Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Conservation: Conservation Agriculture

1.2. Tillage: Conservation tillage:

1.3. Soil: Soil conservation

1.4. Soil: Soil health

2. Materials and Methods

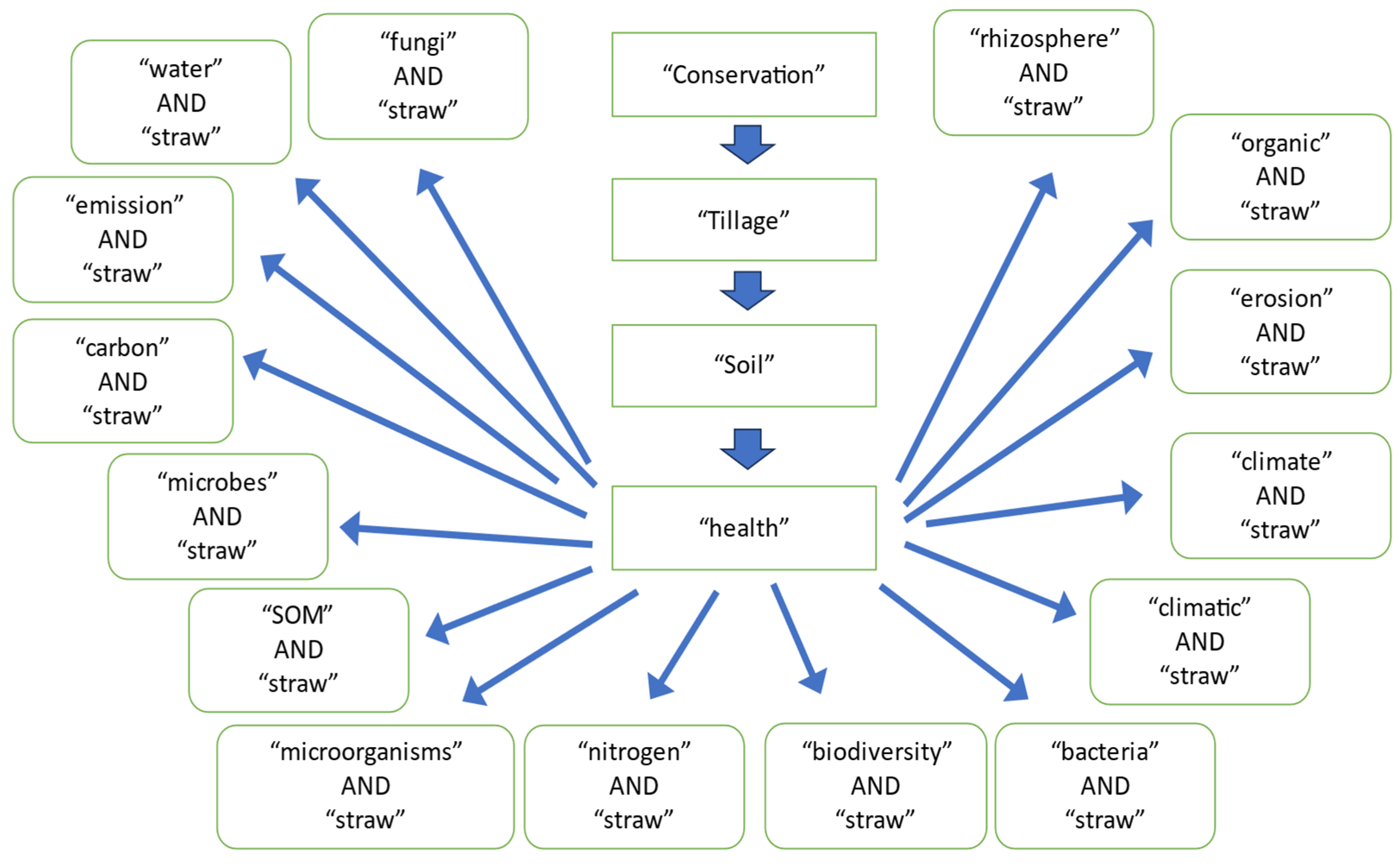

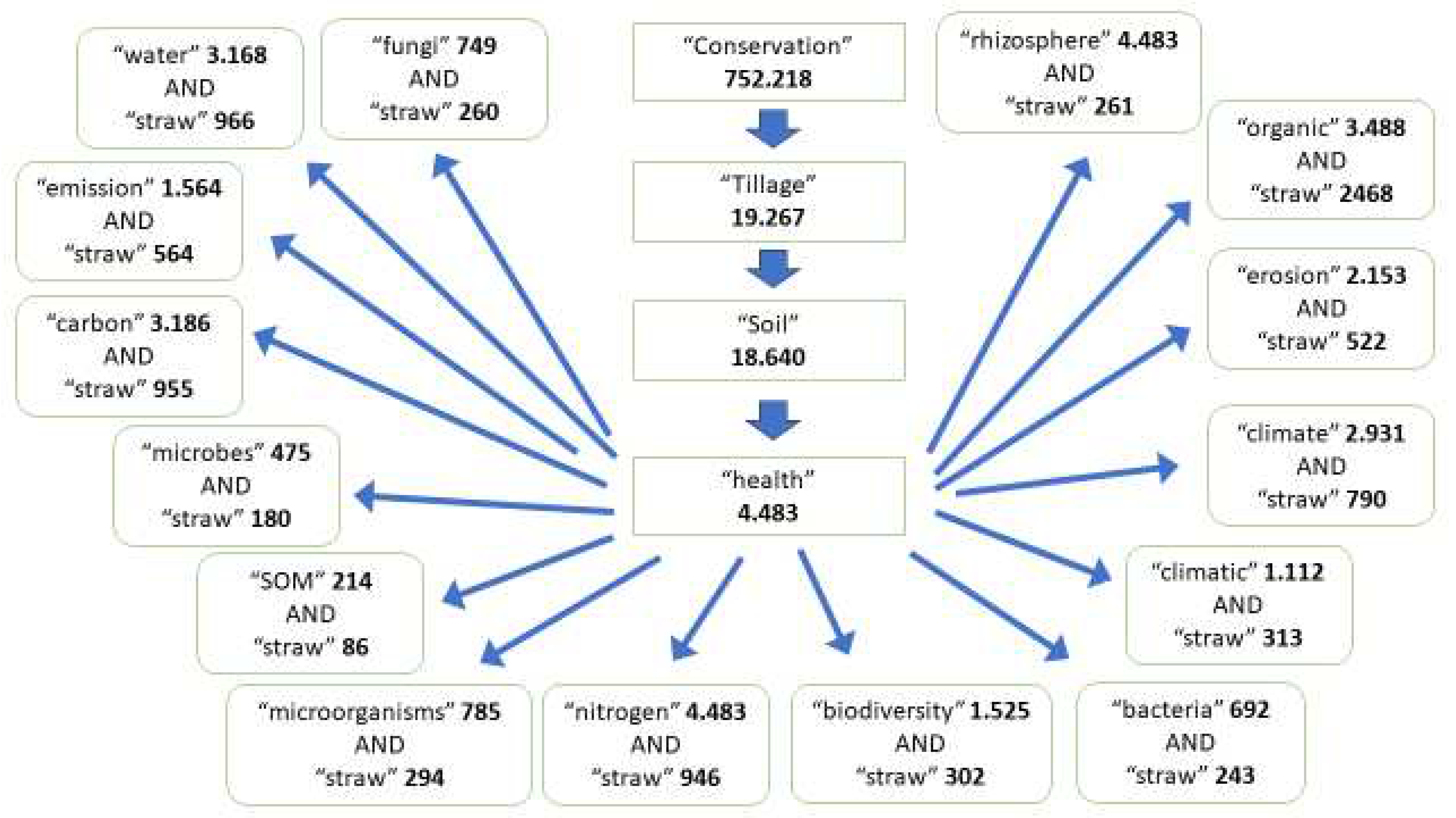

2.1. Search Strategy – Using Scopus & Web of Science to Thoroughly Search Scientific Literature

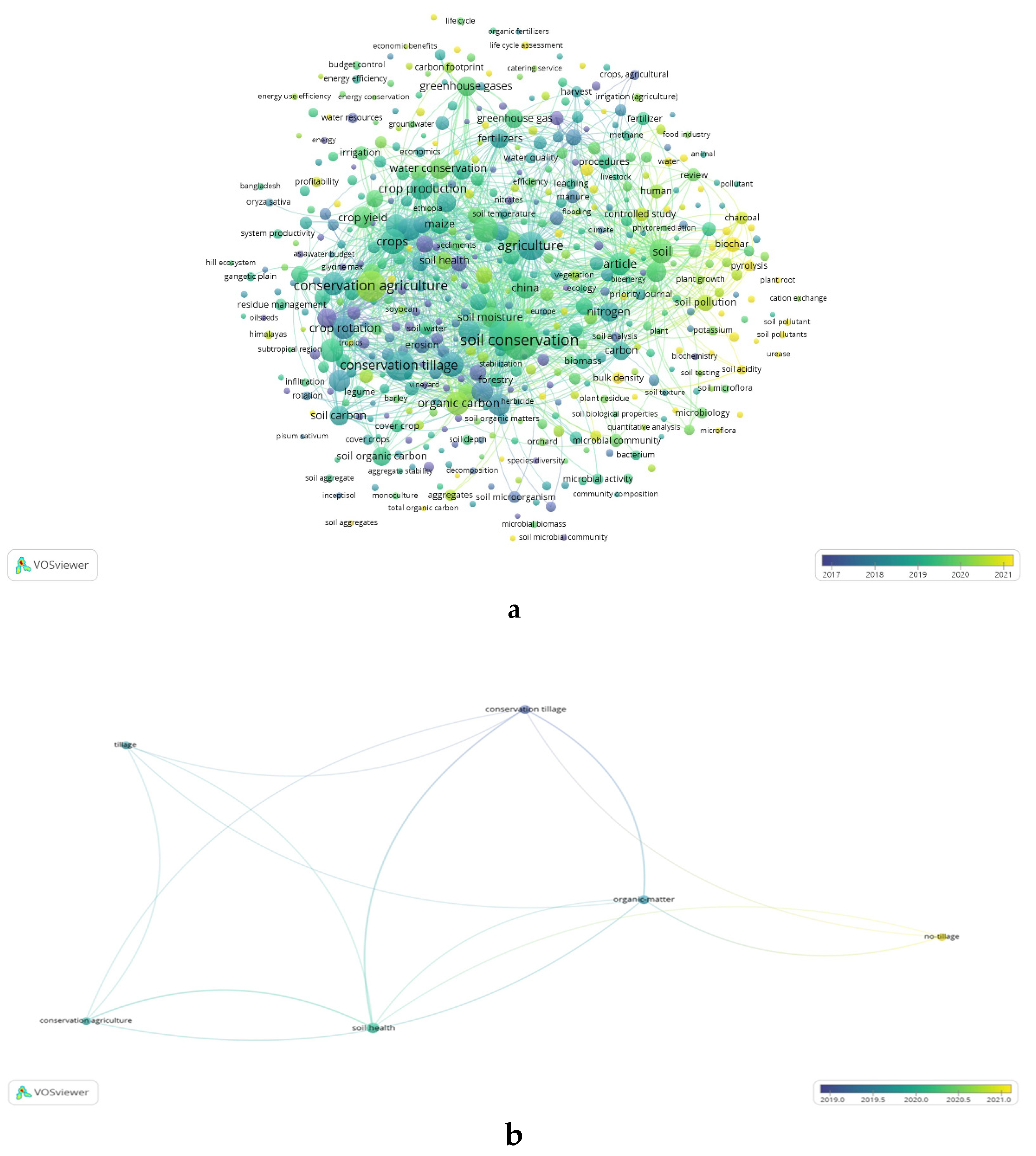

