Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Growing Conditions and Experimental Design

| Oct | Nov | Dec | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly average temperature (°C) | 3.3 | 30.6 | 48.9 | 19.6 | 13.4 | 20.9 | 18.1 | 58.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Monthly average precipitation (mm) | 16.3 | 9.1 | 5.4 | -1.7 | 0.5 | 5.3 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 22.4 | 25.6 | 28.0 | 25.3 |

Measurements

Growth Parameters

Oil Content and Oilseed Yield

Fatty Acids

Relative water content (RWC)

Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Content

Total Soluble Sugar Content

Proline Content

Antioxidant Enzyme Extractions and Assays

Total Polyphenol Content

DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl-Hydrate) Radical Scavenging Activity

Data Statistical Processing

3. Results

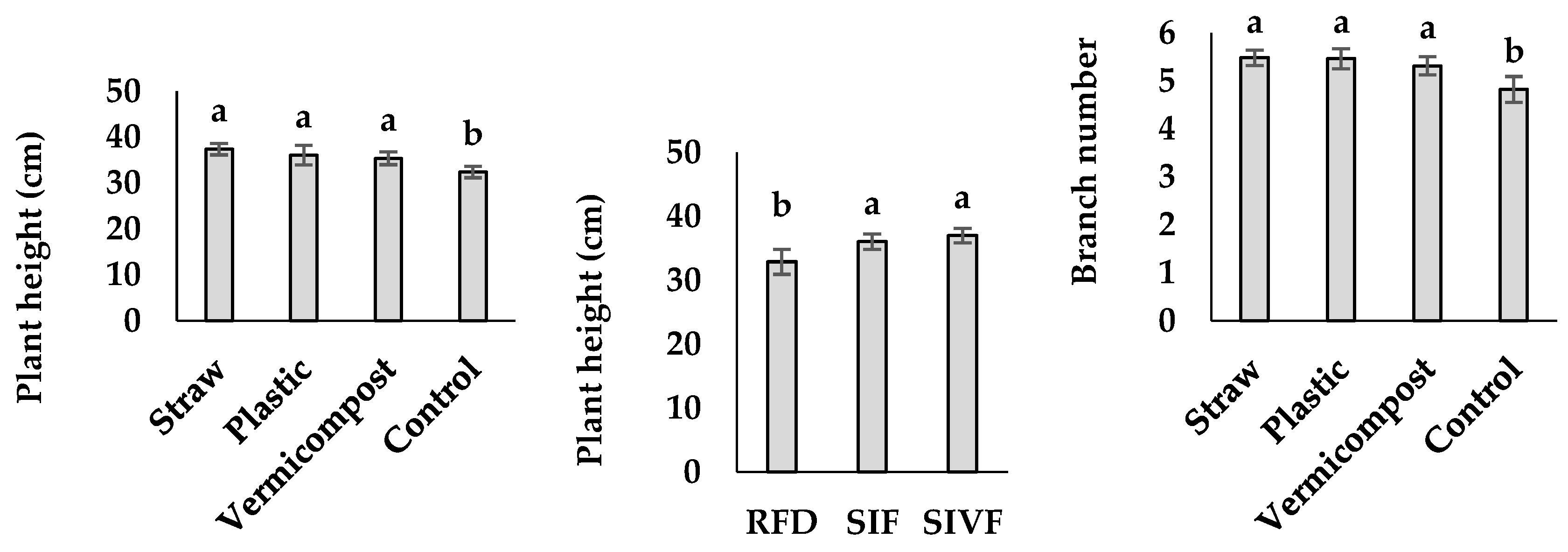

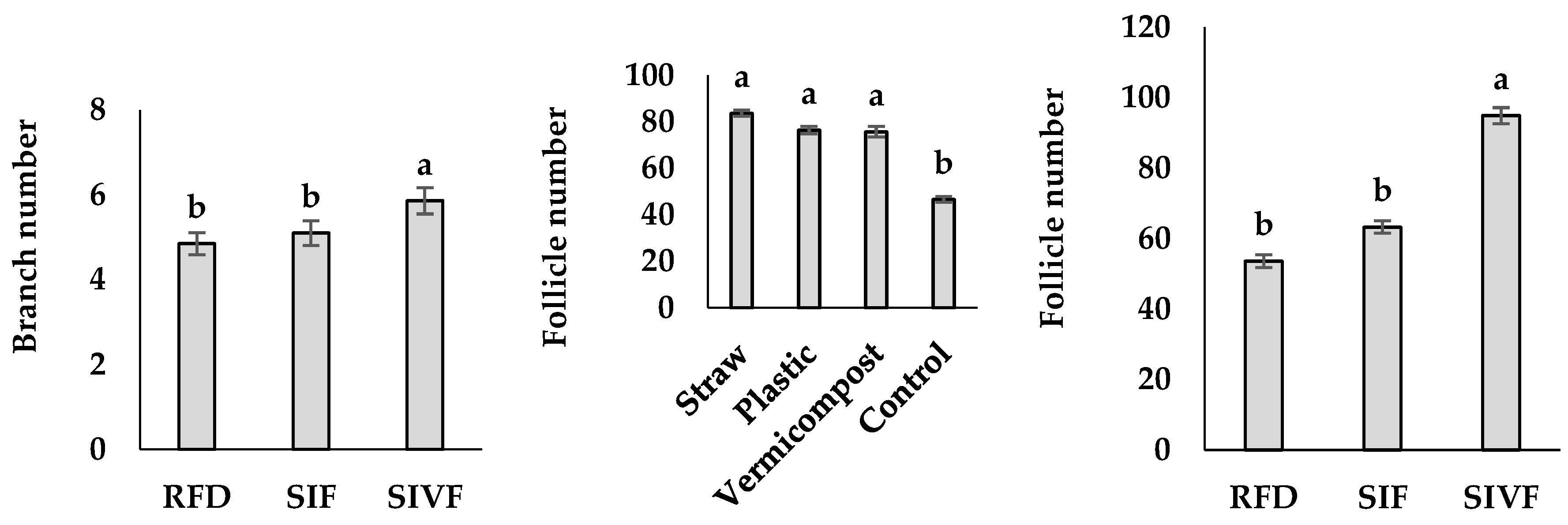

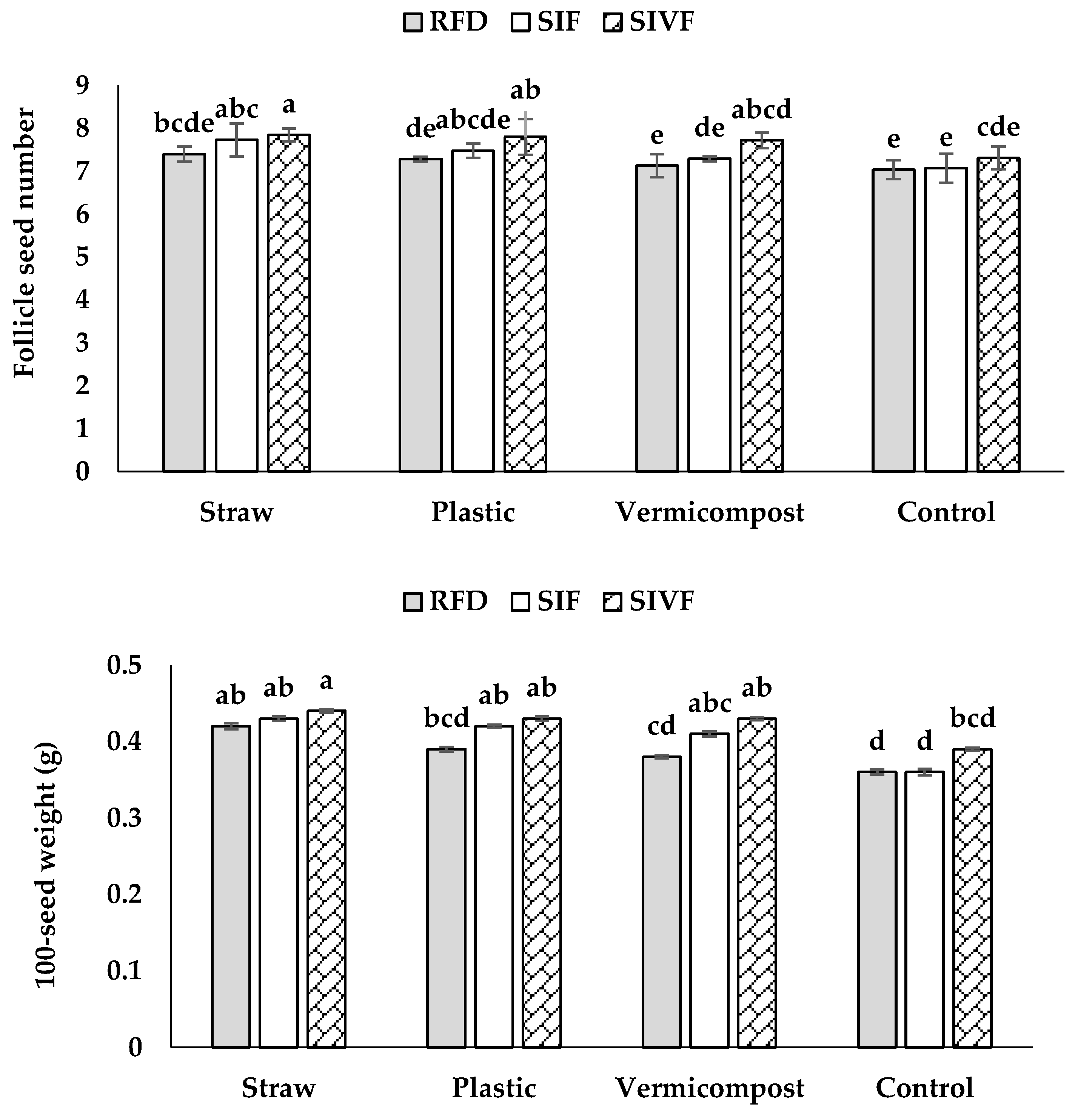

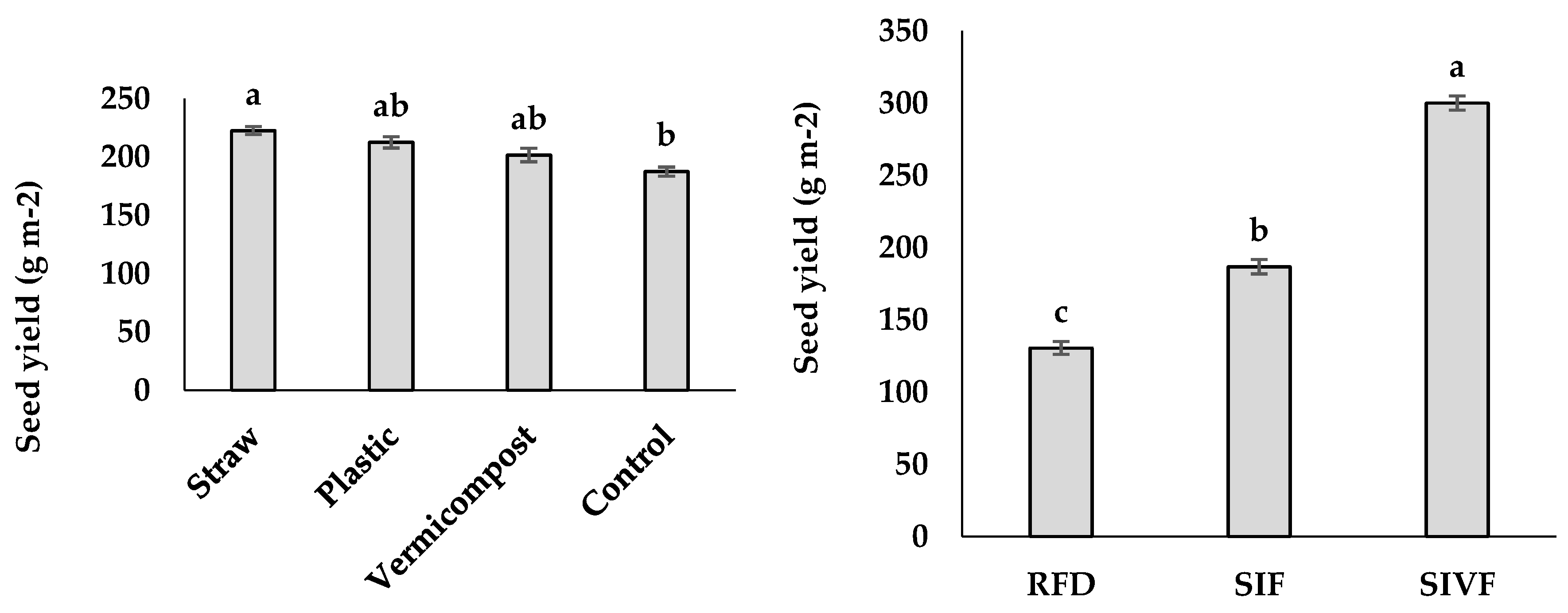

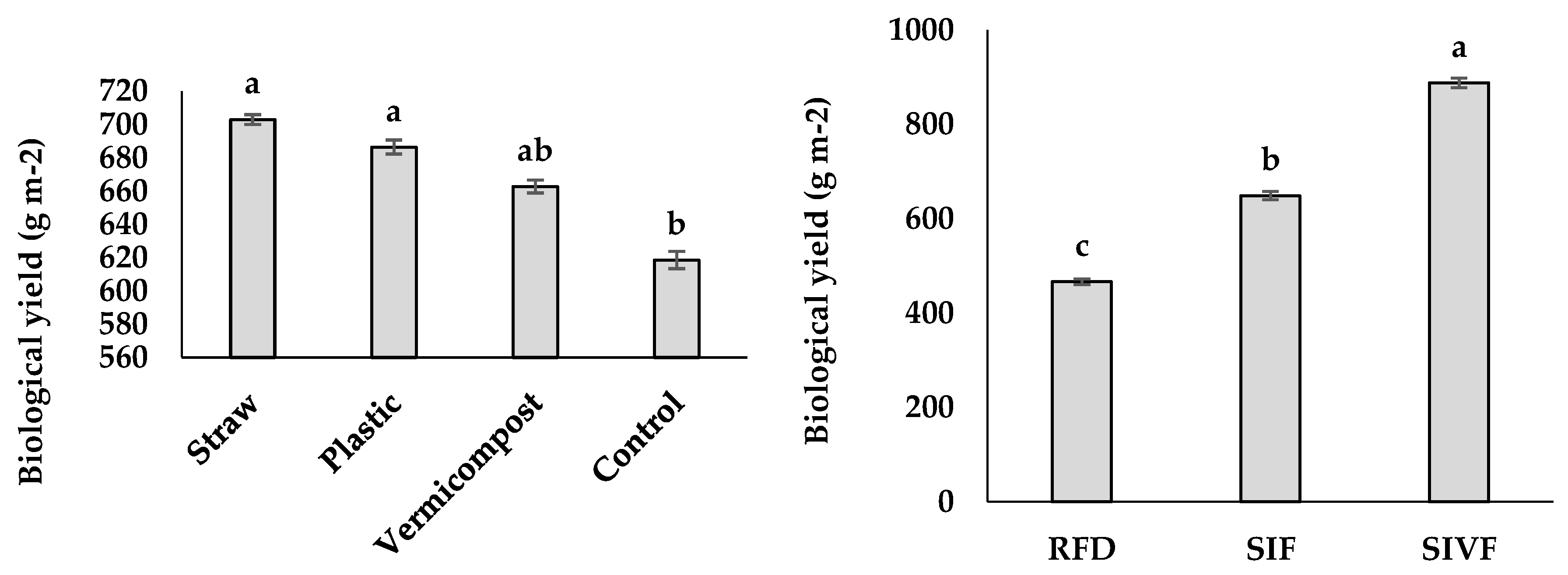

Biometrical and Seed Yield Parameters

| Source of variation | Plant height | Branch number | Follicle number | Follicle seed number | 100-seed weight | Seed yield | Biological yield | Oilseed content | Oilseed yield | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulch (M) | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| Irrigation condition (IC) | ** | * | ** | * | ** | * | * | ** | ** | |

| M x IC | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | * | ** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | * |

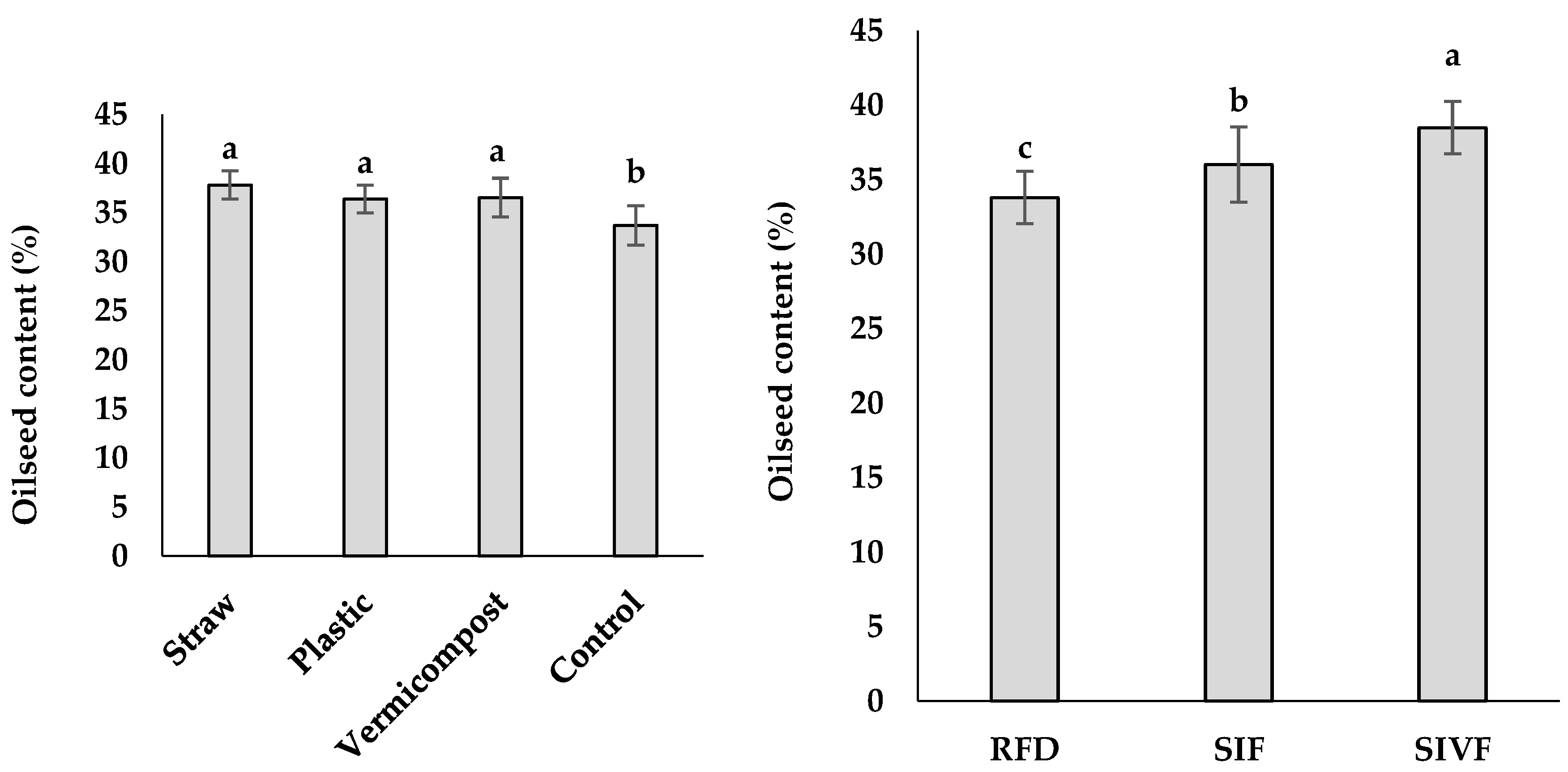

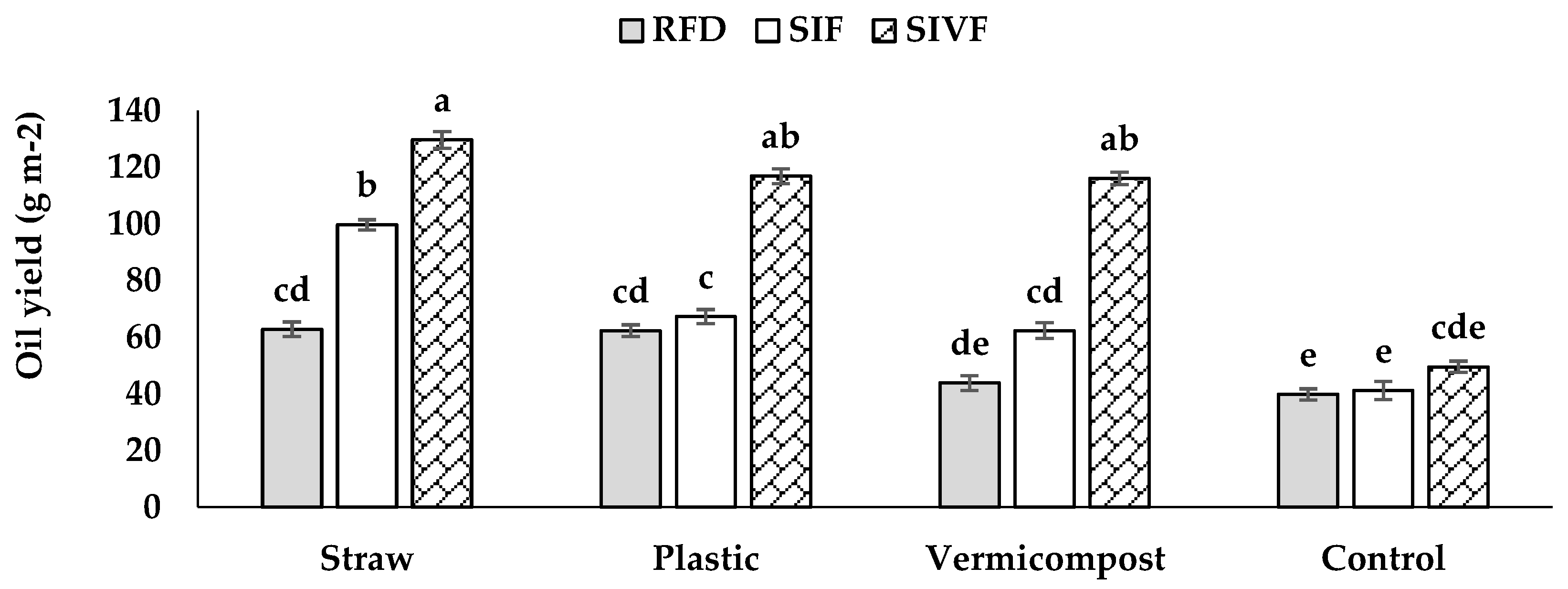

Oilseed Content, Yield and Fatty Acid Composition

Physiological Traits

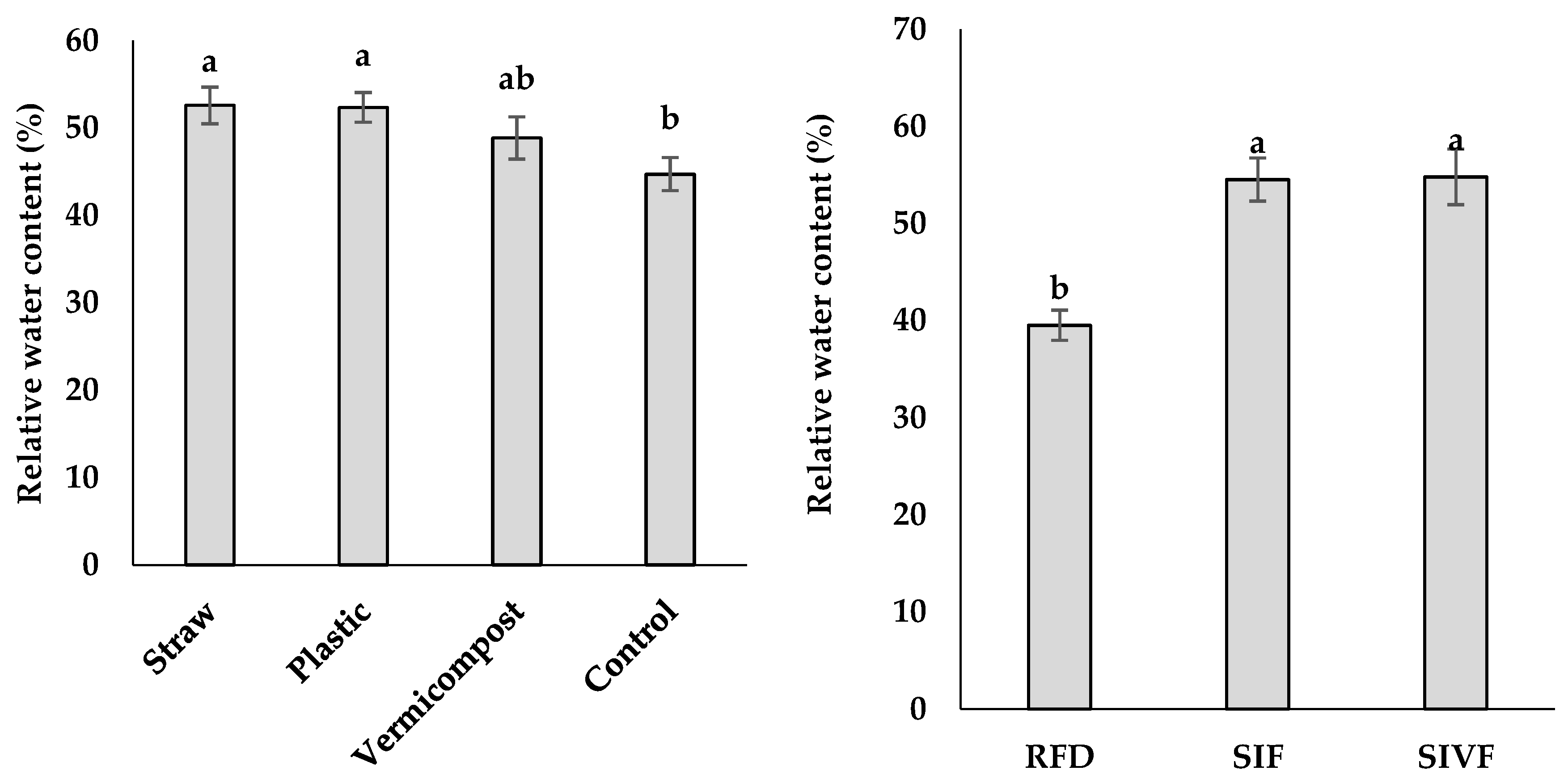

