Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Location of the Study and Source of Samples

Blood Collection and DNA Isolation

Quality of Genomic DNA

ddRAD-Based Genotyping Library Preparation

SNP Identification and Quality Control for Diversity Analysis

Selection Sweep Identification

3. Results

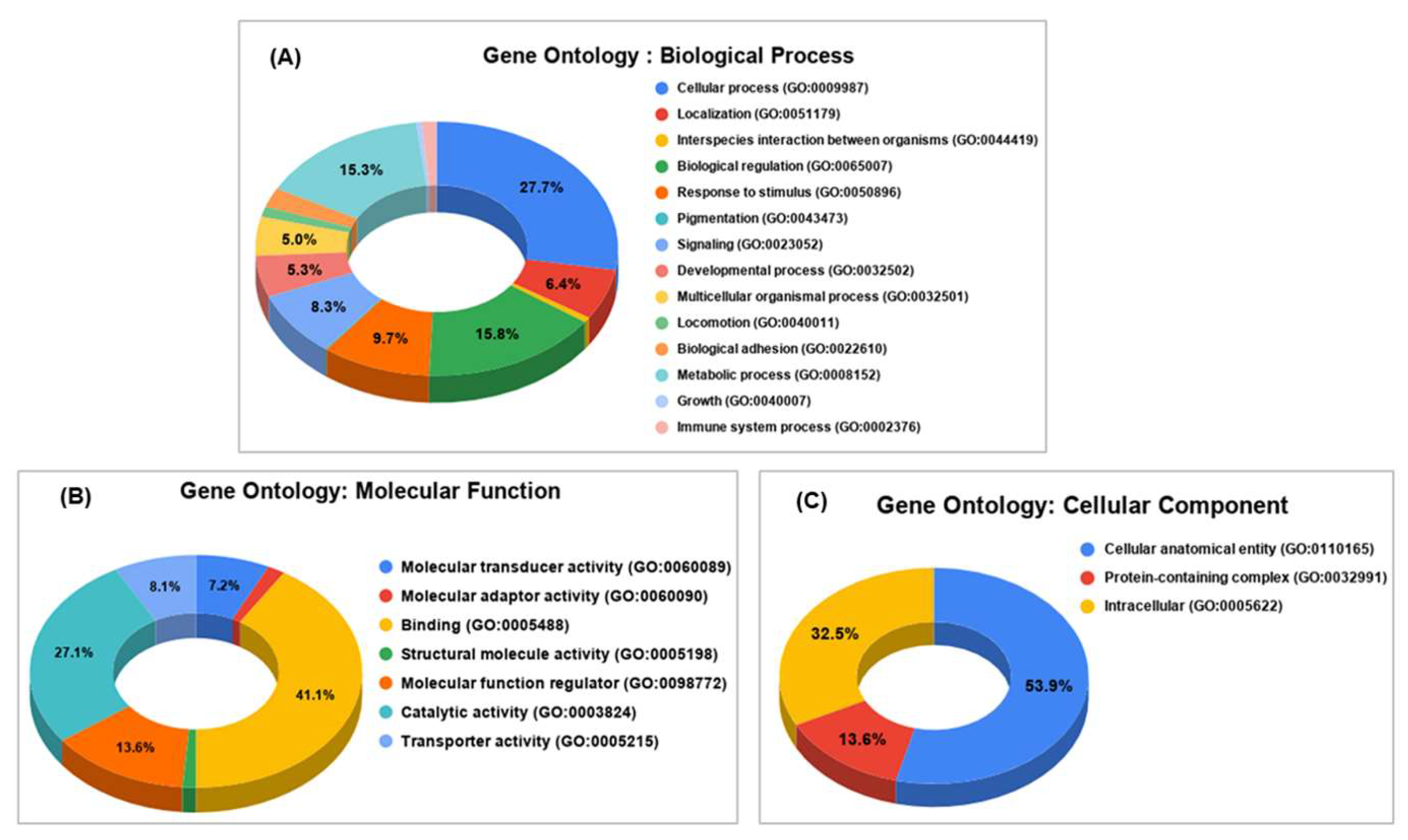

3.1. Genome-Wide Annotation of SNPs

