Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of S-DNTT-10 Thin-Films

2.2. Fabrication of gold (Au) Nanostructures

3. Results and Discussion

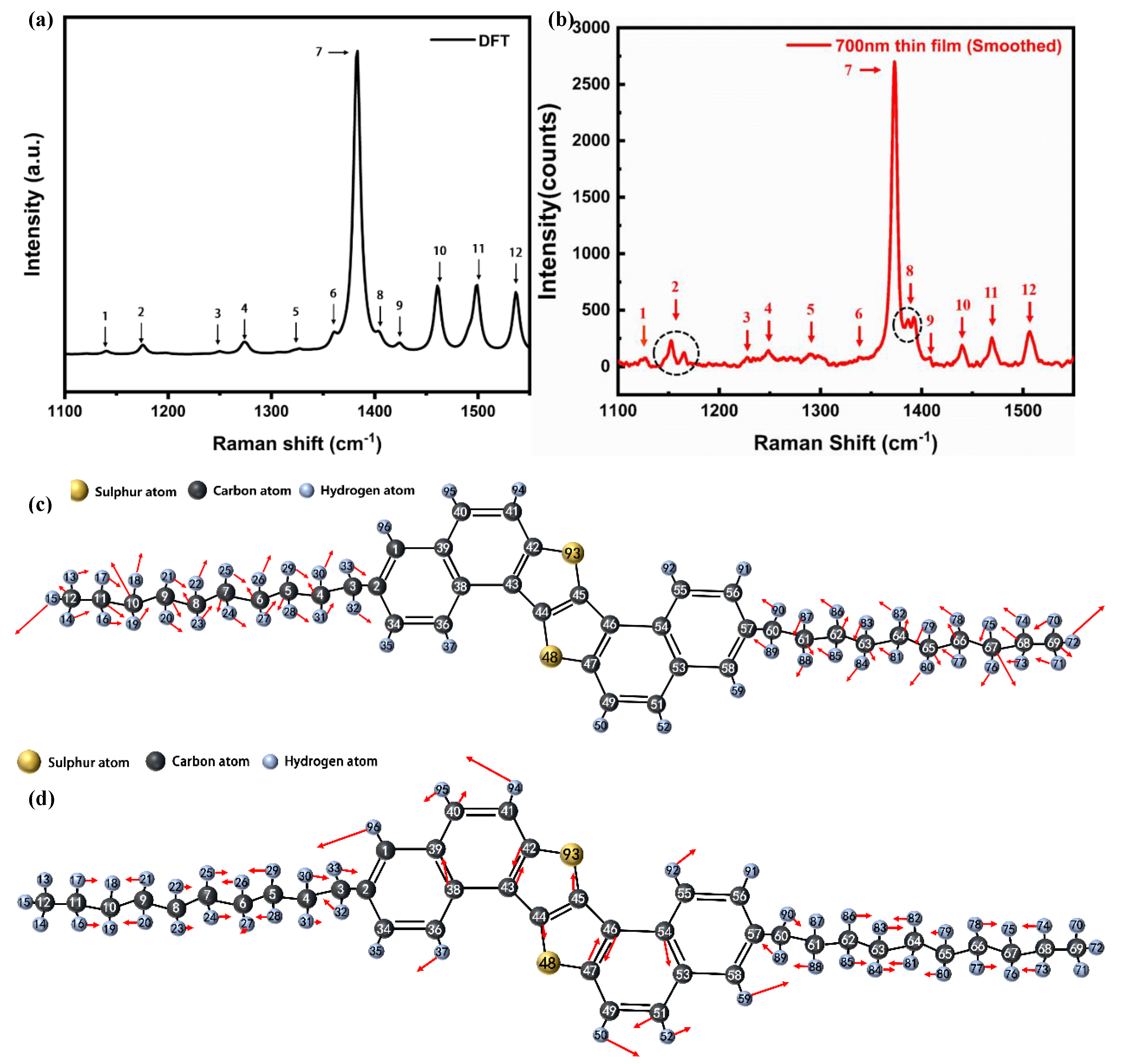

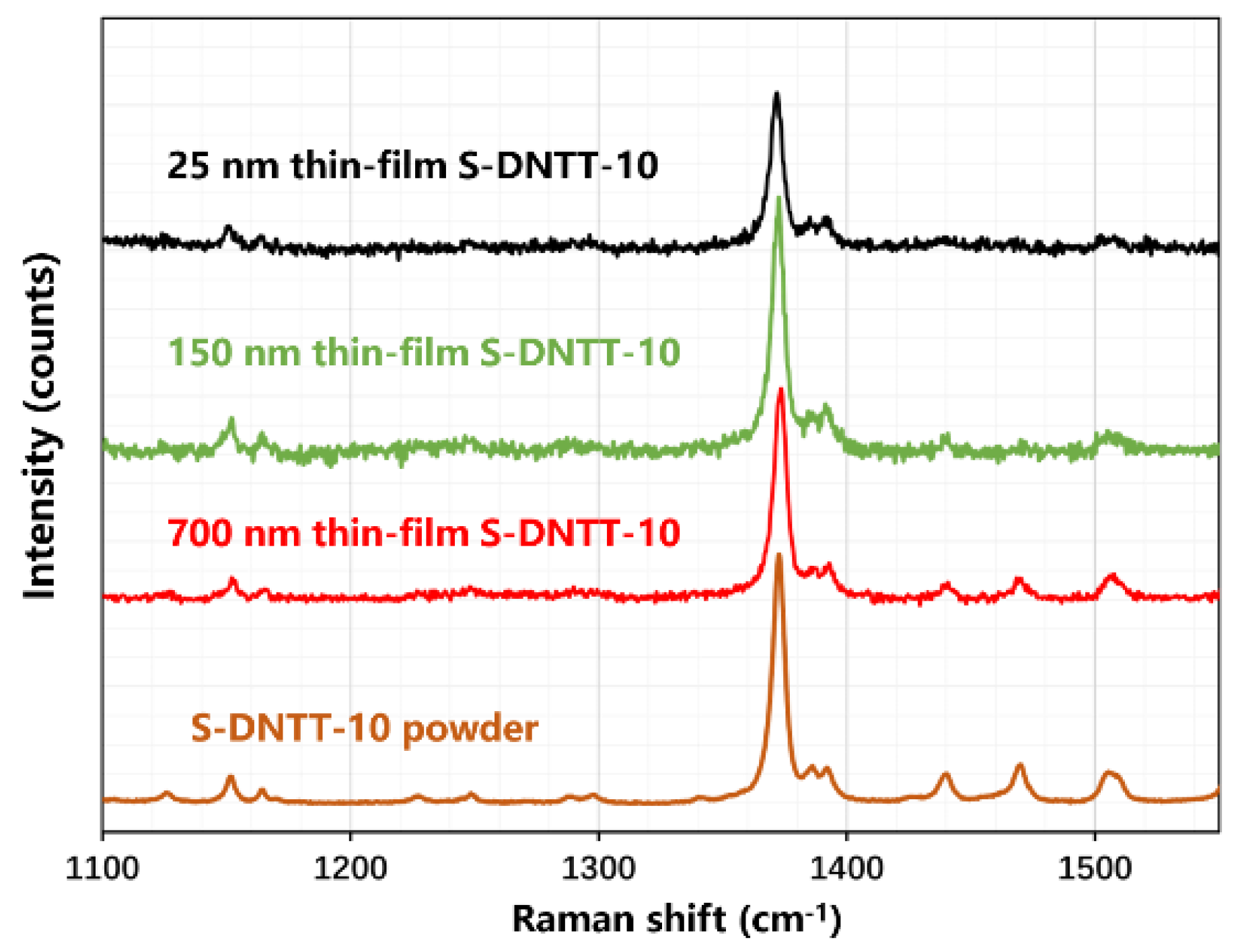

3.1. Theoretical Calculation and Measured Raman Spectrum

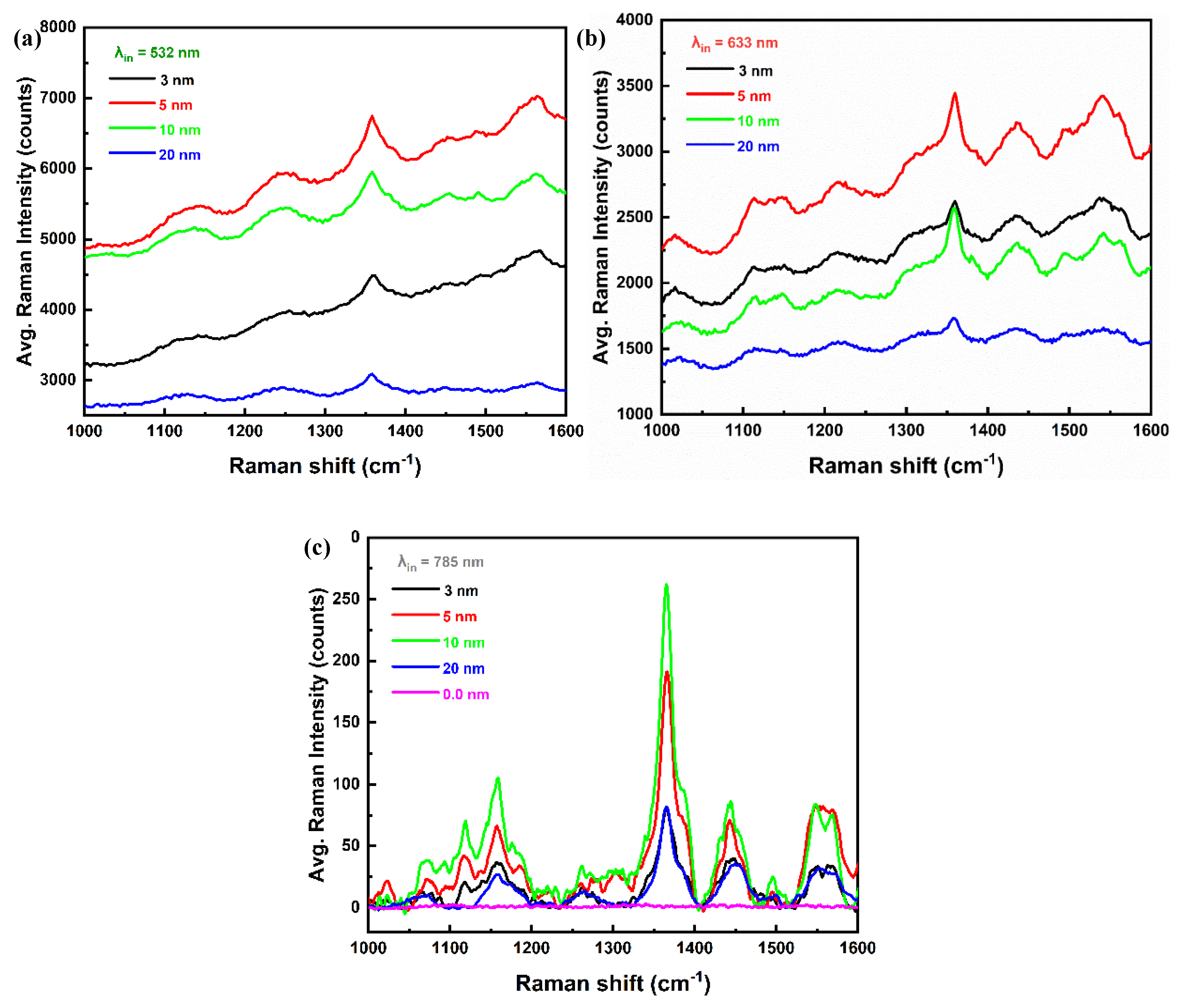

3.2. The SERS Effect on S-DNTT-10 Thin-Film

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, Y.H.; Jang, M.; Lee, M.Y.; Kweon, O.Y.; Oh, J.H. Flexible Field-Effect Transistor-Type Sensors Based on Conjugated Molecules. Chem 2017, 3, 724–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torikai, K.; Furlan de Oliveira, R.; Starnini de Camargo, D.H.; Bof Bufon, C.C. Low-Voltage, Flexible, and Self-Encapsulated Ultracompact Organic Thin-Film Transistors Based on Nanomembranes. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 5552–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T. Next-Generation Organic Semiconductors Driven by Bent-Shaped π-Electron Cores. Polym J 2019, 51, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrip, M.; Jurchescu, O.D.; Gundlach, D.J.; Bittle, E.G. Contact Resistance in Organic Field-Effect Transistors: Conquering the Barrier. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1904576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-H. Contact Resistance in Organic Transistors: Use It or Remove It. Applied Physics Reviews 2020, 7, 031306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Jiménez-Tejada, J.A.; González, J.; Deen, M.J. Unified Electrical Model for the Contact Regions of Staggered Thin Film Transistors. Organic Electronics 2021, 92, 106129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, T.; Sarma, R. Performance Enhancement of Top Contact Pentacene-Based Organic Thin-Film Transistor (OTFT) Using Perylene Interlayer between Organic/Electrode Interface. Appl. Phys. A 2017, 123, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamport, Z.A.; Barth, K.J.; Lee, H.; Gann, E.; Engmann, S.; Chen, H.; Guthold, M.; McCulloch, I.; Anthony, J.E.; Richter, L.J.; DeLongchamp, D.M.; Jurchescu, O.D. A Simple and Robust Approach to Reducing Contact Resistance in Organic Transistors. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, F.; Din, N. Design and Performance Investigation of Short Channel Bottom-Contact Organic Thin-Film Transistors. J Comput Electron 2018, 17, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, O.; Giraudet, L. Transport Models in Disordered Organic Semiconductors and Their Application to the Simulation of Thin-film Transistors. Polym. Int. 2019, 68, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchert, J.W.; Weitz, R.T.; Ludwigs, S.; Klauk, H. A Critical Outlook for the Pursuit of Lower Contact Resistance in Organic Transistors. Advanced Materials 2022, 34, 2104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Park, Y.; Jang, Y.; Yang, H.; Kim, Y.; Han, J.; Moon, D.; Park, S.; Chang, T.; Chang, C. Enhancement of Field-Effect Mobility Due to Surface-Mediated Molecular Ordering in Regioregular Polythiophene Thin Film Transistors. Advanced Functional Materials 2005, 15, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wang; Qijing; Jiang; Sai; Qiu; Longbin; Qian; Jun; Ono; Luis. Interfacial Flat-Lying Molecular Monolayers for Performance Enhancement in Organic Field-Effect Transistors. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018.

- Iwasawa, K.; Okudaira, K.K. Effect of Chemical Interaction at Modification Layer/Substrate Interface on Molecular Orientation of Dinaphtho[2,3- b :2′,3′- f ]Thieno[3,2- b ]Thiophene Thin Films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 59, 091004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, B.; Sugiyama, T.; Namba, N.; Umakoshi, T.; Uemura, T.; Sekitani, T.; Verma, P. Raman Spectroscopic Studies of Dinaphthothienothiophene (DNTT). Materials 2019, 12, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, H.E.; Bao, Z.; Gilat, S.L. Synthetic Chemistry for Ultrapure, Processable, and High-Mobility Organic Transistor Semiconductors. Accounts of Chemical Research 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, J.E. Functionalized Acene & Heteroacene for Organic Electronics. 2006.

