1. Introduction

Global warming is one of the most pressing challenges of the 21st century, driven primarily by the excessive accumulation of greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O) in the atmosphere. The rise in global temperatures has led to severe climatic changes, including rising sea levels, extreme weather events, biodiversity loss, and disruptions to ecosystems. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels requires rapid and significant reductions in carbon emissions across all sectors [

1]. To achieve this, a transition toward low-carbon and carbon-neutral energy sources is essential.

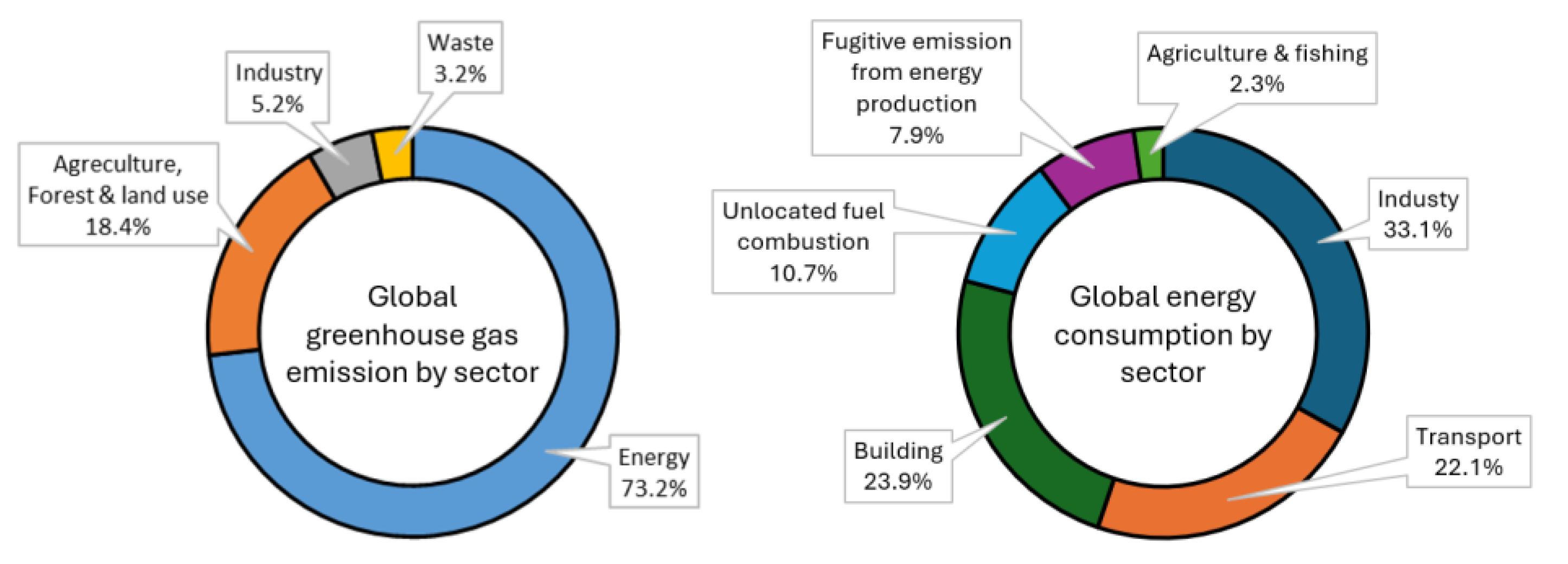

More than 73% of global CO₂ emissions originate from energy production processes [

2]. Despite the increasing adoption of renewable energy sources, most electricity generation is still obtained through the burning of fossil fuels (such as coal, oil and gas) in thermal power plants. This contributes enormously to anthropogenic CO₂ emissions. Meanwhile, the transportation sector (including e.g. automobiles, aviation, and shipping) is also heavily reliant on fossil fuels such as gasoline, diesel and fuel oil, contributing approximately 15% to global CO₂ emissions [

2]. Furthermore, the production of cement, steel, glass, and chemical products is highly energy-intensive and accounts for a significant share of industrial emissions. For example, cement manufacturing alone is responsible for 7-8% of global CO₂ emissions [

2].

Figure 1 summarises global greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption by sector. Decarbonising these sectors is, therefore crucial for the good of humanity.

Among the solutions to rising emissions, hydrogen has emerged as a key enabler in the global push for decarbonisation. As an energy carrier, hydrogen is highly versatile and can be used to replace fossil fuels across multiple sectors. Unlike fossil fuels, hydrogen combustion produces only water vapour at the point of use. On the other hand, the environmental impact of hydrogen production depends greatly on the selected production method, which still often relies on carbon-intensive fossil fuels. The development of carbon-neutral or carbon-negative hydrogen production technologies will therefore be a crucial step in achieving carbon neutrality.

The main methods for hydrogen production are categorised by colours: green, blue, grey, yellow, white, brown, pink, and turquoise. Most hydrogen produced today is grey hydrogen, produced from natural gas in a process called steam methane reforming (SMR). However, this process generates large amounts of CO₂ as a byproduct, contributing to global emissions [

3]. Blue hydrogen is also produced via SMR, but the incorporation of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies prevents CO₂ from being released directly into the atmosphere. While this does prevent emissions, CCS is a newly emerging technology requiring considerable extra costs and significantly reducing the overall process efficiency [

4]. Green hydrogen is produced by electrolysis of water using renewable electricity (being classified as yellow hydrogen if solar electricity is used directly), and generating pure oxygen as a byproduct. Whilst this method is carbon-neutral, its widespread adoption is being limited by factors such as scalability, supply chain issues, materials costs, and high energy requirements [

4]. Furthermore, electrolysis requires copious quantities of pure water (~10 kg of water per kilogram of hydrogen) despite global water resources already being under significant stress [

5,

6], whilst also relying on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS, or “forever chemicals”), which are ecologically problematic and subject to increasing regulatory scrutiny [

7]. Meanwhile, pink hydrogen is generated using nuclear power and is also technically carbon neutral. Nonetheless, the controversies surrounding nuclear power and the cost of installing new nuclear power stations present significant hurdles to adoption [

6].

Turquoise hydrogen production is an emerging and highly promising alternative to the above technologies. However, a crucial difference is that the methane undergoes pyrolysis, where it is thermally decomposed into hydrogen and solid carbon, rather than CO₂ [

3]. Solid carbon is thermodynamically stable, locking the carbon in this form indefinitely without it being released into the atmosphere. As such, even when using natural gas as a feedstock, the process is carbon neutral, eliminating the need for costly CCS infrastructure. In the case that biogas is used as a feedstock, the process becomes carbon-negative, actively reducing the total amount of carbon dioxide present in the carbon cycle. Meanwhile, the generated solid carbon could be enormously useful in many industrial applications, such as in car tyres, catalyst supports, battery electrodes, black dyes, and construction materials, adding further value to the process. Furthermore, turquoise hydrogen does not require water as a feedstock, thereby reducing stress on global water resources [

8]. This is especially crucial considering that at least half of the ten countries with the highest potential for renewable energy generation experience significant water stress [

9]. Finally, methane pyrolysis is already highly compatible with existing chemical processes in the oil and gas industry and can be added or incorporated into sites with minimal footprint or impact. Overall, the above points potentially make methane pyrolysis an economically viable and highly sustainable hydrogen production route [

8,

9].

