1. Introduction

The rapid growth of industrial activities has significantly increased environmental pollution, particularly in aquatic systems. Synthetic dyes, extensively used in the textile, agricultural, and cosmetics industries, are among the most common contaminants affecting water resources. Dyes such as Malachite Green (MG) and Rhodamine B exemplify hazardous pollutants that persist in ecosystems, posing severe risks to both human health and environmental quality [

1,

2]. MG, a triphenylmethane dye widely utilized in textiles, aquaculture, and as an antibacterial agent, is known for its toxic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic effects [

1]. Similarly, Rhodamine B, a xanthene dye commonly employed in biotechnology and materials science, exhibits adverse ecological and health impacts when present as a contaminant [

3,

4].

To address these environmental challenges, the development of detection methods that are rapid, highly sensitive, and selective has become crucial. Nonlinear optical techniques, such as Second Harmonic Generation (SHG), Frequency Mixing, and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS), have emerged as promising approaches for identifying trace contaminants by leveraging unique interactions between light and matter [

5]. These techniques enable the detection of extremely low concentrations of hazardous dyes with high selectivity, as demonstrated in previous studies [

6,

7,

8]. SHG, in particular, has been applied to monitor organic pollutants at interfaces, including studies that utilized rotational anisotropy SHG (RASHG) to characterize MG on silica surfaces and other solid-liquid interfaces [

9,

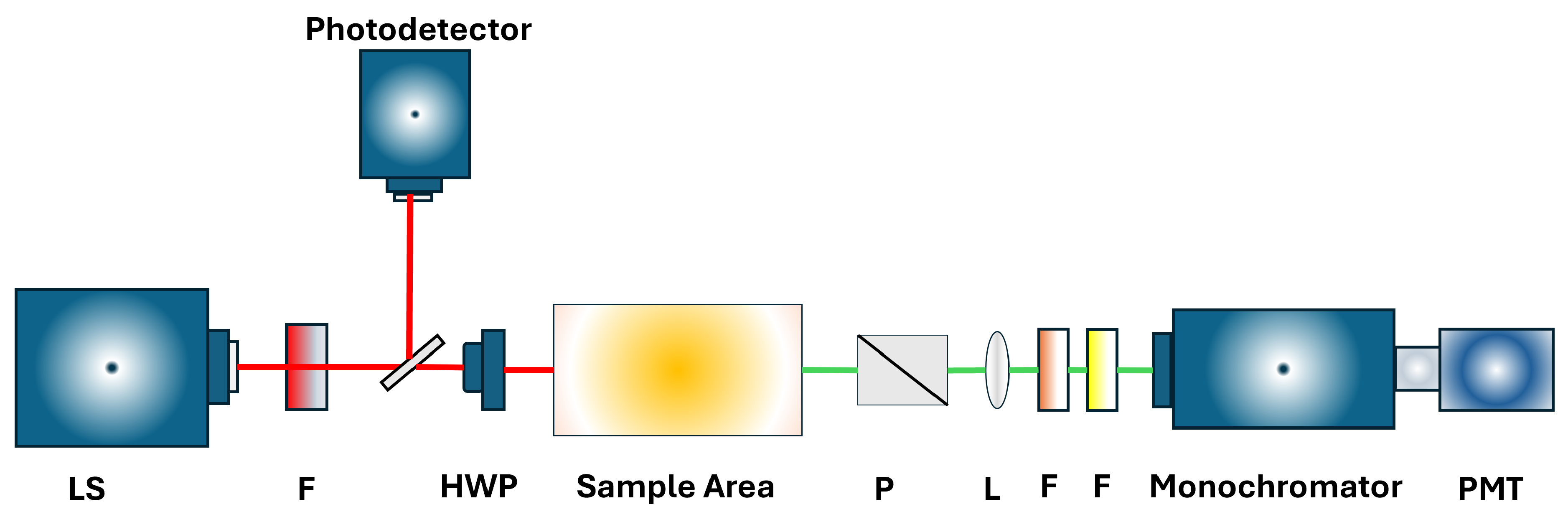

10]. An experimental RASHG setup used for such analyses is illustrated in

Figure 1, showcasing its capability to detect contaminants through SHG intensity profiles. An example of the real experimental setup is shown in Ref. [

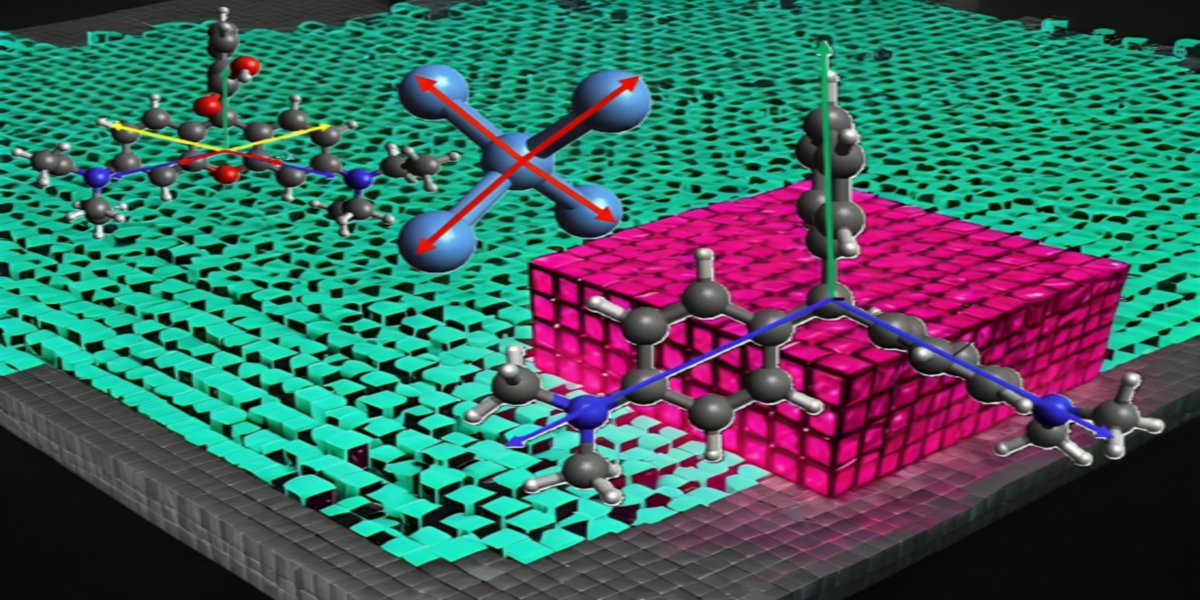

11]. In this study, the nonlinear Simplified Bond Hyperpolarizability Model (SBHM) is employed to analyze the SHG intensity profiles of MG and Rhodamine B adsorbed on silicon (Si(001)) substrates. The SBHM framework models the molecular structures using bond vectors and susceptibility tensors to predict SHG behavior at the nanoscale. Another novelty in this work is the possibility to enhance the detection SHG signal by applying a suitable organic dye absorbent e.g. Graphene Oxyde promoting stronger electronic coupling and higher molecular alignment. Therefore, we perform molecular docking simulations to investigate the adsorption mechanisms of Rhodamine B onto Graphene Oxide (GO) layers, revealing strong chemisorption dominated by

