Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Ethics

Sampling and Genotyping

Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dias, R. G., Pereira, A. D. C., Negrão, C. E. & Krieger, J. E. Genetic polymorphisms determining of the physical performance in elite athletes. Rev. Bras. Med. do Esporte 2007. 13, 209–216.

- Blanchard, A., Ohanian, V. & Critchley, D. The structure and function of α-actinin. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 1989. 10, 280–289. [CrossRef]

- Pasqua, L. A., Artioli, G. G., Pires, F. de O. & Bertuzzi, R. ACTN 3 e desempenho esportivo: Um gene candidato ao sucesso em provas de curta e longa duração. Rev. Bras. Cineantropometria e Desempenho Hum 2011. 13, 477–483.

- Dias, R. G. Genetics, human physical performance and gene doping: The common sense versus the scientific reality. Rev. Bras. Med. do Esporte 2011. 17, 62–70.

- Mills, Michelle A., Nan Yang, Ron Weinberger, Douglas L. Vander Woude, Alan H. Beggs, Simon Easteal, and Kathryn N. North. Differential expression for the actin-binding proteins, α-actinin-2 and -3, in different species: Implications for the evolution of functional redundancy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001. 10, 1335–1346. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Nan, Daniel G. MacArthur, Jason P. Gulbin, Allan G. Hahn, Alan H. Beggs, Simon Easteal, and Kathryn North. ACTN3 genotype is associated with human elite athletic performance. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2003, 73, 627–631. [CrossRef]

- Chae, J. H., Eom, S.-H., Lee, S.-K., Jung, J.-H. & Kim, C.-H. Association between Complex ACTN3 and ACE Gene Polymorphisms and Elite Endurance Sports in Koreans: A Case–Control Study. Genes (Basel). 2024, 15, 1110. [CrossRef]

- Niemi, A. K. & Majamaa, K. Mitochondrial DNA and ACTN3 genotypes in Finnish elite endurance and sprint athletes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet 2005, 13, 965–969. [CrossRef]

- Norman, Barbara, Mona Esbjörnsson, Håkan Rundqvist, Ted Österlund, Ferdinand Von Walden, and Per A. Tesch. Strength, power, fiber types, and mRNA expression in trained men and women with different ACTN3 R577X genotypes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 959–965.

- Walsh, P. S., Metzger, D. A. & Higuchi, R. Chelex® 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. Biotechniques 1991, 10, 506–513.

- Habibi, Abdolhamid, Mehrzad Shabani, Esmaeil Rahimi, Rouhollah Fatemi, Abdolrahman Najafi, Hossein Analoei, and Morad Hosseini. Relationship between jump test results and acceleration phase of sprint performance in national and regional 100m sprinters. J. Hum. Kinet 2010, 23, 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Marques, M. C. & González-Badillo, J. J. Relationship between strength parameters and squat jump performance in trained athletes. Motricidade 2011, 7, 43–48.

- Vescovi, J. D. & McGuigan, M. R. Relationships between sprinting, agility, and jump ability in female athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Druzhevskaya, A. M., Ahmetov, I. I., Astratenkova, I. V. & Rogozkin, V. A. Association of the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism with power athlete status in Russians. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 103, 631–634. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, D. T., Marakaki, C., Fretzayas, A., Nicolaidou, P. & Papadimitriou, A. Negativation of type 1 diabetes-associated autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase and insulin in children treated with oral calcitriol. J. Diabetes 2013, 5, 344–348.

- Moran, Colin N., Nan Yang, Mark E. S. Bailey, Athanasios Tsiokanos, Athanasios Jamurtas, Daniel G. MacArthur, Kathryn North, Yannis P. Pitsiladis, and Richard H. Wilson. Association analysis of the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism and complex quantitative body composition and performance phenotypes in adolescent Greeks. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 15, 88–93. [CrossRef]