Pyrolysis is defined as an endothermic thermochemical decomposition process that breaks down hydrocarbons at high temperatures in an oxygen-deficient environment. For example, the pyrolysis of wood has been used in the manufacture of charcoal and biochar for millennia. The reaction for hydrogen production via pyrolysis of methane can be written as:

In the above case, sufficient thermal energy must be provided to break the covalent bonds between carbon and hydrogen in the methane molecule, which typically occurs at around 1500 ºC. Methane pyrolysis typically occurs in specialised reactors, the design of which depends on how the thermal energy to break these bonds is provided. This could be provided in the form of fuel combustion, electrical energy, concentrated solar energy, plasma, or indirectly via molten metals or molten carbonates [

3,

10]. Introducing a catalyst to the process lowers the required debonding energy between the molecules [

3,

10] and can be used.

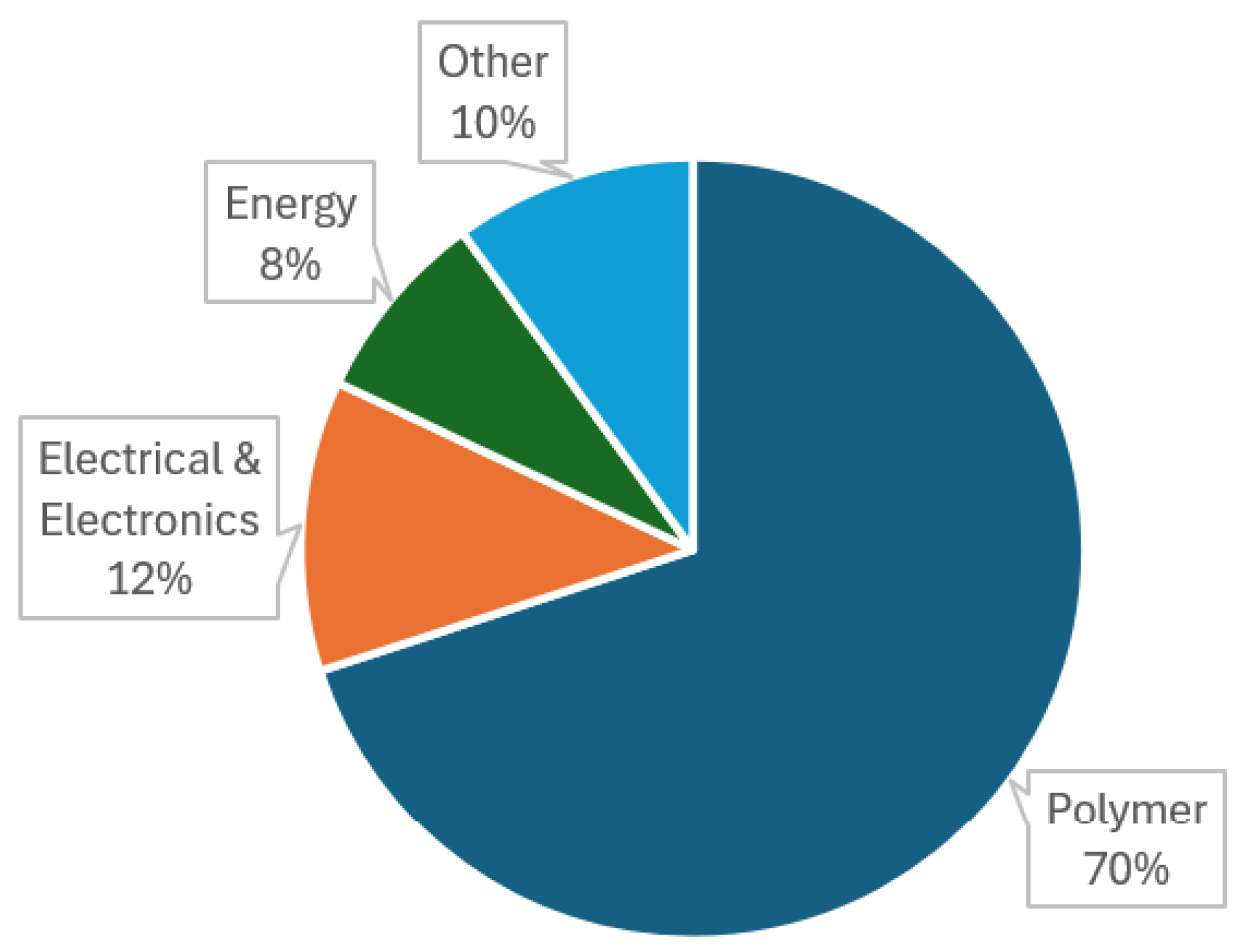

Meanwhile, the solid carbon materials generated during methane pyrolysis can take many different forms depending on the conditions in the reactor. These may include, for example, carbon black, graphite, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, amorphous carbons, or varients/hybrids of the above. Each of these is a potentially high-value product with distinct end uses and widely varying market values [

3]. Currently, many of these carbon nanomaterials are derived from petroleum products, so another advantage of methane pyrolysis is that it provides a more sustainable route to their manufacture.

Electrification of the process enables direct energy transfer and precise temperature control, which is expected to improve overall efficiency and product purity. Meanwhile, using renewable electricity is expected to have wider benefits, such as contributing to grid balancing, providing a means for large-scale and long-term energy storage, improving energy security by reducing dependence on fossil fuel imports, and lowering process costs, especially in regions with abundant solar or wind resources.

As industries increasingly seek economically viable and environmentally friendly sustainable solutions to hydrogen production and carbon manufacture, pyrolysis-based hydrogen production is clearly a major contender for the reasons outlined above. Gaining industry-wide insights into this process and understanding the fundamental factors that govern the reaction is essential as we move towards global scale-up and commercialisation, as well as keeping abreast of recent technological advancements.

This review provides a concise overview of existing methods for turquoise hydrogen production, highlighting key challenges and recent advancements. It explores electrified technologies adopted by industries since 2020, including resistive heating, induction, and microwave methods, as well as other emerging approaches such as plasma-based, molten metal/salts, and fluidised bed systems, which can also utilise electricity as an energy source. Additionally, the study examines the market potential of turquoise hydrogen byproducts, analysing trends in technology adoption and funding. A comparative analysis of energy costs between turquoise hydrogen and green hydrogen is presented, emphasising economic considerations. Finally, the review discusses the current challenges in the field and outlines future directions for advancing turquoise hydrogen technology.

2. Technological Advances in Electrified Hydrogen Pyrolysis

This section provides a detailed explanation of the principles behind each electrified method used for hydrogen pyrolysis and highlights recent research developments in the field. Additionally, the key challenges associated with each method are discussed, including technical limitations, efficiency concerns, and scalability issues. Furthermore, the study introduces industries that have adopted these technologies, shedding light on their implementation in real-world applications.

2.1. Joule Heating

Joule heating involves the conversion of electrical energy into heat energy when passing a current, due to the resistance of a given material. Otherwise known as resistive heating, it is an incredibly common method of heating, allowing for swift and controllable temperature elevation simply by varying the current passing through the resistor. It has a theoretical efficiency of 100% for the conversion of electrical energy into heat [

11], making it the method of choice in a wide variety of heating applications.

Joule heating is therefore a technique of great interest in methane pyrolysis applications, to overcome the endothermic nature of the reaction. The high degree of control over the amount of heat generated can allow for efficient and uniform thermal distribution within the reactor, enhancing reaction rates and hydrogen yield [

12]. Furthermore, the high theoretical conversion efficiency minimises energy loss, leading to higher overall process efficiency compared with e.g. the use of combustion heating [

13].

