Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

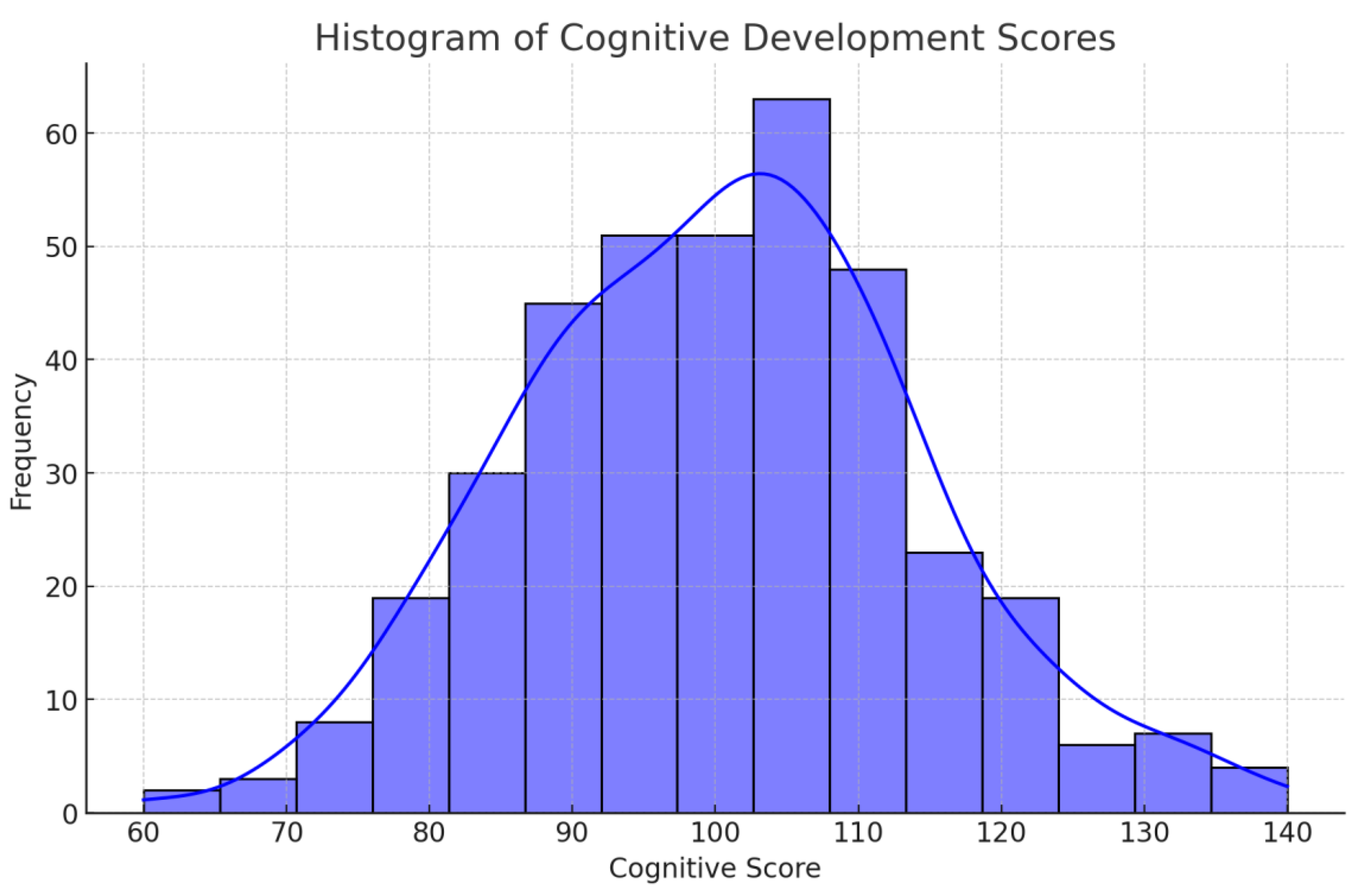

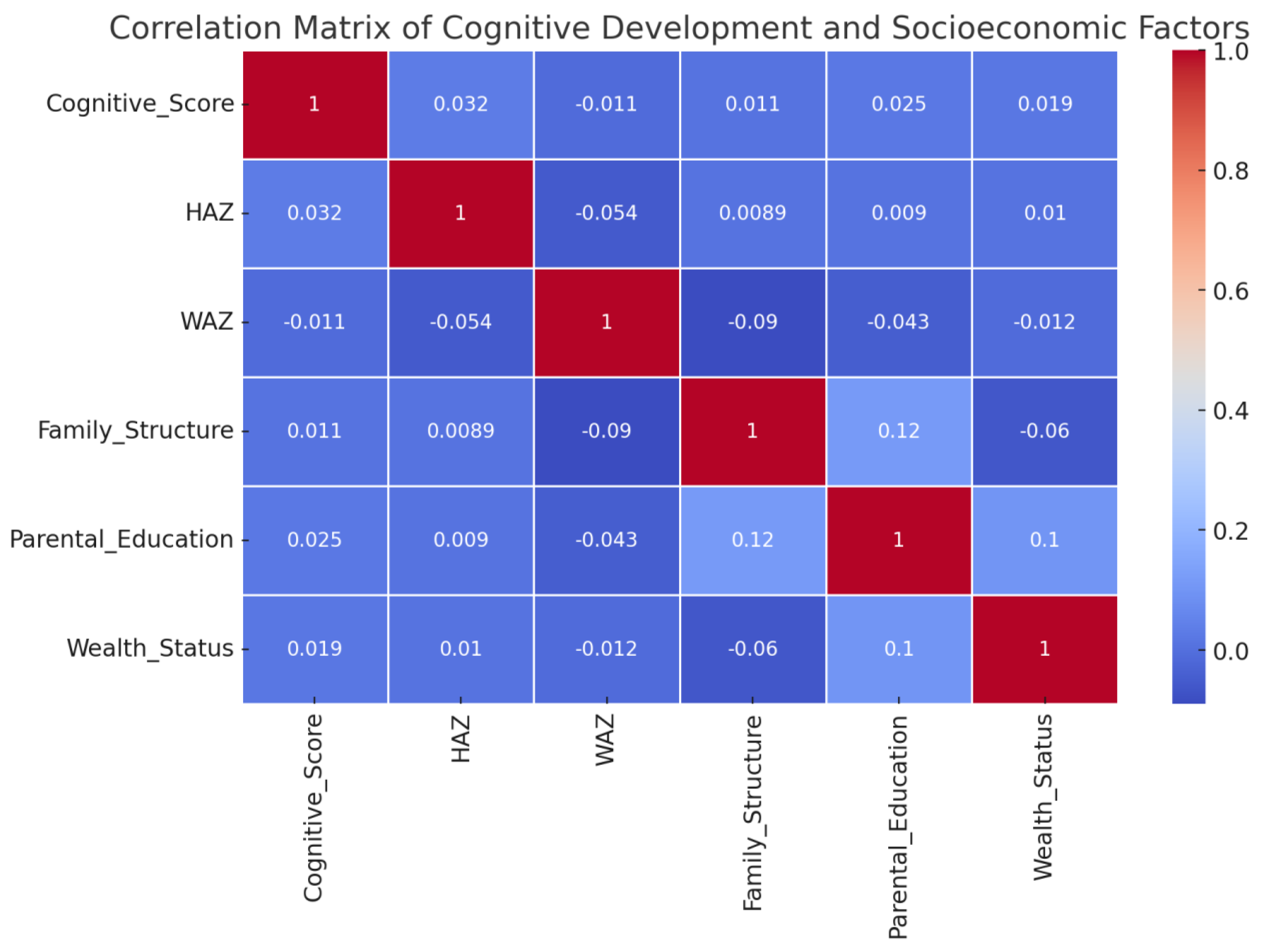

Nutritional deficiencies negatively impact cognitive development in preschoolers, affecting brain growth and causing behavioral and educational consequences. This study evaluates the relationship between nutritional status and cognitive development, highlighting the public health and educational implications of cognitive developmental delays and the increasing malnutrition among children. This study aimed to explore the factors influencing cognitive development in preschoolers (ages 3-5) in Rupandehi District, Nepal. A cross-sectional survey design was employed, using multi-stage random sampling with data collected from 379 children. Information on the children’s socio-economic and demographic status, as well as their stage of cognitive development, was gathered through scheduled interviews and direct observation. Nutritional status was assessed using anthropometric measurements, specifically Height-for-Age (HAZ) and Weight-for-Age (WAZ), which emerged as significant predictors of cognitive development. Better nutritional status was strongly correlated with higher cognitive development scores. Family structure also played a critical role, with children from joint families exhibiting lower cognitive development scores. Age was a marginally significant factor, indicating a slight decline in cognitive development as children grew older. The findings emphasize the need for interventions targeting improved child nutrition and addressing family dynamics alongside policies that promote equitable educational opportunities. These results provide valuable insights into how nutrition, family structure, and age influence early childhood cognitive development, informing strategies for effective interventions and policy recommendations. Public health authorities should focus on enhancing the educational and nutritional status of preschoolers, as preschool significantly impacts their cognitive and productive development.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Materials

2.1. Methods and Procedures

2.2. Study Design and Setting

2.3. Data Collection Tools

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Determinants Factors of Cognitive Development

