1. Introduction

Throughout the extensive evolutionary journey of insects, the cycles of day and night, seasonal variations, and other terrestrial changes have led to the development of rhythmic behaviors, commonly referred to as biological clocks [

1,

2]. In moths, the primary rhythmic activities during their developmental stages include pupation, eclosion, mating, and oviposition. Additionally, the behavioral rhythms exhibited by different insect species vary significantly. Even within the same species, the consistency of behavioral rhythms is influenced by numerous external factors. These variations in insect behavioral rhythms reflect their adaptations to diverse environments and contribute to the extensive variety within moth species [

3,

4].

The fall armyworm (FAW),

Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), is a significant migratory pest that affects crops globally and poses a considerable risk to food security in China [

5]. Current research on the biology and rhythmic patterns of FAW primarily investigates mating, oviposition, hatching, adult lifespan, and how various feeding conditions impact its growth and development [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Significant advancements have also been made in understanding the interactions between FAW and its host plants. Studies have demonstrated that the selectivity and fitness of FAW in relation to different hosts, along with oviposition preferences and the influence of feeding on various host plants, considerably affect its growth and development [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Although FAW has an extensive range of hosts in the Huang-Huai-Hai region, it predominantly inflicts damage on maize. Insects feeding on different host plants may experience alterations in their circadian rhythms, and even minor variations in these rhythms can influence gene expression among individuals and impact a range of reproductive behaviors [

15,

16]. Understanding how these changes might influence the FAW's ovarian development and subsequent reproductive success is crucial for developing effective control strategies. In this study, we aimed to investigate the ovarian development of FAW fed on different host plants and assess any potential variations in their circadian rhythms that could impact their reproductive behaviors. The results of this study will provide valuable insights into the biology of FAW and contribute to the development of more targeted and sustainable pest management practices.

In this study, FAW larvae were continuously reared on the widely cultivated grain corn Zhengdan 958 and sweet waxy corn Zhenghuangnuo for over nine generations in laboratory. The study aimed to elucit the impact of sweet and normal maize on adult behavioral rhythms and compare the rhythms across various strains, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for whether the sweet corn can be serve as a lure for trapping this pest species.

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Different Maize Cultivars on the Emergence Rhythm of the First Generation of S. frugiperda Strain

The emergence times of various S. frugiperda strains varied, yet a distinct peak was observed. For the first generation of the Zhengdan 958 strain and the artificial diet feed strain, the emergence peak occurred between 0:00 and 1:00, while the first generation of the Zhenghuangnuo strain peaked from 23:00 to 0:00. The emergence peak of the Zhenghuangnuo strain occurred earlier than that of the grain corn strain. All three strains exhibited their emergence peaks during the dark period .

The emergence duration for each strain was further recorded. The Zhengdan 958 strain and the artificial diet feed strain exhibited emergence periods of approximately two hours, centered around their respective peaks. The Zhenghuangnuo strain, on the other hand, displayed a slightly longer emergence period, spanning nearly three hours around its peak. The grain corn strain showed the most variable emergence times, with individuals emerging over a broader window of several hours, primarily during the dark period. The synchronization of emergence within strains, especially during the dark phase, suggests a potential for reduced predation risk and increased mating opportunities (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

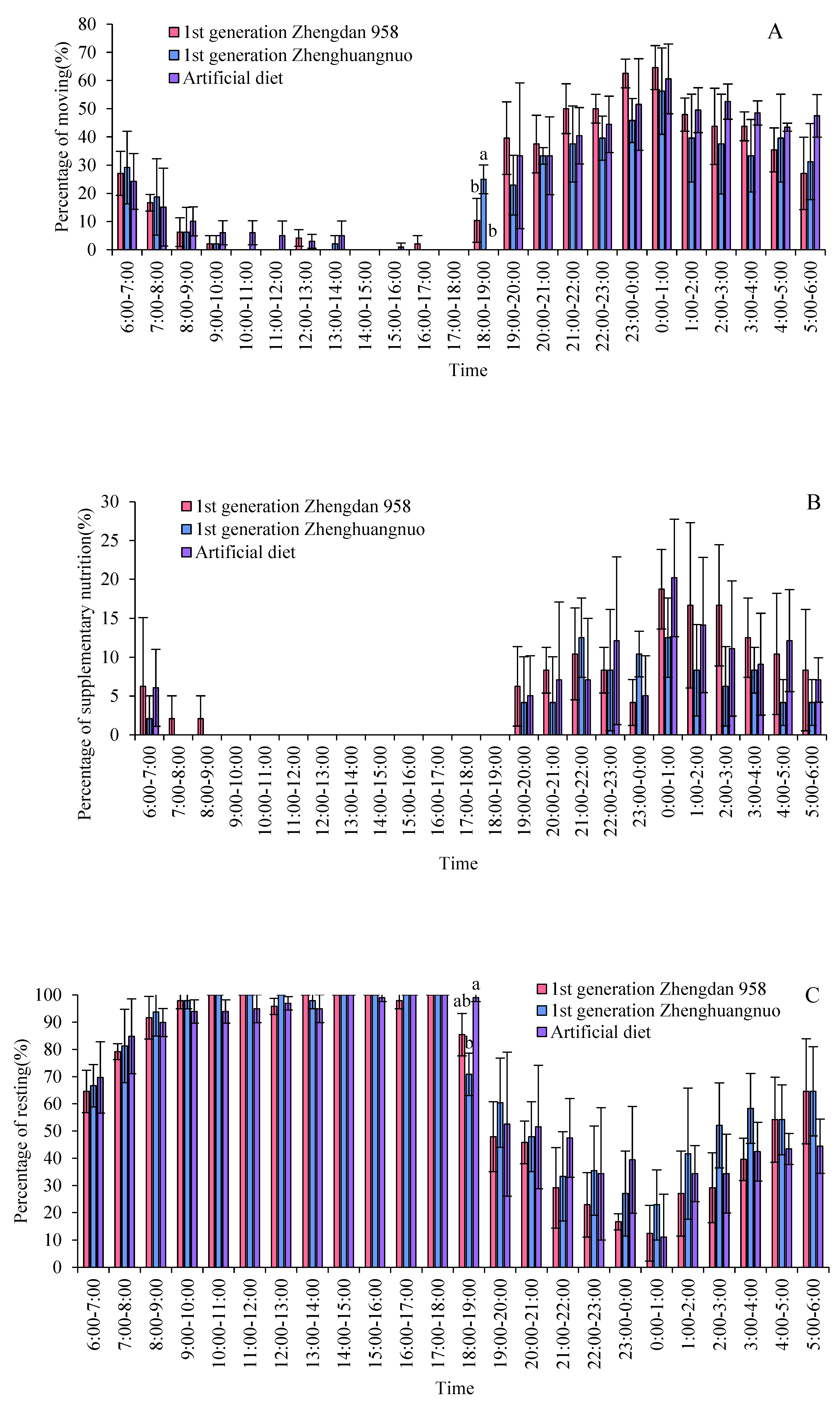

2.2. Impact of Different Maize Cultivars on the Activity Patterns of FAW Adults in the First Generation Strain

During the light-dark cycle, different strains of the fall armyworm exhibit distinct activity patterns, accompanied by significant periods of rest. The activity levels of all three strains significantly decrease after 8:00. Notably, the activity of the first generation of Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains significantly increases at 18:00, while the artificially fed strain reaches its peak activity at 19:00. During the dark period, each strain shows a pattern of gradually increasing activity followed by a decline, with the artificially fed strain having a more gradual decrease. Among all strains, the highest frequency of activity occurs between 00:00 and 01:00. Before the onset of the dark period, the time at which adult activity begins to rise varies among the three strains: the Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains begin to rise 2 hours before the dark period, while the artificially fed strain rises 1 hour before. The resting behavior of these adult strains is inversely proportional to the amount of activity, with higher frequencies during the light period and lower frequencies during the dark period.

Supplementary nutritional behavior among adult S. frugiperda primarily occurred in darkness, with minimal activity during the light hours. The peak for supplementary feeding was between 00:00 and 01:00 for both the first generation of the Zhengdan 958 strain and the artificial diet feed strain, whereas the Zhenghuangnuo strain peaked at 21:00 to 22:00 and again at 00:00 to 01:00.

Additionally, the frequency of supplementary feeding was notably higher in the Zhengdan 958 strain compared to the other two strains, suggesting potential differences in nutritional requirements or feeding habits among these variants. For all strains, the amount of food consumed during the supplementary feeding periods was consistent across replicates, indicating a reliable and reproducible feeding pattern.

All three strains exhibited a distinct peak in mating behavior: the Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains peaked between 23:00 and 00:00, while the artificial diet strain peaked between 00:00 and 01:00. Spawning peaks were observed as follows: the first generation Zhengdan 958 strain had one peak (22:00 to 23:00), the first generation of Zhenghuangnuo strain had two peaks (21:00 to 22:00 and 22:00 to 23:00), and the artificial diet strain also had two peaks (19:00 to 20:00 and 22:00 to 23:00). The highest spawning frequency for each strain was recorded between 22:00 and 23:00 (

Figure 3).

In addition, the ovarian development of the insects was monitored, revealing that all strains reached maximum ovarian maturity during their respective spawning peaks. The ovarian development index for each strain correlated positively with their spawning frequencies, indicating a strong relationship between ovarian maturity and reproductive activity.

