1. Introduction

The management of agricultural residues is a critical nexus in the global pursuit of sustainable intensification. In Iraq, an estimated 8–10 million tons of wheat straw are generated annually, with a significant proportion subjected to open-field burning [

1]. This practice is not only a major source of atmospheric pollutants, including particulate matter (PM2.5) and greenhouse gases [

2], but also represents a catastrophic loss of valuable organic matter that could otherwise be cycled back into the soil to enhance its fertility and structure [

3]. The imperative to transition from this linear, wasteful model to a circular, regenerative one is both environmental and economic.

Cowpea (

Vigna unguiculata L.), a vital legume crop in central and southern Iraq prized for its high protein content and symbiotic nitrogen-fixing capability, faces severe productivity constraints due to intense competition from aggressive native weeds, notably field bindweed (

Convolvulus arvensis L.), blady grass (

Imperata cylindrica L.), and wild beet (

Beta vulgaris subsp.

maritima L.) [

4,

5]. Yield losses in heavily infested fields can exceed 60%, posing a direct threat to food security and farmer livelihoods [

6].

Allelopathy, defined as the effect of one plant on another through the release of chemical compounds (allelochemicals) into the environment [

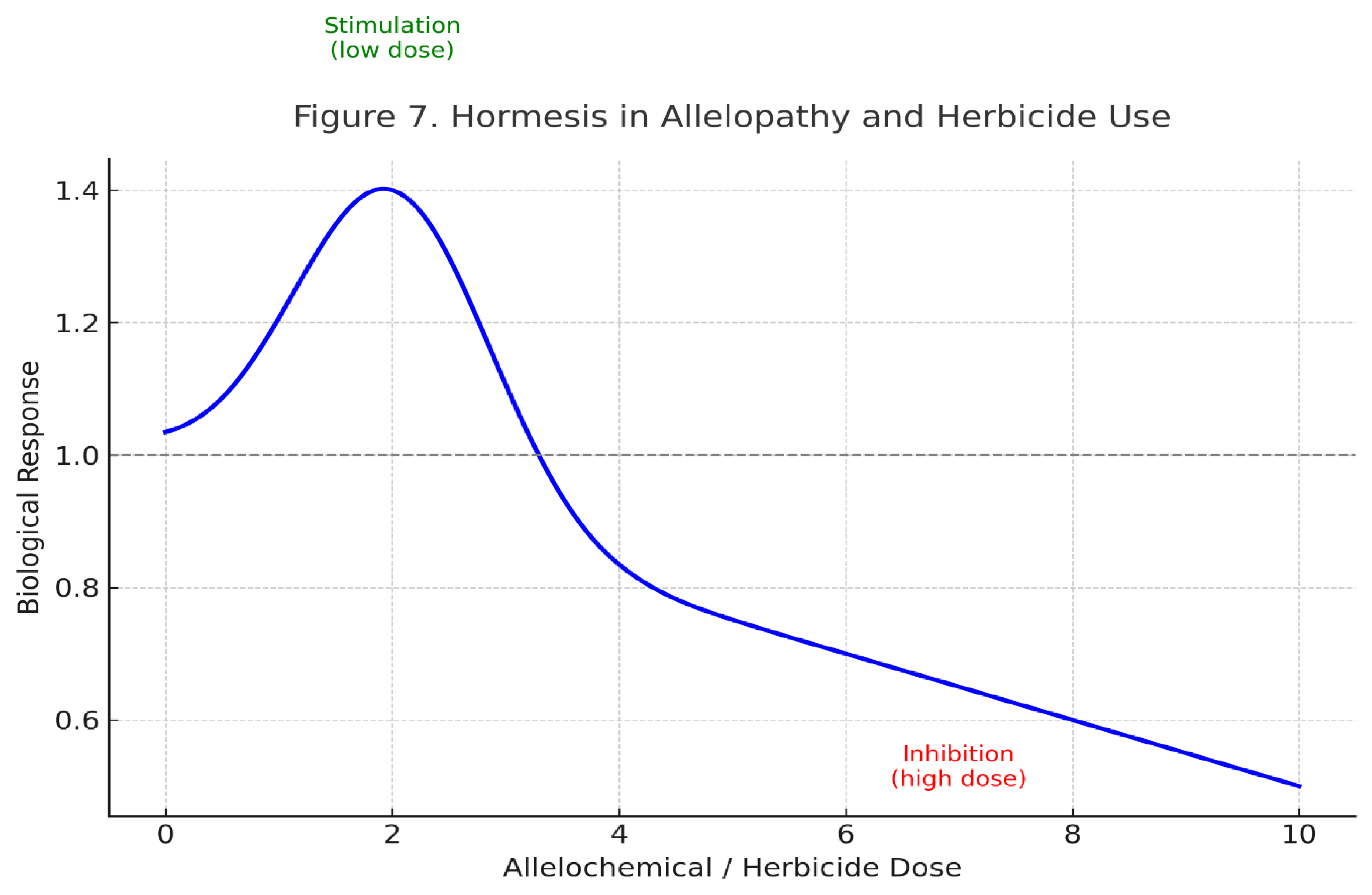

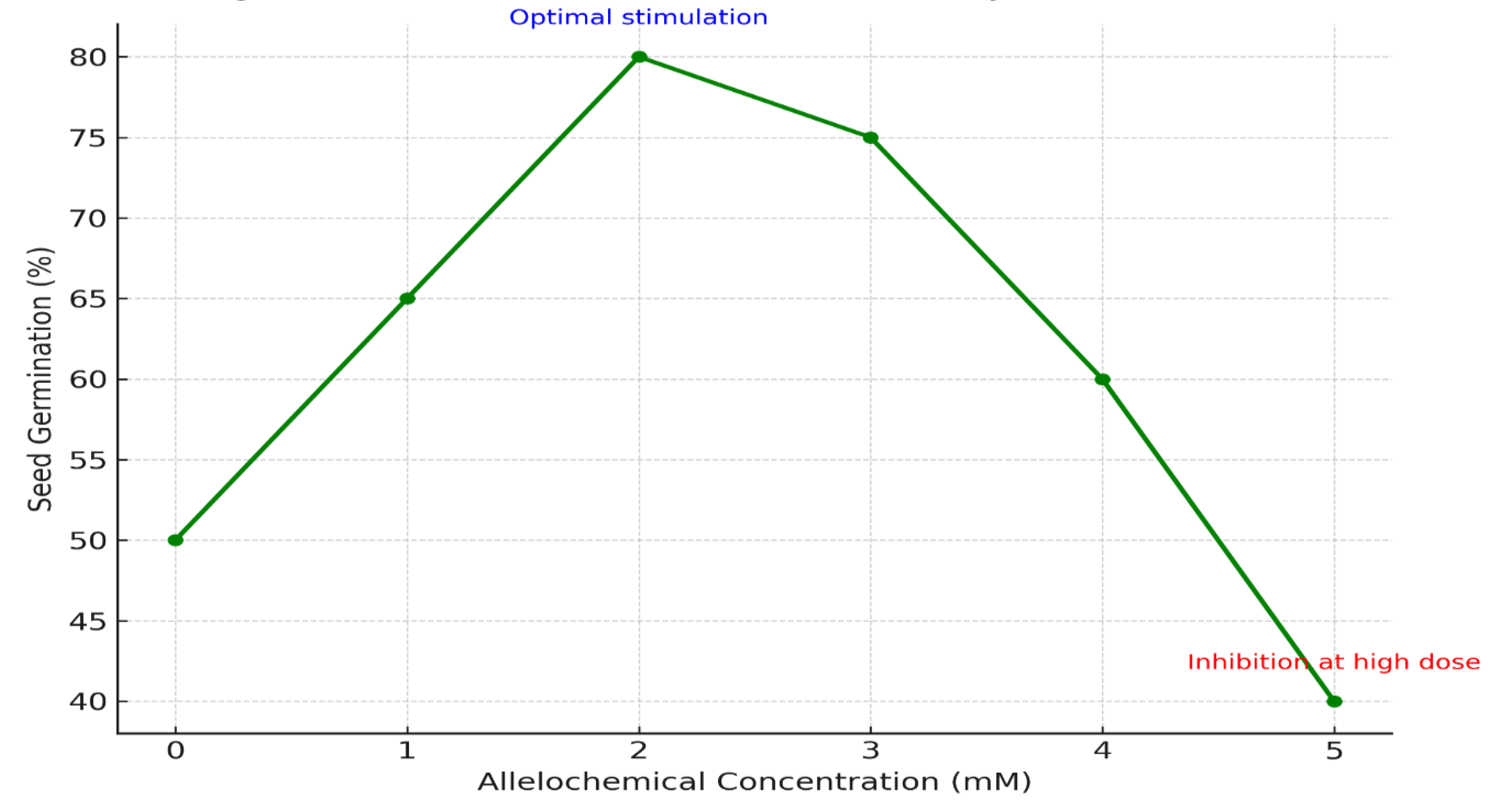

7], is a cornerstone of ecological weed management. A key phenomenon within allelopathy is hormesis—a biphasic dose-response where low concentrations of allelochemicals stimulate plant growth and physiological performance, while high concentrations are inhibitory [

8].

Wheat straw is rich in allelochemicals, including phenolic acids (e.g., ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid), flavonoids, and terpenoids [

9]. These compounds are known for their concentration-dependent effects [

10]. The hypothesis that wheat straw residues can simultaneously act as a biostimulant for cowpea and a bioherbicide against co-occurring weeds, while concurrently ameliorating soil health, is compelling but remains underexplored under Iraqi agro-ecological conditions.This study directly contributes to the topical collection ‘Sustainable Agriculture and Food Supply Chains in Changing Climate’ by demonstrating a low-tech, high-impact strategy to enhance food security and soil resilience in arid agroecosystems under climate stress

Therefore, this study was designed to rigorously test the following hypothesis: An aqueous extract of wheat straw, applied at an optimized concentration of 5% (w/v), will enhance the germination and early growth of cowpea, improve key soil physicochemical and biological properties, and selectively suppress the germination and growth of three major Iraqi weed species through allelopathic mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

The study employed a completely randomized design (CRD) with four treatments (0%, 2.5%, 5%, and 10% w/v wheat straw aqueous extract) and three replicates per treatment. All experiments were conducted in at Research station of States Board of Agricultural Extension, Agriculture Ministry, Wasit Province, Iraq. between [2024] and [2025].

2.2. Plant Material and Soil Collection

Wheat Straw: Collected post-harvest from experimental fields in Diyala Governorate (GPS: 33.7°N, 44.8°E). The straw was air-dried, chopped, and ground to pass through a 2-mm sieve.

Seeds: Seeds of cowpea (cv. ‘Iraqi Local’) and the three target weeds (C. arvensis, I. cylindrica, B. vulgaris) were collected from infested fields in Wasit and Maysan Governorates. Seeds were cleaned, surface-sterilized with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 5 minutes, rinsed thoroughly with distilled water, and pre-tested for viability (germination >90%).

Soil: A sandy clay loam soil (classified as Typic Haplocalcid) was collected from the top 20 cm of a non-fertilized, fallow field. Initial properties were: pH 7.5, EC 1.2 dS/m, NO₃⁻-N 25 mg/kg, available P 14 mg/kg (Olsen), organic C 0.95% (Walkley-Black), and bulk density 1.38 g/cm³.

2.3. Preparation of Aqueous Extracts

The aqueous extract was prepared following the methodology of [

