Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

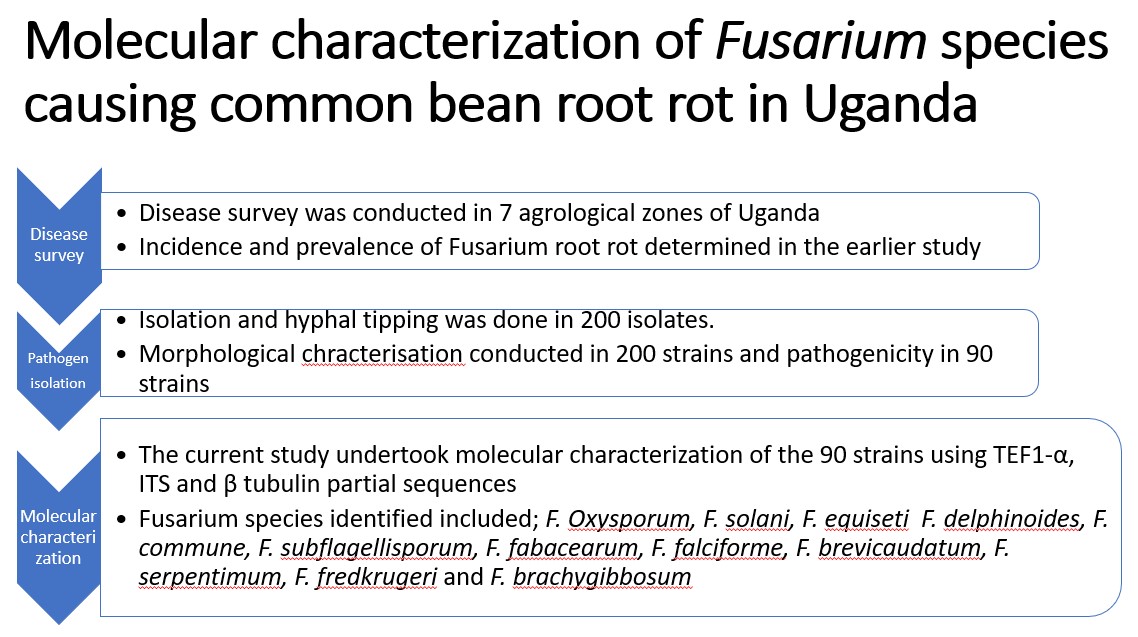

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin of Fusarium species Strains Used