Joule heating in methane pyrolysis can be either direct or indirect, based on the location of the heating element relative to the catalyst. In direct Joule heating, the catalyst must be electrically conductive and is heated directly and locally via its own internal resistance. This method is energy efficient since the catalyst is heated directly, and results in rapid temperature ramp rates. However, the catalyst material should have suitable electrical and thermal properties, limiting the choice of appropriate materials [

13]. In contrast, indirect Joule heating normally occurs through the reactor wall or via an inner conductive element. This gives access to a wider range of catalysts but can affect the efficiency of the reactors as the heat must transfer from the heating element to the catalyst [

14,

15,

16].

Meanwhile, the high temperatures required for methane pyrolysis (i.e. above 1000°C) necessitate the use of appropriate materials that can withstand such conditions for an appreciable amount of time, whilst maintaining their materials properties under the reducing conditions of the reactor [

13]. Examples of heating elements could include metallic alloys, ceramic materials, silicon carbide (SiC), or graphitic materials. For example, Dong, et al. [

17] demonstrated catalyst-free methane pyrolysis (as well as ammonia cracking) via Joule heating, using a flexible carbon heating element to rapidly increase and precisely control the temperature (400 ˚C and 1700 ˚C within milliseconds), leading to better control of the product. In they study the impact of pulsive heating and cooling with average temperature of 600 ˚C was mainly investigated which resulted in over 20% conversion rated for hydrogen. They did not clearly mention the type of heater they used but suggested commercial porous elements such as carbon foam or carbon felt. Similarly, a SiC-based resistive heating element coated with Ni-based catalysts for hydrogen pyrolysis was investigated by Renda et al. [

18], reporting methane conversion rate and hydrogen yield of over 80% at 800 °C with heating rate of 10 ˚C/min.

2.2. Induction Heating

Induction heating involves the application of an alternating current in an external coil to generate an alternating magnetic field, which in turn induces a current in a conductive material placed inside the coil, increasing the temperature via resistive heating. When applied to methane pyrolysis this is analogous to the Joule heating effect, but in this case no physical connection between the catalyst and the external power source is required. As such this is considered to be an indirect heating method. Inductive heating has previously been demonstrated for eSMR applications, in which a conductor coil is positioned outside the reactor and catalyst bed, and an inductive material is integrated into the reactor [

19]. The magnetic field produced by the external coil heats the catalyst zone through magnetic hysteresis heating or induced resistive heating.

One consideration for high-temperature applications for inductive heating (e.g. > 1000°C for catalyst-free methane pyrolysis), is that ferromagnetic materials lose their permanent magnetism above the Curie temperature (Tₙ). This presents an upper limit to the useful temperature for a given material. For that reason, the magnetic susceptor for induction-driven methane pyrolysis (or eSMR) is normally based on materials with high Curie temperature, such as cobalt (Tₙ~1300 °C) [

20,

21]. Therefore, induction is more commonly used for lower temperature hydrogen production processes, such as dry reforming of methane (DRM), in which methane is reacted with CO2 to form hydrogen and carbon monoxide, a reaction that that typically occurs at 600 to 1000 ºC [

22]. Furthermore, the use of catalysts can improve the feasibility of induction heating by reducing the decomposition temperature of methane [

19,

20]. Another disadvantage of inductive heating is the heating efficiency is only around 90% [

15,

16], compared with 100% for direct resistive heating. Furthermore, induction provides a higher initial cost and complex setup compared with Joule heating [

23]. To the author's knowledge, no published research specifically explores the use of induction heating for methane pyrolysis.

2.3. Microwave-Induced Methane Pyrolysis

Another way to access high temperatures for chemical processes is via microwave heating. Microwaves interact with materials that have dielectric properties, causing them to vibrate and generate heat. In the case of methane pyrolysis, microwave radiation is used to selectively heat a catalyst inside a reactor to the point where the thermal energy can break down methane into hydrogen and solid carbon. This enables efficient pyrolysis at locally high temperatures without the need for an external heat source.

In methane pyrolysis, microwave heating is a relatively new development. It offers several advantages over conventional methods such as heating by electric heating or by combustion of fossil fuels. One key benefit is the ability to selectively and rapidly heat materials [

24]. For example, microwaves can selectively heat the catalyst itself, which quickly becomes the hottest component in the reactor, facilitating methane decomposition.

Dadsetan et al. [

25] demonstrated a microwave methane pyrolysis reactor based on a fluidised bed design, and determined that investigated the impact of carbon particle inclusion in improving microwave energy absorption and chieved hydrogen selectivity of over 90% at 1000 ˚C. Furthermore, free volume, packed bed, fluid wall, and tubular microwave reactors have also been studied [

10]. However, fluidised bed type reactors typically result in improved performance, due to e.g. reactor blockage when using other methods [

26].

One major issue with this method is the non-uniformity of microwave absorption [

27], with researchers working on improved reactor design and optimising, e.g., microwave frequency and power density, to overcome this.

Aurora Hydrogen is a startup company founded in 2021, headquartered in Alberta, Canada. Their technology centres on the utilisation of microwave energy to convert natural gas into hydrogen and solid carbon, in a catalyst-free process. The company claims that the process requires 80% less electricity compared with water electrolysis, whilst eliminating the need for water. Whilst the organisation itself has not published formal research papers, their technology has been validated with academic partners. In 2021, researchers at the University of Toronto conducted bench-scale reactor tests on Aurora's proprietary hydrogen production processes [

28,

29]. In these reports, a fluidised-bed reactor was used in combination with microwave heating. Activated carbon served as a seed material, placed into quartz tubes. When irradiated with microwaves, these absorbed the microwave energy, increasing the temperature to ~1000 °C. This thermal energy was then transferred to methane gas molecules (99% purity, 1 atm) flowing through the fluidised carbon particle bed, facilitating the decomposition to carbon and hydrogen [

25]. The reactor was operated for a cumulative 500 hours, reportedly maintaining greater than 90% hydrogen selectivity throughout the process. The morphology of the carbon product was reported to be “sand-like", with the relatively large particle size facilitating safe transport, and with target applications in e.g. the construction industry (as a replacement for construction sand) [

30]. The technology is claimed to be highly modular and scalable, allowing for on-site hydrogen production at various scales at a cost of ~

$1.50 per kilogram, even without accounting for potential revenue from the sale of the solid carbon byproduct [

31]. Notably, the company has received

$3 million in funding from Natural Resources Canada, and over

$1 million from the NGIF Accelerator [

32].

2.4. Plasma Methane Pyrolysis

A plasma can be created by supplying a gas with a large amount of electrical energy (via the application of high voltage) at a specific temperature and pressure. The process excites and ionises the gas molecules, generating electrons which then collide with other molecules, creating more ions and electrons.

This method can also be used in methane pyrolysis, in which a plasma is initiated in a methane atmosphere using e.g. a plasma torch, and maintained using a high-voltage electric field, generating hydrogen and solid carbon. The temperature in the plasma can range from e.g. 1000 to 3500 °C [

10], and different varieties of plasma reactor used in this application include: arc plasma; microwave plasma, or corona discharge plasma [

33,

34].

Some of the advantages of plasma methane pyrolysis include high methane conversion ratios [

25], and the generation of high-quality carbon nanomaterials [

35]. However, challenges such as high energy demand [

35], electrode erosion during operation, and reactor stability issues must be addressed before large-scale industrial adoption [

34]. Despite these challenges, plasma pyrolysis remains a promising method for decarbonised hydrogen production with potential applications in clean energy and carbon material industries.

