Submitted:

18 October 2023

Posted:

19 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Methods

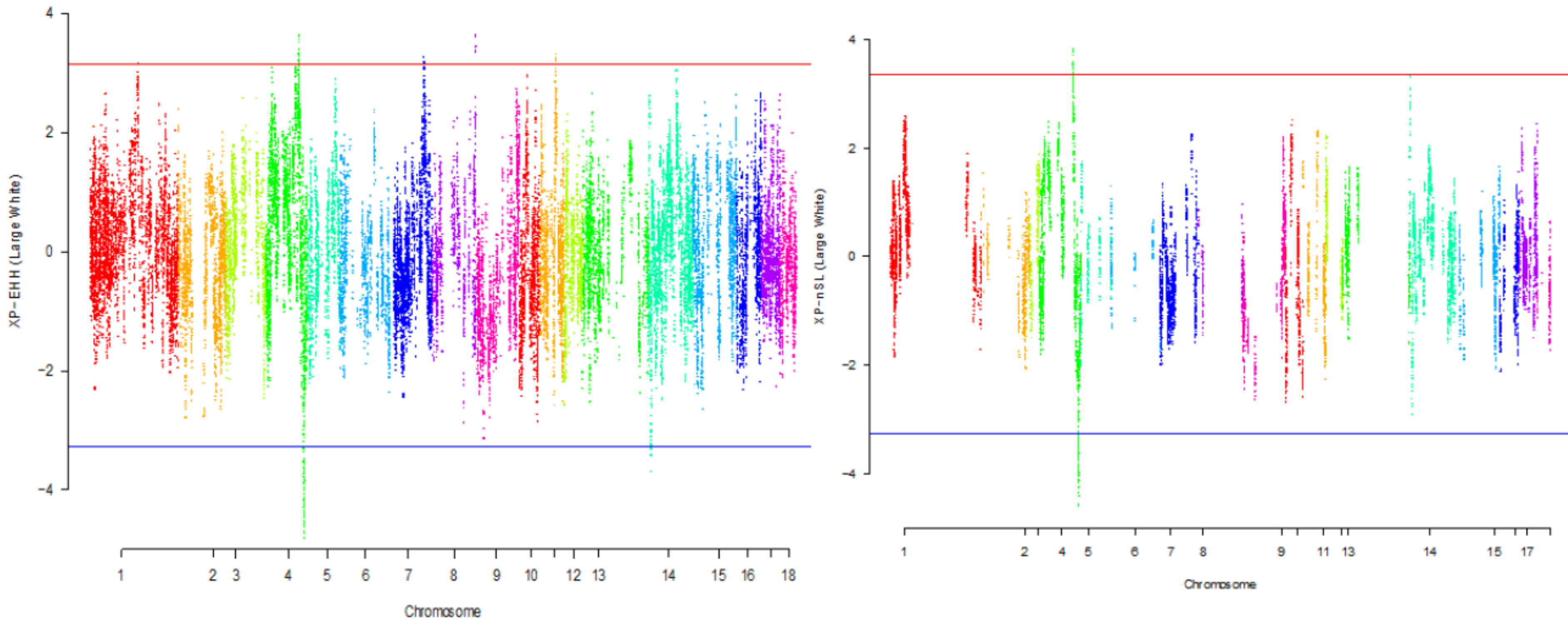

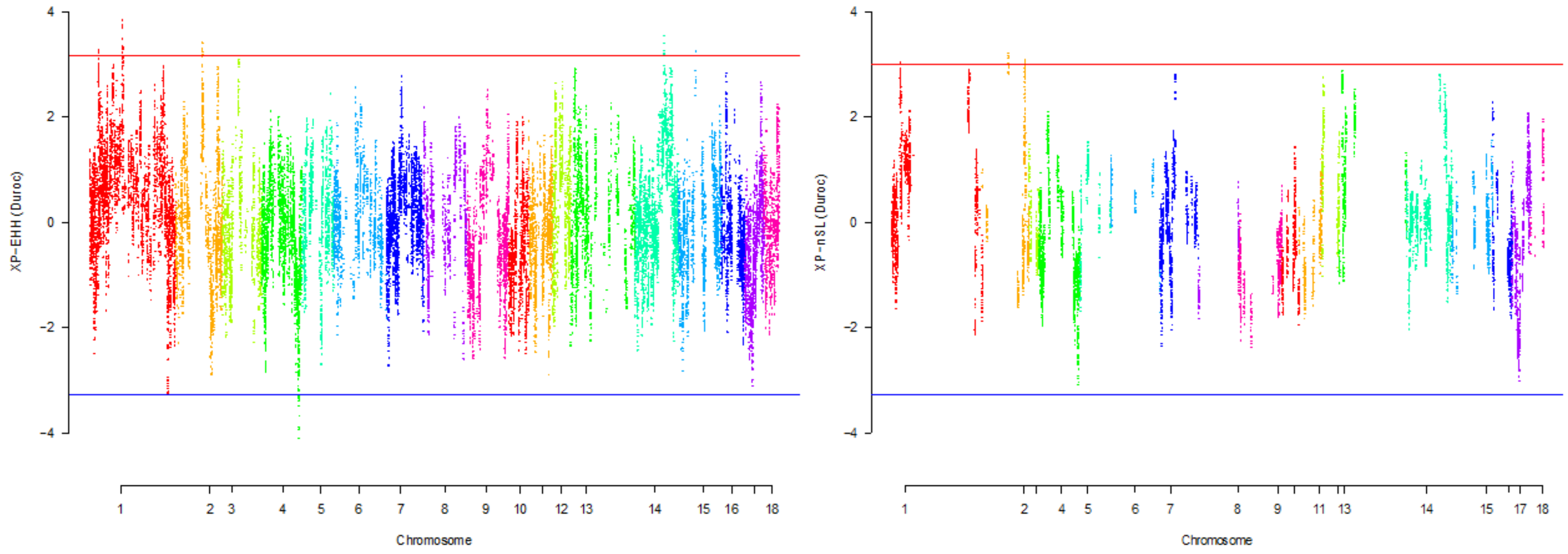

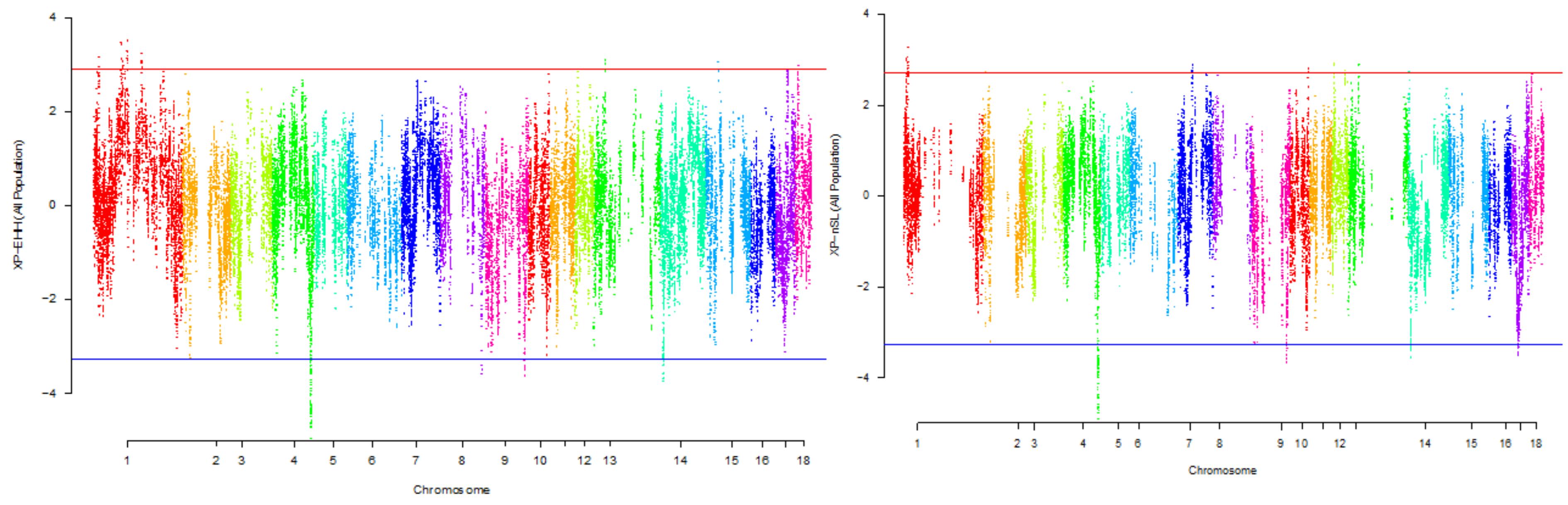

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, F.; McParland, S.; Kearney, F. et al. Detection of selection signatures in dairy and beef cattle using high-density genomic information. Genet Sel Evol 47, 49 (2015).

- Gonzalez-Dieguez, D.; Tusell, L.; Bouquet, A.; Legarra, A.; Vitezica, Z.G. Purebred and Crossbred Genomic Evaluation and Mate Allocation Strategies To Exploit Dominance in Pig Crossbreeding Schemes. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 10, 2829-41 (2020).

- Hermisson, J.; Pennings, P.S. Soft sweeps: molecular population genetics of adaptation from standing genetic variation. Genetics 169, 2335-52 (2005).

- . Zanella, R.; Peixoto, J.O.; Cardoso, F.F.; Cardoso, L.L.; Biegelmeyer, P.; Cantão, M.E.; Otaviano, A.; Freitas, M.S.; Caetano, A.R.; Ledur, M.C. Genetic diversity analysis of two commercial breeds of pigs using genomic and pedigree data. Genetics Selection Evolution 48, 1-10 (2016).

