Submitted:

13 May 2023

Posted:

15 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phenotypes and Genotyping

2.2. Genotype Imputation and Quality Control

2.3. Statistical Method

2.3.1. Estimation of Genetic Parameters

2.3.2. Principal Component Analysis

2.3.3. Genome-Wide Association Study

2.4. Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

2.5. Candidate Genes Related to Significant SNPs

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Phenotypes

3.2. Estimates of Genetic Parameters

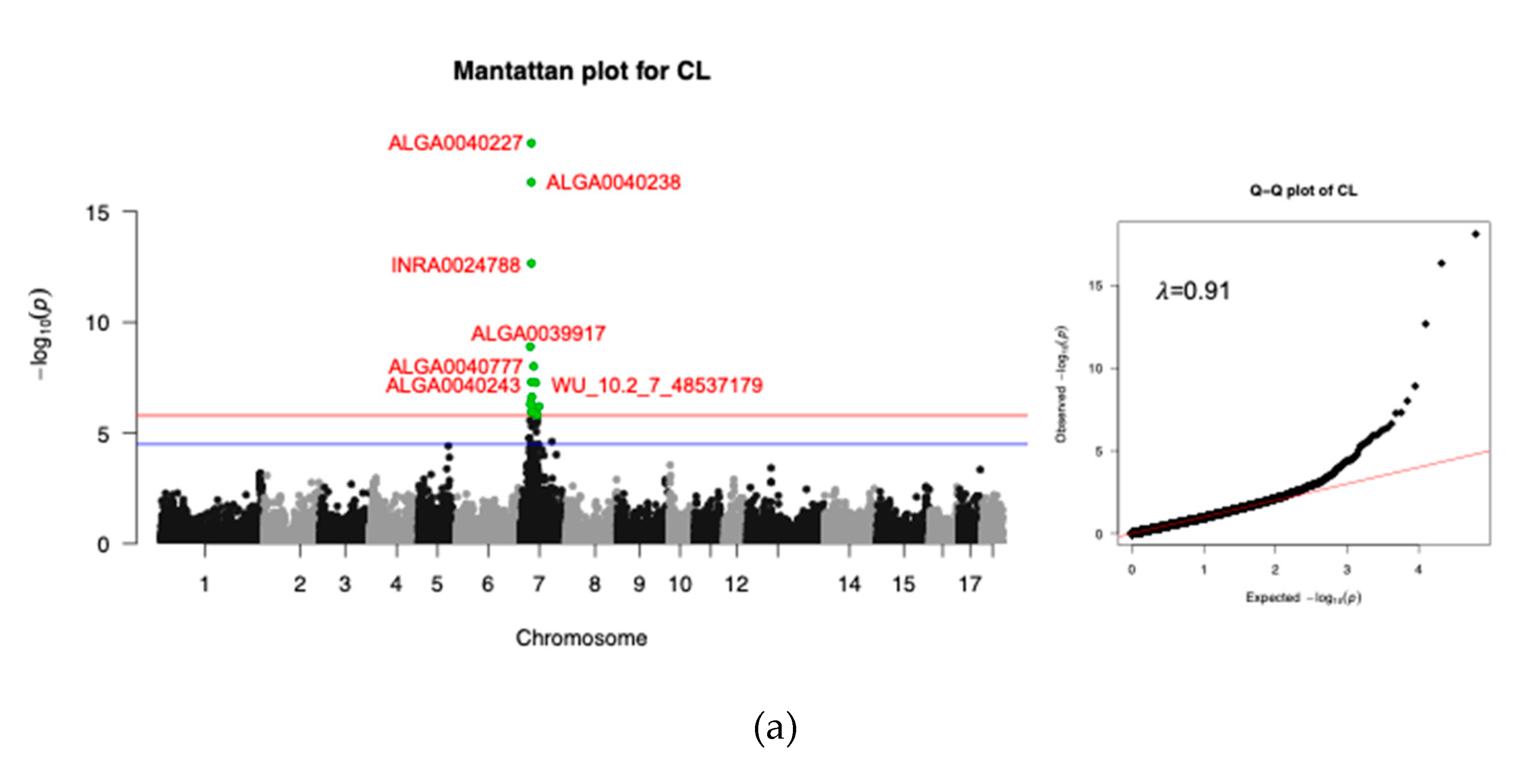

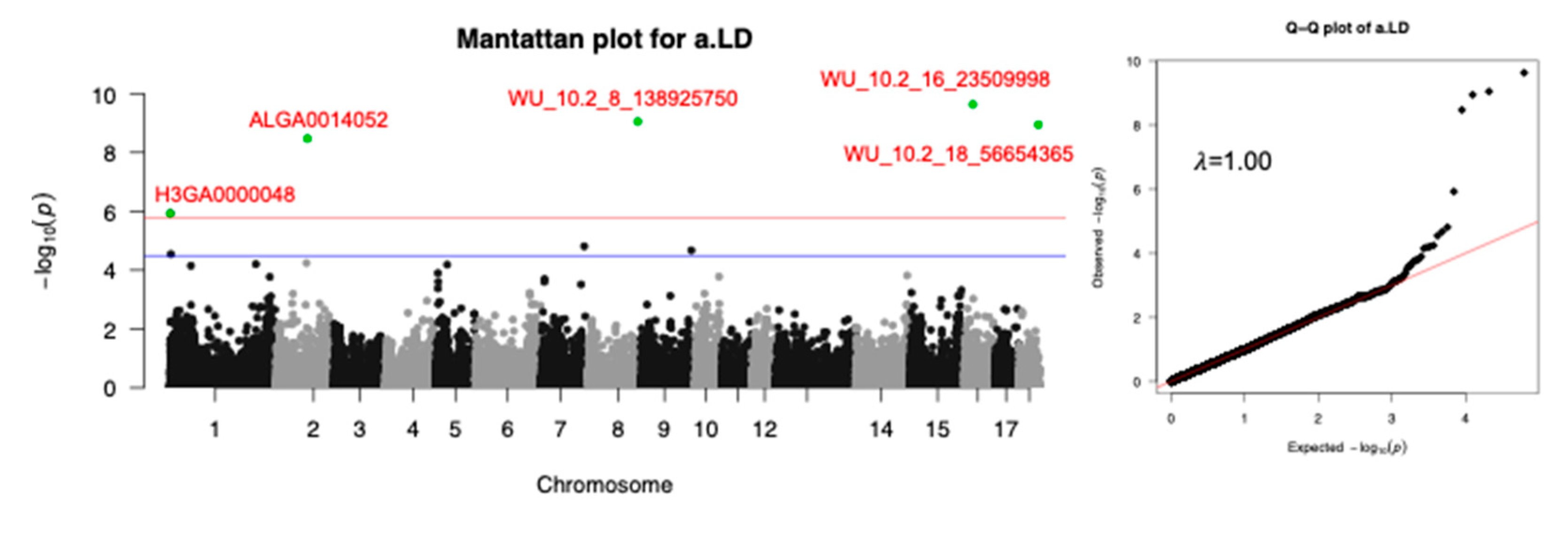

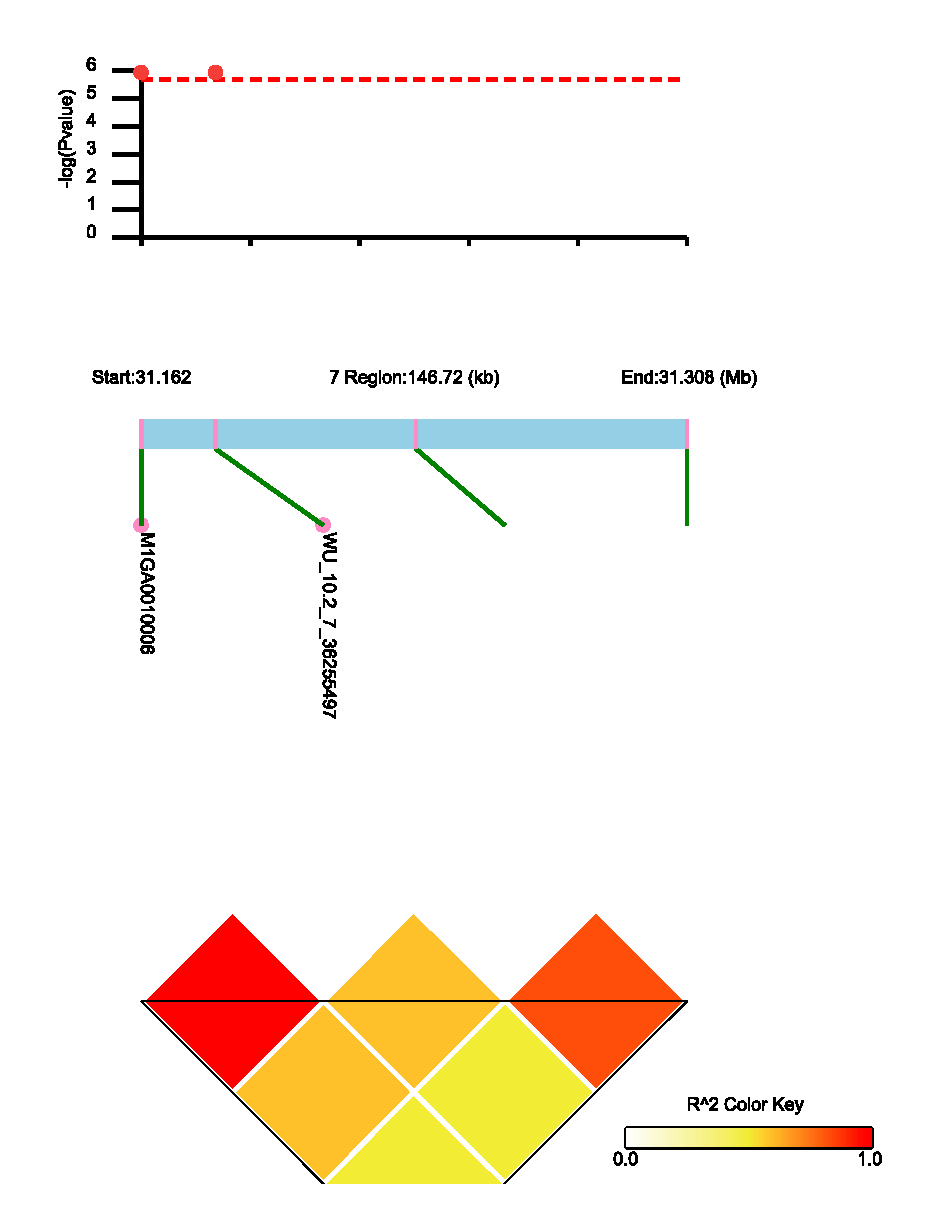

3.3. GWAS Results and Gene Annotation

| Trait | SNP | CHR | POS (bp) | MAF | PVE (%) | P-adj1 | Gene | DIS (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL | ALGA0040227 | 7 | 30176520 | 0.39 | 14.35 | 8.05E-19 | HMGA1 | 143890 |

