1. Introduction

In the past decade, increasing awareness of the harmful effects of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides has stimulated interest in organic agricultural practices [

1,

2,

3]. The risks associated with agriculture have resulted in the application of synthetic pesticides, which, while advantageous for crop yield and protection, raise concerns about their long-term detrimental effects on cropping systems [

4,

5]. The development of innovative, efficient, and ecologically friendly methods for improving plant growth and crop protection is an urgent need at the present time. Biostimulants, characterized as agents or materials apart from nutrients and chemicals (pesticides, insecticides etc.) that modulate physiological processes in plants to promote growth, have gained prominence over the past decade [

6]. The worldwide market for these products was valued at

$2.6 billion in 2019, and experts anticipate it will reach over

$4 billion in 2025 [

7].

Nevertheless, certain botanicals have been identified as biostimulants [

8,

9]. Using plant biostimulants that enhance nutrient absorption and use efficiency could potentially help reduce the need for mineral fertilizers [

10,

11]. Moreover, a peer-reviewed scientific evaluation is necessary to comprehend plant-derived substances, including biostimulants [

12]. Thus, recognizing and comprehending the functional bioactivity of botanicals may hold significant value for both the agricultural sector and consumers [

8,

9]. Researching the role of a botanical compound within the receiving plant may necessitate careful observation due to the fact that plants, being sessile organisms, have developed specialized mechanisms to detect and process various stimuli [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Recently, many studies have gone into more detail and explained different biological processes that happen in plants when they connect with their ultimate environment [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Some studies revealed stimulatory responses in the growth of vegetables with improved plant height, number of leaves, root growth, fresh and dry weight, while significant alterations were indicated in plant metabolites such as chlorophyll, carotenoids, soluble sugars, and antioxidative enzymes, etc., due to aqueous garlic extract applications [

12].

Plants have developed highly efficient enzymatic antioxidant defense mechanisms to scavenge reactive oxygen species and safeguard cells from oxidative damage [

22,

23]. Secondary metabolites derived from plants have emerged as a focal point for numerous scientists aiming to comprehend their chemistry [

24,

25,

26,

27], and origin [

28,

29]. Metabolic pathways that are derived from primary metabolic pathways are utilized by the cell to produce secondary metabolites, including phenolic acids and flavonoids. Commonly, plant generate phenolic acids and flavonoids through constitutive production during the course of normal growth and development [

30]. Furthermore, certain plant extract treatments have the potential to enhance the levels of total phenol and flavonoid contents, which were significantly elevated following the treatment of spinach leaves with an

Ascophyllum nodosum extract (1 g/L) [

31]. The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging method is commonly employed to assess the antioxidant activity of plant extracts [

32]. Some scientists observed a strong correlation between the antioxidant capacity of vegetable samples and their total phenolic content [

33].

The plant kingdom is home to numerous antioxidant secondary metabolites [

34]. Antioxidants are compounds that mitigate oxidative damage to biological systems by donating electrons to free radicals, rendering them harmless [

35]. Plants employ advanced mechanisms involving antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POD), to manage ROS [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Garlic extracts or compounds derived from garlic have the potential to stimulate the biology of receiver plants, according to the growing body of knowledge regarding the chemistry of garlic aqueous extracts, which contain a variety of growth-promoting factors such as vitamins, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, carbohydrates, enzymes, and so on [

40,

41,

42,

43]. The secondary plant metabolites of guava consist of a variety of phytoconstituents, including phenolics, flavonoids, carotenoids, and terpenoids [

44].

There is a lack of knowledge regarding the effectiveness and mechanisms of action of some water extracts when it comes to their role as biostimulators in plants. A fresh study was conducted to investigate the impact of specific water extracts applied at various timing of soil sprays on cucumber, tomato, kale, lettuce, and rice cultivated in greenhouse conditions. This study examines the impact of specific water extracts on secondary metabolites and antioxidant enzymes when extracts sprayed at various growth stages of each crop.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparing Plant Materials and Extracts

A variety of vegetables were utilized as test crops, including cucumbers (cv. Ho Dong Cheong Jang F1), tomatoes (cv. Dotaerang Myeongpum), kale (cv. Saeron kale), and lettuce (cv. Cheong Ha Cheong Chi Ma). These vegetable seeds were purchased from Asia Seed Korea Co., Ltd. (Seoul, Korea). Rice seeds (cv. Hopyeong) were provided by the Jeollanamdo Agricultural Research and Extension Service. Plants of the species

Psidium guajava, Aloe vera, Allium sativum, and

Medicago sativa were used to produce the water extracts that were utilized in this investigation. In a previous study [

45], these water extracts showed the highest rates of enhancement in rice seedling development among 17 tested extracts, which led to their selection.

2.2. Conditions for the Cultivation of Plants and Their Treatment

The rice seeds were soaked in distilled water for an entire day (24 h). Each pot (6 cm in height and 6 cm in diameter) was filled with roughly 130 g of commercial soil for rice nursery media (No. 1 Sunghwa, Boseong, South Korea). After two weeks of planting (three to four-leaf stage), three seedlings of rice were transferred to each pot. For the purpose of cultivating vegetables, approximately 200 g of commercial soil for horticultural media (No. 2 Sunghwa, South Korea) was placed inside each pot (16 cm in height and 16 cm in diameter). One seedling from each vegetable was put into each pot at the two to three-leaf stage. The growth-enhancing effects of four water extracts were examined during various growth stages of all crops [

45]. The application times were different for each growth stage (1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks post-sowing). A soil drench was used three to five days after transplanting to apply four different extracts (10 mL per pot) at amounts of 0.1 and 0.5%. Distilled water served as the control treatment. Urea at 0.6% was used as a benchmark for assessing the growth efficacy of the extracts. The pots were maintained in a greenhouse for two weeks following the extract treatments. The greenhouse parameters were 14 hours of illumination and 10 hours of obscurity, with a diurnal/nocturnal temperature of 30 ± 2°C/ 20 ± 3°C, 70% relative humidity, and a photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) of 500 µmol m

-2 s

-1. A measurement of the shoot fresh weight was taken at 14 days after treatment (DAT). All studies were conducted in duplicate with three duplicates for each treatment.

2.3. Temporal Impact of Specific Water Extracts on Secondary Metabolite Synthesis in Rice and Vegetables

Previous research [

45] indicated that extracts of

P. guajava and

A. sativum at 0.1 and 0.5% resulted in the greatest rates of shoot fresh weight in cucumber, kale, and rice crops, therefore those were the ones used to analyze the secondary metabolites and antioxidative enzymes. Samples were taken from three plants in each of the three groups at two and three weeks following the extracts’ application. The leaf samples were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen and preserved at -80°C for later biochemical investigation.

2.3.1. Determination of Quantum Yield, Total Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Contents

The chlorophyll α fluorescence of photosystem II (PSII), specifically the quantum yield (Fv/Fm) of rice, cucumber, and kale crops, was assessed at 7 and 14 days after treatment (DAT). A soil drench was used to administer 10 mL of water extracts at concentrations of 0.1 and 0.5% to each plant for a period of 2 and 3 weeks after sowing (WAS). The second leaves of rice, cucumber, and kale plants were chosen at 7 and 14 days after transplanting (DAT) to be measured with a portable pulse modulation fluorometer (Fluorpen FP10, Photon Systems Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic). Prior to the measurements, the fronts were darkened for 15 min to ensure the activation of all antenna pigments.

Analyses of chlorophyll and carotenoids were conducted following a previously established method [

46]. Seedling leaves (0.5 g) from each treatment group were homogenized in a 100% methanol solution. The extracts underwent centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 3 min, after which the absorbance of the supernatant was spectrophotometrically measured at 470, 652, and 665 nm. The calculation of chlorophyll and carotenoid contents was performed using the subsequent equation:

Total chlorophylls (Ca+b) = 1.44 A665.2 + 24.93 A652.4

Total carotenoids (Cx+c) = [1000 A470 − 1.63 Ca − 104.96 Cb]/221

2.3.1. Determination of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity, Total Phenol, and Flavonoid Contents

The total phenol and flavonoid levels, as well as the DPPH radical scavenging activity, were detected using a method that has been reported before [

47]. 0.5 g of the dried plant samples were combined with 10 mL of 99.9% ethanol, shaken at 120 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 24 h at a temperature of 27°C in a shaking bath, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min using a high-speed refrigerated centrifuge (VS-24SMTI, Vision Scientific Co., Ltd., Daejeon, South Korea), these activities were then analyzed.

To assess DPPH radical scavenging activity, a mixture was prepared consisting of 0.1 mL of the extract, 0.5 mL of a 0.1 M acetate buffer solution (pH 5.5), 0.25 mL of 0.5 mM DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), and 0.4 mL of ethanol. This mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The solution was examined with a 517 nm of UV spectrometer (SPECTROstar Nana, BMG LABTECH, GmbH, Offenburg, Germany) to determine the constituents. Ascorbic acid served as a positive control, and the DPPH radical scavenging activity of the extracts was determined using the following formula:

Ac represents the absorbance of the control, while As denotes the absorbance of the test samples [

48].

