Submitted:

27 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

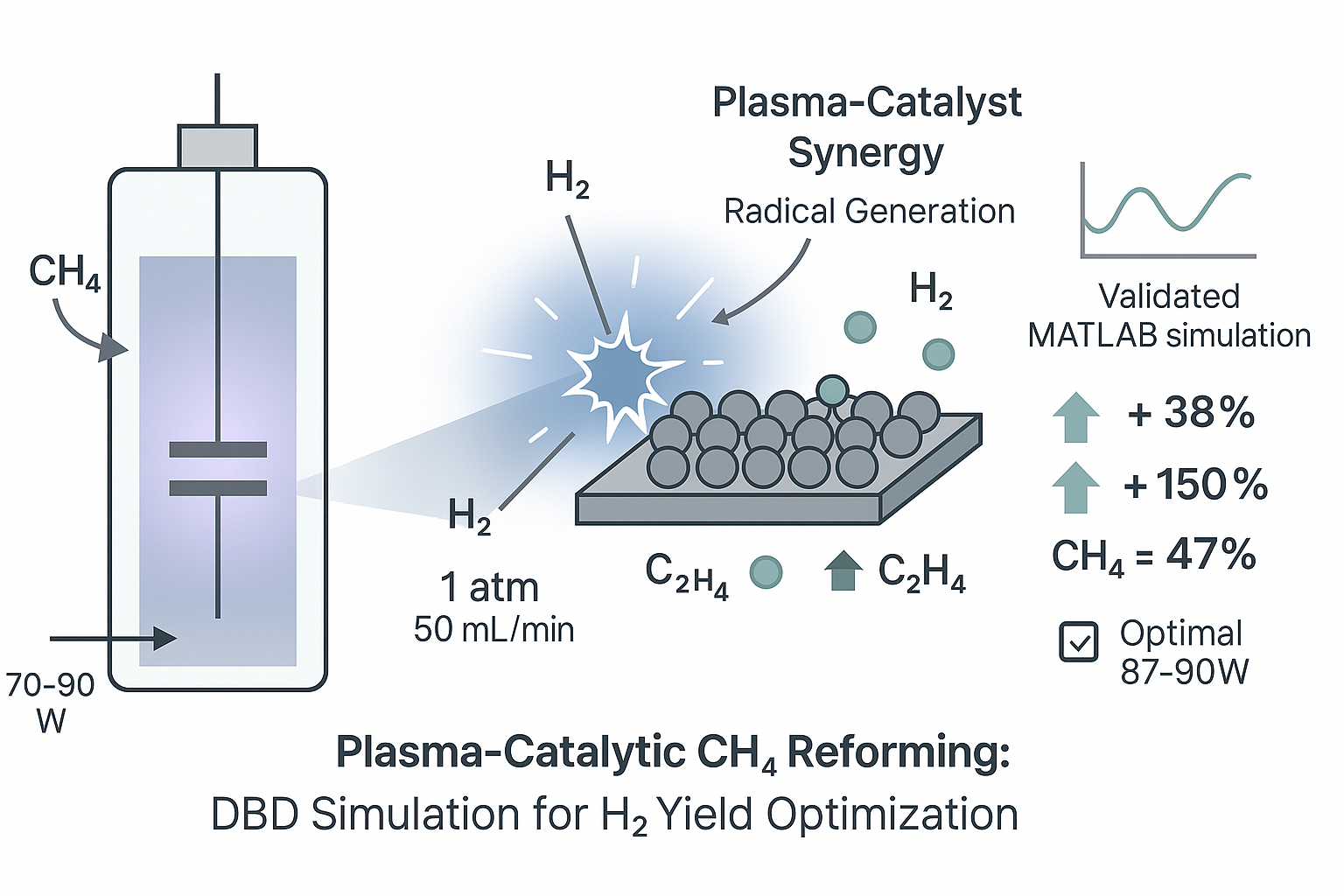

2.1. System Overview and Simulation Objective

- Discharge power: 70 W

- Pressure: 1 atm

- Flow rate: 50 mL/min

2.2. Reaction Network and Mechanism Description

2.2.1. Gas-Phase Reaction Pathways

- Electron-impact dissociation

- Radical recombination

- Hydrogen formation

2.2.2. Surface Reaction Pathways (Catalyst Enabled)

2.3. Plasma Kinetic Modeling

2.3.1. Species Mass Balance

- i.

- is the concentration of species i

- ii.

- is the stoichiometric coefficient

- iii.

- is the rate of reaction j

2.3.2. Electron Energy Balance

- P is the applied discharge power

- V is the reactor volume

- is the electron density

- is energy loss per reaction k

2.3.3. Electron Temperature

2.3.4. Rate Coefficients for Electron-Impact Reactions

- is the cross-section

- is the energy distribution function (assumed Maxwellian)

