan G, J. BM, Lucas B, Pritha K, G. KK, et al. 2023. Sugars and cuticular waxes impact sugarcane aphid (Melanaphis sacchari) colonization on different developmental stages of sorghum. PLANT SCI 330: 111646.

- Bian, L.; Cai, X.-M.; Luo, Z.-X.; Li, Z.-Q.; Xin, Z.-J.; Chen, Z.-M. Design of an attractant for Empoasca onukii (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) based on the volatile components of fresh tea leaves. J. Econ. Èntomol. 2018, 111, 629–636. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, T.; Li, S.; Xue, M.; Deng, Y.; Fan, B.; Yang, C.; Hao, D. The Key Phytochemical Cue Camphor Is a Promising Lure for Traps Monitoring the New Monophagous Camphor Tree Borer Pagiophloeus tsushimanus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 2024, 50, 1023–1035. [CrossRef]

- Cock, M.J.W.; Beseh, P.K.; Buddie, A.G.; Cafá, G.; Crozier, J. Molecular methods to detect Spodoptera frugiperda in Ghana, and implications for monitoring the spread of invasive species in developing countries. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Dicke, M.; Baldwin, I.T. The evolutionary context for herbivore-induced plant volatiles: beyond the ‘cry for help’. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 167–175. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhou, S.; Mao, Z.; Fan, J. Identification of Attractants from Three Host Plants and How to Improve Attractiveness of Plant Volatiles for Monochamus saltuarius. Plants 2024, 13, 1732. [CrossRef]

- Dumas, P.; Legeai, F.; Lemaitre, C.; Scaon, E.; Orsucci, M.; Labadie, K.; Gimenez, S.; Clamens, A.-L.; Henri, H.; Vavre, F.; et al. Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) host-plant variants: two host strains or two distinct species? Genetica 2015, 143, 305–316. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Jaafar, H.Z.E.; Ashkani, S.; Rahmat, A.; Juraimi, A.S.; Puteh, A.; Mohamed, M.T.M. Variation in secondary metabolite production as well as antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Zingiber zerumbet (L.) at different stages of growth. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 104–104. [CrossRef]

- Groot A, Cé, Gemeno S, Brownie C, Gould F, Schal C. 2005. Male and Female Antennal Responses in Heliothis virescens and H. subflexa to Conspecific and Heterospecific Sex Pheromone Compounds. ENVIRON ENTOMOL 34(2): 256-263.

- He, L.-M.; Wu, Q.-L.; Gao, X.-W.; Wu, K.-M. Population life tables for the invasive fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda fed on major oil crops planted in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 745–754. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Q.; Liang, K.; Yu, G.; He, M.; Chen, D.; Su, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Comparation of pheromone-binding proteins 1 and 2 of Spodoptera frugiperda in perceiving the three sex pheromone components Z9-14:Ac, Z7-12: Ac and Z11-16: Ac. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 206, 106183. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-Y.; Liu, C.-H.; Shen, T.-C. Effects of plant nutrient availability and host plant species on the performance of two Pieris butterflies (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2008, 36, 505–513. [CrossRef]

- Jiang YY, Liu J, Xie MC, Li YH, Yang JJ, Zhang ML, et al. 2019. Observation on law of diffusion damage of Spodoptera frugiperda in China in 2019. Plant Protection 45(6): 10-19.

- Johnnie VDB, Hannalene DP. 2022. Chemical control and insecticide resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J ECON ENTOMOL 115(6): 1761-1771.

- Juárez, M.L.; Murúa, M.G.; García, M.G.; Ontivero, M.; Vera, M.T.; Vilardi, J.C.; Groot, A.T.; Castagnaro, A.P.; Gastaminza, G.; Willink, E. Host Association of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Corn and Rice Strains in Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. J. Econ. Èntomol. 2012, 105, 573–582. [CrossRef]

- Li, CY, Zhang, YP, Huang, SH, Liu, WL, Su, XN, Pan, ZP. (2019). Research on artificial rearing techniques of Spodoptera frugiperda in laboratory. Journal of Environmental Entomology, 41(5), 986-991.

- Lin, H.; Yao, Y.; Sun, P.; Feng, L.; Wang, S.; Ren, Y.; Yu, X.; Xi, Z.; Liu, J. Haplotype-resolved genomes of two buckwheat crops provide insights into their contrasted rutin concentrations and reproductive systems. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tallat, M.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Qiao, H.; Zhao, X.; Feng, H. The Utility of Visual and Olfactory Maize Leaf Cues in Host Finding by Adult Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Plants 2024, 13, 3300. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.-B.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Chen, D.-Y.; Chen, F.-Y.; Fang, X.; Hong, G.-J.; Wang, L.-J.; Wang, J.-W.; Chen, X.-Y. Jasmonate response decay and defense metabolite accumulation contributes to age-regulated dynamics of plant insect resistance. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 13925. [CrossRef]

- Maruthadurai R, Ramesh R. 2020. Occurrence, damage pattern and biology of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE smith)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on fodder crops and green amaranth in Goa, India. PHYTOPARASITICA 48(1): 15-23.