3.2. Gene-Wise Mapping of SNPs and Indels

3.3. Selection Sweeps

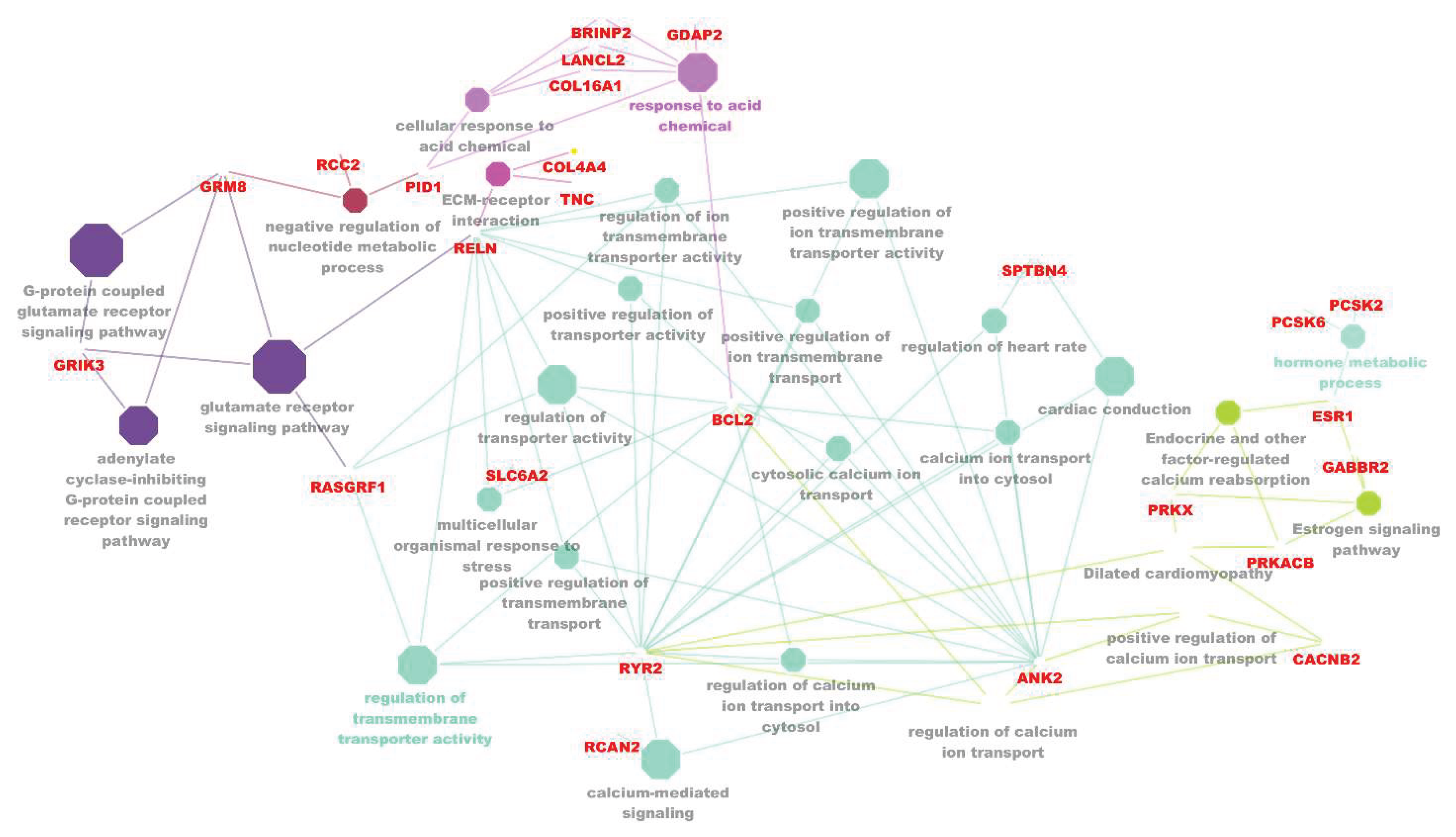

3.4. Gene-Gene Interaction Network Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ddRAD-Seq | Double Digest Restriction Associated DNA (ddRAD) Sequencing |

| GBS | Genotyping By Sequencing |

| MAS | Marker-Assisted Selection |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