In 2012, the U.S. company Monolith Materials began development of a plasma-based pyrolysis process for methane decomposition [

36]. Their technology relies entirely on high-temperature plasma to drive the reaction, enabling the production of varying grades of solid carbon product (such as carbon black), claiming a 70% reduction in CO₂ emissions compared with conventional furnace-based carbon manufacturing methods. Their carbon black product is already applied in vehicle tyres in North America. Meanwhile, their hydrogen product is planned to be used to generate ammonia, for use in the fertiliser industry, helping to decarbonise agriculture [

37].

Meanwhile, HiiROC Ltd, is UK-based company which has developed a proprietary technology known as Thermal Plasma Electrolysis (TPE), using patented plasma torches to dissociate methane, reportedly enabling a more efficient and highly controlled process [

38]. Their process operates at elevated pressures (25 to 50 bar), and claims enhanced conversion rates and mass throughput. They have established strategic partnerships with industry players including Siemens (focussed on control systems for automation) [

39], and Cemex for applications of the technique in industrial settings such as cement plants [

40], and have secured a total of ~

$50 million in funding since 2019, with investors including Melrose Industries, HydrogenOne Capital Growth, Centrica, Hyundai, and Kia [

41,

42].

Levidian, a UK-based company, has also developed a microwave-based methane pyrolysis technology. Their patented LOOP method employs focussed microwaves in a low-temperature (around 1000˚C), at atmospheric pressure and catalyst-free process to create a methane plasma, decomposing the molecules into hydrogen and solid carbon in the form of graphene [

43]. They reported lack of catalysts, water, or other additives in this self-contained electrically powered reactor simplifies the solid carbon collection, improves the energy-efficiency of the process, and reduces environmental impact. Furthermore, the company claims that the system can be retrofitted to existing systems, and is ideal for on-site deployment at locations with any methane source, including landfill sites, biogas facilities, flare gas sites, or natural gas plants [

44]. Levidian's LOOP technology has garnered significant investment, securing £27 million in 2022 in a Series A funding round, and is currently pursuing Series B funding with a target of £50 million in early 2025 [

45].

2.5. Molten Metal /Salt Methane Pyrolysis

In molten metal salt methane pyrolysis, methane is thermally decomposed into hydrogen and solid carbon by passing it through a molten phase catalytic medium at high temperature. The molten phase material is typically a metal (such as tin, iron or nickel), a metal alloy (such as Ni-Co, Fe-Cr), or a metal salt (such as Ni-Bi, Cu-Bi) [

46], whilst methane gas is typically bubbled through this liquid (resulting in the system sometimes being known as a “bubble reactor”).

The molten material serves multiple roles in the reactor. It acts as a catalyst, decreasing the required temperature for breaking down methane into hydrogen and carbon. It acts as a reaction medium through which methane passes through and reacts, generating the products. It also acts as a heat transfer medium – the supply of thermal energy in this method is typically provided via resistive or induction heating [

46,

47]. Finally, the molten phase makes it relatively simple to separate the solid carbon product from the molten phase, since the relatively low density of carbon means it readily floats to the surface, where it can be collected, allowing the continuous production of hydrogen and carbon and preventing catalyst deactivation by carbon deposition [

48,

49].

The efficiency of this method is strongly influenced by the properties of the molten bath, including the melting temperature, thermal conductivity, and catalytic activity. Single-phase metals such as Fe, Cu, Bi, Sn, and Pb offer low melting points and high thermal conductivity but generally exhibit relatively low catalytic activity [

48]. To address this, metal alloys (e.g., Ni-Bi, Cu-Bi) can be used to enhance catalytic performance [

50], though they introduce the risk of metal contamination in the carbon byproduct. Meanwhile, metal / metal salt mixtures facilitate catalyst separation from the carbon product through simple processes like water washing, thanks to their low density and high solubility in water [

51]. Meanwhile, using pure molten salts leads to relatively low catalytic activity [

51], but is more cost-effective since salts typically have lower melting point compared to pure metals [

52].

Beyond material selection, several operational factors impact reaction rate and byproduct formation, including the feed system, molten material composition, and reactor temperature [

52]. These parameters all influence the structure of the resulting carbon.

Molten industries is an innovative USA-based startup founded in 2021, which hires resistive hearing in their molten metal/salt hydrogen pyrolysis processes. Their innovative approach integrates turquoise hydrogen from methane pyrolysis into the iron reduction process for the steel industry. They claim that their patented technology can reduce carbon dioxide emissions in iron reduction by up to 85% [

53]. The process involves the thermochemical decomposition of hydrocarbon feedstock in a horizontally aligned reactor with the electric heater. The reactor can operate either catalyst-free or catalyst-assisted (molten salts or metals inside the chamber). The molten material facilitates the reaction and serves as a collector for the carbon product. Depending on the choice of catalyst, the decomposition temperature can range from 400°C to over 1000°C, with a setup limit of 2000°C. While resistive heating is the default method, they claim their technology can also be adapted for induction heating and microwave heating [

54]. Their system achieves over 90% methane decomposition at 1200°C. Additionally, by varying thermal decomposition conditions, they have demonstrated the ability to produce hydrogen byproduct carbon in both amorphous and graphitic forms [

54].

In 2024, Molten Industries partnered with United States Steel Corporation and CPFD Software to develop a pilot system supplying clean hydrogen to a direct reduced iron (DRI) shaft furnace. This project, supported by a

$5.4 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy, aims to demonstrate carbon-neutral steel production [

55].

ExxonMobil has also developed a method that utilises electric heating to achieve the high temperatures necessary for methane pyrolysis. In a research paper published by Imperial College London and ExxonMobil [

47], they improved the carbon purity in the process to 91.6% without any acid or vacuum treatment by using NaCl, a thermodynamically stable, in-expensive and non-toxic salt. Also, they investigated NaBr, KBr, KCl, and eutectic mixture of NaBr:KBr (48.7 mol% and 51.3 mol%) in a liquid column at 1000 ˚C, which resulted in a lower melting point for the eutectic mixture.

ExxonMobil is pursuing potential market for the hydrogen produced by this method by manufacturing pyrolysis burners. It has installed 44 pyrolysis burners capable of operating on up to 100% hydrogen fuel in its Baytown, Texas facility [

56].

2.6. Fluidised Bed

The fluidised bed technique involves the suspension of solid particles (such as a catalyst, inert media, or a reactant) in an upward-flowing gas or liquid. At sufficient flow rate, the solid phase particles are physically agitated, creating a quasi-fluid-like state. This physical agitation enhances heat and mass transfer in the reactor, ensuring uniform temperature distribution and improved reaction kinetics. This technique is widely utilised in the chemical, petrochemical, energy, and environmental industries due to its ability to provide high surface area contact between reactants and catalysts, significantly improving process efficiency [

26,

57]. Its continuous operation makes it a scalable and industrially viable solution [

26,

58]. The effectiveness of the fluidised bed method is heavily dependent on key parameters such as particle size, temperature, and flow rate, all of which influence reaction stability and performance.

This technique has been considered in the context of hydrogen pyrolysis. However, a major challenge arises due to solid carbon accumulation on the fluidised catalyst particles during the reaction. This accumulation potentially leads to blockages, restricting gas flow through the reactor bed and affecting the fluidisation mechanics [

26]. Addressing this issue would be crucial for the viability of methane pyrolysis using fluidised bed reactors.