- Cieszczyk, Paweł, Jerzy Eider, Magdalena Ostanek, Aleksandra Arczewska, Agata Leońska-Duniec, Stanisław Sawczyn, Krzysztof Ficek, and Krzysztof Krupecki. Association of the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism in Polish power-orientated athletes. J. Hum. Kinet. 2011, 28, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Romo, Gabriel, Thomas Yvert, Alfonso de Diego, Catalina Santiago, Alfonso L. Díaz de Durana, Vicente Carratalá, Nuria Garatachea, and Alejandro Lucia. No Association Between ACTN3 R577X Polymorphism and Elite Judo Athletic Status. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform 2013, 8, 579–581. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A. J., Keane, S. P. & Coglan, J. Force-velocity relationship and stretch-shortening cycle function in sprint and endurance athletes. J. strength Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 473–479. [CrossRef]

- Paulo, By, Jorge Paixão, Victor Manuel, Machado Reis, Paulo Jorge, and Paixão Miguel. 400M Performance. Methods 2004, 39–45.

- MacArthur, D. G. & North, K. N. A gene for speed? The evolution and function of α-actinin-3. BioEssays 2004, 26, 786–795.

- Vincent, Barbara, Katrien De Bock, Monique Ramaekers, Els Van Den Eede, Marc Van Leemputte, Peter Hespel, and Martine A. Thomis. ACTN3 (R577X) genotype is associated with fiber type distribution. Physiol. Genomics 2007. 32, 58–63. [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, Eduardo Mendonça, Daniel Barbosa Coelho, Izinara Rosse Cruz, Rodrigo Figueiredo Morandi, Christiano Eduardo Veneroso, Guilherme De Azambuja Pussieldi, Maria Raquel Santos Carvalho, Emerson Silami-Garcia, and José Antonio De Paz Fernández. 2012. The ACTN3 genotype in soccer players in response to acute eccentric training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol 2012, 112, 1495–1503. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C. J., A. V. September, S. L. Xenophontos, M. A. Cariolou, L. C. Anastassiades, T. D. Noakes, and M. Collins. No association of the ACTN3 gene R577X polymorphism with endurance performance in Ironman Triathlons. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2007, 71, 777–781. [CrossRef]

| 100m race | Long jump | Shot put | High jump | 400m race | |||||

| RES - sec | Points | RES - m | Points | RES – m | Points | RES. - | Points | RES. – sec | Points |

| 10.50 | 975 | 7.39 | 908 | 14.02 | 730 | 1.99 | 794 | 49.67 | 830 |

| 10.51 | 973 | 7.38 | 905 | 14.01 | 729 | 1.98 | 785 | 49.69 | 829 |

| 10.52 | 970 | 7.37 | 903 | 13.99 | 728 | 1.97 | 776 | 49.72 | 828 |

| 10.53 | 968 | 7.36 | 900 | 13.97 | 727 | 1.96 | 767 | 49.74 | 827 |

| 10.54 | 966 | 7.35 | 898 | 13.96 | 726 | 1.95 | 758 | 49.76 | 826 |

| 10.55 | 963 | 7.34 | 896 | 13.94 | 725 | 1.94 | 749 | 49.78 | 825 |

| 10.56 | 961 | 7.33 | 893 | 13.93 | 724 | 1.93 | 740 | 49.80 | 824 |

| 10.57 | 959 | 7.32 | 891 | 13.91 | 723 | 1.92 | 731 | 49.82 | 823 |

| 10.58 | 956 | 7.31 | 888 | 13.89 | 722 | 1.91 | 723 | 49.85 | 822 |

| 10.59 | 954 | 7.30 | 886 | 13.88 | 721 | 1.90 | 714 | 49.87 | 821 |

| 110 w/obstacle | Disc launch | Pole jump | Javelin throw | 1500m race | |||||

| RES - sec | Points | RES - m | Points | RES - m | Points | RES - m | Points | RES - min | Points |