References

- Livestock Census. Government of India, 20th Livestock Census-2019. Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry & Dairying; Department of animal husbandry and dairying, Krishi Bhawan, New Delhi, 2019. accessible at: http://dadf.gov.in/sites/default/filess/Key%20Results%2BAnnexure%2018.10.2019.pdf.

- McSweeney C, Mackie R. Micro-organisms and ruminant digestion: state of knowledge, trends and future prospects. Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. 61 1-62. 2012. Accessed on 04 April 2021, available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/016/me992e/me992e.pdf.

- Pal Y, Sharma P, Bhardwaj A et al. Agri-entrepreneurship development through equines, in: P. Kashyap, A.K. Prusty, A.S. Panwar, S. Kumar, P. Punia, N. Ravisankar & V. Kumar (Eds.). Agri-Entrepreneurship Challenges and Opportunities, Today and tomorrow’s printers and publishers, New Delhi, pp. 165-176.(2019).

- Pal Y, et al. "Phenotypic characterization of Kachchhi-Sindhi horses of India." Indian Journal of Animal Research 55.11 (2021): 1371-1376.

- Pal, Yash, et al. "Status and conservation of equine biodiversity in India." Indian Journal of Comparative Microbiology, Immunology and Infectious Diseases 41.2 (2020): 174-184.

- Gupta, AK, et al. "Phenotypic characterization of Indian equine breeds: a comparative study." Animal Genetic Resources/Resources génétiques animales/Recursos genéticos Animales 50 (2012): 49-58.

- Gupta AK, Chauhan M, Bhardwaj A, et al. Microsatellite markers based genetic diversity and bottleneck studies in Zanskari pony. Gene. 2012;499(2):357-361.

- Gupta AK, Chauhan M, Bhardwaj A, et al. Comparative genetic diversity analysis among six Indian breeds and English Thoroughbred horses. Livestock Science. 2014;163:1-11.

- Gupta AK, Chauhan M, Bhardwaj A. Genetic diversity and bottleneck studies in endangered Bhutia and Manipuri pony breeds. Molecular Biology Reports. 2013;40(12):6935-6943.

- Gupta AK, Chauhan M, Bhardwaj A, et al. Assessment of demographic bottleneck in Indian horse and endangered pony breeds. Journal of Genetics. 2015;94(2):56-62.

- Gupta, A. K., Kumar, S., Pal, Y., Bhardwaj, A., Chauhan, M., & Kumar, B. (2018). Genetic diversity and structure analysis of donkey population clusters in different Indian agro-climatic regions. J Biodivers Endanger Species, 6(006), 2.

- Pal, Y., Legha, R. A., Lal, N., Bhardwaj, A., Chauhan, M., Kumar, S., ... & Gupta, A. K. (2013). Management and phenotypic characterization of donkeys of Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, 83(8), 793-797.

- Gupta, A. K., Kumar, S., Sharma, P., Pal, Y., Dedar, R. K., Singh, J., ... & Kumar, B. (2016). Biochemical profiles of Indian donkey population located in six different agro-climatic zones. Comparative Clinical Pathology, 25, 631-637.

- Gupta, A., Bhardwaj, A., Sharma, P., Pal, Y., & Kumar, M. (2015). Mitochondrial DNA-a tool for phylogenetic and biodiversity search in equines. J Biodivers Endanger Species, 1(006).