After combining 0.2 mL of the extract with 0.6 mL of distilled water and 0.2 mL of Folin-Denis reagent, the mixture was agitated for 5 min to ascertain the total phenol concentration. The solution was combined with 0.2 mL of Na2CO3 and let to remain at room temperature for 1 h after 5 min. Then, it was measured at 640 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (SPECTROstar Nana, BMG LABTECH, GmbH, Offenburg, Germany). The standard values were derived from ferulic acid concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 µg/mL, and total phenol values were determined using a standard curve. Values are presented as the mean (mg of ferulic acid equivalents per g of extracted sample).

Total flavonoid content was measured by combining 0.2 mL of the extract with 0.45 mL of 95% ethanol, 0.0.3 mL of 10% AlCl3, 0.03 mL of 1 M potassium acetate, and 0.79 mL of distilled water. The mixed solution was allowed to stand for 40 min at room temperature, and the absorbance was measured at 640 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (SPECTROstar Nana, BMG LABTECH, GmbH, Offenburg, Germany). Standard values were derived using quercetin acid at concentrations of 0-5 µg/mL, and total flavonoid values were determined based on a standard curve. All values are presented as the mean (mg of quercetinic acid equivalents per g of extracted sample).

2.3.1. Determination of Antioxidative Enzyme Activities

To get the enzymes out of the frozen leaves, about 0.5 g of them were mixed with 3.75 mL of a 100 mM buffer solution (pH 7.5) that had 2 mM EDTA, 1% PVP, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, C7H7FO2S). The mixture was then broken up with a mortar and pestle and put in a refrigerated centrifuge (VS-24SMTI, high-speed refrigerated centrifuge, Vision Scientific Co., Ltd., Daejeon, South Korea) at 14,000 × g for 20 min.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was assessed using the method outlined in [

49], incorporating several modifications [

50,

51]. A reaction mixture of 230 µL comprised 1.26 mM NBT (Nitroblue tetrazolium), 260 mM riboflavin, 260 µM methionine, 2 mM EDTA, and 200 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.0, supplemented with 20 µL of enzyme extract, resulting in a total volume of 300 µL. The mixture in the test tubes was exposed to light at an intensity of 78 mmol photon s

-1 m

-2 for 10 min, after which the absorbance at 560 nm was measured. A nonirradiated reaction mixture that did not exhibit color functioned as the control, and its absorbance was subtracted from A560 of the reaction solution. One unit of SOD activity is defined as the quantity of enzyme necessary to achieve 50% inhibition of the NBT reduction rate at 560 nm (SPECTROstar Nana, BMG LABTECH, GmbH, Offenburg, Germany).

The activities of catalase (CAT) and guaiacol peroxidase (GPOD) were determined by employing a method that had been published in the past [

52,

53]. Spectrometer readings taken at 240 nm for 1 min (SPECTROstar Nana, BMG LABTECH, GmbH, Offenburg, Germany) were used to determine CAT activity by measuring the rate of H

2O

2 breakdown. The reaction mixture comprised 150 µL of 200 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 15 µL of 15 mM H

2O

2, 135 µL of distilled water, and 5 µL of enzyme extract, resulting in a total volume of 300 µL that initiated the reaction. The oxidation of guaiacol during GPOD activity was assessed by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 470 nm over a duration of 1 min using a SPECTROstar Nana, BMG LABTECH, GmbH, Offenburg, Germany. Ingredients in the reaction mixture included 5 µL of 200 mM guaiacol, 280 µL of 200 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and 15 µL of enzyme extract. The reaction commenced with the addition of 5 µL of 40 mM H

2O

2.

Ascorbate peroxide (APOD) activity was determined by its absorbance at 290 nm at the beginning rate of reduction in ascorbate concentration [

54]. The total volume of the reaction mixture was 300 µL, and it consisted of 150 µL of 200 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 30 µL of 5 mM ascorbate, 12 µL of 20 mM H

2O

2, 30 µL of distilled water, and 15 µL of enzyme extract. The addition of H

2O

2 was the catalyst that started the reaction, and a UV spectrophotometer (SPECTROstar Nana, BMG LABTECH, GmbH, Offenburg, Germany) was used to quantify the change in absorbance.

2.4. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

The experiment was set up with a factorial layout and three replicates in a completely randomized design. Multiple comparisons were performed to assess the disparities in the variables among the components. Substantial differences were assessed utilizing an analysis of variance (ANOVA) through a statistical software program (Statistix version 8.0). When a substantial difference was observed, the means were distinguished utilizing Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) and Least significant difference (LSD) tests at α=0.05.

3. Results

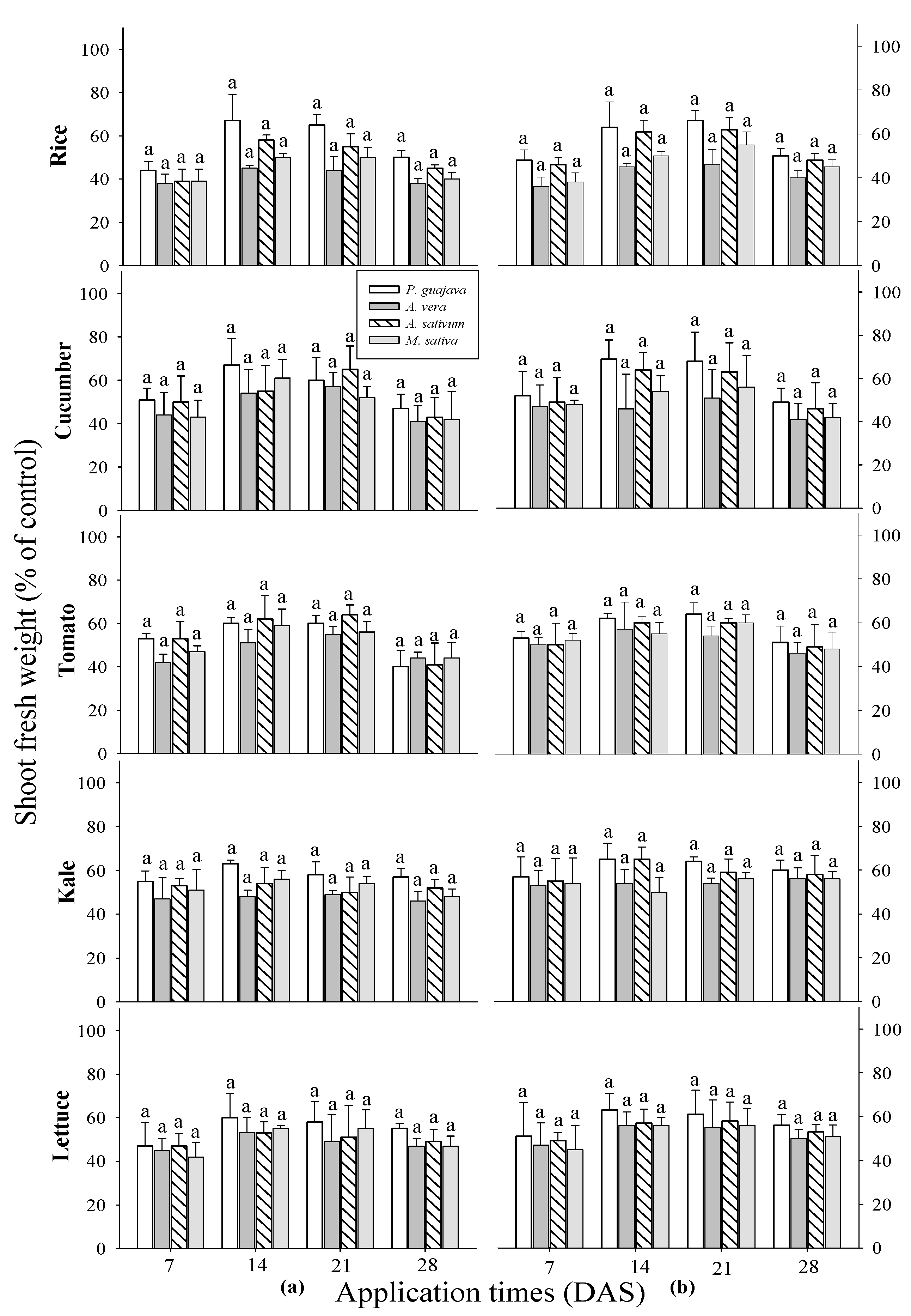

3.1. Impact of Selected Water Extracts on Application Timing During Different Growth Phases of Rice and Vegetables

The results of all application times showed that there was no discernible difference between the crops and the extracts (

Figure 1). All test receiver plants demonstrated an increase in the shoot fresh weight following the application of four water extracts, as evidenced in subsequent observations. However, fruity vegetables such as cucumber and tomato shoot fresh weight increased by 27-52% and 29-53% one week after sowing, 52-73% and 42-61% two weeks later, 43-79% and 40-64% three weeks later, and 39-65% and 29-55% four weeks later after. For leafy vegetables such as kale, and lettuce, extracts sprayed one week after sowing increased shoot fresh weight by 33-57%, 37-51%; two weeks later, 41-65%, 43-63%; three weeks later, 41-64%, 44-61%; and four weeks later, 38-60%, 42-56%. The rice shoots fresh weight increased by 28-48% one week after sowing; two weeks later, 35-67%; three weeks later, 36-66%; and four weeks later, 26-50%. Therefore, it means that each of these extracts has the ability to raise the shoot fresh weight of all tested crops at any stage of growth and at any time of application. Furthermore, the highest shoot fresh weights were observed in response to P. guajava extract, followed by A. sativum extract across all tested plants.

