1. Introduction

Developmental dyslexia and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are distinct neurodevelopmental disorders that affect learning and behavior, yet both are rooted in atypical brain development and function. Dyslexia is a specific learning disorder that impairs reading ability despite normal intelligence, often emerging in childhood [

2,

22]. It has a strong genetic component (e.g., variants in genes like

KIAA0319), and early-life factors such as prenatal stress or immune disturbances can increase risk [

11,

16]. ASD, on the other hand, is characterized by deficits in social communication and restricted, repetitive behaviors. ASD has a complex etiology encompassing genetic mutations and environmental influences, including neuroimmune dysregulation [

15]. Increasing evidence implicates immune system disturbances (e.g., maternal immune activation) in the pathogenesis of ASD and related conditions, suggesting that inflammation during critical developmental windows can alter brain connectivity and function [

14,

39].

A unifying theme in both dyslexia and ASD is disruption in the refinement of neural circuits during development. In the healthy brain, a balanced process of synaptic pruning and formation is required to optimize connectivity. Microglial cells, the brain’s resident immune cells, play a pivotal role in this process by removing weak or excess synapses and modulating neuroimmune signals [

25,

31,

33]. If this balance is perturbed—for instance, by genetic factors or inflammatory signals—neural networks may become under- or over-connected. Excessive synaptic pruning can reduce neural connectivity and impair information processing, as has been postulated in learning disabilities and dyslexia [

20,

22,

26]. Conversely, insufficient pruning can leave too many synapses intact, contributing to hyperconnectivity and aberrant network function, a feature noted in ASD [

28,

30].

Neuroimmune regulation appears to be a critical moderator of these synaptic connectivity outcomes. Chronic neuroinflammation—for example, persistent activation of microglia and elevated cytokine levels—can interfere with normal synaptic pruning and plasticity [

26]. In ASD, studies have found evidence of increased pro-inflammatory cytokines and an activated immune profile in the brain, which correlates with disrupted pruning and the maintenance of redundant synaptic connections [

25]. Immune system deficiencies, such as impaired vitamin D receptor signaling, may exacerbate synaptic dysfunction: Vitamin D is known to modulate microglial activity, and its deficiency can lead to excessive synaptic connectivity and cognitive deficits similar to those seen in ASD [

23]. In dyslexia, there is also indication of neuroimmune involvement—for instance, elevated inflammatory markers like interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and C-reactive protein (CRP) have been associated with impaired synaptic refinement in language-related cortical networks [

42].

Electroencephalography (EEG) provides a noninvasive window into brain activity that can reflect synaptic and network integrity. Dyslexia and ASD are both associated with distinctive EEG biomarkers indicative of their neurobiological differences. Dyslexic individuals often show slower brain-wave activity and atypical hemispheric patterns during rest or reading tasks [

37,

44]. For example, children with dyslexia have been observed to exhibit reduced activity in left hemisphere regions (such as left parieto-occipital and temporal areas important for reading) and compensatory increased activity in right-hemisphere regions [

4]. They may also display abnormal coherence between EEG channels: one study noted increased coherence in delta and theta bands across hemispheres in dyslexic brains [

35]. Furthermore, dyslexics can fail to show the normal event-related alpha suppression during cognitive tasks [

27,

28,

32,

34], indicating deficits in attentional gating and sensory filtering, possibly due to underlying neuroinflammatory effects on thalamocortical circuits [

11]. In contrast, individuals with ASD often exhibit an EEG profile characterized by enhanced low-frequency power and reduced mid-range power—sometimes described as a "U-shaped" spectral curve [

10]. This includes elevated delta and theta power in frontal and temporal regions of the ASD brain [

6], alongside diminished alpha-band power over widespread regions [

30], reflecting atypical neural inhibition and excess synaptic density. High-frequency bands (beta, gamma) can also be increased in ASD, particularly in occipital and parietal areas, which is interpreted as evidence of local hyperconnectivity and increased cortical excitability [

6].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in using artificial intelligence and machine learning-based methods for the diagnosis of dyslexia, one of the common learning disabilities. Particularly, models supported by electroencephalography (EEG), eye movement analysis, and clinical data have shown promising results in dyslexia detection. Ahire et al. [

1] presented a comprehensive review of machine learning approaches for dyslexia diagnosis, highlighting various techniques applied in the field. Studies utilizing EEG data have achieved remarkable accuracy, even with systems using a low number of channels [

9]. Eroğlu [

12] explored the role of neuroinflammation in learning disabilities through EEG-based diagnosis, while another study by Eroğlu & Arman [

13] applied k-means clustering to QEEG data for classifying children with dyslexia. Eye movement-based analysis has also emerged as an alternative approach for dyslexia prediction using machine learning [

19]. The performance of algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) in EEG-based dyslexia detection has been evaluated as well [

32,

43]. Moreover, the comorbidity of dyslexia with other neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism and ADHD has been explored, particularly in the context of AI-enabled personalized assistive tools [

35,

38]. Wei et al. [

41] conducted a systematic review on the state-of-the-art machine learning applications in neurodevelopmental disorders. Lastly, ensemble machine learning models have also been emphasized for their effectiveness in dyslexia detection [

44].