- Benor, A.; Hoppe, A.; Wagner, V.; Knipp, D. Electrical Stability of Pentacene Thin Film Transistors. Organic Electronics 2007, 8, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchetti, A. Semiconductors for Organic Transistors. Materials Today 2007, 10, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.; Lehmann, D.; Müller, A.-D.; Müller, F.; Zahn, D.R.T. Potentiometry on Pentacene OFETs: Charge Carrier Mobilities and Injection Barriers in Bottom and Top Contact Configurations. phys. stat. sol. (a) 2008, 205, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Takimiya, K. Facile Synthesis of Highly Pi-Extended Heteroarenes, Dinaphtho[2,3-B : 2 ’,3 ’-f]Chalcogenopheno[3,2-b]Chalcogenophenes, and Their Application to Field-Effect Transistors. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2007, 129, 2224–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschieschang, U.; Ante, F.; Kälblein, D.; Yamamoto, T.; Takimiya, K.; Kuwabara, H.; Ikeda, M.; Sekitani, T.; Someya, T.; Nimoth, J.B.; Klauk, H. Dinaphtho[2,3-b:2′,3′-f]Thieno[3,2-b]Thiophene (DNTT) Thin-Film Transistors with Improved Performance and Stability. Organic Electronics 2011, 12, 1370–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, U.; Takimiya, K.; Kang, M.J.; Rödel, R.; Letzkus, F.; Burghartz, J.N.; Weber, E.; Klauk, H. Detailed Analysis and Contact Properties of Low-Voltage Organic Thin-Film Transistors Based on Dinaphtho[2,3-b:2′,3′-f]Thieno[3,2-b]Thiophene (DNTT) and Its Didecyl and Diphenyl Derivatives. Organic Electronics 2016, 35, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Za’aba, N.K.; Taylor, D.M. Bias and Related Stress Effects in Organic Thin Film Transistors Based on Dinaphtho [2,3-b:2′,3′-f] Thieno[3,2-b] Thiophene (DNTT). Organic Electronics 2018, 62, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, R.; Günder, D.; Breuer, T.; Schmitz, G.; Klauk, H.; Witte, G. Stability of Organic Thin-Film Transistors Based on Ultrathin Films of Dinaphtho[2,3- b :2′,3′- f ]Thieno[3,2- b ]Thiophene (DNTT). J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-P.; Qin, G.-Y.; Guo, J.-F.; Zhang, B.-H.; Li, H.-Y.; Zou, L.-Y.; Ren, A.-M. Unveiling the Effects of Substituents on the Packing Motif and the Carrier Transport of Dinaphtho-Thieno-Thiophene (DNTT)-Based Materials. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 11552–11565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becharguia, H.; Mahdouani, M.; Bourguiga, R.; Branchini, P.; Fabbri, A.; De Rosa, S.; Calvi, S.; Mariucci, L.; Valletta, A.; Tortora, L. Effects of Illumination on the Electrical Characteristics in Organic Thin-Film Transistors Based on Dinaphtho [2,3-b:2′,3′-f] Thieno[3,2-b] Thiophene (DNTT): Experiment and Modeling. Synthetic Metals 2022, 283, 116985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