- Peterson BK, Weber JN, Kay EH, et al. Double Digest RADseq: An Inexpensive Method for De Novo SNP Discovery and Genotyping in Model and Non-Model Species. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37135.

- Pérez-Enciso M. Genomic relationships computed from either next-generation sequence or array SNP data. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics. 2014;131(2):85-96.

- Pérez-Enciso M, Rincón JC, Legarra A. Sequence- vs. chip-assisted genomic selection: accurate biological information is advised. Genetics Selection Evolution. 2015;47(1):43.

- Pérez-Enciso M, Steibel JP. Phenomes: the current frontier in animal breeding. Genetics Selection Evolution. 2021;53(1):22.

- Stella A, Ajmone-Marsan P, Lazzari B, et al. Identification of Selection Signatures in Cattle Breeds Selected for Dairy Production. Genetics. 2010;185(4):1451-1461.

- Xu L, Bickhart DM, Cole JB, et al. Genomic Signatures Reveal New Evidences for Selection of Important Traits in Domestic Cattle. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2015;32(3):711-725.

- Gurgul A, Miksza-Cybulska A, Szmatoła T, et al. Genotyping-by-sequencing performance in selected livestock species. Genomics. 2019;111(2):186-195.

- De Donato M, Peters SO, Mitchell SE, et al. Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS): A Novel, Efficient and Cost-Effective Genotyping Method for Cattle Using Next-Generation Sequencing. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62137.

- Sivalingam J, Vineeth MR, Surya T, et al. Genomic divergence reveals unique populations among Indian Yaks. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):3636.

- Pértille F, Guerrero-Bosagna C, Silva VH, et al. High-throughput and Cost-effective Chicken Genotyping Using Next-Generation Sequencing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26929.

- Zhu Z, Miao Z, Chen H, et al. Ovarian transcriptomic analysis of Shan Ma ducks at peak and late stages of egg production. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2017;30(9):1215-1224.

- Tezuka A, Takasu M, Tozaki T, et al. Genetic analysis of Taishu horses on and off Tsushima Island: Implications for conservation. Journal of Equine Science. 2019;30(2):33-40.

- Sambrook J, Russell D. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2001. (Ed. 3).

- Schmieder R, Edwards R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(6):863-864.

- Catchen JM, Amores A, Hohenlohe P, et al. Stacks: Building and Genotyping Loci De Novo From Short-Read Sequences. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2011;1(3):171-182.

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods. 2012;9(4):357-359.

- Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(15):2156-2158.

- Pavlidis P, Živković D, Stamatakis A, et al. SweeD: Likelihood-Based Detection of Selective Sweeps in Thousands of Genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30(9):2224-2234.

- Kuhn RM, Haussler D, Kent WJ. The UCSC genome browser and associated tools. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2013;14(2):144-161.

- Thomas PD, Campbell MJ, Kejariwal A, et al. PANTHER: a library of protein families and subfamilies indexed by function. Genome Res. 2003;13(9):2129-41.

- Otasek D, Morris JH, Bouças J, et al. Cytoscape Automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biology. 2019;20(1):185.

- Sharma NK, Prashant S, Bibek S, et al. Genome wide landscaping of copy number variations for horse inter-breed variability. Animal Biotechnology. 2025;36(1):2446251.

- Bhardwaj A, Tandon G, Pal Y, et al. Genome-Wide Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism-Based Genomic Diversity and Runs of Homozygosity for Selection Signatures in Equine Breeds. Genes. 2023;14(8):1623.

- Saito M, Goto A, Abe N, et al. Decreased expression of CADM1 and CADM4 are associated with advanced stage breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(2):2401-2406.

- Wikman H, Westphal L, Schmid F, et al. Loss of CADM1 expression is associated with poor prognosis and brain metastasis in breast cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2014;5(10):3076-87.

- Liu Y, Wang D-K, Jiang D-Z, et al. Cloning and Functional Characterization of Novel Variants and Tissue-Specific Expression of Alternative Amino and Carboxyl Termini of Products of Slc4a10. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55974.