-

stacking and

-alkyl interactions, with a binding affinity of

kcal/mol. We will show how our results suggest that GO-coated silicon substrates offer a promising platform for detecting organic pollutants with high sensitivity, presenting an innovative approach for environmental monitoring and remediation [

12,

13].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nonlinear Optics Approach

Nonlinear optics explores the phenomena that arise when the optical properties of a material are altered under the influence of intense light, typically from lasers. In such cases, an external high-intensity field induces a dipole moment within the material, a phenomenon termed polarization. The total polarization

can be expressed as: [

7]

where

is the vacuum permittivity,

is the linear susceptibility, and

and

are the second- and third-order nonlinear susceptibilities, respectively. The electric fields

and

represent the applied fields. In this study, Cartesian coordinates (

x,

y, and

z) are chosen to align with the material’s symmetry.

Second-order polarization, associated with SHG, is influenced by the second-order susceptibility tensor

, which is expressed as:

This tensor contains 27 components, but symmetry considerations significantly reduce this number. For instance, under Kleinman symmetry and in molecules with symmetry, only specific components like and remain non-zero.

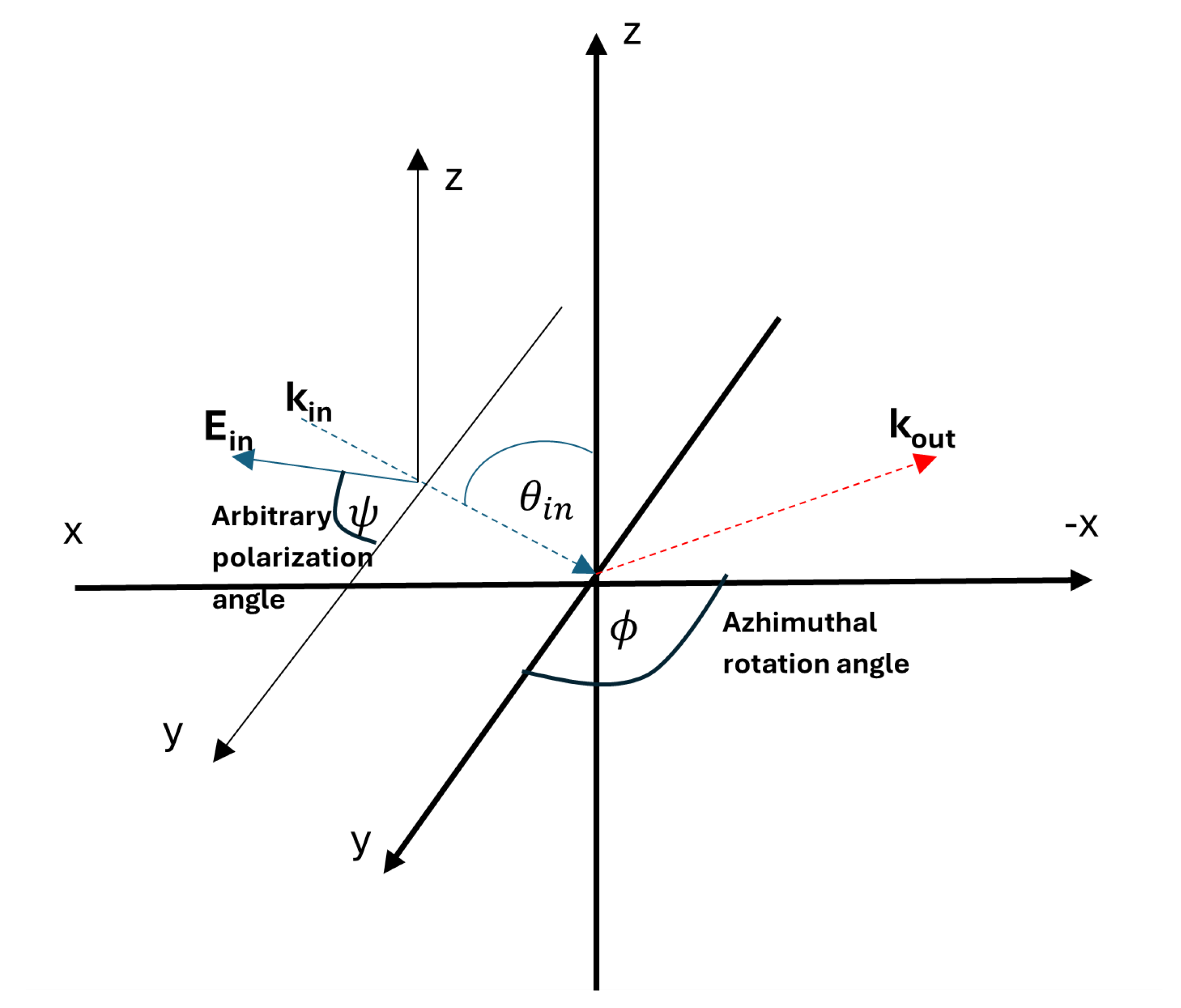

The simulation employs a coordinate system illustrated in

Figure 2, which is similar with the experiment in [

9]. Fundamental and SHG fields propagate along the

-plane. Input polarization is generalized, defined by:

where

is the angle of incidence relative to the

z-plane, and

represents the polarization angle, analyzed in increments of 10°.

2.2. Bond Vector Model

The surface second-order polarization is modeled based on the SBHM by Powell [

8] and Aspnes [

14]. It assumes nonlinear radiation is generated by anharmonic oscillations of dipoles along atomic bonds. The second-order polarization is given by:

where

is the polarization occurring at the surface section and

is the input electric field, while

is the hyperpolarizability for 2nd-order nonlinear polarization. The

is the rotation matrix about the

z-axis, and

is the vector of each bond. The form of the rotation matrix

defines the rotation matrix about the

z-axis, which can be written in the form of Equation (

5) [

7].The bond vector

indicates the dipole orientation of individual bonds silicon, MG, and Rhodamine B for different simulation.