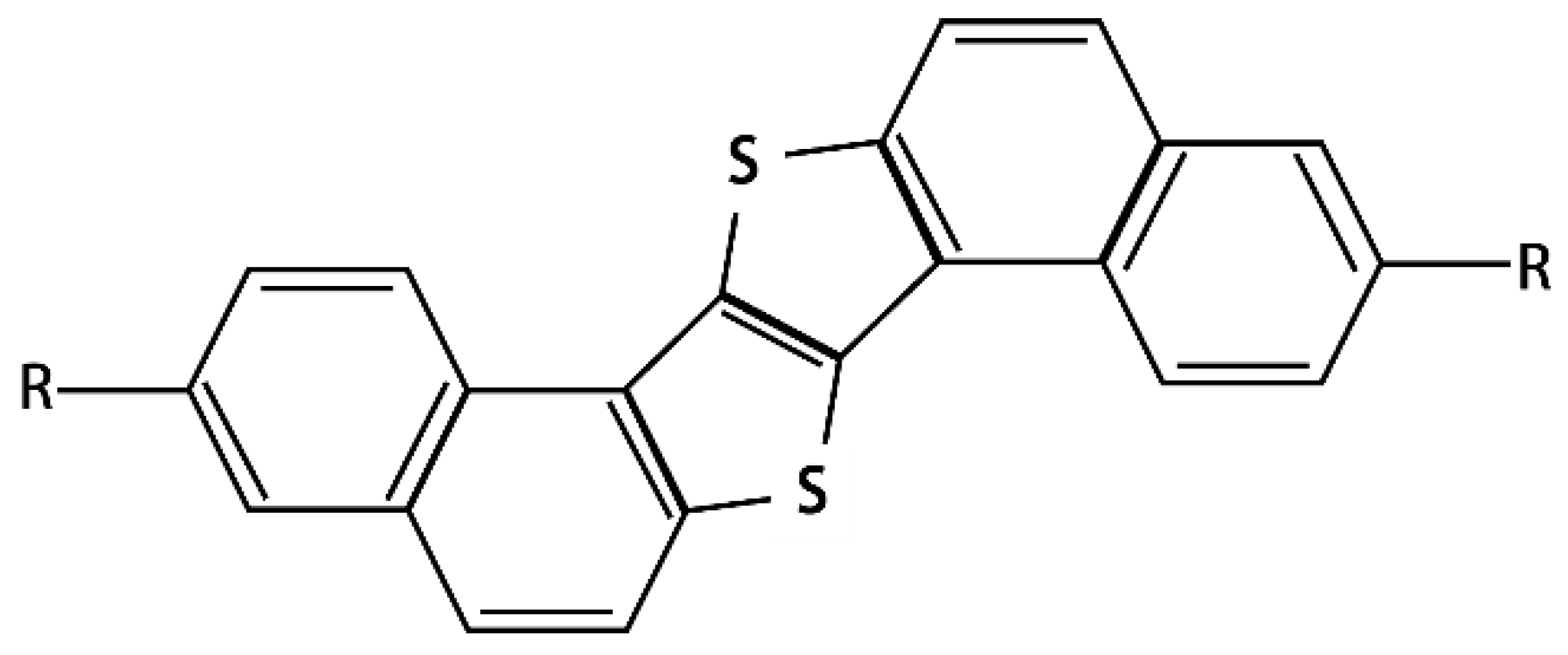

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Kojiguchi, Y.; Kawata, S.; Mori, T.; Okamoto, K.; Tsutsui, M.; Koganezawa, T.; Katagiri, H.; Yasuda, T. Solution-Processable Organic Semiconductors Featuring S-Shaped Dinaphthothienothiophene (S-DNTT): Effects of Alkyl Chain Length on Self-Organization and Carrier Transport Properties. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 5350–5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-L. Mai, Y. -S.; Chou, W. -Y.; Chang, L. -R.; Liang, X. -W. Thickness-Dependent Structural Evolutions and Growth Models in Relation to Carrier Transport Properties in Polycrystalline Pentacene Thin Films. Adv Funct Materials 2007, 17, 3639–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, B.; Sugiyama, T.; Namba, N.; Umakoshi, T.; Uemura, T.; Sekitani, T.; Verma, P. Raman Spectroscopic Studies of Dinaphthothienothiophene (DNTT). Materials 2019, 12, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, D.; Guha, S. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopic Studies of the Au-Pentacene Interface: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigation. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2013, 139, 044715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, T.J.; Sirringhaus, H. Analysis of the Contact Resistance in Staggered, Top-Gate Organic Field-Effect Transistors. Journal of Applied Physics 2007, 102, 094510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ou-Yang, W.; Weis, M. Electric-Field Enhanced Thermionic Emission Model for Carrier Injection Mechanism of Organic Field-Effect Transistors: Understanding of Contact Resistance. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 035101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, B.; Shin, E.-Y.; Noh, Y.-Y.; Xu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y. Role of Schottky Barrier and Access Resistance in Organic Field-Effect Transistors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Frontiera, R.R.; Henry, A.-I.; Ringe, E.; Van Duyne, R.P. SERS: Materials, Applications, and the Future. Materials Today 2012, 15, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.S.; Ozaki, Y.; Itoh, T. Recent Progress and Frontiers in the Electromagnetic Mechanism of Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews 2014, 21, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilot; Signorini; Durante; Orian; Bhamidipati; Fabris. A Review on Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Biosensors 2019, 9, 57. [CrossRef]