- Lee W, Park KD, Taye M, et al. Analysis of cross-population differentiation between Thoroughbred and Jeju horses. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2018;31(8):1110-1118.

- Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, et al. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(11):a003996.

- Wehrens XHT, Lehnart SE, Huang F, et al. FKBP12.6 Deficiency and Defective Calcium Release Channel (Ryanodine Receptor) Function Linked to Exercise-Induced Sudden Cardiac Death. Cell. 2003;113(7):829-840.

- Brard S, Ricard A. Genome-wide association study for jumping performances in French sport horses. Animal Genetics. 2015;46(1):78-81.

- Huq AJ, Pertile MD, Davis AM, et al. A Novel Mechanism for Human Cardiac Ankyrin-B Syndrome due to Reciprocal Chromosomal Translocation. Heart, Lung and Circulation. 2017;26(6):612-618.

- Swayne LA, Murphy NP, Asuri S, et al. Novel Variant in the ANK2 Membrane-Binding Domain Is Associated With Ankyrin-B Syndrome and Structural Heart Disease in a First Nations Population With a High Rate of Long QT Syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(1).

- Imahashi K, Schneider MD, Steenbergen C, et al. Transgenic expression of Bcl-2 modulates energy metabolism, prevents cytosolic acidification during ischemia, and reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2004;95(7):734-41.

- Kobayashi S, Lackey T, Huang Y, et al. Transcription factor GATA4 regulates cardiac BCL2 gene expression in vitro and in vivo. The FASEB Journal. 2006;20(6):800-802.

- Jafari, Afshar, et al. "Effect of exercise training on Bcl-2 and bax gene expression in the rat heart." Gene, Cell and Tissue 2.4 (2015): e32833.

- Corrêa MJM, da Mota MDS. Genetic evaluation of performance traits in Brazilian Quarter Horse. Journal of Applied Genetics. 2007;48(2):145-151.

- Carobrez, Antonio de Pádua. "Transmissão pelo glutamato como alvo molecular na ansiedade." Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 25 (2003): 52-58.

- Murphy J, Arkins S. Equine learning behaviour. Behavioural Processes. 2007;76(1):1-13.

- Marinier SL, Alexander AJ. The use of a maze in testing learning and memory in horses. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1994;39(2):177-182.

- Ceglia L. Vitamin D and skeletal muscle tissue and function. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2008;29(6):407-414.

- Hopkinson NS, Li KW, Kehoe A, et al. Vitamin D receptor genotypes influence quadriceps strength in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease2. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87(2):385-390.

- Schröder W, Klostermann A, Distl O. Candidate genes for physical performance in the horse. The Veterinary Journal. 2011;190(1):39-48.

- Gu J, Orr N, Park SD, et al. A Genome Scan for Positive Selection in Thoroughbred Horses. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5767.

| Breed | Genetic variants | RD02 | RD05 | RD10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indian Horses Combined (n=76) | SNPs | 328106 | 311554 | 298782 |

