Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

18 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fuel Cell Configuration and Simulation Setup

2.2. Electrochemical Reactions and Thermodynamic Modeling

| Reaction Type | Anode/Cathode Reaction | Global Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| PEMFC | Hydrogen Oxidation: H2(g)→2H++2e− (Anode) Oxygen Reduction: O2/2(g)+2H+2e−→H2O(g) (Cathode) |

H₂(g) + ½O₂(g) → H₂O(g) |

| DMFC | Methanol Oxidation (DMFC): CH3OH(g)+6OH−→CO2(g)+5H2O(g)+6e− Oxygen Reduction (DMFC): 3/2O2(g)+3H2O+6e−→6OH− |

CH₃OH(g) + ³⁄₂O₂(g) → CO₂(g) + H₂O(g) |

2.3. Electrochemical Performance Evaluation

-

Activation Losses: Derived from the Butler-Volmer equation:i_c = i₀_c · exp((α·O₂·F)/(R·T) · (E(T) − E⁰₂₉₈))

- Ohmic Losses: Related to membrane resistance and electrode geometry.

- Concentration Losses: Influenced by mass transfer limitations in porous media.

3. Results

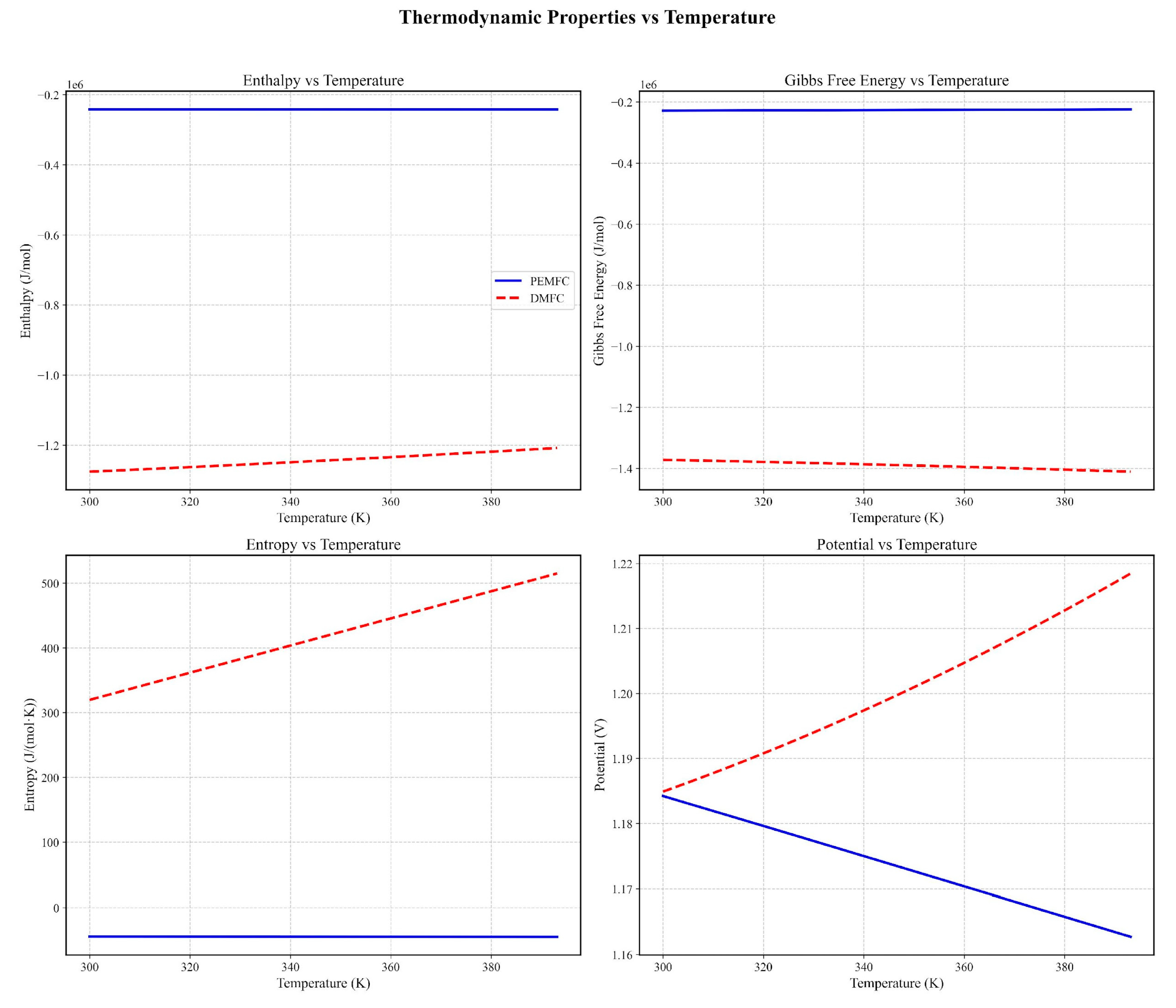

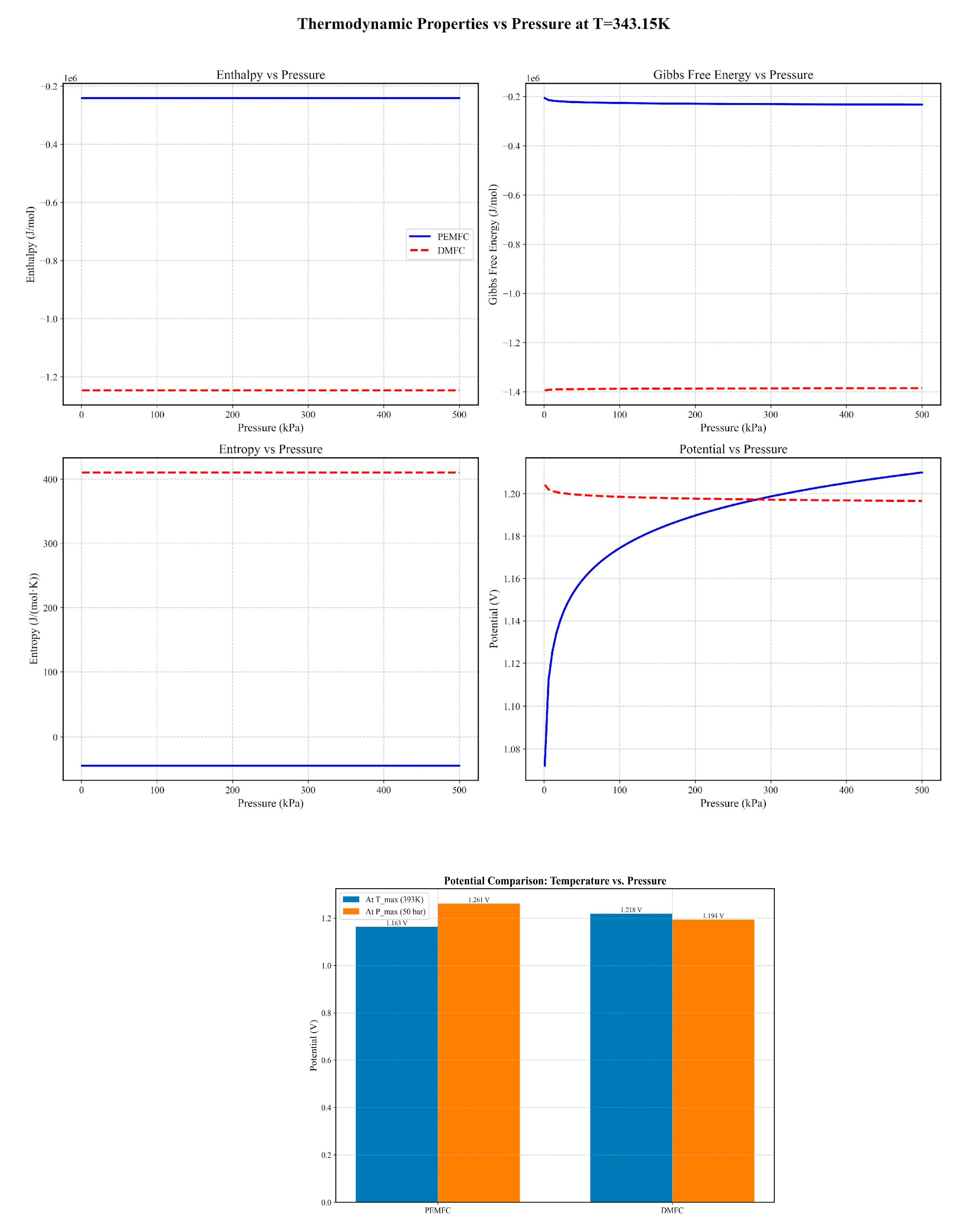

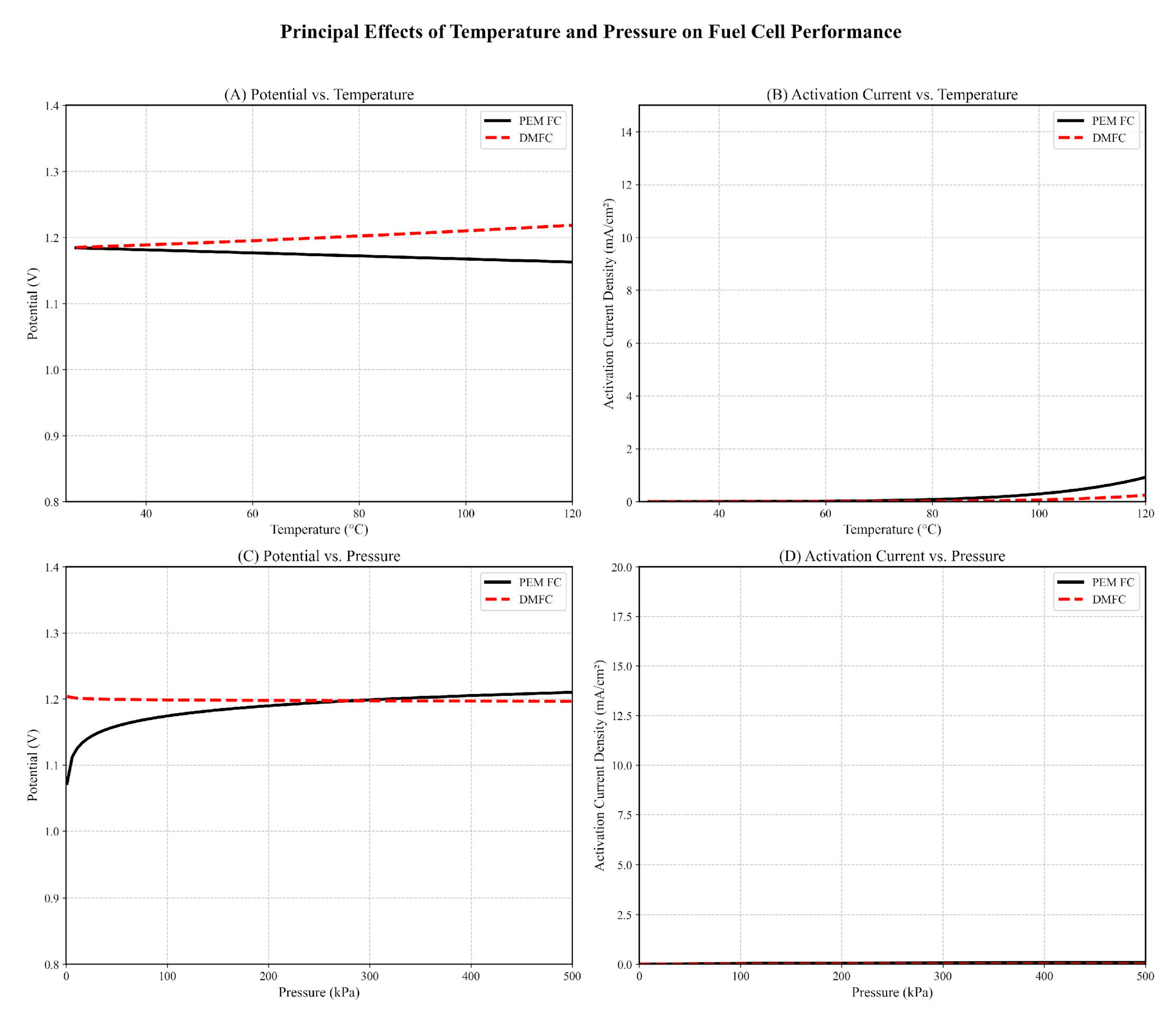