| ALGA0040238 | 7 | 30197014 | 0.36 | 12.98 | 4.72E-11 | HMGA1 | 123396 | |

| INRA0024788 | 7 | 30317219 | 0.36 | 10.08 | 2.16E-13 | HMGA1 | 3191 | |

| ALGA0039917 | 7 | 26737102 | 0.19 | 7.02 | 1.25E-9 | MLIP | Within | |

| ALGA0040777 | 7 | 36323988 | 0.44 | 6.28 | 9.85E-9 | UNC5CL | 8213 | |

| ALGA0040243 | 7 | 30213771 | 0.25 | 5.69 | 4.97E-8 | HMGA1 | 106639 | |

| WU_10.2_7_48537179 | 7 | 41877149 | 0.42 | 5.66 | 5.39E-8 | ADGRF1 | 23492 | |

| ASGA0032589 | 7 | 31450019 | 0.32 | 5.13 | 2.36E-7 | FKBP5 | Within | |

| H3GA0020641 | 7 | 28521421 | 0.11 | 4.92 | 4.17E-7 | PRIM2 | Within | |

| ALGA0039880 | 7 | 26501975 | 0.11 | 4.86 | 5.04E-7 | TINAG | Within | |

| ALGA0041948 | 7 | 50283279 | 0.47 | 4.77 | 6.30E-7 | STARD5 | 164650 | |

| ALGA0040370 | 7 | 32328188 | 0.48 | 4.60 | 1.02E-6 | SRSF3 | 29608 | |

| M1GA0010006 | 7 | 31161760 | 0.31 | 4.55 | 1.16E-6 | ZNF76 | Within | |

| WU_10.2_7_36255497 | 7 | 31181718 | 0.31 | 4.55 | 1.16E-7 | ZNF76 | Within | |

| MARC0060950 | 7 | 46569153 | 0.16 | 4.44 | 1.58E-6 | LOC100526118 | 1797 | |

| COL | ALGA0040227 | 7 | 30176520 | 0.39 | 8.38 | 2.67E-25 | HMGA1 | 143890 |

| ALGA0040238 | 7 | 30197014 | 0.36 | 7.51 | 3.17E-10 | HMGA1 | 123396 | |

| ALGA0039880 | 7 | 26501975 | 0.11 | 5.75 | 4.19E-7 | TINAG | Within | |

| H3GA0020641 | 7 | 28521421 | 0.11 | 5.14 | 2.30E-7 | PRIM2 | Within | |

| ALGA0039917 | 7 | 26737102 | 0.19 | 4.88 | 4.74E-7 | MLIP | Within | |

| INRA0024788 | 7 | 30317219 | 0.36 | 4.63 | 9.33E-7 | HMGA1 | 3191 | |

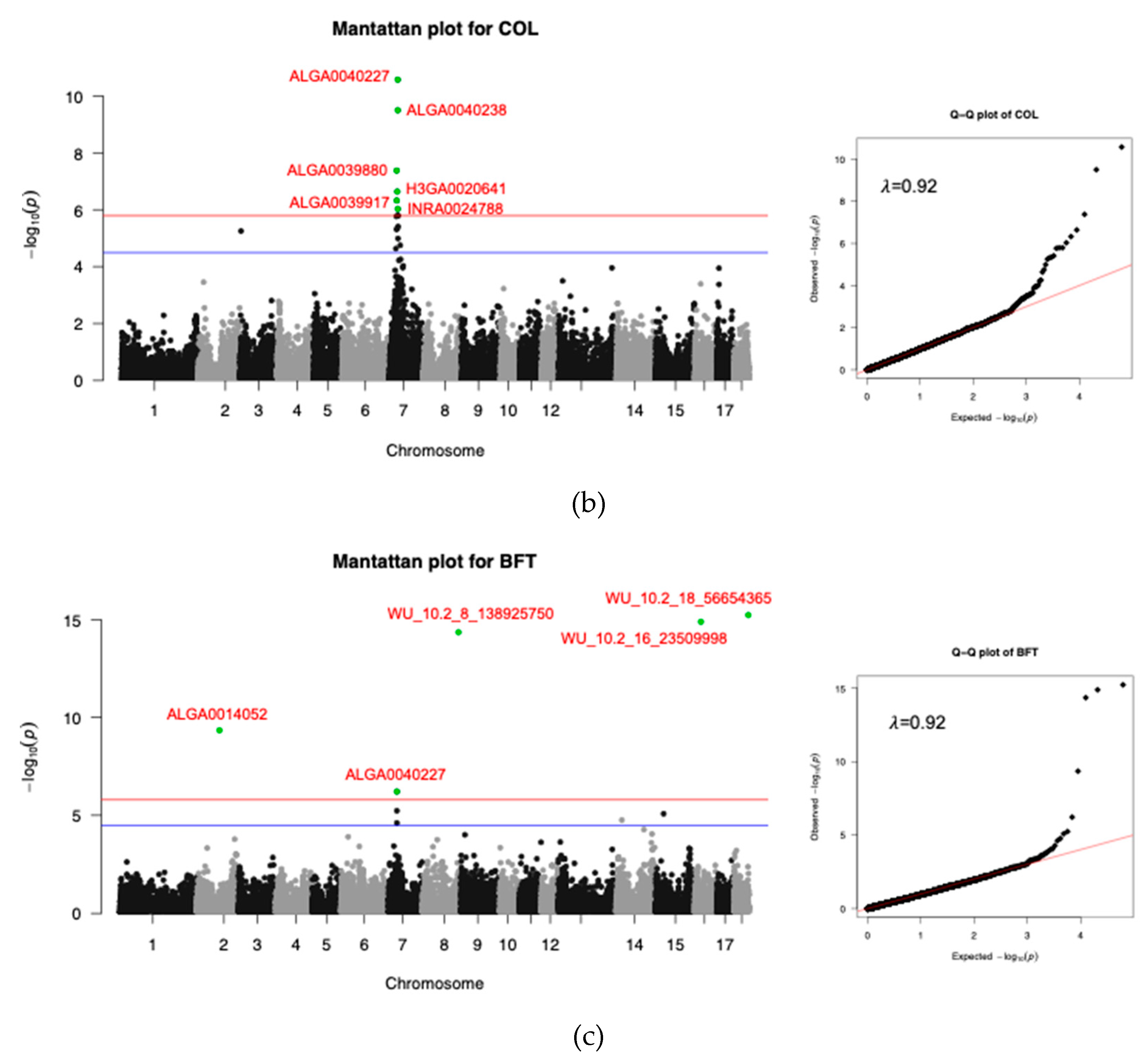

| BFT | WU_10.2_18_56654365 | 18 | 51759775 | 0.12 | 12.66 | 5.80E-16 | HECW1 | Within |

| WU_10.2_16_23509998 | 16 | 22361911 | 0.12 | 12.38 | 1.27E-15 | NIPBL | Within | |

| WU_10.2_8_138925750 | 8 | 129537879 | 0.12 | 11.94 | 4.37E-15 | MMRN1 | 364487 | |

| ALGA0014052 | 2 | 82412427 | 0.14 | 7.72 | 4.52E-10 | TMEM174 | 75272 | |

| ALGA0040227 | 7 | 30176520 | 0.39 | 5.01 | 6.14E-7 | HMGA1 | 143890 |

| Trait | SNP | CHR | POS (bp) | MAF | PVE (%) | P-adj1 | Gene | DIS (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a.LD | WU_10.2_16_23509998 | 16 | 22361911 | 0.12 | 7.94 | 2.34E-10 | NIPBL | Within |

| WU_10.2_8_138925750 | 8 | 129537879 | 0.12 | 7.44 | 8.95E-10 | MMRN1 | 364487 | |

| WU_10.2_18_56654365 | 18 | 51759775 | 0.12 | 7.36 | 1.14E-9 | HECW1 | Within | |