- is electron velocity

2.4. Simulation Framework and Numerical Method

2.5. Parametric Study Design

2.6. Performance Metrics

2.7. Validation Strategy

3. Results and Discussions

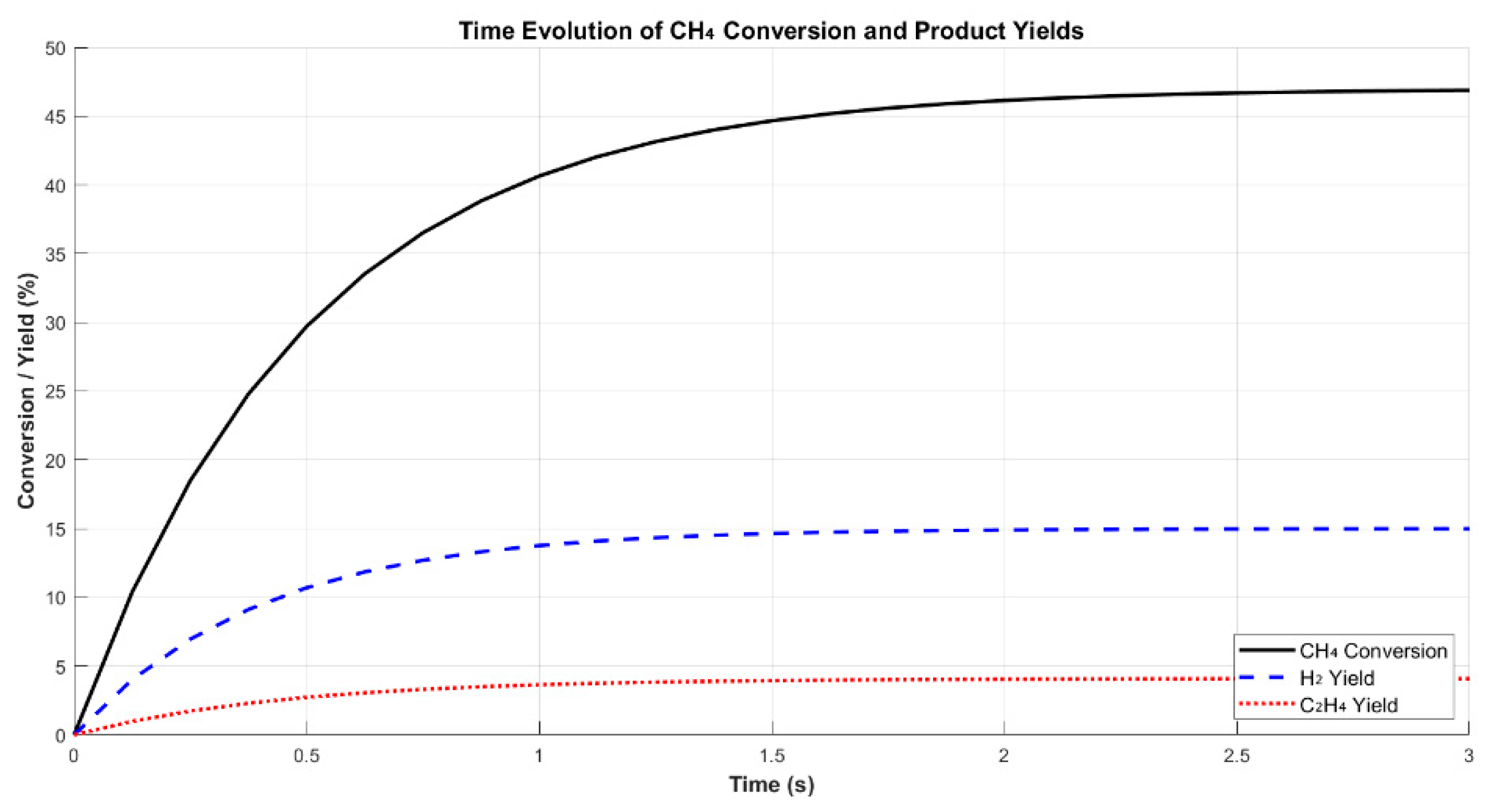

3.1. Base Case Performance Analysis

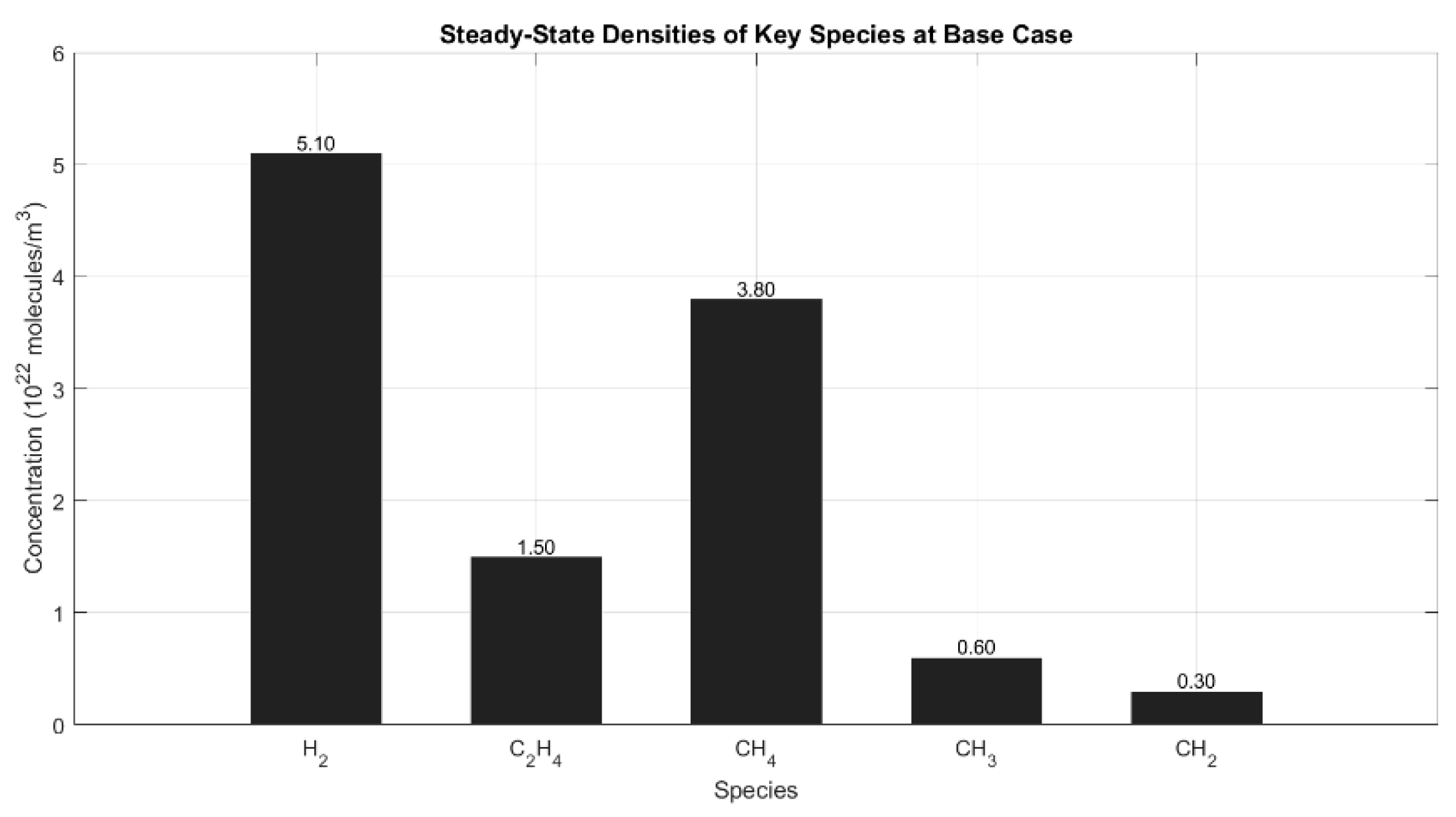

3.1.1. Steady-State Species Densities

3.1.2. Product Distribution and Selectivity

