Submitted:

04 July 2024

Posted:

05 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Soil Characteristics

2.2. Treatments and Experimental Setup

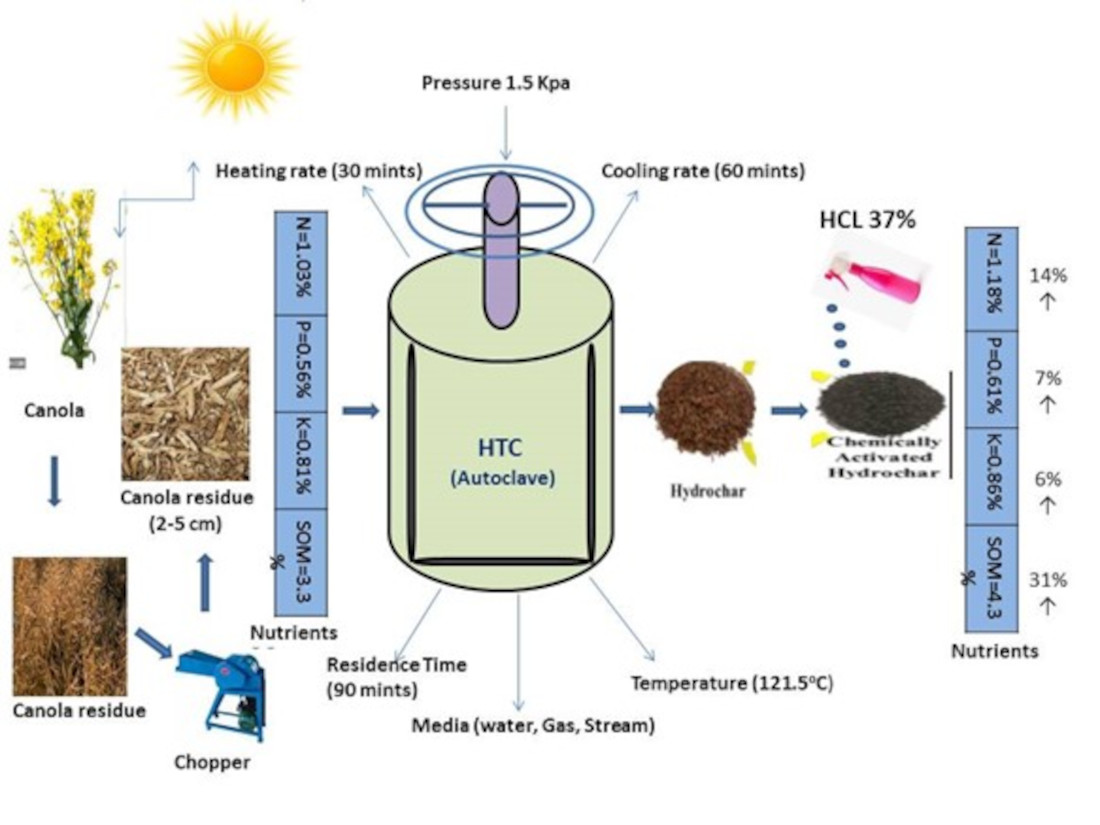

2.3. Procedure for Hydrochar Preparation

2.4. Field History

2.5. Data Collection

2.5.1. Plants Pigments

2.5.2. Grains and Stover Nitrogen Content

2.5.3. Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Nitrogen Uptake

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenological and Growth Parameters

3.2. Plant Height

3.3. Biological Yield

3.4. Harvest Index

3.5. Grain Yield

3.6. Ear Density

3.7. Ear Length

3.8. Grains Ear-1

3.9. Thousand Grain Weight

3.10. Grain N Content

3.11. Stover N Content

3.12. Nitrogen Uptake

3.13. Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE)

