Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. EEG recording

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. EEG pre-processing

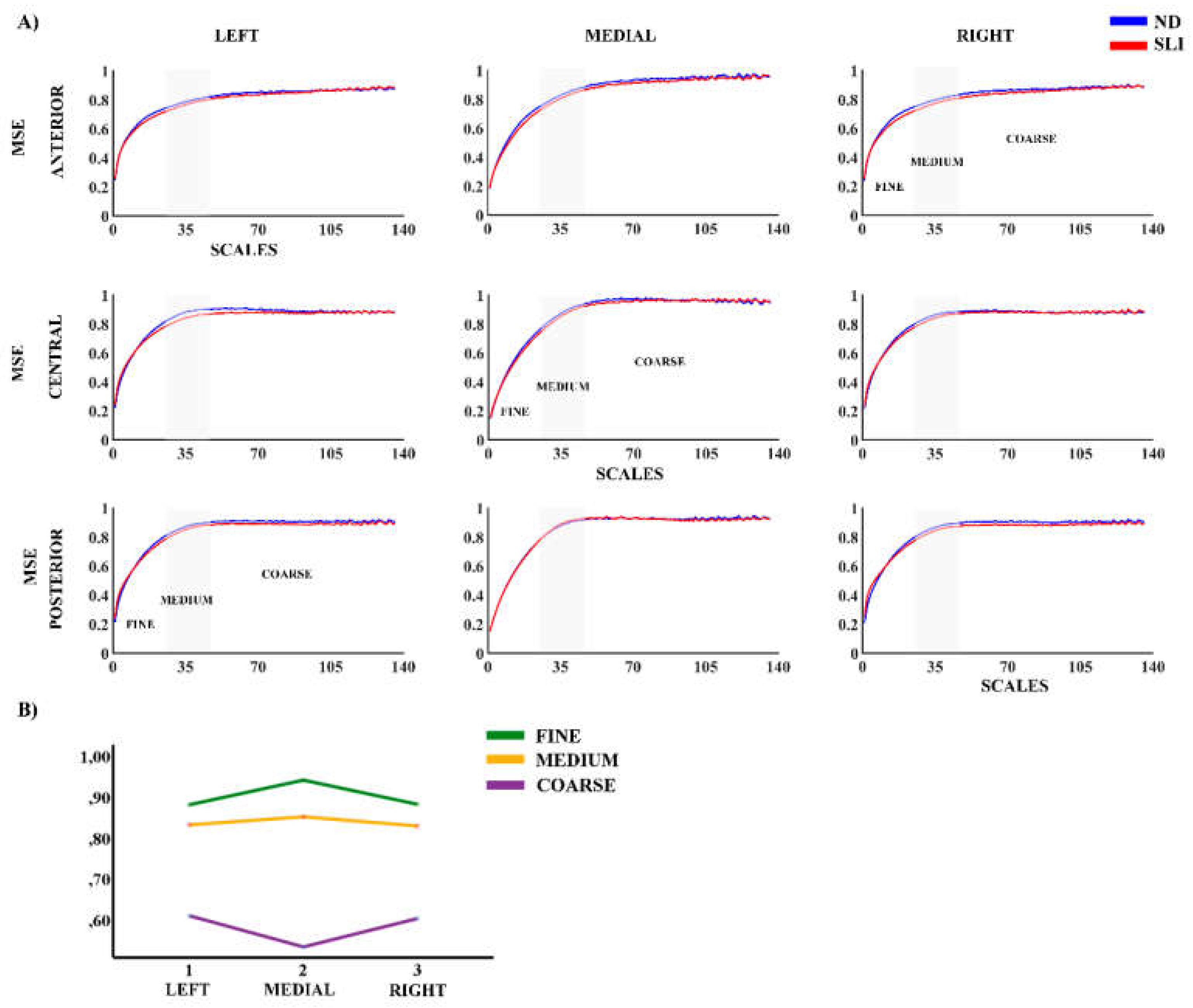

2.3.2. Multiscale Entropy

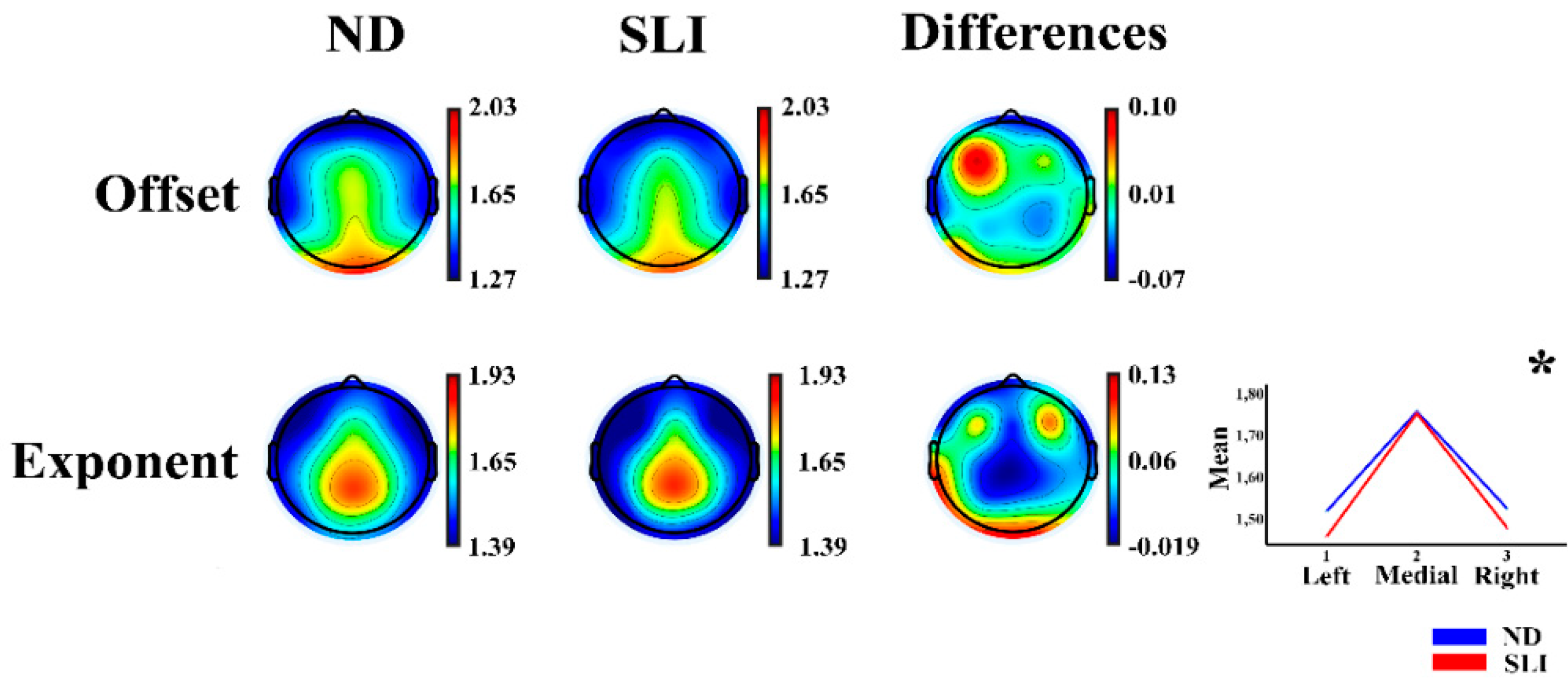

