Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

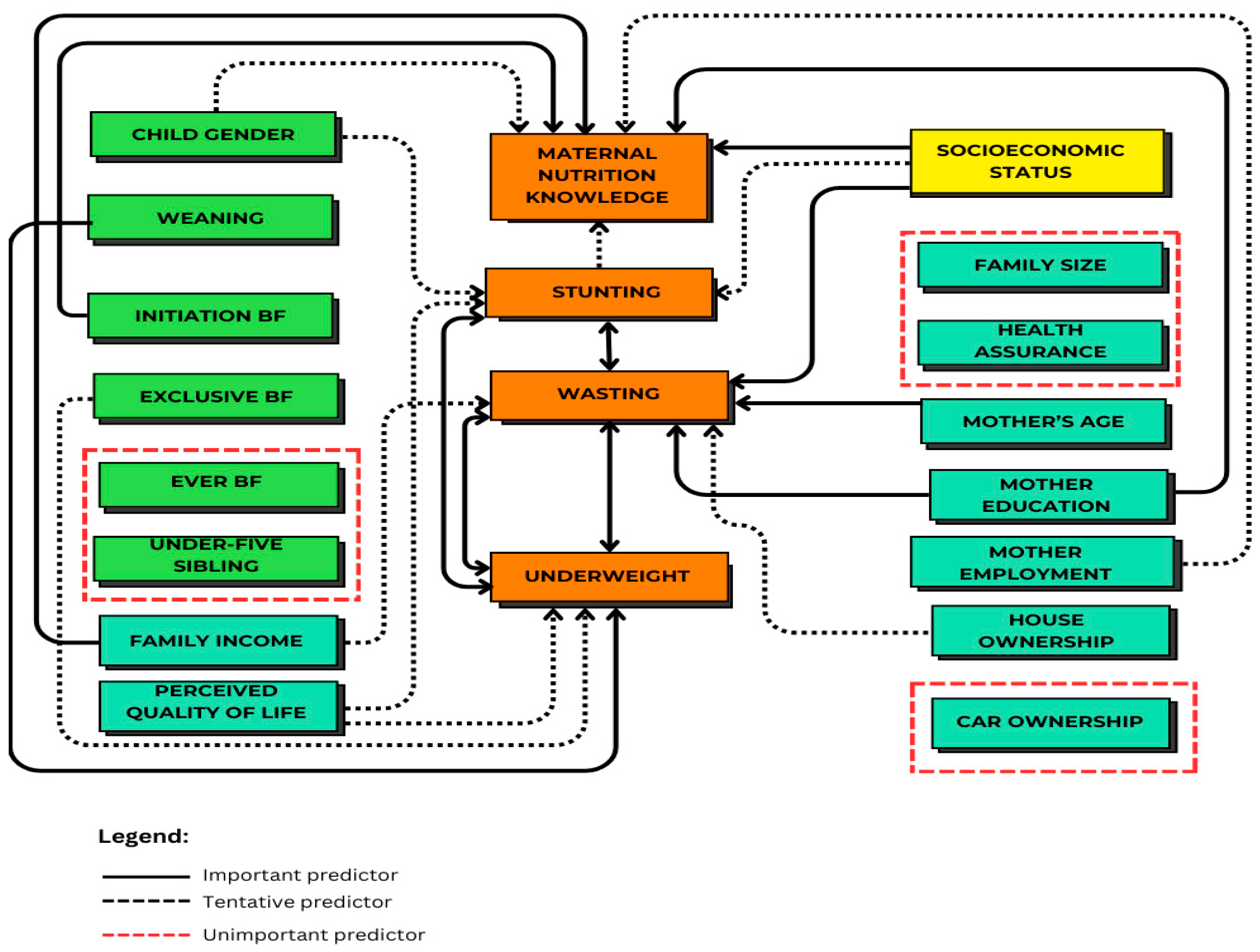

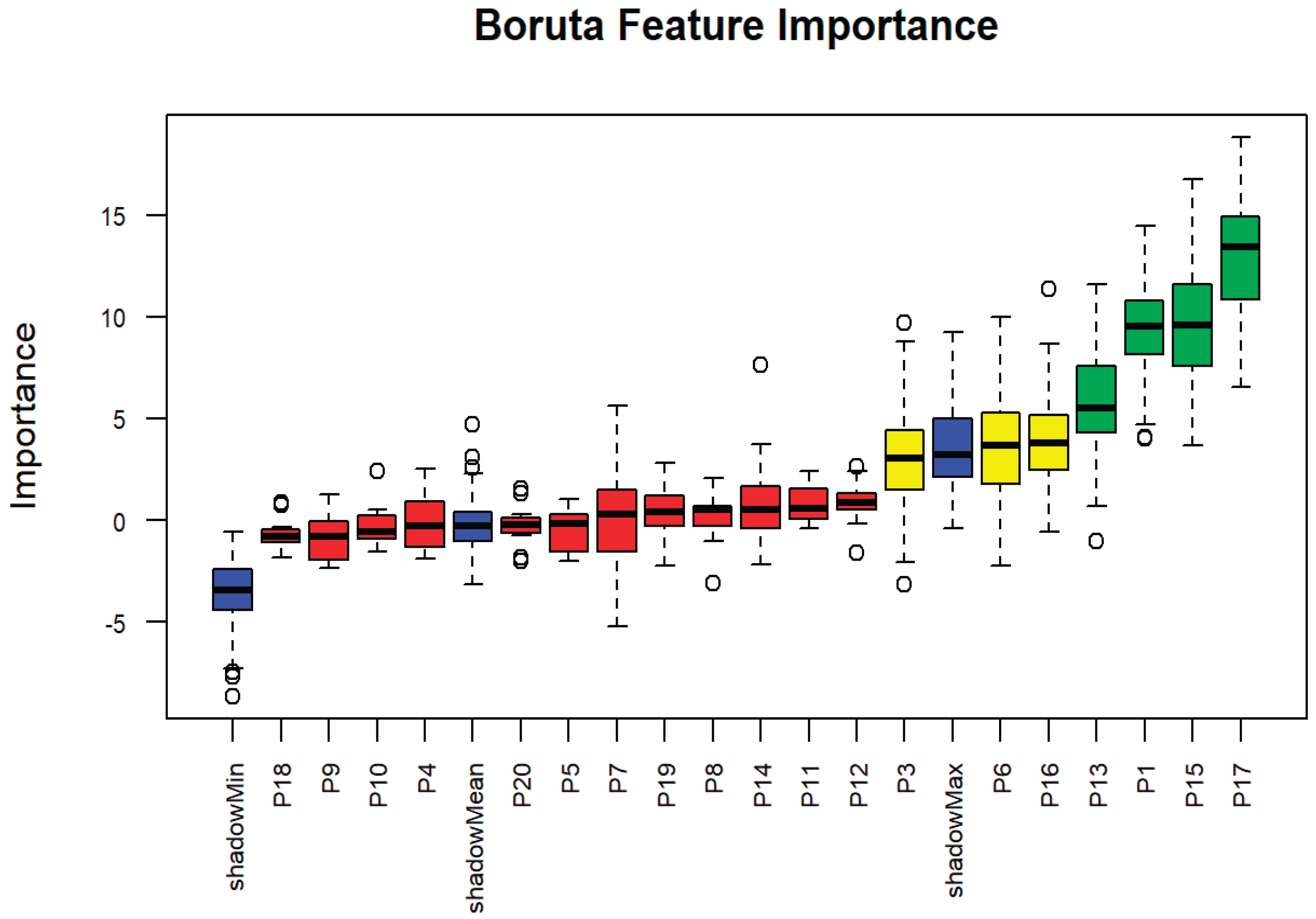

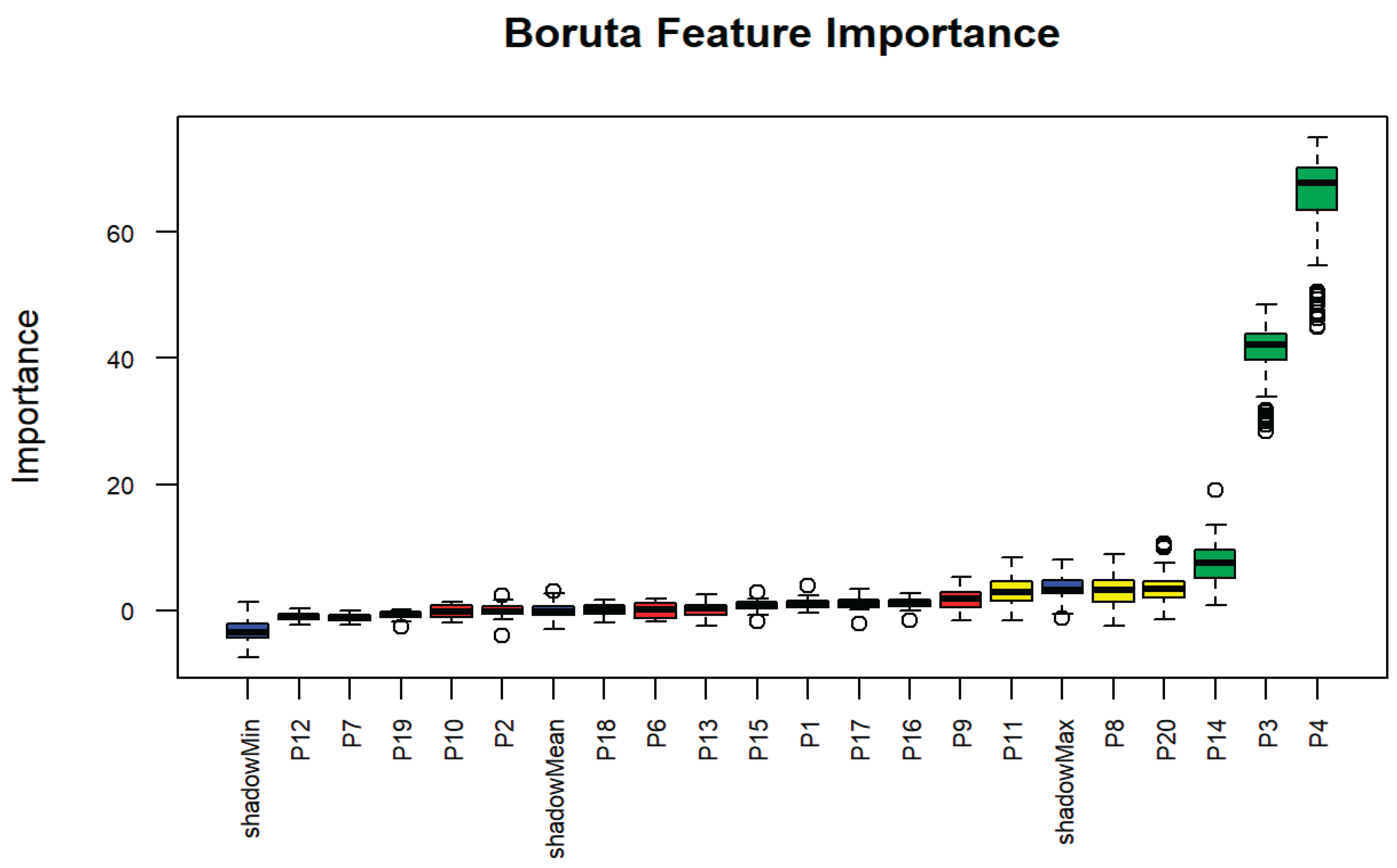

3.2. The Important Predictors of Maternal Nutrition Knowledge (MNK)

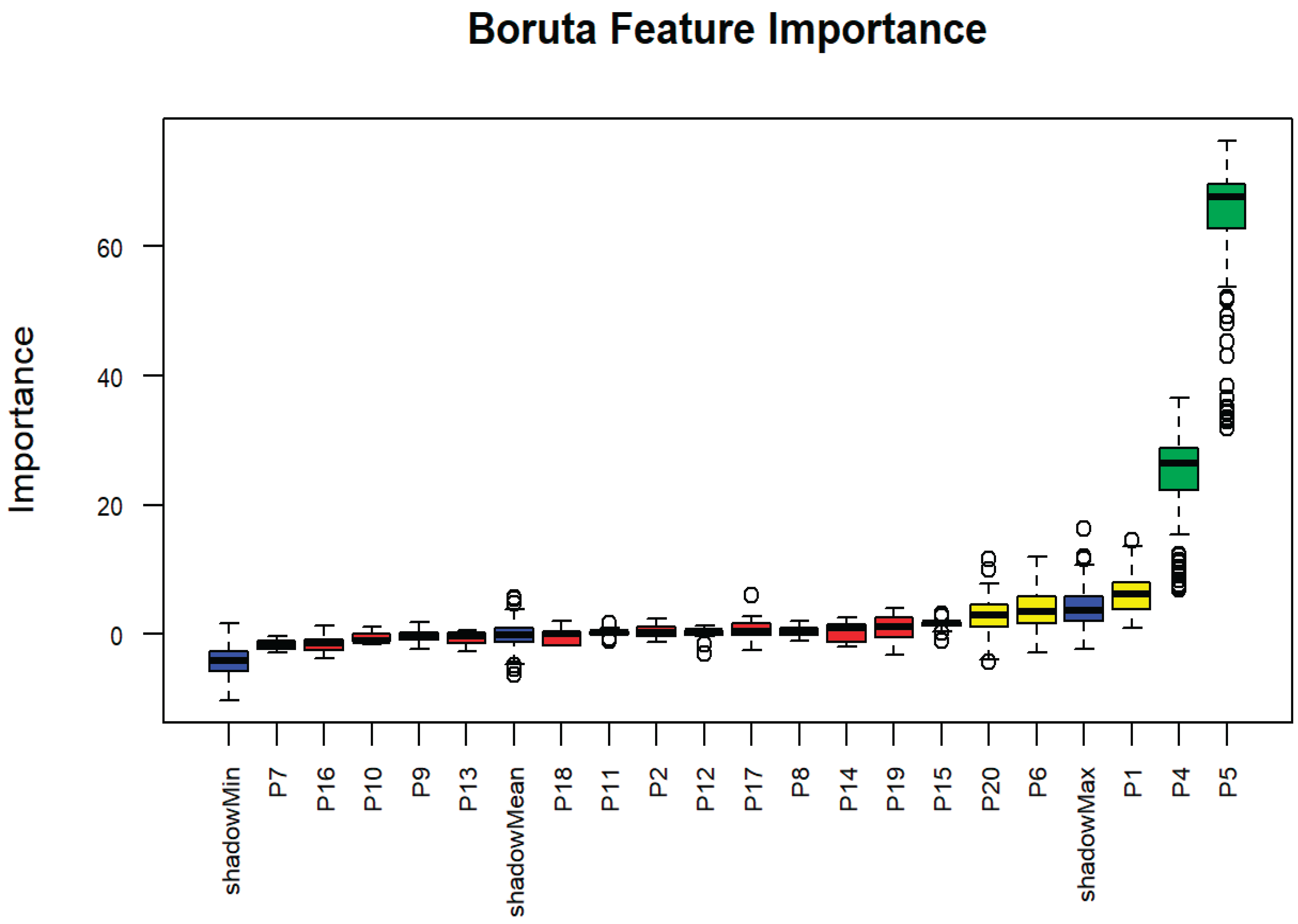