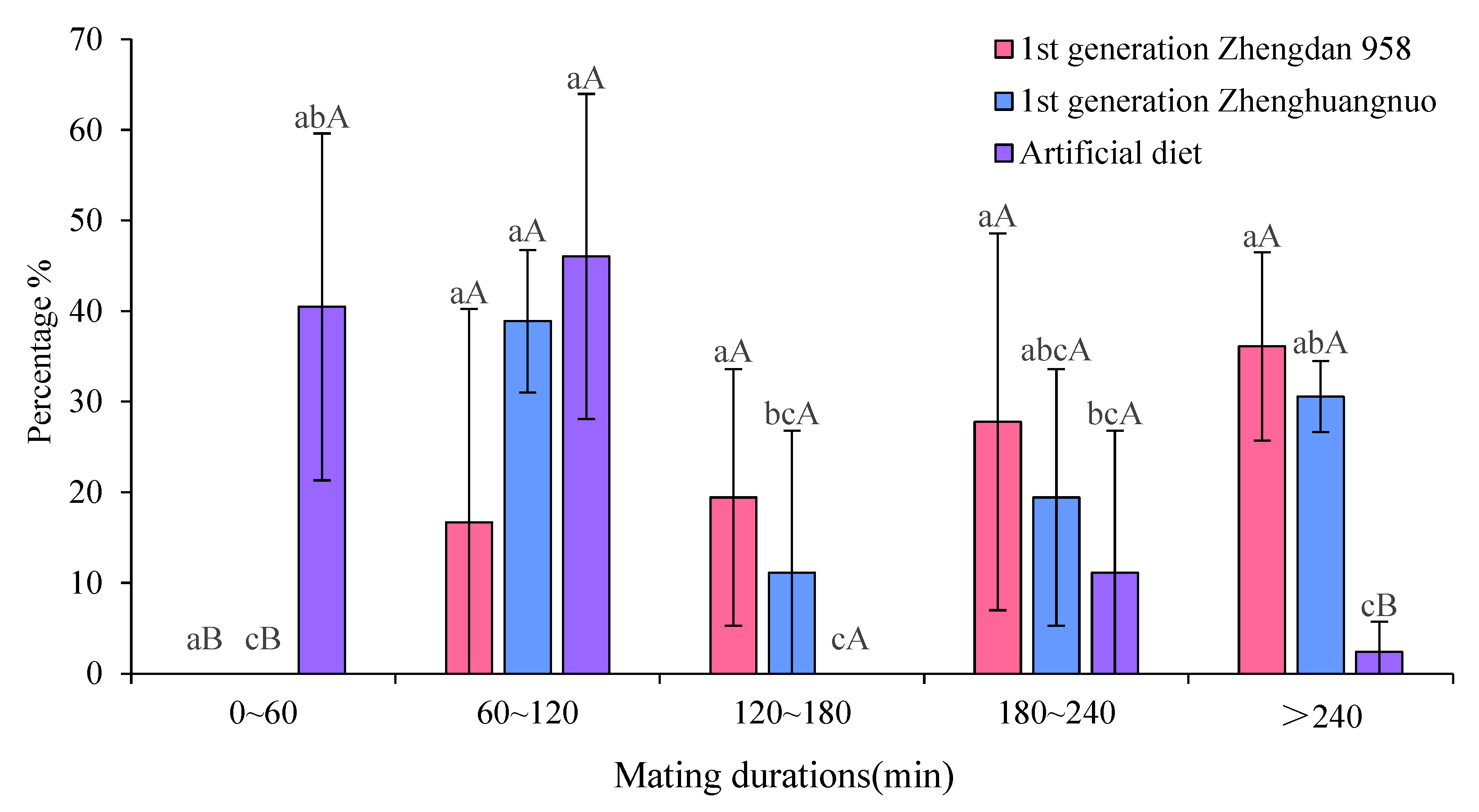

2.3. Impact of Various Maize Cultivars on Mating Duration of Adult S. frugiperda from the First- Generation Strain

The mating duration for

S. frugiperda across the three strains was at least 60 minutes. Specifically, the first generation of Zhengdan 958 averaged 206.18 ± 90.43 minutes, the first generation of Zhenghuangnuo averaged 189.90 ± 116.23 minutes, and the artificial diet strain averaged 83.35 ± 52.32 minutes. The mating times for both the first generation Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains were significantly longer than that of the artificial diet strain (

P = 0.002) (

Figure 4).

Across the three strains, the Zhengdan 958 strain exhibited an average copulation frequency of 1.67 ± 0.71 times per female, while the Zhenghuangnuo strain averaged 1.58 ± 0.65 times per female. The artificial diet strain showed a slightly lower frequency at 1.42 ± 0.50 times per female. However, no statistically significant differences were observed among the strains in terms of copulation frequency ( P = 0.347) (

Figure 4).

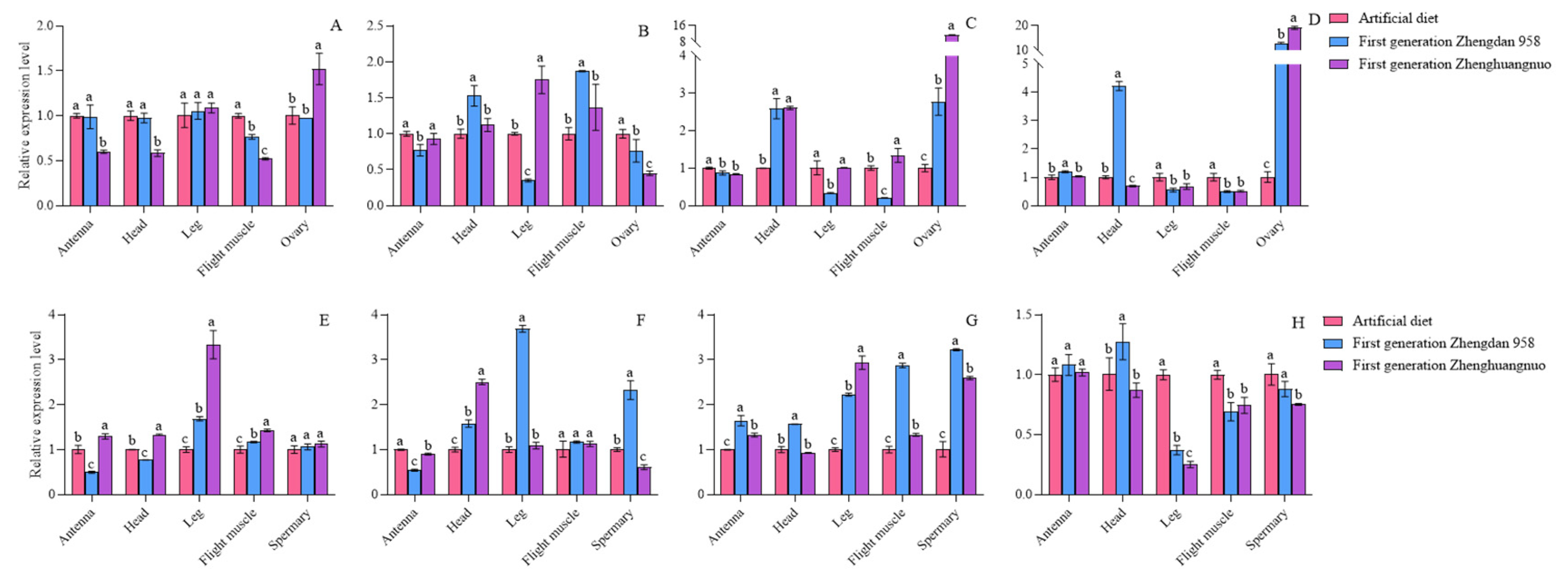

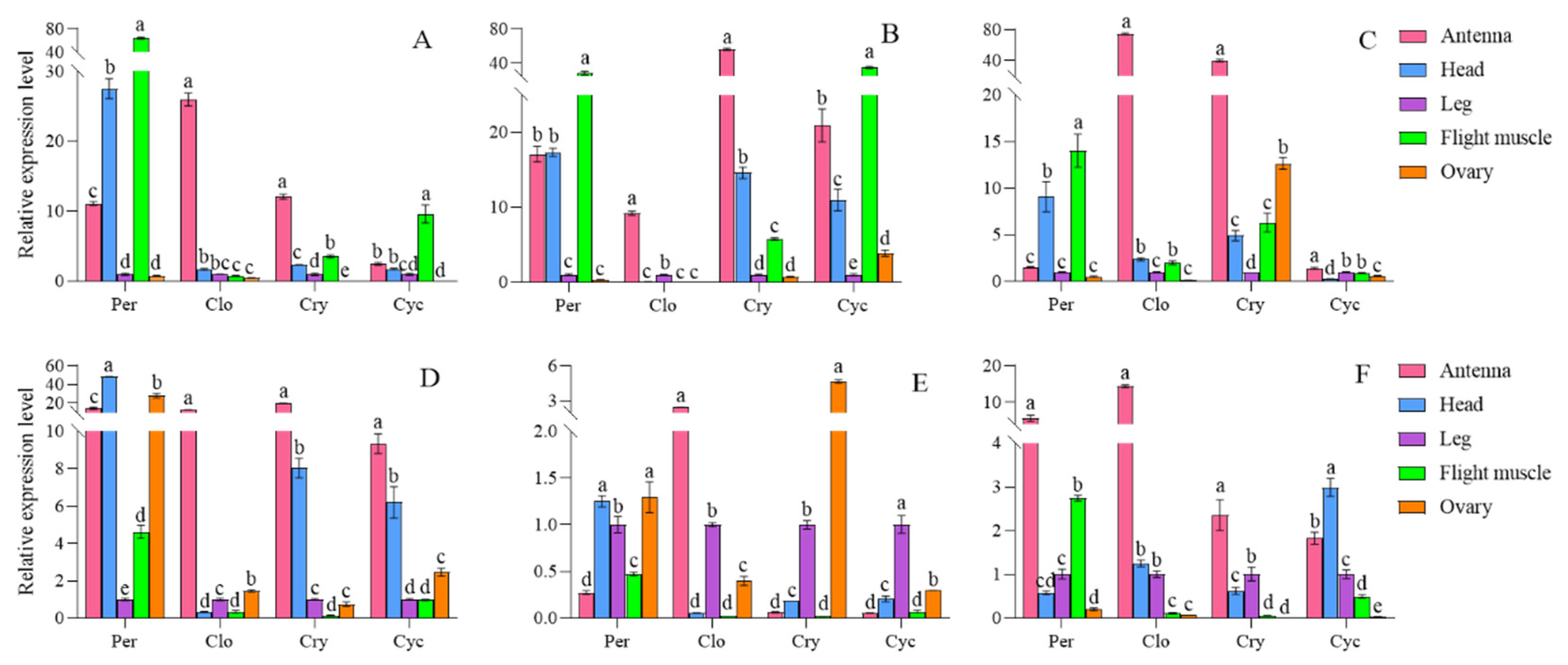

2.4. Impact of Various Maize Cultivars on the Expression of Rhythm Genes in the First Generation of S. frugiperda Adults

The expression levels of the four circadian clock genes varied among different strains. In comparison to the females of the artificial diet strain, the per gene expression was reduced in the antennae, head, flight muscle, and ovary of the first generation of the Zhengdan 958 strain, while it increased in the leg. For the first generation of the Zhenghuangnuo strain, per gene expression decreased in the antennae, head, and flight muscle, but rose in the leg and ovary. The clk gene expression was lower in the antennae, leg, and ovary of the first generation of the Zhengdan 958 strain, but higher in the head and flight muscle. In the first generation of the Zhenghuangnuo strain, clk expression decreased in the antennae and ovary, while it increased in the head, leg, and flight muscle. The cry gene expression diminished in the antennae, leg, and flight muscle of the first generation of the Zhengdan 958 strain, while it increased in the head and ovary. Similarly, in the first generation of the Zhenghuangnuo strain, cry gene expression decreased in the antennae and leg, but increased in the head, flight muscle, and ovary. The cry gene expression rose in the antennae, head, and ovary of the first generation of the Zhengdan 958 strain, and also increased in the head and ovary. In contrast, the expression level of cry in the antennae and ovaries of the first generation of the Zhenghuangnuo strain increased, while it decreased in the head, leg, and flight muscle.

In comparison to the male of the artificial diet strain, the expression of the per gene was reduced in the antenna and head of the first generation of Zhengdan 958 strain, while it was elevated in the leg, flight muscle, and testis. Conversely, the expression level rose across all regions in the first generation of Zhenghuangnuo strain. For the clk gene, its expression decreased in the antennae of the first generation Zhengdan 958 strain but increased in the head, leg, flight muscle, and testis. In the first generation of Zhenghuangnuo strain, the expression of clk diminished in both the antennae and testis, but heightened in the head, leg, and flight muscle. The cry gene exhibited an increase in expression throughout all parts of the first generation Zhengdan 958 strain. Similarly, in the first generation of Zhenghuangnuo strain, cry expression rose in the antennae, leg, flight muscle, and testis, while it dropped in the head. The cyc gene's expression increased in the antenna and head of the first generation Zhengdan 958 strain, but decreased in the leg, flight muscle, and testis. In contrast, the expression of cyc was heightened in the antennae of the first generation Zhenghuangnuo strain, yet reduced in the head, leg, flight muscle, and testis.