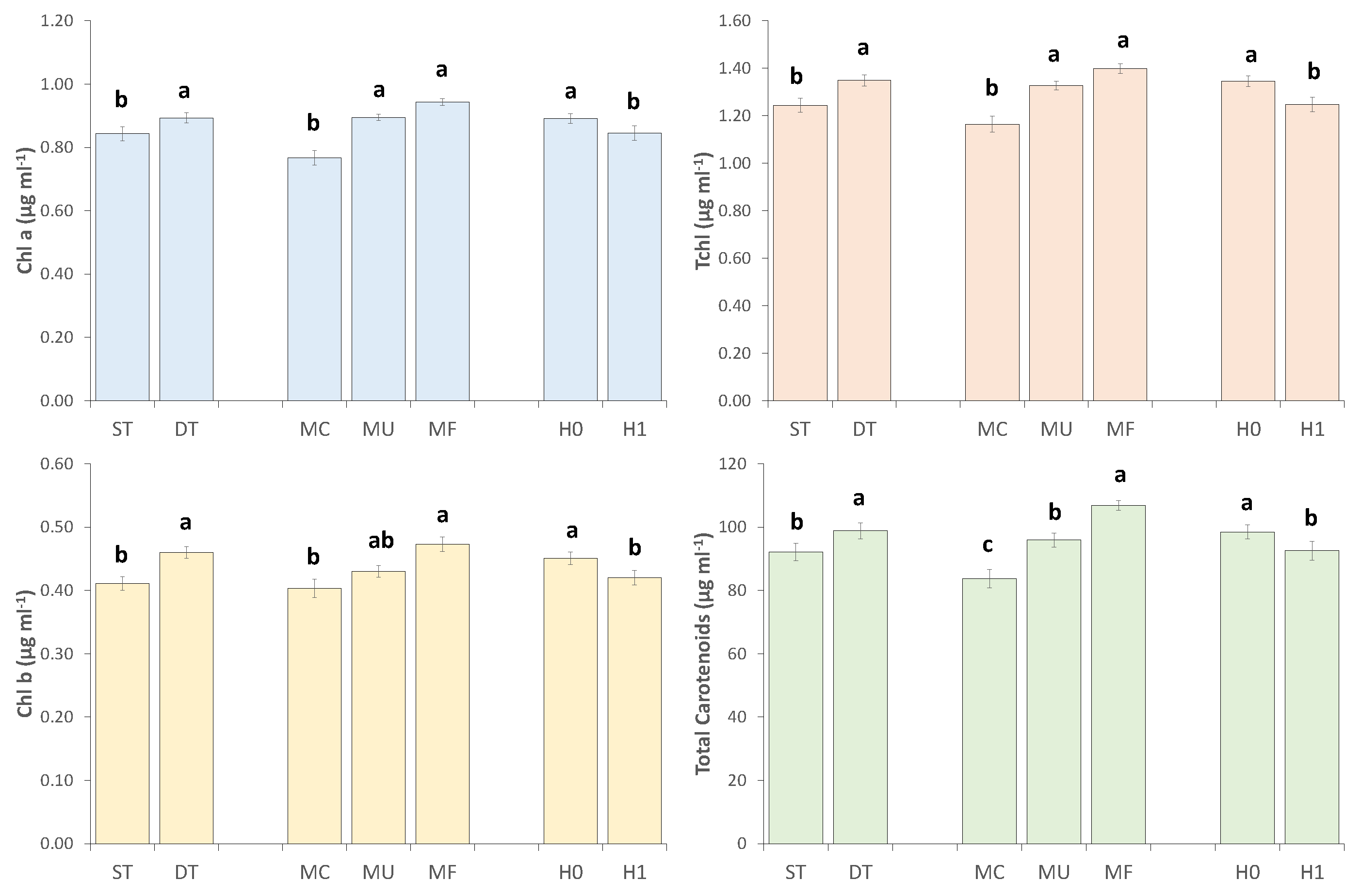

3.14. Plant Photo Pigments

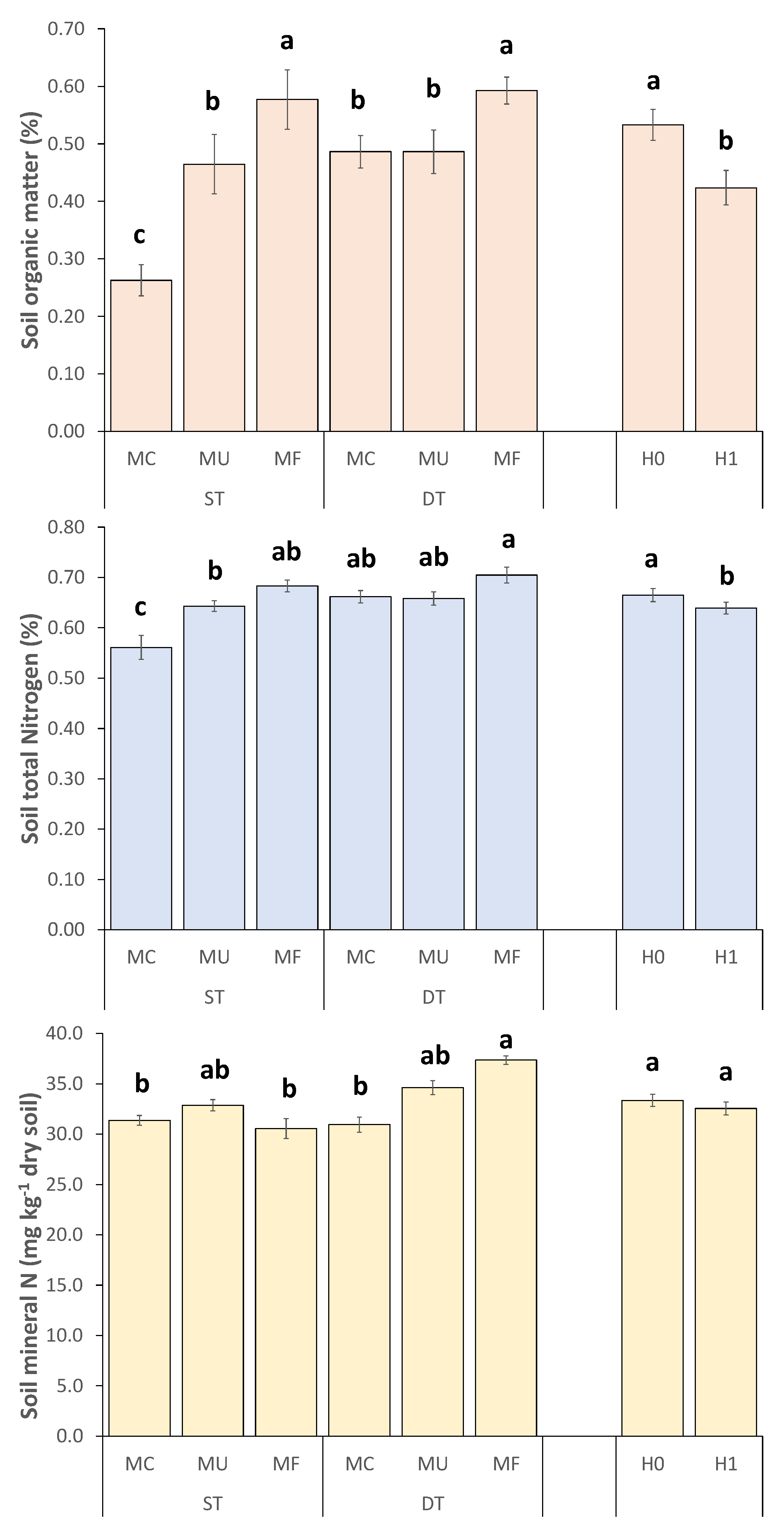

3.15. Soil Properties

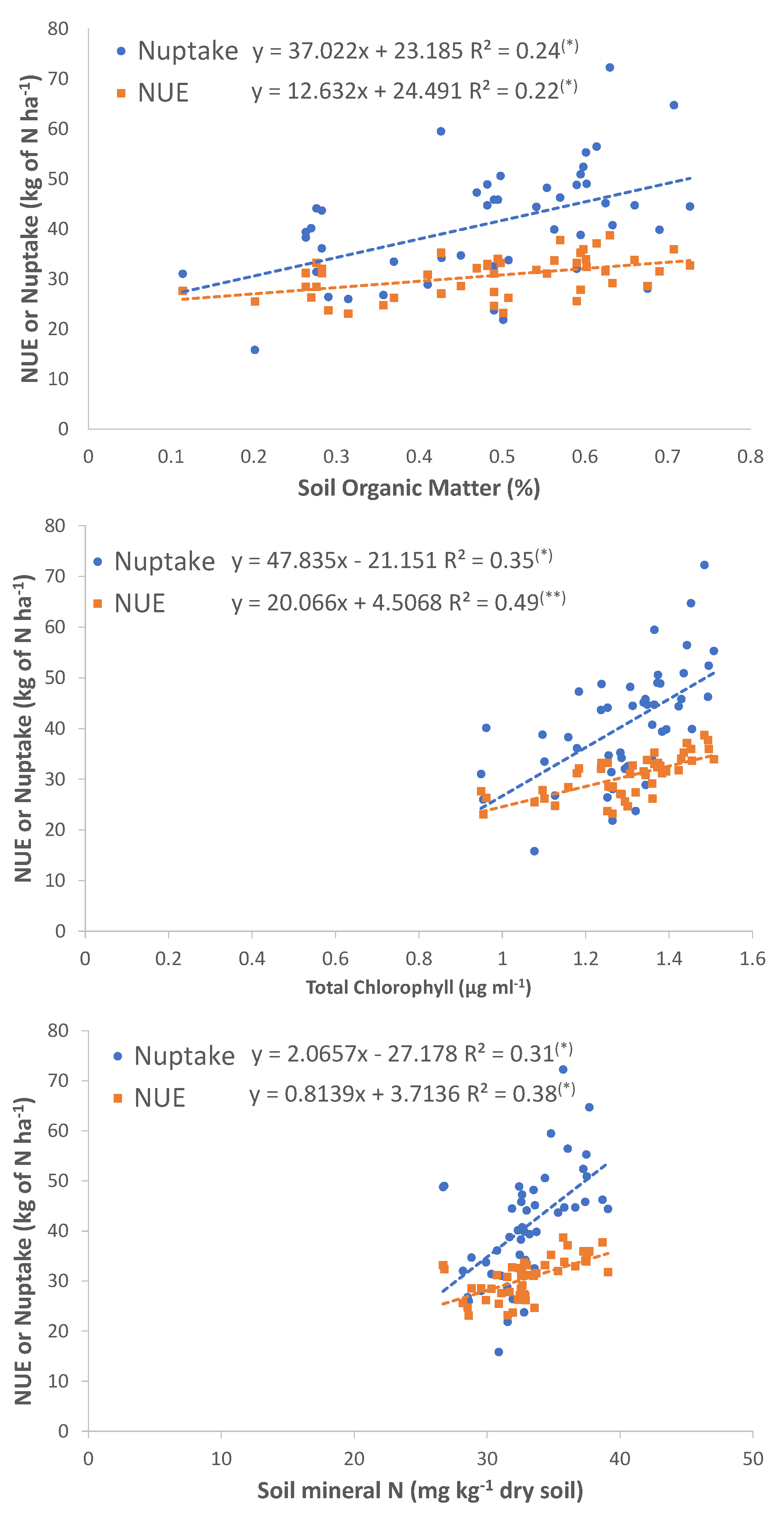

3.16. Relationship of SOM, Total Chl and SMN with NUE and N Uptake

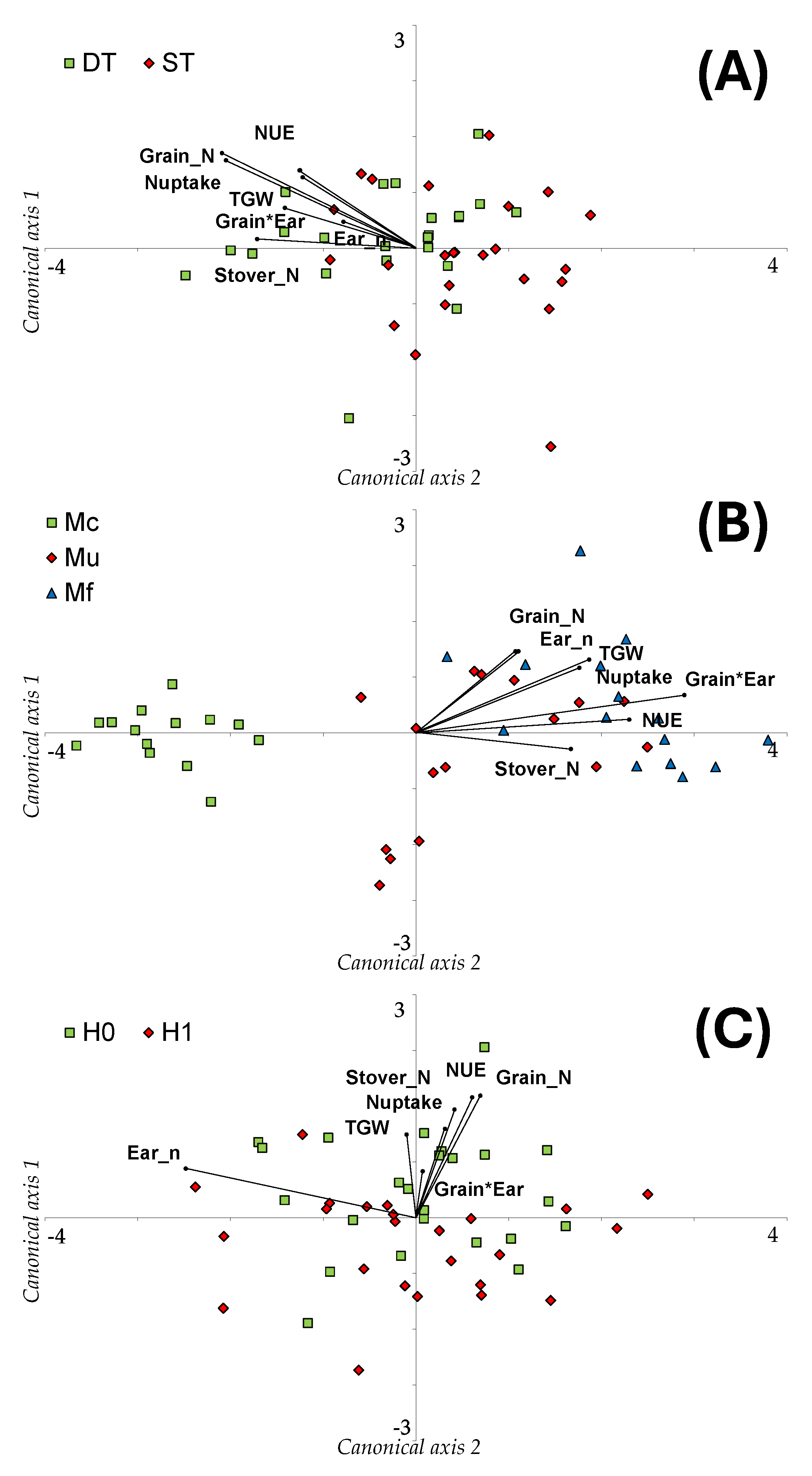

3.17. Canonical Discriminant Analysis (CDA) for Yield Characteristics of Maize

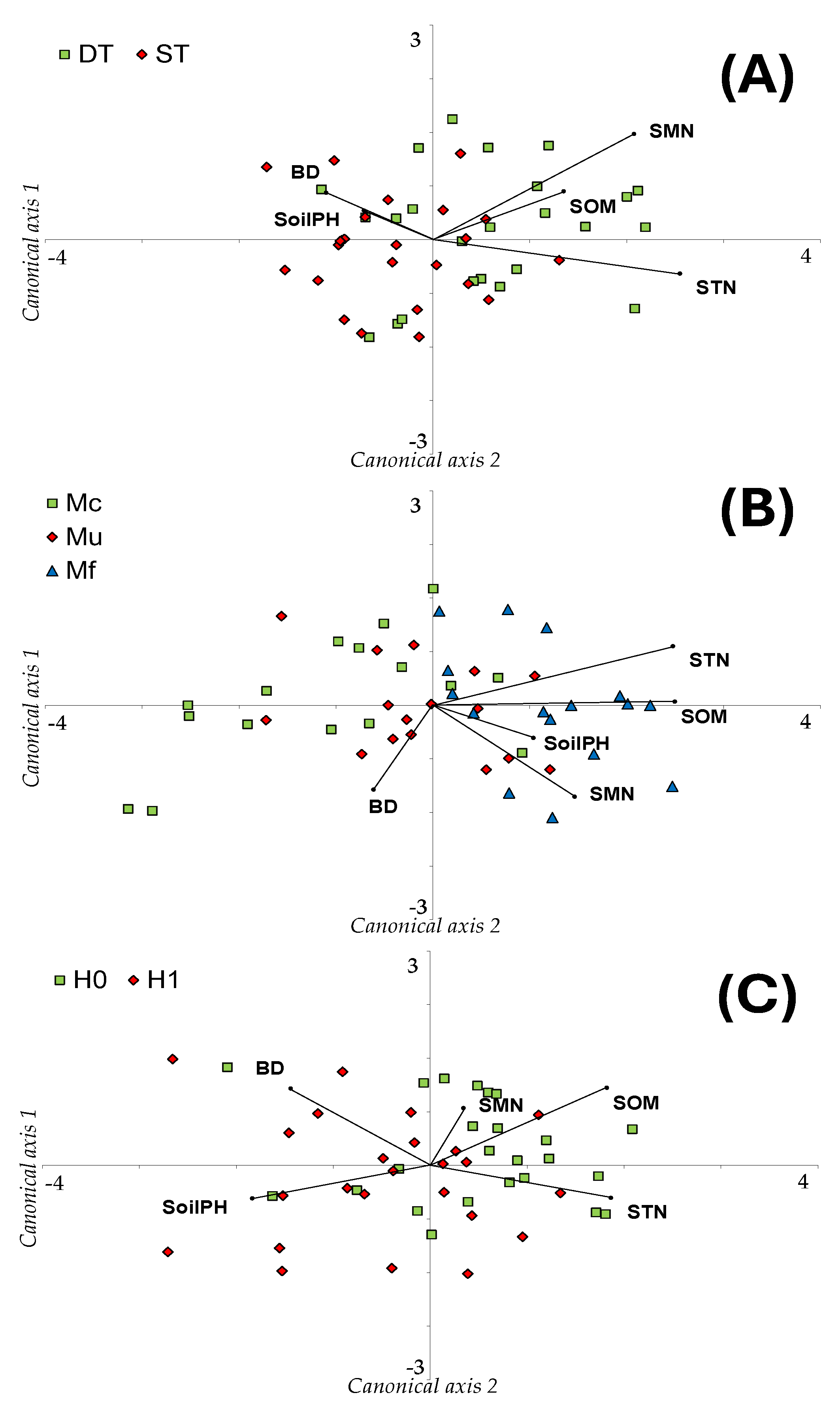

3.18. Canonical Discriminant Analysis (CDA) for Post-Harvest Soil Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salman, M.; Inamullah; Jamal, A.; Mihoub, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Radicetti, E.; Ahmad, I.; Naeem, A.; Ullah, J.; Pampana, S. Composting sugarcane filter mud with different sources differently benefits sweet maize. Agronomy 2023, 13, 748. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, J.; Shah, S.; Mihoub, A.; Jamal, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Székely, Á.; Radicetti, E.; Salman, M.; Caballero-Calvo, A. Assessing the effect of combining phosphorus fertilizers with crop residues on maize (Zea Mays L.) productivity and financial benefits. Gesunde Pflanz. 2023, 75, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Munsif, F.; Jamal, A.; Mihoub, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Fawad, M.; Ahmad, I.; Ali, A. Morpho-physiological attributes of Different maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes under varying salt stress conditions. Gesunde Pflanz. 2022, 74, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ul Shahid, Z.; Ali, M.; Shahzad, K.; Danish, S.; Alharbi, S.A.; Ansari, M.J. Enhancing maize productivity by mitigating alkaline soil challenges through acidified biochar and wastewater irrigation. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 20800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancinelli, R.; Allam, M.; Petroselli, V.; Atait, M.; Jasarevic, M.; Catalani, A.; Marinari, S.; Radicetti, E.; Jamal, A.; Abideen, Z. Durum Wheat Production as Affected by Soil Tillage and Fertilization Management in a Mediterranean Environment. Agriculture 2023, 13, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanick, B.; Kumar, M.; Naik, B.M.; Kumar, M.; Singh, S.K.; Maitra, S.; Naik, B.