- Sabeti, P.C.; Varilly, P.; Fry, B.; Lohmueller, J.; Hostetter, E.; Cotsapas, L.; Brooks, L.D. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 449, 913-8 (2007).

- Grossman, S.R.; Shylakhter, I.; Karlsson, E.K.; Byrne, E.H.; Morales, S.; Frieden, G.; Hostetter, E.; Angelino, E.; Garber, M.; Zuk, O. A composite of multiple signals distinguishes causal variants in regions of positive selection. Science 327, 883-6 (2010).

- Eydivandi, S.; Roudbar, M.A.; Ardestani, S.S.; Momen, M.; Sahana, G. A selection signatures study among Middle Eastern and European sheep breeds. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics 138, 574-88 (2021).

- Yang, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Du, H.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Jing, X.; Yang, H. Population Genetic Structure and Selection Signature Analysis of Beijing Black Pig. Frontiers in genetics 13 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szpiech, Z.A.; Novak, T.E.; Bailey, N.P.; Stevison, L.S. Application of a novel haplotype-based scan for local adaptation to study high-altitude adaptation in rhesus macaques. Evolution letters 5, 408-21 (2021).

- Szpiech, Z.A.; Hernandez, R.D. selscan: an efficient multithreaded program to perform EHH-based scans for positive selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 31, 2824–2827 (2014).

