Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

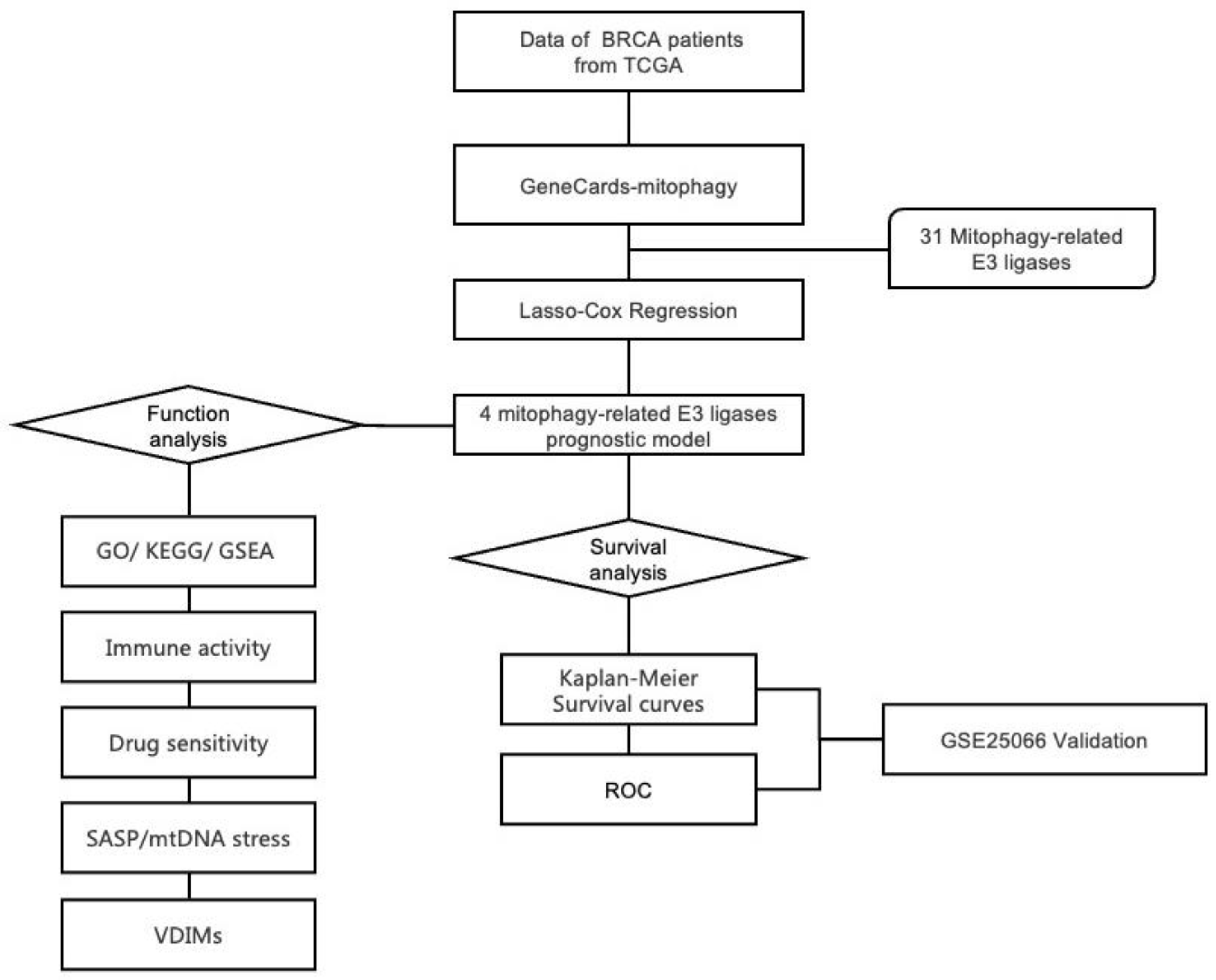

2.1. Construction of Mitophagy-related E3 Ubiquitin Ligases Prognostic Model

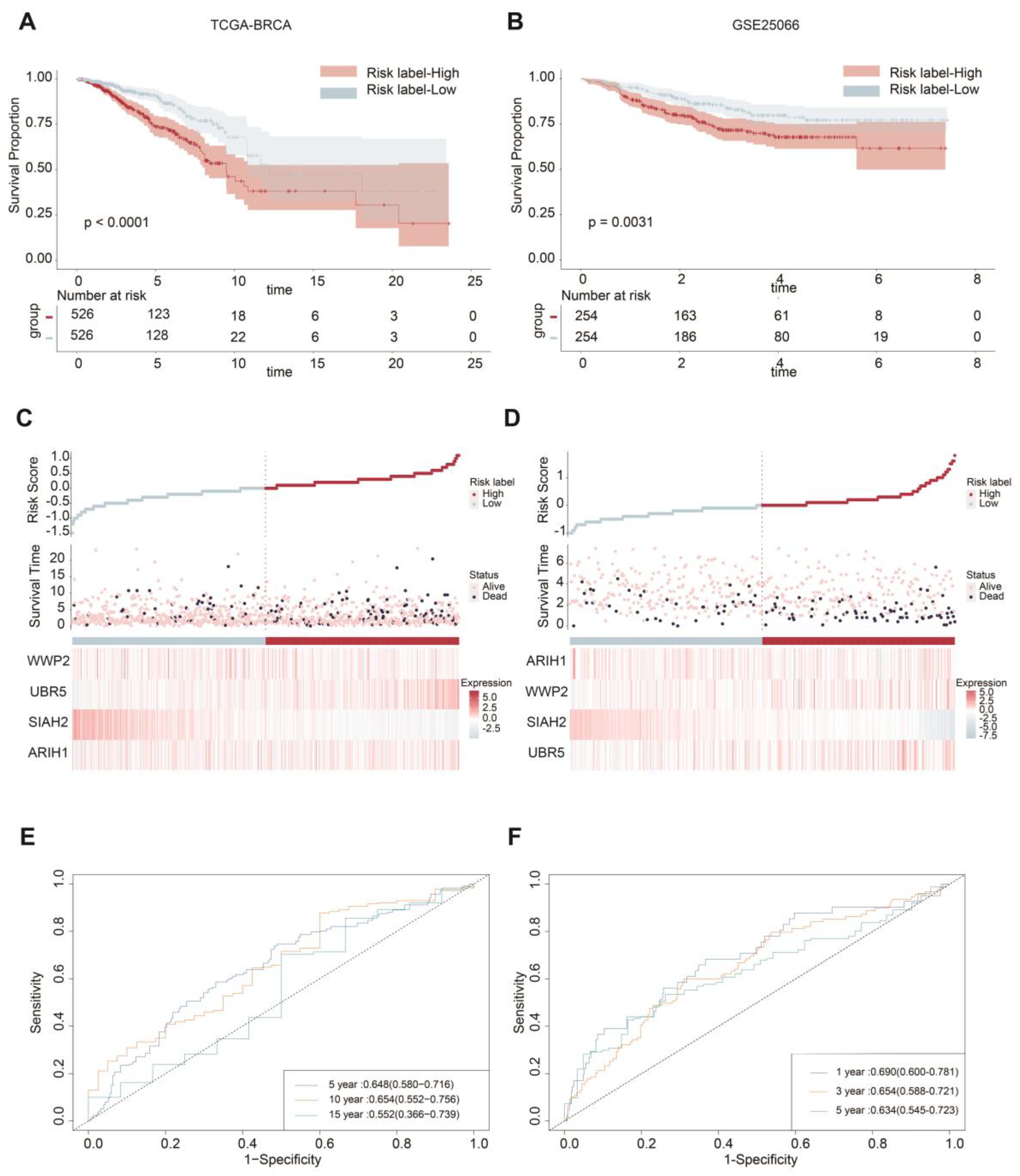

2.2. ASUW Prognostic Model Effectively Predicted Poor Breast Cancer Outcomes

2.3. Functional Enrichment Analyses of DEGs between Two Groups

2.4. TIME Comparisons between Two Groups Upon ASUW Prognostic Model

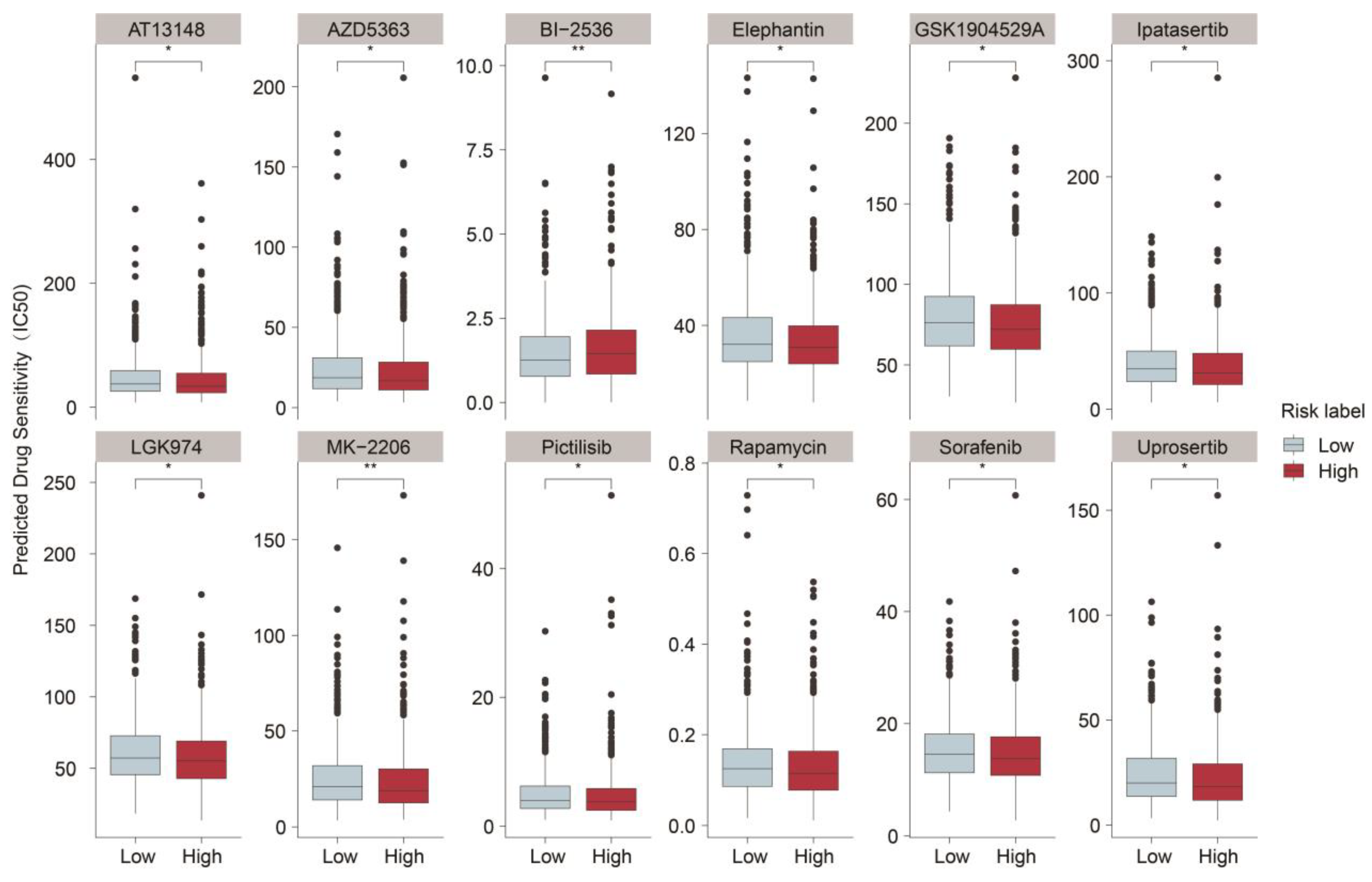

2.5. Prediction of Sensitive Drugs for BRCA upon ASUW Prognostic Model

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.4. Construction of a prognostic model

4.5. Overall survival analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SASP | senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| BRCA | breast cancer |

| TIME | tumor immune microenvironment |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| OS | overall survival |

| VDIMs | vesicles derived from the inner mitochondrial membrane |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| LASSO | least absolute shrinkage and selector operator |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| AUC | area under curve |

| DEG | differentially expressed gene |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| BP | Biological processes |

| CC | Cellular Component |

| MF | Molecular Function |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| MSigDB | Molecular Signatures Database |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| KM | Kaplan-Meier |

