Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

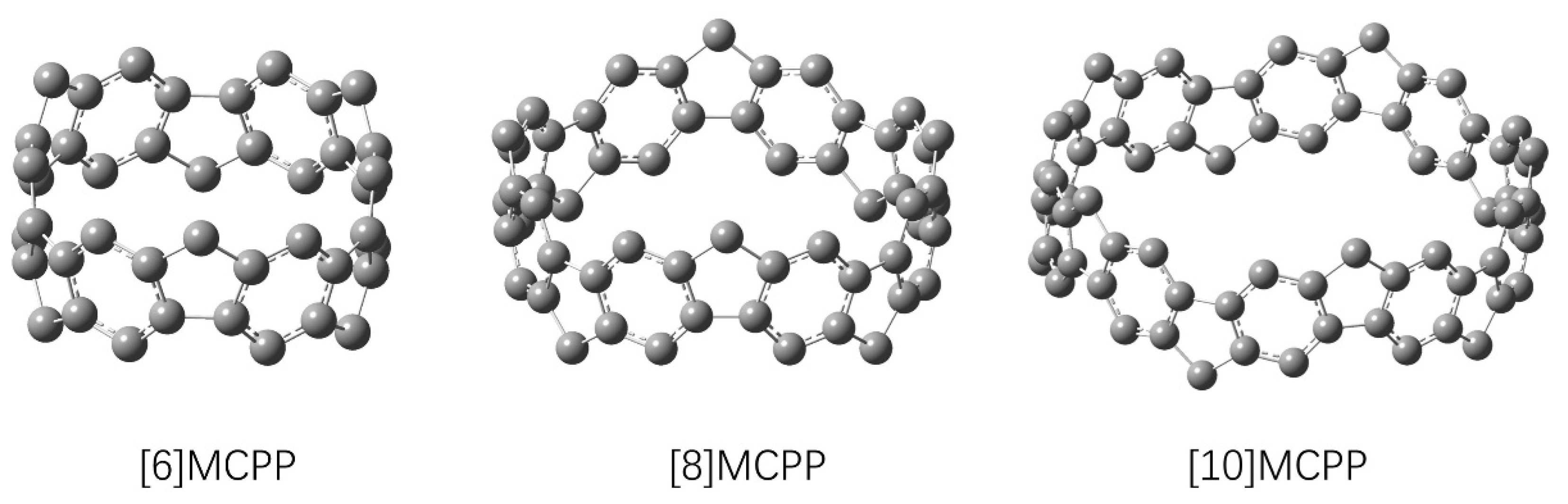

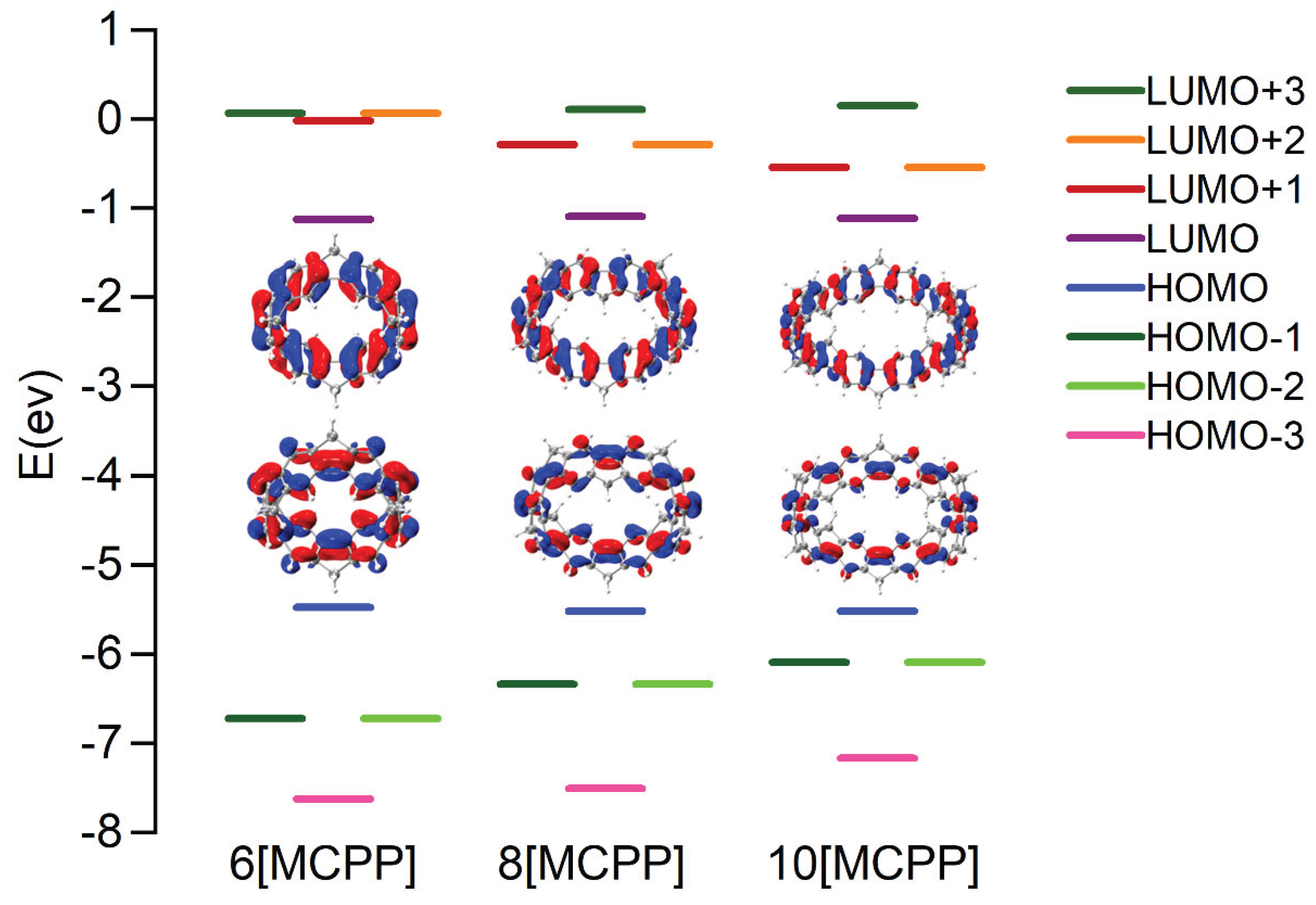

3.1. Molecular Structure

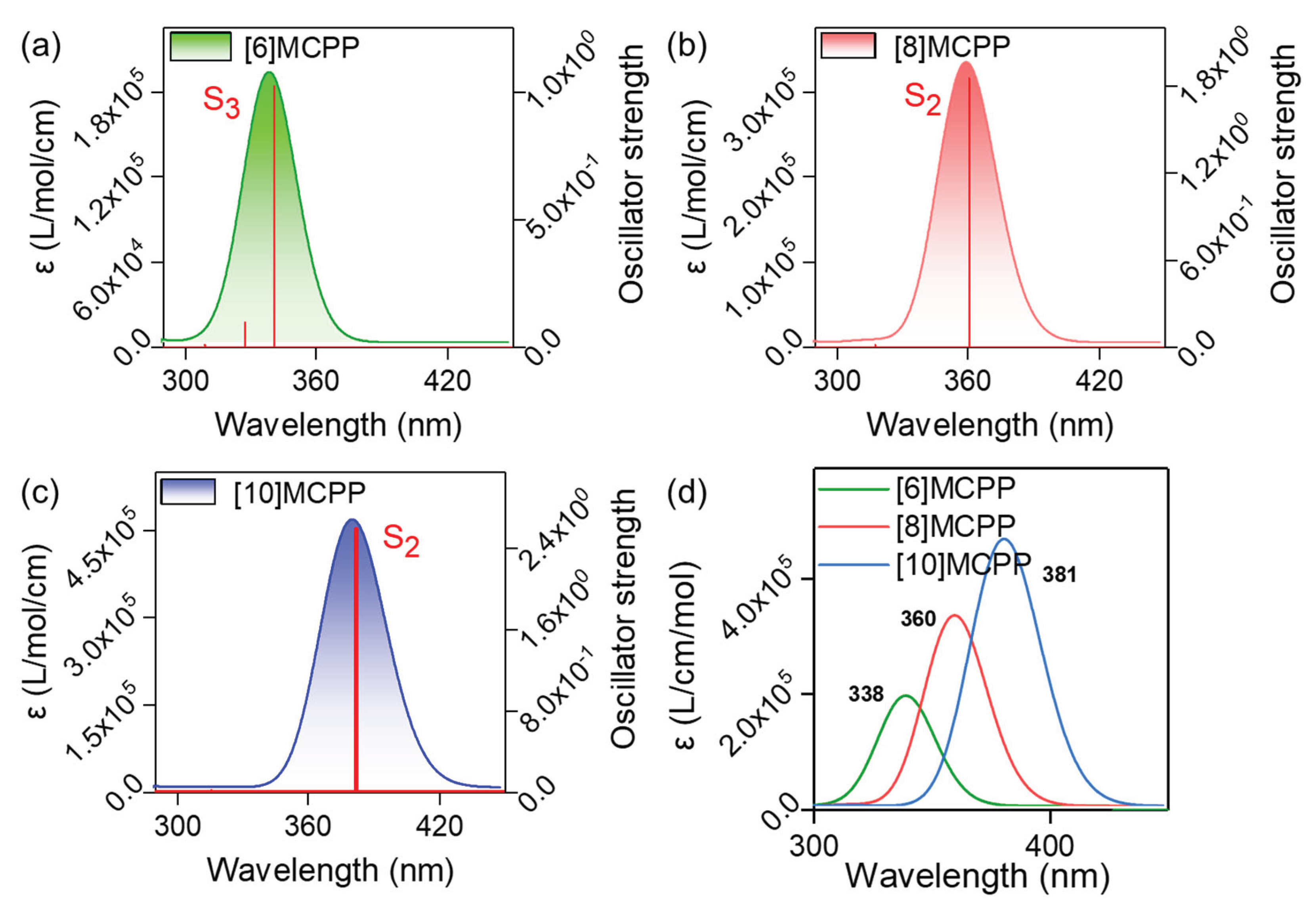

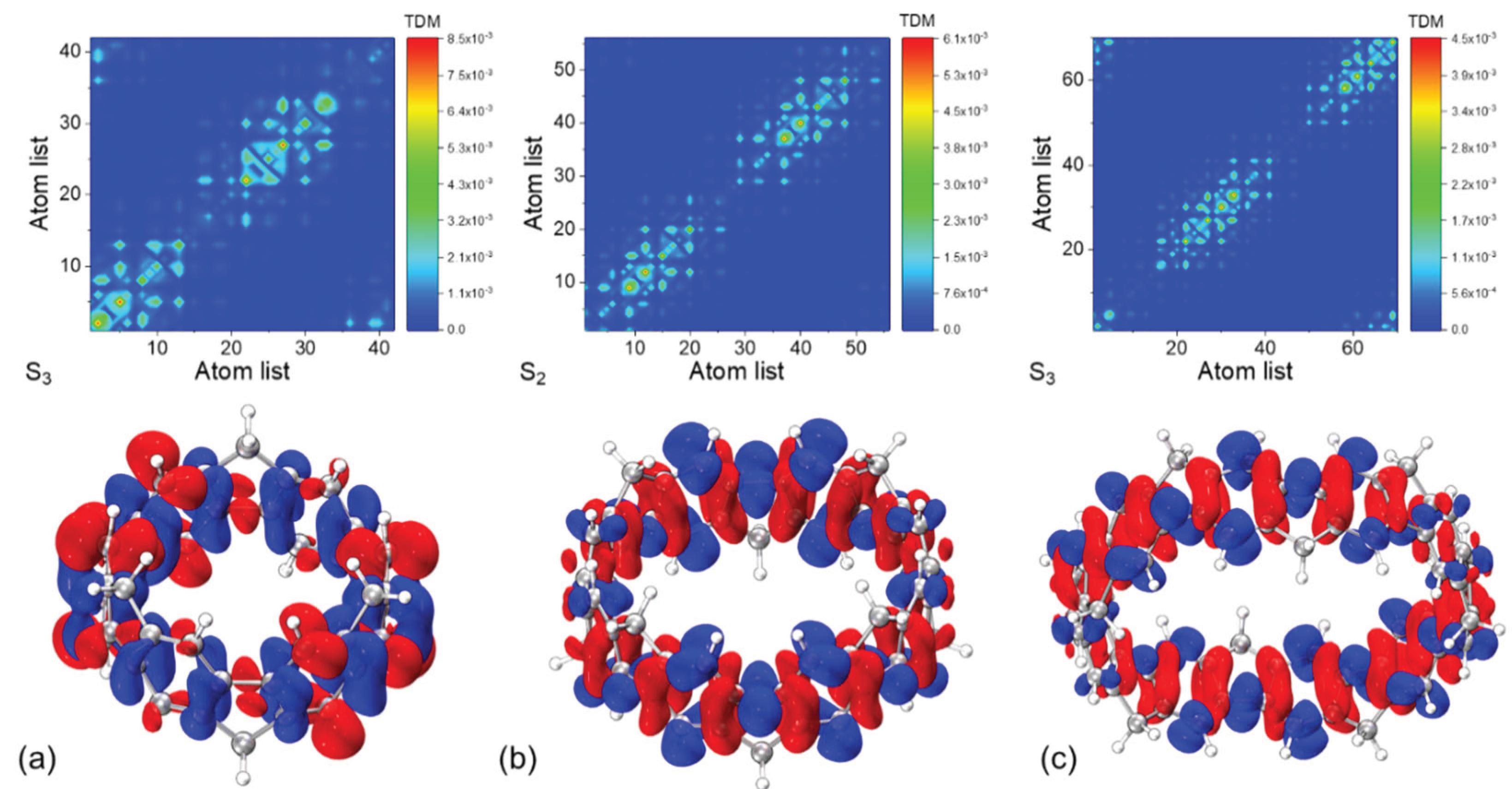

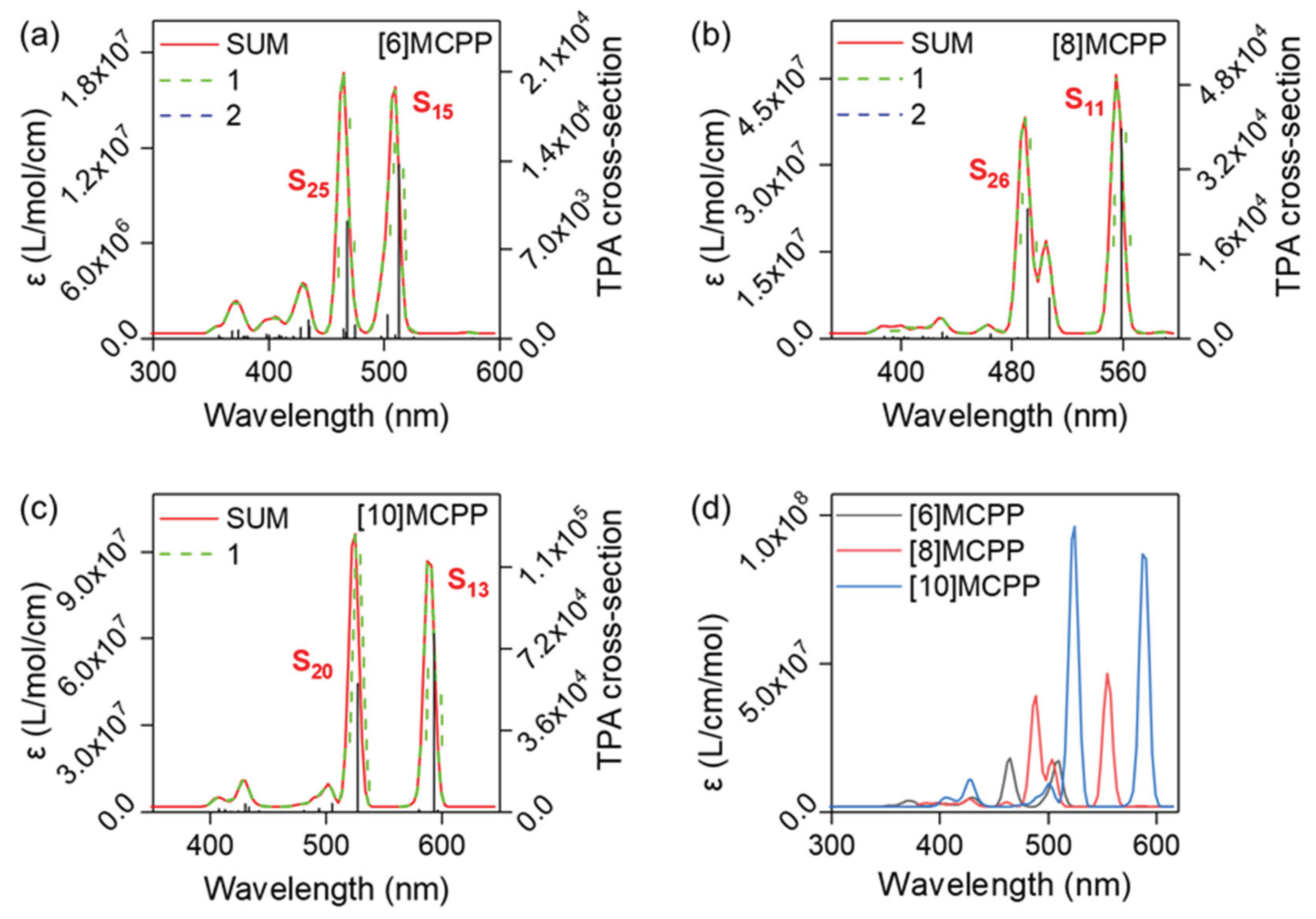

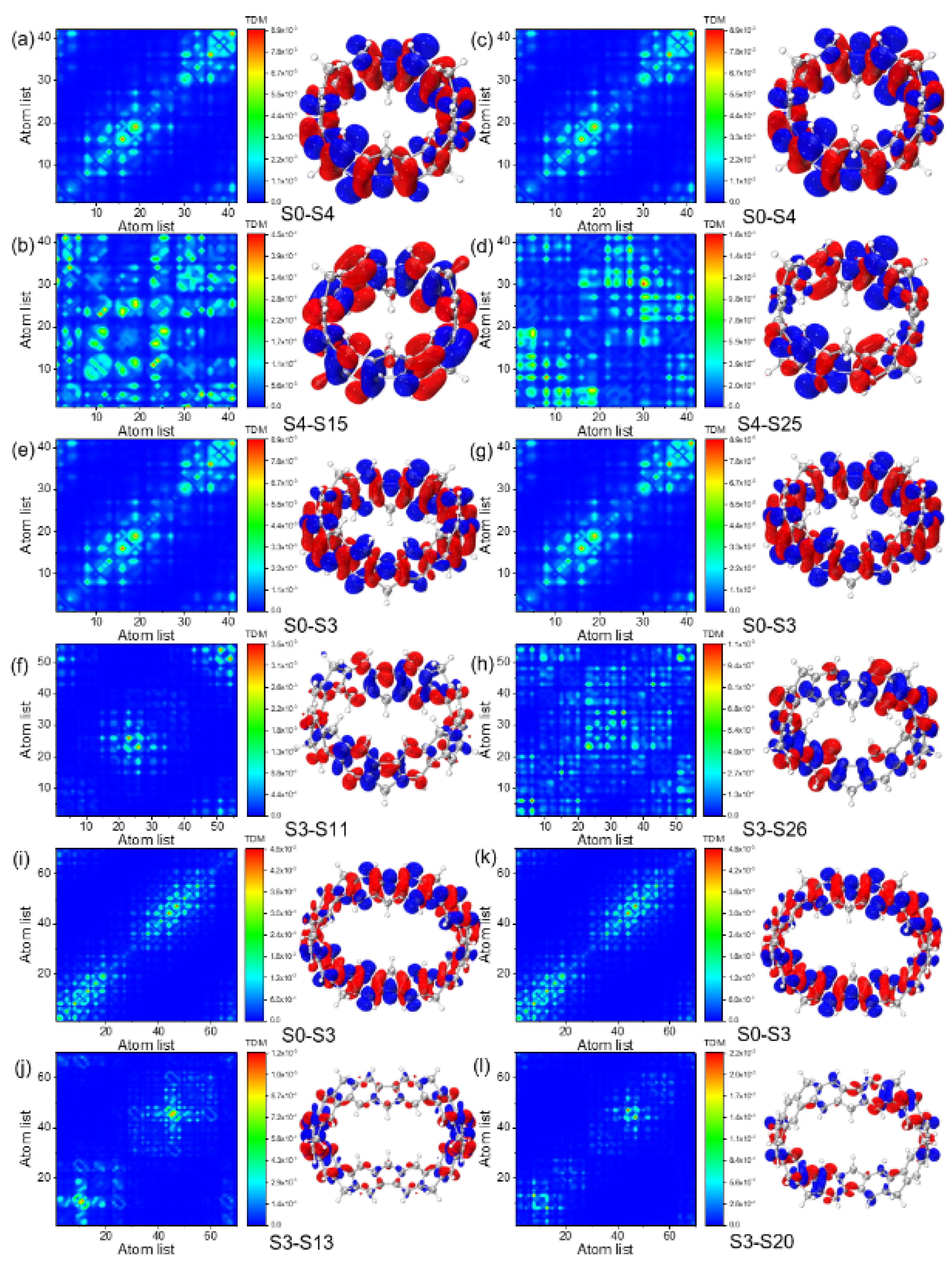

3.2. UV-Vis Spectra and Excited State Analysis

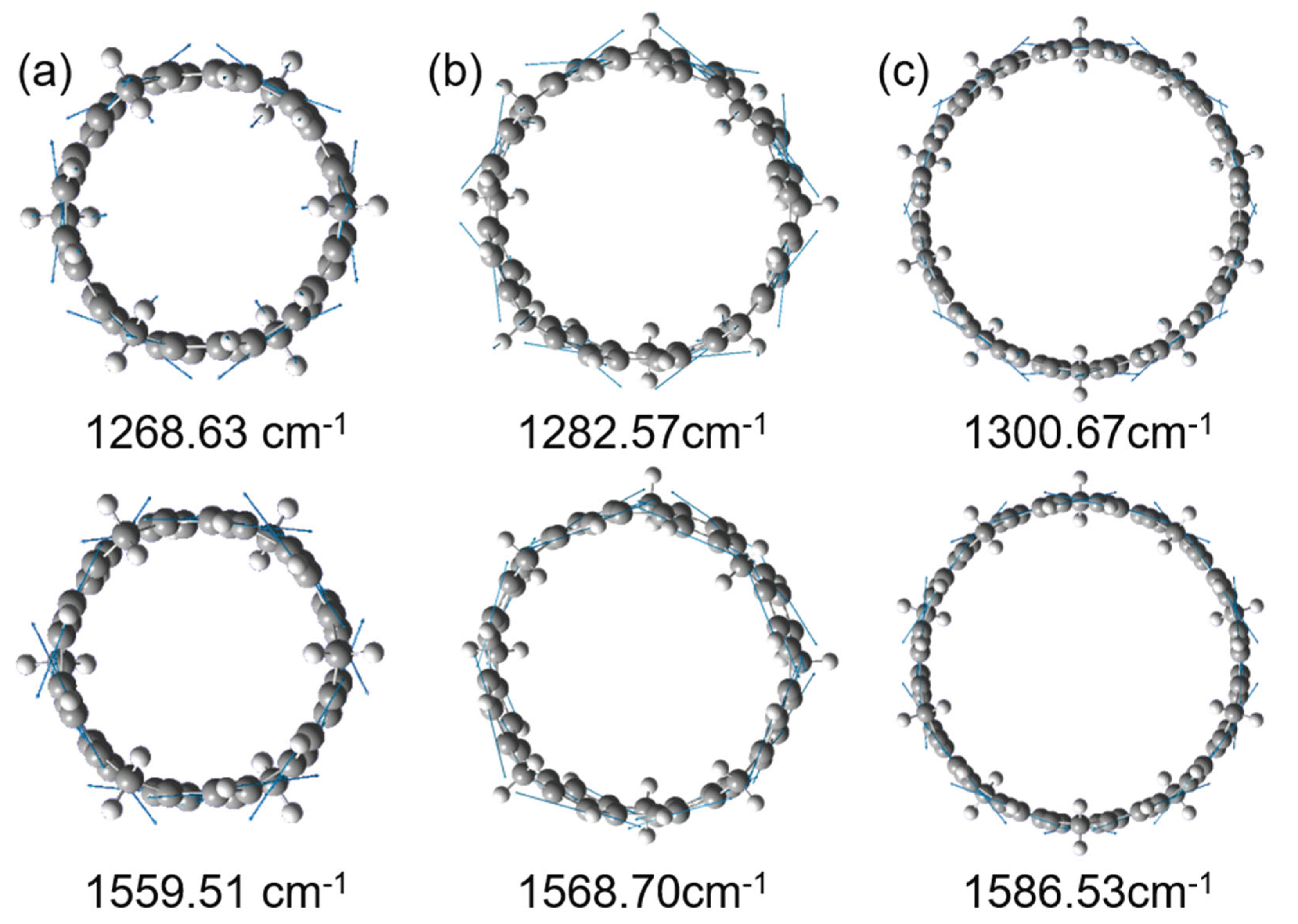

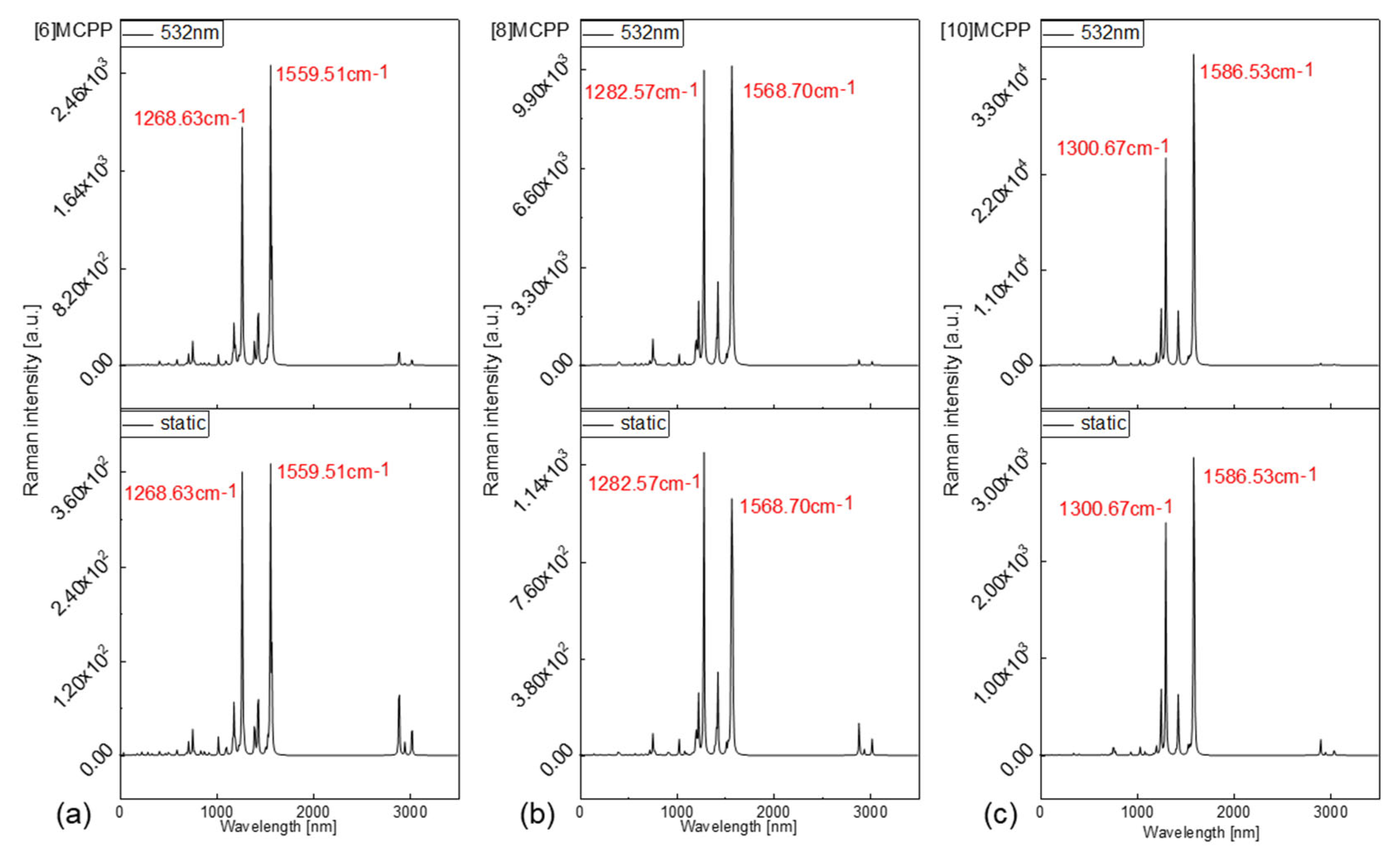

