2. Experimental

Commercial powder (NMC622, Umicore) with an average size 5.07±0.97 m, determined by SEM, was thoroughly mixed with conductive carbon black (EQ-lib-Super65, MTI) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF; Mv = 600,000, MTI) binder in N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP; 99%, Sigma-Aldrich), in a weight ratio of 8:1:1, respectively. This mixture was then uniformly coated on aluminum foil using a doctor blade of 180 m thickness. Subsequently, the coated foil was dried under vacuum at 80 ∘C for 12 h. Afterward, the dried electrode was punched into discs with a diameter of 14 mm. A 16 mm in diameter lithium chip was used as the reference and counter electrode. Each cell is configured in a CR2032 coin cell with a working electrode, a separator (3501, Celgard®, 25m), and a lithium electrode. A 50 l of electrolyte containing 1 M lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6; 99,99%, Sigma-Aldrich) in ethylene carbonate (EC; 98%, Sigma-Aldrich) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC; 99%, Sigma-Aldrich) in a 1:1 volume ratio, respectively, was subsequently introduced into the separator. All cell fabrication procedures were performed in an argon-filled glovebox. The cells manufactured were aged at 25∘C for 18 h prior to electrochemical testing.

The amount of active material in a cell was approximately 3 mg, and the capacity value for the calculation of the C rate was assumed to be 180 mAhg

−1 [

8,

9]. The coin cells were loaded into a Peltier chamber (Memmert IPP30plus, Germany) set at 30∘C using a 10-coin cell holder (Neoscience, Korea). The temperature variation of the cell during battery testing was continuously measured using K-type thermocouples attached directly at the top of the cells. Electrochemical measurements were made using Biologic software (VSP300, France) using the dedicated EC-Lab software

®.

For clarity, large data in Figures were presented by utilizing data distance threshold skip method of OriginLab® 2023 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Impedance analysis and simulation were made using ZView® (Scribner Ass. Inc., USA) and Python codes updated from one provided by Prof. Miran Gaberšček, National Institute of Chemistry, Ljubljana, Slovenia, in 2023, June.

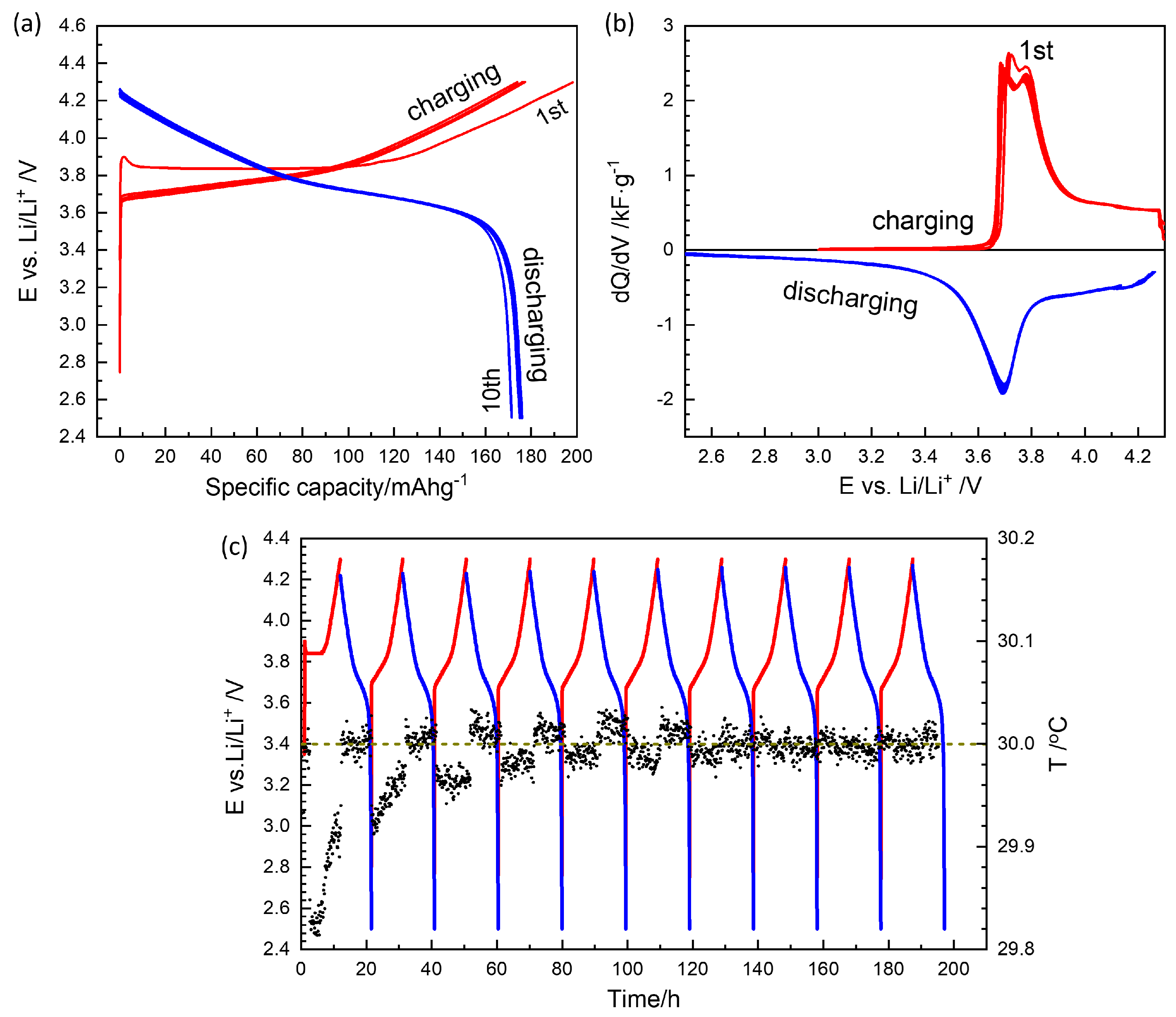

5. GITT for Equilibrium OCVs

GITT for a charging and discharging cycle in

Figure 2 took more than two months, and the degradation or time-dependent change is likely in the cell components: electrolyte, lithium reference electrode as well as the NMC622 electrode. It is shown that the capacity fades from 180 mAhg

−1 upon charging to 150 mAhg

−1 when discharging. Similar results were obtained from two different cells.

In most studies GITT relaxation periods appear to be fixed by the automated sequences as 40 min[

12,

13], 135 min [

14], 1 h [

11,

15], 2 h [

16,

17], 3 h [

13], 4 h [

18,

19], 5 h [

20,

21], 6 h [

22], 10 h [

23] etc. It can be more than a day [

24].