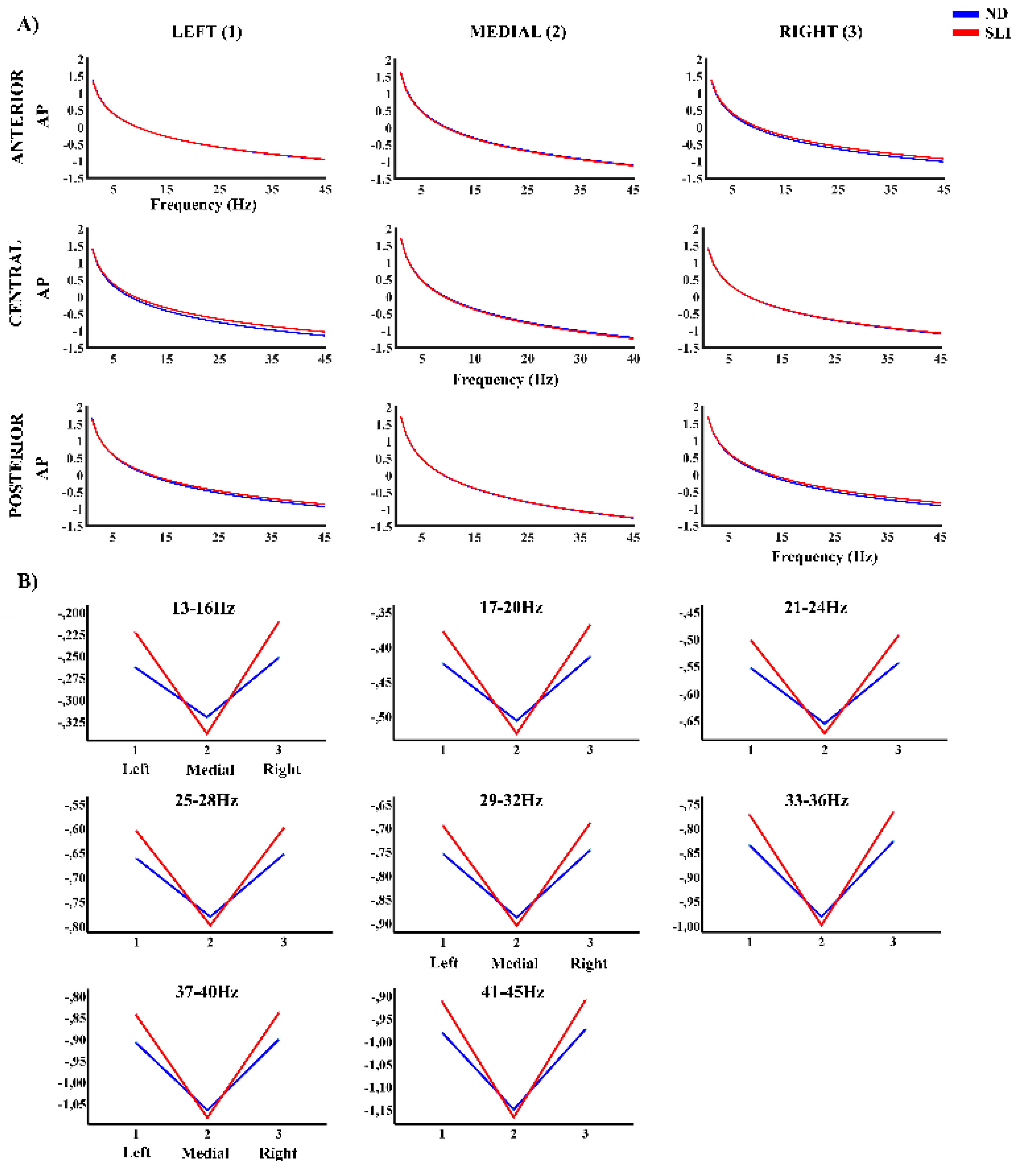

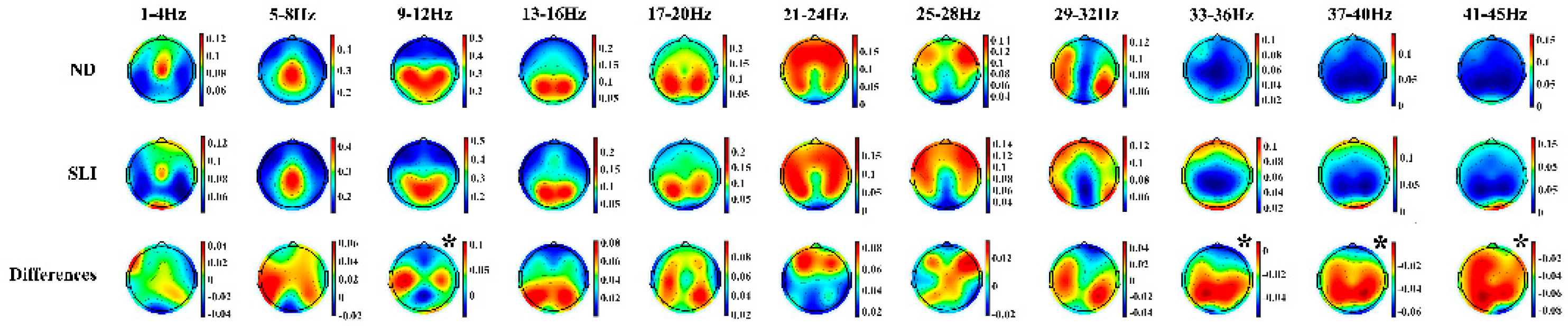

2.3.3. Parameterization of Fitting Oscillations and One-Over-f (FOOOF)

2.4. Statistical analysis

2.4.1. Multiscale Entropy

Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (RM-ANOVA)