- Browning, B.L.; Tian, X.; Zhou, Y.; Browning, S.R. Fast two-stage phasing of large-scale sequence data. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 108(10), 1880-90 (2021).

- Kim, E.S.; Elbeltagy, A.R.; Aboul-Naga, A.M.; Rischkowsky, B.; Sayre, B.; Mwacharo, J.M.; Rothschild, M.F. Multiple genomic signatures of selection in goats and sheep indigenous to a hot arid environment. Heredity 116(3), 255-64 (2016).

- Santana, M.H.d.A.; Ventura, R.V.; Utsunomiya, Y.T.; Neves, H.H.d.R.; Alexandre, P.A.; Oliveira Junior, G.A.; Gomes, R.d.C.; Bonin, M.d.N.; Coutinho, L.L.; Garcia, J.F. A genomewide association mapping study using ultrasound-scanned information identifies potential genomic regions and candidate genes affecting carcass traits in Nellore cattle. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics 132, 420-7 (2015).

- Ding, Rongrong, et al. "Single-locus and multi-locus genome-wide association studies for intramuscular fat in Duroc pigs." Frontiers in genetics 10 (2019): 619.

- Hinkle, Emma R., et al. "RNA processing in skeletal muscle biology and disease." Transcription 10.1 (2019): 1-20.