ExxonMobil has a patented fluidised bed for methane pyrolysis with electrical heating [

59]. The decomposition energy of the methane is provided through the coke particles heated by an electric heater to above 1000˚C to achieve methane conversion of over 60%. This heated coke can then be transferred to the main chamber, where the heat transfer between the coke particles and methane occurs.

3. Economic Feasibility and Byproducts Utilisation

This section explores the economic feasibility of methane pyrolysis, analysing the capital costs (CAPEX) and operational costs (OPEX), the energy requirements, and potential revenue streams. Methane pyrolysis technologies can generate emissions-free turquoise hydrogen from natural gas at relatively low cost, capturing carbon in an indefinitely stable solid form. In contrast, electrolysis can generate emissions-free green hydrogen from water, but the technique remains expensive and relies on large amounts of pure water. Directly comparing these two technologies in terms of hydrogen production costs will provide insight into their respective economic feasibilities and their potential for widespread adoption. The values are referenced from [

3,

60]. A simple comparison of the energy and cost requirements for turquoise and green hydrogen is presented below (

Table 1). For turquoise hydrogen, methane pyrolysis requires 5.2 kWh of electricity per kilogram of hydrogen produced. At an electricity price of £0.25 per kWh, the energy cost amounts to £1.30 per kg of hydrogen. Additionally, the process consumes 4 kg of methane per kg of hydrogen, where methane provides 14.5 kWh of energy per kg. Given a gas price of £0.063 per kWh, the cost of methane is calculated as £3.65 per kg of hydrogen. Summing both contributions, the estimated LCOH for turquoise hydrogen is £4.95 per kg.

For green hydrogen, electrolysis requires 39.4 kWh of electricity per kilogram of hydrogen produced. With the same electricity price of £0.25 per kWh, the energy cost reaches £9.85 per kg of hydrogen. The feedstock requirement includes 9 kg of water per kg of hydrogen, with a water price of £0.001 per kg, resulting in a negligible feedstock cost of £0.009 per kg of hydrogen. Consequently, the total LCOH for green hydrogen is £9.86 per kg, with the primary cost driver being electricity consumption.

The calculations indicate that the price of turquoise hydrogen is potentially around half that of green hydrogen, using the selected inputs, indicating a clear advantage of this process. It is also noted that the LCOH values quotes here are significantly higher than the ultimate targets for the cost of hydrogen (i.e. ~$1/kg), however this will be impacted significant by energy costs, which are expected to drop as the uptake of wind and solar increases. Importantly, the LCOH of turquoise hydrogen in the table does not consider the potential revenue from sales of the solid carbon byproduct. This is explored in more detail below.

A major advantage of methane pyrolysis for turquoise hydrogen production is the ability to sell the solid carbon byproduct as a high-value material. Depending on the process conditions, the resulting carbon can take the form of e.g. carbon black, graphite, graphene, or carbon nanotubes [

4,

62]. These carbon materials can then be used in other industrial applications, creating economic benefit, and can also potentially lead to environmental benefits across multiple industries by e.g. avoiding emissions in carbon manufacture.

Carbon black is a porous nanomaterial comprising clusters of spheroidal nanoparticles. It is made at vast scale via a spray-pyrolysis method, using petrochemicals a feedstock and fossil fuels to power the process. The material is used as e.g. a major component in car tyres (accounting for ~70% of carbon black production [

63]), as catalyst support, or as a black dye in plastics and paints. The global carbon black market is expected to grow from USD 20.6 billion in 2022 to USD 42.2 billion by 2032, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.9%. Meanwhile, the annual global production capacity of the carbon black is expected to increase by 1.4% over the same period. Importantly, the main producers of carbon black (such as Orion S.A [

64]) are shifting toward more sustainable manufacturing to reduce their CO2 footprint. Methane pyrolysis could provide a suitable alternative.

Graphite is the most familiar form of solid carbon to many people, being used as the writing element in pencils. It has high electrical and thermal conductivity, making it the material of choice for electrodes in batteries and heat sinks and as an element in electric motors [

62]. Most graphite occurs naturally in limestone deposits, and is mined, with significant associated emissions. Furthermore, natural graphite is classed as a critical raw material (CRM), meaning it has significant economic importance but is associated with supply chain risks. The global graphite market is projected to grow at a CAGR of 3.7% from 2024 to 2030, driven primarily by its increasing use lithium-ion batteries and as a refractory material. In particular, the use of graphite in lithium-ion battery production is expected to experience the highest revenue growth, with a CAGR of 4.4% over the forecast period, reflecting the rising demand for energy storage solutions [

65]. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), EV battery demand is projected to exceed 4,300 GWh per year by 2030, representing a five-fold increase over 2023 levels [

66]. Furthermore, market demand and supply projections predict a 10% shortfall in graphite production by 2035 [

67] [

68]. As such, this is another huge potential market for graphite produced by methane pyrolysis.

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are a relatively recent discovery and comprise tiny tubules of graphitic carbon. These have a long list of impressive properties, including extremely high electrical conductivity, resistance to corrosion, low density, and very high tensile strength. [

69] CNTs are gaining significant attention in energy storage technologies, aerospace applications, flame retardants, catalysis, photovoltaics, and structural reinforcement of plastics and concrete [

61,

70]. Traditionally, CNTs have been considered extremely expensive and niche materials. However, recent advancements in CNT manufacturing techniques, particularly chemical vapour deposition (CVD), have led to a significant reduction in production costs. The CNT market is forecast to grow at a CAGR exceeding 14% between 2024 and 2030. Multiwall CNTs occupy 93.6% of the market share, whilst single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) are expected to grow at a CAGR of 11.7% by 2030 [

71]. One particularly promising application for CNTs is to replace copper in electrical wiring. There is a shortfall between copper production (both by mining and recycling) and copper demand, creating a critical supply gap [

72], [

73] underscoring an urgent need for alternative materials, for which CNTs are a clear candidate. Companies such as DexMAT, Nanocomp Technologies, and Toray Industries have made significant advancements in CNT-based wire production, narrowing the performance gap between copper and carbon-based conductors. This presents a huge market opportunity for CNTs produced in a sustainable manner via methane pyrolysis.

Methane pyrolysis presents a compelling alternative to electrolysis for hydrogen production, offering a lower levelized cost of hydrogen while generating a valuable solid carbon byproduct. The economic viability of turquoise hydrogen is further enhanced by the potential revenue streams from carbon materials such as carbon black, graphite, and carbon nanotubes, each of which has expanding market demand across various industries. The ability to integrate methane pyrolysis into existing infrastructure, combined with the push toward sustainable carbon manufacturing, makes it a promising pathway for scaling up hydrogen production with reduced emissions. As energy prices continue to fluctuate and technological advancements drive down production costs, methane pyrolysis could play a crucial role in the transition toward a low-carbon economy.