3.3. Raman Spectral Analysis

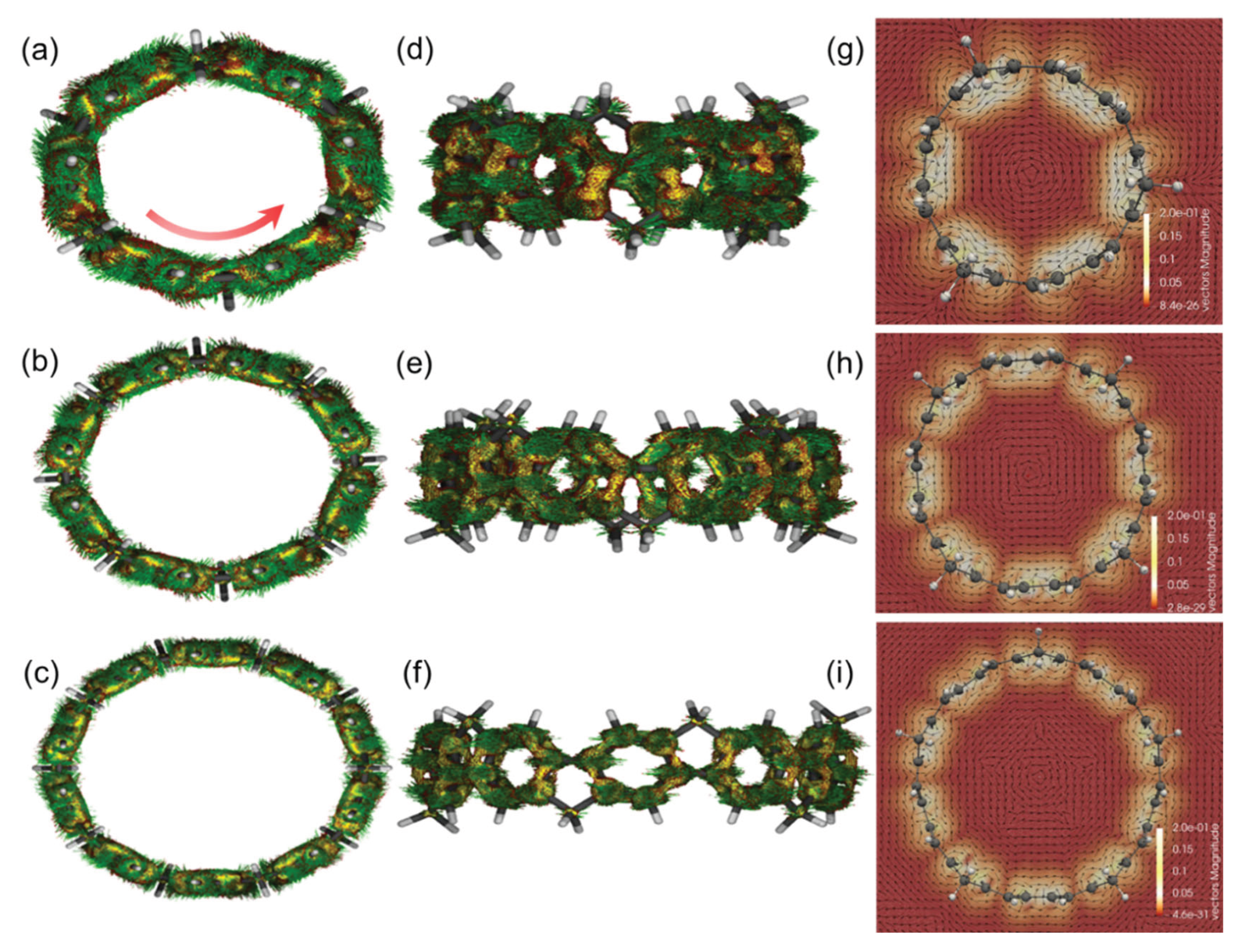

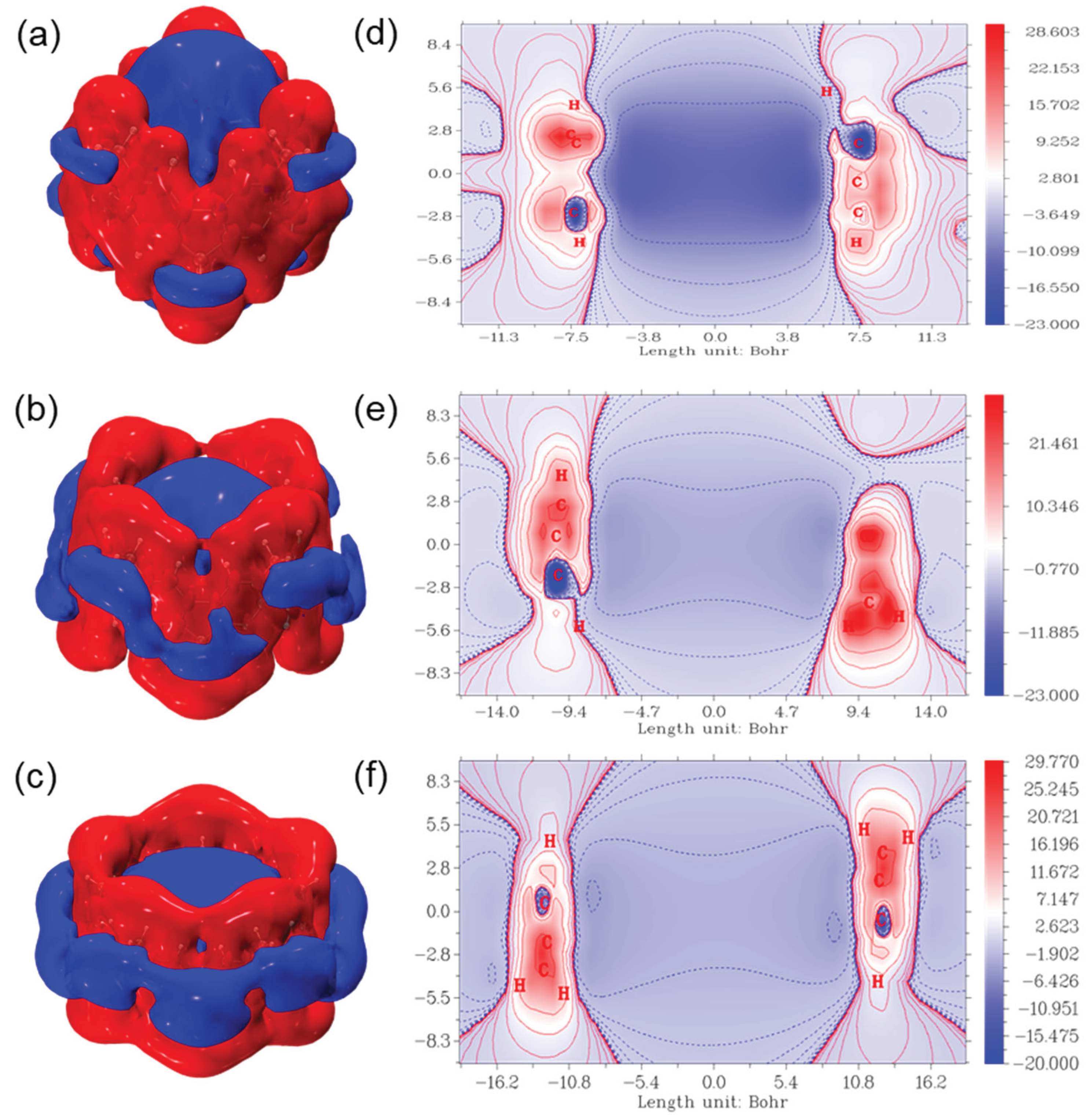

3.4. Response to External Magnetic Field: Anisotropy of Induced Current Density (AICD), Iso-Chemical Shielding Surface (ICSS), and Gauge-Including Magnetically Induced Current (GIMIC)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang Peng-Fei, Cheng Zheng-Dong. Applications of two-dimensional nanomaterials in biomedicine[J]. PHYSICS 2023, 52, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue Wu, Xinyuan Zhang, Zhe Ma, Weida Hong, Chunyu You, Hong Zhu, Yang Zong, Yuhang Hu, Borui Xu, Gaoshan Huang, Zengfeng Di, Yongfeng Mei. Nanomembrane on Graphene: Delamination Dynamics and 3D Construction. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 1–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, J. Hughes, Kavita A. Iyer, Robert E. Bird, Julian Ivanov, Saswata Banerjee, Gilles Georges, Qiongqiong Angela Zhou. Review of Carbon Nanotube Research and Development: Materials and Emerging Applications. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2024, 7, 18695–18713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han Deng, Zilong Guo, Yaxin Wang, Ke Li, Qin Zhou, Chang Ge, Zhanqiang Xu, Sota Sato, Xiaonan Ma, Zhe Sun. Modular synthesis, host–guest complexation and solvation-controlled relaxation of nanohoops with donor–acceptor structures. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 14080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Lucas, C. Brouillac, N. McIntosh, S. Giannini, J. Rault-Berthelot, C. Lebreton, D. Beljonne, J. Cornil, E. Jacques, C. Quinton, Electronic and Charge Transport Properties in Bridged versus Unbridged Nanohoops: Role of the Nanohoop Size. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202300934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- X. Gai, L. Zhang, J. Wang, Electronic Structure, Aromaticity and Optical Properties of Dehydro[10]annulene. ChemPhysChem 2023, 24, 202300246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H. , Gai, X., Sun, L. et al. Theoretical study on the prediction of optical properties and thermal stability of fullerene nanoribbons. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 28978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupam Roy, Clément Brouillac, Emmanuel Jacques, Cassandre Quinton, Cyril Poriel. Angew. π-Conjugated Nanohoops: A New Generation of Curved Materials for Organic Electronics. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202402608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinyu Zhang, Youzhi Xu, Pingwu Du, Functional Bis/Multimacrocyclic Materials Based on Cycloparaphenylene Carbon Nanorings. Accounts of Materials Research 2025, 6, 399–410. [CrossRef]