| ALGA0014052 | 2 | 82412427 | 0.14 | 6.95 | 3.38E-9 | TMEM174 | 75272 | |

| H3GA0000048 | 1 | 493510 | 0.01 | 4.75 | 1.19E-6 | PSMB1 | 19168 |

3.3.1. Carcass Trait

3.3.2. Meat Quality Trait

3.4. LD Block Analysis

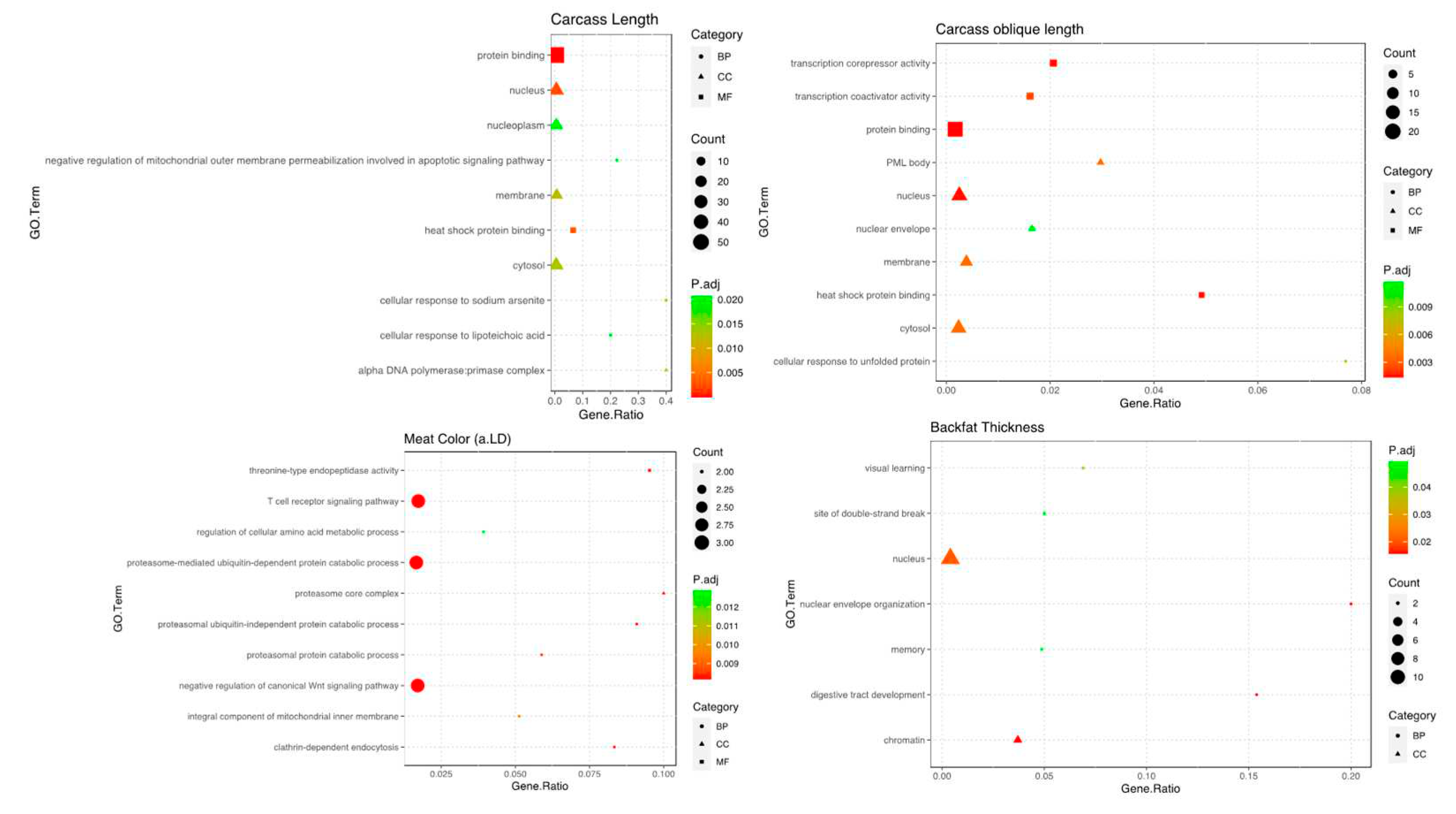

3.5. Functional Enrichment Results

3.5.1. Carcass Trait

3.5.2. Meat Quality Trait

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, M.; Fan, Y.; Li, L.; Fang, S.; Deng, W.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ai, H.; et al. Possible Introgression of the VRTN Mutation Increasing Vertebral Number, Carcass Length and Teat Number from Chinese Pigs into European Pigs. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; Li, D.; Yin, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Flavour Differences of Cooked Longissimus Muscle from Chinese Indigenous Pig Breeds and Hybrid Pig Breed (Duroc×Landrace×Large White). Food Chemistry 2008, 107, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerlaug-Enger, E.; Aass, L.; Ødegård, J.; Vangen, O. Genetic Parameters of Meat Quality Traits in Two Pig Breeds Measured by Rapid Methods. Animal 2010, 4, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Barroso, M.Á.; Silió, L.; Rodríguez, C.; Palma-Granados, P.; López, A.; Caraballo, C.; Sánchez-Esquiliche, F.; Gómez-Carballar, F.; García-Casco, J.M.; Muñoz, M. Genetic Parameter Estimation and Gene Association Analyses for Meat Quality Traits in Open-air Free-range Iberian Pigs. J Anim Breed Genet 2020, 137, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, L.; Zhang, W.; Cui, L.; Yang, J.; Ji, J.; et al. A Large-Scale Comparison of Meat Quality and Intramuscular Fatty Acid Composition among Three Chinese Indigenous Pig Breeds. Meat Science 2020, 168, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Z.; Zhu, L.; Tang, G.Q.; Li, M.Z.; Jiang, A.A.; Cen, W.M.; Xing, S.H.; Chen, J.N.; Wen, A.X.; He, T.; et al. Carcass and Meat Quality Traits of Four Commercial Pig Crossbreeds in China. Genet. Mol. Res. 2012, 11, 4447–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-Z.; Zhu, L.; Li, F.-Q.; Li, X.-W. Carcass Composition and Meat Quality of Indigenous Yanan Pigs of China. Genet. Mol. Res. 2012, 11, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzitey, F.; Nurul, H. Pale Soft Exudative (PSE) and Dark Firm Dry (DFD) Meats: Causes and Measures to Reduce These Incidences: A Mini Review. International Food Research Journal 2011, 18, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, D.N.; Ellis, M.; Miller, K.D.; McKeith, F.K.; Parrett, D.F. The Effect of the Halothane and Rendement Napole Genes on Carcass and Meat Quality Characteristics of Pigs. Journal of Animal Science 2000, 78, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffler, T.L.; Gerrard, D.E. Mechanisms Controlling Pork Quality Development: The Biochemistry Controlling Postmortem Energy Metabolism. Meat Science 2007, 77, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpson, N.J.; Greenwood, C.M.T.; Soranzo, N.; Lawson, D.J.; Richards, J.B. Genetic Architecture: The Shape of the Genetic Contribution to Human Traits and Disease. Nat Rev Genet 2018, 19, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, T.F.C. The Genetic Architecture of Quantitative Traits. 2001, 37.