- Langer, J.; Jimenez de Aberasturi, D.; Aizpurua, J.; Alvarez-Puebla, R.A.; Auguié, B.; Baumberg, J.J.; Bazan, G.C.; Bell, S.E.J.; Boisen, A.; Brolo, A.G.; Choo, J.; Cialla-May, D.; Deckert, V.; Fabris, L.; Faulds, K.; García de Abajo, F.J.; Goodacre, R.; Graham, D.; Haes, A.J.; Haynes, C.L.; Huck, C.; Itoh, T.; Käll, M.; Kneipp, J.; Kotov, N.A.; Kuang, H.; Le Ru, E.C.; Lee, H.K.; Li, J.-F.; Ling, X.Y.; Maier, S.A.; Mayerhöfer, T.; Moskovits, M.; Murakoshi, K.; Nam, J.-M.; Nie, S.; Ozaki, Y.; Pastoriza-Santos, I.; Perez-Juste, J.; Popp, J.; Pucci, A.; Reich, S.; Ren, B.; Schatz, G.C.; Shegai, T.; Schlücker, S.; Tay, L.-L.; Thomas, K.G.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Van Duyne, R.P.; Vo-Dinh, T.; Wang, Y.; Willets, K.A.; Xu, C.; Xu, H.; Xu, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.S.; Zhao, B.; Liz-Marzán, L.M. Present and Future of Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 28–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, C.; Shou, M.; Lin, Y.; Hou, X.; Xie, Z.; Liu, L. Introducing a Surface-Enhanced-Raman-Scattering Enhancer for Experimental Estimation of the Debye Screening Length in Organic Field-Effect Transistors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 1920–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, D.; Guha, S. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopic Studies of Metal–Semiconductor Interfaces in Organic Field-Effect Transistors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 12779–12785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoch, S.; Bonod, N. Plasmonics: From Basics to Advanced Topics; Springer, 2012; Vol. 167.

- Neamen, D.A.; Biswas, D. Semiconductor Physics and Devices; McGraw-Hill higher education New York, 2011.

| Mode | Raman shift/cm-1 | Vibrational modes descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1141.79 | C-H bond bending at alkyl chains |

| 2 | 1177.11 | C-H bond bending located at the aromatic rings and coupled with few slight deformations of thiophene rings |

| 3 | 1251.53 | C-H bond bending at alkyl chains; C-H bond bending coupled with slight breathing stretching aromatic rings and thiophene rings deformed |

| 4 | 1274.84 | C-H bond bending at alkyl chains; some serious C-H bond bending located at C(38), C(33), C(93), C(86), C(81) and C(45), and coupled with few slight deformation of aromatic and thiophene rings |

| 5 | 1328.95 | C-H bond anti-symmetry bending at alkyl chains coupled with C-C bond movement at aromatic and thiophene rings |

| 6 | 1362.20 | C-H bond bending at alkyl chains; deformation of thiophene rings and linked aromatic rings; seriously C-H bond bending located at C(36), C(95), C(84) and C(47); C-C bond stretched at aromatic and thiophene rings |

| 7 | 1384.79 | C-H bond slightly bending at alkyl chains; strongly C-H bond bending located at C(38), C(33), C(86) and C(81) coupled with deformation of aromatic and thiophene |

| 8 | 1406.24 | C-H bond slightly bending at alkyl chains; strongly C-H bond bending located at C(36), C(93), C(84) and C(85) and C(42)=C(90) double-bond stretching coupled with deformation of aromatic and thiophene |

| 9 | 1426.09 | slight C-H bond bending at the end of alkyl chains; strong C-H bond bending at C(36), C(33), C(95), C(86), C(81) and C(47) coupled with deformation of aromatic and thiophene rings. |

| 10 | 1462.96 | C(42)-C(43) and C(90)-C(91) strongly stretching coupled with deformation of aromatic and thiophene rings |

| 11 | 1500.85 | C-H slightly bending at the end of alkyl chains; deformation of aromatic and thiophene rings |

| 12 | 1539.00 | strongly C(42) = C(90) double-bond stretching coupled with deformation of aromatic and thiophene rings |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).