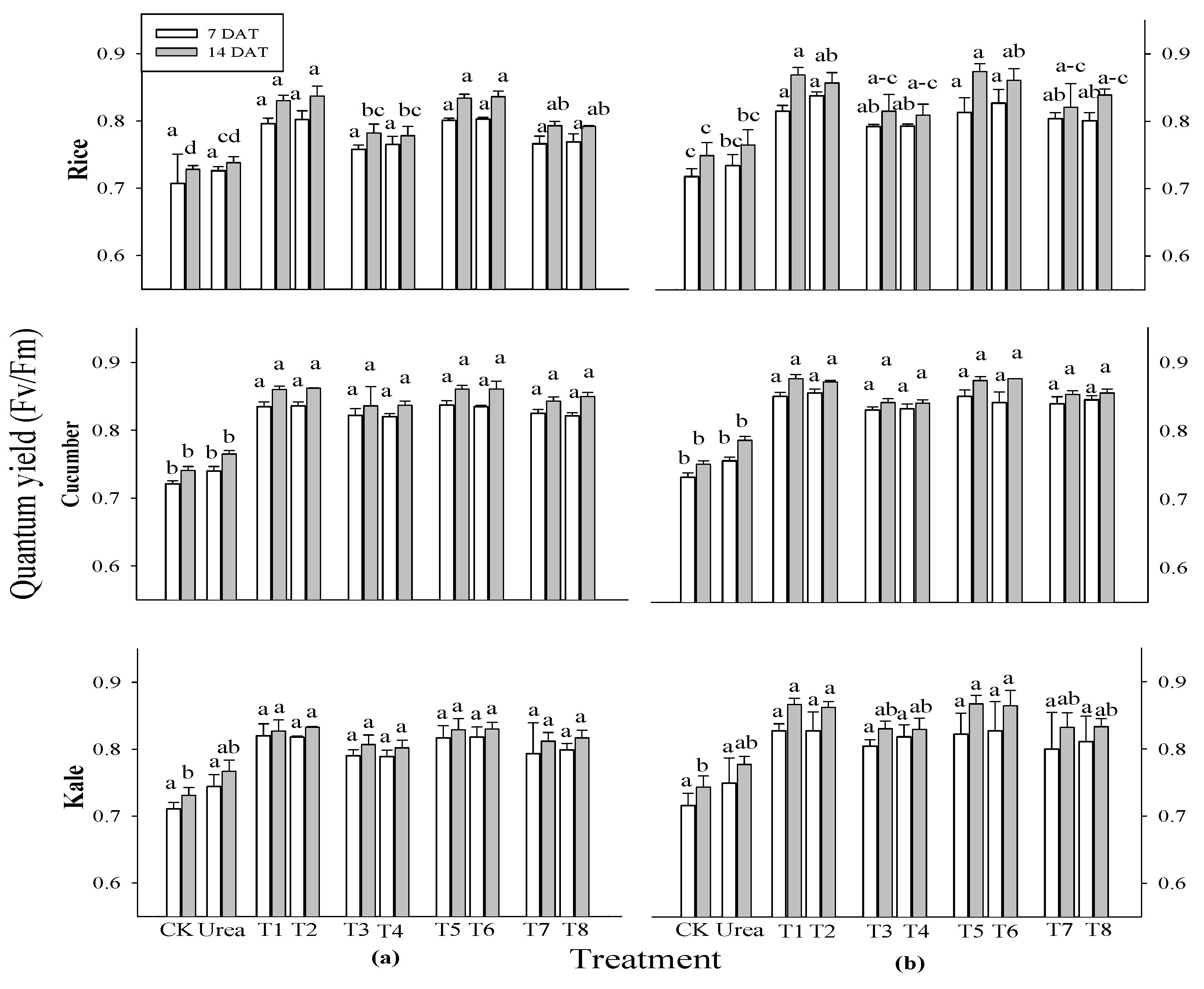

3.2. Influence of Selected Water Extracts on Secondary Metabolites Production in Rice and Vegetables

Following the outcomes of the prior experiment, rice, cucumber, and kale crops were chosen to evaluate photosynthetic efficiency at 7 and 14 days after transplantation (DAT). During the 7 DAT (

Figure 2), there was a significant difference between all treatments in rice at 3 weeks after sowing (WAS), cucumber at both 2 and 3 WAS, but there was no significant difference in rice at two WAS or kale at either 2 or 3 WAS. The photosynthetic efficiency of all crops at 2 and 3 WAS varied significantly different at 14 DAT. Every single extract treatment outperformed the control and urea treatments in terms of photosynthetic performance. The treatments with extracts of

P. guajava and

A. sativum made all tested plants’ photosynthesis go up more than the treatments with extracts of

A. vera and

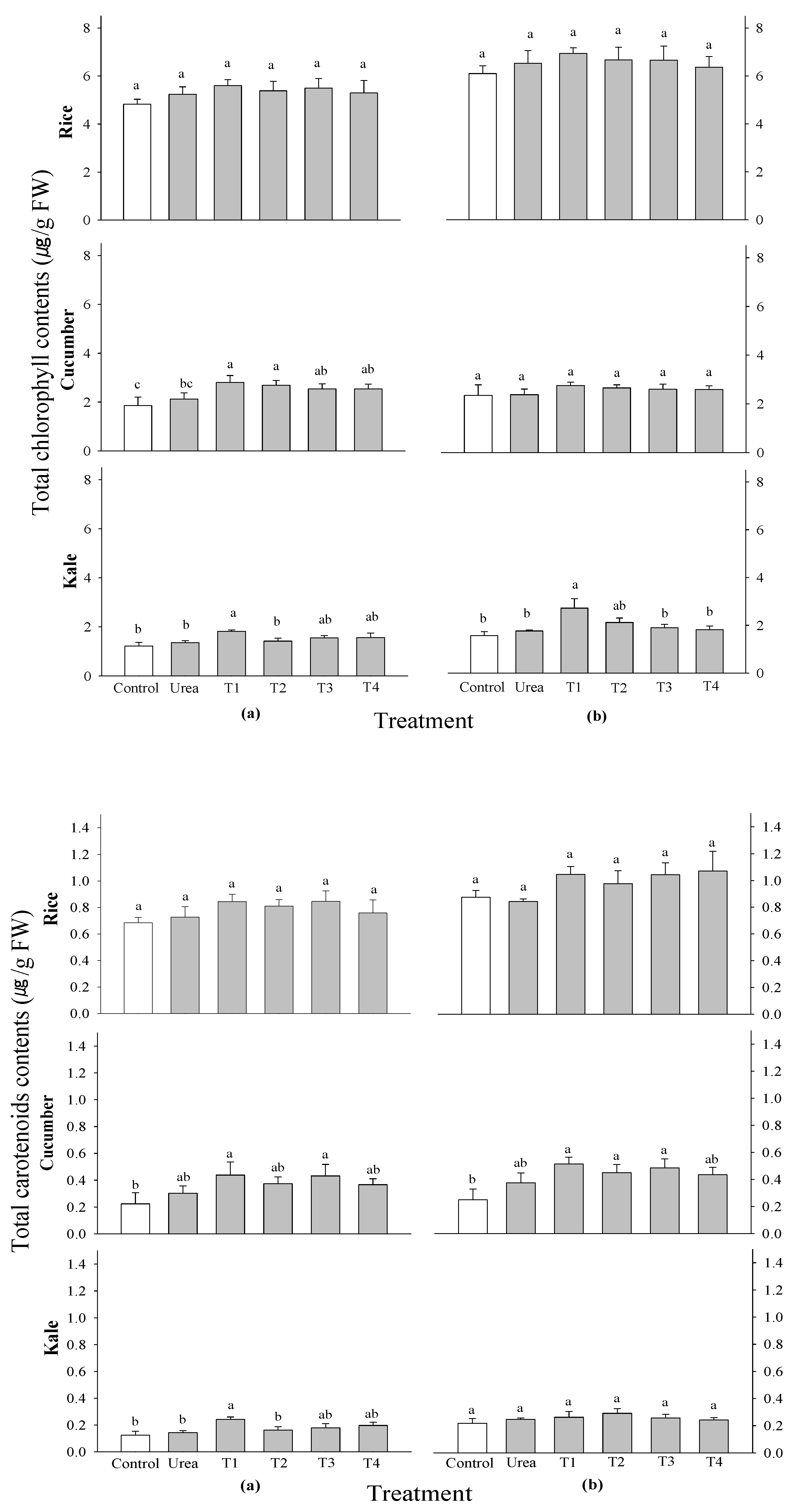

M. sativa. No significant differences were observed in total chlorophyll and carotenoid contents among all treatments across all test crops and application times (