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T. Long-term conservation tillage and precision nutrient management in maize–wheat cropping system: effect on soil properties, crop production, and economics. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Gao, Z.; Liao, K.; Zhu, Q.; Zhu, J. Impact of conservation tillage on the distribution of soil nutrients with depth. Soil Tillage Res 2023, 225, 105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Yakov, K.; Liu, S.; Li, F.-M. Effects of tillage on soil organic carbon and crop yield under straw return. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 354, 108543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tater, A.; Vashisht, B. Long-Term Effect of Crop Establishment Methods and Tillage Practices on Soil Physical Properties in Rice-Wheat System. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürsoy, S. Soil compaction due to increased machinery intensity in agricultural production: its main causes, effects and management. Technology in agriculture 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, D.; Mishra, A.K.; Rani, P.; Kalonia, N.; Chaudhary, A.; Sharma, S. Soil Management in Sustainable Agriculture: Principles and Techniques. In Technological Approaches for Climate Smart Agriculture; Springer: 2024; pp. 41–77.

- Shi, X.; Li, C.; Li, P.; Zong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Gao, Z.; Hao, X.; Wang, J.; Lam, S.K. Deep plowing increases soil water storage and wheat yield in a semiarid region of Loess Plateau in China: A simulation study. Field Crops Res. 2024, 308, 109299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; You, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Liao, Y.; Li, S. Soil failure characteristics and loosening effectivity of compacted grassland by subsoilers with different plough points. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 237, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Wang, Z.; Tong, J.; Shang, Z.; Deng, A.; Song, Z.; Zhang, W. Strip tillage promotes crop yield in comparison with no tillage based on a meta-analysis. Soil Tillage Res 2024, 240, 106085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Mihoub, A.; Hopkins, B.G.; Ahmad, I.; Naeem, A. Integrated use of phosphorus fertilizer and farmyard manure improves wheat productivity by improving soil quality and P availability in calcareous soil under subhumid conditions. Front. Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1034421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihoub, A.; Naeem, A.; Amin, A.E.-E.A.Z.; Jamal, A.; Saeed, M.F. Pigeon manure tea improves phosphorus availability and wheat growth through decreasing p adsorption in a calcareous sandy soil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2022, 53, 2596–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Amanullah; Jamal, A.; Mihoub, A.; Farooq, O.; Farhan Saeed, M.; Roberto, M.; Radicetti, E.; Zia, A.; Azam, M. Partial substitution of chemical fertilizers with organic supplements increased wheat productivity and profitability under limited and assured irrigation regimes. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1754. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Freitas, J.; Fernandes, I.; Silva, P. Microalgae as biofertilizers: a sustainable way to improve soil fertility and plant growth. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.H.; Cappai, G.; Chung, J.-W.; Jeong, C.; Kulli, B.; Marchelli, F.; Ro, K.S.; Román, S. Research Needs and Pathways to Advance Hydrothermal Carbonization Technology. Agronomy 2024, 14, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Sultana, A.I.; Chambers, C.; Saha, S.; Saha, N.; Kirtania, K.; Reza, M.T. Recent progress on emerging applications of hydrochar. Energies 2022, 15, 9340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavali, M.; Junior, N.L.; de Sena, J.D.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Soccol, C.R.; Belli Filho, P.; Bayard, R.; Benbelkacem, H.; de Castilhos Junior, A.B. A review on hydrothermal carbonization of potential biomass wastes, characterization and environmental applications of hydrochar, and biorefinery perspectives of the process. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Jasrotia, K.; Singh, N.; Ghosh, P.; Srivastava, S.; Sharma, N.R.; Singh, J.; Kanwar, R.; Kumar, A. A comprehensive review on hydrothermal carbonization of biomass and its applications. Chemistry Africa 2020, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Z.; Chen, M.; Ma, L.; Du, G.; Zhu, M. A novel activation-hydrochar via hydrothermal carbonization and KOH activation of sewage sludge and coconut shell for biomass wastes: Preparation, characterization and adsorption properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 593, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, L.A. Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils; US Government Printing Office: 1954.

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2 chemical and microbiological properties 1982, 9, 539–579. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanpour, P. Use of ammonium bicarbonate DTPA soil test to evaluate elemental availability and toxicity. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 1985, 16, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, D.R.; Nelson, D.W. Nitrogen—inorganic forms. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2 chemical and microbiological properties 1982, 9, 643–698. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.E.G.; da Costa Assunção, F.P.; Teribele, T.; Pereira, L.M.; de Castro, D.A.R.; Santo, M.C.; da Costa, C.E.F.; Shultze, M.; Hofmann, T.; Machado, N.T. Characterization of bio-adsorbents produced by hydrothermal carbonization of corn stover: Application on the adsorption of acetic acid from aqueous solutions. Energies 2021, 14, 8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.F.; Jamal, A.; Muhammad, D.; Shah, G.M.; Bakhat, H.F.; Ahmad, I.; Ali, S.; Ihsan, F.; Wang, J. Optimizing phosphorus levels in wheat grown in a calcareous soil with the use of adsorption isotherm models. J Soil Sci Plant Nut 2021, 21, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlorophyllsandcarotenoids, L.K. Pigmentsof photosyntheticbiomembranes. MethodEnzymol 1987, 148, 350G382. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M. Soil chemical analysis.,(Constable & Co Ltd: London). 1958.