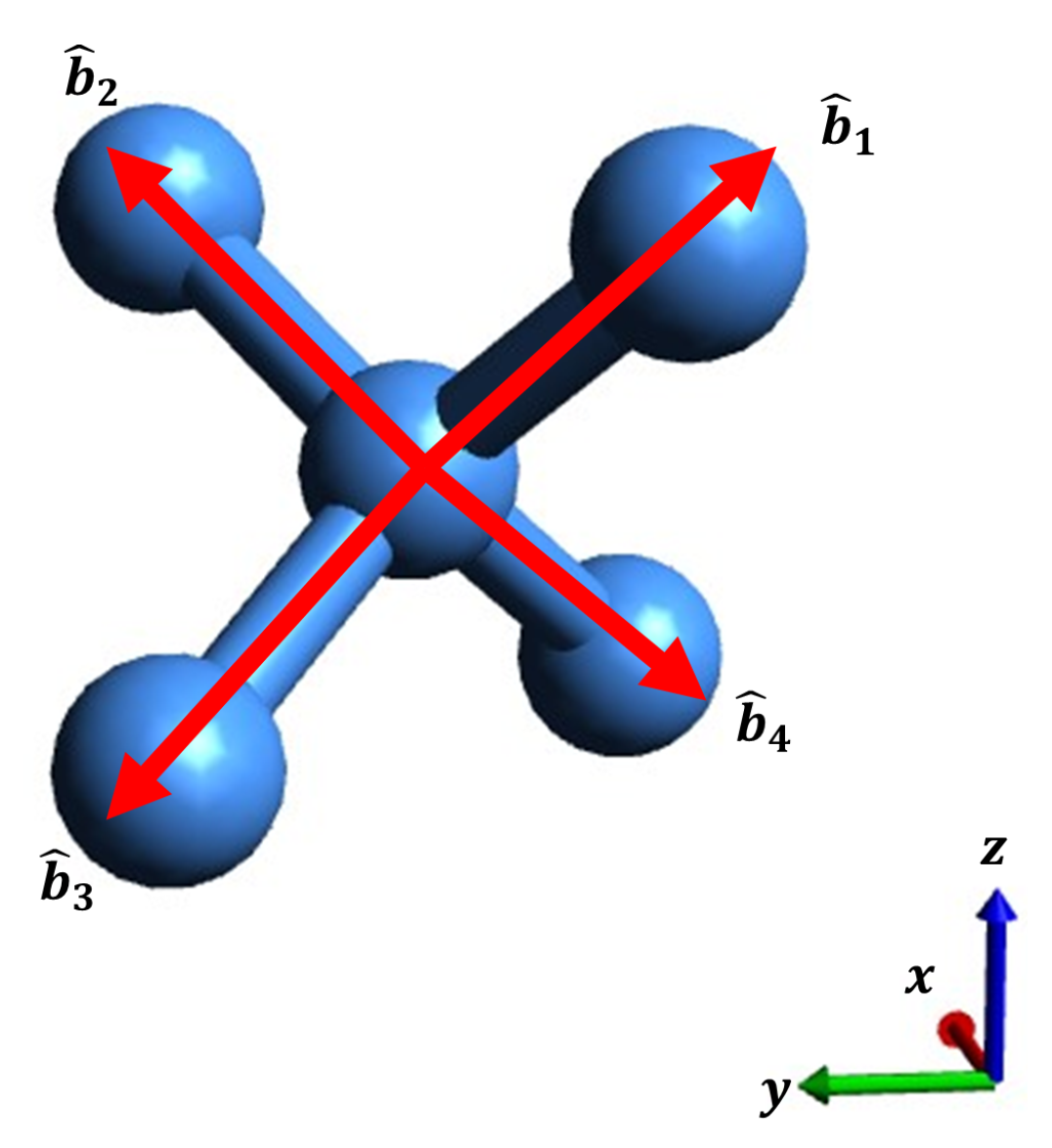

Figure 3 illustrates the structure of Si(001) along with its four bonding vectors

. Each of these bonding vectors has a representation in Cartesian coordinates, as shown in Equation

6.