Relative Water Content

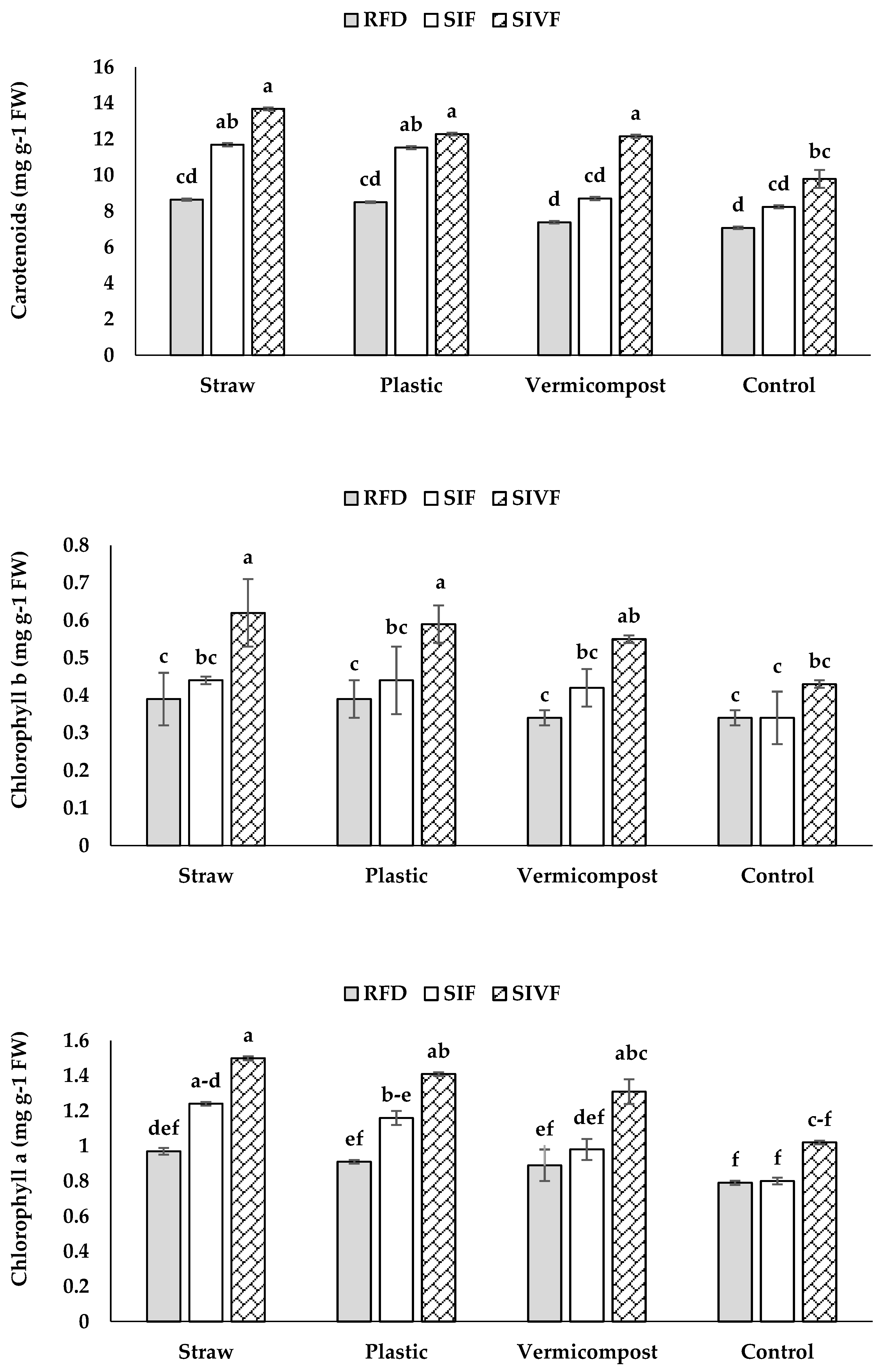

Photosynthetic Pigments

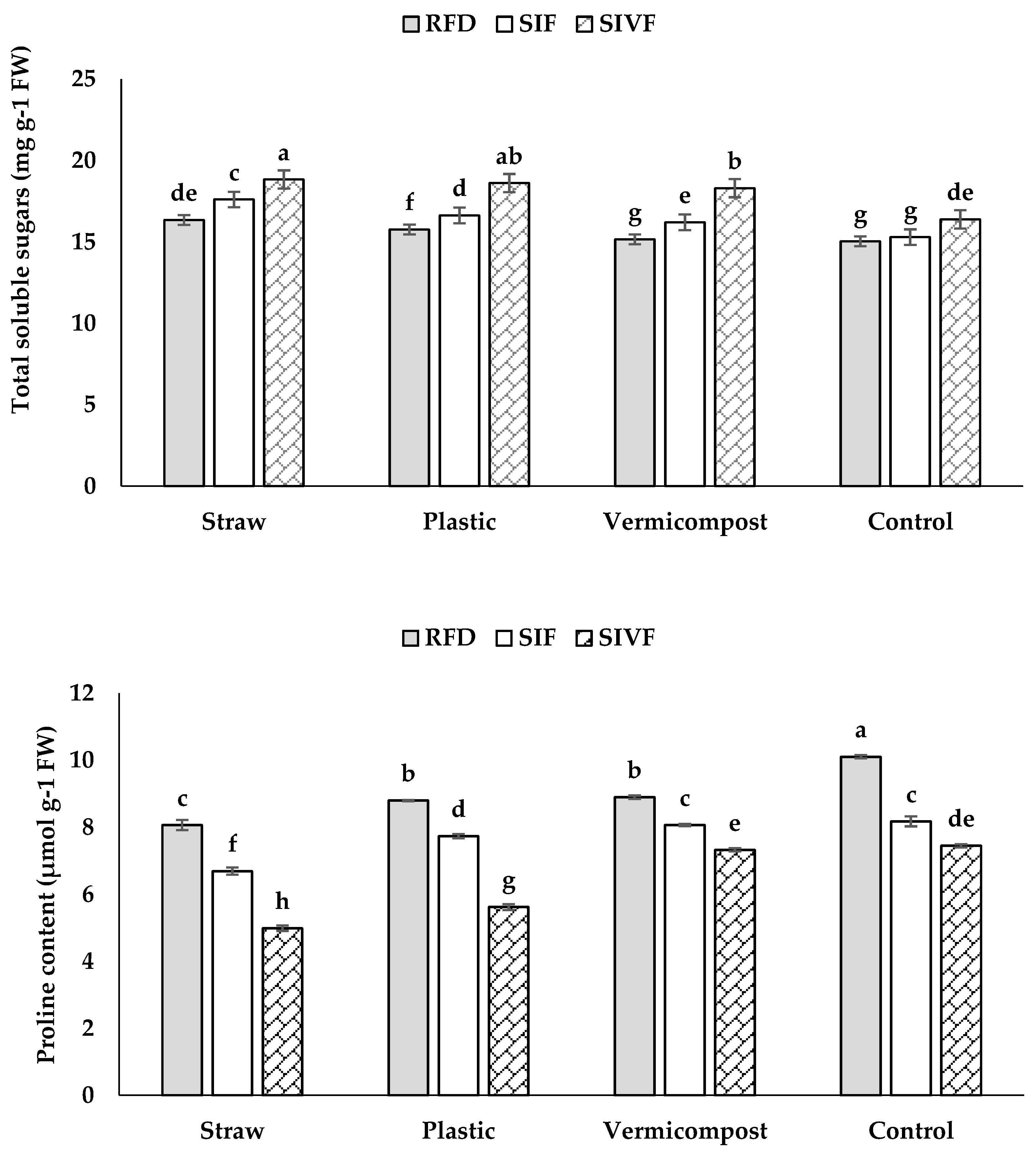

Total Soluble Sugars and Proline Content

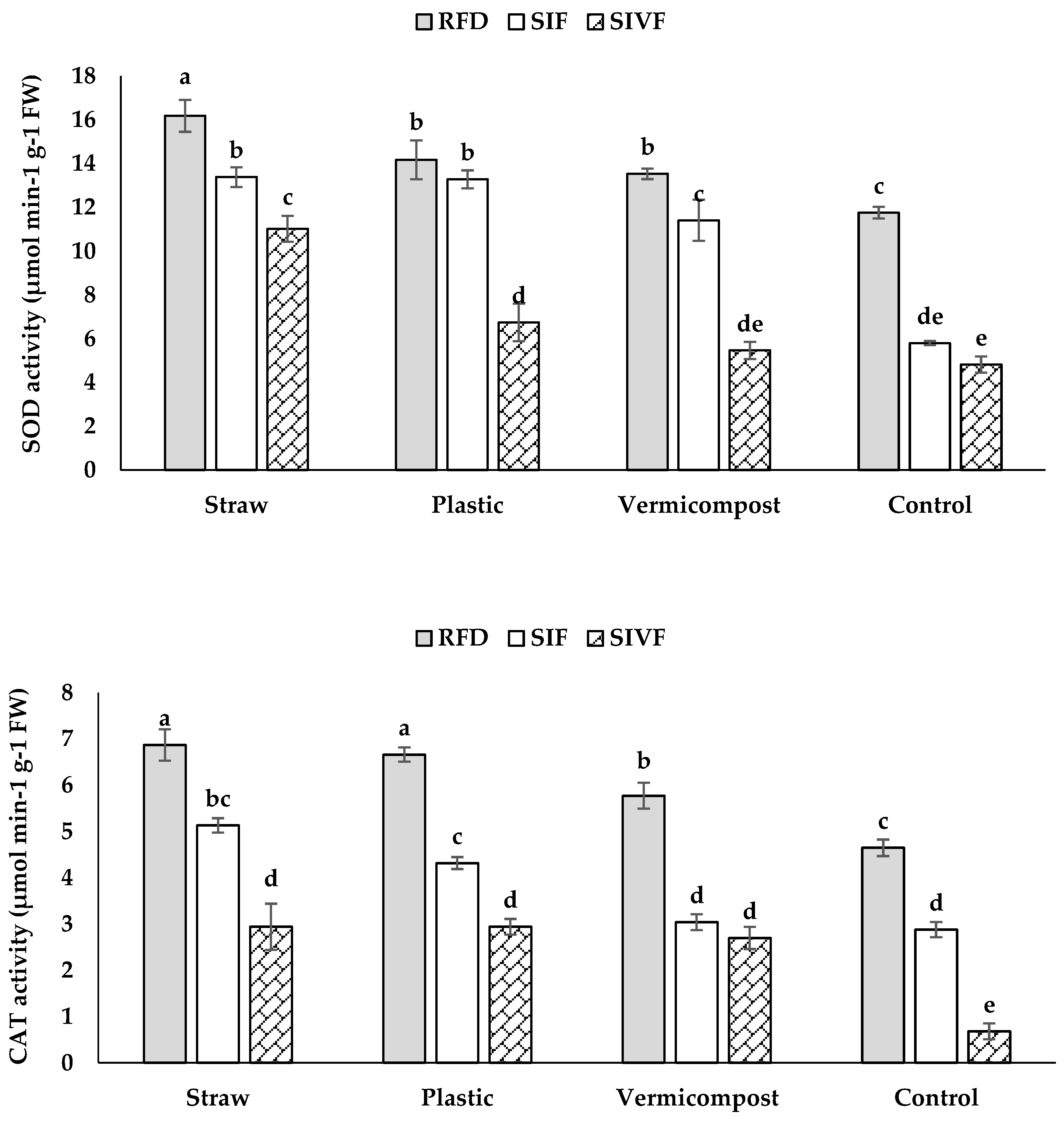

Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

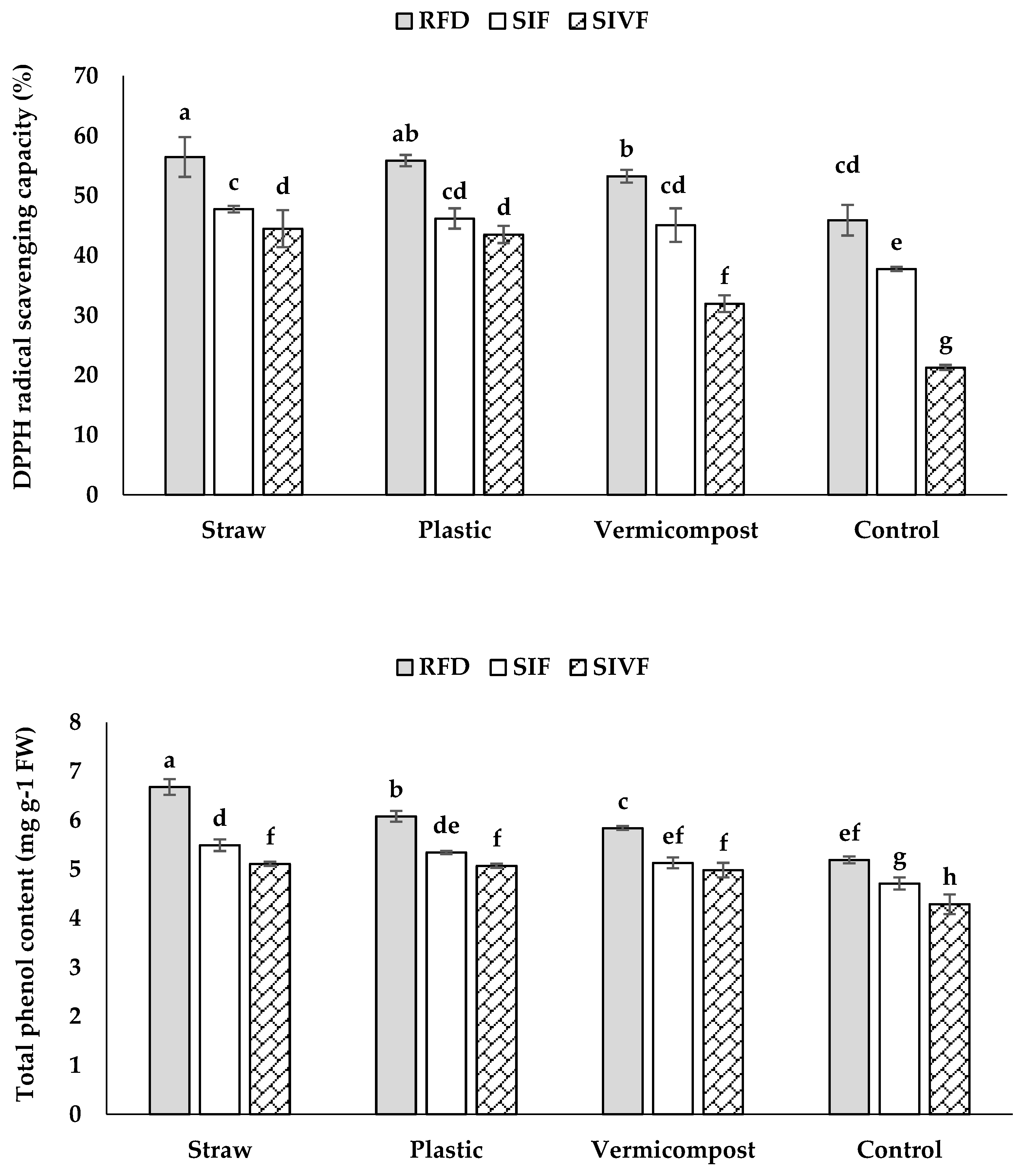

Total Phenol Content and DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Approval