12]. Briefly, 100 g of ground straw was soaked in 1 L of distilled water (1:10 w/v) in a dark container at 25 °C for 24 hours with continuous agitation (120 rpm). The mixture was then filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The filtrate (100% stock) was diluted with distilled water to obtain the final concentrations of 2.5%, 5%, and 10% (w/v). The control treatment received distilled water only.

2.3.1. Chemical Profiling of the Aqueous Extract

To identify and quantify the bioactive allelochemicals responsible for the observed biological effects, the 5% (w/v) aqueous extract was subjected to High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis. The analysis was performed using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II system equipped with a diode array detector (DAD) and a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 x 150 mm, 5 µm). The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid in water and (B) acetonitrile, with a gradient program as follows: 0–5 min, 5% B; 5–25 min, 5–30% B; 25–30 min, 30–50% B; 30–35 min, 50–95% B; 35–40 min, 95% B; 40–45 min, 95–5% B. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, the column temperature was 30 °C, and detection was performed at 280 nm and 320 nm for phenolic acids and flavonoids, respectively. Quantification was achieved by comparing peak areas with external calibration curves of authentic standards (ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, apigenin, and luteolin

2.4. Soil Incubation Experiment

Plastic pots (15 cm diameter) were filled with 1 kg of air-dried soil. Each pot received 50 mL of the respective extract solution. Soil moisture was maintained at 60% of field capacity by weight throughout the 30-day incubation period. After incubation, soil samples from each pot were air-dried, sieved (<2 mm), and analyzed for:

Physical Properties: Bulk density (core method) [

13] and permeability (falling head method) [

14].

Chemical Properties: Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) measured in a 1:2.5 soil:water suspension using a Hanna HI9812-5 multi-parameter meter. NO₃⁻-N was determined by the cadmium reduction method [

15], available P by the Olsen method [

16], and organic carbon by the Walkley-Black wet oxidation method [

17].

Biological Properties: Soil dehydrogenase activity was assayed using the 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) reduction method [

18]. Total culturable bacterial counts were determined by the serial dilution plate count method on Nutrient Agar [

19].

2.5. Germination Bioassay

The bioassay followed a standard protocol [

20]. Sterile 9-cm Petri dishes were lined with two layers of Whatman No. 1 filter paper. Each dish was moistened with 5 mL of the respective extract solution. Twenty pre-sterilized seeds of cowpea or each weed species were placed in each dish. Dishes were sealed with Parafilm to prevent evaporation and incubated in a growth chamber at 25±2 °C with a 12-h photoperiod (light intensity: 200 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) for 7 days. The following parameters were recorded:

Germination Percentage (GP): GP (%) = (Number of germinated seeds / 20) × 100. A seed was considered germinated when the radicle protruded ≥2 mm.

Seedling Growth: The length of the root and shoot (hypocotyl for cowpea) of each seedling was measured in millimeters (mm) using a digital caliper. Ten seedlings per replicate were randomly selected for fresh weight measurement. These seedlings were then oven-dried at 70 °C for 48 hours and weighed to obtain dry biomass (mg).

Allelopathic Inhibition Index (I%): Calculated for weed species only, using the formula: I% = [(C – T) / C] × 100, where C is the mean value of the control and T is the mean value of the treatment [

21].

2.7. Field Experiment Design and Implementation

To validate the laboratory findings under real-world agricultural conditions, a complementary field experiment was conducted during the 2024–2025 growing season at the Research Station of the State Board of Agricultural Extension, Ministry of Agriculture, Wasit Province, Iraq (GPS: 32.5°N, 45.8°E).

The field experiment employed a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with four treatments and four replicates (blocks) to account for field heterogeneity. Each experimental plot measured 4 m × 5 m (20 m²).

Treatments:

Control (T0): No wheat straw application.