When comparing the artificial diet strain to the first generation of both Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains, variations in circadian gene expression levels were observed, with significant differences in certain genes across the strains. Notably, the

cry gene expression in the ovary of the first generation Zhenghuangnuo strain was found to be 11.39 times greater than that of the artificial diet strain. The

cyc gene expression in the ovaries of the first generation Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains was 12.94 times and 19.08 times higher, respectively, than in the artificial diet strain, although most expression levels fluctuated between 0.5 and 2 times (

Figure 5).

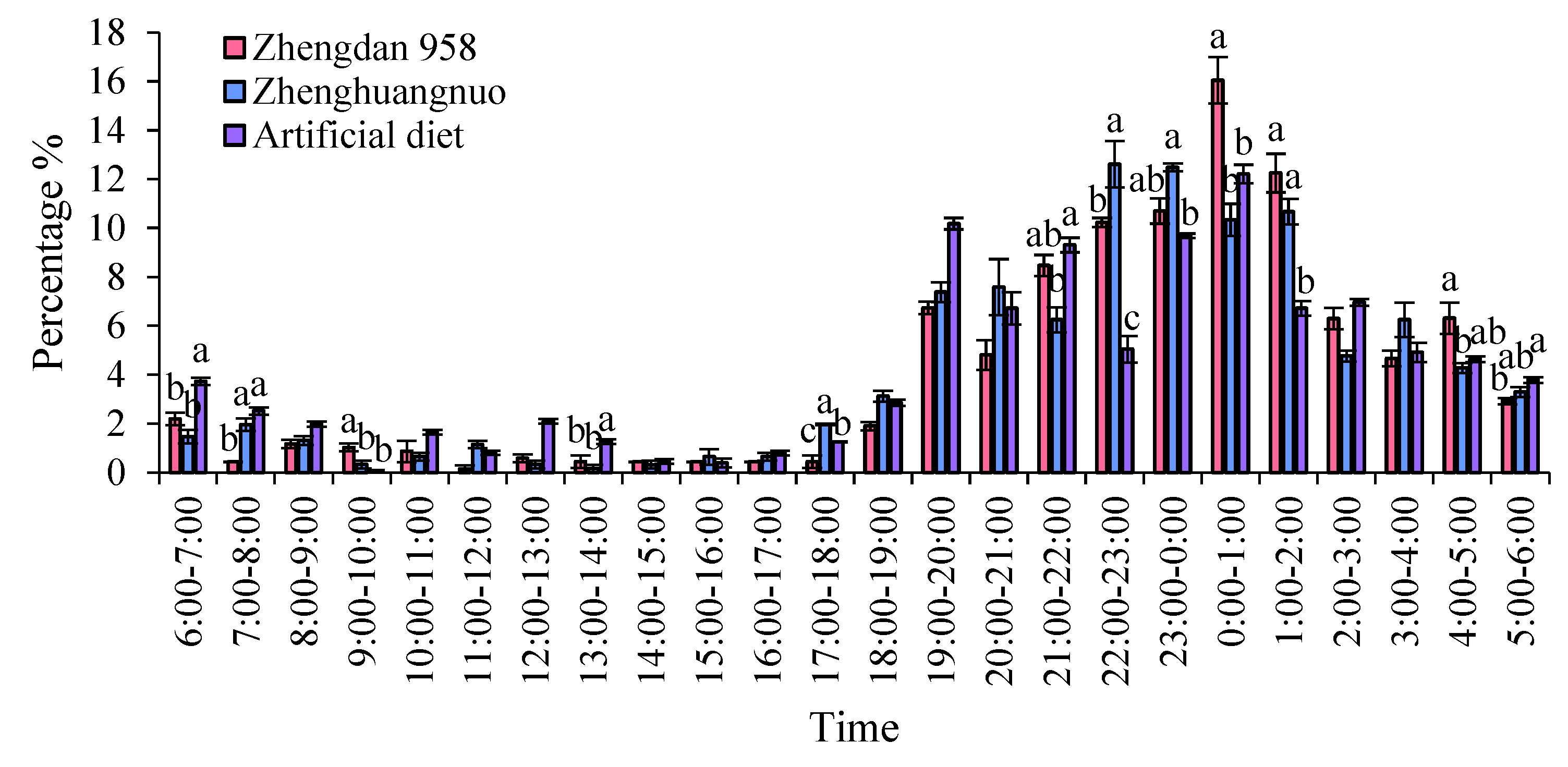

2.5. Impact of Various Maize Cultivars on the Emergence Timing of S. frugiperda

Different strains of

S. frugiperda exhibited varying emergence times, although a clear peak was noted. The emergence peaks for the Zhengdan 958 strain, Zhenghuangnuo strain, and artificial diet feed strain occurred between 0:00 and 1:00, 22:00 and 23:00, and 0:00 and 1:00, respectively. All three strains peaked during the dark period, but the Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains showed a more concentrated emergence, while the artificial diet strain had a more scattered emergence. Notably, the emergence peak of the Zhenghuangnuo strain was 2 hours earlier than that of both the Zhengdan 958 strain and the artificial diet strain (

Figure 6).