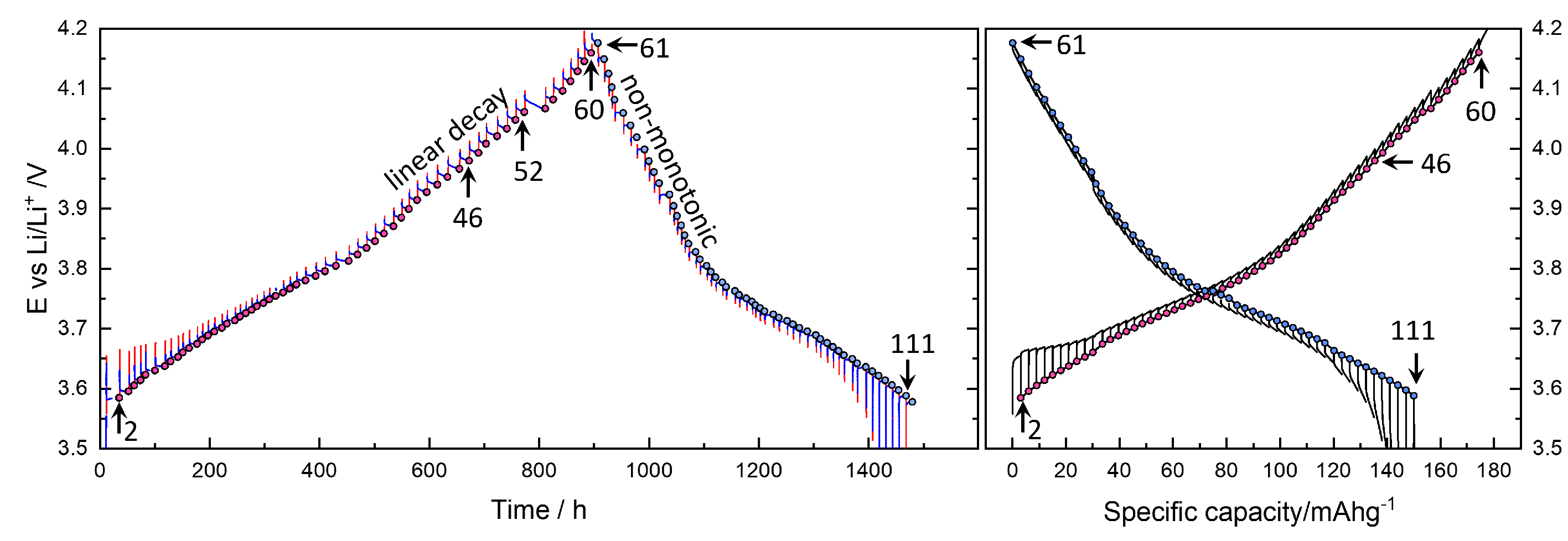

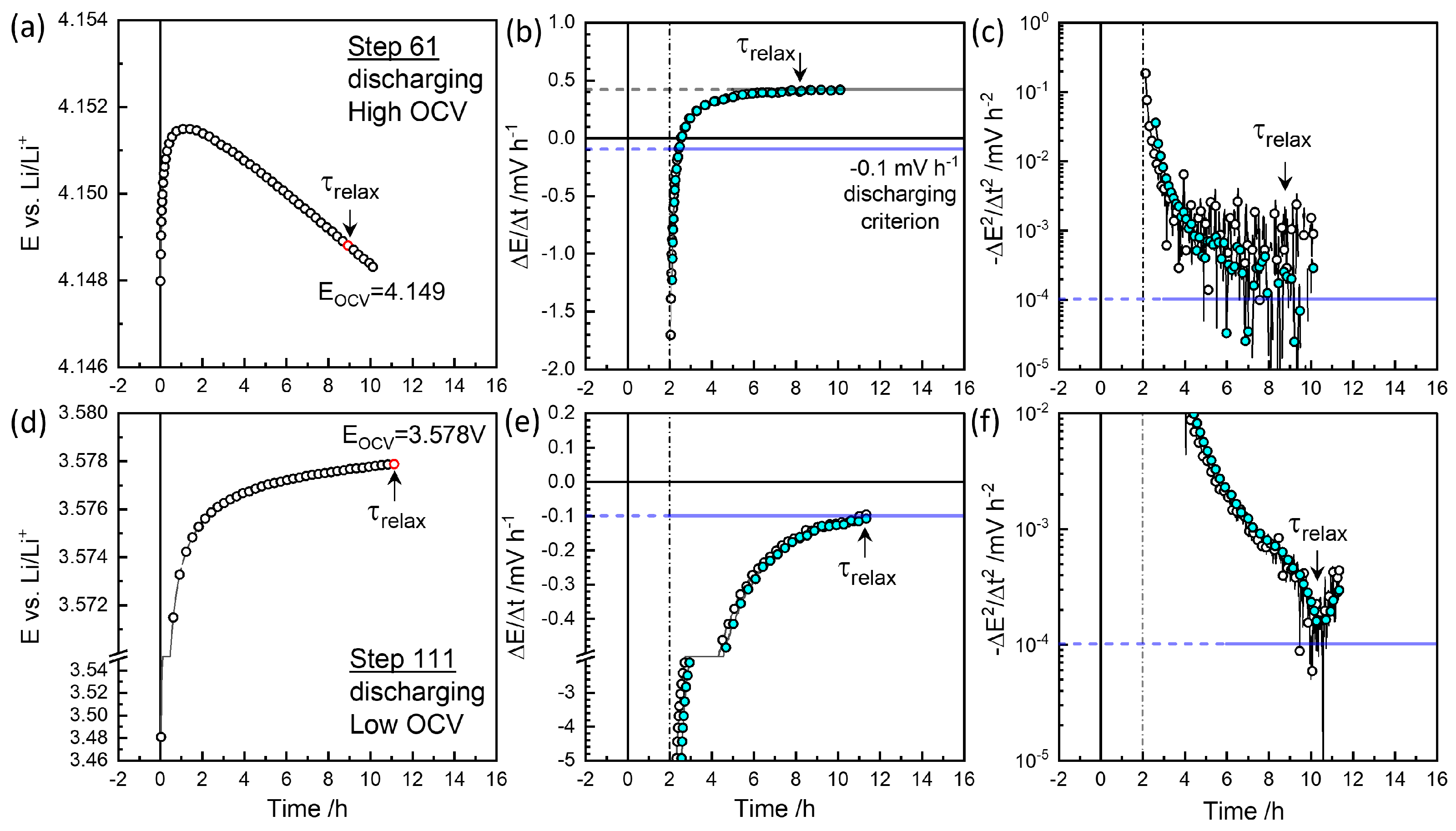

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show relaxation behaviors of the selected steps. The raw data were measured for every minute. In plots the `Smart Skip’ provided by OrginLab

® was utilized for clarity. Slow relaxation is perceptive only over a long time. A criterion such as

mV / h [

25] is needed. The cutoff control

available in EC-Lab

® for the automated procedure did not work for a slow relaxation as

mV h

−1 due to noise. The relaxation time

to this cutoff was evaluated as

mV h

−1 for the

mV h

−1 criterion for a possible operand implementation, as the two-hour difference gives a significant trend over fluctuation.

Figure 3(a) and (b) show the example in charging Step 2 that reaches the cutoff criterion of

=0.1 mV h

−1 around 9 h. Estimation starts after 2 h. The colored symbols are smoothed for clarity. A slower decrease in voltage was monitored until 15 h.

Figure 3(c) shows the change in the decay rates,

becomes

mV h

−12 around 13 h. The equilibrium OCV,

, was taken at the cut-off as 3.595 V from the cut-off criterion of

=0.1 mV h

−1 at 9 h.

Figure 4(d) and (e) show the discharge step 111, reaching the criterion in the opposite direction -0.1 mV h

−1 at 11 h for

=3.578 V. As shown in

in

Figure 3(f), the change in the decay rate decreased and increased again near the end of the monitoring time.

At high OCV above 3.8 V, as shown in

Figure 3(d) and (e), the decay rate does not decrease to reach the criterion of 0.1 mV h

−1, but decays linearly at 0.56 mV h

−1 at near 10 h. Therefore, a second criterion

= 10

−4mV h

−2 is applied for

=4.188 V.

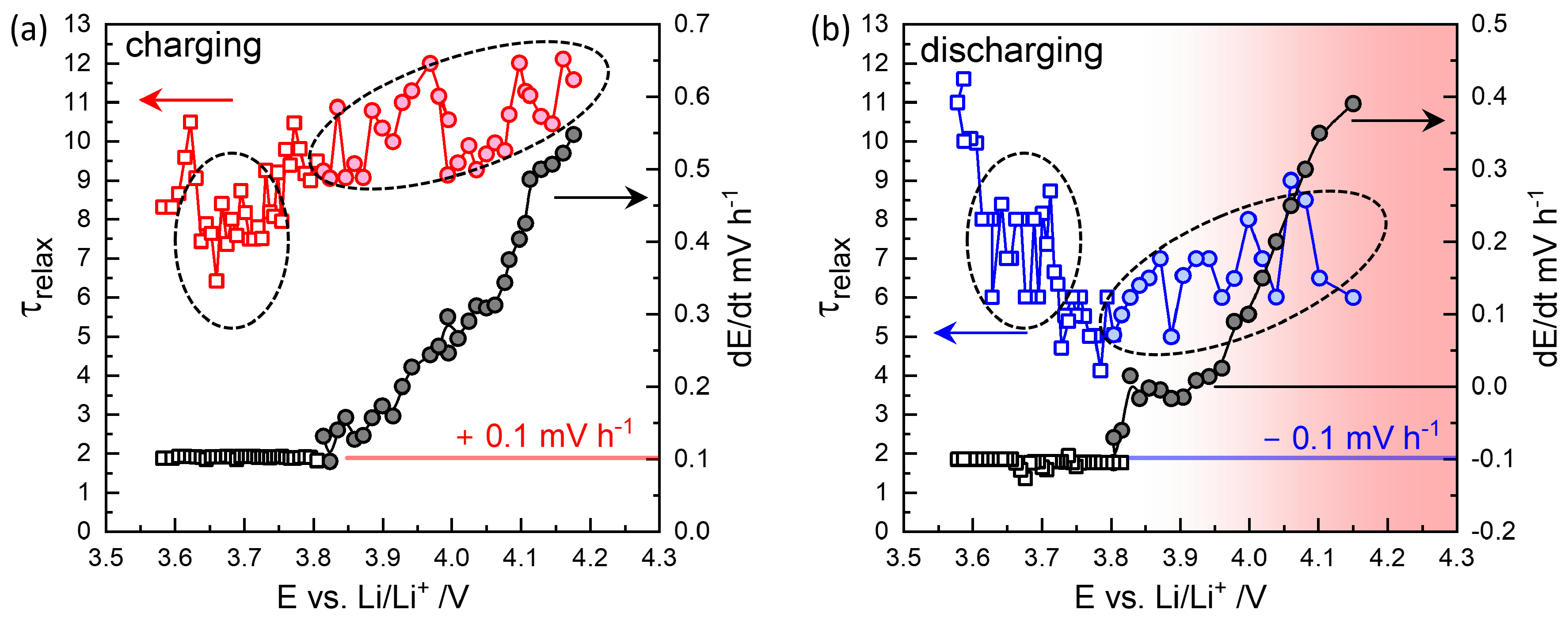

Figure 5(a) shows

values roughly increase to 9-12 h, and decay rates increase with increasing OCV to 0.56 mV/h. As shown in Step 52 in

Figure 2, the decrease in voltage continues indefinitely.