2.4.2. Parametrization of Fitting Oscillations and One-Over-f (FOOOF)

Topographical Analysis

Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (RM-ANOVA)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| AP | Aperiodic |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| ASR | Artifact Subsapace Reconstruction |

| CELF | Clinical Evaluation of Langage Fundamentals |

| DTI | Diffusion Tensor Imaging |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| ERPs | Event-related Potentials |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| fMRI | functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| FOOOF | Fitting Oscillations and One-Over-f |

| fTCD | functional Transcranial Doppler |

| ICA | Independent Component Analysis |

| ITPA | Illinios Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities |

| KBIT | Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test |

| M | Mean |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MMN | Mismatch Negativity |

| MSE | Multiscale Entropy |

| ND | Normo-development |

| P | Periodic |

| PLON-R | Navarre Oral Language Test-Revised |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| PPVT-5 | Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test |

| RM-ANOVA | Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Sample Entropy |

| SLI | Specific Language Impairment |

| SPECT | Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| UDIATE | Unidad de Desarrollo Infantil y Atención Temprana |

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostics and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, IV text revision.

- American Psychiatric Association (2012): DSM-V Development. Disponible en: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=488.

- Villegas, L.F. (2022). Specific language impairment in Andalusia, Spain: Prevelance by subtype and gender. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología. 42(3), 147-157. [CrossRef]

- Bishop D. V. (2002). The role of genes in the etiology of specific language impairment. Journal of communication disorders, 35(4), 311–328. [CrossRef]

- Bishop D. V. (2009). Genes, cognition, and communication: insights from neurodevelopmental disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1156(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Bishop D. V. (2013). Cerebral asymmetry and language development: cause, correlate, or consequence?. Science (New York, N.Y.), 340(6138), 1230531. [CrossRef]

- Li, N., & Bartlett, C. W. (2012). Defining the genetic architecture of human developmental language impairment. Life sciences, 90(13-14), 469–475. [CrossRef]

- Tomblin, J. B., Records, N. L., Buckwalter, P., Zhang, X., Smith, E., & O’Brien, M. (1997). Prevalence of specific language impairment in kindergarten children. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research: JSLHR, 40(6), 1245–1260. [CrossRef]

- Pennington, B. F., & Bishop, D. V. (2009). Relations among speech, language, and reading disorders. Annual review of psychology, 60, 283–306. [CrossRef]

- Young, A. R., Beitchman, J. H., Johnson, C., Douglas, L., Atkinson, L., Escobar, M., & Wilson, B. (2002). Young adult academic outcomes in a longitudinal sample of early identified language impaired and control children. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 43(5), 635–645. [CrossRef]

- Wadman, R., Botting, N., Durkin, K., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2011a). Changes in emotional health symptoms in adolescents with specific language impairment. International journal of language & communication disorders, 46(6), 641–656. [CrossRef]

- Wadman, R., Durkin, K., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2011b). Close relationships in adolescents with and without a history of specific language impairment. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 42(1), 41–51. [CrossRef]

- Wadman, R., Durkin, K., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2011c). Social stress in young people with specific language impairment. Journal of adolescence, 34(3), 421–431. [CrossRef]

- Arkkila, E., Rasanen, P., Roine, R. P., & Vilkman, E. (2008). Specific language impairment in childhood is associated with impaired mental and social well-being in adulthood. Logopedics, phoniatrics, vocology, 33(4), 179–189. [CrossRef]

- Tallal, P. (2004). Improving language and literacy is a matter of time. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 5(9), 721–728. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H. J., Tomblin, J. B., & Christiansen, M. H. (2014). Impaired statistical learning of non-adjacent dependencies in adolescents with specific language impairment. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 175. [CrossRef]

- Goswami, U. (2019). Speech rhythm and language acquisition: an amplitude modulation phase hierarchy perspective. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1453(1), 67–78. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, N., & Love, T. (2023). Bridging the Divide: Brain and Behavior in Developmental Language Disorder. Brain sciences, 13(11), 1606. [CrossRef]

- Gauger, L. M., Lombardino, L. J., & Leonard, C. M. (1997). Brain morphology in children with specific language impairment. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR, 40(6), 1272–1284. [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M. R., Ziegler, D. A., Makris, N., Filipek, P. A., Kemper, T. L., Normandin, J. J., Sanders, H. A., Kennedy, D. N., & Caviness, V. S., Jr (2004). Localization of white matter volume increase in autism and developmental language disorder. Annals of neurology, 55(4), 530–540. [CrossRef]

- Bahar, N., Cler, G. J., Krishnan, S., Asaridou, S. S., Smith, H. J., Willis, H. E., Healy, M. P., & Watkins, K. E. (2024). Differences in Cortical Surface Area in Developmental Language Disorder. Neurobiology of language (Cambridge, Mass.), 5(2), 288–314. [CrossRef]

- Badcock, N. A., Bishop, D. V., Hardiman, M. J., Barry, J. G., & Watkins, K. E. (2012). Co-localisation of abnormal brain structure and function in specific language impairment. Brain and language, 120(3), 310–320. [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Mas, C., Pujol, J., Ortiz, H., Deus, J., López-Sala, A., & Sans, A. (2009). Age-related brain structural alterations in children with specific language impairment. Human brain mapping, 30(5), 1626–1636. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. C., Nopoulos, P. C., & Bruce Tomblin, J. (2013). Abnormal subcortical components of the corticostriatal system in young adults with DLI: a combined structural MRI and DTI study. Neuropsychologia, 51(11), 2154–2161. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S., Cler, G. J., Smith, H. J., Willis, H. E., Asaridou, S. S., Healy, M. P., Papp, D., & Watkins, K. E. (2022). Quantitative MRI reveals differences in striatal myelin in children with DLD. eLife, 11, e74242. [CrossRef]