| 14.20 | 949 | 44.16 | 750 | 4.79 | 846 | 60.12 | 740 | 4:39.33 | 685 |

| 14.21 | 948 | 44.11 | 749 | 4.78 | 843 | 60.05 | 739 | 4:39.49 | 684 |

| 14.22 | 946 | 44.06 | 748 | 4.77 | 840 | 59.98 | 738 | 4:39.65 | 683 |

| 14.23 | 945 | 44.02 | 747 | 4.76 | 837 | 59.92 | 737 | 4:39.80 | 682 |

| 14.24 | 944 | 43.97 | 746 | 4.75 | 834 | 59.85 | 736 | 4:39.96 | 681 |

| 14.25 | 942 | 43.92 | 745 | 4.74 | 831 | 59.78 | 735 | 4:40.12 | 680 |

| 14.26 | 941 | 43.87 | 744 | 4.73 | 828 | 59.72 | 734 | 4:40.28 | 679 |

| 14.27 | 940 | 43.82 | 743 | 4.72 | 825 | 59.65 | 733 | 4:40.44 | 678 |

| 14.28 | 939 | 43.77 | 742 | 4.71 | 822 | 59.58 | 732 | 4:40.60 | 677 |

| 14.29 | 937 | 43.72 | 741 | 4.70 | 819 | 59.52 | 731 | 4:40.76 | 676 |

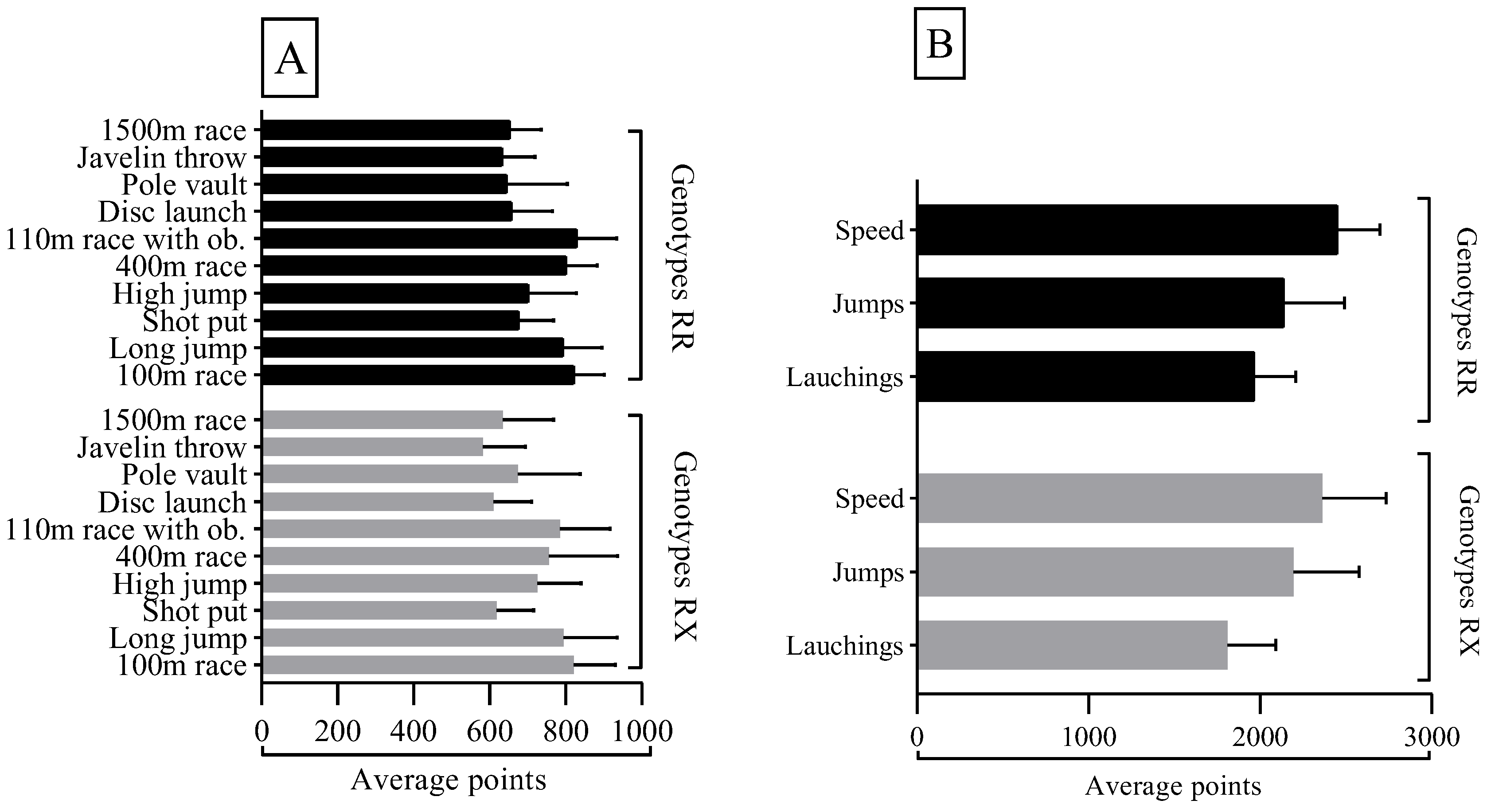

| Set of Events | Sum of points | Average points | Fitness skills |

| Speed | 2.418 | 806 | Explosive strength, displacement speed, agility |

| Jumps | 2.188 | 729 | Travel speed, explosive force |

| Throwing and Launching | 1.932 | 644 | Maximum strength, explosive strength |

| Medium Distance - 1500m | -- | 633 | Aerobic Power |

| Tests | Race. 100m | L.J | S. put | H.J | C.400m | R.110m w/H | T. of disc | Pole jump | T. of the dart | R. 1500m | |

| 100m race | r | 1 | .727** | .375* | .526** | .759** | .625** | .336 | .428* | .292 | .463** |

| p | 0 | .038 | .002 | 0 | 0 | .064 | .016 | .111 | .009 | ||

| 400m race | r | .759** | .651** | .581** | .583** | 1 | .640** | .489** | .612** | .500** | .285 |

| p | 0 | 0 | .001 | .001 | 0 | .005 | 0 | .004 | .12 | ||

| Long jump | r | .727** | 1 | .558** | .789** | .651** | .829** | .580** | .623** | .385* | .328 |

| p | 0 | .001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .001 | 0 | .033 | .071 | ||

| Shot put | r | .375* | .558** | 1 | .583** | .581** | .651** | .736** | .699** | .640** | .035 |