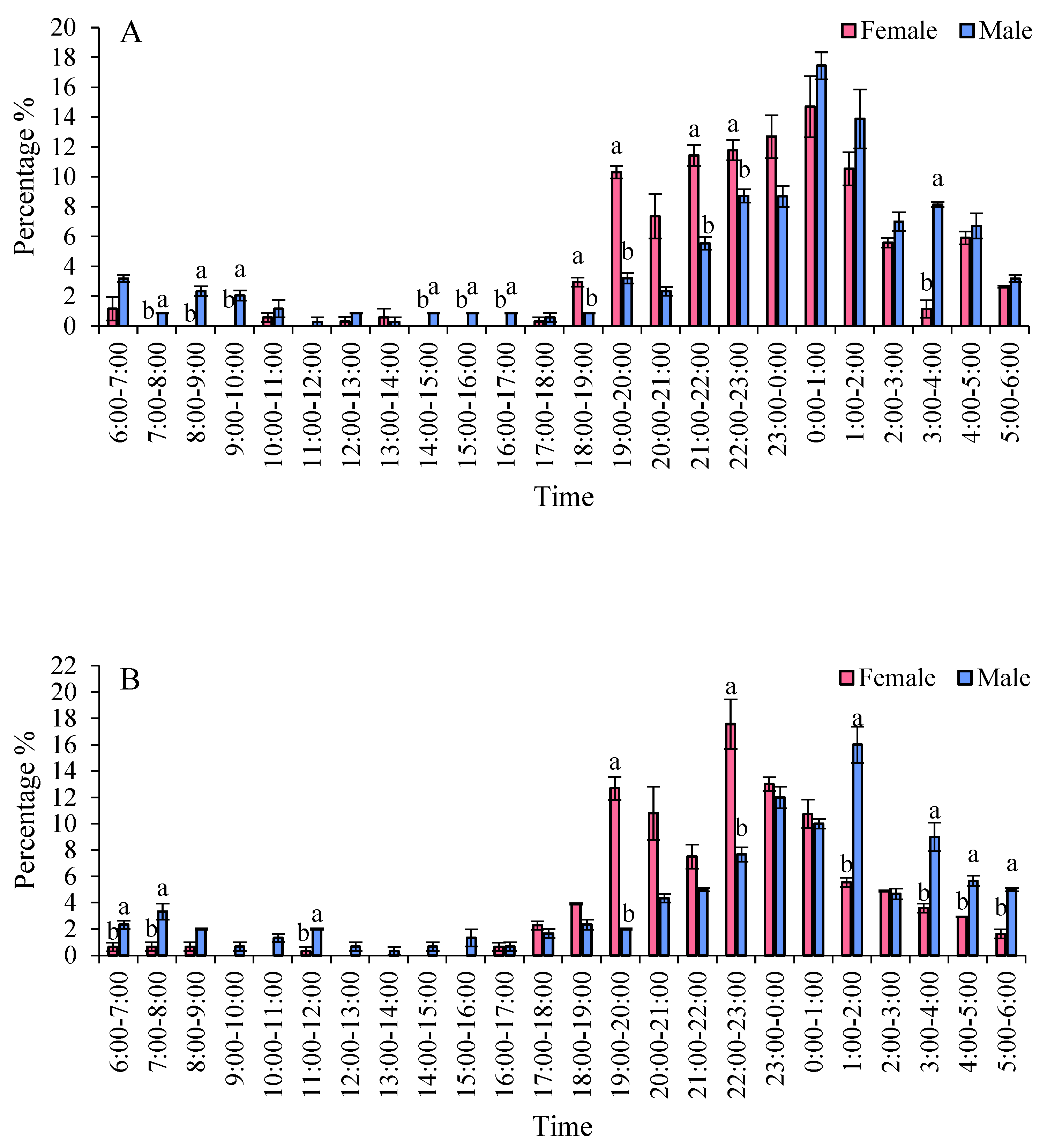

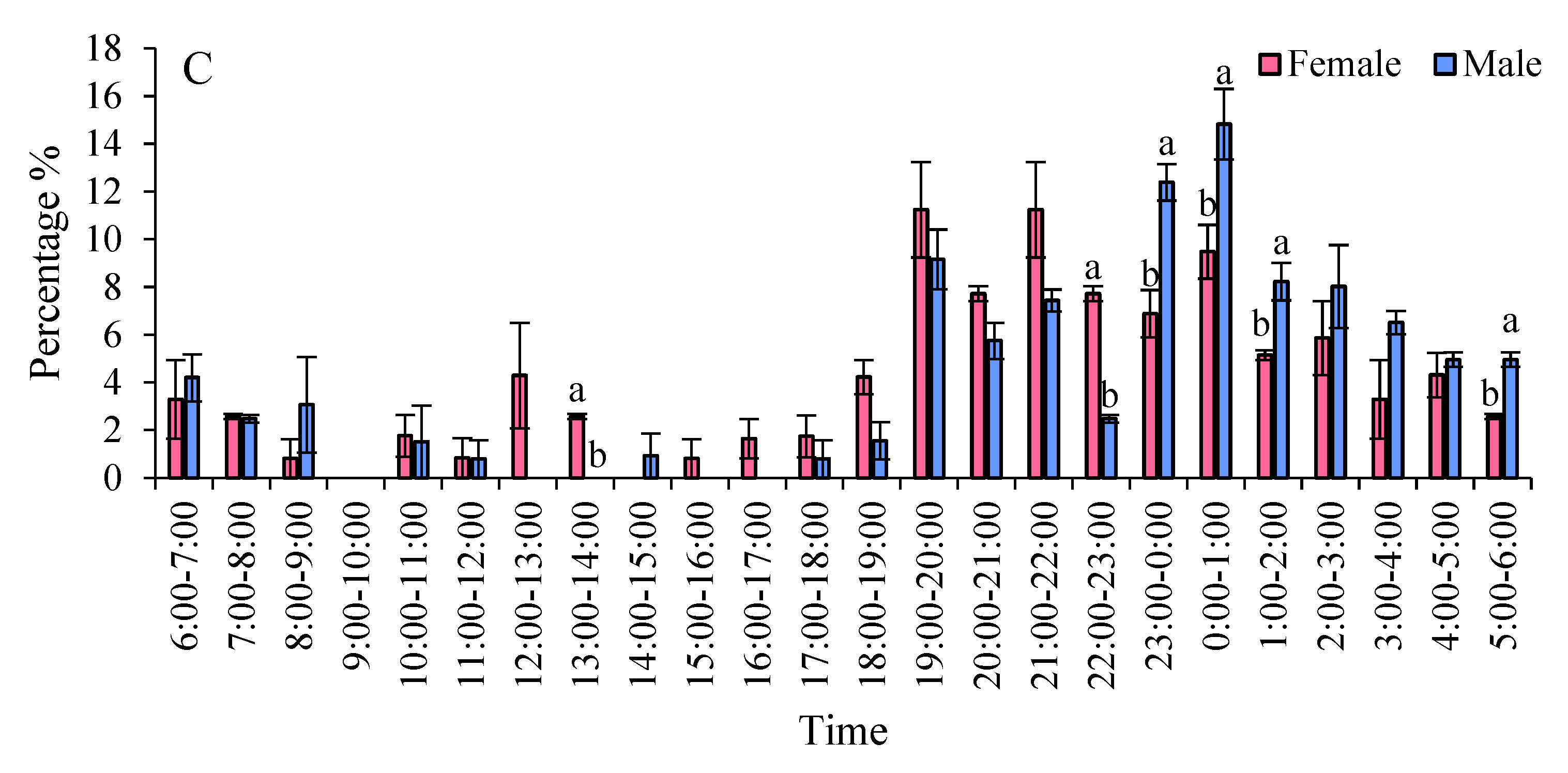

2.6. Eclosion Patterns of Male and Female Adults Across Different Strains

The eclosion peaks of

S. frugiperda varied among different strains, with females emerging earlier than males. In two maize strains, the eclosion of females was ahead of that of males. Specifically, in the Zhengdan 958 strain, the eclosion peaks for males and females occurred between 18:00 and 19:00, and from 00:00 to 01:00, respectively. During the time frame of 18:00 to 01:00, the eclosion rates were 81.26% for males and 46.80% for females. For the Zhenghuangnuo strain, the peak eclosion times were 19:00 to 20:00 for males and 22:00 to 23:00, followed by 23:00 to 00:00 and 01:00 to 02:00 for females. The eclosion percentages between 19:00 and 23:00 were 48.53% for males and 18.87% for females. In the artificial diet strain, the peaks occurred from 19:00 to 20:00 for males and from 21:00 to 22:00, with females emerging from 19:00 to 20:00 and 00:00 to 01:00. The eclosion rates during 19:00 to 22:00 were 29.91% for males and 22.13% for female adults (

Figure 7).