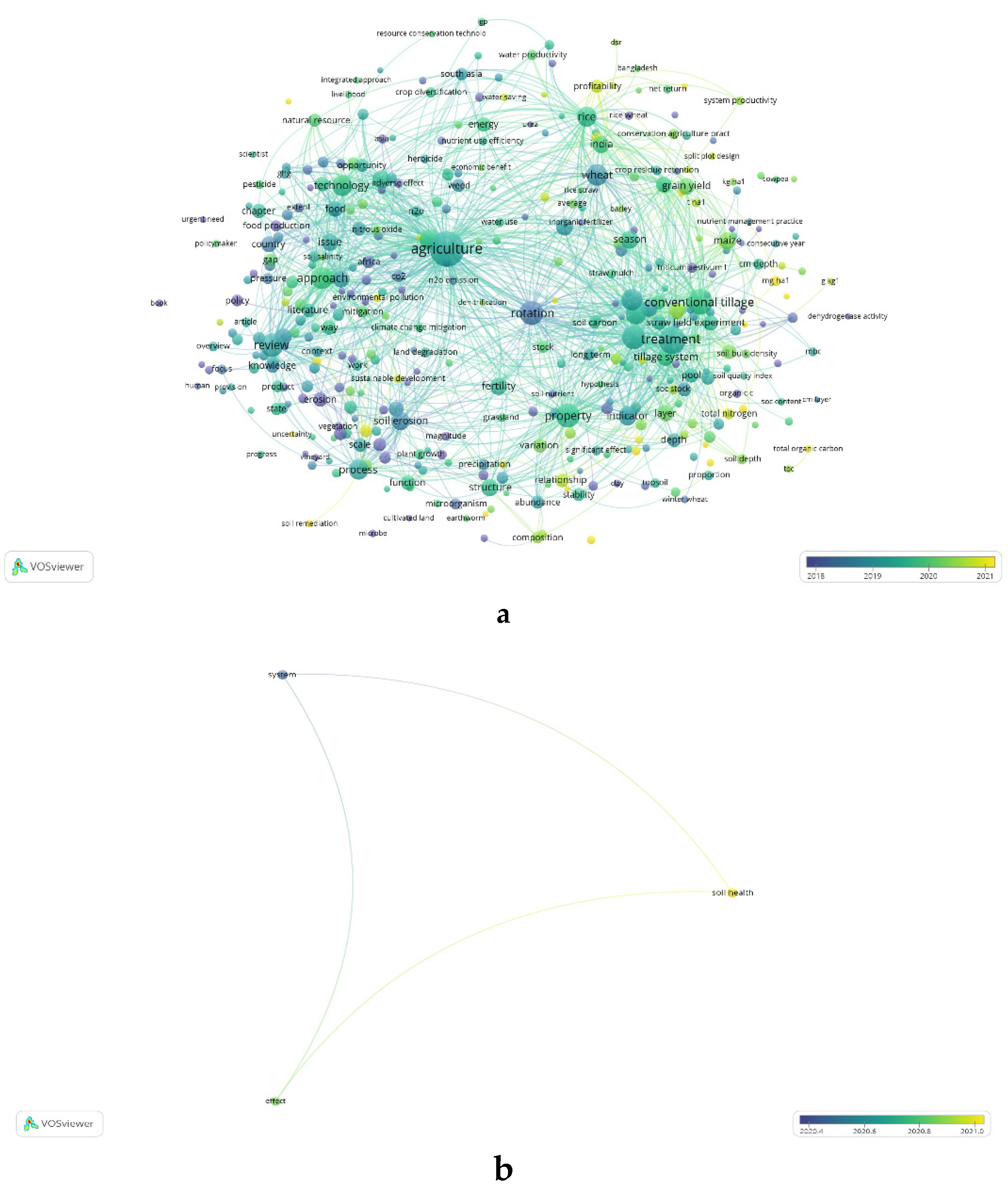

2.2. Data Analysis and Bibliometric Mapping

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Scopus and the Web of Science bibliographic database studies