Figure 3). When it came to overall chlorophyll concentrations, however, cucumbers only showed a significant difference at 2 WAS. The cucumber that had been treated with 0.1 and 0.5% of

P. guajava and

A. sativum extracts at 2 WAS had the most total chlorophyll, which shows that they help make nutrients more available.

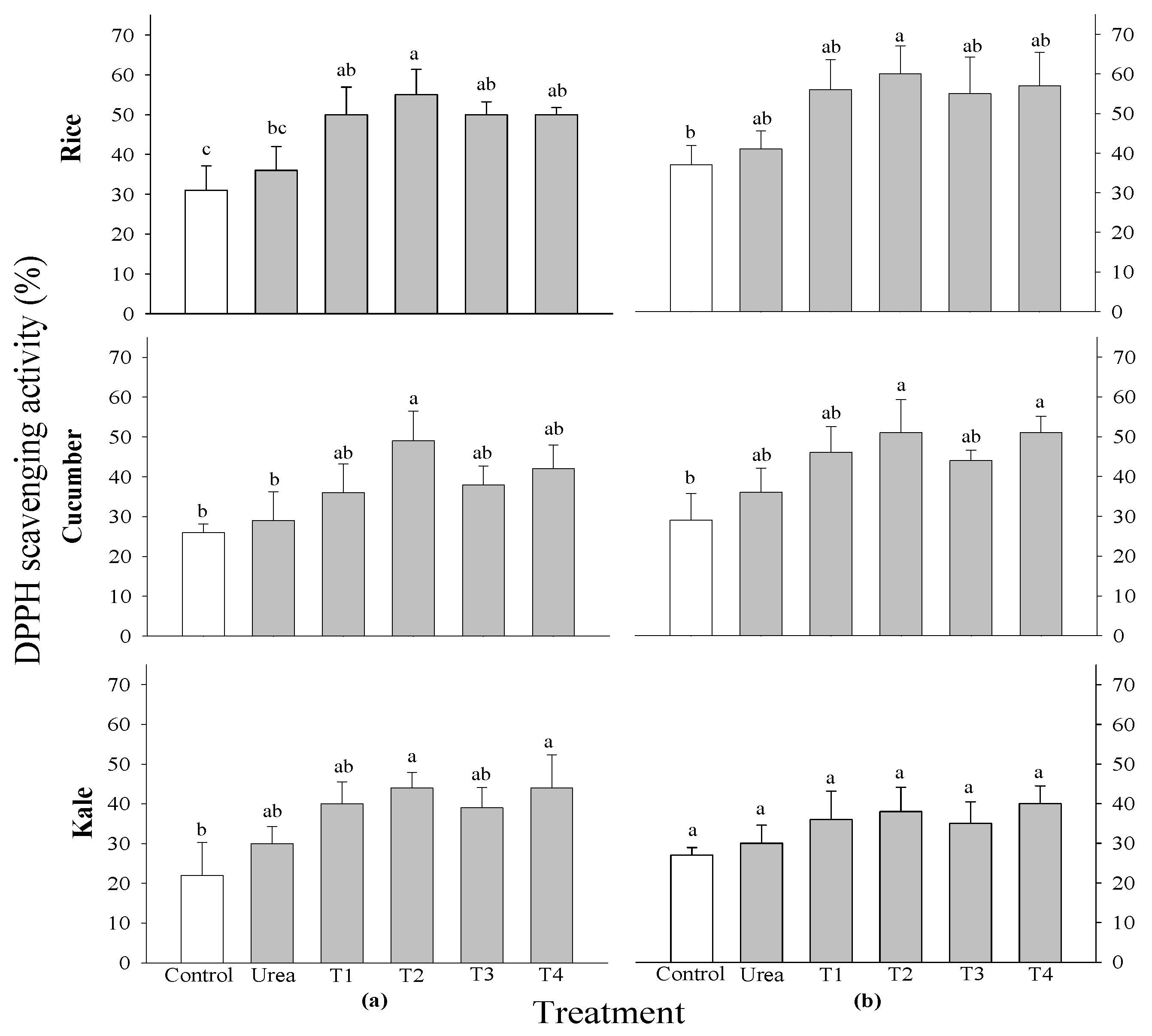

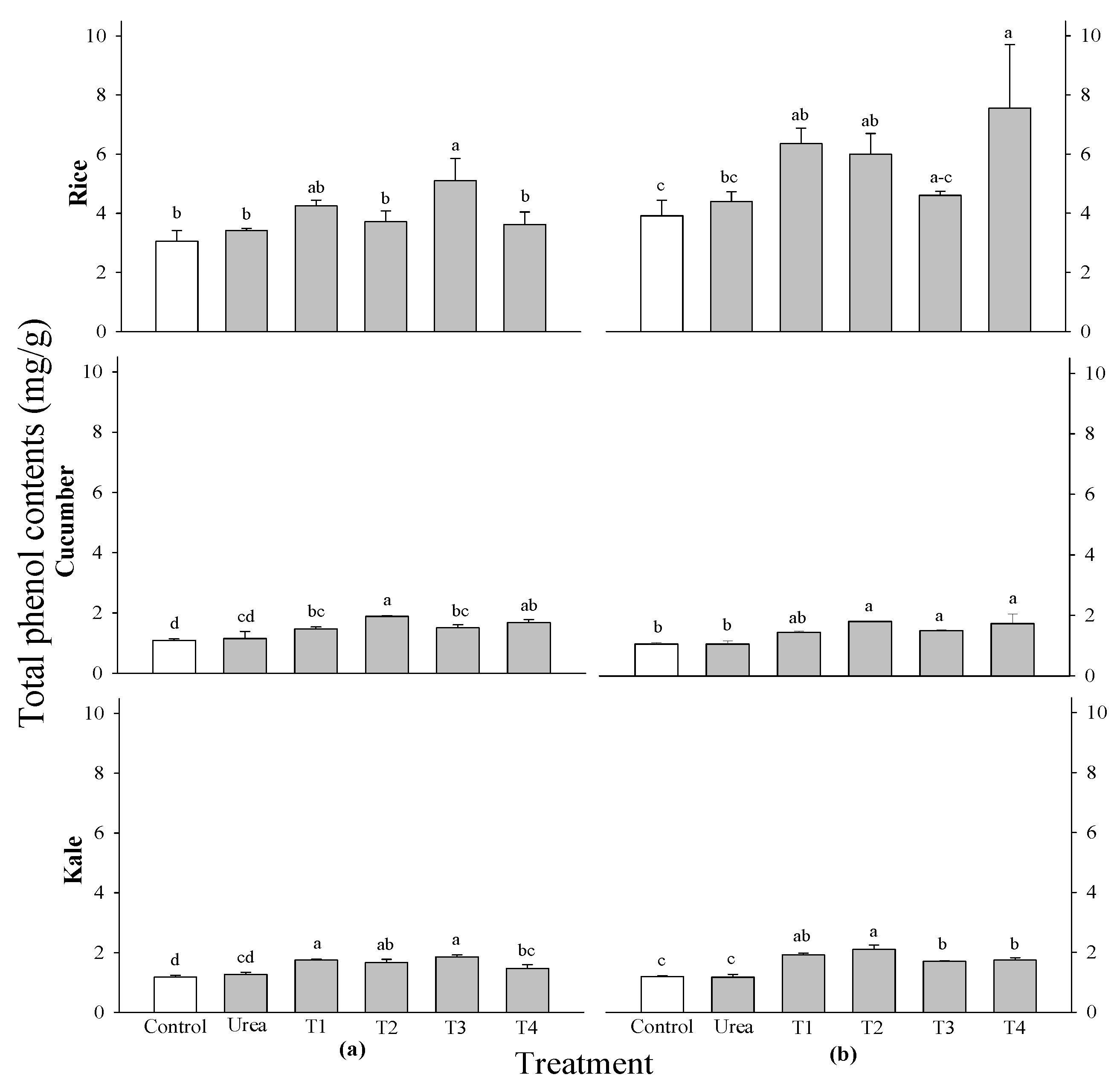

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of all tested crops did not exhibit significant differences across all treatment levels and growth stages (Figure 4). There was a notable difference in the DPPH radical scavenging activity of rice at 2 WAS. The highest concentration was observed in rice treated with 0.5%

