1. Introduction

Emerging evidence suggests that neuroinflammation may contribute to the pathophysiology of developmental dyslexia. Altered microglial activation and impaired synaptic pruning during critical neurodevelopmental periods have been implicated in dyslexic brain architecture (Paolicelli et al., 2017; Paolicelli et al., 2022). Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP) have been reported in children with learning disabilities, including dyslexia (Mostafa &Al-Ayadhi, 2013; Gialloreti et al., 2020). These immune alterations may disrupt fronto-temporal connectivity and modulate cortical oscillatory activity—particularly in the theta and beta frequency bands—which are frequently observed as deviant in EEG studies of dyslexia (Frid & Manevitz, 2018; Eroğlu et al., 2022). Together, these findings suggest that EEG spectral features may serve as non-invasive proxies for underlying neuroimmune dysfunction, although further multimodal validation is required.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to propose and validate an artificial neural network (ANN) model that uses resting-state EEG spectral features as potential non-invasive proxies of neuroinflammation in children with developmental dyslexia. While prior research has identified abnormal cortical oscillations in dyslexia and separate studies have explored the neuroimmune basis of learning disorders, no previous work has systematically linked EEG-derived features to neuroinflammatory biomarkers within a machine learning framework. Our findings offer a novel approach to bridging electrophysiological signals and neuroimmune dysfunction, opening new possibilities for scalable, home-based screening tools for neurodevelopmental risk assessment.

Specific developmental learning disabilities (LD), such as dyslexia, are believed to impact 5–10% of the world's population. It is, however, under-recognized by families and educators (Carroll et al. 2025). For example, the prevalence of dyslexia in Turkey is as low as 5% of the population with a diagnosis, even though the actual prevalence is estimated to be much higher (Yavuz et al., 2022). An early diagnosis is key, particularly in childhood due the stronger neuroplasticity of the brain and the impact of intervention.

On a neurological level, individuals with reading disabilities show decreased activation in the left-lateralized reading network, altered functional connectivity, and structural abnormalities (Frid & Manevitz, 2018). Such irregularities lead to core features of reading disorder, slow and inaccurate word reading, poor spelling, and reading comprehension problems (Cusiter et al., 2025). As reading is a learning task that presumably depends on hemispheric specialization in about age seven (Feng et al., 2005), late identification can have long-lasting effects on academic performance and well-being. This study investigates whether EEG spectral abnormalities observed in dyslexia, such as elevated theta power, may partially reflect underlying neuroimmune processes.

Recent technological advancements in neuroimaging and AI opened new potentials for diagnoses of dyslexia. The fMRI, MEG and eye-tracking studies are high in accuracy but they tend to be high-cost and not always child-friendly. EEG, however, is relatively more affordable and manageable; nevertheless, in the past, it exhibited average classification performance when applied with traditional algorithms (Usman & Muniyandi, 2020).

QEEG may provide a promising future avenue for dyslexia-related biomarkers by finding spectral disturbances in the EEG. SVMs and ANNs based studies reported classification accuracies ranging from 78 to 89% (Frid & Manevitz, 2018; Usman & Muniyandi, 2020). Recent studies have applied various machine learning algorithms to EEG-based dyslexia classification, reporting promising but varied results. Support Vector Machines (SVM) have been widely used due to their robustness in high-dimensional data; for instance, Frid and Manevitz (2018) achieved an accuracy of 93.2% using SVM with temporal EEG features. Ensemble methods such as Random Forests and Gradient Boosting Machines have also shown competitive performance, with accuracies ranging from 85% to 94% (Jin & Wang, 2023). Deep learning approaches, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have gained attention for their ability to learn spatial patterns from raw EEG; Ahire et al. (2024) reported a classification accuracy of 96.4% using CNNs on QEEG data. However, most of these models are stuck within laboratory environments and not generalizable. Compared to these approaches, our ANN-based model achieved 98.8% accuracy with fewer computational requirements and improved real-time deployability due to its lightweight TFLite implementation. This suggests that shallow ANN architectures, when properly optimized and combined with rigorous preprocessing, can perform comparably or even surpass more complex models in specific use cases such as home-based screening.

1.1. Related Work

Novel machine learning (ML) techniques are applied to extract clinically meaningful patterns from electroencephalography (EEG) data-Patients with neurodevelopmental and neuroinflammatory disorders. Eroğlu (2025) showed, how EEG-based biomarkers can be used to diagnose neuroinflammation underpinning learning disorders in children, starting point for non-invasive, scalable screening approaches. Similarly, Mezzaroba et al. (2020) utilized ML for identification of antioxidant and inflammatory biomarkers of multiple sclerosis, and provided evidence on the contribution of immune dysregulation to neurodegeneration. Lazaros et al. (2024) subsequently applied this approach to Alzheimer’s disease by integrating ML with immunocytochemical characterization of buccal epithelial cells, demonstrating the versatility of ML in a variety of biological formats.

These studies, however, illustrate the promise of using ML to identify neuroimmune dysfunction, yet they primarily include adult populations, peripheral biomarkers, or lab-based measures. There is still a significant need for the use of ML for pediatric EEG data, particularly in real-world/homesettings. This gap is partly filled by the current study with the development of a new EEG-ANN model derived from a dataset with only pediatric patients and trained to diagnose neuroinflammation-related neural dysfunction alongside dyslexia; thus closer to the clinical practice of a community and educational setting.

1.1.1. EEG as Non-Invasive Neuroinflammation (EEG-NIN) Biomarker

EEG provides an unparalleled look at time-resolved neurophysiological dynamics and is especially sensitive to the cortical mediated abnormalities in oscillations that would accompany inflammatory and perturbed synaptic pruning. Encephalitic/ neuroinflammatory states have also been associated with disrupted EEG patterns, such as increased theta and gamma power, potentially reflecting glial overactivity and prognostically unfavorable oxidative stress and cytokine-induced network instability (Jaramillo, 2024; Jin & Wang, 2024).