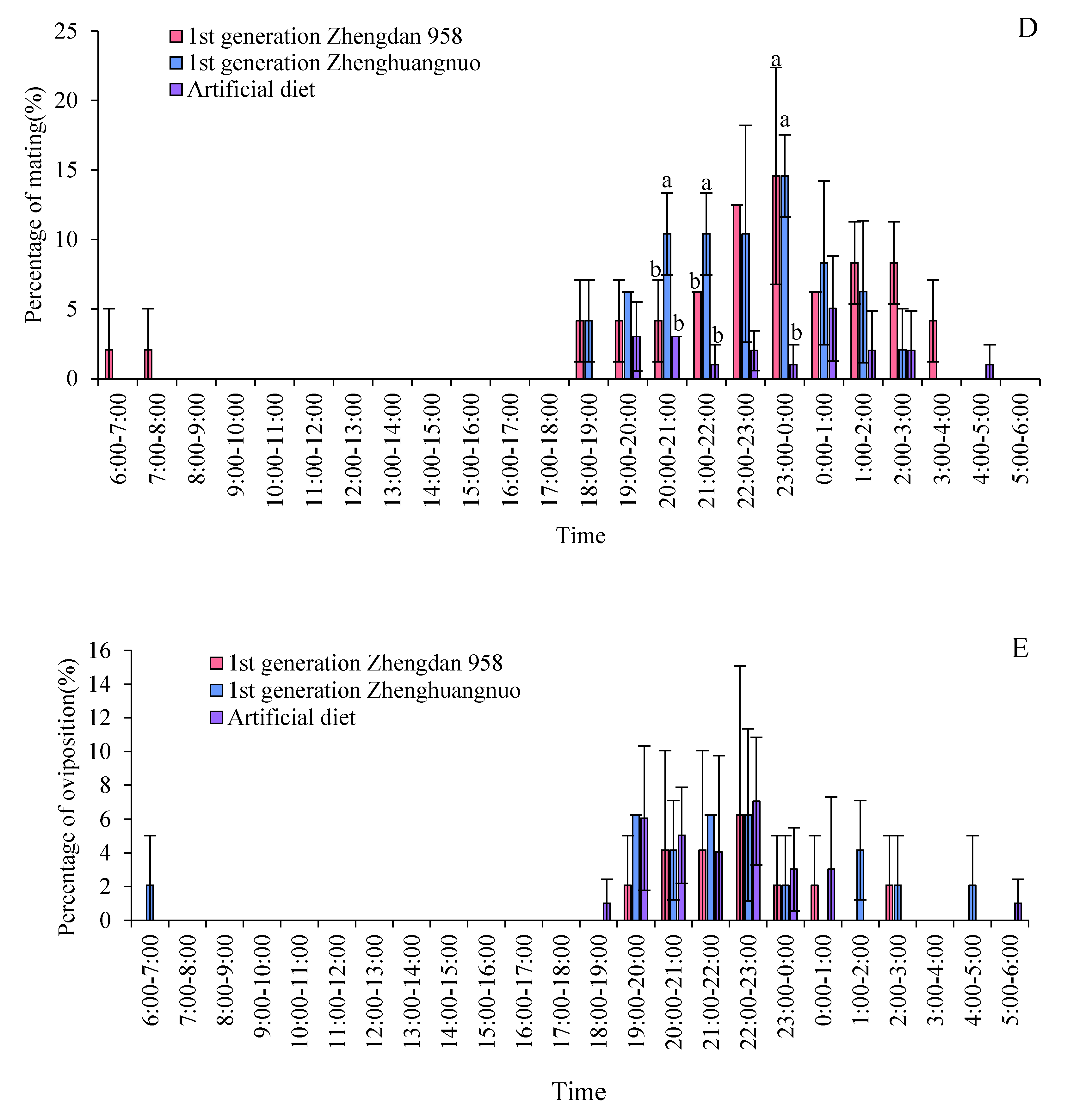

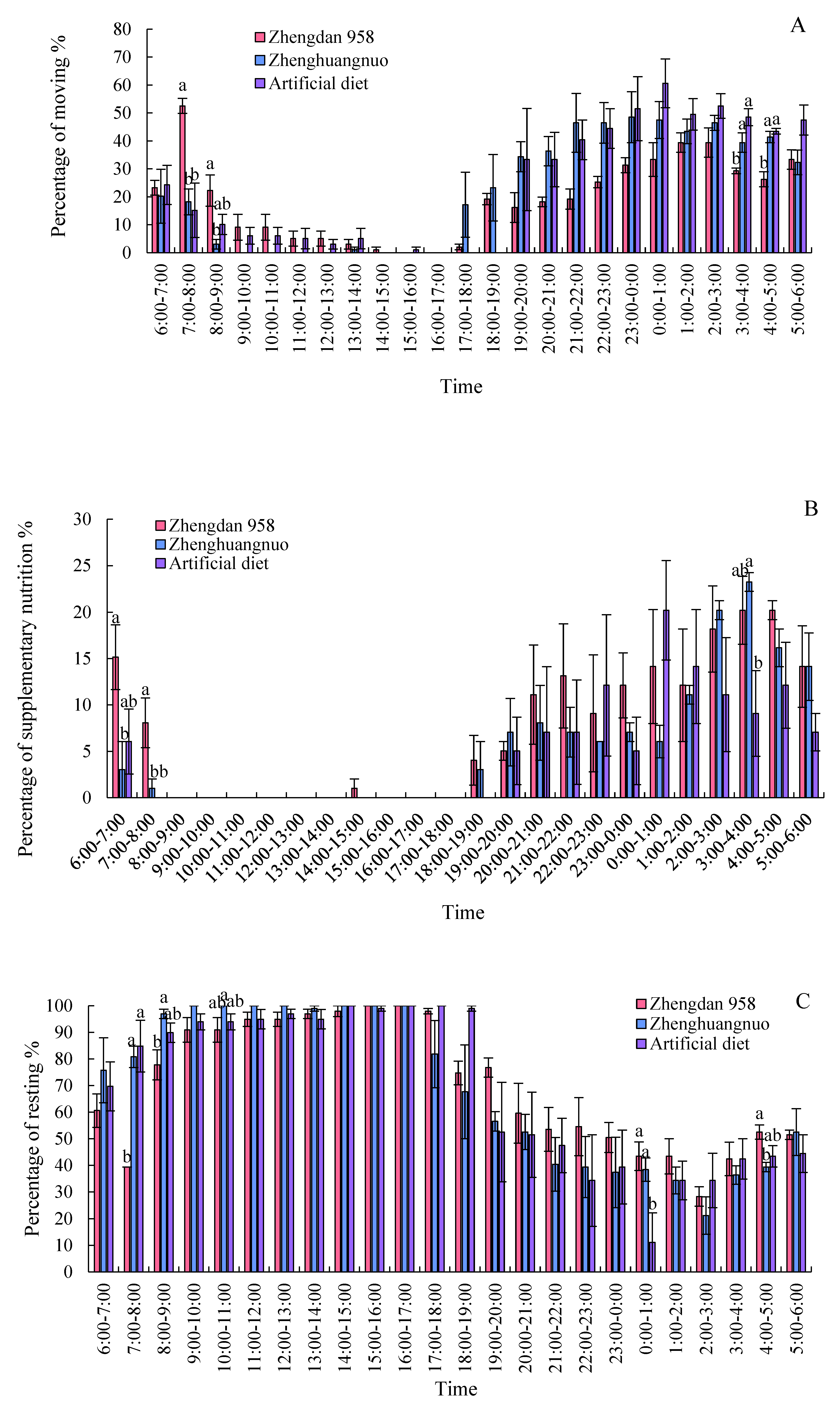

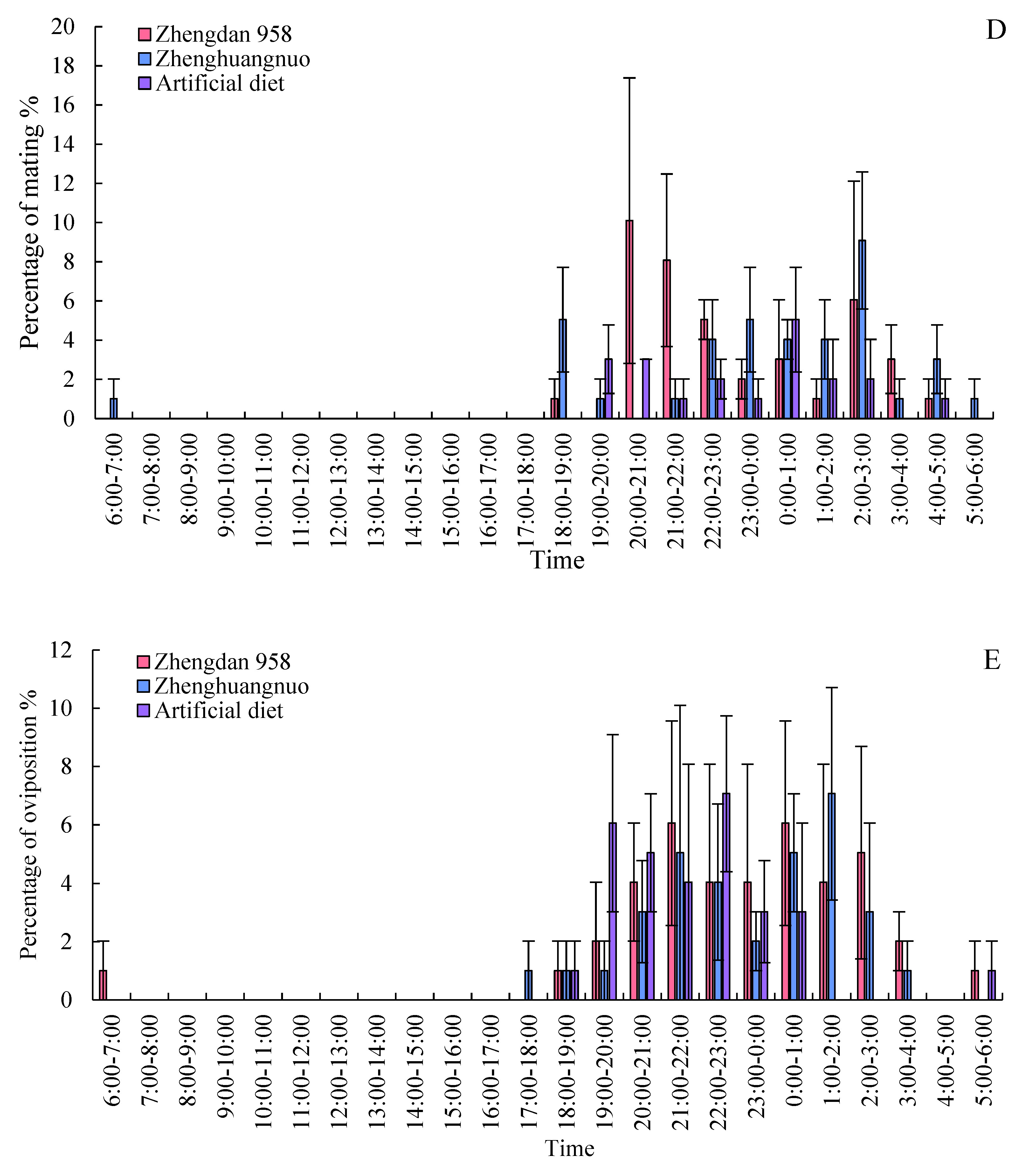

2.7. Impact of Various Maize Cultivars on the Circadian Activity Patterns of S. frugiperda Adults

Different strains of S. frugiperda exhibited a resting phase during light periods and an active phase during dark periods. The activity levels of all three strains significantly declined starting at 8:00 and rose notably after 19:00. However, the Zhengdan 958 strain displayed a pronounced peak of activity between 7:00 and 8:00, marking the highest activity time of the day. The Zhenghuangnuo strain's activity frequency initially increased slowly before stabilizing during the dark period. In contrast, the artificial diet feed strain's activity frequency showed a gradual rise followed by a decrease in the dark period, peaking between 0:00 and 1:00. All three strains began to show increased activity before the onset of darkness, although the timings varied: Zhengdan 958 at 2 hours, Zhenghuangnuo at 3 hours, and the artificial diet strain at 1 hour before the lights went out. The resting behavior of the adults in these strains was inversely related to their activity patterns, revealing higher resting frequencies during light periods and lower during dark periods.

Supplementary feeding behaviors in adult S. frugiperda predominantly occurred during dark periods, with negligible activity in light periods. The peaks for supplementary feeding were recorded for the Zhengdan 958 strain from 3:00 to 5:00, the Zhenghuangnuo strain from 3:00 to 4:00, and the artificial diet feed strain from 0:00 to 1:00.

Both the Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains exhibited two mating peaks, whereas the artificial diet feed strain showed a single noticeable peak. The mating peaks for the Zhengdan 958 strain occurred between 20:00-21:00 and 2:00-3:00, accounting for 10.10% and 6.06% of total mating events, respectively. The Zhenghuangnuo strain peaked at 18:00-19:00 and 2:00-3:00, representing 5.05% and 9.09%, respectively. The artificial diet feed strain's mating peak was from 0:00 to 1:00, making up 5.05%. The mating patterns of the strains reared on maize were more concentrated, while those of the artificial diet feed strain were more dispersed.

In the strains of Zhengdan 958, Zhenghuangnuo, and the artificial diet feed, there were three spawning peaks (from 21:00 to 22:00, 00:00 to 01:00, and 02:00 to 03:00), two spawning peaks (from 21:00 to 22:00 and 01:00 to 02:00), and two spawning peaks (from 19:00 to 20:00 and 22:00 to 23:00), respectively. The spawning peaks for the two maize strains occurred approximately two hours later than those of the artificial diet feed strain (

Figure 8).

2.8. Effects of Different Maize Cultivars on Mating Duration of Adults S. frugiperda

The average mating duration for

S. frugiperda across the three strains was at least 60 minutes. Specifically, the average mating times were 143.73 ± 15.53 minutes for Zhengdan 958, 1286.45 ± 20.66 minutes for Zhenghuangnuo, and 70.87 ± 2.45 minutes for the artificial diet strain. The mating duration for Zhenghuangnuo strains were significantly longer than that of the Zhengdan 958 and artificial diet strain (

P = 0.02) (

Figure 9).

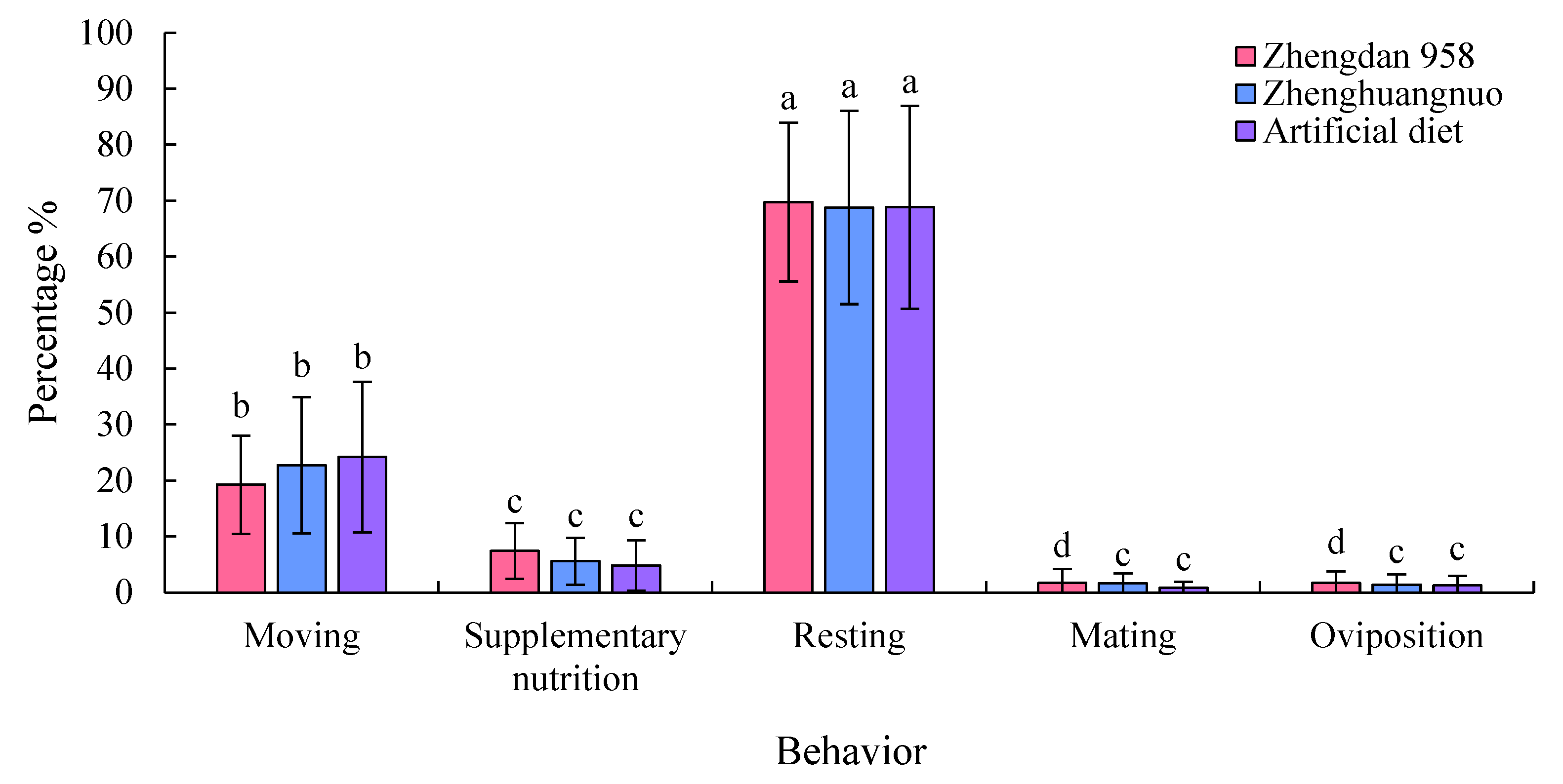

2.9. Daily Time Allocation of Adult Behavior of S. frugiperda

The adult

S. frugiperda exhibited the highest proportion of resting behavior among the various strains, which was significantly greater than that of other behaviors (

P < 0.05). This was followed by moving behavior, which was also significantly more prevalent than supplementary nutrition, mating, and oviposition behaviors (

P < 0.05). Specifically, the resting behavior proportions for the Zhengdan 958, Zhenghuangnuo, and artificial diet strains were 69.74%, 68.77%, and 68.86%, respectively. The three strains showed limited mating and oviposition behaviors, and there were no significant differences in the distribution of various behaviors across the strains (

Figure 10).

