1. Introduction

Physical activity's positive effects on healthy and unhealthy individuals are well-documented, demonstrating the adaptation of biological systems such as the circulatory, respiratory, and muscular systems to stress [

1]. These adaptations directly influence athletic performance and the ability to excel in specific physical skills [

2]. Training induces modifications at the tissue and cellular levels, which are influenced by variations in local gene expression [

3]. Specific genetic variants play a pivotal role in determining excellence in traits such as speed, muscle strength, injury predisposition, and emotional control. Recently, the interest in the role of genetics in sports performance has grown, with studies exploring how particular genetic variations influence physical abilities, endurance, strength, and psychological traits [

4].

Performance-enhancing polymorphisms (PEPs) are genetic variations that influence athletic traits such as endurance, muscle strength, power, flexibility, and other critical components of performance [

5]. Understanding these polymorphisms provides valuable insights for tailoring training programs to optimize individual genetic potential, including training adaptations and dietary strategies aligned with genetic predispositions [

6]. To identify these polymorphisms, Total Genetic Score (TGS) has emerged as a robust method for identifying an athlete’s genetic predisposition towards specific performance traits [

7]. By quantifying the combined effect of multiple PEPs, TGS streamlines the assessment of genetic profiles, enabling efficient comparisons and personalized recommendations. Athletes with training regimens aligned with their genetic predispositions achieve superior results compared to those whose training is mismatched with their genetic profiles [

8].

Specific genes such as Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme (ACE), Peroxisome Prolif-erator-Activated Receptors (PPARα), and Creatine Kinase Muscle-Type (CKM), have been identified as critical contributors to sports performance. The ACE gene, through its I/D polymorphism, influences endurance and strength: the "I" allele is linked to endurance activities like long-distance running, while the D allele correlates with strength-focused disciplines such as weightlifting. Similarly, PPARα, through the C/G polymorphism, affects lipid metabolism, inflammation, and tissue repair, with the G allele favoring endurance due to its association with slow-twitch muscle fibers and aerobic capacity, and the C allele favoring power-based sports [

9,

10]. The CKM gene, involved in muscle energy metabolism, demonstrates a similar dual influence, with the A allele associated with higher aerobic capacity and the G allele linked to greater muscle strength and power [

11,

12].

This study focuses on the importance of the genetic background in elite athletes, emphasizing the interaction between genetic and environmental factors in determining athletic success. By focusing on Point Fighting (PF) athletes, this research aims to fill a gap in the literature, exploring their genetic predispositions to support the development of tailored training strategies [

13]. The findings are expected to advance scientific knowledge and provide practical applications for optimizing individual performance in this discipline.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty-four PF elite athletes (12 women and 12 men) were enrolled in our study. The anthropometric characteristics of the participants are shown in

Table 1.

The study included elite athletes selected on their performance in top-level international competitions organized by the WAKO federation. Specifically, during 2018-2019, all participants had achieved a podium at European and World Championships in their respective weight categories.

The inclusion criteria specified that participants had to be high-level athletes with international experience, have passed a selection process based on their competitive results, and be free from musculoskeletal injuries that could impair performance during the study. Athletes who did not meet these criteria or had health conditions incompatible with the experimental procedures were excluded.

After signing informed consent, all athletes completed a questionnaire to collect anthropometric data and information about their weekly training habits. A saliva sample was then collected from each participant for genetic analysis to determine the allelic distribution of the analyzed genes. Finally, a standardized TGS was applied to the identified genotype to assess whether the athletes' genetic profiles were more oriented toward power or aerobic endurance.

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Novi Sad, Serbia (ref. no. 46-06-02/2020-2).

2.2. Total Genetic Score

The Total Genetic Score (TGS) we have chosen to apply for data analysis was power-oriented. Therefore, a score of "2" was attributed when the polymorphism was homozygous for the allele predisposing to power activities, "1" was attributed if it was heterozygous, and "0" when the polymorphism was homozygous for the allele predisposing to aerobic activities. The sum of the scores given to the polymorphism of each gene gives us the genotype score (GS) (maximum score = 6) [

16].

Table 2 shows the association between GS of each polymorphism and metabolic impact.

After identifying the GS for each gene polymorphism, the score was reformulated on a centesimal basis, obtaining the TGS. The formula used was TGS=GS*100/6 according to the formula which was validated by Hughes et al. [

18]. For example, subjects having the following genetic profile: ACE DD (2), PPARA CG (1) CKM AA (0) have a GS=3 and therefore TGS=50% power-oriented.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics 29 software and “Jamovi” software version “2.3.21.0” programs. Percentages were used to analyze the participant’s allelic distribution in the three genes. Data were expressed as percentages, means, and standard deviations.

