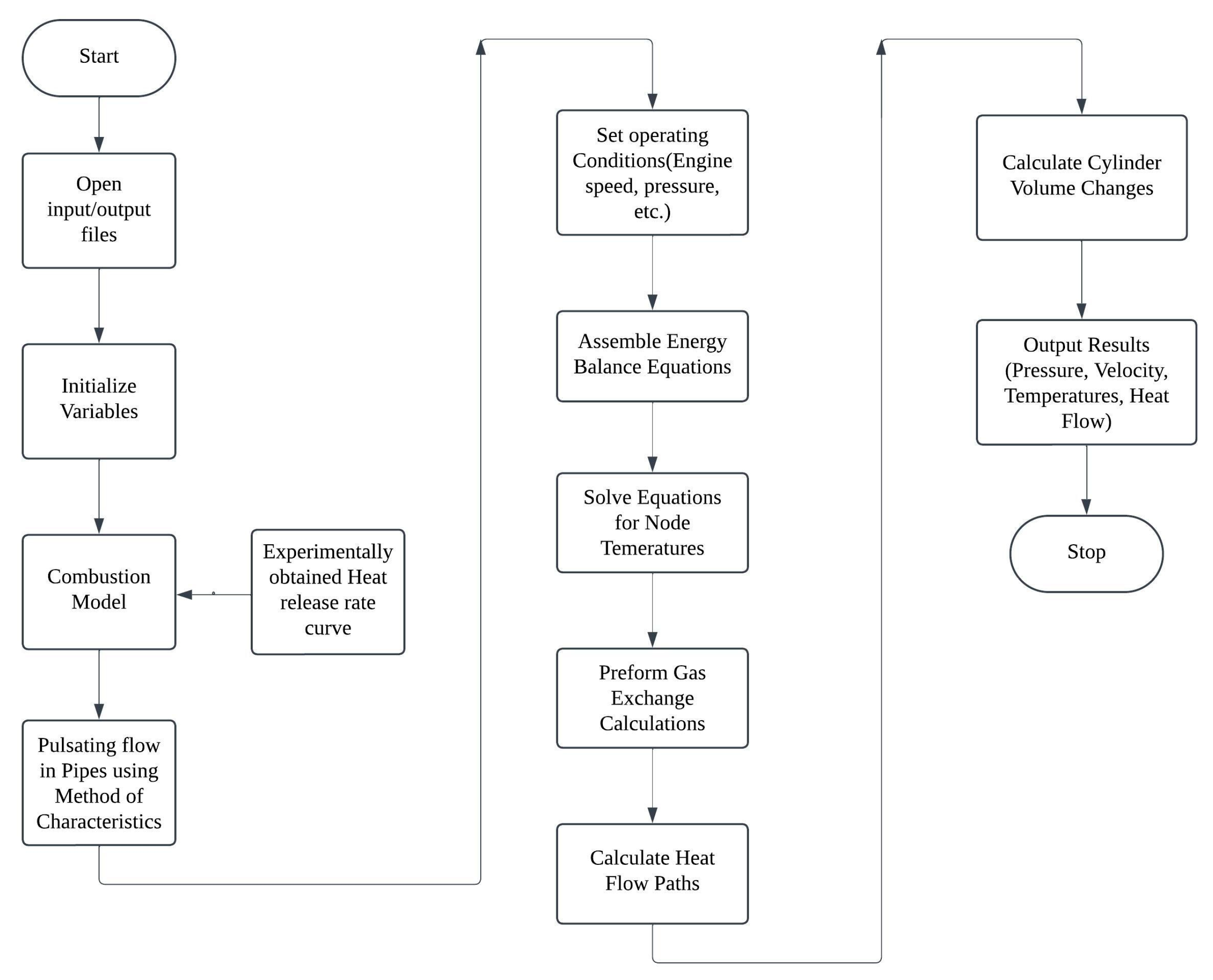

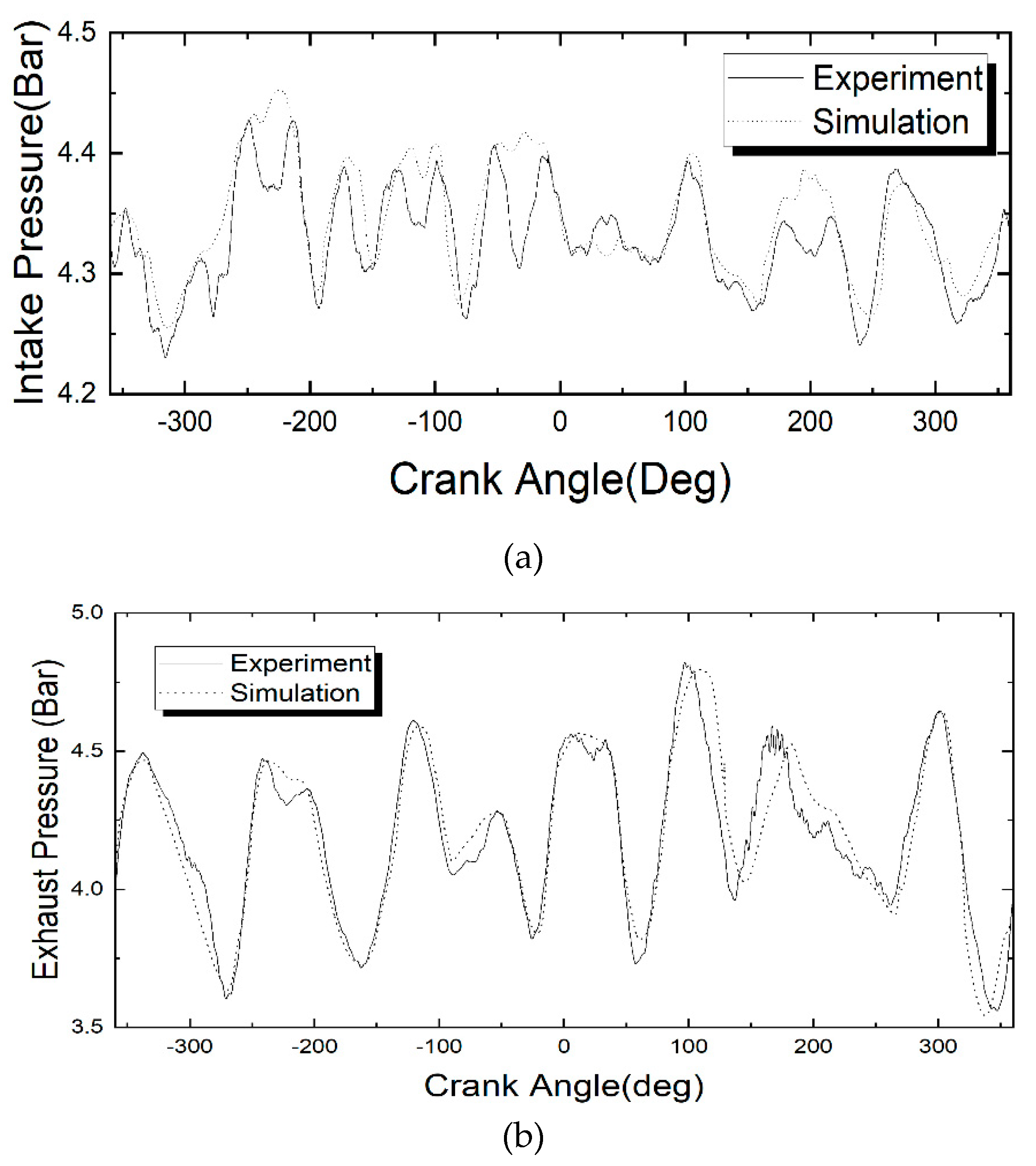

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4.1. Calibration of Combustion Model

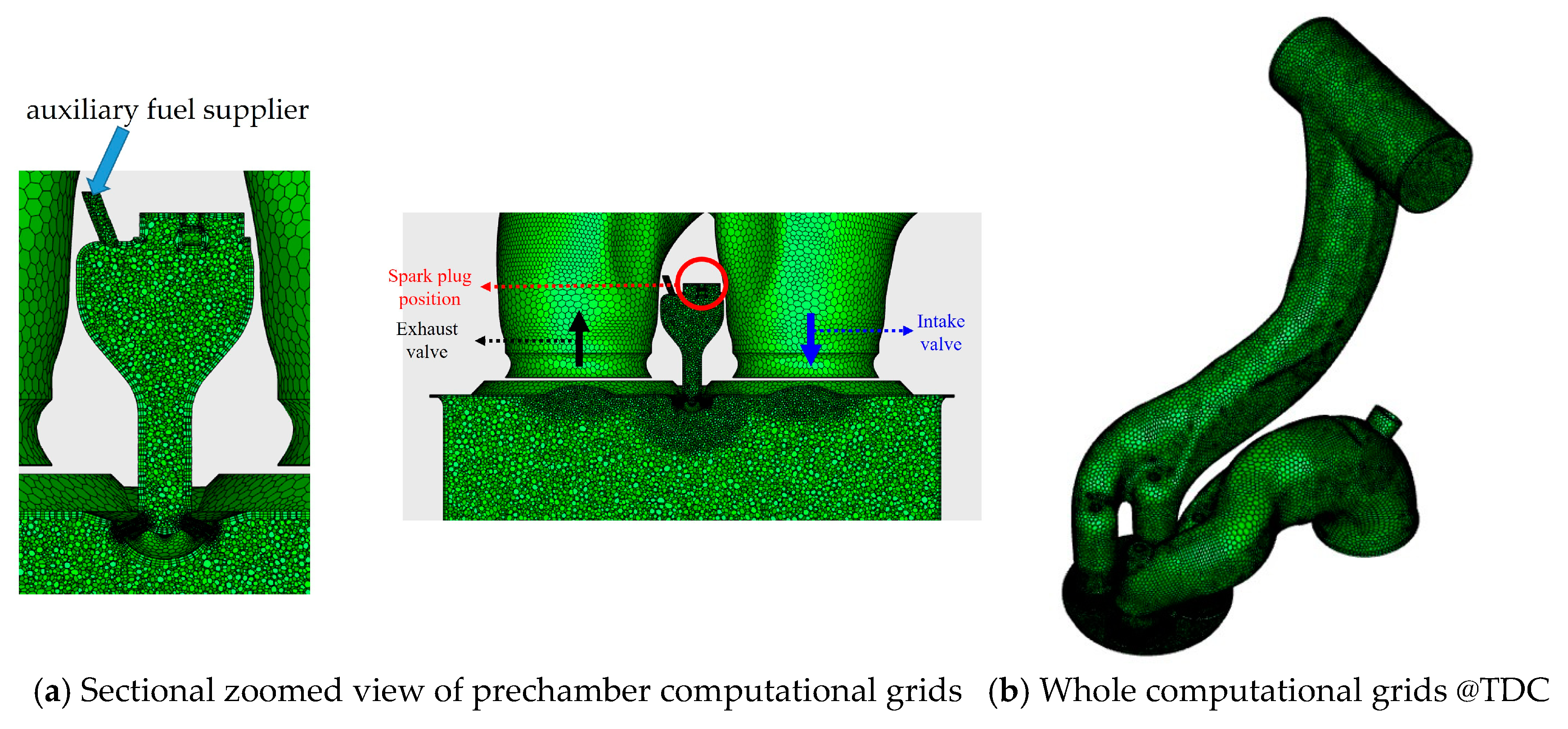

As previously mentioned, ECFM-3Z is a combustion model adopted in this study to simulate complex combustion processes in internal combustion engines. A critical parameter in this model is the stretch factor, presented in Equation (2), which plays a significant role in accurately predicting flame behavior under various operating conditions.

Several previous studies have attempted to optimize this parameter to overcome the limitations of flamelet-based models [

27,

39]. However, no research has been reported on its application to active-type natural gas fueled pre-chamber combustion systems. Therefore, this study aims to tune the ECFM-3Z model by systematically varying the stretch factor across a wide range. Specifically, the stretch factor was adjusted from 0.3 to 0.77, and an empirical correlation proposed in recent studies [

14,

52], as given in Equation (4), was applied. This correlation expresses the stretch factor in ECFM-3Z as a function of the flame-based Karlovitz number, based on the principle that the stretch factor modulates the interaction between turbulence and the flame front, influencing flame propagation speed and stability.

where,

,

The flame-based Karlovitz number included in Equation (5) is calculated using the following equation.

where, δ

L represents laminar flame thickness, S

L is laminar flame speed, ν denotes kinematic viscosity and ε is turbulent dissipation rate.

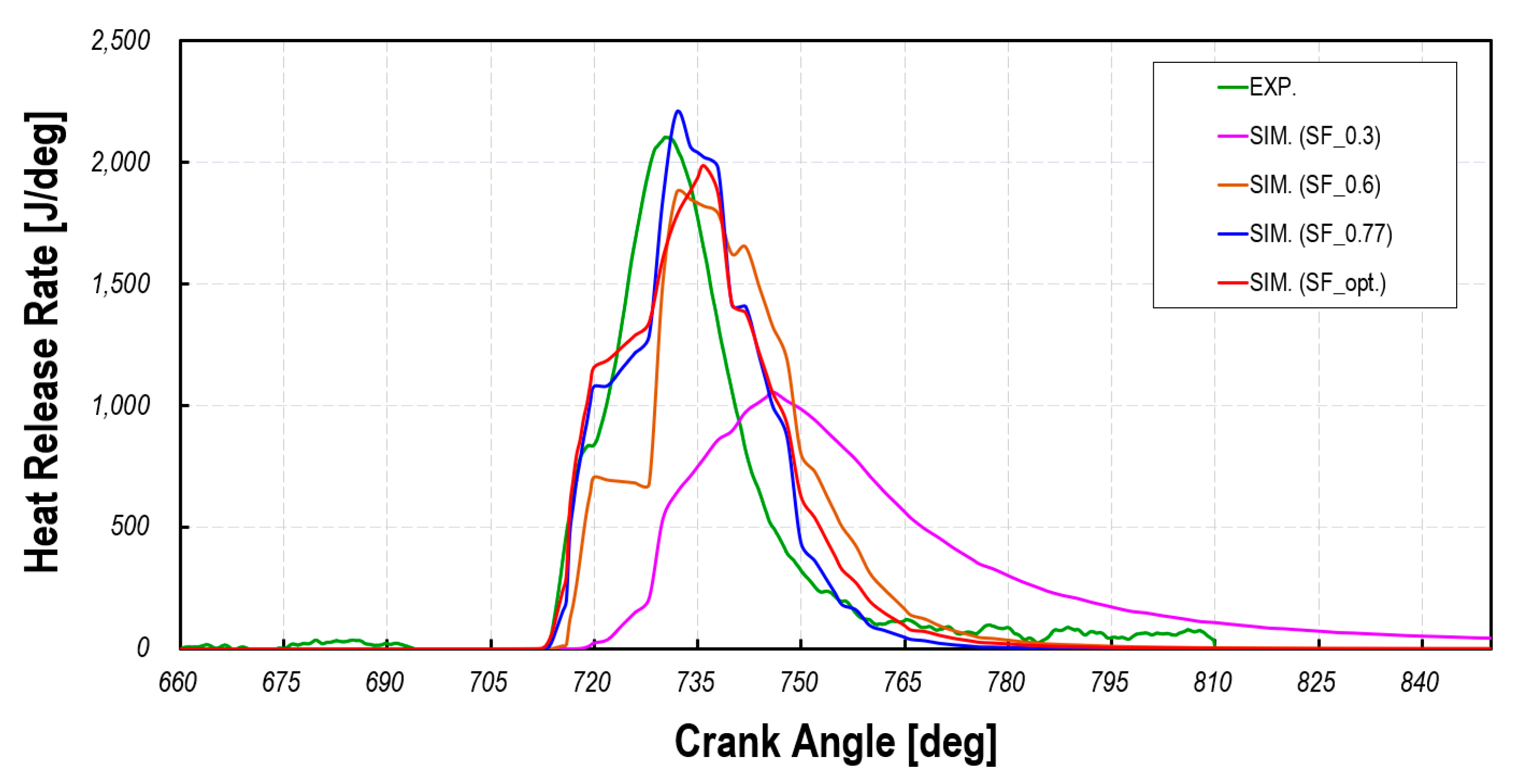

Figure 11 presents the heat release rate as a function of crank angle degrees for various stretch factor(

α) values, comparing the simulation results with those derived from experimentally measured in-cylinder pressure data of case 3. In

Figure 8, SF represents the stretch factor, while SF_opt denotes the stretch factor calculated using Equation (4).