- Hugdahl, K., Gundersen, H., Brekke, C., Thomsen, T., Rimol, L. M., Ersland, L., & Niemi, J. (2004). FMRI brain activation in a finnish family with specific language impairment compared with a normal control group. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research: JSLHR, 47(1), 162–172. [CrossRef]

- de Guibert, C., Maumet, C., Jannin, P., Ferré, J.C., Tréguier, C., Barillot, C., Le Rumeur, E., Allaire, C., Biraben, A. (2011). Abnormal functional lateralization and activity of language brain areas in typical specific language impairment (developmental dysphasia). Brain. Oct;134(Pt 10):3044-58. [CrossRef]

- Ors, M., Ryding, E., Lindgren, M., Gustafsson, P., Blennow, G., & Rosén, I. (2005). SPECT findings in children with specific language impairment. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior, 41(3), 316–326. [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, A. J., & Bishop, D. V. (2008). Cerebral dominance for language function in adults with specific language impairment or autism. Brain: a journal of neurology, 131(Pt 12), 3193–3200. [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M.R., Ziegler, D.A., Makris, N., Bakardjiev, A., Hodgson, J., Adrien, K.T., Kennedy, D.N., Filipek, P.A. & Caviness, V.S., Jr. (2003). Largerbrain and white matter volumes in children with developmental language disorder. Developmental Science, 6(4), F11-F22. [CrossRef]

- Vydrova, R., Komarek, V., Sanda, J., Sterbova, K., Jahodova, A., Maulisova, A., Zackova, J., Reissigova, J., Krsek, P., & Kyncl, M. (2015). Structural alterations of the language connectome in children with specific language impairment. Brain and language, 151, 35–41. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T. P., Heiken, K., Zarnow, D., Dell, J., Nagae, L., Blaskey, L., Solot, C., Levy, S. E., Berman, J. I., & Edgar, J. C. (2014). Left hemisphere diffusivity of the arcuate fasciculus: influences of autism spectrum disorder and language impairment. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology, 35(3), 587–592. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. C., Dick, A. S., & Tomblin, J. B. (2020). Altered brain structures in the dorsal and ventral language pathways in individuals with and without developmental language disorder (DLD). Brain imaging and behavior, 14(6), 2569–2586. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. V., & McArthur, G. M. (2005). Individual differences in auditory processing in specific language impairment: a follow-up study using event-related potentials and behavioural thresholds. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior, 41(3), 327–341. [CrossRef]

- Shafer, V. L., Morr, M. L., Datta, H., Kurtzberg, D., & Schwartz, R. G. (2005). Neurophysiological indexes of speech processing deficits in children with specific language impairment. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 17(7), 1168–1180. [CrossRef]

- Datta, H., Shafer, V. L., Morr, M. L., Kurtzberg, D., & Schwartz, R. G. (2010). Electrophysiological indices of discrimination of long-duration, phonetically similar vowels in children with typical and atypical language development. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research: JSLHR, 53(3), 757–777. [CrossRef]

- Kujala, T., & Leminen, M. (2017). Low-level neural auditory discrimination dysfunctions in specific language impairment-A review on mismatch negativity findings. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 28, 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Sabisch, B., Hahne, A., Glass, E., von Suchodoletz, W., Friederici, A.D. (2006). Lexical–semantic processes in children with specific language impairment. NeuroReport 17(14), 1511-1514. [CrossRef]

- Haebig, E., Leonard, L., Usler, E., Deevy, P., & Weber, C. (2018). An Initial Investigation of the Neural Correlates of Word Processing in Preschoolers With Specific Language Impairment. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research: JSLHR, 61(3), 729–739. [CrossRef]

- Shafer, V. L., Ponton, C., Datta, H., Morr, M. L., & Schwartz, R. G. (2007). Neurophysiological indices of attention to speech in children with specific language impairment. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 118(6), 1230–1243. [CrossRef]

- Shafer, V. L., Schwartz, R. G., & Martin, B. (2011). Evidence of deficient central speech processing in children with specific language impairment: the T-complex. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 122(6), 1137–1155. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, R., Suchodoletz, W., & Uwer, R. (2000). The development of auditory evoked dipole source activity from childhood to adulthood. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 111(12), 2268–2276. [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, E. A., Shohdy, S. S., Abd Al Raouf, M., Mohamed El Abd, S., & Abd Elhamid, A. (2011). Relation between language, audio-vocal psycholinguistic abilities and P300 in children having specific language impairment. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology, 75(9), 1117–1122. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. L., Selinger, C., & Pollak, S. D. (2011). P300 as a measure of processing capacity in auditory and visual domains in specific language impairment. Brain research, 1389, 93–102. [CrossRef]

- Gasser, T., Verleger, R., Bächer, P. and Sroka, L. (1988). Development of the EEG of school-age children and adolescents. I. Analysis of band power. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology, 69(2), 91–99. [CrossRef]

- Whitford, T. J., Rennie, C. J., Grieve, S. M., Clark, C. R., Gordon, E., and Williams, L. M. (2007). Brain maturation in adolescence: concurrent changes in neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. Human brain mapping, 28(3), 228–237. [CrossRef]

- Segalowitz, S. J., Santesso, D. L., & Jetha, M. K. (2010). Electrophysiological changes during adolescence: a review. Brain and cognition, 72(1), 86–100. [CrossRef]

- Miskovic, V., Ma, X., Chou, C. A., Fan, M., Owens, M., Sayama, H., & Gibb, B. E. (2015). Developmental changes in spontaneous electrocortical activity and network organization from early to late childhood. NeuroImage, 118, 237–247. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, E. I., Ruiz-Martínez, F. J., Barriga Paulino, C. I., & Gómez, C. M. (2017). Frequency shift in topography of spontaneous brain rhythms from childhood to adulthood. Cognitive neurodynamics, 11(1), 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, E. I., Angulo-Ruiz, B. Y., Arjona-Valladares, A., Rufo, M., Gómez-González, J., & Gómez, C. M. (2020). Frequency coupling of low and high frequencies in the EEG of ADHD children and adolescents in closed and open eyes conditions. Research in developmental disabilities, 96, 103520. [CrossRef]

