Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plants and Insects

2.2. Larval Exposure to Maize HIPVs and Its Effects on Xenobiotic Tolerance

2.3. Volatile Compounds Toxicity and Exposure to cis-3-hexene-1-ol

2.4. Determination of Pupation Rate, Emergence Rate and Egg Hatchability

2.5. Enzyme Activity of P450, GST and CarE

2.6. Gene Expression Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

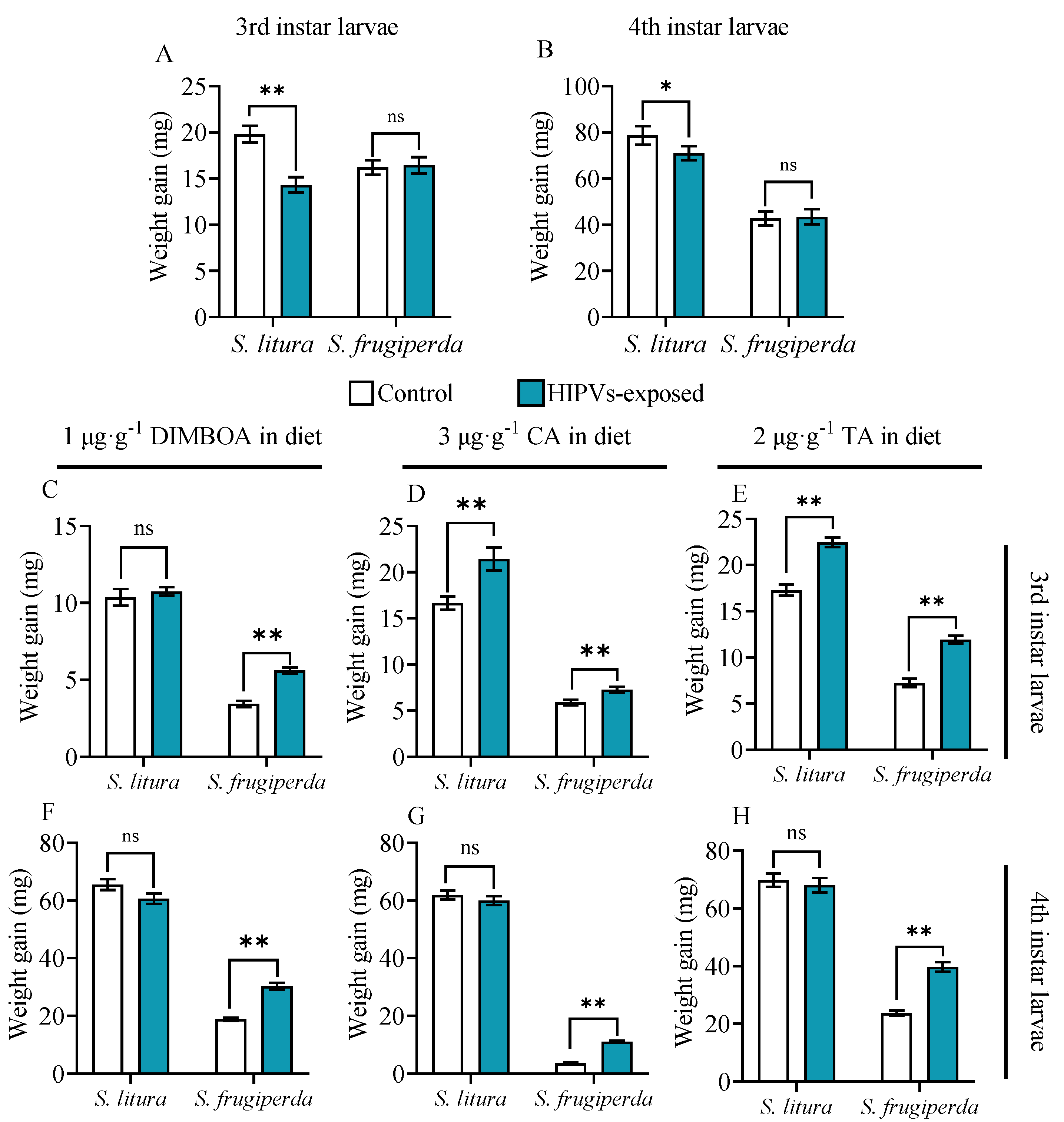

3.1. Maize HIPVs Promote Larval Tolerance to Plant Defensive Chemicals

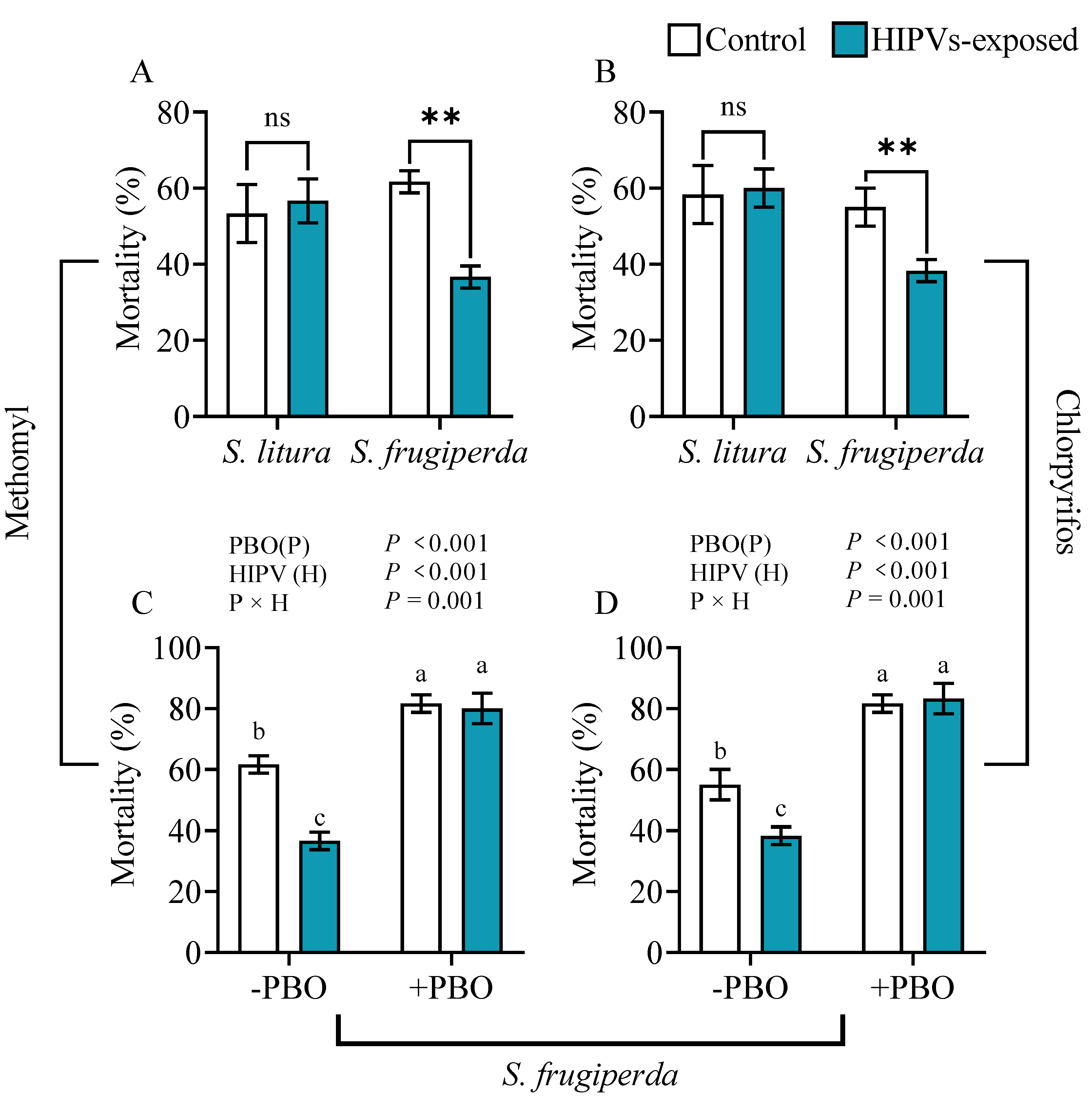

3.2. Maize HIPVs Promote Larval Tolerance to Insecticides Methomyl and Chlorpyrifos

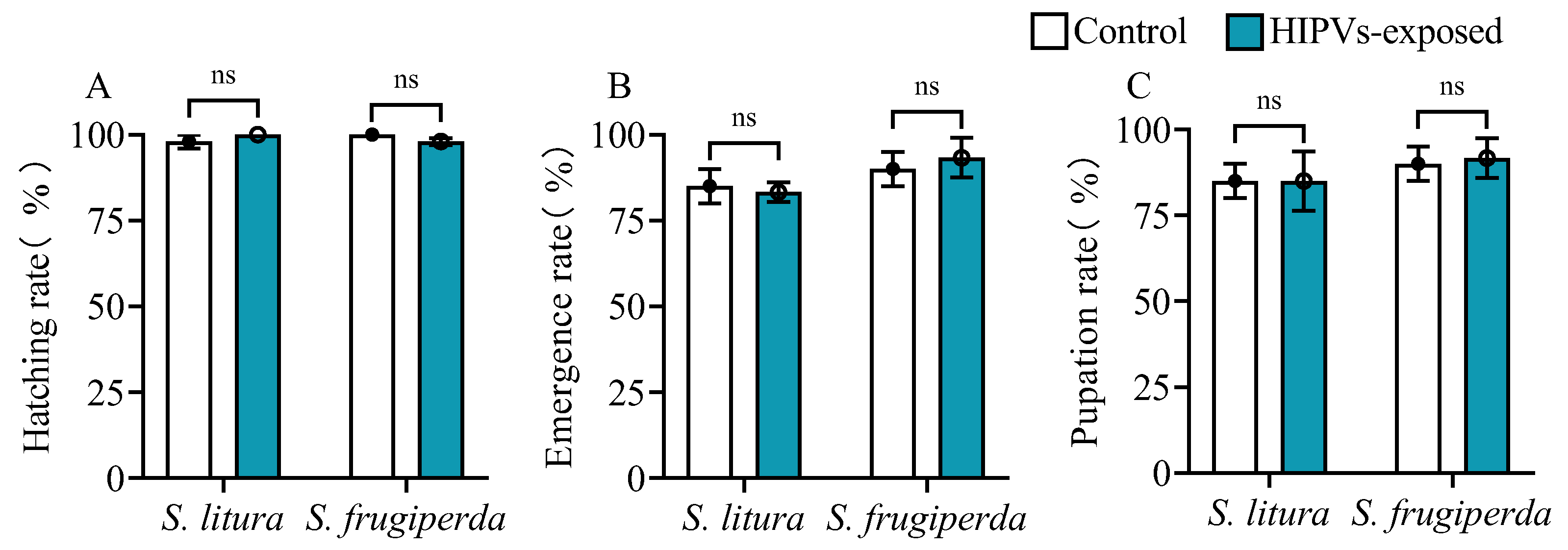

3.3. Maize HIPVs Exposure Does Not Affect Insect Development

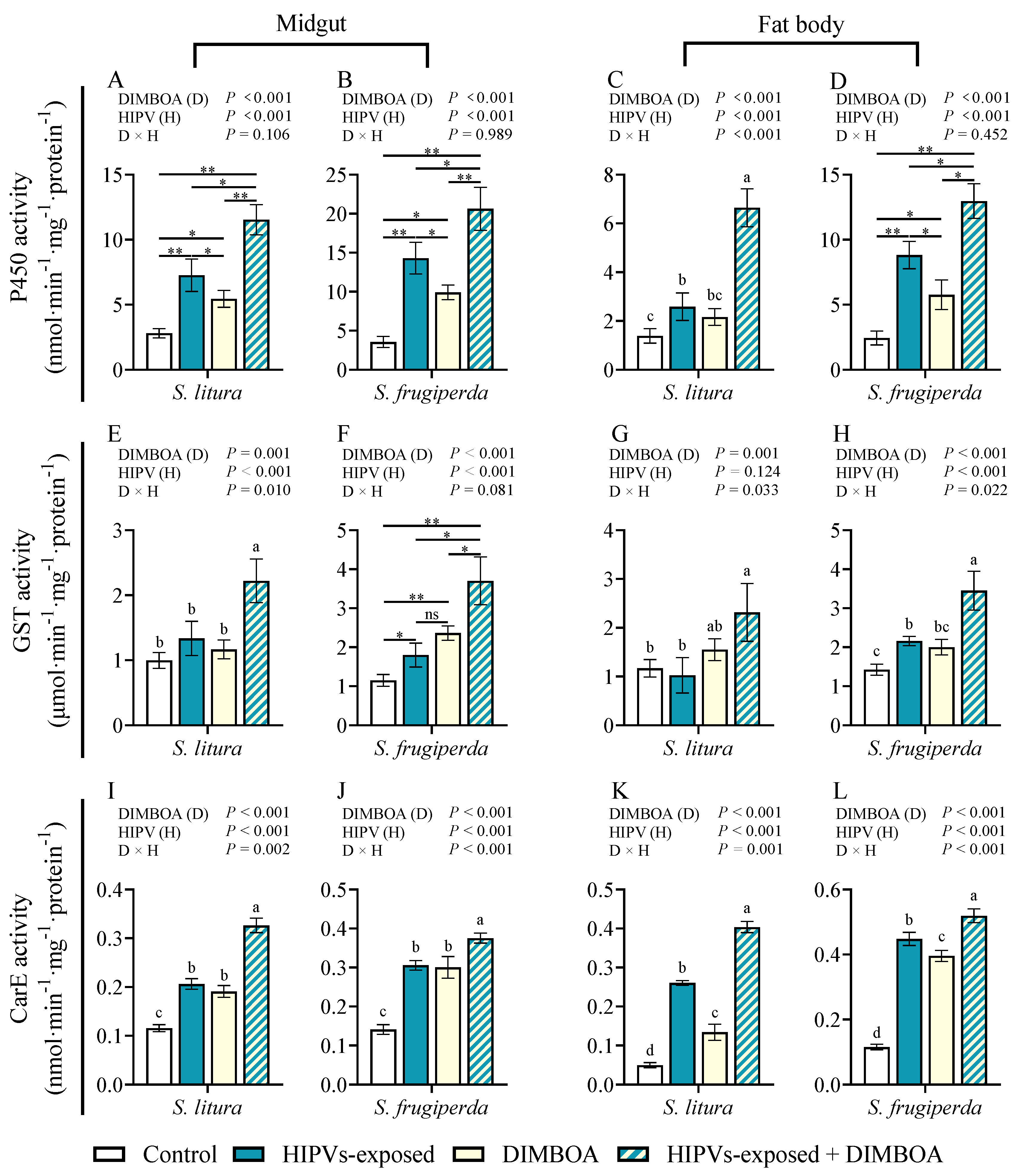

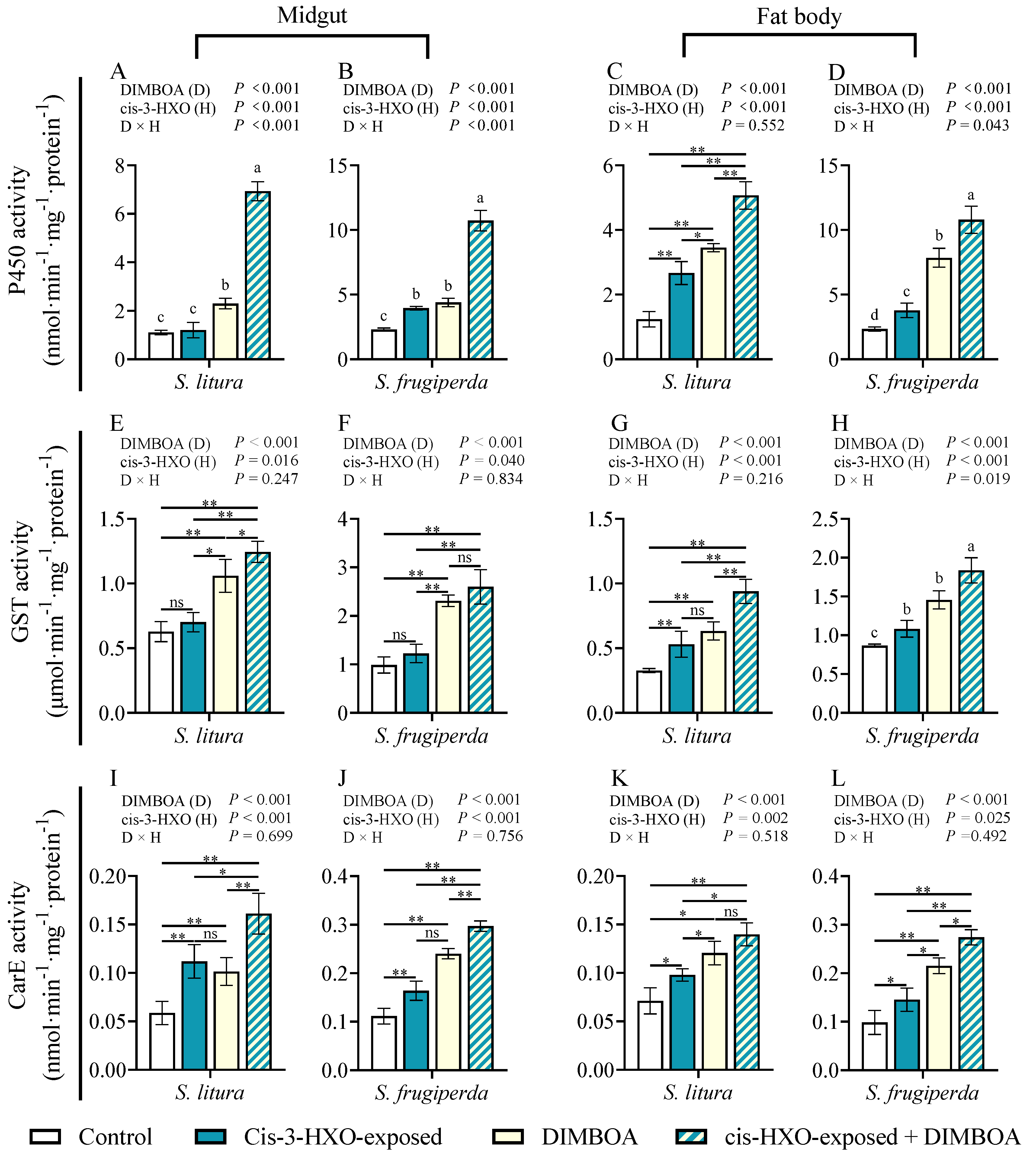