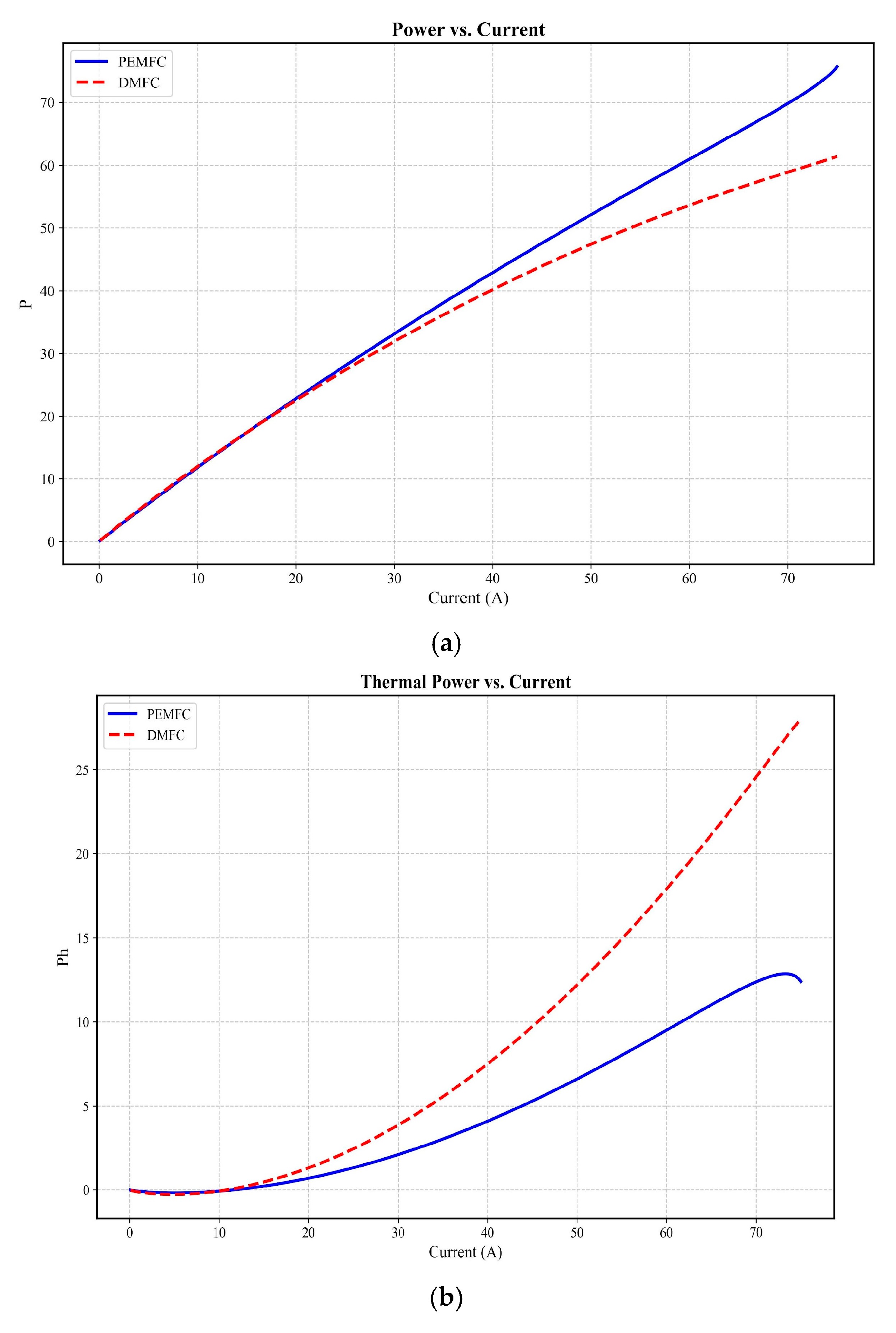

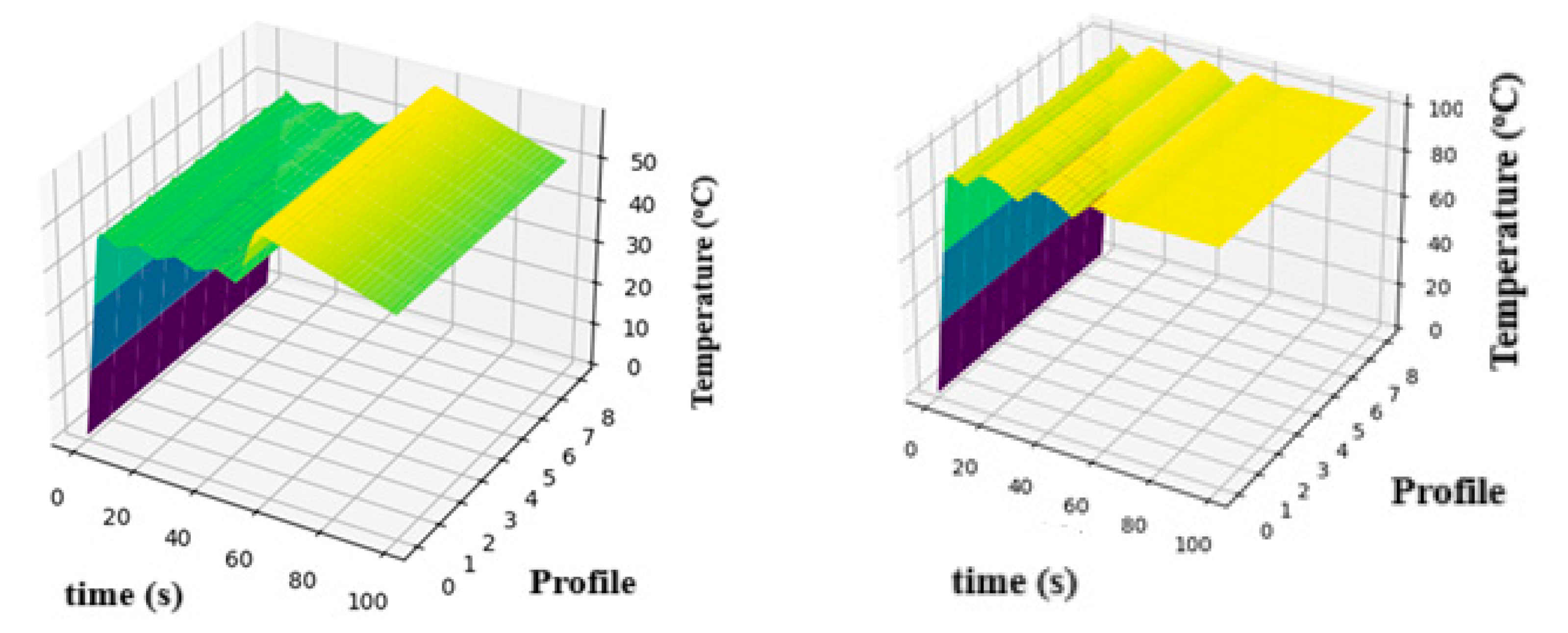

3.1. Thermodynamic and Electrochemical Behavior

Effects on the Potential and Activation Current Density at the Cathode

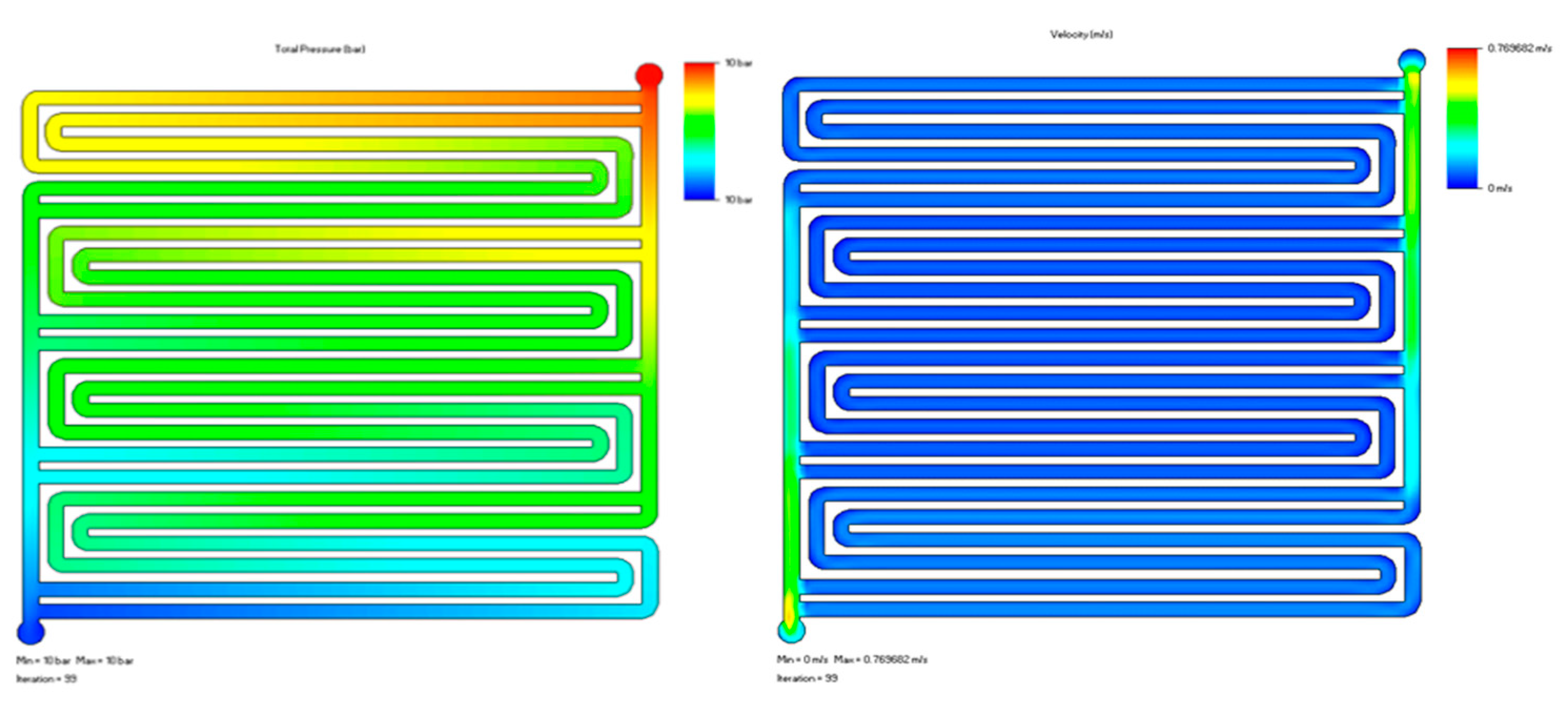

3.2. Fluid Dynamics Analysis

3.3. Discussion

| Parameter | This Work | Others Works |

|---|---|---|

| DMFC ΔH vs. PEMFC | 3× higher (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [48] | 2.8× (Santos et al., 2023) [81] |

| ΔG vs. Temperature | ΔG ↓ 0.12 eV/20°C [51] | ΔG ↓ 0.15 eV/20°C [82] |

| Pressure Effects | 10 bar → 30% ↓ activation loss | 5 bar → 25% ↓ loss [83] |

| DMFC Power Density | 5% > PEMFC (Figure 4b) [62] | 4–7% > PEMFC [80] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, P.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Fuel Cell Hybrid Electric Vehicles: A Review of Topologies and Energy Management Strategies. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2022, 13, 172. [CrossRef]