where

. Furthermore,

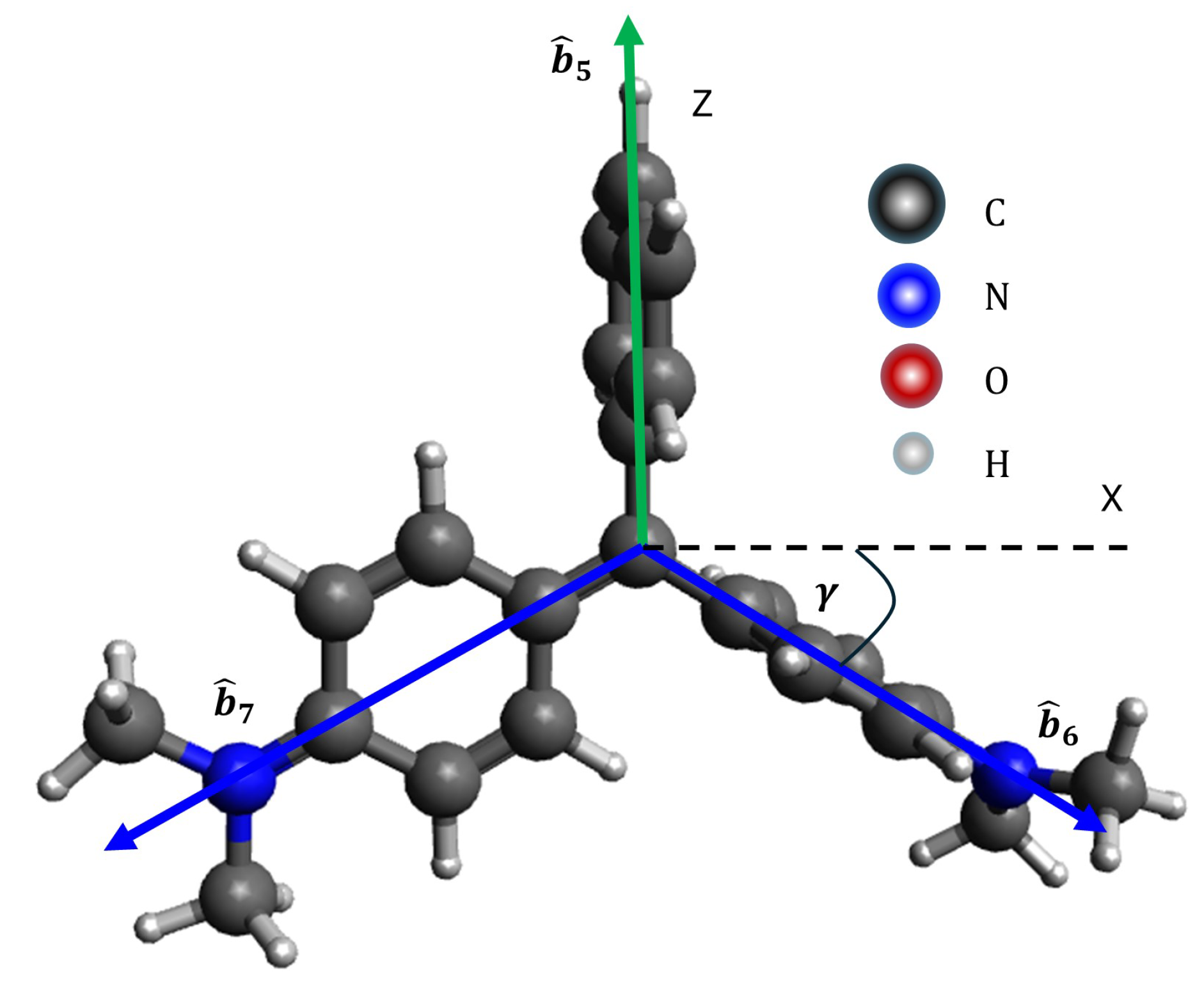

Figure 4 presents the structure of MG, with its bonding vectors represented as shown in Equation

7 and the bond vectors are denoted by

[

15].

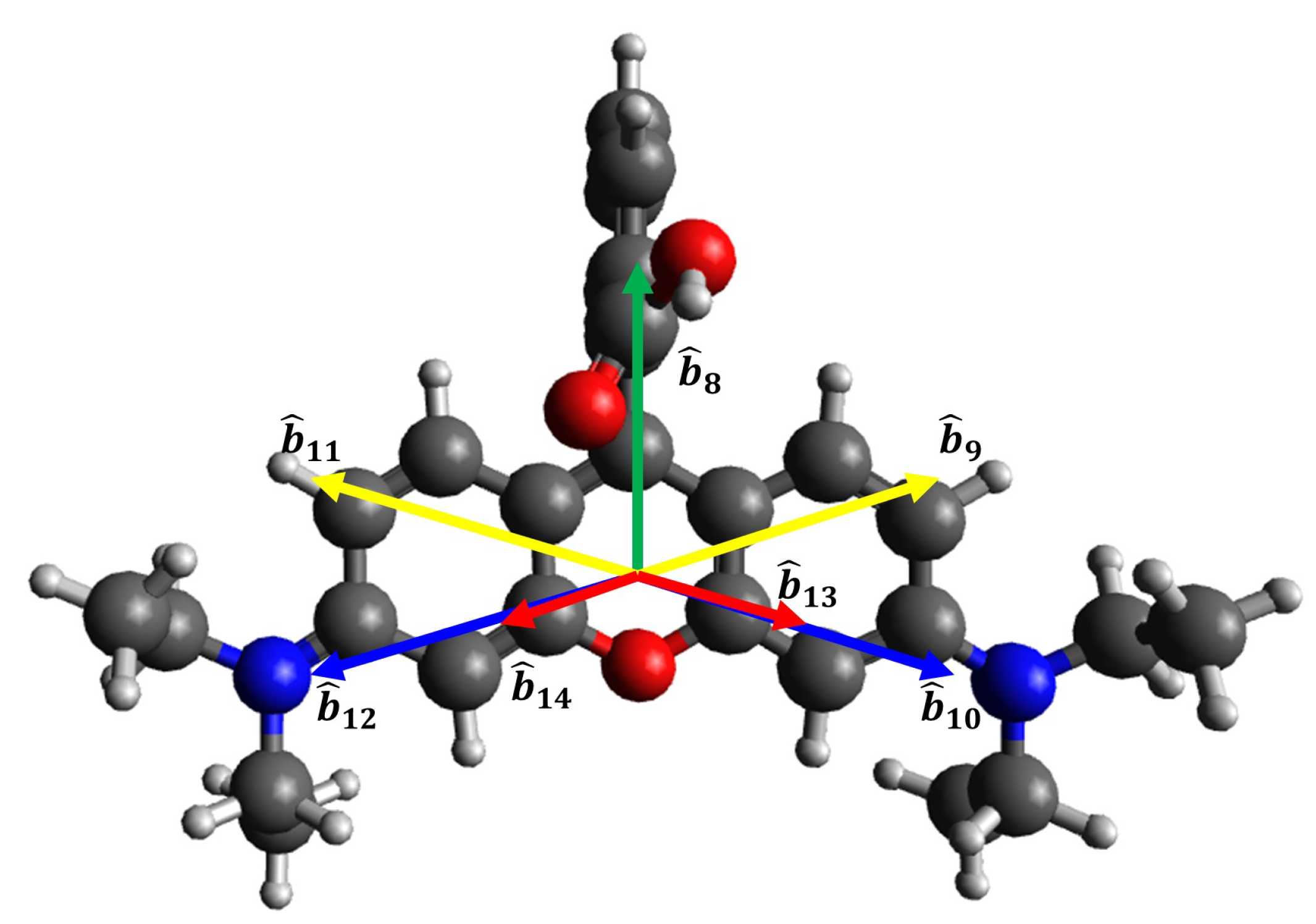

The structures of Rhodamine B is illustrated in

Figure 5. The bond vectors represented in Cartesian coordinates is detailed by Equations

8, with the bond vector for Rhodamine B denoted as

. In bond vectors, there exists a

representing the angle between the vector

to the x-axis. Under conditions of sufficiently high adsorbate concentration, the molecular orientation is predominantly perpendicular, as shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 This situation occurs because in the layer closest to the silica substrate, the adsorbate molecules adopt a parallel orientation, while in the subsequent layers, the orientation may be tilted or perpendicular [

10,

16,

17,

18].

2.3. Molecular Docking Simulation

Molecular docking simulations were conducted using AutoDock Vina [

19] on a MacBook with a 1.6 GHz Intel Core i5 processor, 4 GB RAM, and Intel HD Graphics 6000. Chimera software [

20] was employed for preparation, visualization, and analysis. Structures for GO (PubChem CID: 124202900) and Rhodamine B (PubChem CID: 6694) were obtained in SDF format from PubChem and converted to PDB format using Chimera. Polar hydrogens and Gasteiger charges were added to the ligands, and blind docking was performed to evaluate adsorption on GO, with the number of modes set to 10 and exhaustiveness to 8.