3.2. Using Scopus to Thoroughly Search Scientific Literature

3.2.1. The “Nitrogen” AND “Straw” Results Based on the Literature Search Query on Scopus

3.2.2. The “Rhizosphere” AND “Straw” Results Based on the Literature Search Query on Scopus

3.2.3. The “Carbon” AND “Straw” Results Based on the Literature Search Query on Scopus

3.2.3. The “Water” AND “Straw” Results Based on the Literature Search Query on Scopus

3.2.4. The “Climate” AND “Straw” Results Based on the Literature Search Query on Scopus

3.2.5. The “Emission” AND “Straw” Results Based on the Literature Search Query on Scopus

3.2.5. The “Biodiversity” AND “Straw” Results Based on the Literature Search Query on Scopus

3.2.6. The “Climatic” AND “Straw” Results Based on the Literature Search Query on Scopus

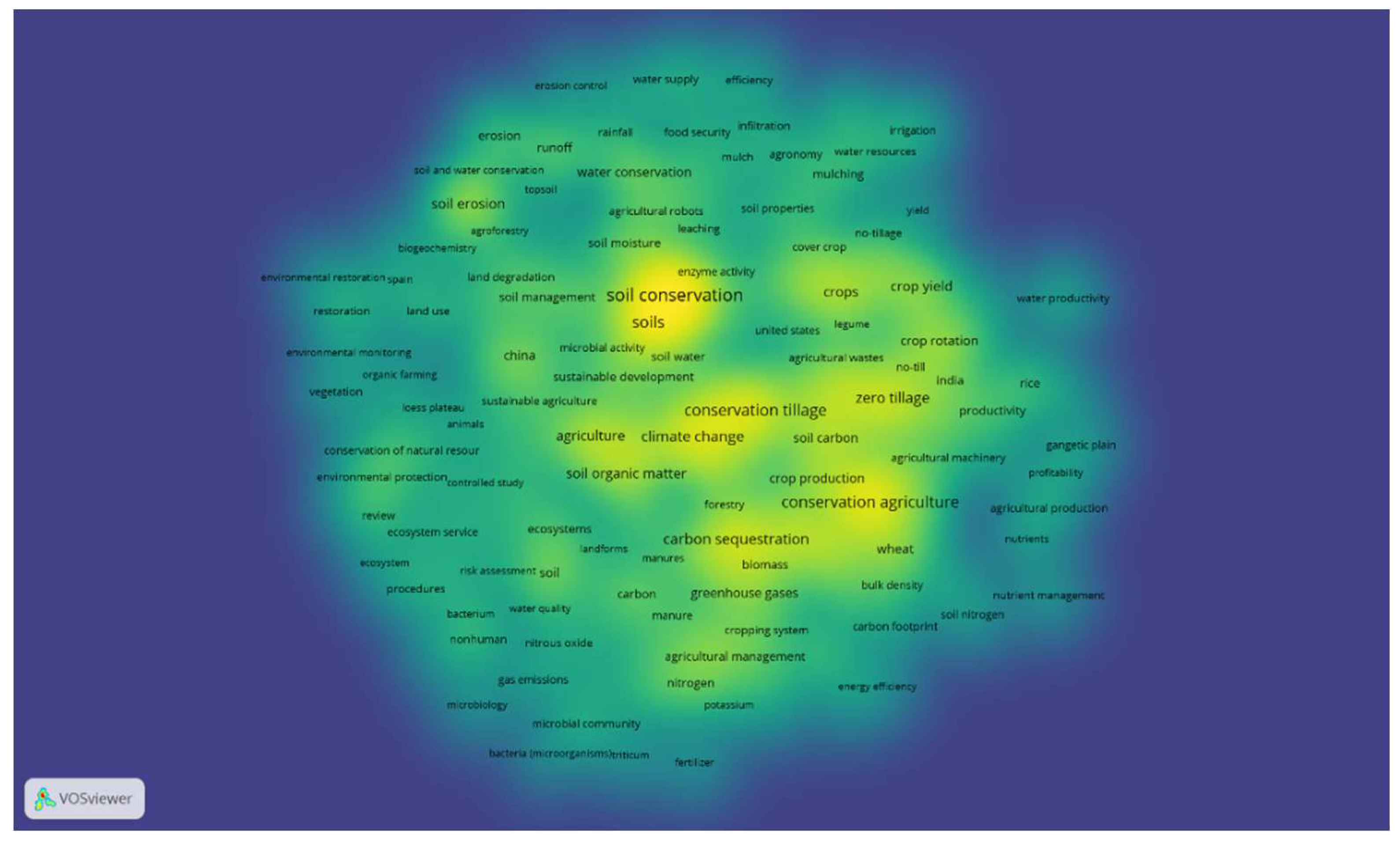

4. Discussion

- ▪

- crop production; system productivity; crop rotation; crop practice; cover crop; crop residue; legume and Brassica napus;