4. Challenges and Future Direction

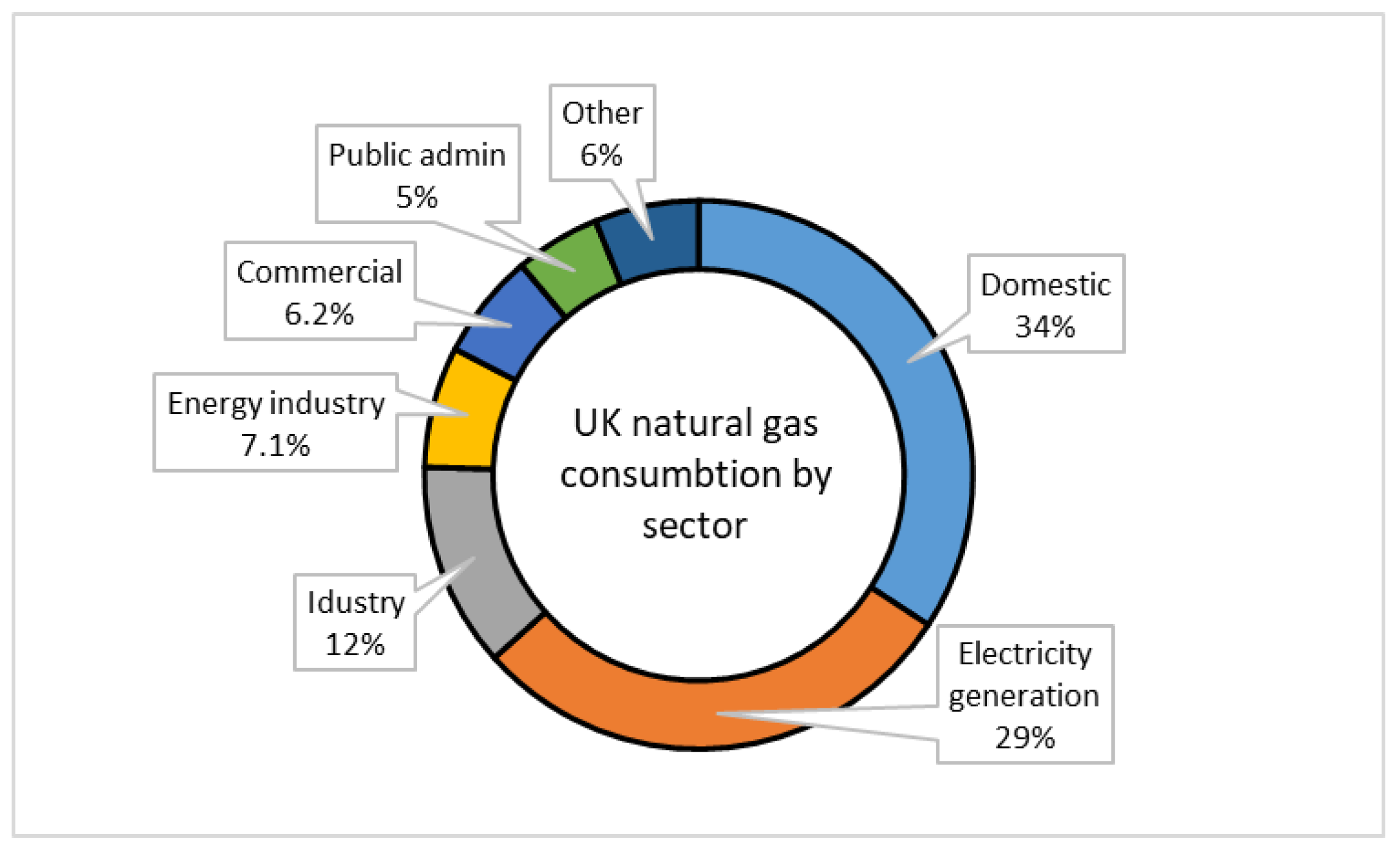

The reduction of emissions in the UK has been significantly influenced by the transition to natural gas from oil and coal. However, to achieve Net Zero by 2050, this sector still requires further decarbonisation, as, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), natural gas accounted for 46% of total CO₂ emissions from fuel combustion in the UK in 2022 [

75].

As shown in

Figure 3, the domestic sector, electricity generation, and industry are the three largest consumers of natural gas in the UK in 2023 [

76]. Domestic gas use includes space and water heating, as well as gas-powered appliances such as ovens and hobs [

76].

Policies on domestic heating have undergone significant changes in the past couple of years. A plan to phase out new gas boilers by 2035, stated in the policy announcement of September 2023 [

77], was scrapped in January 2025 [

78]. Obligations to replace gas boilers with heat pumps and restrictions on the installation of gas boilers in new houses were, therefore, abandoned. However, the Boiler Upgrade Scheme (BUS) was retained to encourage heat pump installations, offering grants of £7,500 [

78]. Although heat pumps are considered the primary mechanism for decarbonising the domestic sector, in 2025, the government will assess the latest evidence and consult on the role of hydrogen in home heating [

79].

The UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) caps emissions for large-scale emitting industries like power generation, heavy industry, and aviation. Companies that exceed their carbon emission limits must purchase allowances. UK Government applies a market-based approach in which natural gas users are expected to be stimulated to decarbonise through the ETS, since allowances tend to increase in price, creating a financial incentive to adopt low-carbon technologies [

79]. The ETS was introduced in 2021 as a replacement for the EU ETS. It is closely linked to the UK's Carbon Budgets, which were established under the Climate Change Act 2008 and are now being developed for every period of five years [

80]. This interconnection ensures that total UK emissions remain within national targets.

The UK Hydrogen Strategy Update 2024 recognises the potential of hydrogen in decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors, such as chemicals and heavy transport, complementing broader electrification efforts [

81]. Additionally, the government plans to review the viability of technologies such as the direct reduction of iron using natural gas or hydrogen for primary steel production [

81].

The previously mentioned policies and legislation are only part of the UK’s broader decarbonisation strategy for natural gas users. As evaluated by the Climate Change Committee (CCC), the effectiveness of these measures can be hindered by policy inconsistency. Policy reversals, delays, and mixed messaging present a major barrier to achieving the UK’s climate targets and have the potential to undermine consumer confidence and investor certainty [

82]. Currently, only one-third of the required emissions reductions are supported by credible plans [

82]. Additionally, the UK’s energy security strategy prioritises the long-term phase-out of natural gas consumption, which creates uncertainty for methane pyrolysis. The government has declared electrification as the primary means of decarbonising the oil and gas sector between 2027 and 2040 [

83,

84]. Within the UK’s hydrogen policy, there is strong support for blue and green hydrogen, while methane pyrolysis lacks clear backing.

In the UK Hydrogen Strategy (2021), methane pyrolysis is classified as a "nascent technology", with the next steps focused on R&D and innovation [

85]. While it acknowledges the potential of the technology, it also creates a sense of uncertainty, as there are no explicit commitments for scaling up its deployment.

UK’s commitment to the decarbonisation of natural gas users creates a fertile environment for the growth and expansion of hydrogen technology. Besides the widely acknowledged technologies for the production of blue and green hydrogen, new technologies, such as methane pyrolysis, play an important role in the technology mix. Therefore, for the successful further deployment of the hydrogen mix, it would be beneficial to enhance the consistency of the policy framework. A stable regulatory environment will boost investor confidence in innovation and enable a smoother transition for natural gas users.

5. Conclusion

The increasing demand for clean hydrogen production has driven significant advancements in electrified methane pyrolysis technologies, offering a low-emission and economically viable alternative to conventional hydrogen production methods. This review has explored the state-of-the-art approaches, including Joule heating, induction heating, microwave-assisted pyrolysis, plasma-based decomposition, molten metal reactors, and fluidised bed systems, highlighting their efficiencies, scalability, and potential for decarbonising industrial sectors. Among these methods, plasma and molten metal-based pyrolysis show promise in achieving high methane conversion rates and valuable carbon byproducts, while microwave and induction heating offer energy-efficient pathways with reduced operational costs.