- Wu, Shanshan, et al. "Disrupted potassium ion homeostasis in ciliary muscle in negative lens-induced myopia in Guinea pigs." Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Volume 688, 2020,108403.

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, Q.; Li, M.; Lu, S. Identification of Potential Sex-Specific Biomarkers in Pigs with Low and High Intramuscular Fat Content Using Integrated Bioinformatics and Machine Learning. Genes 14(9), 1695 (2023).

- Fontanesi, L. et al. A genomewide association study for average daily gain in Italian Large White pigs. Journal of Animal Science, Volume 92, Issue 4, April 2014, Pages 1385–1394.

- AL_Rayyan, N.; Wankhade, UD.; Bush, K.; Good, DJ. Two single nucleotide polymorphisms in the human nescient helix-loop-helix 2 (NHLH2) gene reduce mRNA stability and DNA binding. Gene 512(1), 134-42 (2013).

- Zhang, H.; Xia, P.; Feng, L.; Jia, M.; Su, Y. Feeding frequency modulates the intestinal Transcriptome without affecting the gut microbiota in pigs with the same daily feed intake. Frontiers in Nutrition 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi, M.; Maltecca, C.; Schillebeeckx, C.; McNulty, NP.; Schwab, C.; Shull, C.; Fix, J.; Tiezzi, F. Heritability and genome-wide association of swine gut microbiome features with growth and fatness parameters. Scientific reports 10(1), 10134 (2020).

- Wang, X.; Li, G.; Ruan, D.; Zhuang, Z.; Ding, R.; Quan, J.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, J.; Gu, T.; Hong, L. Runs of homozygosity uncover potential functional-altering mutation associated with body weight and length in two Duroc pig lines. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Plastow, G.; Zhang, C.; Xu, S.; Hu, Z.; Yang, T.; Wang, K.; Yang, H.; Yin, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z. Genome-wide association study identifies candidate genes for piglet splay leg syndrome in different populations. BMC genetics 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dervishi, E.; Bai, X.; Dyck, MK.; Harding, JC.; Fortin, F.; Dekkers, JC.; Plastow, G. GWAS and genetic and phenotypic correlations of plasma metabolites with complete blood count traits in healthy young pigs reveal implications for pig immune response. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene name | Chromosome number | Position |

| DPYD PTBP2 ATP1A1 |

4 | 119931414:120712459 |

| 4 | 120961381:121041802 | |

| 4 | 104353508:104384547 | |

| CASQ2 CD2 |

4 | 104918501:104983607 |

| 4 | 103963345:103977292 | |

| IGSF3 MAB21L3 NHLH2 SLC22A15 |

4 | 103994390:104166988 |

| 4 | 104599818:104625234 | |

| 4 | 104857635:104858042 | |

| 4 | 104664015:104755672 | |

| VANGL1 ARSB |

4 | 104996073:105048775 |

| 2 | 87614963:87778447 |

| Comparing Breed and methods | Common Genes | ||

| Xpehh | Xp-Nsl | Between Xpehh and XpNsl | |

| Large White(Between two methods) | - | - | DPYD, PTBP2, ATP1A1, CASQ2, CD2, IGSF3, MAB21L3, NHLH2 SLC22A15,VANGL1 |

| Large White and Duroc | DPYD, PTBP2 | PTBP2 | PTBP2 |

| Large White and Pietrain | DPYD, PTBP2 | DPYD, PTBP2 | DPYD, PTBP2 |

| Large White and Landrace | DPYD, PTBP2 | PTBP2 | DPYD, PTBP2 |

| Duroc(Between two methods) | - | - | ARSB, BHMT, BHMT2, DMGDH, JMY |

| Duroc and Pietrain | DPYD, PTBP2 | PTBP2 | PTBP2 |

| Duroc and Landrace | DPYD, PTBP2 | PTBP2 | PTBP2 |

| Pietrain(Between two methods) | - | - | DPYD, PTBP2 |

| Pietrain and Landrace | DPYD, PTBP2 | PTBP2 | DPYD, PTBP2 |

| Landrace(Between two methods) | - | - | PTBP2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).