Background

Public health is concerned with the social conditions and determinants of sickness and how society defines and addresses such conditions. Maternal health is a significant factor in the cognitive development of a preschool child [

1]. Preschool children’s cognitive development influences their preparation to begin school, and the quality of public education influences state and national social and economic issues [

2] and public health. The emerging medical health literature considers maternal health in the context of public health [

3].

The physical and emotional health of mothers, which has an impact on a fragile and dependent child, is of public importance. Research has demonstrated that early disadvantages frequently lead to childhood disease and developmental issues [

4]. A young child who is ill or inadequately nurtured is often fussy, angry, and weeping, and many people struggle with childrearing [

5]. For childrearing to be most community-optimal, the child requires developmental-stage-appropriate care [

6]. An increasingly rigorous empirical literature has demonstrated that maternal behaviors can harm child development [

7]. Future avenues of inquiry will help inform society, policy, and services about what influences a mother and whether there are additional reasons for extra community assistance [

8], as well as public health and maternal factors of concern [

9].

Public health research seeks to identify elements within the social ecology model that can enhance people’s lives; nevertheless, the effects of public health and social determinants on mothers are frequently researched separately from the children they bring into the world and raise [

10]. The conceptual framework is crucial for understanding how women’s socioecological context influences preconception, pregnancy, nursing, and health outcomes [

11].

Public health has a significant impact on maternal characteristics connected to nurturance and, as a result, the cognitive development of preschool children, with implications for policies and programs aimed at improving early children’s health [

12]. Scholars have undertaken the majority of research in this area to compare women’s health behaviors, health state, access to care, health status, and care utilization among low-income mothers [

13]. There is a need to do more to promote others’ health, and this strategy should prioritize community-based services and family support [

14].

Early childhood is a critical period for cognitive development, laying the foundation for lifelong learning and well-being [

15]. Research indicates that the academic nurturance provided during this stage significantly influences children’s cognitive, social, and emotional growth. Academic nurturance, encompassing the emotional, instructional, and material support provided to young learners, plays a vital role in shaping their cognitive abilities, problem-solving skills, and readiness for formal education [

16].

In Nepal, particularly in the Rupandehi District, the role of academic nurture in preschool settings has garnered increasing attention. Understanding the interplay between nurturing environments and cognitive development becomes imperative as the country progresses toward enhancing early childhood education. Despite national efforts to expand early childhood education programs, disparities in access, quality of instruction, and caregiver involvement persist, potentially affecting children’s developmental outcomes.

Rupandehi District, known for its diverse population and socioeconomic variability, presents a unique setting for exploring how academic nurturance impacts preschool children’s cognitive development. Many children in the district experience varying levels of educational stimulation, which may be correlated with parental education, teacher training, and the availability of learning resources.

This study investigates the relationship between academic nurturance and the cognitive development of preschool children in Rupandehi District. By identifying key factors that contribute to or hinder cognitive growth, this research seeks to provide insights for educators, policymakers, and caregivers to foster enriched learning environments for early childhood development. This study aimed to understand better the intricate interactions among public health variables, socioeconomic determinants, and maternal nurturance to understand their involvement in cognitive development impairment in infants.

The study is expected to produce empirical findings that will be helpful to policymakers and public health professionals working in early childhood mental development, programs for women’s health, and maternal care at local county health departments.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

The study utilized a cross-sectional descriptive survey design, targeting primary caregivers of preschool-aged children as participants. Data collection was conducted between 4 February and 12 April 2021, across Rupandehi District, Nepal, from 14,358 children in government-operated early childhood development (ECD) centers, reflecting a rich tapestry of ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic diversity [

15,

16].

The sample size was calculated via Yamane’s formula [

17].

Where ‘n’ represents the sample population, N= total population, and ‘e’ = 5% allowable error. This calculation yielded a sample of 389 children.

The sampling process followed a multistage approach to ensure representativeness and rigor. Initially, three local administrative units were randomly selected from distinct strata, encompassing a sub-metropolitan city, a municipality, and a rural municipality, to capture diverse geographic and socioeconomic contexts. The selected local units obtained comprehensive records of schools and Early Childhood Development (ECD) centers in the subsequent phase. A simple random sampling (lottery technique) was applied to draw five ECD centers from each local unit. In the final stage, the Population Proportionate Sampling (PPS) technique was utilized to allocate participants, resulting in a sample of 389 primary caregivers of preschool-aged children. If a primary caregiver was unavailable or unable to provide necessary information, a close family member was consulted as an alternative respondent. The study exclusively included caregivers who accompanied their preschool children to the respective ECD centers or schools during the data collection period. Participants who were unwilling to respond or provide data were excluded, along with ECD centers and schools that participated in pretesting the research instruments to minimize bias in the final analysis [

18]. This research was carried out on the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical approval, and consent to caried out for the study was secured from the Board of Ethical Review at the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC: No. 2078-56/2021), following prior authorization from the Office of the Dean, Faculty of Education, Tribhuvan University.

Data Collection

Data collection was conducted via a self-administered questionnaire with two sections. Section A examined how caregivers actively support emotional and cognitive development through their academic nurturance practices. It highlighted specific behaviors caregivers use to foster growth in these areas. The questionnaire included a series of questions to evaluate the extent of caregivers’ involvement in stimulating their children’s learning. For example, caregivers were asked how often they or someone else read stories to their child in a week, with response options ranging from 2–5 times to 0–1 times.

Caregivers were also asked whether they asked questions about the stories they read to their child and how many children’s books they owned, with responses indicating two or more books or none. Additional questions addressed whether caregivers or others taught their children about numbers, the alphabet, colors, shapes, and sizes. Furthermore, caregivers were asked if they discussed TV or YouTube programs with their child while watching and how often a family member took the child outings, with options ranging from 2-5 times per month to none. Finally, caregivers were asked how often a family member took the child to a museum in a year, with responses indicating 2–5 times or none [

19]. Each question was scored as 1 for a“yes” answer and 0 for a “n” answer [

20].

This structured tool provides a detailed assessment of caregivers’ involvement in cognitive stimulation, aiming to understand their role in fostering academic nurturance. In addition, Section A included socioeconomic variables such as the child’s gender and age, family structure, caste/ethnicity, maternal education level, and family economic standing, recognizing these factors as potential determinants of cognitive and academic development. Financial status was measured via the 2016 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) tool, which evaluated household assets and living conditions [

21]. Based on specific score ranges, wealth scores were then classified into quartiles—poorest, poor, rich, and richest [

22]. These socioeconomic factors were included to account for their possible influence on the developmental outcomes of the children in the study.

Researchers measured cognitive development in Section B using a standardized tool designed by the National Psychological Corporation of India based on Piaget’s theory of developmental psychology [

23].