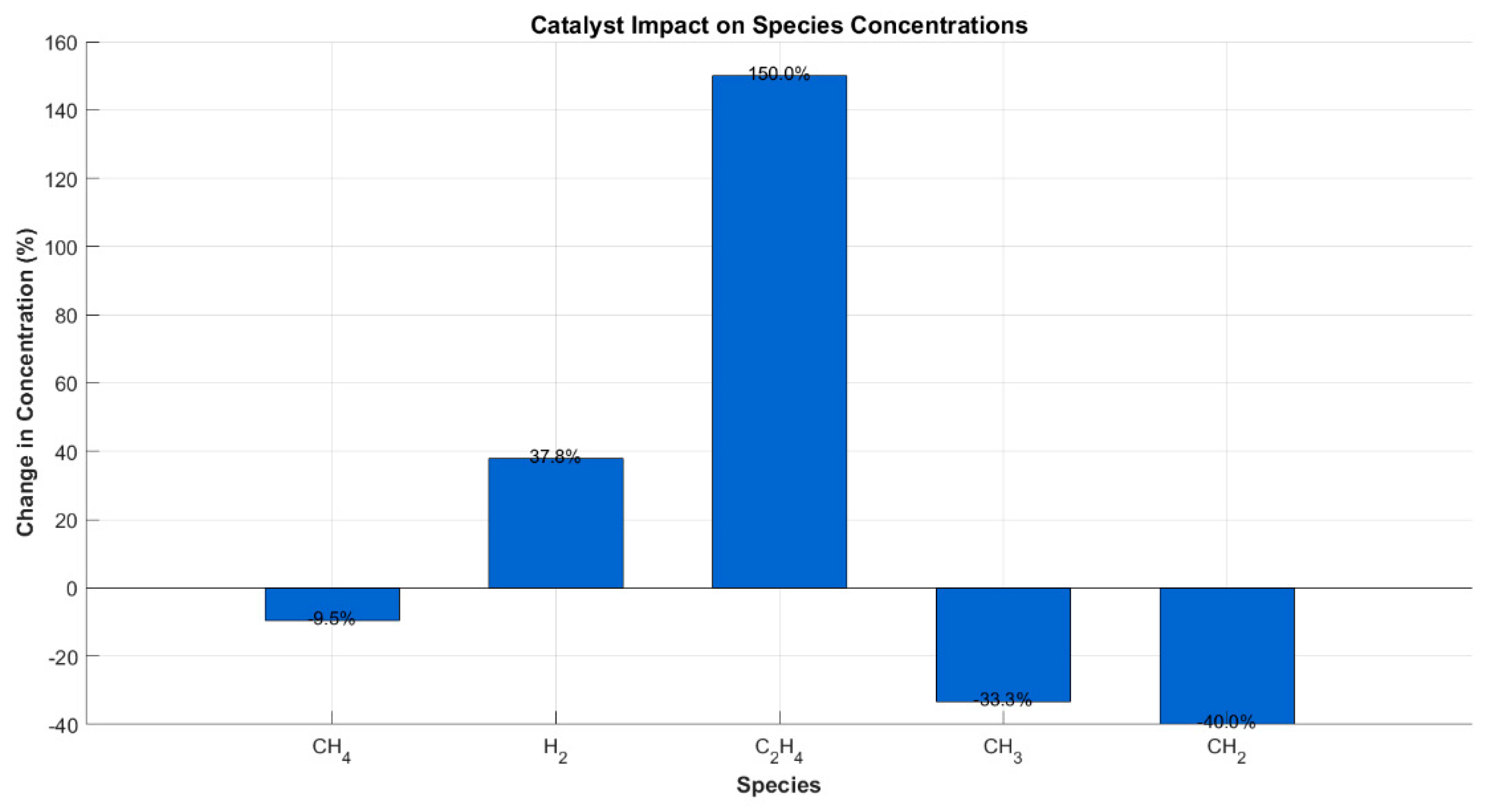

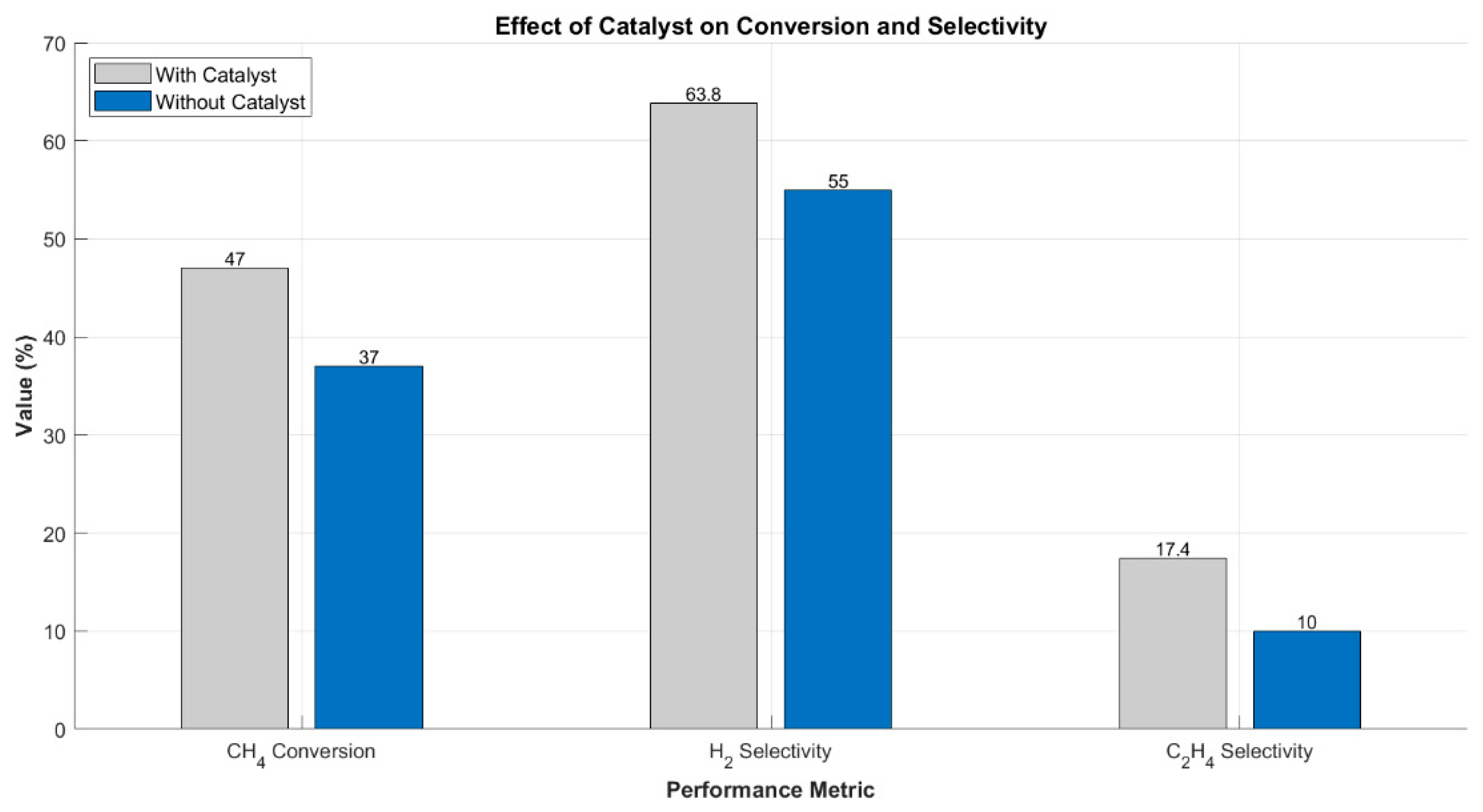

3.2. Catalyst Effect Study

3.3. Plasma Properties

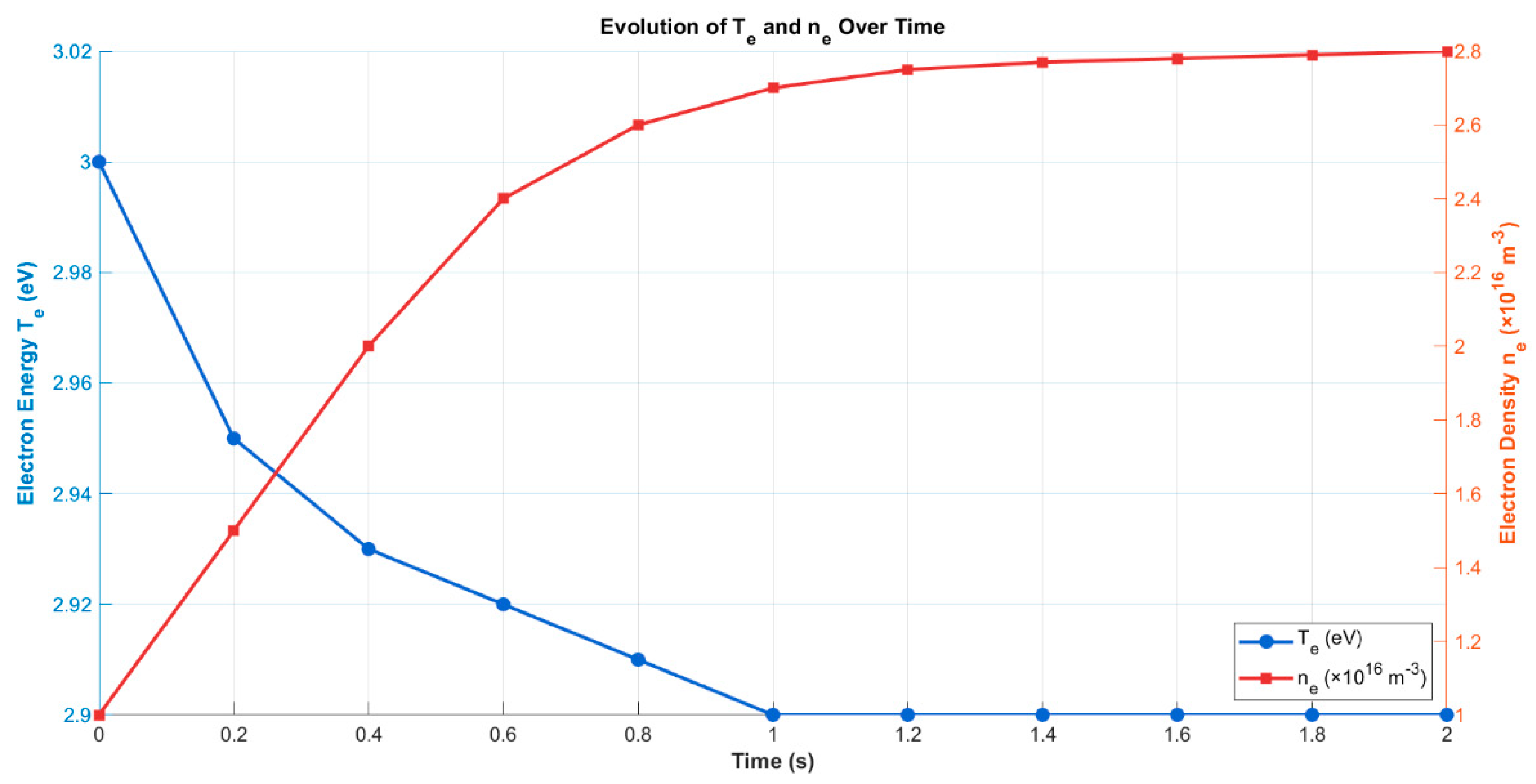

3.3.1. Electron Energy and Electron Density

3.4. Parametric Study

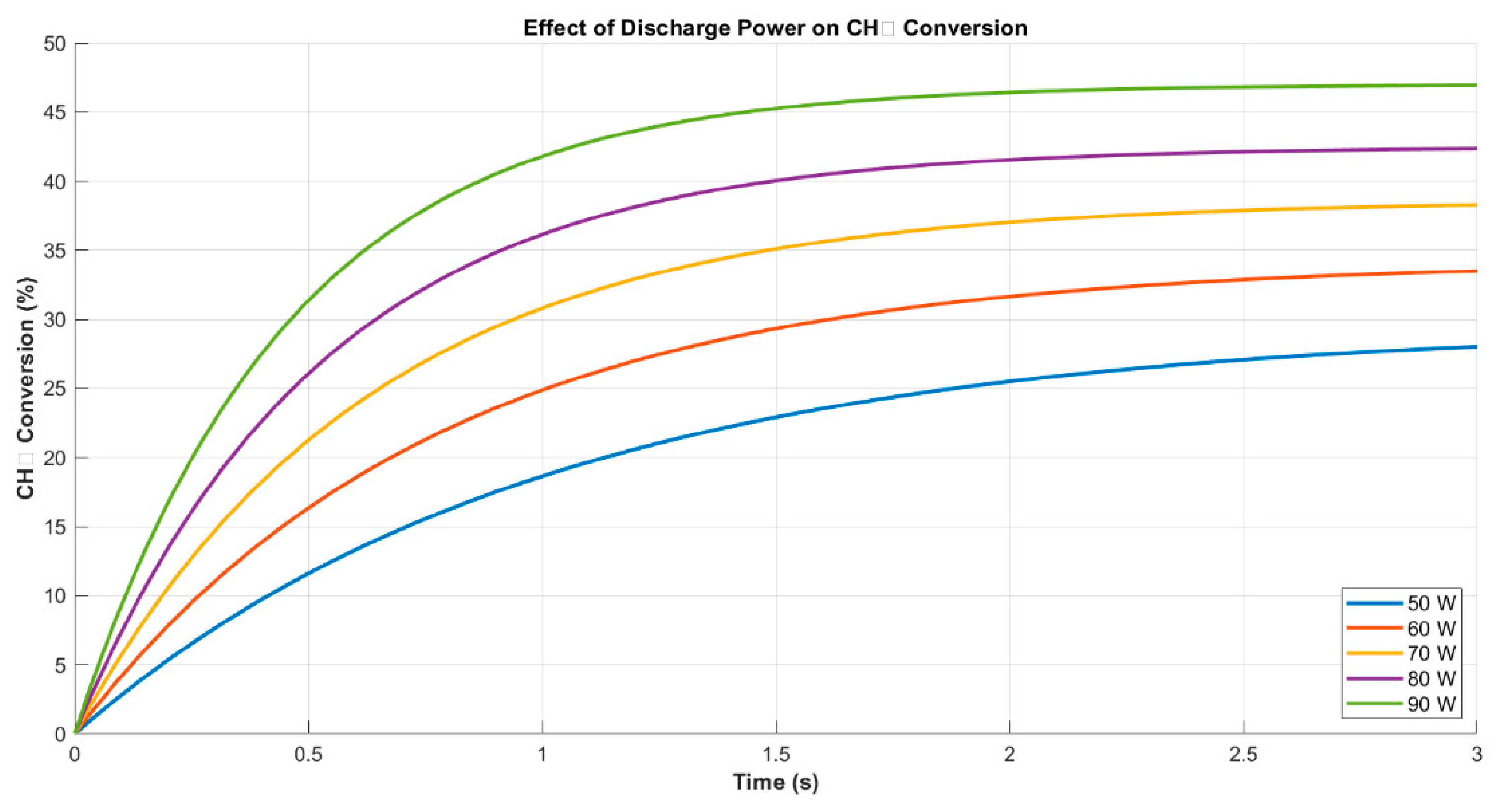

3.4.1. Effect of Discharge Power

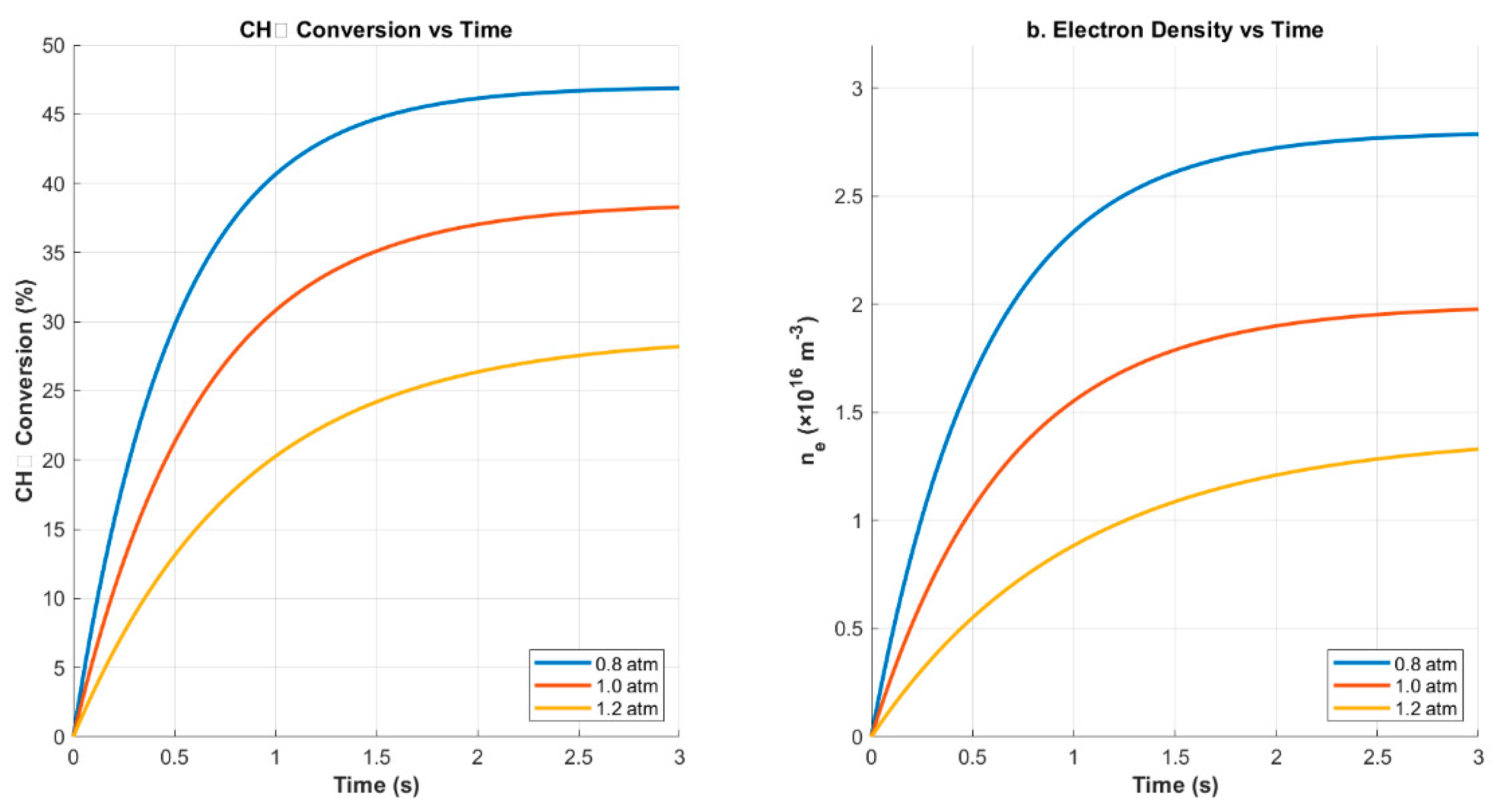

3.4.2. Effect of Pressure