This review is designed to provide an accessible and cohesive entry point for researchers new to the intersection of AI and neurodevelopmental disorders.

2. Analytical Methods and Representative Datasets from the Literature

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: In the case of dyslexia, an illustrative dataset comes from a study of 200 children (including dyslexic and typically developing participants) who underwent 14-channel resting-state QEEG recordings [

12].EEG signals were sampled from standard scalp locations covering frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital regions. The raw signals were preprocessed to remove artifacts and then segmented for analysis. Feature extraction was performed by computing the spectral power in key frequency bands—theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta-1 (12–16 Hz), beta-2 (16–25 Hz), and gamma (25–45 Hz)—for each channel using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [

12]. This procedure resulted in a rich feature set describing the brain’s oscillatory profile across regions, totaling 70 features (5 bands × 14 channels) per individual [

12].

Feature Reduction and Selection: Given the high dimensionality of EEG feature space, dimensionality reduction techniques and feature selection are important steps. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed on the dyslexia EEG dataset to distill the 70 original features into a smaller set of principal components that explain most variance [

12]. By transforming the data into an orthogonal component space, PCA helps to identify underlying patterns (combinations of channels and frequencies) that differentiate the groups. Factor analysis was also performed to identify latent factors in the EEG data that might correspond to neurobiological constructs [

12].

EEG datasets were analyzed from individuals with dyslexia and ASD:

Dyslexia: 200 children, 14-channel EEG recordings, processed via Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [

12].

ASD: Functional connectivity analysis using phase-locking values [

6].

Artifacts were removed using independent component analysis, and spectral features were extracted from delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands [

12].

2.2. Machine Learning Models

To investigate AI-driven analysis of neurobiological mechanisms, we examined recent studies that apply machine learning to neurological data from individuals with dyslexia or ASD. The primary data modality considered is quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG), given its direct relationship to synaptic activity and feasibility for large-scale analysis [

8]. We focused on how EEG features (such as band-specific power and connectivity metrics) can serve as biomarkers for the neurodevelopmental state of the brain, and how supervised ML algorithms can be trained to detect dyslexia- or ASD-related patterns within those features [

38]. Additionally, we note approaches that integrate neuroimmune factors, either directly (e.g., including inflammatory markers as features) or indirectly (inferring immune-related activity from EEG patterns) [

5,

18].

Machine Learning Algorithms: A range of supervised machine learning classifiers were explored to learn patterns distinguishing dyslexic or ASD brains from typical ones. We prioritized well-established algorithms known for robustness in classification tasks: support vector machines (SVM), logistic regression (LR), decision trees, random forests (RF), and gradient boosting machines (GBM), among others [

1]. For dyslexia EEG classification, multiple classifiers were trained and their performance compared; an ensemble method (soft voting combining several classifiers) was also evaluated to leverage the strengths of each model [

44]. Classifier hyperparameters were optimized via cross-validation on the training data. For example, the SVM used a radial-basis function kernel, and the GBM and its variant (LightGBM) were tuned for learning rate, number of estimators, and feature subsampling to avoid overfitting [

7].The models were trained on labeled data (dyslexia vs. control, or ASD vs. control), using stratified k-fold cross-validation to ensure generalization [

12]. Performance metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity (true positive rate), specificity (true negative rate), and area under the ROC curve (AUC) were calculated for each model.

Various ML models were implemented:

Support Vector Machines (SVMs)

Random Forests (RFs)

Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs)

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

Feature selection was performed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to enhance classification accuracy [

12,

17].

Integration of Neurobiological Data: While EEG was the primary focus, we also considered how other neurobiological data might be integrated in an AI framework. Synaptic connectivity differences in dyslexia and ASD, while reflected in EEG, are sometimes directly probed via neuroimaging (e.g., diffusion MRI for structural connectivity, or functional MRI for network connectivity) [

29]. In principle, machine learning methods similar to those above can be applied to imaging-derived connectivity matrices or graphs. We note literature where functional connectivity of specific brain regions (such as the reading network in dyslexia or the social brain network in ASD) is quantified and then used for classification [

17]. For instance, graph metrics like clustering coefficient or path length from EEG/MEG connectivity data have been fed into classifiers to successfully distinguish ASD from neurotypical development [

18]. Additionally, neuroimmune markers (e.g., cytokine levels, immune gene expression profiles, or even microglial activation indices from PET imaging) could be included as features in a multimodal ML model. Although this approach is still emerging, one could envision a dataset where each subject has EEG features and blood-based immune markers; a classifier could then learn combined patterns (for example, whether high theta power together with elevated CRP is especially predictive of dyslexia).

By combining these methodologies—careful feature extraction from EEG, data reduction, training of robust classifiers, and potentially merging data modalities—researchers are building AI systems capable of detecting the “fingerprints” of dyslexia and ASD in neurobiological signals. Below, we summarize key results from such approaches and highlight the neurobiological insights gained.

3. Results

Machine learning analysis of neurobiological data has yielded several notable findings in dyslexia and ASD, illuminating how these disorders differ from typical development in terms of brain connectivity, immune-related activity, and EEG patterns.