More peculiar is that upon discharge, as shown in

Figure 4(a,b), the relaxation becomes nonmonotonic, showing overshooting. The long-time relaxation is thus similar to the charging steps in

Figure 3(d).

values vary between 5-8 h, and the decay rates appear to be shifted downward from those in charging steps. The discharge titration capacity is reduced to 150 mAhg

−1. Degradation may have occurred while staying at high OCV for more than 10 days during charging steps. The characteristic relaxation behaviors were confirmed in three different cells and should be related to the kinetics of NMC622. Recently, Kang et al.[

20,

26] suggested an improved kinetic analysis method from the relaxation curves exploiting long-time relaxation for bulk diffusion.

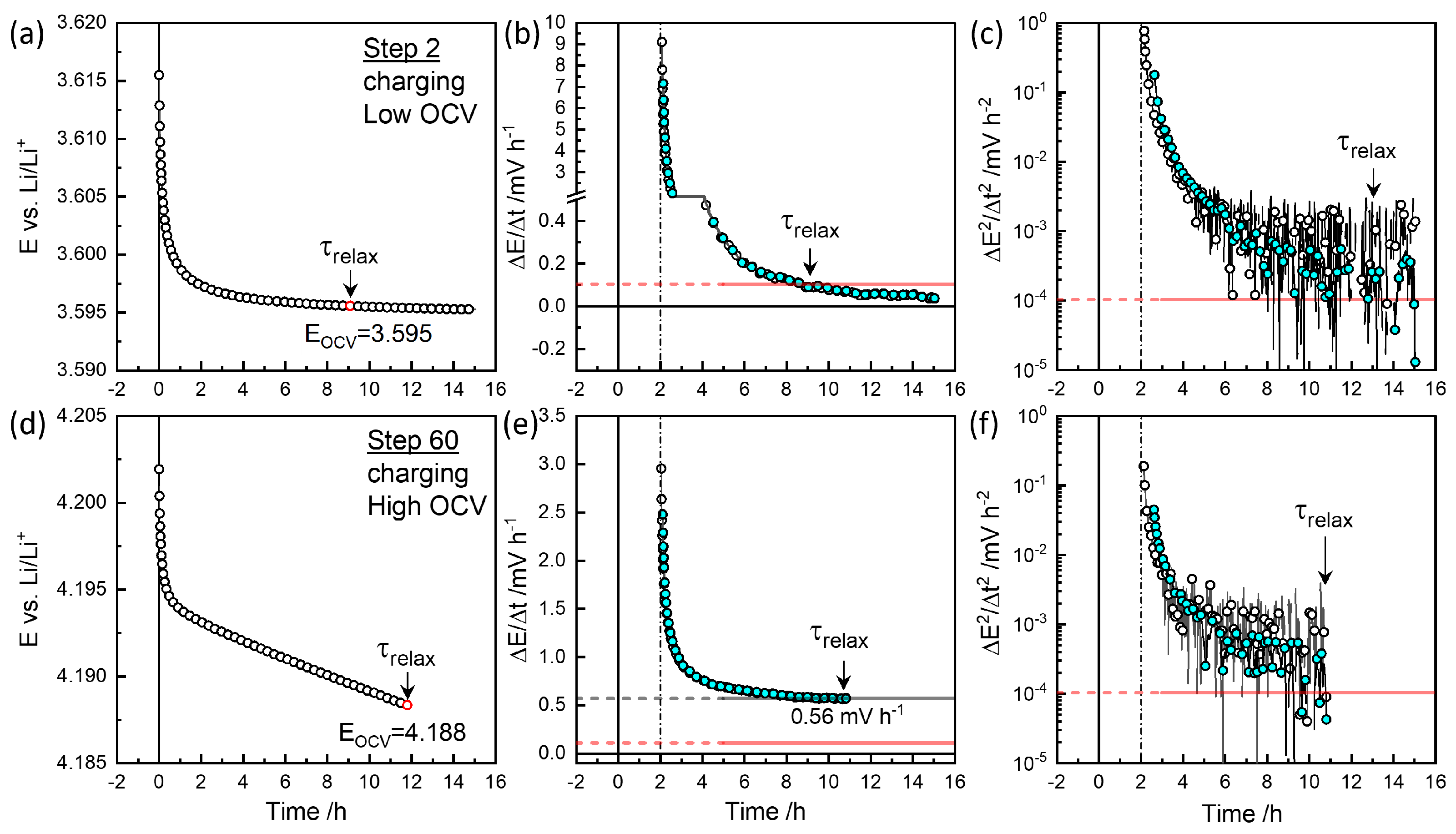

6. GITT for Chemical Diffusivity

In the original GITT, chemical diffusivity is estimated by the transient voltage where the short-time solution of the diffusion equation can be applied [

15,

27,

28]. The chemical diffusivity,

according to Weppner and Huggins [

1,

2,

12,

14,

15],

where

(=600 s),

, and

are the transient change due to diffusion without `

’ including ohmic and charge transfer polarizations, and the difference in OCVs, as indicated for Step 46, in