P. guajava extracts. A significant difference in total phenol contents was observed in cucumber at 2 WAS and in kale at 2 and 3 WAS; however, no significant difference was noted in the rice crop (Figure 4). The results showed that the maximum shoot fresh weight was observed in cucumbers treated with 0.5%

P. guajava extract at 2 WAS, followed by kale treated with 0.1%

P. guajava and

A. sativum extract at 2 WAS, and finally 0.5%

P. guajava at 3 WAS. A notable difference in total flavonoid contents was observed in kale at 2 WAS and in rice at 2 and 3 WAS; however, no significant difference was found in the cucumber crop (

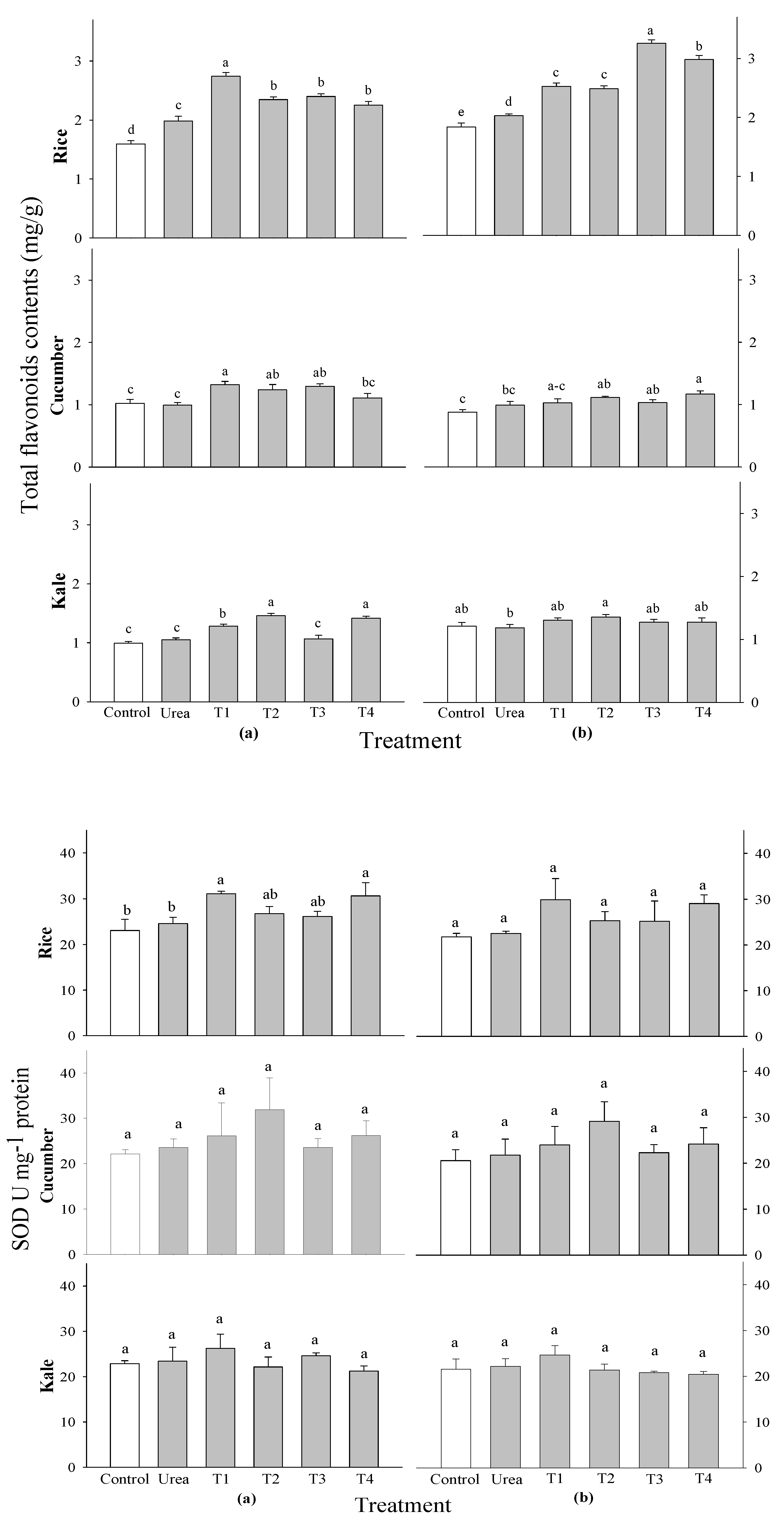

Figure 5). The rice crop showed the maximum flavonoid content in a 0.1%

P. guajava and 0.1%

A. sativum treatment at 2 WAS, whereas the kale crop showed the highest flavonoid content in a 0.5%

P. guajava and

A. sativum treatments at 2 WAS.

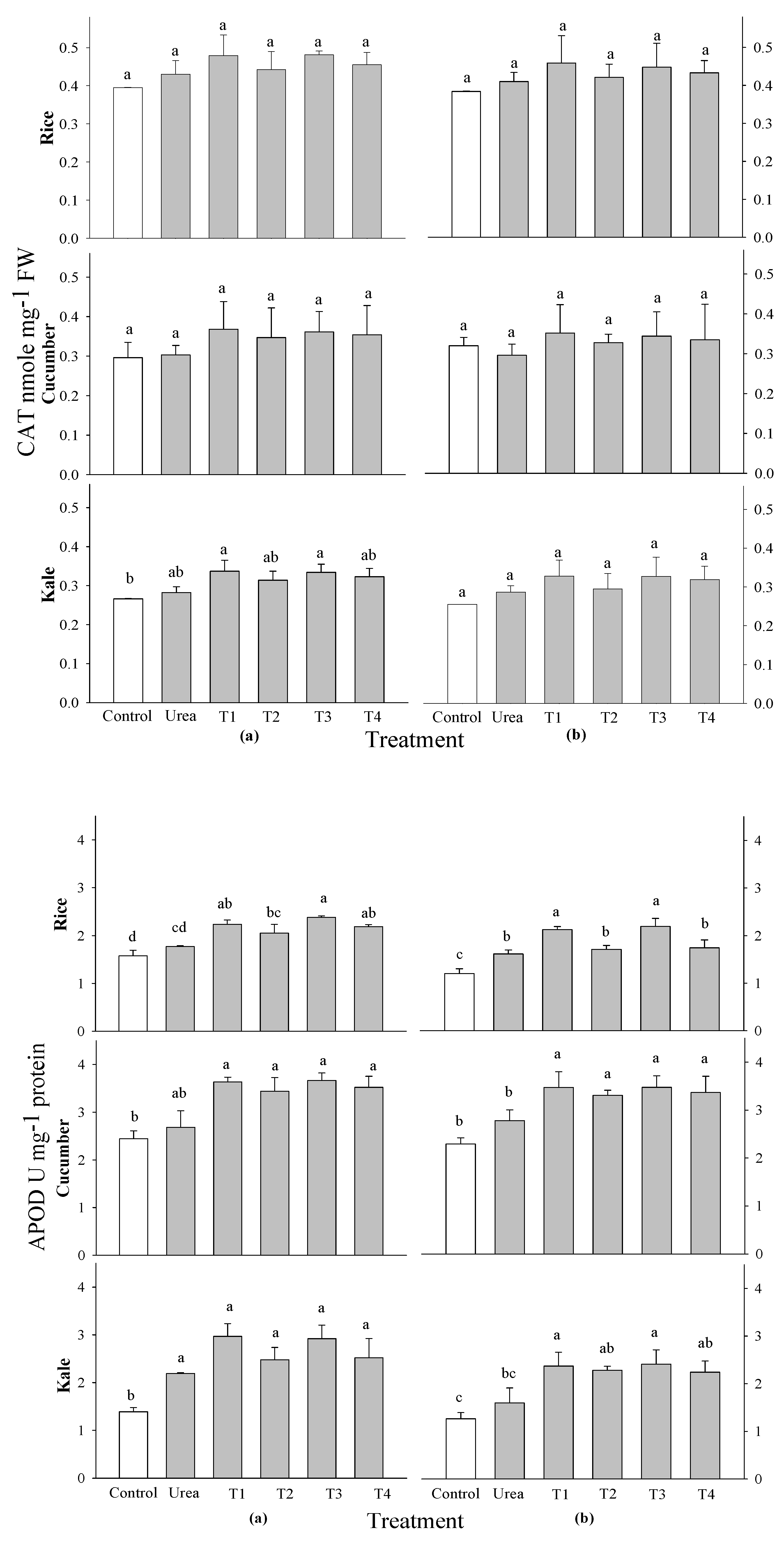

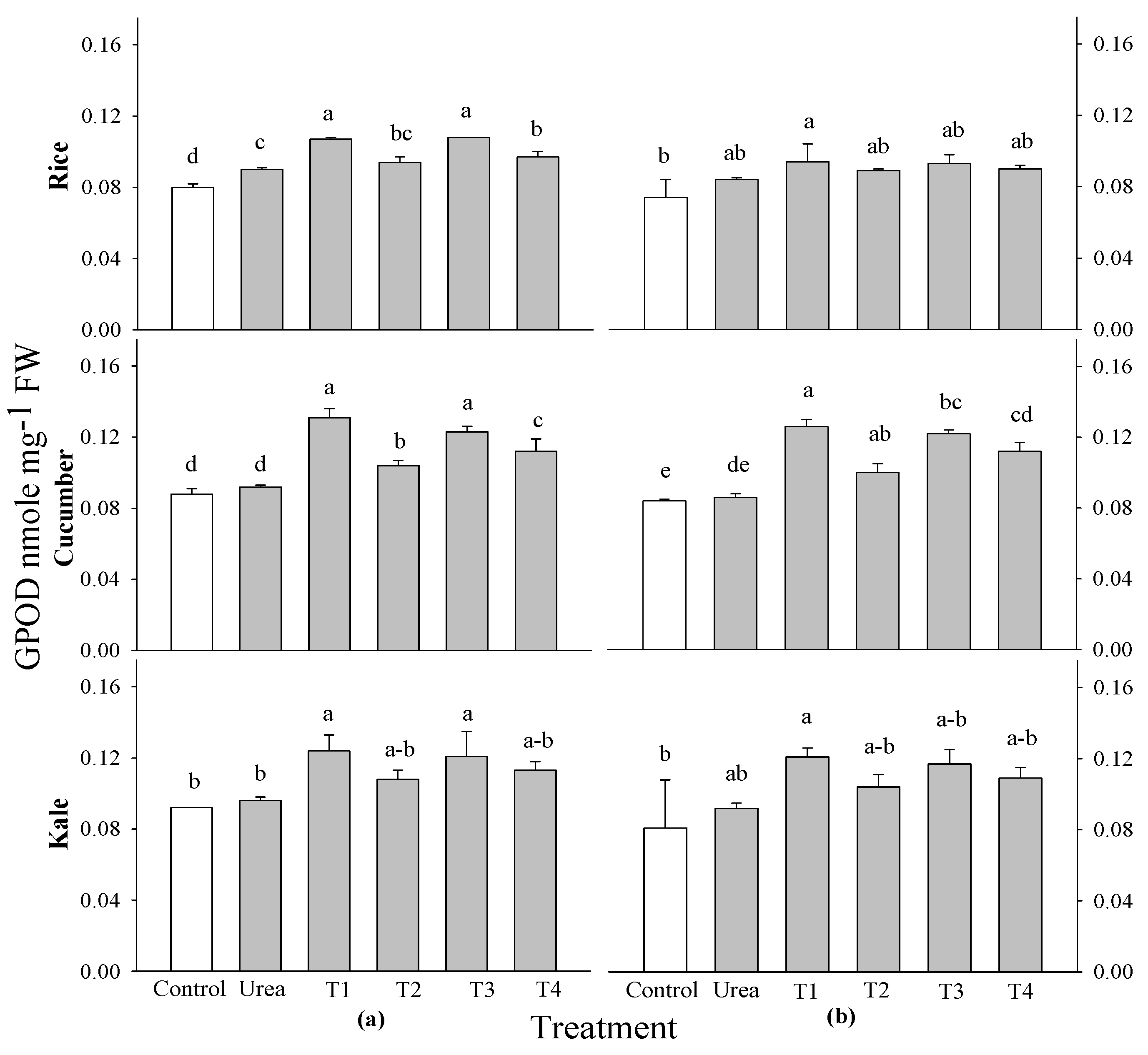

When 0.1 and 0.5% of

P. guajava and

A. sativum extracts were added to cucumber, kale, and rice plants at 2 and 3 WAS, their activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), guaiacol peroxide (GPOD), and ascorbate peroxide (APOD) were tested. No significant changes were seen in the activities of SOD and CAT among all evaluated crops and treatment timings compared to the control. This rationale cannot be associated with SOD and CAT activities concerning the growth of rice and vegetables (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Nonetheless, there were markedly significant differences in APOD activity among all examined crops and application timings in comparison to the control. The peak APOD activity occurred in rice subjected to 0.1%

A. sativum at 2 and 3 WAS, cucumber treated with all extract applications at every time point, and kale treated with all extract applications at 2 WAS, as well as with 0.1%

P. guajava and

A. sativum extract treatments at 3 WAS (

Figure 6). Kale at 2 and 3 WAS and rice at 3 WAS did not exhibit a significant difference in GPOD activity. However, cucumber and rice did exhibit a significant difference at 2 and 3 WAS and 2 WAS, respectively, when compared to the control. The peak GPOD activity was recorded in 0.1% extracts of

P. guajava and

A. sativum applied to rice and cucumber crops at all application periods (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The effects of selected water extract on the shoot fresh weight of the crops studied varied with concentration, growth stage, and duration of treatment. Any of these extracts can be used at any stage of growth and at any time to increase the shoot fresh weight of all crops that have been evaluated. The eggplants that were treated showed growth and physiological reactions that were stimulated by the repeated application of aqueous garlic bulb extract and the plant’s growth stage [

55].

P. guajava extract at concentrations of 0.1 and 0.5% was shown to have the highest rates of shoot fresh weight, followed by

A. sativum extract at concentrations of 0.1 and 0.5% in all rice and vegetable crops. According to various studies [

56,

