1. Introduction

Indonesia ranks as the fourth-largest country in terms of child population, with approximately 80 million children, of whom 10.91% are aged 0–6 years [

1]. This age group represents a crucial phase of early childhood, often referred to as the “golden period,” during which optimal nutrition is essential for proper growth and development. Ensuring adequate nutrition at this stage is vital for fostering a strong immune system and cognitive abilities, which are fundamental to a child’s future well-being [

2]. However, many children do not receive sufficient nutrition due to dietary limitations, often influenced by socioeconomic factors and parental knowledge.

One significant challenge in childhood nutrition is picky eating behavior, affecting 25–53% of children globally [

3]. Picky eaters are at higher risk of undernutrition, as they tend to have lower body weight and shorter stature than non-picky eaters [

3,

4]. Deficiencies in essential macronutrients and micronutrients can result in malnutrition, weakening the immune system, reducing appetite, and impairing cognitive development [

2,

3,

4]. These negative consequences may persist into adulthood, emphasizing the importance of early nutritional interventions [

3].

To address nutritional deficiencies, dietary supplementation, including growth milk, has been widely recommended. Growth milk is a fortified milk product containing essential nutrients such as fish oil, probiotics, prebiotics, proteins, vitamins, and minerals that support children’s nutritional needs [

5]. Although systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggest that fortified milk can help bridge nutrient gaps, its effects on weight gain and height improvement remain minimal [

6]. Moreover, research on formula milk has raised concerns regarding potential health risks, including gastrointestinal infections and respiratory diseases, with some claims about cognitive benefits still being debate [

7].

Given the conflicting research findings, further investigation is necessary to assess the role of growth milk in supporting children’s health. This study aims to evaluate the effects of growth milk consumption on nutritional status, immune resilience, appetite, and cognitive function in children aged 2–5 years, addressing existing knowledge gaps and contributing to evidence-based nutritional recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