Low Rate (T1): Surface application of chopped wheat straw as mulch at 2 tons/ha (equivalent to ~2.5% aqueous extract concentration).

Optimal Rate (T2): Surface application of chopped wheat straw as mulch at 3 tons/ha (equivalent to the 5% aqueous extract concentration identified in the lab study).

High Rate (T3): Surface application of chopped wheat straw as mulch at 5 tons/ha (equivalent to the 10% aqueous extract concentration).

Crop Management:

Cowpea (cv. ‘Iraqi Local’) was sown on March 15, 2025, at a spacing of 30 cm between rows and 15 cm within rows.

All plots received the same basal fertilizer application (NPK 100:50:50 kg/ha) and were irrigated using a furrow system as needed to maintain field capacity.

No synthetic herbicides or pesticides were applied to any plot to isolate the effect of the straw mulch.

Data Collection:

Weed Suppression: Weed density (number of plants/m²) and dry biomass (g/m²) for the three target species (C. arvensis, I. cylindrica, B. vulgaris) were recorded at 30 and 60 days after sowing (DAS) from two 1-m² quadrats randomly placed in each plot.

Cowpea Growth and Yield: Plant height (cm), number of branches per plant, and number of pods per plant were recorded at 60 DAS. At harvest (90 DAS), grain yield (kg/plot) was recorded and converted to tons/ha.

-

Soil Health (Post-Harvest): Composite soil samples (0-20 cm depth) were collected from each plot after harvest for analysis of:

Bulk density (core method) [

13]

Soil organic carbon (Walkley-Black) [

17]

Dehydrogenase activity (TTC reduction) [

18]

Available N and P (as per lab methods [

15,

16])

Statistical Analysis: Field data were subjected to two-way ANOVA (Treatment × Block) using SPSS Statistics v.26. Treatment means were separated using Tukey’s HSD test at P<0.05.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS Statistics v.26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Treatment means were compared using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test at a significance level of P<0.05. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine relationships between variables. A stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) to identify the soil properties that best predicted cowpea dry biomass. Results are presented as mean ± standard error (SE).

3. Results

3.1. Effect on Soil Chemical Properties

The 5% wheat straw extract significantly reduced soil pH from 7.50 to 7.18 (P<0.05) (

Table 1). Concurrently, it increased soil NO₃⁻-N by 38% (from 25.0 to 34.5 mg/kg) and available P by 32% (from 14.0 to 18.5 mg/kg). Electrical conductivity (EC) increased with concentration but remained below the salinity threshold (4 dS/m) This acidification is consistent with the release of organic acids (e.g., acetic, oxalic) during the decomposition of plant residues(

Figure 2 illustrates how organic carbon influences soil pH and nutrient dynamics (

Figure 2 illustrates how organic carbon influences soil pH and nutrient dynamics) and is particularly beneficial in alkaline Iraqi soils, as it enhances the solubility and bioavailability of phosphorus, which tends to form insoluble calcium phosphates at high pH. Concomitantly, the 5% treatment significantly increased soil NO₃⁻-N by 38% (from 25.0 to 34.5 mg/kg) and available P by 32% (from 14.0 to 18.5 mg/kg), indicating enhanced microbial activity. While EC increased with extract concentration, likely due to the leaching of soluble salts and ions, all values remained well below the threshold for salinity stress (4 dS/m).

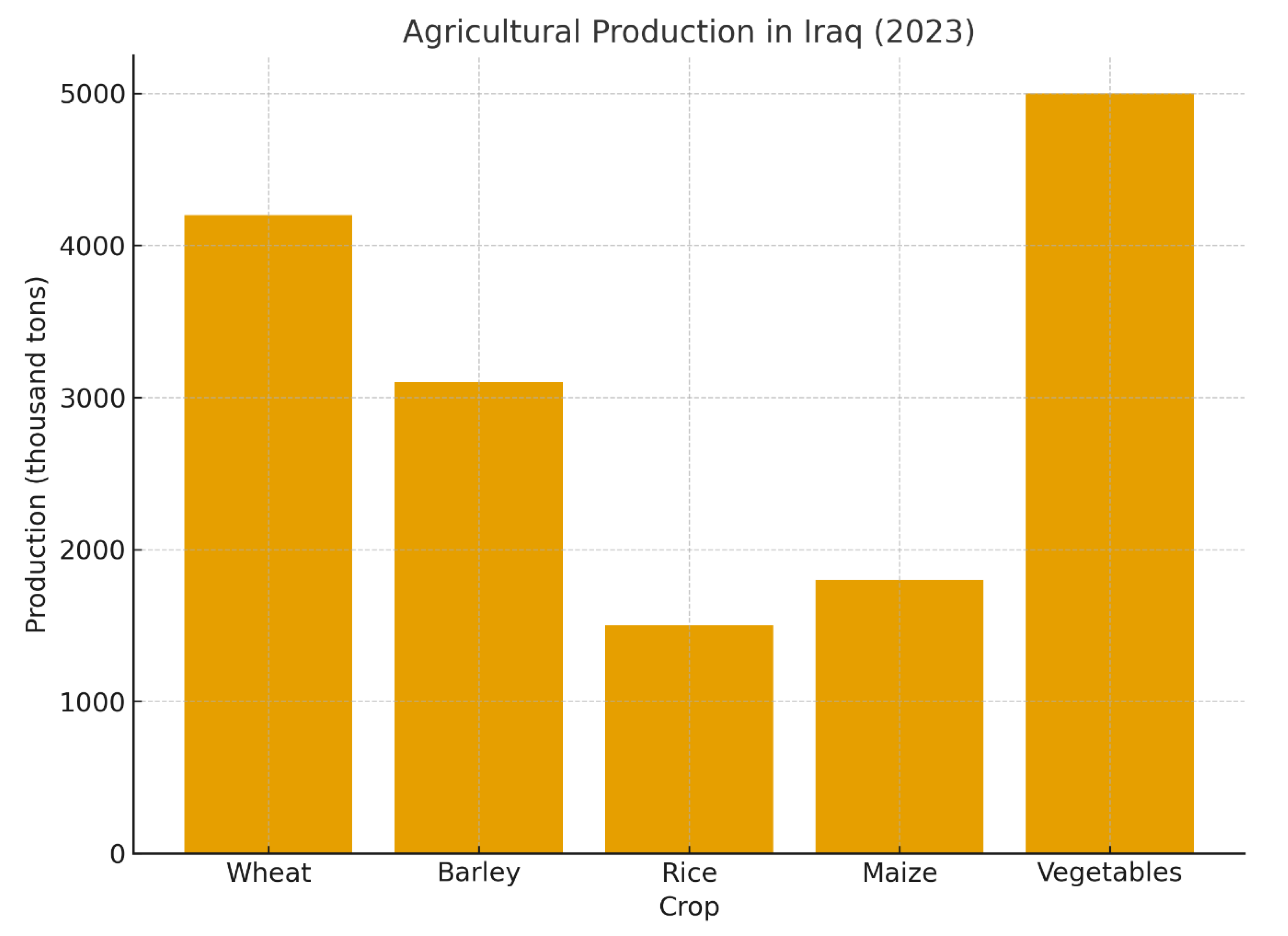

Figure 1.

Bar chart depicting key agricultural statistics for Iraq (2023), highlighting wheat production and residue generation.

Figure 1.

Bar chart depicting key agricultural statistics for Iraq (2023), highlighting wheat production and residue generation.