3. Results and Discussion

MG and Rhodamine B are widely used as textile dyes due to their strong optical properties, particularly their ability to absorb and emit light efficiently. These molecules are known to exhibit characteristics of SHG and fluorescence, with Rhodamine B being especially prominent in fluorescence applications because of its high efficiency in light emission upon excitation. The molecular symmetry of these dyes, classified as , enhances their optical stability. Furthermore, their planar structures and extensive electron delocalization enable strong absorption in the visible light spectrum, allowing effective interactions with specific wavelengths.

These dyes are also cationic, bearing a positive charge, which facilitates electrostatic interactions with negatively charged surfaces such as silica. These unique characteristics make them ideal for studying nanoscale interactions at interfaces [

15,

16,

18,

21].

3.1. Susceptibility Tensor and Group Theory

Silicon with a Si(001) orientation belongs to the

point group symmetry [

22]. The components of its susceptibility tensor, derived from group theory and the SBHM [

6], are represented in Eqs.

9 and

10.

Here, the non-zero tensor components are , , , , , and , all of which are equal, as , where . The SBHM approach confirms these components, matching the predictions of group theory.

The molecular structures of MG and Rhodamine B exhibit

symmetry. This symmetry results in non-zero tensor components as shown in Eq.

11, as previously discussed in Ref. [

15].

According to Refs. [

9,

10], the independent, non-vanishing quadratic susceptibility tensor components

,

, and

are critical for analyzing isotropic and achiral interfaces. The subscripts in these tensors represent the Cartesian coordinates of the laboratory reference frame.

3.2. SBHM Simulation

3.2.1. MG/Si(001)

MG belongs to the

point group symmetry [

23], with its non-zero susceptibility tensor components derived from group theory as shown in Eq.

11. Using the SBHM approach, the susceptibility tensor of MG can be represented as:

where

, and

represents the hyperpolarizability of MG, which is critical for interactions with an electric field. The relationship between the tensor components derived using group theory and SBHM is expressed as:

The susceptibility tensor in Eq.

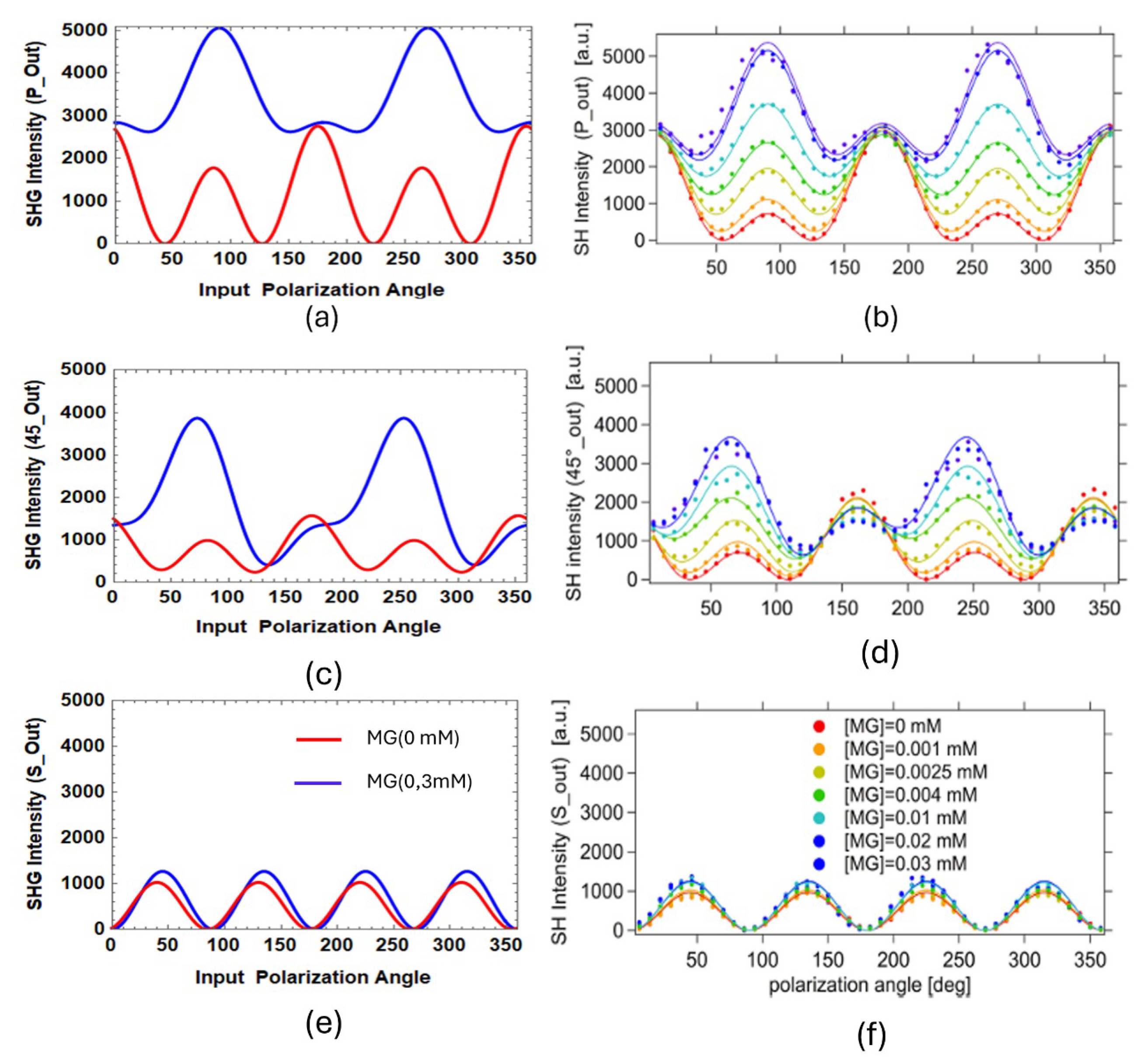

12 underpins the SBHM simulation of the MG/Si(001) system, with the resulting SHG intensity presented in

Figure 6. According to our previous work [

15], simulations of MG on Si(001) or Si(111) surfaces reveal that silicon’s contribution to the SHG intensity is minimal, with the SHG signal dominated primarily by MG.