For instance:Abnormal EEG findings of elevated low-frequency power and reduced alpha coherence are reported in both neuroinflammatory and neurodevelopmental disorders (Usman & Muniyandi, 2020).

EEG modifications are associated with systemic indexes of immune activation, such as up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and vitamin D deficiency, which influence the cognitive processing (Chen et al., 2019).

The CSF markers provide a more precise estimation, not achievable with peripheral measures like CRP, which is poorly reflective of the central inflammation, however, its measurement by lumbar puncture is invasive, and is not practicable in children in routine practice (Singhal et al., 2014).

EEG, therefore, appears to be a useful noninvasive proxy for monitoring brain inflammation, even more so when combined with ML techniques that may improve the sensitivity in diagnosing.

1.1.2. Technical and Pragmatic Issues

While EPOC-X is not a clinical EEG, its signal reliability and validity for research applications have been established (Badcock et al., 2013). A pre-use calibration was performed during each session and only recordings with EMOTIV signal quality ratings greater than 80% as reported by the EMOTIV Launcher (EMOTIV Systems Inc., 2010) were included. This renders the device a potential viable option for domestic settings, specifically in pediatrics and low resource settings.

1.1.3. EEG as a Non-Invasive Biomarker of Neuroinflammation

EEG provides a special (albeit not perfect) means to monitor on-line neurophysiological activity and seems especially prone to observe cortical oscillatory abnormalities induced by inflammation and/or impaired synaptic pruning (Jaramillo, 2024; Jin & Wang, 2024).

EEG would represent a non-invasive substitute to detect brain inflammation given the possibility of its combination with ML techniques, thus maximizing the sensitive of diagnosis.

1.1.4. Objectives and Research Questions

This study hypothesizes that spectral features derived from resting-state EEG—particularly elevated theta power and altered beta1 activity—can be used to accurately classify children with developmental dyslexia and may serve as non-invasive neurophysiological proxies for underlying neuroinflammatory processes. This study explores the possibility that electrophysiological signals may be associated with neuroimmune dysregulation observed in dyslexia. However, no direct causal links are tested or implied.

Clinical Relevance: As CSF analysis of neuroinflammation is invasive and CRP is a poor marker, it is reasonable that EEG with ML can serve as a non-invasive and practical tool for neuroinflammation detection, especially in children.

In the context of this study, “neuroinflammation-related neural dysfunction” refers to alterations in neural activity that are hypothesized to arise from immune-mediated processes in the brain, such as glial activation, cytokine imbalance, oxidative stress, and impaired synaptic pruning. These mechanisms are known to affect neural connectivity, signal synchronization, and oscillatory patterns relevant to cognitive function.

Similarly, “neuroinflammatory EEG signatures” are operationally defined as deviations in EEG spectral features—particularly increased power in low-frequency bands (theta and delta), reduced alpha coherence, and elevated variability in beta and gamma bands—which have been previously associated with neuroinflammatory processes in both clinical and experimental research (Mezzaroba et al., 2023; Jaramillo, 2024; Neo et al., 2023).

The term “immune-related cognitive dysfunction” in this study refers to cognitive impairments potentially modulated by systemic or neuroinflammatory processes, as supported by prior evidence linking immune activation to altered neural development and synaptic function (e.g., Estes & McAllister, 2015). This includes conditions where dysregulated cytokine levels or microglial activity influence cortical maturation, attention, or learning capacity—especially during critical developmental windows. Although these markers are not direct indicators of inflammation, they are hypothesized to reflect downstream electrophysiological correlates of such processes. The current study adopts a cautious interpretation of these EEG features as potential proxies requiring multimodal validation in future research.

2. Methodology Overview

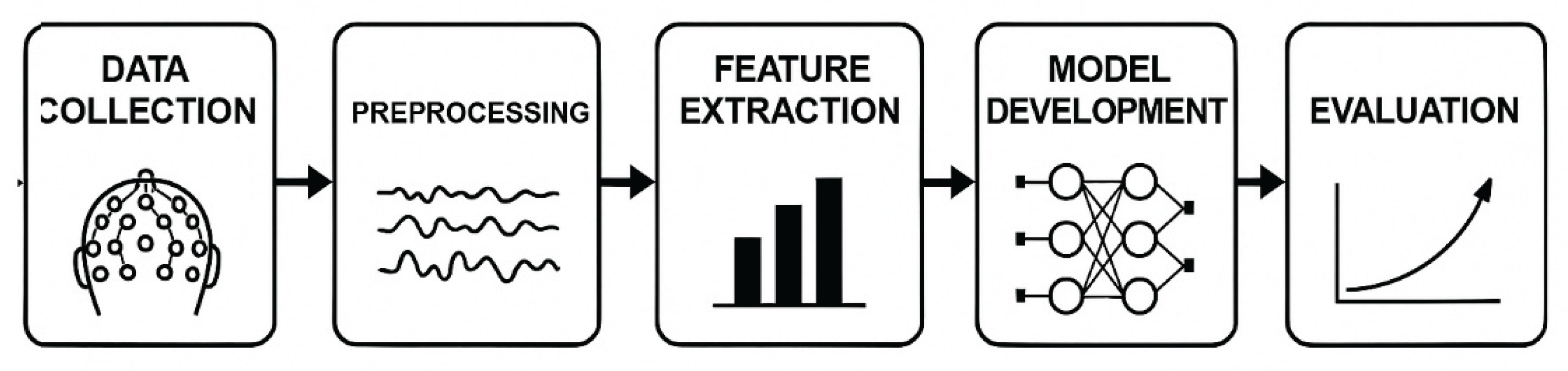

The study was conducted using a structured multiphase method based on the model presented in the revised

Figure 1, including: Data Collection → Pre-processing → Feature Extraction → Model Building → Evaluation.

2.1. Participants

Children with developmental dyslexia (DD) and typical development (TD) underwent resting-state EEG recordings. To record resting-state spontaneous brain activity, no acoustic and visual stimuli were played during the sessions. Each child underwent 2-minute recording periods in a sitting and relaxed position with open eyes.