- ▪

- conservation tillage; zero tillage; tillage and no-tillage;

- ▪

- soil; soil property; soil quality; soil management; soil conservation; soil aggregate; soil microorganism; soil pollution; soil remediation; soil organic matter; soil carbon; soil organic carbon; soil amendment; soil erosion; soil degradation; soil ecosystem; soil fertility; soil temperature; soil acidity; soil moisture; aggregates; soil aggregates; porosity; soil depth; topsoil and gangetic plain

- ▪

- rhizosphere and plant roots;

- ▪

- chemistry; metabolism; bulk density; pyrolysis; and bioremediation

- ▪

- nutrients; fertilizers; carbon; carbon sequestration; nitrogen; potassium; phosphorous; heavy metals and cadmium

- ▪

- water conservation; soil water; water supply; runoff and evapotranspiration

- ▪

- biomass; straw; mulch; mulching and residue management;

- ▪

- organic matter; organic compounds; manure; biochar and charcoal;

- ▪

- microbiology; microflora; microbial community; microbial diversity; microbiota; bacteria; microorganisms; fungus; nematoda; proteobacteria and actinobacteria

- ▪

- climate change; global warming; greenhouse gases; carbon dioxide; emission control; gas emissions and drought;

- ▪

- sustainable development; sustainability; ecosystems; food supply; food security; environmental protection; pollution; energy use; environmental restoration, and conservation of natural resources

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Report. Department of economic and social affairs. World population projected to reach 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100. Assessed in 07/23. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-population-projected-reach-98-billion-2050-and-112-billion-2100.

- Banerjee, S.; Walder, F.; Büchi, L.; Meyer, M.; Held, A.Y.; Gattinger, A.; Keller, T.; Charles, R.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Agricultural intensification reduces microbial network complexity and the abundance of keystone taxa in roots. The ISME Journal 2019, 13, 1722–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, E.M.; Baird, J.; Baulch, H.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Fraser, E.; Loring, P.; Morrison, P.; Parrott, L.; Sherren, K.; Winkler, K.J.; Cimon-Morin, J.; Fortin, M.-J.; Kurylyk, B.L.; Lundholm, J.; Poulin, M.; Rieb, J.T.; Gonzalez, A.; Hickey, G.M.; Humphries, M.; Bahadur, K.; Lapen, D.K.C. Ecosystem services and the resilience of agricultural landscapes, Chapter One. Editor(s): Bohan, D.A.; Vanbergen, A.J. Advances in Ecological Research, 2021, 64, 1-43. Academic Press, ISSN 0065-2504, ISBN 9780128229798. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, G.; Mohanty, S.; Shreya, D. Conservation agriculture-a way to improve soil health. Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences 2020, 8, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jat, M.L.; Chakraborty, D.; Ladha, J.K.; Rana, D.S.; Gathala, M.K.; McDonald, A.; Gerard, B. Conservation agriculture for sustainable intensification in South Asia. Nature Sustainability 2020, 3, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, M.J.; Carvalho, M.; Brito, I. Functional Diversity of Mycorrhiza and Sustainable Agriculture, Chapter 1 in: Challenges to Agriculture Systems, Editor(s): Goss, M.J.; Carvalho, M.; Brito, I. Academic Press, 2017, 1-14, ISBN 9780128042441. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Maitra, S.; Ahmed, S.; Mitra, B.; Ahmad, Z.; Garai, S.; Mondal, M.; Adeel, M.; Shankar, T.; Meena, R.S. Legumes for nutrient management in the cropping system, Chapter 6 in: Advances in Legumes for Sustainable Intensification, Editor(s): Meena, R.S.; Kumar, S.; 2022, Academic Press, 93-112, ISBN 9780323857970. [CrossRef]