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Yan, D.; Sun, H.; Chen, Q.; Li, M.; Dong, X.; Pan, Y.; Lu, S. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifying Genetic Variants Associated with Carcass Backfat Thickness, Lean Percentage and Fat Percentage in a Four-Way Crossbred Pig Population Using SLAF-Seq Technology. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, R.; Zhuang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Ruan, D.; Wu, J.; Ye, J.; Cao, L.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, E.; Huang, W.; et al. Identify Known and Novel Candidate Genes Associated with Backfat Thickness in Duroc Pigs by Large-Scale Genome-Wide Association Analysis. Journal of Animal Science 2022, 100, skac012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, I.-C.; Yoo, C.-K.; Lee, J.-B.; Jung, E.-J.; Han, S.-H.; Lee, S.-S.; Ko, M.-S.; Lim, H.-T.; Park, H.-B. Genome-Wide QTL Analysis of Meat Quality-Related Traits in a Large F2 Intercross between Landrace and Korean Native Pigs. Genet Sel Evol 2015, 47, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwannasing, R.; Duangjinda, M.; Boonkum, W.; Taharnklaew, R.; Tuangsithtanon, K. The Identification of Novel Regions for Reproduction Trait in Landrace and Large White Pigs Using a Single Step Genome-Wide Association Study. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2018, 31, 1852–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, X.; Tan, Z.; Xing, K.; Yang, T.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mi, S.; Sun, D.; Wang, C. Genome-Wide Association Study for Reproductive Traits in a Large White Pig Population. Anim Genet 2018, 49, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, B.L.; Zhou, Y.; Browning, S.R. A One-Penny Imputed Genome from Next-Generation Reference Panels. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2018, 103, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Yin, D.; Fu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, S. HIBLUP: An Integration of Statistical Models on the BLUP Framework for Efficient Genetic Evaluation Using Big Genomic Data. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, gkad074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yin, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; et al. rMVP: A Memory-Efficient, Visualization-Enhanced, and Parallel-Accelerated Tool for Genome-Wide Association Study. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2021, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Pressoir, G.; Briggs, W.H.; Vroh Bi, I.; Yamasaki, M.; Doebley, J.F.; McMullen, M.D.; Gaut, B.S.; Nielsen, D.M.; Holland, J.B.; et al. A Unified Mixed-Model Method for Association Mapping That Accounts for Multiple Levels of Relatedness. Nat Genet 2006, 38, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.L.; Patterson, N.J.; Plenge, R.M.; Weinblatt, M.E.; Shadick, N.A.; Reich, D. Principal Components Analysis Corrects for Stratification in Genome-Wide Association Studies. Nat Genet 2006, 38, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanRaden, P.M. Efficient Methods to Compute Genomic Predictions. Journal of Dairy Science 2008, 91, 4414–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teslovich, T.M.; Musunuru, K.; Smith, A.V.; Edmondson, A.C.; Stylianou, I.M.; Koseki, M.; Pirruccello, J.P.; Ripatti, S.; Chasman, D.I.; Willer, C.J.; et al. Biological, Clinical and Population Relevance of 95 Loci for Blood Lipids. Nature 2010, 466, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.-S.; He, W.-M.; Ji, J.-J.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Yang, T.-L. LDBlockShow: A Fast and Convenient Tool for Visualizing Linkage Disequilibrium and Haplotype Blocks Based on Variant Call Format Files. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2021, 22, bbaa227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, D.; Luo, H.; Huo, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; He, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Guo, J.; et al. KOBAS-i: Intelligent Prioritization and Exploratory Visualization of Biological Functions for Gene Enrichment Analysis. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, W317–W325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.; Zheng, C.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, Q.; Li, F.; Long, C.; Xu, K.; Duan, Y.; et al. Comparisons of Carcass Traits, Meat Quality, and Serum Metabolome between Shaziling and Yorkshire Pigs. Animal Nutrition 2022, 8, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Irie, M.; Kadowaki, H.; Shibata, T.; Kumagai, M.; Nishida, A. Genetic Parameter Estimates of Meat Quality Traits in Duroc Pigs Selected for Average Daily Gain, Longissimus Muscle Area, Backfat Thickness, and Intramuscular Fat Content. Journal of Animal Science 2005, 83, 2058–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Lan, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Liang, J.; Liu, X. Detection of DKK3 and CCR1 Genes Polymorphisms and Their Association with Backfat Thickness in Being Black Pigs. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica 2022, 53, 2083–2093. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, P.; Maltecca, C.; Schwab, C.; Gray, K.; Tiezzi, F. Genetic Parameters of Meat Quality, Carcass Composition, and Growth Traits in Commercial Swine. Journal of Animal Science 2019, 97, 3669–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-D.; Jeong, J.