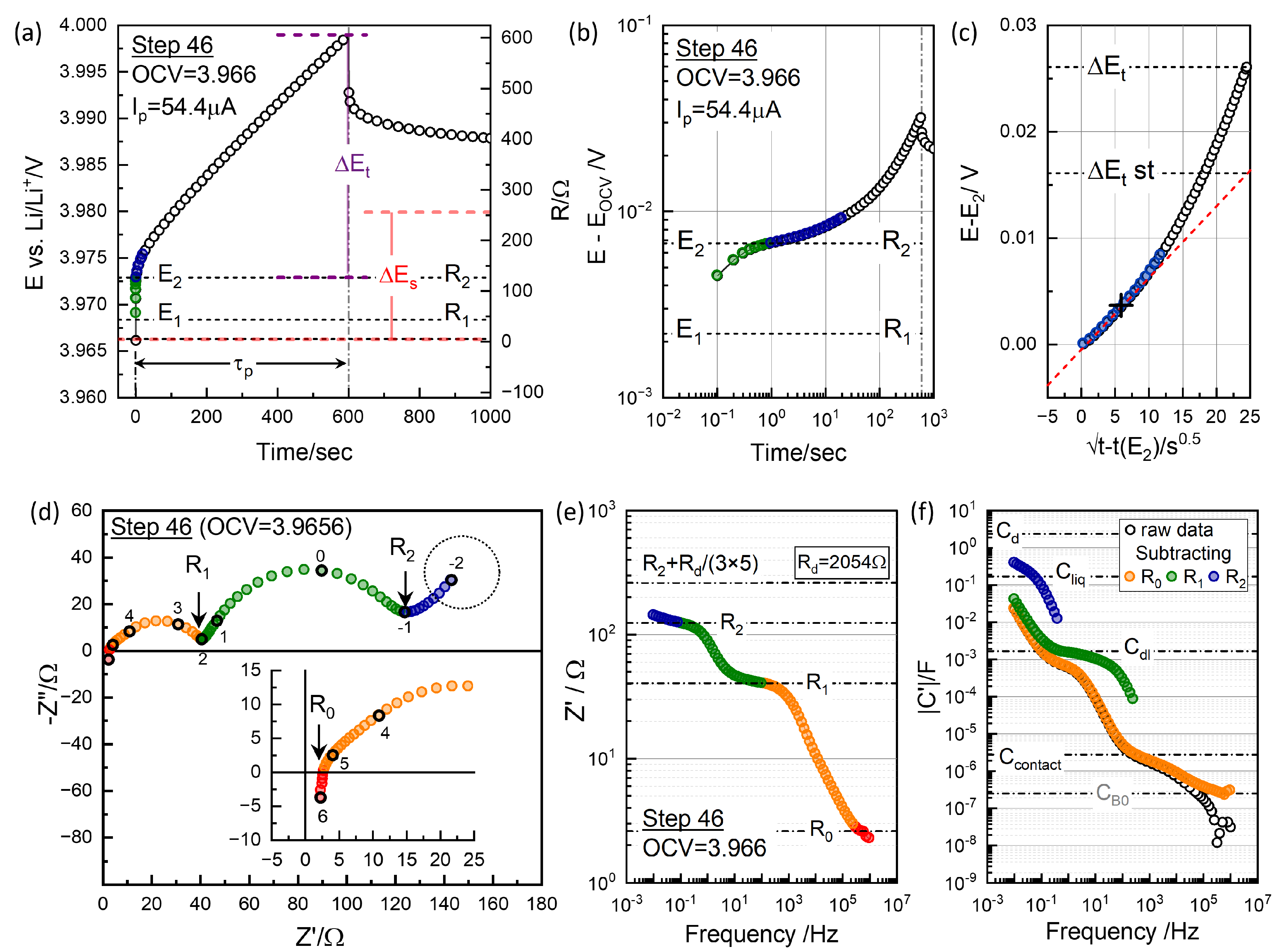

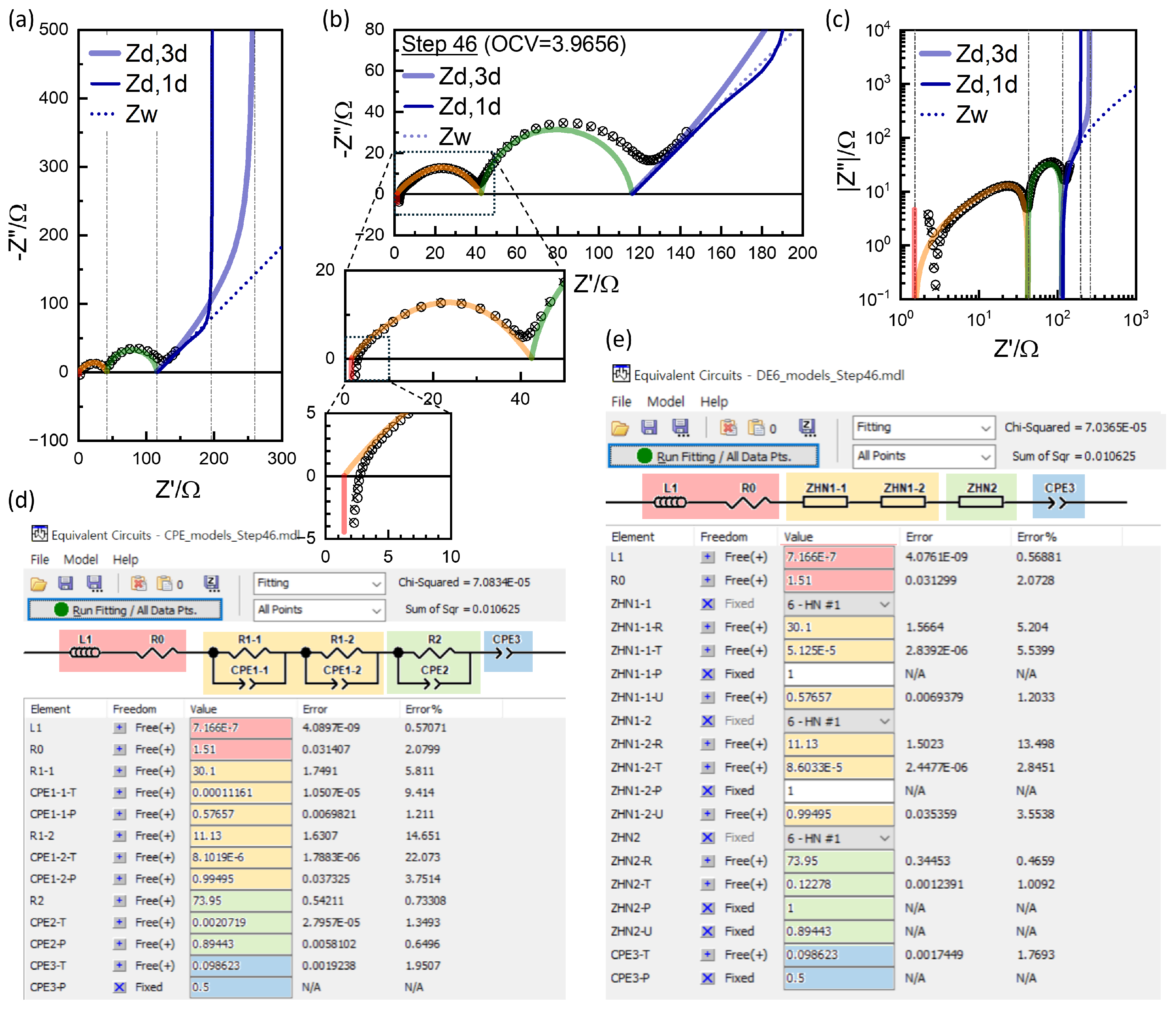

Figure 6(a).

is the molar mass and

, the molar volume (cm

3/mol) of the active material NMC622.

To apply the short-time solution for thin film electrodes to battery electrodes with dispersed active material particles, the surface area determined by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method was used [

11,

13,

29]. Assuming spherical particles of the same size,

r, Eq.

1 becomes

Two approaches assume 1-dimensional and 3-dimensional (spherical) diffusion, respectively. The spherical diffusion has a higher surface area to volume ratio and three times faster relaxations for the same diffusion length [

30,

31]. In this work the particle size

r estimated from SEM, 2.54±0.49

m is used for the chemical diffusivity according to Eq.

2, as in Ref. [

17,

18].

For the kinetic factor,

, “

” contribution needs to be subtracted.

position was estimated from

of the EIS taken before the polarization,

Figure 6(d).

Figure 6(b) shows the logarithmic plot to show the short-time behavior more clearly.

Figure 6(c) shows that

dependence holds only for the initial 60 s or so.

-st extrapolated from the short time

dependence is substantially lower than

at high OCV,

Figure 6(b).

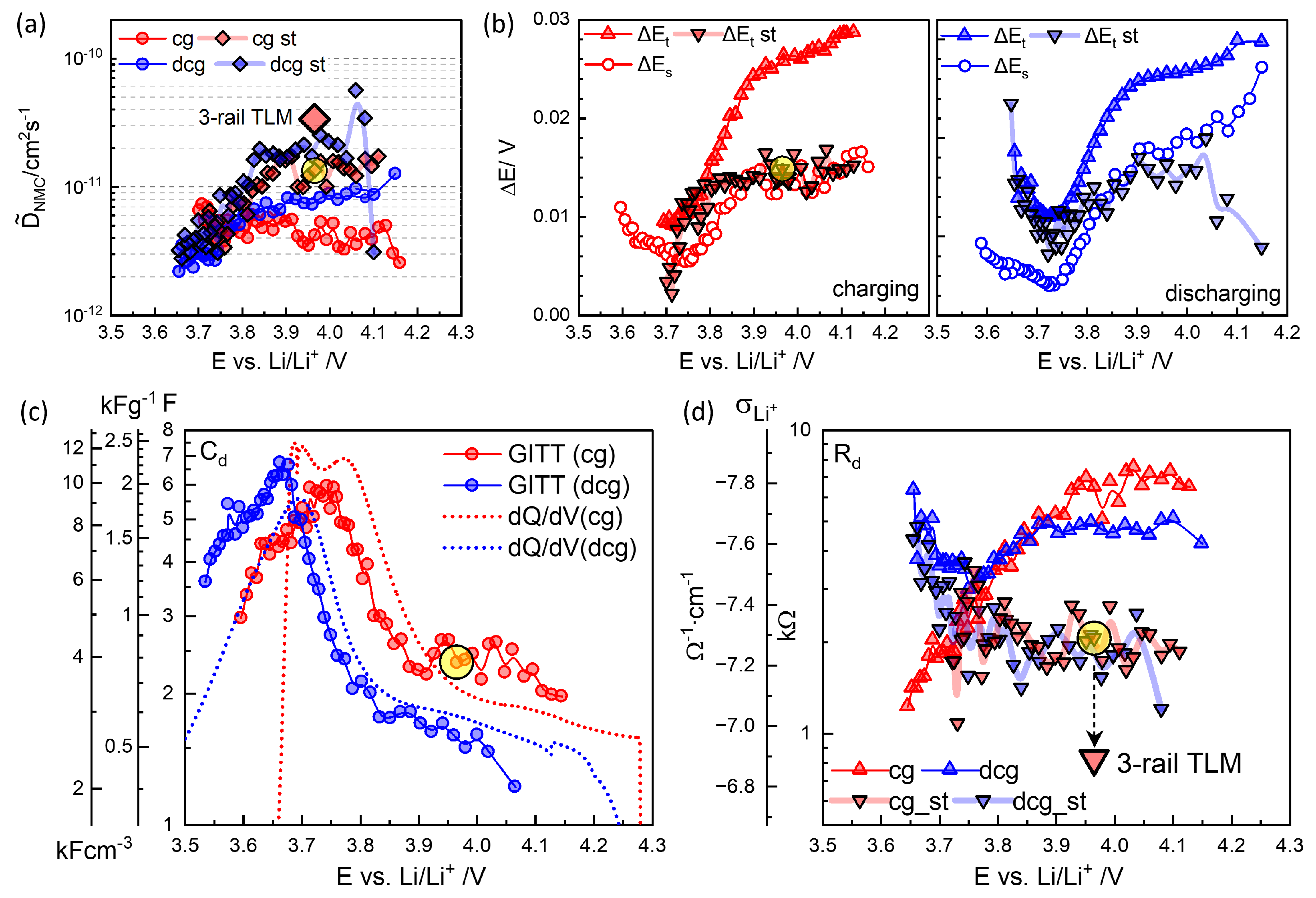

Figure 8 shows the dependence of the OCV of

,

-st,

from the charging and discharging titrations, (b), and thus obtained

(a). The thermodynamic factor

from

shows fluctuating behavior at high OCV where linear decay occurs indefinitely and the cutoff criterion

= 10

−4mV h

−2 is applied,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. No reliable estimation of

(or

-st) is made at low voltages below 3.65 V for discharging and below 3.7 V for charging, where

is too large to be estimated;

Figure 7.

from the extrapolated

dependence is somewhat higher and more consistent in charging and discharging than

. Dee et al. [

2] tested short times as 2, 5, 20, 30, 60 s and found that the chemical diffusivity decreased with more extended titration periods, which appears qualitatively consistent with the results in

Figure 8(a).

Pulse periods in most GITT studies are too long as 5 min [

11], 10 min[

13,

15,

20,

22,

23], 10.95 min [

14], 15 min[

17], 20 min [

12], 25 min[

16], 30 min[

19], 1 h [

18] etc. The pulse period determines the number of steps. If pulse time sufficiently short for a short-time solution is used, the GITT experiment can be impractically long, especially with relaxation periods sufficiently long. In the original research [

1], very small solid solution regions between two-phase regions were examined, while the current application covers the entire SOC for layered oxides.

from

and

-st is around 10

−11 cm

2s

−1, no significant and clear variation with OCV, consistent with other studies [

11,

17,

18,

19]. Similar observations have been reported for all layered oxides [

11,

19]. Such little dependence on the OCV in the chemical diffusivity in these materials is surprising. In the following sections, the limitation in the GITT application that does not consider porous electrodes and overlapping liquid phase diffusion will be addressed by the physics-based 3-rail battery impedance model suggested by Miran Gaberšček et al. [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], for possible artifacts in the current status of the GITT analysis.