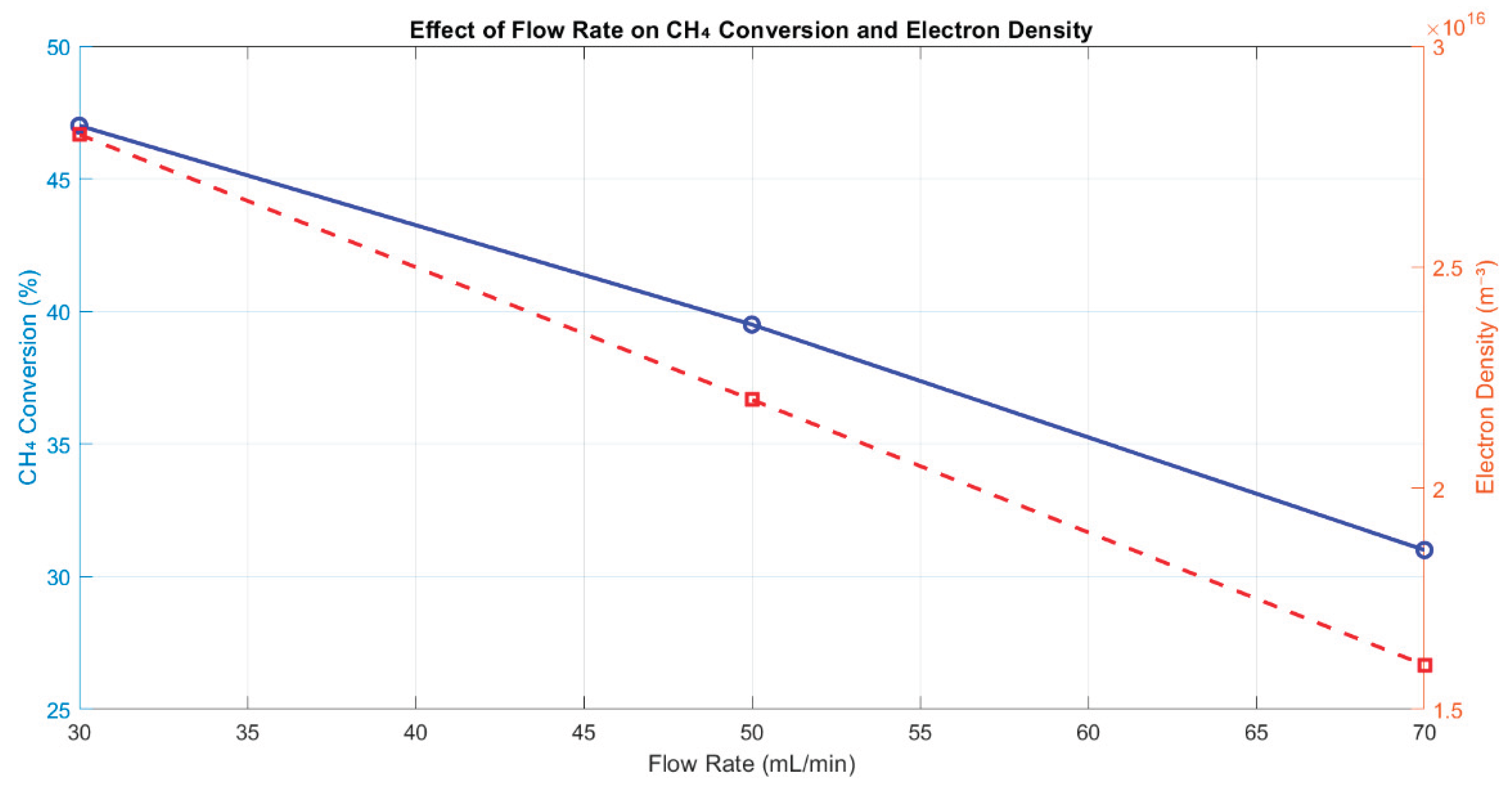

3.4.3. Effect of Flow Rate

3.5. Sensitivity and Validation

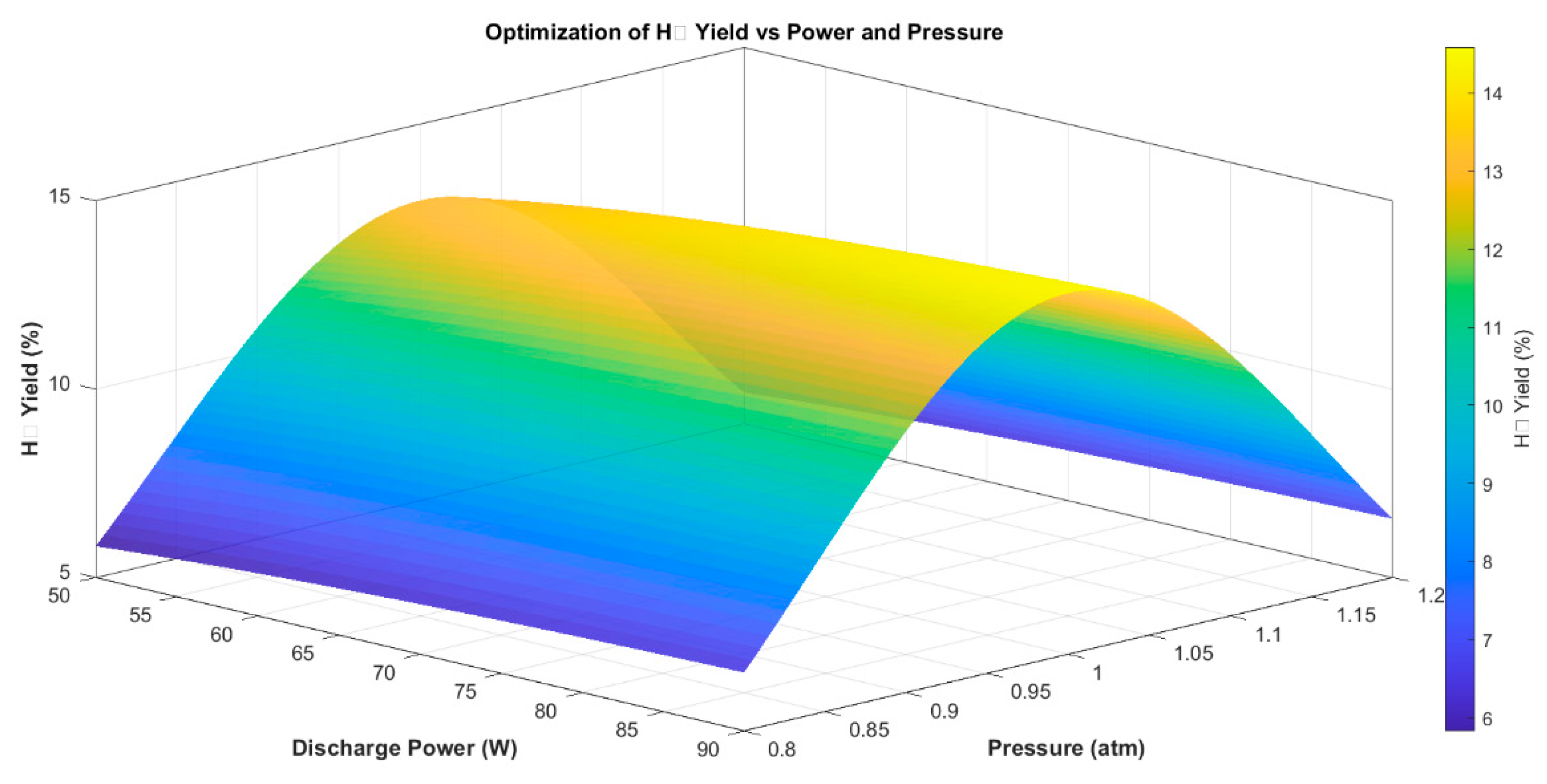

3.6. Process Optimization

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amghizar, L. A. Vandewalle, K. M. Van Geem, and G. B. Marin. New Trends in Olefin Production. Engineering 2017, 3, 171–178. [CrossRef]

- Mynko et al., “Reducing CO2 emissions of existing ethylene plants: Evaluation of different revamp strategies to reduce global CO2 emission by 100 million tonnes. J Clean Prod 2022, 362, 132127. [CrossRef]

- M. Scapinello, E. Delikonstantis, and G. D. Stefanidis. The panorama of plasma-assisted non-oxidative methane reforming. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification 2017, 117, 120–140. [CrossRef]

- E. Delikonstantis, F. Cameli, M. Scapinello, V. Rosa, K. M. Van Geem, and G. D. Stefanidis. Low-carbon footprint chemical manufacturing using plasma technology. Curr Opin Chem Eng, 2022; 38, 100857. [CrossRef]

- Wnukowski, M. Methane Pyrolysis with the Use of Plasma: Review of Plasma Reactors and Process Products. Energies 2023, 16, 6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Lamichhane et al. Critical review: ‘Green’ ethylene production through emerging technologies, with a focus on plasma catalysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024; 189, 114044. [CrossRef]

- C. Shen, D. Sun, and H. Yang. Methane coupling in microwave plasma under atmospheric pressure. Journal of Natural Gas Chemistry, 2011; 20, 449–456. [CrossRef]