- Lea-Carnall, C. A., Montemurro, M. A., Trujillo-Barreto, N. J., Parkes, L. M., & El-Deredy, W. (2016). Cortical Resonance Frequencies Emerge from Network Size and Connectivity. PLoS computational biology, 12(2), e1004740. [CrossRef]

- Szostakiwskyj, J. M. H., Willatt, S. E., Cortese, F., & Protzner, A. B. (2017). The modulation of EEG variability between internally- and externally-driven cognitive states varies with maturation and task performance. PloS one, 12(7), e0181894. [CrossRef]

- Barry, R. J., Clarke, A. R., Johnstone, S. J., McCarthy, R., & Selikowitz, M. (2009). Electroencephalogram theta/beta ratio and arousal in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence of independent processes. Biological psychiatry, 66(4), 398–401. [CrossRef]

- Newson, J. J., & Thiagarajan, T. C. (2019). EEG Frequency Bands in Psychiatric Disorders: A Review of Resting State Studies. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 12, 521. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. R., Barry, R. J., & Johnstone, S. (2020). Resting state EEG power research in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A review update. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 131(7), 1463–1479. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G., Klinger, L. G., Panagiotides, H., Lewy, A., & Castelloe, P. (1995). Subgroups of autistic children based on social behavior display distinct patterns of brain activity. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 23(5), 569–583. [CrossRef]

- Daoust, A. M., Limoges, E., Bolduc, C., Mottron, L., & Godbout, R. (2004). EEG spectral analysis of wakefulness and REM sleep in high functioning autistic spectrum disorders. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 115(6), 1368–1373. [CrossRef]

- Chan, A. S., Sze, S. L., & Cheung, M. C. (2007). Quantitative electroencephalographic profiles for children with autistic spectrum disorder. Neuropsychology, 21(1), 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Pop-Jordanova, N., Zorcec, T., Demerdzieva, A., & Gucev, Z. (2010). QEEG characteristics and spectrum weighted frequency for children diagnosed as autistic spectrum disorder. Nonlinear biomedical physics, 4(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Barstein, J., Ethridge, L. E., Mosconi, M. W., Takarae, Y., & Sweeney, J. A. (2013). Resting state EEG abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders, 5(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H., Kim, I., Lee, W., Peterson, B. S., Hong, H., Chae, J. H., Hong, S., & Jeong, J. (2010). Linear and non-linear EEG analysis of adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder during a cognitive task. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 121(11), 1863–1870. [CrossRef]

- Sokunbi, M. O., Fung, W., Sawlani, V., Choppin, S., Linden, D. E., & Thome, J. (2013). Resting state fMRI entropy probes complexity of brain activity in adults with ADHD. Psychiatry research, 214(3), 341–348. [CrossRef]

- Rezaeezadeh, M., Shamekhi, S., & Shamsi, M. (2020). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Diagnosis using non-linear univariate and multivariate EEG measurements: a preliminary study. Physical and engineering sciences in medicine, 43(2), 577–592. [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Ruiz, B. Y., Muñoz, V., Rodríguez-Martínez, E. I., Cabello-Navarro, C., & Gómez, C. M. (2022). Multiscale entropy of ADHD children during resting state condition. Cognitive neurodynamics, 17(4), 869–891. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y. J., Chang, C. F., Shieh, J. S., & Lee, W. T. (2017). The Potential Application of Multiscale Entropy Analysis of Electroencephalography in Children with Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Entropy (Basel, Switzerland), 19(8), 428. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Chen, Y., Chen, D., Li, C., Qiu, Y., & Wang, J. (2017). Altered electroencephalogram complexity in autistic children shown by the multiscale entropy approach. Neuroreport, 28(3), 169–173. [CrossRef]

- Milne, E., Gomez, R., Giannadou, A., & Jones, M. (2019). Atypical EEG in autism spectrum disorder: Comparing a dimensional and a categorical approach. Journal of abnormal psychology, 128(5), 442–452. [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Ruiz, B.Y., Ruiz-Martínez, F.J., Rodríguez-Martínez, E.I. et al. (2023) Linear and Non-linear Analyses of EEG in a Group of ASD Children During Resting State Condition. Brain Topogr 36, 736–749. [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, C., Dickinson, A., Baker, E., & Jeste, S. S. (2019). EEG Data Collection in Children with ASD: The Role of State in Data Quality and Spectral Power. Research in autism spectrum disorders, 57, 132–144. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, S., Kadlaskar, G., Edmondson, D. A., McNally Keehn, R., Dydak, U., & Keehn, B. (2021). Associations between sensory processing and electrophysiological and neurochemical measures in children with ASD: an EEG-MRS study. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders, 13(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T., Yoshimura, Y., Hiraishi, H., Hasegawa, C., Munesue, T., Higashida, H., Minabe, Y., & Kikuchi, M. (2016). Enhanced brain signal variability in children with autism spectrum disorder during early childhood. Human brain mapping, 37(3), 1038–1050. [CrossRef]

- Bosl, W.J., Loddenkemper, T., Nelson, C.A. (2017) Nonlinear EEG biomarker profiles for autism and absence epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Electrophysiol 3:1. [CrossRef]

- Nenadović, V., Stokić, M., Vuković, M., Đoković, S., & Subotić, M. (2014). Cognitive and electrophysiological characteristics of children with specific language impairment and subclinical epileptiform electroencephalogram. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 36(9), 981–991. [CrossRef]

- Chutko, L.S., Surushkina, S.Y., Yakovenko, E.A., Sergeev, A.V., Rozhkova, A.V., Anosova, L.V., Chistyakova, N.P. (2015). Clinical and electroencephalographic characteristics of specific language impairment in children and an evaluation of the efficacy of cerebrolysin. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 115(7): 98-102. [CrossRef]