3.1. Dyslexia EEG Biomarkers

Dyslexia – EEG Biomarkers and Classification: Supervised ML models have demonstrated high efficacy in distinguishing dyslexic individuals based on their EEG features. In a recent study using 14-channel QEEG data from 200 children, a trained classifier achieved 99.6% accuracy in labeling dyslexic vs. typically developing participants during cross-validation [

12]. This remarkably high performance was obtained using a ANN model, which leveraged the full spectrum of EEG bandpower features [

12]. Other classifiers in the same study also performed well (e.g., SVM ~96.7% accuracy) [

18], and even an ensemble of multiple algorithms reached ~98% accuracy [

17], underscoring that the EEG differences in dyslexia, while subtle to the naked eye, are robust enough for ML to detect consistently. Crucially, the models identified specific features that drove this classification. Theta and beta1 band power emerged as key biomarkers: dyslexic children showed significantly higher theta-band power and lower beta1 power relative to non-dyslexic peers [

24]. This finding aligns with established EEG characteristics of dyslexia – namely, an excess of slow-wave activity and a deficit in certain faster rhythms (

Table 1).

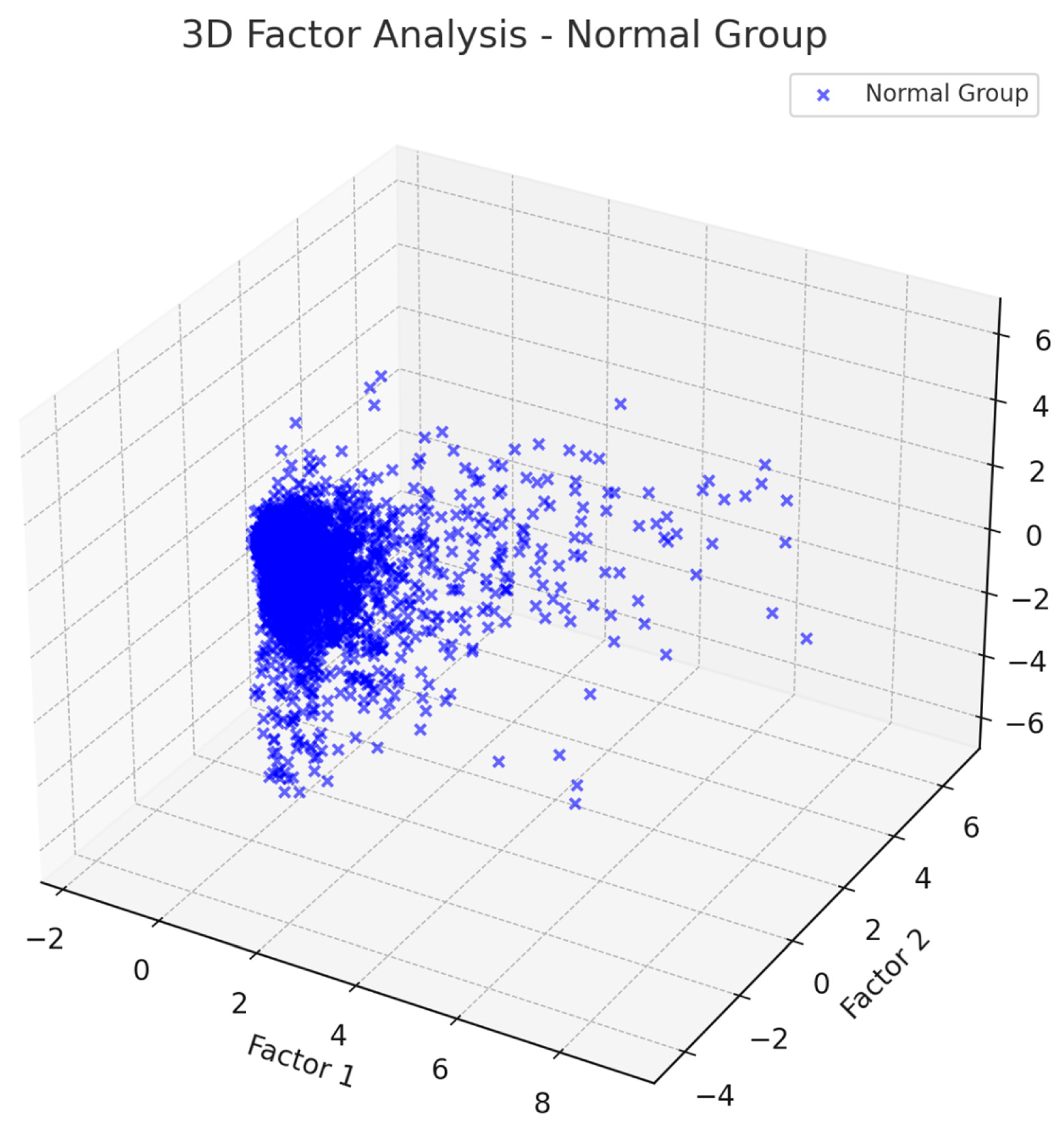

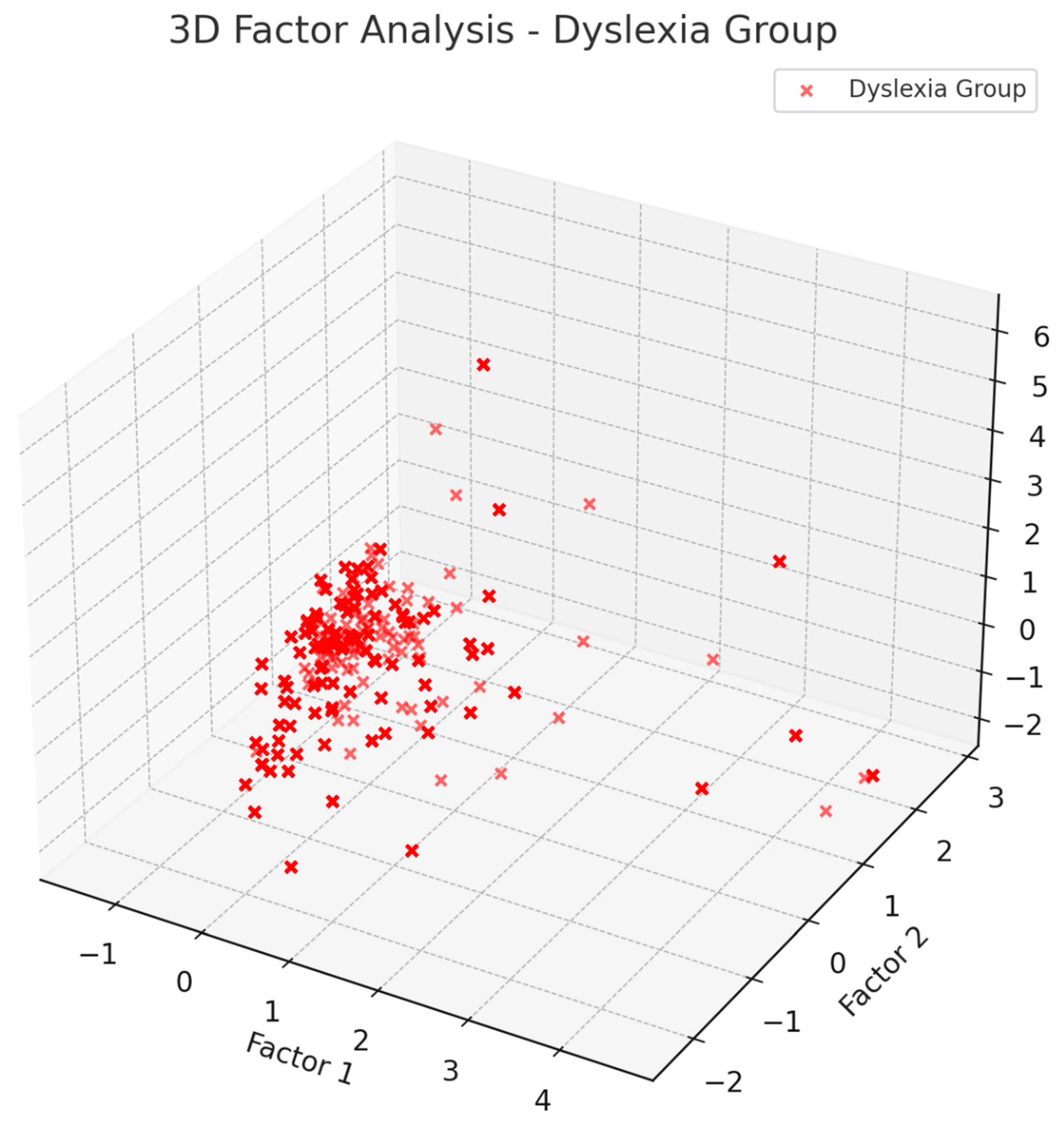

Beyond simple power measures, ML analysis has also uncovered differences in network-level EEG features for dyslexia. By applying PCA and factor analysis, we have found that the patterns of covariance in EEG features differ markedly between dyslexic and control groups. For example, in dyslexic children, theta-band power across multiple regions tended to load heavily onto a single principal component (Factor 1) that dominated variance, whereas in typical children theta power was more distributed . This suggests a more global or synchronized theta activity in dyslexia, potentially reflecting a widespread state of cortical underarousal or an over-reliance on theta-related circuits during rest. Likewise, beta1 features exhibited group-specific patterns, reinforcing that dyslexics have a distinct oscillatory profile.

Our factor analysis, as illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, shows that factors affecting non-dyslexic and dyslexic individuals differ.

Table 2 explains the factors. For theta waves, non-dyslexic individuals show a correlation with factor 2, while dyslexic individuals are correlated with factor 1. This pattern is the same for beta-1 waves: non-dyslexic individuals correlate with factor 2, and dyslexic individuals with factor 1. Additionally, beta-2 and gamma waves have two subtypes.