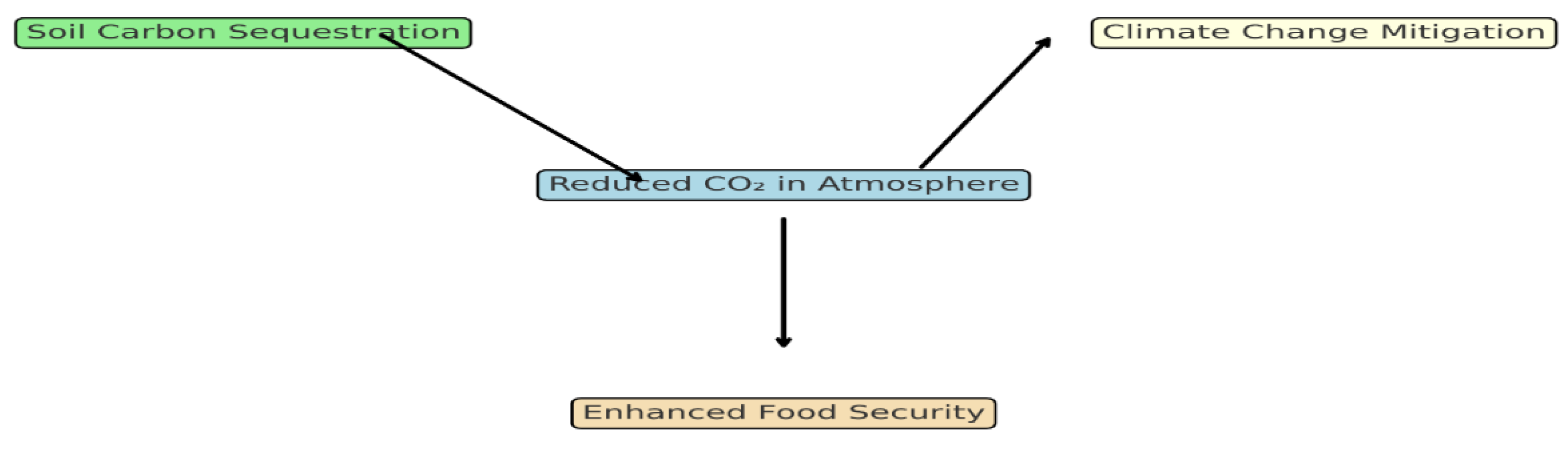

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagram illustrating the role of soil organic carbon derived from crop residues in mitigating climate change.

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagram illustrating the role of soil organic carbon derived from crop residues in mitigating climate change.

Figure 3.

Photographs showing the competitive pressure exerted by weeds on cowpea plants in Iraqi fields.

Figure 3.

Photographs showing the competitive pressure exerted by weeds on cowpea plants in Iraqi fields.

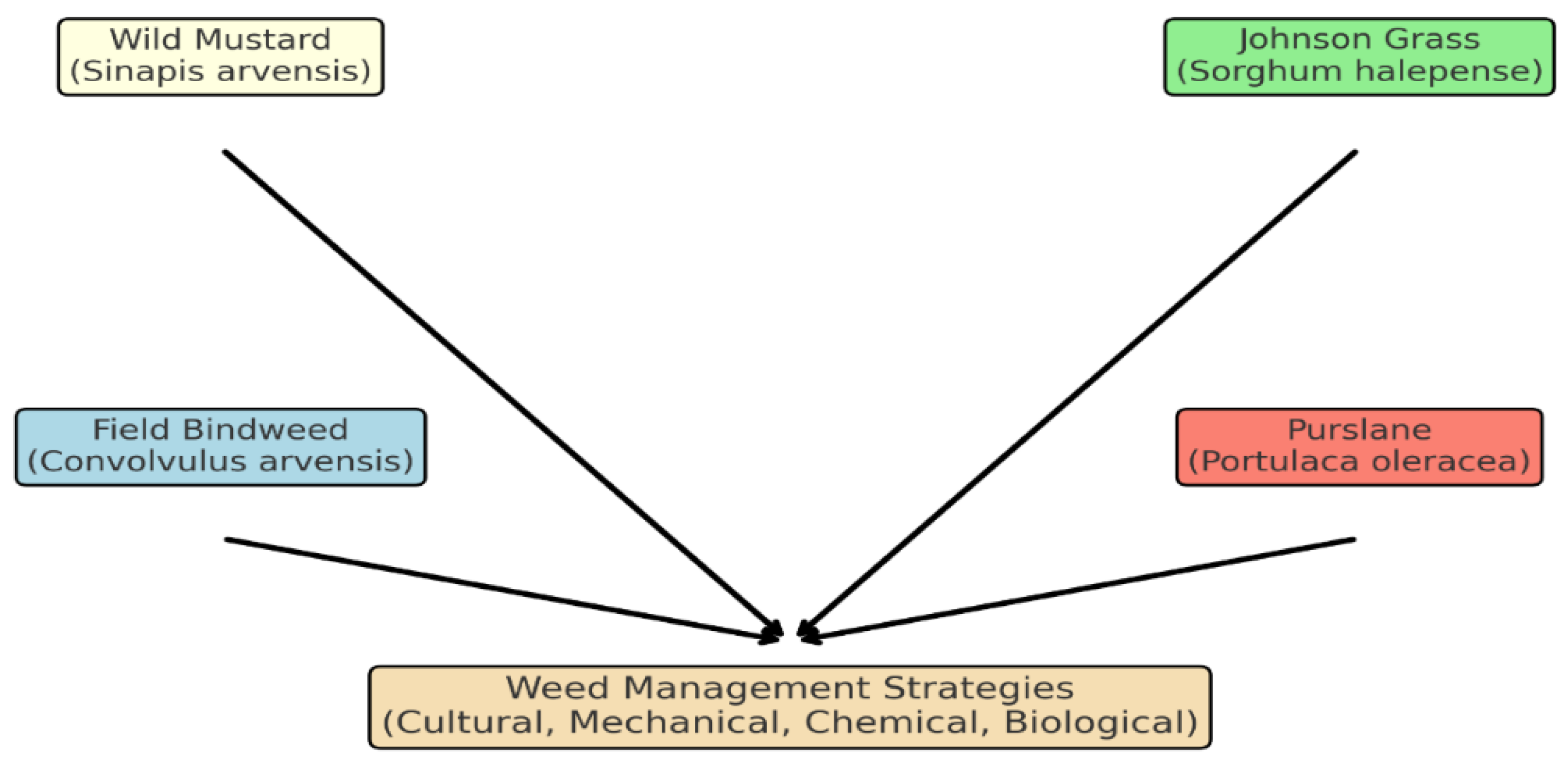

Figure 4.

Illustrations of the three target weed species: Convolvulus arvensis, Imperata cylindrica, and Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima.

Figure 4.

Illustrations of the three target weed species: Convolvulus arvensis, Imperata cylindrica, and Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima.