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Chugh, V.; Kaur, D.; Purwar, S.; Kaushik, P.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, H.; Rai, A.; Singh, C.M.; Kamaluddin Dubey, R.B. Applications of molecular markers for developing abiotic-stress-resilient oilseed crops. Life 2023, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Zou, Y.; Tian, R.; Huang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Peng, D. Transcriptome analysis of fiber development under high-temperature stress in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 195, 116019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, S.; Tripathi, M.K.; Tiwari, S.; Tripathi, N.; Payasi, D.K.; Tiwari, P.N.; Singh, K.; Yadav, R.K.; Asati, R.; Chauhan, S. Molecular advances to combat different biotic and abiotic stresses in linseed (Linum usitatissimum L.): A comprehensive review. Genes 2023, 14, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibabaie, F.; Abedpoor, N.; Safavi, K.; Taghian, F. Natural remedies medicine derived from flaxseed (secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, lignans, and α-linolenic acid) improve network targeting efficiency of diabetic heart conditions based on computational chemistry techniques and pharmacophore modeling. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, 14480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Qi, F.; Wang, F.; Lin, Y.; Xiaoyang, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, B.; Qi, X.; Deyholos, M.K.; Zhang, J. Evaluation of differentially expressed genes in leaves vs. roots subjected to drought stress in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behzadnejad, J.; Tahmasebi-Sarvestani, Z.; Aein, A.; Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A. Wheat straw mulching helps improve yield in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) under drought stress. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2020, 14, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmod, N.R.; Alkooranee, J.T.; Alshammary, A.A.G.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Effect of wheat straw as a cover crop on the chlorophyll, seed, and oilseed yield of Trigonella foeunm graecum L under water deficiency and weed competition. Plants 2019, 8, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Zaheer, M.S.; Ali, H.H.; Erinle, K.O.; Wani, S.H.; Iqbal, R.; Okone, O.G.; Raza, A.; Waqas, M.M.; Nawaz, M. Physiological and biochemical properties of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under different mulching and water management systems in the semi-arid region of Punjab, Pakistan. Arid. L. Res. Manag. 2022, 36, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Fahadi Hoveizeh, N.; Zahedi, S.M.; Arji, I. Effect of organic and synthetic mulches on some morpho-physiological and yield parameters of ‘Zard’ olive cultivar subjected to three irrigation levels in field conditions. South African J. Bot. 2023, 162, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Chiyaneh, E.; Seyyedi, S.M.; Ebrahimian, E.; Moghaddam, S.S.; Damalas, C.A. Exogenous application of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) alleviates the effect of water deficit stress in black cumin (Nigella sativa L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aquino, G.S.; de Conti Medina, C.; Shahab, M.; Santiago, A.D.; Cunha, A.C.B.; Kussaba, D.A.O.; Carvalho, J.B.; Moreira, A. Does straw mulch partial-removal from soil interfere in yield and industrial quality sugarcane? A long-term study. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Fan, J.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, F.; Liao, Z.; Lai, Z.; Yan, S.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Xiang, Y. Ridge-furrow plastic film mulching enhances grain yield and yield stability of rainfed maize by improving resources capture and use efficiency in a semi-humid drought-prone region. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 269, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Chai, Q.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Cheng, H.; Chang, L.; Chai, S. Straw strip mulching in a semiarid rainfed agroecosystem achieves winter wheat yields similar to those of full plastic mulching by optimizing the soil hydrothermal regime. Crop J. 2022, 10, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Chiyaneh, E.; Mahdavikia, H.; Hadi, H.; Muhittin, K.; Caruso, G.; Siddique, K.H.M. The effect of exogenously applied plant growth regulators and zinc on some physiological characteristics and essential oil constituents of Moldavian balm (Dracocephalum moldavica L.) under water stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 2201–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, W.R. Irrigation engineering — Sprinkler, trickle, surface irrigation principles, design and agricultural practices. Agric. Water Manag. 1984, 9, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOCS. Official methods and recommended practices of the American oil. 4th Ed. Soc Champaign, IL, 1993; 6–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani, F.; Amirnia, R.; Rezaei-Chiyaneh, E.; Gheshlaghi, M.; von Cossel, M.; Siddique, K.H.M. Optimizing essential oil, fatty acid profiles, and phenolic compounds of dragon’s head (Lallemantia iberica) intercropped with chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) with biofertilizer inoculation under rainfed conditions in a semi-arid region. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2022, 69, 1687–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, Y.; Amirnia, R.; Rezaei-Chiyaneh, E.; Ghiyasi, M.; Razavi, B.S.; Siddique, K.H.M. Co-Inoculation of mycorrhizal fungi with bacterial fertilizer along with intercropping scenarios improves seed yield and oil constituents of sesame. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 2258–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, B.; Pirzad, A.; Jalilian, J. Yield-related biochemical response of understory mycorrhizal yellow sweet clover (Melilotus officinalis L.) to drought in agrisilviculture. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2020, 67, 1603–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H. Determination of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1987, 148, 350–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.T.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejera, N.A.; Campos, R.; Sanjuan, J.; Lluch, C. Nitrogenase and antioxidant enzyme activities in Phaseolus vulgaris nodules formed by Rhizobium tropid isogenic strains with varying tolerance to salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, W.F.; Fridovich, I. Assaying for superoxide dismutase activity: Some large consequences of minor changes in conditions. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 161, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Liu, R.H.; Nock, J.F.; Holliday, D.; Watkins, C.B. Temperature and relative humidity effects on quality, total ascorbic acid, phenolics and flavonoid concentrations, and antioxidant activity of strawberry. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 45, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Chiyaneh, E.; Mahdavikia, H.; Alipour, H.; Dolatabadian, A.; Battaglia, L.M.; Harrison, T.M. Biostimulants alleviate water deficit stress and enhance essential oil productivity: a case study with savory. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, M.M.; Algwaiz, H.I.M.; Waheed, H.; Ashraf, M.; Mahmood, A.; Li, F.M.; Attia, K.A.; Nadeem, M.A.; AlKahtani, M.D.; Fiaz, S.; Nadeem, M. Ridge-furrow mulching enhances capture and utilization of rainfall for improved maize production under rain-fed conditions. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Feng, B.L. Straw mulching improved yield of field buckwheat (Fagopyrum) by increasing water-temperature use and soil carbon in rain-fed farmland. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Chai, Q.