This instrument, designed for assessing children aged 3 to 5 years in the preoperational stage, converts raw scores into age-specific standard scores and includes tasks focused on symbolic play and basic problem-solving skills. To ensure the tool’s clarity, relevance, and cultural suitability, a pilot test was conducted with 10% of the sample, leading to minor revisions based on participant feedback to improve contextual accuracy. The reliability of the cognitive development tool was confirmed, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, whereas the academic nurturing tool had an alpha of 0.80.

All the participants agreed and gave their approval and consent to participate in the study and confirm the use of the questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before conducted and used the questionaire and assigned each participant an identification number (ID) which was included in the transcripts field notes,and data analyzing from statistical software SPSS v, 26.

Data Analysis

The data were meticulously entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed via IBM SPSS version 26 to ensure robust statistical examination. Descriptive statistics were calculated for continuous and categorical variables, including means and standard deviations and frequencies for the former. To facilitate group comparisons, independent sample t-tests and ANOVA were employed, with a threshold of p < 0.05 set for statistical significance.

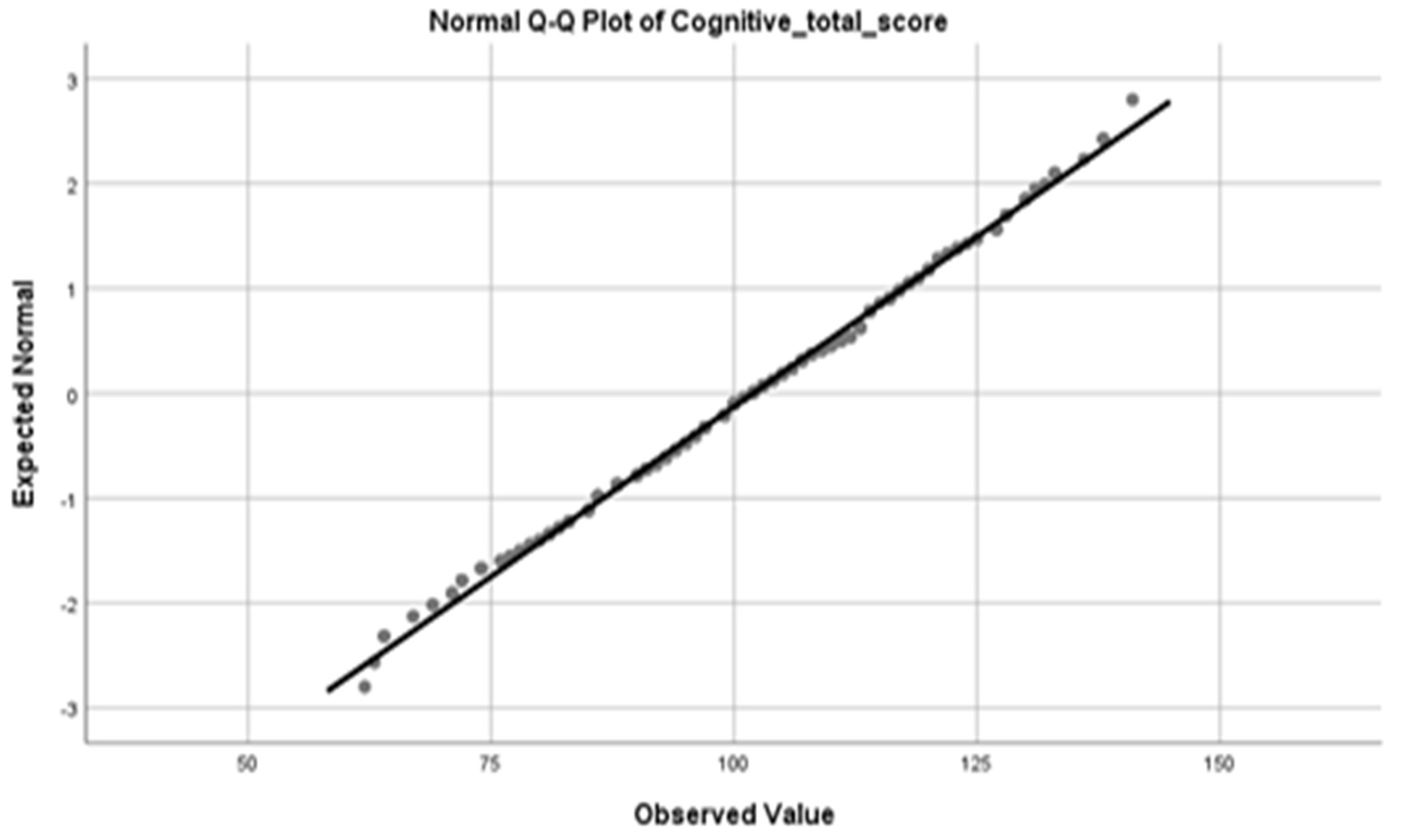

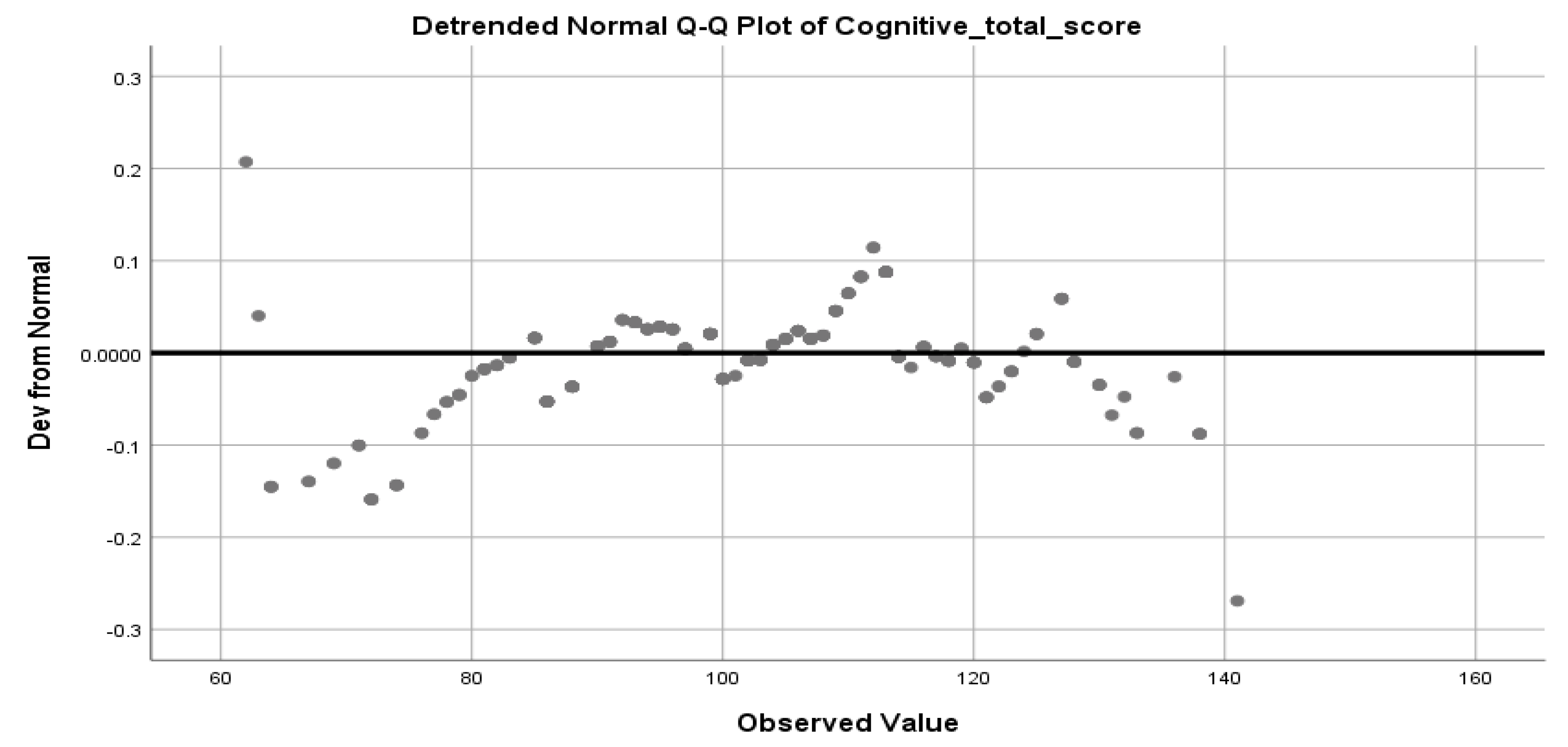

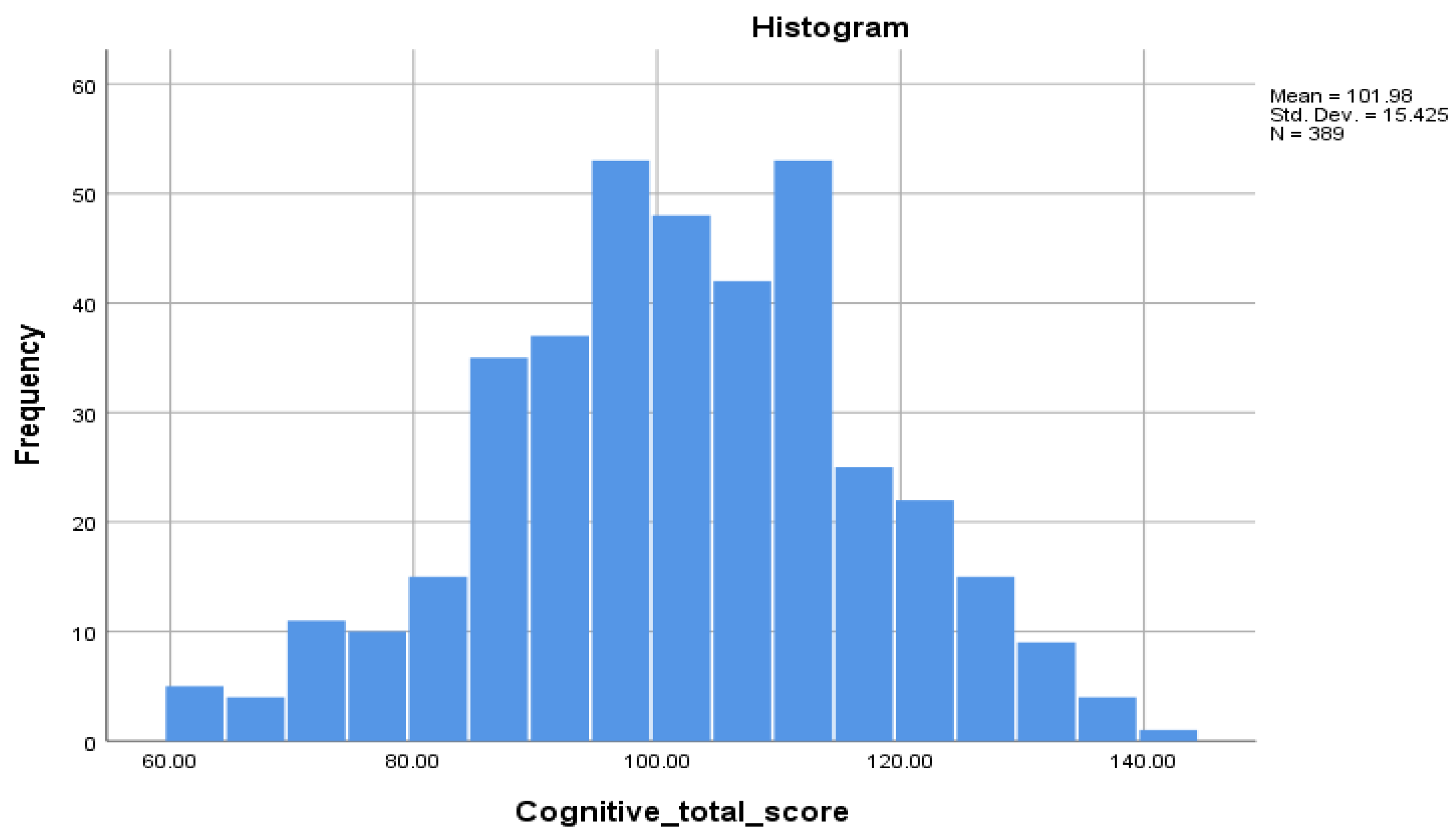

The normality of the data distribution and thorough screening for outliers were performed, leading to a refined dataset of 389 valid cases.

Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to identify key factors influencing cognitive development.