3.4. Maize HIPVs and DIMBOA Show Synergistic Effect on Induction of Detoxification Enzymes

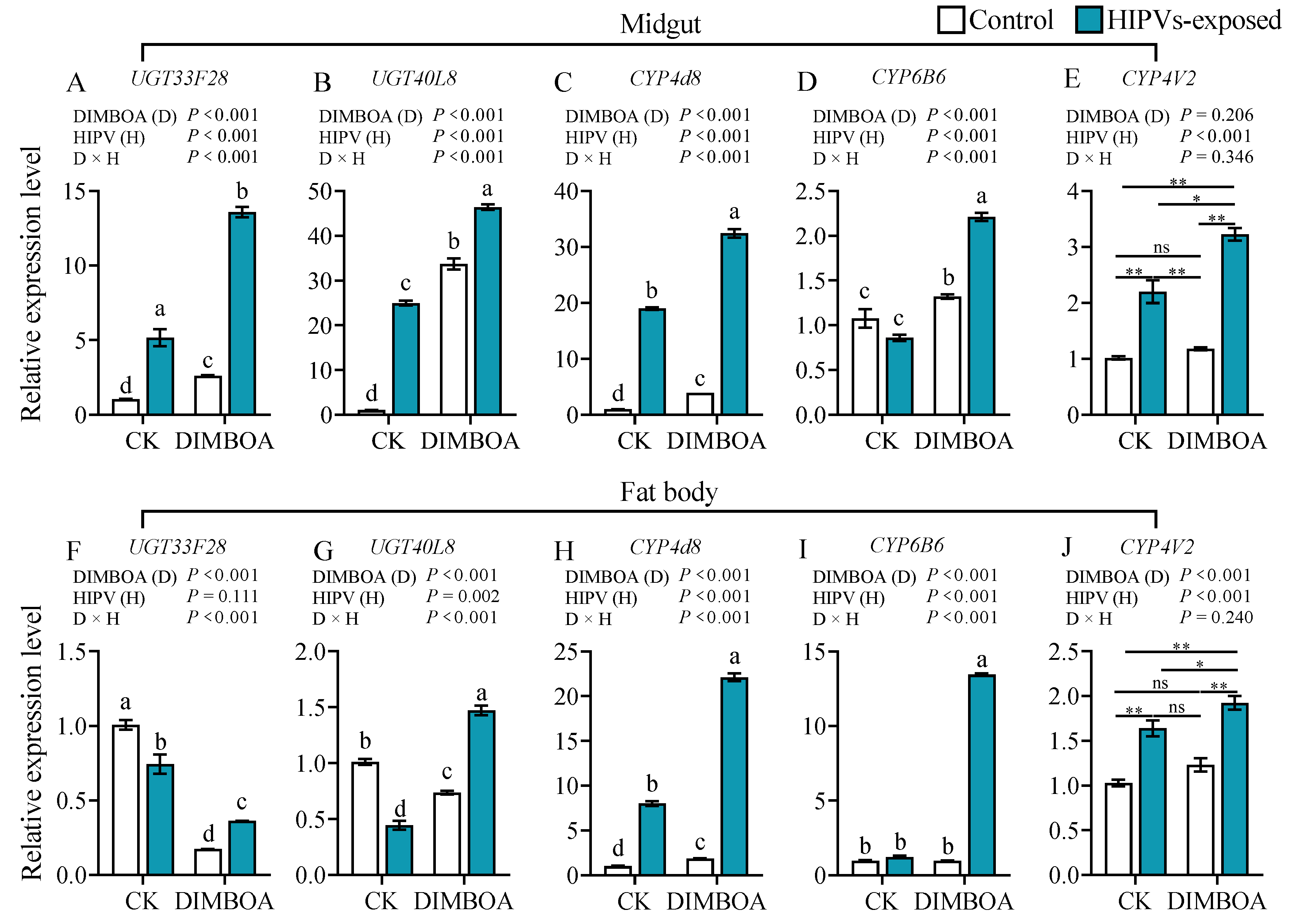

3.5. Maize HIPVs and DIMBOA Show Synergistic Effect on Induction of Detoxification Associated Genes

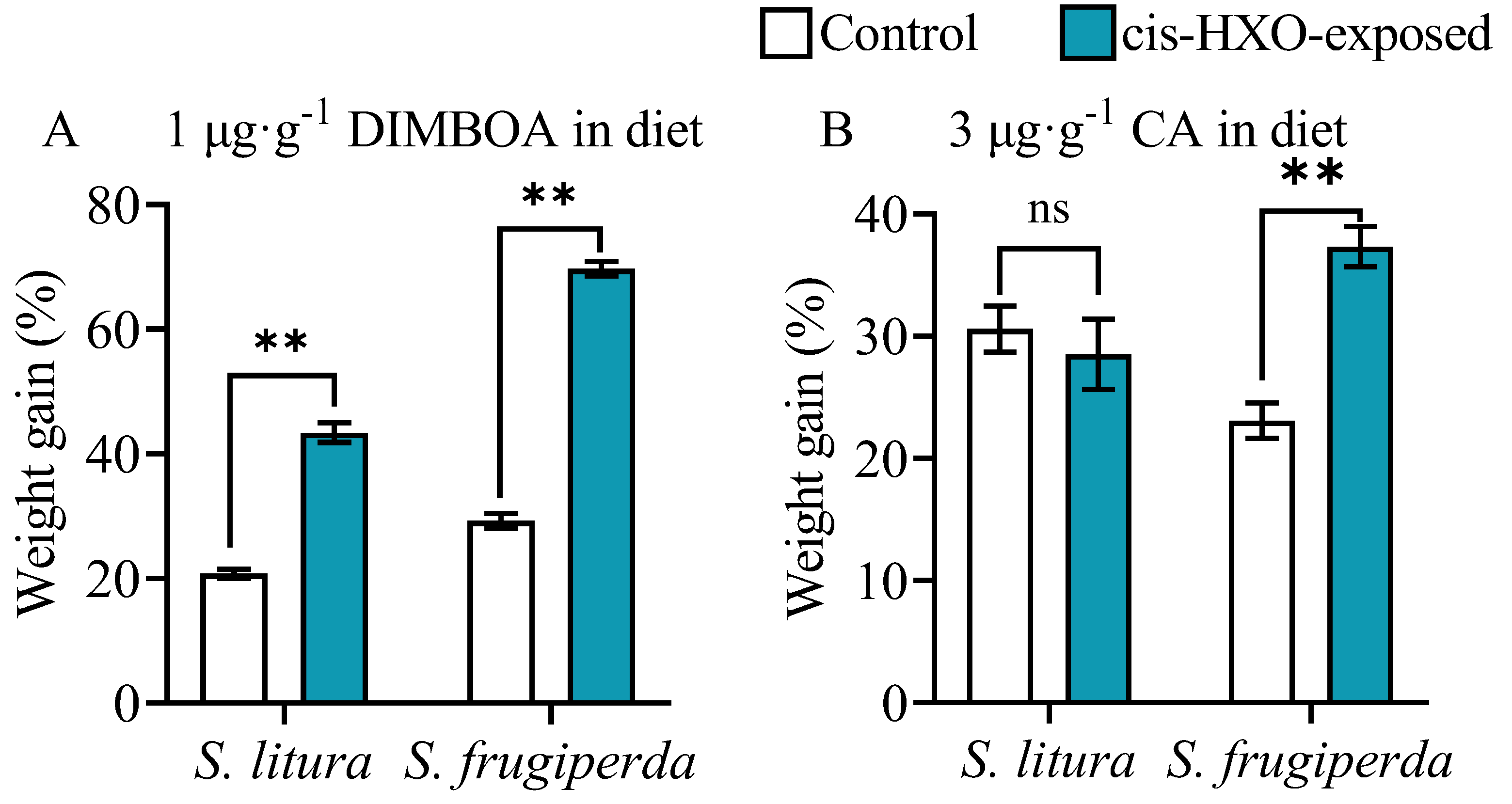

3.6. Larval Exposure to cis-3-hexen-1-ol Enhances Tolerance to Plant Defensive Chemicals

3.7. Cis-3-Hexen-1-ol and DIMBOA Show Synergistic Effect on Induction of Detoxification Enzymes

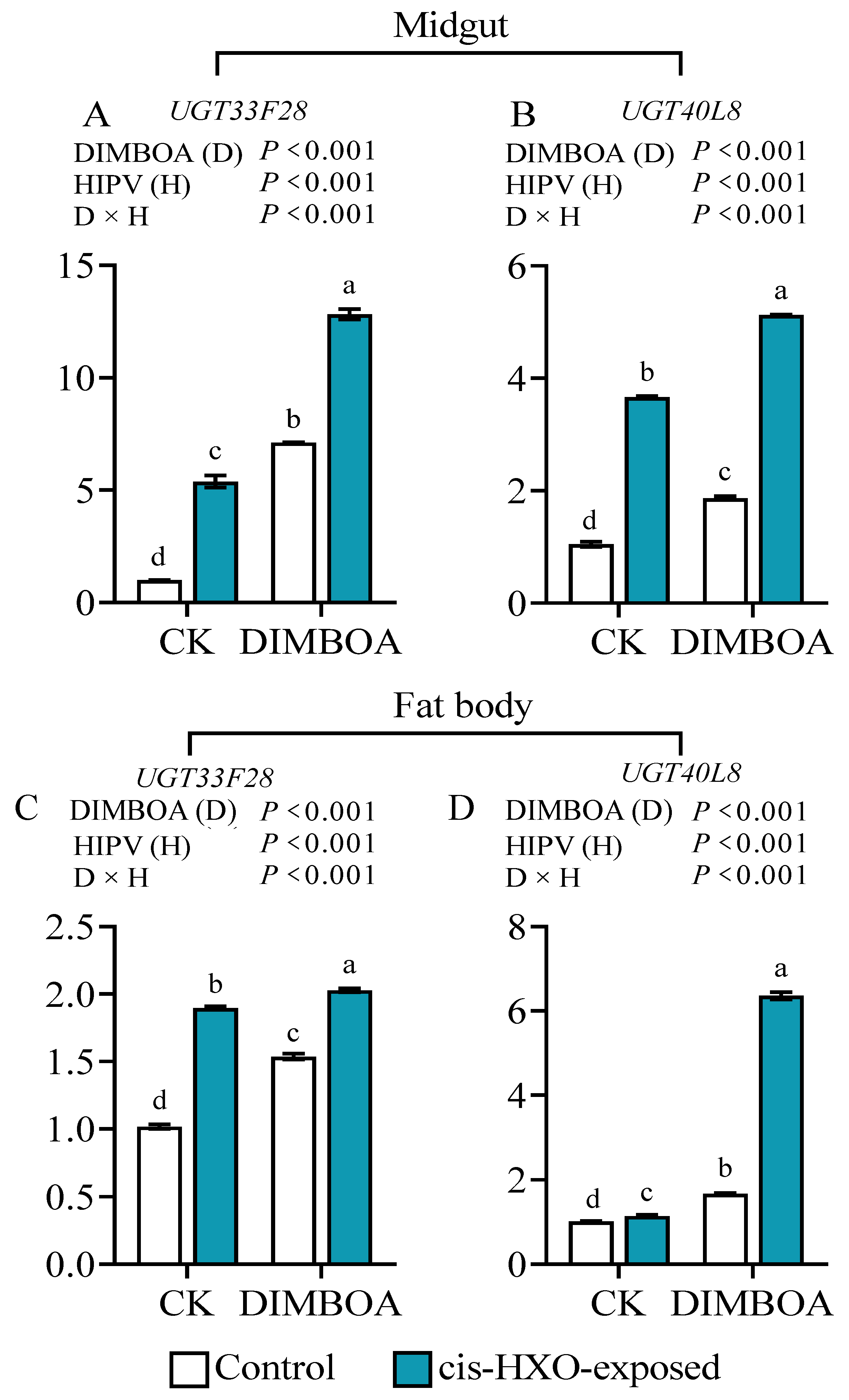

3.8. Cis-3-Hexen-1-ol and DIMBOA Upregulate UGT33F28 and UGT40L8

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erb, M.; Reymond, P. Molecular Interactions Between Plants and Insect Herbivores. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 527–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohgushi, T. Eco-evolutionary dynamics of plant-herbivore communities: Incorporating plant phenotypic plasticity. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2016, 14, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuman, M.C.; Baldwin, I.T. The layers of plant responses to insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2016, 61, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, A. The information landscape of plant constitutive and induced secondary metabolite production. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 8, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Q.; Annett, R.; Georg, J. Beyond defense: Multiple functions of benzoxazinoids in maize metabolism. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Halitschke, R.; Li, D.P.; Paetz, C.; Su, H.C.; Heiling, S.; Xu, S.Q.; Baldwin, I.T. Controlled hydroxylations of diterpenoids allow for plant chemical defense without autotoxicity. Science. 2021, 371, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lybrand, D.B.; Xu, H.Y.; Last, R.L.; Pichersky, E. How plants synthesize pyrethrins: Safe and biodegradable insecticides. Trends in Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.H.F.; Heiko, V. Molecular mechanisms of insect adaptation to plant secondary compounds. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 8, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, K.; Cheng, Y.B.; Li, Y.M.; Li, W.R.; Zeng, R.S.; Song, Y.Y. Phytochemical flavone confers broad-spectrum tolerance to insecticides in Spodoptera litura by activating ROS/CncC-mediated xenobiotic detoxification pathways. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7429–7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axel, M.; Wilhelm, B. Plant defense against herbivores: chemical aspects. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 431–450. [Google Scholar]

- Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M. Tritrophic interactions mediated by herbivore-induced plant volatiles: mechanisms, ecological relevance, and application potential. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veyrat, N.; Robert, C.A.M.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M. Herbivore intoxication as a potential primary function of an inducible volatile plant signal. J. Ecol. 2016, 104, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Hedo, M.; Alonso-Valiente, M.; Vacas, S.; Gallego, C.; Pons, C.; Arbona, V.; Rambla, J.L.; Navarro-Llopis, V.; Granell, A.; Urbaneja, A. Plant exposure to herbivore-induced plant volatiles: a sustainable approach through eliciting plant defenses. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.Y.; Qian, J.J.; Hou, X.L.; Zeng, L.T.; Liu, X.; Mei, G.G.; Liao,Y. Y. Diurnal emission of herbivore-induced (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate and allo-ocimene activates sweet potato defense responses to sweet potato weevils. J. Integr. Agr. 2023, 22, 1782–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.Q.; Yang, X.M.; Chen, S.M.; Chen, F.D.; Chen, X.L.; Chen, F.; Jiang, Y.F. Infestation with chewing (Spodoptera frugiperda) and piercing-sucking (Tetranychus urticae) arthropod lead to differential emission and biosynthesis of HIPVs underscoring MeSA and terpenoids in chrysanthemum foliage. Sci. Hortic-Amsterdam. 2024, 326, 112767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, F.R.; Lan, T.M.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, W.; Dong, Y.; Fang, D.M.; Liu, H.; Li, H.M.; Wang, H.L.; Hao, R.S. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis unveils population evolution and development of pesticide resistance in fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. Protein Cell. 2022, 13, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.M.; Ye, X.; Xu, H.; Mei, Y.; Li, F. The genetic adaptations of fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda facilitated its rapid global dispersal and invasion. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 1050–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israni, B.; Luck, K.; Römhild, S.C.W.; Raguschke, B.; Wielsch, N.; Hupfer, Y.; Reichelt, M.; Svatos, A.; Gershenzon, J.; Vassao, D.G. Alternative transcript splicing regulates UDP-glucosyltransferase-catalyzed detoxification of DIMBOA in the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10343. [Google Scholar]