Figure 8 presents the heat release rate as a function of crank angle degrees for various

α values, comparing the simulation results with those derived from experimental in-cylinder pressure measurements for Case 3. The experimental data in this figure represents the apparent heat release rate. The results indicate that as

α increases, both the heat release rate and its rate of change increase, demonstrating that higher

α values correspond to an increase in combustion speed. Another noteworthy feature of the results in

Figure 8 is that, despite extensive model tuning, the observed delayed combustion phasing indicates significant inaccuracies in the current turbulence-flame interaction model, which fails to accurately represent the anisotropic characteristics of turbulent flames in PCSI engines. In PCSI combustion, the formation of strong turbulent jets leads to the rapid dissipation of turbulent kinetic energy (TKE), posing a major challenge in modeling turbulence-flame interactions. Consequently, the flame does not have sufficient time to adjust to the turbulent flow field, resulting in numerical predictions that deviate from actual combustion behavior.

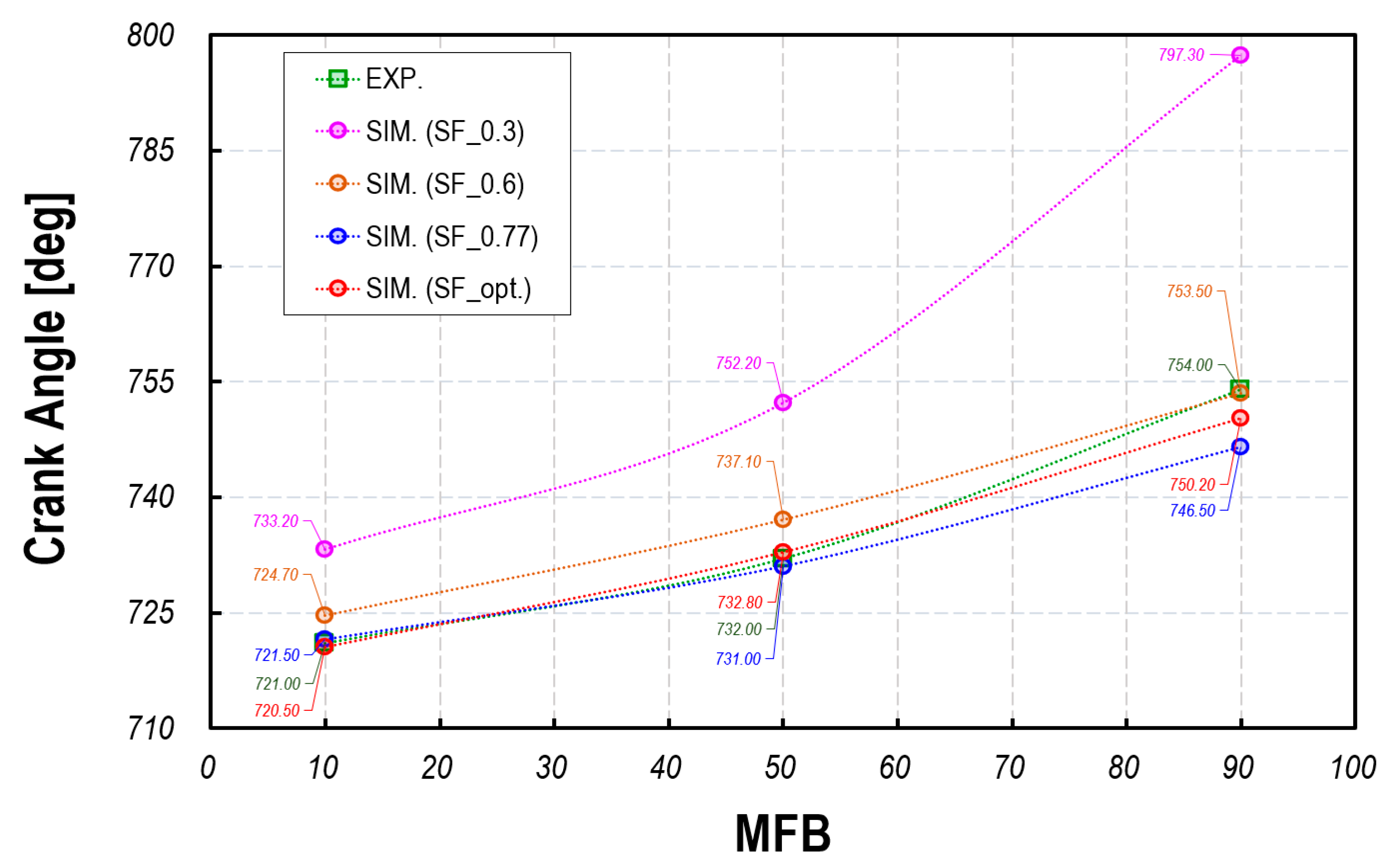

Figure 9 illustrates the effect of stretch factor variations on combustion speed by dividing the combustion duration into three phases: 10% mass fuel burn duration (MFB10), 50% mass fuel burn duration (MFB50), and 90% mass fuel burn duration (MFB90). As observed in the figure, higher α values correspond to faster combustion rates, leading to a reduction in burn duration. Additionally, in the SF_opt case, where the flame-based Karlovitz number is considered based on PCSI engine multi-mode combustion, a high prediction accuracy is achieved for the flame development angle (MFB10) to MFB50 region. These results indicate that tuning the stretch factor using Equation (4) provides the highest prediction accuracy, while using a single stretch factor shows that the optimal range is 0.6 < α < 0.77. This range deviates from the previously proposed optimal value (α = 0.525 – 0.6) suggested in earlier studies [

39]. Thus, it is confirmed that the correction of the stretch factor in ECFM-3Z must be performed individually based on engine operating conditions, fuel type, and combustion strategy. Based on these results, all CFD simulations in this study were conducted using the stretch factor calculated from the correlation in Equation (4), which demonstrated the highest accuracy in combustion analysis.

4.2. Validation of CFD Simulation with Flamelet-Based Combustion Model

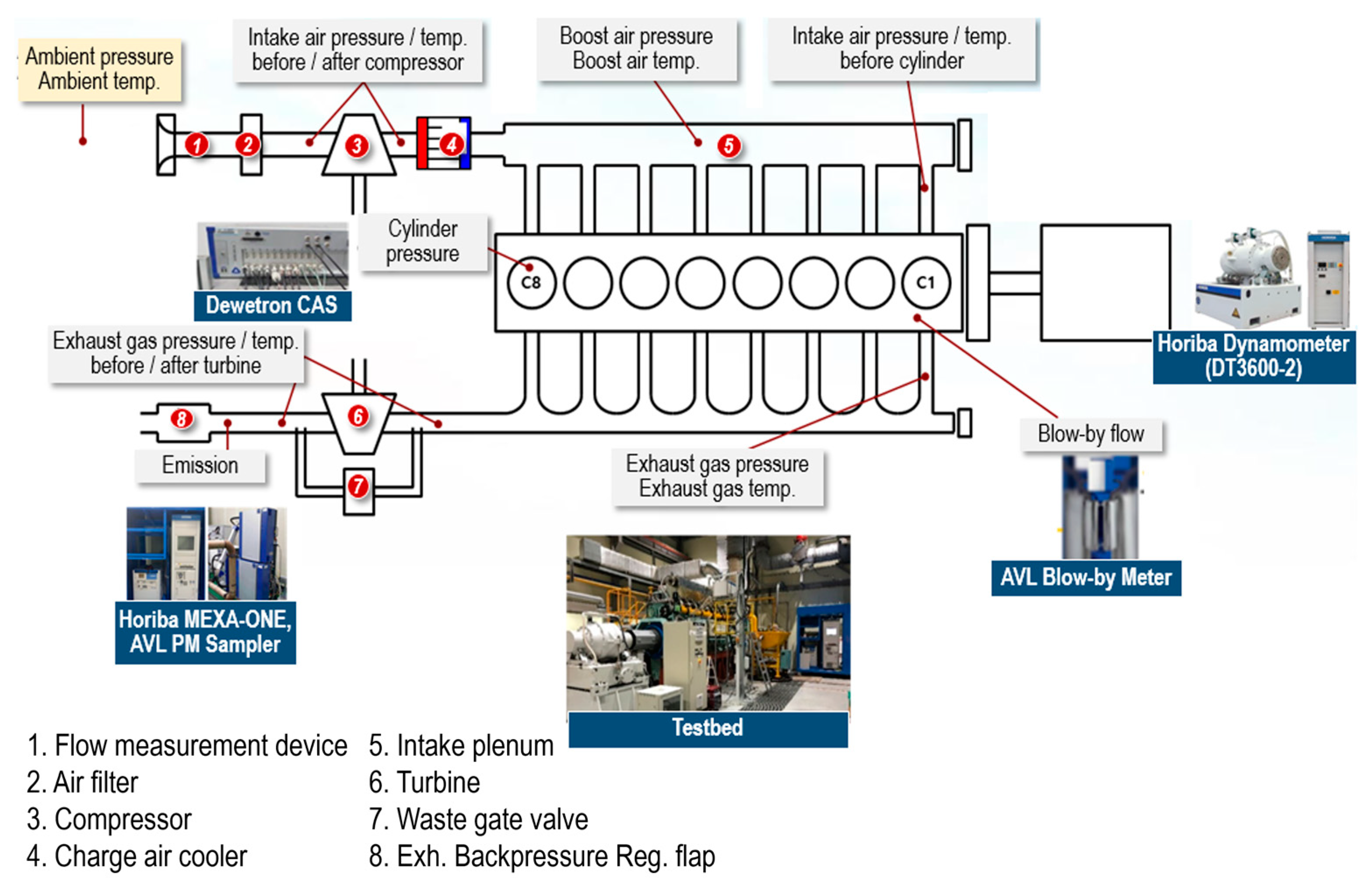

Before analyzing PCSI combustion engine using CFD, validating the CFD model is a crucial initial step to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the numerical solution. For this purpose, the operating point described in

Table 2 was selected. The in-cylinder pressure and emissions were compared with experimental measurements from the 8-cylinder engine, considering the pre-chamber configuration of Case 3. The validation test was conducted at an engine speed of 1000 rpm, under full-load, ultra-lean conditions (λ = 2).

