Submitted:

16 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

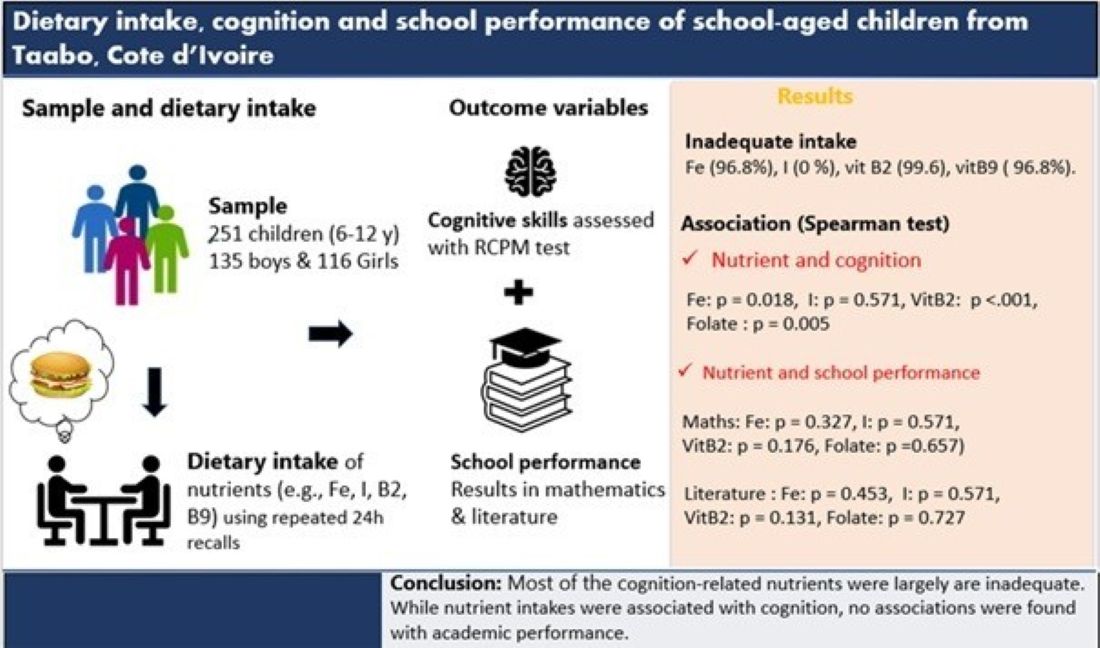

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

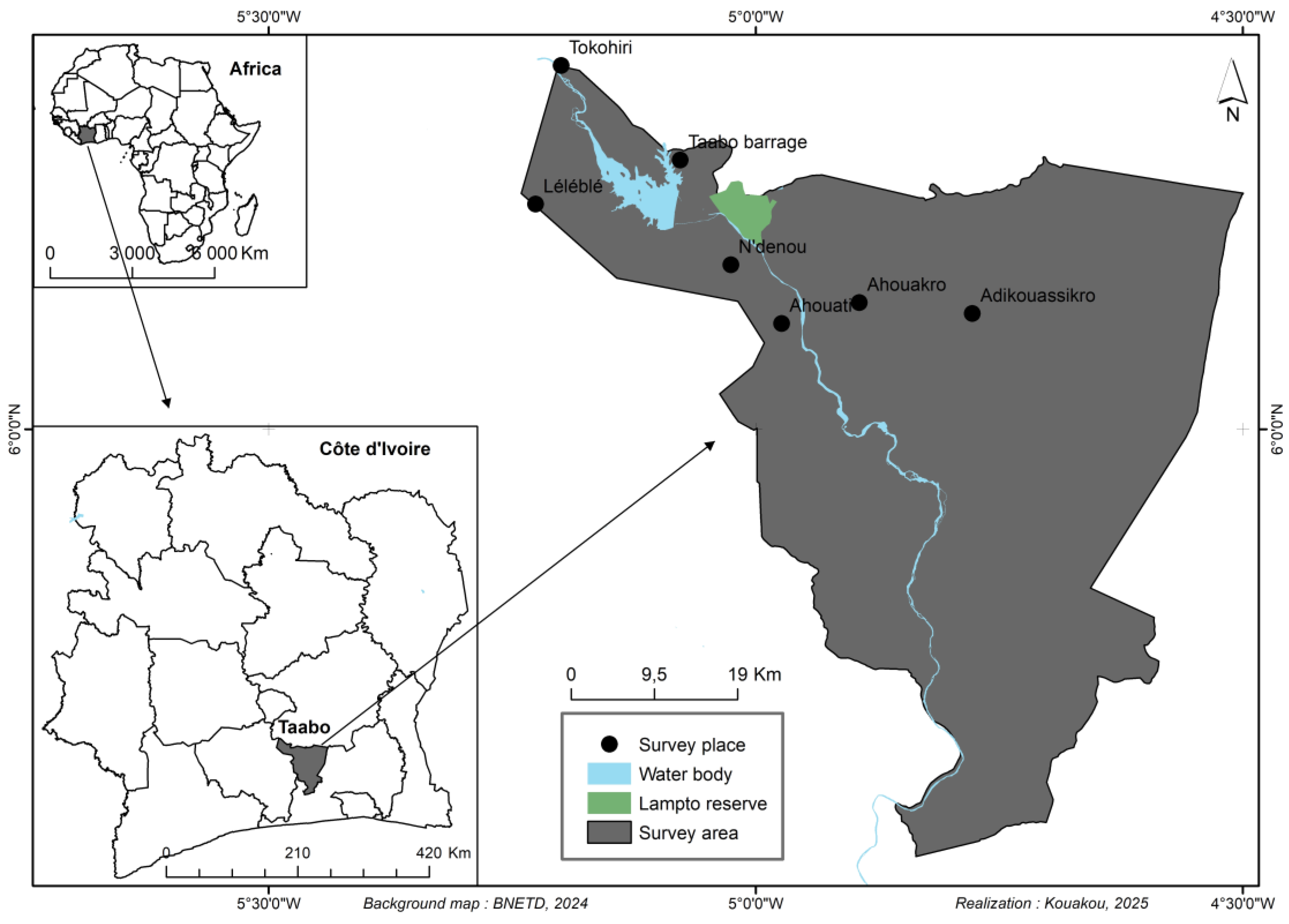

2.1. Study Design and Area

2.2. Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Sociodemographics and Anthropometrics