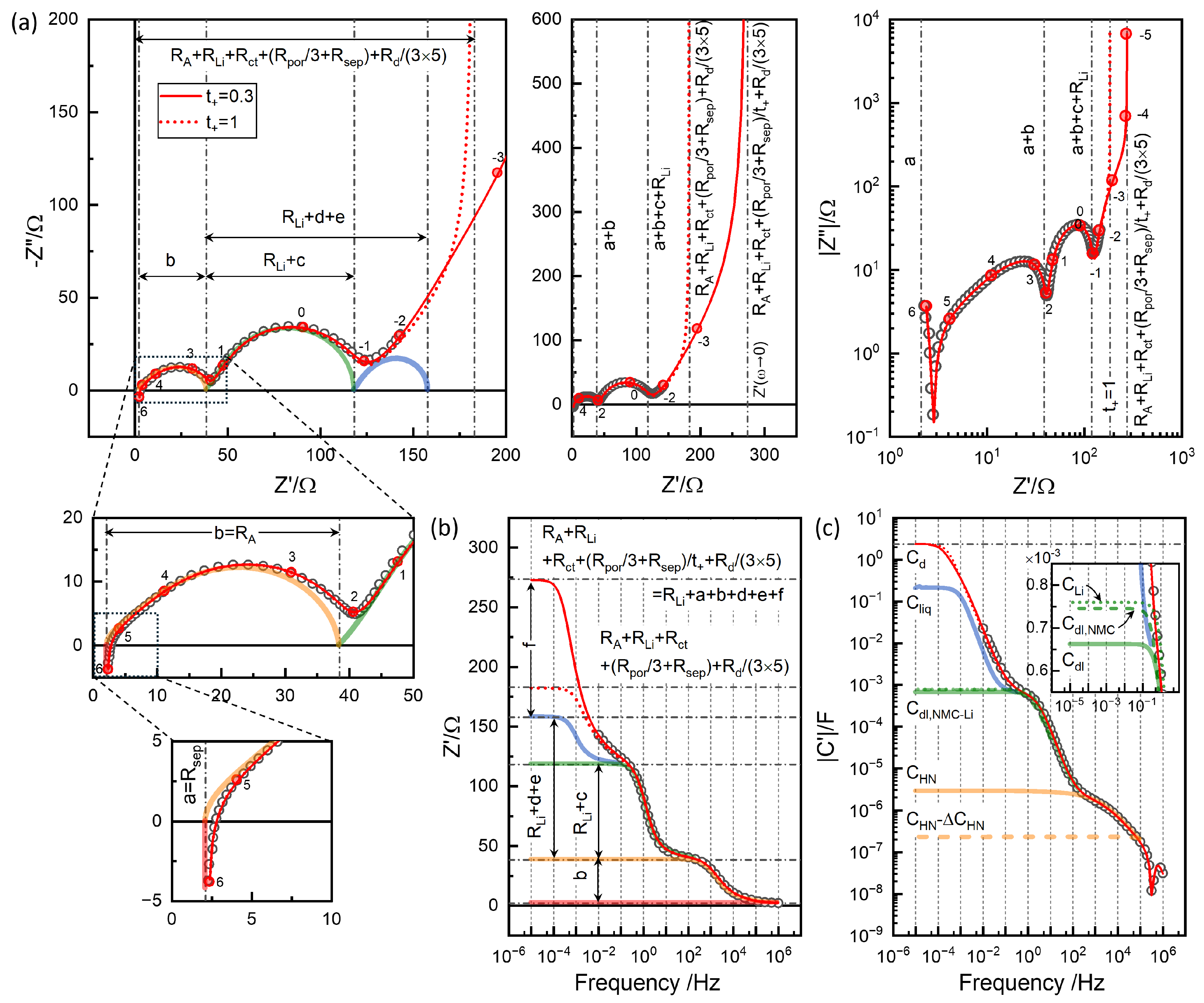

7. EIS Modeling: Conventional

Thermodynamic and kinetic aspects can be more clearly understood by relating to the equivalent circuit elements as [

31]

or

in terms of specific material properties of lithium ionic conductivity,

, electronic conductivity,

and the volumetric chemical capacitance,

.

The chemical or diffusion capacitance,

, estimated as

vary between 2 and 7 F, with a maximum around 3.75 V,

Figure 8(c). They are comparable to the differential capacity from the continuous charge-discharge cycles,

Figure 1(b). The volumetric capacitance

in Eq.

4 is indicated using the true density of NMC622 4.98 gcm

−3. From

in

Figure 8(a) and

(c),

and

can be obtained,

Figure 8(d). For Step 46 in

Figure 6,

=2054

from the short-time extrapolation corresponds to

5.2×10

−8cm

−1, assuming much higher

. Conductivity and diffusion resistance can be more easily conceptualized in the case of 1-dim diffusion with the diffusion length

l in thickness

slab, but Eq.

3 can be consistently used with the matching definition of the diffusion impedance, Eq.

5 and Eq.

6 for spherical and planar geometry [

31].

In the determination of

from the GITT analysis, the diffusion response is assumed to start at

,

Figure 6(a). The CPE-like low-frequency response of EIS should be the high-frequency limit of Eq.

5 as

If one-dimensional diffusion is assumed, as often done, the high frequency limit of Eq.

6 becomes

The response can be modeled by a constant-phase-element (CPE), briefly notated as "

Q" element in the following,

with

=0.5.

Q 0.1015 Fs

−10.5 from

=2054

, determined by GITT short-time analysis. With

2.53 F, indeed matches slope-one behavior in the lowest frequency data, indicated by the dotted circle in

Figure 6(d). When 1-dim diffusion is assumed, Eq.

8, the

becomes 2054/9=228

.

The slope-one behavior deviates at high frequencies due to the overlapping capacitive effects, which can be the double layer capacitance associated with the charge transfer resistance. EIS provides details in

contribution due to the differences in the associated capacitance effects in logarithmic scale, as shown in

Figure 6(f).

Figure 6 shows the correlation between voltage transients in GITT analysis and resistance values EIS, on linear scale, (a) and (d), and in logarithmic scale, (b) and (d). Short-time information corresponding to

and

is not shown in the time domain with the shortest interval of 0.1 s. Although the response in the time domain is equivalent, the EIS is superior since short-time responses are easily measured,

Figure 6, and modeling or analysis of the processes in multi-time scale is applicable.

The impedance spectra, similarly reported for Li-NMC622 coin cells, e.g. [

11,

32], are typically modeled using multiple CPEs or

Q elements,

Figure 9(d), represented using ZView

® program. Identical results can be obtained using any analysis software when the magnitude (modulus) of calculated or modeled impedance weighting (`calc modulus’ option in ZView

®)) is used with the least squares optimization algorithm. The fit results in cross symbols show that the modeling matches the data in circles.

In the present modeling of the components in series, the notations

and

represent the contributions added to

and

. The CPE3 has CPE3-T or

Q fitted to 0.0986 Fs

−0.5 close to 0.1015 Fs

−0.5 from the GITT analysis.

becomes 2174

very close to 2054

from GITT analysis. The thick blue spectrum in

Figure 9 indicates the simulated

. The dotted line in Fig

Figure 9(a,b,c) represents the simulation of CPE, or infinite-length Warburg impedance, to the lower frequency range. The solid line represents the simulation of the finite-length Warburg or 1-dim diffusion, Eq.

6 with

with 2174/9=241.5

, with limiting resistance

=80.5

. The limiting DC resistance

, and

can be seen more clearly in logarithmic scale in (c).

The simulated 3-dim diffusion exhibits an upward deviation from the high-frequency slope-one behavior, which appears to better describe the experimental data,

Figure 9(b). The famous finite-length Warburg diffusion for one-dimensional diffusion, Eq.

6, exhibits a downdard deviation before capacitive diverging. Lower frequency data are needed to compare two diffusion impedances and to check the models more definitely.

The analysis so far shows the consistency in GITT and EIS according to 3-dim spherical diffusion. However, because the active material spheres are dispersed, a porous electrode model should be used because the electrolyte resistance in the tortuous pore network is not negligible. Moreover, since the transference number of the active Li+ ions in the electrolyte is approximately 0.3, chemical diffusion arising from the blocked inactive, unused, anions in the liquid phase needs to be considered. This will be discussed in the following sections.

Several issues must be noted for the analysis using CPEs as in

Figure 9(d) conventionally performed. The SOC-independent contact impedance

cannot be nicely fitted by a single

, but by two

s, which are notated R1-1, R1-2, CPE1-1, and CPE1-2. The CPE1-1-P is 0.57657, strongly depressed, while CPE1-2-P is close to 1, 0.99495, almost an ideal semicircle. The substantial overlap of the two

s is shown by CPE1-1-T and CPE1-2-T, which is very similar, 5.125E-5 and 8.6033E-5. The high-frequency slope of the

response in orange is from CPE1 with the exponent 0.57657, and the smaller estimation of

, far from the intercept is correlated. The parameters of two

are strongly correlated and the individual parameters are not likely physically significant. The

position from fitting is higher from the minimum position used for reading.

is substantially smaller than the hump position used for reading. The fit results should not be considered more scientific or accurate, however. The results depend on the model details. One may use only one

for

.