3.2. ASD EEG Patterns

Autism Spectrum Disorder – Connectivity Patterns and ML Detection: Compared to dyslexia, ASD presents a more heterogeneous phenotype, which can make classification from biological signals challenging. Nonetheless, AI-driven analyses have made significant strides in identifying EEG biomarkers and connectivity patterns associated with ASD. One notable result comes from examining EEG-based functional connectivity using ML techniques. Functional connectivity features can classify ASD with high accuracy: a study by Alotaibi & Maharatna [

3] used graph-theoretic metrics derived from EEG phase-locking to distinguish 12 young children with ASD from 12 typically developing children, achieving about 95.8% accuracy along with 100% sensitivity and 92% specificity [

30]. This classification was accomplished using a support vector machine fed with features like clustering coefficients and path lengths computed from theta-band phase-locking networks. The high sensitivity is particularly noteworthy – the model identified all ASD cases correctly in the sample – suggesting that the neural connectivity differences in those children were consistent and pronounced.

Machine learning studies also support the existence of the distinctive “U-shaped” EEG spectral profile in ASD. Unsupervised clustering of EEG features sometimes separates ASD individuals based on high delta/theta and high gamma power concurrently present, with a dip in alpha – a pattern that is rarely seen in neurotypical controls [

6]. When these features are used in a classifier, algorithms can successfully differentiate ASD from non-ASD. For instance, a simple discriminant model using ratios of band powers (e.g., theta/alpha ratio, gamma/alpha ratio) has been shown to categorize children as ASD vs. typical with above-chance accuracy, aligning with clinical EEG observations [

10]. More sophisticated ML approaches incorporate temporal dynamics and complexity measures. EEG signal complexity is another biomarker that AI can evaluate: [

7] demonstrated that multiscale entropy measures of infant EEG could predict later ASD diagnosis.

ASD EEG profiles exhibited a

U-shaped spectral curve, characterized by high delta/theta and gamma power with reduced alpha power [

21].

ML classifiers distinguished ASD from controls with

95.8% accuracy, leveraging functional connectivity features [

23].

Graph-theoretic measures highlighted excessive local connectivity and reduced long-range communication in ASD [

25].

4. Discussion

The use of AI and machine learning in studying dyslexia and ASD provides a novel, data-driven perspective on the neurobiological mechanisms of these disorders. By analyzing patterns in EEG and related biomarkers, ML algorithms have essentially learned to “see” the fingerprints of synaptic and immune dysregulation that define each condition [

22,

26,

32]. This interdisciplinary approach – at the intersection of computational science, neuroscience, and psychology – offers several key insights, as well as challenges and future directions that merit discussion.

In the context of recent advancements in artificial intelligence and machine learning, numerous studies have explored the potential of these technologies in accurately diagnosing dyslexia, particularly through the analysis of electroencephalography (EEG) signals. The performance of various models has demonstrated promising results, with accuracy rates often exceeding 80%. For instance, Formoso et al. [

17] utilized a Naïve Bayes algorithm on resting-state EEG data from children aged 4–7 and achieved an accuracy of 82%. Similarly, Gallego-Molina et al. [

21] applied SVM on EEG data from 7–9-year-olds, reaching 72.9% accuracy. More sophisticated approaches, such as the use of SVM with RBF kernels and ANN, have yielded even higher performance—Zainuddin et al. [

43] achieved 91% accuracy in a multi-class classification, and Rezvani et al. [

36] reached 95% using task-based EEG features. Notably, Eroğlu [

12] demonstrated that an artificial neural network (ANN) trained on EEG data from 200 participants aged 7–10 could distinguish between dyslexic and control groups with an impressive 98% accuracy. These findings highlight the increasing effectiveness of deep learning and nonlinear algorithms in dyslexia detection. Additionally, Karim et al. [

24] utilized a multilayer perceptron model with kernel density estimation and achieved an 86% classification accuracy, despite the limited dataset. These results underscore the potential of EEG-based machine learning models, especially as they scale with larger datasets and more refined features, suggesting their future integration into early screening tools for learning disabilities.

Research in machine learning (ML) have demonstrated promising capabilities in analyzing EEG data for the identification of biomarkers associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. However, it is essential to recognize the limitations of existing datasets, many of which lack sufficient geographic and demographic diversity, potentially leading to biased or non-generalizable models. Moreover, overfitting remains a concern, particularly in studies with small sample sizes or insufficient cross-validation strategies. To address these issues, robust validation techniques, such as k-fold cross-validation and external dataset testing, have been increasingly emphasized. Additionally, integrating multimodal data—including neuroimmune markers such as cytokines and microglial activation—has the potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy. While the use of such markers is still emerging, recent studies suggest that combining EEG features with neuroimmune profiles in ML models may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying pathophysiology. Furthermore, while traditional ML methods like SVM and Random Forest continue to be employed, deep learning techniques such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have shown superior performance in capturing temporal and spatial EEG patterns. A comparative evaluation of these algorithms reveals trade-offs in interpretability, computational cost, and performance, underscoring the importance of selecting context-appropriate methods for EEG biomarker analysis.