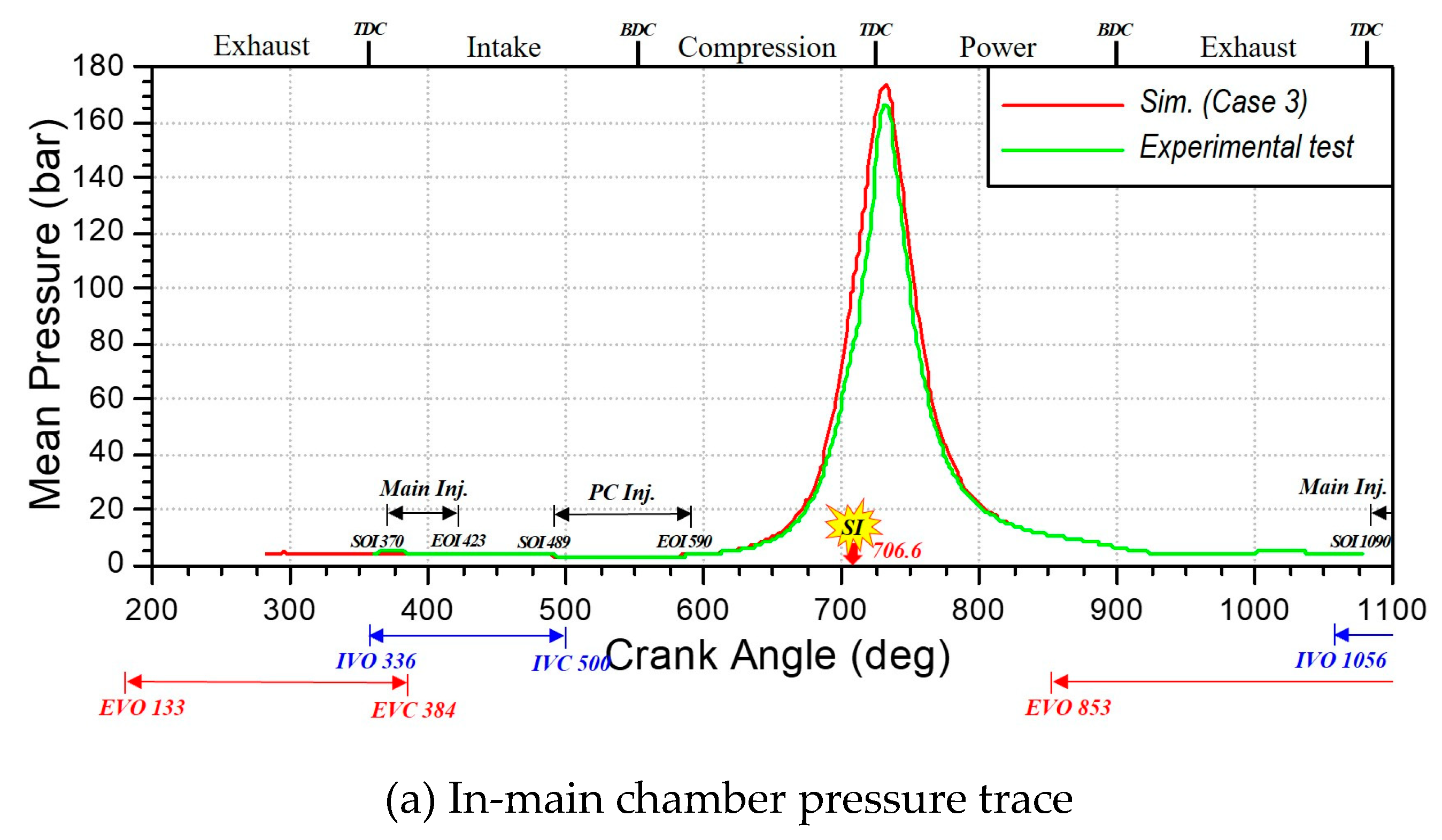

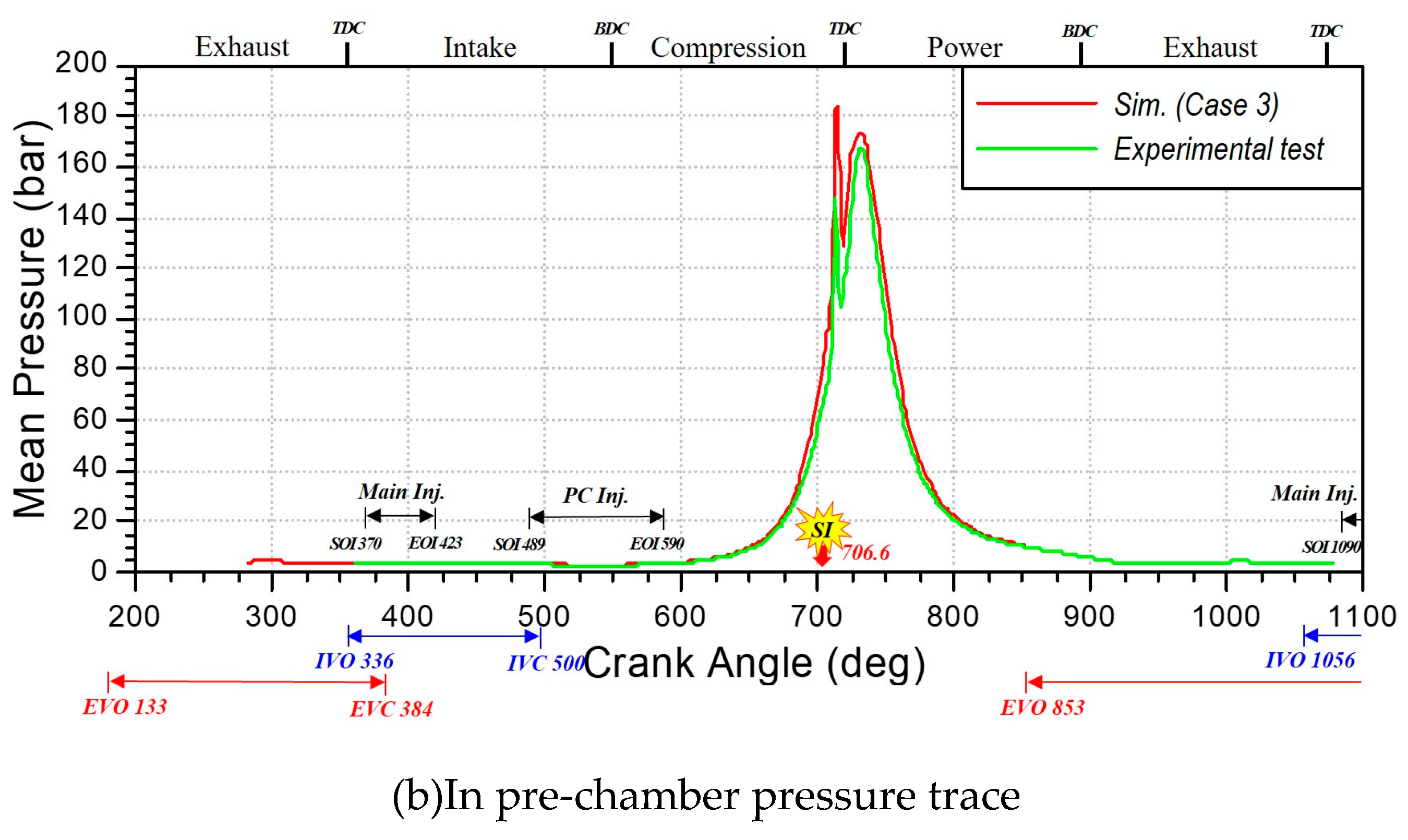

Figure 10 shows the comparisons between prediction and measurement for pressure trace of in-cylinder and pre-chamber at 1000rpm, full load. The experimental measurements encompass 300 cycles of pressure data with an associated average value, while the CFD simulation reports the average cylinder pressure computed from three cycles. It can be observed from

Figure 6 that the predicted pressures are reasonably good agreement with the experimental data. The close agreement between the in-cylinder pressure traces and the experimental data is attributed to the precise tuning of the stretch factor in the ECFM-3Z model, as previously discussed.

Further validations on the emissions of CO and NOx were indicated in

Figure 11. The CFD simulation results for CO emissions show an overprediction of approximately 11% compared to the experimental values. However, there exist large discrepancies of NO emission between the simulation and experiment. It can be found from

Figure 6 that the predicted NOx emissions are 24.7% larger than the meas-ured value. This is may be due to the problems that combustion sub-models may cause some numerical error resulting in overestimating pressure and temperature in pre-chamber. This is because in lean combustion conditions, using the Zel’dovich Mechanism for NOx prediction may lead to overestimation. This is primarily due to the inherent limitations of the mechanism and the characteristics of lean combustion. The Zel’dovich mechanism describes the formation of thermal NO, which predominantly occurs at high temperatures (>1800 K); however, in lean combustion, the combustion temperature decreases, limiting high-temperature regions, and consequently, actual NOx production may be lower than the predictions made by the Zel’dovich mechanism, which is highly sensitive to temperature and reaction rate constants, potentially leading to an overestimation of NOx formation at elevated temperatures. Additionally, the overestimation of NOx emissions can be attributed to the increased oxygen concentration. While a relatively high oxygen concentration is present, the low temperature and short residence time significantly suppress NOx formation. However, CFD models may not fully account for the effects of these ultra-lean conditions, potentially leading to an overestimation of NOx emissions. That is, in pre-chamber combustion, rapid flame propagation and high turbulence may reduce the residence time for thermal NOx formation, resulting in deviations from predicted values. The inability of the ECFM-3Z combustion model to accurately predict turbulence and mixing effects within the PCSI engine is another contributing factor to the overestimation. In pre-chamber engines, rapid mixing and flame jet dynamics can induce local temperature variations that are not fully captured by over-simplified models.

To improve the predictive accuracy of NOx emissions in PCSI engines using the Extended Zeldovich Mechanism, it is essential to incorporate the N₂O Pathway, a key NOx formation route under lean-burn conditions. Additionally, the temperature dependency of the mechanism should be modified to account for the sharp decline in thermal NOx reaction rates, and low-temperature NOx formation pathways, such as NO production from hydrocarbon radicals, must be introduced. Beyond refining the chemical mechanism, PCSI engine-specific effects should be integrated into NOx modeling by dynamically coupling local equivalence ratios and stratification, as computed from the ECFM-3Z model, with the Extended Zeldovich Mechanism.

Finally, accurately capturing turbulence effects on flame structure and reaction zones necessitates the development of numerical models that couple the Zeldovich mechanism with turbulence modeling, enabling better resolution of lean combustion conditions. Advancing such computational frameworks is critical for improving NOx emission predictions in PCSI engines.

For CO emissions, the ECFM-3Z model may overestimate CO levels under certain conditions due to its treatment of post-flame oxidation and turbulence-chemistry interactions. In active PCSI engines, a significant portion of CO undergoes oxidation after the main flame has passed, driven by the presence of residual radicals (∙OH, O∙, H∙) and bulk turbulence effects. Since ECFM-3Z assumes an equilibrium-driven post-flame oxidation model, it may underpredict CO oxidation rates, resulting in higher predicted CO emissions compared to experimental values. Another factor contributing to the overestimation of CO emissions is the inadequate representation of turbulent mixing between the pre-chamber and main chamber, which affects the accuracy of CO formation and oxidation predictions. High-momentum turbulent jets enhance CO oxidation through jet-induced mixing and flame propagation acceleration; however, ECFM-3Z may not fully capture turbulence-chemistry interactions in these regions, leading to an overprediction of CO concentrations in simulations.

Figure 11.

Experimental Validation of CO and NOx Emissions Derived from CFD Analysis.

Figure 11.

Experimental Validation of CO and NOx Emissions Derived from CFD Analysis.

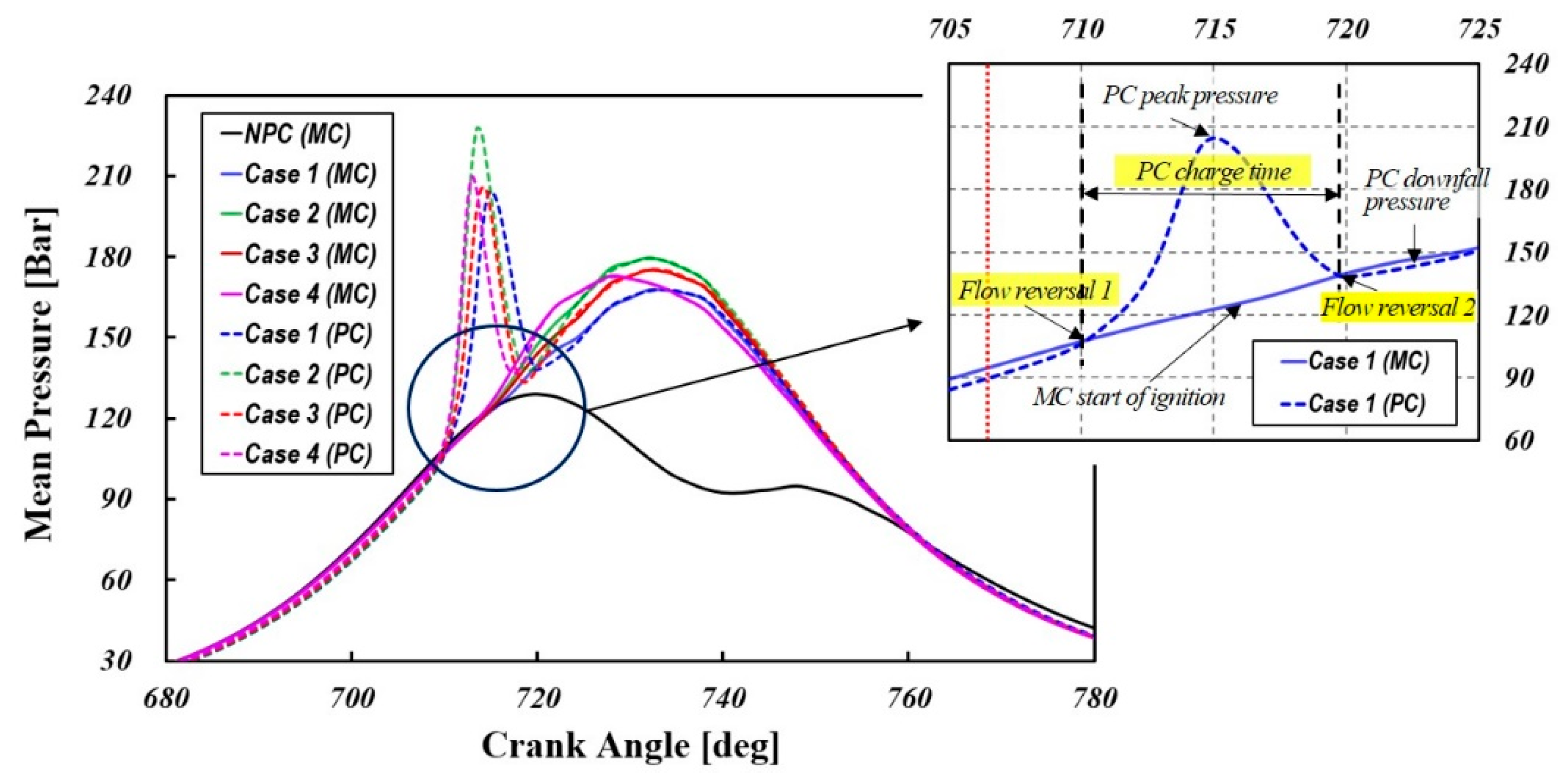

4.3. Exploring Thermo-Fluid Interaction Between the Prechamber and Main Chamber

Figure 12 displays pressure curves for the pre-chamber (PC) and main chamber (MC) across various configurations, including a reference case without a pre-chamber (NPC). The throat diameter greatly affects the PC peak pressure—a smaller throat retains the reacting mixture longer, leading to higher pressure. In cases with a pre-chamber, the PC curve shows dual peaks: the first from rapid combustion of a near-stoichiometric mixture in the PC, and the second from the MC pressure rise propagating into the PC. The zoomed section in the upper right of

Figure 12 (case 1) illustrates the interplay between the expanding flame pushing reactants out of the PC and the MC gases flowing in due to compression. When the PC pressure exceeds the MC pressure, flow reversal 1 (FR1) occurs; a later equilibrium marks flow reversal 2 (FR2).

Figure 8 clearly illustrates that variations in the orifice cone angle have a pronounced effect on the pre-chamber pressure. In this study, case 2—where the cone angle was increased by 10°—produced the highest peak pressure in the pre-chamber. This outcome is likely attributable to the significant flow resistance encountered by the combusted turbulent jets as they pass through the orifices.

Table 3 summarizes these events and the residence time—defined as the interval between FR1 and FR2 [

29]. Cases 1 and 2 have longer residence times due to higher flow restrictions, allowing prolonged radical dispersion but increasing the risk of chemical transformation. Shorter residence times indicate lower pre-chamber combustion and higher mass flow, resulting in jets richer in active species. Larger orifice diameters enable faster energy transfer to the MC, with a lower degree of pre-chamber combustion releasing more fuel energy in the MC for enhanced ignition. Case 4, which employed a diverging-tapered-hole nozzle, exhibited the shortest residence time. This is because, unlike conventional straight-hole nozzles, a diverging-tapered-hole nozzle minimizes flow separation at the nozzle exit, thereby increasing the gas jet velocity and enhancing the mixing with the air-fuel mixture in the main chamber. Previous studies [

16,

19,

53] emphasize that excessive flow restriction may lead to recombination of active species before they effectively mix with the MC charge. As shown in

Table 3, while the onset of FR1 due to combustion is nearly identical across configurations, the termination time of the discharge of high-pressure combustion products through the orifice (FR2) is strongly governed by the orifice’s geometric configuration.