Figure 6(a), (c), and (e) depict the simulated SHG intensity results, while

Figure 6(b), (d), and (f) display experimental results for MG at a concentration of 0.03 mM [

9]. The simulation and experimental patterns exhibit strong agreement. At 0.03 mM, MG molecules are likely to overlap, forming a parallel orientation in the layer closest to the Si(001) substrate. In this arrangement, all aromatic groups are positioned adjacent to the substrate due to hydrophobic interactions. Conversely, the upper layer molecules adopt a perpendicular orientation [

10,

15], with the

vector aligned along the z-axis. These perpendicularly oriented molecules primarily contribute to the SHG signal, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

3.2.2. Rhodamine-B/Si(001)

Rhodamine B also exhibits

symmetry [

18,

21]. Using the SBHM approach, the susceptibility tensor for Rhodamine B is expressed as:

where

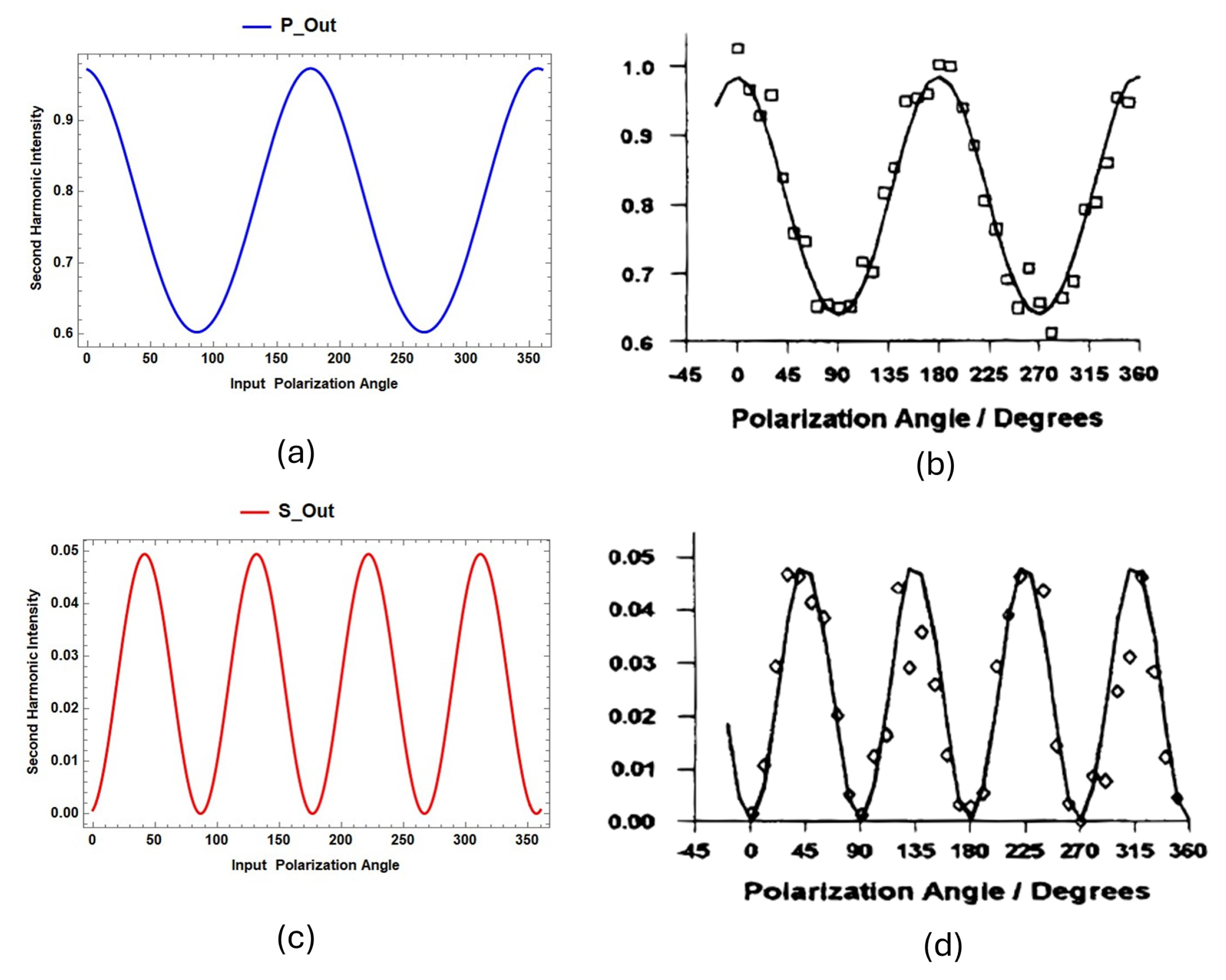

. By applying the SBHM framework, the SHG intensity simulation results for Rhodamine B on Si(001) are shown in

Figure 7.

The SBHM simulation results align closely with experimental findings reported in Ref. [

21]. In these simulations, Rhodamine B molecules adopt a perpendicular orientation, with the two amine groups positioned near the silica surface, while the aromatic group extends outward [

21]. Notably, the SHG intensity patterns observed in Ref. [

18] resemble the SBHM simulation results in

Figure 7(a) and (c). These findings confirm that Rhodamine B’s perpendicular molecular orientation significantly contributes to the observed SHG signal.