2.5. Dietary Intake Assessment

2.6. Cognitive Skills Assessment

2.7. Academic Performance Assessment

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

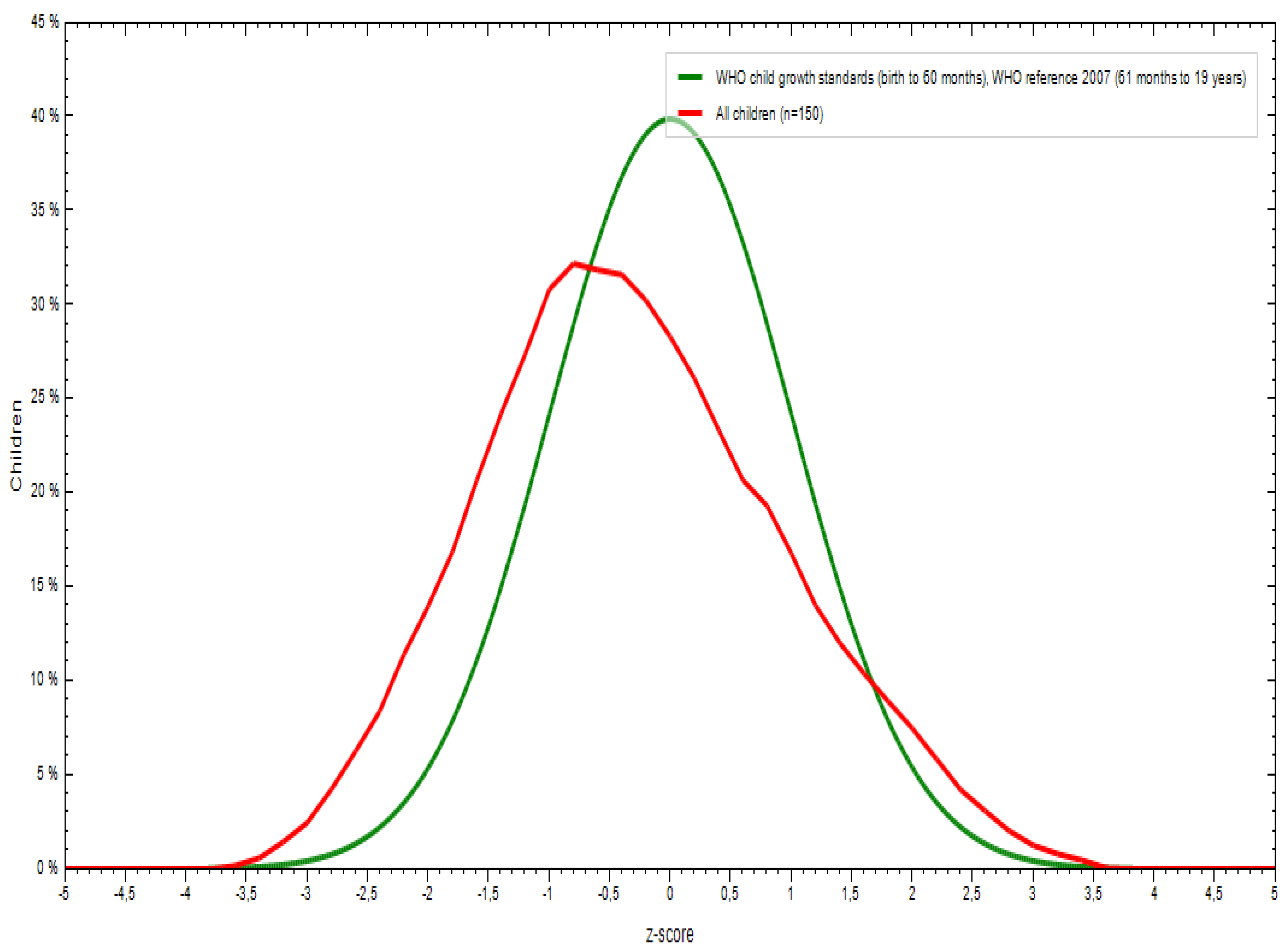

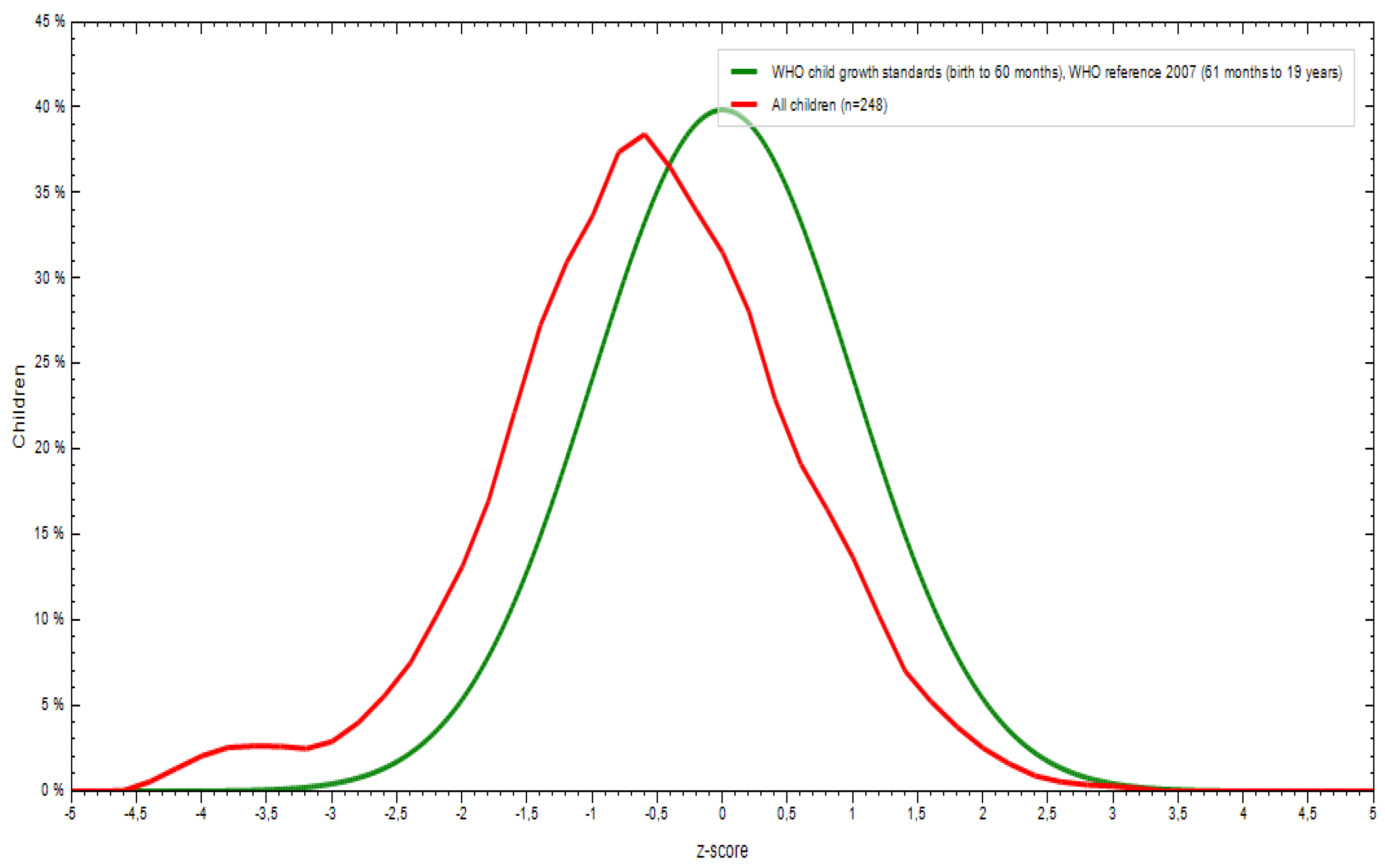

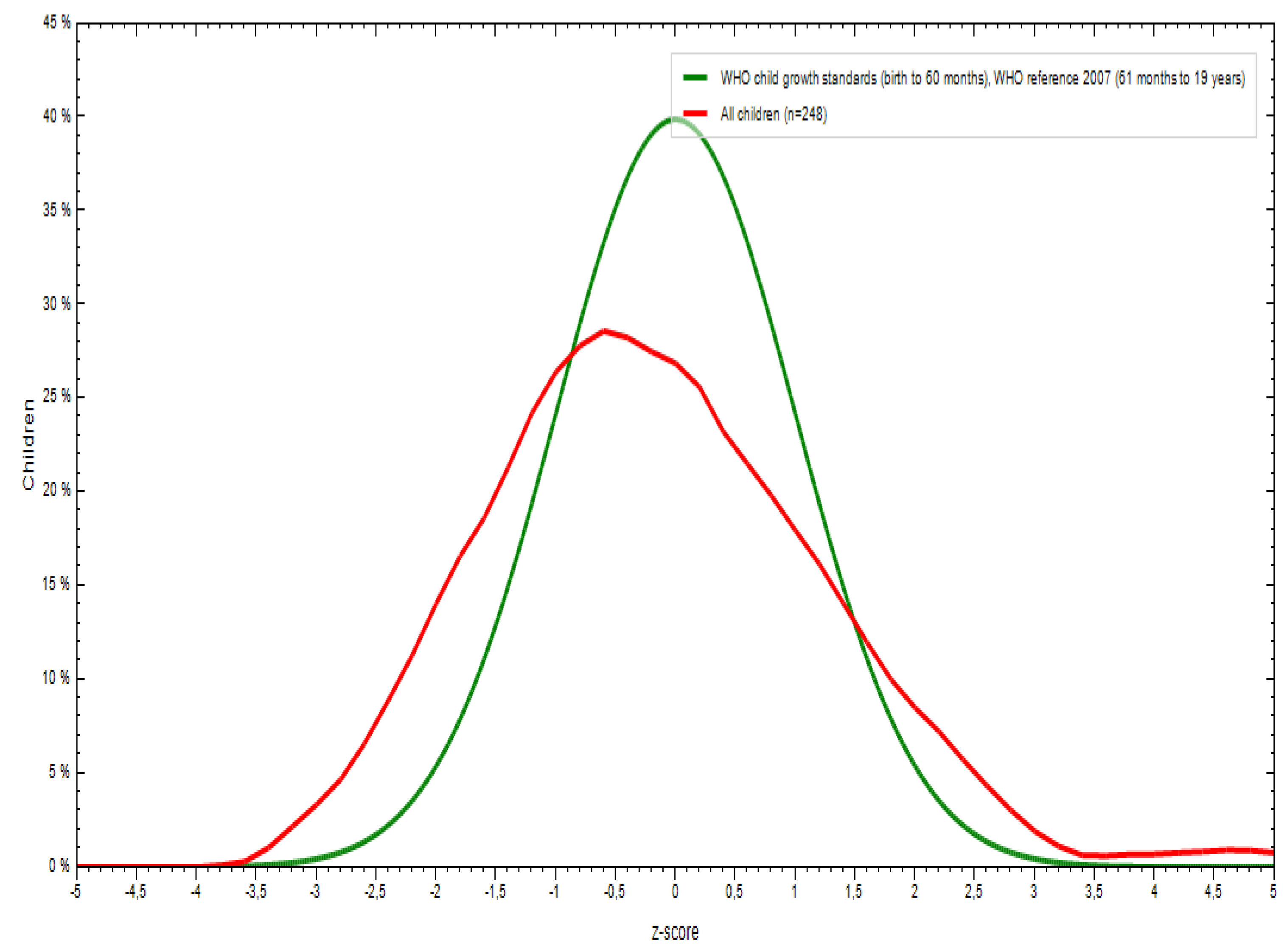

3.1. Sociodemographic and Anthropometric Characteristics

3.2. Cognitive and School Performance

3.3. Cognitive and Academic Performance by Sociodemographic and Anthropometric Characteristics

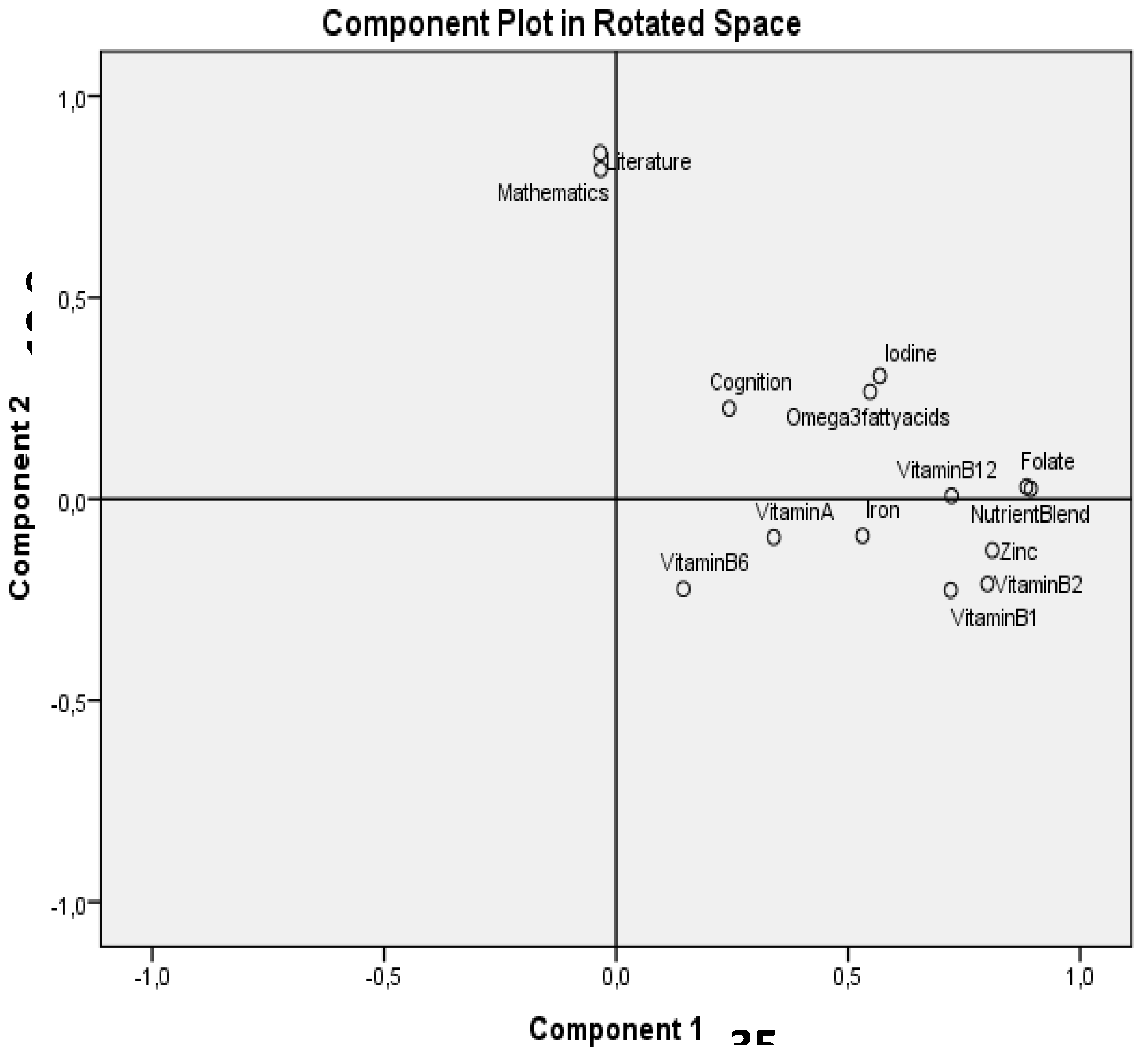

3.4. Associations Between Nutrient Intake and Cognitive or Academic Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Mean | Std. Deviation | 95% CI Mean Upper | 95% CI Mean Lower | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight for age | -0.32 | 1.04 | -0.17 | -0.46 | -2.87 | 2.77 |

| Height for age | -0.20 | 1.64 | 0.01 | -0.40 | -13.43 | 5.37 |

| BMI for age | -0.44 | 2.78 | -0.09 | -0.78 | -3.89 | 39.61 |

| Variable | Frequency N (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | ± | SD | High | Medium | Low | |

| Cognition | 15.4 | ± | 4.4 | 65 (25.9) | 77 (30.7) | 109 (43.4) |

| Mathematics | 6.0 | ± | 2.4 | 67 (26.7) | 111 (44.2) | 73 (29.1) |

| Literature | 5.4 | ± | 1.8 | 39 (15.5) | 120 (47.8) | 92 (36.7) |

| Variable | Cognition test score | Mathematics | Literature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rho | p-value | rho | p-value | rho | p-value | |