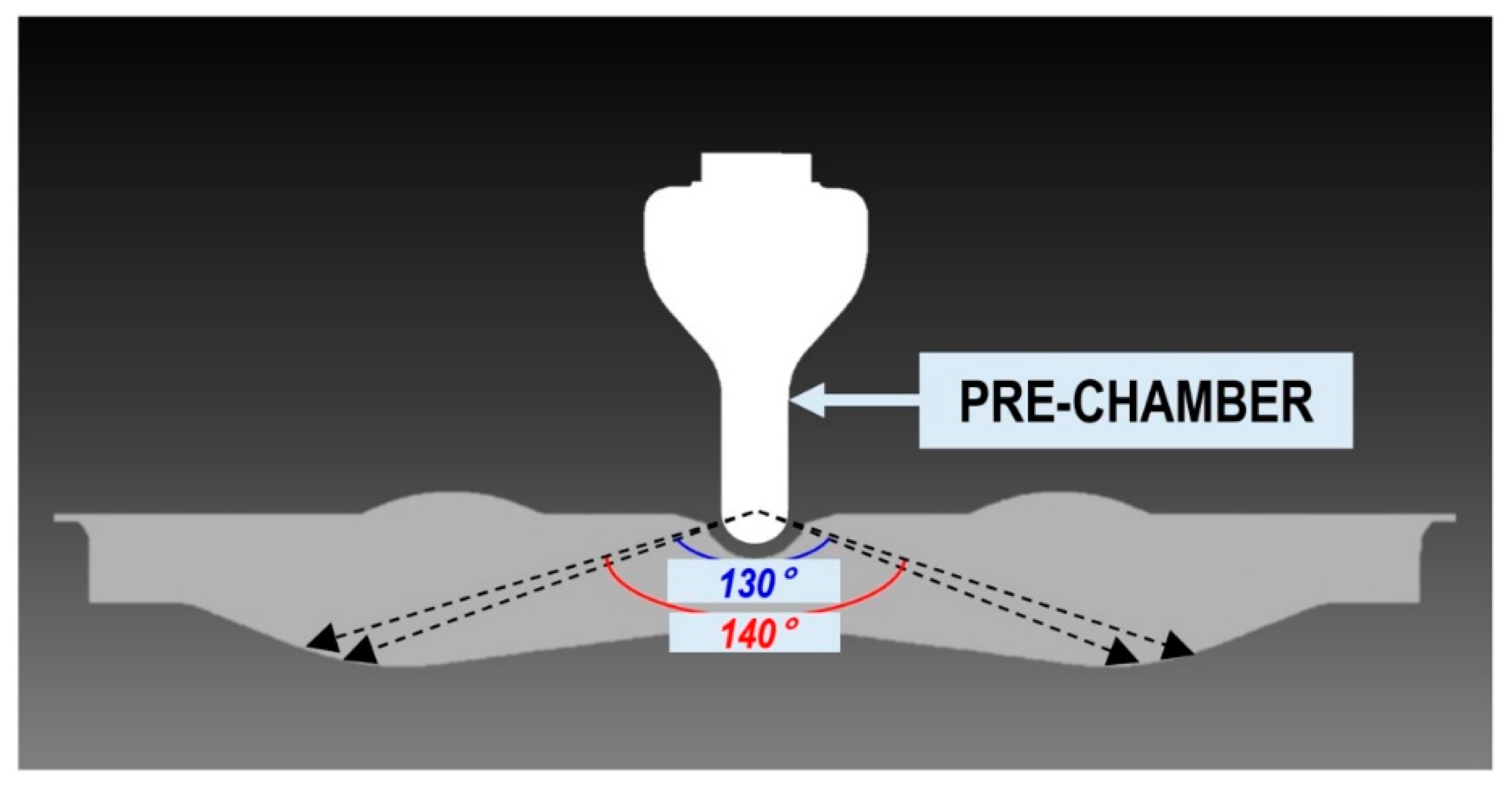

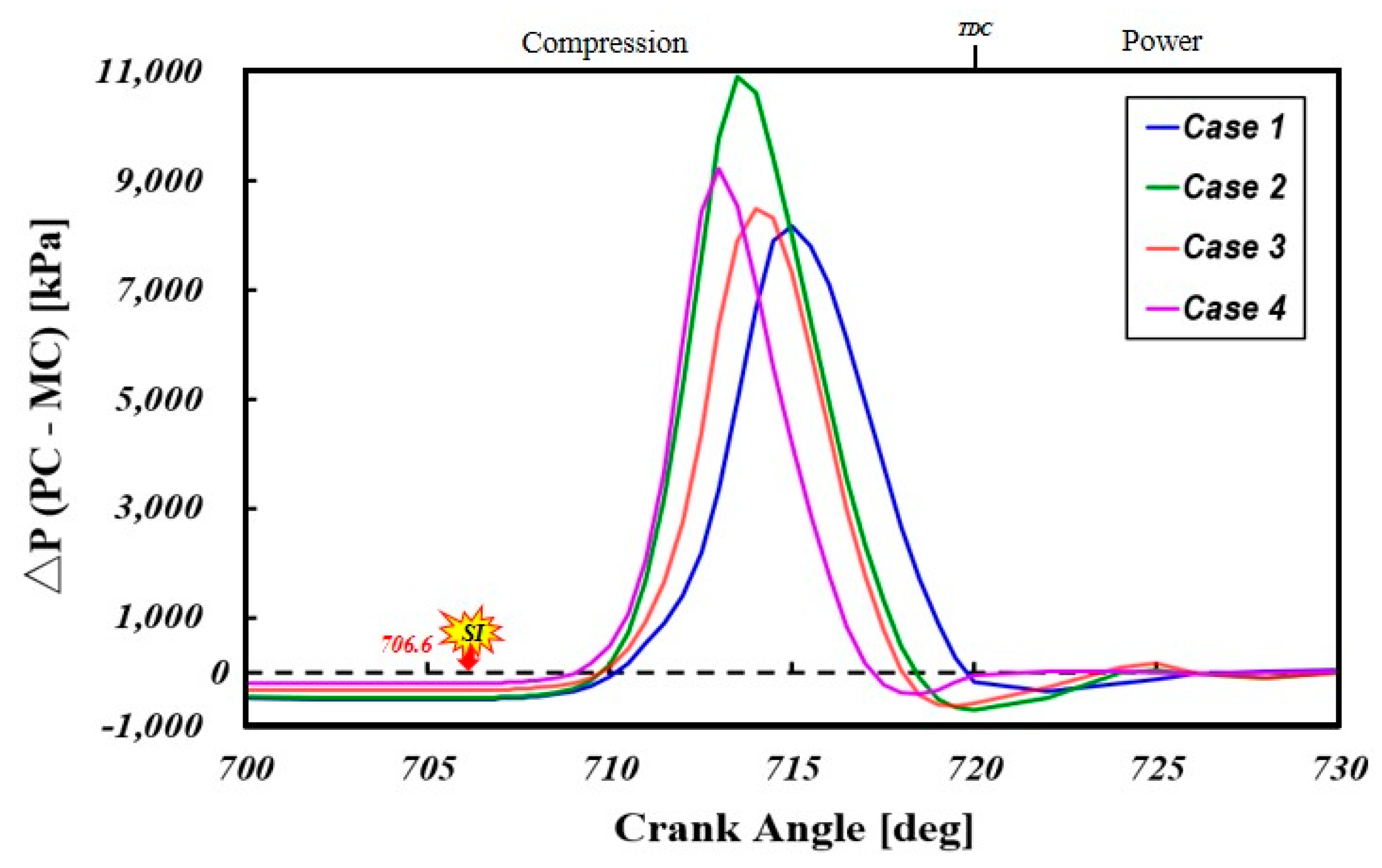

Figure 13 shows the pressure differential between the PC and MC for different configurations. The results indicate that the nozzle diameter and cone angle strongly influence the PC pressure. This differential acts as the driving force for jet flame injection into the MC. Case 2 exhibits the highest peak pressure differential, while Cases 1, 3, and 4 show reductions of 25%, 22%, and 15% compared to Case 2. The elevated differential in Case 2 is likely due to higher combustion pressure in the PC.

Figure 13 shows that while the onset of pressure rise in the PC is similar across different orifice geometries, the slope of the pressure rise curve varies significantly, resulting in distinct phase shifts among the cases. This variation is due to differences in the scavenging flow during compression, which affect the distribution of mixture concentration, flow velocity field, and turbulence intensity level near the spark plug. These factors influence flame propagation and speed. The peak PC pressure depends on the flow resistance encountered by the turbulent jet as it passes through the orifice. In this study, Case 2 exhibits the highest peak pressure and steepest gradient of initial rise, likely due to an optimal mixture concentration and turbulence at the ignition stage, promoting rapid flame development.

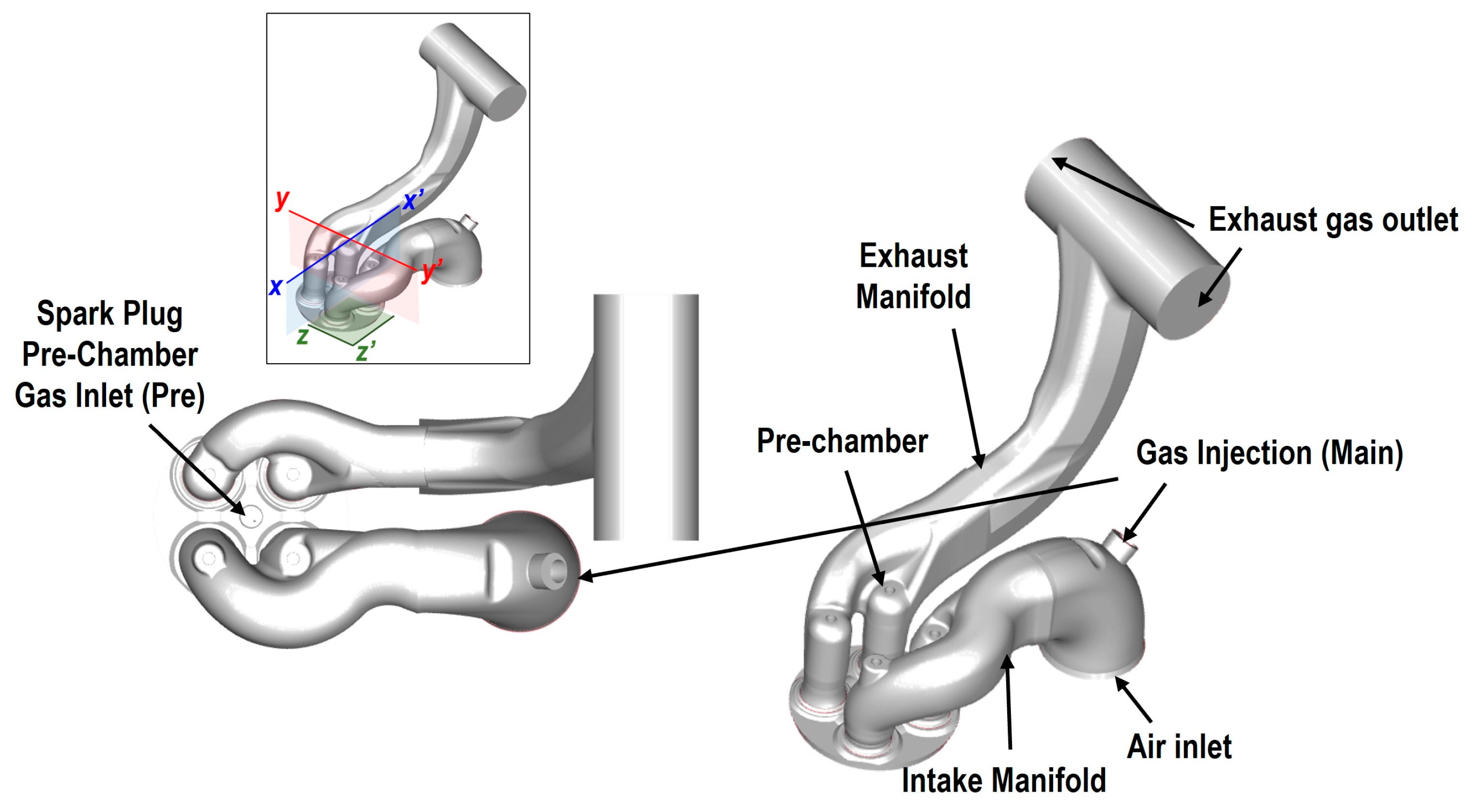

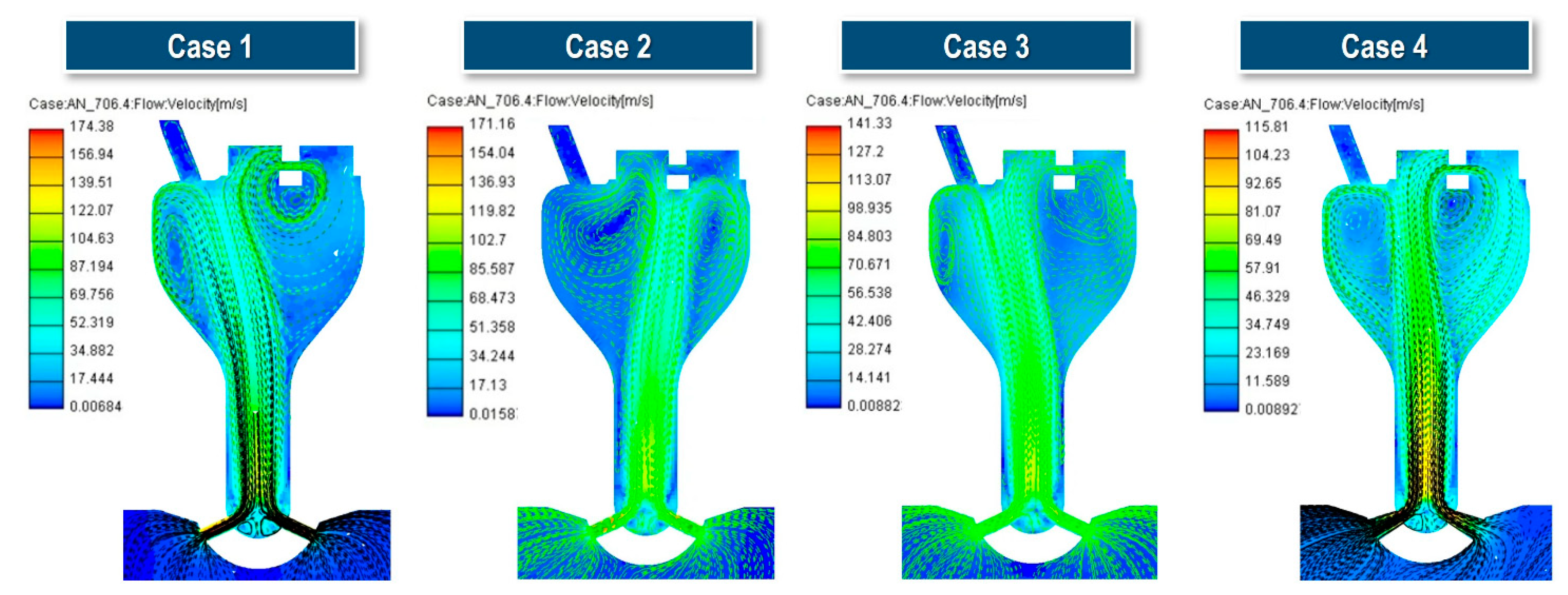

Figure 14 presents the velocity contours and flow streamlines in the pre-chamber for different cases at 706.4°CA, just before ignition. A key characteristic of the flow behavior during the compression stroke is the strong mixing of jets from each nozzle in the lower region of the pre-chamber. These mixed flows then ascend and, except for Case 2, are deflected to the left of the central axis before reaching the upper surface. The upward flow induces the formation of recirculating vortices on both the left and right sides, influencing the flow dynamics around the spark plug gap. As the upward-moving flow impacts the pre-chamber roof, it decelerates and subsequently passes through the spark plug gap. The most critical aspect of the pre-chamber flow field is the interaction and balance between the two recirculating vortices, which are primarily dictated by the nozzle jet flow rate and injection angle.

In the case of Case 4, which is equipped with a diverging-tapered nozzle, the nozzle functions as a converging-tapered-hole nozzle during the compression stroke. Consequently, the constriction in the channel induces a pressure drop, accelerating the flow and increasing the outlet velocity. This, in turn, enhances jet momentum and penetration, generating a strong, more directed upward flow toward the spark plug. As a result, a more symmetrical recirculation zone is established on both sides of the pre-chamber.