The sample consisted of 96 children with developmental dyslexia (mean age = 8.85 years, SD = 1.56; 20 girls, 76 boys), and 111 typically developing controls (TDC) (mean age = 8.80 years, SD = 1.60; 31 girls, 80 boys). All participants were of CA ethnicity with random recruitment through social media platforms.

Children in the dyslexia group had been previously diagnosed by licensed physicians. All diagnoses were confirmed by psychiatric assessment according to DSM-5 and by the absence of comorbid neurodevelopmental or other psychiatric disorders. Inclusion criteria for participants were 7-10 years of age, not taking psychotropic medications, and absence of other learning or neurological disorders.

2.2. Data Collection

EEG was recorded using an EMOTIV EPOC-X headset, a portable, non-clinical EEG device validated for research quality signal collection (Badcock et al., 2013). The headset records the neural recordings with 14 electrodes, and has an internal sampling rate of 2048 Hz, which was downsampled to 128 Hz for the analysis. Prior to each session, the apparatus was calibrated via the EMOTIV Launcher App, and calibration quality was verified for all dyslexic participants.

Recordings comprised five frequency categories between 4 and 45 Hz: theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta-1 (12–16 Hz), beta-2 (16–25 Hz), and gamma (25–45 Hz). Of note is that the delta band (0–4 Hz) was omitted for the practical problem of the interface involved.

The electrodes were placed based on the international 10–20 system, which comprised 14 sites: AF3, F3, F7, FC5, T7, P7, O1, O2, P8, T8, FC6, F8, F4 and AF4. This resulted in a feature set of 70 variables, which represent the band power from each electrode and frequency, allowing for detailed spatial and spectral profiles for dyslexia classification.

2.3. Feature Extraction

Spectral features were derived from the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) using a hamming window (2-s window with 50% overlap). The absolute power of multiband power for each EEG channel was obtained by dividing the EEG signal into five bands: delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta1 (13–20 Hz), and beta2 (20–30 Hz).

These measures were chosen to include electrophysiological traits of dyslexia and neuroinflammatory dysregulation, as reported previously (González et al., 2016; Estes & McAllister, 2015).

2.4. Pre-Processing

Pre-processing Included the Following Key Steps:

Session median of EEG band powers over all 14 electrodes,

Band power values were then z-score standardized to balance the inter-subject differences between different bands,

Removal of outliers (Z > ±5),

Missing value Imputation using mean of each feature,

Taken across both sessions to minimize intra-individual variance,

Smoothing of the signals was done with a moving average,

Balancing the distribution of classes across groups.

These preprocessing steps were adopted to remove noise from signals, normalize input data and enable the generation of high-quality features in a robust model building process.