- Erb, M. Volatiles as inducers and suppressors of plant defense and immunity — origins, specificity, perception and signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 44, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, K.; Wu, Z.; Xu, J.M.; Erb, M. Plant volatiles as regulators of plant defense and herbivore immunity: molecular mechanisms and unanswered questions. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021, 44, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, H.; Schuurink, R.C.; Bleeker, P.M.; Schiestl, F. The role of volatiles in plant communication. Plant, J. 2019, 100, 892–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Veyrat, N.; Xu, H.; Hu, L.F.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M. An herbivore-induced plant volatile reduces parasitoid attraction by changing the smell of caterpillars. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasmi, L.; Martinez-Solis, M.; Frattini, A.; Ye, M.; Carmen Collado, M.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M.; Herrero, S. Can herbivore-induced volatiles protect plants by increasing the herbivores' susceptibility to natural pathogens? Appl. Environ. Microb. 2019, 85, e01468–01418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, E.; Venkatesan, R. Plant volatiles modulate immune responses of Spodoptera litura. J. Chem. Ecol. 2019, 45, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.X.; Wang, R.M.; Du, Y.F.; Gao, B.Y.; Gui, F.R.; Lu, K. Olfactory perception of herbicide butachlor by GOBP2 elicits ecdysone biosynthesis and detoxification enzyme responsible for chlorpyrifos tolerance in Spodoptera litura. Env. Pollution. 2021, 285, 117409.1–117409.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.F.; Ding, C.H.; Chen, S.; Wu, X.Y.; Zhang, L.Q.; Song, Y.Y.; Li, W.; Zeng, R.S. Exposure of Helicoverpa armigera larvae to plant volatile organic compounds induces cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and enhances larval tolerance to the insecticide methomyl. Insects. 2021, 12, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhinav, K.M.; Rakhi, C.P.; Christopher, J. Frost Acute toxicity of the plant volatile indole depends on herbivore specialization. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, B.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, K. Adipokinetic hormone enhances CarE-mediated chlorpyrifos resistance in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Insect Mol. Biol. 2020, 29, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.X.; Lin, Y.B.; Wang, R.M.; Li, Q.L.; Baerson, S.R.; Chen, L.; Zeng, R.S.; Song, Y.Y. Olfactory perception of herbivore-induced plant volatiles elicits counter-defenses in larvae of the tobacco cutworm. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scoy, A.R.; Yue, M.; Deng, X.; Tjeerdema, R. Environmental fate and toxicology of methomyl. Rev. Environ. Contam. T. 2013, 222, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, K.R.; Williams, W.M.; Mackay, D.; Purdy, J.; Giddings, J.M.; Giesy, J.P. Properties and uses of chlorpyrifos in the United States. Rev. Environ. Contam. T. 2014, 231, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Shi, H.; Gao, X.; Liang, P. Characterization of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase genes and their possible roles in multi-insecticide resistance in Plutella xylostella (L.). Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israni, B.; Wouters, F.C.; Luck, K.; Seibel, E.; Ahn, S.J.; Paetz, C.; Reinert, M.; Vogel, H.; Erb, M.; Heckel, D.G.; et al. The Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda Utilizes Specific UDP-Glycosyltransferases to Inactivate Maize Defensive Benzoxazinoids. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 604754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Fan, H.; Hu, R.; Huang, Y.; Sheng, C.W.; Cao, H.Q.; Wang, G.R.; Jiang, X.C. Characterization of core maize volatiles induced by Spodoptera frugiperda that alter the mating-mediated approach-avoidance behaviors of Mythimna separate. J. Integr. Agr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laothawornkitkul, J.; Taylor, J.E.; Paul, N.D.; Nicholashewitt, C. Biogenic volatile organic compounds in the Earth system. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takabayashi, J.; Shiojiri, K. Multifunctionality of herbivoryinduced plant volatiles in chemical communication in tritrophic interactions. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2019, 32, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch-Mani, B.; Baccelli, I.; Luna, E.; Flors, V. Defense Priming: An adaptive part of induced resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljbory, Z.; Chen, M.S. Indirect plant defense against insect herbivores: a review. Insect Sci. 2018, 25, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmisch, S.; McCormick, A.; Günther, J.; Schmidt, A.; Boeckler, G.A.; Gershenzon, J.; Unsicker, S.B.; Koellner, T.G. Herbivore-induced poplar cytochrome P450 enzymes of the CYP71 family convert aldoximes to nitriles which repel a generalist caterpillar. Plant J. 2014, 80, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, H.; Desurmont, G.A.; Cristescu, S.M.; van Dam, N.M. Herbivore-induced plant volatiles accurately predict history of coexistence, diet breadth, and feeding mode of herbivores. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Desurmont, G.; Degen, T.; Zhou, G.; Laplanche, D.; Henryk, L. Combined use of herbivore-induced plant volatiles and sex pheromones for mate location in braconid parasitoids. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasaki, E.; Drizou, F.; Milonas, P.G. Electrophysiological and oviposition responses of Ttuta absoluta females to herbivore-induced volatiles in tomato plants. J. Chem. Ecol. 2018, 44, 288–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frago, E.; Mala, M.; Weldegergis, B.T.; Yang, C.; Mclean, A.; Godfray, H.; Charles, J.; Gols, R.; Dicke, M. Symbionts protect aphids from parasitic wasps by attenuating herbivore-induced plant volatiles. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.K.; Zeng, R. Insect response to plant defensive protease inhibitors. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015, 60, 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Heidel-Fischer, H.M.; Vogel, H. Molecular mechanisms of insect adaptation to plant secondary compounds. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 8, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, C.; Zimmer, C.T.; Riveron, J.M.; Wilding, C.S.; Wondji, C.S.; Kaussmann, M.; Field, L.M.; Williamson, M.S.; Nauen, R. Gene amplification and microsatellite polymorphism underlie a recent insect host shift. PNAS. 2013, 110, 19460–19465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudo, M.; Hilliou, F.; Fricaux, T.; Audant, P.; Feyereisen, R.; Le, G.G. Cytochrome P450s from the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda): responses to plant allelochemicals and pesticides. Insect Mol. Biol. 2015, 24, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, R. Insect CYP genes and P450 enzymes. Insect Biochem. Molec. 2012, 236–316. [Google Scholar]

- Jurgen, E.; Fabiola, C.C.; Chinmay, D.; T. ; Li, T.; Marie, E.; Martin, H. Early transcriptome analyses of Z-3-hexenol-treated Zea mays revealed distinct transcriptional networks and anti-herbivore defense potential of green leaf volatiles. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e77465. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).