References

- Hong, R.; Xu, B. Breast cancer: an up-to-date review and future perspectives. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2022, 42, 913–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heater, N.K.; Warrior, S.; Lu, J. Current and future immunotherapy for breast cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2024, 17, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbeck, N.; Gnant, M. Breast cancer. Lancet 2017, 389, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onkar, S.S.; Carleton, N.M.; Lucas, P.C.; Bruno, T.C.; Lee, A.V.; Vignali, D.A.A.; Oesterreich, S. The Great Immune Escape: Understanding the Divergent Immune Response in Breast Cancer Subtypes. Cancer Discov 2023, 13, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Long, H.; Hou, L.; Feng, B.; Ma, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, D.W.; Zhao, G. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xiang, A.; Lin, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Rui, T.; Ye, Q. Mitophagy: insights into its signaling molecules, biological functions, and therapeutic potential in breast cancer. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Lei, J.H.; Bao, J.; Wang, H.; Hao, W.; Li, L.; Peng, C.; Masuda, T.; Miao, K.; Xu, J.; et al. BRCA1 Deficiency Impairs Mitophagy and Promotes Inflammasome Activation and Mammary Tumor Metastasis. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2020, 7, 1903616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, A.H.; Tracy, K.; Frankenberger, C.; Boland, M.L.; Sharifi, M.N.; Drake, L.E.; Sachleben, J.R.; Asara, J.M.; Locasale, J.W.; Karczmar, G.S.; et al. Mitophagy defects arising from BNip3 loss promote mammary tumor progression to metastasis. EMBO Rep 2015, 16, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, R.; Zhang, H.L.; Huang, J.H.; Cai, R.Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Hu, B.X.; Ye, Z.P.; Li, Z.L.; Mai, J.; et al. MAPK1/3 kinase-dependent ULK1 degradation attenuates mitophagy and promotes breast cancer bone metastasis. Autophagy 2021, 17, 3011–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Alvarez, R.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Lin, Z.; Lamb, R.; Hulit, J.; Howell, A.; Sotgia, F.; Rubin, E.; Lisanti, M.P. Ethanol exposure induces the cancer-associated fibroblast phenotype and lethal tumor metabolism: implications for breast cancer prevention. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Qian, F.; Liu, D.; Ye, D.; Zhou, X.; Fang, L. Urolithin A inhibits breast cancer progression via activating TFEB-mediated mitophagy in tumor macrophages. J Adv Res 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Cellular mitophagy: Mechanism, roles in diseases and small molecule pharmacological regulation. Theranostics 2023, 13, 736–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, J.P.; Lazarou, M.; Dewson, G. Parkin and mitophagy in cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Pan, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Geng, Q. Mitophagy: A novel perspective for insighting into cancer and cancer treatment. Cell Prolif 2022, 55, e13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahabi, K.; Perwez, A.; Kamarudheen, S.; Bhat, Z.I.; Mehta, A.; Rizvi, M.M.A. Parkin gene mutations are not common, but its epigenetic inactivation is a frequent event and predicts poor survival in advanced breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, E.; Marchetti, S.; Ricci, J.E. No Parkin Zone: Mitophagy without Parkin. Trends Cell Biol 2018, 28, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasan, K.; Werner, M.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial Metabolism as a Target for Cancer Therapy. Cell Metab 2020, 32, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sack, M.N. Mitochondrial fidelity and metabolic agility control immune cell fate and function. J Clin Invest 2018, 128, 3651–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Er, P.; Cheng, J.; Chen, X.; Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Z.; Pang, Q.; Wang, P.; et al. High expression of FUNDC1 predicts poor prognostic outcomes and is a promising target to improve chemoradiotherapy effects in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Med 2017, 6, 1871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Luo, L.; Guo, C.Y.; Goto, S.; Urata, Y.; Shao, J.H.; Li, T.S. Doxorubicin-induced mitophagy contributes to drug resistance in cancer stem cells from HCT8 human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2017, 388, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glytsou, C.; Chen, X.; Zacharioudakis, E.; Al-Santli, W.; Zhou, H.; Nadorp, B.; Lee, S.; Lasry, A.; Sun, Z.; Papaioannou, D.; et al. Mitophagy Promotes Resistance to BH3 Mimetics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov 2023, 13, 1656–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulahan, T.S.; Angel, P.M. From ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer: the prognostic value of the extracellular microenvironment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2024, 43, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Freeman, G.J. The CD160, BTLA, LIGHT/HVEM pathway: a bidirectional switch regulating T-cell activation. Immunol Rev 2009, 229, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platten, M.; Nollen, E.A.A.; Rohrig, U.F.; Fallarino, F.; Opitz, C.A. Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Wu, Y.H.; Song, Y.; Yu, B. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) inhibitors in clinical trials for cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 2021, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, W.; Kadu, S.; Johnson, O.; Hasanali, Z.S.; Kelly, A.; Shestov, A.; Pajarillo, R.; Greenblatt, E.; Holmes, M.; et al. Exploiting the CD200-CD200R immune checkpoint axis in multiple myeloma to enhance CAR T-cell therapy. Blood 2024, 143, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin, N.; Podnos, A.; Tanriover, G.; Duymus, O.; Cote, E.; Khatri, I.; Gorczynski, R.M. Bidirectional effect of CD200 on breast cancer development and metastasis, with ultimate outcome determined by tumor aggressiveness and a cancer-induced inflammatory response. Oncogene 2015, 34, 3860–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guruprasad, P.; Carturan, A.; Zhang, Y.; Cho, J.H.; Kumashie, K.G.; Patel, R.P.