3.3. Analysis of WAZ and HAZ Scores with Demographic Variables

3.4. Regression Analysis of HAZ and WAZ with Demographic Variables

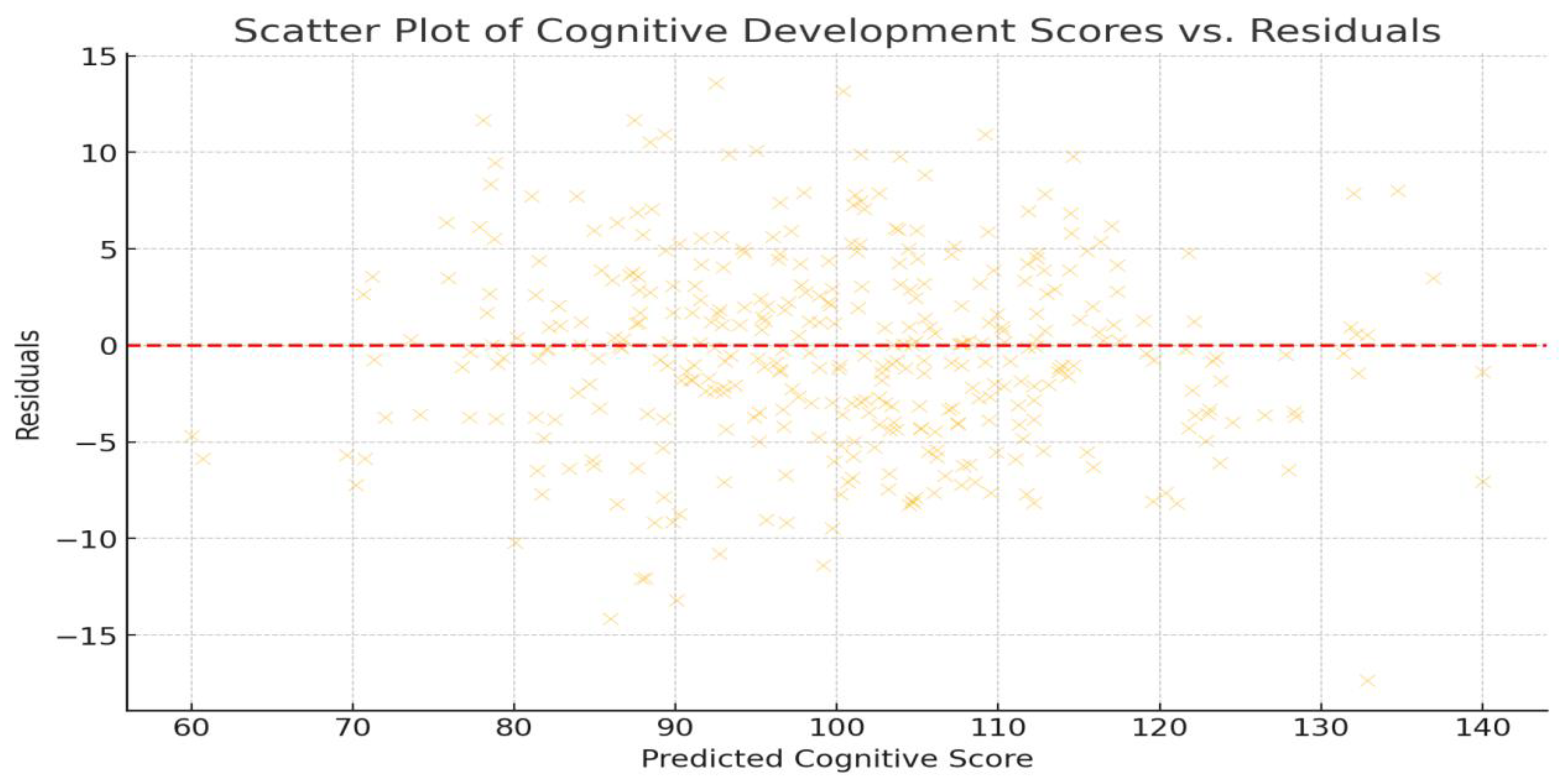

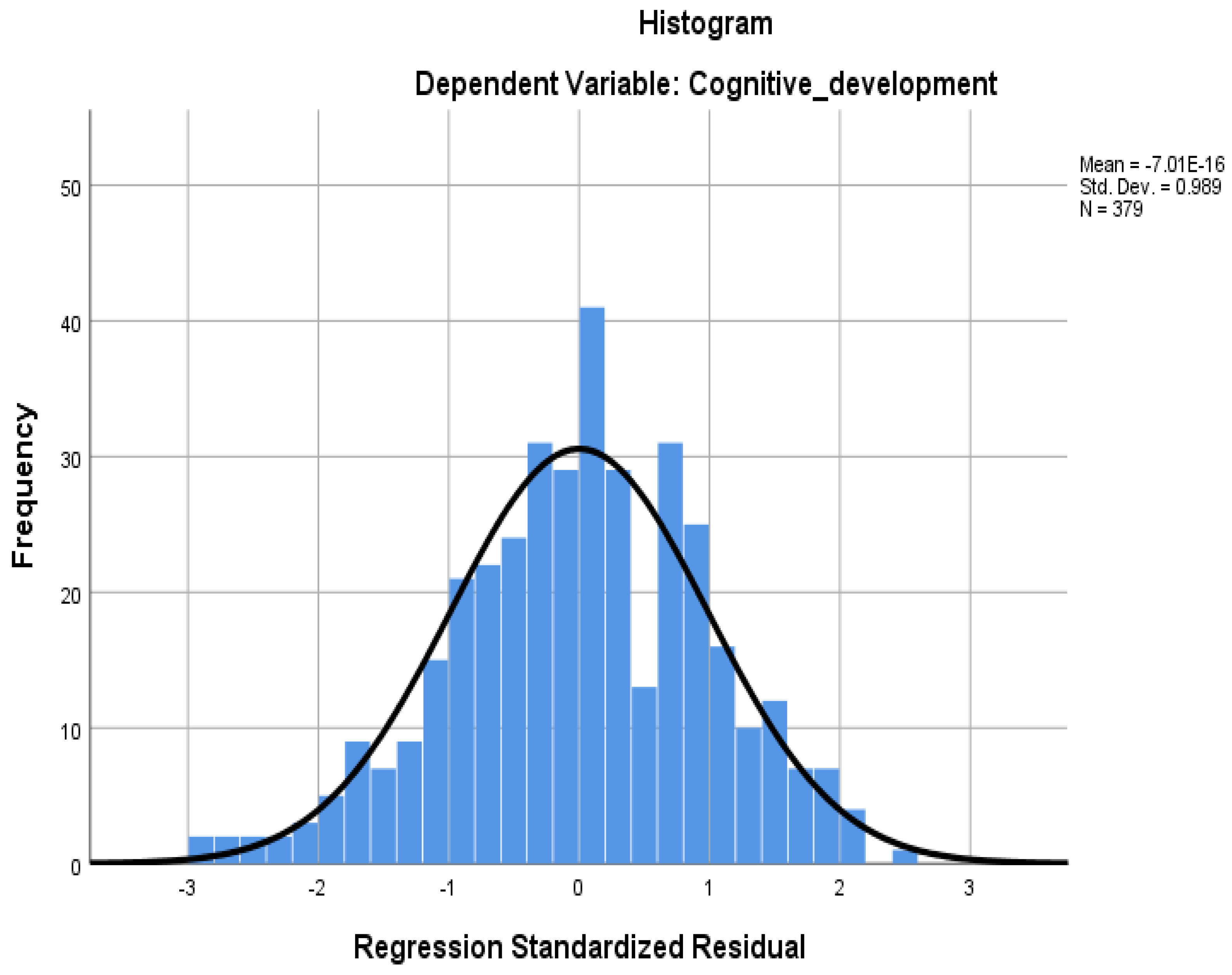

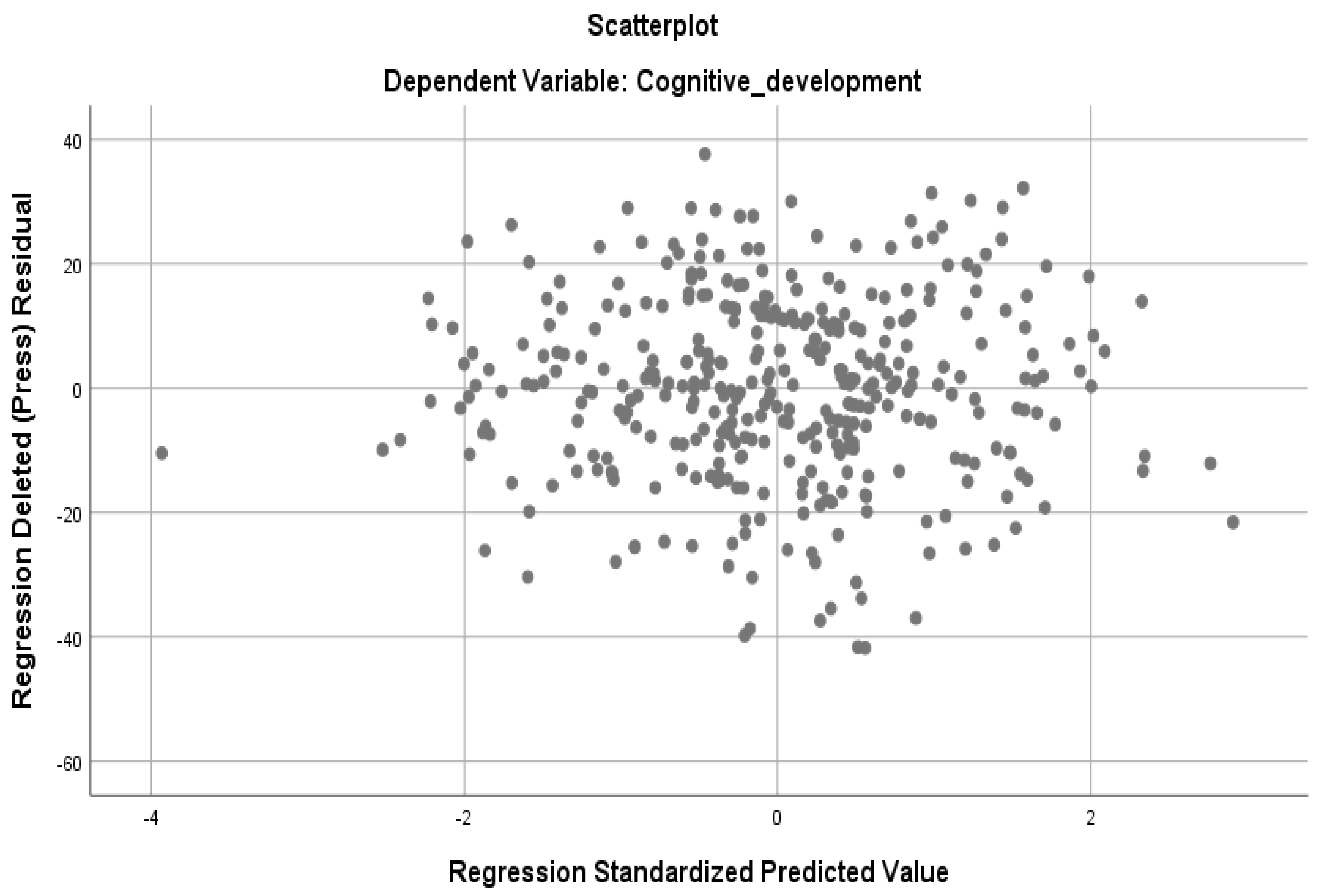

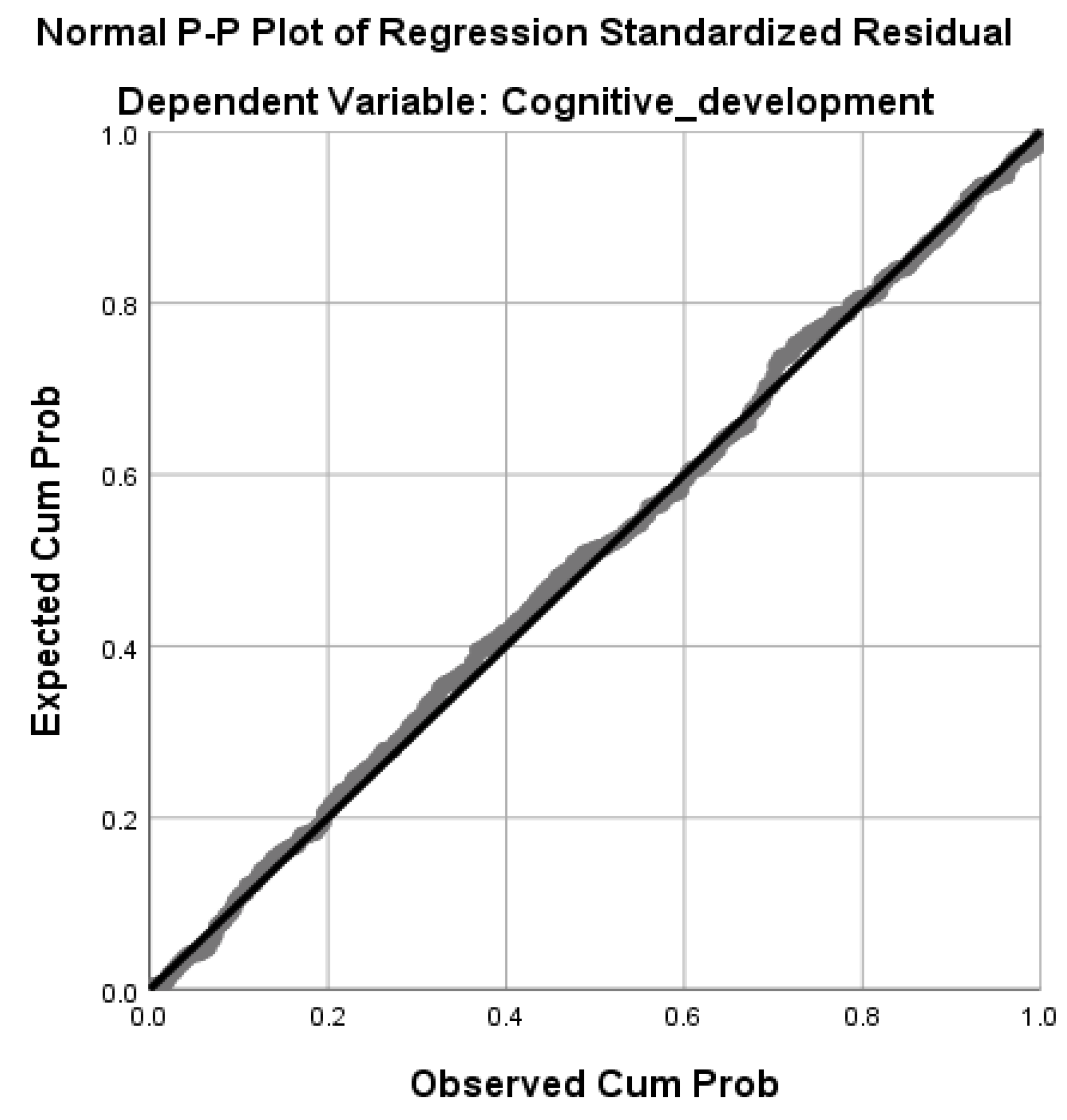

3.5. Multiple Regression Analysis: Predictors of Cognitive Development

4. The Summary of the Study's Findings

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

- ·

- The final sample comprised 379 preschool children, with a nearly equal distribution of males (50.7%) and females (49.3%).