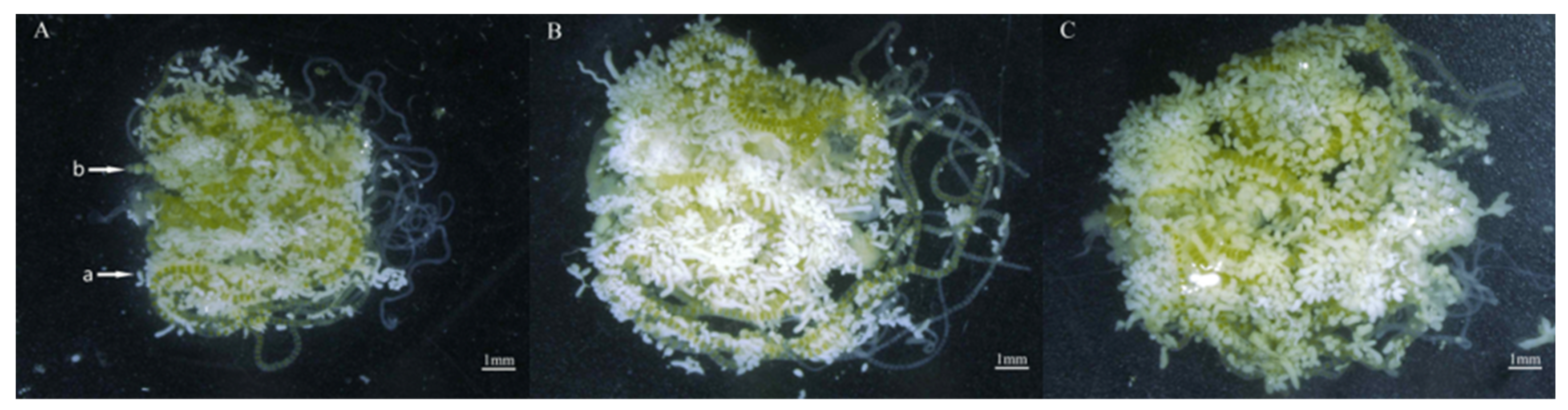

2.10. Effects of Different Maize Cultivars on Ovarian Development of S. frugiperda

After nine generations of continuous feeding on two different cultivars of corn, the newly emerged female moths were examined through ovarian dissection. The ovary weight was 13.80, 22.10 and 17.40,The fat body weight was 12.20,13.80 and 6.7,Fat body content % was 35.22%, 43.36% and 31.54%, Ovarian tube length was 39.95,41.98 and 35.66, for Zhengdan 958, Zhenghuangnuo and Artificial diet respectively.The results indicated that the corn cultivars did not significantly influence the ovarian development stage of

S. frugiperda. Both strains of

S. frugiperda, when fed on corn leaves and an artificial diet, displayed an ovarian development grade of I (the transparent milky stage). However, The strain of sweet corn exhibited superior ovarian tube length compared with the other two strains. Conversely, the fat body weight and fat body content of the sweet and normal corn strain were significantly heavier than those of the artificial diet strain (P < 0.05). (

Table 1,

Figure 11).

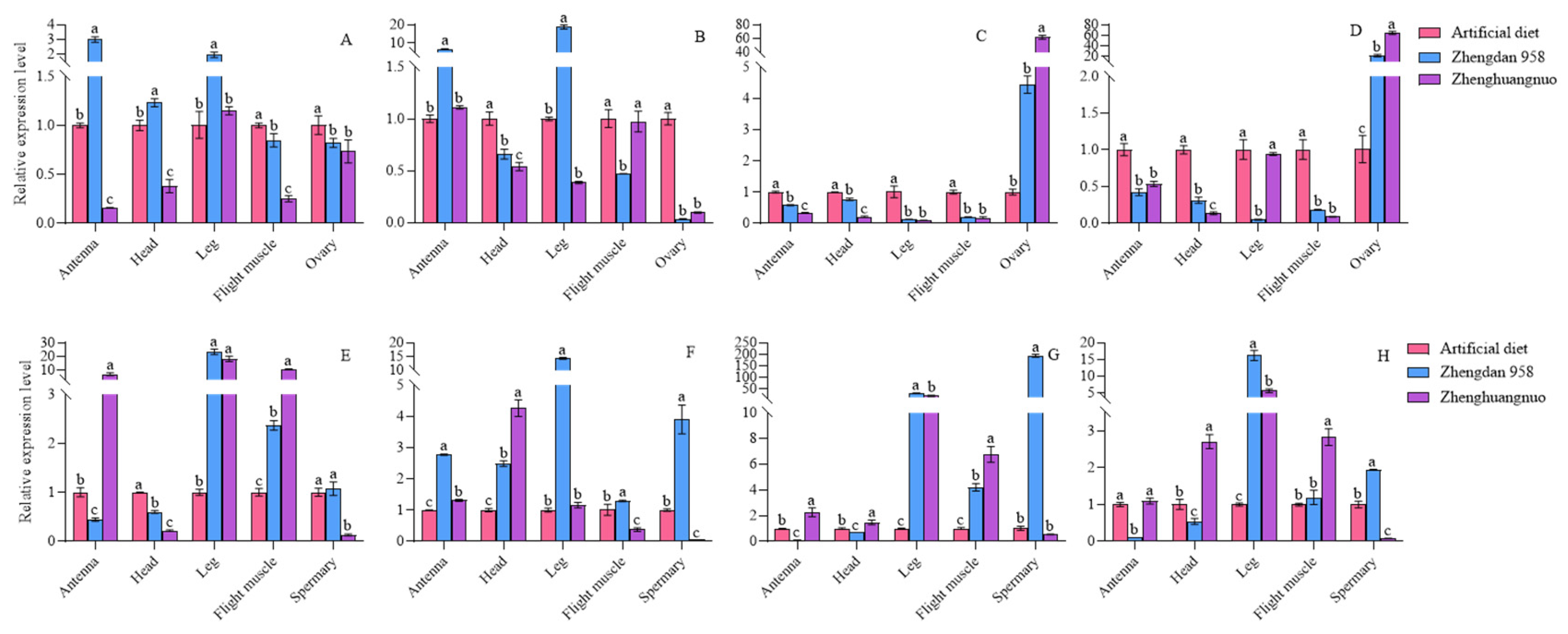

2.11. Effects of Different Maize Cultivars on the Expression of Rhythm Genes in Different Tissues of S. frugiperda Adult In Vitro by RT-qPCR

The expression levels of four circadian clock genes in various strains and tissues of S. frugiperda were examined using RT-qPCR. Significant differences were observed in the expression of per, clk, cry, and cyc genes across different strains and tissues. In the artificial diet strain, the per gene exhibited the highest expression in flight muscle, followed by the head and antennae. The clk and cry genes showed their highest expression in the antennae, while the cyc gene was predominantly expressed in the flight muscle. For male insects, the per gene had peak expression in the head, with the clk gene also highest in the antennae. The cry and cyc genes were most highly expressed in the antennae, followed by the head.

In the Zhengdan 958 strain, the per gene also showed the highest expression in flight muscle, followed by the head and antennae. The clk gene had its highest expression in the antennae, while the cry gene was most abundant in the antennae as well, followed by the head. The cyc gene peaked in the flight muscle, followed by the antennae and head. Additionally, the per gene's expression was highest in the testis, followed by the head. The clk gene had its highest expression in the antennae, the cry gene was most expressed in the testis, and the cyc gene peaked in the foot.

In the Zhenghuangnuo strain, the per gene exhibited the highest expression in flight muscles, followed closely by the head. The

clk,

cry, and

cyc genes showed their peak expression levels in the antennae. For males, the expression of

per,

clk, and

cry genes was also highest in the antennae, while the

cyc gene had its highest expression in the head, followed by the antennae. Across the three strains of

S. frugiperda, the four

circadian clock genes were predominantly expressed in the antennae and heads. The expression patterns of these

circadian clock genes in females were largely consistent across different strains. In males, the expression patterns of the artificial diet and Zhenghuangnuo strains were similar, differing from those observed in the Zhengdan 958 strain (

Figure 12).

The expression levels of the four circadian clock genes varied across different strains and anatomical regions. In comparison to females from the artificial diet strain, the per gene expression in the antennae, heads, and feet of the Zhengdan 958 strain was higher and lower in the flight muscles and ovaries. For the Zhenghuangnuo strain, expression levels of per gene decreased in the antennae, heads, flight muscles, and ovaries, but increased in the leg. The clk gene showed increased expression in the antennae and leg of the Zhengdan 958 strain, while it decreased in the head, flight muscle, and ovary. However, in the Zhenghuangnuo strain, clk gene expression was elevated in the antennae but reduced in the head, leg, flight muscle, and ovary. Both cry and cyc gene’ expression levels in the Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains decreased in the antennae, heads, leg, and flight muscle, while increasing in the ovary.

When compared to males from the artificial diet strain, the per gene expression in the antennae and heads of the Zhengdan 958 strain decreased, but increased in the feet, flight muscle, and testis. In the Zhenghuangnuo strain, expression levels were elevated in the antennae, leg, and flight muscles, while decreasing in the head and testis. The

clk gene expression rose across all tissues in the Zhengdan 958 strain. In the Zhenghuangnuo strain, it increased in the antennae, heads, and leg, while decreasing in the flight muscle and testis. The levels of

cry and

cyc genes were reduced in the antennae and heads of the Zhengdan 958 strain, yet they increased in the legs, flight muscles, and testes. In the Zhenghuangnuo strain, the expression was enhanced in the antennae, head, leg, and flight muscle, while it decreased in the testis (

Figure 13).

3. Discussion

The emergence behavior of most insects exhibits clear circadian rhythms. however, there are notable differences in the eclosion patterns among various insect species. Lepidopteran insects predominantly emerge at night, although some species exhibit emergence peaks during daylight hours. For example, the peak activity period for

Lymantria dispar asiatica Vnukovskij occurs between 7:00 and 10:00 [

17], while

L. xylina exhibits peak activity between 10:00 and 12:00, as well as from 14:00 to 16:00 [

18].

Cydia pomonella peaks at 8:00-11:00 and 9:00-13:00 [

19],

Plutella xylostella exhibits peak activity at 6:00 and 10:00 [

20].

Iragoides fasciata Moore primarily emerges in the afternoon, specifically between 14:00 and 19:00 [

21].

The eclosion rhythm of a single insect species can be influenced by various external factors, with different photoperiod treatments resulting in altered rhythms.For example,

Antheraea pernyi exhibited changes in eclosion rhythm under varying photoperiods, with continuous light treatment showing no distinct periodicity [

22].

P. xylostella subjected to photoperiod reversal lacked a regular emergence pattern [

20], and

Helicoverpa armigera also displayed a reversed rhythm, primarily emerging during the day [

23]. Additionally, plant secondary metabolites can impact insect rhythms; for instance, the methanol extract from indica rice affects serotonin levels in

S. frugiperda, subsequently altering its behavioral and intestinal peristalsis rhythms [

24].

In three strains studied, females emerged earlier than males, consistent with findings in

S. litura [

25] and

S. exigua [

26]. Conversely, in

L. dispar asiatica,

L. xylina,

C. pomonella,

P. xylostella, and

I. fasciata, males emerged before females [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This indicates that there are discernible differences in eclosion rhythms among various Lepidopteran species.

The behavioral rhythms across the three strains varied, yet resting was the predominant behavior observed. During the light period, all strains primarily rested with minimal activity, similar to observations in

S. litura [

25] and

Athetis dissimilis [

27]. Although behavioral rhythms differ among insects, time allocation is primarily aimed at reducing energy expenditure [

28].