Despite these advancements, challenges such as carbon deposition, energy consumption, reactor stability, and material selection remain critical barriers to widespread adoption. Further research is needed to optimise reactor designs, integrate renewable electricity sources, and enhance carbon byproduct utilisation to improve the overall feasibility of turquoise hydrogen production. Additionally, policy support, infrastructure development, and investment in emerging technologies will play a crucial role in accelerating commercialisation.

Looking ahead, short-term advancements are expected to focus on pilot-scale deployment and cost reduction, while medium-term efforts will likely refine efficiency and establish carbon markets. In the long-term, large-scale adoption of methane pyrolysis could reshape the global hydrogen economy, providing a sustainable and carbon-neutral energy carrier. With continued innovation and strategic collaboration between research institutions, industry leaders, and policymakers, electrified methane pyrolysis has the potential to become a cornerstone technology in the transition toward a clean hydrogen economy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and A.B.; methodology, H.R., S.L. and A.B.; software, H.R.; validation, H.R., S.L. and A.B.; formal analysis, H.R.; investigation, H.R. and G.S.; resources, S.L. and A.B.; data curation, H.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R., G.S., S.L. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, H.R., S.L. and A.B.; visualization, H.R., S.L. and A.B.; supervision, S.L. and A.B.; project administration, S.L. and A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scottish Enterprise, grant number PS7305132.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors wholeheartedly dedicate this study to the courageous people of Iran and Afghanistan, who continue to stand resolutely against oppression and tyranny. This work is made possible by the sacrifices of countless brave women and men who have lost their lives or freedom in the pursuit of fundamental human rights, allowing us to conduct our research beyond the reach of the brutal regimes in these nations. We honour the extraordinary resilience of imprisoned activists such as Fatemeh Sepehri and the memory of those who paid the ultimate price, including Kianoosh Sanjari, Mahsa Amini, Mursal Nabizada, Nika Shakarami, Hadis Najafi, Khodanur Lojei, Mohsen Shekari, Majidreza Rahnavard, Mohammad Hosseini, Mohammad Mehdi Karami, Yalda Aghafazli, Hamidreza Rouhi, Javad Rouhi, Ebrahim Rigi, Mohammad Moradi, Kian Pirfalak, Javad Heydari, and many others. Their unwavering bravery inspires this work and fuels the continuous pursuit of justice and freedom.

Conflicts of Interest

A.B. is the Founder of a prospective Strathclyde spinout, Entropyst.

References

- Global Warming of 1.5 ºC.

- Ritchie, H. Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from? Our World in Data 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shokrollahi, M.; Teymouri, N.; Ashrafi, O.; Navarri, P.; Khojasteh-Salkuyeh, Y. Methane pyrolysis as a potential game changer for hydrogen economy: Techno-economic assessment and GHG emissions. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 66, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busillo, E.; Nobili, A.; Serse, F.; Bracciale, M.P.; De Filippis, P.; Pelucchi, M.; de Caprariis, B. Turquoise hydrogen and carbon materials production from thermal methane cracking: An experimental and kinetic modelling study with focus on carbon product morphology. Carbon 2024, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Date, A.; Mahmood, N.; Kumar Das, R.; Shabani, B. Freshwater supply for hydrogen production: An underestimated challenge. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 78, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iberdrola.

- Chemistry, R.S.o. PFAS in UK watre - presence, detection, and remediation. 2023.

- Dargham, R.A. Water doesn't come from a tap. Unicef 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M. Where Water Stress Will Be Highest by 2050. 2024.

- Patlolla, S.R.; Katsu, K.; Sharafian, A.; Wei, K.; Herrera, O.E.; Mérida, W. A review of methane pyrolysis technologies for hydrogen production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I. 1.7 Energy and Exergy Efficiencies. In Comprehensive Energy Systems, Dincer, I., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2018; pp. 265–339. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Ambrosetti, M.; Tronconi, E. Joule-Heated Catalytic Reactors toward Decarbonization and Process Intensification: A Review. ACS Engineering Au 2023, 4, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, A.; Robertson, M.; Gunter, Z.; Coronado, A.; Xiang, Y.; Qiang, Z. Design and Application of Joule Heating Processes for Decarbonized Chemical and Advanced Material Synthesis. Ind Eng Chem Res 2024, 63, 19398–19417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, Y.; Haraguchi, M.; Matsukata, M.; Kikuchi, E. Low temperature steam reforming of methane over metal catalyst supported on CexZr1−xO2 in an electric field. Catalysis Today 2011, 171, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieks, M.; Bellinghausen, R.; Kockmann, N.; Mleczko, L. Experimental study of methane dry reforming in an electrically heated reactor. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 15940–15951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnakar, R.R.; Balakotaiah, V. Sensitivity analysis of hydrogen production by methane reforming using electrified wire reactors. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Yao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Alexopoulos, K.; Gao, J.; Srinivas, S.; Wang, Y.; Pei, Y.; Zheng, C.; Brozena, A.H.; et al. Programmable heating and quenching for efficient thermochemical synthesis. Nature 2022, 605, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renda, S.; Cortese, M.; Iervolino, G.; Martino, M.; Meloni, E.; Palma, V. Electrically driven SiC-based structured catalysts for intensified reforming processes. Catalysis Today 2022, 383, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, P.M.; Engbæk, J.S.; Vendelbo, S.B.; Hansen, M.F.; Østberg, M. Direct Hysteresis Heating of Catalytically Active Ni–Co Nanoparticles as Steam Reforming Catalyst. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2017, 56, 14006–14013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinum, M.G.; Almind, M.R.; Engbaek, J.S.; Vendelbo, S.B.; Hansen, M.F.; Frandsen, C.; Bendix, J.; Mortensen, P.M. Dual-Function Cobalt-Nickel Nanoparticles Tailored for High-Temperature Induction-Heated Steam Methane Reforming. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2018, 57, 10569–10573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, J.M.; Loriers-Susse, C.; Vodar, B. Pressure Effect on the Curie Temperatures of Transition Metals and Alloys. Physical Review B 1972, 6, 4250–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Camacho, M.N.; Abu-Dahrieh, J.; Rooney, D.; Sun, K. Biogas reforming using renewable wind energy and induction heating. Catalysis Today 2015, 242, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong-Phuoc, L.; Duong-Viet, C.; Nhut, J.M.; Pappa, A.; Zafeiratos, S.; Pham-Huu, C. Induction Heating for the Electrification of Catalytic Processes. ChemSusChem 2024, e202402335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.; Fidalgo, B.; Fernández, Y.; Pis, J.J.; Menéndez, J.A. Microwave-assisted catalytic decomposition of methane over activated carbon for CO2-free hydrogen production. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 4792–4799. [Google Scholar]

- Dadsetan, M.; Khan, M.F.; Salakhi, M.; Bobicki, E.R.; Thomson, M.J. CO2-free hydrogen production via microwave-driven methane pyrolysis. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 14565–14576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.K.; Han, G.Y.; Yoon, K.J.; Lee, B.K. Thermocatalytic hydrogen production from the methane in a fluidised bed with activated carbon catalyst. Catalysis Today 2004, 93-95, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Botella, E.; Peumans, D.; Vandersteen, G.; Baron, G.V.; Catalá-Civera, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Cano, J.D.; Van Assche, G.; Costa Cornellà, A.; Denayer, J.F.M. Challenges in the microwave heating of structured carbon adsorbents. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 476, 146632. [Google Scholar]