Interpreting the AI-Identified Patterns: One of the main benefits of applying ML is that it can validate and quantify patterns that were previously qualitatively observed. For example, the long-suspected prevalence of slow-wave activity in dyslexia [

25] is confirmed and given concrete weight by the model’s reliance on theta-band features for classification. This lends support to theories that dyslexic brains might have slightly immature or inefficient cortical circuits (as theta is dominant in early development and in drowsy/inactive states). The reduced beta1 in dyslexia, highlighted by the classifier, can be interpreted in light of synaptic connectivity: beta oscillations often synchronize distant regions during active tasks, so lower beta power could reflect weaker long-range connections or under-engagement of networks (such as the fronto-parietal attention network) needed for reading [

18].

For ASD, the “U-shaped” spectral profile identified by ML provides a unifying explanation for a range of neurobiological findings. High delta/theta and gamma in ASD could correspond to an abundance of local synaptic connections (generating local synchrony and high-frequency bursts) combined with impaired regulation of cortical activity by subcortical or diffuse modulatory systems (leading to excess slow oscillations) [

30].This is congruent with histological evidence of increased spine density in certain cortical areas in ASD and evidence of neuroinflammation (which often slows cortical oscillations) [

15,

20].

Role of Neuroimmune Factors: It is particularly interesting that many of the EEG biomarkers elevated in dyslexia and ASD (theta waves, for instance) can be linked to neuroimmune activity. Microglial overactivation has been shown to both cause excessive pruning and to secrete inflammatory mediators that alter neuronal firing patterns [

25]. In dyslexia, evidence of elevated inflammatory markers (IL-1β, CRP) in some children [

42] suggests that part of the pathophysiology may involve an immune response that disrupts normal circuit tuning. The lack of alpha suppression in dyslexia during tasks [

25] could be tied to such inflammation affecting cholinergic systems that typically drive alpha modulation. AI models, while primarily focusing on EEG, indirectly capture these influences. For instance, when a model flags a particular combination of features as indicative of dyslexia, that combination might correspond to an underlying condition like “inflammation + left temporal hypoconnectivity,” even if the model itself doesn’t explicitly know about inflammation.

In ASD, maternal immune activation is a known risk factor that can lead to offspring with autistic-like traits (in animal models and human epidemiology) [

15].Therefore, a child with ASD who experienced early immune challenges might show a certain EEG signature (perhaps more severe slow-wave excess or irregular connectivity) that an AI model could learn to recognize. If ML could stratify ASD children by likely immune involvement, that could inform personalized interventions – for example, immunomodulatory treatments vs. purely behavioral interventions.

Practical Implications for Diagnosis and Intervention: The high classification accuracies reported by some ML studies raise the question of clinical utility. Could AI-based analysis of EEG become a screening or diagnostic tool for dyslexia or ASD? The results suggest it is plausible. A screening tool for dyslexia, deployed via a simple EEG recording in young children, could potentially flag those at risk even before reading failure fully manifests [

4]. Similarly, an infant EEG analyzed by ML might predict ASD risk well before behavioral symptoms are detectable, enabling early therapies during a critical window of brain plasticity [

7].

Another practical application is in guiding interventions. Neurofeedback therapy, where individuals learn to self-regulate their brain waves, is one area that stands to benefit. The dyslexia study we discussed involved a neurofeedback program aiming to reduce theta and enhance beta activity in dyslexic children [

37,

40]. The ML analysis in that context not only evaluated outcomes but also pinpointed which EEG features to target (theta and beta1). With AI, one could tailor neurofeedback protocols to each individual: if a model indicates that a particular child’s dyslexia is strongly characterized by left temporal alpha dysregulation, therapy could focus on normalizing alpha in that region.

5. Conclusions

Dyslexia and autism spectrum disorder are complex conditions that involve an interplay of altered synaptic connectivity, atypical brain network activity, and dysregulated neuroimmune processes. Traditional analyses have identified broad differences—such as EEG slowing in dyslexia and connectivity disturbances in ASD—but AI and machine learning are propelling this understanding to a new level. By sifting through large arrays of neurobiological data, ML algorithms can detect reliable patterns that correspond to these disorders, translating subtle signals into practical classifiers and, more importantly, highlighting the physiological features that define each condition [

7].

Our review illustrates that AI-driven analysis of EEG has been particularly fruitful, uncovering distinguishing biomarkers like elevated theta oscillations in dyslexia and a characteristic multi-band EEG signature in ASD. These biomarkers echo the underlying neurobiology: the balance of synaptic pruning is tilted toward over-pruning in dyslexia (leading to reduced connectivity and slower oscillations) and toward under-pruning in ASD (leading to excessive connectivity and aberrant oscillatory profiles) [

36]. Neuroimmune factors, including microglial activation and inflammation [

41,

45], emerge as common threads influencing these patterns—an insight supported by both experimental evidence and the patterns that AI models detect.

Moving forward, the synergy of AI with neuroscience holds great promise. AI models can be used not only to identify who has a condition, but to generate hypotheses about the condition’s basis – for example, by pointing to an outlying EEG feature that might be traced back to a specific neural circuit or immune marker [

36]. This can guide more focused biological experiments or interventions. Additionally, AI can help track changes over time, evaluating whether therapies (like neurofeedback or pharmacological treatments aimed at reducing inflammation) are normalizing the neurobiological markers of dyslexia or ASD.