| p | .038 | .001 | .001 | .001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .853 | ||

| High jump | r | .526** | .789** | .583** | 1 | .583** | .745** | .712** | .790** | .397* | .04 |

| p | .002 | 0 | .001 | .001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .027 | .832 | ||

| 110m race with ob. | r | .625** | .829** | .651** | .745** | .640** | 1 | .675** | .607** | .433* | .309 |

| p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .015 | .09 | ||

| Disc launch | r | .336 | .580** | .736** | .712** | .489** | .675** | 1 | .805** | .608** | -.155 |

| p | .064 | .001 | 0 | 0 | .005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .406 | ||

| Pole jump | r | .428* | .623** | .699** | .790** | .612** | .607** | .805** | 1 | .546** | .037 |

| p | .016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .001 | .842 | ||

| Javelin throw | r | .292 | .385* | .640** | .397* | .500** | .433* | .608** | .546** | 1 | -.129 |

| p | .111 | .033 | 0 | .027 | .004 | .015 | 0 | .001 | .49 | ||

| 1500m race | r | .463** | .328 | .035 | .04 | .285 | .309 | -.155 | .037 | -.129 | 1 |

| p | .009 | .071 | .853 | .832 | .12 | .09 | .406 | .842 | .49 | ||

| Set of events | Variable | Speed | Jumps | Launches |

| Speed | R | 1 | .786 | .634 |

| p-value | <.01 | <.01 | ||

| N | 31 | 31 | 31 | |

| Jumps | R | .786 | 1 | .747 |

| p-value | <.01 | <.01 | ||

| N | 31 | 31 | 31 | |

| Launching and Throws |

R | .634 | .747 | 1 |

| p-value | <.01 | <.01 | ||

| N | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| Genotypes Frequency | Alleles Frequency | |||

| R577R(%) | R577X(%) | X577X(%) | 577R(%) | 577X(%) |

| 16 (51.6%) |

15 (48.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

76 | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).