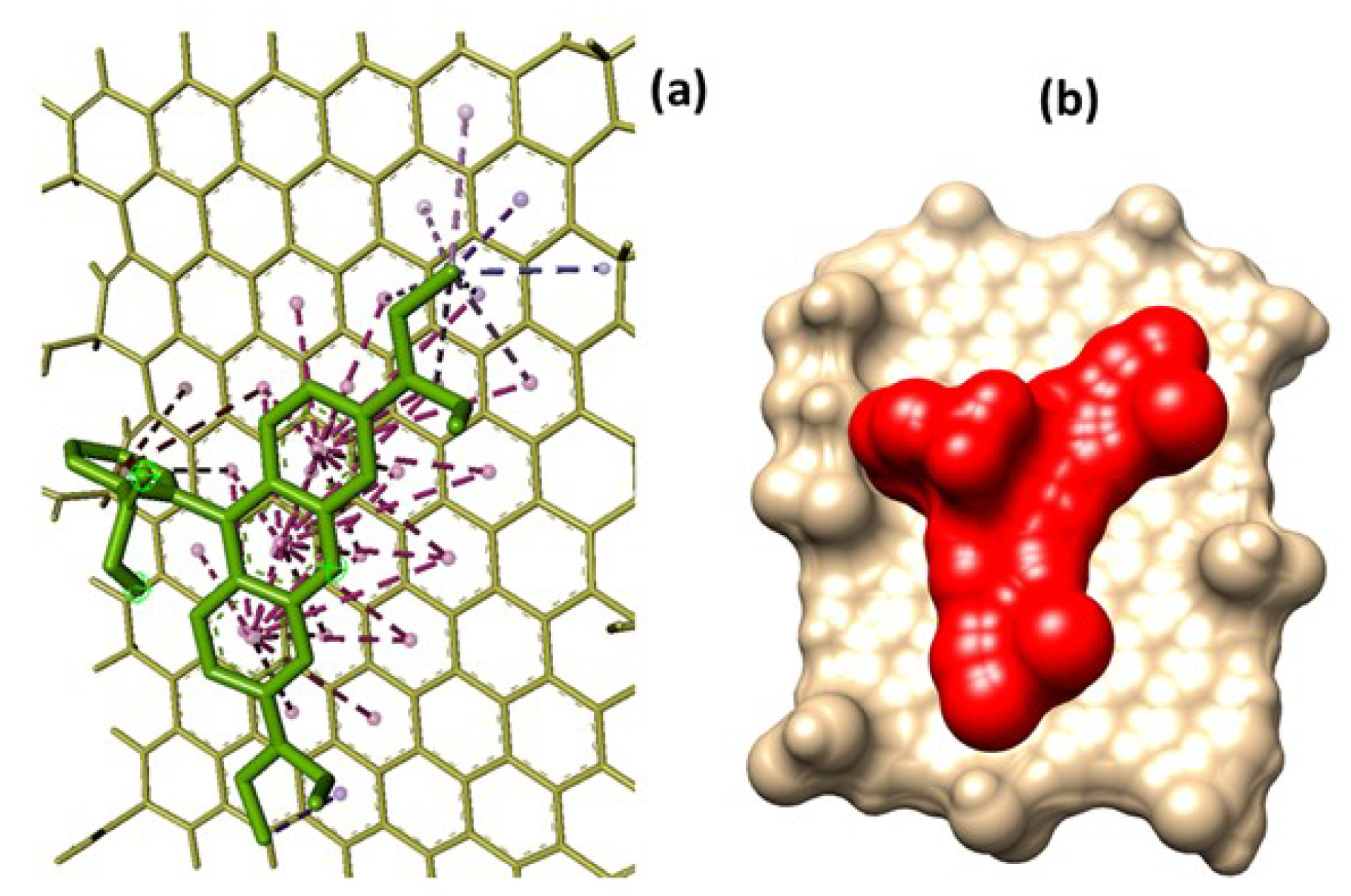

3.2.3. Molecular Docking Simulation of Rhodamine B Adsorbate Using a Graphene Oxyde Layer

It is interesting to explore how the MG SHG intensity can be further enhanced through insertion of a binding substance such as Graphene Oxyde. When Rhodamine B binds to GO, it can alter the electronic structure of the GO surface, potentially enhancing the SHG signal by increasing the local field effects or inducing greater asymmetry in the system. In addition the attachment of Rhodamine B to GO could create a more ordered system, improving the alignment of dipoles, which causes higher SHG detection. In addition, applying a laser frequency close to the electronic absorption of Rhodamine B-GO e.g. resonance enhancement could further amplify the SHG signal. Here we have performed molecular docking simulation to investigate the binding energy and mechanism.

The molecular docking simulation results identified the strongest binding affinity as

.

Figure 8 illustrates the binding pose of Rhodamine B on the GO surface for this highest-affinity mode. Rhodamine B is tightly bound near the center of the GO surface. Other binding modes similarly occupy regions around the mid-surface of GO, with comparable binding affinities ranging between

and

. Details of the molecular interactions are summarized in

Table 1.

The interactions are predominantly governed by long-range, weak interactions, including

-

stacking,

-alkyl,

-sigma,

-

T-shaped, and alkyl interactions. These interaction types suggest that Rhodamine B undergoes chemisorption onto the GO surface [

24].

Among these,

-

stacking is the most significant, with 36 instances observed. This non-covalent bonding arises from interactions between the electron clouds of parallel aromatic rings. The abundance of aromatic rings on the GO surface facilitates strong bonding with Rhodamine B, making GO a promising adsorbent for removing organic contaminants like Rhodamine B from water [

25,

26,

27].

Our result show that the attachment of Rhodamine B (RhB) molecules to a graphene oxide (GO) layer has the potential to enhance the second harmonic generation (SHG). RhB is a dye with strong nonlinear optical properties, attributed to its delocalized -electron system, which interacts efficiently with light. Graphene oxide, with its high surface area and functional groups, serves as an excellent platform for hosting RhB molecules, enabling electronic coupling and alignment that favor nonlinear optical processes such as SHG. The interaction between RhB and GO can enhance the local electric field at the interface, primarily through charge transfer or dipole interactions, thereby further amplifying the SHG signal. Furthermore, the electronic states of RhB and GO may create resonance conditions that align with the SHG wavelength, leading to a significant increase in intensity. The attachment to GO also helps orient RhB molecules in a manner that optimizes their nonlinear response, enhancing the overall second-order susceptibility.

4. Conclusion

Based on the simulation results conducted in this study, investigations of the silicon (001) surface with MG reveal that both experimental and simulation results produce identical SHG intensity patterns across all polarization angles. This finding indicates a polarization contribution arising from both the silicon substrate and MG molecules on the surface. Additionally, the structural configuration of MG, resembling an inverted Y at its center, provides a useful reference for future research on nanoscale interactions and surface dynamics.

Similarly, SHG intensity patterns for Rhodamine B on silica surfaces show strong agreement between experimental and simulation results, further validating the model’s predictive capability.

Through molecular docking simulations, this study also demonstrated that graphene oxide (GO) is highly effective in adsorbing Rhodamine B contaminants, exhibiting a strong binding affinity of . The adsorption mechanism is classified as chemisorption, as evidenced by the dominance of - stacking and -alkyl interactions. These conjugated -electron system contributes to significant SHG nonlinear susceptibility enhancement and in turn enhance the SHG signal.These findings highlight the potential of a GO coating on silicon layers to serve as an effective adsorbent for detecting and mitigating waterborne contaminants like Rhodamine B.

Overall, the combination of nonlinear bond modeling and molecular simulations provides a robust framework for understanding and optimizing nanoscale organic contaminant detection mechanisms at various surfaces. Future research may expand on these insights to explore additional contaminant molecules and surface configurations while the enhancements through photonic nanostructures are expected [

15,

28].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H. and M.D.B.; methodology, M.A.; software, H.H., A.K., F.N., and M.A.; validation, M.A., A.K., F.H., and H.A.; formal analysis, M.A. T.I.S. and F.N.; investigation, H.A., E.H.H. F.H.; resources, M.D.B., F.H., T.I.S.,E.H.H.; data curation, H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H., M.A., and T.I.S.; writing—review and editing, H.H.and M.D.B; visualization, F.H., E.H.H.,H.A., M.D.B; supervision, H.H. and M.D.B.; project administration, H.H., M.D.B.; funding acquisition, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Penelitian Dasar Kompetitif Nasional (PDKN) scheme Grant No. 102/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2023 (Contract No. 102/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2023). Hibah Riset Kolaborasi Nasional (RiNa) Grant No. 492/IT3.D10/PT.01.03/P/B/2023.