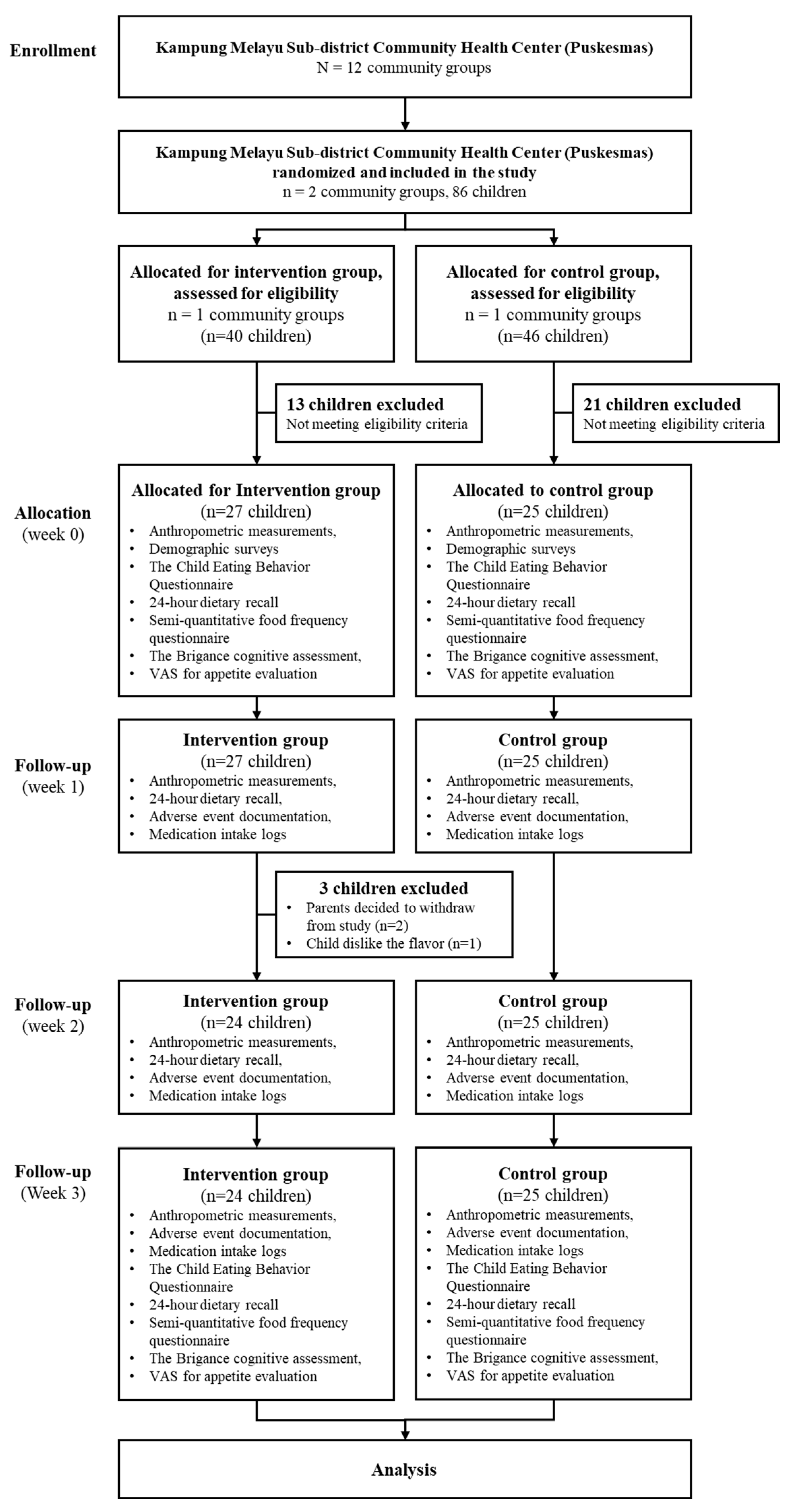

This study is an experimental study employing a clustered randomized controlled trial design. The study was conducted at Kampung Melayu Sub-district Community Health Center (Puskesmas), East Jakarta which covered 12 community groups (

rukun warga/RW). The randomization was done to choose two RWs as the intervention and control groups. The intervention lasted three months, from September 2024 to November 2024. The target population consisted of children aged 2-5 years residing in the selected RWs in Kampung Melayu. The sample size was determined using the independent two-population mean formula, considering a power of 80% and based on prior research findings. A total of 49 children were recruited, with 25 participants in the control group and 24 in the intervention group.

Figure 1 illustrates the sample recruitment process for the study.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants eligible for inclusion in this study were children aged 2-5 years who were in good health at the time of enrollment. They were required to have a weight-for-height measurement between 0 and -2 SD on the WHO growth curve and should not have had a habit of consuming growth milk regularly, defined as less than four times per week. Only children whose parents provided informed consent and agreed to participate in the study were included. Drop out criteria consisted of participants who were lost to follow-up during the study period or those who failed to adhere to the prescribed milk consumption protocol. Children who experienced significant health issues unrelated to the study intervention that could impact their nutritional status were also excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Intervention and Data Collection Procedures

Parents of eligible children were provided with a detailed explanation of the study and were required to sign an informed consent form before participation. Baseline anthropometric assessments, including weight, height, and head circumference, were conducted using standardized equipment. Trained enumerators conducted interviews and administered pre-intervention questionnaires, including demographic surveys, the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire for food fussiness, 24-hour dietary recall, a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire, and the Brigance cognitive assessment, along with a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for appetite evaluation.

The intervention group received growth milk powder in sachet form (39 grams per sachet). Each sachet was diluted with warm water to one serving (approximately 200 ml of milk), and participants were instructed to consume two servings per day (400 ml in total) for three months. Milk sachets were distributed weekly, and community health workers monitored adherence through weekly check-ins. Parents were required to return empty sachets, and any remaining unused sachets were also collected. The control group received only nutritional education without any milk supplementation. Parents were advised to maintain their children's usual dietary patterns without modifications.

2.4. Follow-Up and Monitoring

Daily follow-ups were conducted via telephone to ensure compliance with the milk consumption protocol. Weekly compliance forms were recorded, and monthly assessments included 24-hour dietary recall, adverse event documentation, and medication intake logs. Anthropometric measurements were repeated at baseline, one month, two months, and three months post-intervention. Final assessments included the same set of questionnaires and VAS evaluation. All health conditions of the participants were closely monitored throughout the study. Parents or caregivers were interviewed regarding the child's health status on each visit. Any illnesses or complaints, whether related to the intervention or not, were documented in the adverse event recording form. Any medications or therapies received outside the study intervention were separately recorded. In cases of severe illness requiring hospitalization, researchers reported the event to the ethics committee within 24 hours.