This analysis controlled for potential confounding variables to isolate significant predictors, providing a more accurate understanding of the relationships between variables. Additionally, the use of rigorous statistical techniques ensured the reliability and validity of the results, offering a comprehensive exploration of the determinants of cognitive development in the study population.

Figure 1 shows the normal Q‒Q plot diagram of the total cognitive score values of the study.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The study sample included N=389 children, with 50.6% male and 49.4% female participants. The age distribution revealed that 8.7% were three years old, whereas the majority were four (45.8%) or five (45.5%). Most families (72%) had two or fewer children. Regarding family structure, 52.4% lived in joint families, whereas 47.6% were part of nuclear households. Caste and ethnicity data indicated that 13.1% of the respondents were from the Dalit community, whereas 35.2% were from the advantageous caste. Educational background revealed that 23.4% of mothers were illiterate, whereas 8% had attained higher education. Regarding economic status, 24.7% of the respondents were categorized as the poorest and 20.8% as the richest (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Determinants of Academic Nurturance

Table 1 illustrates the analysis of academic nurturance scores across various demographic variables. The findings highlight significant variations in mean nurturance scores based on critical factors. Notably, the number of children in the family (p=0.0001), caste (p=0.0001), mothers’ education level (p=0.0001), and wealth status (p=0.0001) were strongly associated with differences in nurturance outcomes.