A key observation in this figure is that in Case 2, where the orifice cone angle is increased, the flow streams from the eight orifices merge in the lower region of the pre-chamber and, unlike other cases, shift rightward before ascending directly toward the spark plug. This leads to the formation of a strong and wide recirculation zone on the left side. Unlike other cases, where the right-side recirculation flow interacts with and passes through the spark plug gap, Case 2 exhibits a stagnated flow distribution. Ultimately, this result confirms that modifying the orifice cone angle has a more significant influence on the pre-chamber flow distribution at the time of ignition compared to simply altering the orifice geometry.

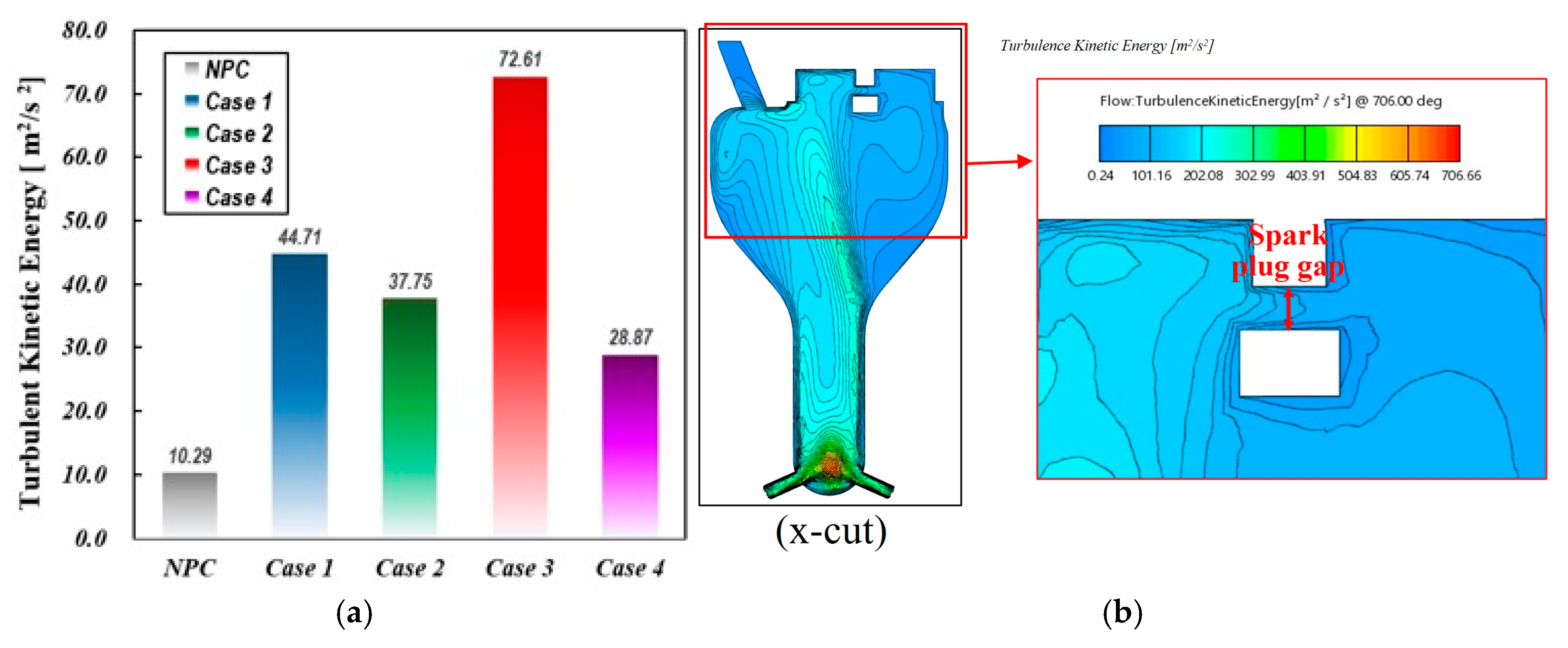

Figure 15(a) presents the turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) at the spark plug gap position just before ignition. Among the analyzed cases, Case 3 exhibits the highest TKE level, while Case 1 shows a 38.4% lower TKE than Case 3, Case 2 is 48.0% lower, and Case 4 is 60.2% lower. As shown in

Figure 11, the flow expelled from each nozzle mixes in the lower region of the pre-chamber. As this flow moves upstream, the turbulent kinetic energy dissipates and weakens.

Figure 15(b) illustrates the distribution of turbulent kinetic energy in the x-x' cross-section for Case 3, which exhibits the highest turbulence kinetic energy (TKE) level at the spark plug gap. In a PCSI engine, the turbulence intensity at the spark plug gap significantly impacts ignition stability, flame propagation, and combustion efficiency by influencing flame kernel formation, cycle-to-cycle variations, and emissions. Hence, maintaining high TKE at the spark plug gap through pre-chamber geometry optimization is crucial, as it enhances flame kernel development by increasing the initial flame stretch rate and reducing ignition delay [

14,

18,

19]. It can be observed that the formation of two recirculation zones on the left and right sides of the pre-chamber, where TKE levels are significantly low. A strong upwash flow with high turbulent kinetic energy develops between these two recirculation regions but weakens further as it moves toward the upper end of the pre-chamber. Eventually, this flow passes through the spark plug gap.

These findings indicate that to ensure an optimal distribution of turbulent energy at the spark plug gap for stable combustion, it is necessary to optimize the nozzle diameter and length, as well as the volume and shape of the pre-chamber.

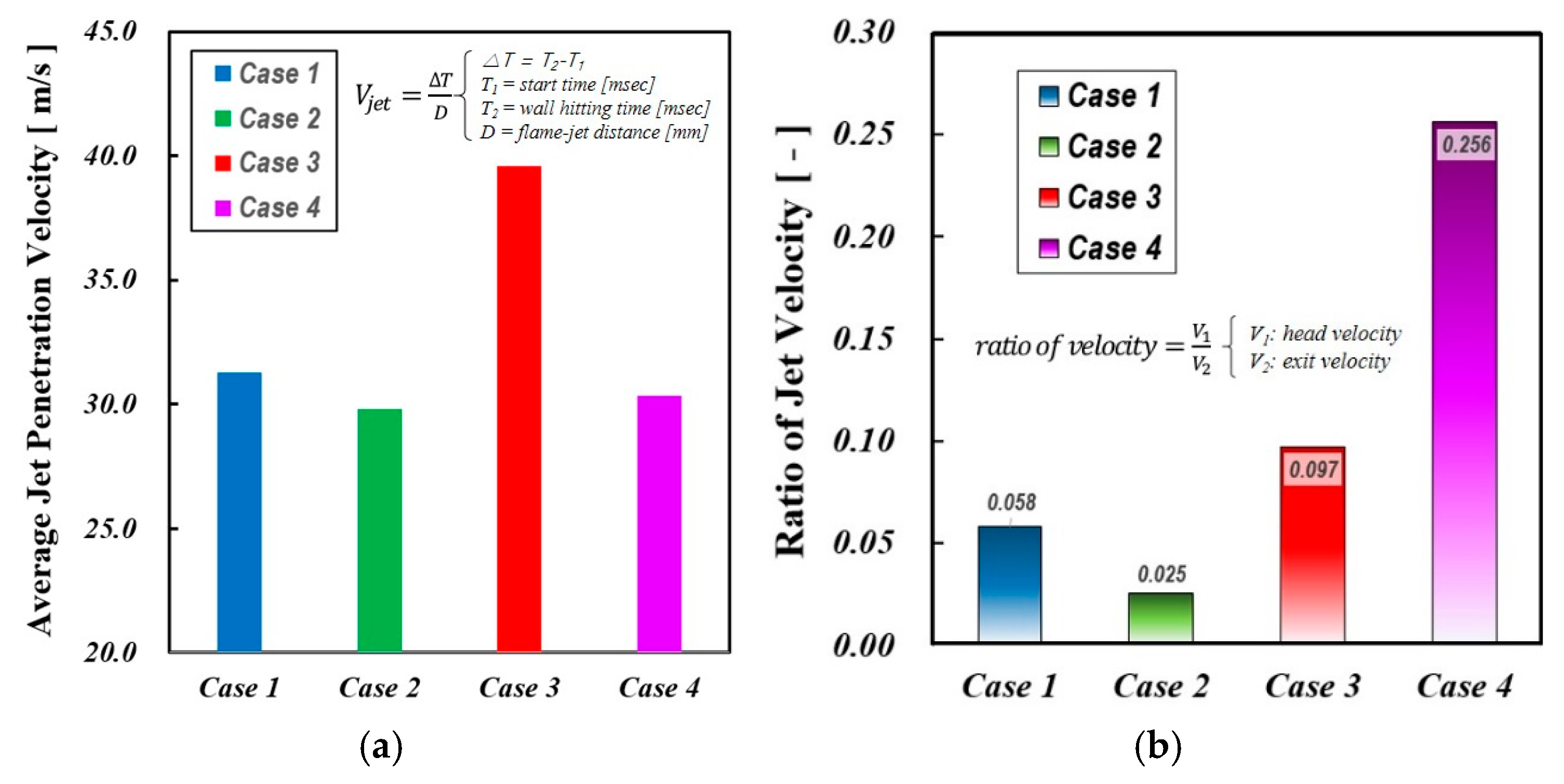

Figure 16(a) presents the average jet penetration velocity, determined by measuring the distance traveled by the jet from the start of ejection until it either reaches the combustion chamber wall or ceases further movement. Among the analyzed cases, Case 3 exhibits the highest penetration velocity, attributed to its greater absolute mass flow and, consequently, stronger pre-chamber ejection momentum. Regarding nozzle diameter effects, it is well established that jets from smaller nozzle diameters penetrate the combustion chamber more rapidly due to their higher velocity and momentum. However, Case 3, despite having a larger orifice diameter, maintains a thicker jet core, which enhances momentum retention over a longer distance. Additionally, a thicker jet plume improves entropy transfer to the main chamber, facilitating deeper penetration before jet dissipation occurs.

Figure 16(b) compares the instantaneous jet exit velocity at the nozzle with the instantaneous jet head velocity at FR2. The jet exit velocity is derived from simulations by averaging velocity magnitudes along the jet axis within the nozzle length. The figure indicates that at FR2, the jet head velocity decreases by approximately 2% to 26% relative to the jet exit velocity, reflecting the degree of deceleration. Among the examined cases, Case 4 demonstrates the highest jet speed ratio, signifying that the turbulent jet momentum is effectively sustained throughout the later stages of flame development. This is because the diverging-tapered-hole nozzle reduces pressure drop and boundary layer separation, thereby minimizing turbulence across the nozzle and producing stronger turbulent jets. This confirms that variations in jet head velocity are significantly influenced by pre-chamber nozzle geometry, as anticipated.

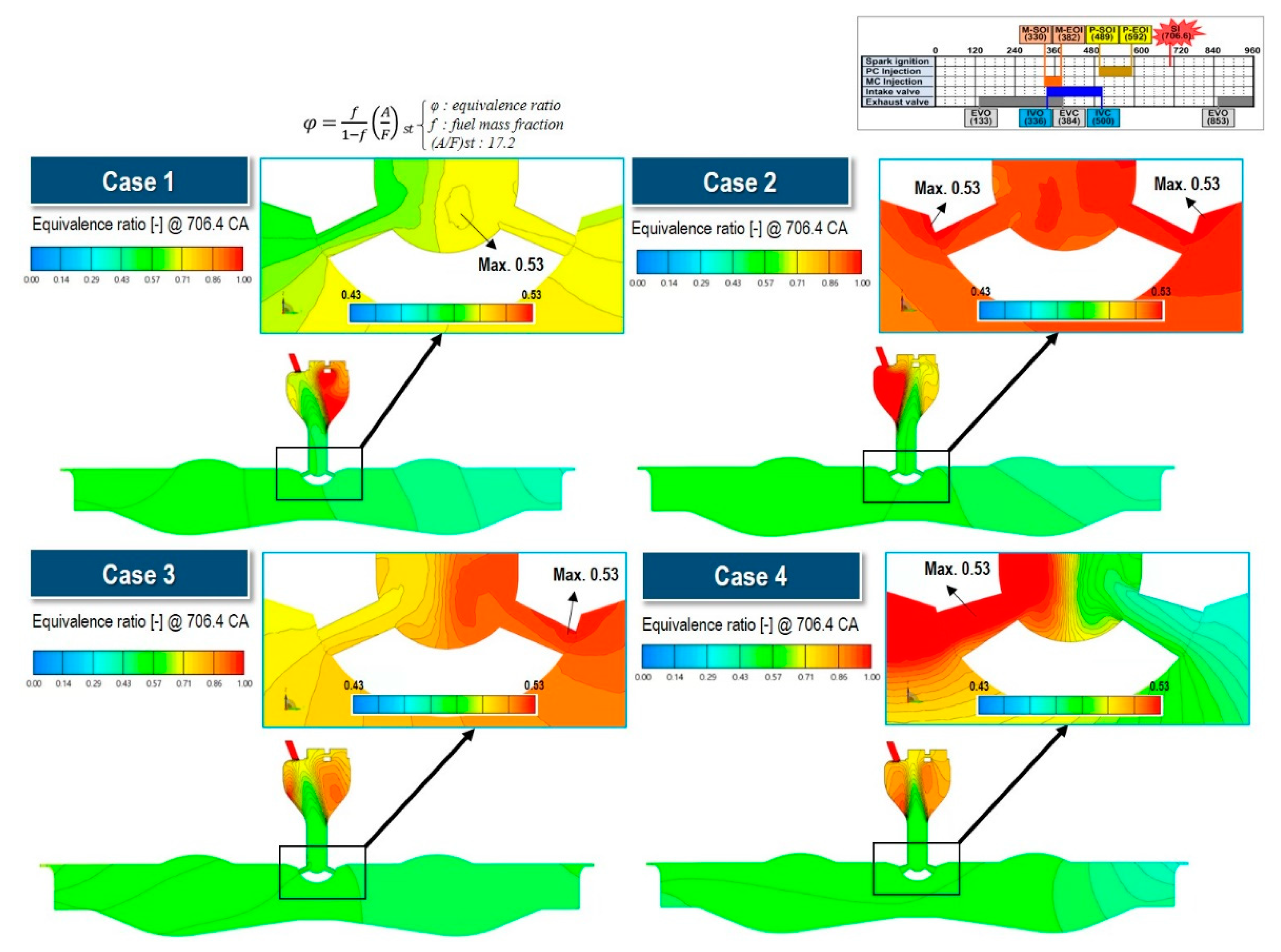

Figure 17 presents a zoomed sectional view of the equivalence ratio distribution in the pre-chamber (PC) and main chamber (MC) just before ignition (706.4° CA) for various cases. During the compression stroke, as the piston moves upward and the pressure in the MC exceeds that of the PC, the lean mixture from the MC begins to penetrate into the PC. Upon entering through the orifices or nozzles, the lean mixture undergoes intense mixing in the lower region of the PC, forming a distinct upward-moving gas column. The velocity and trajectory of this gas column are strongly influenced by the orifice geometry.

As illustrated in

Figure 17, this lean mixture column remains only partially mixed with the rich mixture in the PC until ignition occurs, which is a significant observation. Additionally, a non-uniform equivalence ratio distribution is evident around the spark plug region. These findings indicate that geometric parameters such as nozzle diameter and cone angle strongly affect both the trajectory and velocity of the lean mixture column from the MC, ultimately influencing the local fuel-air ratio at the spark plug gap.