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Chang, L.; Lan, X.; Cheng, H.; Chai, S. Plastic film mulching increases yield, water productivity, and net income of rain-fed winter wheat compared with no mulching in semiarid Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 262, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Song, D.; Pu, X.; Dang, P.; Qin, X.; Siddique, K.H. Effect of different straw returning measures on resource use efficiency and spring maize yield under a plastic film mulch system. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 134, 126461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chen, H.; Ding, D.; Zhang, T.; Li, C.; Luo, X.; Chu, X.; Feng, H.; Wei, Y.; Siddique, K.H. Plastic film mulching affects field water balance components, grain yield, and water productivity of rainfed maize in the Loess Plateau, China: A synthetic analysis of multi-site observations. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 266, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, S.; Mirlohi, A.; Sabzalian, M.R.; Saeidi, G.; Koçak, M.Z.; Hano, C. Water stress and seed color interacting to impact seed and oil yield, protein, mucilage, and secoisolariciresinol diglucoside content in cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). Plants 2023, 12, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Yan, B.; Gao, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, P.; Zhao, B.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y. Agronomic cultivation measures on productivity of oilseed flax: A review. Oil Crop Sci. 2022, 7, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanvand, R.K.; Jalal-Abadi, A.L.; Abdali Mashhadi, A.; Kochekzadeh, A.; Siyahpoosh, A. The effect of different types of mulch and different cultivation methods on the quantitative and qualitative traits of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) in Ahvaz climate. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2023, 24, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Wen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, T.; Li, S.; Guan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Su, S. Relationship of soil microbiota to seed kernel metabolism in camellia oleifera under mulched. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 920604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahangdale, N.; Kumawat, N.; Jadav, M.L.; Bhagat, D.V.; Singh, M.; Yadav, R.K. Symbiotic efficiency, productivity and profitability of soybean as influenced by liquid bio-inoculants and straw mulch. Int. J. Bio-resource Stress Manag. 2022, 13, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikhazaleh, M.; Ramroudi, M.; Galavi, M.; Ghanbari, S.A.; Fanaei, H.R. Effect of potassium on yield and some qualitative and physiological traits of safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) under drought stress conditions. J. Plant Nutr. 2023, 46, 2380–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarzadeh, S.; Arena, C.; Vitale, E.; Rahimi, A.; Mirzapour, M.; Nasar, J.; Kisaka, O.; Sow, S.; Ranjan, S.; Gitari, H. Impact of different fertilizer sources under supplemental irrigation and rainfed conditions on eco-physiological responses and yield characteristics of dragon’s head (Lallemantia iberica). Plants 2023, 12, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroof, T.; Tahir, M.; Zahid, N.; Khan, M.N.; Younas, M.T.; Shahzad, J.; Zafar, T.; Zeeshan, M.; Pervaiz, A.Y.A. Effect of different mulching materials on weed emergence and growth characteristics of strawberry under rainfed condition at Rawalakot Azad Jammu and Kashmir. J. App. Res. Plant Sci. 2024, 5, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Z.; Zeng, H.; Fan, J.; Lai, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Cheng, M.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, P. Effects of plant density, nitrogen rate and supplemental irrigation on photosynthesis, root growth, seed yield and water-nitrogen use efficiency of soybean under ridge-furrow plastic mulching. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 268, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Zahedi, S.M. Effects of deficit irrigation and mulching on morpho-physiological and biochemical characteristics of konservolia olives. Gesunde Pflanz 2020, 72, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, F.; Amirnia, R.; Rezaei-Chiyaneh, E.; Gheshlaghi, M.; von Cossel, M.; Siddique, K.H.M. Alleviating plant water stress with biofertilizers: A case study for dragon’s head (Lallemantia iberica) and chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) in a rainfed intercropping system. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2023, 17, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Wang, J.J.; Asad Naseer, M.; Saqib, M.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Ihsan, F.; Xiaoli, C.; Xiaolong, R.; Hussain, S.; Ramzan, H.N. Water stress memory in wheat/maize intercropping regulated photosynthetic and antioxidative responses under rainfed conditions. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perveen, S.; Parvaiz, M.; Shahbaz, M.; Saeed, M.; Zafar, S. Triacontanol positively influences growth, yield, biochemical attributes and antioxidant enzymes of two linseed (Linum usitatissimum l.) accessions differing in drought tolerance. Pakistan J. Bot. 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarzadeh, S.; Jalilian, J.; Pirzad, A.; Jamei, R.; Petrussa, E. Fodder value and physiological aspects of rainfed smooth vetch affected by biofertilizers and supplementary irrigation in an agri-silviculture system. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 96, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałata, A.; Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R.; Kalisz, A.; Moreno-Ramón, H. Impacts of alexandrian clover living mulch on the yield, phenolic content, and antioxidant capacity of leek and shallot. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Miao, M. Effect of furrow straw mulching and straw decomposer application on celery (Apium graveolens L.) production and soil improvement. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, S.M.; Mašković, P. Phenolic compounds, antioxidant and cytotoxic activity in berry and leaf extracts of black currant (Ribes nigrum L.) as affected by soil management systems. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2020, 62, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałata, A.; Sękara, A.; Pandino, G.; Mauromicale, G.; Lombardo, S. Living mulch as sustainable tool to improve leaf biomass and phytochemical yield of Cynara cardunculus var. altilis. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murariu, O.C.; Lipsa, F.D.; Cârlescu, P.M.; Frunză, G.; Ciobanu, M.M.; Cara, I.G.; Murariu, F.; Stoica, F.; Albu, A.; Tallarita, A.V.; et al. The Effect of Including Sea Buckthorn Berry By-Products on White Chocolate Quality and Bioactive Characteristics under a Circular Economy Context. Plants 2024, 13, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimia, L.M.; Patriche, C.V.; Murariu, O.C. The imparct of climate change on viticultural potential and wine grape varieties of a temperate wine growing region. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2018, 16(3), 2663–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murariu, F.; Voda, A.D.; Murariu, O.C. Researches on food safety assessment—Supporting a healthy lifestyle for the population from NE of Romania. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 305S, S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineată, I.; Murariu, O.C.; Sîrbu, S.; Tallarita, A.V.; Caruso, G.; Jităreanu, C.D. Effects of Ripening Phase and Cultivar under Sustainable Management on Fruit Quality and Antioxidants of Sweet Cherry. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Component | Treatment | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFD | RFD | RFD | RFD | SIF | SIF | SIF | SIF | SIVF | SIVF | SIVF | SIVF | ||