| Vitamin A (µg) | 0.059 | 0.353 | -0.112 | 0.059 | -0.112 | 0.076 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.227** | <.001 | -0.157* | 0.013 | -0.127* | 0.045 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.248** | <.001 | -0.086 | 0.176 | -0.096 | 0.131 |

| Folate (µg) | 0.179** | 0.005 | -0.028 | 0.657 | -0.022 | 0.727 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 0.065 | 0.308 | -0.019 | 0.767 | -0.060 | 0.345 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | -0.014 | 0.823 | -0.017 | 0.785 | -0.026 | 0.680 |

| Iron (mg) | 0.150* | 0.018 | -0.062 | 0.327 | -0.048 | 0.453 |

| Zinc (mg) | 0.118 | 0.062 | -0.050 | 0.433 | -0.081 | 0.200 |

| Iodine (µg) | 0.036 | 0.571 | -0.044 | 0.492 | 0.031 | 0.620 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | 0.009 | 0.881 | -0.053 | 0.400 | -0.055 | 0.382 |

| Nutrient blend | 0.181** | 0.004 | -0.029 | 0.653 | -0.025 | 0.695 |

References

- Collins, W.A. School And Children: The Middle Childhood Years. In Development During Middle Childhood: The Years From Six to Twelve; National Academies Press (US), 1984.

- Monti, J.M.; Moulton, C.J.; Cohen, N.J. The Role of Nutrition on Cognition and Brain Health in Ageing: A Targeted Approach. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2015, 28, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, S.; Rabinovitz, S.; Mostofsky, D.I. Nutritional Deficiencies in Learning and Cognition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2006, 43, S22–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantey, A.A.; Annan, R.A.; Lutterodt, H.E.; Twumasi, P. Iron Status Predicts Cognitive Test Performance of Primary School Children from Kumasi, Ghana. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0251335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pinilla, F. Brain Foods: The Effects of Nutrients on Brain Function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, J.B.; Wallace, J.E.; Dinsmore, K.; Lewin, A.M.; Ghali, W.A.; Roberts, D. Physician Nutrition and Cognition during Work Hours: Effect of a Nutrition Based Intervention. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, S.H. Importance of Methyl Donors during Reproduction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 673S–677S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchardt, J.P.; Schneider, I.; Meyer, H.; Neubronner, J.; von Schacky, C.; Hahn, A. Incorporation of EPA and DHA into Plasma Phospholipids in Response to Different Omega-3 Fatty Acid Formulations - a Comparative Bioavailability Study of Fish Oil vs. Krill Oil. Lipids Health Dis. 2011, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.J. The Importance of Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Behaviour, Cognition and Mood. Scand. J. Nutr. 2003, 47, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassek, W.D.; Gaulin, S.J.C. Sex Differences in the Relationship of Dietary Fatty Acids to Cognitive Measures in American Children. Front. Evol. Neurosci. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.M.; Phiri, K.S.; Pasricha, S.-R. Iron and Cognitive Development: What Is the Evidence? Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 71, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkingham, M.; Abdelhamid, A.; Curtis, P.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Dye, L.; Hooper, L. The Effects of Oral Iron Supplementation on Cognition in Older Children and Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Taneja, S. Zinc and Cognitive Development. Br. J. Nutr. 2001, 85, S139–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.M. The Evidence Linking Zinc Deficiency with Children’s Cognitive and Motor Functioning. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1473S–1476S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura, J.E.; De Moura, E.N.O.; Alves, C.X.; De Lima Vale, S.H.; Dantas, M.M.G.; De Araújo Silva, A.; Das Graças Almeida, M.; Leite, L.D.; Brandão-Neto, J. Oral Zinc Supplementation May Improve Cognitive Function in Schoolchildren. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2013, 155, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.S.; Vanderkooy, P.D.; MacDonald, A.C.; Goldman, A.; Ryan, Ba.; Berry, M. A Growth-Limiting, Mild Zinc-Deficiency Syndrome in Some Southern Ontario Boys with Low Height Percentiles. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989, 49, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS WHO Global Database on Iodine Deficiency. WHO Geneva 2004.

- DeLong, G.R.; Stanbury, J.B.; Fierro-Benitez, R. Neurological Signs in Congenital Iodine-Deficiency Disorder (Endemic Cretinism). Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1985, 27, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Connolly, K.; Bozo, M.; Bridson, J.; Rohner, F.; Grimci, L. Iodine Supplementation Improves Cognition in Iodine-Deficient Schoolchildren in Albania: A Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Pisklak, D.M.; Grodner, B. Thiamine and Thiamine Pyrophosphate as Non-Competitive Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase—Experimental and Theoretical Investigations. Molecules 2025, 30, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaadi, A.M.; Devlin, A.M.; Green, T.J. Riboflavin Intake and Status and Relationship to Anemia. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 81, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naninck, E.F.G.; Stijger, P.C.; Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M. The Importance of Maternal Folate Status for Brain Development and Function of Offspring. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, N.; England-Mason, G.; Field, C.J.; Dewey, D.; Aghajafari, F. Prenatal Folate and Choline Levels and Brain and Cognitive Development in Children: A Critical Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takle, M.; Sahjwani, D.; Bharucha-Goebel, D.; Rapp, T.; Bouska, C.; Kornbluh, A.; Sen, K. Pyridoxal Phosphate Binding Protein (PLPBP) Deficiency Mimicking Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia Syndrome. Ann. Child Neurol. Soc. 2025, 3, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, Y.; Cao, X.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Jiang, H. Lower Water-Soluble Vitamins and Higher Homocysteine Levels Contribute to Cognitive Decline in Patients with Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Retrospective Case-Control Study 2024.

- Rathod, R.; Kale, A.; Joshi, S. Novel Insights into the Effect of Vitamin B12 and Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Brain Function. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.; Mander, A.; Ames, D.; Carne, R.; Sanders, K.; Watters, D. Cognitive Impairment and Vitamin B12: A Review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, T.A.; Taneja, S.; Ueland, P.M.; Refsum, H.; Bahl, R.; Schneede, J.; Sommerfelt, H.; Bhandari, N. Cobalamin and Folate Status Predicts Mental Development Scores in North Indian Children 12–18 Mo of Age. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Hamadani, J.; Mehra, S.; Tofail, F.; Hasan, M.I.; Shaikh, S.; Shamim, A.A.; Wu, L.S.; West Jr, K.P.; Christian, P. Effect of Maternal Antenatal and Newborn Supplementation with Vitamin A on Cognitive Development of School-Aged Children in Rural Bangladesh: A Follow-up of a Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutema, B.T.; Levecke, B.; Sorrie, M.B.; Megersa, N.D.; Zewdie, T.H.; Yesera, G.E.; De Henauw, S.; Abubakar, A.; Abbeddou, S. Effectiveness of Intermittent Iron and High-Dose Vitamin A Supplementation on Cognitive Development of School Children in Southern Ethiopia: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, G.J.; Murray-Kolb, L.E.; Khatry, S.K.; LeClerq, S.C.; Wu, L.; West, K.P.; Christian, P. Cognitive and Motor Skills in School-Aged Children Following Maternal Vitamin A Supplementation during Pregnancy in Rural Nepal: A Follow-up of a Placebo-Controlled, Randomised Cohort. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asobayire, F.S.; Adou, P.; Davidsson, L.; Cook, J.D.; Hurrell, R.F. Prevalence of Iron Deficiency with and without Concurrent Anemia in Population Groups with High Prevalences of Malaria and Other Infections: A Study in Cote d’Ivoire. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righetti, A.A. Aetiology of Anaemia and Public Health Implications in the Taabo Health Demographic Surveillance System, South-Central Côte d’Ivoire. PhD Thesis, University_of_Basel, 2014.