- Daud, W.R.W.; Rosli, R.E.; Majlan, E.H.; Hamid, S.A.A.; Mohamed, R.; Husaini, T. PEM Fuel Cell System Control: A Review. Renewable Energy 2017, 113, 620–638. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ruiz Diaz, D.F.; Chen, K.S.; Wang, Z.; Adroher, X.C. Materials, Technological Status, and Fundamentals of PEM Fuel Cells – A Review. Materials Today 2020, 32, 178–203. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, V.L.; Chung, C.K. Renewable Energy for SDG-7 and Sustainable Electrical Production, Integration, Industrial Application, and Globalization: Review. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2023, 15, 100657. [CrossRef]

- Sharafi Laleh, S.; Zeinali, M.; Mahmoudi, S.M.S.; Soltani, S.; Rosen, M.A. Biomass Co-Fired Combined Cycle with Hydrogen Production via Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis and Waste Heat Recovery: Thermodynamic Assessment. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 33795–33809. [CrossRef]

- Jayaprabakar, J.; Sri Hari, N.S.; Badreenath, M.; Anish, M.; Joy, N.; Prabhu, A.; Rajasimman, M.; Kumar, J.A. Nano Materials for Green Hydrogen Production: Technical Insights on Nano Material Selection, Properties, Production Routes and Commercial Applications. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 129455. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jia, C.; Bai, F.; Wang, W.; An, S.; Zhao, K.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, H. A Comprehensive Review of the Promising Clean Energy Carrier: Hydrogen Production, Transportation, Storage, and Utilization (HPTSU) Technologies. Fuel 2024, 355, 129455. [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Tang, T.-Q.; Gao, Y.; You, F.; Zhang, J. Calculation and Analysis of New Taxiing Methods on Aircraft Fuel Consumption and Pollutant Emissions. Energy 2023, 277, 127618. [CrossRef]

- Breitner-Busch, S.; Mücke, H.G.; Schneider, A.; Hertig, E. Impact of Climate Change on Non-Communicable Diseases Due to Increased Ambient Air Pollution. Journal of Health Monitoring 2023, 8 (Suppl 4), 103–121. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yang, J.; Xia, C. A Prompt Decarbonization Pathway for Shipping: Green Hydrogen, Ammonia, and Methanol Production and Utilization in Marine Engines. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 584. [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Amir, M.; Lakshmi, G.S.; Harivardhagini, S.; Ahmad, M. Fuel Cell-Based Hybrid Electric Vehicles: An Integrated Review of Current Status, Key Challenges, Recommended Policies, and Future Prospects. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 2023, 2, 100121. [CrossRef]

- Dall’Armi, C.; Pivetta, D.; Taccani, R. Hybrid PEM Fuel Cell Power Plants Fuelled by Hydrogen for Improving Sustainability in Shipping: State of the Art and Review on Active Projects. Energies 2023, 16, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Öner, E.T.; Yurtcan, A.B. Clean and Efficient Transportation with Hydrogen Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles. In Hydrogen Fuel Cell Technology for Mobile Applications; Felseghi, R., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 32–58. [CrossRef]