2.5. Data Analysis Plan

All collected data were securely stored digitally and analyzed using univariate, bivariate, and multivariate statistical methods to assess relationships between independent and dependent variables. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 for Windows.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

The study involved a total of 49 children aged 2 to 5 years, with 25 participants from the cluster assigned to the control group and 24 participants from the cluster receiving the intervention of growth milk. The demographic characteristics of the participants, including age, gender distribution, and baseline anthropometric measurements such as weight and height, were comparable between the two groups. Statistical analyses confirmed there were no significant differences in these baseline characteristics, ensuring that any observed effects could be attributed to the intervention rather than pre-existing disparities (summarized in

Table 1).

3.2. Growth Outcomes

There were no significant height, weight, z-score or head circumference difference between intervention and control group, as shown in

Table 2. However, over the three-month intervention period, significant improvements were observed in the several growth parameters of the intervention group. The average weight of children in the intervention group increased from 12.91 kg at baseline to 13.32 kg by the end of the study, reflecting a mean weight gain of 0.41 kg (p < 0.001). Similarly, a weight increase can also be seen in the control group with 12.48 kg at baseline to 12.98 kg by the end of the study, reflecting a mean weight gain of 0.50 kg (p < 0.001). This weight gain is indicative of improved nutritional status and growth. However, if change in body weight was compared between intervention and control group, no significant difference was found (p < 0.573). Similarly, height measurements in both group showed a significant increase, with the intervention group showed average height rising from 94.61 cm at baseline to 96.54 cm after the study, representing a mean increase of 1.93 cm (p < 0.001) and control group raised from 92 cm at the baseline to 94 cm at month three. Significant difference in height change between intervention and control group was found in month two. These findings suggest that the consumption of growth milk contributed positively to the linear physical growth of the children, as illustrated in

Table 3.

3.3. Z-Scores Analysis

Z-scores for height-for-age and body mass index (BMI)-for-age were also analyzed to assess the nutritional status of the children more comprehensively. The intervention group exhibited significant improvements in their height-for-age Z-scores, which increased from -1.65 to -1.58 over the study period, indicating a positive shift towards normal growth patterns (summarized in

Table 2). Furthermore, after performing an analysis on the intervention group exclusively, we found a statistically significant increase in the height-for-age parameter when comparing baseline to first month (0.11±0.16; p=0.004), baseline to second month (0.12±0.20; p=0.007), and baseline to third month (0.15±0.30; p=0.023). This significance is exclusively seen only among the intervention group as demonstrated on

Table 3. Meanwhile, the BMI-for-age Z-scores showed a similar trend with the intervention group demonstrating a significant increase, suggesting that the growth milk not only supported weight gain but also contributed to healthier body composition. Furthermore, head circumference measurements indicated a notable increase, with the average head circumference rising from 47.73 cm to 48.54 cm, reflecting significant changes in brain growth and development (summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3).

3.4. Health and Cognitive Outcomes

Despite the positive outcomes in growth parameters, the study did not find significant differences in health-related outcomes between the two groups. The incidence of illness, as recorded during the study, was similar in both the control and intervention groups, with an average of 1.44 episodes of illness reported in the control group compared to 1.67 in the intervention group (p = 0.654). There was no significant difference between specific illness incidence as summarized in

Table 4. Additionally, appetite scores measured by the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) showed no significant changes, with both groups reporting similar levels of appetite or liking looking at food throughout the study. Food fussiness, assessed using the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ), also did not reveal significant differences, indicating that the intervention did not alter children's eating behaviors (summarized in

Table 4). Cognitive function, evaluated using the Brigance screening tool, showed no significant differences between the intervention and control groups after the study, suggesting that while growth parameters improved, cognitive development remained unaffected by the growth milk intervention. Language scores declined slightly in both groups, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.925)

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effect of growth milk compared with no additional milk on the nutritional status, immune resilience, appetite, and cognitive function of children aged 2–5 years. We found that providing 400 ml of growth milk per day for three months is associated with significant improvements in anthropometric measures. The group who consumed growth milk for three months increased their weight by 0.41±0.44 kg and height by 1.93±0.93 cm. Similarly, their BMI-for-age Z-scores and height-for-age Z-scores also show a notable increase. This is strengthened by the fact that the findings are exclusively statistically significant on the intervention group. Findings in this present study are consistent with previous studies on the effect of milk supplementation on anthropometric status of children.[

6,

8,

9] According to Center of Disease Control and Prevention, the average growth in height of children aged 2–5 years is approximately 0.43–0.64 cm per month, while the average weight gain is about 0.19 –0.23 kg per month.[

10,

11] It can be observed that children in the intervention group managed to grow within the expected average gain and even exceeded it. The role of growth milk in height gain can be attributed to its association with higher concentration of blood calcium, which suggested that nutrients in milk are essential to improve bone mineralization and achieve better bone density.[