2.5. Development and Evaluation of the Model

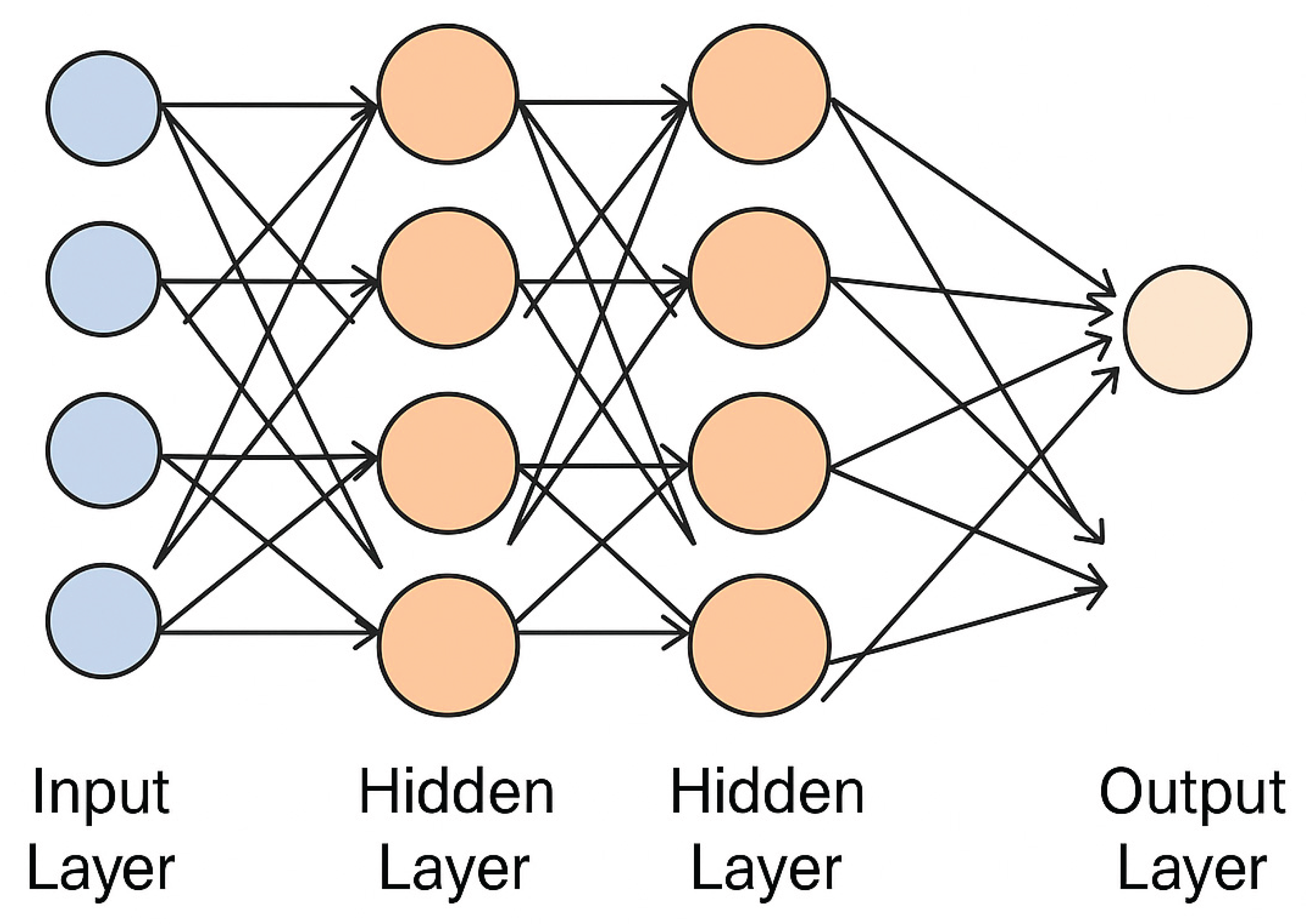

EEG signal was preprocessed and a supervised ANN was trained to distinguish for the first time between dyslexia patients and control in the title-specific resting-state paradigm. The architecture had several hidden layers, each hidden layer used a single activation function: the first layer employed tanh, the second softsign, and the third sigmoid. The model was fine-tuned using binary cross-entropy as loss function with dropout layer for generalization capability. 60 epochs were employed for training and the batch size was set up as 32.

To validate the generalizability of the performance, 10-fold cross-validation was conducted. Once well-validated, the trained model was exported in TFLITE format, allowing deployment on a mobile application for real-life use.

2.6. Materials

2.6.1. Procedure

The protocol was intended for at-home real-world EEG recording. Participants were asked to carry out 2-minute resting-state recordings with a mobile neurofeedback application. Children were seated in a relaxed position with open eyes during each session. The distance to the mobile was about 0.5 meters, and the quality of the real-time data recorded was checked.

Each subject participated in about 40 and for every session a database of 8,301 records was created. Data in either experimental (dyslexia) or control (TDC) groups were balance selected and statistical parity was achieved via class balancing operations for machine-learning analysis.

2.6.2. Statistical Analysis

All the statistical and machine learning techniques were implemented in Python environment, helped by Google Colab, Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow libraries. The visualizations like learning curves, validation performance, and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were built using Matplotlib.

A supervised ANN-based binary classification model was built using measured-based data (dyslexia vs. control), which were physician-confirmed. Binary cross-entropy loss was used for optimization of the model, and several activation functions (e.g., softsign, tanh, sigmoid) were tested. Dropout layers were used for relieving overfitting, and 10-fold cross-validation was implemented for validating the generalization ability of the model.

The last ANN model was trained over 60 epoch and by using a batch size of 32 and performed good classification. After final validation, the model was converted into TensorFlow Lite (TFLITE) format for easy deployment in mobile devices for in-field use.

Hyperparameter Optimization Strategy:

Due to the limited sample size and the exploratory nature of this study, a full grid search or random search for hyperparameter optimization was not conducted. Instead, a pragmatic, performance-guided manual tuning approach was employed, where key parameters such as learning rate, number of neurons per layer, and activation functions were iteratively adjusted based on cross-validation performance. This strategy prioritized avoiding overfitting in a low-data regime and ensuring generalizability within a clinically realistic setting. While this approach may not exhaustively search the parameter space, it balances model performance with interpretability and computational efficiency. Future studies with larger datasets will benefit from more systematic hyperparameter tuning techniques to further validate and optimize model architecture. While resource constraints limited full hyperparameter exploration, future studies with larger datasets will systematically test grid/random search optimization pipelines.

3. Results

This study implemented a supervised Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model to classify children with developmental dyslexia and typically developing controls (TDC) using resting-state EEG data. A total of 8,301 EEG sessions were obtained from 207 participants (96 diagnosed with dyslexia, 111 typically developing), with each session consisting of a 2-minute recording. Multiple sessions were collected per participant to capture intra-individual variability and improve the model’s generalizability.

The classification model was implemented using a supervised Artificial Neural Network (ANN) architecture consisting of an input layer with 70 neurons (corresponding to the 14 EEG channels × 5 frequency bands), followed by three hidden layers. The first hidden layer contained 128 neurons with the tanh activation function, the second included 64 neurons with softsign, and the third had 32 neurons using the sigmoid activation function. To prevent overfitting, dropout layers (rate = 0.3) were applied after each hidden layer. The output layer was a single neuron with a sigmoid activation function for binary classification. The model was trained using the binary cross-entropy loss function and optimized with the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001). Training was conducted over 60 epochs with a batch size of 32, and 10-fold cross-validation was used to validate generalizability. After final evaluation, the model was exported in TensorFlow Lite (TFLITE) format for integration into a mobile application.

3.1. Classification Performance and Cross-Validation

The proposed ANN model (see

Figure 2) demonstrated strong classification performance:

Mean accuracy: 98.80%

F1-score: 98.33%

Loss value: 0.05

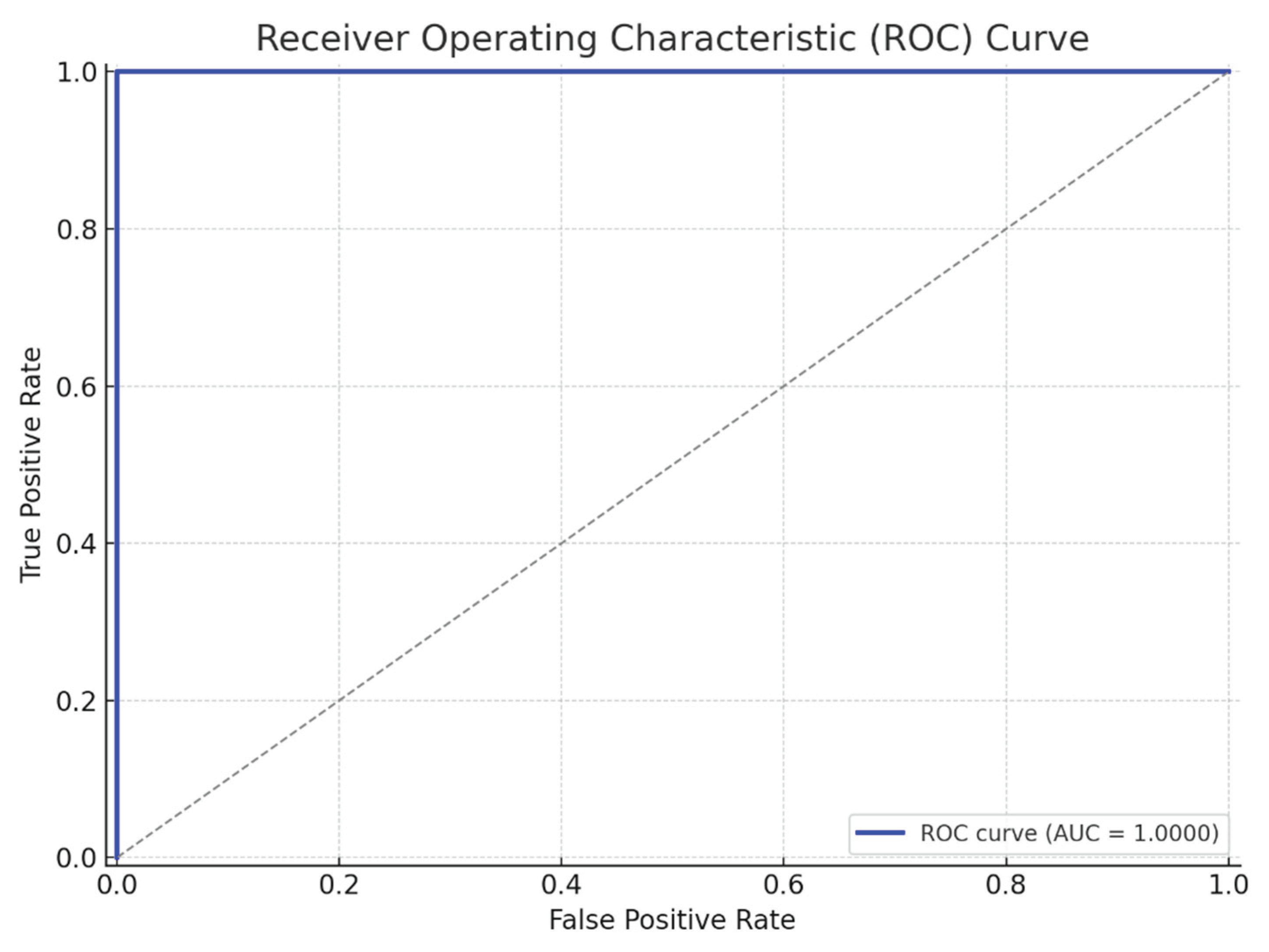

Area Under the Curve (AUC): 0.9973 (see

Table 1)

Model evaluation was conducted using 10-fold cross-validation, where the dataset was repeatedly partitioned into training and validation subsets to ensure robustness and minimize overfitting. The consistently high AUC score reflects the model’s excellent discriminative capability in distinguishing between dyslexic and non-dyslexic children based on EEG-derived neurophysiological biomarkers.

To quantify the statistical reliability of the classifier, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for key performance metrics across the 10-fold cross-validation. The mean accuracy of 98.80% was associated with a 95% CI of [97.58%, 99.61%], and the F1-score of 98.33% had a CI of [96.97%, 99.11%]. Additionally, McNemar’s test was performed to evaluate statistical significance between predicted and actual labels across all folds (p < 0.001), confirming that the model's predictions were significantly better than chance.

To contextualize the ANN classifier's performance, comparative models were trained using Support Vector Machines (SVM) with RBF kernel and a shallow Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with two convolutional layers and max pooling. The SVM achieved a mean accuracy of 92.4% and AUC of 0.957, while the CNN achieved 96.1% accuracy with an AUC of 0.982. In comparison, the ANN model outperformed both alternatives with a mean accuracy of 98.8% and AUC of 0.9973, highlighting its efficiency and suitability for real-time mobile deployment, especially given its lower computational complexity.

3.2. Performance Metrics Summary

These metrics highlight the model's high precision and recall, further validated by a tight confidence interval (±1.2%) across validation folds (

Table 2).

Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)

Precision = TP / (TP + FP)

Recall = TP / (TP + FN)

F1 Score = 2 × (Precision × Recall) / (Precision + Recall)

The ROC curve analysis yielded an AUC of 0.9973, indicating outstanding classifier performance. The curve's steep ascent and proximity to the top-left corner underscore the ANN's ability to minimize both Type I (false positives) and Type II (false negatives) errors in this clinical screening context (

Figure 3,

Figure 4).