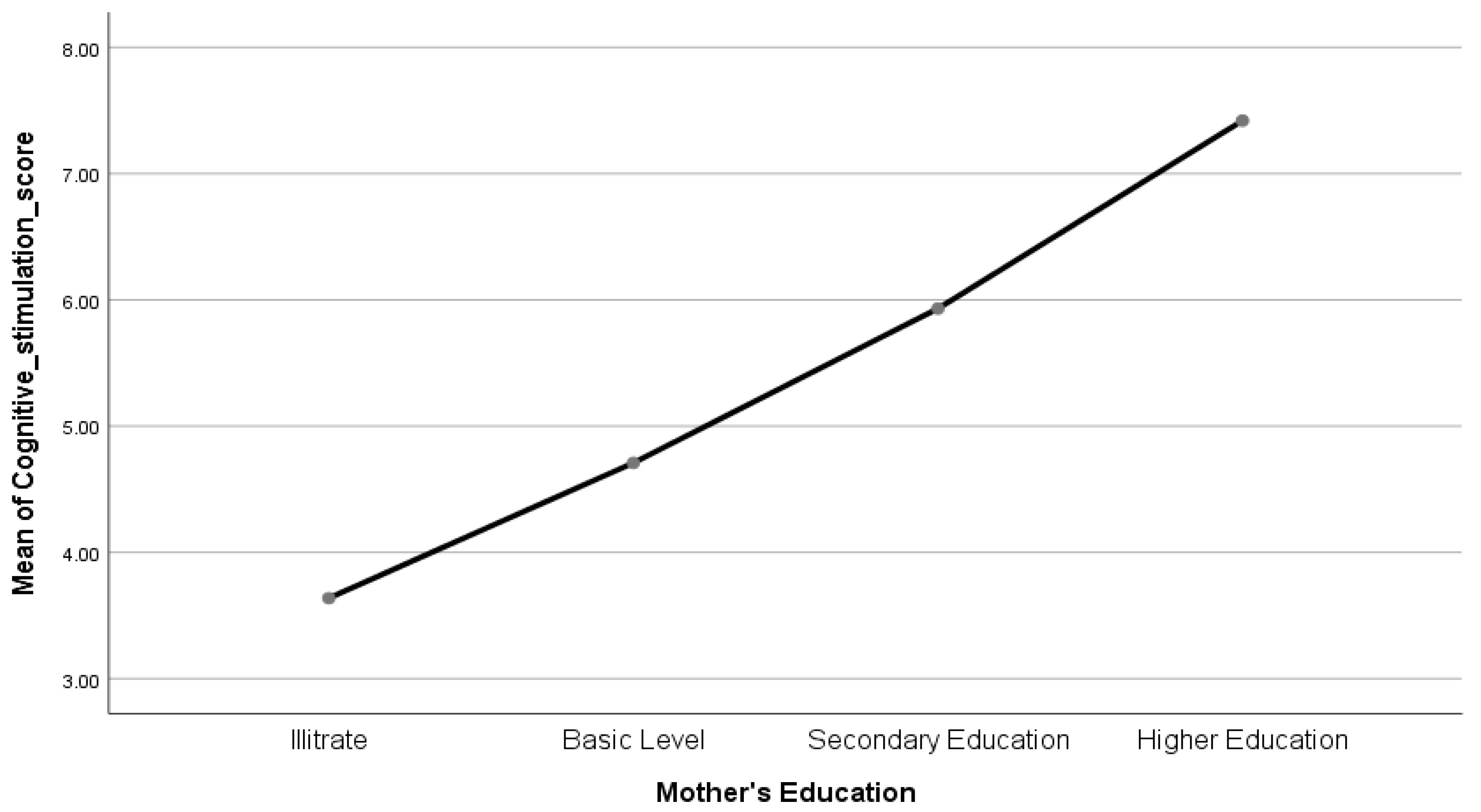

Children from families with two or fewer children presented higher nurturance scores (M=5.28, SD=2.15) than those from larger families (M=4.01, SD=2.36). Similarly, children from the advantageous caste had significantly greater nurturance (M=6.00, SD=2.05) than Dalit children (M=3.88, SD=1.99). Maternal education showed a progressive increase in scores, with children of mothers with higher education achieving the highest nurturance (M=7.41, SD=1.76) compared with those whose mothers were illiterate (M=3.63, SD=2.21).

Wealth status also demonstrated a positive trend, where children from the wealthiest families had the highest nurturance scores (M=6.27, SD=1.66) compared with children from the poorest households (M=3.08, SD=2.08). However, no significant differences were observed in nurturance scores based on gender (p=0.819), age (p=0.623), or family structure (p=0.383).