| Indels | 27027 | 25108 | 23950 | |

| Total variants | 355133 | 336662 | 322732 | |

| Kachchhi-Sindhi (n=24) |

SNPs | 217785 | 210007 | 203071 |

| Indels | 17094 | 16210 | 15629 | |

| Total variants | 234879 | 226217 | 218700 | |

| Kathiawari (n=17) |

SNPs | 185631 | 177773 | 170395 |

| Indels | 14858 | 14155 | 13469 | |

| Total variants | 200489 | 191928 | 183864 | |

| Manipuri (n=5) |

SNPs | 136117 | 129558 | 118801 |

| Indels | 10190 | 9697 | 8707 | |

| Total variants | 146367 | 139255 | 127508 | |

| Marwari (n=25) |

SNPs | 210509 | 203049 | 196199 |

| Indels | 16503 | 15841 | 15322 | |

| Total variants | 220712 | 218890 | 211521 | |

| Zanskari (n=5) |

SNPs | 151870 | 146329 | 138934 |

| Indels | 11292 | 10759 | 10135 | |

| Total variants | 163162 | 157008 | 149069 | |

| Thoroughbred (n=15) |

SNPs | 148913 | 144008 | 138022 |

| Indels | 12089 | 11688 | 11112 | |

| Total variants | 161002 | 155696 | 149134 |

| Functions | Candidate genes | SNPs | Indels | Role | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racing Performance | PDZRN3 (PDZ domain-containing RING finger protein 3 ) | 30 | 14 | Differentiation of myoblasts | Ko et al.,2006 |

| Racing Performance | ARL15 (ADP-ribosylation factor-like 15) | 16 | 8 | Regulator of myoblast fusion | Bach et al.,2010 |

| Racing Performance | CNTN3 (Contactin 3) | 20 | 4 | Muscle maintenance | Jelinsky et al.,2010 |

| Racing Performance | CCT5 (Chaperonin Containing TCP1 Subunit 5) | 2 | 2 | Muscle maintenance | Kim et al.,2008 |

| Racing Performance | VARS2 (Valyl-TRNA Synthetase 2, Mitochondrial) | 6 | - | Muscle maintenance | Shin et al.,2015 |

| Racing Performance | INPP5J (Inositol Polyphosphate-5-Phosphatase J) | 2 | - | Muscle maintenance | Shin et al.,2015 |

| Racing Performance | SORCS3 (Sortilin Related VPS10 Domain Containing Receptor 3) | 42 | 26 | Endurance and speed | Velie et al.,2019;Ricard et al.,2017 |

| Racing Performance | SLC39A2 (Solute Carrier Family 39 Member 2 ) | 10 | 10 | Endurance and speed | Ricard et al.,2017 |

| Racing Performance | CCDC148 (Coiled-Coil Domain Containing 148) | 12 | 16 | Speed index | Meira et al.,2014 |

| Racing Performance | TNR (Tenascin R) | 24 | 6 | Maintain muscle integrity | Gu et al.,2009 |

| Racing Performance | TNC (tenascin C) | 10 | 4 | Maintain muscle integrity | Gu et al.,2009 |

| Racing Performance | SHQ1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | 6 | 10 | Differentiation of myoblasts | Shin et al.,2015 |

| Morphology and Skeletal Development | WWOX (WW Domain Containing Oxidoreductase) | 74 | 28 | Weight and Rump length | Meira et al.,2014(b) |

| Morphology and Skeletal Development | Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) | 14 | 20 | Osteoblastic differentiation and Skeletal morphology | Meira et al.,2014(b) |

| Morphology and Skeletal Development | Collagen alpha-1(XXVII) chain precursor | 12 | 16 | Cartilage calcification | Pereira et al.,2018 |

| Morphology and Skeletal Development | ZFAT (Zinc Finger And AT-Hook Domain Containing) | 12 | 6 | Wither height | Signer-Hasler et al.,2012 |

| Morphology and Skeletal Development | LCORL (ligand-dependent nuclear receptor corepressor-like) | 6 | 4 | Wither height | Tetens et al.,2013 |

| Morphology and Skeletal Development | HNRNPU (Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein U) | 12 | 16 | Muscle development | Pereira et al.,2019 |

| Neural regulation | GRM8 ((Glutamate receptor, Metabotropic 8) | 48 | 18 | Neural transmitter; Behavioural and learning process | Meira et al.,2014 ; Murphy and Arkins.,2007 |

| Neural regulation | GRIK2 (Glutamate Receptor, Ionotropic, Kainate 2) | 34 | 16 | Neural transmitter; Behavioural and learning process | Meira et al.,2014 ; Murphy and Arkins.,2007 |

| Neural regulation | RXRA (Retinoid X receptor alpha) | 4 | 14 | Ocular and CNS development | Girardi et al.,2019 |

| Neural regulation | RYBP (RING1 and YY1 binding protein) | 4 | 14 | Ocular and CNS development | Pirity et al.,2007 |