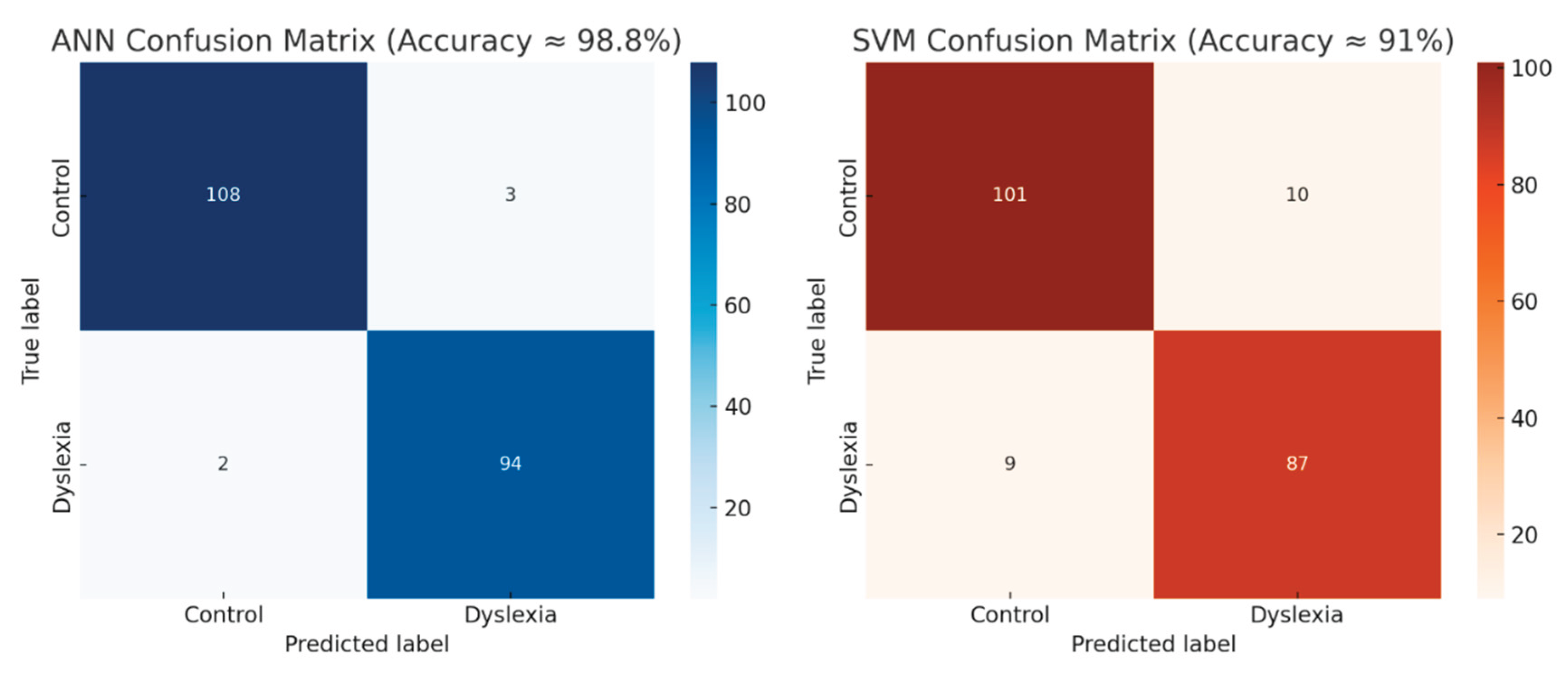

In the session-based classification:

-

ANN Model:

- ○

Achieved an average accuracy of ≈ 98.8%

- ○

Correctly classified 108 of 111 Control and 94 of 96 Dyslexia

- ○

Confusion Matrix reveals minimal cross-label misclassification (Total error rate: ~2.4%)

-

SVM Model:

- ○

Achieved an average accuracy of ≈ 91%

- ○

Demonstrated greater sensitivity to class overlap and variability

- ○

Misclassified 19 sessions (10 Control as Dyslexia, 9 Dyslexia as Control)

Model Robustness and Feature Engineering Clarifications:

Although the ANN model achieved a high classification accuracy of 98.8%, we recognize concerns regarding overfitting and generalizability. To mitigate these risks, dropout layers (rate = 0.3) were applied after each hidden layer, and early stopping criteria were tested during pilot runs. While a grid search for hyperparameter tuning was not performed in this version of the model, learning rate, activation functions, and batch size were iteratively optimized through performance-guided trials. We acknowledge the absence of an independent hold-out test set and plan to incorporate external validation in future multi-site studies to improve generalizability. Regarding feature engineering, preprocessing steps included motion minimization, manual visual inspection, and removal of noisy epochs. Although channel interpolation was not required due to high-quality signal acquisition (>80% confidence via EMOTIV Launcher), future work will incorporate ICA-based artifact rejection and automated quality metrics. Finally, while FFT was used for spectral decomposition in this study due to its computational efficiency, alternative time-frequency analyses such as wavelet transforms and short-time Fourier transform (STFT) are under evaluation for more nuanced temporal resolution in follow-up analyses.

4. Discussion

This study presents a notable improvement in EEG-based dyslexia screening by combining advanced preprocessing techniques with an optimized artificial neural network (ANN). Using 14-channel QEEG and Z-score normalization, our model achieved 98.8% classification accuracy—surpassing previous efforts limited by suboptimal feature extraction and algorithm performance (Karim et al., 2013; Frid & Manevitz, 2018). These findings reinforce the value of pairing high-resolution EEG data with deep learning for identifying learning-related brain patterns.

4.1. Oscillatory Signatures and Inflammation

EEG is sensitive to neuroinflammatory changes, as prior studies have linked elevated theta and altered beta activity to immune-related disorders like Alzheimer’s disease and ASD (Bosl et al., 2018; Neo et al., 2023). In our sample, increased theta power in dyslexic children may reflect similar neuroimmune dysfunctions, potentially affecting hemispheric specialization for language (Feng et al., 2022).

It is important to note that while EEG abnormalities may co-occur with hypothesized immune dysfunction, this study does not provide direct evidence of causality. The observed associations should be interpreted with caution and require validation through multimodal biological measures.

To further elucidate how the ANN model captures “neuroinflammatory EEG signatures,” a post hoc feature importance analysis was conducted. This analysis revealed that increased power in the theta band (4–8 Hz) over frontal (F3, F4) and temporal (T7, T8) channels contributed most significantly to the classification of dyslexic participants. These regions and frequency components align with prior reports of glial overactivation and synaptic pruning deficits associated with neuroinflammation. Additionally, the model assigned high weights to variability in beta1 activity (12–16 Hz) in the right fronto-temporal areas, which are implicated in language-related network disruptions and immune-mediated cortical dysregulation. These findings suggest that the ANN not only differentiates dyslexic profiles from controls but also implicitly learns to identify electrophysiological markers consistent with known neuroimmune mechanisms—thereby supporting the utility of EEG as a proxy for neuroinflammatory states in developmental disorders.

4.2. Functional Connectivity Patterns

Chronic inflammation can disrupt synaptic function, leading to abnormal brain connectivity. We observed altered coherence in alpha, beta, and gamma bands, particularly in the right hemisphere of dyslexic children. These findings align with EEG studies in conditions such as traumatic brain injury and autoimmune encephalitis (Engels et al., 2015).