57], garlic is rich in sulfur compounds, enzymes, vitamins B and C, minerals (including Na, K, Zn, Mn, Mg, Ca, and Fe), carbohydrates, saponins, alkaloids, and flavonoids, and free sugars (including glucose, fructose, and sucrose). The results that guava (

P. guajava) leaves compost gives the best development in the Temulawak plant (

Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb) are supported by the fact that guava leaves are abundant in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, but the concentration of these elements varies according on the month in which the plant is growing [

58]. Consequently, it provides a well-rounded nutritional source for plant growth.

The efficacy of photosynthesis was enhanced in all extract treatments relative to the control and urea treatments. The photosynthesis of all plants increased more with

P. guajava and

A. sativum extracts than with

A. vera and

M. sativa extracts. The results substantiate prior findings that garlic root exudates elevate chlorophyll content, hence enhancing light energy absorption in tomato and hot pepper, which leads to a better photosynthetic rate [

59]. Nonetheless, a notable variation in the total chlorophyll content of cucumber was observed at 2 WAS. This aligns with a study indicating that the application of 4% garlic extract on pear transplants elevated nitrogen and potassium levels in the leaves, which is recognized to augment chlorophyll concentrations [

60]. The findings robustly corroborated prior research indicating that chlorophyll content is influenced by various treatments and may occasionally promote development and physiological circumstances [

61,

62,

63,

64].

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of rice at 2 WAS was shown to be significantly different. Furthermore, the highest level was discovered in rice that had 0.5% of

P. guajava extracts added to it. The notable DPPH radical scavenging activity of

F. religiose may be attributed to the presence of flavonoids and other polyphenols during extraction, as demonstrated in the present study [

65]. The antioxidant activity of extracts evaluated using DPPH assays exhibited a good correlation with the total phenolic and flavonoid content [

66]. Total phenol levels were significantly different in cucumber at 2 WAS and kale at 2 and 3 WAS, but not in rice crops. Moreover, it was discovered that certain phenolic acids at low concentrations increased the dry weight, number and length of secondary roots, as well as the length of main roots, in

Deschampsia flexuosa and

Senecio sylvaticus [

67]. The total flavonoid content of kale at 2 WAS and rice at 2 and 3 WAS was found to be significantly different from one another, however, the cucumber crop did not exhibit any significant differences. According to another study, cucumbers treated with fermented bone + fish extracts had a much higher total flavonoid content than control plants, whereas plants treated with other extracts produced fruit with flavonoid contents comparable to control plants [

68]. It is possible that the antioxidant properties of the selected plant extracts are mostly attributable to the phenolic and flavonoid groups [

69].