12] A previous study analyzing the dietary intake of Indonesian children 1–5 years discovered that over 50% of the population had inadequate intakes of iron, calcium, zinc, vitamins A, D, and Bs.[

13]

Data from SEANUTS II Indonesia indicate a high prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies among children under five years old, with 22.8% experiencing anemia, 20.3% iron deficiency, 11.9% zinc deficiency, 1.9% lacking vitamin A, and 27.1% exhibiting vitamin D insufficiency.[

14] Given this substantial burden, several studies have shown that growth milk consumption can help improve micronutrient intake. A study in China found that growth milk consumption significantly enhanced nutrient intake, while dietary modeling in the Philippines demonstrated that adding growth milk to the diet increased vitamin and mineral intake.[

15,

16] Additionally, a randomized controlled trial in New Zealand reported lower iron and vitamin D deficiency rates among growth milk consumers.[

17] These findings suggest that although the present study did not find a significant difference in weight gain between the two groups, growth milk has been shown to improve micronutrient status. This highlights the need for further research to explore its role in addressing micronutrient deficiencies in young children.

Growth milk used in this study is rich in nutrients required during bone formation which enhance height gain. Studies conducted in developing countries usually revealed slightly higher growth outcomes after the supplementation of growth milk, likely because children in such countries generally experienced compromised development prior to intervention.([

9] Although the gain in weight corresponds to the growth in height, evidence found in this study suggested that growth milk does not promote dramatic weight gain which may lead to obesity, as reflected by relatively stable weight-for-age Z-scores throughout three months. Despite that, available literature may show incongruence in results. A similar study performed in India found that the group receiving fortified milk gained more height in comparison to a control group,[

18] and a similar result is seen in a study performed in The Philippines, who also noted that normoweight subjects receiving fortified milk were also at risk of being overweight within the 12 weeks of intervention.[

8] However, previous systematic reviews have found that no significant impacts to height gain were provided by fortified milk.[

6,

19] This may be due to differences in nutrients composing the fortified milk used in each intervention. Additionally, when compared to WHO's anthropometric indices, a study in Nigeria found that subjects consuming 600mL fortified milk for 6 months showed HAZ improvements, however, the results were not statistically significant among groups.[

20] Differences in demography and protocols may also account to discrepancies among literatures.

While children in the growth milk group gained a notable increase of head circumference of 0.81±0.75 cm, we found no difference in cognitive parameters of the children before and after the study. Additionally, growth milk supplementation did not bring about changes in eating behavior. It has been suggested that vitamin D present in growth milk is responsible in processes such as immunomodulation and nerve conduction pivotal to the development of the brain, but these findings were inconclusive and still need to be further researched.[

21] While PUFA and DHA concentration in growth milk may be positively associated with better performance in cognitive outcomes such as concentration and memory, their relationship with overall cognitive performance remains to be investigated.[

8,

19] It should also be noted that aside from nutrition, other factors which include physical activity, sleep quality, and socioeconomic status all contributed to the brain’s cognitive function children’s ability to learn.[

22] Growth milk is rich in immune-supporting micronutrients, the insignificant effect of growth milk on the incidence of illness demonstrated in our study may hint on the normal nutrition status of children prior to supplementation and older age of the children, as the participants of previous studies which yield beneficial effects of growth milk in lowering morbidity were comprised of malnourished children or children younger than two years.[

23,

24] A study investigating the effect of changes in dietary patterns in undernourished children revealed an increase in the number of activated B cells and pro-inflammatory cytokines, but no changes in other cells forming adaptive immunity.[

25]

Despite these differences, evidence from other studies supports the role of growth milk in reducing illness. A retrospective cohort clinical study conducted in Indonesia demonstrated that a daily consumption of at least 500 mL of growth milk for a minimum of six months could provide up to a 58% reduction in the incidence of acute respiratory infections (ARI), suggesting that regular consumption of growth milk may support immune system development and protection against infections.[

26] Similarly, a study conducted in India found that the administration of growth milk, administered as three sachets per day for one year, significantly reduced morbidity in preschool children, including a decrease in the incidence of diarrhea (18%), pneumonia (26%), high fever (7%), and the number of sick days due to severe illness (15%).[

27] Both studies had longer intervention durations and higher milk intake, which may explain why they observed significant reductions in morbidity, whereas our study did not demonstrate similar findings.