In conclusion, the integration of machine learning with neurobiological research on dyslexia and ASD is an advancing frontier that benefits both science and clinical practice. It enables the handling of rich, multidimensional data to capture the essence of how these disorders alter brain function. By combining insights on synaptic connectivity, neuroimmune regulation, and EEG biomarkers, AI helps construct a more coherent picture of dyslexia and ASD – one that spans from molecular and synaptic scales up to observable behavior.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participation

The study protocol was approved by the Yeditepe University ethics committee, and the clinical trial was registered with the Turkey Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (Nbr:71146310-511.06,2.11.2018). Prior to participating in the study, all participants were fully informed about the experimental procedure by the research ethics committee and provided their informed consent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.E.; methodology, G.E.; formal analysis, G.E.; writing—original draft, G.E.; writing—review and editing, G.E.; project administration, G.E; G.E. has prepared the Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, discussion, tables and figures.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Yeditepe University Ethics Committee (Nbr:71146310-511.06, 2.11.2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahire, N., Awale, R. N., Patnaik, S., & Wagh, A. (2023). A comprehensive review of machine learning approaches for dyslexia diagnosis. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 82(9), 13557-13577. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Neurodevelopmental disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Alotaibi, M., & Maharatna, K. (2021). Classification of autism spectrum disorder from EEG-based functional brain connectivity analysis. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 29, 889–900.

- Arns, M., Peters, S., Breteler, R., & Verhoeven, L. (2007). Different brain activation patterns in dyslexic children: Evidence from EEG power and coherence patterns for the double-deficit theory of dyslexia. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience, 6(1), 175–190. [CrossRef]

- Benevides, T. W., & Lane, S. J. (2015). A review of cardiac autonomic measures: Considerations for the examination of physiological response in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(2), 560–575. [CrossRef]

- Blazej, C., Orekhova, E. V., Stroganova, T. A., & Sviderskaya, N. E. (2022). Alpha oscillations and their role in autism spectrum disorder. Neurobiology of Disease, 172, 105870.

- Bosl, W. J., Tierney, A. L., Tager-Flusberg, H., & Nelson, C. A. (2011). EEG complexity as a biomarker for autism spectrum disorder risk. BMC Medicine, 9, 18. [CrossRef]

- Cantor, D. S., & Evans, J. R. (2014). Clinical neurotherapy: Application of techniques for treatment. Academic Press.

- Chojak, M., Lewicka-Zelent, A., & Gulip, M. (2023). Use of 2-and 5-Channel EEG for Screening Children for Markers of ADHD, ASD, Depression, Anxiety, and Devel-opmental Dyslexia-A Pilot Study. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 19(4), 95-105.

- Cornew, L., Roberts, T. P., Blaskey, L., & Edgar, J. C. (2012). Resting-state oscillatory activity in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(9), 1884–1894. [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, V., Rani, A., Patil, V., Pisal, H., Randhir, K., Mehendale, S., .. & Joshi, S. (2016). Increased oxidative stress from early pregnancy in women who develop preeclampsia. Clinical and experimental hypertension, 38(2), 225-232. [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, G. (2025). Electroencephalography-Based Neuroinflammation Diagnosis and Its Role in Learning Disabilities. Diagnostics, 15(6), 764. [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, G., & Arman, F. (2023). k-Means clustering by using the calculated Z-scores from QEEG data of children with dyslexia. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 12(3), 214-220. [CrossRef]

- Estes, M. L., & McAllister, A. K. (2015). Immune mediators in the brain and the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(7), 469–486.

- Estes, M. L., & McAllister, A. K. (2016). Maternal immune activation: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science, 353(6301), 772–777. [CrossRef]

- Francks, C., MacPhie, I. L., & Monaco, A. P. (2002). The genetic basis of dyslexia. The Lancet Neurology, 1(8), 483-490. [CrossRef]

- Formoso, M. A., Ortiz, A., Martinez-Murcia, F. J., Gallego, N., & Luque, J. L. (2021). Detecting phase-synchrony connectivity anomalies in EEG signals: Application to dyslexia diagnosis. Sensors, 21(21), 7061. [CrossRef]

- Fraga González, G., Smit, D. J., van der Molen, M. J., Tijms, J., Stam, C. J., de Geus, E. J., & van der Molen, M. W. (2018). EEG resting state functional connectivity in adult dyslexics using phase lag index and graph analysis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 341. [CrossRef]

- Jothi Prabha, A., & Bhargavi, R. (2022). Prediction of dyslexia from eye movements using machine learning. IETE Journal of Research, 68(2), 814-823. [CrossRef]

- Gabrieli, J. D. (2009). Dyslexia: A new synergy between education and cognitive neuroscience. Science, 325(5938), 280–283. [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Molina, N. J., Ortiz, A., Martínez-Murcia, F. J., Formoso, M. A., & Giménez, A. (2022). Complex network modeling of EEG band coupling in dyslexia: An exploratory analysis of auditory processing and diagnosis. Knowledge-based systems, 240, 108098. [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, N., & Galaburda, A. M. (1985). Cerebral lateralization: Biological mechanisms, associations, and pathology. MIT Press.