3.3. The Importance Predictors of Stunting

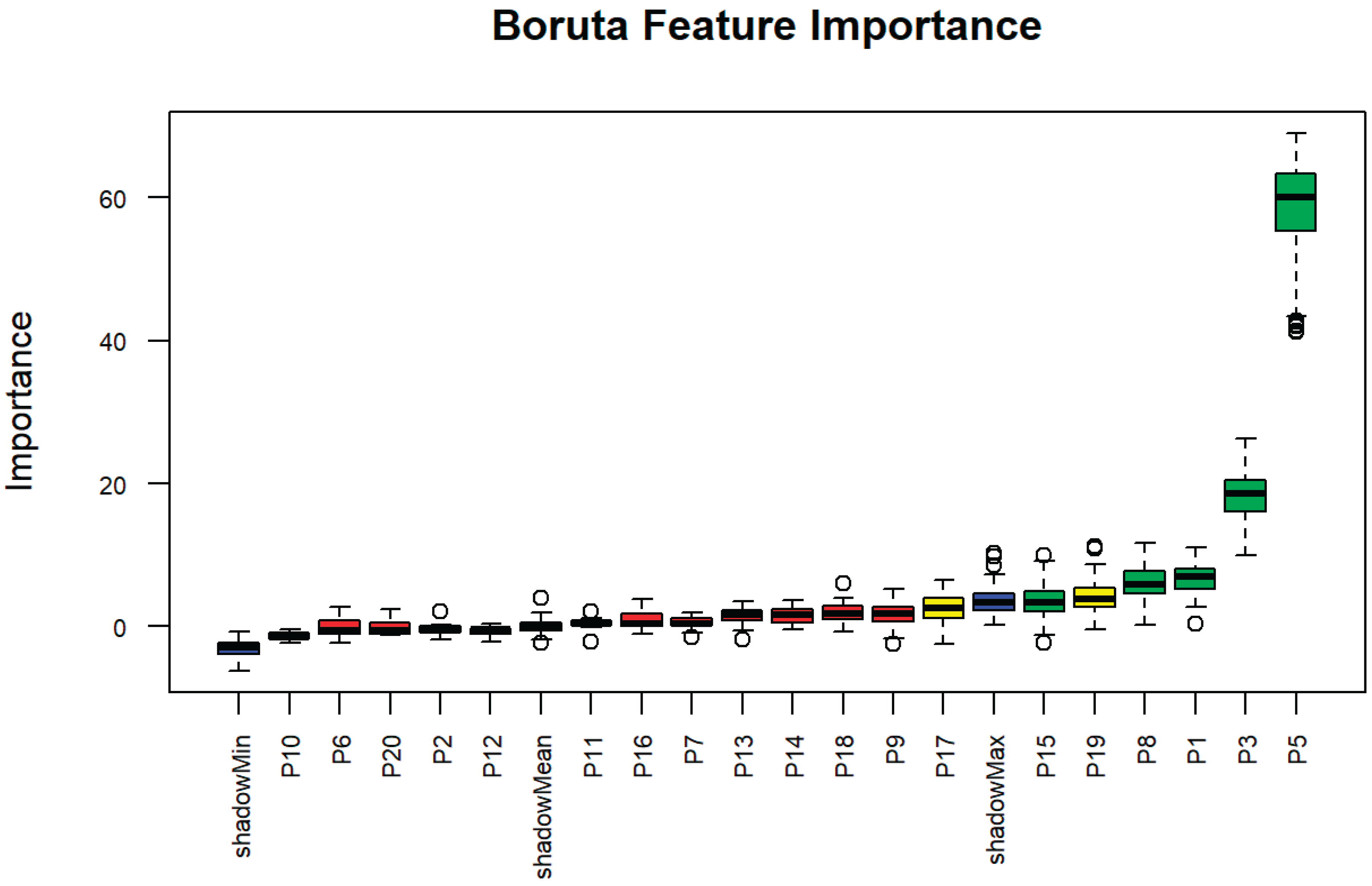

3.4. The Importance Predictors of Wasting

3.5. The Importance Predictors of Underweight

4. Discussion

4.1. Socioeconomic Status and Maternal Nutrition Knowledge (MNK)

4.2. Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Child Undernutrition

4.3. Strengths and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MNK | Maternal nutrition knowledge |

| CSDH | Conceptual Framework for Action on The Social Determinants of Health |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| WebApps | Web applications |