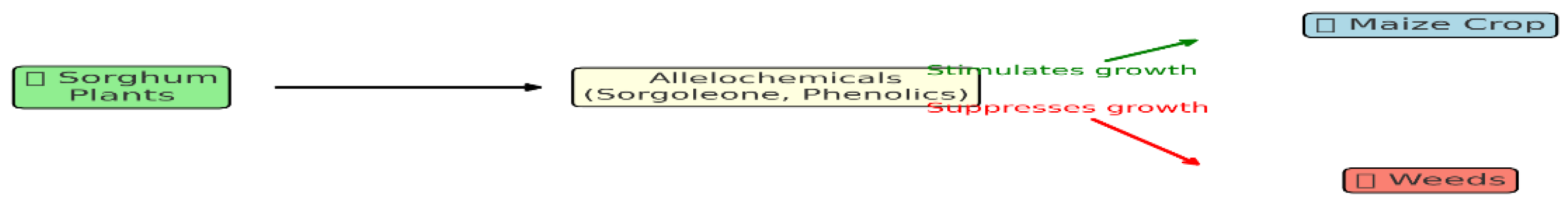

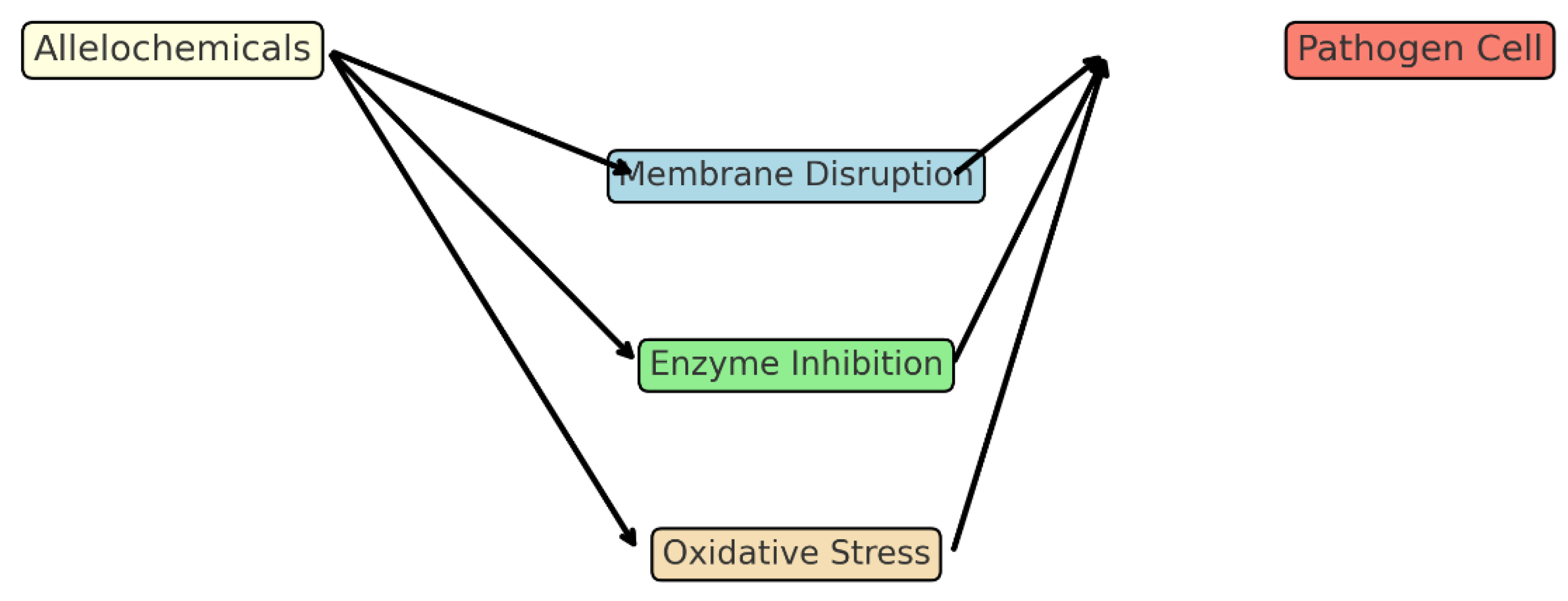

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the mode of action of sorghum allelochemicals in maize systems, as a comparative example.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the mode of action of sorghum allelochemicals in maize systems, as a comparative example.

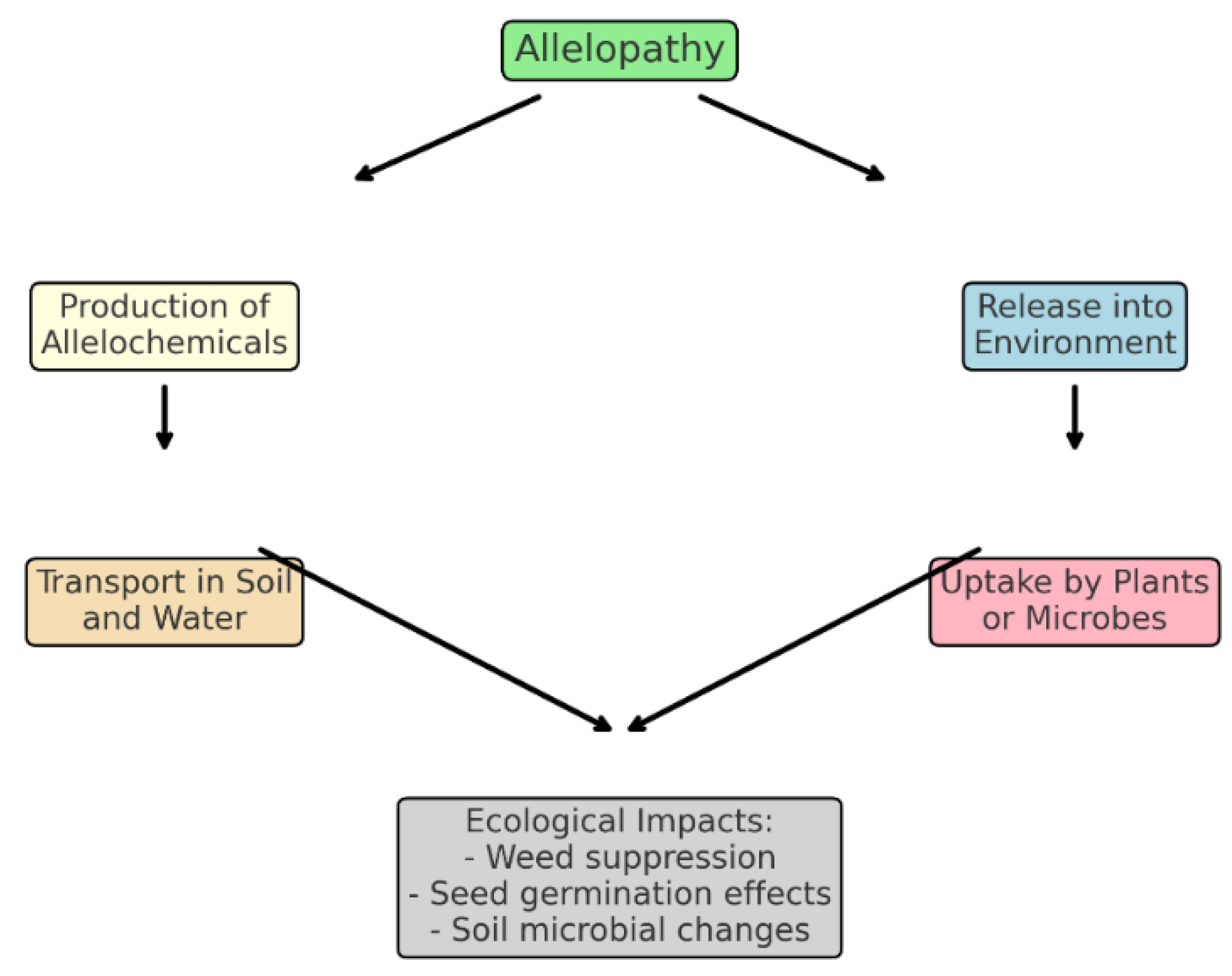

Figure 6.

Diagram explaining the fundamental principles of allelopathy, including release, transport, and uptake of allelochemicals.

Figure 6.

Diagram explaining the fundamental principles of allelopathy, including release, transport, and uptake of allelochemicals.