These results suggest that modifications to the orifice geometry not only alter the fluid dynamic behavior of the turbulent jet but also influence the formation of pollutant emissions, such as CO and NOx. Furthermore,

Figure 17 illustrates that the concentration of the mixture entering through each orifice varies among cases, and the resultant gas column's momentum and direction significantly affect the equivalence ratio distribution near the spark plug gap.

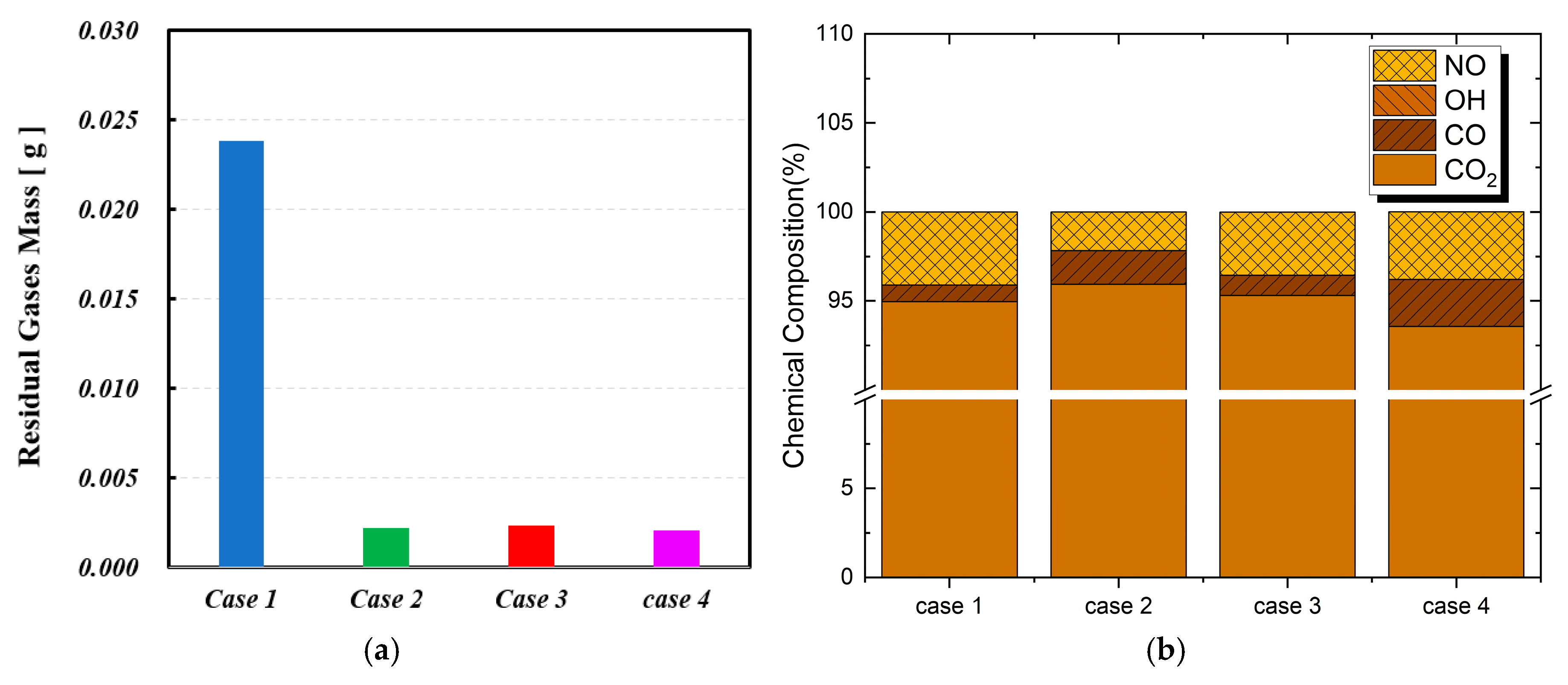

In a PCSI engine, the residence time of gases in the pre-chamber significantly influences the mass of residual gases and the chemical composition of species such as CO, NO, OH radicals, and CO₂.

Figure 18 presents (a) the amount of residual gas remaining in the pre-chamber (PC) from the previous cycle and (b) the chemical composition of the residual gas in percentage. As shown in

Table 3, the amount of residual gas is not directly proportional to the residence time of the mixture in the PC. Case 1 exhibits the highest amount of residual gas, which is 10.8 times higher than that of Case 2. This is primarily due to the increased flow resistance caused by the reduction in orifice diameter. However, despite having the same orifice diameter as Case 1, Case 2 significantly improved flow resistance by increasing the orifice cone angle. The residual gas amount in Case 3 is 9.8% of that in Case 1, while Case 4 has 10.5% of the residual gas compared to Case 1.

Meanwhile,

Figure 20(b) illustrates the variation in the chemical composition of residual gases due to changes in orifice geometry. For NO, Case 1 exhibits the highest concentration, which can be attributed to the longer residence time, as prolonged exposure to high temperatures enhances NO formation reactions.

In the case of CO, Case 4 shows the highest concentration. As indicated in

Table 3, Case 4 has the shortest residence time, leading to an increase in incomplete combustion products like CO within the pre-chamber. Additionally, the OH radical concentration is on the order of 10⁻⁶, making it barely visible in the graph. Among the residual gases, Case 4 exhibits the highest OH radical concentration at 9.475 × 10⁻⁶ (%). As an intermediate species in the combustion process, the OH radical concentration exhibits complex behavior depending on residence time and temperature. Therefore, in Case 4, which has the shortest residence time, the elevated OH radical concentration is likely attributed to its formation during the combustion reaction.

4.4. Effect of Geomatric Variations of Prechamber on Combustion Characteristics of Main Chamber

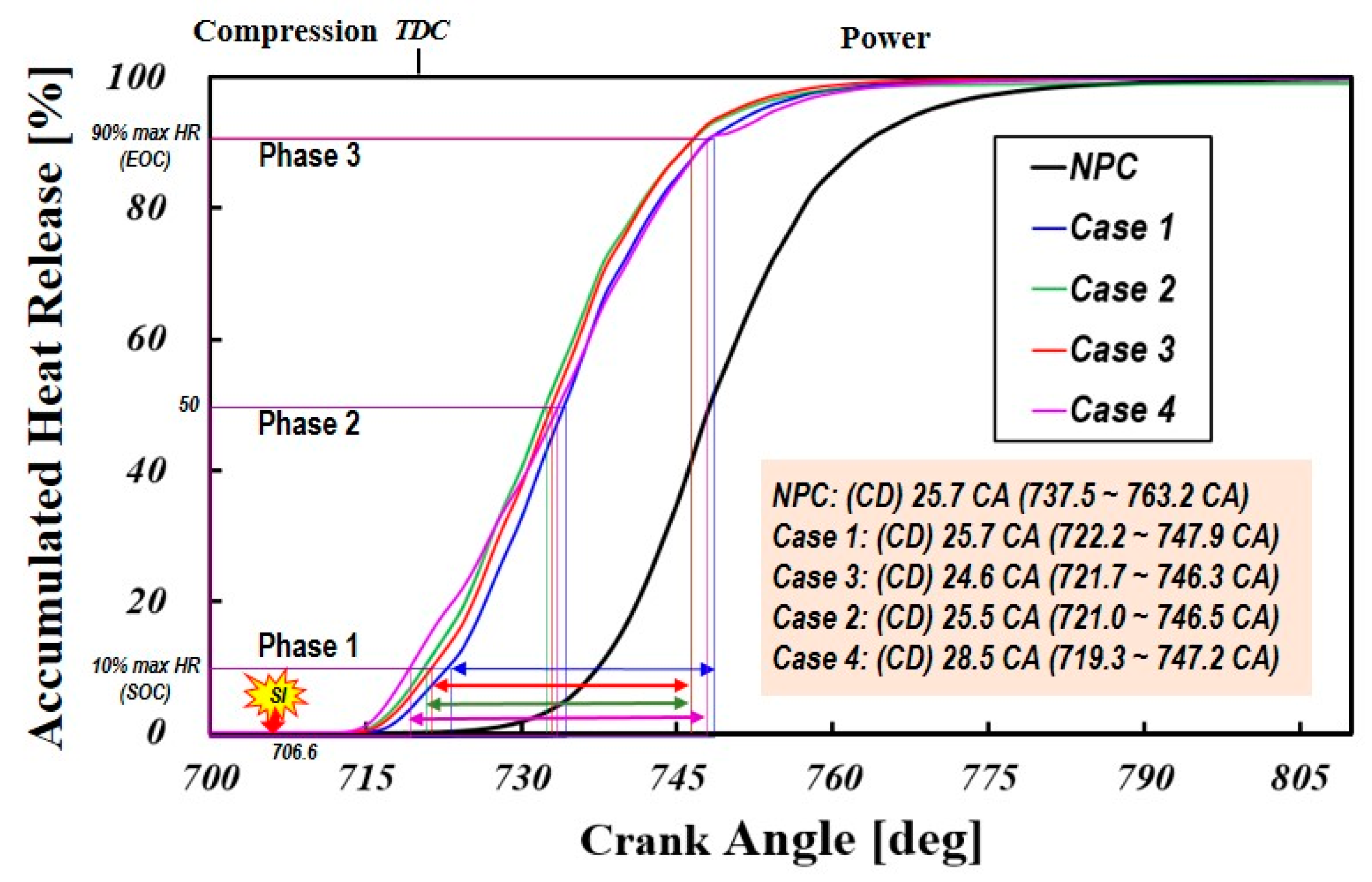

Figure 19 presents the cumulative heat release rate for various pre-chamber geometries, while

Table 4 compares combustion durations across different cases. The inclusion of a non-pre-chamber (NPC) case highlights PCSI’s impact on flame propagation and combustion timing. The results indicate that PCSI accelerates combustion initiation, with pre-chamber geometry significantly influencing early-stage combustion.

The CA0-10 duration (Phase 1), or flame development angle (FDA), represents the crank angle interval where 10% of the total fuel mass is burned. NPC exhibits the longest flame development duration (30.9 CA), nearly twice that of PCSI cases, indicating slower ignition, while Case 4 (12.7 CA) achieves the shortest Phase 1 duration, demonstrating the most efficient ignition, with Cases 1, 2, and 3 showing similar reductions (14.4–15.6 CA) compared to NPC.

During CA10-50 (Phase 2), pre-chamber jet influence weakens as combustion transitions toward a premixed flame regime, yet still affects overall flame propagation. The NPC case exhibits the fastest Phase 2 combustion (10.9 CA), while Case 4 has the longest duration (14.3 CA), indicating slower mid-stage combustion due to weaker jet penetration or a leaner main chamber mixture, whereas Cases 1, 2, and 3 show slightly shorter durations, suggesting improved combustion stability. The slower combustion rate in Phase 2 for Case 4 is primarily due to the weaker jet penetration, lower turbulence intensity, and leaner main chamber mixture, all resulting from the diverging-tapered-hole nozzle design. These factors collectively delay flame propagation and extend the mid-stage combustion duration.

NPC exhibits the longest Phase 3 duration (26.3 CA), indicating slow flame propagation due to possible flame quenching or incomplete oxidation. Among PCSI cases, Case 2 has the longest late-stage combustion (14.0 CA), while Cases 1 (13.4 CA) and 3 (13.3 CA) exhibit slightly faster combustion.

Case 3 exhibits the shortest total combustion duration (24.6 CA), indicating a well-balanced combustion process, while Case 4 has the longest (27.9 CA), suggesting a slower burn rate due to lower jet velocity and energy dissipation, which results in reduced turbulence and slower combustion progression. The NPC case (25.7 CA) shows a comparable CD to PCSI cases but demonstrates unstable combustion due to prolonged Phase 1 and Phase 3 durations. Overall, smaller orifice diameters enhance jet velocity, shortening early-phase combustion and improving pre-chamber charge ignition.

Figure 20 presents the heat release rate (HRR) curves for four different orifice geometries throughout the combustion period, along with bottom-view flame surface density iso-contours at key combustion stages. Additionally, the figure includes pressure curves for both the PC and MC, as well as the pressure differential between the two chambers during the combustion process.

The HRR profiles in

Figure 20(a-d) exhibit similar trends in terms of combustion initiation, duration, and completion, while also demonstrating a characteristic two-stage heat release process. The first peak occurs when PC jets merge and spread across the MC. Before merging, the PC jets reach their maximum flame surface area, contributing to the initial peak in the AHRR.

The second peak in AHRR is hypothesized to result from end-gas auto-ignition, which accelerates the consumption of the remaining unburned mixture. After the first peak, the PC jets merge into a hollow cone-shaped flame structure, leaving unburned air-fuel pockets between the hollow cone and the piston. Subsequently, compression due to ongoing heat release and upward piston motion triggers end-gas auto-ignition. Thus, the second peak in AHRR corresponds to this rapid auto-ignition event. These results are in exact agreement with experimental findings of previous literature from natural gas PCSI engines [

54].

The first HRR peak is jet-momentum driven, suggesting a mixing-controlled premixed combustion phase. However, the scaling inconsistency of the second HRR peak and the absence of a significant driving pressure differential (ΔP ~ 0) behind the pre-chamber jets suggest a transition from a mixing-controlled to a kinetically-controlled combustion regime. This transition coincides with the deceleration of pre-chamber jets due to diminishing driving pressure and charge entrainment, leading to a flame front evolution process wherein combustion is no longer solely mixing-driven. Unlike diesel combustion, where the rate-limiting factor is fuel-air mixing, pre-chamber combustion is governed by the interaction between hot burned gases and unburned fuel-air mixtures, rendering the process largely independent of laminar flame speed. The second-stage heat release is more intense and prolonged, primarily driven by bulk in-cylinder flow and turbulence, though as the main chamber mixture becomes leaner, combustion is increasingly influenced by chemical kinetics. In the later stages of heat release, combustion progression becomes less dependent on nozzle geometry, though nozzle-induced flow structures continue to play a role in determining flame propagation characteristics.

Previous studies indicate that main chamber ignition is inherently asymmetric, as combustion emerges from pre-chamber jets at different timings [

41,

54]. However, sequential flame surface density contour plots in

Figure 20 reveal that flame propagation from each orifice remains largely uniform, likely due to the limited influence of large-scale turbulence in the main chamber. In contrast, during the early flame development stage, flame propagation exhibits non-uniform characteristics, as illustrated in

Figure 22(a), where a long flame jet is observed near the spark plug in the initial moments of combustion onset.

As shown in

Table 4, the flame development angles are 15.6 CA, 14.4 CA, 15.1 CA, and 12.7 CA in cases 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Additionally, pre-chamber jet merging occurs most rapidly in Case 4, attributable to the diverging-tapered nozzle design, which accelerates jet dispersion and flame front interaction. Initial flame formation occurs between FR1 and FR2, where the flame divides into eight discrete jets upon exiting the pre-chamber nozzle holes and propagates individually. In Cases 1, 2, and 3, these eight jet flames merge gradually after FR2 (before TDC), whereas in Case 4, jet merging occurs significantly earlier due to the diverging-tapered-orifice design. In Case 4, the initial flame development phase is accelerated, leading to higher combustion rates before TDC (720° CA); however, after TDC, the heat release rate undergoes a sharp decline, causing a relatively delayed combustion progression.