- Gheith, E.; El-Badry, O.Z.; Lamlom, S.F.; Ali, H.M.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Ghareeb, R.Y.; El-Sheikh, M.H.; Jebril, J.; Abdelsalam, N.R.; Kandil, E.E. Maize (Zea mays L.) productivity and nitrogen use efficiency in response to nitrogen application levels and time. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 941343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, K.; Dawar, A.; Tariq, M.; Mian, I.A.; Muhammad, A.; Farid, L.; Khan, S.; Khan, K.; Fahad, S.; Danish, S. Enhancing nitrogen use efficiency and yield of maize (Zea mays L.) through Ammonia volatilization mitigation and nitrogen management approaches. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Khan, A. Phenology and Maize Crop Stand in Response to Mulching and Nitrogen Management. Sarhad J. Agric. 2017, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavya, K.; Geetha, A. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Adv. Agric. Sci 2021, 61, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, B.; Jan, M.T.; Muhammad, Z.; Khan, A.A.; Anwar, S. 07. Phenological traits of Maize influenced by integrated management of compost and fertilizer Nitrogen. Pure appl. biol. 2021, 5, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanullah; Khan, I.; Jan, A.; Jan, M.T.; Khalil, S.K.; Shah, Z.; Afzal, M. Compost and nitrogen management influence productivity of spring maize (Zea mays L.) under deep and conventional tillage systems in Semi-arid regions. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2015, 46, 1566–1578. [CrossRef]