Determinants of Cognitive Development

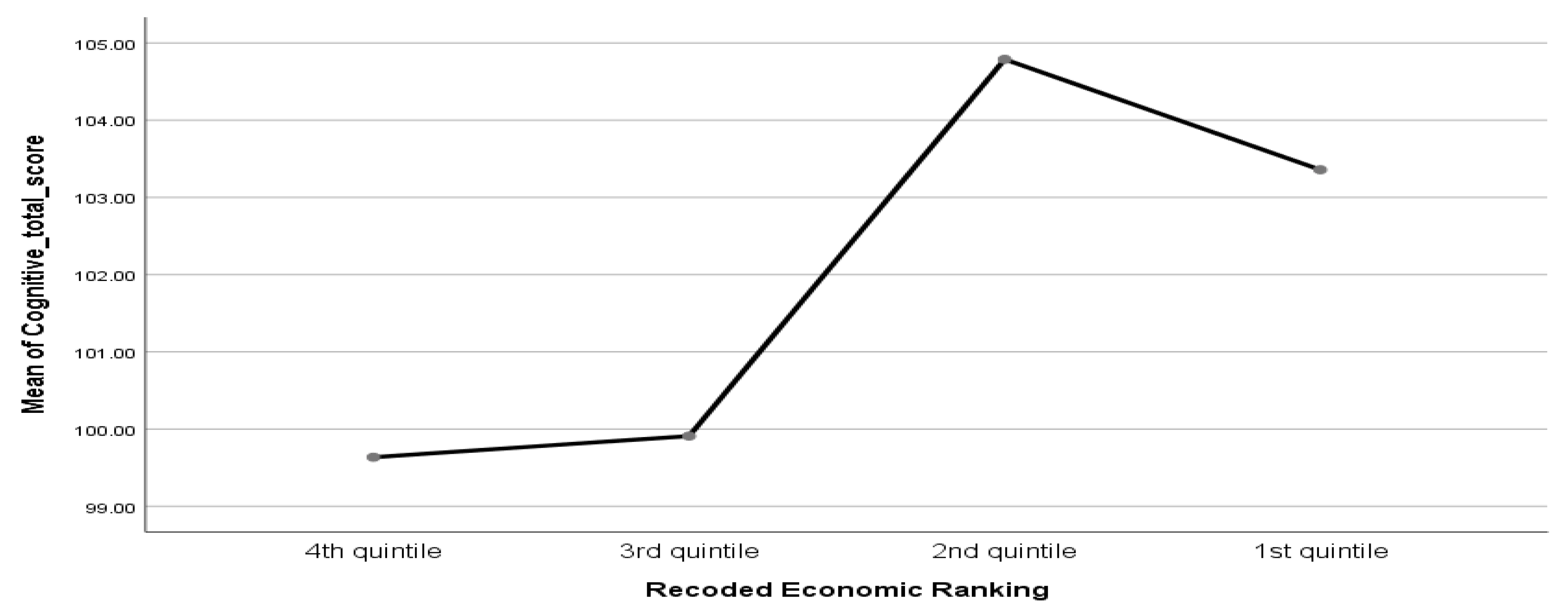

Table 2 analyzes the cognitive development scores across various demographic variables. There was no statistically significant difference in cognitive development between male (M=101.74, SD=15.35) and female children (M=102.21, SD=15.52), with a p-value of 0.766. This suggests that gender does not play a significant role in determining cognitive development within the sample population. Age was significantly associated with cognitive development (p=0.016). Children aged three years had the highest mean cognitive scores (M=108.94, SD=21.60), followed by four-year-olds (M=101.92, SD=12.93) and five-year-olds (M=100.68, SD=16.05). The number of children in the family did not significantly impact cognitive development (p=0.278). Children from families with two or fewer children had slightly higher scores (M=102.50, SD=15.36) than those from larger families (M=100.61, SD=15.57), but the difference was not statistically significant. A significant difference in cognitive development was observed between children from nuclear and joint families (p=0.013). Children from nuclear families presented higher cognitive scores (M=104.00, SD=14.33) than those from joint families (M=100.13, SD=16.16). Caste/ethnicity was highly significantly associated with cognitive development (p=0.0001). Children from advantageous castes had the highest cognitive scores (M=107.68, SD=14.57), whereas Dalit children recorded the lowest mean scores (M=99.49, SD=15.13). Janajati and non-Dalit Tarai caste children had intermediate scores (M=98.41, SD=14.72 and M=99.07, SD=15.42, respectively). Maternal education was significantly associated with cognitive development (p=0.002). Children of mothers with higher education levels achieved the highest cognitive scores (M=109.12, SD=16.19), whereas children whose mothers were illiterate recorded the lowest scores (M=99.79, SD=13.68). Wealth status had a significant effect on cognitive development (p=0.038). Children from the wealthiest families had higher cognitive scores (M=103.35, SD=17.75) than those from the poorest households did (M=99.63, SD=14.12).

The Dalit caste holds the lowest social status, often associated with untouchability. Janajati and non-Dalit Tarai castes rank above Dalits but below advantaged castes in the social hierarchy in Nepal [

24].

Figure 2 shows the Diagram of the Detrended Normal Q-QPlot of cognitive total score.

Multiple Regression Analysis: Predictors of Cognitive Development

Table 3 presents the results of multiple regression models that examine the relationships between various predictors and cognitive development. The analysis is split into two models: Model 1 assesses the impact of socioeconomic factors on cognitive development, whereas Model 2 incorporates both socioeconomic factors and academic nurturance.

In Model 1, economic status is a significant predictor of cognitive development (β = -0.254, p = 0.000), with a negative association indicating that lower economic status is linked to poorer cognitive development. Conversely, advantageous caste was also a significant predictor, with a negative coefficient (β = -0.147, p = 0.004), suggesting that children from advantageous caste backgrounds had lower cognitive development scores. The number of children in the family and mothers’ illiteracy did not significantly affect cognitive development (p > 0.05). The model explains 8.2% of the variance in cognitive development (R² = 8.2%), with an F statistic of 5.608 (p = 0.000).

In Model 2, when academic nurturance was added as a predictor, it did not have a significant effect (β = -0.003, p = 0.954). However, family structure was a significant predictor, as children from joint families presented significantly lower cognitive development scores (β = -0.148, p = 0.004). The child’s age also had a marginally significant negative effect (β = -0.107, p = 0.035), suggesting that older children may experience different developmental trajectories. Advantageous caste, which was significant in Model 1, remained a significant predictor of cognitive development in this model (β = 0.195, p = 0.000). The model explains 8.0% of the variance in cognitive development (R² = 8.0%), with an F statistic of 4.667 (p = 0.000).

Figure 3 shows the Histogram of the study’s frequency and cognitive total score correlations.

Model-I: Academic nurturance score adjusted for socioeconomic factors

Model-II: Cognitive development score adjusted for socioeconomic factors and the academic nurturance index.

Table 4 shows the Cognitive total score of the quintiles confidence interval means.

Figure 4.

Cognitive total scores of the study recorded for economic ranking.

Figure 4.

Cognitive total scores of the study recorded for economic ranking.

Figure 5 shows the classifications of Mothers’ education mean values of cognitive stimulation scores.

Discussion and Findings of the Research

Public health focuses on lifespan, highlighting mothers’ health’s importance in the well-being of preschool-aged children [

25]. Healthcare disparities between affluent and underprivileged women persist, influenced by cultural practices and beliefs [

26]. Women from diverse backgrounds, including African American women, face barriers to timely prenatal care [

27,

28]. Despite public health initiatives improving access, disadvantaged sociodemographic groups still lack access to these services [

29,

30].

The findings from the Tables show that children from families with two or fewer children had significantly higher nurturance scores than those from larger families. Compared with Dalit children, children from the advantageous caste had higher nurturance scores. Maternal education level showed a progressive increase in academic nurturance scores. Wealth status also had a significant effect, with children from the wealthiest families having the highest nurturance scores, supported by the global literature.

Children’s brain volume expands during the early years of life, affecting their cognitive and language skills [

31]. Early interactions with mothers and exposure to richer language, mainly nonverbal vocabulary, contribute to cognitive development [

32]. Even slight variations in maternal care can significantly impact cognitive growth until adolescence, and interactions with mothers are particularly significant [

33]. The richer mental states significantly correlate with enhanced cognitive growth in children, especially regarding their nonverbal vocabulary related to understanding a wide range of emotions [

34].