, CPE2 and CPE3 may be connected in Randle’s circuit. They may be more physical modeling despite the worse overall fitting (not shown) and the

R parameters are different. The excellent goodness of fit is due to multiple CPEs with adjustable

’s (CPE-P in ZView

®)).

The response of

overlapping with diffusion impedance was attributed to the charge transfer resistance [

32], with the characteristic SOC dependence indicated in

Figure 7. The associated capacitance should be the double-layer capacitance, indicated in

Figure 6(f), around 0.0015 F. The magnitude of the capacitance in

can be directly found by subtracting the series resistance, as shown in

Figure 6(f), as the capacitance of the circuit

is reduced by the series resistance. The value is comparable to

Q, CPE2-T 0.020719 Fs

−1α, and often,

Q values are reported as capacitance, which is incorrect.

Q becomes

C only when

=1. In the conventional EIS modeling using CPEs, an effective

C from

is more properly estimated from the peak frequency,

, as

.

also indicates which are higher or lower frequency responses. Therefore, it is recommended to use the equation with parameters

R and

and

as

where

. The equation corresponds to a special case of Havriliak-Negami impedance [

30],

which is available in ZView

® and applied in

Figure 9(e). The fit results of the two models are shown to be identical.

can be estimated from ZHN2-T and ZHN2-R or

as

as 0.0166 F, matching the value indicated in

Figure 7(f).