Figure 20(b) illustrates that higher pre-chamber heat release and pressure buildup enhance jet penetration and kinetic energy dissipation, leading to the formation of turbulent mixing eddies in the main chamber. The impact of pre-chamber cone angle on jet dispersion is also evident, as a larger cone angle facilitates stronger jet interaction with the main chamber charge, further enhancing mixing efficiency. Notably, Case 3, as shown in

Figure 20(c) which features an intermediate cross-sectional area of orifice, exhibits the most accelerated heat release in the early combustion stages, indicating an optimal balance between jet velocity and energy content. The orifice dimensions in Case 3 are sufficiently large to prevent jet flame quenching, ensuring stable combustion propagation.

A critical observation in

Figure 20(d) is that the maximum jet driving force develops more rapidly in Case 4 than in other cases. This phenomenon arises due to the optimized spatial distribution of turbulent jets and shorter penetration depth, resulting in a larger flame jet angle, which promotes broader and shorter flame structures, increasing the probability of plume interaction. Additionally, the diverging-tapered nozzle increases the flow separation distance between the jet core and the nozzle wall, enhancing air entrainment into the nozzle and improving mixture formation within the main chamber. As a result, the radial velocity at the nozzle exits increases, contributing to improved mixture stratification. As combustion progresses, pre-chamber jet momentum decreases, transitioning from turbulent jet-driven propagation to a mushroom cloud formation mechanism. This transition results in faster jet head velocity decay, which slows the merged flame jet progression. Another distinct feature of Case 4 is the pronounced dip between the first and second heat release peaks, suggesting that pre-chamber jet combustion exhibits a weaker energy-carrying effect and a delayed ignition trigger compared to other orifice’s geometries due to the fact that the expanding cross-section of the nozzle reduces jet penetration, leading to weaker turbulence and less effective charge mixing, delaying flame propagation. This disadvantageous combustion characteristic further exacerbates the retarded second-stage heat release, leading to extended total combustion duration relative to other nozzle configurations.

Figure 20.

Sequential plots of: heat release rate along with main-chamber pressure, pre-chamber pressure, pressure difference an d flame surface density contour from the bottom view (a) case 1; (b)case 2; (c)case 3; (d)case 4.

Figure 20.

Sequential plots of: heat release rate along with main-chamber pressure, pre-chamber pressure, pressure difference an d flame surface density contour from the bottom view (a) case 1; (b)case 2; (c)case 3; (d)case 4.

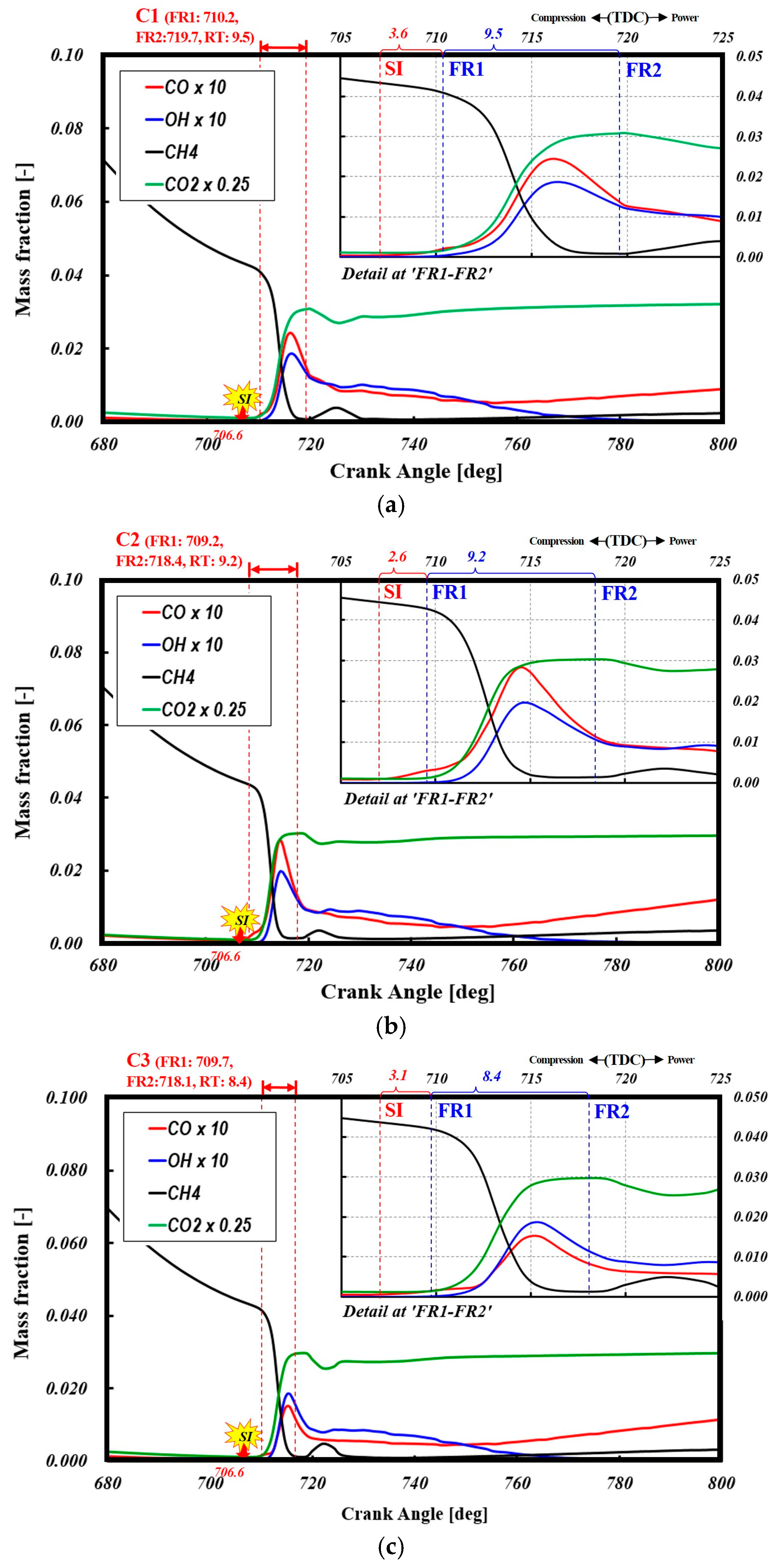

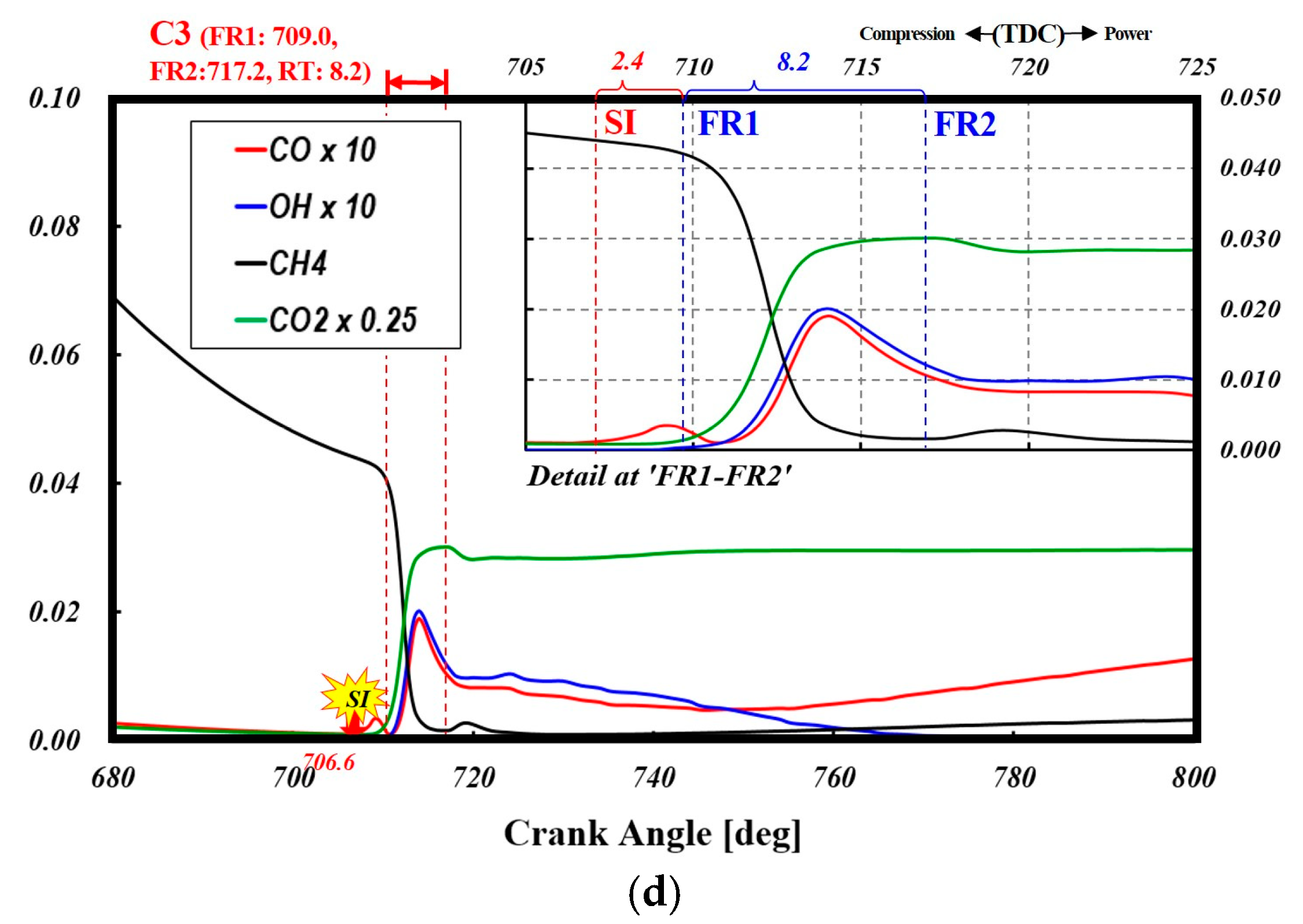

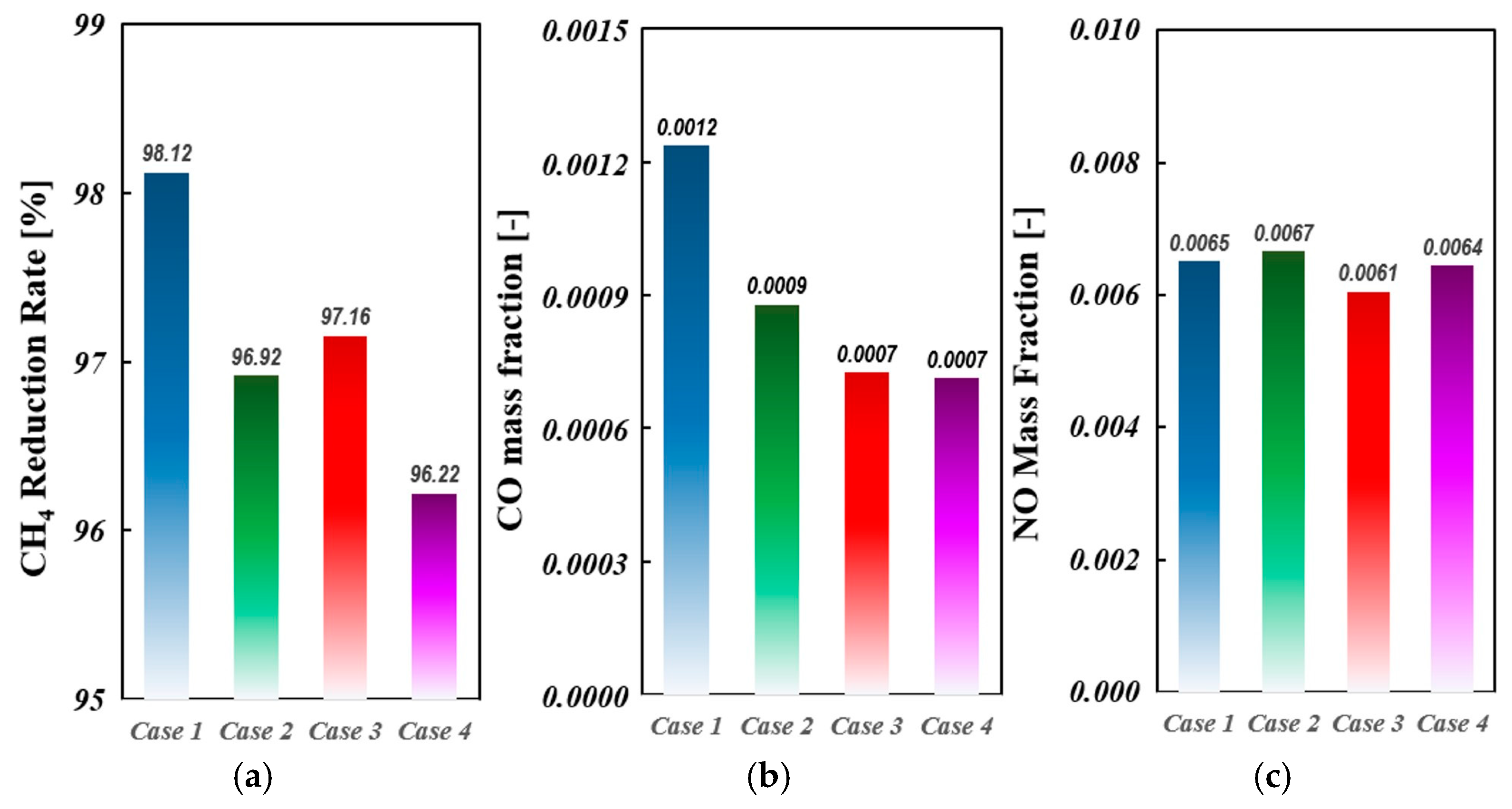

4.5. Analysis of Chemical Composition and Emission Characteristics

Figure 21(a-d) presents the major chemical species formed in the pre-chamber across various cases, providing insight into the timing and characteristics of flow reversal from the main chamber to the pre-chamber. The plots illustrate the mass fraction relative to the instantaneous total mass, where each time step accounts for the dynamically updated total mass. These traces illustrate the temporal evolution of fuel and intermediate species critical to the ignition and combustion processes. Vertical dashed red lines indicate flow reversal events. The box in the upper right corner of each graph provides a magnified view of the residence time interval between the two backflow events. As previously established, the throat diameter is a critical parameter influencing pre-chamber peak pressure. A smaller orifice diameter increases residence time, allowing for a greater pressure buildup, whereas a larger orifice diameter facilitates earlier pressure relief, modifying combustion phasing. Combustion in the pre-chamber initiates as spark energy dissociates fuel and oxygen molecules, forming OH radicals. As shown in

Figure 21(a-d), immediately after the start of spark, CH₄ rapidly depletes, causing OH radical formation. As combustion progresses, CO and OH concentrations peak at the first heat release peak (

Figure 17), promoting CO oxidation to CO₂, which also reaches its maximum simultaneously. Since OH indicates reaction zones and heat release, it is a key parameter for analyzing flame structure and local fuel oxidation. The OH radical peak emerges within the residence zone, indicating the completion of pre-chamber charge combustion. If complete oxidation is not achieved, a significant portion of unburned hydrocarbons may be expelled during the exhaust stroke, adversely affecting combustion efficiency [

19,

29].