- Folkesson, A.; Andersson, C.; Alvfors, P.; Alaküla, M.; Overgaard, L. Real Life Testing of a Hybrid PEM Fuel Cell Bus. Journal of Power Sources 2003, 118, 349–357. [CrossRef]

- Dhanda, A.; Yadav, S.; Raj, R.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Zhang, T.C.; Duteanu, N.M. Fuel Cells and Biofuel Cells. In Microbial Electrochemical Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 19–52. [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.H.; Kazmi, S.A.A.; Hassan, M.; Muhammed Ali, S.A.; Anwar, M. Analysis of Fuel Cell Integration with Hybrid Microgrid Systems for Clean Energy: A Comparative Review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 3021–3030. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhou, T.; Wang, B.; Qiao, J. Enhanced Proton Conductivity of Viscose-Based Membranes via Ionic Modification and Dyeing Processes for Fuel Cell Applications. Journal of Materiomics 2023, 9, 587–600. [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Sidra Bibi, S.; Ahmed, S.; Irshad, M.; Shakir Hussain, M.; Zeb, H.; Kashif Khan, M.; Kim, J. Recent Advances in Green Hydrogen Production, Storage and Commercial-Scale Use via Catalytic Ammonia Cracking. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 473, 145381. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, S.; Meng, X.; Li, J.; Gao, J. Energy-Saving Cathodic H₂ Production Enabled by Non-Oxygen Evolution Anodic Reactions: A Critical Review on Fundamental Principles and Applications. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 15748–15770. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M.G.; Macedo, J.L.; Linhares, J.J.; Ghesti, G.F. Nanoparticulated WO₃/NiWO₄ Using Microcrystalline Cellulose as a Template and Its Application as Auxiliary Co-Catalyst to Pt for Ethanol and Glycerol Electro-Oxidation to Produce Green Hydrogen. Preprints 2023, 2023111641. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Jia, Y.; Yao, X. Defects on Carbons for Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reduction. Chemical Society Reviews 2018, 47, 7628–7658. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zou, L.; Huang, Q.; Zou, Z.; Yang, H. Multidimensional Nanostructured Membrane Electrode Assemblies for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2019, 7, 9447–9477. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.-Z.; Shi, Z.; Song, C.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, N.; Girard, F. MEA—Membrane Electrode Assembly. In Encyclopedia of Electrochemical Power Sources; Cabeza, L.F.B.T.-E.O.E.S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 276–289. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, C.; Sun, F.; Fan, J.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Research Progress of Catalyst Layer and Interlayer Interface Structures in Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA) for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) System. ETransportation 2020, 5, 100075. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, M.; Gou, W.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.; Qu, Y.; Ma, Y. A Fundamental Viewpoint on the Hydrogen Spillover Phenomenon of Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 3502. [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Lv, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, A.; Wu, G. Current Progress of Pt and Pt-Based Electrocatalysts Used for Fuel Cells. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2020, 4, 15–30. [CrossRef]

- Sajid, A.; Pervaiz, E.; Ali, H.; Noor, T.; Baig, M.M. A Perspective on Development of Fuel Cell Materials: Electrodes and Electrolyte. International Journal of Energy Research 2022, 46, 6953–6988. [CrossRef]

- Speight, J.G. Chapter 3—Fuels for Fuel Cells. In Fuel Cell Technologies: Hydrogen and Methanol; Shekhawat, D.; Spivey, J.J.; Berry, D.A.T.-F.C.T.F.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 29–48. [CrossRef]

- Sivtsev, V.; Lapushkina, E.; Kovalev, I.; Guskov, R.; Popov, M.; Nemudry, A. Microtubular Solid Oxide Fuel Cells with a Two-Layer LSCF/BSCFM5 Cathode. Green Carbon 2023. [CrossRef]

- Omrani, R.; Seif Mohammadi, S.; Mafinejad, Y.; Paul, B.; Islam, R.; Shabani, B. PEMFC Purging at Low Operating Temperatures: An Experimental Approach. International Journal of Energy Research 2019, 43, 7496–7507. [CrossRef]

- Santiago, E.I.; Matos, B.R.; Fonseca, F.C.; Linardi, M. Performance of Nafion-TiO₂ Hybrids Produced by Sol-Gel Process as Electrolyte for PEMFC Operating at High Temperatures. ECS Transactions 2007, 11, 151. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ruiz Diaz, D.F.; Chen, K.S.; Wang, Z.; Adroher, X.C. Materials, Technological Status, and Fundamentals of PEM Fuel Cells – A Review. Materials Today 2020, 32, 178–203. [CrossRef]

- Mosa, J.; del Rio, C.; Morales, E.; Raso, M.A.; Leo, T.J.; Maellas, J.; Aparicio, M.; Moreno, B.; Chinarro, E. New Direct Alcohol and Hydrogen Fuel Cells for Naval and Aeronautical Applications (PILCONAER). ECS Meeting Abstracts 2015, MA2015-03, 646. [CrossRef]

- Novaes, Y.R.d.; Zapelini, R.R.; Barbi, I. Design Considerations of a Long-Term Single-Phase Uninterruptible Power Supply Based on Fuel Cells. 2005 IEEE 36th Power Electronics Specialists Conference 2005, 1628–1634. [CrossRef]

- Sammes, N. Fuel Cell Technology: Reaching Towards Commercialization; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006.