The findings from the study tables show that age was significantly associated with cognitive development. Three-year-old children presented the highest cognitive scores, whereas five-year-olds presented slightly lower scores, which suggests that cognitive advantages may diminish slightly with age in the sample. Children from nuclear families achieved higher cognitive scores than those from joint families. Significant differences in cognitive development were evident across caste groups. Children from advantageous castes recorded the highest cognitive scores, whereas Dalit children scored the lowest. Maternal education levels were significantly associated with cognitive development. Compared with children of illiterate mothers, children of mothers with higher education levels had superior cognitive outcomes. Economic status influences cognitive development. Children from the wealthiest families presented higher cognitive scores than those from the poorest families, which aligns with the findings of the global literature.

Public health interventions have a restricted effect on the factors that contribute to maternal nurturing among the various social determinants; only maternal mental health was identified as having a significant influence on positive outcomes, highlighted in the key findings from the regression analyses [

33,

35]. The discussion centers on how sociodemographic factors can positively or negatively affect maternal nurturance and cognitive development [

36]. This is accompanied by tables summarizing the significant determinants identified through different analytical models (1 and 2). Additionally, the results section examines other factors affecting maternal cognitive development.

The findings from the multiple regression analysis (

Table 3) and Model 1 show that the analysis of socioeconomic factors as predictors of academic nurturance revealed that economic status was a significant negative predictor, with lower economic status being linked to poorer academic nurturance. Additionally, caste was significant, with children from disadvantageous caste backgrounds having lower academic nurturance scores. The findings from Model 2 concerning family structure became a significant predictor, with children from joint families exhibiting lower cognitive development scores.

Age had a marginally significant negative impact, indicating that their cognitive development slightly decreased as children grew old. This could be attributed to the tendency for caregivers to provide less nurturing as children grow old, often redirecting attention and resources toward younger siblings. Additionally, older children may assume more care for younger family members, which could reduce the time and energy available for their cognitive development [

23]. Advantageous caste remains a significant predictor of cognitive development. The findings from Model Explanation are that the models explained 8.2% (Model 1) and 8.0% (Model 2) of the variance in cognitive development, with both models having significant F-statistics (p=0.000), the above supported with the global literature. One of the critical insights from the literature is the notion that socioeconomic status significantly influences dietary behaviors and health outcomes. Families with lower socioeconomic status face more significant challenges in adopting health-promoting behaviors, which can lead to a higher incidence of chronic non-communicable diseases among their children [

38]. This connection emphasizes the need for targeted interventions that promote healthy eating and address the socioeconomic barriers that hinder access to nurturance [

39]. The critical role of maternal involvement in child development frames it within the broader context of social determinants such as socioeconomic status and mental health [

40]. Effective maternal‒child communication is identified as essential for optimal developmental outcomes, with a lack of engagement leading to delays in cognitive and emotional growth [

41]. The impact of public health inequities that manifest early in life points to factors and social deprivation that adversely affect maternal well-being and child development [

42]. Additionally, the implications of maternal mental health for child development are addressed, emphasizing that maternal anxiety and depression can severely hinder a mother’s ability to provide adequate care, thereby compromising the child’s developmental trajectory [

43]. Ultimately, a crucial aspect of the impact of public health and social determinants on maternal factors for academic nurturance and ethical considerations involves addressing the cognitive development of preschool children, preventing burnout syndrome, increasing job satisfaction [

44,

45], and reducing occupational stress, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, [

46,

47] and the ongoing climate crisis in teaching staff and caregivers [

48,

49]. Effective training, education, and competent management of healthcare and public health services are essential [

50,

51] for ensuring the quality of hospital care and public health initiatives supported by strategic policy interventions [

52,

53,

54,

55].

Implications for Practice

This study contributes to maternal and child health by informing clinical and public health practices throughout life and highlighting the connection between maternal nurturance and cognitive development in preschool children. The results will pave the way for future longitudinal studies, necessitating a more thorough exploration and refinement of the elements in the proposed model. The findings will guide future research directions and inform program development and implementation. This study underscores interventions’ crucial role in enhancing maternal health and well-being, fostering more nurturing environments. First, increasing and diversifying resources for public health interventions, along with providing financial support for women experiencing high levels of stress or potential abuse, could significantly improve nurturing conditions.

Furthermore, offering educational tools and expanding support services, parenting workshops, and access to family support professionals could benefit mothers. However, for these classes or professionals to make meaningful differences, they must be designed to effectively reduce stress and promote positive interactions between parents and children. Simply offering information without practical resources will not lead to immediate changes. Additionally, this research highlights the necessity of addressing social determinants. The findings suggest that policymakers should consider funding initiatives that explore the broader impact of social determinants on maternal health.

Limitations of the Study

This study acknowledges its limitations while highlighting potential applications for database improvements. The current datasets provide a foundation for further exploration of this topic. By thoroughly analyzing the initial research outcomes, understanding maternal and child health, public health, and the social determinants of health can be enriched. The main conclusions of this research support this hypothesis, which suggests that areas with social disarray tend to have a more significant number of mothers exhibiting negative maternal characteristics acquired from domestic environments.

Conclusions

The findings of this research highlight the significant role that family size, caste, maternal education, and wealth status play in shaping academic nurturance. Children from smaller families, advantageous castes, and wealthier backgrounds consistently demonstrated higher academic nurturance and cognitive development. Although academic nurturance does not directly affect cognitive development, this study reveals that socioeconomic factors, particularly ethnicity, family structure, and the age of children, are crucial predictors of children’s cognitive outcomes. These results emphasize the need for targeted interventions to address educational access and outcomes disparities. The study advocates for policies focusing on improving parental education, reducing economic inequalities, and creating inclusive learning environments to foster equitable academic and cognitive growth for all children.

Author Contributions

Data curation, PS and IA; formal analysis, PS, NS, GA, CBB, BD, PT, and IA investigation, PS and IA; methodology, PS and IA; supervision, PS, IA, GA, and NS; writing—review and editing, GA. PS and IA; project administration IA. All authors have read and agreed to publish this version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study received no grants or funding from any source.

Availability of data and materials

Due to privacy restrictions, the data presented in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was carried out on the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical approval, and consent to carried out for the study was secured from the Board of Ethical Review at the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC: No. 2078-56/2021), following prior authorization from the Office of the Dean, Faculty of Education, Tribhuvan University. All the authors agreed/consented to participate in the study. Additionally, all previous research and scholarly contributions relevant to the study were appropriately acknowledged, and their works were cited throughout the research. All the participants agreed and gave their approval and consent to participate in the study and confirm the use of the questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before conducted and used the questionaire and assigned each participant an identification number (ID) which was included in the transcripts field notes,and data analyzing from statistical software.

Consent for publication

The authors give consent for publication.