Feeding

S. frugiperda different corn cultivars over multiple generations resulted in variations in the ovarian development of newly emerged females. Those fed an artificial diet exhibited greater ovarian weight and length compared to those fed two types of corn leaves. Adult

S. frugiperda that consumed Zhenghuangnuo leaves had significantly higher fat body weight and content than those fed Zhengdan958 and the artificial diet. This suggests that the higher sugar content in Zhenghuangnuo leaves provides more nutrients conducive to fat accumulation during the larval stage. The artificial diet, rich in various nutrients and vitamins, supports ovarian development, leading to superior ovary weight and length compared to the corn leaf strains.

S. frugiperda adults exhibited different behavioral rhythms when feeding on various hosts, particularly in mating behavior, as noted in studies of

S. litura [

25] and

Chilo suppressalis [

29,

30]. Pashley identified differences in the mating rhythms between maize-type and rice-type

S. frugiperda, which showed a preference for mating with their respective types. These findings emphasize that the host plants insects feed on can significantly influence their behavioral rhythms [

31]. Recognizing these differences in behavioral rhythms of pests on various host plants is essential for effective forecasting, prevention, control, and sexual trapping.

Xie discovered that the

HoPer gene in

Holotrichia oblita exhibited high expression levels in the head and antennae, with female adults showing the highest expression in the antennae, while male adults had the highest expression in the head [

32]. In

Bombyx mori, the cry gene was predominantly expressed in the head antennae and flight muscles [

33]. Ji investigated the expression of four circadian clock genes in

Mythimna separata, revealing that these genes were primarily expressed in the antennae and head, with varying expression patterns across different tissues [

34]. The findings of this study indicated distinct expression levels of the four

circadian clock genes in various strains of

S. frugiperda adults across different tissues, predominantly in the antennae and head, aligning with previous results. Unlike Ji's study, which showed similar expression patterns for the same genes in male and female adults of

M. separata, this study found variations in expression patterns between genders, consistent with Xie's findings. In

H. armigera, the

cry1 gene was found to be highly expressed in the abdomen and less so in the antennae, while the

cry2 gene showed high expression in the thorax and low expression in the head [

35]. In

C. suppressalis, the

cry1 gene had high expression in the antennae, and the

cry2 gene was significantly expressed in the abdomen, followed by the head, with lower levels in the leg [

36]. The silkworm exhibited high expression of the

cry1 gene in its head and antennae, while the

cry2 gene was more highly expressed in the head and flight muscle [

33], indicating that the expression patterns of

circadian clock genes vary across species.

Sweet and normal maize were utilized for the continuous rearing of

S. frugiperda over nine generations. The expression levels of circadian clock genes in the two corn cultivars significantly differed from those in the artificial diet strain. The four circadian clock genes displayed a decreasing trend in expression levels within the tissues of the two corn strains compared to the artificial diet strain, whereas the expression levels in male insects of the two strains showed an increasing trend. The expression patterns of the

cry and

cyc genes in the two maize strains were similar to those of the artificial diet strain. After multiple generations of continuous feeding, the expression differences of biological

clock genes between the two maize strains and the artificial diet strain considerably increased compared to the first generation, indicating that prolonged feeding on different hosts amplifies the expression differences of insect biological clock genes. Dres and Mallet have studied that the same herbivorous insect can adapt to various host plants, with differing internal physiology, external morphology, and behavior among host strains potentially leading to reproductive isolation and the formation of distinct host strains within the same region [

37]. Feeding on diverse hosts can also result in changes to insect reproduction-related genes. Yao identified variations in the expression of the vitellogenin gene in

S. frugiperda when feeding on different hosts [

38], and similar differences were noted in

S. litura [

39]. This suggests that herbivorous insects feeding on various host plants can influence the expression of numerous genes, thereby impacting their behavior, reproduction, and other life processes. The results of this study demonstrate that

S. frugiperda feeding on different host plants leads to variations in various behavioral rhythms.Further research has indicated differences in the expression of circadian clock genes among adults of the fall armyworm,

S. frugiperda, from different host strains. This necessitates additional investigation into the mechanisms behind these differences and highlights the importance of considering the influence of different hosts when predicting and implementing comprehensive pest control measures.Also,

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Insects

The initial insects of S. frugiperda were 3 to 5 instar larvae collected from maize fields in Minggang Town, Xinyang, Henan Province in June 2019. These larvae were reared continuously over several generations using an artificial diet in a climate-controlled environment (PQX-280A-3H artificial climate box, Ningbo Laifu Technology Co., Ltd.) maintained at a temperature of (27 ± 1) °C, with a photoperiod of 14 hours light and 10 hours dark, and a relative humidity of (75 ± 5) %. Additionally, two maize strains were reared for 9 generations on fresh corn leaves. Following pupation of the various larval strains, male and female pupae were separated into different containers, while the control group consisted of adults of S. frugiperda raised on the artificial diet in the laboratory.

4.2. Observation of Adult Behavior and Rhythm

The pupae of

S. frugiperda were categorized by gender, and those ready for eclosion were chosen and placed in 50ml insect boxes (dimensions: bottom × upper bottom × height = 28mm × 38mm × 30mm) [

40]. Each box contained two pupae, which were organized neatly, and an infrared camera was used for video recording, with observations made every hour.

The eclosion of the fall armyworm was conducted with a pairing ratio of female to male moths at 1:1, using transparent packaging boxes measuring 10 cm on each side, with one pair per box. A total of 11 treatments were set up, each repeated three times, resulting in 33 pairs. To provide nutrition for the adults, a cotton ball soaked in 10% sucrose water was placed inside each box, and adult behavior was observed and recorded every 20 minutes using the infrared camera.

4.3. Differentiation of Behavioral Characteristics

The activities of adult S. frugiperda were categorized into five distinct types: 1. Movement: adults either crawl or fly within the insect box, with activity lasting over 3 seconds; 2. Nutritional Supplementation: adults feed on sucrose water placed on defatted cotton; 3.Resting: adults remain stationary in the insect box (excluding feeding, mating, and oviposition); 4. Mating: the females and males align their abdomens closely, forming a V-shape or type I configuration; 5. Oviposition: the tip of the adult's abdomen moves as it lays eggs. Additionally, the eclosion and behavioral patterns of S. frugiperda reared for one generation on corn leaves were observed and documented, and these were compared to those of a strain reared for nine generations on the same diet.

4.4. Determination of Ovarian Development

Pupae that exhibited normal appearance and consistent size were chosen and placed into a dipping box. Following eclosion, no nutritional supplementation was provided. At 8:30 a.m. on the second day post-eclosion, females were randomly selected for dissection to assess ovarian development. During dissection, the wings of the female moths were first removed, and scales were collected in a wax plate, secured with an insect needle. Using tweezers, the membrane from the 8th internode of the tail was carefully torn to the midline of the dorsal side, and the body wall was anchored on both sides using an insect needle. The ovary was extracted with a hook needle and weighed on an analytical balance (METTLER TOLEDO, ME204 model), recorded as M0. It was then placed in a wax plate containing 5% pentanediol for observation and photography with a super-depth-of-field microscope (Motic, moticampro). The ovarian duct's length was measured using Image J 1.52a (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, USA,

http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) after dissection and imaging under a binocular stereomicroscope (Shimadzu Kalnew). The fat body was removed and placed into a fresh culture dish. Excess water and free fat body were absorbed with filter paper and weighed, noted as M1. The weight of the fat body was determined by the difference: M0 - M1. Ten individuals were dissected for each treatment, with three repetitions conducted.

4.5. In Vitro Expression of Rhythm-Related Genes

The male and female adults of S.frugiperda after 3 day of eclosion were taken, and the RNA of different parts was extracted at 8 : 00 a.m. to prepare cDNA libraries. For generating the first-strand cDNA, 2µg RNA of female and male S.frugiperda adults was reverse transcribed in a 20μl reaction volume using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa). To confrim single amplicon product for qRT-PCR and bio-specificity for S.frugiperda, gradient PCR was performed for all primer pairs and optimized for a 60˚C annealing temperature for all primer pairs. PCR amplicon products were run on 1.5% 1xTAE agarose gel electrophoresis and Sanger sequenced (Biological Engineering (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.).

qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (Tli RNaseH Plus) (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In the StepOne Plus Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with the following PCR-cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 s, 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s with the concentration at 200 nM of each primer pair. The mean threshold cycle (Ct) was measured by three replicates of each gene, to test sample contamination and dimer formation, nuclease free water as template was included in all qRT-PCR experiments as the negative control. Primer design of four circadian clock genes like Period (Per), Cryptochrome (Cry), Cycle (Cyc), Clock (Clk)] in

S. frugiperda [

41]. The 2-ΔΔ Ct method [

42] was used to calculate individual gene’s relative expression levels. The actin gene (unigene 62750) was chosen as the endogenous reference gene in the qRT-PCR experiment as previously demonstrated. All primers pairs for qRT-PCR are listed in

Table 2.

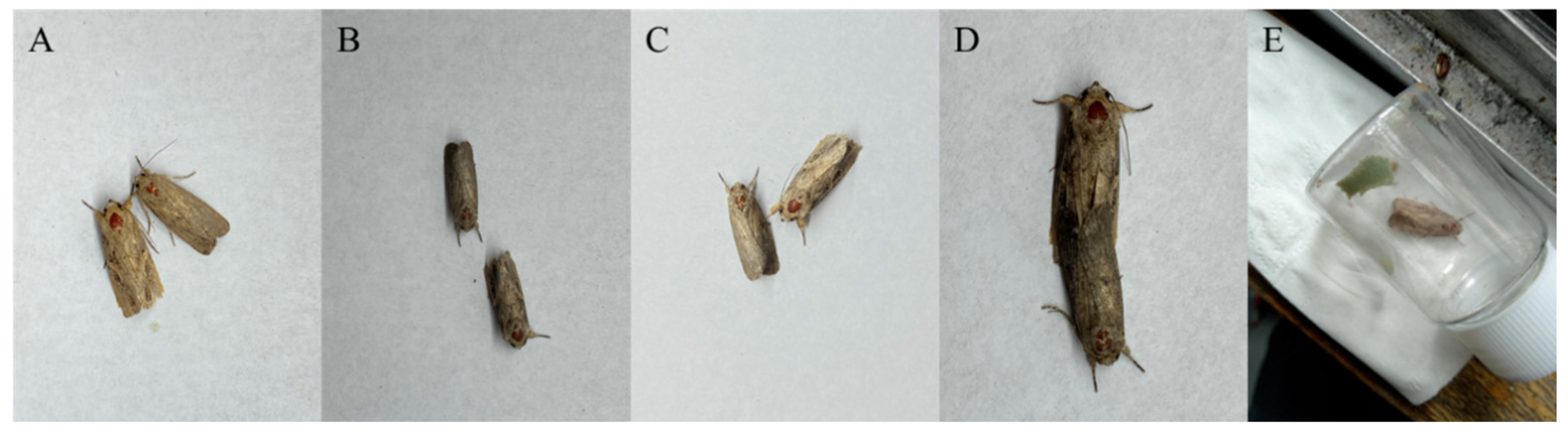

Figure 1.

Behavior of adults of Spodoptera frugiperda. A, B, C, D and E were moving, supplementary nutrition, resting, mating and oviposition behavior, respectively.

Figure 1.

Behavior of adults of Spodoptera frugiperda. A, B, C, D and E were moving, supplementary nutrition, resting, mating and oviposition behavior, respectively.