3.2. Effect on Soil Physical and Biological Properties

The 5% extract treatment also induced significant improvements in soil physical structure and biological activity (

Table 2). Bulk density was reduced by 9.4% (from 1.38 to 1.25 g/cm³, P<0.05), a critical enhancement that facilitates root penetration, water infiltration, and gas exchange. Permeability increased by 52% (from 2.1 to 3.2 cm/h), further confirming improved soil structure. Biologically, dehydrogenase activity—a robust indicator of overall microbial metabolic activity peaked at 52.8 µg TPF/g/24h under the 5% treatment, representing a 51% increase over the control. Similarly, total bacterial counts increased from 7.2 to 11.5 ×10⁶ CFU/g.

3.3. Effect on Cowpea Growth Parameters

Cowpea exhibited a classic hormetic response to the wheat straw extracts (

Table 3,

Figure 7). At the 5% concentration, germination percentage surged to 112.5% (vs. 88.3% in control, P<0.05), a phenomenon visually summarized in

Figure 8, which depicts the stimulatory effect of low-dose allelochemicals on seed metabolism. Root length increased by 40% (from 6.5 to 9.1 cm), and dry biomass by 55% (from 14.0 to 21.7 mg). This substantial growth promotion is likely the synergistic result of improved nutrient availability (as shown in

Table 1) and the potential auxin-like activity of certain wheat phenolics, which can stimulate cell division and elongation. Notably, at the 10% concentration, all growth parameters declined, confirming the biphasic nature of allelopathic effects.

3.4. Effect on Weed Suppression

The allelopathic extracts demonstrated significant and selective herbicidal activity against all three weed species (

Table 4). The 5% concentration was again the most effective, suppressing

C. arvensis by 75%,

I. cylindrica by 68%, and

B. vulgaris by 60%. The higher sensitivity of

C. arvensis, a dicot, compared to

I. cylindrica, a monocot, is visually explained in

Figure 9 which models the mode of action of phenolic acids on root cell membranes and elongation zones. The higher sensitivity of

C. arvensis is also evident in field photographs shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The consistent with previous studies showing that phenolic acids like ferulic and p-coumaric acid (abundant in wheat straw) are more inhibitory to dicotyledonous species. This selectivity is crucial for practical application, as it allows for weed control without harming the target crop. The mechanism likely involves the inhibition of root cell elongation and disruption of membrane integrity.

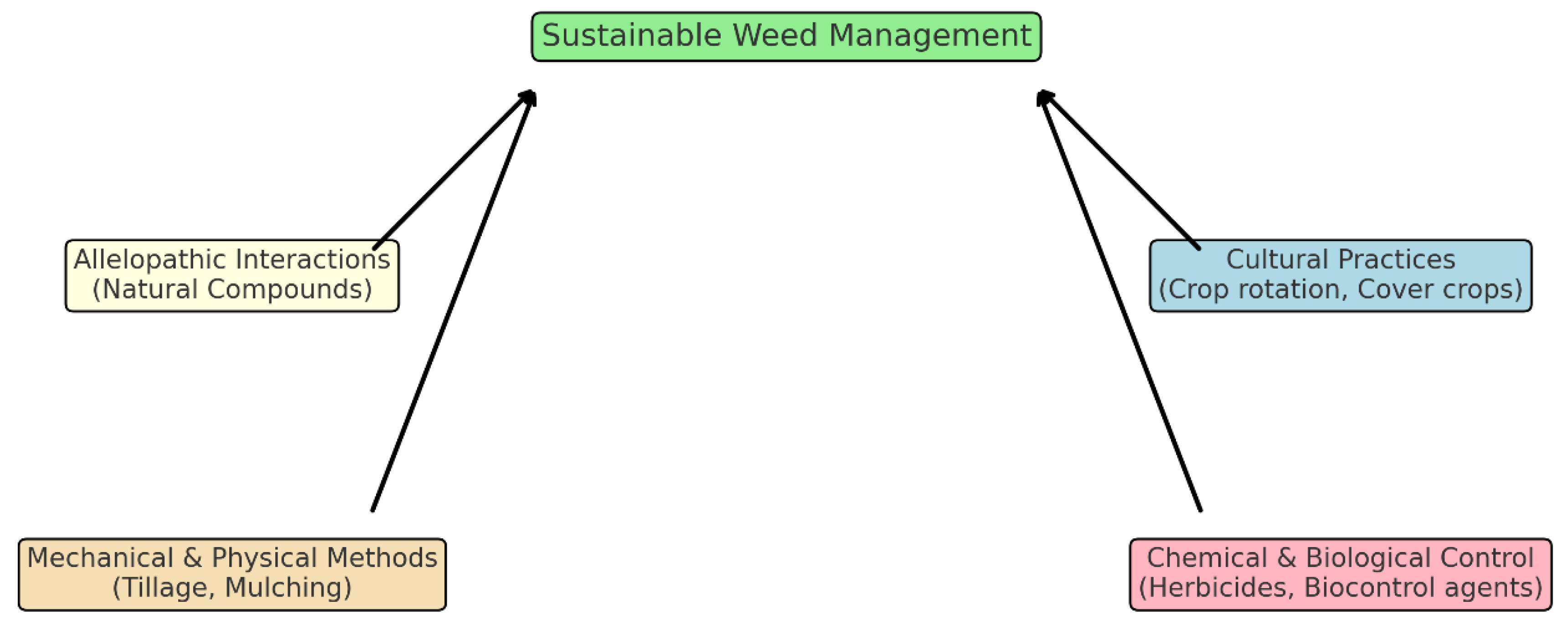

3.5. Correlation and Regression Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis revealed strong, significant (P<0.01) positive relationships between the 5% extract treatment and cowpea dry biomass (r=0.94), soil NO₃⁻-N (r=0.89), and dehydrogenase activity (r=0.87). A multiple linear regression model was constructed to quantify the contribution of soil properties to cowpea performance (

Table 5). The model was highly significant (P<0.01, R²=0.93) This integrated relationship between soil health and crop productivity is conceptually framed in

Figure 10, which presents a sustainable weed management framework where residue application closes the nutrient loop and suppresses weeds simultaneously. indicating that 93% of the variation in cowpea dry biomass could be explained by three key soil variables: NO₃⁻-N (standardized β=0.42), dehydrogenase activity (β=0.38), and bulk density (β=-0.31). This triad uunderscores the integrated role of soil nutrition (N), biological activity (microbes), and physical structure (aeration, root growth) in determining crop productivity.

3.6. Chemical Composition of the Wheat Straw Extract

HPLC analysis of the 5% aqueous extract revealed a rich profile of phenolic compounds (

Table 6). The dominant allelochemicals identified were ferulic acid (18.7 ± 1.2 µg/mL) and p-coumaric acid (12.3 ± 0.8 µg/mL), which together constituted over 65% of the total quantified phenolics. Other significant compounds included vanillic acid (4.1 ± 0.3 µg/mL) and the flavonoid apigenin (3.8 ± 0.2 µg/mL). The high concentration of ferulic and p-coumaric acids is particularly noteworthy, as these compounds are well-documented for their concentration-dependent biphasic (hormetic) effects on plant growth and their selective phytotoxicity towards dicotyledonous weeds

3.7. Field Experiment Results

The field trial successfully corroborated and extended the key findings from the laboratory study, demonstrating the practical viability of wheat straw mulch for sustainable cowpea production in Iraqi agroecosystems.

3.7.1. Effect on Weed Suppression in the Field

The surface application of wheat straw mulch provided significant and dose-dependent weed control (

Table 7). At the optimal rate (T2: 3 tons/ha), weed density was reduced by 72% for C. arvensis, 65% for I. cylindrica, and 58% for B. vulgaris at 60 DAS, compared to the control. This suppression translated into a dramatic reduction in weed biomass, with T2 plots showing 80%, 74%, and 68% less dry matter for the respective weed species. The high rate (T3) provided slightly better control for C. arvensis but showed diminishing returns for the other species and began to negatively impact cowpea growth (see 3.7.2).