| APK | Android Package Kit |

| BF | Breastfeeding |

| WHZ | Weight for height Z-score |

| HAZ | Height for age Z-score |

| WAZ | Weight for age Z-score |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| IYCF | Infant and young child feeding |

| GNKQ-R | General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire-Revised |

References

- UNICEF, WHO, WORLD BANK. Level and trend in child malnutrition. World Health Organization [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Dec 23];4. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073791.

- Rahut DB, Mishra R, Bera S. Geospatial and environmental determinants of stunting, wasting, and underweight: Empirical evidence from rural South and Southeast Asia. Nutrition. 2024 Apr 1;120:112346. [CrossRef]

- WHO, UNICEF. WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund. WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2024 Dec 23];11. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44129/1/9789241598163_eng.pdf.

- Briend A, Khara T, Dolan C. Wasting and stunting--similarities and differences: policy and programmatic implications. Food Nutr Bull [Internet]. 2015 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Dec 23];36(1 Suppl):S15–23. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25902610/ . [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Underweight among children under 5 years of age (number in millions) (JME) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/gho-jme-underweight-numbers-(in-millions).

- Siddiqui F, Salam RA, Lassi ZS, Das JK. The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Aug 28 [cited 2024 Dec 23];8:525026. Available from: www.frontiersin.org . [CrossRef]

- Rini Puji Lestari T. STUNTING IN INDONESIA: UNDERSTANDING THE ROOTS OF THE PROBLEM AND SOLUTIONS. PUSAKA DPR RI [Internet]. 2023 Jul [cited 2024 Dec 23];Vol. XV / No. 14. Available from: https://berkas.dpr.go.id/pusaka/files/info_singkat/Info%20Singkat-XV-14-II-P3DI-Juli-2023-196-EN.pdf.

- Kamiya Y. Socioeconomic Determinants of Nutritional Status of Children in Lao PDR: Effects of Household and Community Factors. J Health Popul Nutr [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2024 Dec 23];29(4):339. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3190364/ . [CrossRef]

- Ijaiya MA, Anjorin S, Uthman OA. Income and education disparities in childhood malnutrition: a multi-country decomposition analysis. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Dec 23];24(1):2882. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-024-20378-z . [CrossRef]

- Yani DI, Rahayuwati L, Sari CWM, Komariah M, Fauziah SR. Family Household Characteristics and Stunting: An Update Scoping Review. Nutrients [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Dec 23];15(1):233. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9824547/ . [CrossRef]

- Fadare O, Amare M, Mavrotas G, Akerele D, Ogunniyi A. Mother’s nutrition-related knowledge and child nutrition outcomes: Empirical evidence from Nigeria. PLoS One [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Dec 23];14(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30817794/ . [CrossRef]

- Hosen MZ, Pulok MH, Hajizadeh M. Effects of maternal employment on child malnutrition in South Asia: An instrumental variable approach. Nutrition [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Dec 23];105. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36335875/ . [CrossRef]

- Debela BL, Demmler KM, Rischke R, Qaim M. Maternal nutrition knowledge and child nutritional outcomes in urban Kenya. Appetite. 2017 Sep 1;116:518–26. [CrossRef]

- Maternal Nutrition and Complementary Feeding | UNICEF East Asia and Pacific [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/eap/reports/maternal-nutrition-and-complementary-feeding.

- Mohammed EAI, Taha Z, Eldam AAAG, Shommo SAM, El Hidai MM, Mohammed I, et al. Effectiveness of a Nutrition Education Program in Improving Mothers’ Knowledge and Feeding Practices of Infants and Young Children in Sudan. Open Access Maced J Med Sci [Internet]. 2022 Mar 3 [cited 2024 Dec 23];10(E):776–82. Available from: https://oamjms.eu/index.php/mjms/article/view/8842 . [CrossRef]

- Effendy DS, Prangthip P, Soonthornworasiri N, Winichagoon P, Kwanbunjan K. Nutrition education in Southeast Sulawesi Province, Indonesia: A cluster randomized controlled study. Matern Child Nutr [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Dec 23];16(4):e13030. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7507461/ . [CrossRef]

- Setia A, Shagti I, Maria Boro RA, Mirah Adi A, Saleh A, Amryta Sanjiwany P. The Effect of Family-Based Nutrition Education on the Intention of Changes in Knowledge, Attitude, Behavior of Pregnant Women and Mothers With Toddlers in Preventing Stunting in Puskesmas Batakte, Kupang Regency, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia Working Area. 14(3).

- Black MM, Delichatsios HK, Story MT, editors. Nutrition Education: Strategies for Improving Nutrition and Healthy Eating in Individuals and Communities. 2019 Nov 28 [cited 2025 Sep 12];92. Available from: https://karger.com/books/book/115/Nutrition-Education-Strategies-for-Improving.

- Prasetyo YB, Permatasari P, Susanti HD. The effect of mothers’ nutritional education and knowledge on children’s nutritional status: a systematic review. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Sep 12];17(1):1–16. Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s40723-023-00114-7 . [CrossRef]

- Demilew YM, Alene GD, Belachew T. Effect of guided counseling on nutritional status of pregnant women in West Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Nutr J [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2025 Sep 12];19(1):1–12. Available from: https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12937-020-00536-w . [CrossRef]

- Wahyurin IS, Aqmarina AN, Rahmah HA, Hasanah AU, Silaen CNB. Effect of stunting education using brainstorming and audiovisual methods towards knowledge of mothers with stunted children. Ilmu Gizi Indonesia [Internet]. 2019 Feb 25 [cited 2025 Sep 12];2(2):141–6. Available from: https://ilgi.respati.ac.id/index.php/ilgi2017/article/view/111.