- ·

- The majority of children were aged four (45.1%) or five (46.2%) years, and most families had two or fewer children (71.5%).

- ·

- A significant portion of children (52.5%) lived in joint family structures.

- ·

- Parental education levels were relatively low, with about 46.2% of mothers and 49.6% of fathers completing basic education. Illiteracy was more common among mothers (23.7%) than fathers (14.3%).

- ·

- Regarding wealth, children were evenly distributed across wealth backgrounds, with 19.3% in the poorest and 21.4% in the richest category.

- ·

- Nutritional status assessments showed that 15.0% of children were severely stunted, 4.0% were obese based on height-for-age (HAZ), 15.3% were severely wasted, and 2.9% were obese based on weight-for-age (WAZ).

4.2. Determinants of Cognitive Development:

- ·

- Age: Three-year-old children had the highest mean cognitive development score (M=109.57, SD=21.61).

- ·

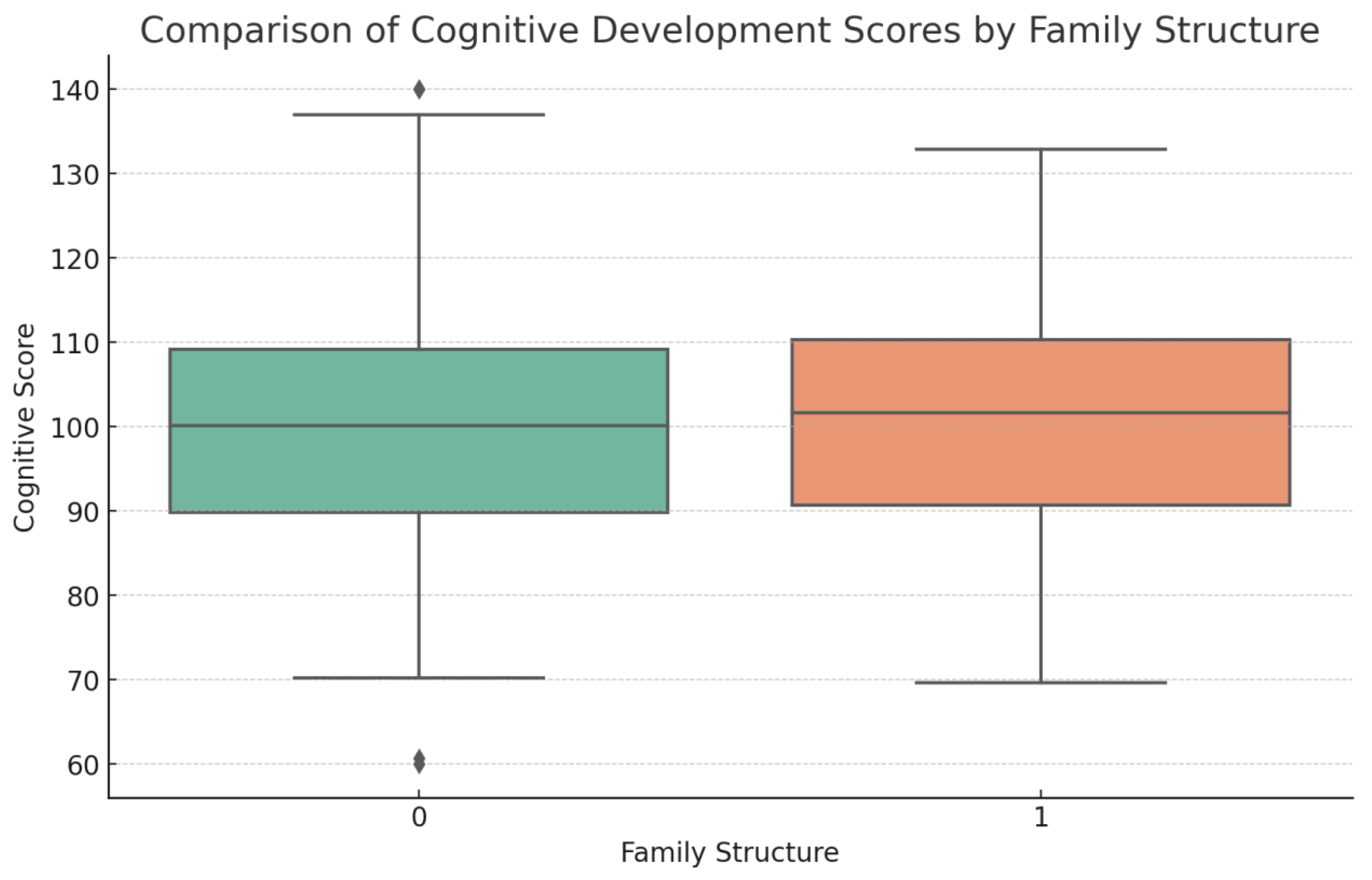

- Family Structure: Children from nuclear families had significantly higher mean cognitive development scores (M=103.83, SD=14.23) compared to those from joint families (M=100.28, SD=16.12).