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.H.; et al. The BTLA-HVEM axis restricts CAR T cell efficacy in cancer. Nat Immunol 2024, 25, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mingo Pulido, A.; Hanggi, K.; Celias, D.P.; Gardner, A.; Li, J.; Batista-Bittencourt, B.; Mohamed, E.; Trillo-Tinoco, J.; Osunmakinde, O.; Pena, R.; et al. The inhibitory receptor TIM-3 limits activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in intra-tumoral dendritic cells by suppressing extracellular DNA uptake. Immunity 2021, 54, 1154–1167 e1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteran, L.; Ershaid, N.; Scharff, Y.; Zoabi, Y.; Sanalla, T.; Ding, Y.; Pavlovsky, A.; Zait, Y.; Langer, M.; Caller, T.; et al. Combining TIGIT Blockade with MDSC Inhibition Hinders Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis by Activating Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Discov 2024, 14, 1252–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Sun, T.; Ye, F.; Zhang, B.; Xia, S.; et al. The anti-PD-L1/CTLA-4 bispecific antibody KN046 in combination with nab-paclitaxel in first-line treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a multicenter phase II trial. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Fang, J.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Xing, P.; Jia, K.; Hu, J.; Wang, D.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade in breast cancer: research insights and sensitization strategies. Mol Cancer 2024, 23, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Li, Y.; Tan, J.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Targeting LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT for cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 2023, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Ohashi, P.S. Clinical blockade of PD1 and LAG3--potential mechanisms of action. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, A.; Makarov, V.; Merghoub, T.; Yuan, J.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Desrichard, A.; Walsh, L.A.; Postow, M.A.; Wong, P.; Ho, T.S.; et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 2189–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Wang, S.; Bindeman, W. Clinical applications of PD-L1 bioassays for cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 2017, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, G.P.; Malla, R.R.; Basha, R.; Motofei, I.G. Contemporary clinical trials in pancreatic cancer immunotherapy targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 86, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porporato, P.E.; Filigheddu, N.; Pedro, J.M.B.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Cell Res 2018, 28, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.L.; Cui, Q.; Wang, J.Q.; Ashby, C.R., Jr.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z.X.; Chen, Z.S. The AKT inhibitor, MK-2206, attenuates ABCG2-mediated drug resistance in lung and colon cancer cells. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1235285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, A.J.; Tripathy, D.; Albain, K.S.; Symmans, W.F.; Rugo, H.S.; Melisko, M.E.; Wallace, A.M.; Schwab, R.; Helsten, T.; Forero-Torres, A.; et al. MK-2206 and Standard Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Improves Response in Patients With Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive and/or Hormone Receptor-Negative Breast Cancers in the I-SPY 2 Trial. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.C.; Adjei, A.A.; Bahleda, R.; Besse, B.; Ferte, C.; Planchard, D.; Zhou, J.; Ware, J.; Morrissey, K.; Shankar, G.; et al. A phase IB dose-escalation study of the safety and pharmacokinetics of pictilisib in combination with either paclitaxel and carboplatin (with or without bevacizumab) or pemetrexed and cisplatin (with or without bevacizumab) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 2017, 86, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.J.; Lin, S.Y.; Chuang, K.H.; Chen, M.; Ho, H.O.; Chen, L.C.; Hsieh, C.M.; Sheu, M.T. Combined Docetaxel/Pictilisib-Loaded mPEGylated Nanocarriers with Dual HER2 Targeting Antibodies for Synergistic Chemotherapy of Breast Cancer. Int J Nanomedicine 2022, 17, 5353–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; George, S.; Hammers, H.J.; Srinivas, S.; Tykodi, S.S.; Sosman, J.A.; Procopio, G.; Plimack, E.R.; et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselga, J.; Campone, M.; Piccart, M.; Burris, H.A., 3rd; Rugo, H.S.; Sahmoud, T.; Noguchi, S.; Gnant, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Lebrun, F.; et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2012, 366, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, M.; Lu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Increased ATF2 expression predicts poor prognosis and inhibits sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Redox Biol 2023, 59, 102564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wu, F.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Rong, D.; Reiter, F.P.; et al. The mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: theoretical basis and therapeutic aspects. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoffski, P.; Blay, J.Y.; De Greve, J.; Brain, E.; Machiels, J.P.; Soria, J.C.; Sleijfer, S.; Wolter, P.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Fontaine, C.; et al. Multicentric parallel phase II trial of the polo-like kinase 1 inhibitor BI 2536 in patients with advanced head and neck cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, soft tissue sarcoma and melanoma. The first protocol of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Network Of Core Institutes (NOCI). Eur J Cancer 2010, 46, 2206–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Hou, P.; Lv, Y.; Li, G.; Cao, G.; Wang, H.; Lin, W. BRCA1 orchestrates the response to BI-2536 and its combination with alisertib in MYC-driven small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Liu, J.; Bao, L.; Qu, H.; Xiang, J.; Sun, P. Upregulation of the ferroptosis-related STEAP3 gene is a specific predictor of poor triple-negative breast cancer patient outcomes. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1032364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.M.E.; Xu, Y.; Benito, A.; Herendi, L.; Siskos, A.P.; Aboagye, E.O.; Nijhuis, A.; Keun, H.C. Lactic acidosis induces resistance to the pan-Akt inhibitor uprosertib in colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer 2020, 122, 1298–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, G.; Henry, S.; Nandi, A.; Debnath, R.; Singh, S.; Nayak, A.; Susnik, B.; Boone, M.M.; Zhang, Q.; Kesmodel, S.B.; et al. Immature natural killer cells promote progression of triple-negative breast cancer. Sci Transl Med 2023, 15, eabl4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Dong, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, X.; Pang, Y.; Chan, L.; Deng, Y.; Qian, C. Targeting mitochondrial dynamics by AZD5363 in triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell-derived spheres. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2023, 396, 2545–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Turner, N.C.; Barrios, C.H.; Isakoff, S.J.; Kim, S.B.; Sablin, M.P.; Saji, S.; Savas, P.; Vidal, G.A.; Oliveira, M.; et al. First-Line Ipatasertib, Atezolizumab, and Taxane Triplet for Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Clinical and Biomarker Results. Clin Cancer Res 2024, 30, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.; Bracarda, S.; Sternberg, C.N.; Chi, K.N.; Olmos, D.; Sandhu, S.; Massard, C.; Matsubara, N.; Alekseev, B.; Parnis, F.; et al. Ipatasertib plus abiraterone and prednisolone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (IPATential150): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, N.; Munro, J.; Cutiongco, M.F.; Jagiello, A.; Gadegaard, N.; McGarry, L.; Unbekandt, M.; Michalopoulou, E.; Kamphorst, J.J.; Sumpton, D.; et al. Rho Kinase Inhibition by AT13148 Blocks Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Invasion and Tumor Growth. Cancer Res 2018, 78, 3321–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Luo, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Tian, Y.; Jin, T.; Xu, F. Cellular senescence and SASP in tumor progression and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer 2024, 23, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorelli, S.; Salmonowicz, H.; Chapman, J.; Martini, H.; Vizioli, M.G.; Riley, J.S.; Cloix, C.; Hall-Younger, E.; Machado Espindola-Netto, J.; Jurk, D.; et al. Apoptotic stress causes mtDNA release during senescence and drives the SASP. Nature 2023, 622, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban-Ishihara, R.; Ishihara, T.; Sasaki, N.; Mihara, K.; Ishihara, N. Dynamics of nucleoid structure regulated by mitochondrial fission contributes to cristae reformation and release of cytochrome c. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 11863–11868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, T.L.; Windley, S.P.; Gervinskas, G.; Balka, K.R.; Rowe, C.; Lane, R.; Tailler, M.; Nguyen, T.N.; Ramm, G.; Lazarou, M.; et al. Exposure of the inner mitochondrial membrane triggers apoptotic mitophagy. Cell Death Differ 2024, 31, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashar, A.; Bussi, C.; Fearns, A.; Capurro, M.I.; Gao, X.; Sesaki, H.; Gutierrez, M.G.; Jones, N.L. Lysosomes drive the piecemeal removal of mitochondrial inner membrane. Nature 2024, 632, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picca, A.; Faitg, J.; Auwerx, J.; Ferrucci, L.; D'Amico, D. Mitophagy in human health, ageing and disease. Nat Metab 2023, 5, 2047–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcala, S.; Sancho, P.; Martinelli, P.; Navarro, D.; Pedrero, C.; Martin-Hijano, L.; Valle, S.; Earl, J.; Rodriguez-Serrano, M.; Ruiz-Canas, L.; et al. ISG15 and ISGylation is required for pancreatic cancer stem cell mitophagy and metabolic plasticity. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.Q.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.F.; Fang, X.Y.; Li, C.L.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H.Y.; Miao, J.Y.; et al. Targeting ATAD3A-PINK1-mitophagy axis overcomes chemoimmunotherapy resistance by redirecting PD-L1 to mitochondria. Cell Res 2023, 33, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.E.; Shadel, G.S. Mitochondrial DNA Release in Innate Immune Signaling. Annu Rev Biochem 2023, 92, 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Rao, J.; Zhang, L.H.; Xue, K.M.; Li, L.; Li, J.J.; Chen, Q.Z.; Fu, R. OMA1 competitively binds to HSPA9 to promote mitophagy and activate the cGAS-STING pathway to mediate GBM immune escape. J Immunother Cancer 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Guo, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Gou, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Development and validation of a prognostic model for mitophagy-related genes in colon adenocarcinoma: A study based on TCGA and GEO databases. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0284089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Huang, J.; Huang, J. A Mitophagy-Related Gene Signature for Subtype Identification and Prognosis Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, E.; Proics, E.; Rubio-Patino, C.; Obba, S.; Zunino, B.; Bossowski, J.P.; Rozier, R.M.; Chiche, J.; Mondragon, L.; Riley, J.S.; et al. Parkin-Independent Mitophagy Controls Chemotherapeutic Response in Cancer Cells. Cell Rep 2017, 20, 2846–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisalli, M.J.; Ianniello, G.; Savoia, C.; Cuomo, O.; Annunziato, L.; Scorziello, A. Knocking-out the Siah2 E3 ubiquitin ligase prevents mitochondrial NCX3 degradation, regulates mitochondrial fission and fusion, and restores mitochondrial function in hypoxic neurons. Cell Commun Signal 2020, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szargel, R.; Shani, V.; Abd Elghani, F.; Mekies, L.N.; Liani, E.; Rott, R.; Engelender, S. The PINK1, synphilin-1 and SIAH-1 complex constitutes a novel mitophagy pathway. Hum Mol Genet 2016, 25, 3476–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elghani, F.; Safory, H.; Hamza, H.; Savyon, M.; Farhoud, M.; Toren-Hershoviz, M.; Vitic, Z.; Ebanks, K.; Shani, V.; Bisharat, S.; et al. SIAH proteins regulate the degradation and intra-mitochondrial aggregation of PINK1: Implications for mitochondrial pathology in Parkinson's disease. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, R.; Huang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, W.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, A.; Wang, H. The role and molecular mechanism of metabolic reprogramming of colorectal cancer by UBR5 through PYK2 regulation of OXPHOS expression study. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2023, 37, e23376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chiang, C.Y.; Chen, Z.; Nathan, S.; D'Agostino, G.; Paulo, J.A.; Song, G.; Zhu, H.; Gabelli, S.B.; Cole, P.A. Enzymatic analysis of WWP2 E3 ubiquitin ligase using protein microarrays identifies autophagy-related substrates. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 101854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshi, M.; Takahashi, H.; Tokumaru, Y.; Yan, L.; Rashid, O.M.; Matsuyama, R.; Endo, I.; Takabe, K. G2M Cell Cycle Pathway Score as a Prognostic Biomarker of Metastasis in Estrogen Receptor (ER)-Positive Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakos, C.I.; Charles, K.A.; McMillan, D.C.; Clarke, S.J. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol 2014, 15, e493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Yamano, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Yamamoto-Imoto, H.; Minami, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Matsui, S.; Kaminishi, T.; Shima, T.; Ogura, M.; et al. HKDC1, a target of TFEB, is essential to maintain both mitochondrial and lysosomal homeostasis, preventing cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2306454120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Su, P.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; et al. Hypoxia-induced GPCPD1 depalmitoylation triggers mitophagy via regulating PRKN-mediated ubiquitination of VDAC1. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2443–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, I.; Szewczyk, A. Mitochondrial Ion Channels. Annu Rev Biophys 2023, 52, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Yao, B.; Dong, T.; Chen, Y.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Bai, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Tumor-resident intracellular microbiota promotes metastatic colonization in breast cancer. Cell 2022, 185, 1356–1372 e1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Fontana, A.; Panebianco, C.; Ferro, C.; Copetti, M.; Pavlovic, R.; Drago, D.; Fiorentini, C.; Terracciano, F.; Bazzocchi, F.; et al. A powerful machine learning approach to identify interactions of differentially abundant gut microbial subsets in patients with metastatic and non-metastatic pancreatic cancer. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2375483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Tian, T.; Wei, Z.; Shih, N.; Feldman, M.D.; Peck, K.N.; DeMichele, A.M.; Alwine, J.C.; Robertson, E.S. Distinct Microbial Signatures Associated With Different Breast Cancer Types. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, W.S. Cancer and the microbiota. Science 2015, 348, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, K. Microglial mitophagy integrates the microbiota-gut-brain axis to restrain neuroinflammation during neurotropic herpesvirus infection. Autophagy 2023, 19, 734–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Chen, Y.; Pan, X.; Chen, H.; Fan, L.; Wen, Y. E. coli Nissle 1917 ameliorates mitochondrial injury of granulosa cells in polycystic ovary syndrome through promoting gut immune factor IL-22 via gut microbiota and microbial metabolism. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1137089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, T.; YinWang, E.; Li, H.; Ye, Z.; Gao, J.; et al. The role of mitochondria in tumor metastasis and advances in mitochondria-targeted cancer therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2024, 43, 1419–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, G.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Pu, M.; Zhang, J. Parkin modulates the hepatocellular carcinoma microenvironment by regulating PD-1/PD-L1 signalling. J Adv Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Cao, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Gao, T.; Ren, C.; Liu, J. Mitochondrial Localized In Situ Self-Assembly Reprogramming Tumor Immune and Metabolic Microenvironment for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. Adv Mater 2024, 36, e2311043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wei, J.; Liu, P. Attacking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for targeted therapeutic treatment in human cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 85, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, C.; Feng, J.; Lin, J.; Shen, Y. SGLT1 inhibition alleviates radiation-induced intestinal damage through promoting mitochondrial homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med 2024, 224, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Yu, H. Metformin Attenuates UVA-Induced Skin Photoaging by Suppressing Mitophagy and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeser, D.; Gruener, R.F.; Huang, R.S. oncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Brief Bioinform 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene symbol | Gene ID | Full name | Classes | Risk coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARIH1 | 25820 | Ariadne RBR E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase 1 | RBR (RING-IBR-RING) | -0.100073572 |