Data Availability Statement

The data concerning all the results in this work are not publicly available at this moment but may be obtained from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

T.I.S. would like to acknowledge research funding from the Penelitian Dasar Kompetitif Nasional (PDKN) scheme Grant No. 102/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2023 (Contract No. 102/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2023). H.H. acknowledges partial funding from the Hibah Riset Kolaborasi Nasional (RiNa) Grant No. 492/IT3.D10/PT.01.03/P/B/2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sudova, E.; Machova, J.; Svobodova, Z.; Vesely, T. Negative effects of malachite green and possibilities of its replacement in the treatment of fish eggs and fish: A review. Vet. Med. 2007, 52, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, B.H.; El-Khaiary, M.I. Batch removal of malachite green from aqueous solutions by adsorption on oil palm trunk fibre: Equilibrium isotherms and kinetic studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 154, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadez-Renteria, E.; Oliva, J.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, V. A sustainable and green chlorophyll/TiO2:W composite supported on recycled plastic bottle caps for the complete removal of Rhodamine B contaminant from drinking water. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 315, 115204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladoye, P.O.; Kadhom, M.; Khan, I.; Hama Aziz, K.H.; Alli, Y.A. Advancements in adsorption and photodegradation technologies for Rhodamine B dye wastewater treatment: fundamentals, applications, and future directions. Green. Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 440–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.W. Chapter 1 - The Nonlinear Optical Susceptibility. In Nonlinear Optics (Fourth Edition); Boyd, R.W., Ed.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 1–64. [CrossRef]

- Alejo-Molina, A.; Hardhienata, H.; Hingerl, K. Simplified bond-hyperpolarizability model of second harmonic generation, group theory, and Neumann’s principle. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2014, 31, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardhienata, H.; Prylepa, A.; Stifter, D.; Hingerl, K. Simplified bond-hyperpolarizability model of second-harmonic-generation in Si(111): Theory and experiment. J. Phys. Conf. 2013, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.; Wang, J.F.; Aspnes, D. Simplified bond-hyperpolarizability model of second harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. B. 2002, 65, 205320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassin, P.M.; Martin-Gassin, G.; Prelot, B.; Zajac, J. How to distinguish various components of the SHG signal recorded from the solid/liquid interface? Chem. Phys. Lett 2016, 664, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikteva, T.; Star, D.; Leach, G.W. Optical Second Harmonic Generation Study of Malachite Green Orientation and Order at the Fused-Silica/Air Interface. J.Phys.Chem. B. 2000, 104, 2860–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitböck, C.; Stifter, D.; Alejo-Molina, A.; Hingerl, K.; Hardhienata, H. Bulk quadrupole and interface dipole contribution for second harmonic generation in Si(111). J. Opt. 2016, 18, 035501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, J.; Naeem, A.; Farooq, M.; Shah Zareen, F.; Sherazi, S. Kinetic studies of graphene oxide towards the removal of rhodamine B and congo red. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021, 101, 1258–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.E.; Abdelwahab, M.S.; Ibrahim, G.A. Surface functionalization of magnetic graphene oxide@bentonite with α-amylase enzyme as a novel bionanosorbent for effective removal of Rhodamine B and Auramine O dyes. Mater. Chem. Phys 2023, 301, 127638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspnes, D.E. Bond models in linear and nonlinear optics. Phys. Status Solidi A 2010, 247, 1873–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahyad, M.; Hardhienata, H.; Hasdeo, E.H.; Wella, S.A.; Handayasari, F.; Alatas, H.; Birowosuto, M.D. A Novel Sensing Method to Detect Malachite Green Contaminant on Silicon Substrate Using Nonlinear Optics. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, D.A.; Byerly, S.K.; Abrams, M.B.; Corn, R.M. Second harmonic generation studies of methylene blue orientation at silica surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 6984–6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikteva, T.; Star, D.; Zhao, Z.; Baisley, T.L.; Leach, G.W. Molecular Orientation, Aggregation, and Order in Rhodamine Films at the Fused Silica/Air Interface. J.Phys. Chem. B. 1999, 103, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukanova, V.; Lavoie, H.; Harata, A.; Ogawa, T.; Salesse, C. Microscopic Organization of Long-Chain Rhodamine Molecules in Monolayers at the Air/Water Interface. J. Phys.Chem. B. 2002, 106, 4203–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthaler, M.J.E.; Meech, S.R. Picosecond Dynamics of Adsorbed Dyes: A Time-Resolved Surface Second-Harmonic Generation Study of Rhodamine 110 on Silica. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 3323–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R. Symmetry, Group Theory, and the Physical Properties of Crystals; Vol. 824, Springer, 2010; pp. 1–230. [CrossRef]

- Eckenrode, H.M.; Jen, S.h.; Han, J.; Yeh, A.g.; Dai, H.l. Adsorption of a Cationic Dye Molecule on Polystyrene Microspheres in Colloids: Effect of Surface Charge and Composition Probed by Second Harmonic Generation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Jia, Z.; Ma, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Q.; Ren, B.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y. Fabrication of graphene oxide/polydopamine adsorptive membrane by stepwise in-situ growth for removal of rhodamine B from water. Desalination 2021, 516, 115220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardana, M.K.; Disanayaka, H.N.; Fernando, M.S.; de Silva, K.N.; de Silva, R.M. Development of graphene oxide-based polypyrrole nanocomposite for effective removal of anionic and cationic dyes from water. Results. Chem. 2023, 6, 101079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Li, Y.; Mandal, B.; Kang, S.G.; Hur, S.H.; Chung, J.S. Selective adsorption of organic dyes on graphene oxide: Theoretical and experimental analysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 464, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, X.; Ma, K.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of graphene oxide/4A molecular sieve composite and evaluation of adsorption performance for Rhodamine B. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 286, 120400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalsabila, A.; Dabur, V.A.; Budiarso, I.J.; Wustoni, S.; Chen, H.C.; Birowosuto, M.D.; Wibowo, A.; Zeng, S. Progress and Outlooks in Designing Photonic Biosensor for Virus Detection. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2400849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).