- ·

- Parental Education: Children whose mothers (M=106.12, SD=15.17) and fathers (M=104.96, SD=15.96) had secondary or higher education had the highest cognitive development scores.

- ·

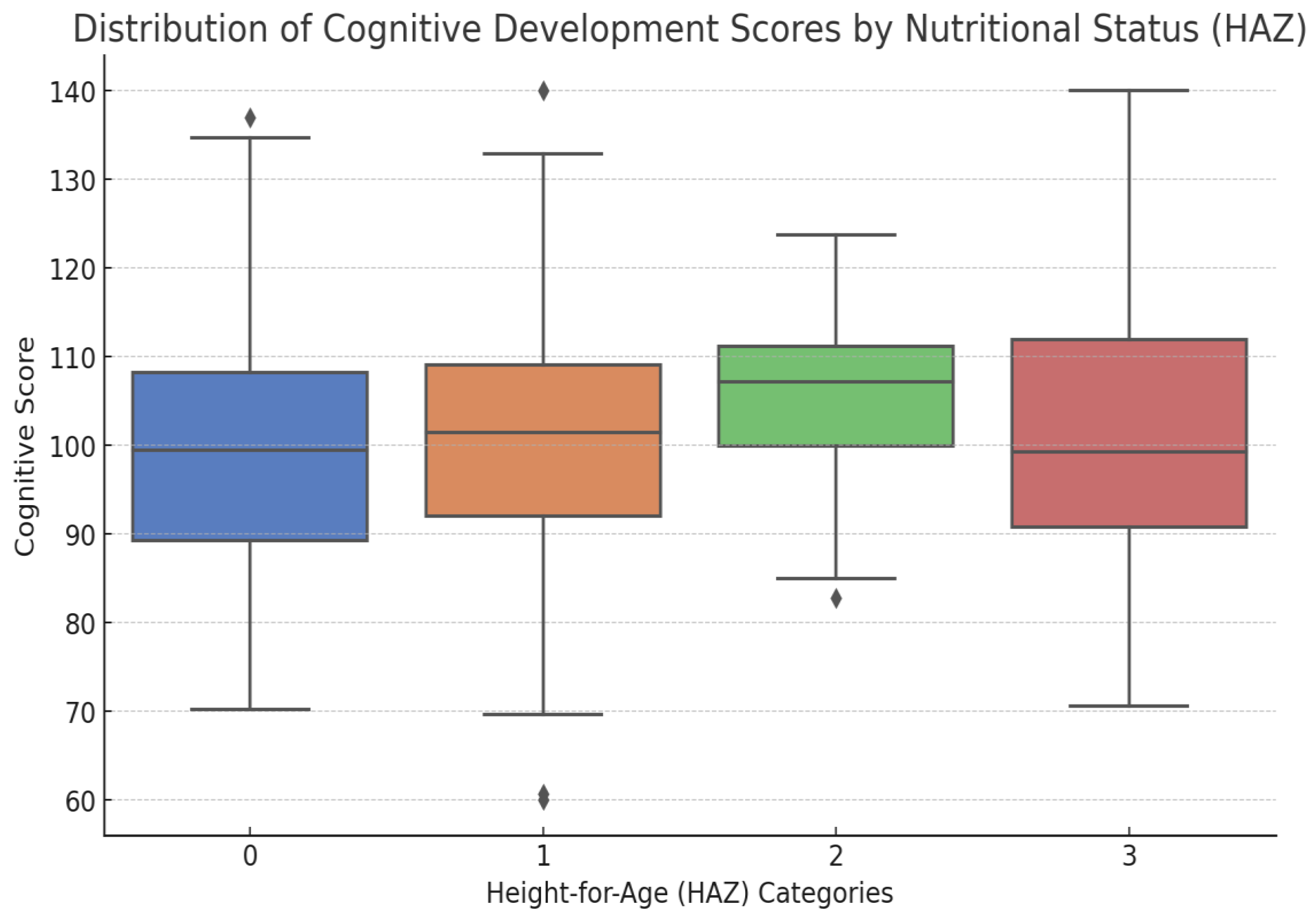

- Nutritional Status: Children with normal HAZ scores had the highest cognitive development scores (M=105.38, SD=15.43), while severely stunted children had the lowest scores (M=96.08, SD=11.88).

4.3. Determinants of Nutritional Status (WAZ and HAZ):

- ·

- Family Size: Children from families with two or fewer children had better nutritional outcomes, with lower WAZ z-scores (-0.85) compared to those from larger families (-1.31).

- ·

- Wealth Status: Wealthier households had better nutritional outcomes, with children from the richest family background showing the lowest mean WAZ z-score (-1.54) and the poorest background showing the highest mean WAZ z-score (-0.80).

4.4. Regression Analysis with Independent Variables

- ·

- HAZ Score: Wealth status was a significant predictor of HAZ (β = 0.258, p = 0.0001), explaining 6.4% of the variance. Other factors, such as child age, joint family structure, and parental illiteracy, were not significant.

- ·

- WAZ Score: Wealth status (β = 0.318, p = 0.0001) and child age (β = -0.105, p = 0.034) were significant predictors of WAZ, with age negatively influencing nutritional outcomes. This model explained 12.4% of the variance in WAZ.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Funding

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

References

- Abreha, S. K., & Zereyesus, Y. A. (2021). Women's empowerment and infant and child health status in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I. P. (2022). Job Satisfaction in Public Health Care Sector, Measures Scales and Theoretical Background. European Journal of Environment and Public Health, 6(2), em0116. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I. P., & Syrou, N. F. (2022). Associations and Correlations of Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Burn out in Public Health Sector. European Journal of Environment and Public Health, 6(2), em0113. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I., Lamnisos, D., Syrou, N., & Boustras, G. (2022). Public health and work safety pilot study: Inspection of job risks, burnout syndrome, and job satisfaction of public health inspectors in Greece. Safety Science.

- Adamopoulos, I., Syrou, N., Lamnisos, D., & Boustras, G. (2023). Cross-sectional nationwide study in occupational safety and health: Inspection of job risks, burnout syndrome, and job satisfaction of public health inspectors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Safety Science, 158, 105960.

- Adamopoulos, I., Frantzana, A., & Syrou, N. (2024). Climate Crises Associated with Epidemiological, Environmental, and Ecosystem Effects of a Storm: Flooding, Landslides, and Damage to Urban and Rural Areas (Extreme Weather Events of Storm Daniel in Thessaly, Greece). Medical Sciences Forum, 25(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I., Syrou, N. Climate Change, Air Pollution, African Dust Impacts on Public Health and Sustainability in Europe, European Journal of Public Health, Volume 34, Issue Supplement_3, November 2024, ckae144.1374, . [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I. P., Syrou, N. F., Mijwil, M., Thapa, P., Ali, G., & Dávid, L. D. (2025). Quality of indoor air in educational institutions and adverse public health in Europe: A scoping review. Electronic Journal of General Medicine, 22(2), em632. [CrossRef]

- Amandus, H., Baedlawi, A., Handayani, V. W., Linda, E., Alina, T., & Maria, S. (2024). Determinants of maternal health-seeking behavior for stunted children in Indonesian community health centers: A cross-sectional study. Population Medicine, 6(October), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L. A. D., Veloso, C. F., Souza, M. D. C., Azevedo, J. M. C. D., & Tarro, G. (2021). The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: A systematic review. Jornal de Pediatria, 97, 369-377. [CrossRef]

- Bassuoni, R. A., Mohamed, M. S., Monir, Z. M., & AbdEl-Megeid, A. A. (2021). Relationship between nutritional status and cognitive performance among primary school students. Egyptian Journal of Nutrition, 36(2), 49-87.