- Salakhi, M.; Thomson, M.J. A particle-scale study showing microwave energy can effectively decarbonise process heat in fluidisation industry. iScience 2025, 28, 111732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Liddo, L.; Cepeda, F.; Saegh, G.; Salakhi, M.; Thomson, M.J. Comparative analysis of methane and natural gas pyrolysis for low-GHG hydrogen production. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 84, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadsetan, M.; Latham, K.G.; Khan, M.F.; Zaher, M.H.; Manzoor, S.; Bobicki, E.R.; Titirici, M.M.; Thomson, M.J. Characterization of carbon products from microwave-driven methane pyrolysis. Carbon Trends 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P. INTERVIEW, Our microwave-based turquoise hydrogen technology is more energy and cost-efficient than any electrolyser. Hydrigeninsight.com 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T. Scaling Low-Carbon Hydrogen: How Aurora Hydrogen's Methane Pyrolysis Technology Is Paving the Way for a Net-Zero Future. decarbonfuse.com 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wnukowski, M. Methane Pyrolysis with the Use of Plasma: Review of Plasma Reactors and Process Products. Energies 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Sunarso, J.; Li, C.; Pham, G.H.; Phan, C.; Liu, S. Microwave-assisted catalytic methane reforming: A review. Applied Catalysis A: General 2020, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Bajohr, S.; Graf, F.; Kolb, T. State of the Art of Hydrogen Production via Pyrolysis of Natural Gas. ChemBioEng Reviews 2020, 7, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S.; Bajohr, S.; Graf, F.; Kolb, T. Verfahrensübersicht zur Erzeugung von Wasserstoff durch Erdgas-Pyrolyse. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2020, 92, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Monolith Process. 2025.

- Ltd, H.

- Jenkins, S. Hydrogen Production. 2024.

- Cemex Ventures increases investment in HiiROC; thermal plasma electrolysis for hydrogen production. 2023.

- HiiROC completes major funding round.

- Tracxn.com.

- Hydrogen Europ, D. Pyrolysis. Potential and possible applications of a climatefriendly hydrogen production. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- (BEIS), D.f.B.E.a.I.S. The sustainable biogas, graphene and hydrogen LOOP – Phase 1. 2022.

- Savage, M. We’re going after the hard-to-crack problem heavy industry. 2025.

- Sorcar, S.; Rosen, B.A. Methane Pyrolysis Using a Multiphase Molten Metal Reactor. ACS Catalysis 2023, 13, 10161–10166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, B.; Patzschke, C.F.; Nikolis, D.; Raman, S.; Dankworth, D.C.; Hellgardt, K. Methane pyrolysis in monovalent alkali halide salts: Kinetics and pyrolytic carbon properties. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 6225–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhao, D.; Dong, L.; Qian, J.; Niu, Y.; Ma, X. Research advances of molten metal systems for catalytic cracking of methane to hydrogen and carbon. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 83, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostrup-Nielsen, J.; Trimm, D.L. Mechanisms of carbon formation on nickel-containing catalysts. Journal of Catalysis 1977, 48, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C.; Tarazkar, M.; Kristoffersen, H.H.; Gelinas, J.; Gordon, M.J.; McFarland, E.W.; Metiu, H. Methane Pyrolysis with a Molten Cu–Bi Alloy Catalyst. ACS Catalysis 2019, 9, 8337–8345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, D.C.; Agarwal, V.; Khechfe, A.; Snodgrass, Z.R.; Gordon, M.J.; Metiu, H.; McFarland, E.W. Catalytic molten metals for the direct conversion of methane to hydrogen and separable carbon. Science 2017, 358, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmi, A.R.; Hanifi, A.R.; Shahbakhti, M. Techno-economic analysis of a novel concept for the combination of methane pyrolysis in molten salt with heliostat solar field. Energy 2024, 301, 131644. [Google Scholar]

- Inc. , M.I. System and method for methane pyrolysis driven reduced iron production using integrated thermal management. Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Inc. , M.I. A decomposition reactor for pyrolysis of hydrocarbon feedstock. Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Voloschuk, C. Molten Industries leads partnership to develop carbon neutral steel production. 2024.

- ExxonMobil. Baytown breakthrough: Our next-generation hydrogen burner can help decarbonise a key industry. 2025.

- Pathak, S.; McFarland, E. Iron Catalyzed Methane Pyrolysis in a Stratified Fluidized Bed Reactor. Energy & Fuels 2024, 38, 12576–12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bastardo, N.; Schlögl, R.; Ruland, H. Methane Pyrolysis for CO2-Free H2 Production: A Green Process to Overcome Renewable Energies Unsteadiness. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2020, 92, 1596–1609. [Google Scholar]

- ExxonMobil. Methane pyrolysis using stacked fluidised beds with electric heating of coke. Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) 2020. WO2022081170A1. [Google Scholar]

- (IRENA), I.R.E. Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction. 2020.

- Helen Uchenna Modekwe, O.O.A.; Matthew Adah Onu, N.T.T.; Messai Adenew Mamo, K.M., Michael Olawale Daramola; Olubambi, a.P.A. The Current Market for Carbon Nanotube Materials and Products. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Karamveer, S.; Thakur, V.K.; Siwal, S.S. Synthesis and overview of carbon-based materials for high performance energy storage application: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 56, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Carbon Black Market Demand & Forecast Analysis, 2016-2032.

- S.A., O. Sustainable Report 2023. 2023.

- Graphite Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report.

- Agency, I.R.E. Critical Material-Batteries for Electric Vehicles. 2024.

- (IEA), I.E.A. 2024.

- Zhang, J.; Liang, C.; Dunn, J.B. Graphite Flows in the U.S.: Insights into a Key Ingredient of Energy Transition. Environ Sci Technol 2023, 57, 3402–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C.E.; Vondrasek, B.; Jolowsky, C.N.; Park, J.G.; Czabaj, M.W.; Ku, B.E.; Thagard, K.R.; Odegard, G.M.; Liang, Z. Scalable High Tensile Modulus Composite Laminates Using Continuous Carbon Nanotube Yarns for Aerospace Applications. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2023, 6, 11260–11268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modekwe, H.U.; Olaitan Ayeleru, O.; Onu, M.A.; Tobias, N.T.; Mamo, M.A.; Moothi, K.; Daramolad, M.O.; Olubambi, P.A. The Current Market for Carbon Nanotube Materials and Products. In Handbook of Carbon Nanotubes; 2021; pp. 1-15.

- Global Carbon Nanotubes Market Size & Outlook, 2024-2030. 2024.

- (IEA), I.E.A. Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024. 2024.

- Forum, I.E. How copper shortages threaten the energy transition. 2024.

- Carbon Nanotubes Market Size & Trends. 2024.

- International Energy Agency (IEA), n.d. UK Natural gas. 2022.

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ). Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics (DUKES) 2024: Chapter 4- Natural Gas. 2024.

- Zero., U.G.D.f.E.S.a.N. Powering Up Britain: Net Zero Growth Plan. 2023.

- Horton, H. UK government scraps plan to ban sale of gas boilers by 2035. The Guardian, 6 January, 6 January.

- Government, U. Hydrogen Heating Overview. 2024.

- Government, U. Climate Change Act 2008. 2008.

- UK Government, D.f.E.S.a.N.Z. Hydrogen Strategy Update to the Market 2024.

- (CCC), C.C.C. Progress Snapshot: UK Action on Climate Change. 2024.

- Government, U. PM speech on Net Zero: . 2023. 20 September.

- Government, U. Expanding and strengthening the UK Emissions Trading Scheme. 2023.

- UK Government, D.f.B. , Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS). UK Hydrogen Strategy. 2021. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).