- Yapi, H.F.; Ahiboh, H.; Ago, K.; Aké, M.; Monnet, D. Profil Protéique et Vitamine A Chez l’enfant d’âge Scolaire En Côte d’Ivoire. Ann. Biol. Clin. (Paris) 2005, 63, 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Fifi, T.M.; Sylvère, Z.K.Y.A.; Fossou, A.F.; Bitty, M.L.A.; Séraphin, K.-C. Assessment of the Nutritional Status of Schoolchildren in the Commune of Abobo. 2023.

- YAPO, P. Nutritional Status, Sociodemographic Status and Academic Performance of Students in Two Selected Secondary Schools in Yopougon, Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire). Age 2018, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, S.; Baikoro, N.; N’Guessan, Y.; Jaeger, F.N.; Silué, K.D.; Fürst, T.; Hürlimann, E.; Ouattara, M.; Séka, M.-C.Y.; N’Guessan, N.A.; et al. Health & Demographic Surveillance System Profile: The Taabo Health and Demographic Surveillance System, Côte d’Ivoire. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diomande, M.; Dongo, K.; Dje, K.B.; Kouadio, K.K.H.; Kone, D.; Biemi, J.; Bonfoh, B. Vers Un Changement Du Calendrier Cultural Dans l’ecotone Foret-Savane de La Côte D’Ivoire. Agron. Afr. 2013, 25, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- INS Institut National de la Statistique (INS). (2021). Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat. Accès : Revue Internationale du Chercheur (PDF disponible). Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?q=Institut+National+de+la+Statistique+%28INS%29.+%282021%29Recensement+Général+de+la+Population+et+de+l’Habitat.+Accès+%3A+Revue+Internationale+du+Chercheur+%28PDF+disponible%29&form=ANNH01&refig=a69505812a6744f8a0e2554f682ee367&pc=U531 (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- World Health Organization Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio : Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, Geneva, 8-11 December 2008. 2011.

- WHO Growth Reference 5-19 Years - Application Tools. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/application-tools (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Mantey, A.A.; Annan, R.A.; Lutterodt, H.E.; Twumasi, P. Iron Status Predicts Cognitive Test Performance of Primary School Children from Kumasi, Ghana. Plos One 2021, 16, e0251335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onis, M. de; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; Siyam, A.; Nishida, C.; Siekmann, J. Development of a WHO Growth Reference for School-Aged Children and Adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.S.; Ferguson, E.L. An Interactive 24-Hour Recall for Assessing the Adequacy of Iron and Zinc Intakes in Developing Countries. 2008.

- Anderegg, S.C. Evaluation and Interpretation of a Three-Day Weighed Food Record from South-Central Côte d’Ivoire with a Focus on Iron Intake and Absorption. Thesis, ETH Zurich, 2008.

- WHO/FAO, F.A.O. Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition. 2004.

- EFSA Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Fats, Including Saturated Fatty Acids, Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, Monounsaturated Fatty Acids, Trans Fatty Acids, and Cholesterol. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1461. [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.C. Guide to Using the Coloured Progressive Matrices; Guide to using the Coloured Progressive Matrices; H. K. Lewis & Co.: Oxford, England, 1958; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalew, M.; Bayray, A.; Bekele, A.; Handebo, S. Nutritional Status and Educational Performance of School-Aged Children in Lalibela Town Primary Schools, Northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Pediatr. 2020, 2020, e5956732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateillah, K.; Aboussaleh, Y.; Sbaibi, R.; Ahami, A.O.T. Évaluation Anthropométrique et Son Impact Sur La Performance Scolaire Des Lycéens de La Commune Urbaine Kenitra (Nord-Ouest Marocain). Antropo 2018, 39, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Toffoli, L.; Stefanelli, G.; Manca, G.; Del Popolo Cristaldi, F.; Duma, G.M.; Guidi, M.; Incagli, F.; Sbernini, L.; Tarantino, V.; Mento, G. Adaptive Cognitive Control in 4 to 7-Year-Old Children and Potential Effects of School-Based Yoga-Mindfulness Interventions: An Exploratory Study in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Burrows, P.; Burrows, R.; Blanco, E.; Reyes, M.; Gahagan, S. Nutritional Quality of Diet and Academic Performance in Chilean Students. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, D.; Nigatu, D.; Gashaw, K.; Demelash, H. Height for Age z Score and Cognitive Function Are Associated with Academic Performance among School Children Aged 8–11 Years Old. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, H. Nutrition and Student Performance at School. J. Sch. Health 2005, 75, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiweiss-Sande, R.; Chui, K.; Wright, C.; Amin, S.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Sacheck, J.M. Associations between Food Group Intake, Cognition, and Academic Achievement in Elementary Schoolchildren. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleyere, M.N.; Kokore, B.A.; Konan, A.B.; Yapo, P.A. Prevalence of Child Malnutrition through Their Anthropometric Indices in School Canteens of Abidjan (Côte D’ivoire). Pak. J. Nutr. 2013, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hürlimann, E.; Yapi, R.B.; Houngbedji, C.A.; Schmidlin, T.; Kouadio, B.A.; Silué, K.D.; Ouattara, M.; N’Goran, E.K.; Utzinger, J.; Raso, G. The Epidemiology of Polyparasitism and Implications for Morbidity in Two Rural Communities of Côte d’Ivoire. Parasit. Vectors 2014, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akombi, B.J.; Agho, K.E.; Merom, D.; Renzaho, A.M.; Hall, J.J. Child malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-analysis of demographic and health surveys (2006-2016). PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0177338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham-McGregor, S. A Review of Studies of the Effect of Severe Malnutrition on Mental Development. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 2233S–2238S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmare, B.; Taddele, M.; Berihun, S.; Wagnew, F. Nutritional Status and Correlation with Academic Performance among Primary School Children, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Khokhlov; Slovenko, Neuropsychological Predictors of Poor School Performance. Available online: https://typeset.io/papers/neuropsychological-predictors-of-poor-school-performance-2i5wq0ac71 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Petry, N.; Olofin, I.; Hurrell, R.; Boy, E.; Wirth, J.; Moursi, M.; Donahue Angel, M.; Rohner, F. The Proportion of Anemia Associated with Iron Deficiency in Low, Medium, and High Human Development Index Countries: A Systematic Analysis of National Surveys. Nutrients 2016, 8, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, J.; Petry, N.; Tanumihardjo, S.; Rogers, L.; McLean, E.; Greig, A.; Garrett, G.; Klemm, R.; Rohner, F. Vitamin A Supplementation Programs and Country-Level Evidence of Vitamin A Deficiency. Nutrients 2017, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham-McGregor, S.; Cheung, Y.B.; Cueto, S.; Glewwe, P.; Richter, L.; Strupp, B. Developmental Potential in the First 5 Years for Children in Developing Countries. The Lancet 2007, 369, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GAIN Iodine Deficiency in Côte d’Ivoire: Achievements and Remaining Challenges. Geneva: GAIN 2007.

- Tia, A.; Hauser, J.; Konan, A.G.; Ciclet, O.; Grzywinski, Y.; Mainardi, F.; Visconti, G.; Frézal, A.; Nindjin, C. Unravelling the Relationship between Nutritional Status and Cognitive and School Performance among School-Aged Children in Taabo, Côte d’Ivoire: A School-Based Observational Study. Front Nutr manuscript under revision.