- Battipaglia, G.; Niccoli, F.; Kabala, J.P.; Marzaioli, R.; Di Santo, T.; Strumia, S.; Castaldi, S.; Petriccione, M.; Zaccariello, L.; Battaglia, D. Hydrochar Application Improves Growth and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency of Populus alba, Especially during Hot Season. Forests 2023, 14, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, S.; Derevenets-Shevchenko, K.; Desyatnyk, L.; Shevchenko, M.; Sologub, I.; Shevchenko, O. Tillage effects on soil physical properties and maize phenology. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 81, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even, R.J.; Cotrufo, M.F. The ability of soils to aggregate, more than the state of aggregation, promotes protected soil organic matter formation. Geoderma 2024, 442, 116760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; Ding, P.; Ren, A.; Sun, M.; Gao, Z. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer on photosynthetic characteristics and yield. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, W.; Yang, G.; Irfan, M. Crop nitrogen (N) utilization mechanism and strategies to improve N use efficiency. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2023, 45, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Struik, P.C.; Gu, J.; van der Putten, P.E.; Wang, Z.; Yin, X.; Yang, J. Enhancing leaf photosynthesis from altered chlorophyll content requires optimal partitioning of nitrogen. Crop Environ. 2023, 2, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, B.; Zhou, W.; Zhong, X.; Fu, C.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, X. Effect of nitrogen application levels on photosynthetic nitrogen distribution and use efficiency in soybean seedling leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 287, 154051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Tan, S.; Yang, Q.; Chen, S.; Qi, C.; Liu, X.; Liang, J.; Wang, H. Nitrogen Application Alleviates Impairments for Jatropha curcas L. Seedling Growth under Salinity Stress by Regulating Photosynthesis and Antioxidant Enzyme Activity. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yang, X.; Zhao, P.; Li, Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y. From biomass to hydrochar: Evolution on elemental composition, morphology, and chemical structure. J. Energy Inst. 2022, 101, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Briceño, C.; Pozarlik, A.; Bramer, E.; Niedzwiecki, L.; Pawlak-Kruczek, H.; Brem, G. Hydrothermal carbonization of wet biomass from nitrogen and phosphorus approach: A review. Renew Energ. 2021, 171, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, M.; Dragičević, V.; Mladenović Drinić, S.; Vukadinović, J.; Kresović, B.; Tabaković, M.; Brankov, M. The contribution of soil tillage and nitrogen rate to the quality of maize grain. Agronomy 2020, 10, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Fu, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, P.; He, S.; Shao, H.; Ni, Z.; Zhang, X. Effects of irrigation and nitrogen on chlorophyll content, dry matter and nitrogen accumulation in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, R.; Samdeliri, M.; Mirkalaei, A.M. The effect of different tillage methods and nitrogen chemical fertilizer on quantitative and qualitative characteristics of corn. Int J Anal Chem 2022, 2022, 7550079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Islam, U.; Jiang, F. The effect of deep-tillage depths on crop yield: A global meta-analysis. Plant, Soil Envir 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Cao, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Meng, D.; Cao, P.; Duan, S.; Zhang, M. Mechanism of intermittent deep tillage and different depths improving crop growth from the perspective of rhizosphere soil nutrients, root system architectures, bacterial communities, and functional profiles. Front. microbiol. 2022, 12, 759374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Liu, X.; Shi, Q.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, J.; Cui, B.; Hou, J.; Wei, Z.; Hossain, M.A. Biochar amendment alters root morphology of maize plant: Its implications in enhancing nutrient uptake and shoot growth under reduced irrigation regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1122742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccini, M.; Ceccarini, L.; Antichi, D.; Seggiani, M.; Tavarini, S.; Hernandez Latorre, M.; Vitolo, S. Hydrothermal carbonization of municipal woody and herbaceous prunings: hydrochar valorisation as soil amendment and growth medium for horticulture. Sustainability 2018, 10, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, O.; Taskin, M.; Kaya, E.; Atakol, O.; Emir, E.; Inal, A.; Gunes, A. Effect of acid modification of biochar on nutrient availability and maize growth in a calcareous soil. Soil Use Manag. 2017, 33, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, X.; Liu, E.; Sun, S.; Ren, X.; Jia, Z.; Wei, T.; Zhang, P. Continuous ridge-furrow film mulching enhances maize root growth and crop yield by improving soil aggregates characteristics in a semiarid area of China: An eight-year field experiment. Plant and Soil 2024, 499, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Zhao, W.; Ju, C.; Peng, K.; Yuan, M.; Tan, Q.; He, R.; Huang, M. Effects of Different Tillage Depths on Soil Physical Properties and the Growth and Yield of Tobacco in the Mountainous Chongqing Region of China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmal, M.; Shah, A.; Zaman, R.; Afzal, M.; Amin, N. Carryover response of tillage depth, legume residue and nitrogen-rates on maize yield and yield contributing traits. Int. J. Agric. Biol 2015, 17, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Ping, J.; Yan, X.; Liu, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, L.; Ren, J. Effect of subsoil tillage depth on nutrient accumulation, root distribution, and grain yield in spring maize. The Crop J. 2014, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Mishra, A.K.; Singh, B.; Singh, R.P.; Patra, D.D. Tillage effects on crop yield and physicochemical properties of sodic soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, A.; Rachoń, L. Effect of tillage systems on the yield and quality of winter wheat grain and soil properties. Agriculture 2020, 10, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Zhang, P.; Yu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Chen, B.; Tan, H.; Han, H.; Hou, J.; Zhao, F. Fresh maize yield in response to nitrogen application rates and characteristics of nitrogen-efficient varieties. J. Integr. Agric. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalovic, I.; Prasad, P.V.; Akhtar, K.; Paunović, A.; Riaz, M.; Dugalic, M.; Katanski, S.; Zaheer, S. Nitrogen Fertilization and Cultivar Interactions Determine Maize Yield and Grain Mineral Composition in Calcareous Soil under Semiarid Conditions. Plants 2024, 13, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Limon, M.S.H.; Romić, M.; Islam, M.A. Hydrochar-based soil amendments for agriculture: a review of recent progress. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soothar, M.K.; Mounkaila Hamani, A.K.; Kumar Sootahar, M.; Sun, J.; Yang, G.; Bhatti, S.M.; Traore, A. Assessment of acidic biochar on the growth, physiology and nutrients uptake of maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings under salinity stress. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Wang, B.; Feng, Y.; Fu, H.; Feng, Y.; Xie, H.; Xue, L. Livestock manure-derived hydrochar improved rice paddy soil nutrients as a cleaner soil conditioner in contrast to raw material. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 372, 133798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Zhu, C.; Jiang, G.; Yang, J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Liu, F.; Jie, X.; Liu, S. Differentiation in Nitrogen Transformations and Crop Yield as Affected by Tillage Modes in a Fluvo-Aquic Soil. Plants 2023, 12, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-Q.; Yu, X.-F.; Gao, J.-L.; Ma, D.-L.; Liu, H.-Y.; Hu, S.-P. Regulation of tillage on grain matter accumulation in maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1373624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, H.; Hashemi, M.; Tang, Y.; Xing, B. Hydrochars as slow-release phosphorus fertilizers for enhancing corn and soybean growth in an agricultural soil. Carbon Res. 2024, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.; Hussain, M.B.; Haider, G.; Haq, T.U.; Zahir, Z.A.; Danish, S.; Paray, B.A.; Kammann, C. Acidified manure and nitrogen-enriched biochar showed short-term agronomic benefits on cotton–wheat cropping systems under alkaline arid field conditions. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 22504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yin, D.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Li, Z. Effects of different amounts of biochar applied on soil nutrient, soil enzyme activity and maize yield. J. Northeast Agric Sci. 2019, 44, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, R.P.; Corinto, L.M.; Peixoto, D.S.; De Figueiredo, T.; Silveira, G.C.D.; Peche, P.M.; Pio, L.A.S.; Pagliari, P.H.; Curi, N.; Silva, B.M. Deep tillage strategies in perennial crop installation: Structural changes in contrasting soil classes. Plants 2022, 11, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjønning, P.; Thomsen, I.K. Shallow tillage effects on soil properties for temperate-region hard-setting soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2013, 132, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Han, H.; Ning, T.; Li, Z.; Lal, R. Long-term effects of tillage and straw management on soil organic carbon, crop yield, and yield stability in a wheat-maize system. Field Crops Res. 2019, 233, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guan, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X. Intermittent deep tillage on improving soil physical properties and crop performance in an intensive cropping system. Agronomy 2022, 12, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran. Integration of organic, inorganic and bio fertilizer, improve maize-wheat system productivity and soil nutrients. J. Plant Nutr. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, H.; Guo, J. Effects of long-term organic–inorganic nitrogen application on maize yield and nitrogen-containing gas emission. Agronomy 2023, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronti, S.; Alberti, G.; Camin, F.; Criscuoli, I.; Genesio, L.; Mass, R.; Vaccari, F.P.; Ziller, L.; Miglietta, F. Hydrochar enhances growth of poplar for bioenergy while marginally contributing to direct soil carbon sequestration. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 1618–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, M.; Giani, L. An investigation of the effects of hydrochar application rate on soil amelioration and plant growth in three diverse soils. Biochar 2021, 3, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, H.M.R.; Ali, M.; Kanwal, N.; Ahmad, I.; Jamal, A.; Qamar, R.; Zakir, A.; Andaleeb, H.; Jabeen, R.; Radicetti, E. Nitrogen mineralization in texturally contrasting soils subjected to different organic amendments under semi-arid climates. Land 2023, 12, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Liao, F.; Verma, K.K.; Sarwar, M.A.; Mahmood, A.; Chen, Z.-L.; Li, Q.; Zeng, X.-P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.-R. Fate of nitrogen in agriculture and environment: agronomic, eco-physiological and molecular approaches to improve nitrogen use efficiency. Biol Res. 2020, 53, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Shan, S.; Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, X.; Ma, Q.; Yrjälä, K.; Zheng, H.; Cao, Y. The comparison of dissolved organic matter in hydrochars and biochars from pig manure. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregolente, L.G.; dos Santos, J.V.; Mazzati, F.S.; Miguel, T.B.; de, C. Miguel, E.; Moreira, A.B.; Ferreira, O.P.; Bisinoti, M.C. Hydrochar from sugarcane industry by-products: assessment of its potential use as a soil conditioner by germination and growth of maize. Chem. biol. technol. agric. 2021, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunshirn, P.; Wenzel, W.W.; Pfeifer, C. Pore characteristics of hydrochars and their role as a vector for soil bacteria: A critical review of engineering options. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol 2022, 52, 4147–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, M.M.; Choi, Y.U.; Foley, D.G.; Gobel, M.S.; Sprague, N.C.; Guevara-Ocana, S.; Kuleshov, Y.A.; Stwalley III, R.M. Reducing Soil Compaction from Equipment to Enhance Agricultural Sustainability. In Sustainable Crop Production-Recent Advances; IntechOpen: 2022.