This study has several limitations. The relatively short duration (3 months) may not be sufficient to observe significant growth differences, requiring a longer observation period. Environmental factors also play a crucial role. A flood disaster in the third month affecting the intervention group may have increased diarrhea cases, which could impede growth. Additionally, factors such as physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and sleep patterns were not assessed but could influence growth. Irregular sleep can affect growth hormone production, while lack of physical activity, sun exposure, and a sedentary lifestyle may impair muscle and bone development. These external factors should be considered when evaluating the effectiveness of milk supplementation on child growth.

5. Conclusions

This study found that sociodemographic characteristics and baseline measurements were similar between children who consumed growth milk and those who did not. Over three months, children aged 2–5 years who consumed growth milk showed significant increases in weight, height, and head circumference, as well as improvements in height-for-age and BMI-for-age Z-scores. However, no significant differences were observed in weight-for-age Z-scores, illness incidence, or scores on VAS, CEBQ, or Brigance after the intervention. Based on these findings, it is recommended to conduct a longer-duration study on the effects of growth milk consumption. Additionally, future research should consider including younger children aged 6 months to 2 years to understand better the broader impact of growth milk on early childhood development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and D.N.C.; methodology, R.S., D.N.C. and L.S.A.; software, L.S.A.; validation, R.S.; formal analysis, D.N.C. and L.S.A.; investigation, R.S., D.N.C., L.S.A., K.R.F.A. and I.A.; resources, R.S.; data curation, D.N.C. and L.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.N.C. and L.S.A.; writing—review and editing, R.S., D.N.C., L.S.A., K.R.F.A. and I.A.; visualization, L.S.A.; supervision, R.S. and D.N.C.; project administration, K.R.F.A. and I.A.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PT SANGHIANG PERKASA, funding number 502/SHP-LEGAL/PKS/KNRC/VII/2024 and 834/UN2.F1.DEPT.16/OTL.03.00/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of FKUI-RSCM (protocol code KET-1101/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2024, 29 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are not publicly available as they are owned by the sponsor.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for Putri Pratiwi Oktaviani, Aprilia Herawati, Kevin Sebastian Santoso, Meidyna Dwi Puspa, Muhtar Fauji, Mardiana, Turini, Nina Yusnita, Nur Hartati, Iin Suwarti and Ety Sumiaty for their contributions in this study. We are also thankful for all our volunteers who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Although PT SANGHIANG PERKASA was the study’s sponsor, the company’s involvement had no bearing on the results of the research.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

| CEBQ |

Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| RW |

Rukun Warga (Neighborhood Administrative Unit) |

References

- UNICEF Indonesia. The state of children in Indonesia 2020 [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/sites/unicef.org.indonesia/files/2020-06/The-State-of-Children-in-Indonesia-2020.pdf.

- Direktorat Statistik Kesejahteraan Rakyat. Profil anak usia dini 2023. Vol. 4. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik; 2023.

- Kamarudin, M.S.; Shahril, M.R.; Haron, H.; Kadar, M.; Safii, N.S.; Hamzaid, N.H. Interventions for Picky Eaters among Typically Developed Children—A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduci E, Profio D, Corsello E, Scatigno A, Fiore L, Bosetti G. Which milk during the second year of life: a personalized choice for a healthy future? nutrients. 2021;13.

- Morinaga. Formula milk morigro [Internet]. Morinaga. Available from: https://morinaga.id/en/products/formula-milk-morigro.

- Matsuyama, M.; Harb, T.; David, M.; Davies, P.S.; Hill, R.J. Effect of fortified milk on growth and nutritional status in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr 2016, 20, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munblit, D.; Crawley, H.; Hyde, R.; Boyle, R.J. Health and nutrition claims for infant formula are poorly substantiated and potentially harmful. BMJ 2020, 369, m875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervo, M.M.C.; Mendoza, D.S.; Barrios, E.B.; Panlasigui, L.N. Effects of Nutrient-Fortified Milk-Based Formula on the Nutritional Status and Psychomotor Skills of Preschool Children. J. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 2017, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haile, B.; Headey, D. Growth in milk consumption and reductions in child stunting: Historical evidence from cross-country panel data. Food Policy 2023, 118, 102485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Growth Charts - CDC Growth Charts [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 22]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/cdc-growth-charts.htm.