2.4. DNA Extraction and Genotyping

From the saliva samples collected and stored at -20°, genomic DNA extraction was performed using a "Saliva DNA ISO isolation kit" from Norgen Biotek (Canada) according to the procedure already described in our previous study [

17].

Details regarding the protocol used for the genotyping by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are provided in

Table 3.

As described in

Table 4, two the polymorphisms analyzed required enzymatic digestion, and the fragments obtained were highlighted by the gel electrophoresis method [

18].

3. Results

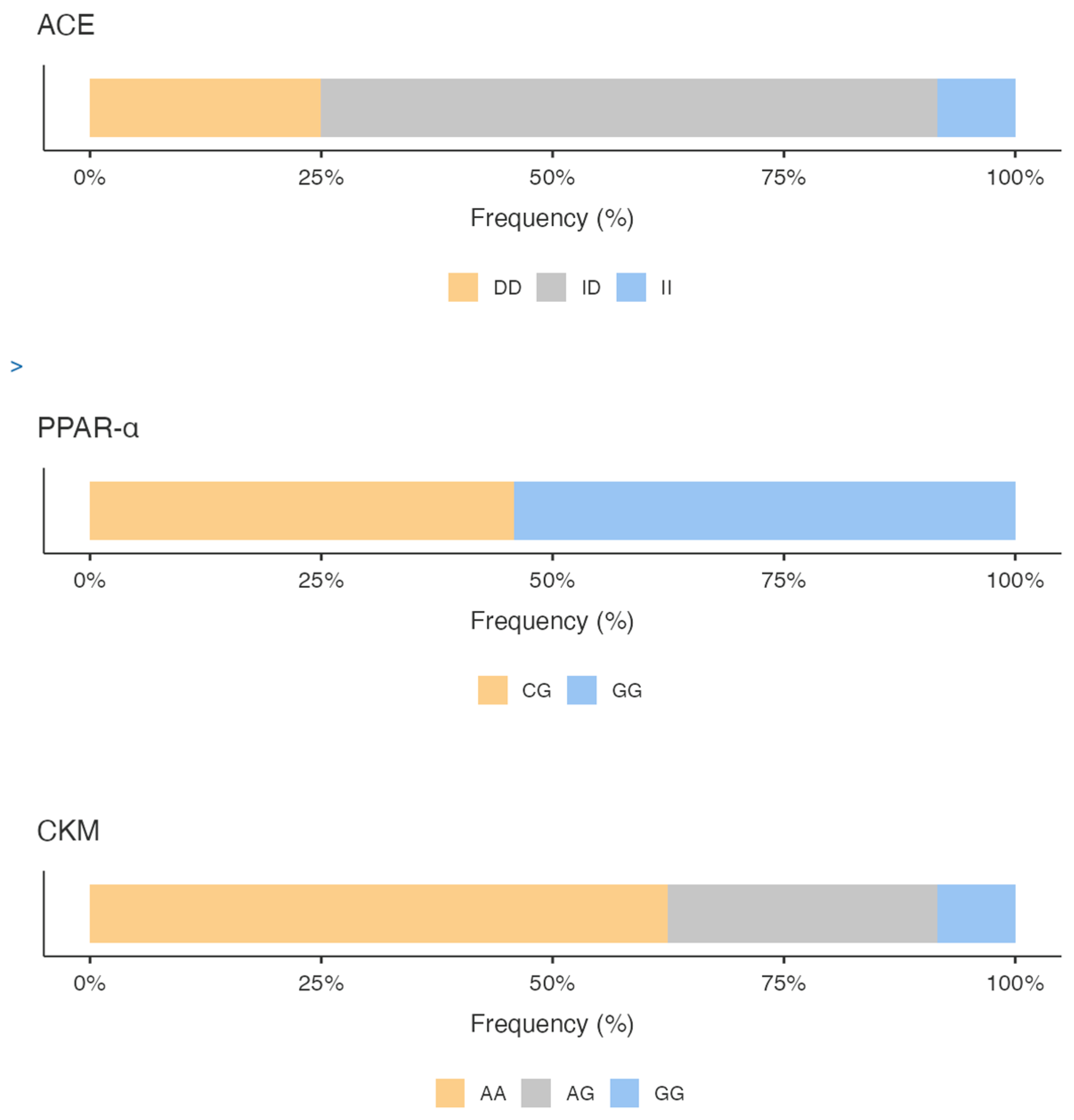

The genotyping results show for ACE gene, a predominance of ID genotype (66.67%), followed by DD genotype (25%) and II genotype (8.33%), with a higher expression frequency of the D allele versus I allele (58.33% vs 41.67%).