| Immunity | RC3H2(Roquin 2) | 2 | 14 | Regulate inflammatory signals | Schaefer & Klein ,2016 |

| Immunity | STAT3 (Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) | 4 | 10 | Anti-inflammatory response | Leise et al.,2012 |

| Reproduction | STRBP (Spermatid perinuclear RNA-binding protein) | 4 | 10 | Spermatid and Spermatogenesis | Meng et al.,2018 |

| Energy metabolism | COX4I1 (Cytochrome C Oxidase Subunit 4I1) | 2 | 4 | Oxidative phosphorylation | Ricard et al.,2017 |

| Energy metabolism | CBLB (Cbl Proto-Oncogene B) | 4 | 2 | Insulin signalling | Gurgul et al.,2019 |

| Energy metabolism | PPARGC1A(Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α) | 4 | 4 | oxidative energy metabolism | Eivers et al.,2012 |

| Cardiac development | ANK1 (ankyrin 1, erythrocytic) | 38 | 18 | Cardiac muscle homeostasis; calcium mediation | Meira et al.,2014 |

| Lipid metabolism, | ACACA | 2 | 14 | Fatty acid synthesis | Dharuri et al.,2014 |

| Sl. No | Chromosome | Gene Name | No. of selection signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | Solute Carrier Family 4 Member 10 (SLC4A10) | 15 |

| 2 | 7 | Cell adhesion molecule 1 (CADM1) | 12 |

| 3 | 13 | Autism susceptibility gene 2 (AUTS2) | 12 |

| 4 | 13 | LOC733058 | 10 |

| 5 | 7 | Zinc Finger protein 94 (ZFP94) | 8 |

| 6 | 1 | Zinc Finger Protein 658 (ZFP658) | 7 |

| 7 | 1 | General Transcription Factor IIA Subunit 2(GTF2A2) | 6 |

| 8 | 5 | Ganglioside-Induced Differentiation Associated Protein 2 (GDAP2) | 6 |

| 9 | 11 | Galectin 9 (LGALS9) | 6 |

| 10 | 14 | Erythrocyte Membrane Protein Band 4.1 Like 4a (EPB41L4A) | 6 |

| Sl. No | Name of Pathway | No of genes involved | Genes list |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wnt signalling pathway (P00057) | 10 | CDH10, PCDH15, FAT1, CDH20, PCDH9, CDH8, FAT2, PRKCQ, ARID1B, CTNNA3 |

| 2 | Cadherin signalling pathway (P00012) | 8 | CDH10, PCDH15, FAT1, CDH20, PCDH9, CDH8, FAT2, CTNNA3 |

| 3 | Metabotropic glutamate receptor group III pathway (P00039) | 6 | GRM4, GRIK3, GRM8, PRKX, PRKACA, GRM7 |

| 4 | Heterotrimeric G-protein signalling pathway- Gq alpha and Go alpha mediated pathway (P00027) | 6 | GRM4, RGS7, GRM8, RGS6, PRKACA, GRM7 |

| 5 | Heterotrimeric G-protein signalling pathway- Gi alpha and Gs alpha mediated pathway (P00026) | 6 | GRM4, GRIK3, GRM8, PRKCQ, RGS6, GRM7 |

| 6 | Beta2 adrenergic receptor signalling pathway (P04378) | 5 | CACNAID, RYR2, PRKX, CACNB2, PRKACA |

| 7 | EGF receptor signalling pathway (P00018) | 5 | MRPL38, NRG4, PRKCQ, RASAL2, NRG2 |

| 8 | CCKR signalling map (P06959) | 5 | TCF4, RYR2, BCL2, PRKCQ, PRKACA |

| 9 | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signalling pathway (P00044) | 4 | MYO10, CACNA1D, CACNB2, CHRNA7 |

| 10 | Angiogenesis (P00005) | 3 | EPHB2, PRKCQ, EPHB1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).