- Suryati S, Supriyadi S. THE EFFECT OF BOOKLET EDUCATION ABOUT CHILDREN NUTRITION NEEDS TOWARD KNOWLEDGE OF MOTHER WITH STUNTING CHILDREN IN PUNDONG PRIMARY HEALTH CENTER WORK AREA BANTUL YOGYAKARTA. Procceeding the 4th International Nursing Conference [Internet]. 2019 Nov 28 [cited 2025 Sep 12];0(0):102–9. Available from: https://jurnal.unmuhjember.ac.id/index.php/INC/article/view/2703.

- Dinengsih S, Hakim N. The influence of the lecture method and the android-based application method on adolescent reproductive health knowledge. JKM (Jurnal Kebidanan Malahayati) [Internet]. 2020 Oct 26 [cited 2025 Sep 12];6(4):515–22. Available from: https://ejurnalmalahayati.ac.id/index.php/kebidanan/article/view/2975.

- Patel AB, Kuhite PN, Alam A, Pusdekar Y, Puranik A, Khan SS, et al. M-SAKHI—Mobile health solutions to help community providers promote maternal and infant nutrition and health using a community-based cluster randomized controlled trial in rural India: A study protocol. Matern Child Nutr. 2019 Oct 1;15(4). [CrossRef]

- Mistry SK, Hossain MB, Arora A. Maternal nutrition counselling is associated with reduced stunting prevalence and improved feeding practices in early childhood: A post-program comparison study. Nutr J [Internet]. 2019 Aug 27 [cited 2025 Sep 12];18(1):1–9. Available from: https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12937-019-0473-z . [CrossRef]

- Kassaw MW, Bitew AA, Gebremariam AD, Fentahun N, Açik M, Ayele TA. Low Economic Class Might Predispose Children under Five Years of Age to Stunting in Ethiopia: Updates of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Nutr Metab [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 12];2020. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33489361/ . [CrossRef]

- A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852.

- Health C on EHP to A the SD of, Health B on G, Medicine I of, National Academies of Sciences E and M. Frameworks for Addressing the Social Determinants of Health. 2016 Oct 14 [cited 2025 Sep 12]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK395979/.

- UNICEF, York) UNICEFEB (1990 sess. : N. Strategy for improved nutrition of children and women in developing countries. [Internet]. UNICEF,; 1990 [cited 2025 Sep 12]. Available from: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/227230.

- Marrie RA. Demographic, Genetic, and Environmental Factors That Modify Disease Course. Neurol Clin [Internet]. 2011 May 1 [cited 2025 Aug 7];29(2):323–41. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S073386191000157X . [CrossRef]

- Socioeconomic status [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/topics/socioeconomic-status.

- McKinsey. Personalized Medicine - The path forward. Translational Informatics. 2013;35–60.

- Fiala MA, Finney JD, Liu J, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Tomasson MH, Vij R, et al. Socioeconomic Status is Independently Associated with Overall Survival in Patients with Multiple Myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma [Internet]. 2015 Sep 2 [cited 2025 Aug 7];56(9):2643. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4831207/ . [CrossRef]

- Kliemann N, Wardle J, Johnson F, Croker H. Reliability and validity of a revised version of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Eur J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2016 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Dec 23];70(10):1174–80. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27245211/ . [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara Y, Narumi-Hyakutake A. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and nutritional adequacy in Japanese university students: a cross-sectional study. J Nutr Sci [Internet]. 2025 Feb 5 [cited 2025 Aug 7];14:e14. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11811863/ . [CrossRef]

- English - WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children - NCBI Bookshelf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK200776/?report=reader.

- Saleem J, Zakar R, Butt MS, Aadil RM, Ali Z, Bukhari GMJ, et al. Application of the Boruta algorithm to assess the multidimensional determinants of malnutrition among children under five years living in southern Punjab, Pakistan. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Dec 23];24(1):1–10. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-024-17701-z . [CrossRef]

- Kursa MB, Rudnicki WR. Feature Selection with the Boruta Package. J Stat Softw [Internet]. 2010 Sep 16 [cited 2024 Dec 23];36(11):1–13. Available from: https://www.jstatsoft.org/index.php/jss/article/view/v036i11 . [CrossRef]

- Jaringan Dokumentasi dan Informasi Hukum [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 13]. Available from: https://dokumjdih.jatimprov.go.id/arsip/info/48965.html.

- Pandey S, Karki S. Socio-economic and Demographic Determinants of Antenatal Care Services Utilization in Central Nepal. Int J MCH AIDS [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Aug 9];2(2):212. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4948147/.

- Escañuela Sánchez T, Linehan L, O’Donoghue K, Byrne M, Meaney S. Facilitators and barriers to seeking and engaging with antenatal care in high-income countries: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Health Soc Care Community [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Aug 9];30(6):e3810. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10092326/ . [CrossRef]

- Yadav AK, Sahni B, Jena PK. Education, employment, economic status and empowerment: Implications for maternal health care services utilization in India. J Public Aff [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Aug 9];21(3):e2259. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1002/pa.2259 . [CrossRef]

- Harvey CM, Newell ML, Padmadas S. Maternal socioeconomic status and infant feeding practices underlying pathways to child stunting in Cambodia: structural path analysis using cross-sectional population data. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2022 Nov 3 [cited 2025 Aug 9];12(11):e055853. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9639063/ . [CrossRef]

- Tahreem A, Rakha A, Anwar R, Rabail R, Maerescu CM, Socol CT, et al. Impact of maternal nutritional literacy and feeding practices on the growth outcomes of children (6–23 months) in Gujranwala: a cross-sectional study. Front Nutr. 2024 Jan 7;11:1460200. [CrossRef]

- Gbratto-Dobe SAW, Segnon HB. Is mother’s education essential to improving the nutritional status of children under five in Côte d′Ivoire? SSM - Health Systems [Internet]. 2025 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Sep 13];4:100056. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S294985622500008X.

- Phyo WY, Khin OK, Aung MH. Mothers’ Nutritional Knowledge, Self-efficacy, and Practice of Meal Preparation for School-age Children in Yangon. Makara Journal of Health Research [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 13];25:25. Available from: https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/mjhr.