-Y.; Hur, S.-J.; Yang, H.-S.; Jeon, J.-T.; Joo, S.-T. The Relationship between Meat Color (CIE L* and A*), Myoglobin Content, and Their Influence on Muscle Fiber Characteristics and Pork Quality. Korean Journal for Food Science of Animal Resources 2010, 30, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hou, L.; Zhou, W.; Wang, B.; Han, P.; Gao, C.; Niu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Huang, R.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study and FST Analysis Reveal Four Quantitative Trait Loci and Six Candidate Genes for Meat Color in Pigs. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 768710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasevic, I.; Djekic, I.; Font-i-Furnols, M.; Terjung, N.; Lorenzo, J.M. Recent Advances in Meat Color Research. Current Opinion in Food Science 2021, 41, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, S.; Xu, K.; He, J. Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Post-Mortem pH and Meat Color Traits in Ningxiang Pigs. Chinese Journal of Animal Science 2021, 57, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Gao, X.; Gao, H.; Xu, S. Effects of DGAT1 Gene on Meat and Carcass Fatness Quality in Chinese Commercial Cattle. Mol Biol Rep 2013, 40, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Stringer, S.; Frei, O.; Umićević Mirkov, M.; de Leeuw, C.; Polderman, T.J.C.; van der Sluis, S.; Andreassen, O.A.; Neale, B.M.; Posthuma, D. A Global Overview of Pleiotropy and Genetic Architecture in Complex Traits. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrer, G.A.; Keele, J.W. Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci Affecting Carcass Composition in Swine: II. Muscling and Wholesale Product Yield Traits. J Anim Sci 1998, 76, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Jennen, D.G.J.; Tholen, E.; Juengst, H.; Kleinwächter, T.; Hölker, M.; Tesfaye, D.; Un, G.; Schreinemachers, H.-J.; Murani, E.; et al. A Genome Scan Reveals QTL for Growth, Fatness, Leanness and Meat Quality in a Duroc-Pietrain Resource Population. Anim Genet 2007, 38, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, Y.; Visscher, P.M.; Haley, C.S. QTL Detection and Allelic Effects for Growth and Fat Traits in Outbred Pig Populations. Genet Sel Evol 2004, 36, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeure, O.; Sanchez, M.P.; Riquet, J.; Iannuccelli, N.; Demars, J.; Fève, K.; Kernaleguen, L.; Gogué, J.; Billon, Y.; Caritez, J.C.; et al. Exclusion of the Swine Leukocyte Antigens as Candidate Region and Reduction of the Position Interval for the Sus Scrofa Chromosome 7 QTL Affecting Growth and Fatness. J Anim Sci 2005, 83, 1979–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratz, P.; Baes, C.; Rückert, C.; Preuss, S.; Bennewitz, J. A Two-Step Approach to Map Quantitative Trait Loci for Meat Quality in Connected Porcine F(2) Crosses Considering Main and Epistatic Effects. Anim Genet 2013, 44, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Shan, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, E.; Yuan, H.; Wang, B. High-Mobility Group At-Hook 1 Mediates the Role of Nuclear Factor I/X in Osteogenic Differentiation Through Activating Canonical Wnt Signaling. Stem Cells 2021, 39, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiefari, E.; Tanyolaç, S.; Iiritano, S.; Sciacqua, A.; Capula, C.; Arcidiacono, B.; Nocera, A.; Possidente, K.; Baudi, F.; Ventura, V.; et al. A Polymorphism of HMGA1 Is Associated with Increased Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Related Components. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Lee, J.J.; Shin, H.Y.; Choi, B.H.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, J.J.; Cho, B.W.; Kim, T.-H. Association of Melanocortin 4 Receptor (MC4R) and High Mobility Group AT-Hook 1 (HMGA1) Polymorphisms with Pig Growth and Fat Deposition Traits. Animal Genetics 2006, 37, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arce-Cerezo, A.; García, M.; Rodríguez-Nuevo, A.; Crosa-Bonell, M.; Enguix, N.; Peró, A.; Muñoz, S.; Roca, C.; Ramos, D.; Franckhauser, S.; et al. HMGA1 Overexpression in Adipose Tissue Impairs Adipogenesis and Prevents Diet-Induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 14487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, D.; Chiefari, E.; Fedele, M.; Iuliano, R.; Brunetti, L.; Paonessa, F.; Manfioletti, G.; Barbetti, F.; Brunetti, A.; Croce, C.M.; et al. Lack of the Architectural Factor HMGA1 Causes Insulin Resistance and Diabetes in Humans and Mice. Nat Med 2005, 11, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Xiao, S.; Li, W.; Huang, T.; Huang, X.; Yan, G.; Huang, Y.; Qiu, H.; Jiang, K.; Wang, X.; et al. Unravelling the Genetic Loci for Growth and Carcass Traits in Chinese Bamaxiang Pigs Based on a 1.4 Million SNP Array. J Anim Breed Genet 2019, 136, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Song, H.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ding, X.; Wang, C. A Single-Step Genome Wide Association Study on Body Size Traits Using Imputation-Based Whole-Genome Sequence Data in Yorkshire Pigs. Front Genet 2021, 12, 629049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, G.; Roehe, R.; Looft, H.; Thoelking, L.; Knap, P.W.; Rothschild, M.F.; Plastow, G.S.; Kalm, E. Associations of DNA Markers with Meat Quality Traits in Pigs with Emphasis on Drip Loss. Meat Sci 2007, 75, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, J.B.; W. , S.S.; David L., L. Osteoclast Differentiation and Activation. Nature 2003, 423, 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, H.K.; Ng, W.F.; Walker, J.A.; Tuck, S.P.; Varanasi, S.S. The Cell Biology of Bone Metabolism. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2008, 61, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-M.; Lin, C.; Stavre, Z.; Greenblatt, M.B.; Shim, J.-H. Osteoblast-Osteoclast Communication and Bone Homeostasis. Cells 2020, 9, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Qian, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Xia, R.; Wang, N.; Liang, J.; Yin, H.; Zhang, A.; Guo, C.; et al. Structural Basis of Adhesion GPCR GPR110 Activation by Stalk Peptide and G-Proteins Coupling. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidaka, S.; Mouri, Y.; Akiyama, M.; Miyasaka, N.; Nakahama, K. GPR110, a Receptor for Synaptamide, Expressed in Osteoclasts Negatively Regulates Osteoclastogenesis. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2022, 182, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falker-Gieske, C.; Blaj, I.; Preuß, S.; Bennewitz, J.; Thaller, G.; Tetens, J. GWAS for Meat and Carcass Traits Using Imputed Sequence Level Genotypes in Pooled F2-Designs in Pigs. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2019, 9, 2823–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, B.; Liao, F.; Shi, Z.-Z.; Ren, Y.; Deng, X.-L.; Yang, T.-T.; Li, D.-Y.; Li, R.-F.; Pu, D.-D.; Wang, Y.-J.; et al. Dihydroartemisinin Inhibits the Proliferation, Colony Formation and Induces Ferroptosis of Lung Cancer Cells by Inhibiting PRIM2/SLC7A11 Axis. OTT 2020, Volume 13, 10829–10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Yan, H.; Liu, X.; Li, N.; Liang, J.; Pu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhao, K.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Studies Identify the Loci for 5 Exterior Traits in a Large White × Minzhu Pig Population. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Wei, M.; Cui, B.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Z.; et al. A FKBP5 Mutation Is Associated with Paget’s Disease of Bone and Enhances Osteoclastogenesis. Exp Mol Med 2017, 49, e336–e336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmady, E.; Deeke, S.A.; Rabaa, S.; Kouri, L.; Kenney, L.; Stewart, A.F.R.; Burgon, P.G. Identification of a Novel Muscle A-Type Lamin-Interacting Protein (MLIP). Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 19702–19713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, M.; Yan, G.; Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, L.; Deng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, H.; Ai, H.; et al. Genome-Wide Association and Evolutionary Analyses Reveal the Formation of Swine Facial Wrinkles in Chinese Erhualian Pigs. Aging 2019, 11, 4672–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Li, G.; Feng, Y. TINAG Mutation as a Genetic Cause of Pectus Excavatum. Medical Hypotheses 2020, 137, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinz, L.X.; Rebsamen, M.; Rossi, D.C.; Staehli, F.; Schroder, K.; Quadroni, M.; Gross, O.; Schneider, P.; Tschopp, J. The Death Domain-Containing Protein Unc5CL Is a Novel MyD88-Independent Activator of the pro-Inflammatory IRAK Signaling Cascade. Cell Death Differ 2012, 19, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Hu, Z.; He, Z.; Jia, W.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Three New Susceptibility Loci for Esophageal Squamous-Cell Carcinoma in Chinese Populations. Nat Genet 2011, 43, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Verma, S.; Bhat, A.; Rasool Bhat, G.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, I.; Singh, H.; Kaul, S.; Rai, E.; Sharma, S. Newly Identified Genetic Variant Rs2294693 in UNC5CL Gene Is Associated with Decreased Risk of Esophageal Carcinoma in the J&K Population–India. BIOCELL 2021, 45, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawauchi, S.; Calof, A.L.; Santos, R.; Lopez-Burks, M.E.; Young, C.M.; Hoang, M.P.; Chua, A.; Lao, T.; Lechner, M.S.; Daniel, J.A.; et al. Multiple Organ System Defects and Transcriptional Dysregulation in the Nipbl+/− Mouse, a Model of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome. PLoS Genet 2009, 5, e1000650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Raza, S.H.A.; Zhang, K.; Mei, C.; Alamoudi, M.O.; Aloufi, B.H.; Alshammari, A.M.; Zan, L. Selection Signatures of Qinchuan Cattle Based on Whole-Genome Sequences. Animal Biotechnology 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, L.; He, S.; Ding, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q. Targeted Resequencing of GWAS Loci Reveals Novel Genetic Variants for Milk Production Traits. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-S.; Ros-Freixedes, R.; Pena, R.N.; Baas, T.J.; Estany, J.; Rothschild, M.F. Identification of Signatures of Selection for Intramuscular Fat and Backfat Thickness in Two Duroc Populations1. Journal of Animal Science 2015, 93, 3292–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Clarke, F.M.; Purslow, P.P.; Warner, R.D. Meat Color Is Determined Not Only by Chromatic Heme Pigments but Also by the Physical Structure and Achromatic Light Scattering Properties of the Muscle. Compr Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | N | Max. | Min. | Mean ± SD | C.V. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL (cm) | 508 | 96.40 | 68.50 | 81.35 ± 4.69 | 5.77 |