- Torabian, S.; Farhangi-Abriz, S.; Alaee, T. Hydrochar mitigates salt toxicity and oxidative stress in maize plants. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci 2021, 67, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DtoE | DtoT | DtoS | DtoPM | |||||

| ------------------------------------ days ---------------------------- -------- | ||||||||

| Tillage Practices | ||||||||

| ST | 7.7 (±0.14) | a | 52.8 (±0.34) | a | 63.2 (±0.31) | a | 93.4 (±0.40) | b |

| DT | 7.4 (±0.17) | a | 53.4 (±0.28) | a | 63.3 (±0.26) | a | 94.3 (±0.36) | a |

| Nitrogen management | ||||||||

| MC | 7.9 (±0.22) | a | 51.9 (±0.30) | b | 62.0 (±0.18) | b | 92.3 (±0.42) | b |

| MU | 7.4 (±0.18) | a | 53.9 (±0.35) | a | 64.3 (±0.35) | a | 95.0 (±0.34) | a |

| MF | 7.4 (±0.15) | a | 53.4 (±0.30) | a | 63.4 (±0.20) | a | 94.3 (±0.40) | a |

| Hydrochar | ||||||||

| H0 | 7.4 (±0.16) | b | 53.5 (±0.35) | a | 63.7 (±0.30) | a | 94.4 (±0.42) | a |

| H1 | 7.8 (±0.15) | a | 52.7 (±0.25) | b | 62.8 (±0.25) | b | 93.3 (±0.33) | b |

| Plant height (cm) |

Biological yield (t ha-1 of DM) |

Harvest index (%) |

||||

| Tillage Practices | ||||||

| ST | 181.7 (±3.47) | b | 8.82 (±0.94) | b | 40.0 (±0.78) | a |

| DT | 195.1 (±3.75) | a | 9.59 (±2.16) | a | 39.7 (±0.90) | a |

| Nitrogen management | ||||||

| MC | 175.1 (±3.69) | b | 8.64 (±1.14) | b | 37.1 (±1.10) | b |

| MU | 193.7 (±3.56) | a | 9.26 (±1.74) | a | 41.1 (±0.76) | a |

| MF | 196.3 (±5.00) | a | 9.72 (±2.73) | a | 41.3 (±0.86) | a |

| Hydrochar | ||||||

| H0 | 192.5 (±3.81) | a | 9.45 (±1.98) | a | 40.0 (±0.93) | a |

| H1 | 184.1 (±3.76) | b | 8.96 (±1.56) | b | 39.7 (±0.74) | a |

| Grain yield (t ha-1 of DM) |

Ear (n. m-2) |

Ear length (cm) |

Grains (n. ear-1) |

TGW (g) |

GrainN (g kg-1) |

StoverN (g kg-1) |

||||||||

| Tillage Practices | ||||||||||||||

| ST | 3.53 (±0.79) | b | 7.3 (±0.13) | a | 16.1 (±0.24) | b | 307.8 (±5.13) | b | 217.0 (±1.57) | b | 12.3 (±0.45) | b | 3.6 (±0.24) | b |

| DT | 3.80 (±1.09) | a | 7.5 (±0.12) | a | 17.0 (±0.33) | a | 324.6 (±5.36) | a | 221.5 (±1.03) | a | 14.1 (±0.42) | a | 4.3 (±0.20) | a |

| Nitrogen management | ||||||||||||||

| MC | 3.20 (±0.81) | b | 7.1 (±0.12) | b | 15.3 (±0.24) | c | 284.6 (±2.61) | c | 214.6 (±1.08) | b | 12.0 (±0.55) | c | 3.1 (±0.21) | b |

| MU | 3.80 (±0.79) | a | 7.4 (±0.17) | ab | 16.6 (±0.26) | b | 321.7 (±3.95) | b | 218.4 (±1.73) | ab | 13.5 (±0.54) | b | 4.3 (±0.23) | a |

| MF | 4.00 (±0.97) | a | 7.6 (±0.13) | a | 17.8 (±0.32) | a | 342.2 (±2.24) | a | 224.8 (±1.19) | a | 14.1 (±0.57) | a | 4.4 (±0.28) | a |

| Hydrochar | ||||||||||||||

| H0 | 3.76 (±0.99) | b | 7.4 (±0.12) | a | 17.1 (±0.28) | a | 319.7 (±4.93) | a | 221.0 (±1.18) | a | 13.9 (±0.46) | a | 4.2 (±0.24) | a |

| H1 | 3.96 (±0.94) | a | 7.3 (±0.13) | a | 16.0 (±0.30) | b | 312.6 (±5.99) | b | 217.5 (±1.53) | b | 12.6 (±0.46) | b | 3.6 (±0.21) | b |

| Nitrogen uptake | NUE | |||

| ----------- kg of N ha-1 ------------ | ||||

| Tillage Practices | ||||

| ST | 36.34 (±1.79) | b | 29.38 (±0.66) | b |

| DT | 45.45 (±2.40) | a | 31.69 (±0.91) | a |

| Nitrogen management | ||||

| MC | 32.32 (±1.97) | c | 26.64 (±0.67) | b |

| MU | 42.96 (±2.29) | b | 31.64 (±0.66) | a |

| MF | 47.39 (±2.77) | a | 33.31 (±0.81) | a |

| Hydrochar | ||||

| H0 | 44.14 (±2.38) | a | 31.46 (±0.83) | a |

| H1 | 37.64 (±2.05) | b | 29.61 (±0.78) | b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).