- Fatić, S., Stanojević, N., Stokić, M., Nenadović, V., Jeličić, L., Bilibajkić, R., Gavrilović, A., Maksimović, S., Adamović, T., & Subotić, M. (2022). Electroencephalography correlates of word and non-word listening in children with specific language impairment: An observational study20F0. Medicine, 101(46), e31840. [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, N., Fatic, S., Jelicic, L., Nenadovic, V., Stokic, M., Bilibajkic, R., Subotic, M., Boskovic Matic, T., Konstantinovic, L., & Cirovic, D. (2023). Resting-state EEG alpha rhythm spectral power in children with specific language impairment: a cross-sectional study. Journal of applied biomedicine, 21(3), 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, T., Haller, M., Peterson, E. J., Varma, P., Sebastian, P., Gao, R., Noto, T., Lara, A. H., Wallis, J. D., Knight, R. T., Shestyuk, A., & Voytek, B. (2020). Parameterizing neural power spectra into periodic and aperiodic components. Nature neuroscience, 23(12), 1655–1665. [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, M., Morales, S., Valadez, E. A., Buzzell, G. A., Yoder, L., Fifer, W. P., Pini, N., Shuffrey, L. C., Elliott, A. J., Isler, J. R., & Fox, N. A. (2023). Age-related trends in aperiodic EEG activity and alpha oscillations during early- to middle-childhood. NeuroImage, 269, 119925. [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G., Anastassiou, C. A., & Koch, C. (2012). The origin of extracellular fields and currents--EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 13(6), 407–420. [CrossRef]

- Gao, R., Peterson, E. J., and Voytek, B. (2017). Inferring synaptic excitation/inhibition balance from field potentials. NeuroImage, 158, 70–78. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M. M., Furlong, S., Voytek, B., Donoghue, T., Boettiger, C. A., & Sheridan, M. A. (2019). EEG power spectral slope differs by ADHD status and stimulant medication exposure in early childhood. Journal of neurophysiology, 122(6), 2427–2437. 6. [CrossRef]

- Pertermann, M., Bluschke, A., Roessner, V., & Beste, C. (2019). The Modulation of Neural Noise Underlies the Effectiveness of Methylphenidate Treatment in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biological psychiatry. Cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging, 4(8), 743–750. [CrossRef]

- Mamiya, P. C., Arnett, A. B., & Stein, M. A. (2021). Precision Medicine Care in ADHD: The Case for Neural Excitation and Inhibition. Brain sciences, 11(1), 91. [CrossRef]

- Ostlund, B. D., Alperin, B. R., Drew, T., & Karalunas, S. L. (2021). Behavioral and cognitive correlates of the aperiodic (1/f-like) exponent of the EEG power spectrum in adolescents with and without ADHD. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 48, 100931. [CrossRef]

- Levin, A. R., Naples, A. J., Scheffler, A. W., Webb, S. J., Shic, F., Sugar, C. A., Murias, M., Bernier, R. A., Chawarska, K., Dawson, G., Faja, S., Jeste, S., Nelson, C. A., McPartland, J. C., & Şentürk, D. (2020). Day-to-Day Test-Retest Reliability of EEG Profiles in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typical Development. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 14, 21. [CrossRef]

- Wiig E. H., Semel E., Secord W. A. (2013). Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fifth Edition (CELF-5). Bloomington, MN: NCS Pearson.

- Aguinaga Ayerra, G. (2005). PLON-R:prueba de lenguaje oral navarra revisada (2a ed.). TEA.

- Kirk, S. A., & McCarthy, J. J. (1961). The Illinois test of psycholinguistic abilities--an approach to differential diagnosis. American journal of mental deficiency, 66, 399–412.

- Dunn, L. M. (1959). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. American Guidance Service.

- Kaufman, A.S. & Kaufman, N.L. (2004) KBIT: Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT Spanish Version). ASD Editions, Madrid.

- Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. (2004). EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of neuroscience methods, 134(1), 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Mullen, T. R., Kothe, C. A., Chi, Y. M., Ojeda, A., Kerth, T., Makeig, S., Jung, T. P., & Cauwenberghs, G. (2015). Real-Time Neuroimaging and Cognitive Monitoring Using Wearable Dry EEG. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering, 62(11), 2553–2567. [CrossRef]

- Bell, A. J. & Sejnowski, T. J. (1995). An information-maximization approach to blind separation and blind deconvolution. Neural computation, 7(6), 1129–1159. [CrossRef]

- Amari, S., Cichocki, A., and Yang, H.H. (1995). A New Learning Algorithm for Blind Signal Separation. NIPS.

- Pion-Tonachini, L., Kreutz-Delgado, K., & Makeig, S. (2019). ICLabel: An automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. NeuroImage, 198, 181–197. [CrossRef]

- Malik, J. (2022). Multiscale sample entropy. https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/62706-multiscale-sample-entropy, MATLAB Central File Exchange.

- Costa, M., Goldberger, A.L. & Peng, C.K. (2005) Multiscale entropy analysis of biological signals. Phys Rev Lett 71(021906):753. [CrossRef]

- Richman, J. S., & Moorman, J. R. (2000). Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology, 278(6), H2039–H2049. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A. R., Kovacevic, N., & Itier, R. J. (2008). Increased brain signal variability accompanies lower behavioral variability in development. PLoS computational biology, 4(7), e1000106. [CrossRef]

- Miskovic, V., Owens, M., Kuntzelman, K., & Gibb, B. E. (2016). Charting moment-to-moment brain signal variability from early to late childhood. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior, 83, 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Kloosterman, N.A., Kosciessa, J.Q., Lindenberger, U., Fahrenfort, J.J., Garrett, D.D. (2019). Boosting brain signal variability underlies liberal shifts in decision bias. Biorxiv. [CrossRef]

- Kosciessa, J. Q., Kloosterman, N. A., & Garrett, D. D. (2020). Standard multiscale entropy reflects neural dynamics at mismatched temporal scales: What’s signal irregularity got to do with it?. PLoS computational biology, 16(5), e1007885. [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, A. G., Kalantzi, E., Papageorgiou, C. C., Korombili, K., Βokou, A., Pehlivanidis, A., Papageorgiou, C. C., & Papaioannou, G. (2021). Complexity analysis of the brain activity in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) due to cognitive loads/demands induced by Aristotle’s type of syllogism/reasoning. A Power Spectral Density and multiscale entropy (MSE) analysis. Heliyon, 7(9), e07984. [CrossRef]

- Garrett, D. D., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., MacDonald, S. W., Lindenberger, U., McIntosh, A. R., & Grady, C. L. (2013). Moment-to-moment brain signal variability: a next frontier in human brain mapping?. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 37(4), 610–624. [CrossRef]

- Bosl, W.J., Loddenkemper, T., Vieluf, S. (2022). Coarse-graining and the Haar wavelet transform for multiscale analysis. Biolectronic Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Ruiz, B. Y., Rodríguez-Martínez, E. I., Muñoz, V., & Gómez, C. M. (2024). Unveiling the hidden electroencephalographical rhythms during development: Aperiodic and Periodic activity in healthy subjects. Clinical neurophysiology: official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology, 169, 53–64. [CrossRef]

- Ostlund, B., Donoghue, T., Anaya, B., Gunther, K. E., Karalunas, S. L., Voytek, B., and Pérez-Edgar, K. E. (2022). Spectral parameterization for studying neurodevelopment: How and why. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 54, 101073. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn.

- Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc 57(1):289–300. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.S., Roach, B.J., Sargent, K., Mathalon, D.H., & Ford, J.M. (2021), Aperiodic measures of neural excitability are associated with anticorrelated hemodynamic networks at rest: a combined EEG-fMRI study. [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. T., Clark, G. M., Bigelow, F. J., Lum, J. A. G., & Enticott, P. G. (2022). Periodic and aperiodic neural activity displays age-dependent changes across early-to-middle childhood. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 54, 101076. [CrossRef]

- Manning, J. R., Jacobs, J., Fried, I., & Kahana, M. J. (2009). Broadband shifts in local field potential power spectra are correlated with single-neuron spiking in humans. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 29(43), 13613–13620. [CrossRef]

- Miller, K. J., Honey, C. J., Hermes, D., Rao, R. P., denNijs, M., & Ojemann, J. G. (2014). Broadband changes in the cortical surface potential track activation of functionally diverse neuronal populations. NeuroImage, 85 Pt 2(0 2), 711–720. [CrossRef]

- Voytek, B. & Knight, R. T. (2015). Dynamic network communication as a unifying neural basis for cognition, development, aging, and disease. Biological psychiatry, 77(12), 1089–1097. [CrossRef]

- Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., & Schacter, D. L. (2008). The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Proal, E., Alvarez-Segura, M., de la Iglesia-Vayá, M., Martí-Bonmatí, L., Castellanos, F. X., & Spanish Resting State Network (2011). Actividad funcional cerebral en estado de reposo: redes en conexion [Functional cerebral activity in a state of rest: connectivity networks]. Revista de neurologia, 52 Suppl 1(0 1), S3–S10.

- Wilke, M., Hauser, T. K., Krägeloh-Mann, I., & Lidzba, K. (2014). Specific impairment of functional connectivity between language regions in former early preterms. Human brain mapping, 35(7), 3372–3384. [CrossRef]

- Barnes-Davis, M. E., Williamson, B. J., Merhar, S. L., Holland, S. K., & Kadis, D. S. (2020). Rewiring the extremely preterm brain: Altered structural connectivity relates to language function. NeuroImage. Clinical, 25, 102194. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A. C., Feng, W., Zhao, H., Yin, Y., & Wang, P. (2008). EEG default mode network in the human brain: spectral regional field powers. NeuroImage, 41(2), 561–574. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, C. M., Marco-Pallarés, J., & Grau, C. (2006). Location of brain rhythms and their modulation by preparatory attention estimated by current density. Brain research, 1107(1), 151–160. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martinez, E. I., Barriga-Paulino, C. I., Zapata, M. I., Chinchilla, C., López-Jiménez, A. M., & Gómez, C. M. (2012). Narrow band quantitative and multivariate electroencephalogram analysis of peri-adolescent period. BMC neuroscience, 13, 104. [CrossRef]

- Finneran, D. A., Francis, A. L., & Leonard, L. B. (2009). Sustained attention in children with specific language impairment (SLI). Journal of speech, language, and hearing research: JSLHR, 52(4), 915–929. [CrossRef]

- Verche, B. E., Hernández, E.S., Quintero, F.I. & Acosta, R.V.M. (2013). Alteraciones en la memoria en el Trastorno Específico del Lenguaje. Una perspectiva neuropsicológica. Revista de Logopedia, foniatría y audiología. 33, 4, 179-185. [CrossRef]

- Quintero, I., Hernández, S., Verche, E., Acosta, V. & Hernández, A. (2013). Disfunción ejecutiva en el Trastorno Específico del Lenguaje. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología. 33, 4, 172-178. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A., Ramírez, S.G.M. & Expósito, H. (2017). Funciones ejecutivas y lenguaje en subtipos de niños con trastorno específico del lenguaje. Neurología. 32(6), 355-362. [CrossRef]

- Bosman, C. A., Lansink, C. S., & Pennartz, C. M. (2014). Functions of gamma-band synchronization in cognition: from single circuits to functional diversity across cortical and subcortical systems. The European journal of neuroscience, 39(11), 1982–1999. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. P., & Robbins, T. W. (2022). The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(1), 72–89. [CrossRef]

- Mazza, A., Dal Monte, O., Schintu, S., Colombo, S., Michielli, N., Sarasso, P., Törlind, P., Cantamessa, M., Montagna, F., & Ricci, R. (2023). Beyond alpha-band: The neural correlate of creative thinking. Neuropsychologia, 179, 108446. [CrossRef]

- Hindriks, R., van Putten, M. J. A. M., & Deco, G. (2014). Intra-cortical propagation of EEG alpha oscillations. NeuroImage, 103, 444–453. [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W. (2012). α-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends in cognitive sciences, 16(12), 606–617. [CrossRef]

- London, R. E., Benwell, C. S. Y., Cecere, R., Quak, M., Thut, G., & Talsma, D. (2022). EEG alpha power predicts the temporal sensitivity of multisensory perception. The European journal of neuroscience, 55(11-12), 3241–3255. [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Within-subjects |

|---|---|

| 13-16Hz | Laterality x group p=.034 F(1.89,114.96)=3.58, np2=.055, power=.636 |

| 17-20Hz | Laterality x group p=.025 F(1.88,114.93)=4.52, np2=.060, power=.676 |

| 21-24Hz | Laterality x group p=.021 F(1.89,115.11)=4.12, np2=.063, power=.701 |

| 25-28Hz | Laterality x group p=.018 F(1.89,115.36)=4.27, np2=.065, power=.719 |

| 29-32Hz | Laterality x group p=.016 F(1.89,115.63)=4.38, np2=.067, power=.731 |

| 33-36Hz | Laterality x group p=.015 F(1.90,115.90)=4.47, np2=.068, power=.741 |

| 37-40Hz | Laterality x group p=.014 F(1.90,116.16)=4.54, np2=.069, power=.748 |

| 41-45Hz | Laterality x group p=.013 F(1.91,116.43)=4.60, np2=.070, power=.755 |