- Thomas D, Strauss J, Henriques MH. How Does Mother’s Education Affect Child Height? J Hum Resour. 1991 Spring;26(2):183. [CrossRef]

- Prickett KC, Augustine JM. Maternal Education and Investments in Children’s Health. J Marriage Fam [Internet]. 2015 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Sep 13];78(1):7. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4712746/ . [CrossRef]

- Wang WC, Zou SM, Ding Z, Fang JY. Nutritional knowledge, attitude and practices among pregnant females in 2020 Shenzhen China: A cross-sectional study. Prev Med Rep [Internet]. 2023 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Sep 13];32:102155. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9975685/ . [CrossRef]

- Forh G, Apprey C, Frimpomaa Agyapong NA. Nutritional knowledge and practices of mothers/caregivers and its impact on the nutritional status of children 6–59 months in Sefwi Wiawso Municipality, Western-North Region, Ghana. Heliyon [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Aug 9];8(12):e12330. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844022036180 . [CrossRef]

- Albanus FS, Ashipala DO. Nutritional knowledge and practices of mothers with malnourished children in a regional hospital in Northeast Namibia. J Public Health Afr [Internet]. 2023 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Aug 9];14(8):2391. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10519119/ . [CrossRef]

- Atsu BK, Guure C, Laar AK. Determinants of overweight with concurrent stunting among Ghanaian children. BMC Pediatr [Internet]. 2017 Jul 27 [cited 2025 Aug 11];17(1):1–12. Available from: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-017-0928-3 . [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury MRK, Rahman MS, Billah B, Kabir R, Perera NKP, Kader M. The prevalence and socio-demographic risk factors of coexistence of stunting, wasting, and underweight among children under five years in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Aug 11];8(1):1–12. Available from: https://bmcnutr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40795-022-00584-x . [CrossRef]

- Soekatri MYE, Sandjaja S, Syauqy A. Stunting Was Associated with Reported Morbidity, Parental Education and Socioeconomic Status in 0.5–12-Year-Old Indonesian Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, Vol 17, Page 6204 [Internet]. 2020 Aug 27 [cited 2025 Aug 11];17(17):6204. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/17/6204/htm . [CrossRef]

- Silas VD, Pomat W, Jorry R, Emori R, Maraga S, Kue L, et al. Household food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated socioeconomic demographic factors in Papua New Guinea: Evidence from the Comprehensive Health and Epidemiological Surveillance System. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2023 Nov 19 [cited 2025 Aug 11];8(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37984899/ . [CrossRef]

- Arini D, Ernawati D, Hayudanti D, Alristina AD. Impact of socioeconomic change and hygiene sanitation during pandemic COVID-19 towards stunting. International Journal of Public Health Science (IJPHS) [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jul 27];11(4):1382–90. Available from: https://ijphs.iaescore.com/index.php/IJPHS/article/view/21602 . [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel NB, Mapatano MA, Celestin BLN, Kalombola C, Gérard MM, Bavon TM, et al. Complementary Feeding Practices Associated With Malnutrition in Children Aged 6-23 Months in the Tshamilemba Health Zone, Haut-Katanga, DRC, 2021. Acta Scientifci Nutritional Health. 2023;02–17. [CrossRef]

- Alristina C:, Mahrouseh AD;, Irawan N;, Laili AS;, Zimonyi-Bakó RD;, Feith AV;, et al. Prematurity and Low Birth Weight Among Food-Secure and Food-Insecure Households: A Comparative Study in Surabaya, Indonesia. Nutrients 2025, Vol 17, Page 2479 [Internet]. 2025 Jul 29 [cited 2025 Aug 1];17(15):2479. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/17/15/2479/htm.

- Adhikari N, Acharya K, Upadhya DP, Pathak S, Pokharel S, Pradhan PMS. Infant and young child feeding practices and its associated factors among mothers of under two years children in a western hilly region of Nepal. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jan 7];16(12):e0261301. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8675745/ . [CrossRef]

- Noort MWJ, Renzetti S, Linderhof V, du Rand GE, Marx-Pienaar NJMM, de Kock HL, et al. Towards Sustainable Shifts to Healthy Diets and Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa with Climate-Resilient Crops in Bread-Type Products: A Food System Analysis. Foods [Internet]. 2022 Jan 2 [cited 2025 Aug 11];11(2):135. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/11/2/135/htm . [CrossRef]

- Ogunniran OP, Ayeni KI, Shokunbi OS, Krska R, Ezekiel CN. A 10-year (2014-2023) review of complementary food development in sub-Saharan Africa and the impact on child health. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 11]; Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Oniang’o R, Maingi Z, Jaika S, Konyole S. Africa’s contribution to global sustainable and healthy diets: a scoping review. Front Nutr. 2025 May 2;12:1519248. [CrossRef]

- Asebe HA, Asmare ZA, Mare KU, Kase BF, Tebeje TM, Asgedom YS, et al. The level of wasting and associated factors among children aged 6–59 months in sub-Saharan African countries: multilevel ordinal logistic regression analysis. Front Nutr. 2024 Jun 6;11:1336864. [CrossRef]

- Headey DD, Ruel MT. Economic shocks predict increases in child wasting prevalence. Nature Communications 2022 13:1 [Internet]. 2022 Apr 20 [cited 2025 Aug 11];13(1):1–9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-29755-x . [CrossRef]

- Lawal SA, Okunlola DA, Adegboye OA, Adedeji IA. Mother’s education and nutritional status as correlates of child stunting, wasting, underweight, and overweight in Nigeria: Evidence from 2018 Demographic and Health Survey. Nutr Health [Internet]. 2024 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Sep 13];30(4):821–30. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36591921/ . [CrossRef]

- Okutse AO, Athiany H. Socioeconomic disparities in child malnutrition: trends, determinants, and policy implications from the Kenya demographic and health survey (2014 - 2022). BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Aug 11];25(1):1–17. Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-024-21037-z . [CrossRef]

- Ajmal S, Ajmal L, Ajmal M, Nawaz G. Association of Malnutrition With Weaning Practices Among Infants in Pakistan. Cureus [Internet]. 2022 Nov 2 [cited 2024 Dec 24];14(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36475148/ . [CrossRef]

- Pereira TA de M, Freire AKG, Gonçalves VSS. EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND UNDERWEIGHT IN CHILDREN UNDER SIX MONTHS OLD MONITORED IN PRIMARY HEALTH CARE IN BRAZIL, 2017. Revista Paulista de Pediatria [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 13];39:e2019293. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7418335/.