Acknowledgments

The researchers want to extend their heartfelt gratitude to all the individuals who actively participated in this study. Additionally, we would like to thank the Editors and reviewers for their valuable feedback and insightful suggestions for improving this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The coresponding author IA serves on the editorial board of BMC Public Health Journal.

References

- Ekholuenetale M, Barrow A, Ekholuenetale CE, Tudeme G. Impact of stunting on early childhood cognitive development in Benin: evidence from Demographic and Health Survey. Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette 2020, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro J, Sojourner A, Wiswall MJ. Early childhood care and cognitive development [online]. 2020; 1-84. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Huang KY. Impact of being an adolescent Mother on subsequent maternal health, parenting, and Child Development in Kenyan Low-income and adversity informal settlement. PloS One [online]. 2021 Apr 1;16(4):1-17. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Wreyford N, Newsinger J, Kennedy H, Aust R. Locked down and locked out: mothers and UKTV work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Feminist Media Studies [online]. 2023 Oct 25;24(8):1894-1913. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Webb N, Moloney LJ, Smyth BM, Murphy RL. Allegations of child sexual abuse: An empirical analysis of published judgements from the Family Court of Australia 2012–2019. Australian Journal of Social Issues [online]. 2021 July 14;56(3):322-343. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Mathews F, Ford TJ, White S, Ukoumunne OC, Newlove-Delgado T. Children and young people’s reported contact with professional services for mental health concerns: a secondary data analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry [online]. 2024 Jan 4; 33(8):2647–2655. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Tracy LM, Capell E, Cleland HJ, Edgar DW, Singer Y, Teague WJ, Gabbe BJ. Feasibility of collecting long-term patient-reported outcome data in burns patients using a centralized approach. Burns [online]. 2024 Oct 28;51(1):107304. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Hendry D, Straker L, Bourne B, Coshan S, Kumwembe N, McCarthy C, Zabatiero J. Parental practices and perspectives on health and digital technology use information seeking for children aged 0–36 months. Health Promotion Journal of Australia [online]. 2024 Oct;35(4):1174-1183. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Wen LM, Xu H, Jawad D, Buchanan L, Rissel C, Phongsavan P, Baur LA, Taki S. Ethnicity matters in perceived impacts and information sources of COVID-19 among mothers with young children in Australia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open [online]. 2021 Nov 25;11(11):e050557. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Kim, P. How stress can influence brain adaptations to motherhood. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology [online]. 2021 Jan:60:100875. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Komalasari, R. Harmonizing Midlife Motherhood: Navigating the Intersection of First-Time Maternity and Perimenopause. In Utilizing AI Techniques for the Perimenopause to Menopause Transition. IGI Global; 2024. p. 148-179.

- Koshy B, Srinivasan M, Bose A, John S, Mohan VR, Roshan R, Ramanujam K, Kang G. Developmental trends in early childhood and their predictors from an Indian birth cohort. BMC Public Health [online]. 2021 Jun 6;21(1):1083. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Sally I, Kuo C, Poore HE, Barr PB, Chirico IS, Aliev F, Bucholz KK, Chan G, Kamarajan C, Kramer JR, McCutcheon VV. The role of parental genotype in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior: Evidence for genetic nurturance. Development and psychopathology [online]. 2022 Dec;34(5):1865-1875. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Nas Z, Herle M, Kininmonth AR, Smith AD, Bryant-Waugh R, Fildes A, Llewellyn CH. Nature and nurture in fussy eating from toddlerhood to early adolescence: findings from the Gemini twin cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry [online]. 2024 19 September. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P, Budhathoki CB, Thapa P. Factors Associated with Psychosocial Stimulation Development of Preschool Children in Rupandehi District of Nepal. KMC Journal [online]. 2024;6(1): 20–39. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P, Budhathoki CB, Devkota B, Singh JK. Healthy eating encouragement and sociodemographic factors associated with cognitive development among preschoolers: a cross-sectional evaluation in Nepal. European Journal of Public Health [online]. 2024 Apr 3;34(2):230-236. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis. 2nd ed. Michigan: Harper & Row, 1967; 2009.

- Sharma P, Budhathoki CB, Maharjan RK, Singh JK. Nutritional status and psychosocial stimulation associated with cognitive development in preschool children: A cross-sectional study at Western Terai, Nepal. PLoS ONE [online]. 2023 Mar 13;18(3):e0280032. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Widick C, Parker CA, Knefelkamp L. Erik Erikson and psychosocial development. New Directions for Student Services [online]. 1978;1978(4):1–17. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, and N. I. for C. H. and H. D. (2016). Children of the NLSY79. In Center for Human Resource Research (CHRR), The Ohio State University. Columbus, OH: 2019.

- Ministry of Health, N.E. and I. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. In Ministry of Health, Nepal. 2017. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR336/FR336.

- Sharma P, Adamopoulos I, Syrou N, Budhathoki CB, Thapa P. The Impact of Health-Caregivers Emotional Nurturance on cognitive development in preschoolers: a Nationwide Public Health Cross-Sectional Study. Research Square (Research Square) [online]. 2024 12 December. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H. Impact of preschool education component in integrated child development services programme on the cognitive development of children. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics [online]. 1991 Oct;37(5):235-9. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Contributors, W. Caste system in Nepal - Wikipedia, Google Scholar. At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caste_system_in_Nepal [Accssesed 11-12-2024].

- Jeong J, Franchett EE, Ramos de Oliveira CV, Rehmani K, Yousafzai AK. Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine [online]. 2021 May 10;18(5):e1003602. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Likhar A, Patil MS. Importance of maternal nutrition in the first 1,000 days of life and its effects on child development: a narrative review. Cureus [online]. 2022 Oct 8;14(10):e30083. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Daelmans B, Manji SA, Raina N. Nurturing care for early childhood development: global perspective and guidance. Indian Pediatrics. Indian Pediatr [online]. 2021 Nov 15;58 Suppl 1:S11-S15. [Accessed ]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 26 December 3468.

- Sentenac M, Benhammou V, Aden U, Ancel PY, Bakker LA, Bakoy H, Barros H, Baumann N, Bilsteen JF, Boerch K, Croci I. Maternal education and cognitive development in 15 European very-preterm birth cohorts from the RECAP Preterm platform. International journal of epidemiology [online]. 2022 Jan 6;50(6):1824-1839. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Black MM, Behrman JR, Daelmans B, Prado EL, Richter L, Tomlinson M, Trude AC, Wertlieb D, Wuermli AJ, Yoshikawa H. The principles of Nurturing Care promote human capital and mitigate adversities from preconception through adolescence. BMJ Glob Health [online]. 2021 Apr;6(4):e004436. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Trude AC, Richter LM, Behrman JR, Stein AD, Menezes AM, Black MM. Effects of responsive caregiving and learning opportunities during preschool ages on the association of early adversities and adolescent human capital: an analysis of birth cohorts in two middle-income countries. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health [online]. 2021 Jan 1;5(1):37-46. [Accessed ]. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanchi/PIIS2352-4642(20)30309-6. 26 December.