- Devkota, M.; Singh, Y.; Yigezu, Y.A.; Bashour, I.; Mussadek, R.; Mrabet, R. Conservation Agriculture in the drylands of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: Past trend, current opportunities, challenges and future outlook, Chapter Five in: Advances in Agronomy, Editor(s): Sparks, D.L.; Academic Press, 2022, 172, 253-305, ISSN 0065-2113, ISBN 9780323989534. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Durán-Zuazo, B.; Soriano Rodríguez, V.H.; García-Tejero, M.; Gálvez Ruiz, I.F.; Cuadros Tavira, B. Conservation agriculture as a sustainable system for soil health: A review. Soil Systematic 2022, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, S.; Lembe, D.; Magwaza, G.; Nozipho, S.; Motsa, M.; Sithole, N.J.; Ncama, K. Long-term no-till conservation agriculture and nitrogen fertilization on soil micronutrients in a semi-arid region of south Africa. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafkan, K.; Valizadeh, N.; Khannejad, S.; Kianmehr, N.; Bijani, M.; Hayati, D. What drives farmers to use conservation agriculture? Application of mediated protection motivation theory. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 991323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Conservation agriculture. Conservation agriculture principles. Available online: https://www.fao.org/conservation-agriculture/overview/what-is-conservation-agriculture/en/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- FAO. Conservation agriculture. Available online: https://www.fao.org/conservation-agriculture/overview/conservation-agriculture-principles/en/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Gonzalez-Sanchez, E.J.; Veroz-Gonzalez, O.; Blanco-Roldan, G.L.; Marquez-Garcia, F.; Carbonell-Bojollo, R. A renewed view of conservation agriculture and its evolution over the last decade in Spain. Soil and Tillage Research 2015, 146, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sánchez, E.J.; Kassam, A.; Basch, G.; Streit, B.; Holgado-Cabrera, A.; Triviño-Tarradas, P. Conservation agriculture and its contribution to the achievement of agri-environmental and economic challenges in Europe[J]. AIMS Agriculture and Food 2016, 1, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahran, S.; Li, G.; Rahim, N.; Tahir, M.M. Sustainable conservation tillage technique for improving soil health by enhancing soil physicochemical quality indicators under wheat mono-cropping system conditions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittarello, M.; Dal Ferro, N.; Chiarini, F.; Morari, F.; Carletti, P. Influence of tillage and crop rotations in organic and conventional farming systems on soil organic matter, bulk density and enzymatic activities in a short-term field experiment. Agronomy 2021, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, İ.; Günal, H.; Acar, M.; Acir, N.; Barut, Z.B.; Budak, M. Strategic tillage may sustain the benefits of long-term no-till in a vertisol under Mediterranean climate. Soil and Tillage Research 2019, 185, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UC Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program, 2017. Conservation Tillage. What is Sustainable Agriculture? UC Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Available online: https://sarep.ucdavis.edu/sustainable-ag/conservation-tillage (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Ruis, S.J. No-tillage and soil physical environment. Geoderma 2018, 326, 164–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Li, G.; Rahim, N.; Tahir, M.M. Sustainable conservation tillage technique for improving soil health by enhancing soil physicochemical quality indicators under wheat mono-cropping system conditions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obour, A.K.; Holman, J.D.; Simon, L.M.; Schlegel, A.J. Strategic tillage effects on crop yields, soil properties, and weeds in dryland no-tillage systems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obour, A.K.; Mikha, M.M.; Holman, J.D.; Stahlman, P.W. Changes in soil surface chemistry after fifty years of tillage and nitrogen fertilization. Geoderma 2017, 308, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Gravuer, K.; Bossange, A.V.; Mitchell, J.; Scow, K. Long-term use of cover crops and no-till shift soil microbial community life strategies in agricultural soil. PLoS ONE 2018, 1513, 0192953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.P.; Moody, P.W.; Bell, M.J.; Seymour, N.P.; Dalal, R.C.; Freebairn, D.M.; Walker, S.R. Strategic tillage in no-till farming systems in Australia’s northern grains-growing regions: II. Implications for agronomy, soil and environment. Soil and Tillage Research 2015, 152, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conservation Institute. Soil conservation-What do i need to kno about it? Learn about its importance. Available online: https://www.conservationinstitute.org/soil-conservation/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- EOS Data analytics. Soil conservation methods and benefits of implementation. Available online: https://eos.com/blog/soil-conservation/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Vagelas, I.; Leontopoulos, S. Modeling the overdispersion of Pasteuria penetrans endospores. Parasitologia 2022, 2, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontopoulos, S.; Vagelas, I.; Gravanis, F.T.; Gowen, S.R. The effect of certain bacteria and fungi on the biology of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne sp. Mutitrophic Interactions in Soil and Integrated Control IOBC wprs Bulletin 2014, 27, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Leontopoulos, S.; Petrotos, K.; Anatolioti, V.; Skenderidis, P.; Tsilfoglou, S.; Vagelas, I. Chemotactic responses of Pseudomonas oryzihabitans and second stage juveniles of Meloidogyne javanica on tomato root tip exudates. International Journal of Food and Biosystems Engineering 2017, 5, 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Leontopoulos, S.; Petrotos, K.; Anatolioti, V.; Skenderidis, P.; Tsilfoglou, S.; Papaioannou, C.; Kokkora, M.; Vagelas, I. Preliminary studies on mobility and root colonization ability of Pseudomonas oryzihabitans. International Journal of Food and Biosystems Engineering 2017, 3, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Leontopoulos, S.; Petrotos, K.; Anatolioti, V.; Skenderidis, P.; Tsilfoglou, S.; Vagelas, I. Effects of cells and cells-free filtrates supernatant solution of Pseudomonas oryzihabitans on root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne javanica). International Journal of Food and Biosystems Engineering 2017, 6, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Naz, M.; López-Sánchez, R.C.; Fuentes-Lara, L.O.; Cabrera-De la Fuente, M.; Benavides-Mendoza, A. Soil health and plant stress mitigation, Chapter 6. Editor(s): Ghorbanpour, M.; Shahid, M.A.; In: Plant Stress Mitigators, Academic Press, 2023, 99-114. ISBN 9780323898713. [CrossRef]