- Beckmann, J., Lang, C., du Randt, R., Gresse, A., Long, K. Z., Ludyga, S., ... & Gerber, M. (2021). Prevalence of stunting and relationship between stunting and associated risk factors with academic achievement and cognitive function: A cross-sectional study with South African primary school children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4218. [CrossRef]

- Bustami, B., Suryana, S., Junita, D., Kushargina, R., & Eka, A. (n.d.). The influence of adequate levels of zinc-iron and hemoglobin levels on linear growth and cognitive development in toddlers: A cross-sectional study in Aceh. i-Scientific.org.

- Cardino, V. N., Goeden, T., Yakah, W., Ezeamama, A. E., & Fenton, J. I. (2023). New perspectives on the associations between blood fatty acids, growth parameters, and cognitive development in global child populations. Nutrients, 15(8), 1933. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Liu, C., Liu, X., Wang, Z., Luo, R., Li, S., Yu, Y., & Alderman, H. (2021). Nutrition, cognition, and social emotion among preschoolers in poor, rural areas of South Central China: Status and correlates.

- Chen, S., Luo, S., & Yan, C. (2021). Gut microbiota implications for health and welfare in farm animals: A review. Animals, 11(2), 459. [CrossRef]

- Cohen Kadosh, K., Muhardi, L., Parikh, P., Basso, M., Jan Mohamed, H. J., Prawitasari, T., ... & Geurts, J. M. (2021). Nutritional support of neurodevelopment and cognitive function in infants and young children—An update and novel insights. Nutrients, 13(1), 199. [CrossRef]

- Corona, L. P., Andrade, F. C. D., da Silva Alexandre, T., de Brito, T. R. P., Nunes, D. P., & de Oliveira Duarte, Y. A. (2022). Higher hemoglobin levels are associated with better physical performance among older adults without anemia: A longitudinal analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 233. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Albornoz, M. C., García-Guáqueta, D. P., Velez-van-Meerbeke, A., & Talero-Gutiérrez, C. (2021). Maternal nutrition and neurodevelopment: A scoping review. Nutrients, 13(10), 3530. [CrossRef]

- Costa, H. M., Partanen, P., & Van Herwegen, J. (2021). The role of working memory, processing speed, and approximate number system abilities in low maths achievement among preschoolers.

- Cui, X., McGrath, J. J., Burne, T. H. J., & Eyles, D. W. (2021). Vitamin D and schizophrenia: 20 years on. Molecular Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo, C. S., Sandre, P. C., Portugal, L. C. L., Mázala-de-Oliveira, T., da Silva Chagas, L., Raony, Í., ... & Bomfim, P. O. S. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents' mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 106. [CrossRef]

- Deoni, S. C., Beauchemin, J., Volpe, A., D’Sa, V., & Resonance Consortium. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on early child cognitive development: Initial findings in a longitudinal observational study of child health. MedRxiv.

- Dey, S., Zahangir, M. S., Faruk, M. O., Hossain, S., & Hossain, M. R. (2024). Prevalence and determinants of malnutrition among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 2, 100096.

- Dominic, N., Bhatia, V., Dabadghao, P., & Ansari, M. S. (2024). Long-term outcomes in patients with differences in sex development in Lucknow, India. Clinical Endocrinology.

- Fauziah, N., Aviani, J. K., Agrianfanny, Y. N., & Fatimah, S. N. (2022). Intestinal parasitic infection and nutritional status in children under five years old: A systematic review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 7(11), 371.

- Fouad, H. M., Yousef, A., Afifi, A., Ghandour, A. A., Elshahawy, A., Elkhawass, A., ... & Shalaby, S. (2023). Prevalence of malnutrition & anemia in preschool children: A single-center study. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 49(1), 75.

- Gallegos, D., Eivers, A., Sondergeld, P., & Pattinson, C. (2021). Food insecurity and child development: a state-of-the-art review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 8990. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M., Lang, C., Beckmann, J., du Randt, R., Gall, S., Seelig, H., ... & Walter, C. (2021). How are academic achievement and inhibitory control associated with physical fitness, soil-transmitted helminth infections, food insecurity and stunting among South African primary schoolchildren? BMC Public Health, 21, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Govender, I., Rangiah, S., Kaswa, R., & Nzaumvila, D. (2021). Malnutrition in children under the age of 5 years in a primary health care setting. South African Family Practice, 63(1). [CrossRef]

- Granziera, F., Guzzardi, M. A., & Iozzo, P. (2021). Associations between the Mediterranean diet pattern and weight status and cognitive development in preschool children. Nutrients. [CrossRef]

- Green, C. C., Smith, J., Bent, C. A., Chetcuti, L., Sulek, R., Uljarević, M., & Hudry, K. (2021). Differential predictors of well-being versus mental health among parents of pre-schoolers with autism. Autism, 25(4), 1125-1136. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L., Folch, A., Rojas, M., Cantero, J. L., Atienza, M., Folch, J., ... & Bullo, M. (2021). Effects of nutrition on cognitive function in adults with or without cognitive impairment: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Nutrients, 13(11), 3728. [CrossRef]

- Haan, R., Ali Alblooshi, M. E., Syed, D. H., Dougman, K. K., Al Tunaiji, H., Campos, L. A., & Baltatu, O. C. (2021). Health and well-being of athletes during the coronavirus pandemic: a scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 641392. [CrossRef]

- Howlett, J. R., Nelson, L. D., & Stein, M. B. (2022). Mental health consequences of traumatic brain injury. Biological Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, F. D., Peng, C. F., Adams, D., & Fitriana, N. (2022). A comparative study of children's cognitive ability in Malaysian public and private pre-schools. Journal of Nusantara Studies (JONUS), 7(2), 377-398. [CrossRef]

- Irfani, B., & O'Boyle, A. (). Teacher practices and student preferences of oral corrective feedback in Indonesian EFL classrooms: A Vygotskian perspective. Training.

- Khan, A. J. J., Yar, S., Fayyaz, S., Adamopoulos, I., Syrou, N., & Jahangir, A. (2024). From Pressure to Performance, and Health Risks Control: Occupational Stress Management and Employee Engagement in Higher Education. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Kuzik, N., da Costa, B. G., Hwang, Y., Verswijveren, S. J., Rollo, S., Tremblay, M. S., ... & Saunders, T. J. (2022). School-related sedentary behaviours and indicators of health and well-being among children and youth: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 19(1), 40. [CrossRef]

- Kwansa, A. L., Akparibo, R., Cecil, J. E., Infield Solar, G., & Caton, S. J. (2022). Risk factors for overweight and obesity within the home environment of preschool children in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Nutrients, 14(9), 1706. [CrossRef]

- Lapidot, Y., Maya, M., Reshef, L., Cohen, D., Ornoy, A., Gophna, U., & Muhsen, K. (2023). Relationships of the gut microbiome with cognitive development among healthy school-age children. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 11, 1198792. [CrossRef]

- Łuszczki, E., Jagielski, P., & Martínez-Rodríguez, A. (2023). Metabolic pathways and consequences of malnutrition in children and adolescents. Frontiers in Nutrition. [CrossRef]

- Lynn Terista, S. (2000). Nutrition and student achievement in kindergarten students: an experimental study.