2.2. DNA Extraction from Fusarium species Strains

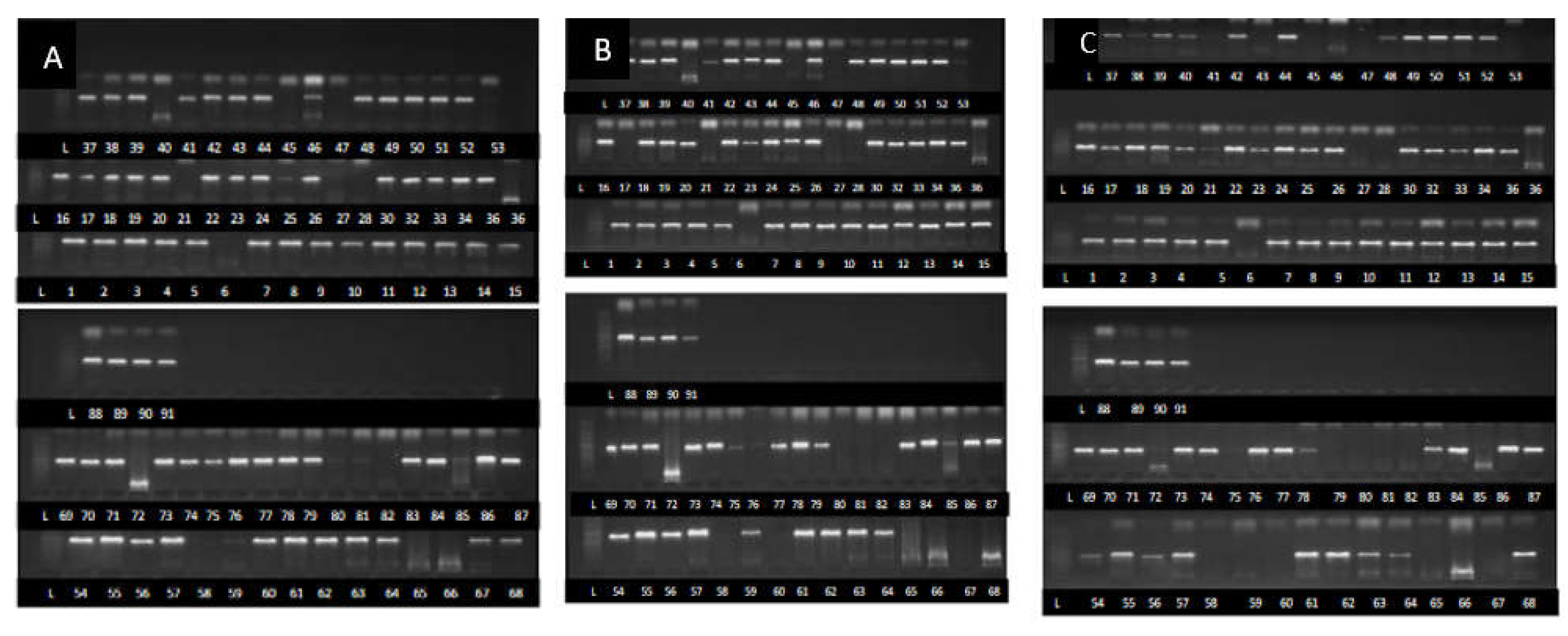

2.3. Fusarium species Identification Using TEF1-α, β Tubulin and ITS Partial Sequences

2.4. Growth Rate, Disease Severity Index (DSI) and Morphological Characteristics of Fusarium species Strains

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

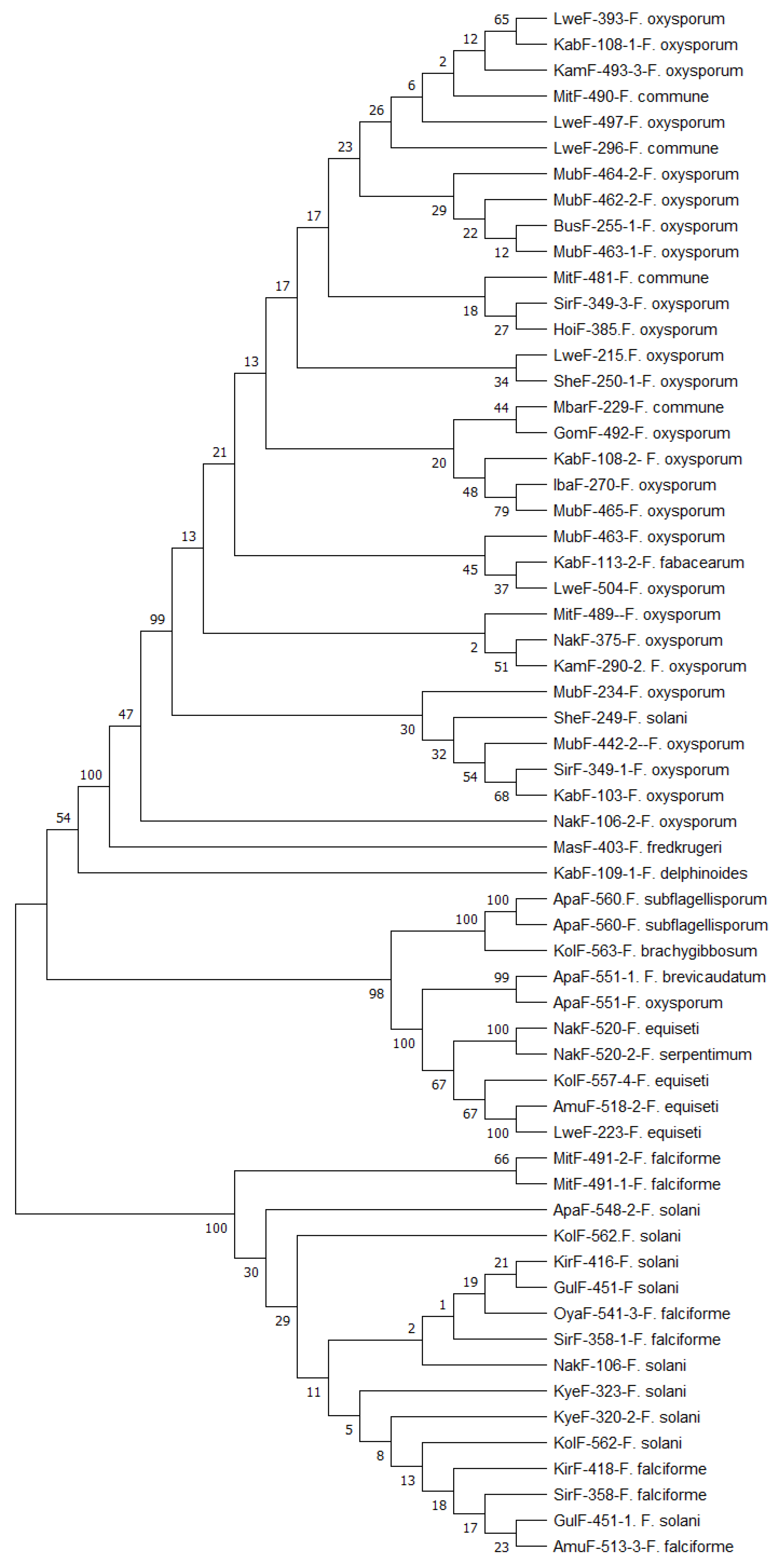

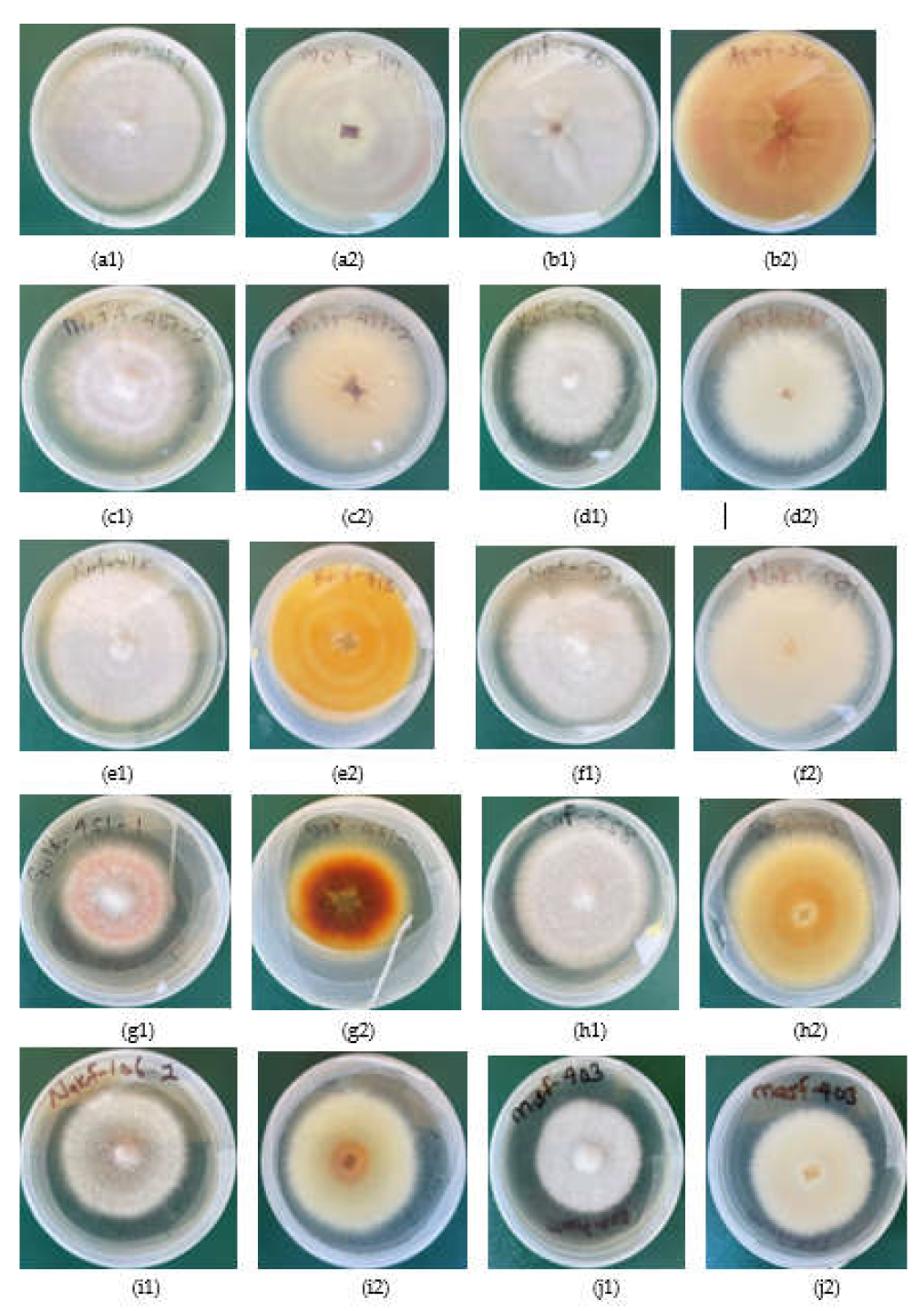

Identification of Fusarium strains Using TEF1-α Gene, β Tubulin Gene and ITS Partial Sequences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Melotto, M.; Monteiro-Vitorello, C.B.; Bruschi, A.G.; Camargo, L.E. Comparative bioinformatic analysis of genes expressed in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) seedlings. Genome 2005, 48, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agricultural Organisation of United Nations (FAO). World food and agricultural statistical pocket book. Rome, Italy, 2018, pp 28.

- CASA. Bean Sector Strategy-Uganda. CASA Uganda country team, Kampala, Uganda. 2020, pp 4. Unpublished.

- Miklas, P.N.; Kelly, J.D.; Beebe, S.E.; Blair, M.W. Common bean breeding for resistance against biotic and abiotic stresses: From classical to MAS breeding. Euphytica 2006, 147, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J. Species of Pythium Associated with Seedling Root and Hypocotyl Disease on Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) in Western Australia. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paparu, P.; Acur, A.; Kato, F.; Acam, C.; Nakibuule, J.; Musoke, S.; Nkalubo, S.; Mukankusi, C. PREVALENCE AND INCIDENCE OF FOUR COMMON BEAN ROOT ROTS IN UGANDA. Exp. Agric. 2017, 54, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abawi, G. S.; Pastor-Corrale, M. A. Root rots of beans in Latin America and Africa:Diagnosis, research methodologies, and management strategies: CIAT, Cali, Colombia, 1990, p.114. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/54258.