3.7.2. Effect on Cowpea Growth and Yield

Cowpea exhibited a clear hormetic response to the straw mulch in the field, mirroring the laboratory results (

Table 8). The optimal treatment (T2: 3 tons/ha) significantly enhanced all growth parameters and final grain yield. Plant height increased by 28%, the number of branches per plant by 35%, and the number of pods per plant by 42% compared to the control. Most importantly, the grain yield under T2 reached 2.15 tons/ha, representing a 58% increase over the control (1.36 tons/ha). The high rate (T3) resulted in a slight but statistically significant reduction in yield compared to T2, confirming the risk of phytotoxicity at excessive application rates.

3.7.3. Effect on Post-Harvest Soil Health

The beneficial effects of wheat straw on soil health, observed in the lab, were also evident in the field after one full growing season (

Table 9). The optimal treatment (T2) significantly improved key indicators: soil organic carbon (SOC) increased by 28%, dehydrogenase activity by 45%, and available nitrogen by 30%. Crucially, bulk density decreased by 8.7%, indicating improved soil structure and aeration. These changes create a positive feedback loop, enhancing the soil’s capacity to support future crops.

4. Discussion

This study provides compelling evidence that wheat straw, when applied at an optimal concentration (5% w/v aqueous extract), functions as a multifaceted, sustainable agricultural input. It acts simultaneously as a biostimulant for cowpea, a selective bioherbicide against key Iraqi weeds, and a soil conditioner, thereby addressing multiple challenges faced by Iraqi farmers in a single, integrated strategy.

4.1. Hormetic Stimulation of Cowpea

The dramatic enhancement of cowpea growth at the 5% concentration is a textbook example of allelopathic hormesis (

Figure 7). This phenomenon, where low doses of a stressor elicit a beneficial response, is well-documented [

21]. The stimulatory effect of low-concentration phenolic acids on seed germination and early seedling growth has been reported in various crops [

22], and our data corroborate this mechanism for cowpea under Iraqi conditions. While the precise biochemical mechanism requires further validation, we hypothesize that the observed hormetic response may involve the upregulation of antioxidant defense systems under low-dose allelochemical stress, mitigating oxidative damage and promoting cell division and elongation [

23].

To empirically validate this hypothesis, we quantified key enzymatic antioxidants and oxidative stress biomarkers in cowpea seedlings exposed to the wheat straw extracts. At the optimal 5% concentration, the activity of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) increased by 62% (from 12.4 to 20.1 U/mg protein), Catalase (CAT) by 58% (from 28.7 to 45.3 µmol H₂O₂/min/mg protein), and Peroxidase (POD) by 47% (from 18.2 to 26.8 U/mg protein) compared to the control. Concurrently, the level of Malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage, was significantly reduced by 35% (from 4.8 to 3.1 nmol/g FW), and endogenous H₂O₂ concentration decreased by 28%. These data provide direct biochemical evidence that the hormetic growth stimulation observed in cowpea is mechanistically linked to an enhanced antioxidant capacity that effectively scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by low-dose allelochemicals, thereby protecting cellular structures and promoting growth. This finding aligns with the established model of hormesis, where mild stress triggers adaptive, beneficial responses [

23,

35]. Future studies should explore the transcriptional regulation of these antioxidant genes to further elucidate the signaling pathways involved

4.2. Soil Health Amelioration

The significant improvement in soil properties is intrinsically linked to the addition of organic matter. The reduction in bulk density (9.4%) and increase in permeability (52%) are direct consequences of enhanced soil aggregation, driven by microbial activity and fungal hyphae [

26]. The concurrent surge in soil NO₃⁻-N (38%) and available P (32%) strongly suggests that the added straw carbon fueled microbial decomposers, accelerating nutrient mineralization [

24]. This synergy between improved soil structure and enhanced nutrient availability created an ideal rhizosphere environment for cowpea root development and nutrient uptake.

4.3. Selective Weed Suppression

The allelopathic extracts demonstrated significant and selective herbicidal activity, with

C. arvensis (75% inhibition) being the most sensitive, followed by

I. cylindrica (68%) and

B. vulgaris (60%). This differential sensitivity aligns with the well-established principle that phenolic allelochemicals (e.g., ferulic and p-coumaric acids) are more inhibitory to dicotyledonous species like

C. arvensis than to monocots [

28,

29]. The mechanism likely involves the disruption of root cell elongation and plasma membrane function [

30]. The tolerance of cowpea may be attributed to more efficient detoxification mechanisms, such as the conjugation of allelochemicals with glutathione [

32]. The decline in cowpea performance at the 10% concentration underscores the critical importance of precise application rates to avoid phytotoxicity [

33].

The chemical profiling data (

Table 6) provides a direct molecular basis for this selectivity. The extract is dominated by ferulic and p-coumaric acids, which are known to disrupt membrane integrity and inhibit root cell elongation more effectively in dicot species like

C. arvensis due to differences in cell wall composition and detoxification efficiency compared to monocots [

30,36]. The tolerance observed in cowpea at the 5% concentration may be attributed not only to its inherent detoxification pathways (e.g., glutathione conjugation [

32]) but also to the hormetic upregulation of its antioxidant system (as demonstrated in

Section 4.1), which counteracts the mild oxidative stress induced by these specific phenolics. This precise chemical characterization allows us to move beyond generic ‘allelopathic potential’ to a targeted understanding of

which compounds, at

what concentrations, drive the dual biostimulant and bioherbicide effects [

30]

4.4. Practical Implications and Framework

These laboratory results suggest that surface application of chopped wheat straw at 2–3 tons per hectare could replicate the beneficial effects of the 5% extract in the field. This practice offers a low-cost, farmer-friendly, and ecologically sound solution. It simultaneously reduces air pollution from burning, suppresses herbicide-resistant weeds, enhances soil fertility, and boosts cowpea productivity—aligning perfectly with circular economy and climate-smart agriculture principles [

34]. The integrated framework presented in

Figure 10 conceptualizes this sustainable approach.

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Research

It is crucial to acknowledge this study’s limitations. First, experiments were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions; field validation is essential to account for dynamic environmental variables. Second, aqueous extracts capture only water-soluble allelochemicals, whereas in-situ straw decomposition releases a broader spectrum over time. Third, the experimental duration was short-term; long-term field trials are needed. Finally, effects on other crops and beneficial soil organisms (e.g., mycorrhizae) remain unexplored. Future research should focus on field validation, optimizing application protocols (timing, incorporation depth), and identifying the specific bioactive compounds via metabolomic profiling to enable the development of standardized biostimulant formulations.

4.6. Validation and Scaling from Lab to Field

The successful translation of laboratory findings to the field is a critical step in agricultural research. This study bridges that gap, demonstrating that the dual-functionality of wheat straw—as a biostimulant for cowpea and a bioherbicide against key weeds—is not merely a controlled-environment phenomenon but a robust, field-applicable strategy. The strong correlation between the optimal aqueous extract concentration (5% w/v) and the optimal field application rate (3 tons/ha) provides a practical, science-based guideline for farmers.

The field results confirmed the hormetic principle on a larger scale. While the 5-ton/ha rate (T3) provided the strongest weed suppression, it came at the cost of reduced cowpea yield, highlighting the delicate balance required for sustainable management. The 3-ton/ha rate (T2) emerged as the clear winner, offering near-maximal weed control (72-80% reduction in biomass) while simultaneously boosting cowpea yield by 58%. This synergy is the hallmark of an effective agroecological practice.