- Erda R, Hamidi D, Desmawati D, Rasyid R, Sarfika R. Evaluating socio-demographic, behavioral, and maternal factors in the dual burden of malnutrition among school-aged children in Batam, Indonesia. Narra J [Internet]. 2025 Feb 21 [cited 2025 Sep 16];5(1):e2049. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12059860/ . [CrossRef]

- Dembedza VP, Mapara J, Chopera P, Macheka L. Relationship between cultural food taboos and maternal and child nutrition: A systematic literature review. North African Journal of Food and Nutrition Research [Internet]. 2025 Mar 13 [cited 2025 Aug 11];9(19):95–117. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/najfnr/article/view/292015 . [CrossRef]

- Lekey A, Masumo RM, Jumbe T, Ezekiel M, Daudi Z, McHome NJ, et al. Food taboos and preferences among adolescent girls, pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, and children aged 6–23 months in Mainland Tanzania: A qualitative study. PLOS Global Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Aug 12 [cited 2025 Aug 11];4(8):e0003598. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0003598 . [CrossRef]

- Journal TI. To Explore the Perceived Food Taboos during Pregnancy and their Relation to Maternal Nutrition and Health. Texila International Journal of Academic Research [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Aug 11];60–74. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/106137666/To_Explore_the_Perceived_Food_Taboos_during_Pregnancy_and_their_Relation_to_Maternal_Nutrition_and_Health.

- Ajmal S, Ajmal L, Ajmal M, Nawaz G. Association of Malnutrition With Weaning Practices Among Infants in Pakistan. Cureus [Internet]. 2022 Nov 2 [cited 2025 Aug 11];14(11):e31018. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9717723/ . [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

| Socioeconomic status: | ||

| Low | 36 | 5.5 |

| Middle | 588 | 89.5 |

| High | 33 | 5.0 |

| Maternal nutrition knowledge (MNK): | ||

| Low | 180 | 27.4 |

| Moderate | 473 | 72.0 |

| High | 4 | 6.0 |

| Mother’s age: | ||

| < 20 years | 1 | 2.0 |

| 20 to 29 years | 100 | 15.2 |

| 30 to 39 years | 336 | 51.1 |

| ≥ 40 years | 220 | 33.5 |

| Family size: | ||

| ≤3 members | 114 | 17.4 |

| 4 - 6 members | 449 | 68.3 |

| >6 members | 94 | 14.3 |

| Under-five sibling: | ||

| ≤2 children | 621 | 94.5 |

| ≥3 children | 36 | 5.5 |

| Child gender: | ||

| Boy | 326 | 49.6 |

| Girl | 331 | 50.4 |

| Child health insurance: | ||

| Yes | 353 | 53.7 |

| No | 304 | 46.3 |

| Stunting: | ||

| Yes | 166 | 25.3 |

| No | 491 | 74.7 |

| Wasting: | ||

| Yes | 106 | 16.1 |

| No | 551 | 83.9 |

| Underweight: | ||

| Yes | 148 | 22.5 |

| No | 509 | 77.5 |

| Ever breastfeeding: | ||

| Yes | 604 | 91.9 |

| No | 53 | 8.1 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding: | ||

| Yes | 245 | 37.3 |

| No | 412 | 62.7 |

| Initiation breastfeeding: | ||

| Within 1 hour | 214 | 32.6 |

| After 1 hour or more | 443 | 67.4 |

| Weaning practices: | ||

| Less than 6 months | 124 | 18.9 |

| Between 6 months - 24 months | 330 | 50.2 |

| 24 months or more | 203 | 30.9 |

| Mother education: | ||

| No education | 4 | 0.6 |

| Primary school | 179 | 27.2 |

| High school | 376 | 57.2 |

| Higher degree and above | 98 | 14.9 |

| Mother employment status: | ||

| Employed | 278 | 42.3 |

| Unemployed | 379 | 57.7 |

| Family income: | ||

| ≤ Rp 2.300.000 per month | 259 | 39.4 |

| Rp 2.300.001 - Rp 4.500.000 per month | 291 | 44.3 |

| Rp 4.500.001 - Rp 5.700.000 per month | 61 | 9.3 |

| Rp 5.700.001 - Rp 7.000.000 per month | 26 | 4.0 |

| Rp 7.000.001 - Rp 10.000.000 per month | 13 | 2.0 |

| > Rp 10.000.001 per month | 7 | 1.1 |

| Car ownership: | ||

| Yes | 83 | 12.6 |

| No | 574 | 87.4 |

| House ownership: | ||

| Yes | 213 | 32.4 |

| No | 444 | 67.6 |

| Perceived quality of life: | ||

| Rather better off | 202 | 30.7 |

| Average | 436 | 66.4 |

| Rather worse off | 19 | 2.9 |

| Code Variables |

Mean imp. |

Median imp. |

Min imp. |

Max imp. |

Norm hits | Decision |

| P1. SES | 9.398 | 9.543 | 4.025 | 14.438 | 0.980 | Confirmed |

| P3. Stunting | 3.003 | 3.024 | -3.153 | 9.706 | 0.374 | Tentative |

| P4. Wasting | -0.135 | -0.301 | -1.896 | 2.507 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P5. Underweight | -0.505 | -0.182 | -2.009 | 1.029 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P6. Child gender | 3.812 | 3.649 | -2.207 | 9.991 | 0.475 | Tentative |

| P7. Health assurance | 0.202 | 0.276 | -5.197 | 5.626 | 0.051 | Rejected |

| P8. Mother’s age | 0.064 | 0.518 | -3.104 | 2.075 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P9. Family size | -0.901 | -0.789 | -2.344 | 1.277 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P10. Under-five sibling | -0.243 | -0.551 | -1.527 | 2.406 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P11.Exclusive BF | 0.837 | 0.589 | -0.403 | 2.412 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P12.Ever BF | 0.887 | 0.890 | -1.600 | 2.638 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P13. Initiation BF | 5.892 | 5.516 | -1.014 | 11.589 | 0.727 | Confirmed |

| P14.Weaning practices | 0.938 | 0.550 | -2.183 | 7.634 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| P15.Mother education | 9.521 | 9.556 | 3.691 | 16.766 | 0.980 | Confirmed |

| P16.Mother employment | 3.806 | 3.795 | -0.569 | 11.37 | 0.556 | Tentative |

| P17.Family income | 13.013 | 13.43 | 6.525 | 18.811 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P18.Car Ownership | -0.636 | -0.815 | -1.824 | 0.857 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P19.House Ownership | 0.313 | 0.421 | -2.235 | 2.812 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P20.Perceived quality of life | -0.225 | -0.202 | -2.006 | 1.542 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| Code Variables |