- Lambakis, D.; Skenderidis, P.; Leontopoulos, S. Technologies and extraction methods of polyphenolic compounds derived from pomegranate (Punica granatum) peels. A mini review. Processes 2021, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontopoulos, S.; Skenderidis, P.; Skoufogianni, G. Potential use of medicinal plants as biological crop protection agents. Biomedical Journal of Scientific and Technical Research 2020, 25, 19320–19324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontopoulos, S.; Skenderidis, P.; Kalorizou, H.; Petrotos, K. Bioactivity potential of polyphenolic compounds in human health and their effectiveness against various food borne and plant pathogens. A review. International Journal of Food and Biosystems Engineering 2017, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sadras, V.; Alston, J.; Aphalo, P.; Connor, D.; Ford-Denison, R.; Fischer, T.; Gray, R.; Hayman, P.; Kirkegaard, J.; Kirchmann, H.; Kropff, M.; Lafitte, H.R.; Langridge, P.; Lenne, J.; Mínguez, M.I.; Passioura, J.; Porter, J.R.; Reeves, T.; Rodriguez, D.; Ryan, M.; Villalobos, F.J.; Wood, D. Making science more effective for agriculture, Chapter Four. Editor(s): Sparks, D.L. In: Advances in Agronomy, Academic Press, 2020, 163, 153-177. ISSN 0065-2113, ISBN 9780128207697. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y-H; Wang, N.; Yu, M.-K.; Yu, J.-G.; Xue, L.-H. Rhizosphere and straw return interactively shape rhizosphere bacterial community composition and nitrogen cycling in paddy soil. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 945927. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Noya, Y.E.; Gómez-Acata, S.; Montoya-Ciriaco, N.; Rojas-Valdez, A.; Suárez-Arriaga, M.C.; Valenzuela-Encinas, C.; Jiménez-Bueno, N.; Verhulst, N.; Govaerts, B.; Dendooven, L. Relative impacts of tillage, residue management and crop-rotation on soil bacterial communities in a semi-arid agroecosystem, Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2013, 65, 86-95. ISSN 0038–0717. [CrossRef]

- Kavamura, V.N.; Mendes, R.; Bargaz, A.; Mauchline, T.H. Defining the wheat microbiome: Towards microbiome-facilitated crop production. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2021, 19, 1200–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, A.; Malla, M.A.; Khan, F.; Chowdary, K.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.; Khare, P.K.; Khan, M.L. Soil microbiome: A key player for conservation of soil health under changing climate. Biodiversity Conservatory 2019, 28, 2405–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaze-Corcoran, S.; Hashemi, M.; Sadeghpour, A.; Jahanzad, E.; Afshar, R.K.; Liu, X.; Herbert, S.J. Understanding intercropping to improve agricultural resiliency and environmental sustainability, Chapter Five. Editor(s): Sparks, D.L. In: Advances in Agronomy, Academic Press, 2020, 162, 199-256. ISSN 0065-2113, ISBN 9780128207673. [CrossRef]

- Beals, K.K. Making sense of soil microbiome complexity for plant and ecosystem function in a changing World. PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2022. Available online: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/7139.