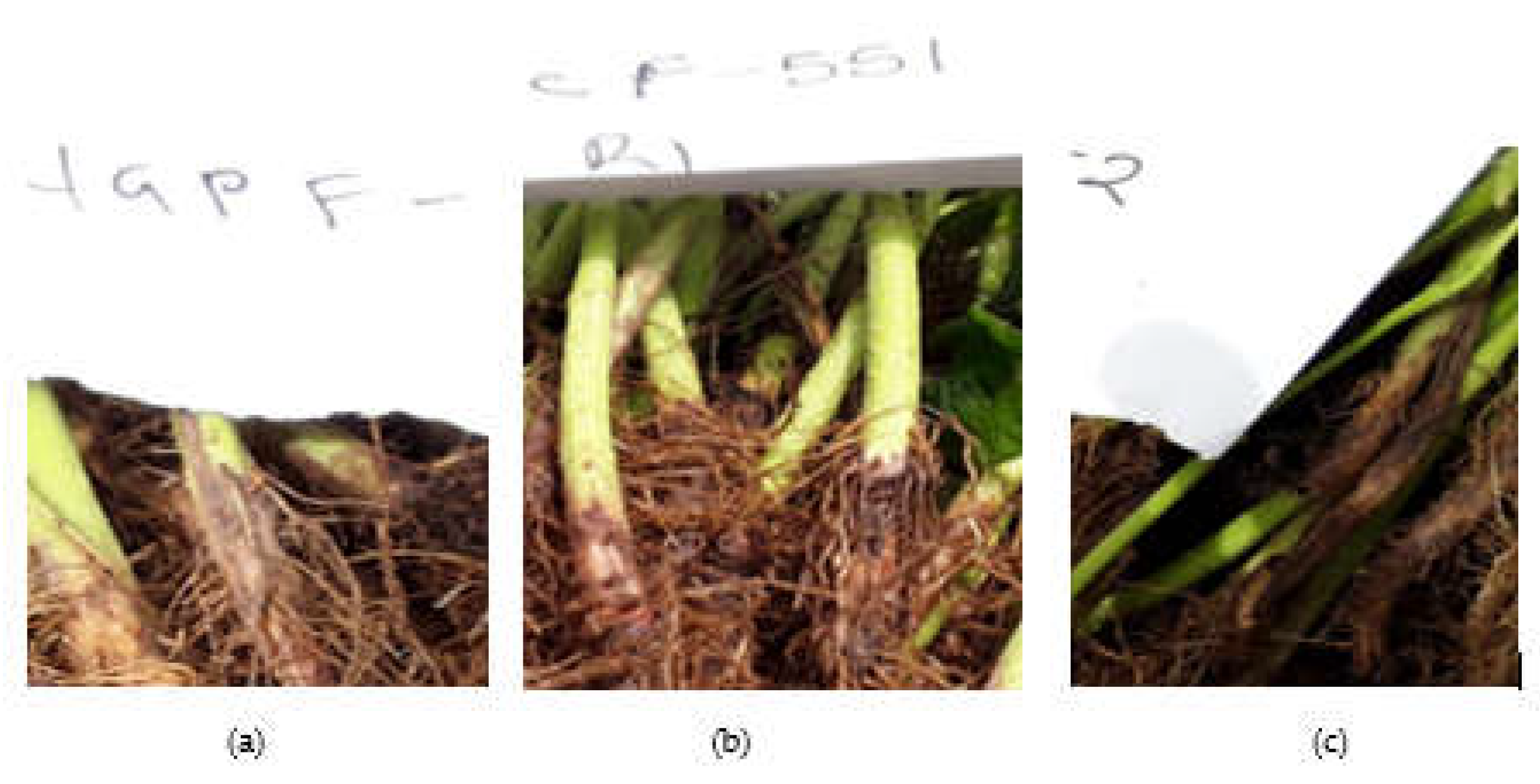

- Erima, S.; Nyine, M.; Edema, R.; Nkuboye, A.; Nakibuule, J.; Paparu, P. Morphological and pathogenic characterization of Fusarium species causing common bean root rot in Uganda. J. Sci. Agric. 2024, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietkiewicz, E.; Rafalski, A.; Labuda, D. Genome Fingerprinting by Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR)-Anchored Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification. Genomics 1994, 20, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, K.D.; Saucedo, E.S.; Zhong, S. Molecular Characterization of Fusarium Head Blight Pathogens Sampled from a Naturally Infected Disease Nursery Used for Wheat Breeding Programs in China. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, G.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Ploetz, R.C.; Gordon, T.R.; Viljoen, A. Current status of the taxonomic position of Fusarium oxysporum formae specialis cubense within the Fusarium oxysporum complex. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011, 11, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, B.; Abraham, D.; Graph, S.; Perl-Treves, R.; Harel, Y.M.; Degani, O. Isolation and Identification of Fusarium spp., the Causal Agents of Onion (Allium cepa) Basal Rot in Northeastern Israel. Biology 2020, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuangmek, W.; Kumla, J.; Khuna, S.; Lumyong, S.; Suwannarach, N. Identification and Characterization of Fusarium Species Causing Watermelon Fruit Rot in Northern Thailand. Plants 2023, 12, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, R.; Torp, M.; Kosiak, B.; Holst-Jensen, A. Phylogeny and toxigenic potential is correlated in Fusarium species as revealed by partial translation elongation factor 1 alpha gene sequences. Mycol. Res. 2005, 109, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirhendi, H.; Makimura, K.; de Hoog, G.S.; Rezaei-Matehkolaei, A.; Najafzadeh, M.J.; Umeda, Y.; Ahmadi, B. Translation elongation factor 1-α gene as a potential taxonomic and identification marker in dermatophytes. Med Mycol. 2014, 53, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olal, S.; Olango, N.; Kiggundu, A.; Ochwo, S.; Adriko, J.; Nanteza, A.; Matovu, E.; Lubega, G. W.; Kagezi, G.; Hakiza, G. J.; Wagoire, W. Using translation elongation factor gene to specifically detect and diagnose Fusarium xylaroides, a causative agent of coffee wilt disease in Ethiopia, East and Central Africa. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, E.; Nihlgard, M.; Varrelmann, M.; Hafez, M.; Abdelmagid, A.; Adam, L.R.; Daayf, F.; Covey, P.A.; Kuwitzky, B.; Hanson, M.; et al. Differentiation of Eleven Fusarium spp. Isolated from Sugar Beet, Using Restriction Fragment Analysis of a Polymerase Chain Reaction–Amplified Translation Elongation Factor 1α Gene Fragment. Phytopathology® 2009, 99, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheseli, O.P.; Susan, I.S.; Sheila, O.; Otipa, M.; Wafula, W.V. Prevalence and Phylogenetic Diversity of Pathogenic Fusarium Species in Genotypes of Wheat Seeds in Three Rift Valley Regions, Kenya. Adv. Agric. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wokorach, G.; Landschoot, S.; Audenaert, K.; Echodu, R.; Haesaert, G. Genetic Characterization of Fungal Biodiversity in Storage Grains: Towards Enhancing Food Safety in Northern Uganda. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajarningsih, N.D. Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) as Dna Barcoding to Identify Fungal Species: a Review. Squalen Bull. Mar. Fish. Postharvest Biotechnol. 