It was found that there were no significant variations in the SOD and CAT activities of any of the crops that were evaluated, nor were there any differences in the application periods that were connected to control. Nonetheless, there were markedly significant differences in APOD activity among all evaluated crops and application periods in comparison to the control. The GPOD activity of kale at 2 and 3 WAS and rice at 3WAS did not change substantially, respectively, but for cucumber at 2 and 3 WAS and rice at 2 WAS, there was a significant difference compared to the control. The actions of APOD and GPOD were examined at 2 and 2 WAS in rice, cucumber, and kale utilizing

P. guajava and

A. sativum at 0.1% concentrations. Spraying with aqueous garlic extracts promoted the activities of the enzymes that are responsible for antioxidant defense. Antioxidants and potentially ROS were activated by moderate application, resulting in improved plant growth. However, this effect was suppressed by a higher frequency of application [

55]. Similar results were found by, those who discovered that water-based garlic extracts are biologically active inside cucumber seedlings and change the plant’s defense system, most likely by stimulating ROS at low concentrations [

12]. An augmentation in SOD and POD activities during the initial phases of plant development indicates a rise in oxidative stress [

70]. All extract treatments evidently function as growth enhancers at optimal doses and can serve as botanical stimulants while reducing the risk of potential health concerns, particularly

P. guajava and

A. sativum extracts.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the investigation led the researchers to the conclusion that the application of a soil spray containing four water extracts resulted in increased growth in the plants that were exposed to it. The investigation yielded a stimulatory response in the growth of the vegetables and rice, as evidenced by an increase in shoot fresh weight in 27-79% cucumber, 29-64% tomato, 33-65% kale, 37-63% lettuce, and 28-67% rice from 1 WAS to 4 WAS of application times, was observed after extract treatments. Furthermore, considerable changes were seen in the metabolites of plants, including those involved in photosynthesis and antioxidants. The enhanced photosynthesis and greater antioxidants likely contributed to the improved growth of these plant types. It is evident that all extract treatments function as growth enhancers at optimal concentrations and may act as botanical stimulants while minimizing the risk of potential health concerns, with P. guajava and A. sativum extracts being particularly effective. When cucumber, kale, and rice plants are cultivated under greenhouse conditions, the application of P. guajava and A. sativum extracts may enhance the growth conditions, resulting in a higher yield. Furthermore, the preparation is convenient and presents few or no risks to the agricultural community.

Author Contributions

Data curation, H.H.P.; Data curation-writing original draft preparation, E.E.; review and editing, Y.I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Sunchon National University. This paper is part of Ph.D. thesis by Ei Ei.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gilden, R.C.; Huffling, K.; Sattler, B. Pesticides and health risks. JOGNN. 2010, 39,103-110. [CrossRef]

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. Pesticides and human chronic diseases: Evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 268, 157-177. [CrossRef]

- Sugeng, A.J.; Beamer, P.I.; Lutz, E.A.; Rosales, C.B. Hazard ranking of agricultural pesticides for chronic health effects in Yuma Country, Arizona. Sci. Total. Environ. 2013, 463-464, 35-41.

- Aktar, M.W.; Sengupta, D.; Chowdhury, A. Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards. Interdisc. Toxicol. 2009, 2, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, F.; Ullah, S.; Hussain, F.; Ahmad, A.; Jan, A.U.; Ali, N. Nitrogen fertilizer and EDTA effect on Cannabis sativa growth an Phytoextraction of heavy metals (Cu and Zn) contaminated soil. Int. J. Agron. Agric. Res. 2014, 4, 85-90.

- Calvo, P.; Nemson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant and Soil. 2014, 383, 3-41. [CrossRef]

- Sible, C.N.; Seebauer, J.R.; Below, F.E. Plant biostimulants: A categorical review, their implications for row crop production, and relation to soil health indicators. Agronomy. 2021, 11, 1297. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, S. A convenient method for simultaneous quantification of multiple phytohormones and metabolites: application in study of rice bacterium interaction. Plant Methods. 2012, 8, 2. [CrossRef]

- Oracz, K.; Bailly, C.; Gniazdowska, A.; Côme, D.; Corbineau, F.; Bogatek, R. Induction of oxidative stress by sunflower phytotoxins in germinating mustard seeds. J. Chem. Ecol. 2007, 33, 251-264. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, M.; Merghoub, N.; El Arroussi, H. Microalgae Polysaccharides: The New Sustainable Bioactive Products for the Development of Plant Bio-Stimulants? World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 177.

- Bulgari, R.; Cocetta, G.; Trivellini, A.; Vernieri, P.; Ferrante, A. Biostimulants and Crop Responses: A Review. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2015, 31, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Ahmad, H.; Ali, M.; Hayat, K.; Khan, M.A.; Cheng, Z. Aqueous garlic and extract as a plant biostimulant enhances physiology, improves crop quality and metabolite abundance, and primes the defense responses of receiver plants. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1505.

- Balderas-Hernández, V.E.; Alvarado-Rodríguez, M.; Fraire-Velázquez, S. Conserved versatile master regulators in signaling pathways in response to stress in plants. AoB Plants. 2013, 5, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.G. Influence of Osmoregulators on Plant Tolerance to Water Stress. Environmental Science, Biology. 2016, 13(1), 42-58.

- Noctor, G.; Mhamdi, A.; Chaouch, S.; Han, Y.; Neukermans, J.; Marquez-Garcia, B.; Queval, G.; Foyer, C.H. Glutathione in plants: an integrated overview. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 454-484. [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Zeier, J. Long-distance communication and signal amplification in systemic acquired resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 30. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. The wanderings of a free radical. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 531-542. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, B.N.; Brooke, D.M. Cross talk between signaling pathways in pathogen defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 325-331.

- Levy-Booth, D.J.; Campbell, R.G.; Gulden, R.H.; Hart, M.M; Powell, J.R.; Kilronomos, J.N.; Pauls, K.P.; Swanton, C.J.; Trevors, J.T.; Dunfield, K.E. Real-time polymerase chain reaction monitoring of recombinant DNA entry into soil from decomposing roundup ready leaf biomass. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2008, 56, 6339-6347. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.; Póvoa, O.; van den Berg, C.; Figueiredo, A.C.; Moldão, M.; Monteiro, A. Genetic diversity in Mentha cervina based on morphological traits, essential oils profile and ISSRs markers. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2013, 51, 50–69. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, D.; Tasma, I.M.; Frasch, R.; Bhattacharyya, M.K. Systemic acquired resistance in soybean is regulated by two proteins, orthologous to Arabidopsis NPR1. BMC Plant Biol. 2009, 9(105). [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 990-930. [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, D. Allelopathic effects of Lantana camara L. on Lathyrus sativas L.: Oxidative imbalance and cytogenetic consequences. Allelopathy J. 2013, 31, 71-90.

- Gorinstein, S.; Leontowicz, H.; Leontowicz, M.; Namiesnik, J.; Najman, K.; Drzewiecki, J.; Cvikrová, M.; Martincová, O.; Katrich, E.; Trakhtenberg, S. Comparison of the main bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities in garlic and white and red onions after treatment protocols. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2008, 56, 4418–4426. [CrossRef]

- Grace, S.C.Phenolics as Antioxidants, Antioxidants and Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants. Blackwell Publishing. 2007.

- Jones, M.G.; Collin, H.A.; Tregova, A.; Trueman, L.; Brown, L.; Cosstick, R.; Hughes, J.; Milne, J.; Wilkinson, M.C.; Tomsett, A.B.; Thomas, B. The biochemical and physiological genesis of alliin in garlic. Med. Arom. Plant. Sci. Biotechnol. 2007, 1, 21–24.

- Li, Z.H.; Wang, Q.; Ruan, X.; Pan, C.; De Jiang, D.A. Phenolics and plant allelopathy. Molecules 2010, 15, 8933–8952.

- Cantor, A.; Hale, A.; Aaron, J.; Traw, M.B.; Kalisz, S. Low allelochemical concentrations detected in garlic mustard-invaded forest soils inhibit fungal growth and AMF spore germination. Biol. Invasions 2011, 13, 3015–3025.

- Mukerji, K. Allelochemicals: Biological Control of Plant Pathogens and Diseases. 2006.

- Liu, J.; Osbourn, A.; Ma, P. MYB transcription factors as regulators of phenylpropanoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant. 2015, 8, 689–708.

- Fan, D.; Hodges, D.M.; Zhang, J.; Kirby, C.W.; Ji, X.; Locke, S.J.; Critchley, A.T.; Prithiviraj, B. Commercial extract of the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum enhances phenolic antioxidant content of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) which protects Caenorhabditis elegans against oxidative and thermal stress. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 195–202. [CrossRef].

- Jara, P.J; Fulgencio, S.C. Antioxidant capacity of dietary polyphenolics determined by ABTS assay: A kinetic expression of the results. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 185-191.

- Huang, Z.; Wang, B.; Eaves, D.H.; Shikany, J.M.; Pace, R.D. Total phenolics and antioxidant capacity of indigenous vegetables in the southeast United States: Alabama Collaboration for Cardiovascular Equality Project. Int. J. Food Sci. 2009, 60(2), 100-108.

- Haliyan, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Panday, R.P.; Chang, C.M. Determination of antioxidants by DPPH radical scavenging activity and quantitative phytochemical analysis of Ficus religiose. Molecules 2022, 27, 1326.

- Shantabi, L.; Jagetia, G.C.; Ali, M.A.; Singh, T.T.; Devi, S.V. Antioxidant potential of Croton caudatus leaf extract in vitro. Transl. Med. Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 1–15.