- Notter, D.A.; Kouravelou, K.; Karachalios, T.; Daletou, M.K.; Haberland, N.T. Life Cycle Assessment of PEM FC Applications: Electric Mobility and μ-CHP. Energy & Environmental Science 2015, 8, 1969–1985. [CrossRef]

- Thounthong, P.; Raël, S.; Davat, B. Energy Management of Fuel Cell/Battery/Supercapacitor Hybrid Power Source for Vehicle Applications. Journal of Power Sources 2009, 193, 376–385. [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; Ghosh, P.C. A Generic Sizing Methodology for Thermal Management System in Fuel Cell Vehicles Using Pinch Analysis. Energy Conversion and Management 2022, 269, 116172. [CrossRef]

- Sery, J.; Leduc, P. Fuel Cell Behavior and Energy Balance on Board a Hyundai Nexo. International Journal of Engine Research 2021, 23, 709–720. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Kojima, K. Toyota MIRAI Fuel Cell Vehicle and Progress Toward a Future Hydrogen Society. The Electrochemical Society Interface 2015, 24, 45. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, Z.; Nader, W.B. PEM Fuel Cell as an Auxiliary Power Unit for Range Extended Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Energy 2022, 239, 121933. [CrossRef]

- Jonuskaite, A. Flow Simulation with SolidWorks; ReferenceWork Entry: Springer, 2017.

- Bernhard, D.; Kadyk, T.; Kirsch, S.; Scholz, H.; Krewer, U. Model-Assisted Analysis and Prediction of Activity Degradation in PEM-Fuel Cell Cathodes. Journal of Power Sources 2023, 562, 232771. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Ham, S.; Sohn, Y.-J.; Choi, Y.-Y.; Kim, M. Mass Transfer Characteristics According to Flow Field and Gas Diffusion Layer of a PEMFC Metallic Bipolar Plate for Stationary Applications. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 304–317. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Peng, S.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Deng, C.; Du, W.; Xie, N. Energetic and Exergetic Analysis of a Biomass-Fueled CCHP System Integrated with Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 13603–13616. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Bai, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, N. Multiphase Flow in PEM Water Electrolyzers: A Mini-Review. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering 2024, 43, 100988. [CrossRef]

- Kulikovsky, A. Laminar Flow in a PEM Fuel Cell Cathode Channel. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2023, 170, 024510. [CrossRef]

- Batool, M.; Godoy, A.O.; Birnbach, M.; Dekel, D.R.; Jankovic, J. Evaluation of Semi-Automatic Compositional and Microstructural Analysis of Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) Maps via a Python-Based Image and Data Processing Framework for Fuel Cell Applications. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2023, 170, 054511. [CrossRef]

- Carrette, L.; Friedrich, K.A.; Stimming, U. Fuel Cells: Principles, Types, Fuels, and Applications. ChemPhysChem 2000, 1, 162–193. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, R.; Baumann, N.; Jurzinsky, T.; Cremers, C. PEM-Fuel Cell Catalyst Behavior Between Room Temperature and Freezing Point. Fuel Cells 2020, 20, 236–244. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, W.; Nehter, P. Thermodynamics of Fuel Cells. In Modeling Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: Methods, Procedures and Techniques; Bove, R.; Ubertini, S., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 13–50. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.E.; McDaniel, A.H.; Allendorf, M.D. Considerations in the Design of Materials for Solar-Driven Fuel Production Using Metal-Oxide Thermochemical Cycles. Advanced Energy Materials 2014, 4, 1300469. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Pang, B.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Ding, Y.; O’Hayre, R.; Zhu, X.; Yang, W. Mapping a Thermodynamic Stability Window to Prevent Detrimental Reactions During CO₂ Electrolysis in Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2023, 324, 122239. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.V. Chapter 2 - Thermodynamics and Energy Engineering. In Thermochemical Conversion of Biomass for Liquid Fuels; Sharifzadeh, M.B.T.-D.A.O.S.O.F.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 43–84. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.C.; Ren, X.; Gottesfeld, S.; Zelenay, P. Direct Methanol Fuel Cells: Progress in Cell Performance and Cathode Research. Electrochimica Acta 2002, 47, 3741–3748. [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, A.; Barragán, V.M. A Review of the State-of-the-Art of the Methanol Crossover in Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. Journal of Power Sources 1999, 84, 70–74. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Pai, C.-T.; Viswanathan, K.; Chang, J.-S. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment and Economic Analysis of Methanol/Hydrogen Production Processes for Fuel Cell Vehicles. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 300, 126959. [CrossRef]

- Mahcene, H.; Moussa, H.B.; Bouguettaia, H.; Bechki, D.; Zeroual, M. Computational Modeling of the Transport and Electrochemical Phenomena in Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Energy Procedia 2011, 6, 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Bockris, J.O.; Azzam, A.M. The Kinetics of the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction at High Current Densities. Transactions of the Faraday Society 1952, 48, 145–160. [CrossRef]

- Morisette, D.T.; Cooper, J.A.; Melloch, M.R.; Dolny, G.M.; Shenoy, P.M.; Zafrani, M.; Gladish, J. Static and Dynamic Characterization of Large-Area High-Current-Density SiC Schottky Diodes. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices 2001, 48, 349–352. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.M.; Allwood, J.M. Theoretical Efficiency Limits for Energy Conversion Devices. Energy 2010, 35, 2059–2069. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Halseid, M.C.; Heinen, M.; Jusys, Z.; Behm, R.J. Ethanol Electrooxidation on a Carbon-Supported Pt Catalyst at Elevated Temperature and Pressure: A High-Temperature/High-Pressure DEMS Study. Journal of Power Sources 2009, 190, 2–13. [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.H.; Lee, C.S. A Study on the Overall Efficiency of Direct Methanol Fuel Cell by Methanol Crossover Current. Applied Energy 2010, 87, 2597–2604. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Faghri, M. Vapor Feed Direct Methanol Fuel Cells with Passive Thermal-Fluids Management System. Journal of Power Sources 2007, 167, 378–390. [CrossRef]