- Yuan, L.; Gao, Y.; Mei, Y. Liu, J.; Kalkhajeh, Y.K.; Hu, H.; Huang, J. Effects of continuous straw returning on bacterial community structure and enzyme activities in rape-rice soil aggregates. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahdan, S.F.M.; Ji, L.; Schädler, M.; Wu, Y.-T.; Sansupa, Ch.; Tanunchai, B.; Buscot, F.; Purahong, W. Future climate conditions accelerate wheat straw decomposition alongside altered microbial community composition, assembly patterns, and interaction networks. ISME Journal 2023, 17, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagelas, I.; Leontopoulos, S. A Bibliometric analysis and a citation mapping process for the role of soil recycled organic matter and microbe interaction due to climate change using scopus database. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 581–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mekkaoui, A.; Moussadek, R.; Mrabet, R.; Douaik, A.; El Haddadi, R.; Bouhlal, O.; Elomari, M.; Ganoudi, M.; Zouahri, A.; Chakiri, S. Effects of tillage systems on the physical properties of soils in a semi-arid region of Morocco. Agriculture 2023, 13, 10–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ugalde, O.; Virto, I.; Bescansa, P.; Imaz, M.; Enrique, A.; Karlen, D.L. No-tillage improvement of soil physical quality in calcareous, degradation-prone, semiarid soils. Soil & Tillage Research 2009, 106, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurothe, R.S.; Kumar, G.; Singh, R.K.; Hb, S.; Tiwari, S.; Vishwakarma, A.K.; Sena, D.R.; Pande, V.C. Effect of tillage and cropping systems on runoff, soil loss and crop yields under semiarid rainfed agriculture in India. Soil & Tillage Research 2014, 140, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtyobile, M.; Muzangwa, L.; Mnkeni, P.N. Tillage and crop rotation effects on soil carbon and selected soil physical properties in a Haplic Cambisol in Eastern Cape, South Africa. Soil and Water Research 2019, 15, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, B.; Coulibaly, K.T.; Kohio, E.N.; Doumbia, S.; Ouédraogo, S.; Nacro, H.B. Effets du Système de Culture sous couverture Végétale (SCV) sur les flux hydriques d’un sol ferrugineux à l’Ouest du Burkina Faso. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2018, 12, 1770–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghrour, M.; Moussadek, R.; Mrabet, R.; Dahan, R.; El-Mourid, M.; Zouahri, A.; Mekkaoui, M. Long and midterm effect of conservation agriculture on soil properties in dry areas of Morocco. Applied and Environmental Soil Science 2016, 2016, 6345765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekkaoui, A.E.; Moussadek, R.; Mrabet, R.; Chakiri, S.; Douaik, A.; Ghanimi, A.; Zouahri, A. The conservation agriculture in northwest of Morocco (Merchouch area): The impact of no-till systems on physical properties of soils in semi-arid climate. E3S Web of Conferences 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, B.A. Utilization of waste straw and husks from rice production: A review. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts 2020, 5, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkhajeh, Y.K.; He, Z.; Yang, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Gao, H.; Ma, C. Co-application of nitrogen and straw-decomposing microbial inoculant enhanced wheat straw decomposition and rice yield in a paddy soil. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2021, 4, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Chen, P.; Du, Q.; Yang, H.; Luo, K.; Wang, X.; Yang, F.; Yong, T.; Yang, W. Soil organic matter, aggregates, and microbial characteristics of intercropping soybean under straw incorporation and N input. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, R.; Ren, T.; Lei, M.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Yangyang, Z.; Lu, J. Tillage and straw-returning practices effect on soil dissolved organic matter, aggregate fraction and bacteria community under rice-rice-rapeseed rotation system. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 287, 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Iqbal, A.; He, L.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, S.; Ali, I.; Ullah, S.; Yan, B.; Jiang, L. Long-term no-tillage and straw retention management enhances soil bacterial community diversity and soil properties in southern China. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moebius-Clune, B.N.; Es, H.V.; Idowu, O.J.; Schindelbeck, R.R.; Moebius-Clune, D.J.; Wolfe, D.W.; Abawi, G.S.; Thies, J.E.; Gugino, B.K.; Lucey, R.F. Long-term effects of harvesting maize Stover and tillage on soil quality. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2008, 72, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, D.A.; Chang, C. Long-term impacts of residue harvesting on soil quality. Soil & Tillage Research 2013, 134, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamil, M.B.; Little, J.; Nafziger, E.D. Corn residue, tillage, and nitrogen rate effects on soil properties. Soil & Tillage Research 2015, 151, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamil, M.B.; Nafziger, E.D. Corn residue, tillage, and nitrogen rate effects on soil carbon and nutrient stocks in Illinois. Geoderma 2015, 253, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.R.; van Es, H.M.; Schindelbeck, R.R.; Ristow, A.; Ryan, M.R. No-till and cropping system diversification improve soil health and crop yield. Geoderma 2018, 328, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, S.; Dalal, R.C. No-till farming: Prospects, challenges – productivity, soil health, and ecosystem services. Soil Research 2022, 60, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, D.R.; Dowler, C.C.; Johnson, A.W.; Baker, S.H. Conservation tillage and seedling diseases in cotton and soybean double-cropped with Triticale. Plant Disease 1995, 79, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwath, W.R.; Kuzyakov, Y. The potential for soils to mitigate climate change through carbon sequestration. Developments in Soil Science 2018, 35, 61–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J.; Clarke, L.E. The effect of no-till farming on the soil functions of water purification and retention in north-western Europe: A literature review. Soil and Tillage Research 2019, 189, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanic, M.; Żuk-Gołaszewska, K.; Orzech, K. Catch crops and the soil environment – a review of the literature. Journal of Elementology 2018, 24, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Smith, M.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Wright, J.L. Revised FAO procedures for calculating evapotranspiration: Irrigation and drainage paper No. 56 with Testing in Idaho. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Cárceles Rodríguez, B.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Soriano Rodríguez, M.; García-Tejero, I.F.; Gálvez Ruiz, B.; Cuadros Tavira, S. Conservation agriculture as a sustainable system for soil health: A review. Soil Systems 2022, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Cui, S.; Jagadamma, S.; Zhang, Q. Residue retention and minimum tillage improve physical environment of the soil in croplands: A global meta-analysis. Soil and Tillage Research 2019, 194, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Bossuyt, H.; DeGryze, S.; Denef, K. A history of research on the link between (micro)aggregates, soil biota, and soil organic matter dynamics. Soil and Tillage Research 2004, 79, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubin, M.R.; Oliveira, D.M.; Feigl, B.J.; Pimentel, L.G.; Lisboa, I.P.; Gmach, M.R.; Varanda, L.L.; Morais, M.C.; Satiro, L.S.; Popin, G.V.; Paiva, S.R.; Santos, A.K.; Vasconcelos, A.L.; Melo, P.L.; Cerri, C.E.; Cerri, C.C. Crop residue harvest for bioenergy production and its implications on soil functioning and plant growth: A review. Scientia Agricola 2018, 75, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.W. Impact of soil organic matter on soil properties—A review with emphasis on Australian soils. Soil Research 2015, 53, 605–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Shen, J.; Luo, Y.; Scheu, S.; Ke, X. Tillage, residue burning and crop rotation alter soil fungal community and water-stable aggregation in arable fields. Soil and Tillage Research 2010, 107, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azooz, R.; Arshad, M. Soil infiltration and hydraulic conductivity under long-term no-tillage and conventional tillage systems. Canadian Journal of Soil Science 1996, 76, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).