- Guillaume Povie; Yasutomo Segawa; Taishi Nishihara; Yuhei Miyauchi; Kenichiro Itami. Synthesis of a carbon nanobelt. Science 2017, 356, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasutomo Segawa; Tsugunori Watanabe; Kotono Yamanoue; Motonobu Kuwayama; Kosuke Watanabe; Jenny Pirillo; Yuh Hijikata & Kenichiro Itami. Synthesis of a Möbius carbon nanobelt. Nature Synthesis 2022, 1, 535–541. [CrossRef]

- Hideya Kono; Yuanming Li; Riccardo Zanasi; Guglielmo Monaco; Francesco F. Summa; Lawrence T. Scott; Akiko Yagi; Kenichiro Itami. Methylene-Bridged [6]-, [8]-, and [10]Cycloparaphenylenes: Size-Dependent Properties and Paratropic Belt Currents. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2023, 145, 8939–8946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng-Nan Lei; Ling Zhu; Ning Xue; Xuedong Xiao; Le Shi; Duan-Chao Wang; Zhe Liu; Xin-Ru Guan; Yuan Xie; Ke Liu; Lian-Rui Hu; Zhao-Hui Wang; J. Fraser Stoddart; QingHui Guo. Cyclooctatetraene-Embedded Carbon Nanorings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, e202402255. [CrossRef]

- Jia-Nan Gao; An Bu; Yiming Chen; Mianling Huang; Prof. Dr. Zhi Chen; Prof. Dr. Xiaopeng Li; Prof. Dr. Chen-Ho Tung; Prof. Dr. Li-Zhu Wu; Prof. Dr. Huan Cong. Synthesis of All-Benzene Multi-Macrocyclic Nanocarbons by Post-Functionalization of meta-Cycloparaphenylenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Florian Albrecht; Igor Ron cević; Yueze Gao; Fabian Paschke; Alberto Baiardi; Ivano Tavernelli; Shantanu Mishra; Harry L. Anderson; Leo Gross. The odd-number cyclo[13]carbon and its dimer, cyclo[26]carbon. SCIENCE 2024, 384, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James H., May; Jeff M. Van, Raden; Ruth L., Maust; Lev, N. Zakharov; Ramesh JastiNat. Active template strategy for the preparation of π-conjugated interlocked nanocarbons. Chem 2023, 15, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FENG Weijian, ZOU Yi, WANG Jingang. Aromaticity of Kekulene and Physical Mechanism of Photoinduced Charge Transfer[J]. Journal of Petrochemical Universities 2024, 37, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- LI Yue, GAI Xinwen, ZHAO Bo, et al. Chiral Nonlinear Luminescence Study of Pentaoxonium Salt Molecules Driven by Internal Electric Field Induced by Orbital Polarization[J]. Journal of Petrochemical Universities 2025, 38, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- YANG Zhiyuan, ZOU Yi, WANG Jingang. One and Two-Photon Absorption Properties of Twist Bilayer Graphene Nanosheets [J]. Journal of Petrochemical Universities 2023, 36, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ruitao Jia, Fangzhu Qing, Shurong Wang, Yuting Hou, Changqing Shen, Feng Hao, Yang Yang, Hongwei Zhu, Xuesong Li. Preparation of meter-scale Cu foils with decimeter grains and the use for the synthesis of graphene films. Journal of Materiomics 2024, 10, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Gai X, Zou Y, Jiang Y. The Physical Mechanism of Linear and Nonlinear Optical Properties of Nanographene-Induced Chiral Inversion. Molecules 2024, 29, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Trucks, G.; Schlegel, H.; Scuseria, G.; Robb, M.; Cheeseman, J.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.; Nakatsuji, H. Gaussian 16, revision a. 03, gaussian, inc., wallingford ct. Gaussian16 2016.

- Lu, T.; Chen, F.J.J.o.c.c. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. Computational Chemistry 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. Molecular Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 28, e202300348, J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 18593. Carbon 2020, 165, 468. Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202103815. [CrossRef]

- Geuenich, D.; Hess, K.; Köhler, F.; Herges, R. Anisotropy of the induced current density (ACID), a general method to quantify and visualize electronic delocalization. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3758–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persistence of Vision Pty. Ltd. (2004)Persistence of Vision Raytracer (Version 3.6)[Computer software].Retrieved from http://www.povray.org/download/.

- ParaView. (2023). Version 5.10. Kitware. Retrieved from https://www.paraview.org/.

- Barquera-Lozada, J.E.J.A.i.Q.C.T.B.Q. Scalar and vector fields derived from magnetically induced current density. Advances in Quantum Chemical Topology Beyond QTAIM 2023, 335–357. [Google Scholar]

- Xinwen Gai, Lei Zhang, Jingang Wang, Theoretical study of double antiaromatic structure - cyclo[16]carbon, Journal of Molecular Structure (2024). [CrossRef]

- Klod, S, Kleinpeter, E. Ab initio calculation of the anisotropy effect of multiple bonds and the ring current effect of arenes—application in conformational and configurational analysis. The Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2001, 2, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Liu, T. Lu, Q. Chen, An sp-hybridized all-carboatomic ring, cyclo[18]carbon: Bonding character, electron delocalization, and aromaticity. Carbon 2020, 165, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).