| SIAH2 | 6478 | Siah E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase 2 | RING (Really interesting new gene) | -0.333969422 |

| UBR5 | 51366 | Ubiquitin Protein Ligase E3 Component N-Recognin 5 | HECT (Homologous to the E6AP carboxyl terminus) | 0.34620336 |

| WWP2 | 11060 | WW Domain Containing E3 Ubiquitin Protein Ligase 2 | HECT (Homologous to the E6AP carboxyl terminus) | -0.204703988 |

| Drug Name | Target | Application | Reference | IC50 (High vs Low) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MK-2206 | Akt | Lung cancer, Breast cancer, Colorectal cancer |

[40,41] | down |

| Pictilisib | PI3K | Breast cancer, Lung cancer | [42,43] | down |

| Rapamycin | mTORC1 | Breast cancer, Kidney cancer | [44,45] | down |

| Sorafenib | VEGFR, PDGFR, RAF kinases | Hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric cancer | [46,47] | down |

| BI-2536 | PLK1 | Breast cancer, Lung cancer | [48,49] | up |

| GSK1904529A | IGF-1R | Breast cancer | [50] | down |

| Uprosertib | Akt | Colorectal cancer | [51] | down |

| LGK974 | Porcupine | Colorectal cancer | [52] | down |

| Elephantin | Unclear | Further investigation is required | Unclear | down |

| AZD5363 | Akt | Breast cancer | [53] | down |

| Ipatasertib | Akt | Breast cancer, Prostate cancer | [54,55] | down |

| AT13148 | AGC family kinases | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | [56] | down |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).