- Arora, A.; Sairam, R.K.; Srivastava, G.C. Oxidative stress and oxidative system in plants. Curr. Sci. India 2002, 82, 1227–1238.

- Bartosz, G. Oxidative stress in plants. Acta Physiol. Plant. 1997, 19, 47–64.

- Das, K.; Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 1–13.

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930.

- Afzal, M.; Ali, M.; Thomson, M.; Armstrong, D. Garlic and its medicinal potential. InflammoPharmacology 2000, 8, 123–148.

- Hafez, O.M.; Saleh, M.A.; El-Lethy, S.R. Response of some seedling’s olive cultivars to foliar spray of yeast and garlic extracts with or without vascular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 24, 1119–1129.

- Hussein, N.M.; Hussein, M.I.; Gadel, H.S.H.; Hammad, M.A. Effect of two plant extracts and four aromatic oils on Tuta absoluta population and productivity of tomato cultivar gold stone. Nat. Sci. 2014, 12, 108–118.

- Lanzotti, V. The analysis of onion and garlic. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1112, 3–22.

- Rojas-Garbanzo, C.; Zimmermann, B.F.; Schulze-Kaysers, N.; Schieber, A. Characterization of phenolic and other polar compounds in peel and flesh of pink guava (Psidium guajava L. cv. ‘Criolla’) by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography with diode array and mass spectrometric detection. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 445-453.

- Ei, E.; Park, H.H.; Kuk, Y.I. Effects of plant extracts on growth promotion, antioxidant enzymes and secondary metabolites in rice (Oryza sativa) plants. Plants 2024, 13, 2727.

- Jang, S.J.; Kuk, Y.I. Growth promotion effects of plant extracts on various leafy vegetable crops. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2019, 37, 322–336. [CrossRef].

- Park, H.H. Increasement of Growth and Secondary Metabolites in Chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) Plants by Extraction and Application Methods of Agricultural By-Products. Mater’s Dissertation, Sunchon National University, Suncheon-si, Republic of Korea, 2021; p. 56. (In Korean).

- Mahmood, S.K.; Abdulla, S.M.; Hassan, K.I.; Mahmood, A.B. Effect of some processing methods on the physiochemical properties of black mulberry. Euphrates J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 16, 440–451.

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutase. 1. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [CrossRef].

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Choudhuri, M.A. Hydrogen peroxide metabolism as an index of water stress tolerance in jute. Physiol. Plant. 1985, 65, 476–489. [CrossRef].

- Zhang, J.; Cui, S.; Li, J.; Kirkham, M.B. Protoplasmic factors, antioxidant responses, and chilling resistance in maize. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1995, 33, 567–575.

- Chance, B.; Maehly, A.C. Assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Enzymol. 1995, 2, 764–775.

- Fu, J.; Huang, B. Involvement of antioxidants and lipid peroxidation in the adaptation of two cool-season grasses to localized drought stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2001, 45, 105–114.

- Chen, G.; Asada, K. Ascorbate peroxidase in tea leaves: Occurrence of two isozymes and the differences in their enzymatic and molecular properties. Plant Cell Physiol. 1989, 30, 987–998.

- Muhammad, A.; Cheng, Z.; Sikandar, H.; Husain, A.; Muhammad, I.G.; Liu, T. Foliar spraying of aqueous garlic bulb extract stimulates growth and antioxidant enzyme activity in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1001–1013.

- Bhandari, S.R.; Yoon, M.K.; Kwak, J.H. Contents of phytochemical constituents and antioxidant activity of 19 garlic (Allium sativum L.) parental lines and cultivars. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 55, 138–147. [CrossRef].

- El-Hamied, S.A.A.; El-Amary, E.I. Improving growth and productivity of “pear” trees using some natural plant extracts under North Sinai conditions. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2015, 8, 01–09.

- Nautiyal, P.; Lal, S.; Singh, C.P. Effect of shoot pruning severity and plant spacing on leaf nutrient status and yield of guava cv. Pant Prabhat. Int. J. Basic Appl. Agric. Res. 2016, 14, 288–294.

- Zhou, Y.L.; Cheng, Z.H.; Meng, H.W.; Gao, H.C. Allelopathy of garlic root aqueous extracts and root exudates. J. Northwest A&F Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2007, 35, 87–92. (In Chinese).

- El-Hamied, S.A.A.; El-Amary, E.I. Improving growth and productivity of “pear” trees using some natural plant extracts under North Sinai conditions. IOSR-JAVS. 2015, 8, 01-09.

- Chai, L.Y.; Mubarak, H.; Yong, W.; Tang, C.J.; Mirza, N. Growth, photosynthesis, and defense mechanism of antimony (Sb)-contaminated Boehmeria nivea L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 7470-7481.

- Khan, M.; Daud, M.K.; Basharat, A.; Khan, M.J; Ullah, A.; Muhammad, N.; Rehman, Z.; Zhu, S. Alleviation of lead-induced physiological, metabolic, and ultra-morphological changes in leaves of upland cotton through glutathione. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2106, 23, 8431-8440.

- Siddique, M.A.B.; Ismail, B.S. Allelopathic effects of Fimbristylis miliacea on the physiological activities of five Malaysian rice varieties. Aust. J. Crop. Sci. 2013, 7, 2062-2067.

- Yuyan, A.; Qi, L.; Wang, M. ALA pretreatment improves the waterlogging tolerance of fig plants. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147202.

- Baliyan, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Chang, C.M. Determination of antioxidants by DPPH radical scavenging activity and quantitative phytochemical analysis of Ficus religiose. J. Mol. 2022, 27, 1326. [CrossRef].

- Akullo, J.O.; Kiage-Mokua, B.N.; Nakimbugwe, D.; Ng’ang’a, J.; Kinyuru, J. Phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity of various solvent extracts of two varieties of ginger and garlic. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18806.

- Kuiters, A.T. Effects of phenolic acids on germination and early growth of herbaceous woodland plants. J. Chem. Ecol. 1989, 15(2), 468-478.

- Janf, S.J.; Park, H.H.; Kuk, Y.I. Application of various extracts enhances the growth and yield of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) without compromising the biochemical content. J. Agron. 2021, 11, 505.

- Aryal, S.; Baniya, M.K.; Danekhu, K.; Kunwar, P.; Gurung, R.; Koirala, N. Total phenolic content, flavonoid content, and antioxidant potential of wild vegetables from Western Nepal. J. Plants 2019, 8, 96.

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Shen, D.; Oiu, Y.; Song, J. Diversity evaluation of morphological traits and allicin content in garlic (Allium sativum L.) from China. Euphytica 2014, 198, 243-254.

Figure 1.

Effect of four water extracts on the shoot fresh weight of rice, and vegetables sprayed on different sowing times. (a) 0.1%; (b) 0.5% concentrations. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in Tukey’s HSD at α = 0.05. WAS, week after sowing.

Figure 1.

Effect of four water extracts on the shoot fresh weight of rice, and vegetables sprayed on different sowing times. (a) 0.1%; (b) 0.5% concentrations. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in Tukey’s HSD at α = 0.05. WAS, week after sowing.

Figure 2.

Effect of four water extracts on the quantum yield of rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 WAS. CK, control; T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava extract; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. vera extract; T5 and T6, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extract; T7 and T8, 0.1 and 0.5% of M. sativa extract. The parameter was recorded at 7 and 14 DAT. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in Tukey’s HSD at α = 0.05.

Figure 2.

Effect of four water extracts on the quantum yield of rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 WAS. CK, control; T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava extract; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. vera extract; T5 and T6, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extract; T7 and T8, 0.1 and 0.5% of M. sativa extract. The parameter was recorded at 7 and 14 DAT. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in Tukey’s HSD at α = 0.05.

Figure 3.

Effect of four water extracts on total chlorophyll and carotenoid contents in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 3.

Effect of four water extracts on total chlorophyll and carotenoid contents in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 5.

Effect of four water extracts on DPPH radical scavenging activity and total phenol contents in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 5.

Effect of four water extracts on DPPH radical scavenging activity and total phenol contents in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 6.

Effect of four water extracts on total flavonoid contents and SOD activity in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 6.

Effect of four water extracts on total flavonoid contents and SOD activity in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 7.

Effect of four water extracts on CAT and APOD activity in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 7.

Effect of four water extracts on CAT and APOD activity in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 8.

Effect of four water extracts on GPOD activity in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

Figure 8.

Effect of four water extracts on GPOD activity in rice, cucumber and kale sprayed on (a) 2 weeks after sowing (WAS); (b) 3 weeks after sowing under greenhouse conditions. T1 and T2, 0.1 and 0.5% of P. guajava; T3 and T4, 0.1 and 0.5% of A. sativum extracts. Means within bars followed by the same letters did not differ significantly in the LSD test at α = 0.05.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).