- Mannan Liza, M., Roy, S., Azmain Iktidar, M., Chowdhury, S., & Bin Sharif, A. (2024). Nutritional status, dietary habits, and their relation to cognitive functions: A cross-sectional study among the school-aged (8–14 years) children of Bangladesh.

- Mantey, A. A., Annan, R. A., Lutterodt, H. E., & Twumasi, P. (2021). Iron status predicts cognitive test performance of primary school children from Kumasi, Ghana. PLOS ONE. [CrossRef]

- Mathiarasan, S., & Hüls, A. (2021). Impact of environmental injustice on children’s health—interaction between air pollution and socioeconomic status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 795. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, N. E. and I. (2017). Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. In MoHN & New ERA. [Accessed 12-01-2025] at, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR336/FR336.pdf.

- MoHP. (2022). Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2022 Key Indicators Report. Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu.[Accessed 12-01-2025]at, https://mohp.gov.np/uploads/Resources/Nepal%20Demographic%20and%20Health%20Survey%202022%20Key%20Indicators%20Report.pdf.

- Motokawa, K., Mikami, Y., Shirobe, M., Edahiro, A., Ohara, Y., Iwasaki, M., ... & Hirano, H. (2021). Relationship between chewing ability and nutritional status in Japanese older adults: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1216. [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli, M. (2021). The impact of nutrients on mental health and well-being: insights from the literature. Frontiers in Nutrition. [CrossRef]

- Mwadiwa, R. J., Kearney, J. E., & Napier, C. (2016). Determining nutritional status and food intake patterns of preschool children in Empangeni, South Africa.

- N Santos, D., Marlúcia O Assis, A., Cecília S Bastos, A., M Santos, L., Antonio ST Santos, C., Strina, A., S Prado, M., M Almeida-Filho, N., C Rodrigues, L., & L Barreto, M. (2008). Determinants of cognitive function in childhood: A cohort study in a middle-income context.

- Nyaradi, A., Li, J., Hickling, S., Foster, J., & Oddy, W. (2013). The role of nutrition in children’s neurocognitive development, from pregnancy through childhood. [CrossRef]

- Padhi, B. K., Gaidhane, A. M., Satapathy, P., Bushi, G., Ballal, S., Bansal, P., ... & Shabil, M. (2024). Assessing the impact of ecological, climatic, and socioeconomic factors on age-specific malaria incidence in India: a mixed-model approach using the Global Burden of Disease Study (2010–2019). Malaria Journal, 23(1), 332. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H. (1991). Impact of preschool education component in integrated child development services programme on the cognitive development of children. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 37(5), 235–239. [CrossRef]

- Pomati, M., Mendoza-Quispe, D., Anza-Ramirez, C., Hernández-Vásquez, A., Carrillo Larco, R. M., Fernandez, G., ... & Bernabé-Ortiz, A. (2021). Trends and patterns of the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) in Peru: A pooled analysis of 129,159 mother-child dyads. International Journal of Obesity, 45(3), 609-618. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D. P. & Lovegrove, J. A. (2021). Nutritional status of micronutrients as a possible and modifiable risk factor for COVID-19: A UK perspective. British Journal of Nutrition. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M., Tolar-Peterson, T., Reynolds, A., Wall, C., Reeder, N., & Rico Mendez, G. (2022). The effects of nutritional interventions on the cognitive development of preschool-age children: A systematic review. Nutrients, 14(3), 532. [CrossRef]

- Said, W. P., Arto, K. S., Pratita, W., & Sufitni, S. (2023). Intelligence quotient (IQ) outcome in children with early-treated congenital hypothyroidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Paediatrica Indonesiana, 63(4), 290-7. [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A. J. & Seifer, R. (2021). Accumulation of environmental risk and child mental health. Children of Poverty.

- Santander Ballestín, S., Giménez Campos, M. I., Ballestin Ballestin, J., & Luesma Bartolomé, M. J. (2021). Is supplementation with micronutrients still necessary during pregnancy? A review. Nutrients, 13(9), 3134. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. (2022). Nutritional practices of the preschool-aged children and associated factors: A cross-sectional study in Rupandehi district of Nepal. Journal of Health Promotion, 10(1), 59–72. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. (2023). Effect of Nutrition and Psychosocial Stimulation on Cognitive Development of Preschool Children in Nepal. Unpublished PhD thesis, Faculty of Education, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Sharma, P., & Budhathoki, C. B. (2023). Effects of Primary Caregivers’ Feeding Habits on the Nutrition Status of Pre-schoolers in Rupandehi District of Nepal. Journal of Health Promotion, 11(1), 86–103. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Bahadur Budhathoki, C., Devkota, B., & Kumar Singh, J. (2024). Healthy eating encouragement and socio-demographic factors associated with cognitive development among pre-schoolers: a cross-sectional evaluation in Nepal.

- Sharma, P., Budhathoki, C. B., Devkota, B., & Singh, J. K. (2024). Healthy eating encouragement and socio-demographic factors associated with cognitive development among pre-schoolers: A cross-sectional evaluation in Nepal. European Journal of Public Health, 34(2), 230-236. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Budhathoki, C. B., Maharjan, R. K., & Singh, J. K. (2023). Nutritional status and psychosocial stimulation associated with cognitive development in preschool children: A cross-sectional study at Western Terai, Nepal. PLOS ONE, 18(3), e0280032. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Budhathoki, C. B., Maharjan, R. K., Devkota, B., Upreti, Y. R., Bhandari, T. R., & Tulsi, R. B. (2022). Nutrition status and associated factors among preschool children: A cross-sectional study in Nepal. International Journal of Elementary Education, 11(3), 76–83.

- Sharma, P., Budhathoki, C.B. & Thapa, P. (2024). Factors associated with psychosocial stimulation development of preschool children in Rupandehi District of Nepal. KMC Journal, 6(1), 241–259.

- Siagian, F. E. (2023). Role of intestinal parasitic infection in stunting. South Asian Journal of Research in Microbiology.

- Soliman, A., De Sanctis, V., Alaaraj, N., Ahmed, S., Alyafei, F., Hamed, N., & Soliman, N. (2021). Early and long-term consequences of nutritional stunting: From childhood to adulthood. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 92(1).

- Strauß, H., Venables, P., & Zentner, M. (2023). Associations between early childhood poverty and cognitive functioning throughout childhood and adolescence: A 14-year prospective longitudinal analysis of the …. PLOS ONE.

- Tandoh, M. A., Appiah, A. O., & Edusei, A. K. (2021). Prevalence of anemia and undernutrition of adolescent females in selected schools in Ghana. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2021(1), 6684839.

- Tsan, L., Décarie-Spain, L., Noble, E. E., & Kanoski, S. E. (2021). Western diet consumption during development: Setting the stage for neurocognitive dysfunction. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15, 632312. [CrossRef]

- Vassilakou, T. (2021). Childhood malnutrition: Time for action. Children, 8(10), 849. [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. (2009). An Introductory Analysis. In HARPER & ROW, NEW YORK, EVANSTON & LONDON AND JOHN WEATHERHILL, INC., TOKYO. [CrossRef]

- Zavitsanou, A., & Drigas, A. (2021). Nutrition in mental and physical health. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 19, 226-239.