| COL (cm) | 508 | 86.50 | 34.10 | 66.11 ± 6.16 | 9.32 |

| BFT (mm) | 485 | 71.06 | 16.17 | 41.61 ± 8.28 | 19.90 |

| L.LD | 508 | 58.73 | 34.80 | 44.73 ± 3.84 | 8.58 |

| a.LD | 508 | 16.17 | 1.34 | 6.53 ± 2.61 | 39.97 |

| b.LD | 508 | 10.53 | 0.14 | 4.00 ± 1.67 | 41.75 |

| pH45min | 508 | 6.96 | 5.46 | 6.28 ± 0.31 | 4.94 |

| pH24h | 508 | 6.87 | 5.46 | 5.91 ± 0.28 | 4.74 |

| Trait | CL | COL | BFT | pH45min | pH24h | L.LD | a.LD | b.LD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL | 0.80(0.06) | 0.87 | -0.53 | -0.22 | -0.27 | 0.25 | -0.05 | 0.14 |

| COL | 0.82*** | 0.47(0.07) | -0.53 | 0.08 | -0.47 | 0.07 | -0.41 | 0.50 |

| BFT | -0.12** | -0.16*** | 0.48(0.08) | 0.07 | -0.08 | -0.32 | 0.07 | -0.32 |

| pH45min | 0.01 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.14(0.11) | 0.10 | 0.27 | -0.39 | 0.41 |

| pH24h | -0.05 | -0.09 | 0.12 | 0.37*** | 0.30(0.09) | 0.45 | 0.42 | -0.37 |

| L.LD | 0.06 | -0.03 | -0.07 | -0.24*** | -0.2*** | 0.11(0.07) | 0.38 | -0.08 |

| a.LD | -0.11* | -0.28*** | 0.18*** | -0.07 | -0.04 | 0.31*** | 0.44(0.08) | -0.23 |

| b.LD | 0.27*** | 0.32*** | -0.18*** | 0.09 | -0.24*** | 0.24*** | 0.03 | 0.19(0.09) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).