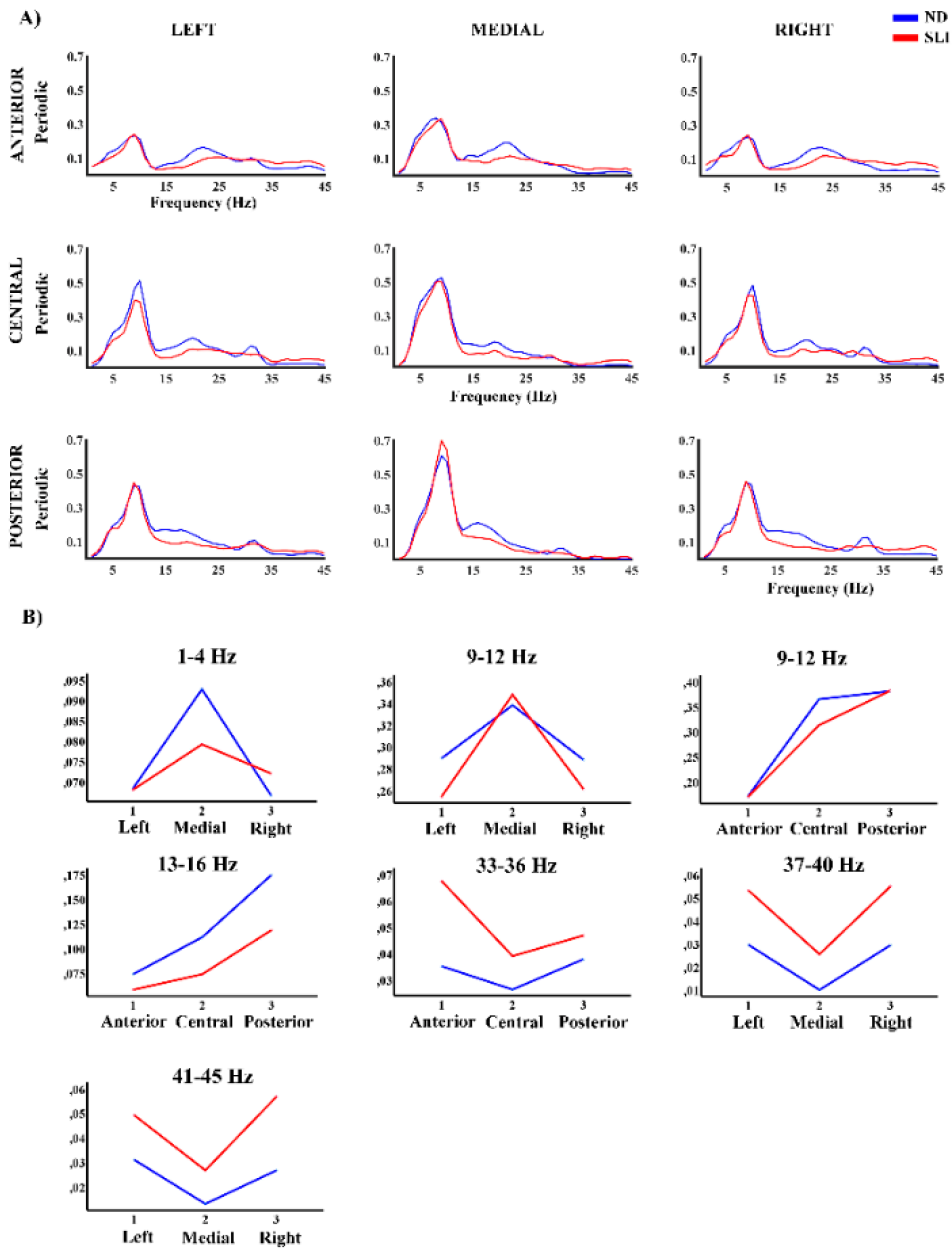

| RM_ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Within-subjects | Between-subjects |

| 1-4Hz | Laterality x group p=.050 F(1.98,120.93)=3.07, np2=.048, power=.581 |

- |

| 9-12Hz | Laterality x group p=.017 F(1.57,95.48)=4.78, np2=.073, power=.710 Antero-posterior x group p=.031 F(1.97,120.13)=3.59, np2=.056, power=.650 |

- |

| 13-16Hz | Antero-posterior x group p=.030 F(1.89,115.23)=3.69, np2=.057, power=.650 |

- |

| 33-36Hz | Antero-posterior x group p=.036 F(1.53,93.23)=3.84, np2=.059, power=.603 |

|

| 37-40Hz | - | Group p=.005 F(1,61)=8.61, np2=.124, power=.823 |

| 41-45Hz | Laterality x group p=.037 F(1.97,120.09)=3.40, np2=.053, power=.626 |

Group p=.006 F(1,61)=8.03, np2=.116, power=.796 |

| Aperiodic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency Range | Between-subjects | Within-subjects |

| 13-16Hz | Left-Medial (SLI>ND) Right-Medial (SLI>ND) |

|

| 17-20Hz | Left-Medial (SLI>ND) Right-Medial (SLI>ND) |

|

| 21-24Hz | Left-Medial (SLI>ND) Right-Medial (SLI>ND) |

|

| 25-28Hz | Left-Medial (SLI>ND) Right-Medial (SLI>ND) |

|

| 29-32Hz | Left-Medial (SLI>ND) Right-Medial (SLI>ND) |

|

| 33-36Hz | Left-Medial (SLI>ND) Right-Medial (SLI>ND)) |

|

| 37-40Hz | Left-Medial (SLI>ND) Right-Medial (SLI>ND) |

|

| 41-45Hz | Left-Medial (SLI>ND) Right-Medial (SLI>ND) |

|

| Periodic | ||

| 9-12Hz | Central-Anterior (ND>SLI) Posterior-Central (SLI>ND) |

|

| 33-36Hz | Anterior (SLI>ND) | |

| 37-40Hz | SLI>ND | |

| 41-45Hz | SLI>ND | Left (SLI>ND) Medial (SLI>ND) Right (SLI>ND) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).