Following the second flow reversal (FR2), fresh charge and partially reacted species flow back into the pre-chamber, triggering localized combustion (post-flame reactions). This is confirmed by the second CH₄ peak after FR2, indicating that high pre-chamber temperatures facilitate secondary ignition and radical formation, leading to additional combustion events. Near FR2, CO oxidation halts before decreasing, attributed to declining OH radical concentration and temperature drop [

12].

The temporal evolution and peak concentration profiles of OH radicals inside the pre-chamber exhibit no significant differences across the four orifice geometries. However, the maximum concentration and temporal evolution of CO show noticeable variations. This can be attributed to the fact that OH radicals are highly reactive intermediate species that rapidly reach a quasi-steady-state concentration during combustion. Additionally, since OH is continuously regenerated in reaction zones, its steady-state concentration remains relatively stable, independent of minor variations in orifice geometry.

In contrast, CO, as a combustion product, is strongly influenced by post-flame oxidation, residence time, and turbulence-driven mixing. Differences in orifice geometry affect flow dynamics, mixing intensity, and temperature distribution, leading to variations in CO oxidation rates.

In this study, Cases 1 and 2, which feature smaller orifices, increase flow restriction, prolong CO residence time, and result in higher CO accumulation. Conversely, Case 3, which has higher scavenging efficiency and greater turbulent mixing intensity, exhibits relatively lower CO emissions. However, OH radicals, being short-lived and equilibrium-driven, are less affected by these geometric variations, leading to minimal or no change in their concentration.

Figure 22 presents the flame development during the combustion period (712–732 CA) for four different orifice geometries in the y-y’ cross-section, using iso-contours of flame surface density. A distinct feature observed is the occurrence of post-flame combustion after FR2, attributed to fuel and combustion product backflow from the main chamber into the pre-chamber. In Case 1, post-flame combustion initiates earliest (728 CA) compared to other cases due to the highest flow resistance from the main chamber to the pre-chamber, which delays the influx of fuel and combustion products. Specifically, a longer residence time interval delays the flow reversal (FR) event, resulting in later post-flame reactions. As shown in

Table 3, Case 1, with the longest residence time, exhibits strong post-flame reactions downstream of the pre-chamber at 728 CA, whereas Case 4, with the shortest residence time, shows earlier post-flame reactions at 720 CA. Case 2 exhibits the fastest and most intense flame development, attributed to the highest PC-MC pressure difference, as observed in

Figure 13. In Case 4, the diverging-tapered orifice produces the widest initial turbulent jet angle, leading to better spatial flame distribution during early flame development.

These findings indicate that lower resistance to reverse flow facilitates earlier post-flame combustion. Furthermore, post-flame ignition consistently occurs after FR2 due to fuel and combustion product entrainment into the pre-chamber.

Figure 22.

Temporal sequential plot of distribution of flame surface density in pre and main chamber.

Figure 22.

Temporal sequential plot of distribution of flame surface density in pre and main chamber.

Figure 23 illustrates the CH₄ consumption rate during residence time, along with the amounts of CO and NO produced during the gas residence time. As previously reported, a longer PC residence time tends to yield more complete combustion products than a shorter one, which directly influences the composition of the jets. The CH₄ consumption rate increases proportionally with residence time, and the amount of CO produced shows a similar proportional relationship. However, in case 3, improved turbulent mixing and the high turbulent kinetic energy near the spark plug gap—favorable for stable flame propagation, as shown in

Figure 15(a)—result in a shorter residence time interval compared to case 2, yet the flames burn more completely. However, NO production does not exhibit the same proportionality with residence time. Because Nox emissions depend not only on residence time but also on factors such as the concentration distribution of the air-fuel mixture inside the pre-chamber, the presence of localized hot spots and rich pockets, and enhanced mixing that ensures complete combustion—thereby reducing UHC and CO while simultaneously suppressing Nox formation. Consequently, Nox generation in the pre-chamber is influenced by residence time as well as by factors such as higher turbulent kinetic energy, which accelerates chemical reactions by increasing mixing rates, and uniform mixing in the main chamber, which minimizes rich zones that contribute to Nox formation. As demonstrated in

Figure 15(a) and

Figure 17, case 3 exhibits the lowest Nox emissions by enhancing mixing through higher turbulent kinetic energy while avoiding the formation of excessive local rich pockets within the pre-chamber.

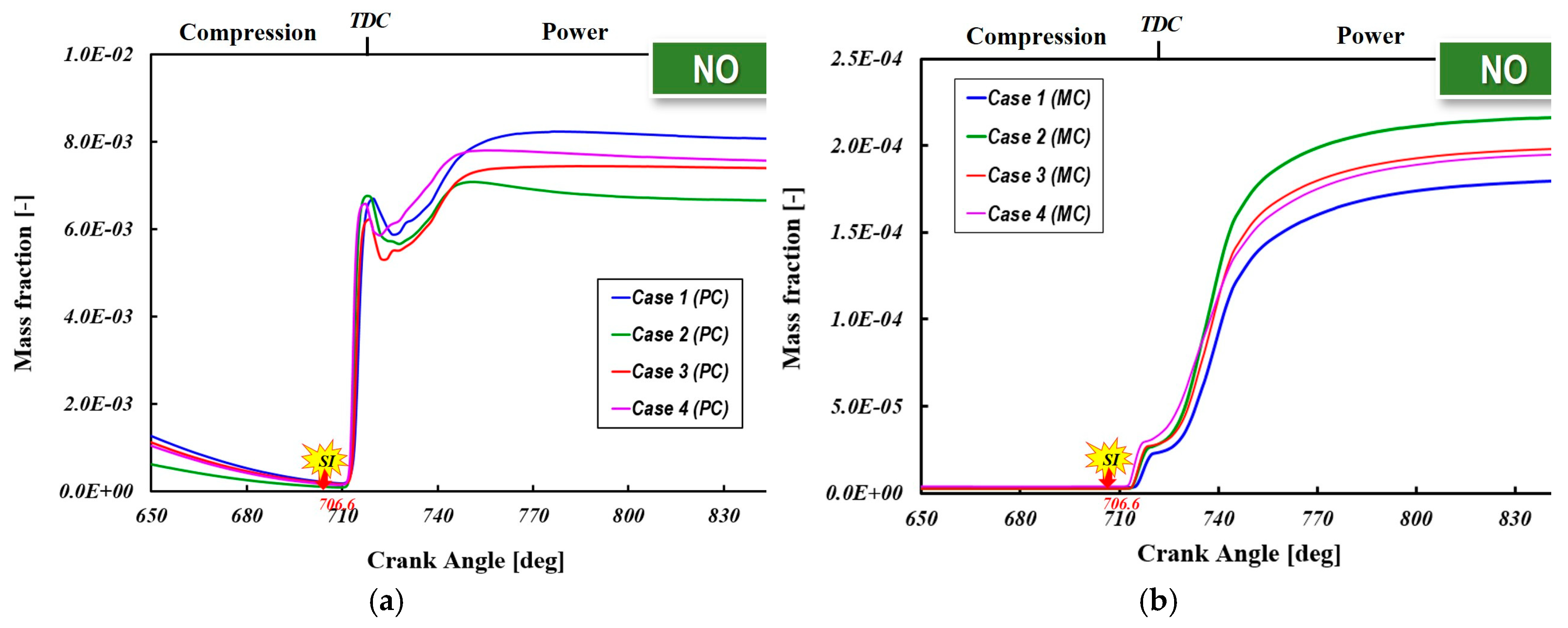

The

Figure 24 shows how NO forms and evolves over the combustion cycle within the PC and MC of a PCSI engine fueled by natural gas, comparing four different orifice (nozzle) geometries. Around the spark timing (near 706°CA), the flame initiates in the pre-chamber. As the flame expands, local temperature and pressure increase, promoting the formation of thermal NO. Any geometry that intensifies local heat release or creates high-temperature regions will tend to increase NO formation early in the combustion process. Noteworthy feature of

Figure 24(a) is that that as the PCSI system approaches the FR2 timing, NO emissions gradually decrease. This occurs because a strong jet flow rapidly transfers combustion products into the main chamber, and the mixture is very lean, the peak NO level can be limited. Subsequently, when the main chamber pressure exceeds that of the pre-chamber, backflow occurs, allowing unburned fuel, active radicals, and combustion products to re-enter the pre-chamber. This backflow can initiate secondary ignition and radical formation, leading to additional combustion events and a sharp increase in NO emissions. After NO concentrations reach a peak, they then stabilize or “freeze,” as combustion temperatures drop and mixing disperses the hot regions.

NO typically forms most rapidly at high temperatures and near-stoichiometric conditions. If the design prolongs high-temperature residence time in the pre-chamber (due to slower venting or less mixing), NO formation can continue to rise (case 1). The difference in final NO levels among the four cases reflects how effectively each orifice design manages local temperature, residence time, and mixing intensity.

Figure 24(b) presents the temporal evolution profile of NO in the main chamber for case 2. In this case, the highest NO emissions are observed, which are attributed to the rapid temperature rise caused by strong auto-ignition and subsequent rapid combustion following the second peak of the heat release rate, as shown in

Figure 20(b). In contrast, case 1 exhibits the lowest NO emissions; as indicated in

Figure 20(a), turbulent jets with higher entropy discharged into the main chamber promotes mixing and heat release over a broader area, thereby suppressing localized rapid temperature increases and maintaining a lower NO level. Cases 3 and 4 demonstrate that an increased effective flow area leads to a more uniform combustion distribution and suppresses prolonged high-temperature zones, resulting in lower NO peaks. These findings underscore that improved mixing through turbulent jets—by preventing localized rich zones and distributing heat more evenly—is critical for reducing NO emissions. Hence, in PCSI engines, the pre-chamber is not merely an ignition source for the main chamber charge; it is designed to generate large-scale mixing eddies or plumes that facilitate the consumption of the main chamber charge, and when optimized, it serves as an effective means to suppress emissions such as NO and CO.

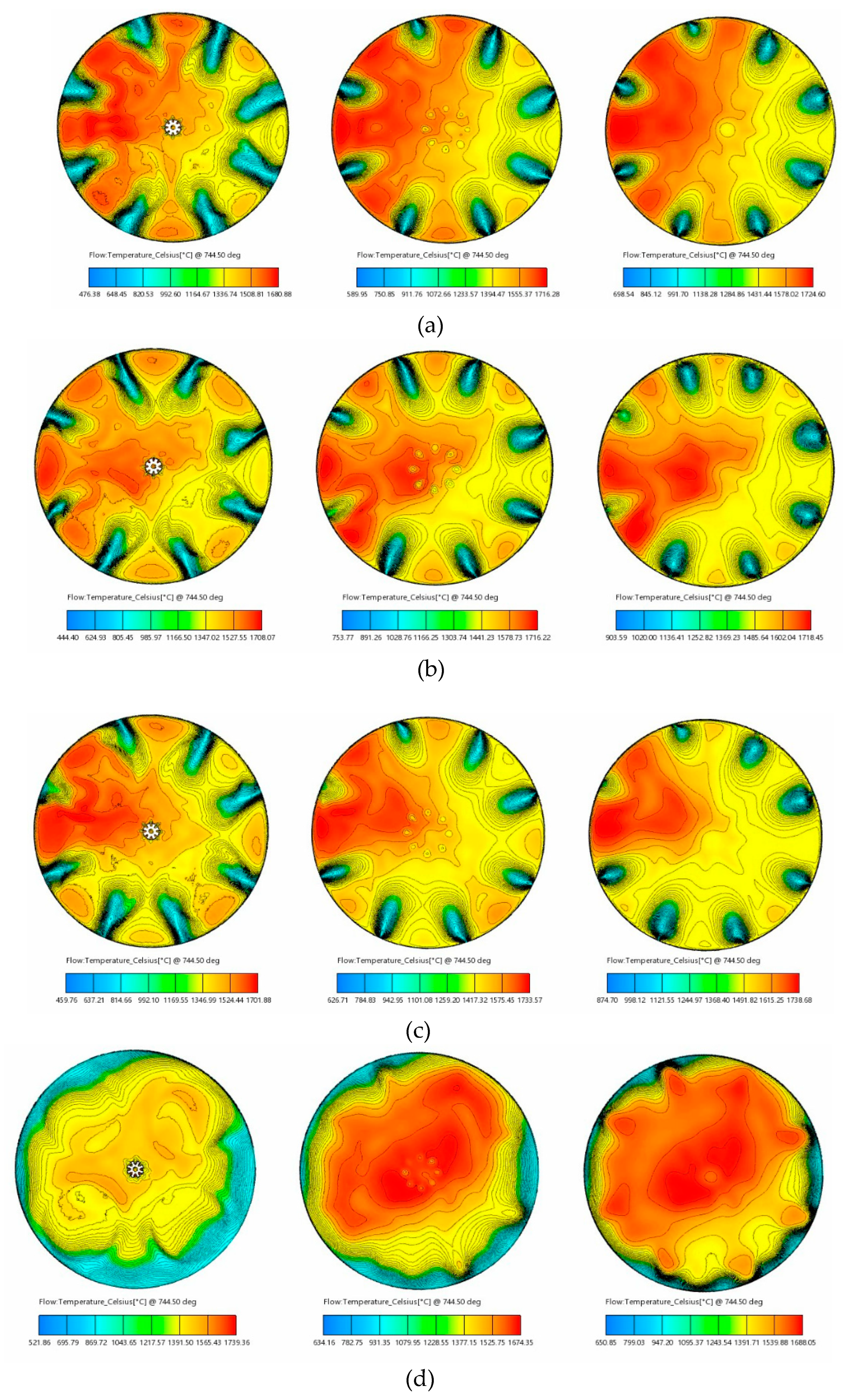

Figure 25 displays bottom views of the in-cylinder mixture temperature distribution at 745°C for three cross-sectional areas indicated within the black box, for four different orifice geometries. Notably, localized hot spot zones exceeding 1800 K and quenching zones—resulting from turbulent jets impinging on the cylinder wall and piston surfaces—are clearly observed. These hot spot zones are generated by the interaction between the jets and the main chamber flow, and they may temporarily elevate temperatures, locally enhancing thermal NOx formation. Optimization of the orifice and pre-chamber volumes is required to mitigate localized NOx formation by distributing heat more evenly. In this study, the presence of eight orifices results in eight locally distributed quenching zones on the piston surface and the cylinder wall. The area and shape of each quenching zone differ because the momentum and flow rates of the hot jet plumes discharged from each of the eight orifices are not uniform, and these turbulent jets interact with the in-cylinder flow before reaching the quenching zones. The existence of these quenching zones, where combustion temperatures are relatively low, can lead to incomplete flame reactions, resulting in increased unburned hydrocarbon (UHC) and CO emissions. In contrast, in the case of Case 4, a quenching zone is not observed. This is attributed to the characteristics of the diverging-tapered orifice, as shown in

Figure 20(d), where the flow velocity decreases slightly due to the expanding cross-sectional area, thereby reducing the penetration depth of the turbulent jet. Consequently, the combustion rate in the latter stages is significantly slower compared to other cases, which, due to the delayed reaction time, may increase the potential for NO formation. Ultimately, the CFD analysis in this study demonstrates that by coupling the simulation of the PCSI engine's emission characteristics with that of its in-cylinder thermal-fluid dynamics, the orifice and pre-chamber geometries can be optimized early in the design process, facilitating the development of high-efficiency, low-emission PCSI engines. However, to obtain more accurate results, there is a critical need to develop numerical models specifically tailored to lean conditions that account for turbulence–chemistry interactions and NOx emission mechanisms.