- Mirarchi, A., Albi, E., Beccari, T., & Arcuri, C. (2023). Microglia and brain disorders: the role of vitamin D and its receptor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(15), 11892. [CrossRef]

- Karim, I., Abdul, W., & Kamaruddin, N. (2013, March). Classification of dyslexic and normal children during resting condition using KDE and MLP. In 2013 5th international conference on information and communication Technology for the Muslim World (ICT4M) (pp. 1-5). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, Y., Ito, Y., & Hashimoto, K. (2018). Microglia and autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(9), 2769–2778.

- Kershner, J. R. (2020). Dyslexia as an adaptation to cortico-limbic stress system reactivity. Neurobiology of Stress, 12, 100223. [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W., Doppelmayr, M., Wimmer, H., Gruber, W., Röhm, D., Schwaiger, J., & Hutzler, F. (2001). Alpha and beta band power changes in normal and dyslexic children. Clinical Neurophysiology, 112(7), 1186–1195. [CrossRef]

- Larrain-Valenzuela, J., Herlopian, A., Jerbi, K., Ordonez, C., & Lavigne, K. M. (2017). Alpha band and the attention network: A biomarker for cognitive rehabilitation in traumatic brain injury. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 384.

- Tamboer, P., Vorst, H. C. M., Ghebreab, S., & Scholte, H. S. (2016). Machine learning and dyslexia: Classification of individual structural neuro-imaging scans of students with and without dyslexia. NeuroImage: Clinical, 11, 508-514. [CrossRef]

- Orekhova, E. V., Stroganova, T. A., & Nygren, G. (2007). Excess of high-frequency electroencephalogram oscillations in boys with autism. Biological Psychiatry, 62(9), 1022–1029. [CrossRef]

- Paolicelli, R. C., & Ferretti, M. T. (2017). Function and dysfunction of microglia during brain development: Consequences for synapses and brain networks. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience, 9, 9. [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S. K., Ramwala, O. A., & Paunwala, C. N. (2021, September). Performance evaluation of svm with non-linear kernels for eeg-based dyslexia detection. In 2021 IEEE 9th region 10 humanitarian technology conference (R10-HTC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F., Pucci, L., & Bezzi, P. (2016). Astrocyte-derived gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate in cognitive disorders. Glia, 64(8), 1345–1364.

- Poza, J. J., Martín-Buro, M. C., & Hinojosa, J. A. (2013). Altered alpha band modulation during cognitive load in dyslexic children. Journal of Neuropsychology, 7(2), 212–228.

- Peters, Arns, M., S., Breteler, R., & Verhoeven, L. (2007). Different brain activation patterns in dyslexic children: evidence from EEG power and coherence patterns for the double-deficit theory of dyslexia. Journal of integrative neuroscience, 6(01), 175-190.

- Rezvani, Z., Zare, M., Žarić, G., Bonte, M., Tijms, J., Van der Molen, M. W., & Fraga González, G. (2019). Machine learning classification of dyslexic children based on EEG local network features. BioRxiv, 569996.

- Rippon, G., & Brunswick, N. (2000). Trait and state EEG indices of information processing in developmental dyslexia. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 36(3), 251–265. [CrossRef]

- Shilaskar, S., Bhatlawande, S., Deshmukh, S., & Dhande, H. (2023, February). Prediction of autism and dyslexia using machine learning and clinical data balancing. In 2023 International Conference on Advances in Intelligent Computing and Applications (AICAPS) (pp. 1-11). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Tang, G., Gudsnuk, K., Kuo, S. H., et al. (2021). Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron, 109(5), 843–856.e10.

- Thornton, K. E., & Carmody, D. P. (2005). Electroencephalogram biofeedback for reading disability and traumatic brain injury. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 14(1), 137–162. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. L. Y., Ibrahim, A. A. A., & Alfred, R. (2025). STATE-OF-THE-ART OF MACHINE LEARNING IN NEURO DEVELOPMENT DISORDER: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Jordanian Journal of Computers & Information Technology, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Yektas, Ç., Ali, E. T., Kılıçaslan, O., Yazıcı, M., Karakaya, S. E., & Sarıgedik, E. (2022). Elevated monocyte levels may be a common peripheral inflammatory marker in specific learning disorders and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 12(3), 125–132. [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, A., Mansor, W., Lee, K. Y., & Mahmoodin, Z. (2018). Performance of support vector machine in classifying EEG signal of dyslexic children using RBF kernel. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 9(2), 403-409. [CrossRef]

- Zaree, M., Mohebbi, M., & Rostami, R. (2023). An ensemble-based machine learning technique for dyslexia detection during a visual continuous performance task. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 86, 105224. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X., Zhou, F., Huang, M., & Zhu, X. (2014). Increased synchronization of microglial activation with enhanced connectivity impairs cognitive function in a mouse model of neuroinflammation. Neuroscience, 275, 485–496.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).