- Zemene, M. A., Anley, D. T., Gebeyehu, N. A., Adella, G. A., Kassie, G. A., Mengstie, M. A., ... & Dessie, A. M. (2023). Concurrent stunting and overweight or obesity among under-five children in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel analysis. Archives of Public Health, 81(1), 119. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | N (%) | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender of children |

Male Female |

192 (50.7) 187 (49.3) |

101.65 (15.14) 102.29 (15.56) |

-3.73/2.46 -3.74/2.46 |

.686 |

| Age of children |

Three years Four years Five years |

33 (8.7) 171 (45.1) 175 (46.2) |

109.57 (21.61) 101.56 (12.73) 100.93 (15.95) |

101.91/117.24 99.64/103.48 98.55/103.31 |

.011* |

| Number of children |

Two or less More than two |

271(71.5) 108 (28.5) |

102.63 (15.27) 100.34 (15.43) |

-1.15/5.70 -1.17/5.73 |

.192 |

| Types of family |

Nuclear Joint |

180 (47.5) 199 (52.5) |

103.83 (14.23) 100.28 (16.12) |

0.47/6.64 0.49/6.62 |

.024* |

| Mothers’ education |

Illiterate Basic level Secondary and above |

90 (23.7) 175 (46.2) 114 (30.1) |

99.64 (13.69) 100.46 (15.78) 106.12 (15.17) |

96.77/102.51 98.10/102.81 103.30/108.93 |

.002** |

| Fathers’ education |

Illiterate Basic level Secondary and above |

58 (14.3) 188 (49.6) 133 (35.1) |

100.13 (13.46) 100.41(15.18) 104.96 (15.96) |

96.59/103.67 98.22/102.59 102.23/107.70 |

.019* |

| Wealth status |

Poorest Poor Middle Rich Richest |

73 (19.3) 72 (19.0) 79 (20.8) 74 (19.5) 81(21.4) |

102.69 (17.95) 105.06 (15.50) 102.49 (14.16) 99.62 (14.98) 100.19 (13.77) |

98.51/106.88 101.42/108.71 99.32/105.66 96.14/103.09 97.15/103.24 |

.198 |

| HAZ |

Normal Moderate Severe (Stunted) Obese |

169 (44.6) 138 (36.4) 57 (15.0) 15 (4.0) |

105.38 (15.43) 101.68 (15.34) 96.08 (11.88) 88.46 (12.05) |

103.04/107.72 99.10/104.27 92.93/99.24 81.78/95.14 |

.0001*** |

| WAZ |

Normal Moderate Severe (Wasted) Obese |

175 (46.2) 135 (35.6) 58 (15.3) 11 (2.9) |

102.70 (15.23) 103.11(15.96) 97.84 (14.79) 98.09 (7.13) |

100.42/104.97 100.39/105.82 93.95/101.73 93.29/102.88 |

.109 |

| Total | 379 (100) |

| Variables | Category | WAZ | HAZ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 95% CI | P-value | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Gender of children |

Male Female |

-0.98 (1.06) -0.99 (1.14) |

-0.21/0.23 -0.21/0.23 |

.916 | -0.97 (1.11) -1.06 (1.18) |

-0.14/0.31 -0.14/0.31 |

.476 |

| Age of children |

Three years Four years Five years |

-0.92 (1.15) -1.02 (1.16) -1.03 (1.13) |

-1.32/-0.51 -1.20/-0.85 -1.20/-0.86 |

.870 | -0.92 (1.15) -1.02 (1.16) -1.03 (1.13) |

-1.32/-0.51 -1.20/-0.85 -1.20/-0.86 |

.870 |

| Number of children |

Two or less More than two |

-0.85 (1.06) -1.31(1.12) |

0.21/0.69 0.20/0.70 |

.000 *** |

-0.95 (1.09) -1.18 (1.26) |

-0.02/0.49 -0.04/0.50 |

.073 |

| Types of family |

Nuclear Joint |

-0.89 (1.07) -1.06 (1.12) |

-0.05/0.39 -0.05/0.39 |

.134 | -0.92 (1.08) -1.11(1.20) |

-0.04/0.42 -0.04/0.41 |

.111 |

| Mothers’ education |

Illiterate Basic level Secondary+ |

-1.12 (1.26) -1.00 (1.08) -0.95 (1.15) |

-1.39/-0.86 -1.17/-0.84 -1.17/-0.74 |

.574 | -1.12 (1.26) -1.00 (1.08) -0.95 (1.15) |

-1.39/-0.86 -1.17/-0.84 -1.17/-0.74 |

.574 |

| Fathers’ education |

Illiterate Basic level Secondary + |

-0.86 (1.13) -1.04 (1.14) -1.06 (1.17) |

-1.16/-0.56 -1.20/-0.87 -1.26/-0.85 |

.517 | -0.86 (1.13) -1.04 (1.14) -1.06 (1.17) |

-1.16/-0.56 -1.20/-0.87 -1.26/-0.85 |

.517 |

| Wealth status |

Poorest Poor Middle Rich Richest |

-0.80 (1.05) -0.84 (1.03) -0.93 (1.16) -0.91(1.10) -1.54 (1.22) |

-1.04/-0.55 -1.09/-0.60 -1.19/-0.67 -1.17/-0.66 -1.81/-1.27 |

.0001 *** |

-0.80 (1.05) -0.84 (1.03) -0.93 (1.16) -0.91(1.10) -1.54 (1.22) |

-1.04/-0.55 -1.09/-0.60 -1.19/-0.67 -1.17/-0.66 -1.81/-1.27 |

.0001 *** |

| Predictors | Standardized Coefficients β (95 % CI) Model I |

p-value | Standardize Coefficients β (95 % CI) Model II |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of child | -0.021 (-0.218/ 0.141) | 0.675 | -0.105 (-0.348/ -0.014) | 0.034 |

| Joint family | -0.09 (-0.437/ 0.023) | 0.078 | -0.089 (-0.409/0.018) | 0.073 |

| Mother's illiteracy | -0.069 (-0.482/0.11) | 0.217 | 0.007 (-0.255/0.294) | 0.891 |

| Father’s Illiteracy | -0.011 (-0.265/ 0.213) | 0.831 | 0.006 (-0.207/0.236) | 0.896 |

| Wealth status | 0.258 (0.205/0.505) | 0.0001*** | 0.318 (0.28/0.559) | 0.0001 *** |

| R Square | 6.4% | 12.4% | ||

| Std. Error | 1.12 | 1.03 | ||

| F (P-value) | 5.067 | 0.0001 *** |

10.547 | 0.0001 *** |

| Predictors | Standardized Coefficients β (95 % CI) Model I |

p-value | Standardize Coefficients β (95 % CI) Model II |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of child | -0.131(-5.576/-0.726) | 0.011* | -0.141(-5.736/-1.036) | 0.005** |

| Joint family | -0.131 (-7.121/-0.914) | 0.011* | -0.112 (-6.431/-0.440) | 0.025* |

| Mother's illiteracy | 0.028 (-2.997/4.990) | 0.624 | 0.055 (-1.867/5.839) | 0.311 |

| Father’s Illiteracy | 0.031(-2.221/4.223) | 0.542 | 0.036 (-1.928/4.263) | 0.459 |

| Wealth status | 0.087 (-0.434/3.620) | 0.123 | 0.043 (-1.247/2.828) | 0.446 |

| HAZ | 0.38 (3.235/6.896) | 0.0001*** | ||

| WAZ | -0.171(-4.348/-0.401) | 0.018* | ||

| R Square | 4.3% | 12.2% | ||

| Std. Error | 15.10 | 14.50 | ||

| F (P-value) | 3.358 | 0.006** | 77.376 | 0.0001*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).