- Novina, N.; Hermanussen, M.; Scheffler, C.; Pulungan, A.B.; Ismiarto, Y.D.; Andriyana, Y.; Biben, V.; Setiabudiawan, B. Indonesian National Growth Reference Charts Better Reflect Height and Weight of Children in West Java, Indonesia, than WHO Child Growth Standards. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2020, 12, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lamas C, De Castro MJ, Gil-Campos M, Gil Á, Couce ML, Leis R. Effects of Dairy Product Consumption on Height and Bone Mineral Content in Children: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Advances in Nutrition. 2019 May 1;10:S88–96.

- Sunardi, D.; Wibowo, Y.; Mak, T.N.; Wang, D. Energy and Nutrient Intake Status Among Indonesia Children Aged 1–5 Years With Different Dairy Food Consumption Patterns. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, 719–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekalih, A.; Chandra, D.N.; Mirtha, L.T.; Khouw, I.; Wong, G.; Sekartini, R. Dietary intakes, nutritional and biochemical status of 6 months to 12-year-old children before the COVID-19 pandemic era: the South East Asian Nutrition Survey II Indonesia (SEANUTS II) study in Java and Sumatera Islands, Indonesia. Public Health Nutr 2025, 28, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Patterns of the Consumption of Young Children Formula in Chinese Children Aged 1–3 Years and Implications for Nutrient Intake. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, T.-N.; Angeles-Agdeppa, I.; Tassy, M.; Capanzana, M.V.; Offord, E.A. The Nutritional Impact of Milk Beverages in Reducing Nutrient Inadequacy among Children Aged One to Five Years in the Philippines: A Dietary Modelling Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell AL, Davies PSW, Hill RJ, Milne T, Matsuyama M, et al. Compared with cow milk, a growing-up milk increases vitamin D and iron status in healthy children at 2 years of age: the growing-up milk–lite (GUMLi) randomized controlled trial. J Nutr. 2018 Oct 1;148(10):1570–9.

- Thomas, T.; Singh, M.; Swaminathan, S.; Kurpad, A.V. Age-related differences in height gain with dairy protein and micronutrient supplements in Indian primary school children. 2020, 29, 355–362. [CrossRef]

- Brooker, P.G.; Rebuli, M.A.; Williams, G.; Muhlhausler, B.S. Effect of Fortified Formula on Growth and Nutritional Status in Young Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senbanjo, I.O.; Owolabi, A.J.; Oshikoya, K.A.; Hageman, J.H.J.; Adeniyi, Y.; Samuel, F.; Melse-Boonstra, A.; Schaafsma, A. Effect of a Fortified Dairy-Based Drink on Micronutrient Status, Growth, and Cognitive Development of Nigerian Toddlers- A Dose-Response Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 864856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, D.; Litrán, M.A.B.; García-Mármol, E.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, M.; Cueto-Martín, B.; López-Huertas, E.; Catena, A.; Fonollá, J. Еffects of fortified milk on cognitive abilities in school-aged children: results from a randomized-controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirout, J.; LoCasale-Crouch, J.; Turnbull, K.; Gu, Y.; Cubides, M.; Garzione, S.; Evans, T.M.; Weltman, A.L.; Kranz, S. How Lifestyle Factors Affect Cognitive and Executive Function and the Ability to Learn in Children. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, F.; la Paz, S.M.-D.; Leon, M.J.; Rivero-Pino, F. Effects of Malnutrition on the Immune System and Infection and the Role of Nutritional Strategies Regarding Improvements in Children’s Health Status: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2023, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazawal, S.; Dhingra, U.; Dhingra, P.; Hiremath, G.; Kumar, J.; Sarkar, A.; Menon, V.P.; E Black, R. Effects of fortified milk on morbidity in young children in north India: community based, randomised, double masked placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2006, 334, 140–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, Z.; Hasan, M.; Gazi, A.; Hossaini, F.; Haque, N.M.S.; Palit, P.; Fahim, S.M.; Das, S.; Mahfuz, M.; Marie, C.; et al. Immune modulation by nutritional intervention in malnourished children: Identifying the phenotypic distribution and functional responses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 2023, 98, e13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewi, D.K.; Adi, N.P.; Prayogo, A.; Sundjaya, T.; Wasito, E.; Kekalih, A.; Basrowi, R.W.; Jo, J. Regular Consumption of Fortified Growing-up Milk Attenuates Upper Respiratory Tract Infection among Young Children in Indonesia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Open Public Heal. J. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazawal, S.; Dhingra, U.; Dhingra, P.; Hiremath, G.; Kumar, J.; Sarkar, A.; Menon, V.P.; E Black, R. Effects of fortified milk on morbidity in young children in north India: community based, randomised, double masked placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2006, 334, 140–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).