- Gewa, C.A.; Weiss, R.E.; Bwibo, N.O.; Whaley, S.; Sigman, M.; Murphy, S.P.; Harrison, G.; Neumann, C.G. Dietary Micronutrients Are Associated with Higher Cognitive Function Gains among Primary School Children in Rural Kenya. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 1378–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, W.; Lei, C.; Lee, S.; Gang, G.; Shin, M.; Kim, J.; et al. Modified Korean MIND Diet: A Nutritional Intervention for Improved Cognitive Function in Elderly Women through Mitochondrial Respiration, Inflammation Suppression, and Amino Acid Metabolism Regulation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, 2300329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, R.A.; Apprey, C.; Asamoah-Boakye, O.; Okonogi, S.; Yamauchi, T.; Sakurai, T. The Relationship between Dietary Micronutrients Intake and Cognition Test Performance among School-Aged Children in Government-Owned Primary Schools in Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3042–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J. How Energy Supports Our Brain to Yield Consciousness: Insights From Neuroimaging Based on the Neuroenergetics Hypothesis. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.L. Iron Biology in Immune Function, Muscle Metabolism and Neuronal Functioning. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 568S–580S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, J.P.T.; Mey, J. Editorial: The Role of Retinoic Acid Signaling in Maintenance and Regeneration of the CNS: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, R.F. Thiamin Deficiency and Brain Disorders. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2003, 16, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, H.J. Riboflavin (Vitamin B-2) and Health12. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crider, K.S.; Yang, T.P.; Berry, R.J.; Bailey, L.B. Folate and DNA Methylation: A Review of Molecular Mechanisms and the Evidence for Folate’s Role. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocchegiani, E.; Romeo, J.; Malavolta, M.; Costarelli, L.; Giacconi, R.; Diaz, L.-E.; Marcos, A. Zinc: Dietary Intake and Impact of Supplementation on Immune Function in Elderly. AGE 2013, 35, 839–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutema, B.T.; Levecke, B.; Sorrie, M.B.; Megersa, N.D.; Zewdie, T.H.; Yesera, G.E.; De Henauw, S.; Abubakar, A.; Abbeddou, S. Effectiveness of Intermittent Iron and High-Dose Vitamin A Supplementation on Cognitive Development of School Children in Southern Ethiopia: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, C.K.; Cannavale, C.N.; Khan, N.A. Nutrition and Neurodevelopment: From Early Life Through Adolescence. In The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Enhancement and Brain Plasticity; Oxford University Press, 2025; ISBN 978-0-19-767713-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, J.; Smuts, C.M.; Malan, L.; Kvalsvig, J.; van Stuijvenberg, M.E.; Hurrell, R.F.; Zimmermann, M.B. Effects of Iron and N-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation, Alone and in Combination, on Cognition in School Children: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Intervention in South Africa1234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Briel, T.; West, C.E.; Bleichrodt, N.; van de Vijver, F.J.; Ategbo, E.A.; Hautvast, J.G. Improved Iodine Status Is Associated with Improved Mental Performance of Schoolchildren in Benin123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okai-Mensah, P.; Brkić, D.; Hauser, J. The Importance of Lipids for Neurodevelopment in Low and Middle Income Countries. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangirana, P.; Menk, J.; John, C.C.; Boivin, M.J.; Hodges, J.S. The Association between Cognition and Academic Performance in Ugandan Children Surviving Malaria with Neurological Involvement. PloS One 2013, 8, e55653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile Height for Age z Score and Cognitive Function Are Associated with Academic Performance among School Children Aged 8–11 Years Old. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 17–17. [CrossRef]

- Molteno, G. Intellectual, Cognitive and Academic Outcomes of Very Low Birth Weight Adolescents Living in Disadvantaged Communities. PhD Thesis, Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University, 2004.

| Variable | Cognition | Mathematics | Literature | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Mean | ± | SD | p-value | Mean | ± | SD | p-value | Mean | ± | SD | p-value | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 116 | 46.2 | 14.9 | ± | 4.5 a | 0.046* | 5.9 | ± | 2.3 | 0.807* | 5.5 | ± | 1.8 | 0.624* |

| Male | 135 | 53.8 | 15.8 | ± | 4.3 b | 6.0 | ± | 2.4 | 5.4 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Age | ||||||||||||||

| 6-8 years | 88 | 35.1 | 13.1 | ± | 2.7 b | < .001 | 6.8 | ± | 2.8a | < .001 | 5.9 | ± | 1.9a | 0.002 |

| 9-10 years | 76 | 30.3 | 15.9 | ± | 4.9 a | 5.4 | ± | 2.1b | 5.4 | ± | 1.8ab | |||

| 11-12 years | 87 | 34.7 | 17.1 | ± | 4.4 a | 5.6 | ± | 1.9b | 5.0 | ± | 1.6b | |||

| Absence in class | ||||||||||||||

| Never | 70 | 27.9 | 15.5 | ± | 4.9 | 0.807 | 6.0 | ± | 2.6 | 0.516 | 5.5 | ± | 2.0 | 0.874 |

| 1-3 days | 157 | 62.5 | 15.3 | ± | 4.2 | 6.0 | ± | 2.2 | 5.4 | ± | 1.7 | |||

| More than 3 days | 24 | 9.6 | 15.6 | ± | 3.8 | 5.4 | ± | 2.4 | 5.3 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Grade repetition | ||||||||||||||

| Never | 141 | 56.2 | 15.3 | ± | 4.3 | 0.753 | 6.0 | ± | 2.5 | 0.114 | 5.7 | ± | 1.9a | 0.04 |

| Once | 87 | 34.7 | 15.2 | ± | 3.9 | 6.1 | ± | 2.1 | 5.2 | ± | 1.6a | |||

| More than once | 23 | 9.2 | 16.5 | ± | 6.1 | 5.1 | ± | 2.2 | 4.9 | ± | 1.6a | |||

| Household size | ||||||||||||||

| Small (≤5) | 49 | 19.5 | 15.7 | ± | 5.0 | 0.953* | 6.1 | ± | 2.3 | 0.682* | 5.6 | ± | 1.9 | 0.692* |

| Large (> 5) | 202 | 80. | 15.3 | ± | 4.2 | 5.9 | ± | 2.4 | 5.4 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Duration (min) | ||||||||||||||

| Short (≤ 30 min) | 7 | 2.8 | 13.9 | ± | 2.3 | 0.284 | 6.6 | ± | 2.9 | 0.720 | 5.0 | ± | 1.6 | 0.284 |

| Medium (30-60 min) | 226 | 90.0 | 15.3 | ± | 4.3 | 5.9 | ± | 2.4 | 5.4 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Long (≥ 60 min) | 18 | 7.2 | 17.1 | ± | 5.4 | 6.2 | ± | 1.5 | 5.8 | ± | 1.6 | |||

| School canteen | ||||||||||||||

| No | 69 | 27.5 | 14.8 | ± | 4.4 | 0.085* | 5.8 | ± | 2.6 | 0.962 | 5.5 | ± | 2.1 | 0.966 |

| Yes | 182 | 72.5 | 15.6 | ± | 4.4 | 6.0 | ± | 2.3 | 5.4 | ± | 1.7 | |||

| Live with parents | ||||||||||||||

| No | 7 | 2.8 | 15.3 | ± | 4.6 | 0.930* | 4.8 | ± | 1.9 | 0.194* | 4.9 | ± | 1.1 | 0.534* |

| Yes | 244 | 97.2 | 15.4 | ± | 4.4 | 6.0 | ± | 2.4 | 5.4 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Mother’s occupation | ||||||||||||||

| Tertiary sector | 24 | 9.6 | 15.9 | ± | 4.8 | 0.566* | 6.2 | ± | 2.3 | 0.680* | 5.4 | ± | 1.8 | 0.664* |

| Housewife | 227 | 90.4 | 15.3 | ± | 4.3 | 5.9 | ± | 2.4 | 5.4 | ± | 1.9 | |||

| Mother’s education | ||||||||||||||

| Higher | 5 | 2.0 | 17.8 | ± | 7. 1a | 0.018 | 5.7 | ± | 1.2 | 0.419 | 5.8 | ± | 1.6 | 0.619 |