- Moustafa AMM, Said AEN, Alfuhaid AN, Elinin FMAA, Mohamed RMB, Aioub AAA. 2024. Monitoring and Detection of Insecticide Resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae): Evidence for Field-Evolved Resistance in Egypt. INSECTS 15(9): 705.

- Nagoshi, R.N.; Goergen, G.; Koffi, D.; Agboka, K.; Adjevi, A.K.M.; Du Plessis, H.; Berg, J.V.D.; Tepa-Yotto, G.T.; Winsou, J.K.; Meagher, R.L.; et al. Genetic studies of fall armyworm indicate a new introduction into Africa and identify limits to its migratory behavior. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Lu, Y.; Xiu, C.; Geng, H.; Cai, X.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Iii, L.W.; Wyckhuys, K.A.G.; Wu, K. Volatile fragrances associated with flowers mediate host plant alternation of a polyphagous mirid bug. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14805. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, P.; Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Jin, D.; Guo, J. Research of synergistic substances on tobacco beetle [Lasioderma serricorne (Fabricius)(Coleoptera: Anobiidae)] adults attractants. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 921113. [CrossRef]

- Ryu WH, Yuk JH, An HJ, Kim D, Song H, Oh S. 2017. Comparison of secondary metabolite changes in Camellia sinensis leaves depending on the growth stage. FOOD CONTROL 73: 916-921.

- Sagar, G.; Aastha, B.; Laxman, K. An introduction of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) with management strategies: a review paper. Nippon. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- Saveer, A.M.; Hatano, E.; Wada-Katsumata, A.; Meagher, R.L.; Schal, C. Nonanal, a new fall armyworm sex pheromone component, significantly increases the efficacy of pheromone lures. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 2831–2839. [CrossRef]

- Sosa, A.; Diaz, M.; Salvatore, A.; Bardon, A.; Borkosky, S.; Vera, N. Insecticidal effects of Vernonanthura nebularum against two economically important pest insects. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 881–889. [CrossRef]

- Sparks AN. 1979. Fall Armyworm Symposium: A review of the biology of the fall armyworm. FLA ENTOMOL: 82-87.

- Sun, X.-X.; Hu, C.-X.; Jia, H.-R.; Wu, Q.-L.; Shen, X.-J.; Zhao, S.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Wu, K.-M. Case study on the first immigration of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda invading into China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 664–672. [CrossRef]

- Tait, G.; Mermer, S.; Stockton, D.; Lee, J.; Avosani, S.; Abrieux, A.; Anfora, G.; Beers, E.; Biondi, A.; Burrack, H.; et al. Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae): A Decade of Research Towards a Sustainable Integrated Pest Management Program. J. Econ. Èntomol. 2021, 114, 1950–1974. [CrossRef]

- Tasin, M.; Herrera, S.L.; Knight, A.L.; Barros-Parada, W.; Contreras, E.F.; Pertot, I. Volatiles of grape inoculated with microorganisms: Modulation of grapevine moth oviposition and field attraction. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 76, 751–761. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-L.; He, L.-M.; Shen, X.-J.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, G.; Wu, K.-M. Estimation of the Potential Infestation Area of Newly-invaded Fall Armyworm Spodoptera Frugiperda in the Yangtze River Valley of China. Insects 2019, 10, 298. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.-T. Research on the invasive pest of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 633–636. [CrossRef]

- Xiu, C.-L.; Pan, H.-S.; Liu, B.; Luo, Z.-X.; Williams, L.; Yang, Y.-Z.; Lu, Y.-H. Perception of and behavioral responses to host plant volatiles for three Adelphocoris species. J. Chem. Ecol. 2019, 45, 779–788. [CrossRef]

- Yang XL, Liu YC, Luo MZ, Li Y, Wang WH, Wan F, et al. 2019. Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) was first discovered in Jiangcheng County of Yunnan Province in southwestern China. Yunnan Agric 1: 72.

- Yu, S.J.; Nguyen, S.N.; Abo-Elghar, G.E. Biochemical characteristics of insecticide resistance in the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2003, 77, 1–11, doi:10.1016/s0048-3575(03)00079-8.

- Zhou Y, Jin FY, Gao X, Chen HS, Ma WH, Zhou ZS, et al. 2023. Electroantennographic and Behavioral Responses of Bactrocera cucurbitae (Coquillett) to Volatile Compounds of Luffa acutangular L.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).