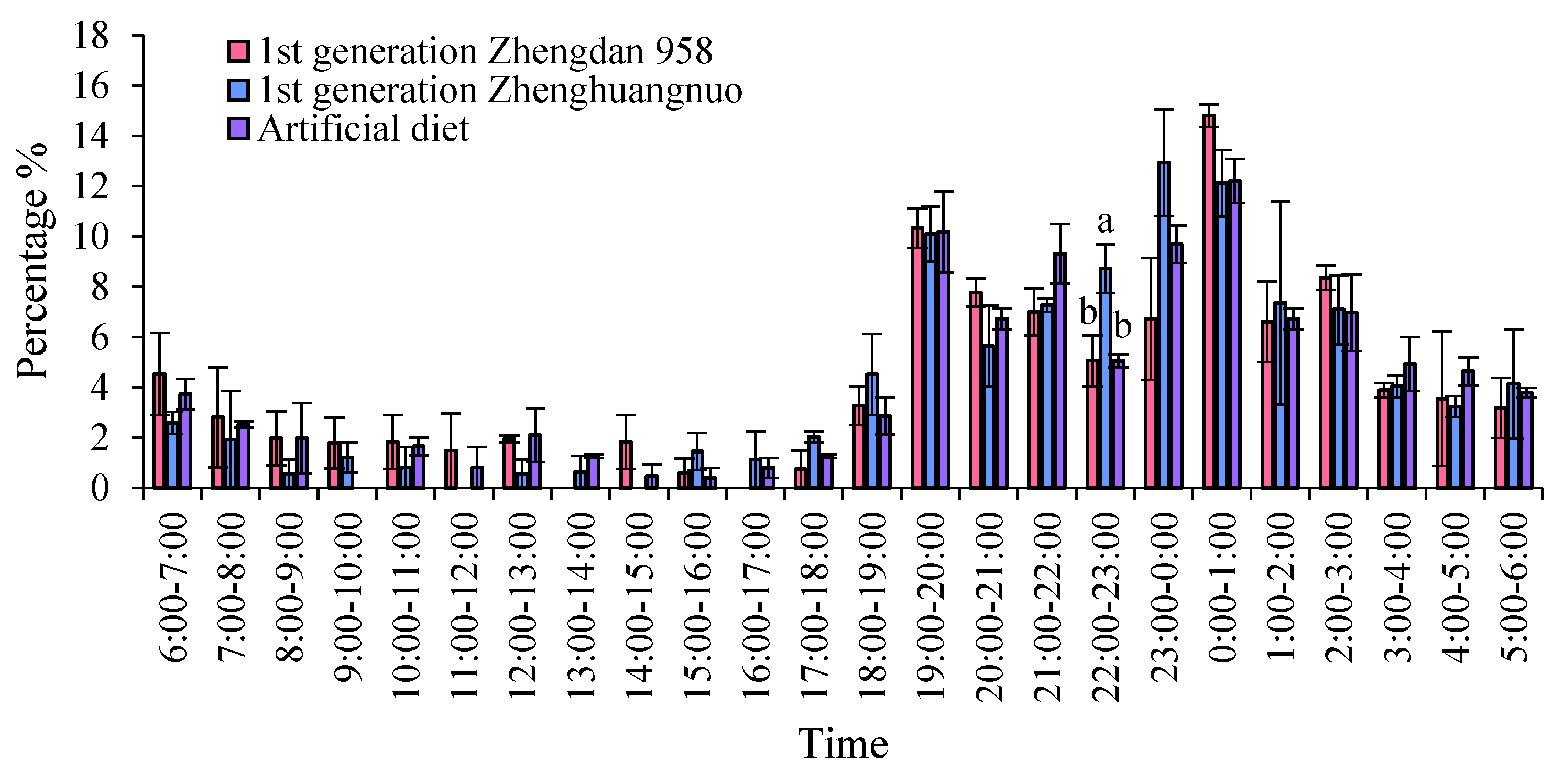

Figure 2.

Adult emergence rhythm of the first generation population of S.frugiperda. Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different capital and lowercase letters above the bars indicate extremely significant(P<0.01) and significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively.

Figure 2.

Adult emergence rhythm of the first generation population of S.frugiperda. Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different capital and lowercase letters above the bars indicate extremely significant(P<0.01) and significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively.

Figure 3.

Rhythms of emergence, movement, resting, mating, and oviposition for different strains of S. frugiperda adults in the first generation. A. Emergence rhythm of the first-generation S. frugiperda strain. B. Movement rhythm of the first-generation S. frugiperda strain. C. Resting rhythm of the first-generation S. frugiperda strains. D. Mating rhythm of different S. frugiperda strains in the first generation. E. Oviposition rhythms of different S. frugiperda strains in the first generation.

Figure 3.

Rhythms of emergence, movement, resting, mating, and oviposition for different strains of S. frugiperda adults in the first generation. A. Emergence rhythm of the first-generation S. frugiperda strain. B. Movement rhythm of the first-generation S. frugiperda strain. C. Resting rhythm of the first-generation S. frugiperda strains. D. Mating rhythm of different S. frugiperda strains in the first generation. E. Oviposition rhythms of different S. frugiperda strains in the first generation.

Figure 4.

Mating duration of adult S. frugiperda in the first-generation population.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different capital and lowercase letters above the bars indicate extremely significant(P<0.01) and significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively.

Figure 4.

Mating duration of adult S. frugiperda in the first-generation population.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different capital and lowercase letters above the bars indicate extremely significant(P<0.01) and significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively.

Figure 5.

Relative levels of circadian clock gene expression in adult individuals of the first generation of the S. frugiperda strain.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively. The expression levels of Per, Clk, Cry, and Cyc in adult females were labeled A to D, whereas in adult males they were indicated by E to H.

Figure 5.

Relative levels of circadian clock gene expression in adult individuals of the first generation of the S. frugiperda strain.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively. The expression levels of Per, Clk, Cry, and Cyc in adult females were labeled A to D, whereas in adult males they were indicated by E to H.

Figure 6.

The adult emergence pattern of S. frugiperda.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively.

Figure 6.

The adult emergence pattern of S. frugiperda.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively.

Figure 7.

The emergence patterns of adult S. frugiperda across various strains. A: Zhengdan 958 strain; B: Zhenghuangnuo strain; C: Artificial diet feed strain.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Lowercase letters above the bars indicated significant differences(P<0.05) in the male and female adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test).

Figure 7.

The emergence patterns of adult S. frugiperda across various strains. A: Zhengdan 958 strain; B: Zhenghuangnuo strain; C: Artificial diet feed strain.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Lowercase letters above the bars indicated significant differences(P<0.05) in the male and female adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test).

Figure 8.

Behavior rhythm of S. frugiperda adults.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively.

Figure 8.

Behavior rhythm of S. frugiperda adults.Data in the figure are mean±SE.Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences(P<0.05) in the different strains of S. frugiperda adults (ANOVA and Duncan’s new multiple range test), respectively.

Figure 9.

Mating duration time of adults S. frugiperda.The lowercase letters in the diagram indicate the significance of differences in mating time within the same strain, while the uppercase letters denote the significance of differences in the percentage of mating time among various strains during the same interval.

Figure 9.

Mating duration time of adults S. frugiperda.The lowercase letters in the diagram indicate the significance of differences in mating time within the same strain, while the uppercase letters denote the significance of differences in the percentage of mating time among various strains during the same interval.

Figure 10.

Time allocation of behavior of S. frugiperda adults.The capital and lowercase letters above the bars indicated the significant difference in the proportion of time allocation of each behavior among the same strain.

Figure 10.

Time allocation of behavior of S. frugiperda adults.The capital and lowercase letters above the bars indicated the significant difference in the proportion of time allocation of each behavior among the same strain.

Figure 11.

Ovaries of S. frugiperda reared on two types of corn leaves and an artificial diet. A: Zhengdan 958 strain; B: Zhenghuangnuo strain; C: Artificial diet feed strain. a: fat body; b: eggs.Bar=1mm.

Figure 11.

Ovaries of S. frugiperda reared on two types of corn leaves and an artificial diet. A: Zhengdan 958 strain; B: Zhenghuangnuo strain; C: Artificial diet feed strain. a: fat body; b: eggs.Bar=1mm.

Figure 12.

Relative expression levels of circadian clock genes in different tissues of S. frugiperda strains.A-C:Relative expression levels of circadian clock genes (clk, cry, and cyc genes) in female adults of artificial diet, Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains, respectively. D~F:Relative gene expression levels of circadian clock genes( clk, cry, and cyc genes) in male adults of artificial diet, Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains, respectively.

Figure 12.

Relative expression levels of circadian clock genes in different tissues of S. frugiperda strains.A-C:Relative expression levels of circadian clock genes (clk, cry, and cyc genes) in female adults of artificial diet, Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains, respectively. D~F:Relative gene expression levels of circadian clock genes( clk, cry, and cyc genes) in male adults of artificial diet, Zhengdan 958 and Zhenghuangnuo strains, respectively.

Figure 13.

Relative expression of circadian clock genes in adults of S. frugiperda strain. The expression levels of Per, Clk, Cry and Cyc in female adults were expressed from A ~ D, and the expression levels of Per, Clk, Cry and Cyc in male adults were expressed from E ~ H.

Figure 13.

Relative expression of circadian clock genes in adults of S. frugiperda strain. The expression levels of Per, Clk, Cry and Cyc in female adults were expressed from A ~ D, and the expression levels of Per, Clk, Cry and Cyc in male adults were expressed from E ~ H.

Table 1.

Effects of different maize cultivars on ovarian development of S. frugiperda.

Table 1.

Effects of different maize cultivars on ovarian development of S. frugiperda.

| Treatment |

Ovary weight (mg) |

Fat body weight (mg) |

Fat body content % |

Ovarian tube length (mm) |

| Zhengdan 958 |

13.80±0.60Bb |

12.20±1.90Aa |

35.22±3.51ABab |

39.95±1.13Aa |

| Zhenghuangnuo |

22.10±2.70Aa |

13.80±1.70Aa |

43.36±3.52Aa |

41.98±0.75Aa |

| Artificial diet |

17.40±2.80Bb |

6.70±1.20Bb |

31.54±3.87Bb |

35.66±1.16Bb |

Table 2.

Circadian clock gene primers information.

Table 2.

Circadian clock gene primers information.

| Primers |

Primer sequences (5’-3’) |

Primer usage |

| Per-F |

ACCACTACAACTGTCGCATCG |

RT-qPCR |

| Per-R |

CACCGCCGGCATAGTGTG |

| Clk-F |

GAGTGCCACCCATTGATCCT |

| Clk-R |

CATCATCAGCGCGTAATCTGG |

| Cry-F |

CGCAATGCTTGGTGGTAGC |

| Cry-R |

CCAACCAGCTTTGTACCTGC |

| Cyc-F |

GGCTCATCGAGTCTCAGGTC |

| Cyc-R |

TGGCTTTTAGTGGCCAGTTCT |

| Actin-F |

TACTCCTAAGCCTGTTGATG |

references |

| Actin-R |

TTATGTCATGGTGCCGAAT |