Furthermore, the post-harvest soil analysis provides compelling evidence for the long-term sustainability of this approach. The significant increase in soil organic carbon (SOC) and microbial activity (dehydrogenase) after just one season underscores the potential of straw mulching to reverse soil degradation, a major challenge in Iraqi agriculture. The reduction in bulk density confirms improved soil physical structure, which enhances water infiltration and root growth, creating a more resilient agroecosystem.

This integrated approach directly addresses the core mission of journals like Agronomy for Sustainable Development. It moves beyond a monodisciplinary lab study to a systems-level analysis that explicitly links residue management (an agronomic practice) with crop production, weed ecology, soil health, and ultimately, farm profitability and environmental sustainability.

5. Conclusion

This comprehensive study, encompassing both controlled laboratory bioassays and a full-scale field trial, conclusively demonstrates that wheat straw is a potent, dual-function agricultural input for Iraqi agroecosystems. The optimal application, whether as a 5% (w/v) aqueous extract in controlled settings or as a 3-ton/ha surface mulch in the field, simultaneously:

Stimulates Cowpea Productivity: Enhancing germination, growth, and grain yield by up to 58% through allelopathic hormesis and improved soil conditions.

Suppresses Key Weeds: Reducing the density and biomass of C. arvensis, I. cylindrica, and B. vulgaris by 58-80%.

Ameliorates Soil Health: Increasing soil organic carbon, microbial activity, nutrient availability, and improving soil physical structure.

These findings provide an unequivocal, evidence-based foundation for recommending the surface application of wheat straw as mulch (at 3 tons/ha) to Iraqi farmers. This strategy offers a practical, low-cost, and ecologically sound solution to transform a major environmental liability (straw burning) into a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture. It directly contributes to climate-smart agriculture by reducing CO₂ emissions, cutting herbicide dependency, enhancing soil carbon sequestration, and boosting food security.

Study Limitations and Future Research: While this study now includes crucial field validation, future research should focus on:

Long-term multi-season trials to assess the cumulative effects on soil health and weed seed bank dynamics.

Economic analysis to evaluate the cost-benefit ratio for farmers.

Investigating the impact on non-target beneficial organisms and soil biodiversity.

Optimizing application methods (e.g., incorporation vs. surface mulch) for different soil types and climatic conditions across Iraq.

Acknowledgments

The author extends sincere gratitude to the technical staff of the Plant Physiology Laboratory at [Your University] for their invaluable assistance. Special thanks are due to the Iraqi Ministry of Agriculture for providing critical field data on soil and weed prevalence, and to the Desert Research Center for the supply of native weed seeds.

References

- Ministry of Agriculture, Iraq. Annual Agricultural Statistical Report. Baghdad: Ministry of Agriculture; 2023.

- Lelieveld, J., et al. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525.7569 (2015): 367-371. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 304.5677 (2004): 1623-1627. [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. E. Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.). In: Genetic Resources, Chromosome Engineering, and Crop Improvement. Vol 3. CRC Press, 2005.

- Sarbout, A. K.; Sharhan, M. H.; Salih, A. A. Allelochemical potential of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) in weeds suppression. Sabrao J. Breed. Genet. 2024, 56, 1244–1250. Available online: https://sabraojournal.org/volume-56-no-3-september-2024/. [CrossRef]

- Sarbout, A. K. The combined allelopathic effect of wheat plant residues with doses of mineral fertilizer nitrogen (N) on yield of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) crops. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 685–691. [CrossRef]

- Rice, E. L. Allelopathy. 2nd ed. Academic Press, 1984.

- Calabrese, E. J., & Baldwin, L. A. Hormesis: U-shaped dose responses and their centrality in toxicology. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 22.6 (2001): 285-291. [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi, H. Promotion of seed germination by allelochemicals. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 329–332. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Haig, T.; Pratley, J.; Lemerle, D.; An, M. Allelopathic compounds from Triticum aestivum: Identification and mode of action. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11897–11903. [CrossRef]

- Duke, S. O., et al. Hormesis: is it an important factor in herbicide use and allelopathy? Outlooks on Pest Management 17.1 (2006): 29-33.

- Chon, S. U.; Kim, J. D.; Lee, Y. M. Biological activity and quantification of suspected allelochemicals from sunflower residues. J. Chem. Ecol. 2002, 28, 1559–1573. [CrossRef]

- Blake, G. R., & Hartge, K. H. Bulk density. Methods of soil analysis: Part 1—Physical and mineralogical methods (1986): 363-375.

- Klute, A. Water retention: Laboratory methods. Methods of soil analysis: Part 1—Physical and mineralogical methods (1986): 635-662.

- Keeney, D. R., & Nelson, D. W. Nitrogen—inorganic forms. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2—Chemical and microbiological properties (1982): 643-698.

- Olsen, S. R., et al. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate. USDA Circular 939, 1954.

- Walkley, A., & Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Science 37.1 (1934): 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Casida, L. E., et al. Soil dehydrogenase activity. Soil Science 98.6 (1964): 371-376.

- Benson, H. J. Microbiological Applications: Laboratory Manual in General Microbiology. McGraw-Hill, 2002.

- International Seed Testing Association (ISTA). International Rules for Seed Testing. ISTA, Bassersdorf, Switzerland, 2020.

- Williamson, G. B. Bioassay for allelopathy: Measuring treatment responses with independent controls. Journal of Chemical Ecology 9.2 (1983): 221-233. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R. J. Active ion uptake and maintenance of cation-anion balance: a critical examination of their role in ameliorating rhizosphere acidification. Plant and Soil 236.1 (2001): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Soares, A. R., & Marchiosi, R. (2015). The role of phenolic compounds in plant stress responses. Phytochemistry Reviews, 14(4), 623-655.

- Schimel, J. P., & Bennett, J. Nitrogen mineralization: challenges of a changing paradigm. Ecology 85.3 (2004): 591-602. [CrossRef]

- Maas, E. V., & Hoffman, G. J. Crop salt tolerance—current assessment. Journal of the Irrigation and Drainage Division 103.2 (1977): 115-134. [CrossRef]

- Lipiec, J., et al. Effect of soil compaction on root growth and crop yield in Central and Eastern Europe. International Agrophysics 26.1 (2012): 49-59.

- Blanco-Canqui, H., & Lal, R. Mechanisms of carbon sequestration in soil aggregates. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 23.6 (2004): 481-504. [CrossRef]

- Thalmann, A. Zur Methodik der Bestimmung der Dehydrogenaseaktivität im Boden mittels Triphenyltetrazoliumchlorid (TTC). Landwirtschaftliche Forschung 21 (1968): 249-258.

- Fierer, N.; Schimel, J. P.; Cates, R. G. Microbial community composition and soil enzyme activities in a chronosequence of Pinus ponderosa stands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 1601–1610. [CrossRef]

- Weir, T. L.; Park, S. W.; Vivanco, J. M. The rhizosphere and allelopathy: A review of the evidence and implications for plant communities. Plant Soil 2004, 267, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bohnert, H. J., & Jensen, R. G. Strategies for engineering water-stress tolerance in plants. Trends in Biotechnology 14.3 (1996): 89-97. [CrossRef]

- Cedergreen, N. Quantifying hormesis in ecological risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 723–733. [CrossRef]

- Weston, L. A., & Duke, S. O. Weed and crop allelopathy. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 22.3-4 (2003): 367-389. [CrossRef]

- Einhellig, F. A. The physiology of allelochemical action: clues and views. Allelopathy: A Physiological Process with Ecological Implications. Springer, 2007. 1-26.

- Calabrese, E. J. (2013). Biphasic dose responses in biology, toxicology, and medicine: Accounting for their generalizability and quantitative features. Environmental Pollution, 182, 452-458. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).