- S. Heijkers, M. Aghaei, and A. Bogaerts. Plasma-Based CH4 Conversion into Higher Hydrocarbons and H2: Modeling to Reveal the Reaction Mechanisms of Different Plasma Sources. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2020; 124, 7016–7030. [CrossRef]

- R. Liu et al. Hybrid plasma catalysis-thermal system for non-oxidative coupling of methane to ethylene and hydrogen. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2024; 498, 155733. [CrossRef]

- E. Morais, E. Delikonstantis, M. Scapinello, G. Smith, G. D. Stefanidis, and A. Bogaerts. Methane coupling in nanosecond pulsed plasmas: Correlation between temperature and pressure and effects on product selectivity. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2023; 462, 142227. [CrossRef]

- F. Cameli, M. Scapinello, E. Delikonstantis, and G. D. Stefanidis. Electrified methane upgrading via non-thermal plasma: Intensified single-pass ethylene yield through structured bimetallic catalyst. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification, 2024; 204, 109946. [CrossRef]

- M. Scapinello, E. Delikonstantis, and G. D. Stefanidis. Direct methane-to-ethylene conversion in a nanosecond pulsed discharge. Fuel, 2018; 222, 705–710. [CrossRef]

- E. Delikonstantis et al. Valorizing the Steel Industry Off-Gases: Proof of Concept and Plantwide Design of an Electrified and Catalyst-Free Reverse Water–Gas-Shift-Based Route to Methanol. Environmental Science & Technology, 2023; 57, 14961–14972. [CrossRef]

- E. Morais, F. Cameli, G. D. Stefanidis, and A. Bogaerts. Selective catalytic hydrogenation of C2H2 from plasma-driven CH4 coupling without extra heat: mechanistic insights from micro-kinetic modelling and reactor performance. EES Catalysis, 2025; 3, 475–487. [CrossRef]

- S. Ravasio and C. Cavallotti. Analysis of reactivity and energy efficiency of methane conversion through non thermal plasmas. Chem Eng Sci. 2012; 84, 58–590. [CrossRef]

- E. Delikonstantis, M. Scapinello, O. Van Geenhoven, and G. D. Stefanidis. Nanosecond pulsed discharge-driven non-oxidative methane coupling in a plate-to-plate electrode configuration plasma reactor. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020; 380, 122477. [CrossRef]

- E. Delikonstantis, M. Scapinello, and G. D. Stefanidis. Low energy cost conversion of methane to ethylene in a hybrid plasma-catalytic reactor system. Fuel Processing Technology, 2018; 176, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- P.-A. Maitre, M. S. Bieniek, and P. N. Kechagiopoulos. Modelling excited species and their role on kinetic pathways in the non-oxidative coupling of methane by dielectric barrier discharge. Chem Eng Sci, 2021; 234, 116399. [CrossRef]

- K. van ‘t Veer, F. Reniers, and A. Bogaerts. Zero-dimensional modeling of unpacked and packed bed dielectric barrier discharges: the role of vibrational kinetics in ammonia synthesis. Plasma Sources Sci Technol, 2020; 29, 45020. [CrossRef]

- B. Wanten, R. Vertongen, R. De Meyer, and A. Bogaerts. Plasma-based CO2 conversion: How to correctly analyze the performance? 2023; 86, 180–196. [CrossRef]

- N. Budhraja, A. Pal, and R. S. Mishra. Plasma reforming for hydrogen production: Pathways, reactors and storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy, 2023; 48, 2467–2482. [CrossRef]

- J. Medford et al. CatMAP: A Software Package for Descriptor-Based Microkinetic Mapping of Catalytic Trends. Catal Letters 2015, 145, 794–807. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gao, S. Zhang, H. Sun, R. Wang, X. Tu, and T. Shao. Highly efficient conversion of methane using microsecond and nanosecond pulsed spark discharges. Appl Energy 2018, 226, 534–545. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, Y. Gao, H. Sun, H. Bai, R. Wang, and T. Shao. Time-resolved characteristics and chemical kinetics of non-oxidative methane conversion in repetitively pulsed dielectric barrier discharge plasmas. J Phys D Appl Phys 2018, 51, 274005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. C. Neyts, K. (Ken) Ostrikov, M. K. Sunkara, and A. Bogaerts. Plasma Catalysis: Synergistic Effects at the Nanoscale. Chem Rev 2015, 115, 13408–13446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y. Engelmann, P. Mehta, E. C. Neyts, W. F. Schneider, and A. Bogaerts. Predicted Influence of Plasma Activation on Nonoxidative Coupling of Methane on Transition Metal Catalysts. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2020, 8, 6043–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Horn and R. Schlögl. Methane Activation by Heterogeneous Catalysis. Catal Letters 2014, 145, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. J. Carman and R. P. Mildren. Electron energy distribution functions for modelling the plasma kinetics in dielectric barrier discharges. J Phys D Appl Phys 2000, 33, L99–L103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Lieberman and S. Ashida. Global models of pulse-power-modulated high-density, low-pressure discharges. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 1996, 5, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbatt et al. Concepts, Capabilities, and Limitations of Global Models: A Review. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2016, 14. [CrossRef]

- T. Butterworth et al. Plasma induced vibrational excitation of CH4—a window to its mode selective processing. Plasma Sources Sci Technol, 2020; 29, 95007. [CrossRef]

| CH4 Conversion (%) | H2 Yield (%) | C2H4 Yield (%) | H2 Selectivity (%) | C2H4 Selectivity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29.5 | 11.8 | 2.6 | 80.2 | 17.5 |

| 34.2 | 12.9 | 3.1 | 75.4 | 18.1 |

| 38.6 | 13.7 | 3.5 | 70.9 | 18.0 |

| 42.5 | 14.3 | 3.8 | 67.2 | 17.8 |

| 47.0 | 15.0 | 4.1 | 63.8 | 17.4 |

| 51.1 | 15.5 | 4.4 | 60.5 | 17.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).