Mean imp. |

Median imp. |

Min. imp |

Max. imp |

Norm hits |

Decision |

| P1. SES | 6.075 | 6.164 | 0.851 | 14.483 | 0.657 | Tentative |

| P2. MNK | 0.301 | 0.181 | -1.263 | 2.455 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P4. Wasting | 24.503 | 26.458 | 6.830 | 36.536 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P5. Underweight | 62.803 | 67.701 | 31.805 | 76.340 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P6. Child gender | 3.912 | 3.412 | -2.931 | 12.018 | 0.465 | Tentative |

| P7. Health assurance | -1.720 | -1.764 | -2.786 | -0.243 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P8. Mother’s age | 0.388 | 0.618 | -1.079 | 1.977 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P9. Family size | -0.382 | -0.413 | -2.300 | 1.840 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P10. Under-five sibling | -0.475 | -1.004 | -1.650 | 1.117 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P11.Exclusive BF | 0.198 | 0.179 | -1.073 | 1.593 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P12.Ever BF | -0.052 | 0.467 | -3.014 | 1.290 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P13. Initiation BF | -0.645 | -0.272 | -2.602 | 0.507 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P14.Weaning practices | 0.387 | 0.918 | -1.929 | 2.606 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P15.Mother education | 1.549 | 1.685 | -1.023 | 3.082 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P16.Mother employment | -1.570 | -1.425 | -3.790 | 1.211 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P17.Family income | 0.708 | 0.473 | -2.582 | 6.074 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| P18.Car Ownership | -0.356 | -0.050 | -1.767 | 2.084 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P19.House Ownership | 0.820 | 1.075 | -3.153 | 4.024 | 0.030 | Rejected |

| P20.Perceived quality of life | 2.819 | 2.993 | -4.321 | 11.632 | 0.374 | Tentative |

|

Code Variables |

Mean imp. |

Median imp. |

Min. imp |

Max. imp. |

Norm hits |

Decision |

| P1. SES | 6.697 | 6.900 | 0.396 | 10.973 | 0.919 | Confirmed |

| P3. MNK | -0.335 | -0.504 | -1.859 | 2.062 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P3. Stunting | 18.184 | 18.585 | 9.927 | 26.268 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P5. Underweight | 57.893 | 59.973 | 41.257 | 68.979 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P6. Child gender | -0.149 | -0.605 | -2.343 | 2.689 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P7. Health assurance | 0.476 | 0.419 | -1.494 | 2.018 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P8. Mother’s age | 6.144 | 5.829 | 0.292 | 11.605 | 0.889 | Confirmed |

| P9. Family size | 1.704 | 1.821 | -2.435 | 5.220 | 0.131 | Rejected |

| P10. Under-five sibling | -1.388 | -1.436 | -2.333 | -0.468 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P11.Exclusive BF | 0.374 | 0.313 | -2.203 | 2.160 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P12.Ever BF | -0.722 | -0.460 | -2.129 | 0.352 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P13. Initiation BF | 1.491 | 1.604 | -1.751 | 3.483 | 0.030 | Rejected |

| P14.Weaning practices | 1.546 | 1.626 | -0.469 | 3.599 | 0.040 | Rejected |

| P15.Mother education | 3.604 | 3.399 | -2.304 | 9.878 | 0.545 | Confirmed |

| P16. Mother employment | 0.775 | 0.370 | -1.026 | 3.781 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| P17.Family income | 2.509 | 2.552 | -2.512 | 6.517 | 0.465 | Tentative |

| P18.Car Ownership | 1.872 | 1.729 | -0.770 | 5.997 | 0.081 | Rejected |

| P19.House Ownership | 4.088 | 3.901 | -0.468 | 11.262 | 0.566 | Tentative |

| P20.Perceived quality of life | -0.125 | -0.535 | -1.265 | 2.428 | 0.000 | Rejected |

|

Code Variables |

Mean imp. |

Median imp. |

Min. imp |

Max. imp |

Norm hits |

Decision |

| P1. SES | 1.184 | 1.103 | -0.395 | 3.958 | 0.020 | Rejected |

| P2. MNK | 0.024 | -0.150 | -3.965 | 2.393 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P3. Stunting | 40.846 | 42.037 | 28.338 | 48.492 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P4. Wasting | 65.480 | 67.689 | 44.840 | 74.953 | 1.000 | Confirmed |

| P6. Child gender | 0.033 | 0.158 | -1.773 | 1.959 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P7. Health assurance | -1.061 | -0.986 | -2.302 | 0.035 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P8. Mother’s age | 3.003 | 3.227 | -2.405 | 9.000 | 0.444 | Tentative |

| P9. Family size | 1.713 | 1.838 | -1.642 | 5.277 | 0.131 | Rejected |

| P10. Under-five sibling | -0.146 | -0.225 | -1.900 | 1.331 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P11.Exclusive BF | 3.086 | 2.995 | -1.604 | 8.378 | 0.465 | Tentative |

| P12.Ever BF | -0.969 | -1.004 | -2.206 | 0.412 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P13. Initiation BF | 0.165 | 0.403 | -2.381 | 2.601 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P14.Weaning practices | 7.546 | 7.621 | 0.878 | 19.141 | 0.869 | Confirmed |

| P15.Mother education | 0.785 | 0.952 | -1.683 | 2.981 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P16.Mother employment | 1.233 | 1.422 | -1.576 | 2.680 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P17.Family income | 1.032 | 1.137 | -2.124 | 3.358 | 0.010 | Rejected |

| P18.Car Ownership | 0.085 | 0.109 | -1.864 | 1.676 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P19.House Ownership | -0.783 | -0.622 | -2.573 | 0.187 | 0.000 | Rejected |

| P20.Perceived quality of life | 3.578 | 3.490 | -1.337 | 10.594 | 0.465 | Tentative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).