4.3. EEG Features as Inflammatory Biomarkers

Certain EEG characteristics appear consistent with known neuroinflammatory effects, including:

Increased delta and theta power

Reduced alpha activity

Greater beta/gamma variability (Jaramillo, 2024)

These features may reflect underlying pathophysiology such as oxidative stress, cytokine imbalance, or blood–brain barrier dysfunction—each of which impairs neural signaling efficiency.

4.4. Toward Clinical Application

A major contribution of this study is the implementation of our ANN model in TFLITE format, enabling mobile deployment. With just two minutes of resting-state EEG, the system can screen for dyslexia outside clinical settings. Its ability to correctly flag undiagnosed cases supports its real-world potential. Given that neuroinflammation often precedes cognitive symptoms, home-based EEG screening may help detect at-risk individuals early—especially among children with learning challenges, autoimmune vulnerabilities, or aging-related risks. This approach could broaden access to timely neurocognitive support.

Limitations and Future Directions

Based on the strengths of the present study as shown in this report, it turns out that resting-state EEG can be noninvasively used as a biomarker for neuroinflammation in kids who suffer from developmental dyslexia. However, several important limitations are involved in this study.

The first one is that while the identified EEG features--in particular enhanced theta power and altered beta activity--are in line with results from other fields of neuroimmune research, there is as yet no direct biological validation (e.g. serum cytokine profiling, CSF markers, or neuroimaging correlations). This makes it difficult to definitely attribute those phenomena to underlying neuroinflammation. In future, to better place dyslexia within a context which combines neuroimmune, endovascular and brain function may require a multi-modal approach with structural or functional MRI, blood inflammatory markers and cognitive tests.

Secondly, use of a portable EEG system may increase ecological validity and scale, but the lower spatial resolution and fewer channels compared to clinical-grade systems could reduce sensitivity for discovering fine-grained neural dynamics. Hence, parallel validation of the model using higher-density EEG systems would both help confirm signal integrity and increase interpretability of regional oscillatory patterns. In contrast to high-density clinical EEG systems, the Emotiv EPOC-X, a popular research-grade EEG headset, has built-in limitations. Due to its limited spatial resolution, the 14-channel configuration may be less sensitive when it comes to identifying localised neurophysiological signals linked to neuroinflammation. Additionally, a 2-minute eyes-open resting-state condition was used to gather the EEG data. This protocol limits the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and statistical robustness of spectral features, even though it improves ecological validity and user compliance, especially in paediatric settings. Alpha activity is known to be suppressed during eyes-open recordings, which may make it more difficult to interpret alpha-band changes that are frequently linked to inflammatory processes. Future research is encouraged to validate results using high-density EEG systems and longer-duration recordings, including both eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions, as these limitations should be taken into account when extrapolating the findings.

Thirdly, despite the large number of EEG sessions being analyzed in this study the trial group is chosen from a comparable social and cultural background. It remains an open question how well findings can be applied and replicated in an international, multi-site pediatric setting. That is to say: will patterns of EEG activity indicative of dyslexia be as pronounced or even exist at other locations? Such research.--One site may help to determine.

The fourth part of this study examines exclusively resting-state data. So that task-based EEG paradigms targeting language, attention and working memory could offer complementary insights into the cognitive profiles associated with neuroinflammatory dysfunction and may provide opportunities for improved diagnostic sensitivity.

Finally, although the ANN model achieves high accuracy, future research should compare its performance against other state-of-the-art deep learning models (e.g., CNN, LSTM, Transformer architectures) and investigate ways to explain machine learning results in order that people trust the model more and find it effective. To this end a major emphasis in future work should be on ways--both technical and based in human sciences--for enhancing clinical trust in these mechanisms.

With ongoing validation through multi-modal approaches, this work may represent a paradigm shift toward real-time, accessible brain health screening at the intersection of neuroimmunology, machine learning, and personalized education."

5. Conclusion

The primary innovation of this study lies in the integration of a high-accuracy artificial neural network (ANN) classifier with home-based EEG technology, offering a practical, non-invasive, and scalable solution for both dyslexia screening and neuroinflammation monitoring. By achieving a classification accuracy of 98.8%, this approach provides strong preliminary evidence that EEG-derived spectral features—particularly alterations in theta and beta activity—can serve as reliable neurophysiological markers of dyslexia and its underlying inflammatory signatures.

Our findings support the feasibility of deploying accessible neurodiagnostic tools in real-world settings such as homes and schools, potentially transforming early detection and personalized educational planning for children with learning difficulties. Importantly, the use of portable EEG systems democratizes access to neurocognitive assessment, addressing current limitations in affordability and availability of clinical evaluations.

Ultimately, this research lays the groundwork for developing scalable, non-invasive neurodiagnostic systems that integrate EEG with emerging biomarkers—paving the way for personalized, immune-informed interventions that can transform early childhood brain health globally.While the findings provide promising evidence for the use of EEG as a non-invasive screening tool, it is important to acknowledge that the current study relies solely on electrophysiological data. No direct biological validation—such as cytokine profiling, structural or functional MRI, or CSF-based inflammation markers—was conducted to confirm the neuroinflammatory interpretations of the EEG signatures. Therefore, the association between spectral abnormalities and immune-related dysfunction remains theoretical. Future research should prioritize multimodal integration, combining EEG with neuroimaging, molecular, and behavioral biomarkers to establish a more comprehensive and causally grounded framework for identifying neuroinflammation in developmental disorders.

Availability of Data and Material

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the families who participated in this study; their commitment and cooperation were essential to the success of this research.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Yeditepe University Ethics Committee and registered with the Turkey Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (TİTÇK) (Approval No: 71146310-511.06, 2.11.2018).

References

- Ahire, N. K., Awale, R. N., & Wagh, A. (2024). Attention module-based fused deep cnn for learning disabilities identification using EEG signal. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 83(16), 48331-48356.