2016, 11, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, I.M.; Kakoty, Y.; Unni, B.G.; Das, J.; Kalita, M.C. Identification and characterization of Fusarium sp. using ITS and RAPD causing fusarium wilt of tomato isolated from Assam, North East India. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2016, 14, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, S.R.; Gräfenhan, T.; Louis-Seize, G.; Seifert, K.A. Multiple copies of cytochrome oxidase 1 in species of the fungal genus Fusarium. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusiime, G. Variation and detection of Fusarium solani f. sp. phaseoli and quantification of soil inoculum in common bean fields. PhD Thesis, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. 2004.

- https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/tools-and-laboratories/standardisation_en.

- O'Donnell, K. Molecular Phylogeny of the Nectria haematococca-Fusarium solani Species Complex. Mycologia 2000, 92, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W.; et al.; Fungal Barcoding Consortium; Fungal Barcoding Consortium Author List; Bolchacova, E Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, H.A.; Miller, A.N.; Pearce, C.J.; Oberlies, N.H. Fungal Identification Using Molecular Tools: A Primer for the Natural Products Research Community. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.; Liu, Y.; Bhuiyan, M.Z.R.; Lakshman, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, S.; Bhuyian, Z.R.; Lashman, D. First Report of Fusarium equiseti Causing Seedling Death on Sugar Beet in Minnesota, U.S.A. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.-X.; Song, Z.-W.; Lu, Y.-M.; Fan, B. First Report of Fusarium falciforme (FSSC 3+4) Causing Root Rot in Weigela florida in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 981–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, R.; Sellami, H.; Gharbi, Y.; Krid, S.; Cheffi, M.; Kammoun, S.; Dammak, M.; Mseddi, A.; Gdoura, R.; Triki, M.A. Morphological and molecular characterization of Fusarium spp. associated with olive trees dieback in Tunisia. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasaka, R. W. 2017 Inheritence of resistance to Fusarium root rot (Fusarium Redolense) disease of cow peases in Uganda. MSc. Thesis, Makerere University, Kampala. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Denis, M.; Swart, W.J.; Crous, P.W. New Fusarium species from the Kruger National Park, South Africa. MycoKeys 2018, 34, 63–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, G.B.; Sajjan, S.S.; Karegoudar, T.B. Pathogenicity of indole-3-acetic acid producing fungus Fusarium delphinoides strain GPK towards chickpea and pigeon pea. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2011, 131, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehri, K.; Mohamed, N.; Salleh, B.; Latiffah, Z. Occurrence and pathogenicity of Fusarium spp. on potato tubers in Malaysia. African J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6(16), 3706–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.J. The Fusarium solani species complex: ubiquitous pathogens of agricultural importance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 17, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, H.; Jacobs, J.L.; Wang, J.; Mukankusi, C.M.; Chilvers, M.I. First Report of Fusarium cuneirostrum Causing Root Rot of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Uganda. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 2639–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukankusi, C. M. Improving resistance to Fusarium root rot [Fusarium solani (Mart.) Sacc. f. sp. phaseoli (Burkholder) W.C. Snyder & H.N. Hans.] in Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). PhD Thesis. University of KwaZulu- Natal, 2008 ,pp. 200.