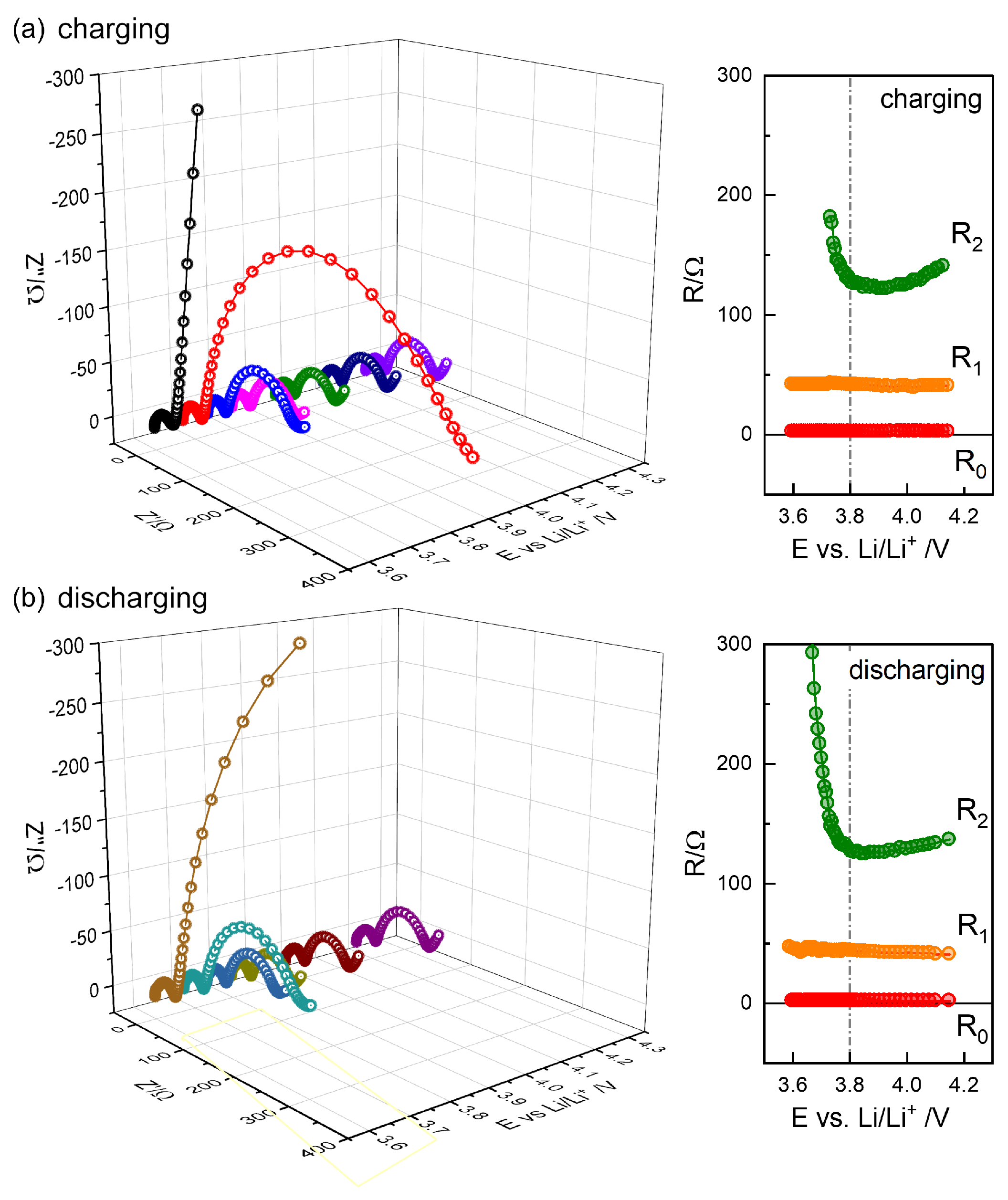

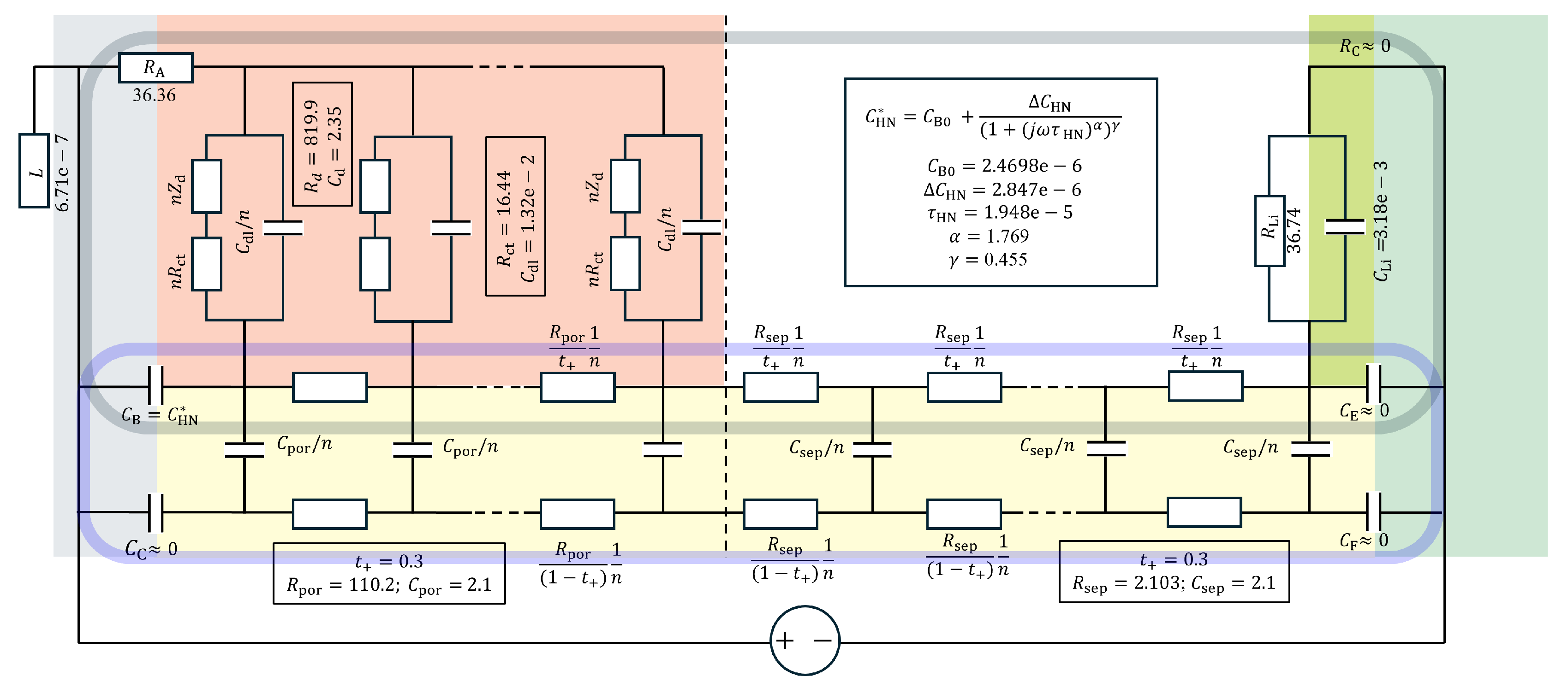

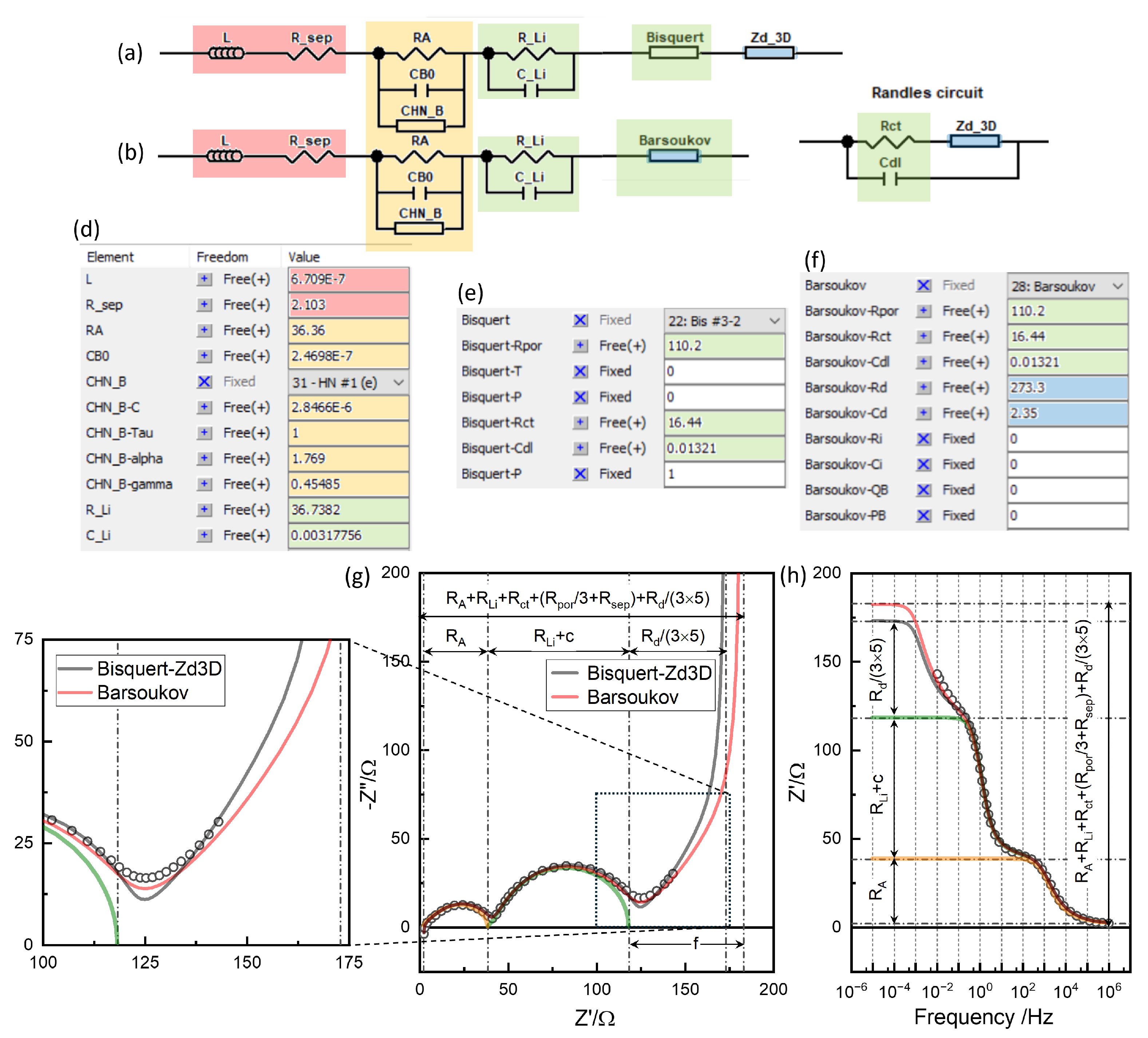

8. EIS Modeling: Porous Electrodes

The non-negligible resistance of the electrolyte in the tortuous pore network,

, should be described by the transmission line models (TLM) indicated in the gray box in

Figure 10, which is equivalent to the model in

Figure 11(b) where

named as Barsoukov TLM in view of the extensive description[

30]. The related battery models are available in MEISP[

33] (or FitmyEIS[

34]), or ZView

® DX-28, can be used, as shown in

Figure 11(b) and (f). As the relaxation times for

are substantially longer, high-frequency response of

can be described by

with

=0 in Eq.

12, a model for electrodes in fuel cells or electrolyzers [

35], which is known as a Bisquert TLM in view of the extensive work by Prof. Bisquert e.g.[

36]. ZView

® DX-22 model can be used as shown in

Figure 11(a) and (e). The impedance magnitude of

becomes

The

c notation is after [

3,

4].

With substantial contribution to

by the lithium counter electrode, separately confirmed [

37] modeled as

,

is fitted (adjusted) to 110.2

and

16.44

, which gives

c=43.05

. With

=36.74

becomes 79.78

, as indicated in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. The

for NMC electrode is fitted to 0.01321 F and

0.003177 F, differ by the factor 4, but, as shown in the inset of

Figure 11(c), the effects in EIS, affected by the series

, are similar. The overall

is somewhat reduced due to the series connection of the two capacitors and modified by

R parameters.

is now closer to the hump or minimum, reading position of

than the conventional CPE fitting in

Figure 9.

The substantial

of the porous network in

is indicated by the high-frequency slope-one behavior in the green spectrum, which is the overlapping range of

and

. The modeling is thus strongly correlated with the modeling of the

response. The

or

is represented as a single

, unlike two (

) modeling in the previous section. The additive capacitance functions describe the overlapped feature. A modified Debye circuit, or Havriliak-Negami capacitance,

with well-defined low-frequency limiting capacitance

, and high-frequency limit

. The exponents are fitted as

=0.455 and

=1.769, which is close to the versatile case of

=0.5 and

=2 [

38,

39,

40]. The model is more excellent than the strongly overlapping (

)s, since

and

and

are directly indicated in the raw data,

Figure 12(c). The distributed capacitance can physically describe the lateral inhomogeneity in the electrode and current collector interface. The well-defined limiting

corresponds less depressed arc at the low frequency, shown in detail in the inset of

Figure 12(a), compared to

Figure 11(b). It is also shown that

is closer to the intercept than for the conventional CPE fitting with

=0.57≪1,

Figure 9.

The capacitance function, physically shown to block the electrolyte rail in

Figure 10, can be directly connected in parallel to

and can also be connected outside the TLM. The ohmic resistance of the separator,

or

is notated as

, represented as

n resistors of

, which is trivial for

=1, can also be connected outside the TLM. The black round boxed part can be thus represented by the model

Figure 11(b).

Characteristic SOC dependence in

or

is due to charge transfer resistance of NMC electrode,

[

4,

6,

7].

and

are likely to dullify the SOC dependence of

in

or

. Ideal Bisquert TLM and

parallel circuit describe the data excellently (correlated with the modeling of

) and

R and

C parameters are obtained without complications in using CPEs in the previous section,

Figure 9. The results also indicate the poor reliability in the separated parameters, as the respective NMC electrode and Li electrode response are not ideally described [

4,

6,

7,

41]. Similarly, as CPE modeling, modeling of the multiple responses can describe the overall data with large correlated uncertainties in the parameters. For the theoretical discussion in the following, these parameters are used and

=819.9

, the adjusted one to the final model in

Figure 12.

in

Figure 11 is defined as 819.9/3=273.3

.

Figure 11(g,h) shows the difference when the diffusion impedance

is properly included in TLM, notated as “Barouskov”, (b) in comparison when it is connected in series to the electrode reaction, notated as “Bisquert-Zd3D”, (a), often done in the literature, as pointed out in the previous section. while for “Bisquert-Zd3D”,

, are simply added.

Diffusion impedance in TLM increases the DC limit resistance,

, with non-negligible

, on the other hand. The overall DC resistance

of Barsoukov TLM,

,

of TLM, becomes

where

, pore resistance

, as for

, Warburg Open, and

for

are simply added, as if they are connected in series. They do not match the well-distingished

in EIS, which is

, Eq.

14 and plus

. The additional resistance due to the solid-state diffusion becomes

which becomes

, only when

=0. With non-negligible

, i.e. for TLM, The

c and

f cannot be simply attributed to the single

or

components. The resistance values read from the plots or determined by the conventional

modeling do not provide clear physical significance. The physics-based EIS modeling should deconvolute the meaningful

R parameters.

As shown more clearly in the magnified view in

Figure 12(b), the transient above

for porous electrodes, the “Barsoukov” case, describes the raw data better in that the transition is more smoothly connected, compared to

, Eq.

7, connected to the “Bisquert” response in series.

parameter 819.9

could be better adjusted but is kept to the final adjustment for the liquid phase diffusion in the following section for clarity.

Figure 12.

3-rail TLM simulations for

=1 and 0.3: (a) impedance plane plots in different ranges of linear and logarithmic scales; (b) Real impedance Bode plot; and (c) Capacitance Bode plot. Colored partial spectra indicate

and

and

,

,

from raw data

Figure 6(c,d,e).

Figure 12.

3-rail TLM simulations for

=1 and 0.3: (a) impedance plane plots in different ranges of linear and logarithmic scales; (b) Real impedance Bode plot; and (c) Capacitance Bode plot. Colored partial spectra indicate

and

and

,

,

from raw data

Figure 6(c,d,e).