| Illiterate | 114 | 45.4 | 14.6 | ± | 4.2a | 6.1 | ± | 2.4 | 5.4 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Primary | 88 | 35.1 | 15.8 | ± | 4.3 a | 5.7 | ± | 2.4 | 5.3 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Secondary | 44 | 17.5 | 16.3 | ± | 4.3 a | 6.1 | ± | 2.2 | 5.8 | ± | 1.9 | |||

| Father’s occupation | ||||||||||||||

| Primary sector | 200 | 79.7 | 15.2 | ± | 4.5 | 0.272 | 6.0 | ± | 2.4 | 0.322 | 5.4 | ± | 1.8a | 0.023 |

| Secondary sector | 10 | 4.0 | 16.2 | ± | 5.2 | 4.9 | ± | 2.4 | 4.3 | ± | 1.2a | |||

| Tertiary sector | 41 | 16.3 | 15.8 | ± | 3.5 | 6.2 | ± | 2.3 | 5.9 | ± | 1.7b | |||

| Father's education | ||||||||||||||

| Higher | 21 | 8.4 | 16.2 | ± | 4.5 | 0.575 | 6.3 | ± | 2.3 | 0.688 | 5.9 | ± | 1.7 | 0.094 |

| Illiterate | 65 | 25.9 | 15.0 | ± | 4.5 | 6.1 | ± | 2.5 | 5.4 | ± | 1.7 | |||

| Primary | 102 | 40.6 | 15.2 | ± | 4.4 | 5.8 | ± | 2.4 | 5.1 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Secondary | 63 | 25.1 | 15.8 | ± | 4.3 | 6.0 | ± | 2.3 | 5.8 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| School grade | ||||||||||||||

| Grade 1 | 42 | 16.7 | 13.0 | ± | 2.0 b | < .001 | 6.8 | ± | 3.2a | < .001 | 5.9 | ± | 2.0ab | 0.004 |

| Grade 2 | 42 | 16.7 | 12.6 | ± | 2.4 b | 6.8 | ± | 2.4ab | 5.9 | ± | 1.2a | |||

| Grade 3 | 42 | 16.7 | 14.5 | ± | 3.3 b | 5.0 | ± | 2.1c | 4.9 | ± | 1.9b | |||

| Grade 4 | 41 | 16.3 | 16.1 | ± | 4.2 a | 5.2 | ± | 2.1b | 5.0 | ± | 1.6b | |||

| Grade 5 | 42 | 16.7 | 18.1 | ± | 5.5 a | 5.8 | ± | 1.7ab | 5.3 | ± | 2.0ab | |||

| Grade 6 | 42 | 16.7 | 18.0 | ± | 4.4 a | 6.3 | ± | 1.8ab | 5.5 | ± | 1.7ab | |||

| Weight for age | ||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 11 | 8.8 | 13.1 | ± | 1.7 | 0.226 | 4.7 | ± | 3.0a | 0.035 | 5.3 | ± | 1.8 | 0.562 |

| Normal | 235 | 90.8 | 15.5 | ± | 4.4 | 6.0 | ± | 2.3ab | 5.4 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Overweight | 5 | 0.4 | 15.7 | ± | 5.0 | 7.8 | ± | 1.4b | 5.8 | ± | 1.7 | |||

| Height for age | ||||||||||||||

| Stunting | 19 | 8.8 | 17.5 | ± | 6.0 | 0.172 | 5.6 | ± | 2.6 | 0.774 | 11.2 | ± | 3.4 | 0.188 |

| Normal | 214 | 84.9 | 15.2 | ± | 4.2 | 6.0 | ± | 2.3 | 5.5 | ± | 1.8 | |||

| Overgrowth | 18 | 0.4 | 15.8 | ± | 4.2 | 5.6 | ± | 2.4 | 4.9 | ± | 1.5 | |||

| BMI for age | ||||||||||||||

| Thinness | 23 | 9.2 | 15.9 | ± | 4.3 | 0.816 | 5.9 | ± | 2.5 | 0.976 | 5.8 | ± | 2.0 | 0.570 |

| Normal | 224 | 90 | 15.3 | ± | 4.4 | 6.0 | ± | 2.3 | 5.4 | ± | 1.7 | |||

| Overweight/Obesity | 2 | 0.8 | 17.5 | ± | 7.8 | 6.3 | ± | 2.4 | 6.4 | ± | 1.9 | |||

| Nutrient intake | Mean | ± | SD | Adequate | Inadequate | 1st tertile | 2nd tertile | 3rd tertile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Vitamin A (µg) | 1170.7 | ± | 1278.1 | 140 | 55.8 | 111 | 44.2 | 84 | 33.5 | 84 | 33.5 | 83 | 33.1 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.4 | ± | 0.2 | 2 | 0.8 | 249 | 99.2 | 98 | 39.0 | 113 | 45 | 40 | 15. 9 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.3 | ± | 0.2 | 1 | 0.4 | 250 | 99.6 | 94 | 37.5 | 112 | 44.6 | 45 | 17. 9 |

| Folic acid (µg) | 116.1 | ± | 67.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 250 | 99.6 | 84 | 33.5 | 85 | 33.9 | 82 | 32.7 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 2.6 | ± | 1.8 | 153 | 61.0 | 98 | 39. 0 | 92 | 36.7 | 77 | 30.7 | 82 | 32.7 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 3.6 | ± | 4.6 | 160 | 63.7 | 91 | 36.3 | 98 | 39.0 | 72 | 28.7 | 81 | 32.3 |

| Iron (mg) | 2.0 | ± | 1.7 | 8 | 3.2 | 242 | 96.8 | 83 | 33.1 | 85 | 33.9 | 83 | 33.1 |

| Zinc (mg) | 2.3 | ± | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 251 | 100 | 85 | 33.3 | 86 | 34.3 | 80 | 31.9 |

| Iodine (µg) | 691.1 | ± | 416.9 | 251 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 83 | 33.1 | 85 | 33.9 | 83 | 33.1 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids (g) | 0.4 | ± | 0.4 | 176 | 70.1 | 75 | 29.9 | 128 | 51.0 | 61 | 24.3 | 62 | 24.7 |

| Nutrient blend | 123.0 | ± | 69.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 84 | 33.5 | 84 | 33.5 | 83 | 33.1 |

| Cognition | Mathematics | Literature | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient intake tertile | Above75th | 50th75th | Below 50th | ꭓ2 | p | Above 7/10 | 5/10-7/10 | Below 5/10 | ꭓ2 | p | Above 7/10 | 5/10-7/10 | Below 5/10 | ꭓ2 | p | |||||||

| Vitamin A (µg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 27(32.5) | 30(36.1) | 26(31.3) | 3.4 | 0.181 | 18(21.7) | 40(48.2) | 25(30.1) | 3.6 | 0.166 | 14(16.9) | 33(39.7) | 36(43.4) | 3.0 | 0.228 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 22(26.2) | 24(28.6) | 38(45.2) | 29(34.5) | 36(42.9) | 19(22.6) | 15(51.7) | 43(56.6) | 26(41.9) | |||||||||||||

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 20(50.0) | 13(32.5) | 7(17.5) | 20.8 | < .001 | 8(20.0) | 20(50.0) | 12(30.0) | 2.5 | 0.274 | 5(12.5) | 13(32.5) | 22(55.0) | 7.9 | 0.019 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 18(18.4) | 24(24.5) | 56(57.4) | 33(33.7) | 42(42.9) | 23(23.5) | 18(18.4) | 51(52.0) | 29(29.6) | |||||||||||||