- Xia, J.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Crous, P.; Zhang, X.; Lombard, L. Numbers to names - restyling the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex. Persoonia - Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2019, 43, 186–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugan, F.; Lupien, S.; Chen, W. Clonostachys rhizophaga and other fungi from chickpea debris in the Palouse region of the Pacific Northwest, USA. North Am. Fungi 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota-Barreras, C.I.; García-Estrada, R.S.; León-Félix, J.; Valenzuela-Herrera, V.; Mora-Romero, G.A.; Leyva-Madrigal, K.Y.; Tovar-Pedraza, J.M. First report of Clonostachys chloroleuca causing chickpea wilt in Mexico. New Dis. Rep. 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibert, S.; Edel-Hermann, V.; Gautheron, E.; Gautheron, N.; Bernaud, E.; Sol, J.; Capelle, G.; Galland, R.; Bardon-Debats, A.; Lambert, C.; et al. Identification, pathogenicity and community dynamics of fungi and oomycetes associated with pea root rot in northern France. Plant Pathol. 2022, 71, 1550–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, A.-F.; Gu, C.-Y.; Zang, H.-Y.; Chen, Y. First Report of Clonostachys rhizophaga as a Pathogen of Water Chestnut (Eleocharis dulcis) in Anhui Province of China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 151–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funck, J.D.; Dubey, M.; Jensen, B.; Karlsson, M. Clonostachys rosea to control plant diseases. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.; Bhuiyan, M.; Momotaz, R.; Bari, G.; Rahman, M. Cultural Characteristics, Virulence and In-vitro Chemical Control of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli of Bush bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Agric. 2014, 12, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlakoti, P.; Rivera, V.; Secor, G.A.; Qi, A.; Del Rio-Mendoza, L.E.; Khan, M.F.R. Comparative Pathogenicity and Virulence of Fusarium Species on Sugar Beet. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S/no | Strains | Agroecology | Species | Accession numbers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEF1-α | Β tubulin | ITS | ||||

| 1 | MbrF-119 | WMFS | F. fabacearum | PQ497180 | PQ497177 | PQ363745 |

| 2 | NakF-106-2 | NEDL | F. oxysporum | PQ497191 | PQ497142 | PQ363764 |

| 3 | KabF-103 | SWH | F. oxysporum | PQ497198 | PQ497143 | PQ363757 |

| 4 | SheF-250-1 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497207 | PQ497144 | PQ363766 |

| 5 | GomF-492 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497213 | PQ497145 | PQ363773 |

| 6 | KabF-108-1 | SWH | F. oxysporum | PQ497226 | PQ497146 | PQ363790 |

| 7 | KamF-290-2 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497234 | PQ497147 | PQ363797 |

| 8 | LweF-507 | LVC | F. oxysporum | - | PQ497148 | PQ363804 |

| 9 | MubF-442-2 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497182 | PQ497148 | - |

| 10 | MitF-489 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497181 | PQ497150 | PQ363746 |

| 11 | AmuF-513-3 | NEDL | F. falciforme | PQ497183 | PQ497151 | - |

| 12 | MubF-463 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497184 | PQ497152 | PQ363747 |

| 13 | KabF-114 | SWH | F. solani | PQ497185 | PQ497153 | - |

| 14 | GulF-451-1 | NMFS | F. solani | PQ497186 | PQ497154 | - |

| 15 | SheF-249 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497187 | PQ497155 | PQ363748 |

| 16 | KolF-563 | NMFS | F. brachygibbosum | PQ497188 | PQ497138 | PQ363749 |

| 17 | LweF-504 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497189 | PQ497176 | PQ363750 |

| 18 | MubF-463-1 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497190 | PQ497156 | PQ363751 |

| 19 | KabF-109-1 | SWH | F. delphinoides | PQ497192 | - | PQ363752 |

| 20 | OyaF-541-3 | NMFS | F. falciforme | PQ497193 | - | - |

| 21 | MubF-234 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497194 | PQ497175 | PQ363753 |

| 22 | KolF-557-4 | NMFS | F. equiseti | PQ497195 | PQ497174 | PQ363756 |

| 23 | LweF-497 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497196 | PQ497173 | - |

| 24 | ApaF-548 | NMFS | F. solani | - | PQ497172 | PQ363755 |

| 25 | MitF-491-1 | LVC | F. falciforme | PQ497197 | PQ497171 | PQ363791 |

| 26 | NakF-521 | NEDL | F. equiseti | PQ497205 | PQ497164 | PQ363765 |

| 27 | MubF-462-2 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497199 | PQ497170 | PQ363758 |

| 28 | ApaF-560 | NMFS | F. subflagellisporum | PQ497200 | PQ497169 | PQ363759 |

| 29 | NakF-520 | NEDL | F. equiseti | PQ497201 | PQ497168 | PQ363760 |

| 30 | MubF-465 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497202 | PQ497167 | PQ363761 |

| 31 | ApaF-551 | NEDL | F. equiseti | PQ497203 | PQ497166 | PQ363762 |

| 32 | LirF-602-2 | NEDL | F. equiseti | - | - | PQ363763 |

| 33 | NakF-106 | NEDL | F. solani | PQ497204 | PQ497165 | PQ363764 |

| 34 | KyeF-323 | WMFS | F. solani | PQ497206 | PQ497163 | - |

| 35 | LweF-223 | LVC | F. equiseti | PQ497208 | - | - |

| 36 | KapF-372 | EH | F. oxysporum | - | PQ497162 | PQ363767 |

| 37 | SirF-349-1 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497209 | PQ497161 | - |