Regarding PPARα polymorphisms, we highlighted a prevalence of the GG genotype (54.17%), followed by the CG genotype (45.83%); no CC genotype was found. The G allele was much more common (77.08%) compared with 22.92% for the C allele.

As a concern, the CKM gene variant, the AA genotype, was found with 62.50% frequency compared AG genotype (29.17%) and GG genotype (8.33%). Analyzing the frequency of expression of the alleles, the A allele was the most common (77.08%) compared with the G allele (22.92%).

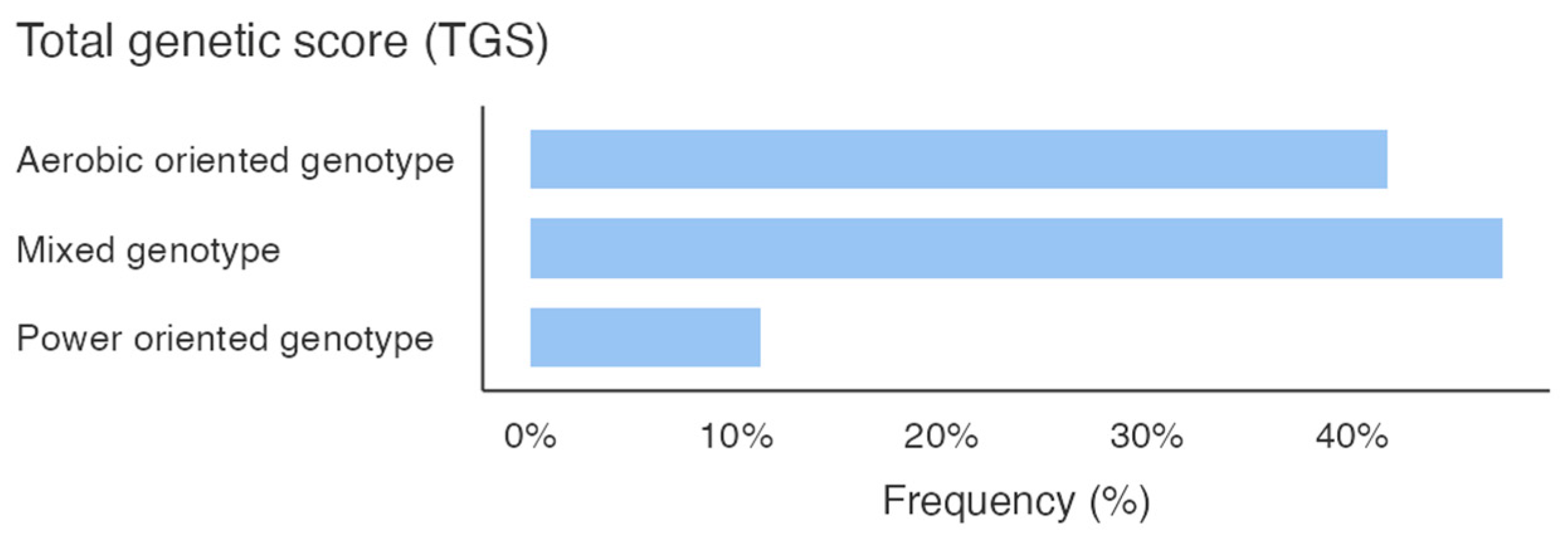

Figure 1 shows the percentage of the genotype distribution for the three gene variants in the whole sample; different colors emphasize the genotype that predisposes the athletes to the specific activity. Additionally, considering the total GS calculated by summing the GS of the allelic distribution for all three genes, it is pointed out that the sample scored higher mixed-oriented genotype 47% (

Figure 2). The athlete’s survey results showed that they spent an average of 367.3 ± 153.1 minutes weekly in technique training, 188.5 ± 122.3 minutes in strength training, and 134.8 ± 95.5 minutes in aerobic training (

Figure 2).

4. Discussions

The novelty of our study lies in identifying the genetic background of elite PF athletes through the application of TGS, emphasizing the importance of personalized training to enhance performance. The ability to align training with genetic predispositions provides a unique opportunity to maximize athletic potential in a scientifically informed manner.

Previous research has established that specific genetic variants significantly contribute to variations in power, endurance, and mixed activities. In this regard, the study by John and colleagues [

19] demonstrated the critical role of the ACE I/D polymorphism in physical performance. The ACE I allele, associated with lower ACE levels, facilitates vasodilation and increased oxygenated blood flow to active muscles [

20], conferring an advantage in endurance activities. Conversely, the ACE D allele correlates with greater strength, basal muscle volume, and a higher percentage of fast-twitch muscle fibers, favoring power sports [

9].