9. EIS vs. GITT: Transference Number

In the Barsoukov model discussed above, the electrolyte in the separator,

, and in pores

is considered a pure resistor. On the other hand, Newman’s battery model is centered on diffusion in the solution or electrolyte, which arises because negative ions, here,

, unused, build up the salt concentration gradient, whereby the Li

+ ion transport occurs, which is described by the solution diffusivity,

[

42]. The concentration gradient established in the liquid phase can be seen in battery simulations by Newman’s model, e.g., PyBaMM [

43].

The impedance study according to Newman’s model [

44,

45,

46] pointed out that the chemical diffusivity of active material cannot be correctly estimated since the solution diffusion process overlaps. Although liquid diffusivity, 10

−6cm

2s

−1, is far higher than solid-state diffusivity, 10

−11cm

2s

−1, as the effective diffusion length of the electrodes and the separator can be 3 to 5 times the nominal thickness 180

m and 25

m, due to the tortuosity, which is much larger than the active particle size 2.54

m for solid-state diffusion. As the relaxation times

increases with the squared distance over the diffusivity, they can be comparable [

46].

In Newman’s concentrated solution theory for lithium-ion battery electrolytes the parameters of kinetic interactions between solvated cations, solvated anions, and large solvent molecules are involved in the diffusivity,

, conductivity,

, and transference number,

. Most applications of the Newman model do not consider full kinetic parameters for interactions, but independently varied

, conductivity,

[

44,

45,

46].

When Nernst-Planck flux behavior of the binary electrolyte, Li

+ and

, is assumed, ambipolar diffusion occurs similar to the

for the lithium intercalation in the active mixed-conductor material, Eq.

4, as

where

represents the liquid electrolyte conductivity. and the

which can be represented by the equivalent circuits in the lower blue box in

Figure 10. The Nernst-Planck model of LIB appears roughly and self-consistently applicable since the determination

by the Bruce-Vincent method [

47], widely used, is also based on the Nernst-Planck model. Newman’s model becomes the Nernst-Planck model for the dilute solution as the kinetic interactions are negligible [

42]. Nernst-Planck model is centered on the charge neutrality between the two carriers and the thermodynamic activity different from the ideal dilute solution can be still addressed in

, similarly as for

defined by the lithium activity represented by OCV [

48].

Moškon et al.[

3,

4] practically simplified a more rigorous 3-dimensional network, as also reported by Siroma et al.[

49], into the 2-dimensional 3-rail TLM in

Figure 10, where the porous electrode model discussed above and the Nernst-Planck electrolyte model are combined. In the present version, the parameter

is applied consistently to the liquid electrolyte in different regions, which is physically reasonable and simplifies parameter fitting (adjustment).

The porous battery electrode or the Barsoukov model considered in the previous section corresponds to the Li

+ transference number

=1.

for LIB electrolytes by Bruce-Vincent method are around 0.3 [

50]. The principle is more rigorously and practically applicable by measuring EIS down to the low frequency close to DC limit without DC polarization [

37,

51] and values around 0.3 are found for 1M LiPF

6 EC:DMC 1:1 [

37].

The full equivalent circuit in

Figure 10 describes essential reactions in solids and liquids and interfaces in a physics-based way. A numerical calculation is required to describe the three-rail TLM and/or the liquid electrolyte TLM through different regions like the separator and electrodes [

41]. The code was provided to J.S.L. by Prof. M. Gaberšček in 2023, June, and is now available in the supplementary information of Ref. [

6,

7].

The blue spectrum indicated in

Figure 12, simulated with

=0, represents the simulation of additional impedance when

=0.3 compared to

=1,

Figure 11, involving the chemical capacitance

and

. The respective Li

+ ion resistance are

=2.103/0.3=7.01

, and

=109.9/0.3=366.3

, and PF

−6 ion resistance,

=2.103/0.7=5.00

, and

=109.9/0.7=157

.

The additional contribution in the blue spectrum from the separator with

=0.3 is thus

amounting to 4.907

. For pores in the electrode,

replaces

in Eq.

14

amounting to 77.72

, whereas

c = 43.05

, and thus

= 34.67

is the additional contribution. The magnitude of the additional impedance represented by the blue spectrum is thus

=39.58

.

The diffusional relaxation is represented by

and

as [

52,

53].

where

and

are effective length of the tortuous liquid paths. The factor

becomes 4.76 for

=0.3.

While it is likely that

, as 4.907

vs. 34.67

, and that

, the two responses are not distinguished in the experimental data [

4,

6,

7]. It is assumed

=2.1 F from the capacitance value indicated in the raw data,

Figure 6(f),

, corresponds to

of the chemical capacitance of the `Jamnik-Maier model’ [

52,

53]. The factor 3 for Warburg Short behavior and

from the halved diffusion length in the symmetric cells. The model can be analyzed/simulated using ZView

® DX-15, for example.

With these parameters determined and/or assumed so far, i.e.,

=2.35 F, from GITT OCV,

,

,

,

,

,

, from Bisquert model for porous electrodes, and with

assumed, or separately determined, and

= 2.1 F from the indication in the raw data in

Figure 6(f),

is best adjusted to 819.9

,

Figure 12, which is less than from GITT analysis, shot-time extended, 2054

, highlighted in

Figure 8(d), or 2174

from the equivalent EIS analysis,

Figure 8(d), and the corresponding increase in

,

Figure 8(a), from the highlighted value. The difference is within a factor 3. The overall DC resistance can be generalized as

which becomes Eq.

16 for

=1,

Figure 12 and

f indicated in

Figure 12.

with

d in Eq.

21 and

e in Eq.

20.

Due to the difficulty in reliable estimation of the parameters in

, i.e., in separating

and

with parameters

and

, the present analysis is limited to one data of Step 46 for a theoretical demonstration. When

and

are properly estimated from the symmetrical cells or half cells of three-electrodes cells, using the physics-based model, a stronger SOC dependence is likely observed. Dee et al. [

2] reported a stronger OCV dependence of

of an NCA electrode from Newman’s model compared to GITT analysis. A strong decrease in

of an NCA electrode with OCV was found [

37]. The strong OCV-dependent kinetics of NMC 622 electrode is also suggested by the relaxation behavior observed in this work,

Figure 5.

10. Outlook

After more than a decade of efforts for GITT combined with EIS studies led by J.S.L, GITT is not considered a useful method for determining the chemical diffusivity of battery electrodes. Apart from the current status of too long pulse time and likely insufficient relaxation times, against the original principle and purpose for short-time diffusion solution and the equilibrium OCV curves, the response of the liquid phase in pores is likely to affect the GITT analysis for solid phase diffusivity strongly. Uncharacteristic OCV dependence of the diffusivity observed in many studies [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

22,

23] suggested to be the indication of the liquid-phase diffusion.

Despite important physics-based insights into EIS, numerical or unwieldy analytic models [

44,

45,

46,

49] have been very limited in raw data analysis, since the experimental data must be compared with the simulation for each set of parameters to be adjusted. The Python code for the 3-rail TLM [

6,

7] is simple and the calculation is much faster than the rigorous network with negligible accuracy loss [

4]. The 3-rail TLM by Gaberšček et al. has been demonstrated for experimental data [

3,

4,

6,

7,

41]. The analysis can be rigorously applied to symmetric cells [

6,

7] or three-electrode cells [

37], which are the single-electrode responses. For essential low-frequency information, e.g., down to 10

−4 Hz within a practical time, ca. 3 h, multi-sine EIS can be utilized, available in commercial instruments [

37].

As demonstrated in

Figure 11, the Bisquert or Barsoukov TLM, or a general two-rail TLM has an analytic solution [

54], and the parameters can be fitted using optimization algorithms. The liquid phase diffusion represented by

,

, and

, and the solid-state diffusion, by

and

, overlap non-trivially, as indicated by

d and

f. The determination of these parameters or deconvolution of the two diffusion processes should be done by manual adjustment using 3-rail simulations, which seem to require insight, expertise, time, and patience [

3,

4,

6,

7,

41]. Recently, an approximate two-rail TLM has been developed for the three-rail TLM[

55], where Nernst-Planck liquid electrolyte TLM is approximated by simplified lumped circuits in the two-rail porous electrode model, so that optimization using analytic two-rail TLM is possible.

Even with such a substantial advance, as a general problem in the least-squares fitting for the multiparameter determination, the unphysical correlation of the fit parameters is difficult to avoid or control. EIS of the temperature-dependent multiple data set can address the unphysical correlation of the fit parameters in the single data analysis [

31,

51]. It has recently proved to be a powerful approach in battery EIS where temperature-independent

C parameters and contact impedance

can be uniquely separated from Arrhenius behavior

R parameters when multiple data at different temperatures are fitted together [

37]. Application to NMC622 and other electrode materials is under progress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.L. and E.C.S.; methodology, J.S.L. and E.C.S.; software, T.L.P and S.H.; validation, J.S.L., H.H.C., and J.L.; formal analysis, A.I., T.L.P, and J.S.L.; investigation, A.I., T.T.T.N., T.T.T.H., N.A.G., P.C.W, S.B.Y., and O.J.L.; data curation, A.I. and J.S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I., T.T.T.N.; writing—review and editing, J.S.L; supervision, J.S.L., C.J.P., and J.K.; funding acquisition, J.K. and J.S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.