- McCormick BJ, Caulfield LE, Richard SA, Pendergast L, Seidman JC, Maphula A, Koshy B, Blacy L, Roshan R, Nahar B, Shrestha R. Pediatrics [online]. 2020 Sep;146(3):e20193660. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Venancio SI, Teixeira JA, de Bortoli MC, Bernal RT. Factors associated with early childhood development in municipalities of Ceará, Brazil: a hierarchical model of contexts, environments, and nurturing care domains in a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Regional Health–Americas [online]. 2021 Dec 23:5:100139. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Yang J, Zheng L, Song W, Yi L. Impact of home parenting environment on cognitive and psychomotor development in children under 5 years old: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in pediatrics [online]. 2021 28 September;9:658094. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Welch MG, Barone JL, Porges SW, Hane AA, Kwon KY, Ludwig RJ, Stark RI, Surman AL, Kolacz J, Myers MM. Family nurture intervention in the NICU increases autonomic regulation in mothers and children at 4-5 years of age: Follow-up results from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One [online]. 2020 Aug 4;15(8):e0236930. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Bliznashka L, Udo IE, Sudfeld CR, Fawzi WW, Yousafzai AK. Associations between women’s empowerment and child development, growth, and nurturing care practices in sub-Saharan Africa: A cross-sectional analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS Medicine [online]. 2021 Sep 16;18(9):e1003781. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Cooper K, Stewart K. Does household income affect children’s outcomes? A systematic review of the evidence. Child Indicators Research. 2020 Nov 04;14:981–1005. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Bliznashka, L. , Udo, I. E., Sudfeld, C. R., Fawzi, W. W., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2021). Associations between women’s empowerment and child development, growth, and nurturing care practices in sub-Saharan Africa: A cross-sectional analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS medicine, 0037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood L, Flores-Barrantes P, Moreno LA, Manios Y, Gonzalez-Gil EM. The influence of parental dietary behaviors and practices on children’s eating habits. Nutrients [online]. 2021 Mar 30;13(4):1138. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Vilela S, Muresan I, Correia D, Severo M, Lopes C. The role of socioeconomic factors in food consumption of Portuguese children and adolescents: results from the National Food, Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2015–2016. British Journal of Nutrition [online]. 2020 Sep 28;124(6):591-601. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Penna AL, de Aquino CM, Pinheiro MSN, do Nascimento RLF, Farias-Antúnez S, Araújo DABS, Mita C, Machado MMT, Castro MC. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal mental health, early childhood development, and parental practices: a global scoping review. BMC Public Health [online]. 2023 Feb 24;23(1):388. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Shumba C, Maina R, Mbuthia G, Kimani R, Mbugua S, Shah S, Abubakar A, Luchters S, Shaibu S, Ndirangu E. Reorienting nurturing care for early childhood development during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya: a review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [online]. 2020 Sep 25;17(19):7028. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Jeong J, Pitchik HO, Fink G. Short-term, medium-term and long-term effects of early parenting interventions in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health [online]. 2021 Mar;6(3):e004067. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Singh K, Kondal D, Mohan S, Jaganathan S, Deepa M, Venkateshmurthy NS, Jarhyan P, Anjana RM, Narayan KV, Mohan V, Tandon N. Health, psychosocial, and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with chronic conditions in India: a mixed methods study. BMC Public Health [online]. 2021 Dec;21:1-5. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos I, Frantzana A, Syrou N. Climate crises associated with epidemiological, environmental, and ecosystem effects of a storm: Flooding, landslides, and damage to urban and rural areas (Extreme weather events of Storm Daniel in Thessaly, Greece). Medical Sciences Forum [online]. 2024;25(1):7. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos I, Lamnisos D, Syrou N, Boustras G. Public health and work safety pilot study: Inspection of job risks, burn out syndrome and job satisfaction of public health inspectors in Greece. Safety Science [online]. 2022 Mar:147;105592. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos I, Syrou N, Lamnisos D, Boustras G., 2023. Cross-sectional nationwide study in occupational safety & health: Inspection of job risks context, burn out syndrome and job satisfaction of public health Inspectors in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Saf Sci [online]. 2023 Feb;158:105960. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos I, Syrou N, Lamnisos D, Dounias G. Public Health Inspectors Classification and Assessment of Environmental, Psychosocial, Organizational Risks and Workplace Hazards in the context of the Global Climate Crisis [online]. Preprints 2024, 2024120639. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos I, Lamnisos D, Syrou N, Boustras G. Training Needs and Quality of Public Health Inspectors in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Public Health [online]. 2022 Oct 25;32(Suppl 3):ckac131.373. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos IP, Frantzana AA, Syrou NF. General practitioners, health inspectors, and occupational physicians’ burnout syndrome during COVID-19 pandemic and job satisfaction: A systematic review [online]. EUR J ENV PUBLIC HLT. 2024;8(3):em0160. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos IP, Frantzana AA, Syrou NF. Medical educational study burnout and job satisfaction among general practitioners and occupational physicians during the COVID-19 epidemic. Electr J Med Educ Technol [online]. 2024; 17(1):em2402. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Hegedűs M, Szivós E, Adamopoulus I, Dávid LD. (2024). Hospital integration to improve the chances of recovery for decubitus (pressure ulcer) patients through centralized procurement procedures. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development [online]. 8(10): 7273. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Thapa P, Adamopoulos IP, Sharma P, Lordkipanidze R. Public hygiene and the awareness of beauty parlor: A study of consumer perspective. EUR J ENV PUBLIC HLT [online]. 2024;8(2):em0157. [Accessed ]. 26 December. [CrossRef]

- Ali G, Mijwil MM, Adamopoulos I, Buruga BA, Gök M, Sallam M. Harnessing the Potential of Artificial Intelligence in Managing Viral Hepatitis. Mesopotamian Journal of Big Data [online]. 2024 August 15th [cited 2024 December 29th];2024:128-63. [Accessed ]. Available from:. 26 December.

- Khan, A. J. J.; Yar, S.; Fayyaz, S.; Adamopoulos, I.; Syrou, N.; Jahangir, A. From Pressure to Performance, and Health Risks Control: Occupational Stress Management and Employee Engagement in Higher Education. Preprints, 26 December 0241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, I.; Syrou, N.; Lamnisos, D.; Dounias, G. Public Health Inspectors Classification and Assessment of Environmental, Psychosocial, Organizational Risks and Workplace Hazards in the Context of the Global Climate Crisis. Preprints, 26 December 0241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).