| 38 | KamF-289 | WMFS | F. solani | - | - | PQ363768 |

| 39 | IbaF-270 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497210 | PQ497160 | PQ363769 |

| 40 | ApaF-546 | NMFS | F. equiseti | - | PQ497159 | PQ363770 |

| 41 | LweF-393 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497211 | PQ497158 | PQ363771 |

| 42 | SirF-358 | LVC | F. falciforme | PQ497212 | PQ497157 | PQ363772 |

| 43 | KabF-113-2 | SWH | F. fabacearum | PQ497214 | PQ497141 | PQ363774 |

| 44 | BusF-258 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | - | PQ497140 | PQ363775 |

| 45 | MitF-490 | LVC | F. commune | PQ497215 | PQ497139 | PQ363776 |

| 46 | AmuF-518-2 | NEDL | F. equiseti | PQ497216 | PQ497137 | PQ363777 |

| 47 | KamF-493-3 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497217 | PQ497136 | PQ363778 |

| 48 | KirF-416 | WMFS | F. solani | PQ497218 | PQ497135 | PQ363779 |

| 49 | SirF-358-1 | LVC | F. falciforme | PQ497219 | PQ497134 | PQ363780 |

| 50 | NakF-102-2 | NEDL | F. solani | - | - | PQ363781 |

| 51 | KabF-91-1 | SWH | F. oxysporum | - | - | PQ363782 |

| 52 | BusF-255-1 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497220 | PQ497120 | PQ363783 |

| 53 | MubF-464-2 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497221 | PQ497133 | PQ363784 |

| 54 | LweF-296 | LVC | F. commune | PQ497222 | PQ497119 | PQ363785 |

| 55 | NakF-520-1 | NEDL | F. serpentimum | PQ497223 | - | PQ363786 |

| 56 | MbarF-229 | WMFS | F. commune | PQ497224 | - | PQ363787 |

| 57 | ApaF-560-1 | NMFS | F. subflagellisporum | PQ497200 | PQ497121 | - |

| 58 | NakF-105-1 | NEDL | F. oxysporum | PQ497227 | - | - |

| 59 | MitF-487-2 | LVC | C. rhizophaga | PQ363792 | - | PQ363792 |

| 60 | MitF-481 | LVC | F. commune | PQ497225 | PQ497132 | PQ363789 |

| 61 | KyeF-320-2 | WMFS | F. solani | PQ497227 | PQ497131 | - |

| 62 | ApaF-548-2 | NMFS | F. solani | PQ497228 | - | - |

| 63 | SheF-250 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497207 | - | - |

| 64 | MasF-403 | WMFS | F. fredkrugeri | PQ497229 | - | - |

| 65 | MitF-491-2 | LVC | F. falciforme | PQ497230 | PQ497171 | PQ363788 |

| 66 | KirF-418 | WMFS | F. falciforme | PQ497231 | PQ497128 | PQ363793 |

| 67 | HoiF-385 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497232 | PQ497127 | PQ363794 |

| 68 | SirF-349-3 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497233 | PQ497126 | PQ363795 |

| 69 | MitF-487 | LVC | F. oxysporum | - | PQ497129 | PQ363788 |

| 70 | MubF-466 | LVC | F. oxysporum | - | - | PQ363798 |

| 71 | ApaF-546 | NMFS | F. equiseti | - | PQ497159 | - |

| 72 | KolF-562 | NMFS | F. solani | PQ497236 | PQ497124 | PQ363799 |

| 73 | KamF-290 | WMFS | F. oxysporum | - | - | PQ363800 |

| 74 | LweF-496 | LVC | F. oxysporum | - | - | PQ363801 |

| 75 | KolF-562-1 | NMFS | F. solani | - | PQ497125 | - |

| 76 | NakF-375 | NEDL | F. oxysporum | PQ497237 | PQ497123 | PQ363802 |

| 77 | Apaf-551-1 | NMFS | F. brevicaudatum | PQ497233 | - | - |

| 78 | LweF-215 | LVC | F. oxysporum | PQ497179 | PQ497122 | PQ363805 |

| 79 | ApaF-560 | NMFS | F. oxysporum | PQ497178 | PQ497121 | - |

| 80 | HoiF-385-1 | WMFS | F. solani | PQ497219 | - | PQ363803 |

| S/no | Organism Name |

No. of strains | DSI (%) | Growth rate (cm/day) | Microscopic structues at x40 magnification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