Our findings revealed a greater prevalence of the D allele (58.33%) among elite PF athletes, indicative of a genetic predisposition toward anaerobic activities. This genetic predisposition provides valuable insights for tailoring training strategies that enhance the anaerobic capabilities essential for point-fighting athletes. For instance, a focus on high-intensity interval training and strength-based exercises could maximize the advantages conferred by this allele. Additionally, these findings highlight the critical role of integrating targeted anaerobic exercises into training regimens for sports that rely heavily on explosive power and short-duration efforts, ensuring that athletes can fully leverage their genetic potential. Furthermore, the ID genotype (66.67%) predominated, suggesting a mixed capacity for both aerobic and anaerobic performance [

21]. These results highlight the genetic foundation supporting the high-intensity demands of point fighting while revealing the need for a balanced training approach.

Regarding the PPARα polymorphism, the G allele—associated with endurance—was the most frequent in our cohort (77.08%), aligning with findings from Kurtulus M. et al.,2023 [

11]. This observation underscores the importance of aerobic capacity in a sport traditionally considered anaerobic-dominant. The presence of this allele suggests that endurance training may be undervalued in current regimens and offers an avenue for performance enhancement.

For the CKM variant, while a previous study [

22] has linked the G allele to power and strength qualities, our study found a higher prevalence of the A allele (62.50%), indicating a genetic orientation toward aerobic performance. The reduced expression of power-oriented alleles (PPARα C and CKM G alleles) at approximately 22.92% suggests the need for training regimens that balance aerobic and anaerobic components, challenging the perception of PF as predominantly anaerobic. These genetic insights offer a pathway to refine training programs, focusing on versatility rather than specialization in anaerobic capacities.

Athlete surveys further underscored a preference for strength training over aerobic training (188.5 ± 122.3 vs. 134.8 ± 95.5 minutes per week). This imbalance could limit performance improvements by underutilizing the aerobic capacity identified in the genetic profiles of these athletes. A more balanced training approach, incorporating increased aerobic components, may better align with genetic predispositions and support overall performance optimization. This imbalance highlights a potential misalignment between genetic predisposition and training emphasis. Jones N. et al. (2016) emphasized the importance of aligning training modes with genetic profiles for optimal performance gains [

8]. Our sample’s higher mixed-oriented TGS score (

Figure 2) reinforces the necessity of addressing both aerobic and anaerobic demands. Consequently, increasing aerobic training may optimize performance, providing a more holistic approach to physical preparation.

Despite these strengths, this study has limitations. The sample size is relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, while genetic profiling offers valuable insights, performance outcomes are influenced by environmental factors and individual variability in response to training. Future studies should involve larger cohorts and longitudinal designs to validate these findings and refine training recommendations.

5. Conclusion

Our genetic analysis uncovered a high frequency of polymorphisms associated with combined aerobic and anaerobic performance in elite PF athletes. These findings have the potential to redefine training paradigms by emphasizing the necessity of a balanced approach that incorporates both aerobic and anaerobic components. This balance could enhance physical preparedness and adaptability in point-fighting and similar sports, where explosive power and sustained effort are equally critical for success. These results challenge the traditional view of PF as a predominantly anaerobic sport, emphasizing the significant role of aerobic capacity. The findings suggest that optimizing training regimens to align with genetic predispositions can enhance performance in this demanding discipline. The high prevalence of mixed-oriented genetic profiles highlights the need for a balanced training approach, integrating aerobic and anaerobic components. This perspective not only supports individual athletic development but also provides a foundation for refining coaching strategies in combat sports. Future research should prioritize large-scale genetic studies and explore redistributing training loads to enhance aerobic components. Such adjustments may further optimize performance, providing a comprehensive and scientifically grounded approach to training for elite PF athletes.

The high frequency of polymorphisms frequently associated with alternating aerobic/anaerobic performance, found in our genetic investigation in this group of elite athletes, could challenge the predominantly anaerobic acceptance of this sport, rather than affirming the co-relevance of the aerobic component. Probably one of the reasons that are not allowed to settle the dispute is the lack of cohort studies on a large genetic sample and the heterogeneity of the athletes considered [

19].