| C | V | PM | SM | C | V | PM | SM | C | V | PM | SM | ||

| 1 | Palmitic acid | 6.09 | 6.18 | 6.19 | 6.41 | 6.3 | 6.49 | 7.38 | 6.96 | 5.08 | 5.1 | 4.49 | 4.68 |

| 2 | Stearic acid | 5.08 | 5.29 | 5.78 | 5.53 | 5.61 | 5.67 | 5.5 | 5.66 | 5.15 | 5.09 | 4.97 | 5.45 |

| 3 | Oleic acid | 21.54 | 21.93 | 23.02 | 23.28 | 23.65 | 24.22 | 24.12 | 24.78 | 23.11 | 25.02 | 24.96 | 25.99 |

| 4 | Linoleic acid | 12.06 | 12.57 | 12.18 | 12.28 | 12.05 | 12.15 | 12.32 | 12.66 | 10.67 | 12.85 | 12.58 | 12.91 |

| 5 | Linolenic acid | 50.26 | 52.56 | 51.99 | 51.71 | 50.73 | 50.86 | 49.05 | 51.46 | 41.09 | 41.3 | 38.31 | 40.46 |

| 6 | Arachidic acid | 0.65 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Source of variation | Relative water content | Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll b | Carotenoids | Total soluble sugars | Proline content | CAT | SOD | Total phenol content | DPPH radical scavenging capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulch (M) | ** | ** | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Irrigation regime (IR) | * | * | n.s. | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | ** | ** |

| M x IR | n.s. | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).