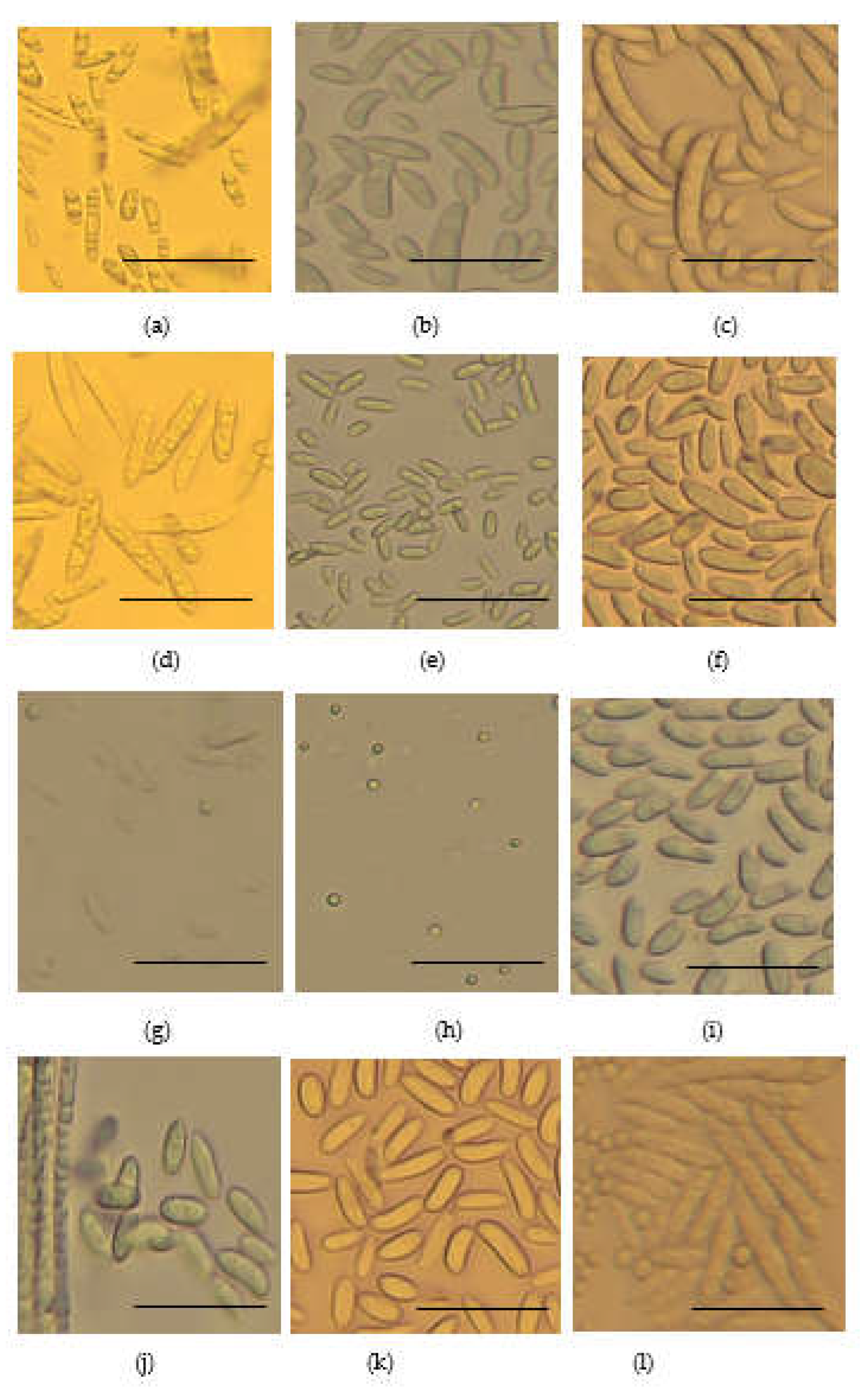

| 1 | F. delphinoides | 1 | 46.8 | 0.96 | Rod shaped non septate macro conidia about 5 to 50µm lond and spherical micro conidia |

| 2 | F. solani | 13 | 36.3 | 0.79 | Sickle shaped non septate macro conidia about 5 to 50 µm long. |

| 3 | F. oxysporum | 37 | 44.4 | 0.79 | Rod shaped sepate micro conidia about 20 to 50µm long |

| 4 | F. equiseti | 9 | 47.3 | 0.7 | Rod shaped non sepate macro conidia about 50 to 100µm long. Spherical micro conidia 2 to 10µm long |

| 5 | C. rhizophaga | 1 | 31.3 | 0.37 | Oval and rod shaped macro conidia about 10 to 50µm long |

| 6 | F. subflagellisporum | 2 | 66.6 | 1.2 | Sperical micro conidia about 2 to 5µm long. No macro conidia |

| 7 | F. fabacearum | 2 | 40.24 | 0.70 | Rod shaped non septate macro conidia about 5 to 50µm long. Spheical micro conidia |

| 8 | F. falciforme | 8 | 32.3 | 0.74 | Rod shaped macro conidia about 50 to 150µm long. Spherical micro conidia |

| 9 | F. brachygibbosum | 1 | 65.8 | 0.87 | Oval non sepate macro conidia about 10 to 30µm long |

| 10 | F. brevicaudatum | 1 | 59.3 | 0.6 | Isolates in storage failed to regenerate for microscopy |

| 11 | F. commune | 4 | 62.5 | 0.88 | Rod shaped nonsepate macro conidia about 5 to 50µm, |

| 12 | F. serpentimum | 1 | 45.1 | 0.17 | Isolates in storage failed to regenerate for microscopy |

| 13 | F. frekrugeri | 1 | 40.3 | 0.87 | Oval non septate macro conidia up to about 40µm long. Spherical micro conidia 5 to 10µm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).