In conclusion, starting from our results of the informational questionnaire on the type of training predominantly done during the week and considering the results of the genetic survey, future studies should be geared toward investigating and redistributing the training load during the week in favor of aerobic activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and P.P.; Data curation, C.C.; Formal analysis, P.P.; Writing – original draft, A.P., A.A., A.B., P.P. and S.B.; Writing – review & editing, A.P., A.A., A.B., G.M., P.D., P.M., C.C., A.F., S.V., P.P. and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Novi Sad, Serbia (ref. no. 46-06-02/2020-2).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the elite Point Fighting athletes for their participation and the Department of Biological, Chemical, and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies (STEBICEF), University of Palermo, for their support in the genetic analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iannaccone, A., et al., Stay Home, Stay Active with SuperJump®: A Home-Based Activity to Prevent Sedentary Lifestyle during COVID-19 Outbreak. Sustainability, 2020. 12(23): p. 10135. [CrossRef]

- Amato, A., et al., Analysis of Body Perception, Preworkout Meal Habits and Bone Resorption in Child Gymnasts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021. 18(4): p. 2184.

- Widmann, M., A.M. Nieß, and B. Munz, Physical Exercise and Epigenetic Modifications in Skeletal Muscle. Sports Med, 2019. 49(4): p. 509-523. [CrossRef]

- Appel, M., et al., Effects of Genetic Variation on Endurance Performance, Muscle Strength, and Injury Susceptibility in Sports: A Systematic Review. Front Physiol, 2021. 12: p. 694411. [CrossRef]

- Varillas-Delgado, D., et al., Genetics and sports performance: the present and future in the identification of talent for sports based on DNA testing. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2022. 122(8): p. 1811-1830. [CrossRef]

- Semenova, E.A., E.C.R. Hall, and I.I. Ahmetov, Genes and Athletic Performance: The 2023 Update. Genes, 2023. 14(6): p. 1235. [CrossRef]

- Amato, A., et al., Total genetic score: An instrument to improve the performance in the elite athletes. Acta Medica Mediterranea, 2018.

- Jones, N., et al., A genetic-based algorithm for personalized resistance training. Biology of sport, 2016. 33(2): p. 117-126. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.H., et al., Impact of angiotension I converting enzyme gene I/D polymorphism on running performance, lipid, and biochemical parameters in ultra-marathoners. Medicine (Baltimore), 2019. 98(29): p. e16476. [CrossRef]

- Balberova, O.V., et al., Candidate Genes of Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Energy Metabolism in Athletes. Genes (Basel), 2021. 12(11). [CrossRef]

- Kurtuluş, M., et al., Genetic differences in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene in endurance athletes (long distance runners) and power/endurance athletes (wrestlers, football players). Journal of Basic and Clinical Health Sciences, 2023. 7(2): p. 723-730. [CrossRef]

- Olga1AB, F., et al., Association of muscle-specific creatine kinase (CKM) gene polymorphism with combat athlete status in Polish and Russian cohorts. Arch Budo, 2013. 3: p. 233-237.

- Batavani, M.R., et al., Comparison of muscle-specific creatine kinase (CK-MM) gene polymorphism (rs8111989) among professional, amateur athletes and non-athlete karatekas. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, 2017. 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Fedotovskaya, O., et al., Association of muscle-specific creatine kinase (CKMM) gene polymorphism with physical performance of athletes. Human Physiology, 2012. 38: p. 89-93. [CrossRef]

- Ahmetov, II, et al., Advances in sports genomics. Adv Clin Chem, 2022. 107: p. 215-263.

- Homma, H., et al., The Association between Total Genotype Score and Athletic Performance in Weightlifters. Genes (Basel), 2022. 13(11). [CrossRef]

- Amato, A., et al., Influence of nutrition and genetics on performance: a pilot study in a group of gymnasts. Human Movement, 2017. 18(3): p. 12-16. [CrossRef]

- Küchler, E.C., et al., Buccal cells DNA extraction to obtain high quality human genomic DNA suitable for polymorphism genotyping by PCR-RFLP and Real-Time PCR. J Appl Oral Sci, 2012. 20(4): p. 467-71. [CrossRef]

- John, R., M.S. Dhillon, and S. Dhillon, Genetics and the Elite Athlete: Our Understanding in 2020. Indian J Orthop, 2020. 54(3): p. 256-263. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N., et al., ACE Gene I/D Polymorphism and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Cross Sectional Study of Rural Population. Biochem Genet, 2024. 62(2): p. 1008-1020. [CrossRef]

- Gasser, B., et al., ACE-I/D Allele Modulates Improvements of Cardiorespiratory Function and Muscle Performance with Interval-Type Exercise. Genes (Basel), 2023. 14(5). [CrossRef]

- Cocci, P., et al., Genetic variants and mixed sport disciplines: a comparison among soccer, combat and motorcycle athletes. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 2019. 7(1): p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).