- Macedo-Valencia, J.; Sierra, J.M.; Figueroa-Ramírez, S.J.; Díaz, S.E.; Meza, M. 3D CFD Modeling of a PEM Fuel Cell Stack. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 23425–23433. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, F.; Rowshanzamir, S.; Rezakazemi, M. CFD Simulation of PEM Fuel Cell Performance: Effect of Straight and Serpentine Flow Fields. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 2012, 55, 1540–1557. [CrossRef]

- Wilberforce, T.; El-Hassan, Z.; Khatib, F.N.; Al Makky, A.; Mooney, J.; Barouaji, A.; Carton, J.G.; Olabi, A.-G. Development of Bi-Polar Plate Design of PEM Fuel Cell Using CFD Techniques. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 25663–25685. [CrossRef]

- Corda, G.; Cucurachi, A.; Diana, M.; Fontanesi, S. A Methodology to Design the Flow Field of PEM Fuel Cells. SAE Technical Paper 2023, 2023-01-0495. [CrossRef]

- Machaj, K.; Kupecki, J.; Niemczyk, A.; Malecha, Z.; Brouwer, J.; Porwisiak, D. Numerical Analysis of the Relation Between the Porosity of the Fuel Electrode Support and Functional Layer, and Performance of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 12305–12316. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaie, M.; Esmaeilpour, M. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation of Transport Phenomena in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. In Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 353–393. [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, Q.; Rahbar, M.; Han, M.; Lin, H.; Xu, S.; Wang, X. Thermal Conductivity of Gas Diffusion Layers of PEM Fuel Cells: Anisotropy and Effects of Structures. International Journal of Thermophysics 2023, 44, 167. [CrossRef]

- Gadhewal, R.; Vinod Ananthula, V.; Suresh Patnaikuni, V. CFD Simulation of Hot Spot in PEM Fuel Cell with Diverging and Converging Flow Channels. Materials Today: Proceedings 2023, 72, 410–416. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W. DMFC Auxiliary Losses Analysis. Journal of Power Sources 2023, 580, 233415. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y. Nernst Equation Analysis of Electrochemical Systems. Electrochimica Acta 2023, 441, 141785. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Sharma, P. Methanol Kinetics in Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. ACS Catalysis 2023, 13, 3021–3030. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M. Oxygen Reduction Reaction in DMFCs: Mechanistic Insights. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2023, 170, 044502. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Park, J.; Kim, S. Crossover Modeling in Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 292, 117366. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. High-Temperature PEMFCs: Performance and Durability. Applied Energy 2023, 352, 121876. [CrossRef]

- Eikerling, M.; Kornyshev, A.A. Double-Layer Compression in Electrochemical Interfaces. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2023, 127, 10233–10245. [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M.I.; Tan, C.K.; Lim, T.C. DMFC Efficiency Enhancement: A Review of Advanced Materials. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 187, 113703. [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Silva, T.; Ferreira, J. DMFC Performance Under Variable Operating Conditions. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 12305–12316. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, J. Temperature Dependence of Gibbs Free Energy in Fuel Cells. Energy 2023, 283, 128467. [CrossRef]

- Taccani, R.; Zuliani, N. Advanced Materials for Fuel Cell Applications. Journal of Power Sources 2021, 514, 230562. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, H. Hybrid Membranes for High-Temperature PEMFCs. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 5983. [CrossRef]

- Albo, J.; Sáez, C.; Cañizares, P. CO₂ Recycling Technologies for Sustainable Fuel Production. Energy & Environmental Science 2023, 16, 1854–1882. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description | Value/Range |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Temperature | PEMFC & DMFC | 65–100°C |

| Operating Pressure | PEMFC & DMFC | 25–35 bar |

| Reference Pressure (P₀) | - | 1 bar |

| Faraday Constant (F) | - | 96,485 C/mol |

| Gas Constant (R) | - | 8.314 J/(mol·K) |

| Number of Electrons (n) | PEMFC | 2 |

| DMFC | 6 | |

| Current Density (J) | From Tafel equation | Calculated |

| Operating Temperature | PEMFC & DMFC | 65–100°C |

| Operating Pressure | PEMFC & DMFC | 25–35 bar |

| Reference Pressure (P₀) | - | 1 bar |

| Faraday Constant (F) | - | 96,485 C/mol |

| Gas Constant (R) | - | 8.314 J/(mol·K) |

| Number of Electrons (n) | PEMFC | 2 |

| DMFC | 6 | |

| Active Area (A_Active) | Based on current and J | Calculated |

| Simulation Tool | Geometry design | SolidWorks Flow Simulation |

| Meshing & Post-processing | Python with Matplotlib | |

| Faraday Constant (F) | - | 96,485 C/mol |

| Gas Constant (R) | - | 8.314 J/(mol·K) |

| Number of Electrons (n) | PEMFC | 2 |

| Gas Constant (R) | - | 8.314 J/(mol·K) |

| DMFC | 6 | |

| Active Area (A_Active) | Based on current and J | Calculated |

| Simulation Tool | Geometry design | SolidWorks Flow Simulation |

| Meshing & Post-processing | Python with Matplotlib |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).