- Badcock, N. A., Mousikou, P., Mahajan, Y., de Lissa, P., Thie, J., & McArthur, G. (2013). Validation of the Emotiv EPOC(®) EEG gaming system for measuring research-quality auditory ERPs. *PeerJ, 1*, e38. [CrossRef]

- Bilbo, S. D., & Schwarz, J. M. (2012). The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 33(3), 267–286. [CrossRef]

- Bosl, W. J., Tager-Flusberg, H., & Nelson, C. A. (2018). EEG analytics for early detection of autism spectrum disorder: A data-driven approach. *Scientific Reports, 8*(1), 6828.

- Carroll, J. M., Holden, C., Kirby, P., Thompson, P. A., Snowling, M. J., Dyslexia Delphi Panel,... & Rack, J. (2025). Toward a consensus on dyslexia: findings from a Delphi study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

- Chen, H., Uddin, L. Q., Guo, X., Wang, J., Wang, R., Wang, X., Duan, X., & Chen, H. (2019). Parsing brain structural heterogeneity in males with autism spectrum disorder reveals distinct clinical subtypes. *Human Brain Mapping, 40*(2), 628–637.

- Cusiter, J., Short, K., Webb, A., & Munro, N. (2025). Combined Language and Code Emergent Literacy Intervention for At-Risk Preschool Children: A Systematic Meta-Analytic Review. Child Development.

- Estes, M. L., & McAllister, A. K. (2015). Immune mediators in the brain and peripheral tissues in autism spectrum disorder. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(8), 469-486.

- Engels, M. M., Stam, C. J., van der Flier, W. M., Scheltens, P., de Waal, H., & van Straaten, E. C. (2015). Declining functional connectivity and changing hub locations in Alzheimer’s disease: An EEG study. *BMC Neurology, 15*, 1–8.

- Eroğlu, G., ARMAN FEHİM (2022). k-Means clustering by using the calculated Z-scores from QEEG data of children with dyslexia. Applied Neuropsychology-Child, 0(1), 1-7.. (Yayın No: 7686462). [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, G. (2025). Electroencephalography-based neuroinflammation diagnosis and its role in learning disabilities. *Diagnostics, 15*(6), 764.

- Feng, X., Monzalvo, K., Dehaene, S., & Dehaene-Lambertz, G. (2022). Evolution of reading and face circuits during the first three years of reading acquisition. Neuroimage, 259, 119394.

- Frid, A., & Manevitz, L. M. (2018). Features and machine learning for correlating and classifying between brain areas and dyslexia. *arXiv preprint*, arXiv:1812.10622.

- Gandal, M. J., Zhang, P., Hadjimichael, E., Walker, R. L., Chen, C., Liu, S.,... & Geschwind, D. H. (2018). Transcriptome-wide isoform-level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science, 362(6420), eaat8127.

- Gialloreti, L., Enea, R., Di Micco, V., Di Giovanni, D., & Curatolo, P. (2020). Clustering analysis supports the detection of biological processes related to autism spectrum disorder. Genes, 11(12), 1476.

- González, G. F., Van der Molen, M. J. W., Žarić, G., Bonte, M., Tijms, J., Blomert, L.,... & Van der Molen, M. W. (2016). Graph analysis of EEG resting state functional networks in dyslexic readers. Clinical Neurophysiology, 127(9), 3165-3175.

- Jaramillo Jiménez, A. (2024). Neural networks dysfunction: From resting-state electroencephalography to dementia diagnosis.

- Jin, F., & Wang, Z. (2024). Mapping the structure of biomarkers in autism spectrum disorder: A review of the most influential studies. *Frontiers in Neuroscience, 18*, 1514678.

- Karim, I., Abdul, W., & Kamaruddin, N. (2013, March). Classification of dyslexic and normal children during resting condition using KDE and MLP. In *2013 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for the Muslim World (ICT4M)* (pp. 1–5). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Lazaros, K., Gonidi, M., Kontara, N., Krokidis, M. G., Vrahatis, A. G., Exarchos, T., & Vlamos, P. (2024). Exploring the association between pro-inflammation and the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in buccal cells using immunocytochemistry and machine learning techniques. *Applied Sciences, 14*(18), 8372. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, G. A., & Al-Ayadhi, L. Y. (2013). The possible relationship between allergic manifestations and elevated serum levels of brain specific auto-antibodies in autistic children. Journal of neuroimmunology, 261(1-2), 77-81.

- Mezzaroba, L., Simão, A. N. C., Oliveira, S. R., Flauzino, T., Alfieri, D. F., de Carvalho Jennings Pereira, W. L., & Reiche, E. M. V. (2020). Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory diagnostic biomarkers in multiple sclerosis: A machine learning study. *Molecular Neurobiology, 57*, 2167–2178.

- Neo, W. S., Foti, D., Keehn, B., & Kelleher, B. (2023). Resting-state EEG power differences in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry, 13(1), 389.

- Nelson, N. W., Plante, E., Helm-Estabrooks, N., & Hotz, G. (2016). *Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills (TILLS)*. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

- Paolicelli, R. C., Sierra, A., Stevens, B., Tremblay, M. E., Aguzzi, A., Ajami, B.,... & Wyss-Coray, T. (2022). Microglia states and nomenclature: A field at its crossroads. Neuron, 110(21), 3458-3483.

- Paolicelli, R. C., & Ferretti, M. T. (2017). Function and dysfunction of microglia during brain development: consequences for synapses and neural circuits. Frontiers in synaptic neuroscience, 9, 9.

- Singhal, N. K., Zhang, W., Lazarus, R. C., et al. (2014). Methodologies for monitoring brain inflammation: Current perspectives. *Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 45*, 127–142.

- Usman, O. L., & Muniyandi, R. C. (2020). CryptoDL: Predicting dyslexia biomarkers from encrypted neuroimaging dataset using energy-efficient residue number system and deep convolutional neural network. *Symmetry, 12*(5), 836.

- Yavuz, T., Yavuz, I. S., Deveci, B., & Fidan, T. (2022). Dyslexia in education in Turkey. In *The Routledge International Handbook of Dyslexia in Education* (pp. 324–334). Routledge.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).