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 19(42.2) | 13(28.9) | 13(28.9) | 12.6 | 0.002 | 10(22.2) | 23(51.1) | 12(26.7) | 1.3 | 0.522 | 6(13.3) | 18(40.0) | 21(46.7) | 2.9 | 0.238 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 16(17.0) | 25(26.6) | 53(56.4) | 29(30.9) | 40(42.6) | 25(26.6) | 15(16.0) | 49(52.1) | 31(31.9) | |||||||||||||

| Folate (µg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 32(39.0) | 21(25.6) | 29(35.4) | 10.4 | 0.006 | 22(26.8) | 36(43.9) | 24(29.3) | 0.4 | 0.833 | 14(17.1) | 34(41.5) | 34(41.5) | 2.1 | 0.350 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 14(16.7) | 28(33.3) | 42(50.0) | 26(31.0) | 34(40.5) | 24(28.6) | 13(15.5) | 44(52.4) | 27(32.1) | |||||||||||||

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 23(28.0) | 23(28.0) | 36(43.9) | 0.2 | 0.886 | 22(26.8) | 37(45.1) | 23(28.0) | 0.1 | 0.977 | 13(15.9) | 38(46.3) | 31(37.8) | 0.1 | 0.964 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 23(25.0) | 41(44.6) | 28(30.4) | 26(28.3) | 41(44.6) | 25(28.3) | 16(17.4) | 42(45.7) | 34(37.0) | |||||||||||||

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 18(22.2) | 21(25.9) | 42(51.9) | 1.5 | 0.482 | 18(22.2) | 41(50.6) | 22(27.2) | 3.2 | 0.207 | 12(14.8) | 38(46.9) | 31(38.3) | 0.7 | 0.719 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 25(25.1) | 31(31.6) | 42(42. 9) | 30(30.6) | 37(37.8) | 31 (31.6) | 17(17.4) | 49(50.0) | 32(32.6) | |||||||||||||

| Iron (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 45(30.0) | 49(32.7) | 56(37.3) | 7.1 | 0.029 | 38(25.3) | 66(44.0) | 46(30.7) | 0.3 | 0.856 | 26(17.3) | 67(42.1) | 56(37.3) | 2.2 | 0.337 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 12(14.5) | 25(30.1) | 46(55.4) | 22(26.5) | 46(47.0) | 22(26.5) | 11(13.3) | 43(51.8) | 29(34.9) | |||||||||||||

| Zinc (mg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 30(37.5) | 25(31.3) | 25(41.5) | 6.8 | 0.033 | 20(25.0) | 38(47.5) | 22(27.5) | 1.2 | 0.548 | 12(15.0) | 29(36.3) | 39(48.8) | 9.7 | 0.008 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 17(20.0) | 29(34.1) | 39(45.9) | 27(31.8) | 34(40.0) | 24(28.2) | 10(11.8) | 51(60.0) | 24(28.2) | |||||||||||||

| Iodine (µg) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 26(31.3) | 24(28.9) | 33(39.8) | 1.0 | 0.605 | 20(24.1) | 38(45.8) | 25(30.1) | 2.0 | 0.366 | 10(12.0) | 45(54.2) | 28(33.7) | 2.9 | 0.236 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 21(25.3) | 29(34.9) | 33(39.8) | 28(33.7) | 35(42.2) | 20(24.1) | 17(20.5) | 36(43.4) | 30(36.1) | |||||||||||||

| Omega-3 fatty acids (g) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 20(32.3) | 13(21.0) | 64(46.8) | 4.0 | 0.133 | 16(25.8) | 26(41.9) | 20(32.3) | 0.4 | 0.816 | 7(11.3) | 31(50.0) | 24(38.7) | 1.1 | 0.567 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 45(23.8) | 64(33.9) | 80(42.3) | 51(27.0) | 85(44.9) | 53(28.0) | 32(16.9) | 89(47.1) | 68(36.0) | |||||||||||||

| Nutrient Blend | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Higher tertile | 31(37.3) | 22(26.5) | 30(36.1) | 10.3 | 0.006 | 23(27.7) | 36(43.4) | 24(28.9) | 0.3 | 0.849 | 15(18.1) | 34(41.0) | 34(41.0) | 2.2 | 0.329 | |||||||

| Lower tertile | 13(15.5) | 29(34.5) | 42(50.0) | 26(30.9) | 33(39.3) | 25(29.8) | 13(15.5) | 44(52.4) | 27(32.1) | |||||||||||||

| Variable | Cognition | Mathematics | Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% C. I | p-value | AOR | 95% C. I | p-value | AOR | 95% C. I | p-value | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Girls | 0.6 | (0.3-0.9) | 0.048 | 1.2 | (0.7-2.1) | 0.584 | 1.2 | (0.7-2.0) | 0.541 |

| Boys | Reference | ||||||||

| Age groups | |||||||||

| 6-8 years | 0.4 | (0.2-08) | 0.010 | 1.9 | (0.9-3.3) | 0.073 | 1.8 | (0.9-3.5) | 0.103 |

| 11-12 years | 2.2 | (1.1-4.2) | 0.024 | 1.1 | (0.6-2.1) | 0.784 | 0.5 | (3.0-1.0) | 0.054 |

| 9-10 years | Reference | ||||||||

| School grade | |||||||||

| Grade one | 0.1 | (0.5-0.4) | <.001 | 0.8 | (0.3-2.2) | 0.59 | 1.2 | (0.7-4.6) | 0.235 |

| Grade two | 0.1 | (0.-0.3) | <.001 | 1.7 | (0.5-5.8) | 0.369 | 4.1 | (1.3-12.7) | 0.014 |

| Grade three | 0.2 | (0.1-0.5) | <.001 | 0.2 | (0.1-0.6) | 0.004 | 0.7 | (0.3-1.6) | 0.375 |

| Grade four | 0.4 | (0.1-1.1) | 0.072 | 0.3 | (0.1-0.9) | 0.029 | 0.4 | (0.2-1.1) | 0.064 |

| Grade five | 0.6 | (0.2-1.6) | 0.291 | 0.6 | (0.2-1.6) | 0.308 | 0.6 | (0.3-1.5) | 0.270 |

| Grade six | Reference | ||||||||

| Weight-for-age | |||||||||

| Under/overweight | Reference | ||||||||

| Normal Vitamin B1 intake |

0.4 | (0.1-1.1) | 0.066 | 1.7 | (0.6-5.0) | 0.342 | 1.7 | (0.6-5.1) | 0.332 |

| Lower | Reference | ||||||||

| Higher | 6.3 | (2.5-16.0) | <.001 | 0.7 | (0.3-1.6) | 0.676 | 0.3 | (0.1-0.6) | 0.02 |

| Vitamin B2 intake | |||||||||

| Lower | Reference | ||||||||

| Higher | 2.2 | (1.5-7.8) | 0.003 | 1.0 | (0.4-2.2) | 0.961 | 0.5 | (0.3-1.1) | 0.099 |

| Folate intake | |||||||||

| Lower | Reference | ||||||||

| Higher | 1.8 | (0.9-3.3) | 0.086 | 1.0 | (0.5-2.0) | 0.935 | 0.7 | (0.3-1.2) | 0.196 |

| Iron intake | |||||||||

| Lower | Reference | ||||||||

| Higher | 1.9 | (1.0-3.6) | 0.056 | 0.9 | (0.4-1.8) | 0.727 | 0.9 | (0.5-1.7) | 0.750 |

| Zinc intake | |||||||||

| Lower | Reference | ||||||||

| Higher | 1.7 | (0.8-3.3) | 0.130 | 1.1 | (0.5-2.2) | 0.820 | 0.4 | (0.2-0.7) | 0.005 |

| Nutrient blend intake | |||||||||

| Lower | Reference | ||||||||

| Higher | 1.7 | (0.9-3.3) | 0.101 | 1.0 | (0.5-2.1) | 0.918 | 0.6 | (0.3-1.2) | 0.136 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).